1. Introduction

A Brain-Computer -Interface (BCI) is a direct neural communication pathway between the brain and an external electronic device [

1]. BCIs are typically regarded as a specialized branch of human–computer interaction. Over the past decade, research in the field has primarily focused on supporting patients with motor impairments or disabilities [

2]. However, with recent technological advances and the growing availability of commercial electroencephalography (EEG) devices, BCIs have increasingly expanded into areas such as gaming [

3,

4].

BCIs are commonly categorized into invasive and non-invasive systems [

5]. Invasive BCIs employ surgically implanted electrodes to capture high-resolution neural activity and are suitable for applications such as restoring mobility or vision. Owing to risks including infection and tissue damage, they are typically reserved for severe clinical cases, such as paralysis or blindness. In contrast, non-invasive BCIs—particularly EEG-based systems—are safer and far more practical for everyday use, although they provide lower spatial resolution. Consequently, non-invasive BCIs have become increasingly popular for consumer-oriented applications such as gaming and neurofeedback [

6].

A wide range of commercial EEG devices has been used in the development of BCI-controlled video games [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12]. These devices, which vary from 1 to 64 electrodes, are affordable and widely accessible. The most commonly used EEG systems in this field are summarized in

Table 1.

All BCI systems generally follow the same processing pipeline [

13]. First, electrical brain activity is measured and recorded using an EEG device. The raw signals are then preprocessed to remove noise and artifacts. Feature extraction follows, and the resulting features are fed into a classifier [

14], which is typically trained offline. During real-time use, the classifier translates incoming EEG data into application-specific commands. Among the various paradigms used in BCIs, Motor Imagery (MI) has been widely adopted for voluntary control [

2], as it enables users to generate distinct neural patterns without physical movement, making it suitable for hands-free gaming and assistive technologies.

Motor Imagery (MI) is defined as the mental simulation of movement without actual execution—is a well-established paradigm in EEG-based BCIs [

15]. During MI tasks, individuals imagine specific limb movements, generating neural activity primarily in the sensorimotor cortex. These patterns can be captured using EEG and used to control external devices. However, decoding MI signals remains challenging due to inter-subject variability and low signal to noise ratios. Recent advances in deep learning, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have shown promise in improving MI classification accuracy [

16,

17]. CNNs can automatically extract spatial and temporal features from EEG signals, enhancing the robustness and generalization capabilities of BCI systems [

18].

Research on human-machine interactions, carried out over a wider audience, shows that you can improve a user’s experience by being able to estimate differences between users. For example, researchers have recently developed methods for reducing cognitive load and improving task performance when there is a conflict between user goals and system goals [

19]. Moreover, work in affective computing shows that robust modeling of human-generated signals requires representations that remain stable despite substantial variability across individuals, further emphasizing the need for systems that anticipate user-specific differences [

20].

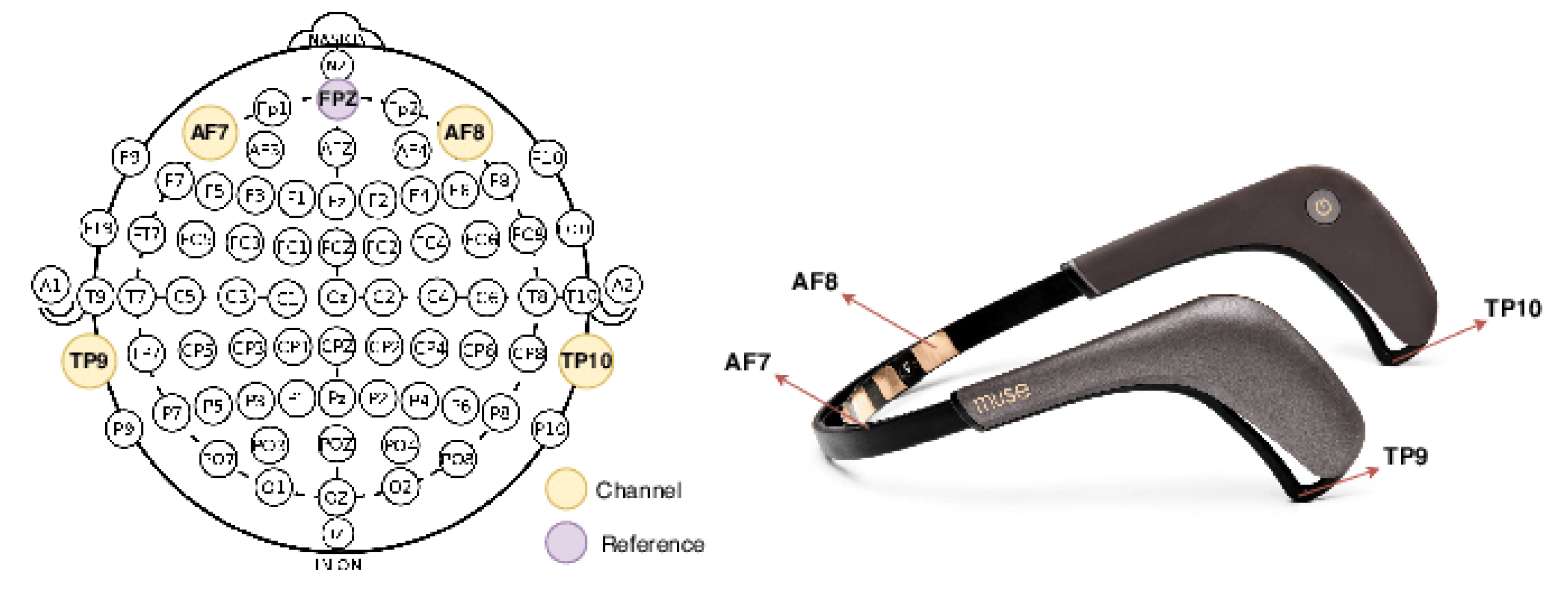

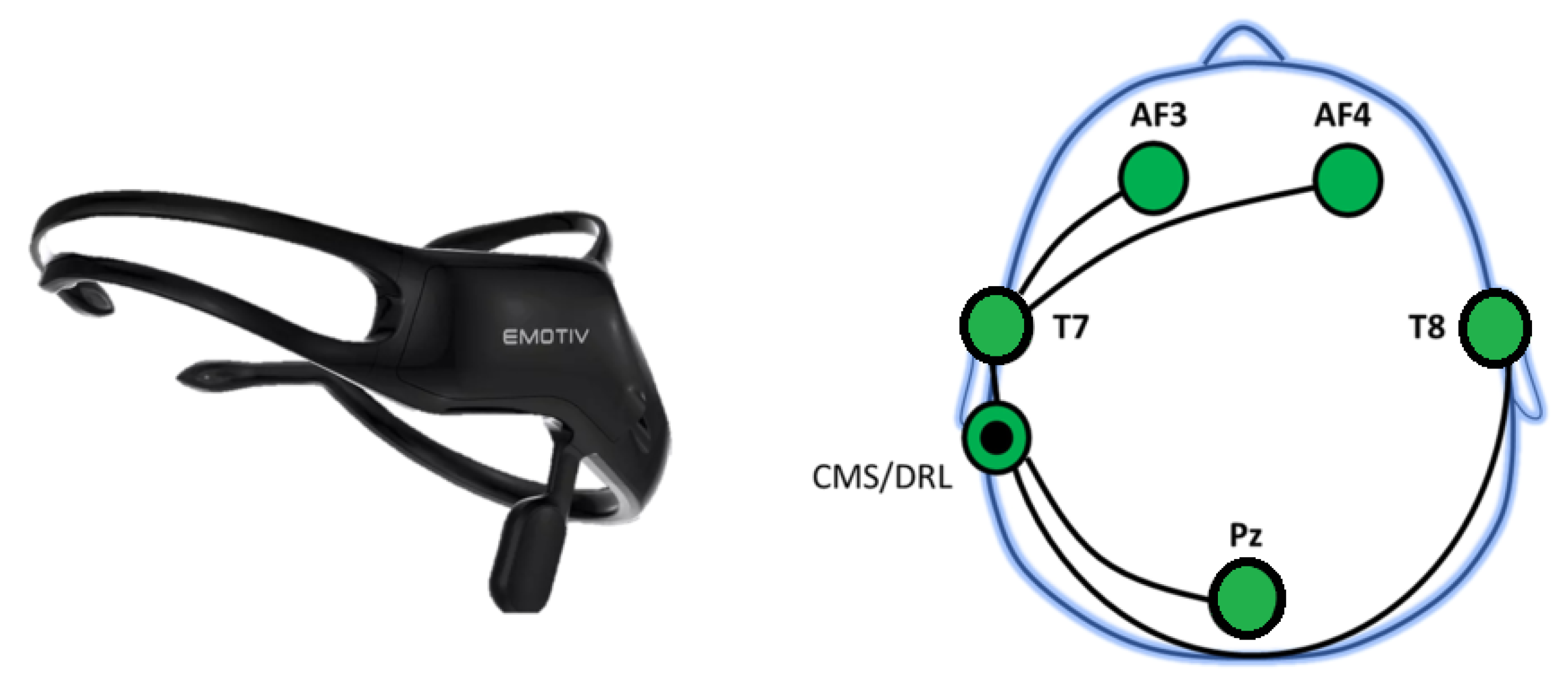

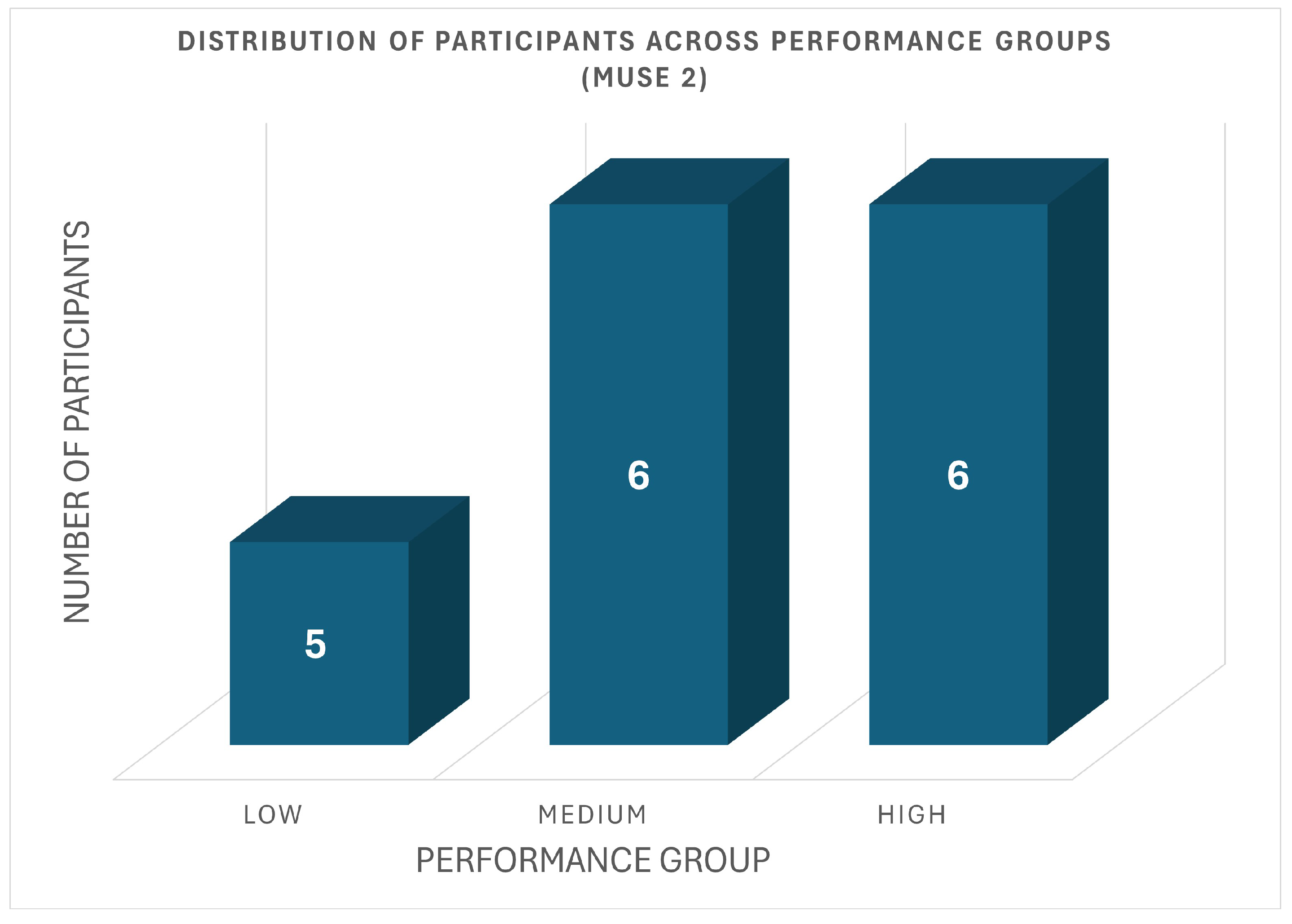

In this work, we investigate the prediction of user performance in a three-dimensional (3D) BCI-controlled game using pre-task MI EEG recordings. Participants used either the Muse 2 or the Emotiv Insight commercial EEG headset to perform MI tasks prior to gameplay. Based on their in-game performance, participants were categorized into three performance groups: low, medium, and high. Our goal is to predict a subject’s performance level solely from their MI recordings using a CNN-based model.

2. Related Work

Deep learning methods, and specifically CNNs, have significantly contributed to the development of BCI systems by performing well on the decoding of EEG signals in MI tasks. The majority of the existing literature, however, has focused on command-level classification, where the goal is to discriminate imagined movements (e.g., left vs. right hand). More recently, an emerging line of research has attempted to move beyond command decoding and explore how deep learning can help identify individual variability in BCI performance. The subsequent section provides an overview of different studies that address command-level classification and subject-level prediction of performance using CNNs and other EEG-based approaches.

Fewer studies examine subject-level performance categorization, whereas the majority of BCI research employing CNNs concentrate on classifying motor commands, such as left or right hand motor images. Zhu et al. [

21] performed a systematic comparison of five deep learning networks EEGNet, Deep ConvNet, Shallow ConvNet, ParaAtt, and MB3D—for MI EEG classification in BCI applications. On the basis of two large datasets (MBT-42 and Med-62), they optimized each network with hyperparameter tuning and evaluated subject-wise classification accuracy. The MB3D model with a 3D spatial representation of EEG channels worked well but with increased computational cost, whereas small models like EEGNet achieved comparable accuracy. Their results stress the significance of input representation and model structure on MI classification performance. These studies, however, focus exclusively on decoding MI commands, not on predicting user performance or aptitude.

Tibrewal et al. [

22] evaluated the ability of deep learning models, specifically CNNs to improve classification efficiency in users of BCI motor imagery recordings who have previously been considered ’BCI inefficient’. A group of 54 participants underwent testing where the researchers compared a CNN model trained on EEG signals with a conventional Common Spatial Patterns (CSP) + Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) system and discovered the CNN produced superior results compared to the baseline approach with the most improvement seen with low-ability participants. The research team demonstrated that BCI underperformance cannot be attributed purely from human factors because CNN models could identify essential brain activity patterns which standard models usually overlook. The researchers implemented no manual feature extraction or preprocessing in their approach to prove that deep learning models maintain their performance across varied subjects while handling EEG signal imperfections. Nonetheless, their objective remains within task MI decoding enhancement, rather than forecasting overall user performance before interaction with the BCI system.

Another direction investigates pre-task prediction of MI performance based on neural traits. Cui et al. [

23] proposed a method that uses microstate EEG features extracted from resting state recordings to predict whether a user will be a high or low performance MI BCI participant using microstate resting state features. The research findings showed that specific microstate parameters demonstrated a notable connection to MI task execution capabilities. Their algorithm trained on these microstate features showed excellent predictive performance (AUC = 0.83), demonstrating that the intrinsic dynamics of brain states relate to MI control capabilities. However, the framework uses resting-state EEG, takes a binary prediction approach, and uses classical ML machine learning models in its analyses of MI tasks or time-frequency distribution.

In parallel with advances in MI decoding, recent work has shown that neurophysiological and behavioral signals reflect broader cognitive and performance-related states that are valuable for predictive modeling. Chen et al. [

24] demonstrated that multi-band EEG functional connectivity is capable of reliably identifying impaired cognitive states in demanding operational scenarios, indicating that neural dynamics provide informative markers relevant to performance estimation and highlighting the value of connectivity-based EEG features. Similarly, Xu et al. [

25] utilized gaze behavior and flight-control signals, in combination with multimodal deep learning to assess pilot situational awareness, reinforcing that predicting human performance in interactive environments has substantial practical value. Collectively, these findings underscore that effective performance prediction relies on capturing the user’s underlying cognitive state, a principle that remains central regardless of the specific modality or operational domain.

Τhis work examines a different and understudied problem by predicting multilevel BCI gaming performance (low, medium, high) from multiclass pre-game MI EEG using spectrogram based CNNs that use low channel consumer devices. It is important to note that in our study, the performance labels do not indicate MI decoding accuracy—as seen in other BCI studies. The labels indicate actual user performance in a BCI-controlled game in three dimensions that required continuous control in multiple degrees of freedom.

5. Discussion

The results demonstrate that CNNs can effectively predict BCI user performance in a BCI gaming environment based solely on MI (MI) EEG recordings. The findings indicate strong potential for robust classification between different performance levels using spectrogram-based deep learning, with the CNN achieving 83% accuracy on Muse 2 data and 94% on Emotiv Insight data.

A key observation is the clear difference in performance between the two datasets. The model performed better on the Emotiv Insight dataset across all classification metrics—precision, recall, and F1-score—within all three performance categories. This improvement is attributed to the device’s electrode coverage and optimized sensor placement, which provide better spatial resolution. In contrast, although Muse 2 is more accessible and affordable, it exhibited slightly lower performance, particularly for the medium-performing group, which showed greater overlap in misclassifications. These findings are consistent with prior studies and are also reflected in the class distributions observed for each device.

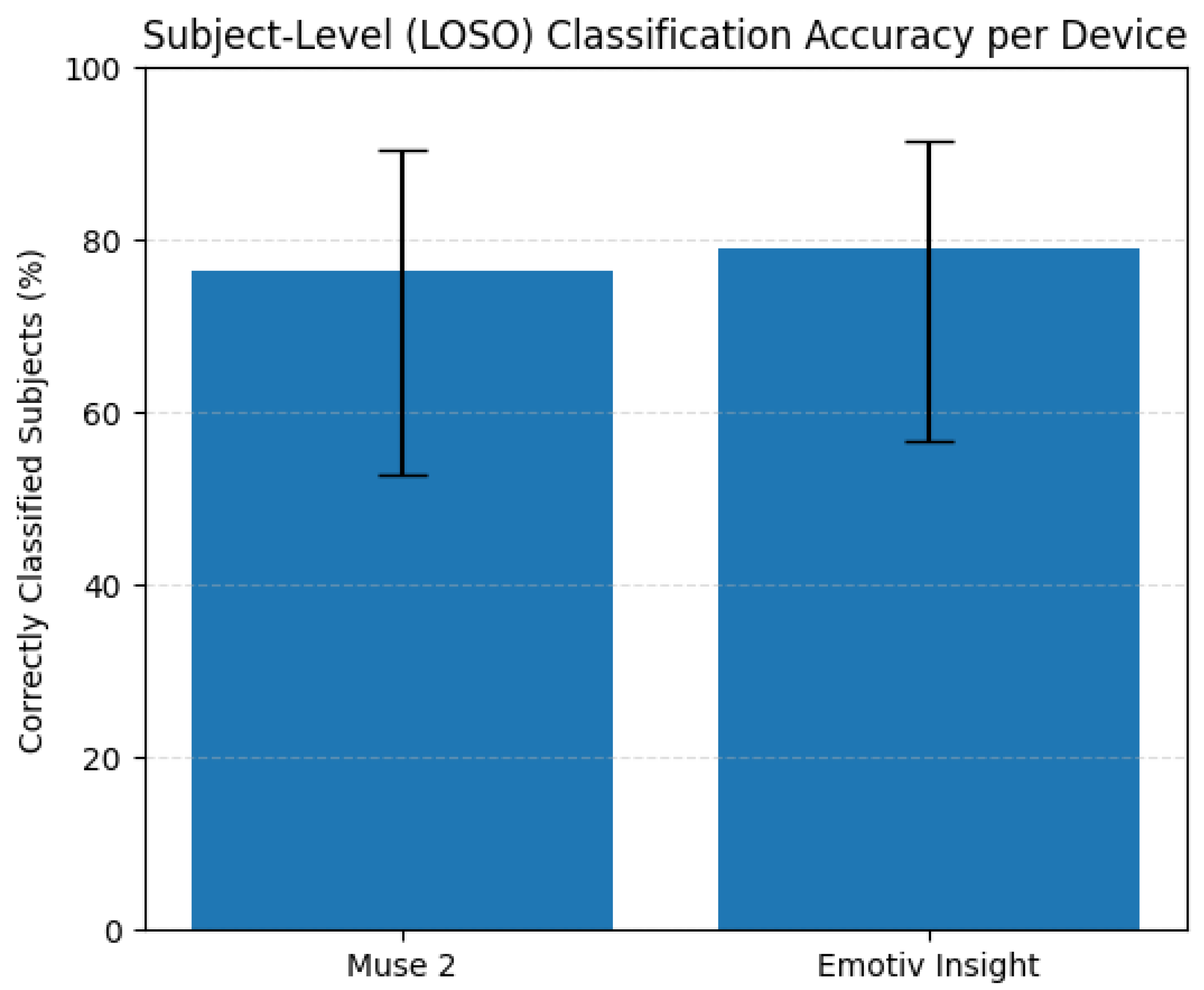

Regarding real-world applicability, the LOSO-CV technique approximates real-time performance evaluation. The results, although slightly lower than those obtained from the standard train–test split, remain promising. The Emotiv Insight dataset achieved 84% subject-level accuracy, with only 3 out of 19 subjects misclassified. Similarly, the Muse 2 dataset achieved 75% subject-level accuracy, misclassifying only 4 users. This reduction in performance compared to the epoch-level results (as shown in

Section 4.1.2) was expected due to the more demanding nature of cross-subject generalization.

Overall, the superior performance exhibited in epoch level is consistent with the structured temporal dependencies inherent in EEG data. Recent work has shown that exploiting within-trial dependencies enhances affective BCI performance, as adjacent temporal segments carry structured information rather than independent noise [

30]. This provides a compelling explanation for the increased discriminability of epoch-level spectrograms in our experiments, where local temporal frequency patterns appear to encode informative markers of subsequent BCI control performance.

Building on this observation, the results demonstrate the CNN’s ability to exploit temporal and frequency-based information to automatically derive correlations between EEG and motor skill units. The ability of the CNN to extract informative features through an end-to-end learning process supports the increased movement toward fully automated BCI systems, and ultimately, the development of BCI systems which rely on user-specific data for predicting user capability without the need for manual feature construction.

5.1. Cross-Device Robustness and Statistical Significance Analysis

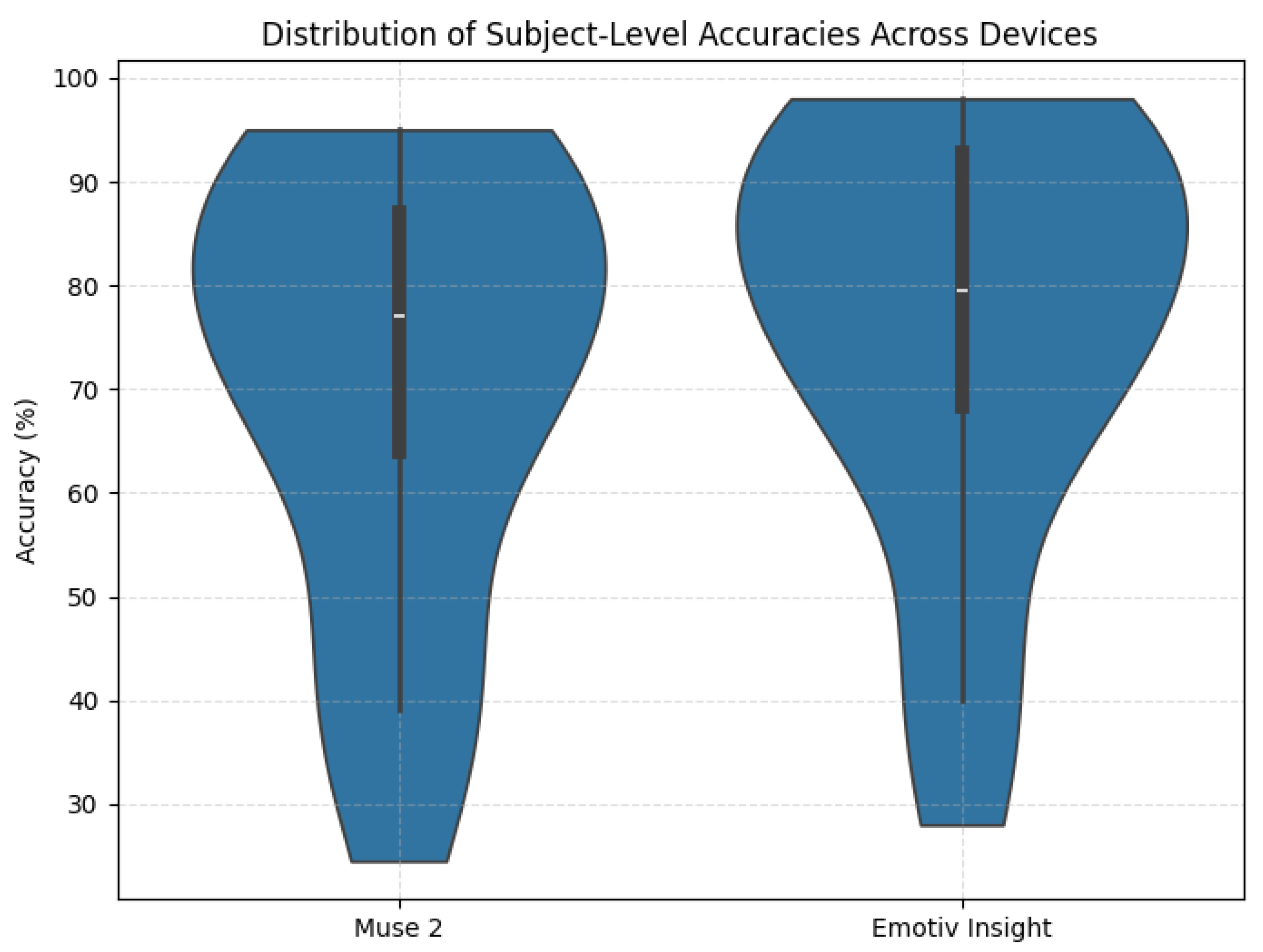

To further examine the robustness of the proposed CNN across different EEG hardware, we compared the subject-level performance obtained through the LOSO-CV procedure for the Muse 2 and Emotiv Insight datasets.

Figure 12 presents a violin plot illustrating the distribution of continuous per-subject accuracies for each device. Despite substantial differences in electrode placement, sampling rate, and signal characteristics, both datasets exhibit consistently high accuracies, indicating that the spectrogram-based CNN remains reliably effective across distinct commercial EEG systems.

To statistically validate these findings, we performed exact binomial significance testing on the LOSO subject-level outcomes. For the Muse 2 dataset, 13 out of 17 subjects were correctly classified (exact binomial p-value = 0.00034), while for the Emotiv Insight dataset, 16 out of 19 subjects were correctly classified (p = 0.000007). In both cases, performance was significantly above the three-class chance level of 33.3%.

We further quantified uncertainty by computing 95% Wilson confidence intervals for the subject-level accuracy proportions. As shown in

Figure 13, the confidence interval for the Muse 2 dataset ranged from 0.501 to 0.932, whereas that for the Emotiv Insight dataset ranged from 0.604 to 0.966, confirming that the true accuracy lies well above chance for both devices. Finally, Fisher’s exact test revealed no statistically significant difference in classification reliability between the two devices (

p = 0.684), suggesting that the proposed model generalizes comparably across hardware platforms.

As per the epoch-level classification, for the Muse 2 dataset, the epoch-level accuracy of 83% corresponded to a 95% Wilson confidence interval of [80.7%, 83.4%] based on 2148 test epochs. On the other hand for the Emotiv Insight dataset, the epoch-level accuracy of 95% corresponded to a 95% Wilson confidence interval of [93.48%, 95.08%] computed over 3228 test epochs.

Figure 14 depicts the confidence intervals for both devices under the epoch-level classification. These intervals reflect the precision of the accuracy estimates, with narrower intervals indicating greater statistical reliability.

5.2. Novelty and Contribution

This work investigates a relatively unexplored direction in BCI research, namely, the prediction of user performance levels in a game-based BCI environment using only MI EEG recordings prior to actual task engagement. Unlike previous studies that focus either on classifying MI commands or on improving decoding accuracy during task execution, our objective is to determine whether early task-evoked EEG activity can reliably forecast how well a user will subsequently control a BCI system.

Compared to the existing literature, as presented in

Table 6 this study differs in several key aspects. Zhu et al. [

21] focused on command level MI classification from high density clinical EEG systems, without addressing performance prediction or pre-task aptitude assessment. On the other hand Tiberwal et al. [

22] investigate BCI inefficiency and use CNNs to enhance MI decoding for low-performing users, yet their analysis remains strictly within task and does not attempt to predict future user performance before interaction with the BCI. The work conducted by Ciu et al. [

23] use resting state microstate features to perform binary prediction of MI aptitude in a smaller cohort of 28 subjects; however, their work does not incorporate MI recordings, time–frequency representations, or real world BCI performance metrics.

This study provides an initial proof ofco ncept for three-level performance prediction using low channel consumer devices, with class labels derived from interaction in a 3D BCI game involving multiple degrees of freedom rather than from offline MI accuracy metrics. The inclusion of task based spectrograms and a cross-subject LOSO evaluation further differentiates this work, as only the second experiment in Zhu et al. [

21] employed LOSO for MI classification. While preliminary, the findings suggest that early MI responses may contain informative patterns related to subsequent BCI control performance, motivating future studies with larger and more diverse datasets.

5.3. Baseline Comparison

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed spectrogram-based CNN, an additional baseline experiment was conducted using two widely adopted deep learning architectures for EEG analysis: EEGNet and ShallowConvNet and CSP + LDA, a classical BCI classification method. All models were re-implemented within the same training and evaluation framework used in our study with identical data splits, augmentation strategy, and LOSO protocol, thus ensuring a consistent and fair comparison at the classification level. This setup allowed us to assess whether more established EEG-specific architectures could outperform our spectrogram oriented approach under identical experimental conditions.

The results of the epoch-level evaluation are presented in

Table 7. The proposed spectrogram-based CNN outperformed all models across both datasets. Although CSP + LDA is a classical method in BCI classification, it does not perform adequately in this three-class setting, achieving only 56% and 62% accuracy in the respective datasets. EEGNet achieved higher accuracy but still reached only 76% and 78%. ShallowConvNet performed better than both, achieving 82% accuracy in the Muse 2 dataset and 92% in the Emotiv dataset. Notably, while ShallowConvNet reached performance levels close to those of our model in the Emotiv dataset (94%), this outcome is expected due to its shallow architecture, which is known to fit smaller datasets more easily and to benefit from reduced inter-subject variability.

A more pronounced contrast between the models emerges under the LOSO-CV evaluation, as shown in

Table 8. In this setting, all models, CSP + LDA, EEGNet and ShallowConvNet exhibited a substantial drop in performance, with the CSP + LDA model achieving accuracy of 39% in the Muse 2 cohort and 49% in the Emotiv cohort. On the other hand, EEGNet and ShallowConvNet achieved only 52% and 53% accuracy on the Muse 2 dataset and 53% and 55% accuracy in the Emotiv Dataset respectively. This steep decline indicates poor generalization to unseen individuals, an expected limitation of these architectures, as they rely heavily on subject-specific temporal patterns and are primarily tuned for raw EEG inputs. This degradation is particularly evident for the CSP + LDA pipeline, which relies on subject-specific spatial filters that do not generalize well to unseen individuals. Furthermore, CSP + LDA is traditionally tailored for binary motor-imagery tasks (e.g., left vs. right hand), making it inherently less suitable for the multi-class performance prediction problem addressed here. In contrast, by employing spectrograms as inputs, the proposed CNN achieved significantly higher subject-level accuracies of 75% for Muse 2 and 83% for Emotiv, demonstrating strong robustness against inter-subject variability. These results suggest that the proposed model not only performs competitively at the epoch level but also generalizes markedly better across subjects, a crucial characteristic for practical deployment in real world BCI applications.

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

While the results are promising, this study has several limitations that future work should address. First, although the sample size is sufficient for a proof of concept, it remains relatively small. This limits the generalizability of the findings to larger populations with more diverse EEG characteristics and gaming abilities. Second, the approach was tested using pre-task EEG recordings only. While such recordings enable early prediction, they do not incorporate real-time adaptation and feedback mechanisms that are essential in dynamic gaming environments. Integrating adaptive in-game feedback could enhance both prediction accuracy and user engagement.

Furthermore, although spectrograms capture informative time–frequency information, they are less sensitive to spatial and topological aspects of brain activity. Future work could explore hybrid representations that combine spectrogram inputs with graph-based EEG features to better model inter-channel connectivity and spatial dynamics. Another limitation concerns cross-device generalization. Although two independent consumer grade EEG devices were analyzed, a model trained on one device does not necessarily transfer to another due to differences in electrode positioning and signal characteristics. Future work should therefore explore domain adaptation and transfer learning strategies to improve hardware-agnostic robustness. Moreover, incorporating a brief user-specific calibration trial prior to gameplay could further improve classification accuracy by accounting for inter-subject variability. Finally, evaluating the proposed model in real-time BCI scenarios, where decisions are made continuously from live EEG input, would help determine its suitability for deployment in practical neuroadaptive gaming systems. Taken together, these directions open promising avenues toward predictive personalization in BCI games, enabling customized user experiences based on early neurophysiological profiling.

In this study, we introduced a deep learning framework capable of predicting user performance in BCI-based gaming using pre-game MI EEG recordings. The proposed CNN achieved strong and consistent accuracy across both datasets, demonstrating that time–frequency representations of pre-task EEG activity can reliably predict BCI control performance during gameplay. These findings provide an initial demonstration of the feasibility of early performance prediction in BCI systems and motivate further refinement and investigation. Finally, this work serves as an initial exploration of pre-task user profiling, which can be further enhanced in future studies. Larger datasets, additional performance metrics, and the inclusion of different EEG hardware could support broader validation of this approach and establish its applicability across diverse users and devices. Expanding these areas is not a limitation of our method but rather a natural progression toward consolidating and generalizing the promising results observed here.