1. Introduction

With the development of renewable energy gradually extending into weak-grid regions, China has widely adopted grid-commutated high-voltage DC transmission for long-distance, large-scale power delivery, thereby forming the world’s largest and highest-voltage AC-DC hybrid network [

1]. However, power from renewable energy plants often needs to be collected via long AC lines to DC converter stations, resulting in low short-circuit ratio (SCR) characteristics at the grid connection points. In this context, any disturbance in the AC-DC system, especially DC-end commutation failures, can induce severe voltage fluctuations at the plant bus [

2,

3,

4] before protection activation, and consecutive commutation failures may even occur, exposing converters to significant transient instability risks during rapid voltage transitions. In 2019, during a single commutation failure of the Tianzhong DC line, the sending-end AC grid experienced a transient overvoltage of approximately 1.2 p.u. Conventional thermal units continued to operate normally, whereas renewable generation units such as wind turbines were at risk of large-scale disconnection. In 2023, with a high penetration of renewables in the Northwest power grid—particularly in regions with dense multi-DC sending-end connections such as Lingshao and Yindong—a single AC fault could cause a simultaneous and rapid short-term drop of multiple nearby DC power flows, resulting in system frequency exceeding 50.5 Hz and posing a significant risk of widespread renewable generation disconnection [

5].

Currently, sending-end renewable plants typically adopt grid-following control (GFC), using a phase-locked loop (PLL) to synchronize with the AC grid [

6]. Under low-SCR conditions near the DC side, rapid voltage variations reduce PLL locking capability, potentially causing generator tripping [

7]. To address this, existing studies have extended PLL stability analysis from small-signal to large-disturbance conditions [

8], noting that PLL stability is mathematically similar to synchronous machine dynamics [

9], and introducing methods such as the equal-area criterion [

10] and energy function analysis [

11]. And due to the fast dynamic response of the PLL, its dynamic coupling with line dynamics can introduce a negative-damping effect [

12]. To address the conservative nature of existing analysis methods, an energy-based stability boundary analysis is proposed using a Lyapunov function [

13]. However, these works primarily focus on the mechanisms of transient instability and often neglect the dynamic response of transient currents. In fact, the grid voltage at the connection point and the ride-through coefficient K jointly determine the reactive current, and assuming a fixed current introduces non-negligible errors. To tackle this, some studies propose transient adaptive ride-through coefficient control [

14] or variable ride-through coefficient strategies under consecutive faults [

15], and even some studies the influence of the converter transient power angle and ride-through coefficient under different short-circuit ratios, and transient stability is optimized based on trajectory sensitivity analysis [

16]. But these approaches rely on real-time communication and grid parameter exchange, making practical implementation challenging. In summary, prior research mainly focuses on dynamic adjustment of the ride-through coefficient, whereas implementing a fixed ride-through coefficient is already costly in engineering practice, and adding coordinated communication further increases complexity. Therefore, optimizing control under a fixed ride-through coefficient is more practical. Moreover, most studies concentrate on AC short-circuit scenarios, while systematic analysis of AC-DC hybrid faults—particularly common DC near-end events such as commutation failures and protection-induced blocking—is still lacking. These faults often involve severe transient voltage disturbances, which can easily destabilize converters and require further investigation.

To this end, this paper focuses on the following core problem: how to ensure transient synchronization stability of inverter-based renewable energy converters at DC sending ends under near-end DC faults, where rapid and large voltage excursions occur and conventional fixed-coefficient ride-through schemes fail to maintain stable operation in weak-grid conditions. Addressing this problem is essential for enhancing the resilience of renewable-dominated networks during the ongoing energy transition.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows: In

Section 2, a comprehensive analytical framework is developed to reveal the transient synchronization instability mechanism of renewable converters under DC near-end faults, explicitly accounting for the coupled effects of grid strength and fault-induced voltage dynamics. In

Section 3, the stability regions of converter operation are analytically characterized, providing clear quantitative criteria for assessing synchronization margins under different fault severities and short-circuit ratios. Then in

Section 4, a local virtual power-angle incremental feedback control strategy is proposed, which effectively suppresses transient instability without relying on communication or adaptive parameter tuning, making it suitable for practical implementation. Finally in

Section 5, The effectiveness and engineering feasibility of the proposed strategy are validated through Simulink and real-time RT-LAB hardware-in-the-loop experiments.

3. Transient Stability Analysis of Renewable Energy Grid-Connected Systems

3.1. Dynamic Analysis of Transient Parameters in the Converter Transient Model

Based on the model in Equation (6), the transient characteristic curve of the GFC can be obtained, and the stability-influencing factors of the GFC transient model can be analyzed accordingly.

As illustrated in

Figure 4, considering the most common voltage sag scenarios (e.g., short-circuit faults, commutation failures, etc.), when the external grid voltage sags,

changes from the orange curve to the green curve. At this point, under the action of the accelerating voltage, the system starts to accelerate from the equilibrium point a; if a voltage reverse regulation occurs when passing

, it transitions from the green curve to the blue curve. The converter gradually decelerates under the action of the decelerating voltage, and the point corresponding to the maximum decelerating area after voltage recovery is point

. Based on the aforementioned analysis, it can be concluded that the transient stability of the system mainly depends on the input voltage

.

Based on the aforementioned analysis, to ensure that

can always stabilize at the new equilibrium point, quantitative judgment using Equation (6) is required. Given that the PLL damping is typically 3 to 4 orders of magnitude smaller than

, the damping term can be neglected. Subsequently, multiplying both sides of the equation by the differential of the power angle and integrating, the following result is obtained:

Regarding the variation in the PLL parameters analyzed in

Figure 4, if the converter’s power angle can establish a new equilibrium point, the stability boundary under this condition can be derived from Equation (8) as follows:

However, according to Reference [

19], the stability boundary obtained solely through the equal-area criterion is relatively aggressive. Therefore, on the basis of clarifying the relationship between system parameters and the stability boundary, it is necessary to further optimize the boundary determined by Equation (9) by incorporating the dynamic processes of voltage and current under the converter’s transient state. The GFC behaves as a controlled current source, whose output current is determined by the current reference, and the phase is dominated by the PLL. Thus, the converter’s grid connection point voltage

is jointly determined by the current reference and the PLL.

However, there is a significant difference in response speed between the current loop and the PLL: the PLL bandwidth is typically only several tens of hertz, while the current loop bandwidth is close to the switching frequency with a much faster response. Based on the singular perturbation principle [

20], the GFC system can be decoupled into a slow-response PLL subsystem and a fast-response current loop subsystem. It is generally considered that the dynamics of the current loop in the fast subsystem can be neglected, and the converter’s output current is regarded as instantaneously following the reference value. Therefore, the input voltage

can be further expressed as follows:

It can be observed from Equation (10) that the main factors affecting

are the impedance characteristics of the converter’s external circuit and the dq-axis current reference values during the transient process. However, the renewable energy sending-end system is mainly connected to the grid via high-voltage alternating current transmission lines, whose impedance characteristics are characterized by a SCR and a low reactance-to-resistance ratio (X/R > 10). Therefore, the dominant term of

is

. Additionally, due to the constraints of the converter’s device characteristics, there exists a limitation on the converter’s overload capacity:

Based on the comprehensive analysis above, the influencing factors of

can be integrated into the following relationship:

As can be observed from Equation (1), due to the discontinuity of the control strategy, the piecewise characteristic of the converter’s overload limiting, and the variation in the initial value of the d-axis active current caused by different generator output levels, the reactive current reference —formed by the converter after entering LVRT control based on the grid voltage sag severity—varies dynamically in real time with the grid voltage. Therefore, it is necessary to classify and analyze the final output current in conjunction with the active power output level. During the fault ride-through process, on the premise of prioritizing reactive power, efforts should be made to meet the active power demand. Meanwhile, the converter should operate with its dq-axis currents as close to full load as possible within its overload capacity to ensure the balance and stability of the system.

3.2. Influence of Ride-Through Coefficient on Transient Stability

As mentioned earlier, during the transient process, the converter’s dq-axis currents

and

not only change dynamically with transient voltage fluctuations but also undergo further adjustments due to the deviation of the virtual power angle. Given that analyzing the transient quantitative relationship between the virtual power angle and the dq-axis currents is extremely complex [

21], it is necessary to optimize the existing methods to accurately evaluate the impact of transient voltage dynamics on current control. Based on Equations (9)–(12), the functional relationship between the converter’s transient parameters and the network parameters can be rearranged as follows:

The functional relationship established by Equation (13) characterizes the correlation between the converter’s grid connection point voltage, external grid voltage, and the converter’s q-axis current during the transient process. Obviously, the main parameter affecting the relationship among these three quantities is the system impedance. By combining Equation (11) in the coordinate system with as the horizontal axis and as the vertical axis, the relationship diagram between the dq-axis currents and the grid connection point voltage, as shown in the following figure, is plotted.

Figure 5a shows the current–voltage operating curves of the converter under a certain system impedance value. The purple surface represents the converter’s overload limit described by Equation (11), while the green curves illustrate the converter response under varying external grid voltages. The green curves can be observed to converge around

; from the inner to the outer curves, they correspond to increasing voltage sag severity, representing the transient operating trajectories of the converter response current under grid voltages of 0.1, 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, 1.2, and 1.3 p.u., respectively.

As the external grid voltage continues to sag, the converter’s operating range gradually converges to a fixed point. Under overvoltage conditions, however, the system operating curves tend to stabilize. In addition, the red curve represents the reactive current increment trajectory corresponding to the boundary ride-through coefficient specified in the “standards”. Based on the aforementioned relationships, the operating characteristics of the sending-end system with SCR of 1.5, 2, and 2.5, respectively, and an impedance ratio (X/R = 10), are further plotted, as shown in

Figure 5b–d.

By comparing

Figure 5b with

Figure 5c,d, it can be observed that as the system SCR decreases, the voltage sag value corresponding to the intersection of the current operating curve and the converter operating curve increases accordingly. In other words, when the SCR is relatively low as

Figure 5b, even a shallow voltage sag may result in the absence of an intersection between the two curves, and

is always higher than

under such circumstances, leading to an excessive accelerating area and ultimately causing instability.

Since the operating curves under LVRT are mainly classified into two types: “zero-crossing” and “non-zero-crossing”, and instability is primarily associated with the “non-zero-crossing” operating curves, the ride-through coefficient is excessively small at this point, resulting in no intersection between the increment curve and the “non-zero-crossing” operating curves. Thus, by combining Equations (1) and (13), the upper and lower slope limits

and

can be derived when the increment curve is tangent to the operating curves corresponding to different voltage sags:

As can be inferred from Equation (14), the tangent slope (i.e., the boundary of the ride-through coefficient) varies with the transient grid voltage, and its magnitude mainly depends on the system equivalent impedance.

From this, the quantitative relationship between the LVRT coefficient and the SCR under different SCR values can be further derived, as shown in

Figure 6.

It can be observed that the SCR mainly determines the voltage level of the convergence center: as the SCR increases, the voltage at the convergence center decreases. The central current is mainly affected by the reactance-to-resistance ratio; for detailed analysis on the reactance-to-resistance ratio, refer to Reference [

22]. Herein, the focus is on the impedance characteristics of the sending-end power grid, and the influence of system resistance is neglected. Thus, the central current can be fixed at

. Furthermore, when

, the line connecting the convergence center, the LVRT critical point (0.9 p.u. voltage), and the zero-current point can be expressed as follows:

4. Control Strategy Based on Virtual Power Angle Increment Feedback

4.1. Stability Analysis and Setting of the Ride-Through Coefficient

The above analysis has elaborated on the instability mechanism and the role of control parameters during the transient process of renewable energy converters in the DC near-area. In current engineering practice, the ride-through coefficient of converters is typically set once via on-site tests before grid connection, and it is difficult to adjust in real time after grid connection. Therefore, a fixed ride-through coefficient must be adopted for fault ride-through.

The ride-through coefficient setting method proposed in this paper is as follows: when the external fault voltage propagates to the converter’s grid connection point and triggers LVRT, the pre-determined ride-through coefficient is directly applied for process control. Under high SCR conditions, the system stability region is relatively wide, and the initial ride-through coefficient can be determined based on the most severe fault condition to ensure stability under all fault scenarios. A schematic diagram of the stability region is shown in the following figure.

The ride-through coefficient

of the converter within the stability region can be defined by the following equation:

Therefore, according to SCR measured before the power plant is connected to the grid, if falls within the range of 1.5 to 3 specified in the “standards”, this ride-through coefficient can be directly adopted to cope with all transient conditions.

However, if

is outside the range specified in the “standards”, it can be observed from

Figure 7 that the unstable region on the left side of the curve expands significantly. Under low SCR conditions, it is difficult to find an effective ride-through coefficient. To ensure successful ride-through, a relatively large coefficient has to be adopted. Nevertheless, due to the rapid current response, the significant increase in converter current leads to a short-term surge in reactive power. After the grid connection point voltage recovers, the converter quickly exits LVRT control. However, the fault has not been cleared, resulting in a subsequent voltage sag and repeated switching of the ride-through control. It can thus be concluded that there is an urgent need to optimize the fault ride-through control method under low SCR scenarios.

4.2. Transient Control Strategy Based on Virtual Power Angle Increment Feedback

As analyzed in

Section 2, the key to maintaining converter stability lies in the dominant term

of

. Therefore, on the premise of satisfying the given reactive power reference

, the virtual power angle increment is determined by the PLL output frequency increment during transient instability. Furthermore, the

in the dominant term of

can be dynamically corrected by introducing a feedback mechanism of this increment. Reducing

can effectively decrease

, thereby equivalently reducing the accelerating area and suppressing the further increase in the power angle. To this end, an additional transient control strategy as shown in the following figure is proposed in this paper.

As shown in

Figure 8, after triggering the fault ride-through control, the system first calculates a virtual increment based on the converter frequency difference. An upper limit of 0 is set for this increment to ensure that the suppression of the power angle does not cause a negative frequency growth due to overshoot, thereby avoiding the risk of underfrequency caused by reverse integration. Subsequently, the obtained virtual power angle increment is input to the current loop; when the fault is cleared and the bus voltage recovers, a recovery signal is provided to eliminate integral residual, ensuring that the steady-state active power output is not affected. This strategy can effectively suppress the acceleration of frequency and power angle under low SCR conditions at the cost of sacrificing only a small portion of active power, thereby improving system stability.

To implement the aforementioned additional control strategy, it is necessary to further clarify the influence of control parameters on system response, especially the control capability of the additional integral link on the power angle and frequency regulation processes, as well as its impact on transient voltage. Therefore, it is essential to conduct reasonable design and robustness analysis for these parameters. For the integral parameter

, its design principle should satisfy Equation (13), so that the system can achieve stability under the most severe fault conditions. According to the control method shown in

Figure 8, the d-axis control process can be expressed as follows:

As can be inferred from Equation (1), Equation (17) can be rearranged as follows:

To satisfy Equation (13), the influence of resistance is neglected, and the equation is further rearranged as follows:

By differentiating Equation (19), it can be observed that

is a decreasing function of

, and

has a unique solution within the interval

. Furthermore, based on Equation (10), the following definition can be made:

Since

is a decreasing function of

, and as previously analyzed,

is the dominant term,

is therefore also a decreasing function of

. Given that the prerequisite condition (Equation (13)) is satisfied, there must be an intersection between

and

. Assuming the converter outputs reactive power during the transient process

, it is sufficient that

has a solution within the interval

. It can be assumed that there exists a

such that

. Let the impedance angle be

; then at

, Equation (20) can be rewritten as:

By combining Equations (19) and (21), the following result is obtained:

Thus, rearranging the above equations yields:

To enhance the applicability of the designed parameters, the range of is specified as 1.5 to 3 in the “standards”. For , to avoid excessive overvoltage surges caused by an overly aggressive recovery process and the impact of current limiting, its value should not exceed 4. Thus, the integral parameter should be set within the range of 1.01 to 1.41.

As inferred from the above derivation, the response speed of the proposed control strategy has a positive correlation with both the PLL bandwidth and the integral coefficient . Specifically, a larger results in a faster response of the integral link but also introduces a greater overshoot. This necessitates appropriate amplitude limiting for the output . Considering that conventional GFC only allow a positive , an excessive overshoot will cause the converter to temporarily cease active power output. Meanwhile, by setting an upper limit for the power angle increment , positive feedback induced by excessively decelerating voltage can be prevented, avoiding further frequency drop and subsequent loss of synchronization. Integrating the aforementioned mechanisms, the robustness of the control strategy can be further improved while ensuring active power output.

5. Analysis of Simulation Results

To validate the transient synchronization stability and voltage impact mitigation capability of the proposed virtual power-angle increment feedback control strategy in a high-renewable-penetrated sending-end network, a single commutation failure scenario was first investigated through detailed Simulink simulations and subsequently validated on the RT-LAB hardware-in-the-loop (HIL) platform, as introduced in the preceding subsection.

The commutation failure induces a near-zone AC voltage disturbance characterized by an initial voltage rise followed by a deep sag, posing a severe challenge to the converter synchronizing margin and transient voltage stress. Oscilloscope measurements were employed to capture the PCC voltage,

, and system frequency. A physical overview of the HIL hardware configuration and experimental test bench is presented in

Figure 9.

Details of the converter control, AC network parameters, and DC station settings are provided in

Table 1.

Scenario 1 (SCR = 1.5):

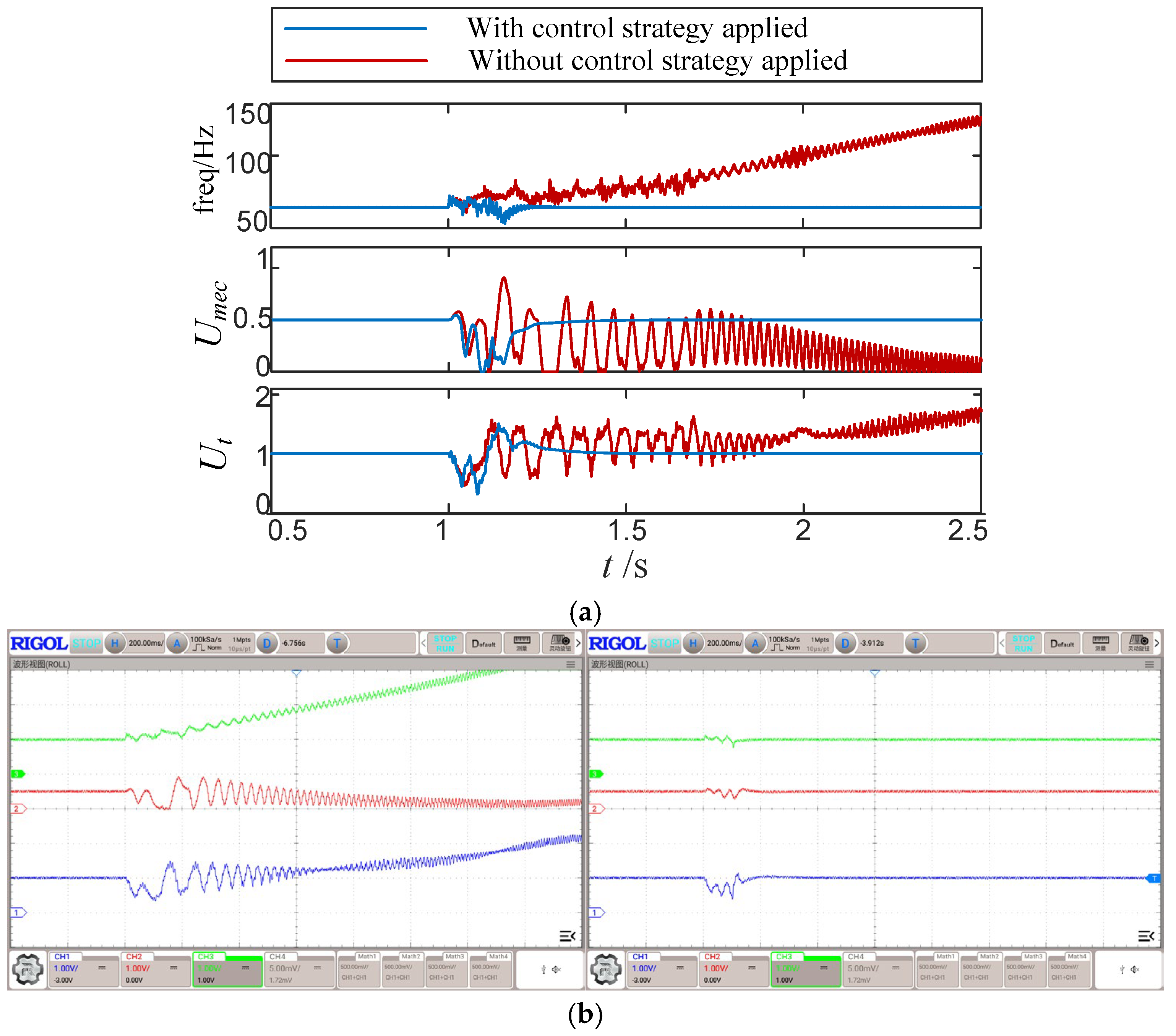

As shown in

Figure 10a, the converter operating without auxiliary control exhibits at SCR = 1.5 sustained

growth throughout the voltage sag interval, indicating rapid loss of synchronization margin. Following voltage recovery, frequency divergence and increasing phase deviation are observed, and the system ultimately enters transient synchronization instability. After enabling the proposed control, the early rise of

is promptly suppressed. Frequency trajectories remain convergent and phase deviation is bounded during the voltage rebound, enabling the converter to preserve synchronous operation. The results shown in

Figure 10b validate the effectiveness of the offline simulations.

Scenario 2 (SCR = 2):

As shown in

Figure 11a, when grid strength improves to SCR = 2.0, the converter without control still shows a potential-angle-drift-driven increase in

, which excites a growing oscillatory trend in frequency, yet the divergence process presents a more moderate transient behavior than the weakest grid case. After incorporating the control,

growth is significantly moderated and frequency fluctuations are visibly reduced, yielding a smoother post-fault recovery profile. This confirms that the method can still strengthen converter synchronizing stability in a moderate-weak grid, via a transient response pattern distinct from the weakest grid. The results shown in

Figure 11b validate the effectiveness of the offline simulations.

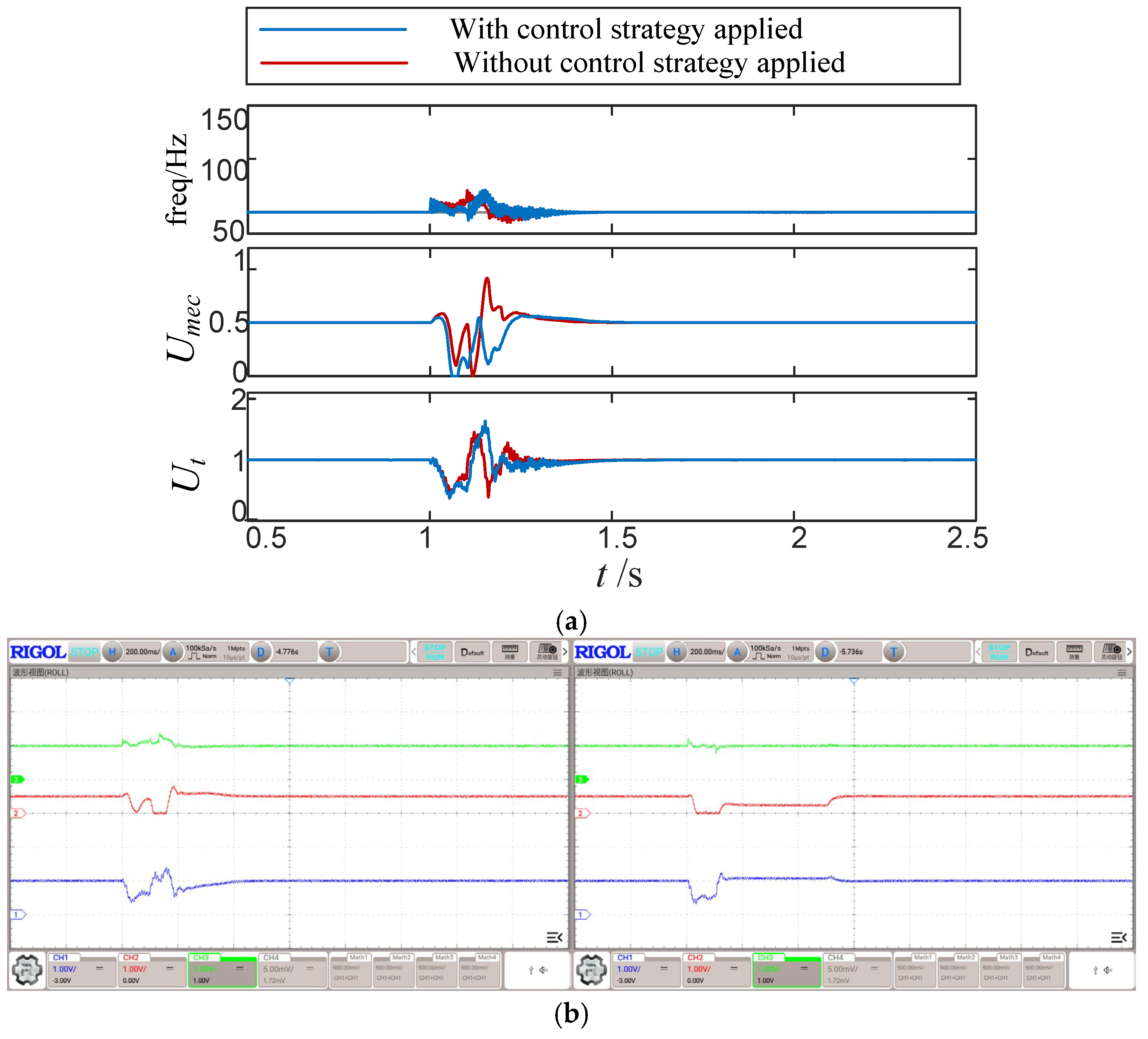

Scenario 3 (SCR = 2.5):

Figure 12a presents that the converter with high intrinsic stability margin successfully rides through the initial voltage sag stage without losing synchronization at SCR = 2.5, even without control. However, a sharp

surge appears during the voltage rebound, triggering a pronounced voltage spike at the PCC, which represents strong transient voltage impact rather than synchronism collapse. When the control strategy is activated, the

rebound is rapidly constrained, producing lower frequency excursions and faster phase-error convergence. Consequently, the PCC voltage spike and transient voltage stress are significantly mitigated, and the system exhibits improved resilience and superior stability. The results shown in

Figure 12b validate the effectiveness of the offline simulations.

The HIL simulations confirm that the proposed virtual power-angle increment feedback control effectively restrains transient divergence and reinforces converter synchronizing margin at SCR = 1.5–2.0, while also constraining voltage-rebound-induced overshoot and mitigating PCC voltage stress at SCR = 2.5. The strategy provides dual stabilization contributions in transient synchronization suppression and voltage-spike attenuation, achieving enhanced stability and reduced voltage impact for renewable energy converters.

Scenario 4 (Sensitivity and Robustness Verification):

Consistent with the simulation settings of Scenario 1 with SCR = 1.5, integral coefficients of 0.95, 1.25, and 1.45 are selected for comparison to evaluate the impact of different integral coefficients on control performance. The results are shown in the figure above.

As shown in

Figure 13, when the integral coefficient is less than the lower design limit

, red curve), the additional control exhibits poor performance in suppressing

, and the system tends to lose stability after the fault. In contrast, when

(blue curve) and

(yellow curve, which is greater than the upper design limit), the control effect is significantly improved. Among them,

achieves a faster response speed, a smaller maximum power angle deviation, and more rapid suppression of

, with a difference of 0.18 in the maximum suppression value of

between the two cases at the initial fault stage. However, due to the excessively rapid decline of

when

, severe voltage fluctuation is induced: the peak voltage during the low-voltage stage exceeds 1.1 p.u., triggering overvoltage ride-through (OVRT) control; the overvoltage peak during the voltage recovery period reaches as high as 1.5 p.u., which is higher than the 1.46 p.u. corresponding to

. Therefore, reasonably setting the integral coefficient not only helps suppress the transient deviation of frequency and power angle but also avoids frequent switching of the converter between LVRT and OVRT states, significantly improving the stability of the voltage response. This verifies the effectiveness and feasibility of the proposed parameter design method.

6. Conclusions

This paper mainly focuses on the fault ride-through parameter configuration and stability issues of renewable energy converters under low SCR conditions in the DC near-area. Firstly, modeling and analysis are conducted for grid-following converters and their PLLs. The quantitative relationship of the key parameter within the stability boundary is derived, and a calculation method for the critical ride-through coefficient and its reasonable value range under different SCRs are proposed. Further analysis indicates that frequency acceleration in the sending-end DC near-area system is the primary cause of transient instability, and there is a clear correlation with . Based on this, an additional control strategy is proposed in this paper, which dynamically adjusts the reference value through the virtual power angle increment of the PLL to maintain within the stable region, thereby effectively suppressing the risk of instability. This strategy does not rely on global information or communication, and exhibits excellent practicality for grid-following converters in scenarios with a high impedance–inductance ratio and low SCR at the sending end.

However, its adaptability to grid-forming scenarios still requires further investigation. The present study is limited to a single commutation failure event in a DC sending-end network, which, although representative, does not fully capture more severe and sustained fault conditions. Future work will extend the analysis to multiple consecutive commutation failures and the subsequent DC blocking process, where prolonged power imbalance and deeper voltage disturbances may pose greater challenges to converter synchronization and voltage support capability. In addition, a wider range of fault scenarios, including different types of AC and DC faults as well as varying grid strength conditions, will be systematically investigated. Furthermore, the proposed control framework can be further expanded and adapted to grid-forming converters, which have recently attracted significant attention due to their enhanced grid-support capability in low-inertia and low-short-circuit-ratio systems.