A Clustering and Reinforcement Learning-Based Handover Strategy for LEO Satellite Networks in Power IoT Scenarios

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

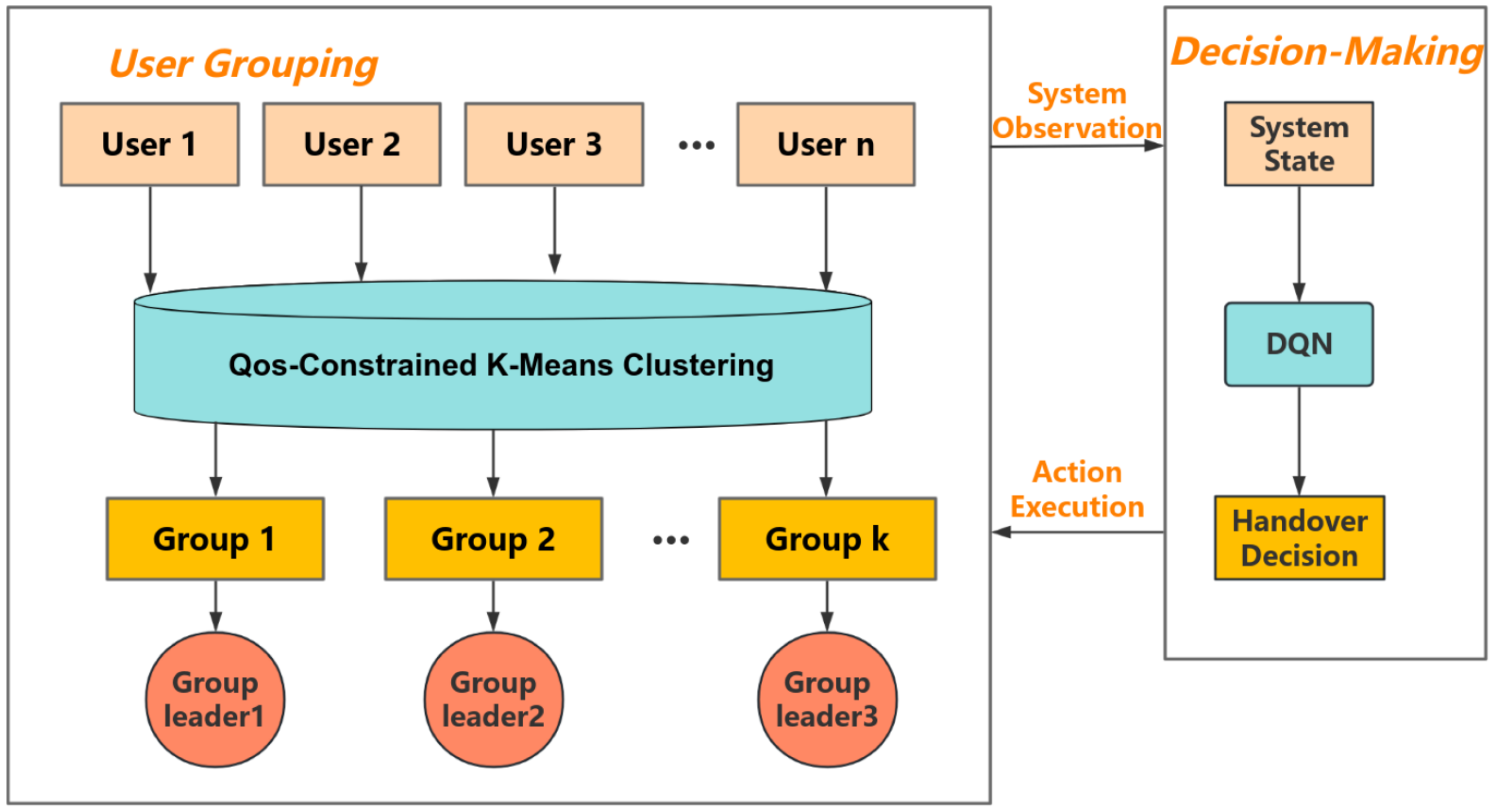

- Proposing a user clustering algorithm with QoS fairness constraints for power IoT services: Addressing the shortcoming of traditional clustering methods that overlook inter-user QoS variations within groups, which may degrade the transmission performance of critical power monitoring and control information, this paper incorporates a QoS variance constraint into the K-Means algorithm. Groups where the variance of the aggregate QoS scores among users exceeds a predetermined threshold are subsequently disaggregated. This prevents users with vastly differing QoS requirements from being grouped together, ensuring balanced QoS distribution within each cluster and thereby achieving fairer user grouping.

- -

- Establishing a Hierarchical DQN-based group handover decision framework tailored to power IoT access: To address the state space explosion in scenarios with a large number of power IoT terminals transmitting periodic telemetry data and occasional emergency signaling, this paper designs a hierarchical decision architecture combining user clustering with DQN. At the start of each DQN round, user clustering is performed to select a cluster leader for each group. Subsequently, the cluster leader represents the entire group for DQN training and decision-making. This approach significantly reduces computational complexity and signaling overhead, enhancing the algorithm’s computational efficiency and scalability when supporting long-term and large-scale power system communications over LEO satellite networks.

2. Materials and Methods

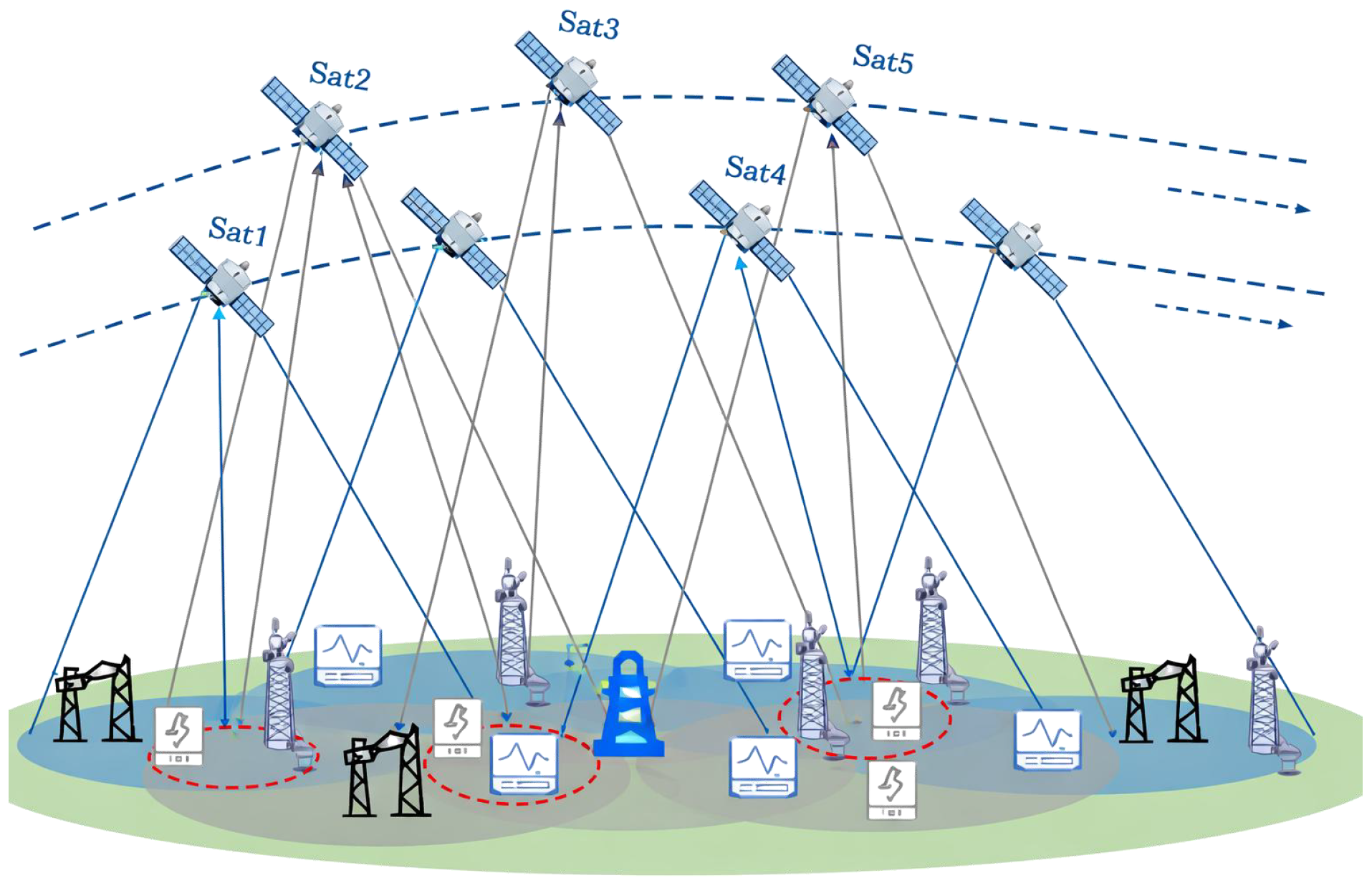

2.1. System Model

2.2. Handover Decision Factor Analysis

2.2.1. Transmission Latency

2.2.2. Data Transmission Rate

2.2.3. Remaining Service Duration

2.3. Problem Description

3. Research on LEO Satellite Handover Strategies Based on Constrained K-Means Clustering and DQN

3.1. User Grouping

| Algorithm 1: K-Means User Clustering Algorithm with QoS Constraints |

| Input: User set U, feature data F, variance threshold , initial number of clusters K |

| Output: Clustering result G, set of cluster leaders L |

| Initialization: Divide users U into K groups using K-Means based on their feature vectors F |

| 1: For in G |

| 2: Calculate the variance of QoS within the groups |

| 3: If var_g > max_var Then |

| 4: Split group g into and based on the median QoS |

| 5: Update the grouping set G |

| 6: End If |

| 7: All groups satisfy variance constraints |

| 8: End For |

| 9: For each group g, select argmax() as the group leader |

| 10: Return G, L |

3.2. DQN Algorithm

- State Space

- B.

- Action Space

- C.

- Reward Function

3.3. LEO Satellite Handover Strategy Based on QoS-Constrained K-Means Clustering and DQN

| Algorithm 2: Cluster-Based DQN Satellite Handover Algorithm |

| Initialization: satellite environment, DQN network, and clustering algorithm |

| Training: |

| 1: For episode = 1 to M Do |

| 2: Perform user clustering once per episode (Algorithm 1) |

| 3: For each cluster leader : |

| 4: Obtain state |

| 5: DQN selects action |

| 6: All members within the group execute action |

| 7: Calculate group average reward |

| 8: Store experience |

| 9: Sampling from the experience pool and updating DQN parameters |

| 10: End For |

4. Results

4.1. Simulation Setup

4.2. Learning Convergence Analysis

4.3. Comparison of Algorithm Performance

- Handover Frequency:

- Signaling overhead:

5. Discussion and Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, C.; Zheng, L.; Zhao, Z.; Lv, Z.; Jiang, X.; Liu, H.; Yuan, C. Research on Communication Solutions Under the Background of New Power System. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Power System Technology (PowerCon), Jinan, China, 21–22 September 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Shi, Z.; Chen, X. Research on Protocol Conversion of Satellite Communication in Power Multi-Service Scenario. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 3rd Advanced Information Management, Communicates, Electronic and Automation Control Conference (IMCEC), Chongqing, China, 11–13 October 2019; pp. 1628–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Shu, L.; Chen, H.; Zeng, X.; Ye, H.; Zhou, J.; Deng, F. Application of Beidou satellite timing and communication technology in power system fault location. In Proceedings of the 2015 5th International Conference on Electric Utility Deregulation and Restructuring and Power Technologies (DRPT), Changsha, China, 26–29 November 2015; pp. 1224–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancillotti, E.; Bruno, R.; Conti, M. The role of communication systems in smart grids: Architectures, technical solutions and research challenges. Comput. Commun. 2013, 36, 1665–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisu, A.A.; Sun, H.; Gallant, A. Integrated Satellite-Terrestrial Network for Smart Grid Communications in 6G Era. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 15th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 6–8 January 2025; pp. 1044–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuzlu, M.; Pipattanasomporn, M. Assessment of communication technologies and network requirements for different smart grid applications. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE PES Innovative Smart Grid Technologies Conference (ISGT), Washington, DC, USA, 24–27 February 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, C.; He, X.; Ding, X. Traffic Analysis of LEO Satellite Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2019 15th International Wireless Communications & Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC), Washington, DC, USA, 24–27 February 2019; pp. 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meloni, A.; Atzori, L. The Role of Satellite Communications in the Smart Grid. IEEE Wirel. Commun. 2017, 24, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Lee, Y.; Lee, D.; Kim, G.; Win, T.T.; Cho, S. A Survey on Satellite and Ground Integrated Network Systems. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN), Chiang Mai, Thailand, 15–17 January 2025; pp. 711–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Ye, Z.; Wu, M.; Li, H.; Xiao, M.; Alouini, M.S.; Al-Hourani, A.; Cioni, S. Space-Air-Ground Integrated Wireless Networks for 6G: Basics, Key Technologies, and Future Trends. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2024, 42, 3327–3354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y. A Successive Deep Q-Learning Based Distributed Handover Scheme for Large-Scale LEO Satellite Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 95th Vehicular Technology Conference: (VTC2022-Spring), Helsinki, Finland, 19–22 June 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, P.C.; Qu, H.; Zhao, J.H.; Wang, M.; Wang, K.; Liu, X. An inter satellite link handover management scheme based on link remaining time. In Proceedings of the 2016 2nd IEEE International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 14–17 October 2016; pp. 1799–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Jin, F.; Luo, J.; Fu, Y.; Shan, J.; Hu, G. A Graph-Based Satellite Handover Framework for LEO Satellite Communication Networks. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2016, 20, 1547–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Song, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, X.; Wang, W.; Wamg, C. Real-time prediction and update method of LEO inter-satellite switching based on time evolution graph. J. Commun. 2018, 39, 43–51. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, A.; Liang, X. A Multi-objective Satellite Handover Strategy Based on Entropy in LEO Satellite Communications. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 6th International Conference on Computer and Communications (ICCC), Chengdu, China, 11–14 December 2020; pp. 723–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hozayen, M.; Darwish, T.; Kurt, G.K.; Yanikomeroglu, H. A Graph-Based Customizable Handover Framework for LEO Satellite Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 4–8 December 2022; pp. 868–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, C.Q.; Liu, Y.; Fu, S.; Wu, J.; Chen, Q. Dynamic Handover in Satellite-Terrestrial Integrated Networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Globecom Workshops (GC Wkshps), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 9–13 December 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhang, D.; Qiu, F. Multi-Attribute Handover Control Method for LEO Satellite Internet. J. Army Eng. Univ. 2022, 1, 14–20. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, K.; Hua, C.; Gu, P.; Xu, W. User Clustering and Proactive Group Handover Scheduling in LEO Satellite Networks. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Computing, Communications and IoT Applications (ComComAp), Beijing, China, 20–22 December 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Bu, Z. A Group Handover Strategy for Massive User Terminals in LEO Satellite Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 96th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2022-Fall), London, UK, 26–29 September 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongtao, Z.; Zhenyong, W.; Dezhi, L.; Mingchuan, Y.; Qing, G. Double grouping-based group handover scheme for mega LEO satellite networks. China Commun. 2025, 22, 77–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, S.; Zhao, K.; Li, W.; Ye, Y.; Fang, Y. Handover Algorithm Based on User Clustering and Graph Matching for Large-Scale LEO Satellite Network. In Proceedings of the 2025 10th International Conference on Computer and Communication System (ICCCS), Chengdu, China, 18–21 April 2025; pp. 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Liu, L. Joint User Association and Handover Strategy for Large Scale LEO Satellite Constellation Networks. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Communication Technology (ICCT), Wuxi, China, 20–22 October 2023; pp. 880–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Yang, X.; Bu, Z. Multi-layer Graph Based Inter-Satellite Group Handover Strategy in LEO-IoT Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025; 1, early access. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Jung, S. Low Earth Orbit Satellite Scheduling Optimization Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Information and Communication Technology Convergence (ICTC), Jeju Island, Republic of Korea, 16–18 October 2024; pp. 518–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Gao, W.; Zhang, K. A Graph Reinforcement Learning-Based Handover Strategy for Low Earth Orbit Satellites under Power Grid Scenarios. Aerospace 2024, 11, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, B. DQN-Based Conditional Handover Algorithm for Leo Satellites Networks. In Proceedings of the 2025 8th International Conference on Electronics Technology (ICET), Chengdu, China, 17–20 May 2025; pp. 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, C.; Li, B. DQN-based Network Selection and Load Balancing for LEO Satellite-Terrestrial Integrated Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th World Conference on Computing and Communication Technologies (WCCCT), Chengdu, China, 12–14 April 2024; pp. 233–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Zhou, D.; Sheng, M.; Shi, Y.; Wang, N.; Li, J. Reinforcement Learning-Based Handover Strategy for Space-Ground Integration Network with Large-Scale Constellations. J. Commun. Inf. Netw. 2022, 7, 421–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majid, A.Y.; Saaybi, S.; Francois-Lavet, V.; Prasad, R.V.; Verhoeven, C. Deep Reinforcement Learning Versus Evolution Strategies: A Comparative Survey. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 11939–11957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Tam, F.; Correia, N.; Rodriguez, J. Learn to Schedule (LEASCH): A Deep Reinforcement Learning Approach for Radio Resource Scheduling in the 5G MAC Layer. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 108088–108101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lahmeri, M.A.; Kishk, M.A.; Alouini, M.S. Artificial Intelligence for UAV-Enabled Wireless Networks: A Survey. IEEE Open J. Commun. Soc. 2021, 2, 1015–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| User centre position (Latitude, Longitude, Altitude) | (−62°, 50°, 0 m) |

| Simulation time (minutes) | 30 |

| Number of total time slots | 60 |

| Satellite altitude (km) | 550 |

| Simulation commencement time | 05-01-2023 09:30 a.m. (UTC) |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Discount factor | 0.6 |

| Learning rate | 0.001 |

| Initial exploration rate | 1.0 |

| Termination exploration rate | 0.005 |

| Training batch size | 32 |

| Q-target network parameter update step (episodes) | 100 |

| DQN iteration count | 1000 |

| Loss Function | MSE Loss |

| Optimizer | Adam |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Shao, J.; Gao, W.; Liu, K.; Qiao, R.; Yu, H.; Zhang, K.; Zhao, X.; Duan, J. A Clustering and Reinforcement Learning-Based Handover Strategy for LEO Satellite Networks in Power IoT Scenarios. Electronics 2026, 15, 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010174

Shao J, Gao W, Liu K, Qiao R, Yu H, Zhang K, Zhao X, Duan J. A Clustering and Reinforcement Learning-Based Handover Strategy for LEO Satellite Networks in Power IoT Scenarios. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):174. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010174

Chicago/Turabian StyleShao, Jin, Weidong Gao, Kuixing Liu, Rantong Qiao, Haizhi Yu, Kaisa Zhang, Xu Zhao, and Junbao Duan. 2026. "A Clustering and Reinforcement Learning-Based Handover Strategy for LEO Satellite Networks in Power IoT Scenarios" Electronics 15, no. 1: 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010174

APA StyleShao, J., Gao, W., Liu, K., Qiao, R., Yu, H., Zhang, K., Zhao, X., & Duan, J. (2026). A Clustering and Reinforcement Learning-Based Handover Strategy for LEO Satellite Networks in Power IoT Scenarios. Electronics, 15(1), 174. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010174