A Unified Fault-Tolerant Batch Authentication Scheme for Vehicular Networks

Abstract

1. Introduction

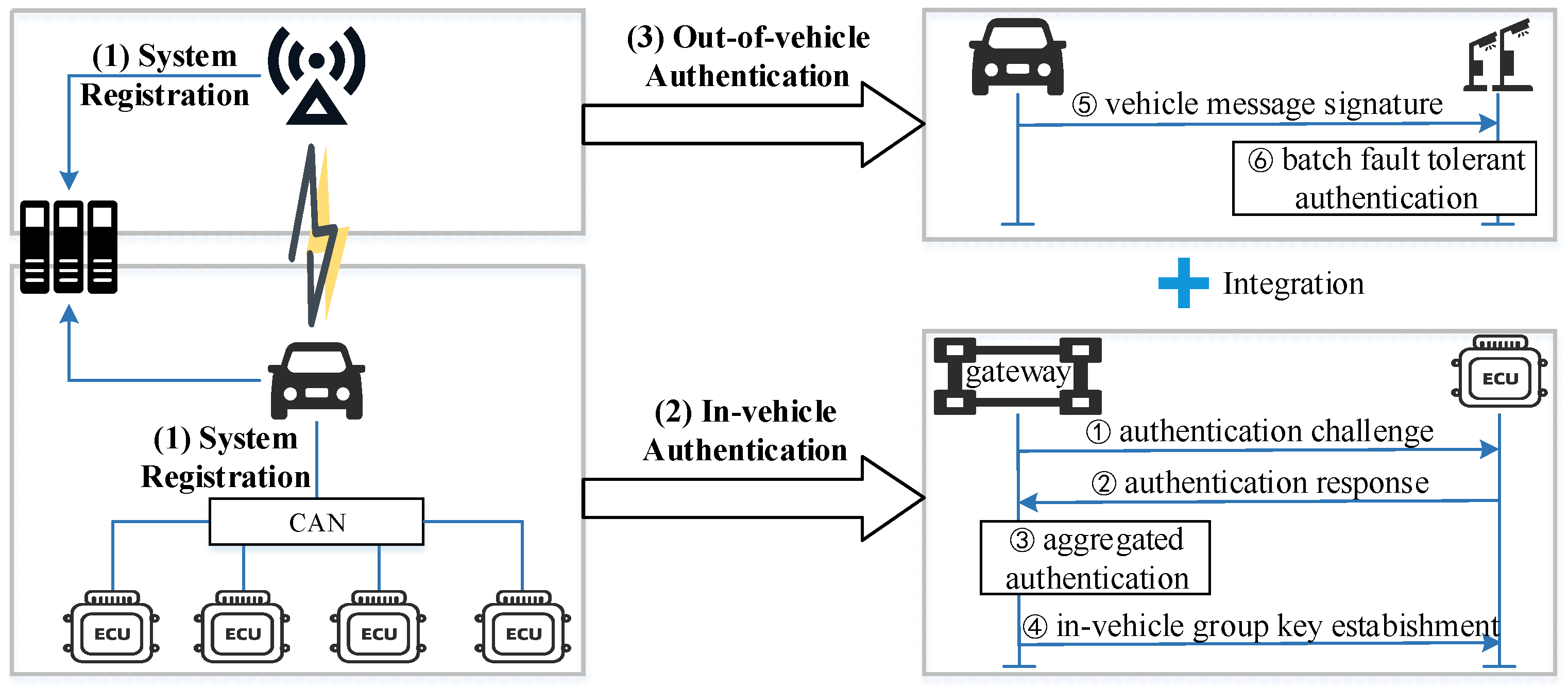

- Established integrated in-vehicle and out-of-vehicle authentication, guaranteeing end-to-end security for the perception data flow from ECUs to the RSU. This is accomplished by, firstly, employing PUF challenge–response pairs to generate unique hardware-based identities for ECUs and implementing a group key agreement protocol via a non-overlapping clustering technique for the in-vehicle phase. Then, for out-of-vehicle communication, the TPD is utilized to generate vehicle pseudonyms, and the same non-overlapping clustering technique is leveraged to achieve efficient and fault-tolerant batch authentication of messages from multiple vehicles.

- Achieved efficient batch authentication with inherent fault tolerance, thereby solving the “all-or-nothing” verification problem in traditional approaches where a single invalid message causes the entire batch to fail. By utilizing the non-overlapping clustering technique, the authentication codes from ECUs are grouped and aggregated. This allows for the rapid identification of illegitimate nodes through batch verification. Similarly, during the out-of-vehicle communication phase, the RSU employs the same technique to group message signatures from multiple vehicles. Invalid signatures are handled through fault-tolerant verification of smaller sub-batches, meaning only the failed group needs re-verification instead of the entire batch.

- Security and Practicality. Security analysis demonstrates that the proposed scheme can resist various attacks defined in the threat model. Extensive simulations and performance evaluations confirm its high efficiency and practical utility.

2. Related Work

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Notation

3.2. Cryptographic Primitive

3.2.1. Group

- Closure: For all , the result of the operation also belongs to G.

- Associativity: For all , the equation holds.

- Identity Element: There exists an element such that for every element , the equations and hold.

- Inverse Element: For each , there exists an element such that , where e is the identity element.

3.2.2. Elliptic Curve Cryptography

- Addition/Subtraction (+/−). Let P and Q be two points in .

- If , then , where R is the reflection over the x-axis of the third point of intersection between the curve E and the line connecting P and Q.

- If , then , where R is the reflection over the x-axis of the second point of intersection between the curve E and the tangent line at point P (or Q).

- If , then .

- Scalar Multiplication. Let and . Scalar multiplication over the group is defined as

3.2.3. Chinese Remainder Theorem

3.2.4. Hardness Assumption

3.3. Physically Unclonable Functions

3.3.1. Physically Unclonale Functions

- A response to a challenge gives negligible information to another response, , where .

- Without physically having the PUF-device, it is infeasible to generate , where .

- If an adversary, , tampers with the PUF-device, the PUF function is destroyed.

3.3.2. Noisy PUFs and Fuzzy Extractors

- : Inputting a challenge C, a key R, and auxiliary data are generated. is a vector generated by the original output and a linear-error-correction-code.

- : Inputting the challenge C and helper-data string , key R is refactored using error-decoding algorithm.

3.4. Message Authentication Code

- GenKey(): given a ecurity parameter , output a secret key k.

- Auth(): given a message m and a secret key k, output a MAC .

- Verify(): given a message m, a MAC and a secret key k, output 1 if m is correct, and 0 otherwise.

3.5. Cover-Free Family

- b represents the number of blocks (in our scheme, it refers to the number of blocks into which the messages participating in authentication are divided), and n represents the total number of base points (in our scheme, it refers to the total number of messages participating in authentication).

- If the j-th base point is assigned to the i-th block, then ; otherwise .

- For any different indices , there exists at least one row i such that and .

4. System Overview

4.1. System Model

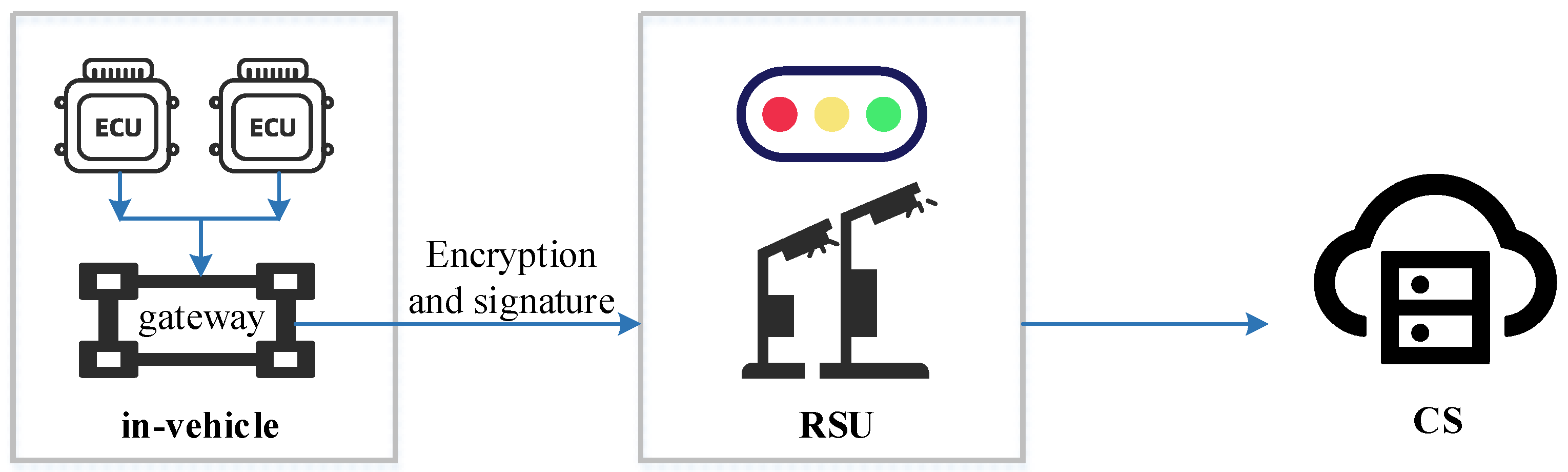

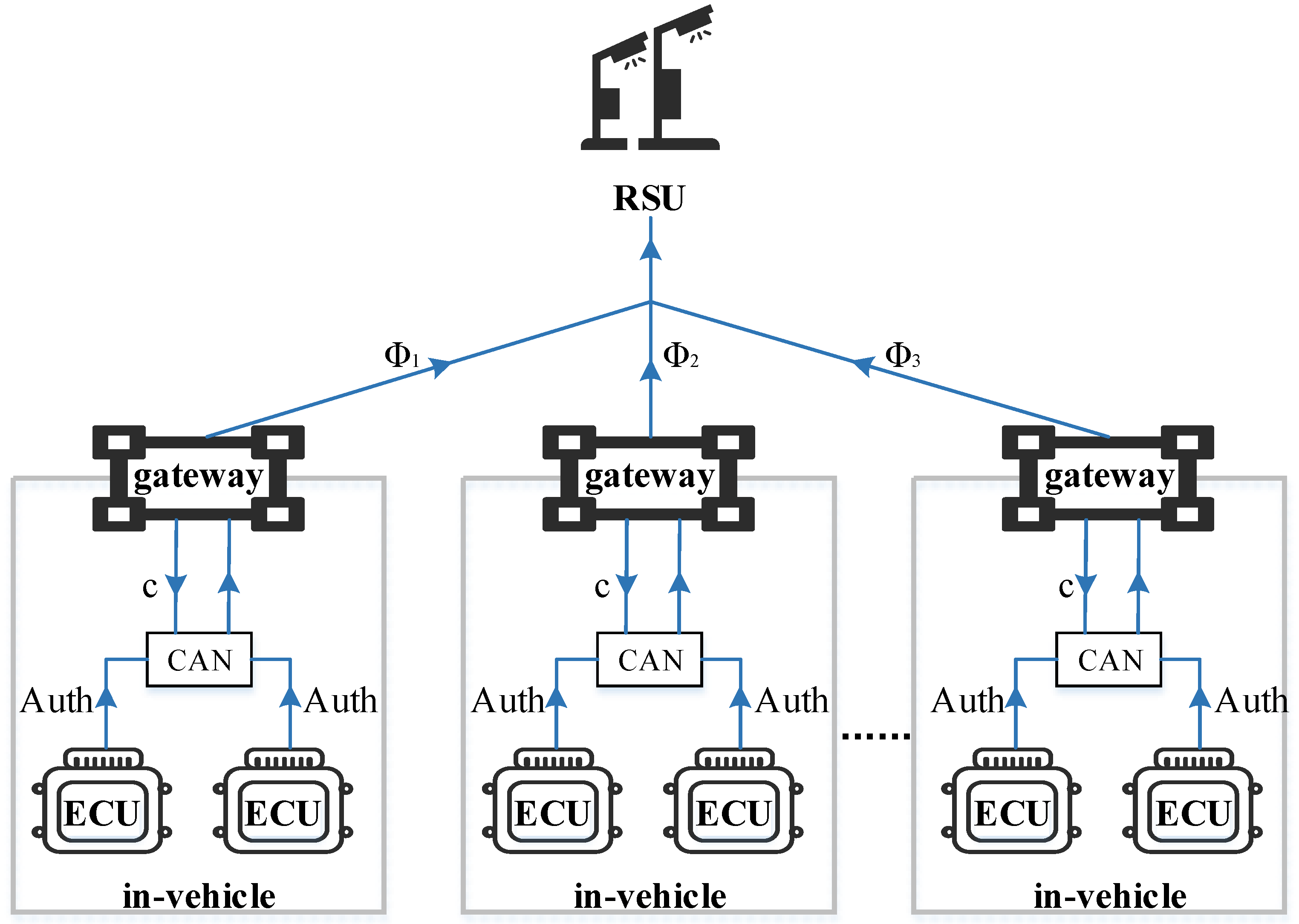

- ECUs. Each ECU is embedded with a PUF and stores a large number of CRPs. Upon receiving a challenge value from the gateway, the ECU uses the corresponding PUF response to compute its respective authentication code, which is then returned to the gateway.

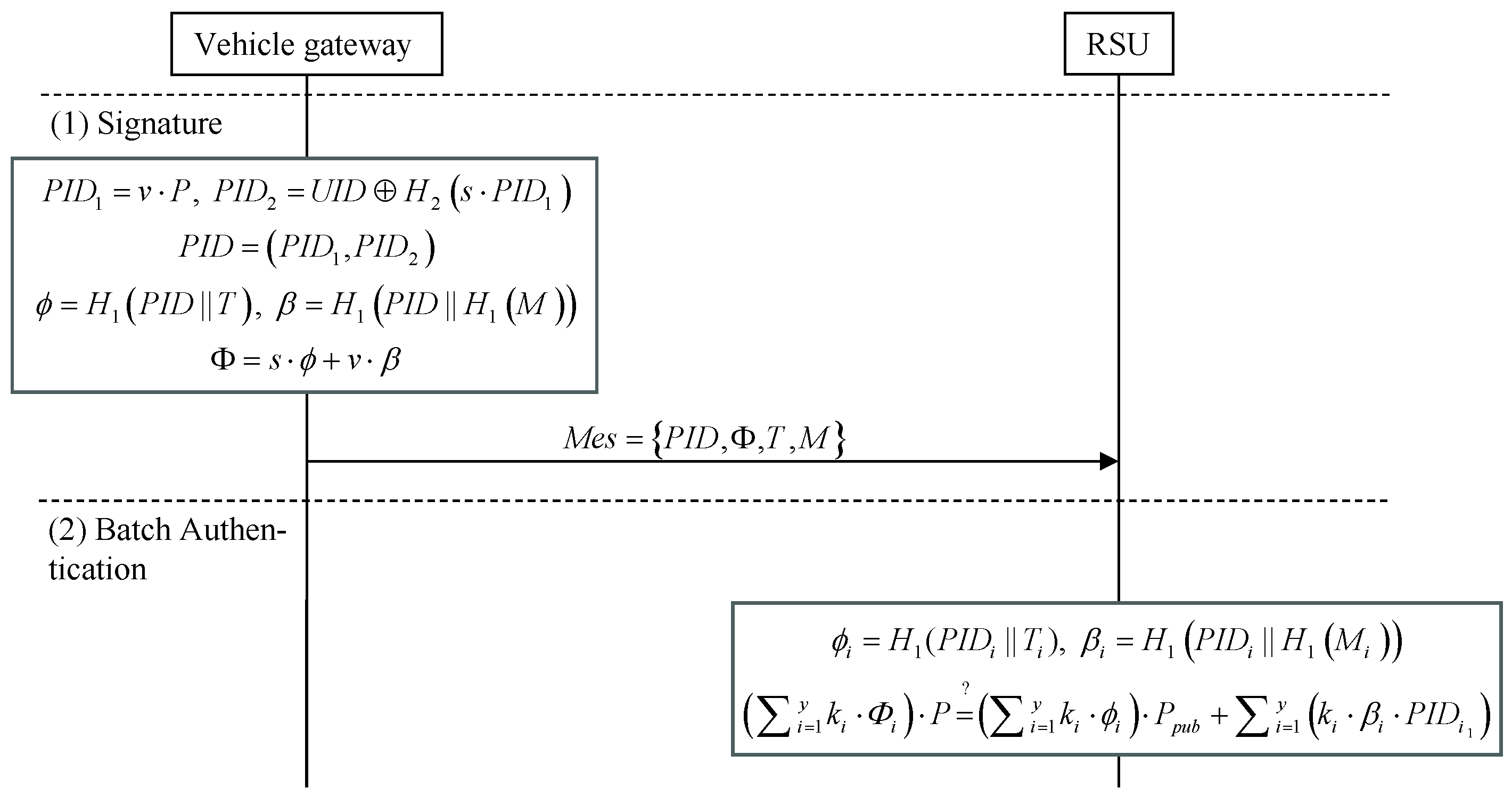

- Vehicle gateway. Acting as a secure hub between the in-vehicle network and the out-of-vehicle network, the vehicle gateway embedded with TPD is responsible for efficient batch authentication of in-vehicle ECUs and group key distribution. It broadcasts PUF challenge values to the ECUs, verifies the aggregated authentication codes received from the ECUs, and after successful authentication, distributes group key to the ECUs using the CRT. Simultaneously, it generates pseudonyms on behalf of the vehicle and transmits encapsulated perception data to the RSU.

- RSU. After receiving a large number of vehicle messages, the RSU performs fault-tolerant batch authentication. Even if a small number of illegitimate vehicle messages are received, the RSU can swiftly complete the authentication of vehicle messages and identify the source of illegitimate data. However, RSU cannot trace the real identity of vehicles based on the received messages.

4.2. Threat Model

4.3. Security Model

- Integrity and authenticity. No probabilistic polynomial-time (PPT) adversary can forge a valid in-vehicle MAC or an external signature with non-negligible probability.

- Fault-tolerant batch authentication. For most k-corrupted messages, the misbehaving set is uniquely identified with a failure probability no higher than , where is negligible.

- Conditional anonymity. Vehicle pseudonyms must be unlinkable without the master key.

- EU-CMA security. External signatures must resist existential forgery under chosen-message attacks.

5. Scheme Construction

5.1. Overview

5.2. Workflow of UFTBA

5.3. Concrete Construction

5.3.1. System Initialization

5.3.2. In-Vehicle Authentication and Group Key Agreement

5.3.3. Anonymous Batch Authentication for External Vehicular Messages

6. Scheme Analysis

6.1. Correctness Analysis

6.1.1. Correctness of the External Authentication Signature Verification Equation

6.1.2. Correctness of the Vehicle Tracing Formula

6.1.3. Correctness of the In-Vehicle CRT-Based Key Distribution

6.2. Security Analysis

6.2.1. Unforgeability of External Message Authentication

- The signature is a valid signature for the message under the public key .

- The message was never submitted by during the signing queries, i.e., , where q is the total number of queries.

6.2.2. Detection and Localization Guarantees of Aggregate MAC + k-CFF

6.2.3. Conditional Privacy Preservation

6.2.4. Forward Secret

6.2.5. Replay Attack

6.3. Performance Analysis

6.3.1. Computational Complexity

6.3.2. Experimental Results and Analysis

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Pseudocode of the Auth in in In-Vehicle Authentication and Group Key Agreement

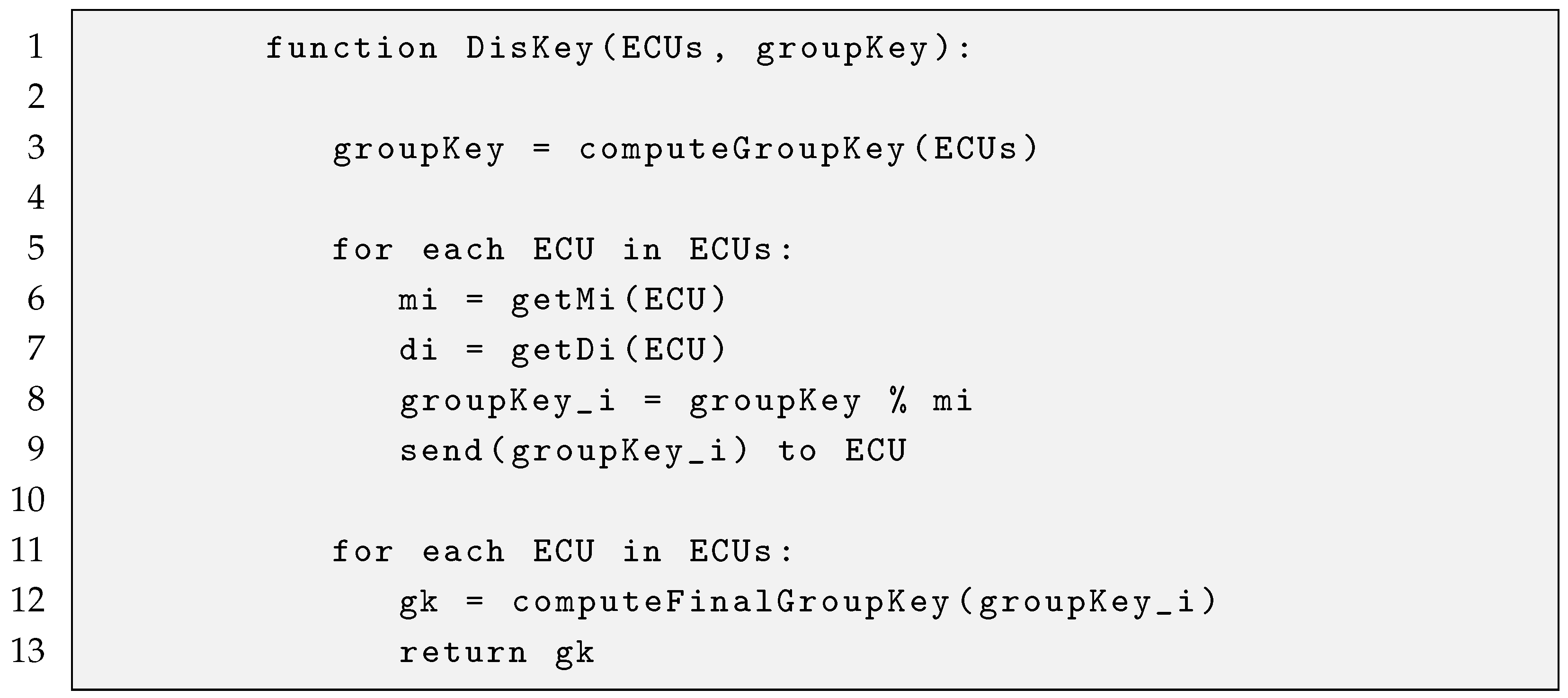

Appendix A.2. Pseudocode of the DisKey in In-Vehicle Authentication and Group Key Agreement

Appendix A.3. Pseudocode of the Sig in Anonymous Batch Authentication for External Vehicular Messages

Appendix A.4. Pseudocode of the Trace in Anonymous Batch Authentication for External Vehicular Messages

References

- Alkhatib, A.A.; Maria, K.A.; AlZu’bi, S.; Maria, E.A. Smart traffic scheduling for crowded cities road networks. Egypt. Inform. J. 2022, 23, 163–176. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Pei, X.; Feng, S.; Li, L. Fault-tolerant cooperative driving at signal-free intersections. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2022, 8, 121–134. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao, Z.; Shu, J.; Jiang, H.; Min, G.; Chen, H.; Han, Z. Overcoming occlusions: Perception task-oriented information sharing in connected and autonomous vehicles. IEEE Netw. 2023, 37, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, R.; Liu, X.; Ma, J.; Chi, Z.; Ma, J.; Yu, H. Learning for vehicle-to-vehicle cooperative perception under lossy communication. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 8, 2650–2660. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Li, C.; Ng, D.W.K.; Eldar, Y.C.; Poor, H.V.; Hao, Q.; Xu, C. Federated deep learning meets autonomous vehicle perception: Design and verification. IEEE Netw. 2022, 37, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, K.; Wang, T.; Tong, L.; Fang, X.; Pan, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, J. Non-intrusive security assessment methods for future autonomous transportation IoV. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2023, 21, 2387–2399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, S.B.; Adil, M.; Ali, A.; Farouk, A.; Song, H.H. Internet of Vehicles Security Threats, Countermeasures, Open Challenges With Future Research Directions. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 46347–46374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, S.; Su, H.; Yuan, J.X.; Zhu, F.; Hu, X.; Wang, B. A comprehensive survey on authentication and attack detection schemes that threaten it in vehicular ad-hoc networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 13573–13602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhu, H.; Ning, Z.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y. Blockchain intelligence for internet of vehicles: Challenges and solutions. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2023, 25, 2325–2355. [Google Scholar]

- Agbaje, P.; Anjum, A.; Mitra, A.; Oseghale, E.; Bloom, G.; Olufowobi, H. Survey of interoperability challenges in the internet of vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 22838–22861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathore, R.S.; Hewage, C.; Kaiwartya, O.; Lloret, J. In-vehicle communication cyber security: Challenges and solutions. Sensors 2022, 22, 6679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chellapandi, V.P.; Yuan, L.; Brinton, C.G.; Żak, S.H.; Wang, Z. Federated learning for connected and automated vehicles: A survey of existing approaches and challenges. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2023, 9, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotto, A.; Marchiori, F.; Brighente, A.; Conti, M. A survey and comparative analysis of security properties of can authentication protocols. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2024, 27, 2470–2504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Gong, B.; Waqas, M.; Tu, S.; Chen, S. Many-objective optimization based intrusion detection for in-vehicle network security. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 15051–15065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Dai, J.; Huang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Zeng, G.; Li, R. A digital watermark method for in-vehicle network security enhancement. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 8398–8408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manasrah, A.; Yaseen, Q.; AI-Aqrabi, H.; Liu, L. Identity-based authentication in vanets: A review. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2025, 26, 4260–4282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douss, A.B.C.; Abassi, R.; Sauveron, D. State-of-the-art survey of in-vehicle protocols and automotive Ethernet security and vulnerabilities. Math. Biosci. Eng. 2023, 20, 17057–17095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levy, E.; Shabtai, A.; Groza, B.; Murvay, P.S.; Elovici, Y. CAN-LOC: Spoofing detection and physical intrusion localization on an in-vehicle CAN bus based on deep features of voltage signals. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2023, 18, 4800–4814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, G.K.; Rana, S.; Tiwari, A.; Kumar, N.; Barnawi, A. Dynamic Anonymous Hierarchical Edge-Assisted Batch Verifiable Authentication for VANETs. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 14735–14744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, C.; Chen, X.; Fan, W.; Liu, Y. Batch-assisted verification scheme for reducing message verification delay of the vehicular ad hoc networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2020, 7, 8144–8156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Kim, Y.J.; Piao, Z.; Chung, J.G.; Kim, Y.E. Security protocol for controller area network using ECANDC compression algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Signal Processing, Communications and Computing (ICSPCC), Chengdu, China, 6–9 November 2016; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson, D.K.; Larson, U.E.; Jonsson, E. Efficient in-vehicle delayed data authentication based on compound message authentication codes. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE 68th Vehicular Technology Conference, Calgary, Canada, 21–24 September 2008; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, S.; Jo, H.J.; Kim, I.S.; Lee, D.H. A practical security architecture for in-vehicle CAN-FD. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 17, 2248–2261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murvay, P.S.; Groza, B. Source identification using signal characteristics in controller area networks. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2014, 21, 395–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, W.; Jo, H.J.; Woo, S.; Chun, J.Y.; Park, J.; Lee, D.H. Identifying ECUs using inimitable characteristics of signals in controller area networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2018, 67, 4757–4770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asghar, M.; Doss, R.R.M.; Pan, L. A scalable and efficient PKI based authentication protocol for VANETs. In Proceedings of the 2018 28th International Telecommunication Networks and Applications Conference (ITNAC), Auckland, New Zealand, 21–23 November 2018; pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Wu, Q.; Domingo-Ferrer, J.; Qin, B.; Hu, C. Distributed aggregate privacy-preserving authentication in VANETs. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2016, 18, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhong, H.; Xu, Y. SPACF: A secure privacy-preserving authentication scheme for VANET with cuckoo filter. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2017, 66, 10283–10295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, N.W.; Tsai, J.L. An efficient conditional privacy-preserving authentication scheme for vehicular sensor networks without pairings. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2015, 17, 1319–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cui, J.; Zhong, H.; Chen, Z.; Liu, L. PA-CRT: Chinese remainder theorem based conditional privacy-preserving authentication scheme in vehicular ad-hoc networks. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2019, 18, 722–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.; Ma, J.; Wang, X.; Zhou, H.; Zheng, D. A novel authentication and key agreement scheme for in-vehicle networks. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 9630–9644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurya, C.; Chaurasiya, V.K. Efficient anonymous batch authentication scheme with conditional privacy in the Internet of Vehicles (IoV) applications. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 24, 9670–9683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, S.K.; Amin, R.; Vollala, S.; Das, A.K. Design of blockchain and ECC-based robust and efficient batch authentication protocol for vehicular ad-hoc networks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 25, 275–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Q.; Zhao, X.; Xia, Y.; Liu, X. CD-BASA: An efficient cross-domain batch authentication scheme based on blockchain with accumulator for VANETs. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 14560–14571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.B.; Xie, Y.; Zhang, Y.B. Efficient and secure message authentication scheme for VANET. J. Commun. 2016, 37, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Koblitz, N. Elliptic curve cryptosystem. J. Math. Commun. 1987, 48, 203–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.W.; Liu, X.S.; Cheng, Z. Quantum secret sharing with graph states based on Chinese remainder theorem. J. Commun. 2018, 39, 72–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakkar, M.; AlTawy, R.; Youssef, A. Lightweight group authentication scheme Leveraging Shamir’s secret sharing and PUFs. IEEE Trans. Netw. Sci. Eng. 2024, 11, 3412–3429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Su, Y.; Xu, L.; Ranasinghe, D.C. Lightweight (reverse) fuzzy extractor with multiple reference PUF responses. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2018, 14, 1887–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Herrewege, A.; Katzenbeisser, S.; Maes, R.; Peeters, R.; Sadeghi, A.R.; Verbauwhede, I.; Wachsmann, C. Reverse fuzzy extractors: Enabling lightweight mutual authentication for PUF-enabled RFIDs. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, Berlin, Germany, 27 February–2 March 2012; pp. 374–389. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Zhang, Q.; Weimerskirch, A.; Mao, Z.M. Gatekeeper: A gateway-based broadcast authentication protocol for the in-vehicle Ethernet. In Proceedings of the 2022 ACM on Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Nagasaki, Japan, 30 May–3 June 2022; pp. 494–507. [Google Scholar]

| Technique | Unified Authentication | Fault Tolerance | Vehicle Privacy Information Protection | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [31] | SRAM PUF and MAC | × 1 | - | - |

| [15] | Digital Watermark and Huffman Coding | × | - | - |

| [32] | ECC | × | × | √ 2 |

| [33] | Blockchain and ECC | × | × | √ |

| [34] | Blockchain and Accumulator | × | × | √ |

| Ours | PUF and MAC and CRT | √ | √ | √ |

| Notations | Description |

|---|---|

| Unique identity of vehicle | |

| Pseudonym of vehicle | |

| The CRPs for | |

| The authentication code of | |

| The aggregated authentication code for in the group | |

| The signature of vehicle |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Ren, Z.; Wang, P. A Unified Fault-Tolerant Batch Authentication Scheme for Vehicular Networks. Electronics 2025, 14, 4973. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244973

Zhao Y, Liu H, Li X, Wang Y, Ren Z, Wang P. A Unified Fault-Tolerant Batch Authentication Scheme for Vehicular Networks. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4973. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244973

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Yifan, Hu Liu, Xinghua Li, Yunwei Wang, Zhe Ren, and Peiyao Wang. 2025. "A Unified Fault-Tolerant Batch Authentication Scheme for Vehicular Networks" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4973. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244973

APA StyleZhao, Y., Liu, H., Li, X., Wang, Y., Ren, Z., & Wang, P. (2025). A Unified Fault-Tolerant Batch Authentication Scheme for Vehicular Networks. Electronics, 14(24), 4973. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244973