Frequency-Domain Steganography with Hexagonal Tessellation for Vision–Linguistic Knowledge Encapsulation

Abstract

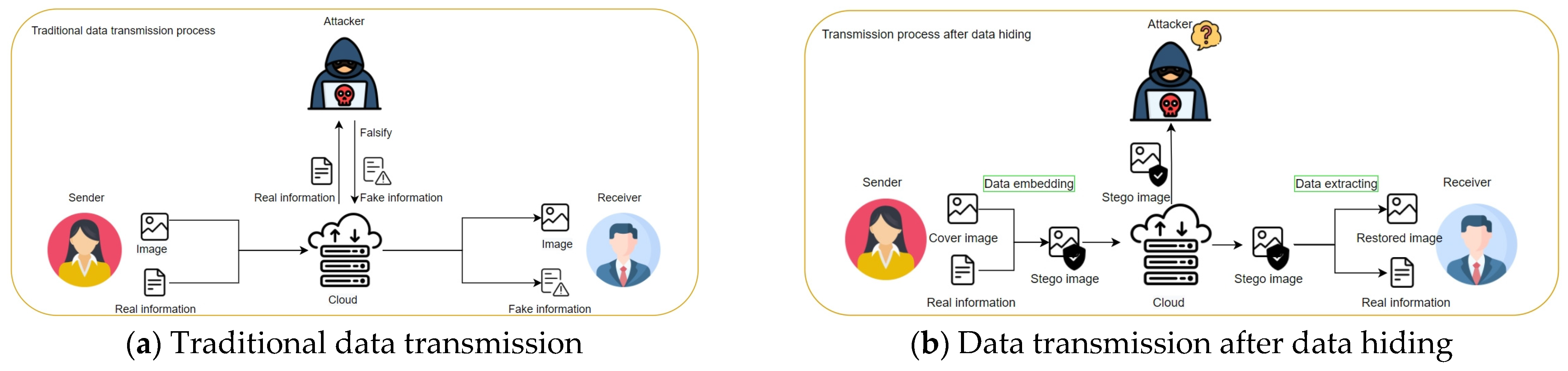

1. Introduction

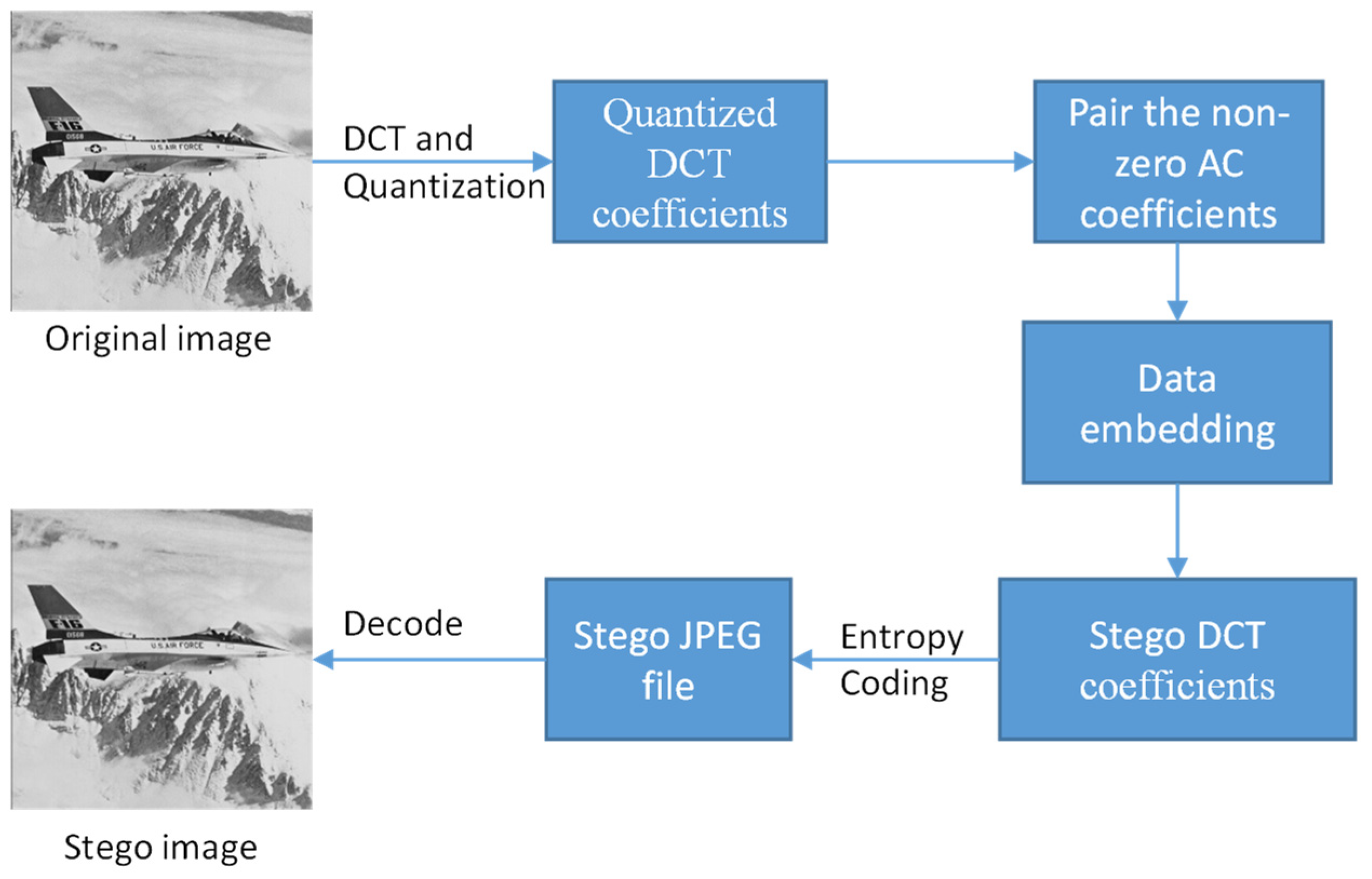

2. Related Works

2.1. Schemes Based on Modified Quantization Tables

2.2. Schemes Based on Modified Huffman Coding

2.3. Schemes Based on Modified Frequency Coefficent

2.4. Observations and Insights

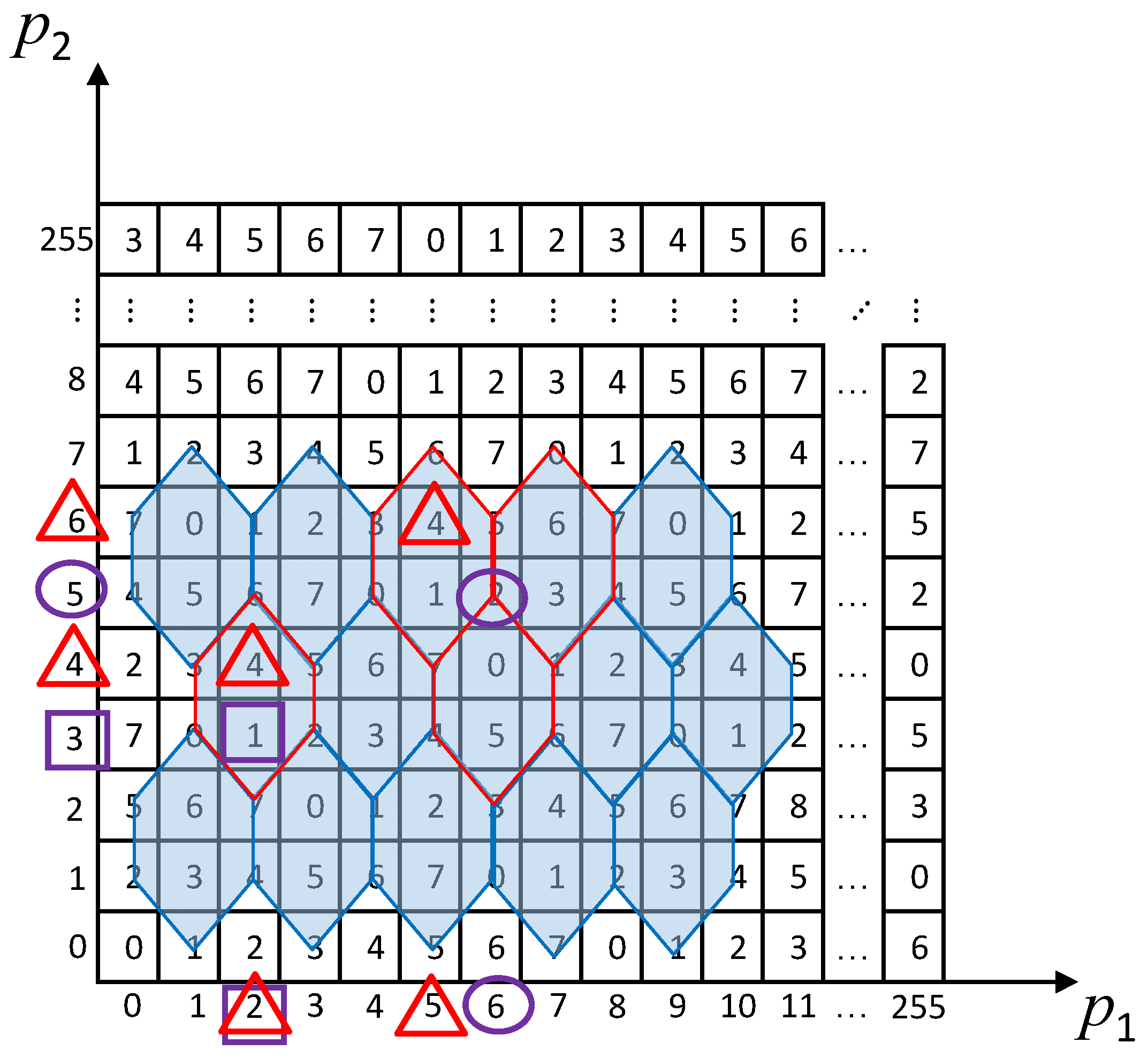

2.5. Method Based on Histogram Shifting

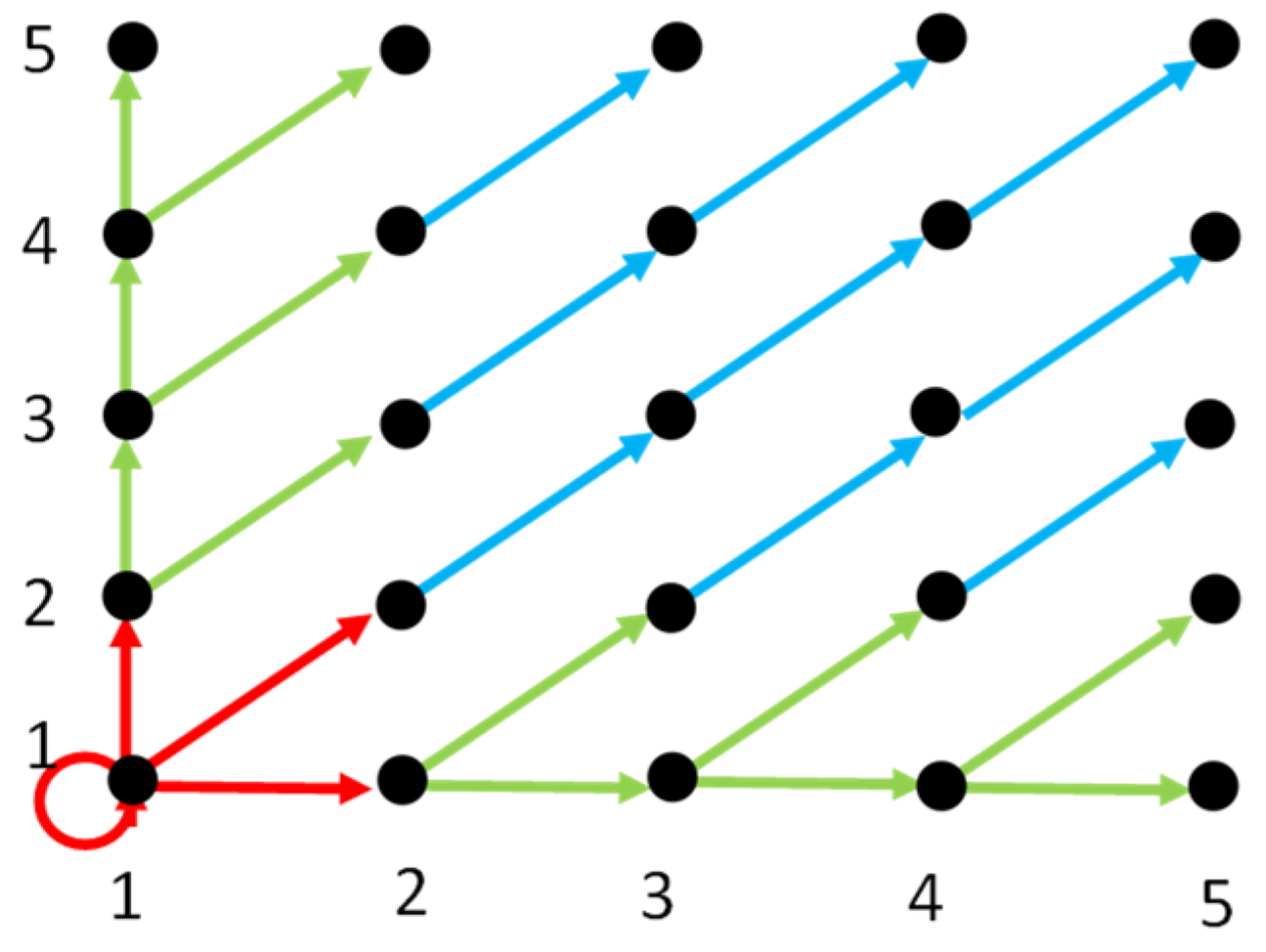

- Red class: If an NACP falls into this category, it is modified in four directions, allowing for the embedding of 2 bits of secret data;

- Green class: If an NACP belongs to this category, it is modified in two directions, enabling the embedding of 1 bit of secret data;

- Blue class: If an NACP falls into this category, it is modified in only one direction, resulting in displacement without data embedding.

3. Proposed Scheme

3.1. Special Hexagonal Tessellation Matrix Construction

3.2. Data Hiding Process

3.3. Data Extraction Process

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chang, C.-C.; Echizen, I. Steganography in Game Actions. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 21029–21042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Liu, Y.; Nguyen, T.S. A novel turtle shell based scheme for data hiding. In Proceedings of the 2014 Tenth International Conference on Intelligent Information Hiding and Multimedia Signal Processing, Kitakyushu, Japan, 27–29 August 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 89–93. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, X.-Z.; Lin, C.-C.; Chang, C.-C. Data Hiding Based on a Two-Layer Turtle Shell Matrix. Symmetry 2018, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.-Z.; Chang, C.-C. Hiding data in dual images based on turtle shell matrix with high embedding capacity and re-versibility. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2021, 80, 36567–36584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Chang, C.-C.; Wang, A. Data hiding based on extended turtle shell matrix construction method. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2017, 76, 12233–12250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palani, A.; Loganathan, A. Semi-Blind watermarking using convolutional attention-based turtle shell matrix for tamper detection and recovery of medical images. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 238, 121903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C. Reversible Linguistic Steganography with Bayesian Masked Language Modeling. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 10, 714–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Wang, X.; Chen, S.; Echizen, I.; Sanchez, V.; Li, C.-T. Deep Learning for Predictive Analytics in Reversible Steganography. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 3494–3510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, N.; Huang, F. Reversible data hiding for JPEG images based on pairwise nonzero AC coefficient expansion. Signal Process. 2020, 171, 107476. [Google Scholar]

- Fridrich, J.; Goljan, M.; Du, R. Lossless data embedding for all image formats. In Security and Watermarking of Multimedia Contents IV; SPIE: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 572–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Lu, Z.M.; Hu, Y.J. A high capacity lossless data hiding scheme for JPEG images. J. Syst. Softw. 2013, 86, 1965–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Wang, K.; Lu, Z.M. An improved VLC-based lossless data hiding scheme for JPEG images. J. Syst. Softw. 2013, 86, 2166–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridrich, J.; Goljan, M.; Du, R. Invertible authentication watermark for JPEG images. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Information Technology: Coding and Computing, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2–4 April 2001; pp. 223–227. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, C.C.; Lin, C.C.; Tseng, C.S.; Tai, W.-L. Reversible hiding in DCT-based compressed images. Inf. Sci. 2007, 177, 2768–2786. [Google Scholar]

- Xuan, G.; Shi, Y.; Ni, Z.; Chai, P.; Cui, X.; Tong, X. Reversible data hiding for JPEG images based on histogram pairs. In Proceedings of the ICIAR 2007, Montreal, QC, Canada, 22–24 August 2007; pp. 715–727. [Google Scholar]

- Sakai, H.; Kuribayashi, M.; Morii, M. Adaptive reversible data hiding for JPEG images. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Symposium on Information Theory and Its Applications, Auckland, New Zealand, 7–10 December 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Qu, X.; Kim, H.J.; Huang, J. Reversible data hiding in JPEG image. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2016, 26, 1610–1621. [Google Scholar]

- Wedaj, F.T.; Kim, S.; Kim, H.J. Improved reversible data hiding in JPEG images based on new coefficient selection strategy. EURASIP J. Image Video Process. 2017, 1, 63. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, D.; Wang, H.; Zhang, W.; Yu, N. Reversible data hiding in JPEG image based on DCT frequency and block selection. Signal Process. 2018, 148, 41–47. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.; Chen, J.; Tang, S. Reversible data hiding in JPEG images based on negative influence models. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Sec. 2020, 15, 2121–2133. [Google Scholar]

- He, J.H.; Pan, X.L.; Wu, H.T.; Tang, S.H. Improved block ordering and frequency selection for reversible data hiding in JPEG images. Signal Process. 2020, 175, 107647. [Google Scholar]

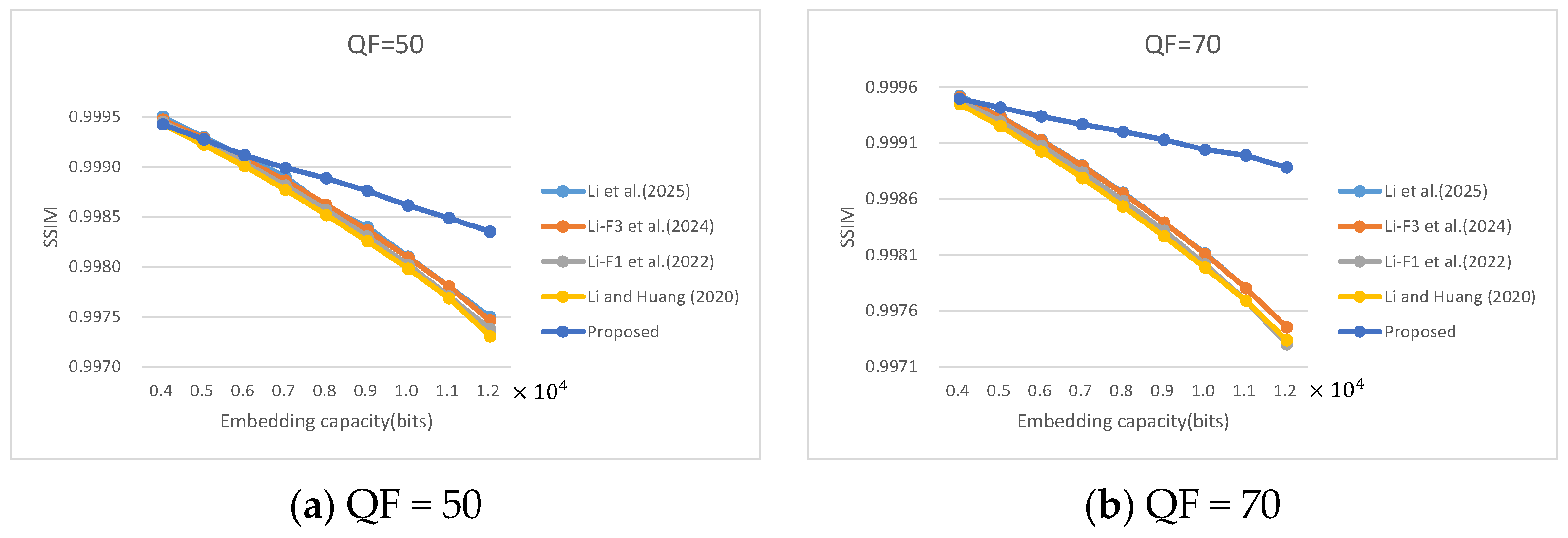

- Li, F.; Zhang, L.; Qin, C.; Wu, K. Reversible data hiding for jpeg images with minimum additive distortion. Inform. Sci. 2022, 585, 142–158. [Google Scholar]

- Li, F.; Qi, Z.; Zhang, X.; Qin, C. Progressive histogram modification for JPEG reversible data hiding. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 1241–1254. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M.Y.; Li, X.L.; Ma, B.; Zhang, X.P.; Zhao, Y. Efficient reversible data hiding for JPEG images with multiple histograms modification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 31, 2535–2546. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, M.Y.; Li, X.L.; Zhao, Y. Reversible data hiding for JPEG images based on multiple two-dimensional histograms. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2021, 28, 1620–1624. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, X.; Wu, T.Y.; Huang, F.J. Reversible data hiding in JPEG images based on coefficient-first selection. Signal Process. 2022, 200, 108639. [Google Scholar]

- Weng, S.W.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, T.C.; Xiao, M.Y.; Zhao, Y. General framework to reversible data hiding for JPEG images with multiple two-dimensional histograms. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2022, 25, 5747–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, W.; Cao, C.; Wang, X.; Shao, Y.; Zhou, M. Reversible data hiding in JPEG images based on improved frequency selection and mapping strategy. Digit. Signal Process. 2025, 156, 104754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, H.; Zhang, X.; Qin, C. JPEG Reversible Data Hiding via Block Sorting Optimization and Dynamic Iterative Histogram Modification. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Image | FSI | Rate | PSNR | SSIM | Max EC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airplane | 16,596 | 3.34% | 44.00 | 0.9853 | 6.7145 | 6.7190 | 107,343 |

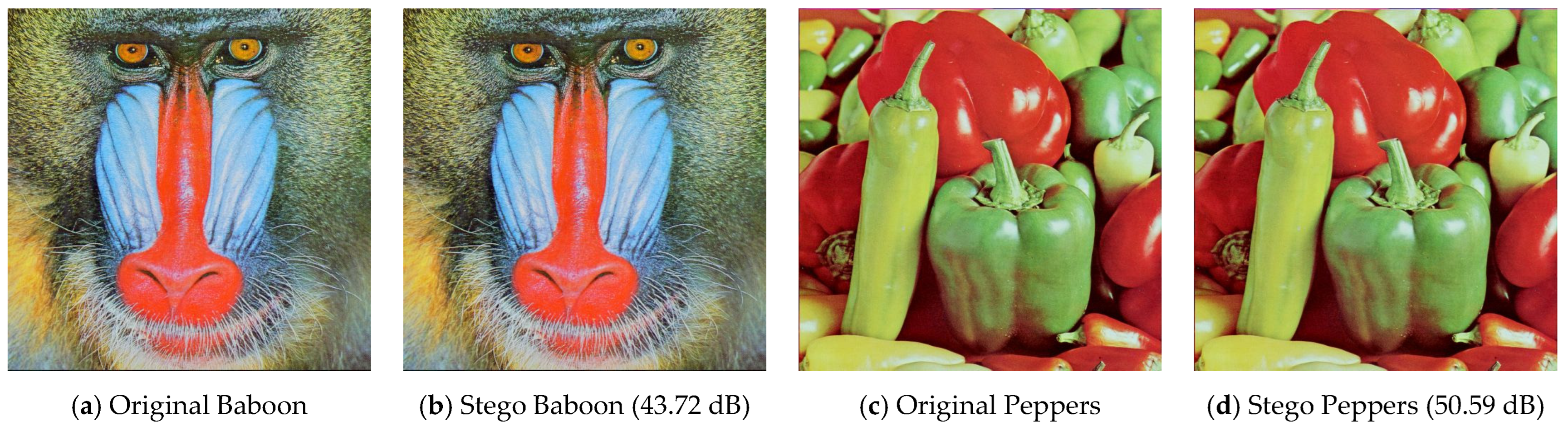

| Baboon | 37,840 | 3.08% | 39.51 | 0.9857 | 7.3651 | 7.3657 | 223,236 |

| Boat | 25,704 | 4.26% | 41.74 | 0.9782 | 7.2137 | 7.2155 | 140,427 |

| Lake | 26,642 | 4.16% | 40.65 | 0.9769 | 7.4612 | 7.4646 | 151,038 |

| Peppers | 24,931 | 4.80% | 41.67 | 0.9716 | 7.5955 | 7.5971 | 121,728 |

| Splash | 16,573 | 4.43% | 44.77 | 0.9794 | 7.2609 | 7.2673 | 92,886 |

| Image | FSI | Rate | PSNR | SSIM | Max EC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airplane | 12,393 | 4.06% | 43.71 | 0.9853 | 6.7240 | 6.7268 | 72,333 |

| Baboon | 24,578 | 3.94% | 38.31 | 0.9853 | 7.3711 | 7.3716 | 160,677 |

| Boat | 16,934 | 4.40% | 41.79 | 0.9802 | 7.2090 | 7.2102 | 92,280 |

| Lake | 16,715 | 4.16% | 41.35 | 0.9818 | 7.4479 | 7.4508 | 98,193 |

| Peppers | 15,083 | 4.87% | 42.99 | 0.9793 | 7.5943 | 7.5952 | 73,956 |

| Splash | 12,179 | 5.06% | 44.72 | 0.9803 | 7.2668 | 7.2711 | 57,543 |

| Image | FSI | Rate | PSNR | SSIM | Max EC | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airplane | 9442 | 3.91% | 43.49 | 0.9860 | 6.7287 | 6.7325 | 57,012 |

| Baboon | 21,407 | 4.33% | 37.93 | 0.9851 | 7.3735 | 7.3741 | 129,621 |

| Boat | 13,288 | 4.51% | 41.96 | 0.9828 | 7.2039 | 7.2050 | 72,150 |

| Lake | 13,423 | 4.28% | 41.68 | 0.9834 | 7.4492 | 7.4512 | 77,412 |

| Peppers | 11,963 | 5.03% | 43.34 | 0.9817 | 7.5951 | 7.5955 | 55,797 |

| Splash | 9912 | 5.34% | 44.90 | 0.9813 | 7.2706 | 7.2743 | 42,132 |

| Image | Description Generated by ChatGPT-4o | Bits |

|---|---|---|

| Airplane | The black-and-white photograph captures a U.S. Air Force jet, possibly a General Dynamics F-16 prototype, soaring above a rugged, snow-covered mountain range. The aircraft’s sleek, aerodynamic form, featuring a pointed nose and delta wings, is prominently displayed. Markings on the fuselage include ‘U.S. AIR FORCE,’ while the tail section bears the identification number ‘01568’ and the General Dynamics logo. The jet appears to be in mid-flight, maintaining a high altitude just above the jagged mountain peaks. The background consists of towering, snow-covered mountains, with a partially cloudy sky adding depth to the scene. The monochrome tones highlight the contrast between the aircraft and the dramatic natural landscape. | 4800 |

| Baboon | The image is a grayscale close-up photograph of a mandrill, a primate species known for its distinctive facial features. The focus is on the front of the mandrill’s face, showcasing its symmetrical structure. The mandrill has deep-set, round eyes with a piercing gaze, surrounded by dark fur. Its nose is long and prominently structured, with vertical ridges extending down both sides. These ridges are lighter in tone compared to the surrounding facial fur. The nostrils are positioned near the lower part of the nose, just above its closed mouth, which appears neutral. The thick fur around the face creates a sense of depth and texture. Individual hair strands are visible, particularly around the cheeks and chin. The fur consists of varying shades of gray, providing contrast between different regions of the face. The background is out of focus, ensuring that the mandrill’s facial details remain the central visual element. The high contrast and sharpness of the image emphasize the intricate patterns on the mandrill’s face. | 4912 |

| Boat | The image depicts a coastal scene with several fishing boats docked on a shore. The boats are positioned in a row, with the one closest to the viewer prominently displaying the name “LA CORNUAILLE” on its hull. The hulls of the boats are weathered, showing signs of wear from their time at sea. The boats are equipped with tall masts and rigging, with fishing equipment such as ropes, nets, and lifebuoys hanging from various parts of the structures. In the background, a lighthouse is visible, adding to the maritime setting. The sky is partly cloudy, with soft clouds scattered throughout. The ground appears to be a mixture of wet sand and small rocks, suggesting that the boats are resting onshore during low tide. To the right of the image, a person wearing a jacket and boots stands near the boats, possibly a fisherman or a worker inspecting the vessels. | 6000 |

| Lake | The image depicts a tranquil lake scene with a sailboat gliding across the calm waters. The photograph is framed by tall pine trees in the foreground, which provide a natural border to the serene landscape. The lake reflects the surrounding trees and the sky, adding to the peaceful atmosphere. The sailboat, with its white sail, stands out as the focal point, contrasting against the darker tones of the water and trees. In the background, a dense forest stretches across the horizon, with scattered clouds above adding depth to the scene. The overall composition emphasizes the harmony between nature and human activity, creating a picturesque and timeless landscape. | 5424 |

| Peppers | The image is a grayscale close-up photograph of a variety of peppers, arranged in an overlapping manner. The assortment includes large bell peppers with smooth, shiny surfaces, as well as elongated chili peppers with slightly wrinkled textures. The peppers are positioned at various angles, creating a natural composition. Light reflections on the surfaces of the peppers add depth and emphasize their three-dimensional shapes. Some peppers have stems attached, which curve slightly, adding an organic feel to the arrangement. The background consists of more peppers, some of which are partially obscured, blending into the scene. The high contrast in the grayscale image helps differentiate the individual peppers, highlighting their contours and subtle surface imperfections. | 5200 |

| Splash | The image is a high-speed grayscale photograph capturing a liquid splash that resembles a crown-like formation. The splash occurs in a shallow dish, where a drop of liquid, likely milk or another white fluid, has impacted the surface, creating a symmetrical ring with elongated tendrils extending outward. The liquid forms a near-perfect circular structure, with droplets suspended at the edges, giving it a delicate and dynamic appearance. The dish holding the liquid is smooth and reflective, adding depth to the image. The background is slightly blurred, ensuring that the splash remains the central focus. The lighting is soft and evenly distributed, highlighting the intricate details of the splash without creating harsh shadows or overexposure. The high contrast between the liquid and the background enhances the visual clarity of the motion captured. | 5600 |

| Image | Scheme | PSNR | FSI | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QF = 50 | QF = 70 | QF = 90 | QF = 50 | QF = 70 | QF = 90 | ||||||||||||||

| 1000 | 4000 | 6000 | 3000 | 6000 | 9000 | 9000 | 12,000 | 15,000 | 1000 | 4000 | 6000 | 3000 | 6000 | 9000 | 9000 | 12,000 | 15,000 | ||

| Baboon | Li-N [9] | 51.32 | 44.1 | 41.66 | 48.78 | 44.93 | 42.14 | 47.17 | 45.19 | 43.54 | 784 | 3768 | 5752 | 3072 | 6344 | 10,072 | 12,016 | 16,344 | 19,216 |

| Li-F1 [22] | 52.02 | 44.28 | 41.72 | 49.28 | 45.06 | 42.29 | 47.14 | 45.16 | 43.58 | 712 | 3208 | 5816 | 2864 | 6192 | 9832 | 11,736 | 15,880 | 19,152 | |

| Li-F3 [23] | 52.26 | 44.55 | 41.92 | 49.37 | 45.29 | 42.45 | 47.25 | 45.25 | 43.65 | 744 | 3096 | 5512 | 2976 | 5784 | 9136 | 10,720 | 14,496 | 18,432 | |

| Li [29] | 52.3 | 44.58 | 42.02 | 49.44 | 45.34 | 42.48 | 47.28 | 45.28 | 43.69 | 400 | 3024 | 5136 | 2488 | 5760 | 9032 | 11,384 | 14,464 | 18,328 | |

| Proposed | 51.26 | 45.32 | 43.23 | 49.07 | 45.96 | 43.68 | 47.44 | 46.22 | 45.24 | 184 | 231 | 203 | 335 | 307 | 371 | 392 | 533 | 498 | |

| Peppers | Li-N [9] | 52.04 | 45.11 | 42.44 | 50.86 | 47.3 | 44.81 | 51.82 | 50.16 | 48.77 | 1232 | 4664 | 7160 | 3696 | 7128 | 10,240 | 10,296 | 13,992 | 18,896 |

| Li-F1 [22] | 53.79 | 45.39 | 42.51 | 52.05 | 47.97 | 45.18 | 52.08 | 50.35 | 48.89 | 1264 | 4328 | 7152 | 3448 | 6960 | 9736 | 10,288 | 14,008 | 17,496 | |

| Li-F3 [23] | 53.9 | 45.84 | 43.22 | 52.16 | 48.21 | 45.54 | 52.27 | 50.55 | 49.14 | 1352 | 4248 | 6528 | 3392 | 6520 | 9480 | 9592 | 13,472 | 17,440 | |

| Li [29] | 53.98 | 45.94 | 43.28 | 52.2 | 48.3 | 45.63 | 52.32 | 50.59 | 49.18 | 1216 | 4216 | 6488 | 3376 | 6480 | 9208 | 9368 | 13,440 | 17,848 | |

| Proposed | 52.16 | 48.33 | 45.91 | 51.88 | 49.71 | 48.69 | 52.52 | 51.22 | 50.32 | 84 | 114 | 123 | 147 | 134 | 177 | 170 | 333 | 360 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chi, H.; Chang, C.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Liu, J.-C. Frequency-Domain Steganography with Hexagonal Tessellation for Vision–Linguistic Knowledge Encapsulation. Electronics 2025, 14, 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14071379

Chi H, Chang C-C, Chang C-C, Liu J-C. Frequency-Domain Steganography with Hexagonal Tessellation for Vision–Linguistic Knowledge Encapsulation. Electronics. 2025; 14(7):1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14071379

Chicago/Turabian StyleChi, Hengxiao, Ching-Chun Chang, Chin-Chen Chang, and Jui-Chuan Liu. 2025. "Frequency-Domain Steganography with Hexagonal Tessellation for Vision–Linguistic Knowledge Encapsulation" Electronics 14, no. 7: 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14071379

APA StyleChi, H., Chang, C.-C., Chang, C.-C., & Liu, J.-C. (2025). Frequency-Domain Steganography with Hexagonal Tessellation for Vision–Linguistic Knowledge Encapsulation. Electronics, 14(7), 1379. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14071379