1. Introduction

Analog-to-digital conversion technology is essential for transforming continuous analog signals into discrete digital representations. Traditional analog-to-digital converters (ADCs) rely on the Shannon–Nyquist sampling theorem, which requires the sampling rate to be at least twice the highest frequency component of the signal to ensure accurate reconstruction. However, as the bandwidth of analog signals continues to increase, the Nyquist rate has become a significant limitation in the advancement of ADC technology [

1].

Event-driven ADCs [

2] offer significant advantages when handling sparse signals, such as biological signals [

3], as well as in radar and remote sensing applications. Some of the proposed approaches in the event-driven ADCs employ one or two digital-to-analog converters (DACs), which adjust the threshold during the acquisition process [

4]. This approach is affordable for biological signals but not scalable to GHz frequencies of radio frequency (RF) applications due to the necessity of updating DAC sweeps at frequencies close to the Nyquist rate.

Employment of a time-to-digital converter (TDC) for the implementation of an event-driven ADC allows sampling signals in the GHz range, as modern TDCs [

5] have resolutions in the picosecond range. Several approaches can be used to obtain amplitude information from the time stamps.

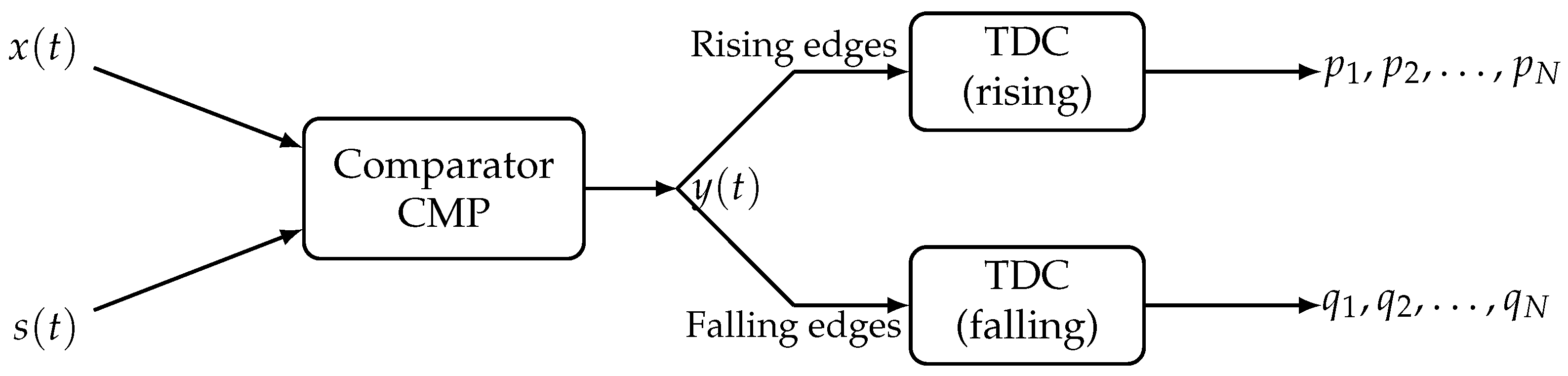

A straightforward approach would be to have multiple comparators tuned to different amplitude values, which allows for obtaining amplitude information together with timing, as shown in

Figure 1. The input signal is continuously compared against several thresholds (four in the given example), and when it crosses the threshold, a short pulse is emitted. Pulses are processed by an array of TDCs, providing conversion of the analog signal into a series of time stamps.

This approach is easily scalable to many GHz and, in theory, can provide very high performance [

6]. However, to achieve a high dynamic range, it is necessary to use many comparators and TDCs, resulting in a large number of time tags to be processed. An approach with multiple level crossings can also be used for activity detection [

7] and other tasks where timing is more critical than the accuracy of amplitude measurement.

The use of a dynamic threshold in event-based sampling enables the development of new methods for signal acquisition. When the reference waveform varies faster than the signal of interest, the signal can be digitized in a single shot using a high-speed TDC. Ramp ADCs employ a sawtooth signal [

8,

9] for converting time to amplitude, demonstrating good reconstruction accuracy (low noise), high energy efficiency, and potential in multi-channel sensor signal acquisition. Employment of a ramp (sawtooth) signal leads to a simplified reconstruction algorithm without reference signal lookup at the crossing point, as the amplitude of the acquired signal is directly proportional to the time tag within the sampling cycle. Such architecture can be used only if the reference waveform has a significantly higher frequency than the bandwidth of the signal of interest, therefore eliminating the possibility of double crossings within a single ramp. In other publications [

10], it is proposed to work with a sine wave, which is easier to generate; however, during reconstruction, the nonlinearity of the reference waveform must be taken into account.

Conversely, when the reference waveform operates at a lower frequency than the target signal, a stroboscopic event-driven ADC architecture can be implemented. Such an approach can be efficiently employed when signals are periodic and evolve only slightly over hundreds of periods. Examples of this could be biological signals or radar [

11].

In a dynamic threshold event-driven ADC, selecting the reference waveform is a crucial task, as it affects acquisition accuracy and aliasing effects, similar to those encountered in periodic sampling. In works [

12,

13], it is demonstrated that randomized sampling enables the overcoming of the aliasing problem and, in general, yields better results.

DAC-based level-crossing ADCs (LC-ADCs) architectures do not support multi-GHz operation due to DAC sweep speed limitations. Our approach eliminates the DAC and replaces it with broadband periodic reference waveforms, which are compared against the signal using a high-speed comparator. Combined with a multi-channel, high-precision TDC, this enables a passive high-speed digitizer.

As a matter of principle, the proposed reference-crossing combined with TDC architecture is particularly attractive when (i) the information content is sparse or bursty in time and/or (ii) the system must scale to a large number of channels, such that total ADC power and output data rate become dominant constraints. Since conversion is event- and timing-based and supports stroboscopic acquisition, high-bandwidth signal information can be captured using a relatively low-frequency reference waveform while keeping the per-channel front-end simple and enabling efficient scaling with low-power TDC arrays. Accordingly, representative application domains include ultra-wideband (UWB) radar/sonar reception (sparse echoes, scalable channel count), bio-potential recording such as electroencephalogram (EEG) (spikes and transients separated by quiet intervals), and seismic sensing (impulsive events with long idle periods). In addition, the aggregate event throughput can be increased by paralleling multiple TDC channels, which can be competitive in multi-channel systems where conventional ADCs are limited primarily by power and data volume.

The main novelty of this paper lies in the employment of arbitrarily chosen reference waveforms whose frequency is orders of magnitude lower than the bandwidth of the signal of interest, thereby demonstrating a novel method of stroboscopic sampling and reconstruction of high-bandwidth signals. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

A new architecture for passive high-speed signal digitization using low-frequency reference waveform crossings and TDC time-tagging.

Demonstration of stroboscopic sampling using triangle, sine, and sawtooth reference waveforms up to 3 with 5 test signals and comparison of the effectiveness of different reference waveforms.

Reconstruction of simple (sine/sawtooth) and complex (damped sine, chirp) signals.

Analysis of edge selection, crossing density, and reconstruction accuracy.

Experimental demonstration using a 30 precision time tagger based on the commercial GPX2 TDC.

2. Method

2.1. Principle of Waveform-Crossing Event Sampling

The sampling method employs event-based sampling with a dynamic threshold. The principle of sampling is shown in

Figure 2. The input waveform

is sent to a high-speed comparator circuit CMP. The second input of the comparator is connected to the reference waveform

, which serves as the “sampling waveform”. The output of the comparator

is high when

(see

Figure 3). Therefore, the comparator performs quantization of the

at a level defined by

.

The rectangular pulses from the comparator are processed by two channels of TDC, one channel for the rising edges of the comparator signal and the other for the falling. The resulting time stamps and digitally represent information about the amplitude and timing of the signal of interest .

In some applications, such as sensing (radar, lidar, sonar), timestamps can be directly used for object detection without the need to recover

. However, if such reconstruction is necessary, the reverse process shown in

Figure 4 must be performed. Given that the value of sampling function

is known for all values of time tags, i.e.,

and

are known, reconstruction is reduced to the interpolation between points

and

.

It is essential to note that in some cases, it is sufficient to register times of only one type of edge, for example, just the rising edge. It strongly depends on the waveform and frequency of compared with .

2.2. Selection of the Sampling Function

The choice of the sampling function is critical for event-based sampling with a dynamic threshold, since the reconstruction procedure relies on evaluating at the detected time tags and . In general, the sampling function should exhibit a nonzero local slope near the threshold-crossing instants, i.e., , to ensure that each crossing is uniquely defined and not sensitive to jitter. The function must be known analytically or be available as a high-resolution discrete representation, enabling accurate computation of and . To ensure stable operation, should avoid long flat regions or repeated values, which lead to ambiguous crossings, and its bandwidth and slew rate should be compatible with the desired trade-off between temporal and amplitude resolution.

Both periodic and nonperiodic choices of are possible. Periodic sampling functions (e.g., sinusoidal or triangular) provide highly repeatable crossings, are easy to generate, and are suitable for continuous or stroboscopic acquisition of repetitive RF signals. In contrast, nonperiodic sampling functions (e.g., chirps or deterministic aperiodic sequences) help avoid phase-locking effects and repeated amplitude configurations, offering richer crossing diversity and improved reconstruction robustness, which is beneficial for acquiring wideband or transient signals.

The reconstruction accuracy in event-based sampling is fundamentally limited by the timing uncertainty of the TDC and by the relative slope between the sampling function and the test signal at the threshold-crossing moment. For a small TDC jitter , the corresponding amplitude error can be approximated as , meaning that the reconstruction error is inversely proportional to the relative slope between the sampling function and test signal: steeper slopes reduce the sensitivity to timing noise, while shallow slopes amplify it.

A triangular sampling function provides the most uniform performance because its slope is constant in magnitude over each half-period, resulting in an approximately uniform amplitude-to-time mapping and therefore a uniform reconstruction error distribution across all crossings.

A sinusoidal reference produces a strongly nonuniform density of samples because its slope varies from zero at the extrema to a maximum at the zero crossings; consequently, crossings near the peaks suffer from considerable amplitude uncertainty due to the small , while crossings near the midpoints benefit from significantly lower error.

A sawtooth waveform represents the opposite extreme: it has a nearly constant positive slope along most of its period, but the abrupt reset produces a significant discontinuity in that leads to a highly dense cluster of crossings near the discontinuity and very sparse sampling elsewhere. Moreover, because the sawtooth is strictly monotonic within a period, the crossing time is directly proportional to the amplitude value of , effectively inverting the amplitude-to-time relationship compared with symmetric waveforms such as sine or triangle. This inversion must be accounted for during reconstruction but does not affect the underlying error mechanism, which remains governed by the ratio between the TDC jitter and the instantaneous slope of the reference waveform.

2.3. Stroboscopic Sampling

Stroboscopic sampling can be applied when both the signal of interest and the sampling function are periodic. In this regime, the comparator detects crossings between two periodic waveforms, and the resulting time tags provide samples taken at effectively shifted phases of . The key requirement for successful stroboscopic acquisition is that the frequencies of the two periodic signals must not be identical or commensurate with each other. If the frequency ratio is rational or too close to unity, the system enters a phase-locked condition in which crossings repeat at the same relative phase each cycle, producing no new information. Therefore, a small but controlled frequency offset is introduced to ensure that the sampling phase drifts slowly over time, enabling dense coverage of the entire period of through successive crossings. This principle is essential for avoiding aliasing-like degeneracies and ensuring that the reconstructed waveform is based on a complete and non-redundant set of threshold-crossing instants.

2.4. Design Guidelines for Reference Waveform and Parameter Selection

The proposed digitizer represents the input signal by the time instants of crossings between the input and a known periodic sampling waveform. For an ADC based on reference-crossing time tags, reconstruction accuracy is primarily limited by the mapping of timing uncertainty (comparator noise, TDC quantization, and jitter) into an equivalent amplitude error. Around each crossing event at time

, a small timing error

produces an amplitude error approximately proportional to the local relative slope

:

where

is the sampling waveform and

is the effective timing uncertainty (including the comparator and the TDC). Equation (

1) motivates the following practical guidelines for choosing

and for selecting key design parameters.

Prefer sampling waveforms with a nonzero and uniform slope magnitude. A robust default is a triangular sampling waveform, which provides an approximately constant over each half-period and therefore yields a more uniform error distribution across crossings.

Sine reference: simple generation but amplitude-dependent sensitivity. A sinusoidal sampling waveform exhibits near its extrema, which increases for crossings occurring in those regions. If a sine reference is used, improved robustness can be achieved by (i) avoiding extrema crossings via amplitude scaling/offset or (ii) combining multiple reference phases (multiple channels).

Sawtooth/ramp reference: near-constant slope with a critical reset region. A sawtooth (or ramp) provides an almost constant slope for most of the period, but the reset discontinuity can cause clustered events and increased sensitivity to comparator bouncing and TDC throughput limits. In practice, the reset interval should be handled explicitly (blanking/masking window, soft-reset waveform, or separate reset marker).

Select the reference frequency from the event-rate budget (not a Nyquist criterion). Increasing the reference frequency generally increases the crossing density but also increases the event rate. Let

denote the maximum sustainable event rate of the combined comparator–TDC–readout chain (including dead time and buffering) and

B the bandwidth of the signal to be digitized. To not lose events, the design should maintain a margin:

Stroboscopic operation: avoid commensurate frequency ratios. For periodic inputs in stroboscopic mode (where the reference frequency is lower than the signal bandwidth), commensurate ratios can result in repeated crossing phases and limited information gain. A minor intentional frequency offset should be used to ensure phase walk-off and complete phase coverage over the acquisition window.

Mitigate false events due to low relative slope and noise. When the relative slope is small, input noise can produce rapid toggling at the comparator output. Practical countermeasures include comparator hysteresis, minimum inter-event time filtering (TDC dead time helps here), and (where feasible) post-processing that removes implausible bursts.

Track and stabilize the reference phase on the same time base. Since reconstruction evaluates , the phase of should be known relative to the TDC time base. A practical solution is to time-tag a reference marker (e.g., zero-crossing or sync edge of ) on an auxiliary channel to compensate for long-term drift.

In the following Evaluation section, we quantify reconstruction quality using root mean square error (RMSE) and, where applicable, signal-to-noise-and-distortion ratio (SNDR) and effective number of bits (ENOB), while also reporting the corresponding event-rate statistics to make the trade-offs explicit.

3. Hardware Implementation

3.1. Experimental Setup

The block diagram of the experiment setup is shown in

Figure 5. The Keysight (Colorado Springs, CO, USA) M8195A arbitrary waveform generator (AWG), which has a sampling rate of 65

and 25

bandwidth, was used for the generation of the signal of interest, henceforth called the “test waveform”, and the reference signal called “sampling waveform”. Both waveforms were sent to the appropriate inputs of the custom-built level detector through broadband bias tees, allowing for the precise setting of the direct current (DC) offset between the two waveforms.

3.2. Comparator and Level Detector

The level detector is built based on a Texas Instruments (Dallas, TX, USA) TLV3801 comparator, which has a maximum toggle frequency of 3 . The rise and fall times of the chosen comparators’ outputs are 135 , which enables the precise localization in time of the instant when the waveform crossing occurred. This comparator is used to compare the waveforms present on the “signal” and “threshold” inputs of the level detector. The level detector outputs a high voltage on the “rising edge” output when the signal waveform voltage exceeds the sampling waveform voltage. Conversely, the level detector outputs a high voltage on the “falling edge” output when the test signal waveform voltage falls below the sampling waveform voltage. Therefore, the rising edges of the level detector’s outputs represent the upward and downward crossing instants of the signal waveform and sampling waveform.

The rising edge output of the level detector was connected to the channel Ch3 of the time tagger (TT), described in

Section 3.3, and the falling edge output was connected to the channel Ch4. Additionally, the Tektronix (Beaverton, OR, USA) MSO 5204B mixed signal oscilloscope (MSO) was used for waveform monitoring. The signal waveform after the bias tee was connected to the channel Ch1 of the MSO and the sampling waveform to channel Ch2. Channels Ch3 and Ch4 of the MSO were used to monitor the output signals of the level detector, as shown in the diagram in

Figure 5.

3.3. Time-to-Digital Conversion

The time tagger used in the experiment has four input event channels and a tunable voltage threshold scheme to allow either low-voltage transistor–transistor logic (LVTTL) or nuclear instrumentation module (NIM) signaling. The dead time across event channels is 20 , resulting in a maximum event rate of 50 Meps in continuous mode using USB 3.1. The single-shot root mean square (RMS) precision is 30 for each event channel. The time tagger can be synchronized with an external reference via either a 10 or a 1PPS input.

The time interpolator technology is based on ScioSense’s (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) GPX2 TDC integrated circuit (IC), as seen in

Figure 6. Two GPX2 ICs are synchronized together with a common reference. A specific high-performance mode is utilized on each GPX chip, enabling events from one input channel to be measured by a pair of GPX channels (1-3 and 2-4). Using two GPX2 chips in high-performance mode enables achieving a 30

single-shot RMS resolution for each event channel.

Before performing measurements, the time tagger enters a calibration mode, where the channel delays are computed and stored in the memory. It is also possible to adjust the delay manually for each event channel. The paths are calibrated all the way up to the input signal relays, which allow for two signal options: a signal from an external source or an internal signal generated by the phase-locked loop (PLL).

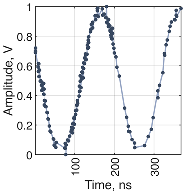

3.4. Waveforms Used in the Experiment

Several different signal and sampling waveforms were employed in the experiments to investigate the system’s performance under various scenarios. Three types of sampling waveforms were selected—triangle, sawtooth, and sine wave, each being generated with the amplitude of 1 and frequencies of 0.354 , 0.707 , 1.59 , and 3.09 . The amplitude of the test waveform, which was a sawtooth, sine wave, damped sine, and frequency modulated (FM) chirp, was 0.8 and frequency 5 . The frequencies were chosen so that the frequency of the test waveform and the sampling waveform do not share a common rational multiple. The amplitude of the sampling waveform exceeded the amplitude of the test waveform so that all possible crossing points could be included in the time tags, as well as some time interval when the sampling waveform fully exceeds or falls short of the signal waveform.

An MSO capture of the test and sampling waveforms, as well as the level detector output waveforms for the case when the signal waveform is a sawtooth with a frequency of 5

and the sampling waveform is a triangle with a frequency of 1.59

, can be seen in

Figure 7.

4. Experimental Results

Different simple and sophisticated waveforms were chosen as test signals for detection using triangle, sawtooth, and/or sine sampling waveforms at four frequencies f1-4 = [0.354, 0.707, 1.59, 3.09] . In post-processing, after time tag acquisition, the decoding algorithm was applied to reconstruct the test signal, which is quantitatively analyzed in the Subsections below, along with visualization of the first 200 time tags.

4.1. Simple Periodic Waveforms

Table 1 and

Table 2 summarize the relative reconstruction RMSE obtained for a 5

sawtooth and 5

sine test signal, respectively. The RMSE in

, denoted as “Err”, is calculated by the Formula (

3):

where

is the pure value of the test signal at time

and

is the value of the reconstructed waveform at time

. The test waveform amplitude was approximately 20% lower than the sampling waveform amplitude so that the sampling waveform’s peaks are above the test signal’s amplitude.

For both test waveform cases, the triangular sampling waveform consistently produced the lowest reconstruction error. This indicates superior uniformity in the distribution of crossing points compared with other waveforms. At moderate sampling frequencies , the RMSE minimum of 0.031 was observed for the sine test signal, confirming that the sampling accuracy benefits from denser yet still well-distributed crossings. On the other hand, sawtooth-type sampling waveforms resulted in higher and less stable errors, which may be attributed to their asymmetric slope behavior, which produces non-uniform time intervals between crossings. The RMSE tended to increase slightly with sampling waveform frequency, particularly for a sine wave, as the ratio between the test signal and the sampling waveform’s periods approached incommensurate values.

4.2. Impact of Using Rising vs. Falling Edges

As the level detector registers events on both rising and falling edges, as previously described in

Section 3.1, it is possible to acquire time tags for both edges separately in a single experiment. The sawtooth test signal was sampled by a triangle signal of four frequencies to evaluate the impact on signal detection from the chosen edges. The resulting time tag plots on time-amplitude axes are presented in

Table 3.

Comparing both edges in

Table 3, one can observe that, using data from the falling edge, events from both jump and rising regions of the sawtooth test signal are registered. In contrast, if only rising-edge data is used, there are no points in the jump area of the sawtooth. However, the calculated RMSEs for the falling edge are higher than those for the rising edge for all sampling signal frequencies. Different error rates can be attributed to the points in the jump part of the sawtooth signal, where a small increment in time results in a significant change in amplitude. In the case of rising edge processing, points in this area were not registered, resulting in a lower RMSE. For the sine wave test signal, the quality of the acquisition and RMSE levels were similar for both rising and falling edge registration. The symmetry and smoothness of the sine wave signal can explain this effect.

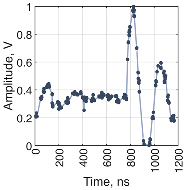

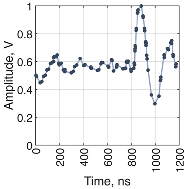

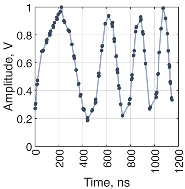

The RMS variation of timing jitter measured across multiple acquisitions remained within 5

, as shown in

Figure 8, showing zoomed regions of the acquired sawtooth test signal. It aligns well with the GPX2 single-shot precision

specified in the datasheet, considering the theoretical relationship

, where

is the single-shot precision RMS of TDC and

,

are slopes of the test signal and sampling function at the crossing point. Overall, the system demonstrates robust synchronization between rising and falling edge detection, allowing both outputs to be reliably used for bidirectional waveform reconstruction.

4.3. Non-Stationary Waveforms

Further system performance assessment was conducted using non-stationary signals. Specifically, for sophisticated waveforms, damped sine and FM chirp waveforms were chosen. The amplitude or frequency of these waveforms varies with time. Similar to the decoding of simple waveforms, these sophisticated waveforms were decoded using the same algorithm and plotted on a time-amplitude axis. Both waveforms were sampled by triangle and sawtooth sampling signals of frequency

f. Results of the damped sine test signal are shown in

Table 4, and the FM chirp signal’s results are shown in

Table 5.

The recorded waveforms and preliminary analyses confirm successful event tagging across the full dynamic range of the tested sophisticated waveforms. For the FM chirp case, the reconstructed waveforms maintained phase continuity throughout the frequency sweep, indicating that the capability of the time-tagging architecture to handle rapidly changing crossing densities is valid.

4.4. Error Analysis

As can be observed from

Table 1, the reconstruction RMSE of a 5

sawtooth test waveform when sampled with a triangle sampling waveform stays consistent at sampling waveform frequencies of 0.354

, 0.707

, and 1.590

and decreases slightly at 3.090

. For the case when the sampling waveform is a sawtooth wave, the reconstruction RMSE increases with the sampling waveform frequency. For the case of a sine wave as the sampling waveform, the reconstruction RMSE decreases with the frequency of the sampling waveform.

As for the case reported in

Table 2, when a triangle sampling waveform samples the 5

sine wave test waveform, the reconstruction RMSE stays relatively constant regardless of the frequency of the sampling waveform. In the case when a sawtooth sampling waveform samples the waveform above, the reconstruction RMSE increases with the sampling waveform frequency, which is the opposite behavior from the one reported in

Table 1 when the roles of the signals were reversed. In the case when the sampling waveform is a sine wave, no discernible trend can be observed when considering the frequency of the sampling waveform.

The reported behavior can be explained by the relative slope between the test and sampling waveforms at the point of crossing. As the relative slope decreases, the actual instant of crossing becomes harder to discern. Due to the additive noise in both the test and sampling waveforms being present in the system, the time instant when the comparator detects a crossing can be slightly shifted from the actual crossing, therefore leading to an increased signal reconstruction RMSE. In the case of a sawtooth and sine wave as test and sampling waveforms, this effect is especially noticeable, with the RMSE being minimal when the relative slope between the waveforms is at its maximum.

Additionally, a shallow relative slope leads to increased bouncing, i.e., rapid switching of the comparator’s output signals, as the time interval where the additive noise may cause the test waveform to exceed or fall below the sampling waveform increases. Bouncing noise can be mitigated by implementing de-bouncing circuitry in the level detector’s front end or by eliminating such false time tags in software; however, this approach may not be feasible in the case of rapidly varying test waveforms.

5. Discussion

5.1. Comparison with Other Level-Crossing ADCs

To clarify the architectural differences between classical LC-ADCs and the presented reference waveform crossing with the TDC-based approach,

Table 6 summarizes the main characteristics of three representative families: (i) DAC-based floating-window LC-ADCs, (ii) fixed-window LC-ADCs without DACs, and (iii) the proposed passive reference-crossing architecture combined with multi-channel time-to-digital conversion. The comparison highlights how traditional LC-ADCs rely on multi-level reference generation and per-event DAC updates, which fundamentally limit their bandwidth, scalability, and power efficiency. Fixed-window approaches reduce complexity by removing the DAC but remain constrained by comparator reset timing and are typically optimized for low-frequency biomedical signals. In contrast, the proposed method eliminates DAC settling and shifts amplitude encoding into the time domain, where the reference slope and TDC jitter govern precision. Simplicity of the approach enables the architecture to scale efficiently across multiple channels, maintain uniform timing accuracy, and achieve effective bandwidths in the hundreds-of-MHz to GHz range when combined with stroboscopic sampling. The table emphasizes these distinctions across functionality, performance, scalability, and application scope.

Table 7 compares quantitative characteristics of the proposed digitizer with similar solutions based on waveform crossing. Resolution/linearity is quantified using the SNDR of a 5

sine test waveform with normalized amplitude 1

and different sampling functions. SNDR is calculated using Equation (

4):

where

is RMSE calculated using (

3).

5.2. Limitations

Experimental validation and comparison with other LC-ADC technologies in

Table 6 have shown that the proposed waveform-crossing ADC (WC-ADC) method mainly suffers from limitations imposed by the rate and precision of TDC and the selection of reference waveform.

TDC rate is determined by the “dead time” of a particular TDC. The ScioSense GPX2 TDC [

18] chip used in the time tagger provides a dead time of approximately 5

per chip in 2-channel mode. Conversely, the time between two rising edges must be at least 5

, and in the case of a “smooth” waveform, the bandwidth is about 200

.

TDC precision is determined by a single-shot RMS value of a particular TDC. In the case of the ScioSense GPX2 TDC [

18], single-shot RMS

is around 30

, which means that edges of acquired signals will be smeared by approximately

, i.e., 0.18

. The hardware implementation in

Section 3 has shown that the real edge jitter is significantly higher—around 2

in the jump part of the sawtooth

and about 10

in the rising part of the sawtooth

(see

Figure 8). As has been mentioned in

Section 2, the precision of the acquisition strongly depends on the difference of slopes between

—signal of interest and

—reference waveform. The difference in slopes strongly affects the stability of threshold operation and immunity to external noises. Finally, the hardware implementation of the comparator circuit itself is crucial to the low-noise, bounce-free operation of the proposed WC-ADC.

TDC clock accuracy affects the long-term stability of the WC-ADC, as it can lead to the “slipping” of samples along the sampling waveform, thereby distorting the reconstruction of the measured signal. In the case of a constant slope sampling waveform, it results in stretching or compression of the acquired signal.

Reference waveform

strongly affects accuracy and bandwidth of the acquisition. As mentioned in

Section 2.2, a sampling function with a constant slope is recommended, since it provides an even distribution of errors across the whole amplitude range.

Control of the sampling function phase is critical to the correct functioning of WC-ADC. A mechanism for synchronizing the time base of the TT with the exact phase of the sampling function is necessary to ensure proper reconstruction of the signal. In our experiments, we employed an additional TT channel for controlling the phase of the sampling waveform.

The frequency of the sampling waveform affects the density of the acquired time tags and the detection of features in the signal of interest . High frequency allows a more detailed acquisition of at the expense of an increased rate of events and additional noise. On the other hand, if is quasi-periodic, stroboscopic sampling of with a lower frequency can be employed. Nevertheless, in the case of periodic and , it is essential to avoid frequency locking effects due to commensurate frequencies.

5.3. Future Work

Future work will focus on extending the proposed architecture towards a higher bandwidth, improved resolution, and enhanced adaptability of the sampling process. First, employing reference waveforms in the GHz range—either generated electronically or derived from photonic sources—would enable direct event-based acquisition of RF and millimeter-wave signals without relying solely on stroboscopic undersampling. Second, integrating multi-threshold sampling would allow for the simultaneous extraction of signal slope and curvature information, thereby enhancing reconstruction robustness in rapidly changing conditions. On the digital side, real-time field-programmable gate array (FPGA)-based reconstruction remains an essential step toward deployable systems, enabling continuous interpolation, denoising, and parameter estimation directly in hardware. To further enhance timing precision, replacing the current TDC with a Wave-Union TDC [

19] would permit an effective resolution of sub-10 ps and zero dead time, thereby increasing the achievable dynamic range for steep reference slopes and bandwidth of ADC. Another promising direction is to explore compressive or information-optimal sampling, for example, using randomized or nonuniform reference waveforms inspired by the deliberate randomization frameworks of Bilinskis et al. [

16]. Finally, the use of chaotic [

20] sampling functions may further enhance decorrelation, mitigate spectral leakage, and expand the range of alias-free acquisition scenarios, thereby opening up new possibilities for adaptive sensing in cluttered or interference-rich environments.

6. Conclusions

This work presents an experimental investigation of an analog-to-digital conversion method based on reference waveform crossings, combined with a high-resolution TDC. The WC-ADC approach relies on comparing an incoming analog signal to a periodic reference waveform without requiring any active adjustment or feedback and on converting each crossing event into a precise timestamp using a multi-channel TDC. A ScioSense GPX2 TDC-based time-tagger was employed to record crossing events with nanosecond-level timing precision.

Several representative input signals—5 sawtooth, sine wave, FM chirp, and damped sine bursts—were acquired using triangular, sawtooth, and sinusoidal sampling waveforms. In addition, stroboscopic sampling was demonstrated in scenarios where the reference frequency was lower than the input signal frequency, highlighting the potential for effective RF undersampling using only passive reference generation.

The primary advantage of the method is that it relies exclusively on passive comparison, eliminating the need for level-updating DACs or closed-loop reference tracking that typically limit bandwidth in conventional LC-ADCs. As a result, the system retains high bandwidth potential while maintaining a simple, scalable analog front end.

Experimental results confirm that the proposed technique can accurately acquire waveforms with effective bandwidths approaching 100 , despite using relatively low-frequency references (0.354–3.09 ). The measured RMSE ranged from 0.05 to 0.3 for sinusoidal inputs and 0.15 to 0.4 for sawtooth inputs, depending on the chosen reference and local slope of the input. The timing jitter exhibited strong dependence on the relative gradient of the acquired waveform: in steep regions, the error remained within 5 , while in the low-slope areas it increased to approximately 20 , consistent with the theoretical relationship , where is single-shot precision RMS of TDC and , are slopes of the test signal and sampling function at the crossing point.

From these observations, it can be concluded that the passive crossing technique is particularly well-suited for sparse, wideband, and rapidly varying signals, where high slopes dominate, and timing uncertainty remains minimal. Furthermore, the method is inherently scalable: the same reference waveform may be broadcast to many channels, while TDC channel scaling is straightforward and does not require duplication of DACs or multi-level analog thresholds. Potential application domains include biomedical signal processing, scientific instrumentation, RF signal acquisition, UWB radar, integrated sensing and communication (ISAC), and multi-channel timed antenna arrays. The demonstrated results suggest that the method offers a promising path toward compact, high-bandwidth, multi-channel, event-based ADCs capable of operating at frequencies far beyond the limits of traditional level-crossing and Nyquist converters.

The proposed architecture was validated using commercial discrete devices, which allowed for the demonstration of the core operating principles before committing to more resource-intensive implementations. Although this work’s current focus is not on application-specific integrated circuit (ASIC) development, the design approach aligns well with established complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) TDC implementations that have been successfully realized in 65

[

21], 130

[

22], and 180

[

23] processes. The discrete components were prioritized for this work primarily because they enable faster iteration and easier debugging during the early design phase (which is difficult once a design is committed to silicon).

For practical deployment, FPGA platforms for signal reconstruction remain the near-term target due to their flexibility and reasonable development timelines. That said, the experimental results presented here provide a solid foundation for potential ASIC migration, where lower power consumption and tighter timing resolution could be achieved. Therefore, this may be considered a natural progression for future work once the architecture has been further refined.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A.; methodology, S.M.; software, N.T., J.R., R.B., and V.K.; validation, A.A.; formal analysis, A.A.; investigation, S.M., N.T., J.R., and R.B.; resources, A.A. and V.K.; data curation, N.T. and J.R.; writing—original draft preparation, A.A., S.M., N.T., and J.R.; writing—review and editing, A.A., S.M., and N.T.; visualization, N.T.; supervision, A.A.; project administration, A.A.; funding acquisition, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Riga Technical University Science grant No. RTU-ZG-2024-1-0016, under the EU RRF project No. 5.2.1.1.i.0/2/24/I/CFLA/003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors J.R. and V.K. were employed by the company Eventech Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ADC | analog-to-digital converter |

| ASIC | application-specific integrated circuit |

| AWG | arbitrary waveform generator |

| CMOS | complementary metal–oxide–semiconductor |

| DAC | digital-to-analog converter |

| DC | direct current |

| EEG | electroencephalogram |

| ENOB | effective number of bits |

| FM | frequency modulated |

| FPGA | field-programmable gate array |

| IC | integrated circuit |

| ISAC | integrated sensing and communication |

| LC-ADC | level-crossing ADC |

| LVTTL | low-voltage transistor–transistor logic |

| MSO | mixed signal oscilloscope |

| NIM | nuclear instrumentation module |

| PLL | phase-locked loop |

| RF | radio frequency |

| RMS | root mean square |

| RMSE | root mean square error |

| SNDR | signal-to-noise-and-distortion ratio |

| TDC | time-to-digital converter |

| TT | time tagger |

| UWB | ultra-wideband |

| WC-ADC | waveform-crossing ADC |

| WSN | wireless sensor network |

References

- Karrari, H. Analog-to-Digital Converters for High-Speed Applications. Ph.D. Thesis, Lund University, Lund, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Dorrer, S.; Werzi, A.; Moser, B.A.; Lunglmayr, M.; Pretl, H. Event-Based ADCs vs. Nyquist ADCs: Rethinking Performance Metrics. In Proceedings of the 2025 Austrochip Workshop on Microelectronics (Austrochip), Linz, Austria, 24–25 September 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlili, M.; Ben-Romdhane, M.; Maalej, A.; Rivet, F.; Dallet, D.; Rebai, C. Level-crossing ADC design and evaluation methodology for normal and pathological electrocardiogram signals measurement. Meas. J. Int. Meas. Confed. 2018, 124, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allier, E.; Sicard, G.; Fesquet, L.; Renaudin, M. Asynchronous ADCs: Design methodology and case study. In Proceedings of the 8th International Workshop on ADC Modelling and Testing, IWADC 2003, Perugia, Italy, 8–10 September 2003; International Measurement Confederation (IMEKO): Budapest, Hungary, 2003; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Szyduczyński, J.; Kościelnik, D.; Miśkowicz, M. Time-to-digital conversion techniques: A survey of recent developments. Measurement 2023, 214, 112762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akopyan, F.; Manohar, R.; Apsel, A.B. A level-crossing flash asynchronous analog-to-digital converter. In Proceedings of the 12th IEEE International Symposium on Asynchronous Circuits and Systems (ASYNC’06), Grenoble, France, 13–15 March 2006; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2006; Volume 2006, pp. 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faghani, M.; Rezaee-Dehsorkh, H.; Ravanshad, N.; Aminzadeh, H. Ultra-Low-Power Voice Activity Detection System Using Level-Crossing Sampling. Electronics 2023, 12, 795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delagnes, E.; Breton, D.; Lugiez, F.; Rahmanifard, R. A Low Power Multi-Channel Single Ramp ADC with up to 3.2 GHz Virtual Clock. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2007, 54, 1735–1742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusayasu, T. A fast integrating ADC using precise time-to-digital conversion. In Proceedings of the IEEE Nuclear Science Symposium Conference Record, Honolulu, HI, USA, 26 October–3 November 2007; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 302–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilinskis, I.; Skageris, A. Experimental studies of signal digitizing based on sine-wave reference crossings. Elektron. Elektrotechnika 2010, 100, 69–72. [Google Scholar]

- Barkans, R.; Migla, S.; Tihomorskis, N.; Ratners, J.; Aboltins, A. High-Resolution Sampling of UWB Radar Echoes Using Waveform Crossing and TDC Techniques. In Proceedings of the 2025 Photonics and Electromagnetics Research Symposium, PIERS 2025, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 4–8 May 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Bilinskis, I.; Boole, E.; Sudars, K. Combination of periodic and alias-free non-uniform signal sampling for wideband signal digitizing and compressed transmitting based on picosecond-resolution event timing. In Proceedings of the 2017 Signal Processing Symposium (SPSympo), Jachranka, Poland, 12–14 September 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilinskis, I.; Boole, E.; Skageris, A. Method for transmission of wide bandwidth signals based on event timing and deliberate randomization of signal sampling. In Proceedings of the 2017 Advances in Wireless and Optical Communications, RTUWO 2017, Riga, Latvia, 2–3 November 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 152–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Osman, A.; Kim, D.; Goldstein, B.; Huang, C.; Martini, B.; Pieribone, V.A.; Culurciello, E. Continuous time level crossing sampling ADC for bio-potential recording systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2013, 60, 1407–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Naraghi, S.; Courcy, M.; Flynn, M.P. A 9b 14μW 0.06mm2 PPM ADC in 90nm Digital CMOS. In Proceedings of the Digest of Technical Papers—IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference, Francisco, CA, USA, 8–12 February 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 168–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilinskis, I.; Boole, E.; Skageris, A. Discrete Fourier Transform of event timing signals transmitted over optical lines. In Proceedings of the 2016 Advances in Wireless and Optical Communications, RTUWO 2016, Riga, Latvia, 3–5 October 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 28–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudars, K.; Bilinskis, I.; Boole, E.; Vedin, V. Signal Analog-to-Event-to-Digital converting based on periodic sampling and precise event timing. In Proceedings of the 25th International Conference Radioelektronika, RADIOELEKTRONIKA 2015, Pardubice, Czech Republic, 21–22 April 2015; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 133–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ScioSense, B.V. TDC-GPX2 Time-to-Digital Converter. Available online: https://www.sciosense.com/tdc-gpx2-time-to-digital-converter/ (accessed on 4 August 2025).

- Ratners, J.; Goczkowski, J.; Wojcikowski, M.; Aboltins, A. The Analysis of Time Delays Stability in an FPGA-based Wave-Union Time-to-Digital Converter Core. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 12th Workshop on Advances in Information, Electronic and Electrical Engineering, AIEEE 2025, Vilnius, Lithuania, 15–17 May 2025; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haliuk, S.; Vovchuk, D.; Spinazzola, E.; Secco, J.; Bobrovs, V.; Corinto, F. A Deterministic Chaos-Model-Based Gaussian Noise Generator. Electronics 2024, 13, 1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurgo, M.; Navickas, R. Comparison of TDC parameters in 65 nm and 0.13 μm CMOS. In Proceedings of the 5th IEEE Workshop on Advances in Information, Electronic and Electrical Engineering, AIEEE 2017, Riga, Latvia, 24–25 November 2017; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veerappan, C.; Richardson, J.; Walker, R.; Li, D.U.; Fishburn, M.W.; Stoppa, D.; Borghetti, F.; Maruyama, Y.; Gersbach, M.; Henderson, R.K.; et al. Characterization of large-scale non-uniformities in a 20k TDC/SPAD array integrated in a 130nm CMOS process. In Proceedings of the European Solid-State Device Research Conference, Helsinki, Finland, 12–16 September 2011; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2011; pp. 331–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaniappan, A.R.; Siek, L. A 0.6 V, 1.74 ps resolution capacitively boosted time-to-digital converter in 180 nm CMOS. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems, Sapporo, Japan, 26–29 May 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Event-driven ADC using multiple thresholds.

Figure 1.

Event-driven ADC using multiple thresholds.

Figure 2.

Principle of analog-to-digital conversion using waveform crossing and TDC.

Figure 2.

Principle of analog-to-digital conversion using waveform crossing and TDC.

Figure 3.

Signals in waveform crossing ADC.

Figure 3.

Signals in waveform crossing ADC.

Figure 4.

Principle of digital-to-analog conversion from waveform crossing time tags.

Figure 4.

Principle of digital-to-analog conversion from waveform crossing time tags.

Figure 5.

Block diagram of the experiment setup.

Figure 5.

Block diagram of the experiment setup.

Figure 6.

Block diagram of the time tagger based on two GPX ICs.

Figure 6.

Block diagram of the time tagger based on two GPX ICs.

Figure 7.

MSO captured output waveforms: (a) test waveform (blue), sampling waveform (red), and (b) level detector rising (green) and falling (purple) edge.

Figure 7.

MSO captured output waveforms: (a) test waveform (blue), sampling waveform (red), and (b) level detector rising (green) and falling (purple) edge.

Figure 8.

Zoomed rising jump parts of the sawtooth test signal acquired with 0.707 MHz triangular sampling function. First 10,000 points were reconstructed from falling edge time tags.

Figure 8.

Zoomed rising jump parts of the sawtooth test signal acquired with 0.707 MHz triangular sampling function. First 10,000 points were reconstructed from falling edge time tags.

Table 1.

Sawtooth test signal sampled by triangle, sawtooth, and sine reference signals at different frequencies f. The first 200 time tags from both rising and falling edges are visualized.

Table 2.

Sine test signal sampled by triangle, sawtooth, and sine sampling signals at different frequencies f. The first 200 time tags from both rising and falling edges are visualized.

Table 3.

Edges’ impact on the detection of sawtooth test signal sampled by triangle sampling signals at different frequencies f. The first 200 time tags from either rising or falling edges are visualized.

Table 4.

Damped sine test signal sampled by triangle and sawtooth sampling signals at different frequencies f. The first 200 time tags from both rising and falling edges are visualized.

Table 5.

FM chirp test signal sampled by triangle and sawtooth sampling signals at different frequencies f. The first 200 time tags from both rising and falling edges are visualized.

Table 6.

Comparison of classical DAC-based level-crossing ADCs, fixed-window LC-ADCs, and the proposed passive reference-crossing ADC architecture using multi-channel TDC timing.

Table 6.

Comparison of classical DAC-based level-crossing ADCs, fixed-window LC-ADCs, and the proposed passive reference-crossing ADC architecture using multi-channel TDC timing.

| Feature | DAC-Based LC-ADC (Floating-Window) [3,4,6] | Fixed-Window LC-ADC (No DAC) [7,14] | Proposed

WC-ADC [2,8,9,15,16,17] |

|---|

| Reference Generation | Multiple reference levels via DACs or resistor/capacitor ladders; updated on each event [3,6] | Single fixed window generated digitally or via subtraction; no multi-bit DAC [14] | No DAC; periodic passive reference waveform (sawtooth [8,9,15] or other [16,17]) |

| Event Formation | Input crossing static quantization levels [4,6] | Event when input exits fixed window [14] | Event when input crosses reference waveform; timing-only representation [2,8,9,15,16,17] |

| Amplitude Encoding | Direct multi-bit from level index [3,6] | Amplitude inferred from sequential window updates [14] | Amplitude reconstructed from event timing and known [2,8,9,15,16,17] |

| Timing Information | Optional or coarse [4] | Limited by comparator/reset-loop delay [14] | High-resolution using multi-channel TDCs (ps-scale) [2,16,17] |

| Speed Limiting Factors | DAC settling, comparator hysteresis, asynchronous logic [3,6] | Comparator delay + buffer reset [14] | Comparator bandwidth + TDC dead time; no DAC latency [2,8,9,15,16] |

| Scalability to Many Channels | Poor: many comparators, DACs, and update logic per channel [3,6] | Moderate: fewer analog blocks but still per-channel reset loops [14] | Excellent: identical comparator channels + shared multi-channel TDC [2,8,9,15,17] |

Power/Area per

Channel | High (DACs + comparator array) [3,6] | Medium (two comparators + fixed window engine) [14] | Low: single comparator + TDC; reference shared [8,9,15,16,17] |

| Achievable Bandwidth | Typically <1–10 MHz [3,6] | <100 kHz for biomedical [7,14] | 100 MHz–GHz effective using stroboscopic sampling [2,16,17] |

SNR/Resolution

Limitation | INL/DNL of DAC and comparator mismatch [3] | Comparator offset, window size K [14] | TDC jitter and reference slope () [2,16] |

| Best Use Cases | Biomedical, audio, low-power sensing [3,7] | Neural/biopotential low-rate acquisition [14] | Biomedical [2,16,17], Nuclear science [9], WSN [15] |

Table 7.

Comparison of quantitative characteristics of given digitizer with similar works.

Table 7.

Comparison of quantitative characteristics of given digitizer with similar works.

| Work | Amplitude Resolution | BW/Rate | Time Resolution | Notes |

|---|

| This work | SNDR 13.6–33.2 dB,

ENOB 1.96–5.22 b | Input BW 200 MHz,

Max rate 50 MSa/s | TDC bin 30 ps,

jitter 5 ns,

dead time 20 ns | SNDR for 5 MHz

sinusoid test signal |

Naraghi et al.

(ISSCC’09) [15] | SNDR ≈ 49 dB,

ENOB 7.9 b;

1.5 LSB;

1.2 LSB | Input BW 300 kHz;

Rate 1 MSa/s | TDC clock 128 MHz;

TDC 5 MSB (coarse) + 4

LSB (fine) | Digital post-processing. |

Delagnes et al.

(TNS’07) [8] | Nom. 12-bit;

INL 1 LSB;

DNL 0.2 LSB p-p | Max rate 746 kSa/s | TDC clock up to

3.2 GHz;

time LSB 312.5 ps;

DLL time nonlin.

∼20 ps rms | |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |