MSTFT: Mamba-Based Spatio-Temporal Fusion for Small Object Tracking in UAV Videos

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

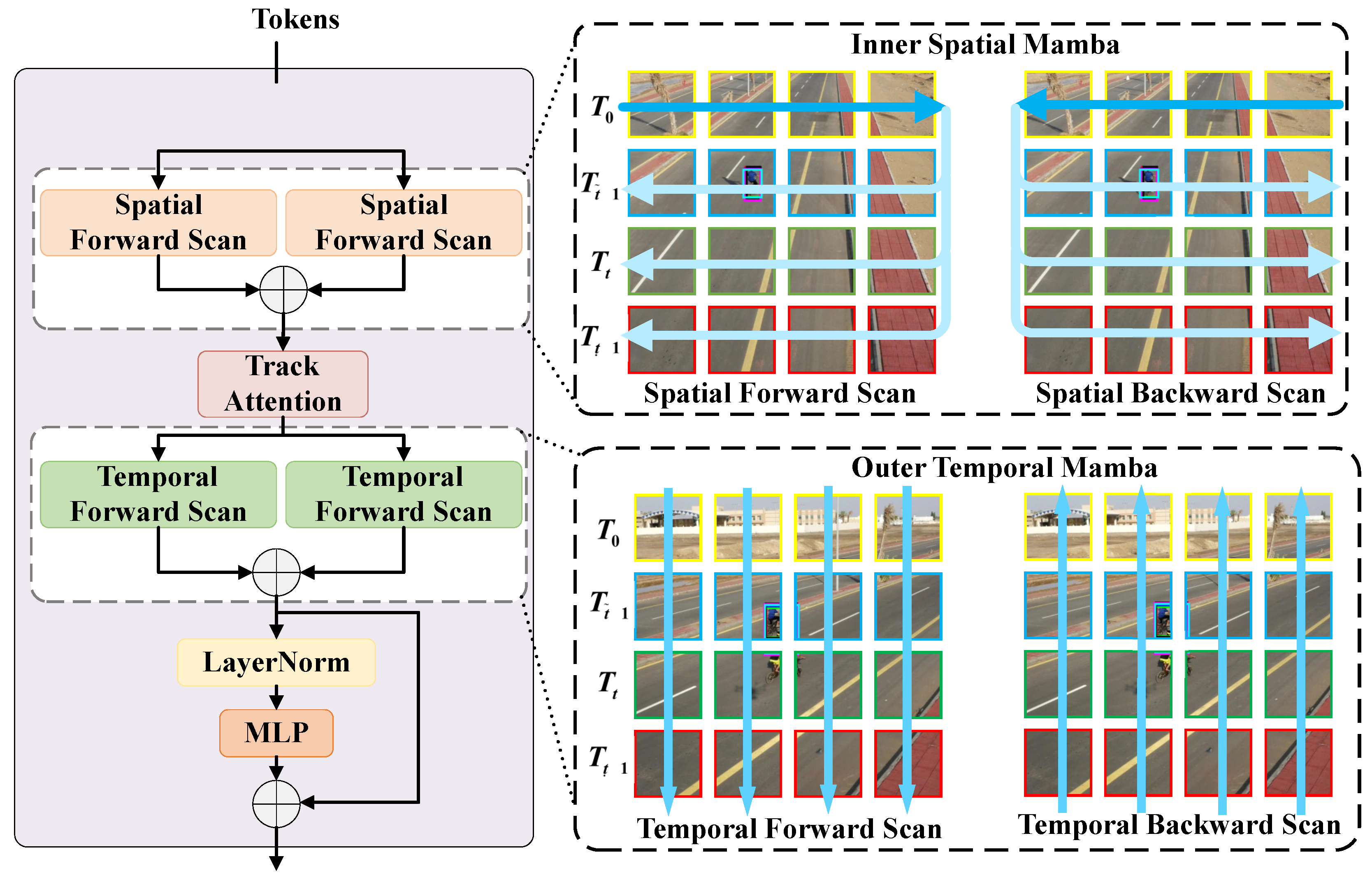

- Bidirectional Spatio-Temporal Mamba Module: It captures local spatial features of small targets through horizontal–vertical bidirectional scanning and models dynamic motion trends via forward–backward temporal scanning, achieving synergistic modeling of spatial details and temporal dynamics.

- (2)

- Dynamic Template Fusion module based on Adaptive Attention: It introduces a triple safety verification mechanism (response peak, consistency, and motion stability) and a size-aware attention fusion strategy to suppress erroneous updates and cumulative error propagation in complex backgrounds.

- (3)

- Small-Target-Aware Context Prediction Head: It employs a Gaussian-weighted small-target prior to guide feature fusion and optimizes the loss function specifically for small targets, thereby enhancing localization accuracy under complex backgrounds.

- (4)

- Extensive experiments demonstrate that MSTFT achieves state-of-the-art performance on multiple UAV tracking benchmarks, attaining a superior balance among accuracy, robustness, and efficiency, and providing an effective and efficient solution for UAV small-target tracking.

2. Related Work

2.1. UAV Visual Tracking

2.2. Visual Tracking Based on Mamba Models

2.3. Dynamic Template Update-Based Context-Aware Modeling

3. Mamba-Based Spatio-Temporal Fusion Tracker (MSTFT) Architecture

3.1. Bidirectional Spatio-Temporal Mamba (Bi-STM) Module

3.1.1. Bidirectional Scanning Mechanism

3.1.2. Adaptive Fusion of Spatio-Temporal Features

3.2. Dynamic Template Fusion Module Based on Adaptive Attention (DTF-AA)

3.2.1. Triple Safety Verification Mechanism for Template Update

3.2.2. Size-Aware Adaptive Attention Fusion

3.3. Small-Target-Aware Context Prediction Head (CAPH)

3.3.1. Small-Target Prior-Guided Feature Fusion

3.3.2. Loss Function Optimized for Small Targets

3.4. Overall Framework and Core Algorithm

- Vision Mamba Backbone: We adopt the open-source Vision Mamba (ViM) implementation from [33] with input resolution of pixels.

- Cross-Correlation: Computed using standard 2D cross-correlation in PyTorch 2.1.0.

- SSIM Calculation: Computed via torchmetrics library with patches resized to .

| Algorithm 1 Mamba-based Spatio-Temporal Fusion Tracker (MSTFT) | |

| |

| |

| # Fuse current and historical features |

| |

| # Adaptive multi-scale fusion |

| |

| # Peak sufficiency |

| # Temporal consistency |

| |

| # Bypass for initial frames |

| |

| # Motion stability |

| |

| # Conservative update |

| |

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Datasets

4.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

4.1.3. Implementation Details

4.2. Comparative Experiments and Results Analysis

4.2.1. Overall Performance Comparison

- General Scenario Performance. On the UAV123 dataset, MSTFT achieved a success AUC of 79.4% and a precision of 84.5% (see Table 1), outperforming the Mamba-based tracker TrackingMiM (70.8% success AUC, 83.5% precision) by 8.6 and 1.0 percentage points, respectively. This leading performance is also reflected in the visualization results of Figure 4: MSTFT’s precision curve (left subfigure) and success curve (right subfigure) both maintain the highest position across all threshold ranges. This improvement is driven by two core modules: the Bi-STM module uses a horizontal–vertical bidirectional spatial scanning strategy, reorganizing features in small target regions via windows to suppress background noise (e.g., farmland textures) and enhance discriminative feature extraction; the CAPH module introduces a Gaussian-weighted prior to focus on target core areas (e.g., pedestrian heads in urban scenes), avoiding feature dilution in cluttered backgrounds.

- Low-Frame-Rate and Large-Displacement Robustness. On the UAV123@10fps benchmark, MSTFT achieved a success AUC of 76.5% and a precision of 84.1% (Table 1), surpassing the Transformer-based representative STARK (63.8% AUC, 82.5% precision) by 12.7 and 1.6 percentage points. The advantage in low-frame-rate scenarios is further verified by the curve trend in Figure 4: even at small location error thresholds (≤10 pixels), MSTFT’s precision remains higher than other competitors, indicating strong resistance to inter-frame displacement. This benefit comes from the Bi-STM module’s forward-backward temporal scanning: forward scanning leverages historical frames ( to ) to model motion inertia, while backward scanning integrates future frame information ( to ) via caching, correcting deviations from sudden UAV attitude changes. This allows robust handling of inter-frame displacements exceeding 5% of the image size under 10 FPS conditions.

- Long-Term Tracking Stability. On the UAV20L dataset (designed for long-term tracking tasks), MSTFT achieved a success AUC of 75.8% and a precision of 83.6% (Table 1), a 7.2 percentage point improvement in AUC over the Mamba-based TADMT (68.6%). As shown in Figure 4, MSTFT’s success curve maintains a significant lead when the overlap threshold is between 0.5 and 0.8, which is a key range for evaluating long-term tracking stability. Its robustness stems from the DTF-AA module’s triple adaptive verification: response peak verification () filters low-confidence updates (e.g., foggy frames); response consistency verification () ensures temporal feature coherence to avoid background clutter inclusion; motion stability verification () rejects occlusion-induced erroneous features. This multi-verification synergy suppresses error accumulation in long-term tracking.

4.2.2. Performance Analysis Under Different Challenge Attributes

- Occlusion Robustness. In scenarios involving occlusion, MSTFT achieved a success AUC of under full occlusion (Table 2), exceeding TrackingMiM by percentage points. For partial occlusion, it reached , outperforming all compared methods. As visualized in Figure 6, MSTFT’s success curve retains a clear lead within the 0.4–0.7 overlap threshold range, which is critical for evaluating occlusion recovery. This capability is enabled by the motion stability verification mechanism in the DTF-AA module, which computes the mean structural similarity index across the most recent 3 frames and suspends template updates when this value falls below . Concurrently, the system retains only the initial template and reliable dynamic templates acquired before occlusion, effectively preventing the assimilation of corrupted features. Experimental results confirm that MSTFT’s template update error rate during full occlusion is only , substantially lower than the observed in MambaLCT.

- Resistance to Background Clutter. When confronted with background clutter, MSTFT attained a success AUC of (Table 2), surpassing TrackingMiM by percentage points. Figure 5 shows that its precision remains above even at small location error thresholds (≤10 pixels), highlighting strong clutter rejection. This performance is attributed to the synergistic operation of the Bi-STM and DTF-AA modules: the Bi-STM captures the target’s motion trend (e.g., a pedestrian’s walking direction in a crowd) through temporal dynamic modeling, distinguishing it from static distractors; the DTF-AA employs a size-aware attention mechanism that dynamically adjusts the attention window relative to the target size (e.g., a pixel window for a pixel target), thereby minimizingM interference from semantically similar background objects during template fusion.

4.3. Ablation Study

4.3.1. Study of the Components

4.3.2. Memory Consumption Analysis of Bidirectional Scanning

- Spatial Scanning Overhead: As summarized in Table 4, full bidirectional spatial scanning (H + V) incurs an overhead of 15 MB compared to the average unidirectional scan (710 MB vs. ∼696.5 MB). This cost arises from maintaining parallel computation graphs for both scanning directions.

- Temporal Scanning Overhead: Bidirectional temporal scanning (F + B) introduces a 20 MB overhead versus its unidirectional counterpart (725 MB vs. ∼706 MB). The larger increment is attributed to the caching mechanism required for future-frame context in backward scanning.

- Synergistic Integration: The complete Bi-STM module (750 MB) consumes less memory than the sum of its isolated spatial (710 MB) and temporal (725 MB) bidirectional components. This indicates efficient memory sharing, particularly in shared normalization layers and residual connections.

- Architectural Efficiency: Despite the advanced bidirectional design, MSTFT maintains high memory efficiency (780 MB). This contrasts sharply with Transformer-based trackers, whose quadratic attention mechanism demands significantly more memory. The linear complexity of the Mamba architecture is key to this efficiency.

4.3.3. Ablation Analysis of Triple Safety Verification Mechanism (TSVM)

- Variant A (w/o TSVM): Employs the standard size-aware attention with a naïve template update strategy (update coefficient ) and without any safety verification.

- Variant B (w/TSVM): Incorporates the complete TSVM, comprising response peak assessment, temporal consistency checking, and motion stability evaluation (parameters: , , ).

4.3.4. Ablation Analysis of Individual Loss Function Modifications

- Improved Focal Loss. Compared to the baseline, using only the improved Focal Loss increases AUC by 3.6 percentage points, reduces localization error by 1.3 pixels, and improves AIoU by 3.5%. This confirms that the adjusted focusing parameter () and the Gaussian-shaped classification label more effectively suppress background interference, thereby enhancing the discrimination of sparse small-target features.

- Optimized Regression Loss. Employing only the optimized regression loss yields even greater gains: a 3.9-point AUC improvement, a 2.5-pixel reduction in ALE, and a 4.1% increase in AIoU versus the baseline. The integration of GIoU and an area-based penalty term successfully mitigates the evaluation bias inherent to small target sizes, leading to more precise bounding box regression.

- Synergistic Effect. The full proposed loss achieves the best performance across all metrics (e.g., 71.6% AUC), with total gains exceeding the simple sum of individual improvements. This synergy occurs because the improved Focal Loss provides better foreground-background distinction and region priors, which in turn enables the optimized regression loss to perform more accurate localization. The components are mutually reinforcing, maximizing overall tracking performance for small UAV targets.

4.4. Qualitative Analysis and Visual Verification

4.4.1. Low-Resolution Small Target Scenario

4.4.2. Low-Frame-Rate and Fast-Motion Scenario

4.4.3. Long-Sequence Full Occlusion Scenario

4.5. Computational Efficiency Analysis

4.6. Analysis of Target Size Generalization

4.7. Power and Energy Efficiency for Onboard UAV Deployment

5. Discussion

Architectural Choices and Deployment Cost

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under the Curve |

| Bi-STM | Bidirectional Spatio-Temporal Mamba module |

| CAPH | Small-Target-Aware Context Prediction Head |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DCF | Discriminative Correlation Filter |

| DTF-AA | Dynamic Template Fusion module based on Adaptive Attention |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| GIoU | Generalized Intersection over Union |

| IoU | Intersection over Union |

| MSTFT | Mamba-Based Spatio-Temporal Fusion Tracker |

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| ViM | Vision Mamba |

References

- Haque, A.; Chowdhury, M.N.U.R.; Hassanalian, M. A Review of Classification and Application of Machine Learning in Drone Technology. AI Comput. Sci. Robot. Technol. 2025, 4, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, C.; Huang, H.; Lyu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Huang, C.; Huang, H. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Search and Rescue: A Survey. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Othman, N.Q.H.; Li, Y.; Alsharif, M.H.; Khan, M.A. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): Practical Aspects, Applications, Open Challenges, Security Issues, and Future Trends. Intell. Serv. Rob. 2023, 16, 109–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laghari, A.A.; Jumani, A.K.; Laghari, R.A.; Li, H.; Karim, S.; Khan, A.A. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Advances in Object Detection and Communication Security Review. Cognit. Rob. 2024, 4, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariante, G.; Core, G.D.; Ariante, G.; Core, G.D. Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UASs): Current State, Emerging Technologies, and Future Trends. Drones 2025, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quamar, M.M.; Al-Ramadan, B.; Khan, K.; Shafiullah, M.; Ferik, S.E.; Quamar, M.M.; Al-Ramadan, B.; Khan, K.; Shafiullah, M.; Ferik, S.E. Advancements and Applications of Drone-Integrated Geographic Information System Technology—A Review. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, L.; Xu, C.; Shang, Y.; Jin, P.; Cao, C.; Shen, T. Progress and Perspectives on UAV Visual Object Tracking. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 20214–20239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Dong, S.; Zhang, J.; Xu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zheng, Y. Adaptive Spatial Regularization Correlation Filters for UAV Tracking. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 7867–7877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Xu, F.; Wang, Z.; Sun, M.; Zhao, H. A Context Constraint and Sparse Learning Based on Correlation Filter for High-Confidence Coarse-to-Fine Visual Tracking. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 268, 126225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Liu, M. BSTrack: Robust UAV Tracking Using Feature Extraction of Bilateral Filters and Sparse Attention Mechanism. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 267, 126202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Vohra, R.; Jain, R.; Li, M.; Gan, C.; Jain, D.K. Correlation Filter Based Single Object Tracking: A Review. Inf. Fusion 2024, 112, 102562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Wang, S. An Overview of Correlation-Filter-Based Object Tracking. IEEE Trans. Comput. Social Syst. 2022, 9, 18–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Li, W.; Hong, D.; Tao, R.; Du, Q. Deep Learning for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-Based Object Detection and Tracking: A Survey. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2022, 10, 91–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvasti-Zadeh, S.M.; Cheng, L.; Ghanei-Yakhdan, H.; Kasaei, S. Deep Learning for Visual Tracking: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 3943–3968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, L.; Wang, D.; Bai, Y.; Chen, P.; Liu, F. Deep Learning in Visual Tracking: A Review. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2023, 34, 5497–5516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Li, F.; Yang, W. Siamada: Visual Tracking Based on Siamese Adaptive Learning Network. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 7639–7656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabeeh Hasan Allak, A.; Yi, J.; Al-Sabbagh, H.M.; Chen, L. Siamese Neural Networks in Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Target Tracking Process. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 24309–24322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.C.; Huh, J.H.; Kim, J.C.; Lim, S.C.; Huh, J.H.; Kim, J.C. Siamese Trackers Based on Deep Features for Visual Tracking. Electronics 2023, 12, 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, K.; Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Chen, X.; Guo, J.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Xiao, A.; Xu, C.; Xu, Y.; et al. A Survey on Vision Transformer. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 87–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ni, X.; Yuan, L.; Lv, K. Efficient Single-Object Tracker Based on Local-Global Feature Fusion. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 1114–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Liang, M.; Huang, S.; Ning, J. Exploring the Feature Extraction and Relation Modeling for Light-Weight Transformer Tracking. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2024, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Leonardis, A., Ricci, E., Roth, S., Russakovsky, O., Sattler, T., Varol, G., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 110–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yan, B.; Zhu, J.; Lu, H.; Ruan, X.; Wang, D. High-Performance Transformer Tracking. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 8507–8523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Fan, H.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Ling, H. SwinTrack: A Simple and Strong Baseline for Transformer Tracking. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 16743–16754. [Google Scholar]

- Kugarajeevan, J.; Kokul, T.; Ramanan, A.; Fernando, S. Transformers in Single Object Tracking: An Experimental Survey. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 80297–80326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, D.; Zhang, L.; Chen, T.; Wang, Z.; Ye, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, D.; et al. A Survey on Visual Mamba. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 5683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Du, B.; Chen, H. Visual Mamba: A Survey and New Outlooks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.18861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhong, B.; Liang, Q.; Li, G.; Mo, Z.; Song, S. Mambalct: Boosting Tracking via Long-Term Context State Space Model. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 4986–4994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Chen, C.; Li, J.; Yu, G.; Song, H.; Liu, X.; Cui, J.; Zhang, H. TrackingMiM: Efficient Mamba-in-Mamba Serialization for Real-Time UAV Object Tracking. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2507.01535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhong, B.; Liang, Q.; Li, N.; Mo, Z.; Song, S. Robust Tracking via Mamba-Based Context-Aware Token Learning. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 8727–8735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, M.; Peng, J.; He, Q.; Peng, B.; Chen, H.; Chi, M.; Liu, C.; Benediktsson, J.A. MM-Tracker: Motion Mamba for UAV-Platform Multiple Object Tracking. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2025, 39, 9409–9417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhou, L.; Jin, P.; Qu, X.; Zhong, H.; Song, H.; Shen, T. TrackingMamba: Visual State Space Model for Object Tracking. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2024, 17, 16744–16754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Xie, L.; Wang, Y.; Ye, Q.; Liu, Y. VMamba: Visual State Space Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.10166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Liao, B.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, X.; Liu, W.; Wang, X. Vision Mamba: Efficient Visual Representation Learning with Bidirectional State Space Model. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.09417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.F.; Wu, X.J.; Xu, T.; Feng, Z.H.; Kittler, J. Complementary Discriminative Correlation Filters Based on Collaborative Representation for Visual Object Tracking. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 31, 557–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Peng, H. Deeper and Wider Siamese Networks for Real-Time Visual Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVP Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2019), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 4591–4600. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Ma, G.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L. A Deep Temporal-Spectral-Spatial Anchor-Free Siamese Tracking Network for Hyperspectral Video Object Tracking. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5539216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cen, M.; Jung, C. Fully Convolutional Siamese Fusion Networks for Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Athens, Greece, 7–10 October 2018; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 3718–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertinetto, L.; Valmadre, J.; Henriques, J.F.; Vedaldi, A.; Torr, P.H.S. Fully-Convolutional Siamese Networks for Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2016 Workshops, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 8–10 October 2016; Hua, G., Jégou, H., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 850–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Liao, D.; Huang, F.; Qiu, Z.; Shu, X.; Tian, C.; Liu, Q. Hierarchical Attention Siamese Network for Thermal Infrared Target Tracking. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 5032411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Wang, Q.; Dou, J.; Dou, L. Learning Saliency-Awareness Siamese Network for Visual Object Tracking. J. Visual Commun. Image Represent. 2024, 103, 104237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Huang, J.; Liao, Y.; Song, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Yang, J. Light Siamese Network for Long-Term Onboard Aerial Tracking. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2024, 62, 5623415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Z.; Gao, D.; Fan, B. Long-Term Object Tracking Based on Joint Tracking and Detection Strategy with Siamese Network. Multimedia Syst. 2024, 30, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, D. SiamVGG: Visual Tracking Using Deeper Siamese Networks. arXiv 2022, arXiv:1902.02804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Zhong, B.; Li, G.; Zhang, S.; Ji, R.; Tang, Z.; Li, X. SiamBAN: Target-Aware Tracking with Siamese Box Adaptive Network. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2023, 45, 5158–5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wu, W.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, F.; Xing, J.; Yan, J. Siamrpn++: Evolution of Siamese Visual Tracking with Very Deep Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 4282–4291. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Yu, G. SiamFC++: Towards Robust and Accurate Visual Tracking with Target Estimation Guidelines. roc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 12549–12556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yan, B.; Zhu, J.; Wang, D.; Yang, X.; Lu, H. Transformer Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 8126–8135. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, B.; Peng, H.; Fu, J.; Wang, D.; Lu, H. Learning Spatio-Temporal Transformer for Visual Tracking. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 10448–10457. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Xu, T.; Xie, F.; Wu, J.; Yang, W. TATrack: Target-Oriented Adaptive Vision Transformer for UAV Tracking. Neural Netw. 2026, 193, 108067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, D.; Choi, W.; Lee, S.; Yoo, B.; Yang, E.; Hwang, S. BackTrack: Robust Template Update via Backward Tracking of Candidate Template. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2308.10604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Liu, D.; Muhammad, K.; Ding, W. Effective Template Update Mechanism in Visual Tracking with Background Clutter. Neurocomputing 2021, 458, 615–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Liu, K.; Zhiyong, A.; Wang, L.; Li, Y.; Xiang, Z. A Novel Incremental Multi-Template Update Strategy for Robust Object Tracking. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 162668–162682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Gonzalez-Garcia, A.; Weijer, J.V.D.; Danelljan, M.; Khan, F.S. Learning the Model Update for Siamese Trackers. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 4010–4019. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Jiang, C.; Wang, L.; Wu, G. Mixformer: End-to-End Tracking with Iterative Mixed Attention. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 13608–13618. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Peng, H.; Wang, D.; Lu, H.; Hu, H. Seqtrack: Sequence to Sequence Learning for Visual Object Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 14572–14581. [Google Scholar]

- Hosseini, S.M.H.; Hassanpour, M.; Masoudnia, S.; Iraji, S.; Raminfard, S.; Nazem-Zadeh, M. Cttrack: A Cnn+ Transformer-Based Framework for Fiber Orientation Estimation & Tractography. Neurosci. Inf. 2022, 2, 100099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, C.; Danelljan, M.; Paudel, D.P.; Van Gool, L. Learning Target Candidate Association to Keep Track of What Not to Track. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 13444–13454. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, L.; Zhong, B.; Liang, Q.; Li, N.; Zhang, S.; Li, X. Explicit Visual Prompts for Visual Object Tracking. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 4838–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhong, B.; Liang, Q.; Mo, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, X. Odtrack: Online Dense Temporal Token Learning for Visual Tracking. Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2024, 38, 7588–7596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Zhong, B.; Mo, Z.; Zhang, S.; Shi, L.; Song, S.; Ji, R. Autoregressive Queries for Adaptive Tracking with Spatio-Temporal Transformers. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, US, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 19300–19309. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, C.; Cao, Z.; Li, Y.; Ye, J.; Feng, C. Onboard Real-Time Aerial Tracking with Efficient Siamese Anchor Proposal Network. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 5606913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yin, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X. Robust UAV Tracking via Information Synergy Fusion and Multi-Dimensional Spatial Perception. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 39886–39900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Chen, C.; Yu, X.; Pang, S.; Qin, H. SiamTADT: A Task-Aware Drone Tracker for Aerial Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 3708–3722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Zhong, B.; Liang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Li, N.; Xue, Y.; Song, S. Similarity-Guided Layer-Adaptive Vision Transformer for UAV Tracking. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.06625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Chang, H.; Ma, B.; Shan, S.; Chen, X. Joint Feature Learning and Relation Modeling for Tracking: A One-Stream Framework. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2022, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Avidan, S., Brostow, G., Cissé, M., Farinella, G.M., Hassner, T., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 341–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Wang, Z.; Sun, Q.; Cheng, G.; Ning, J. Modeling of Multiple Spatial-Temporal Relations for Robust Visual Object Tracking. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2024, 33, 5073–5085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, G.; Zhou, P.; Yadikar, N.; Aysa, A.; Ubul, K. Mamba Meets Tracker: Exploiting Token Aggregation and Diffusion for Robust Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Tracking. Complex Intell. Syst. 2025, 11, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm Type | Algorithm Name | Year | UAV123 (AUC/Precision) | UAV123@10fps (AUC/Precision) | UAV20L (AUC/Precision) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Siamese | SiamFC [38] | 2016 | 48.5/64.8 | 47.2/67.8 | 40.2/59.9 |

| SiamRPN++ [45] | 2019 | 73.2/79.5 | 55.5/69.0 | 52.8/69.6 | |

| SiamBAN [44] | 2020 | 68.0/77.6 | 59.8/78.4 | 58.3/75.9 | |

| SiamAPN [61] | 2022 | 57.5/76.6 | 56.6/75.2 | 53.9/72.1 | |

| SiamFM [62] | 2025 | 62.8/82.0 | -/- | 58.5/76.8 | |

| SiamTADT [63] | 2025 | 65.1/84.2 | 64.0/83.4 | 64.3/83.1 | |

| Transformer- based | TransT [47] | 2021 | 62.9/81.8 | 61.2/79.2 | 53.7/69.6 |

| STARK [48] | 2022 | 74.4/80.4 | 63.8/82.5 | 60.1/77.3 | |

| OSTrack [65] | 2023 | 76.3/80.4 | 63.7/79.7 | 63.0/78.2 | |

| MCTrack [66] | 2024 | 65.2/79.1 | 64.1/80.1 | 65.2/79.5 | |

| SGLATrack [64] | 2025 | 66.9/84.2 | 64.3/81.7 | 64.0/79.2 | |

| Mamba- based | MambaLCT [27] | 2025 | 76.7/81.5 | 68.5/80.3 | 65.2/81.5 |

| TrackingMiM [28] | 2025 | 70.8/83.5 | 69.1/82.6 | 66.5/83.2 | |

| TADMT [67] | 2025 | 68.2/83.8 | 69.1/83.4 | 68.6/81.9 | |

| TemTrack [29] | 2025 | 77.5/83.1 | 69.3/83.7 | 69.7/82.3 | |

| MSTFT | - | 79.4/84.5 | 76.5/84.1 | 75.8/83.6 |

| Challenge Attribute | Sample Sequences | SiamRPN++ | OSTrack | TrackingMiM | MSTFT | Core Contribution Module |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small Target | 42 | 52.1 | 58.4 | 62.3 | 70.5 | CAPH |

| Fast Motion | 28 | 64.8 | 69.7 | 65.7 | 73.3 | Bi-STM |

| Low Resolution | 35 | 46.8 | 57.8 | 59.2 | 61.1 | CAPH+Bi-STM |

| Partial Occlusion | 73 | 61.7 | 64.3 | 66.1 | 69.2 | DTF-AA |

| Full Occlusion | 33 | 43.5 | 45.7 | 47.9 | 51.2 | DTF-AA |

| Background Clutter | 21 | 48.8 | 55.9 | 58.3 | 60.9 | Bi-STM+DTF-AA |

| Exp.Config. | AUC (%) | Prec (%) | Small Target AUC (%) | Fast Motion AUC (%) | Full Occlusion AUC (%) | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | Speed (FPS) | GPU Mem (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 (Baseline) | 65.8 | 76.3 | 58.2 | 58.2 | 45.0 | 70 | 22.3 | 52 | 680 |

| A2 (+Bi-STM) | 70.3 | 80.5 | 62.7 | 66.5 | 49.7 | 72 | 24.5 | 48 | 710 |

| A3 (+DTF-AA) | 72.9 | 83.2 | 65.3 | 68.9 | 54.4 | 73 | 25.7 | 46 | 750 |

| A4 (MSTFT) | 75.2 | 84.5 | 71.6 | 73.3 | 58.7 | 74 | 26.8 | 45 | 780 |

| Configuration | Scanning Strategy | Components Included | Peak Memory (MB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (A1) | No scanning (backbone only) | Basic Prediction Head | 680 |

| Spatial Only | Unidirectional Horizontal | Bi-STM (Spatial: H-only) | 695 |

| Spatial Only | Unidirectional Vertical | Bi-STM (Spatial: V-only) | 698 |

| Spatial Only | Bidirectional (H + V) | Bi-STM (Spatial: Full) | 710 |

| Temporal Only | Unidirectional Forward | Bi-STM (Temporal: Forward) | 705 |

| Temporal Only | Unidirectional Backward | Bi-STM (Temporal: Backward) | 707 |

| Temporal Only | Bidirectional (F + B) | Bi-STM (Temporal: Full) | 725 |

| Full Bi-STM | Full Bidirectional | Complete Bi-STM | |

| A3 (+DTF-AA) | Full Bidirectional | Bi-STM + DTF-AA | 770 |

| Full MSTFT (A4) | Full Bidirectional | All Components | 780 |

| Model Variant | Additional Params (K) | Additional FLOPs (G/frame) | Speed Loss (FPS) | Full Occlusion AUC (%) | Robustness Gain (AUC ↑ %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variant A (w/o TSVM) | 0 | 0.00 | 0.0 | 49.9 | 0.0 |

| Variant B (w/TSVM) | 34.2 | 1.98 | 3.6 | 58.6 | 8.7 |

| Model Variant | Small-Target AUC (%) | Average Localization Error (Pixel) | Average IoU (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variant 1 (Baseline Loss) | 65.3 | 12.8 | 58.2 |

| Variant 2 (Only Improved Focal Loss) | 68.9 | 11.5 | 61.7 |

| Variant 3 (Only Optimized Regression Loss) | 69.2 | 10.3 | 62.3 |

| Variant 4 (Full Proposed Loss) | 71.6 | 8.7 | 65.1 |

| Algorithm Name | Params (M) | FLOPs (G) | Speed (FPS) | GPU Mem (MB) | Long-seq Inference Time (s/8000 frames) | Complexity Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SiamRPN++ [45] | 188 | 35.8 | 32 | 2236 | 250 | Linear (O (HW)) |

| OSTrack [65] | 113 | 45.2 | 18 | 2943 | 444 | Quadratic (O ((HW)2)) |

| MambaLCT [27] | 85 | 22.4 | 38 | 1624 | 210 | Linear (O (HW)) |

| TrackingMiM [28] | 97 | 31.2 | 35 | 1952 | 228 | Linear (O (HW)) |

| TADMT [67] | 102 | 33.5 | 30 | 2015 | 266 | Linear (O (HW)) |

| MSTFT | 70 | 26.8 | 45 | 780 | 178 | Linear (O (HW)) |

| Algorithm | Small Targets | Medium Targets | Large Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| SiamRPN++ [45] | 52.1 | 71.8 | 78.5 |

| OSTrack [65] | 58.4 | 73.2 | 79.1 |

| MambaLCT [27] | 62.3 | 74.9 | 80.4 |

| MSTFT (Ours) | 70.5 | 76.8 | 81.2 |

| Hardware Platform | P_avg (W) | P_peak (W) | E_frame (J/Frame) | Endurance (200 Wh, h) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NVIDIA Jetson AGX Orin | 28.7 | 41.3 | 0.64 | ≈6.97 |

| NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX | 14.3 | 22.8 | 0.33 | ≈13.99 |

| Characteristic | CNN-Based | Transformer-Based | Mamba-Based (Ours) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Context | local window | Self-attention | Selective SSM |

| Theoretical Complexity | |||

| Memory Efficiency | High | Large attention maps | Compact states |

| Suitability for Small Targets | Needs multi-scale tricks | Global view | Dynamic focus |

| Real-time Edge Feasibility | High | Challenging | High |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Sun, K.; Zhang, H.; Chen, H. MSTFT: Mamba-Based Spatio-Temporal Fusion for Small Object Tracking in UAV Videos. Electronics 2026, 15, 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020256

Sun K, Zhang H, Chen H. MSTFT: Mamba-Based Spatio-Temporal Fusion for Small Object Tracking in UAV Videos. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):256. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020256

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Kang, Haoyang Zhang, and Hui Chen. 2026. "MSTFT: Mamba-Based Spatio-Temporal Fusion for Small Object Tracking in UAV Videos" Electronics 15, no. 2: 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020256

APA StyleSun, K., Zhang, H., & Chen, H. (2026). MSTFT: Mamba-Based Spatio-Temporal Fusion for Small Object Tracking in UAV Videos. Electronics, 15(2), 256. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020256