Dynamic Protocol Parse Based on a General Protocol Description Language

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We have developed an automated parsing and dynamic expansion framework, accompanied by its corresponding implementation tools. This method advances the field of protocol parsing by enhancing its automation, enhances the convenience, dynamic extensibility, and accuracy of protocol parsing, and provides technical support for network traffic analysis.

- We abstract, categorize, and extract the categories of protocol information involved in each module of the protocol parsing process, which avoids the ambiguity of the protocol description language. Meanwhile, we defined a general Protocol Description Language, PMDL, and implemented the description of various protocol information based on the XML format.

- We generated the protocol template based on PMDL and designed and developed the protocol parsing engine, which ensured the accuracy of the protocol parsing results. In addition, we constructed a dynamically scalable and updatable protocol template in memory based on the description content of PMDL, and realized the parsing of various protocol data through the dynamic protocol parsing algorithm.

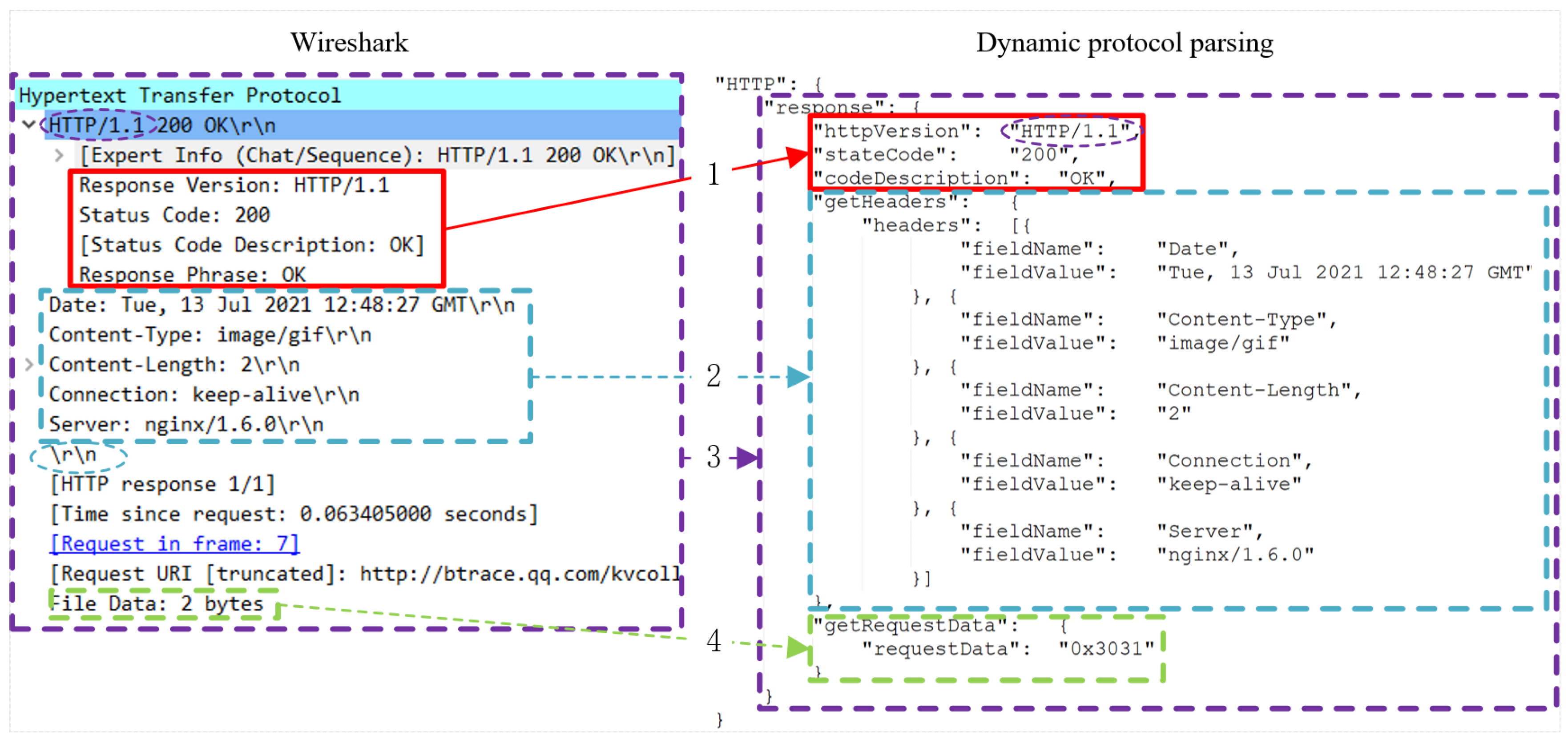

- The validity, simplicity, and correctness of PMDL are analyzed and verified in the experimental results. By benchmarking our PMDL against industry-standard tools, such as Wireshark [7] and Kelai [8], the experimental results demonstrate that PMDL can describe the protocol information succinctly and accurately, and the execution engine has better parsing performance, which meets the requirements of real-time security analysis.

2. Related Work

3. Protocol Data Model Definition

3.1. Protocol Information Extraction

- Field Extraction Module. It is responsible for separating and extracting fields one-by-one based on the field types, quantities, order, and data lengths defined in the protocol. Once extracted, the fields are sequentially dispatched to the Field Parsing Module for further processing.

- Field Parsing Module. It is responsible for obtaining information such as the data type, offset, and data length of the fields. It reads the specified length of the byte stream based on the offset, parses the fields according to their corresponding data types, and outputs them as readable or program-processable data.A concrete example of field extraction and parsing: Processing the IPv4 header. Consider an IPv4 header (first 20 bytes): 45 00 00 3c 1c 46 40 00 40 06 b1 e6 c0 a8 00 64 c0 a8 00 01. According to the IPv4 protocol, its field structure is as Table 1.Step 1: Field Extraction ModuleThis module separates the raw bytes of each field from the byte stream based on the offset and length defined in the PMDL template:

- (1)

- Version + IHL: extract 1 byte starting from offset 0 → 45

- (2)

- Total Length: extract 2 bytes starting from offset 2 → 00 3c

- (3)

- Source IP: extract 4 bytes starting from offset 12 → c0 a8 00 64

- (4)

- Destination IP: extract 4 bytes starting from offset 16 → c0 a8 00 01

At this stage, the fields are merely “sliced” out and remain in raw byte form.Step 2: Field Parsing ModuleThis module receives the extracted byte blocks and performs semantic conversion according to the field type:- (1)

- Version + IHL: 45 → parsed as integer 69, further decomposed into Version = 4, IHL = 5

- (2)

- Total Length: 00 3c → parsed in big-endian order as integer 60 (bytes)

- (3)

- Source IP: c0 a8 00 64 → parsed as IP address 192.168.0.100

- (4)

- Destination IP: c0 a8 00 01 → parsed as IP address 192.168.0.1

At this point, the fields have been converted into structured, human-readable, and machine-processable data.This modular division is highlighted as it embodies the separation of concerns principle:- (1)

- The extraction module focuses solely on structural positioning and is agnostic to field semantics;

- (2)

- The parsing module is dedicated to data transformation and operates independently of field positioning.

- Field Relationship Handling Module. It is responsible for executing the logic for handling relationships between fields and providing feedback to the Field Parsing Module and the Extraction Module, thereby altering the existence and attributes of the fields. For the Field Extraction Module, this is specifically reflected in the categories, quantities, and order of fields obtained during the extraction process. For the Field Parsing Module, this is specifically reflected in the data length attributes of the fields.

- Protocol Relationship Handling Module. It determines the next protocol type based on a specific identifier field in the protocol. In the current layered network model, non-application layer protocols generally define a field to identify the upper-layer protocol type and establish a mapping relationship between field values and upper-layer protocol categories. For example, when the port number of the TCP protocol is 53, it indicates that the application layer protocol is the DNS protocol.

3.2. Protocol Data Model and Element Abstract Representation

- Field (). It represents the fields defined in the protocol specification document that has actual significance. It is characterized by a set of constituent attributes and is formalized by the following expression:

- Field Relationship . It represents the field value association action information during the protocol parsing process, including existence relationships and attribute relationships. It consists of the indexed fields and the substituted processing flow, formalized by the following expression:

- Attribute . It is the most granular element in the model, described using a key–value pair representation to convey various information about basic fields, including field name, data type, data length, offset, and export type. The attribute value can represent field relationships, formalized by the following expression:

- Structured Field (). It represents the protocol flow control information, including branch selection control and loop control. It is composed of the fields involved in protocol flow control and the field relationships. To represent some complex protocol flow control, the fields involved in protocol flow control can also be structured fields, formalized by the following expression:

- Protocol Relationship (). It represents the association information between upper-layer and lower-layer protocols. It is composed of the protocol association field (Field) and the protocol mapping table (Value, Protocol), and its formula is as follows. The protocol association field (Field) and the protocol mapping table (Value, Protocol) compose the system, formalized by the following expression:

- Protocol (). It represents a specific network protocol and is used to characterize various types of protocol information, including fields, protocol structure, protocol relationships, and more. Its formal definition is expressed as follows:

4. Syntax Design of PMDL

4.1. Field Relationship Definition

- Boolean Relationship Expression. It represents the substitution of associated fields into Boolean operations to obtain true or false results, denoted by a pair of brackets “”. For complex Boolean expressions, the expression can also use the “&” and “|” symbols to perform logical AND and OR operations. For example, the relationship between the existence of the IPv4 Option field and the parsed value of the IHL field can be represented as follows:

- Numerical Relationship Expression. It represents the substitution of associated fields into mathematical operations to obtain numerical results, denoted by a pair of curly braces “{}”. For example, the relationship between the data length of the IPv4 Option field and the parsed value of the IHL field can be represented as follows:

4.2. Field and Attribute Definition

4.3. Structured Field Definition

- Branch Structured Field. Branch structures are used to describe scenarios in a protocol where the protocol structure changes due to different field values. They consist of branch decision conditions and a collection of branches. By evaluating the branch decision conditions, a specific array of fields within a branch can be selected for parsing. Based on the differences in the expression methods of the branch decision conditions, PMDL classifies branch structured fields into switch fields and if fields.

- (1)

- The switch field consists of associated branch fields and an array of case branches, as illustrated in (1) of Figure 2. It selects the corresponding case branch by matching the parsed value of the associated field. For example, in the HTTP protocol, if the parsed value of the first field is a request method, such as “Get” or “Post”, it indicates that the subsequent fields to be parsed are part of the request branch; if it is a protocol version, such as “HTTP/1.0” or “HTTP/1.1”, it indicates that the subsequent fields to be parsed are part of the response branch.

- (2)

- The if field consists of a Boolean expression and two branches: true and false, as illustrated in (2) of Figure 2. The branch selection is made by evaluating the truth value of the Boolean expression. For example, in the IPv4 protocol, the branch decision condition for the Option field is whether the value of the IHL field is greater than 5. If , the True branch is activated to parse the corresponding Option fields; conversely, if , the False branch is executed (typically resulting in no action), indicating the absence of options.

- Loop Structured Field. Loop structured fields are used to describe scenarios in a protocol where the number of other fields changes due to variations in field values. They consist of a loop decision condition and a collection of loop body fields. By evaluating the loop decision condition, the number of times the fields within the loop body are parsed can be determined. Based on the differences in the expression methods of the loop decision conditions, PMDL classifies loop structured fields into for fields and while fields. Since the design philosophy is based on RFC document standards, which provide detailed specifications and structures for the definition of network protocols, even complex issues, such as deeply nested fields, can be addressed using For and While loop structures.

- (1)

- The while field uses the loop decision expressions defined by the start and end attributes to determine whether to parse the loop body. For instance, in the HTTP protocol, header field–value pairs are parsed iteratively until the terminating delimiter—two consecutive Carriage Return and Line Feed (CRLF) characters—is encountered.

- (2)

- The for field describes the number of iterations using the times attribute, as illustrated in (2) of Figure 3. A typical example is found in the DNS protocol, where the fields in the Question section repeat in a loop; the exact number of iterations is dynamically determined by the value of the Question Count field.

4.4. Protocol Relationship Definition

4.5. Extensibility Support

- Custom Attributes. When the parsing process of a field still meets the basic processing logic of the protocol field parsing module, but requires additional specialized processing after extracting the byte stream, custom attributes can be used to introduce external program processing flows. For example, this can include endianness conversion, bitwise AND or OR operations, or combinations of multiple processing flows. PMDL defines the tag to describe custom attributes, including the attribute name, processing priority, and processing logic. Its syntax definition and usage are as follows:

- Custom Fields: When the parsing process of a field does not conform to the processing logic of the protocol field parsing module or the definitions of PMDL, custom fields can be used to introduce a field parsing program, thereby completing the description of the parsing process for that field. Its syntax definition and usage are as follows:

5. Design of PMDL Execution Engine

- Construction Module: Responsible for executing the protocol template construction and dynamic extension processes.It instantiates a protocol template from the PMDL description, which is then handed over to the Protocol Template Repository for centralized management.

- Parsing Module: Responsible for performing dynamic parsing based on protocol templates. It first fetches the target byte stream along with its associated protocol template from the repository. It then executes the dynamic protocol parsing algorithm according to the information in the protocol template and generates a temporary result chain.

- Export Module: Responsible for executing the formatted export procedure. First, it obtains the temporary result chain produced by the Parsing Module; then, it constructs a JSON-formatted object guided by the user-defined output configuration within the PMDL and serializes it for output.

5.1. Construction Module

- Read-Dominated Workload: As discussed in Section 5.1 of this paper, updates to protocol templates are typically triggered by RFC revisions and occur infrequently. In contrast, parsing threads frequently read templates to process incoming traffic, forming a classic “read-heavy, write-light” scenario. Read-write locks allow multiple reader threads to proceed concurrently, significantly improving parsing efficiency.

- Prevention of Update Conflicts: As stated in this paper, “by locking update and scanning operations on individual protocols within the protocol template library, we ensure that only one type of operation—either update or scan—can be performed on a protocol at any given time under concurrent access.” The read-write lock naturally supports this semantics: write operations are exclusive, while read operations are shared.

- Consistency Guarantee: The loading, validation, and replacement of a new template are performed under the protection of a write lock. This ensures that parsing threads never observe a partially updated or inconsistent template state.

- Low Overhead: Reader threads acquire the lock in shared mode, which is typically a lightweight atomic operation, imposing minimal performance overhead on the data processing path.

5.2. Parsing Module

- For branch fields, the execution engine evaluates the branch decision conditions to select a specific array of fields within a branch for parsing.

- For loop fields, the execution engine determines whether to parse the array of fields within the loop body based on the results of the loop decision conditions.

- For basic fields, the execution engine has constructed a unified processing logic for attributes, as shown in Figure 8. This includes three main branch routes: parsing of ordinary basic elements (red flow), parsing of basic elements with defined value attributes (purple flow), and parsing of custom fields (blue flow), while the green flow represents the common process.

5.3. Export Module

6. Experimental Analysis

6.1. Experimental Setup

6.2. Validity Verification

- Logical Decoupling: PMDL does not attempt to express recursive logic at the language level. Instead, it fully delegates the parsing task to an external C program via process="parseDomainName.c".

- External Implementation: The file parseDomainName.c implements the complete DNS name parsing logic, including:

- –

- Reading label length;

- –

- Detecting compression pointers (0xC0 marker);

- –

- Calculating jump offset;

- –

- Recursively or iteratively resolving pointer chains;

- –

- Concatenating the final domain name.

- Safety Control: The external C program can enforce a maximum recursion depth (e.g., 10 levels) to prevent stack overflow attacks.

- Reusability: The DomainName field can be reused across queries, responses, and resource records, improving template consistency.

- The parser encounters a <DomainName …> field;

- It looks up the <defField> definition and retrieves process="parseDomainName.c";

- It invokes the pre-loaded parseDomainName() function (compiled from parseDomainName.c);

- The external function returns the parsing result (e.g., the string "www.example.com");

- The parser resumes processing subsequent fields.

6.3. Simplicity Verification

6.4. Correctness Verification

6.5. Performance Analysis

- In this section, we conduct a comparative analysis using Nail and Bind, which possess representative advanced features, focusing on the complex DNS protocol. We calculate the parsing throughput by recording the number of packets processed each time and the time consumption, which is consistent with the PPS mentioned later. It can be seen from Figure 17 that the throughput of PMDL is lower than that of Nail. This is because while we are improving the dynamic scalability and semantic scalability of PMDL, we have caused certain losses in terms of throughput. As a certain degree of performance overhead is inevitable, the throughput of PMDL when parsing the DNS protocol is 23.08% lower than that of Wireshark (although PMDL’s throughput is lower than that of Nail, it is higher than that of Bind. Moreover, PMDL’s throughput also exceeds the average of Bind and Nail. Therefore, the resulting performance loss is acceptable in academic research.). One particularly prominent point is that PMDL still has significant advantages over Bind. The throughput of PMDL is nearly twice that of Bind. This indicates that the PMDL we proposed is somewhat advanced compared with other schemes. PMDL achieves an effective balance between performance and dynamic flexibility. However, in the context of single-protocol parsing where extreme speed is the primary objective, PMDL—as a dynamic interpretive engine—does not possess an absolute dominance over the pre-compiled Nail, primarily due to the intrinsic overhead of its interpretive layer. Nevertheless, this performance gap can be compensated for through multi-threaded parallelization, as illustrated in Figure 18.

- The execution engine, while implementing dynamic extension and parsing, should match the performance of traditional protocol analysis tools; otherwise, it will not meet the needs of practical application scenarios. This section selects two commonly used protocol analysis tools for comparison: Wireshark and Kelai. To assess efficiency across various layers, we selected a representative protocol stack—comprising Ethernet, IPv4, TCP, and application-layer protocols (HTTP, DNS, and MySQL)—each strictly adhering to their respective RFC specifications (e.g., RFC 791, RFC 7230). These protocols cover various structures such as fixed-length fields, variable-length fields, conditional branches, and string parsing. This chapter collects real campus network traffic for HTTP, MySQL, and DNS protocols on a mirrored traffic server and saves it as pcap files. Then, the data of different protocols within each pcap file are separated layer-by-layer and stored as corresponding pcap files. Finally, the PMDL execution engine, Wireshark, and Colasoft are used to parse each protocol’s pcap file, and the number of packets processed and the time taken for each processing are recorded to calculate the parsing throughput, i.e., packets per second (PPS), with the results shown in Figure 19.The experimental data in Figure 19 indicates that for the simple Ethernet II protocol parsing, the dynamic protocol parsing algorithm achieves higher throughput than Wireshark and Colasoft, as it does not need to handle inter-field relationships. The throughput of IPv4 shows a significant gap compared to Wireshark, while the throughput of TCP is roughly on a par with Wireshark. For application layer protocols, since the dynamic protocol resolution algorithm needs to frequently handle structural fields and relational expressions, its throughput is lower than that of Wireshark. Unlike Wireshark, which executes pre-compiled, static parsing logic via direct branch jumps, PMDL is designed as a declarative interpretive engine with the primary goal of providing dynamic extensibility. To maintain a deterministic guarantee without the need for recompilation, the engine must perform atomic-level attribute validation and runtime expression evaluation for every field defined in the PMDL template. Specifically, for each structured field, the engine triggers a high-density processing cycle: this involves retrieving variables from the parsed-field pool, calculating complex associative dependencies (e.g., length or existence logic), and updating the global parsing state in real-time. Although this mechanism introduces more frequent logical operations compared to Wireshark’s implicit execution paths, it represents a critical computational cost necessary to achieve unambiguous specification and on-the-fly protocol adaptation in complex network environments. (In practical applications, the advantages of PMDL in dynamic scalability and semantic scalability are beyond doubt; a certain degree of performance overhead is inevitable for PMDL. Compared to Wireshark, the throughput of PMDL is approximately 41.5% lower for HTTP, 37.9% lower for MySQL, and 29.16% lower for DNS.).To provide a deeper analysis of runtime performance, we conducted a systematic evaluation comparing PMDL with traditional parsers (Wireshark and Kelai). The resource consumption profile—specifically, CPU utilization and memory footprint—was comprehensively analyzed across a spectrum of representative protocols (Ethernet, IPv4, TCP, HTTP, and DNS), as illustrated in Figure 20 and Figure 21. In these figures, the horizontal axis lists the tested protocol types, while the vertical axis shows the CPU usage and memory footprint of each parser under identical test conditions.We analyzed the experimental results in terms of memory footprint and CPU usage. In terms of memory footprint, PMDL’s memory usage is slightly higher than that of Wireshark, primarily because PMDL needs to maintain metadata structures of protocol templates and dynamic parsing contexts at runtime to support flexible protocol extension. However, its memory overhead is comparable to that of Kelai, with no significant increase. Regarding CPU usage, PMDL’s utilization is notably lower than that of Kelai and close to that of Wireshark. This is attributed to PMDL’s efficient template-driven parsing mechanism and lightweight runtime scheduling, indicating high computational efficiency when processing packets.To further analyze the performance differences between the dynamic protocol parsing algorithm and Wireshark, this chapter implemented a use case program for parallel execution of dynamic protocol parsing based on the multithreading library in a Windows environment. The parallelism was then adjusted to parse the pcap files collected in the previous experiment and calculate the throughput. Figure 18 shows the throughput of the execution engine processing offline pcap files for the five protocols, IPv4, TCP, HTTP, MySQL, and DNS, using 1, 2, 4, and 8 threads on the host.The results in Figure 18 indicate that the performance of the dynamic protocol parsing algorithm scales linearly at parallelism levels of 2 and 4. With two threads, the dynamic protocol parsing throughput reaches or exceeds that of Wireshark. This suggests that the performance gap between the dynamic protocol parsing algorithm and the Wireshark tool can be mitigated by adding a small number of threads, and the performance loss incurred by the execution engine in implementing dynamic extension and parsing is within an acceptable range.

- Comparison of template update latency with recompilation in traditional parsers.In traditional parsers, protocol logic is statically embedded within the parser’s core. This implementation (typically in C/C++) is compiled into machine instructions at build time, becoming tightly coupled with the executable binary. Consequently, supporting a new protocol or updating an existing one requires manual source code modification followed by a full project recompilation. This “compilation” process is complex and resource-intensive, involving multiple stages such as syntax tree construction, optimization, and target code generation. More importantly, for the newly generated binary to take effect, the entire parsing service usually must be restarted. This means that during the update, the service is interrupted, and data streams being processed may be lost.Theoretical Latency: Therefore, the update latency in traditional approaches is fundamentally composed of “compilation time + deployment time + restart time”. This is an offline, disruptive process with latency on the order of minutes or even longer, making it unsuitable for real-time security analysis.The core innovation of PMDL lies in the decoupling of protocol description from execution logic. The definition of a protocol (i.e., “what the protocol is”) is abstracted into a standalone PMDL description file (template) independent of the engine, while the parsing engine itself is a general-purpose, unchanging runtime environment. When a protocol requires an update, users merely provide a revised PMDL file. The engine’s built-in monitor periodically scans the configuration directory; upon detecting changes, it ingests the XML-based PMDL and converts it into an internal in-memory data structure. This process is essentially a lightweight configuration load, involving significantly lower computational overhead than full-scale recompilation. Crucially, by employing concurrency control mechanisms such as read-write locks, the engine achieves hot-swapping—injecting new templates into the runtime library without interrupting active parsing tasks or degrading service continuity.Theoretical Latency: Thus, PMDL’s update latency primarily depends on the filesystem scan interval and the speed of XML parsing. This is an online, non-disruptive process, theoretically capable of second-level latency and zero downtime.Therefore, through its unique architectural design, PMDL transforms protocol updates from the traditional parser’s “code-compile-restart” paradigm into a “configuration-load-hot-update” paradigm. This fundamental shift enables PMDL to achieve a qualitative leap in template update latency compared to the “recompilation” approach of traditional parsers, effectively addressing the inherent scalability bottleneck of conventional methods.

6.6. Threat Model

- Strict Boundary Enforcement: By utilizing explicit length descriptors (bit, byte, endstr), the engine performs mandatory pre-checks on the remaining payload length. Any discrepancy between the declared length and the actual length triggers an immediate deterministic drop, effectively preventing buffer overflows and out-of-bounds read attempts.

- Semantic-Level Filtering: The use of strong-typed attributes (type) and specific formats (export) constitutes a defensive layer. The engine validates data compliance during the transformation phase, ensuring that malformed traffic is intercepted before it can affect higher-level semantic analysis.

- Execution Safeguards: To prevent resource exhaustion caused by malicious loops (e.g., nested while loops), PMDL implements bounded jumps and iteration threshold mechanisms. By restricting loop counts to the range of previously parsed field values and enforcing a maximum iteration cap, the engine can effectively resist Parsing DoS attacks.

- Formal Verification of Templates: To mathematically prove the absence of logical loopholes or ambiguous paths.

- Dynamic Resource Quota Management: To allocate CPU and memory resources more granularly across concurrent parsing tasks.

- Heuristic Detection of Complex Semantic Attacks: To identify sophisticated threats that comply with syntax but violate business logic.

- Hardware-Accelerated Parallel Defense: To maintain rigorous atomic-level validation under ultra-high throughput environments using FPGA or GPU architectures.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhong, Y.; Wang, Z.; Shi, X.; Yang, J.; Li, K. Rfg-helad: A robust fine-grained network traffic anomaly detection model based on heterogeneous ensemble learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 5895–5910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Lan, X.; Tang, R.; Jiang, S.; Shen, C. Empowering Data Owners: An Efficient and Verifiable Scheme for Secure Data Deletion. Comput. Secur. 2024, 144, 103978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Chen, X.; Chen, L.; Lan, X.; Ren, H.; Shen, C. An efficient and commercial proof of storage scheme supporting dynamic data updates. Comput. Secur. 2025, 157, 104609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Zhan, W.; Min, G.; Duan, Z.; Peng, K. Mobility-aware computation offloading with load balancing in smart city networks using MEC federation. IEEE Trans. Mobile Comput. 2024, 23, 10411–10428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, A. Web Application Security, 1st ed.; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2024; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Q.; Sun, C.; Cui, B.; Jin, X. A novel model for anomaly detection in network traffic based on kernel support vector machine. Comput. Secur. 2021, 104, 102215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bock, L. Learn Wireshark: A Definitive Guide to Expertly Analyzing Protocols and Troubleshooting Networks Using Wireshark, 1st ed.; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2022; pp. 154–196. [Google Scholar]

- About Kelai. Available online: https://flbook.com.cn/c/NoZPxcfuA3#page/8 (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Yen, J.; Lévai, T.; Ye, Q.; Ren, X.; Govindan, R.; Raghavan, B. Semi-automated protocol disambiguation and code generation. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM SIGCOMM 2021 Conference, Virtual Event, 23–27 August 2021; pp. 272–286. [Google Scholar]

- Risso, F.; Baldi, M. NetPDL: An extensible XML-based language for packet header description. Comput. Netw. 2006, 50, 688–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bangert, J.; Zeldovich, N. Nail: A practical tool for parsing and generating data formats. In Proceedings of the 11th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 14), Broomfield, CO, USA, 6–8 October 2014; pp. 615–628. [Google Scholar]

- Hammer Parser Generator. Available online: https://github.com/UpstandingHackers/hammer (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- BIND 9 DNS Server. Available online: http://www.isc.org/downloads/bind/ (accessed on 4 November 2025).

- Delaware, B.; Suriyakarn, S.; Pit-Claudel, C.; Ye, Q.; Chlipala, A. Narcissus: Correct-by-construction derivation of decoders and encoders from binary formats. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2019, 3, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McQuistin, S.; Band, V.; Jacob, D.; Perkins, C. Parsing protocol standards to parse standard protocols. In Proceedings of the 2020 Applied Networking Research Workshop, Kauai, HI, USA, 30–31 July 2020; pp. 25–31. [Google Scholar]

- McQuistin, S.; Band, V.; Jacob, D.; Perkins, C. Investigating Automatic Code Generation for Network Packet Parsing. In Proceedings of the 2021 IFIP Networking Conference (IFIP Networking), Warsaw, Poland, 21–24 June 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Mundkur, P.; Briesemeister, L.; Shankar, N.; Anantharaman, P.; Ali, S.; Lucas, Z.; Smith, S. The Parsley data format definition language. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), San Francisco, CA, USA, 18–21 May 2020; pp. 300–307. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L.W.; Eakman, G.; Garcia, E.J.; Atman, S. Accessible Formal Methods for Verified Parser Development. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), San Francisco, CA, USA, 24–26 May 2021; pp. 142–151. [Google Scholar]

- Swamy, N.; Ramananandro, T.; Rastogi, A.; Spiridonova, I.; Ni, H.; Malloy, D.; Vazquez, J.; Tang, M.; Cardona, O.; Gupta, A. Hardening attack surfaces with formally proven binary format parsers. In Proceedings of the 43rd ACM SIGPLAN International Conference on Programming Language Design and Implementation, San Diego, CA, USA, 13–17 June 2022; pp. 31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; Morrisett, G.; Tan, G. Interval parsing grammars for file format parsing. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2023, 7, 1073–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diatchki, I.S.; Dodds, M.; Goldstein, H.; Harris, B.; Holland, D.A.; Razet, B.; Schlesinger, C.; Winwood, S. Daedalus: Safer Document Parsing. Proc. ACM Program. Lang. 2024, 8, 816–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Guo, Z.; Song, M.; Sha, M. 100 Gbps Dynamic Extensible Protocol Parser Based on an FPGA. Electronics 2022, 11, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Luo, W.; Zhou, Q.; Tang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Shi, Y.; Jia, Y. Gradient Inversion of Text-Modal Data in Distributed Learning. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 928–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, F.; Zhang, X.; Xu, D. NetPlier: Probabilistic Network Protocol Reverse Engineering from Message Traces. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS 2021), Virtual Event, 21–25 February 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler, J.; Wick, A.; Fisher, K. BinaryInferno: A Semantic-Driven Approach to Field Inference for Binary Message Formats. In Proceedings of the Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS 2023), San Diego, CA, USA, 26 February–3 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, P.; Yegneswaran, V. Prosper: Extracting protocol specifications using large language models. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Workshop on Hot Topics in Networks, Boston, MA, USA, 8–9 November 2023; pp. 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.; Xu, H.; Ba, Z.; Wang, Z.; Hong, Y.; Liu, J.; Qin, Z.; Ren, K. Privacyasst: Safeguarding user privacy in tool-using large language model agents. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2024, 21, 5242–5258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.I.; Su, Y.; Li, G. Zero-shot construction of Chinese medical knowledge graph with GPT-3.5-turbo and GPT-4. ACM Trans. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2025, 16, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, M.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, C.; Wang, W. Toward automated field semantics inference for binary protocol reverse engineering. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 19, 764–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Ishtiaq, A.; Das, S.S.S.; Rashid, S.M.M.; Ranjbar, A.; Tu, K.; Wu, T.; Song, Z.; Wang, W.; Akon, M.; Zhang, R.; et al. Hermes: Unlocking security analysis of cellular network protocols by synthesizing finite state machines from natural language specifications. In Proceedings of the 33rd USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 24), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 14–16 August 2024; pp. 4445–4462. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, R.; Mirchev, M.; Böhme, M.; Roychoudhury, A. Large language model guided protocol fuzzing. In Proceedings of the 31st Annual Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS 2024), San Diego, CA, USA, 27 February–1 March 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Gibb, G.; Varghese, G.; Horowitz, M.; McKeown, N. Design principles for packet parsers. In Proceedings of the Architectures for Networking and Communications Systems, Santa Monica, CA, USA, 9–10 October 2013; pp. 13–24. [Google Scholar]

| Field | Offset (Bytes) | Length | Type |

|---|---|---|---|

| Version + IHL | 0 | 1-byte | uint8 |

| Total Length | 2 | 2-bytes | uint16 |

| Source IP | 12 | 4-bytes | ipv4 |

| Destination IP | 16 | 4-bytes | ipv4 |

| Protocol Parsing Module | Protocol Information Categories | Specific Protocol Information Content |

|---|---|---|

| Field Parsing Module | Field Attribute Information | Field Name, Data Type, Data Length, Offset |

| Field Relationship Handling Module | Field Relationship Information | Existence Relationship, Attribute Relationship |

| Field Extraction Module | Protocol Structure Information | Field Type, Field Quantity, Field Order |

| Field Extraction Module | Flow Control Information | Branch Selection Control, Loop Control |

| Protocol Relationship Handling Module | Protocol Relationship Information | Protocol Identifier Field, Upper Layer Protocol Mapping Table |

| Attribute Name | Description | Attribute Values and Their Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| bit | Define the data length of non-byte-aligned fields, measured in bits. | The attribute value for fixed-length fields is a non-negative integer. For example: bit = “4” indicates that the field length is 4 bits. The attribute value for variable-length fields is a numerical relationship expression. For example: bit = “$field * 4 ” indicates that the bit length of the field is determined by the calculated value of the formula. |

| byte | Define the data length of byte-aligned fields, measured in bytes. | The attribute value for fixed-length fields is a non-negative integer, while the attribute value for variable-length fields is a numerical relationship expression (similar to the example for bits). |

| endstr | Define the field data length by matching the defined terminating string. | The attribute value can be a matching string or a field reference value, for example, endstr = “∖ r ” or endstr = $StrField. |

| remain | Define the field data length by obtaining the remaining bit count. | True or false. Here, true indicates that the remaining bit count is used to define the data length of the variable-length field. |

| value | Define field variables to cache intermediate parsing results or for output. | The attribute value can be any number, string, byte stream, or Boolean. |

| name | Define field name. | The attribute value is a combination of 26 uppercase and lowercase letters and numbers. |

| type | Define the data type of the field. | int, uint, float, bool, bytes or string. |

| trans | Define whether the field parsing involves endianness conversion. | True or false, where true indicates that endianness conversion is performed during parsing. |

| jump | Define whether to skip parsing the field. | True or false, where true indicates that parsing is to be skipped. |

| offset | Define whether to offset the data stream pointer and parse the next field. | True or false, where true indicates that the pointer is offset and the next field is parsed. |

| export | Define the formatted output type of the field parsing results. | number, bool, bytes, string, mac, ipv4, ipv6 or null, where null indicates no output. |

| Mechanism | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages | Evaluation Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coarse-grained Mutex (Mutex) | Use a single mutex to protect the entire protocol template library. | Simple implementation, ensures consistency. | All read operations are serialized, poor performance under high concurrency. | Rejected: Cannot meet concurrent parsing requirements in multi-threaded scenarios. |

| Fine-grained Locking | Use independent locks for each protocol or template. | Reduces contention, supports partial concurrency. | Complex lock management, potential deadlock risk. | Considered but rejected: High complexity with limited benefit. |

| Read-Write Lock (rwlock) | Allow multiple reader threads to access concurrently, while write operations are exclusive. | Suitable for read-intensive workloads, low read overhead. | Write operations may starve if readers are frequent. | Adopted: Achieves optimal balance between performance and safety. |

| File Name | Packet Count | Size (KB) | Size (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ethernet.pcap | 720,000 | 21,094 | 20.60 |

| ipv4.pcap | 468,000 | 22,852 | 22.32 |

| tcp.pcap | 295,200 | 20,180 | 19.71 |

| http.pcap | 189,699 | 102,492 | 100.09 |

| mysql.pcap | 640,000 | 116,075 | 113.35 |

| dns.pcap | 672,000 | 101,822 | 99.44 |

| Related Technologies | Based on the Protocol Description Language | Based on FPGA | Based on Artificial Intelligence | Our | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Related Research | Nail [11] | NetPDL [10] | Narcissus [14] | Reference [16] | Reference [22] | Reference [29] | Reference [26] | Reference [24] | PMDL |

| The completeness of data types | √ | √ | √ | ◯ | ◯ | √ | √ | √ | √ |

| The diversity of protocol types | √ | √ | √ | ◯ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Variable protocol structure | ◯ | ◯ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||

| Protocol relationship definition | √ | √ | √ | ◯ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |

| Syntax extensibility | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Output format definition | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | ||||

| Non-ambiguity | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Deterministic accuracy | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | √ | |||

| Dataset dependency | √ | √ | √ | ||||||

| Comparison Items | Position of Comparison Items (Protocol-Mapping Number) | Comparison Results |

|---|---|---|

| Fixed-length basic field | IPv4-1, IPv4-2, IPv4-3 | Same |

| Variable-length basic field | HTTP-1, Mysql-2 | Same |

| Switch structure field | HTTP-3, Mysql-3 | Same |

| If structure field | HTTP-4 | Same |

| While structure field | HTTP-2 | Same |

| For structure field | Mysql-1 | Same |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Lin, D.; Gong, X.; Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Xu, Z.; Dong, P. Dynamic Protocol Parse Based on a General Protocol Description Language. Electronics 2026, 15, 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020270

Lin D, Gong X, Liu X, Chen L, Xu Z, Dong P. Dynamic Protocol Parse Based on a General Protocol Description Language. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):270. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020270

Chicago/Turabian StyleLin, Dong, Xun Gong, Xiaobo Liu, Liangguo Chen, Zhenwu Xu, and Ping Dong. 2026. "Dynamic Protocol Parse Based on a General Protocol Description Language" Electronics 15, no. 2: 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020270

APA StyleLin, D., Gong, X., Liu, X., Chen, L., Xu, Z., & Dong, P. (2026). Dynamic Protocol Parse Based on a General Protocol Description Language. Electronics, 15(2), 270. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020270