Performance Analysis and Comparison of Two Deep Learning Methods for Direction-of-Arrival Estimation with Observed Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- Systematic investigation of distinct feature extraction paradigms. Comparative analyses are conducted to elucidate how CNN’s local spatial pattern extraction and LSTM’s sequential memory integration yield quantifiably divergent performance characteristics across varying regimes of the SNR, array element count, element spacing, and snapshot number.

- (2)

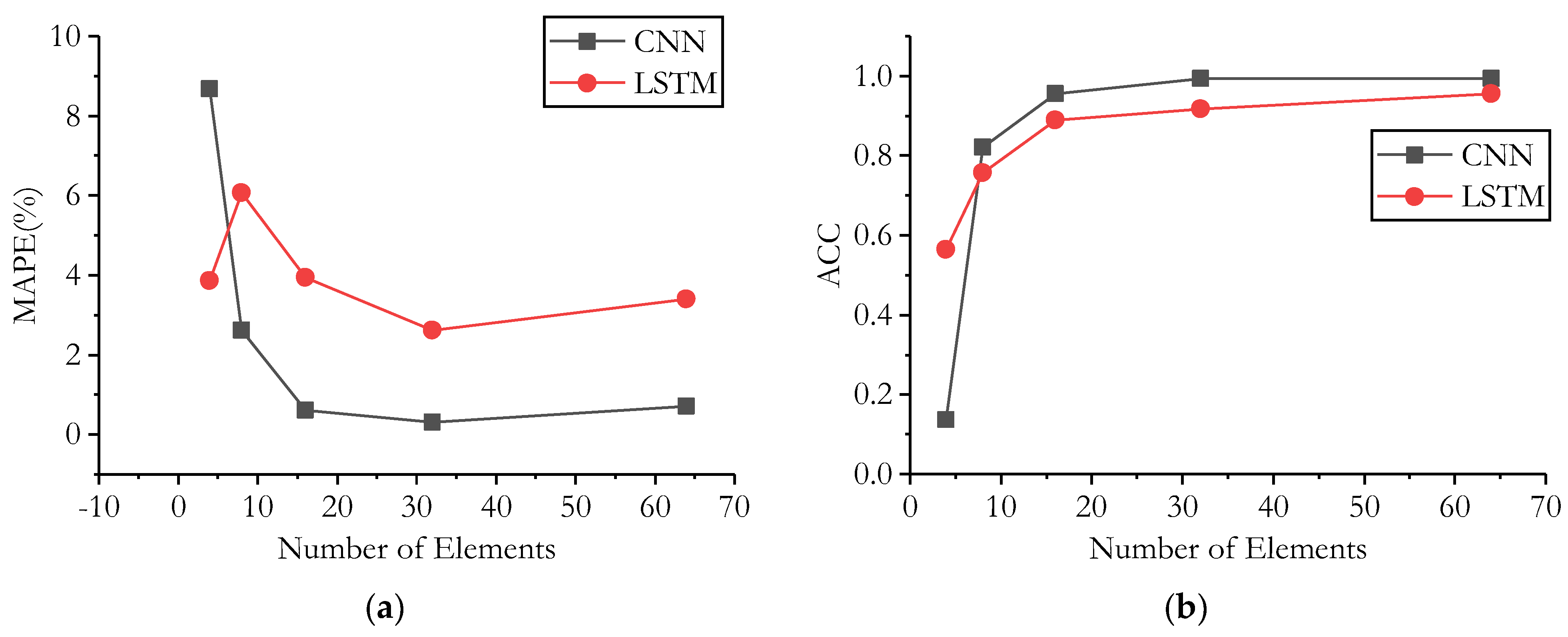

- Four performance boundaries are identified. Optimal performance is achieved at half-wavelength element spacing; SNR crossover occurs at −20 dB, below which accuracy drops sharply; the snapshot threshold of 32 marks the transition from snapshot-deficient to snapshot-sufficient conditions; the array size of 8 is a turning point for the performance variation rate. Based on a multidimensional analysis encompassing the SNR, array configuration, computational efficiency, and measured data performance, specific recommendations for engineering applications are provided, thereby bridging the gap between algorithmic research and practical deployment.

- (3)

- Validation of sim-to-real generalization capability. On the SWAP experimental dataset, it is demonstrated that models trained exclusively on single-target simulated signals can generalize to multi-target real underwater environments without domain adaptation, thus providing empirical evidence for the cross-domain applicability of CSDM-based deep learning approaches.

2. Model, Data, and Methods

2.1. Signal Model

2.2. Data Information

2.2.1. The Simulation Data

2.2.2. The Experimental Data

2.3. Neural Network Architecture

2.3.1. CNN-Based DOA Model

- Model Formulation:

- 2.

- Network Configuration

2.3.2. LSTM-Based DOA Model

- 1.

- Model Formulation

- 2.

- Network Configuration

2.3.3. Performance Metrics

2.3.4. Hyperparameter Selection

3. Results

3.1. The Results of Simulation Data

3.1.1. The Results of the CNN Method

- 1.

- SNR

- 2.

- Spacing of elements

- 3.

- Number of elements

3.1.2. The Results of the LSTM Method

- 1.

- SNR

- 2.

- Spacing of elements

- 3.

- Number of elements

3.2. The Results of Experimental Data

3.2.1. The Results of the CNN Method

3.2.2. The Results of the LSTM Method

3.3. Compare and Contrast

3.3.1. Performance Comparison of CNN and LSTM

3.3.2. Performance Comparison of Other Algorithms

- 1.

- Comparison of Algorithm Resolution

- 2.

- Comparison of ACC and RMSE under different SNRs

- 3.

- Comparison of ACC and RMSE under different snapshots

- 4.

- Comparison of Computational Complexity and Real-Time Performance

- 5.

- Performance Comparison in Actual Underwater Acoustic Data

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Schmidt, R.O. Multiple Emitter Location and Signal Parameter Estimation. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1986, 34, 276–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Paulraj, A.; Kailath, T. ESPRIT—A Subspace Rotation Approach to Estimation of Parameters of Cisoids in Noise. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1986, 34, 1340–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capon, J. High-Resolution Frequency-Wavenumber Spectrum Analysis. Proc. IEEE 1969, 57, 1408–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoica, P.; Nehorai, A. MUSIC, Maximum Likelihood, and Cramér-Rao Bound. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1989, 37, 720–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Trees, H.L. Optimum Array Processing: Part IV of Detection, Estimation, and Modulation Theory; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Krim, H.; Viberg, M. Two Decades of Array Signal Processing Research: The Parametric Approach. IEEE Signal Process. Mag. 1996, 13, 67–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlander, B.; Weiss, A.J. Direction Finding in the Presence of Mutual Coupling. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 1991, 39, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wax, M.; Kailath, T. Detection of Signals by Information Theoretic Criteria. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1985, 33, 387–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, T.J.; Wax, M.; Kailath, T. On Spatial Smoothing for Direction-of-Arrival Estimation of Coherent Signals. IEEE Trans. Acoust. Speech Signal Process. 1985, 33, 806–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialer, O.; Garnett, N.; Tirer, T. Performance Advantages of Deep Neural Networks for Angle of Arrival Estimation. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2019–2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Brighton, UK, 12–17 May 2019; pp. 3907–3911. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.M.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. Direction-of-Arrival Estimation Based on Deep Neural Networks with Robustness to Array Imperfections. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2018, 66, 7315–7327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Zhao, S.; Zhong, X.; Jones, D.L.; Chng, E.S.; Li, H. A Learning-Based Approach to Direction of Arrival Estimation in Noisy and Reverberant Environments. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), South Brisbane, Australia, 19–24 April 2015; pp. 2814–2818. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, R.; Komatani, K. Sound Source Localization Based on Deep Neural Networks with Directional Activate Function Exploiting Phase Information. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Shanghai, China, 20–25 March 2016; pp. 405–409. [Google Scholar]

- Ozanich, E.; Gerstoft, P.; Niu, H. A Feedforward Neural Network for Direction-of-Arrival Estimation. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 147, 2035–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Chen, H.; Wang, B. DOA Estimation Based on CNN for Underwater Acoustic Array. Appl. Acoust. 2021, 172, 107594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chen, J.; Bai, J.; Ayub, M.S.; Zhang, D.; Wang, M.; Yan, Q. Deep Learning-Based DOA Estimation Using CRNN for Underwater Acoustic Arrays. Front. Mar. Sci. 2022, 9, 1027830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, D. Robust Speaker Localization Guided by Deep Learning-Based Time-Frequency Masking. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2019, 27, 178–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, H.; Chen, B.; Yang, M.; Xu, S.; Li, Z. Improved Direction-of-Arrival Estimation Method Based on LSTM Neural Networks with Robustness to Array Imperfections. Appl. Intell. 2021, 51, 4420–4433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, B. Data-Driven DOA Estimation Methods Based on Deep Learning for Underwater Acoustic Vector Sensor Array. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 2023, 57, 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, R.; Varshney, A.; Dahiya, S. DoA Estimation of GNSS Jamming Signal Using Tripole Vector Antenna and Random Forest Regression. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Conference on Advanced Networks and Telecommunications Systems (ANTS), Guwahati, India, 15–18 December 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Florio, A.; Avitabile, G.; Talarico, C.; Coviello, G. A Reconfigurable Full-Digital Architecture for Angle of Arrival Estimation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 71, 1443–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florio, A.; Coviello, G.; Talarico, C.; Avitabile, G. Adaptive DDS-PLL Beamsteering Architecture Based on Real-Time Angle-of-Arrival Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 67th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Springfield, MA, USA, 11–14 August 2024; pp. 628–631. [Google Scholar]

- Ozanich, E.; Gerstoft, P.; Niu, H. A Deep Network for Single-Snapshot Direction of Arrival Estimation. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 29th International Workshop on Machine Learning for Signal Processing (MLSP), Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 13–16 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, B.; Cui, X.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, Y. Multi-Source Underwater DOA Estimation Using PSO-BP Neural Network Based on High-Order Cumulant Optimization. China Commun. 2023, 20, 212–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khurjekar, I.D.; Gerstoft, P. Uncertainty Quantification for Direction-of-Arrival Estimation with Conformal Prediction. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2023, 154, 979–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep Learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chollet, F. Deep Learning with Python; Manning Publications: Shelter Island, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kingma, D.P.; Ba, J. Adam: A Method for Stochastic Optimization. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Learning Representations, ICLR 2015, San Diego, CA, USA, 7–9 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Nie, W.; Ye, L.; Cheng, G.; Yan, Y. Reliable Underwater Multi-Target Direction of Arrival Estimation with Optimal Transport Using Deep Models. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2024, 156, 2119–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Target | Method | Track Recovery Rate (%) | Detection Rate (%) | Mean Bearing Error (°) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | CNN | 40.83 | 45.41 | 1.64 |

| LSTM | 52.75 | 55.96 | 1.5 | |

| T2 | CNN | 4.20 | 26.05 | 6.84 |

| LSTM | 18.49 | 42.86 | 5.00 | |

| T3 | CNN | 13.71 | 21.14 | 6.46 |

| LSTM | 1.71 | 2.86 | 4.20 | |

| T4 | CNN | 8.54 | 12.80 | 4.05 |

| LSTM | 4.27 | 6.71 | 4.64 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, S.; Zhang, W.; Song, J.; Shi, J.; Leng, H.; Yu, Q. Performance Analysis and Comparison of Two Deep Learning Methods for Direction-of-Arrival Estimation with Observed Data. Electronics 2026, 15, 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020261

Liu S, Zhang W, Song J, Shi J, Leng H, Yu Q. Performance Analysis and Comparison of Two Deep Learning Methods for Direction-of-Arrival Estimation with Observed Data. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):261. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020261

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Shuo, Wen Zhang, Junqiang Song, Jian Shi, Hongze Leng, and Qiankun Yu. 2026. "Performance Analysis and Comparison of Two Deep Learning Methods for Direction-of-Arrival Estimation with Observed Data" Electronics 15, no. 2: 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020261

APA StyleLiu, S., Zhang, W., Song, J., Shi, J., Leng, H., & Yu, Q. (2026). Performance Analysis and Comparison of Two Deep Learning Methods for Direction-of-Arrival Estimation with Observed Data. Electronics, 15(2), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020261