Wide Beam Analysis of Phased EM Surfaces

Abstract

1. Introduction

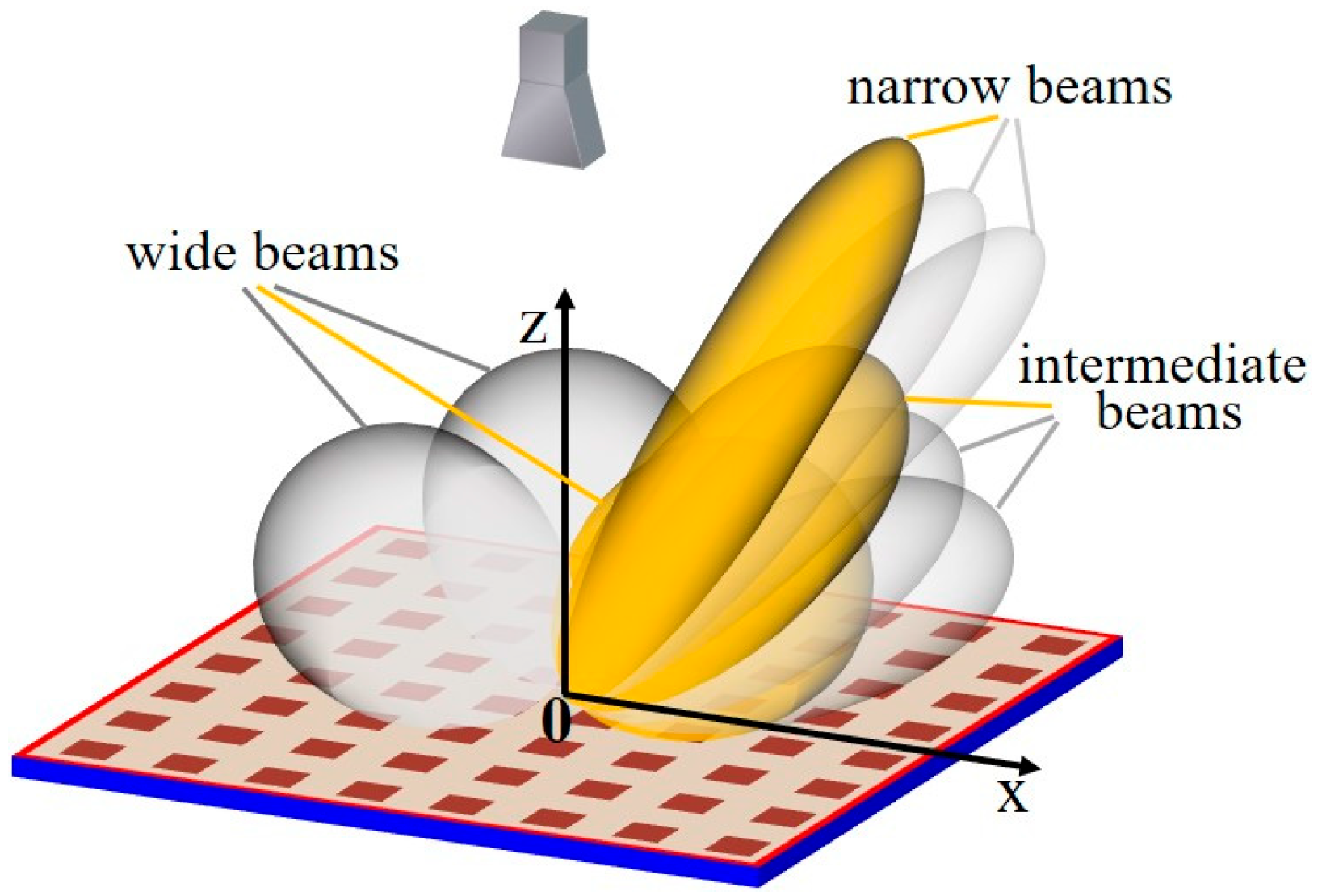

2. Problem Statement

- A fixed-size square aperture;

- A uniform aperture amplitude profile;

- A continuous aperture arrangement (non-discretized).

- What is a suitable phase distribution for wide beams?

- How do aperture parameters govern main-lobe broadening in an explicit form?

- Amplitude distribution effect, by developing parameterized tapering models that balance analytical tractability with physical realizability, and characterizing the dependencies of main-lobe distortion on amplitude distribution parameters.

- Aperture discretization impact, by defining the spectral equivalence between continuous and discretized apertures, quantifying the maximum beamwidth degradation versus element periods, and deriving discretization density requirements for target beamwidth preservation.

3. Wide Beam Forming of an Ideal Aperture

3.1. Analytical Beam Control

3.1.1. Aperture Phasing Scheme

3.1.2. Radiation Pattern Analysis via Approximation

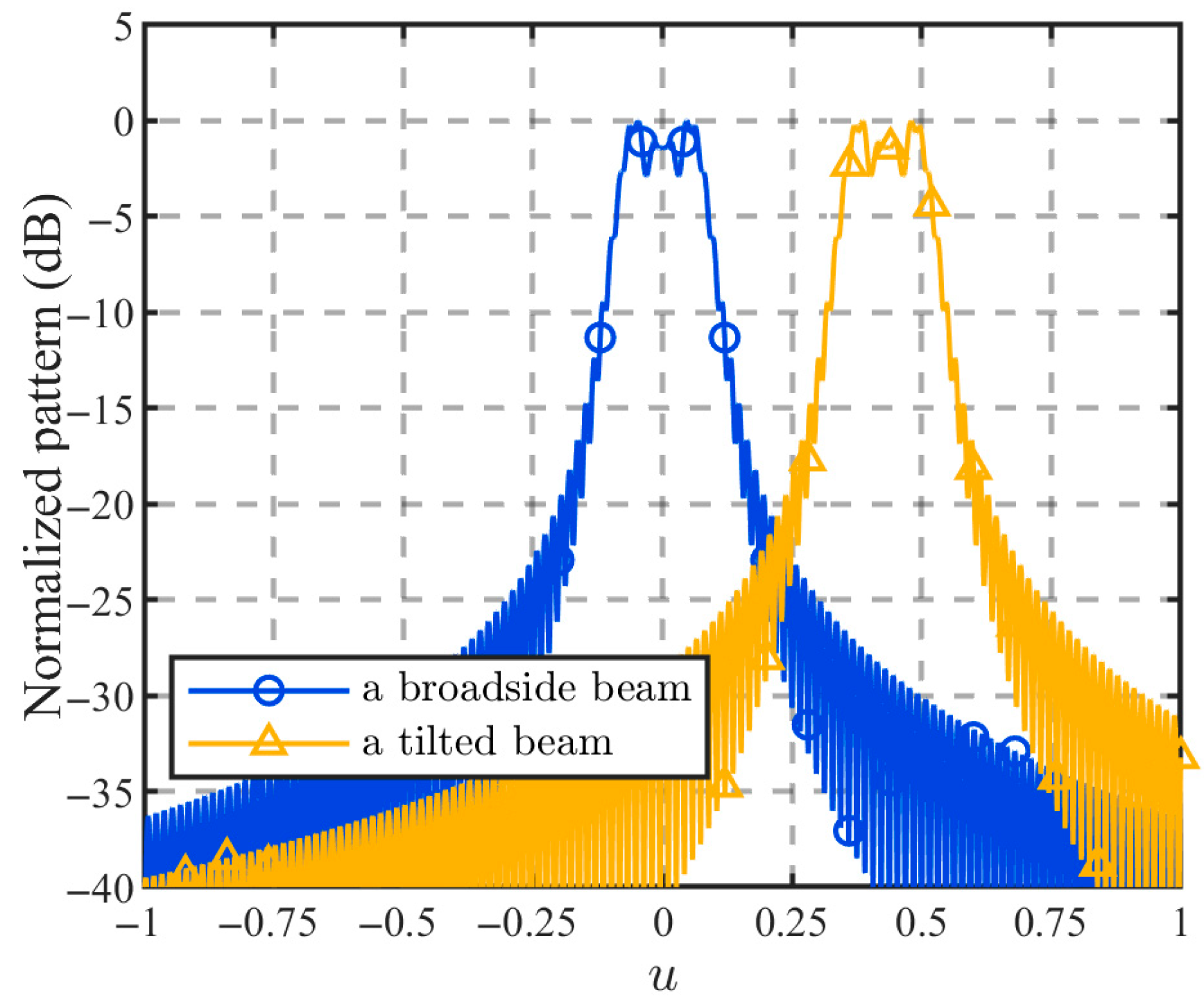

3.2. Main-Lobe Characteristics

3.2.1. 3 dB Beamwidth

3.2.2. Relative Peak Value

4. Influence of the Practical Aperture Parameters

4.1. Aperture Amplitude Taper

4.1.1. Radiation Pattern Approximation

4.1.2. Main-Lobe Analysis

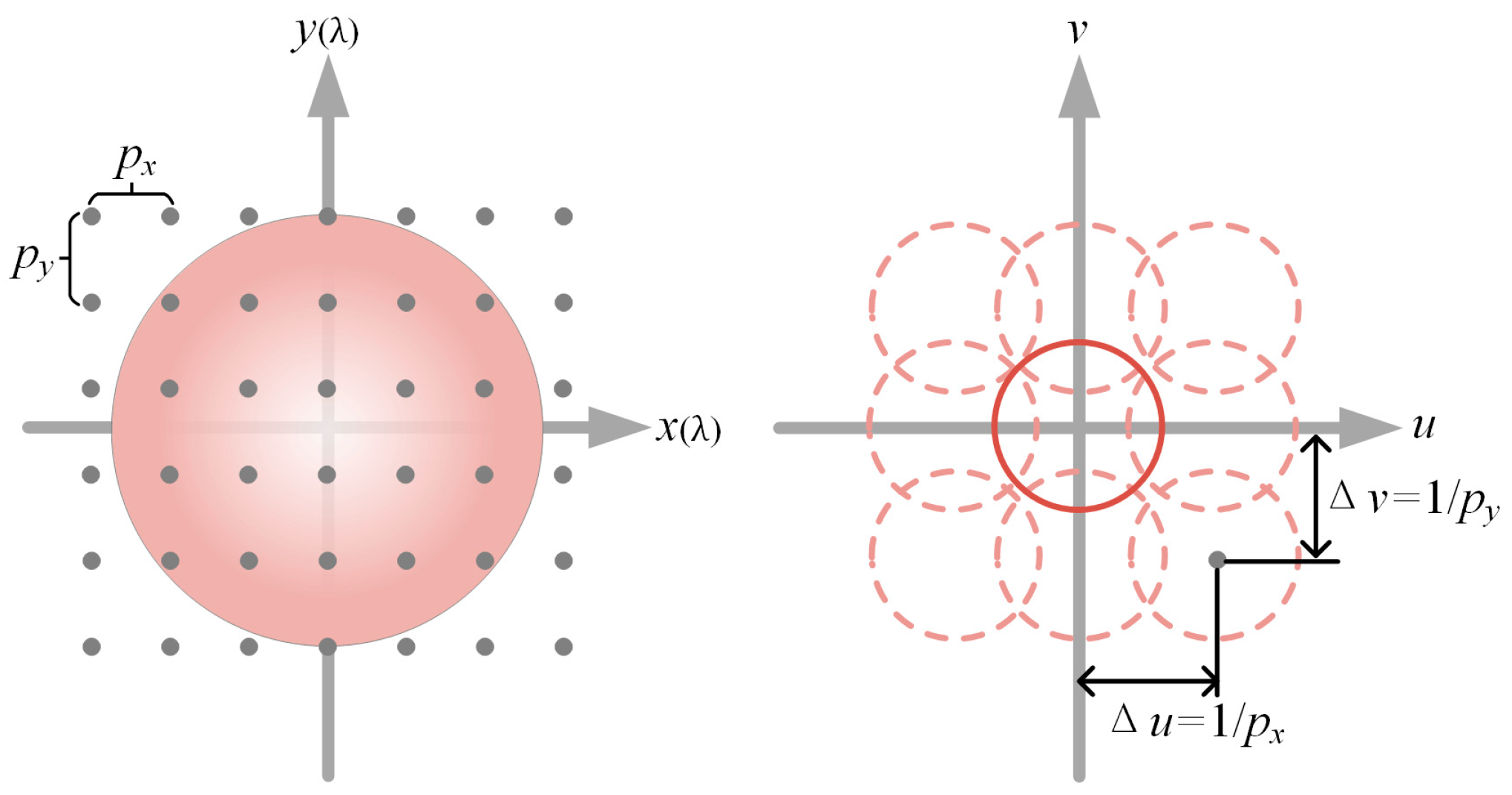

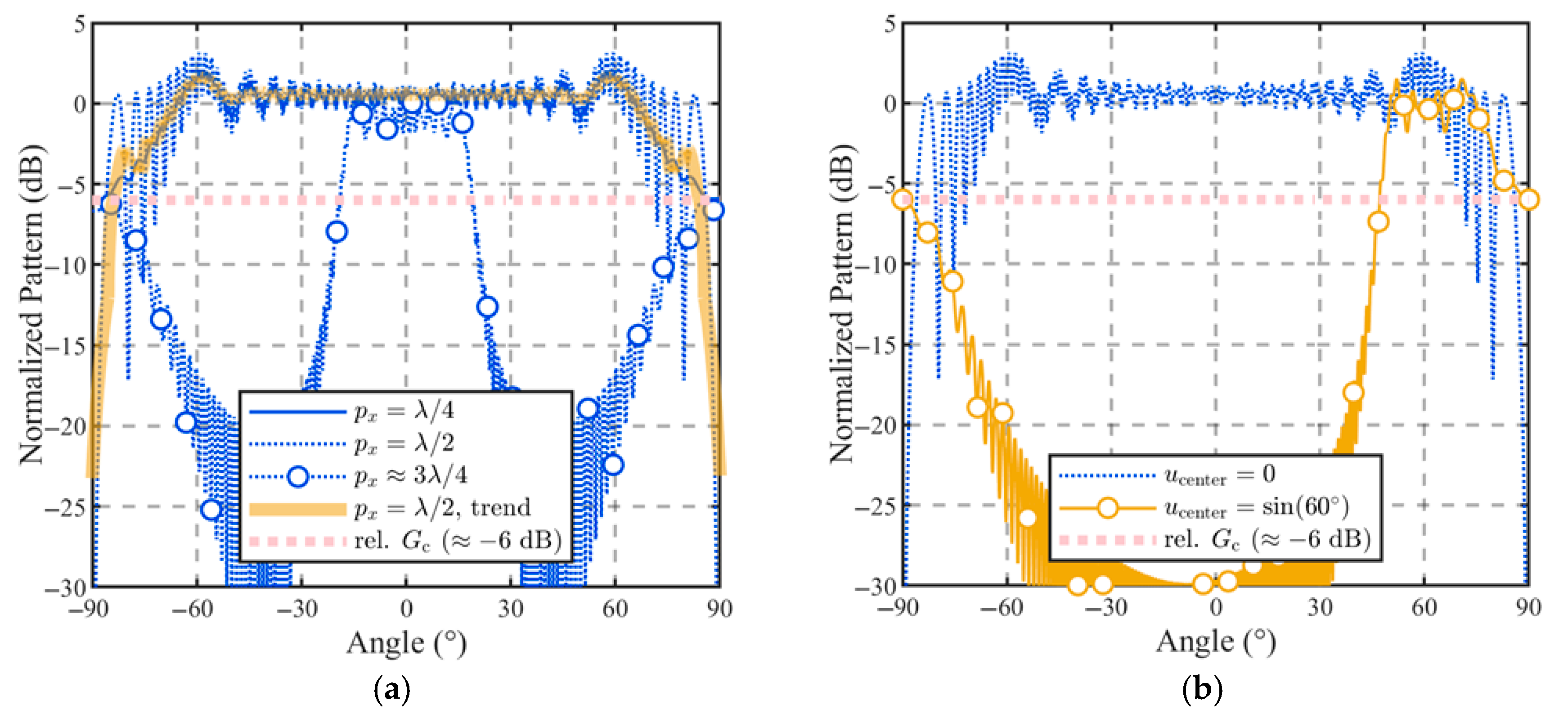

4.2. Aperture Discretization

4.2.1. Array Factor Formation

4.2.2. Wide Beam Design Guidance

5. Discussion: Generalizability and Comparison

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EM | Electromagnetic |

| ZC | Zadoff–Chu |

| DFT | Discrete Fourier transform |

| SPM | Stationary phased method |

| AF | Array factor |

References

- Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Yang, F.; Li, M. A Novel 1 Bit Wide-Angle Beam Scanning Reconfigurable Transmitarray Antenna Using an Equivalent Magnetic Dipole Element. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2020, 68, 5691–5695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Mo, Y.; Xie, W.; Hu, N.; Chen, Z.; Tian, Z. A 1-Bit All-Metal Wide-Angle and Multipolarization Beam-Scanning Reconfigurable Reflectarray Antenna. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2023, 22, 1015–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, H.; Xu, S.; Yang, F.; Li, M. Design and Experiment of a Dual-Band 1 Bit Reconfigurable Reflectarray Antenna with Independent Large-Angle Beam Scanning Capability. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2020, 19, 1896–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, H.; Du, Z.; Qi, J. A 1-Bit Programmable Reflectarray Antenna for Muti-Beam Scanning. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Microwave and Millimeter Wave Technology (ICMMT), Harbin, China, 12–15 August 2022; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, K.; Zhao, W.; Li, X.; Qiu, L.; Qi, Z. Dual-Polarized 1-Bit Reconfigurable Reflectarray for Generating Digital Vortex Beam. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Microwave and Millimeter Wave Technology (ICMMT), Qingdao, China, 14–17 May 2023; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Valera, T.; Venkatakrishnan, S.B.; Madanayake, A.; Volakis, J.L. Reconfigurable Intelligent Surfaces for Adaptive Nulling and Beam Steering Using 1-bit Topology. In Proceedings of the 2023 United States National Committee of URSI National Radio Science Meeting (USNC-URSI NRSM), Boulder, CO, USA, 10–14 January 2023; pp. 254–255. [Google Scholar]

- Aykin, I.; Akgun, B.; Krunz, M. Multi-beam Transmissions for Blockage Resilience and Reliability in Millimeter-Wave Systems. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2019, 37, 2772–2785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xu, W.; Gao, H.; Pan, M.; Han, Z.; Zhang, P. Codebook-Based Beam Tracking for Conformal Array-Enabled UAV mmWave Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 8, 244–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Choi, J.; Love, D.J. Common Codebook Millimeter Wave Beam Design: Designing Beams for Both Sounding and Communication with Uniform Planar Arrays. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2017, 65, 1859–1872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, K.; Zheng, F.-C.; Cao, P.; Xu, H.; Zhu, X. Fast Beam Training for FDD Multi-User Massive MIMO Systems with Finite Phase Shifter Resolution. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2021, 70, 459–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhateeb, A.; Leus, G.; Heath, R.W. Limited Feedback Hybrid Precoding for Multi-User Millimeter Wave Systems. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2015, 14, 6481–6494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, A.; Capek, M.; Jelinek, L.; Lehtovuori, A.; Viikari, V. Optimization of Embedded Element Patterns of Reactively Loaded Antenna Arrays. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2025, 73, 6420–6430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Ding, Z.; Chen, S.; Feng, Q.; Ran, L.; Liu, Z. Shaped pattern synthesis for hybrid analog–digital arrays via manifold optimization-enabled block coordinate descent. Signal Process. 2025, 228, 109752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Leng, P.; Chen, S.; Li, H. Phase-Only Transmit Beampattern Synthesis with Maximum Mainlobe Gain via Manifold ADMM. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2024, 23, 184–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, P.; Thompson, J.S.; Haas, H. Constant Modulus Shaped Beam Synthesis via Convex Relaxation. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2017, 16, 617–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, L.R.; Maki, A.; Gällström, A. Optimization Method for Wide Beam Sonar Transmit Beamforming. Sensors 2022, 22, 7526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, G.; Li, X.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, J. A Wideband Reconfigurable Dual-Branch Helical Reflectarray Antenna for High-Power Microwave Applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2021, 69, 825–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaz-Lueje, B.; Prado, D.R.; Arrebola, M.; Pino, M.R. Reflectarray antennas: A smart solution for new generation satellite mega-constellations in space communications. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, D.R. The Generalized Intersection Approach for Electromagnetic Array Antenna Beam-Shaping Synthesis: A Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 87053–87068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, D.R.; Naseri, P.; López-Fernández, J.A.; Hum, S.V.; Arrebola, M. Support Vector Regression-Enabled Optimization Strategy of Dual Circularly-Polarized Shaped-Beam Reflectarray with Improved Cross-Polarization Performance. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2023, 71, 497–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stutzman, W.L.; Thiele, G.A. Antenna Theory and Design, 3rd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; pp. 433–446. [Google Scholar]

- Chu, D. Polyphase codes with good periodic correlation properties. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1972, 18, 531–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Xia, X.-G.; Gao, X. Constant-envelope omni-directional transmission with diversity in massive MIMO systems. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 8–12 December 2014; pp. 3784–3789. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.; Gao, X.; Xia, X.-G. Omnidirectional Precoding Based Transmission in Massive MIMO Systems. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2016, 64, 174–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, R.; Tian, Y. Robust Wide-Beam Analog Beamforming with Inaccurate Channel Angular Information. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2018, 22, 638–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Lu, A.-A.; Meng, X.; Gao, X.; Ma, N. Broad Coverage Precoding Design for Massive MIMO with Manifold Optimization. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2019, 67, 2792–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, A.-A.; Gao, X.; Meng, X.; Xia, X.-G. Omnidirectional Precoding for 3D Massive MIMO with Uniform Planar Arrays. IEEE Trans. Wirel. Commun. 2020, 19, 2628–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orfanidis, S.J. Electromagnetic Waves and Antennas; ECE Dept., Rutgers Univ.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2016; p. 751. [Google Scholar]

- Dolph, C.L. A Current Distribution for Broadside Arrays Which Optimizes the Relationship between Beam Width and Side-Lobe Level. Proc. IRE 1946, 34, 335–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riblet, H.J. Discussion on “A Current Distribution for Broadside Arrays Which Optimizes the Relationship between Beam Width and Side-Lobe Level”. Proc. IRE 1947, 35, 489–492. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott, R.S. Beamwidth and directivity of large scanning arrays—First of two parts. Microw. J. 1963, 53–60. Available online: http://sina.sharif.edu/~aborji/25149/files/Beamwidth%20and%20directivity%20of%20large%20scanning%20arrays%20-%20first%20of%20two%20parts.pdf (accessed on 23 December 2025).

| Parameters | Specifications |

|---|---|

| Calculation Method | Array Factor Summation (approximating continuous aperture integral) |

| Element Spacing (p) | p << λ/2 (Baseline; discretization impacts are examined in Section 4.2) |

| Aperture Sizes (L × L) | 16λ × 16λ (Figure 5a); 64λ × 64λ (Figure 5b) |

| Amplitude Distribution | Uniform (Baseline; tapering effects are examined in Section 4.1) |

| Aperture Phase Distribution | Quadratic phase profile (following Equation (1)) |

| Aperture Parameters (L & a) | Method | BW6dB (°) | BW3dB (°) | Rel. Gpeak 1 (dB) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16λ & 0.16 | Estimated 2 | 48.1 | 42.3 | 1.4 |

| Calculated 3 | 48.4 | 40.7 | 1.4 | |

| 64λ & 0.04 | Estimated | 48.1 | 45.2 | 1.4 |

| Calculated | 47.3 | 43.6 | 1.1 |

| BWc 1 | Max. p (ucenter 2 = 0) | Max. p (ucenter = sin 60°) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.52 (30°) | 0.79 | 0.47 |

| 1.00 (60°) | 0.67 | 0.42 |

| 1.41 (90°) | 0.59 | 0.39 |

| 2.00 (180°) | 0.50 | 0.35 |

| p (λ) | Max. BWc 1 (ucenter = 0) | Max. BWc (ucenter = sin 60°) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | omni | omni |

| 1/4 | omni | omni |

| 1/2 | omni | 0.27 (42.9°) |

| 3/4 | 0.67 (38.9°) | GLL > −6 dB |

| 1 | GLL > −6 dB | GLL > −6 dB |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

He, J.; Yang, F.; Xu, X.; Xu, S. Wide Beam Analysis of Phased EM Surfaces. Electronics 2026, 15, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010191

He J, Yang F, Xu X, Xu S. Wide Beam Analysis of Phased EM Surfaces. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010191

Chicago/Turabian StyleHe, Jiayue, Fan Yang, Xiaotao Xu, and Shenheng Xu. 2026. "Wide Beam Analysis of Phased EM Surfaces" Electronics 15, no. 1: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010191

APA StyleHe, J., Yang, F., Xu, X., & Xu, S. (2026). Wide Beam Analysis of Phased EM Surfaces. Electronics, 15(1), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010191