Real-Time Evaluation Model for Urban Transportation Network Resilience Based on Ride-Hailing Data

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A minute-level real-time resilience assessment framework is constructed. Leveraging the high spatio-temporal resolution of ride-hailing data, the granularity of resilience evaluation is enhanced from the hourly level to the minute level, enabling a fine-grained characterization of the dynamic evolution of the transportation system.

- (2)

- A multidimensional resilience indicator system is established. By introducing a transportation cost indicator and integrating supply–demand balance with operational efficiency, a comprehensive resilience evaluation system covering “supply–efficiency–cost” dimensions is developed, reflecting system performance comprehensively from the user’s perspective.

- (3)

- A hybrid LSTM-Transformer prediction model is proposed. Combining the temporal feature extraction capability of LSTM with the global attention mechanism of the Transformer, high-accuracy prediction of resilience curves is achieved, with an average prediction accuracy of 96.8%.

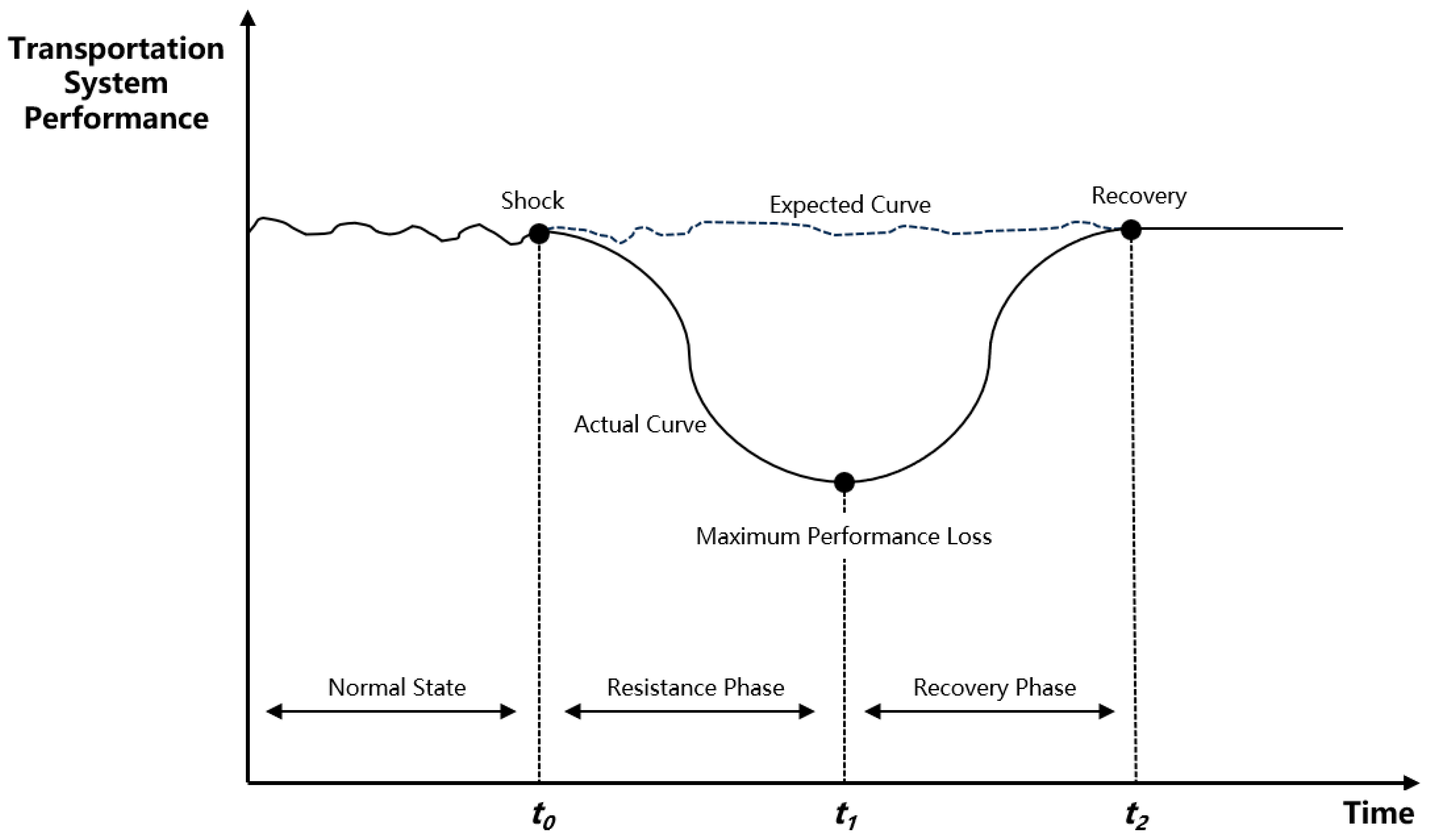

2. Methodology

2.1. Ride-Hailing Dataset and Preprocessing

- Data Acquisition: Raw data streams included (a) vehicle GPS trajectories, recorded at intervals of 10–30 s, containing Vehicle ID, timestamp, longitude, latitude, and instantaneous speed; and (b) passenger order records, generated in real-time upon trip completion, containing Order ID, Vehicle ID, pick-up/drop-off times, trip duration, and fare.

- Data Cleaning: We first removed records with obvious anomalies, including trips with zero distance, fares outside a reasonable range (e.g., below a minimum fare or exceeding a statistical threshold), and GPS points with impossible speeds (e.g., >120 km/h within the urban area). Missing timestamps or locations in contiguous records were interpolated using linear methods.

- Spatio-Temporal Aggregation: The cleaned GPS points were mapped to a city-wide grid system. All trip records and vehicle statuses were then aggregated into 5 min intervals for each grid cell. This resulted in our core time-series indicators: trip volume (F(t)), number of active vehicles (P(t)), average travel speed (TSAvag(t)), and average travel cost (TFAvg(t)).

2.2. Resilience Metrics

- (1)

- Total travel demand, F(t): Represented by the total passenger flow.

- (2)

- Supply capacity, P(t): Represented by the number of ride-hailing vehicles in operation.

2.3. Model Structure

3. Results

3.1. Ride-Hailing Dataset Description

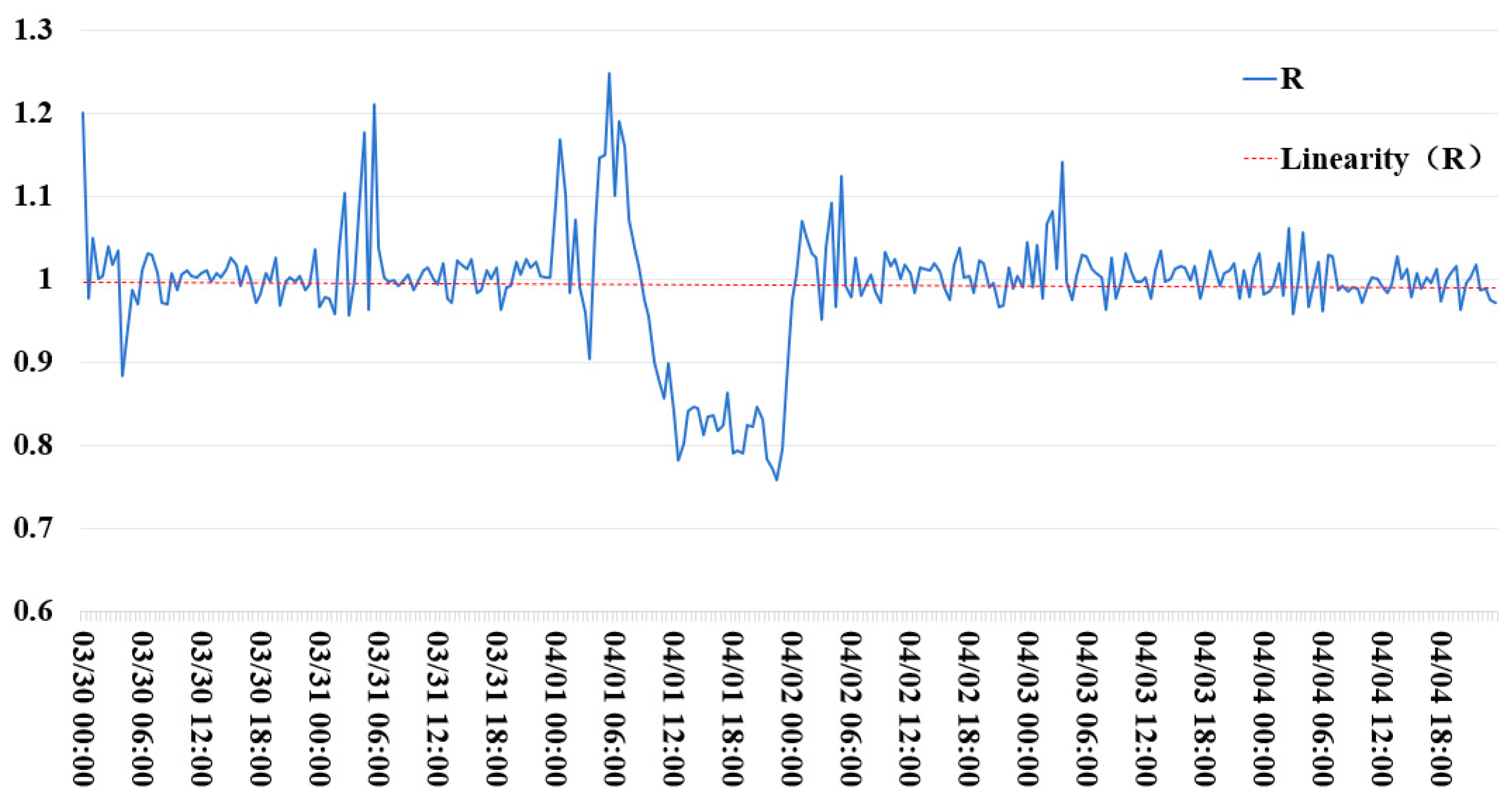

3.2. Data Prediction Results

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Du, J.; Ren, G.; Cui, J.; Cao, Q.; Wang, J.; Wu, C.; Zhang, J. Monitoring of operational resilience on urban road network: A Shaoxing case study. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2025, 257, 110836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Zhang, X.; Xue, Q.; Shi, C. Hourly-level resilience measurement model for urban transportation networks under emergencies. J. Transp. Eng. Inf. Technol. 2025, 1–18. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Hu, G.; Shi, J.; Chen, S. Research on urban transportation system resilience: Conceptions, characteristics, and key issues. City Plan. Rev. 2025, 49, 119–130. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Serdar, M.Z.; Koç, M.; Al-Ghamdi, S.G. Urban transportation networks resilience: Indicators, disturbances, and assessment methods. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 76, 103452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezvani, S.M.H.S.; Silva, M.J.F.; de Almeida, N.M. Urban Resilience Index for Critical Infrastructure: A Scenario-Based Approach to Disaster Risk Reduction in Road Networks. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, S.; Jin, L.; Cassottana, B.; Costa, A.; Sansavini, G. Developing resilience pathways for interdependent infrastructure networks. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 115, 105795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1973, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimm, S.L. The complexity and stability of ecosystems. Nature 1984, 307, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wang, J.; Yang, H. Resilience of transportation systems: Concepts and omprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2019, 20, 4262–4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.E.; Eguchi, R.T.; Lee, G.C.; O’Rourke, T.D.; Reinhorn, A.M.; Shinozuka, M.; Tierney, K.; Wallace, W.A.; Von Winterfeldt, D. A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance seismic resilience of communities. Earthquake Spectra. 2003, 19, 733–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; He, F.; Zhao, D.; Xie, M. A resilience assessment method for urban road public transportation systems based on system function curves. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2022, 62, 1016–1022. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Wang, J. Theory, methodology, and empirical study of travel resilience. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2023, 78, 2507–2519. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Li, D.; Zhu, X.; Huang, G.; Feng, H.; Zhu, S.; Li, X. A hybrid method for evaluating the resilience of urban road traffic network under flood disaster: An example of Nanjing, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 46306–46324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeing, G.; Ha, J. Resilient by design: Simulating street network disruptions across every urban area in the world. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2024, 182, 104016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henke, I.; Troiani, G.; Pagliara, F. An analysis of the vulnerability of road networks in response to disruption events through accessibility indicators specification. Transp. Plan. Technol. 2024, 47, 628–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.; Santagata, M. Vulnerability and robustness of interdependent transport networks in north-western Italy. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 2023, 15, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, S.; Zhu, W.; Cheng, G.; Zheng, J.; Zhou, J. Safety resilience assessment of urban road traffic system under rainstorm and waterlogging. China Saf. Sci. J. 2022, 32, 143–150. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Dang, Y.; Wang, H.; Hong, D.; Li, Y.; Deng, H. Resilience model and recovery strategy of transportation network based on travel OD-grid analysis. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 223, 108483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergantino, A.S.; Gardelli, A.; Rotaris, L. Assessing transport network resilience: Empirical insights from real-world data studies. Transp. Rev. 2024, 44, 834–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postorino, M.N.; Sarnè, G.M.L. A New Approach to Assessing Transport Network Resilience. Urban Sci. 2025, 9, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; He, C.; Zhang, J.; Zhai, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, L.Z.; Guo, W. Prediction of Bridge Structure Response and Resilience Assessment Under Main-Aftershock: LSTM-Transformer Model Based on Adaptive Learning Rate Framework. Eng. Struct. 2025, 345, 121449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Abdel-Aty, M.; Yu, R.; Wang, C. LSTM + Transformer Real-Time Crash Risk Evaluation Using Traffic Flow and Risky Driving Behavior Data. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 18383–18395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Liu, C. Research on the fusion application of LSTM and transformer in network traffic prediction. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Research (CAIMLR 2024), Singapore, 28–29 September 2024; Volume 13635, pp. 72–78. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Gao, N.; Miao, X.; Qi, Y.; Yang, Z. Real-Time Evaluation Model for Urban Transportation Network Resilience Based on Ride-Hailing Data. Electronics 2026, 15, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010002

Gao N, Miao X, Qi Y, Yang Z. Real-Time Evaluation Model for Urban Transportation Network Resilience Based on Ride-Hailing Data. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleGao, Ningbo, Xuezheng Miao, Yong Qi, and Zi Yang. 2026. "Real-Time Evaluation Model for Urban Transportation Network Resilience Based on Ride-Hailing Data" Electronics 15, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010002

APA StyleGao, N., Miao, X., Qi, Y., & Yang, Z. (2026). Real-Time Evaluation Model for Urban Transportation Network Resilience Based on Ride-Hailing Data. Electronics, 15(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010002