Efficient Weather Perception via a Lightweight Network with Multi-Scale Feature Learning, Channel Attention, and Soft Voting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Preliminary

2.1. Convolutional Neural Network and Standard Designs

- EfficientNet-b0 is the foundational model in the EfficientNet series. Instead of scaling depth, width, or resolution independently as in conventional CNNs, it applies a compound scaling strategy to adjust all dimensions in a balanced way. This concept makes EfficientNet-b0 well-suited for practical deployments where both computational efficiency and accuracy are essential, providing a significant trade-off among speed, model size, and predictive performance [15].

- ResNet-50 is a 50-layer deep convolutional neural network from the Residual Network series. Its key innovation lies in shortcut (skip) connections that form residual learning to effectively address the vanishing gradient issue in very deep networks. By allowing layers to learn residual mappings, ResNet-50 can train deeper architectures more reliably and efficiently [16].

- SqueezeNet is a lightweight CNN architecture that achieves high accuracy while drastically reducing the number of model parameters. Its structure minimizes memory usage and computational demands, which makes it suitable for resource-constrained environments, e.g., Internet of Things (IoT) applications, embedded devices, and so on [17].

- MobileNetV3 is also a lightweight CNN architecture for mobile and edge devices. It builds upon the inverted residual blocks of MobileNetV2, Neural Architecture Search (NAS) techniques from EfficientNet, Squeeze-and-Excitation (SE) modules, and the efficient h-swish activation function [18]. MobileNetV3 has two main variants: MobileNetV3-Large and MobileNetV3-Small. The Large version is designed for tasks requiring higher accuracy. It uses deeper and wider layers with SE modules to enhance channel attention. In contrast, the Small version is optimized for real-time and ultra-low power applications. With a lighter architecture, it runs significantly faster with lower latency. Thus, MobileNetV3 provides flexible options depending on the deployment scenario.

- LSKNet addresses the challenge of detecting small and diverse objects in remote sensing images [19]. The key idea is to use large and adaptive convolutional kernels that dynamically adjust the receptive field according to different regions and object types, effectively capturing both fine details and global contextual information. This work highlights the potential of dynamically designed receptive fields for the unique characteristics of remote sensing imagery, offering a new perspective for future model architectures in aerial object detection.

2.2. Critical Components in Our Model

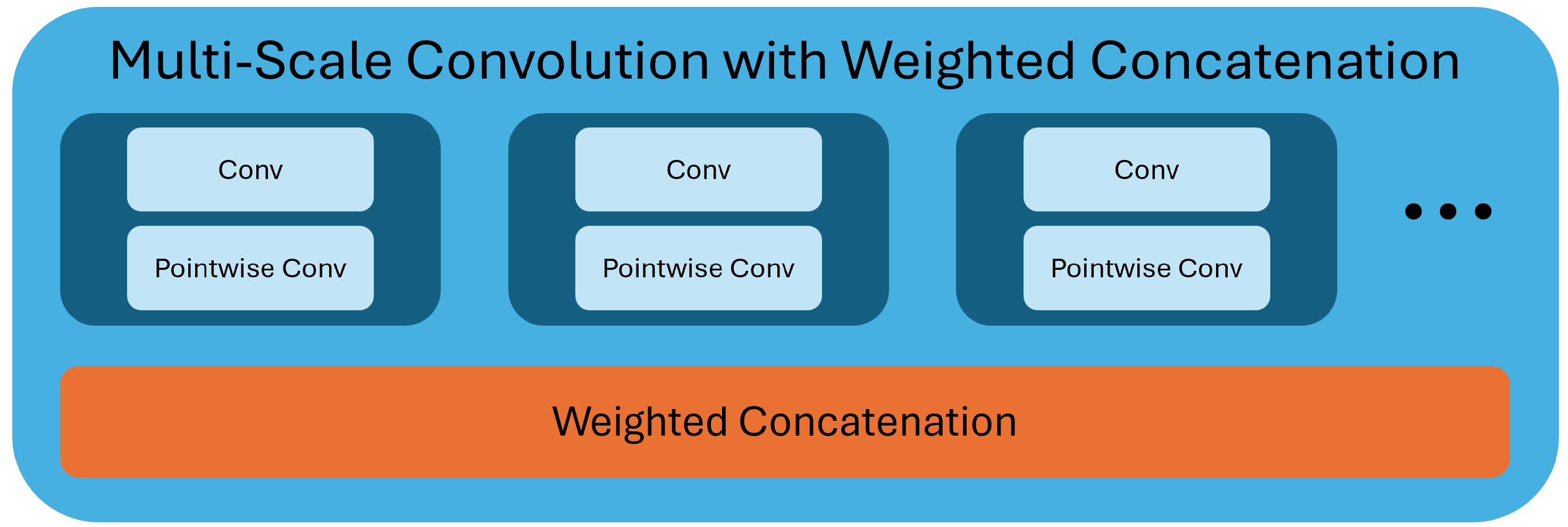

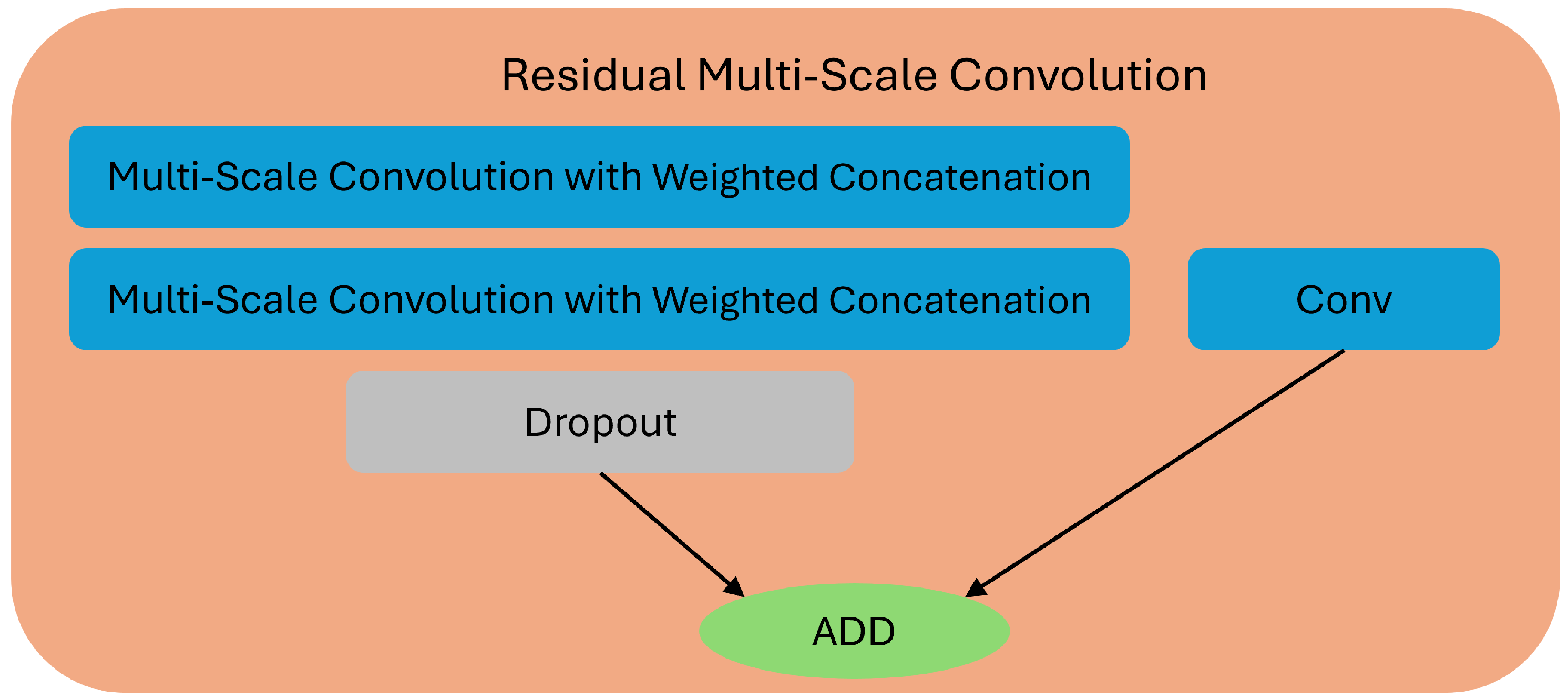

- Multi-scale feature learning integrates features extracted at different scales via dense blocks with various sizes. It aggregates low-level and high-level information through dense and skip connections, while a bottleneck layer compresses the concatenated feature maps to reduce redundancy. This design allows the network to simultaneously capture fine details and broader contextual features to achieve balance [20].

- The channel attention mechanism used here is Squeeze-and-Excitation, which aims to enhance the representational power of CNNs by adaptively recalibrating channel-wise feature responses. Instead of treating all feature channels equally, SE blocks explicitly model inter-channel dependencies. This is achieved through two operations: a squeeze step aggregating global spatial information into compact channel descriptors via global average pooling and an excitation step employing a lightweight gating mechanism to capture channel relationships and generate adaptive weights. These weights are then used to rescale the feature maps, strengthen informative channels, and suppress less useful ones [15].

- Soft voting is an ensemble strategy in which each classifier contributes a probability distribution over all classes. Instead of simply voting for one class, every model provides its estimated probability for each possible category. These probability values are then aggregated, although weighted combinations can also be used when specific models are considered more reliable. After aggregation, the class with the highest combined probability is selected as the final prediction. On the other hand, compared with hard voting, which only counts the discrete class decisions of each classifier, soft voting preserves information about each model’s confidence level. This makes the ensemble more stable and typically more accurate. Soft voting can be applied not only across multiple independent classifiers but also within a single CNN architecture. When a CNN contains multiple branches, each branch can be treated as an individual learner that produces its own class-probability output, e.g., multi-scale feature extraction, multi-path feature extraction, and so on. By aggregating these branch-level probability distributions through soft voting, the model effectively integrates complementary information captured by different branches, leading to improved robustness and overall classification performance [21,22].

3. Our Method

3.1. Architecture of Our Proposed Convolutional Neural Network

3.2. Training and Testing Phases

| Algorithm 1: Training and testing phases for weather perception |

1 Input phase: 2 data: an integration of the MCWRD2018 and DAWN2020 datasets; 3 Variable phase: 4 augmenting: a dataset; 5 training: a dataset; 6 testing: a dataset; 7 model: our deep learning model; 8 benchmarks: all comparisons (EfficientNet-B0, ResNet50, SqueezeNet, MobileNetV3-Large, MobileNetV3-Small, and LSKNet); 9 Initial phase: 10 augmenting ← augment(data); 11 training ← split(augmenting, 80%); 12 testing ← split(augmenting, 20%); 13 Training phase: 14 train model using training; 15 train benchmarks using training; 16 Evaluating phase: 17 evaluate model using testing; 18 evaluate benchmarks using testing; |

4. Experimental Results

- Datasets: MCWRD2018 and DAWN2020 were employed as the original datasets (images illustrating the seven distinct weather categories are shown in Figure 5).

- The real-world dataset consists of dashcam video recordings from roads in Taiwan under four different weather conditions. From each video sequence, 50 frames were uniformly sampled to construct the final image set.

- Training and testing split: The original (unaugmented) dataset was first randomly divided into mutually exclusive training (80%) and testing (20%) subsets. This ensured that no image or its variants appeared in both subsets.

- Data augmentation: After splitting the original dataset into mutually exclusive training and testing subsets, augmentation was applied only within each subset to avoid data leakage. Each image was further augmented by horizontal flipping and by cropping from each of the four sides.

- Input resolution: .

- Output resolution: .

- Epochs: 300.

- Batch size: 16.

- Learning rate: 0.0001.

- Loss function: CrossEntropyLoss.

- Optimizer: Adam.

- Benckmarks: EfficientNet-B0, ResNet50, SqueezeNet, MobileNetV3-Large, MobileNetV3-Small, and LSKNet.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Haija, Q.A.; Gharaibeh, M.; Odeh, A. Detection in Adverse Weather Conditions for Autonomous Vehicles via Deep Learning. AI 2022, 3, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Multi-Class Weather Dataset for Image Classification—Mendeley Data. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/4drtyfjtfy/1 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- DAWN—Mendeley Data. Available online: https://data.mendeley.com/datasets/766ygrbt8y/3 (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Hwang, K. Cloud Computing for Machine Learning and Cognitive Applications; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hwang, K.; Chen, M. Big-Data Analytics for Cloud, IoT and Cognitive Computing; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ooi, Y.-M.; Chang, C.-C.; Su, Y.-M.; Chang, C.-M. Vision-Based UAV Localization on Various Viewpoints. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 38317–38324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, T.; Wang, W.; Quan, R.; Yang, Y. Shape2Scene: 3D Scene Representation Learning Through Pre-training on Shape Data. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2024: 18th European Conference, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chae, Y.; Kim, H.; Oh, C.; Kim, M.; Yoon, K.-J. LiDAR-Based All-Weather 3D Object Detection via Prompting and Distilling 4D Radar. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2024: 18th European Conference, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.; Shu, T.; Zhao, H.; Tang, Y.Y. MASK-CNN-Transformer for Real-Time Multi-Label Weather Recognition. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 278, 110881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Kotlyar, O.; Andreasson, H.; Lilienthal, A.J. Robust Object Detection in Challenging Weather Conditions. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, C.-Y.; Chen, Y.-C.; Chen, T.-T.; Lai, T.-H.; Chou, T.-Y.; Ning, F.-S.; Chen, M.-H. Synthetic Data-Driven Real-Time Detection Transformer Object Detection in Raining Weather Conditions. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 4910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbass, M.J.; Lis, R.; Awais, M.; Nguyen, T.X. Convolutional Long Short-Term Memory (ConvLSTM)-Based Prediction of Voltage Stability in a Microgrid. Energies 2025, 17, 1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosna, A.; Merry, E.; Gyalmo, J.; Alom, Z.; Aung, Z.; Azim, M. Transfer Learning: A Friendly Introduction. J. Big Data 2022, 9, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, F.; Qi, Z.; Duan, K.; Xi, D.; Zhu, Y.; Zhu, H.; Xiong, H.; He, Q. A Comprehensive Survey on Transfer Learning. Proc. IEEE 2021, 109, 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Le, Q.V. EfficientNet: Rethinking Model Scaling for Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 36th International Conference on Machine Learning, Long Beach, CA, USA, 9–15 June 2019. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, Nevada, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Iandola, F.N.; Han, S.; Moskewicz, M.W.; Ashraf, K.; Dally, W.J.; Keutzer, K. SqueezeNet: AlexNet-level accuracy with 50x fewer parameters and <0.5MB model size. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1602.07360. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chen, B.; Wang, W.; Chen, L.-C.; Tan, M. Searching for MobileNetV3. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Hou, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Cheng, M.-M.; Yang, J.; Li, X. Large Selective Kernel Network for Remote Sensing Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 2–3 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.; Jun, D.; Kim, B.-G.; Lee, H. Enhanced Single Image Super Resolution Method Using Lightweight Multi-Scale Channel Dense Network. Sensors 2021, 21, 3351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rokach, L. Ensemble-based classifiers. Artif. Intell. Rev. 2010, 33, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.-H. Ensemble Methods: Foundations and Algorithms; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, P.F.; Tian, Z.; Dong, M.; Cheng, S.; Sun, L.; Li, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G. Efficient Neural Network Using Pointwise Convolution Kernels with Linear Phase Constraint. Neurocomputing 2021, 423, 572–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welcome to Python.org. Available online: https://www.python.org/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- PyTorch. Available online: https://pytorch.org/ (accessed on 7 December 2025).

| Model Name | Best Epoch | Accuracy(%) | Model Size (MB) | Parameters (M) | GFLOPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Our model | 276 | 98.07 | 1.6 | 0.4 | 0.19 |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 262 | 98.37 | 15.62 | 4.02 | 0.82 |

| ResNet50 | 267 | 96.52 | 90.04 | 23.52 | 8.26 |

| SqueezeNet | 235 | 96.98 | 4.81 | 1.26 | 1.67 |

| MobileNet V3-Large | 299 | 98.07 | 16.27 | 4.21 | 0.46 |

| MobileNet V3-Small | 198 | 97.45 | 5.95 | 1.53 | 0.12 |

| LSKNet | 246 | 97.83 | 65.87 | 17.16 | 7.06 |

| Performance Metric | Confidence (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Name | Cloudy | Fog | Rain | Sand | Shine | Snow | Sunrise |

| Our model | 99.82% | 91.79% | 96.39% | 97.92% | 98.97% | 98.33% | 99.82% |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 99.61% | 93.34% | 97.03% | 98.49% | 99.73% | 99.67% | 100.00% |

| ResNet50 | 97.45% | 88.54% | 93.87% | 95.15% | 97.68% | 99.35% | 99.99% |

| SqueezeNet | 99.73% | 89.21% | 93.87% | 95.06% | 95.25% | 97.85% | 99.84% |

| MobileNet V3-Large | 97.68% | 92.01% | 96.93% | 98.53% | 99.94% | 99.15% | 99.96% |

| MobileNet V3-Small | 97.51% | 89.28% | 95.57% | 98.41% | 98.79% | 97.70% | 99.58% |

| LSKNet | 100% | 98.21% | 94.96% | 96.97% | 98.71% | 99.16% | 98.62% |

| Performance Metric | Confidence (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model Name | Cloudy | Rain | Shine | Sunrise |

| Our model | 99.98% | 98.01% | 98.05% | 99.81% |

| EfficientNet-B0 | 73.61% | 98.96% | 76.11% | 90.48% |

| ResNet50 | 89.44% | 98.78% | 94.22% | 88.73% |

| SqueezeNet | 96.87% | 98.87% | 72.78% | 76.73% |

| MobileNet V3-Large | 85.43% | 99.21% | 83.87% | 86.69% |

| MobileNet V3-Small | 78.49% | 81.97% | 90.73% | 72.12% |

| LSKNet | 93.55% | 96.85% | 79.33% | 93.71% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Chang, C.-C.; Wu, P.-T.; Tsai, T.-Y.; Lin, J.-W. Efficient Weather Perception via a Lightweight Network with Multi-Scale Feature Learning, Channel Attention, and Soft Voting. Electronics 2026, 15, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010004

Chang C-C, Wu P-T, Tsai T-Y, Lin J-W. Efficient Weather Perception via a Lightweight Network with Multi-Scale Feature Learning, Channel Attention, and Soft Voting. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Che-Cheng, Po-Ting Wu, Ting-Yu Tsai, and Jhe-Wei Lin. 2026. "Efficient Weather Perception via a Lightweight Network with Multi-Scale Feature Learning, Channel Attention, and Soft Voting" Electronics 15, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010004

APA StyleChang, C.-C., Wu, P.-T., Tsai, T.-Y., & Lin, J.-W. (2026). Efficient Weather Perception via a Lightweight Network with Multi-Scale Feature Learning, Channel Attention, and Soft Voting. Electronics, 15(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010004