Congestion-Aware Scheduling for Large Fleets of AGVs Using Discrete Event Simulation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. AGV Scheduling for Minimizing Congestion

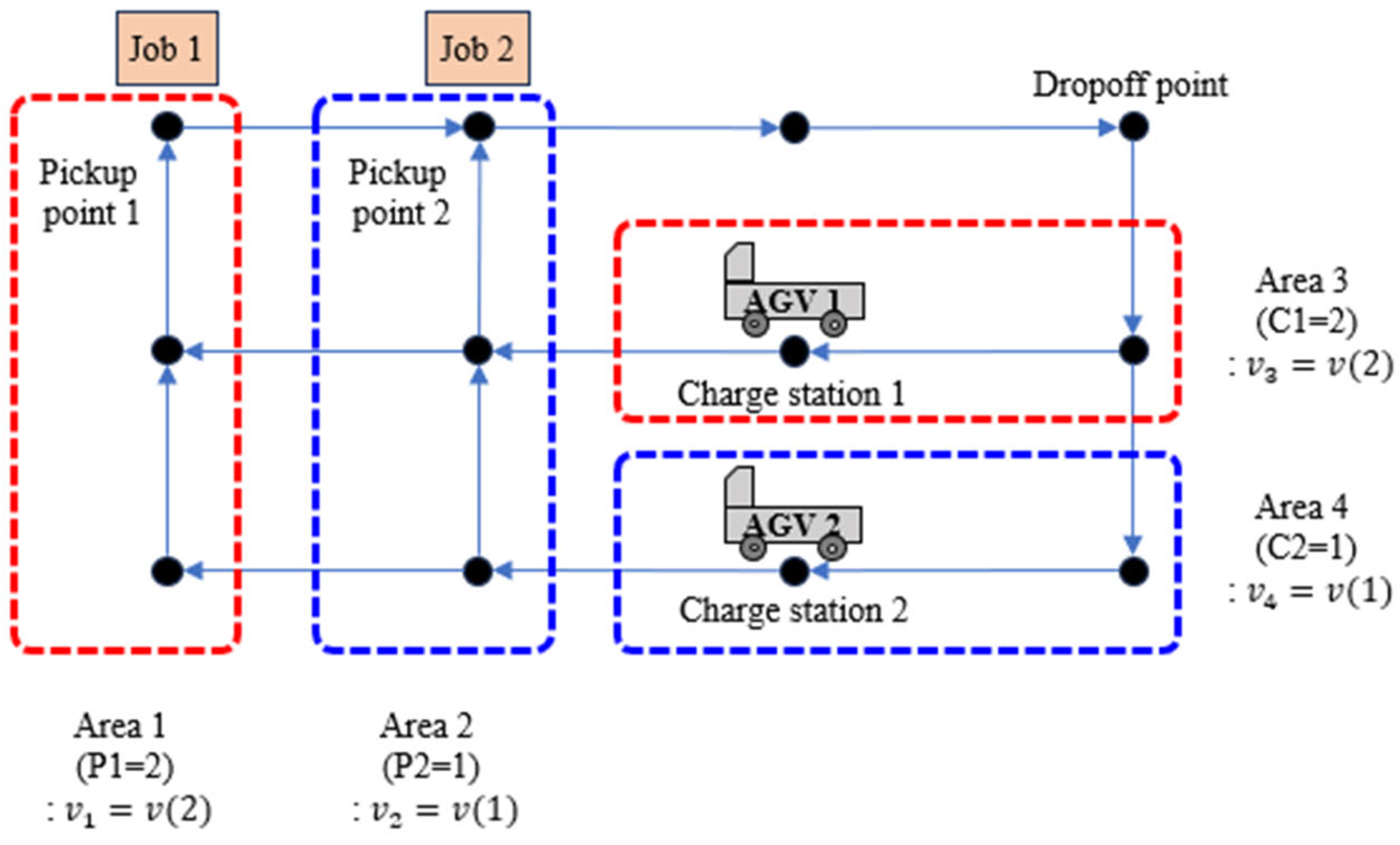

3.1. Congestion Function and Congestion Penalty

3.2. Congestion-Aware Scheduling Rules

4. Experiment Results

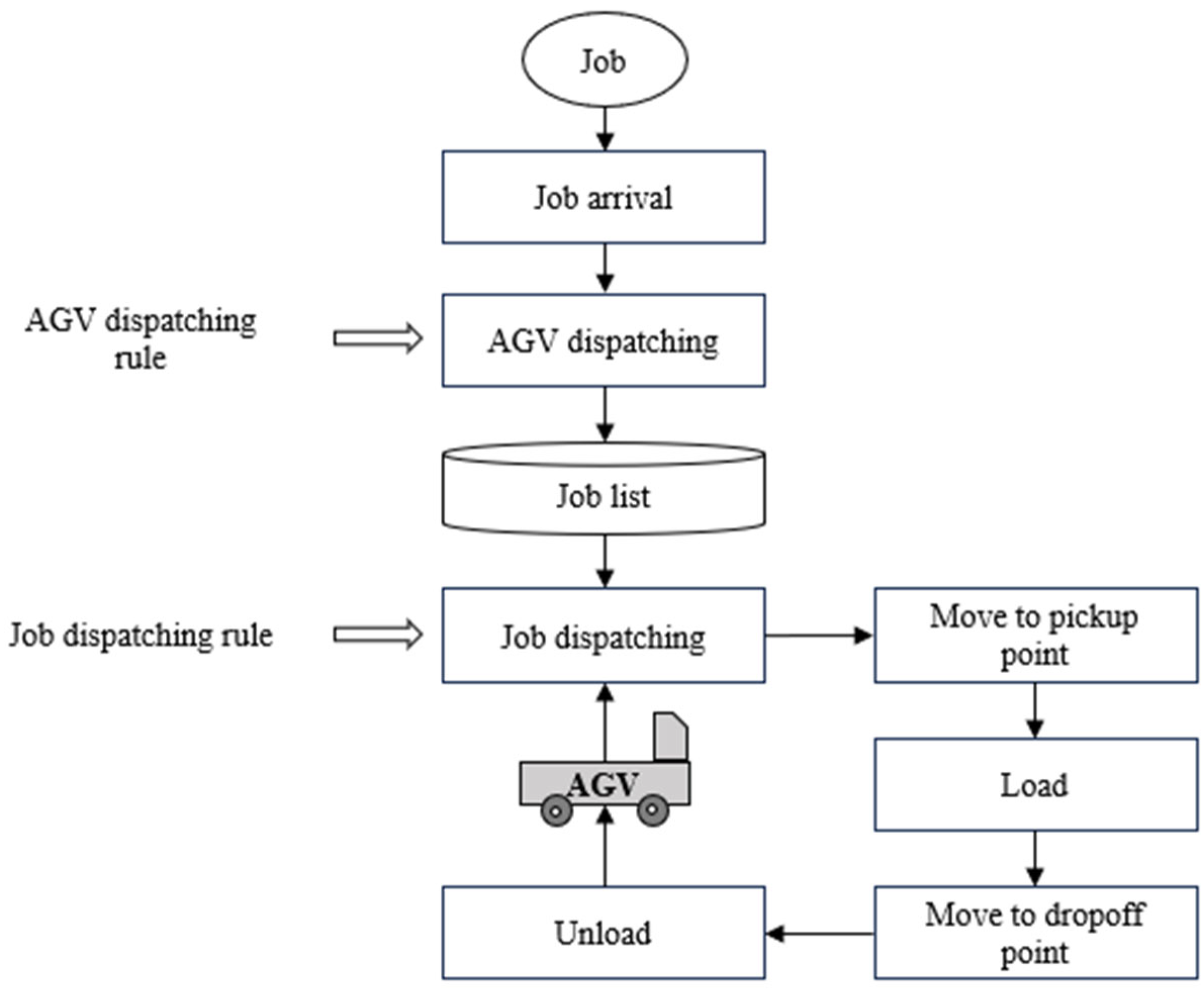

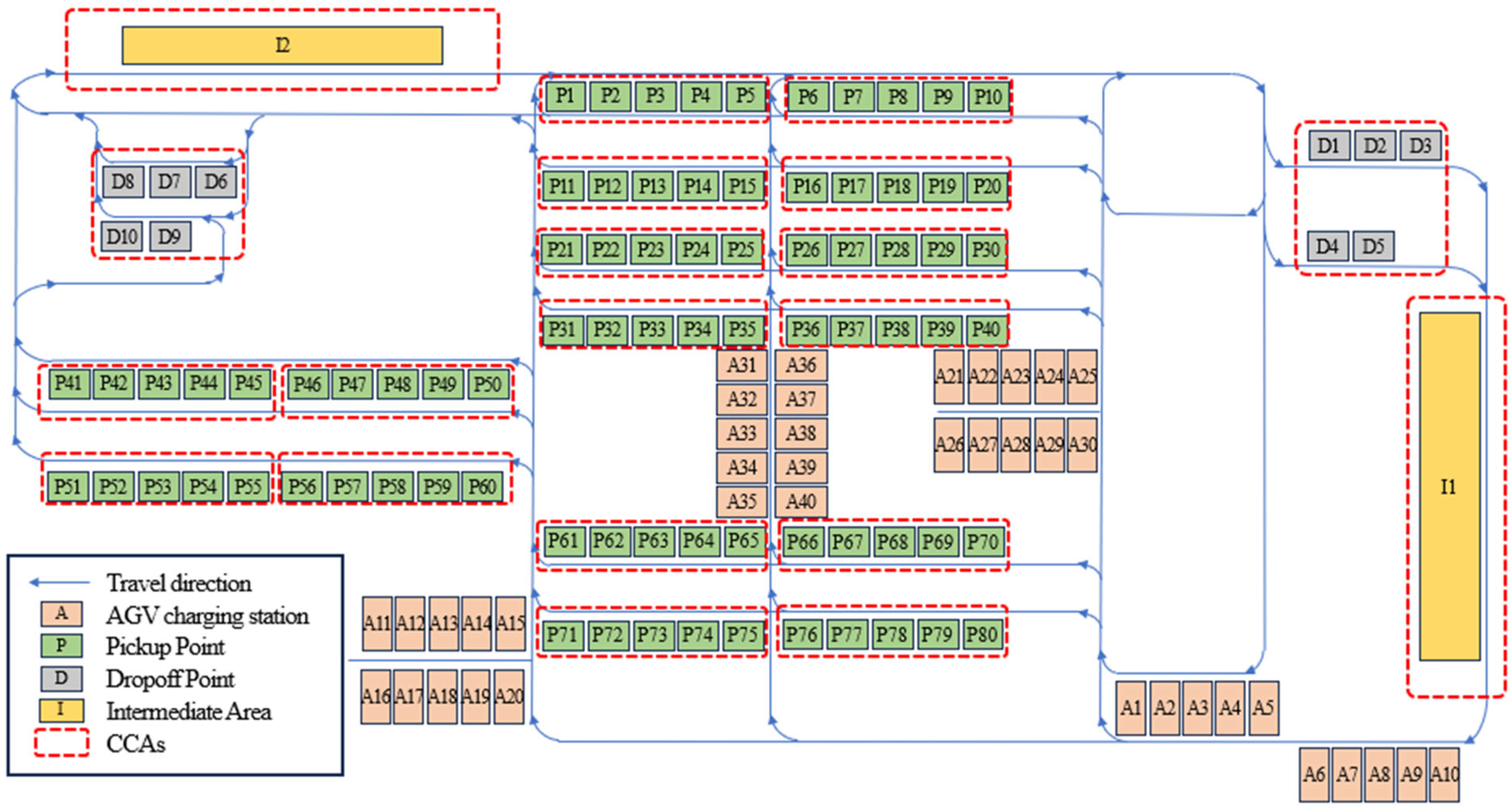

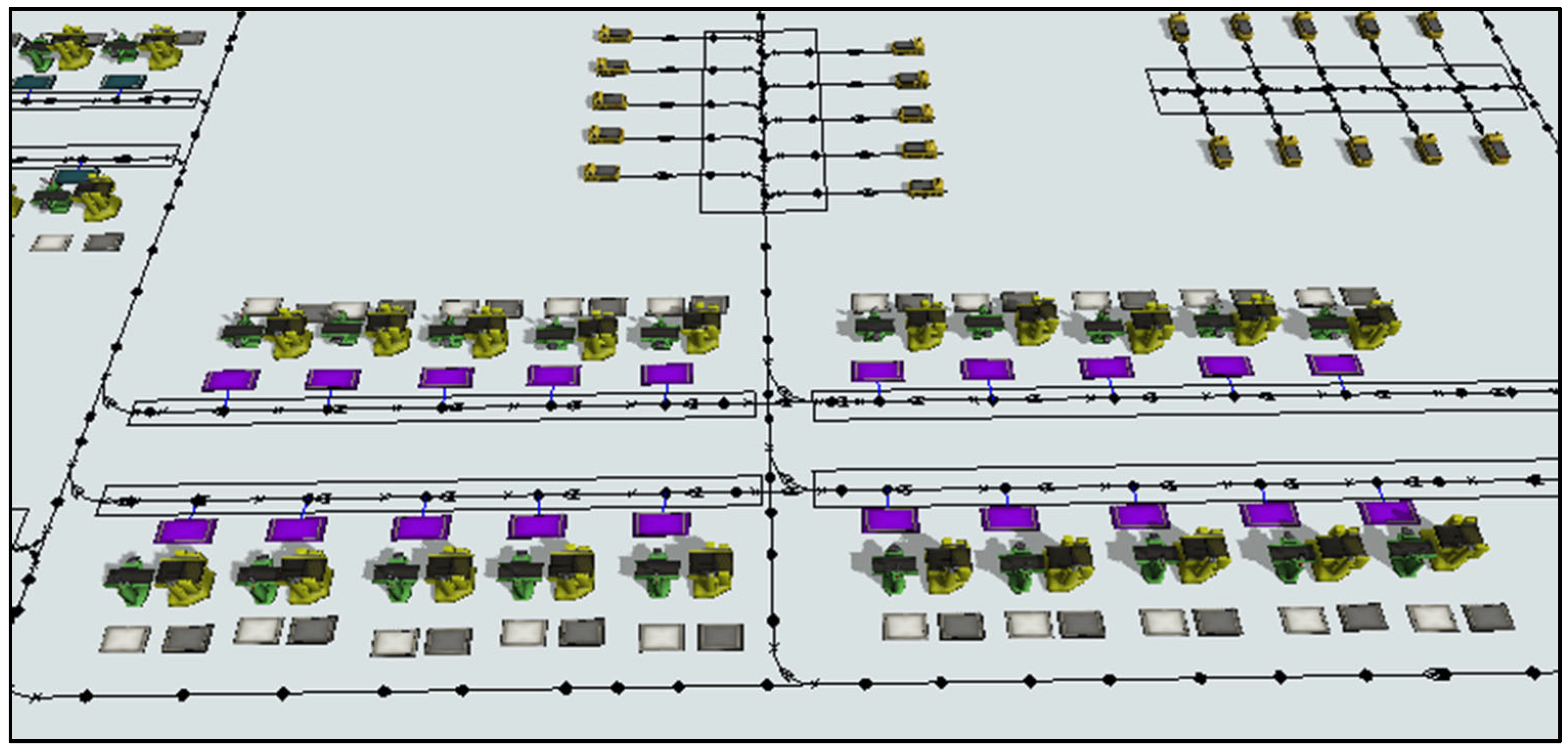

4.1. Simulation Model of AGV Fleet

4.2. Experiment Design

- To validate the performance of the proposed congestion-aware scheduling rules, they are compared against conventional benchmark rules. Specifically, four standard rules—including first in–first out (FIFO) and nearest idle vehicle (NIV)—have been integrated into the job and AGV dispatching frameworks. Consequently, 10 distinct rule sets are employed in this study. Table 5 presents a comprehensive list of job and AGV dispatching rules utilized in the experiment.

- 2.

- The buffer capacity of each pickup point is limited to a maximum of three items to account for actual safety regulations and the spatial constraints of the physical site. The inter-arrival time of a job is classified into three levels: short, normal, and long. The inter-arrival times for each level are uniformly distributed across the range defined by their respective minimum and maximum values (in seconds). The pickup points are grouped into four production lines: Line A (P1–P20), Line B (P21–P40), Line C (P41–P60), and Line D (P61–P80). To simulate dynamic workload changes, the inter-arrival time level of each line is updated every 4 h. The inter-arrival time levels are used to vary congestion levels across pickup areas. For instance, a pickup area serving lines with lower workloads is likely to maintain relatively low congestion. Consequently, the proposed congestion-aware scheduling rules indirectly account for the workload by utilizing congestion information during the scheduling process. Table 6 presents the distribution parameters for the job generation intervals, while Table 7 details the production schedule for each line.

- 3.

- Jobs are classified into 10 distinct types, each assigned to a unique destination (dropoff point). Job types are randomly assigned with equal probability, where type nt jobs are transported to Dnt.

- 4.

- For all job types, the processing time is 300 s, and due dates (di) are uniformly distributed between 2000 and 4000 s. Based on these parameters, the tardiness Ti of an individual item is formulated aswhere denotes the completion time of the item. Consequently, if an item is delivered before its due date , the tardiness is recorded as zero.

- 5.

- Each AGV possesses a unit load capacity, meaning it can transport a maximum of one job at a time. The detailed kinematic and battery parameters are configured to match the hardware specifications of real-world AGVs, as follows:

- A.

- Load/Unload Time: 5 s;

- B.

- Acceleration/Deceleration: 1 m/s2;

- C.

- Battery Capacity: 100 AH (Amp-Hour);

- D.

- Battery Use: 25 Amp;

- E.

- Idle Battery Use: 0.5 Amp;

- F.

- Recharge Threshold: 30 AH;

- G.

- Resume Threshold: 60 AH.

- 6.

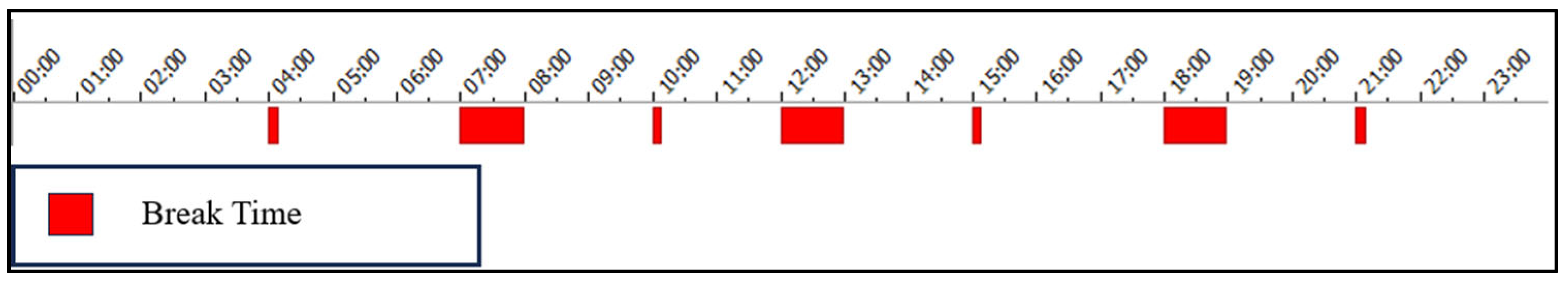

- The simulation model operates on a 24 h cycle. The daily schedule includes a total of six scheduled breaks: three short breaks (10 min each) and three long breaks (1 h each). During these break intervals, the material input to the processors within the production lines is suspended. Consequently, the generation of job items is halted, preventing new loads from arriving at the pickup points. Figure 5 illustrates the 24 h operation timeline and break schedule. We implemented these elements to ensure realistic simulation conditions.

- 7.

- The total simulation horizon is set to 345,600 s, covering a continuous four-day operational period from Monday at 08:00 to Friday at 08:00. The experiment evaluates a total of 100 distinct scenarios, derived from the combination of the Job and AGV dispatching rules defined in Table 5. To ensure statistical reliability against stochastic variability, each scenario is replicated 40 times.

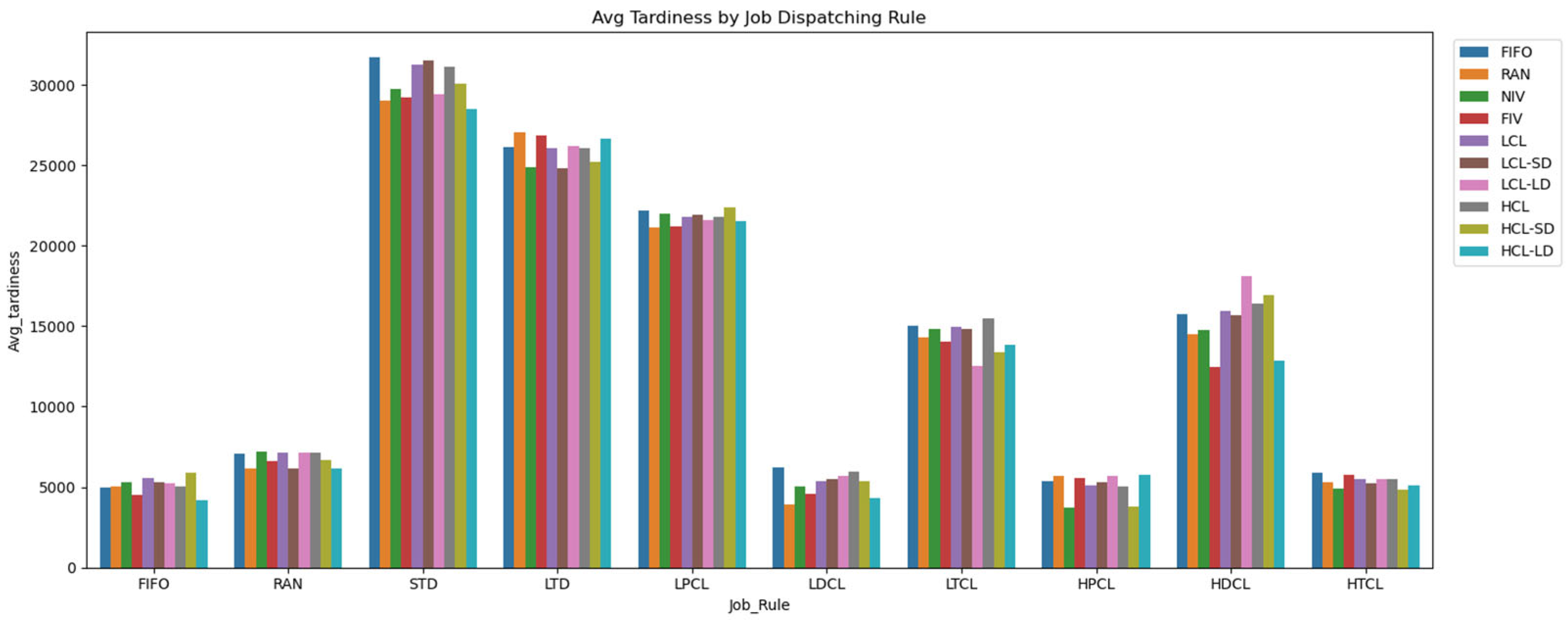

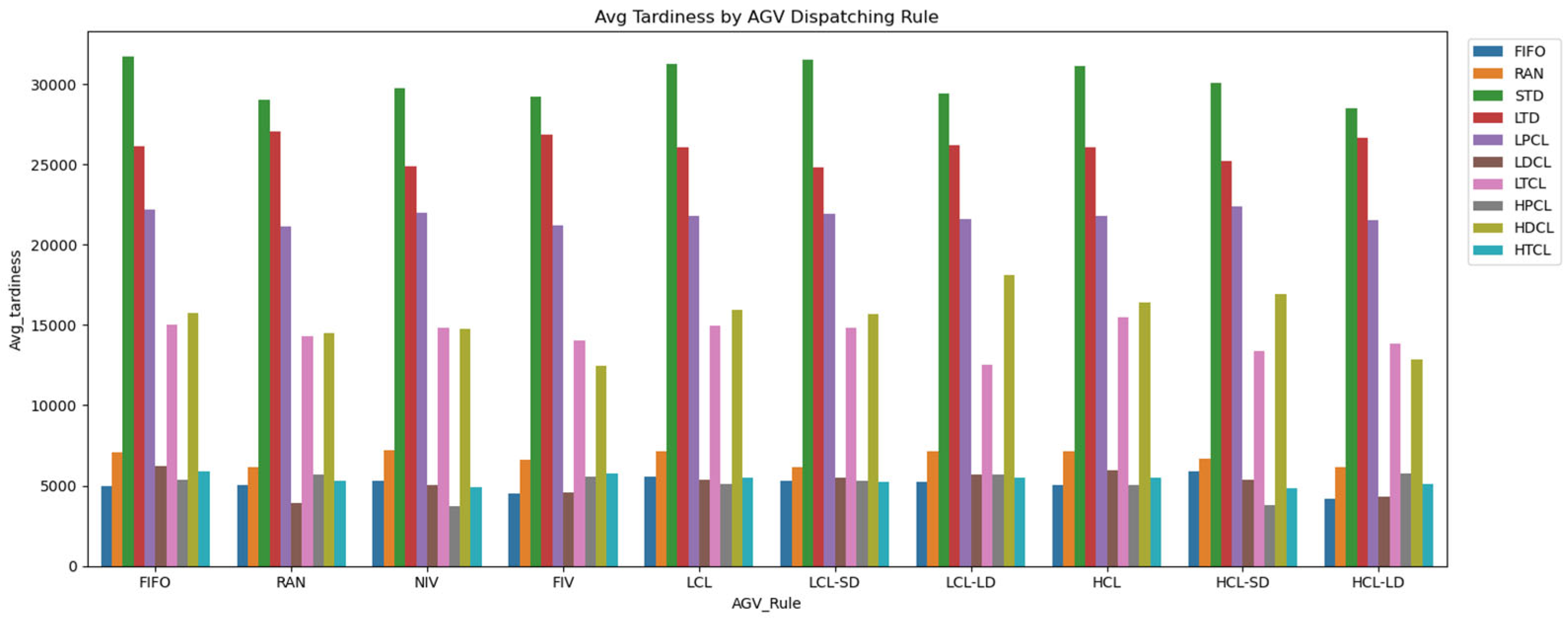

4.3. Experiment Result: Tardiness

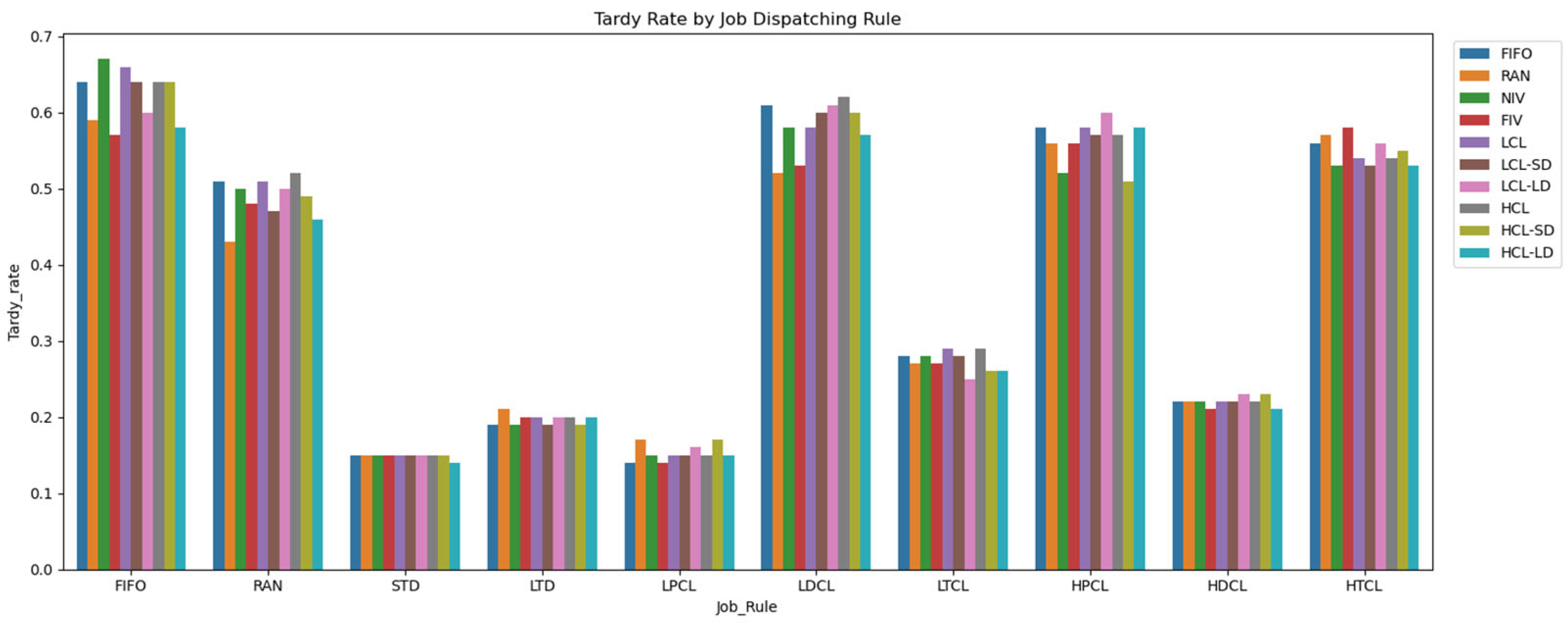

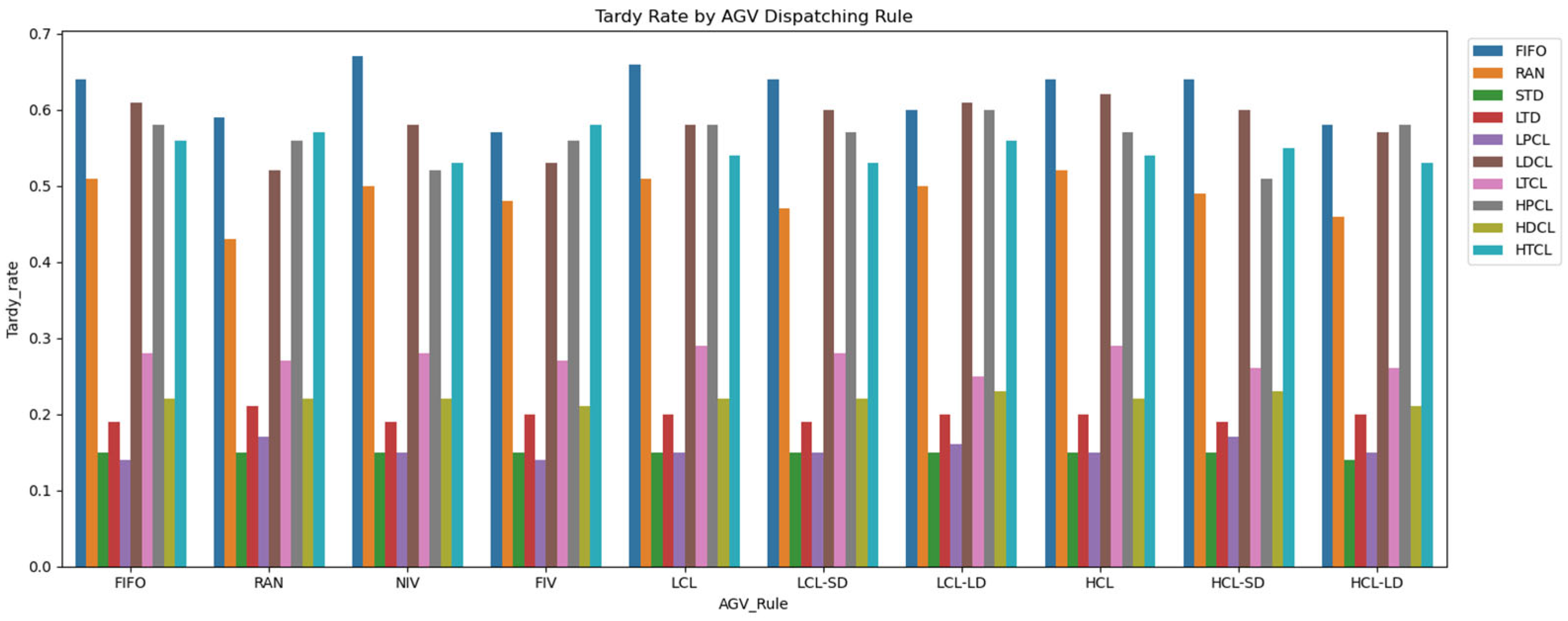

4.4. Experiment Result: Tardy Rate

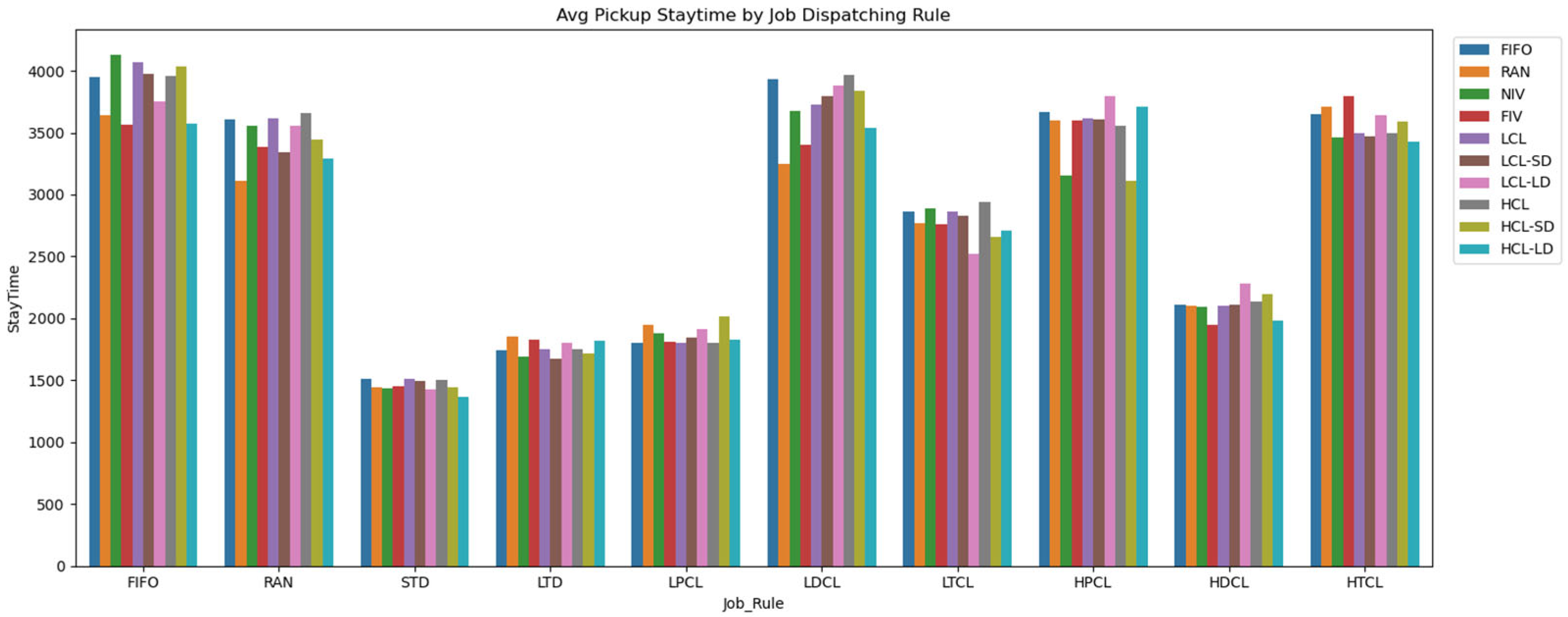

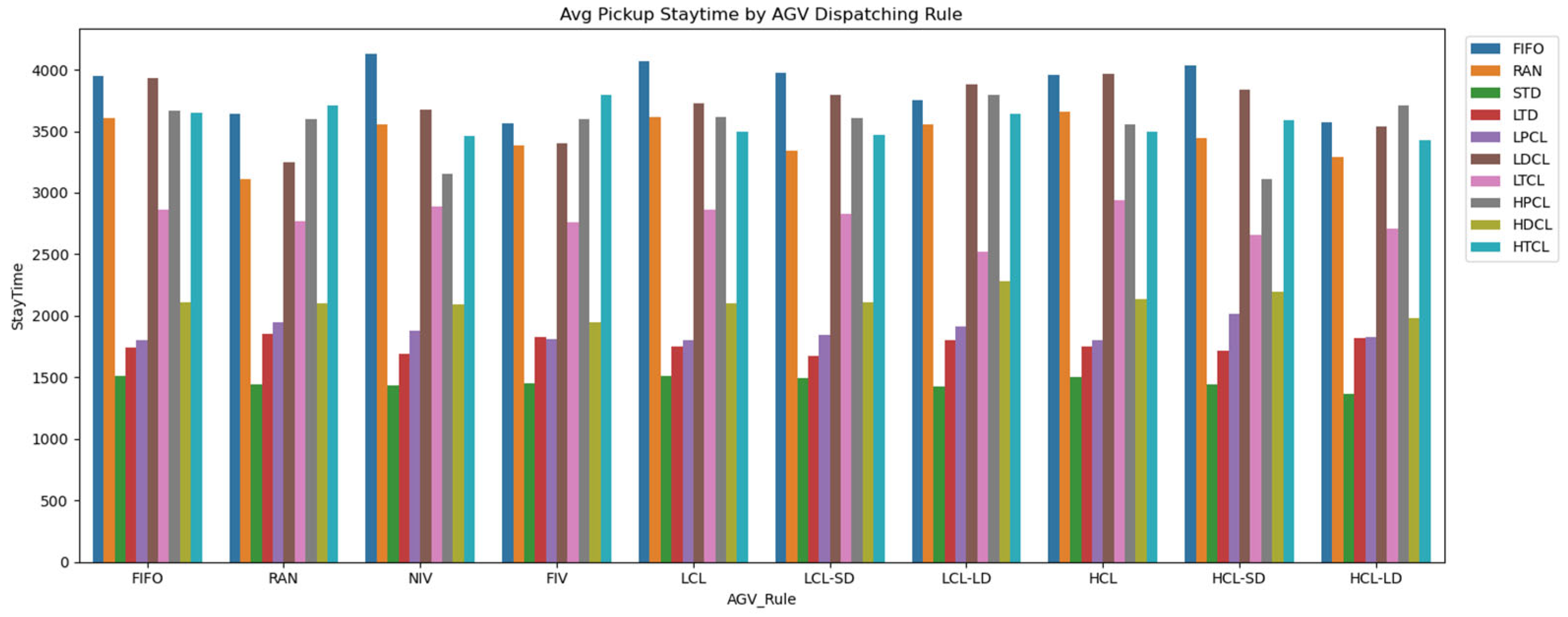

4.5. Experiment Result: Pickup Stay Time

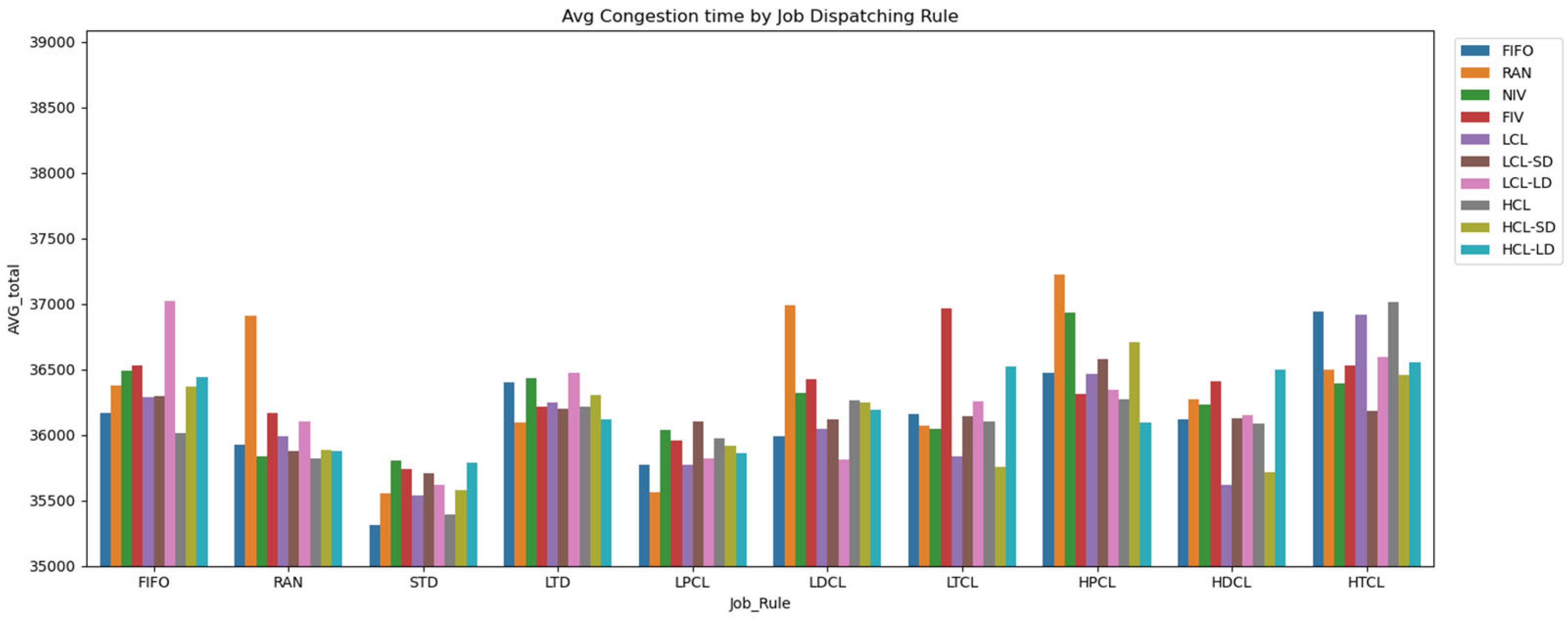

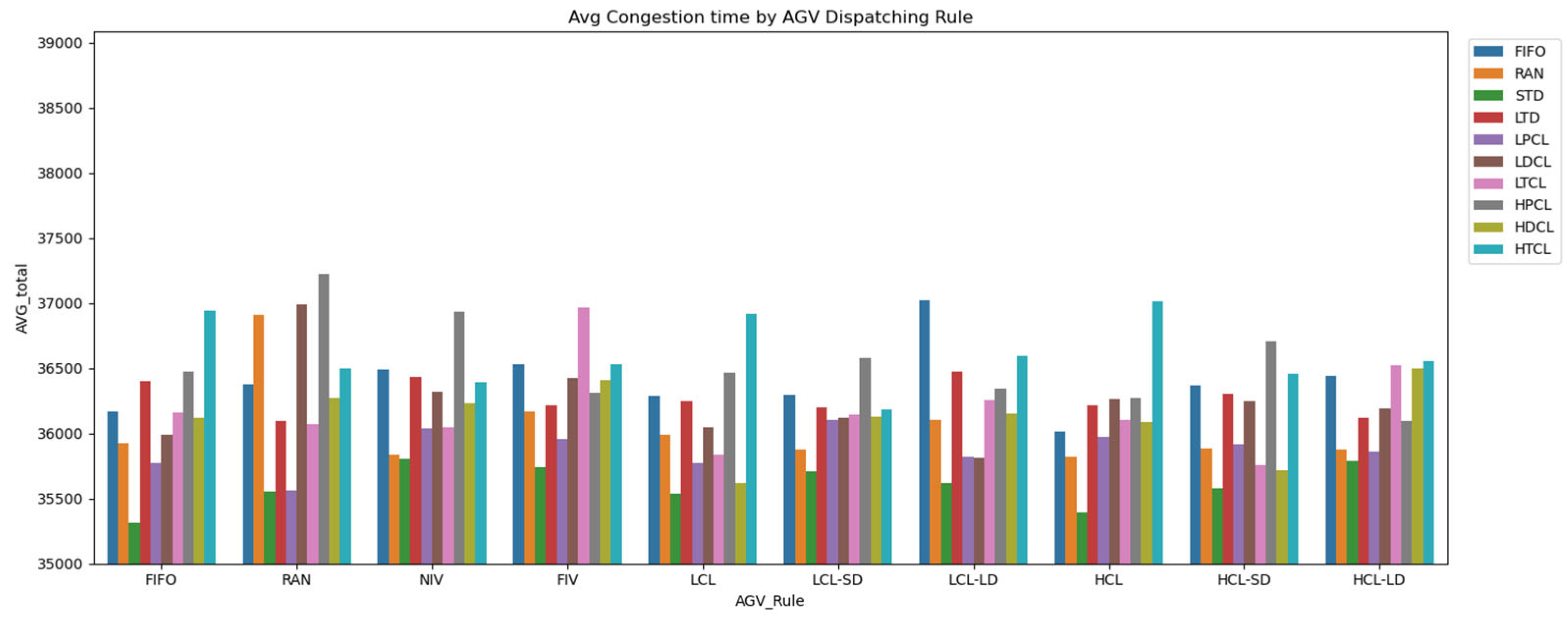

4.6. Experiment Result: AVG Congestion Time

5. Conclusions

5.1. Strategic Trade-Offs Between Local Efficiency and Global Punctuality

5.2. Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Llopis-Albert, C.; Rubio, F.; Valero, F. Fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis applied to the design of a network flow of automated guided vehicles for improving business productivity. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 101, 737–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumus, F.; Kocamaz, A.F. Cloud based indoor navigation for ROS-enabled automated guided vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Data Processing Symposium (IDAP 2019), Malatya, Turkey, 21–22 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Huang, G.Q.; Jiang, Z.; Chu, C. A mechanism for scheduling multi robot intelligent warehouse system face with dynamic demand. J. Intell. Manuf. 2020, 31, 469–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chitsaz, M.; Cordeau, J.F.; Jans, R. A transformation technique for the clustered generalized traveling salesman problem with applications to logistics. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2020, 285, 444–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le-Anh, T.; De Koster, M. A review of design and control of automated guided vehicle systems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 171, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vis, I.F. Survey of research in the design and control of automated guided vehicle systems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 170, 677–709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyekanlu, E.A.; Smith, A.C.; Thomas, W.P.; Mulroy, G.; Hitesh, D.; Ramsey, M.; Kuhn, D.J.; Mcghinnis, J.D.; Buonavita, S.C.; Looper, N.A.; et al. A review of recent advances in automated guided vehicle technologies: Integration challenges and research areas for 5G-based smart manufacturing applications. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 202312–202353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sedghi, L.; John, J.; Noor-A-Rahim, M.; Pesch, D. Formation control of automated guided vehicles in the presence of packet loss. Sensors 2022, 22, 3552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stetter, R. Algorithms and methods for the fault-tolerant design of an automated guided vehicle. Sensors 2022, 22, 4648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vakaruk, S.; Sierra-Garcia, J.E.; Mozo, A.; Pastor, A. Forecasting automated guided vehicle malfunctioning with deep learning in a 5G-based industry 4.0 scenario. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2021, 59, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprihan, R.; Kumar, A.; Stecke, K.E. Evaluation of the impact of information delays on flexible manufacturing systems performance in dynamic scheduling environments. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2013, 67, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, L. A three stage optimal scheduling algorithm for AGV route planning considering collision avoidance under speed control strategy. Mathematics 2023, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.H.; Jang, Y.J. Deadlock prevention and multi agent path finding algorithm considering physical constraint for a massive fleet AGV system. Appl. Soft Comput. 2024, 161, 111725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.S.; Kim, J.W. Multi-AGV scheduling under limited buffer capacity and battery charging using simulation techniques. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, F.; Bitsch, G.; Louw, L. Choosing solution strategies for scheduling automated guided vehicles in production using machine learning. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, L.; Hsu, H.J.; Huang, S.Y.; Wang, H. Scheduling and routing algorithms for AGVs: A survey. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2002, 40, 745–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Meng, L.; Ullah, S.; Zhang, B.; Sang, H.; Duan, P. MILP modeling and optimization of multi-objective three-stage flexible job shop scheduling problem with assembly and AGV transportation. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 25369–25386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klei, C.M.; Kim, J. AGV dispatching. Int. J. Prod. Res. 1996, 34, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.; Jia, X.; He, Q.; Fu, S.; Liu, K. Deep reinforcement learning based AGVs real-time scheduling with mixed rule for flexible shop floor in industry 4.0. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2020, 149, 106749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, Y.C.; Chien, S.H. A simulation study on the performance of delivery-dispatching rules for multiple-load AGVs. In Proceedings of the 5th Asia-Pacific Industrial Engineering and Management Systems Conference (APIEMS), Brisbane, Australia, 12–15 December 2004; pp. 18.1.1–18.1.15. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, Y.C.; Liu, H.C. A simulation study on the performance of pickup-dispatching rules for multiple-load AGVs. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2006, 51, 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, P. Alleviating the collision states and fleet optimization by introducing a new generation of automated guided vehicle systems. Model. Simul. Eng. 2011, 2011, 210628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisuchpen, R. A Simulation of AGV dispatching rules for supplying parts to assembly lines. Int. J. Model. Oper. Manag. 2012, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angra, S.; Chanda, A.; Chawla, V. Comparison and evaluation of job selection dispatching rules for integrated scheduling of multi-load automatic guided vehicles serving in variable sized flexible manufacturing system layouts: A simulation study. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennis, M.; Debbah, M.; Poor, H.V. Ultrareliable and low-latency wireless communication: Tail, risk, and scale. Proc. IEEE 2018, 106, 1834–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heger, J.; Voss, T. Optimal scheduling of AGVs in a reentrant blocking job-shop. Procedia CIRP 2018, 67, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Research Paper | Job Dispatching 1 | AGV Dispatching 2 | Performance Measure | Fleet Size |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ho and Chien (2004) [20] Ho and Liu (2006) [21] | FIFO IDF | LTIS LWTPT LAWTPT SD GQL EDT EADT SRPT SST | Workstation Throughput Average Flow Time Average Tardiness | 3 |

| 2 | Azimi (2011) [22] | FIFO LQS LWT | NV FV | Average Annual Profit Average total collisions per day Average makespan | 5~8 |

| 3 | Pisuchpen (2012) [23] | STF LTF | Manage AGVs in groups | Average AGV Cycle time | 20 |

| 4 | Angra et al. (2018) [24] | SRPTF SSTF IDF GWTQF | NV | Workstation Productivity Average workstation Utilization Average AGV Utilization | 2 |

| 5 | Hu et a l. (2020) [19] | FIFO EDD LWT | NV STD | Average makespan Average Tardiness rate | 3 |

| 6 | Park and Kim (2024) [14] | FIFO LDD SDD LQB SQB LQB SQB RAN | LIT HBL LBL LDP SDP RAN | Average Job waiting time | 10 |

| Rule | Selection Criteria |

| Lowest Congestion Level (LCL) | Selects an AGV in the CCA with the lowest congestion level |

| Lowest Congestion Level–Shortest Distance (LCL-SD) | Selects the nearest AGV in the CCA with the lowest congestion level |

| Lowest Congestion Level–Longest Distance (LCL-LD) | Selects the farthest AGV in the CCA with the lowest congestion level |

| Highest Congestion Level (HCL) | Selects an AGV in the CCA with the highest congestion level |

| Highest Congestion Level–Shortest Distance (HCL-SD) | Selects the nearest AGV in the CCA with the highest congestion level |

| Highest Congestion Level–Longest Distance (HDL-LD) | Selects the farthest AGV in the CCA with the highest congestion level |

| Rule | Selection Criteria |

| Lowest Pickup Point Congestion Level (LPCL) | Selects the job with the lowest pickup area congestion level |

| Lowest Dropoff Point Congestion Level (LDCL) | Selects the job with the lowest dropoff area congestion level |

| Lowest Total Congestion Level (LTCL) | Selects the job with lowest total congestion level |

| Highest Pickup Point Congestion Level (HPCL) | Selects the job with the highest pickup area congestion level |

| Highest Dropoff Point Congestion Level (HDCL) | Selects the job with the highest dropoff area congestion level |

| Highest Total Congestion Level (HTCL) | Selects the job with the highest total congestion level |

| Congestion Function | Congestion Penalty | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Congestion Level (l) | Tl,k | Tl+1,k | Vl (m/s) |

| 0 | 0 | 2 | 1.00 |

| 1 | 2 | 4 | 0.85 |

| 2 | 4 | 6 | 0.70 |

| 3 | 6 | ∞ | 0.55 |

| Job Dispatching Rule | AGV Dispatching Rule |

|---|---|

| First In–First Out (FIFO) | First In First Out (FIFO) |

| Random (RAN) | Random (RAN) |

| Shortest Travel Distance (STD) | Nearest Idle Vehicle (NIV) |

| Longest Travel Distance (LTD) | Farthest Idle Vehicle (FIV) |

| Lowest Pickup Point Congestion Level (LPCL) | Lowest Congestion Level (LCL) |

| Lowest Dropoff Point Congestion Level (LDCL) | Lowest Congestion Level–Shortest Distance (LCL-SD) |

| Lowest Total Congestion Level (LTCL) | Lowest Congestion Level–Longest Distance (LCL-LD) |

| Highest Pickup Point Congestion Level (HPCL) | Highest Congestion Level (HCL) |

| Highest Dropoff Point Congestion Level (HDCL) | Highest Congestion Level–Shortest Distance (HCL-SD) |

| Highest Total Congestion Level (HTCL) | Highest Congestion Level–Longest Distance (HDL-LD) |

| Type | Min (s) | Max (s) |

|---|---|---|

| Short | 1550 | 1800 |

| Normal | 1750 | 2050 |

| Long | 1950 | 2300 |

| Group | Time Shift | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0~4 | 4~8 | 8~12 | 12~16 | 16~20 | 20~24 | |

| A | Short | Normal | Long | Short | Normal | Long |

| B | Normal | Normal | Short | Short | Long | Long |

| C | Short | Short | Normal | Normal | Long | Long |

| D | Long | Normal | Short | Long | Normal | Short |

| Job Dispatching | AGV Dispatching | Average Tardiness (s) | Confidence Interval (95%) | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPCL | NIV | 3728.13 | 1105 | 3423 |

| HPCL | HCL-SD | 3772.70 | 1202 | 3722 |

| LDCL | RAN | 3945.11 | 1245 | 3855 |

| FIFO | HCL-LD | 4184.98 | 1151 | 3564 |

| LDCL | HCL-LD | 4321.33 | 1260 | 3901 |

| Job Dispatching | AGV Dispatching | Average Tardiness (s) | Confidence Interval (95%) | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STD | FIFO | 31,697.10 | 1780 | 5513 |

| STD | LCL-SD | 31,547.40 | 1760 | 5450 |

| STD | LCL | 31,291.00 | 2203 | 6822 |

| STD | HCL | 31,107.90 | 2068 | 6405 |

| STD | HCL-SD | 30,089.20 | 2445 | 7573 |

| Job Dispatching | AGV Dispatching | Tardy Rate | Confidence Interval (95%) | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPCL | FIV | 0.14 | 0.02 | 0.07 |

| LPCL | FIFO | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.08 |

| STD | HCL-LD | 0.14 | 0.01 | 0.03 |

| LPCL | HCL-LD | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.09 |

| LPCL | LCL | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.08 |

| Job Dispatching | AGV Dispatching | Tardy Rate | Confidence Interval (95%) | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIFO | NIV | 0.67 | 0.07 | 0.22 |

| FIFO | LCL | 0.66 | 0.07 | 0.22 |

| FIFO | HCL-SD | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.24 |

| FIFO | LCL-SD | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.24 |

| FIFO | HCL | 0.64 | 0.08 | 0.23 |

| Job Dispatching | AGV Dispatching | Pickup Stay Time (s) | Confidence Interval (95%) | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STD | HCL-SD | 1365.81 | 96.62 | 311.77 |

| STD | LCL-LD | 1423.76 | 108.58 | 350.36 |

| STD | NIV | 1435.03 | 115.53 | 372.79 |

| STD | RAN | 1439.08 | 105.59 | 340.71 |

| STD | HCL-SD | 1446.06 | 113.99 | 367.82 |

| Job Dispatching | AGV Dispatching | Pickup Stay Time (s) | Confidence Interval (95%) | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FIFO | NIV | 4125.45 | 452.81 | 1461.16 |

| FIFO | LCL | 4071.27 | 454.56 | 1466.82 |

| FIFO | HCL-SD | 4031.89 | 492.26 | 1588.46 |

| FIFO | LCL-SD | 3972.27 | 478.70 | 1544.72 |

| LDCL | HCL | 3970.39 | 470.13 | 1517.05 |

| Job Dispatching | AGV Dispatching | Congestion Time (s) | Confidence Interval (95%) | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STD | FIFO | 35,315.36 | 674 | 2087 |

| STD | HCL | 35,390.36 | 674 | 2087 |

| STD | LCL | 35,536.43 | 634 | 1963 |

| STD | RAN | 35,551.92 | 644 | 1996 |

| LPCL | RAN | 35,564.89 | 659 | 2040 |

| Job Dispatching | AGV Dispatching | Congestion Time (s) | Confidence Interval (95%) | Std Dev |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPCL | RAN | 37,224.50 | 477 | 1478 |

| FIFO | LCL-LD | 37,024.67 | 485 | 1501 |

| HTCL | HCL | 37,012.77 | 634 | 1963 |

| LDCL | RAN | 36,993.74 | 616 | 1908 |

| LTCL | FIV | 36,962.39 | 537 | 1663 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kim, J.; Kim, J. Congestion-Aware Scheduling for Large Fleets of AGVs Using Discrete Event Simulation. Electronics 2026, 15, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010139

Kim J, Kim J. Congestion-Aware Scheduling for Large Fleets of AGVs Using Discrete Event Simulation. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010139

Chicago/Turabian StyleKim, Jeonghyeon, and Junwoo Kim. 2026. "Congestion-Aware Scheduling for Large Fleets of AGVs Using Discrete Event Simulation" Electronics 15, no. 1: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010139

APA StyleKim, J., & Kim, J. (2026). Congestion-Aware Scheduling for Large Fleets of AGVs Using Discrete Event Simulation. Electronics, 15(1), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010139