Dynamic Time Warping-Based Differential Protection Scheme for Transmission Lines in Flexible Fractional Frequency Transmission Systems

Abstract

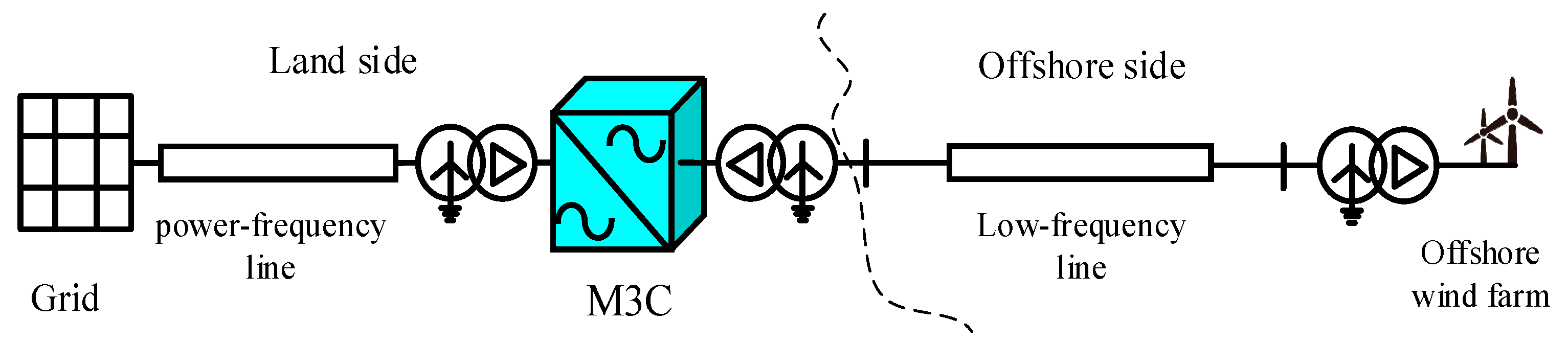

1. Introduction

- Adaptability analysis of relay protection

- Novel relay protection schemes

- In-depth Fault Characteristic Analysis: We present a comprehensive analysis of the M3C’s fault ride-through strategy, explicitly establishing the relationship between its control actions and the resulting post-fault current trends on both ends of the transmission line.

- Novel DTW-based Protection Principle: We propose a new protection criterion that utilizes the DTW algorithm to quantify waveform trends by comparing post-fault currents to pre-fault references. This method inherently enables fault identification and phase selection without relying on strict synchronization between line terminals.

- Comprehensive Validation under Challenging Conditions: We rigorously demonstrate the scheme’s efficacy and robustness through extensive simulations, confirming its high reliability and speed across a wide range of fault scenarios, including those with high impedance and noise.

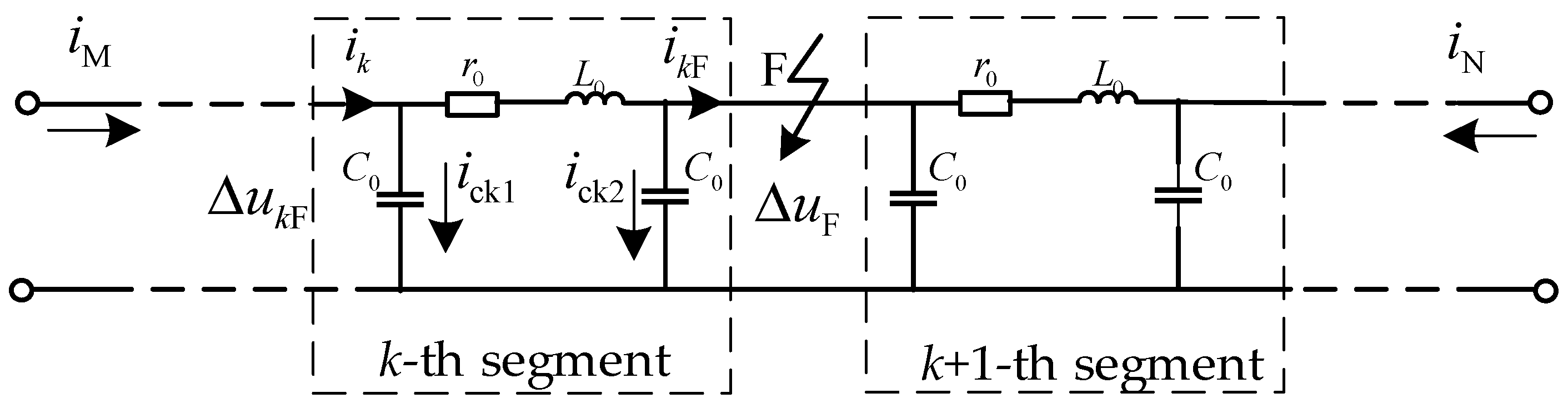

2. Fault Analysis in Transmission Lines

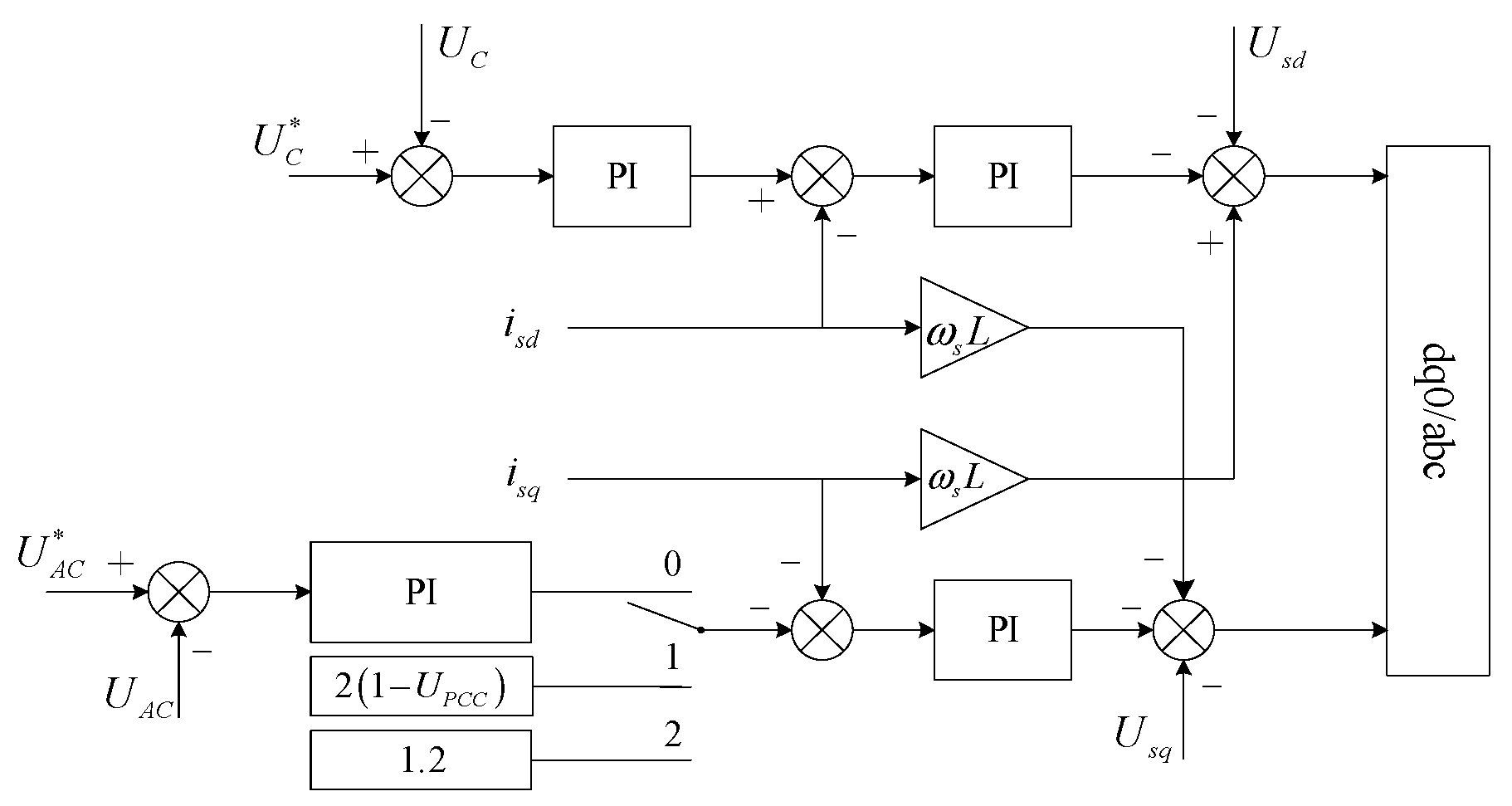

2.1. M3C Fault Ride-Through Control Strategy

- Mode 0: Steady-state operation.

- Mode 1: Activated in response to minor voltage dips.

- Mode 2: Activated in response to deep voltage sags.

2.2. Analysis of Fault Current Characteristics

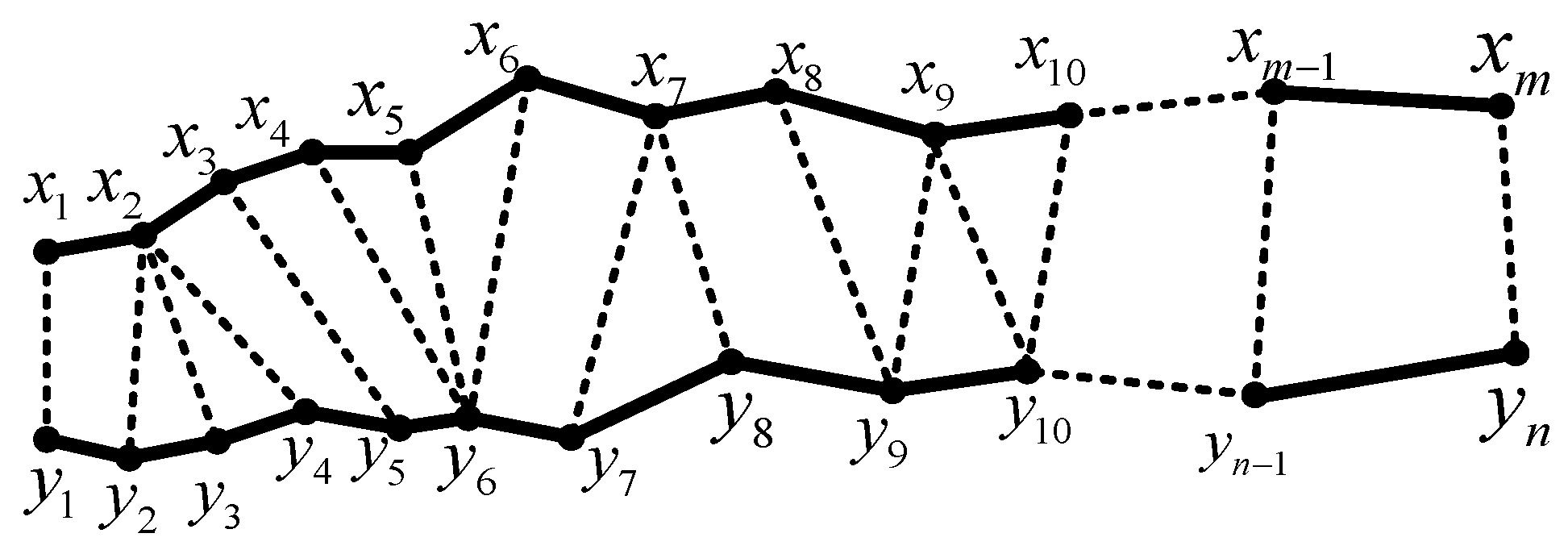

3. DTW-Based Line Protection Scheme

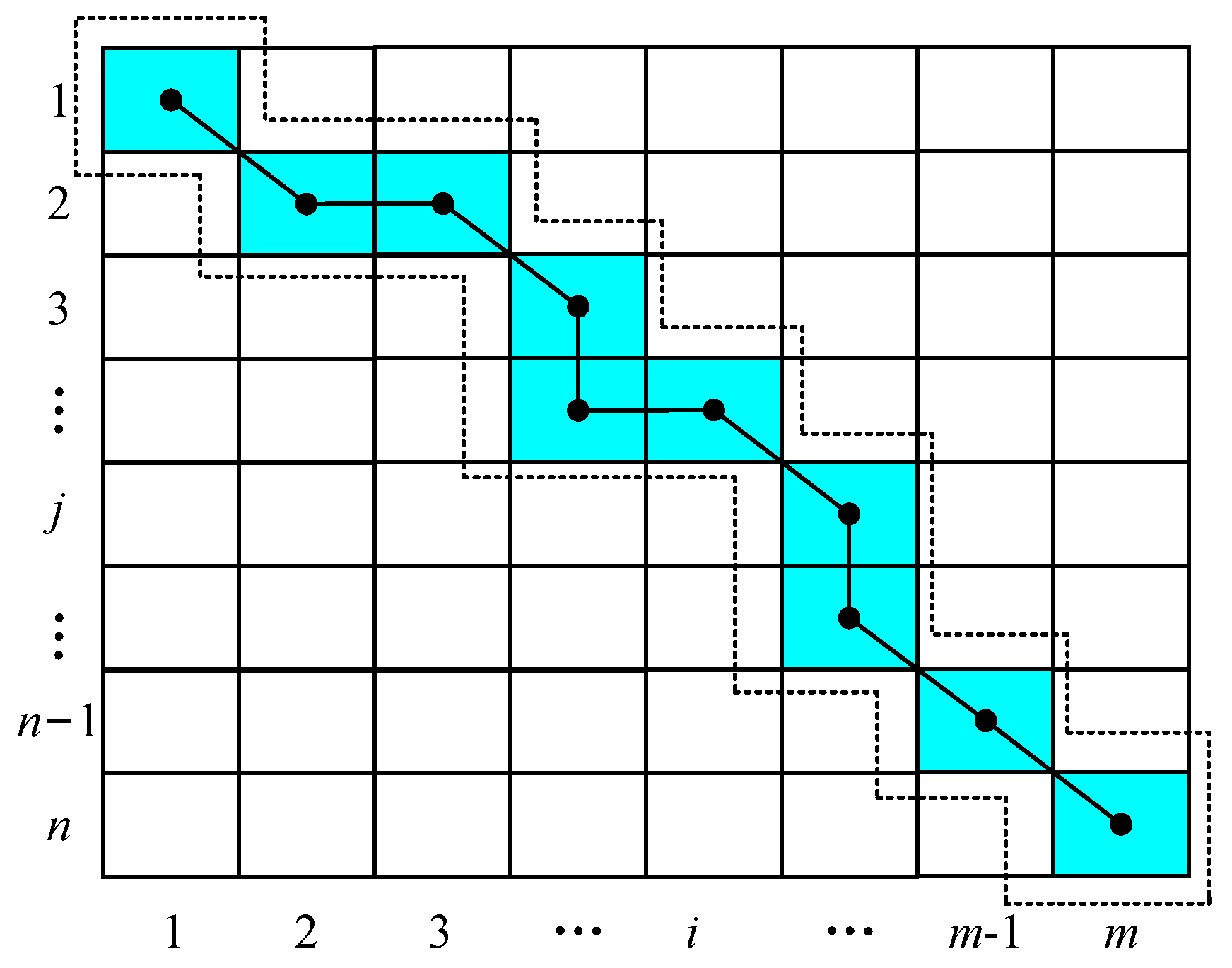

3.1. Identifying Current Characteristics on Both Sides Using DTW

3.2. Development of the Protection Criterion

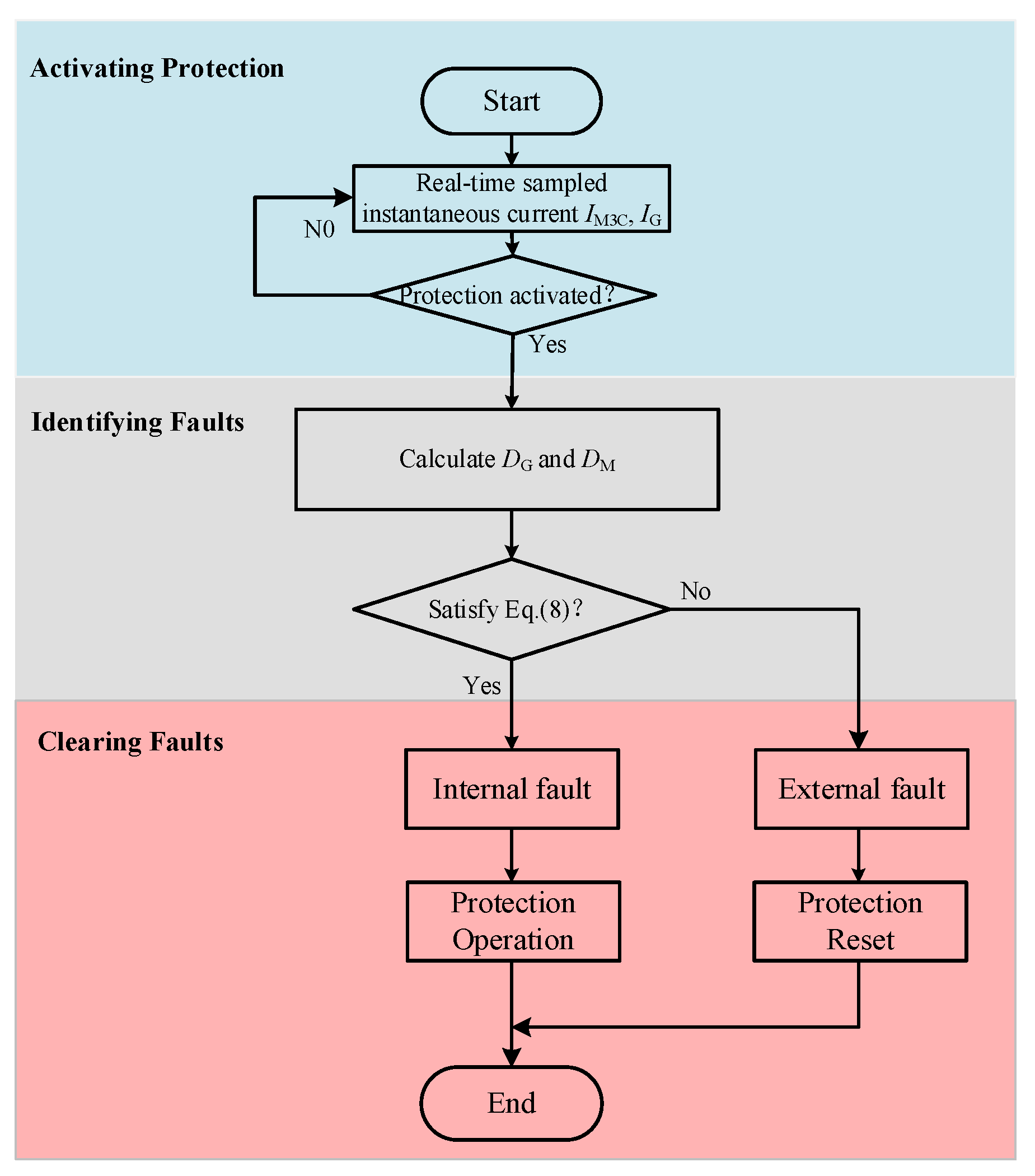

3.3. Protection Logic Flowchart

4. Simulation Analysis and Discussion

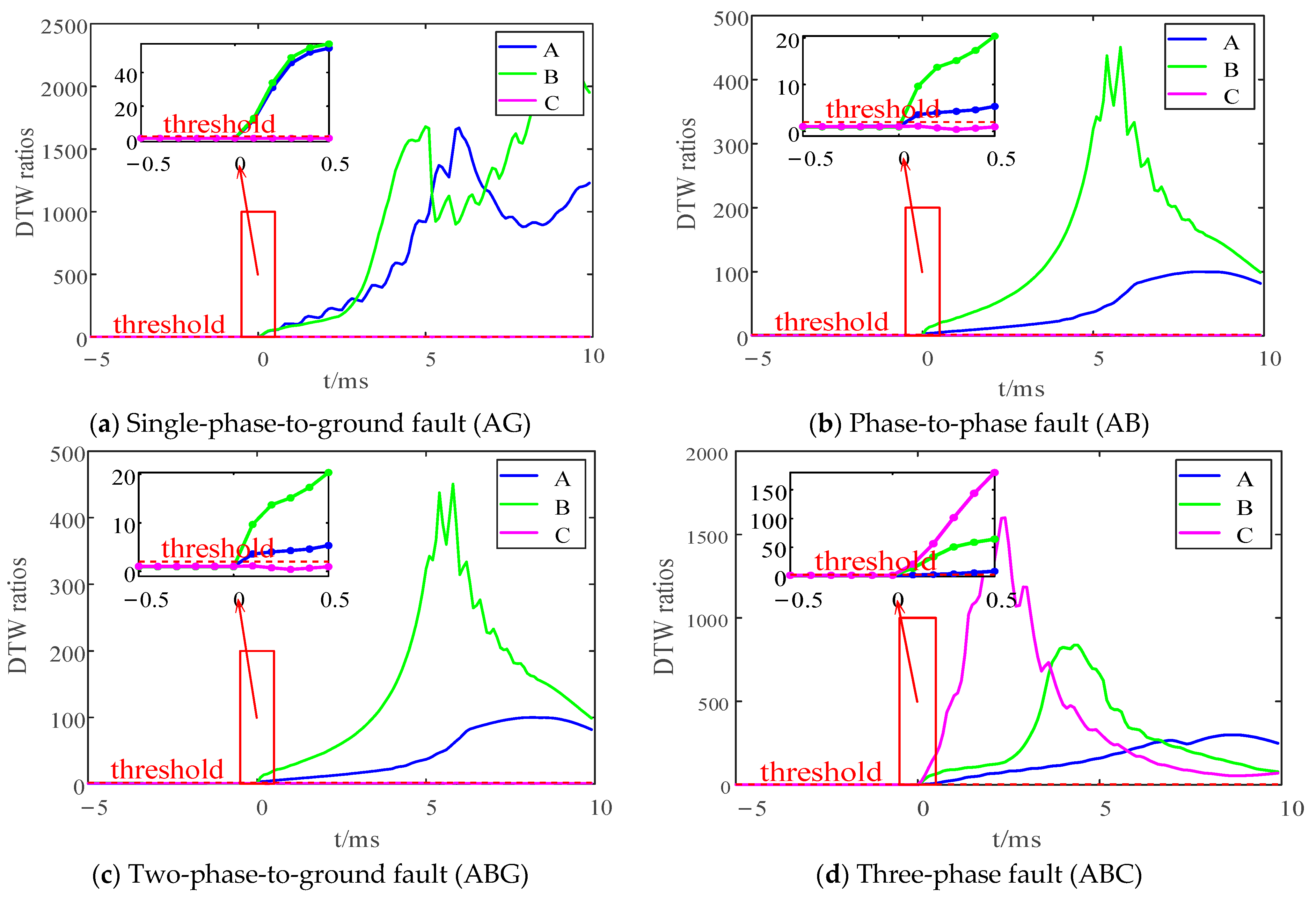

4.1. Analysis of Internal and External Fault Scenarios

4.2. Analysis of Transition Resistance Impact

4.3. Analysis of Noise Impact

4.4. Analysis of the Impact of Data Synchronization Errors

4.5. Impact Analysis of Current Transformer Sampling Errors

4.6. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DTW | Dynamic Time Warping |

| FFFTS | Flexible Fractional Frequency Transmission System |

| M3C | Modular Multilevel Matrix Converter |

| FRT | Fault Ride Through |

| usd/usd | d/q-axis voltage of M3C |

| isd/isd | d/q-axis current of M3C |

| UPCC | the PCC voltage (per-unit value) |

| UC | M3C DC capacitor voltage |

| UAC | M3C low-frequency side voltage magnitude |

| superscript */ref | reference signal |

| C0, L0, and r0 | equivalent capacitance, inductance, and resistance per unit length |

| iM, iN | M-side and N-side currents |

| ick1, ick2 | the currents through the shunt capacitors on both sides of k-th segment |

| Δuk | the voltage variation across the k-th segment |

| ΔuF | the voltage change at the fault point |

| ik, ikF | current flowing into/out the k-th segment |

| DM, DG | the DTW values on the M3C side and the grid side |

| IM3C, IG | the M3C-side and grid-side curent vectors |

| γ0 | correction factor |

| K0 | operational threshold |

References

- Bi, T.; Jia, K.; Zheng, L. Pilot protection of transmission line connected to wind farm based on cosine similarity. Proc. CSEE 2019, 39, 6263–6275. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Shi, Q.; Han, R.; Yang, J. A hybrid GA–PSO–CNN model for ultra-short-term wind power forecasting. Energies 2021, 14, 6500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Z.; Meng, Y.; Ning, L.; Lin, J.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X. Overview of construction planning and key equipment technology for flexible fractional frequency transmission system. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2023, 47, 205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Zhang, C.; Song, G.; Jiang, J.; Lv, Y. Control strategy of asymmetric fault on low-frequency side of offshore wind power low-frequency transmission system. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2023, 43, 160–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, C.; Zhang, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, Q.; Lin, X.; Li, Z. A pilot protection criterion based on morphological edge-oriented operator and gradient energy matching for outgoing lines of wind farms. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2025, 45, 88–94+100. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, S.; Wang, X.; Meng, Y.; Ye, R. Techno-economic analysis of fractional frequency transmission system for integration of far-offshore wind power. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2019, 43, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Zhou, Y.; Zhou, W.; Yang, H.; Liu, Y. Low voltage ride through strategy of the D-PMSG offshore wind power farm based on energy storage and optimized reactive power. Electr. Meas. Instrum. 2024, 61, 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y.; Tao, Y.; Kong, Z.; Ning, L.; Ding, W.; Wang, S.; Wu, G.; Wang, Q. Techno-economic analysis of flexible low-frequency transmission system for offshore wind power. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 4865–4875. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wang, T. Adaptability analysis and improvement measures of current differential protection in AC grid integrated with VSC-HVDC. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2023, 51, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, D.; Wang, H.; Nei, M.; He, J. Pilot protection of submarine cables in flexible low frequency transmission systems for offshore wind power based on dynamic state estimation. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2025, 53, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, X.; Luo, H.; Bai, S. Research on mathematical model and control strategy of M3C converter based on double dq coordinate transformation. Proc. CSEE 2016, 36, 4702–4712. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Kong, X.; Wang, Y. Single-phase grounding protection for outgoing lines of DFIG-based wind farms based on waveform similarity factor. Electr. Mach. Control Appl. 2021, 48, 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W. Research on Control Method and Protection Adaptability Analysis of Low-Frequency Transmission System. Master’s Thesis, North China Electric Power University, Beijing, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W. Research on Pilot Protection and Directional Element for Power Frequency AC Line of M3C in Low-Frequency Transmission System. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Technology, Xi’an, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Wei, G.; Jin, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zahng, K.; Sun, H. Grid-connection mode and economic analysis for Rudong offshore wind farm in Jiangsu. High Volt. Eng. 2017, 43, 74–81. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Zhu, D.; Xu, X.; Wang, D.; Dai, X.; Wang, Y.; Yin, X. Study on cooperative reactive voltage sensitivity control strategy of AVC substations in clustered offshore wind farm. Electr. Meas. Instrum. 2025, 62, 53–64. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Fan, Z.; Wang, P.; Lv, M. Pilot protection algorithm for outgoing lines of large-scale wind farms based on edge detection. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2023, 43, 90–99. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Li, M.; Han, J.; Yang, F.; Shen, Y.; Kan, H. Research on fault location method for microgrid based on multi-source information fusion alarm. Electr. Meas. Instrum. 2025, 62, 45–55. [Google Scholar]

- Zha, M. Design of continuous speech control system for wheeled inspection robot based on improved dynamic time warping algorithm. Meas. Control Technol. 2025, 44, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Kang, C. Challenges and prospects of constructing new power system under the target of carbon neutrality. Proc. CSEE 2022, 42, 2806–2819. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, L.; Jia, K.; Bi, T.; Ren, L.; Yang, Z. A comprehensive criterion for pilot protection of outgoing lines from renewable energy stations based on structural similarity and squared error. Power Syst. Technol. 2020, 44, 1788–1797. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, T.; Song, W.; Lü, W. Asymmetric fault ride-through control strategy for a low frequency AC transmission system based on a modular multilevel matrix converter. Power Syst. Prot. Control 2023, 51, 107–117. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Wind Farm Capacity | 200 | MW |

| M3C Submodules (per Arm) | 100 | - |

| Submodule Rated Voltage | 3 | kV |

| Submodule Capacitance | 0.25 | mF |

| Arm Inductor | 0.5 | H |

| Low-Frequency AC Voltage | 220 | kV |

| Low-Frequency AC Frequency | 16.67 | Hz |

| Power-Frequency AC Voltage | 220 | kV |

| Power-Frequency AC Frequency | 50 | Hz |

| Transformer Ratio | 1:1 | - |

| Line Length | 50 | km |

| Series Impedance per km | 0.076 + j0.328 | Ω/km |

| Fault Location | Fault Type | Phase-A DTW Ratio | Phase-B DTW Ratio | Phase-C DTW Ratio | Protection Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fg1 (internal fault) | AG | 46.192 | 1.011 | 1.000 | Operates correctly |

| AB | 921.136 | 1628.35 | 1.032 | Operates correctly | |

| ABG | 76.918 | 150.171 | 1.385 | Operates correctly | |

| ABC | 301.565 | 1465.57 | 330.744 | Operates correctly | |

| fg2 (internal fault) | AG | 22.417 | 1.011 | 0.999 | Operates correctly |

| AB | 455.858 | 839.349 | 0.999 | Operates correctly | |

| ABG | 35.791 | 288.367 | 1.152 | Operates correctly | |

| ABC | 155.469 | 693.574 | 161.225 | Operates correctly | |

| fg3 (internal fault) | AG | 8.182 | 1.009 | 0.999 | Operates correctly |

| AB | 172.445 | 331.509 | 0.989 | Operates correctly | |

| ABG | 10.246 | 20.859 | 1.064 | Operates correctly | |

| ABC | 65.913 | 306.752 | 57.132 | Operates correctly | |

| fg4 (internal fault) | AG | 6.605 | 1.007 | 0.999 | Operates correctly |

| AB | 120.181 | 213.898 | 0.987 | Operates correctly | |

| ABG | 56.09 | 15.348 | 1.0864 | Operates correctly | |

| ABC | 58.092 | 258.865 | 49.411 | Operates correctly | |

| fg5 (internal fault) | AG | 4.631 | 1.007 | 0.999 | Operates correctly |

| AB | 75.689 | 134.235 | 0.987 | Operates correctly | |

| ABG | 4.787 | 8.659 | 1.031 | Operates correctly | |

| ABC | 56.008 | 225.973 | 56.880 | Operates correctly | |

| fg6 (external fault) | AG | 1.017 | 1.003 | 1.004 | Restrains correctly |

| AB | 1.027 | 1.021 | 1.002 | Restrains correctly | |

| ABG | 1.007 | 1.064 | 0.998 | Restrains correctly | |

| ABC | 1.081 | 1.317 | 0.999 | Restrains correctly | |

| fg7 (external fault) | AG | 1.126 | 0.894 | 0.872 | Restrains correctly |

| AB | 1.004 | 1.007 | 1.019 | Restrains correctly | |

| ABG | 1.002 | 0.924 | 0.997 | Restrains correctly | |

| ABC | 1.097 | 1.107 | 0.992 | Restrains correctly |

| Fault Type | Transition Resistance | Phase-A DTW Ratio | Phase-B DTW Ratio | Phase-C DTW Ratio | Protection Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG | 20 Ω | 25.569 | 1.023 | 0.988 | Operates correctly |

| 50 Ω | 29.662 | 1.067 | 0.981 | Operates correctly | |

| 100 Ω | 33.024 | 1.029 | 0.969 | Operates correctly | |

| 20 Ω | 145.112 | 78.319 | 1.767 | Operates correctly | |

| ABG | 50 Ω | 108.732 | 69.050 | 1.950 | Operates correctly |

| 100 Ω | 80.984 | 60.524 | 1.086 | Operates correctly | |

| 20 Ω | 25.569 | 1.023 | 0.988 | Operates correctly | |

| 50 Ω | 29.662 | 1.067 | 0.981 | Operates correctly |

| Fault Location | Fault Type | Phase-A DTW Ratio | Phase-B DTW Ratio | Phase-C DTW Ratio | Protection Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fg2 | AG | 20.343 | 1.145 | 1.001 | Operates correctly |

| AB | 233.540 | 250.549 | 0.953 | Operates correctly | |

| ABG | 38.467 | 185.242 | 1.039 | Operates correctly | |

| ABC | 38.467 | 341.931 | 93.851 | Operates correctly | |

| fg7 | AG | 1.213 | 0.905 | 0.894 | Restrains correctly |

| AB | 1.071 | 1.082 | 1.012 | Restrains correctly | |

| ABG | 1.103 | 1.012 | 1.027 | Restrains correctly | |

| ABC | 1.124 | 1.176 | 1.153 | Restrains correctly |

| Fault Type | Phase-A DTW Ratio | Phase-B DTW Ratio | Phase-C DTW Ratio | Protection Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG | 1.017 | 1.003 | 1.004 | Restrains correctly |

| AB | 1.027 | 1.021 | 1.002 | Restrains correctly |

| ABG | 1.007 | 1.064 | 0.998 | Restrains correctly |

| ABC | 1.081 | 1.317 | 0.999 | Restrains correctly |

| Fault Type | Fault Location | Error Magnitude | Phase-A DTW Ratio | Phase-B DTW Ratio | Phase-C DTW Ratio | Protection Action |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AG | fg2 | +10% | 20.176 | 0.910 | 0.900 | Operates correctly |

| +15% | 19.056 | 0.732 | 0.850 | Operates correctly | ||

| fg6 | −10% | 1.132 | 0.901 | 0.882 | Restrains correctly | |

| −15% | 1.217 | 0.703 | 0.814 | Restrains correctly | ||

| ABC | fg2 | +10% | 139.924 | 624.221 | 145.104 | Operates correctly |

| +15% | 132.151 | 589.544 | 137.044 | Operates correctly | ||

| fg6 | −10% | 1.182 | 1.233 | 1.109 | Restrains correctly | |

| −15% | 1.264 | 1.218 | 1.301 | Restrains correctly |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jin, W.; Zhang, S.; Liang, R.; Zhao, J. Dynamic Time Warping-Based Differential Protection Scheme for Transmission Lines in Flexible Fractional Frequency Transmission Systems. Electronics 2026, 15, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010045

Jin W, Zhang S, Liang R, Zhao J. Dynamic Time Warping-Based Differential Protection Scheme for Transmission Lines in Flexible Fractional Frequency Transmission Systems. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010045

Chicago/Turabian StyleJin, Wei, Shuo Zhang, Rui Liang, and Jifeng Zhao. 2026. "Dynamic Time Warping-Based Differential Protection Scheme for Transmission Lines in Flexible Fractional Frequency Transmission Systems" Electronics 15, no. 1: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010045

APA StyleJin, W., Zhang, S., Liang, R., & Zhao, J. (2026). Dynamic Time Warping-Based Differential Protection Scheme for Transmission Lines in Flexible Fractional Frequency Transmission Systems. Electronics, 15(1), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010045