A Low-Power SNN Processor Supporting On-Chip Learning for ECG Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works and Background

2.1. Low-Power Design for ECG Monitoring

2.2. Learning Algorithms for ECG Monitoring

2.3. e-Prop Learning Algorithm

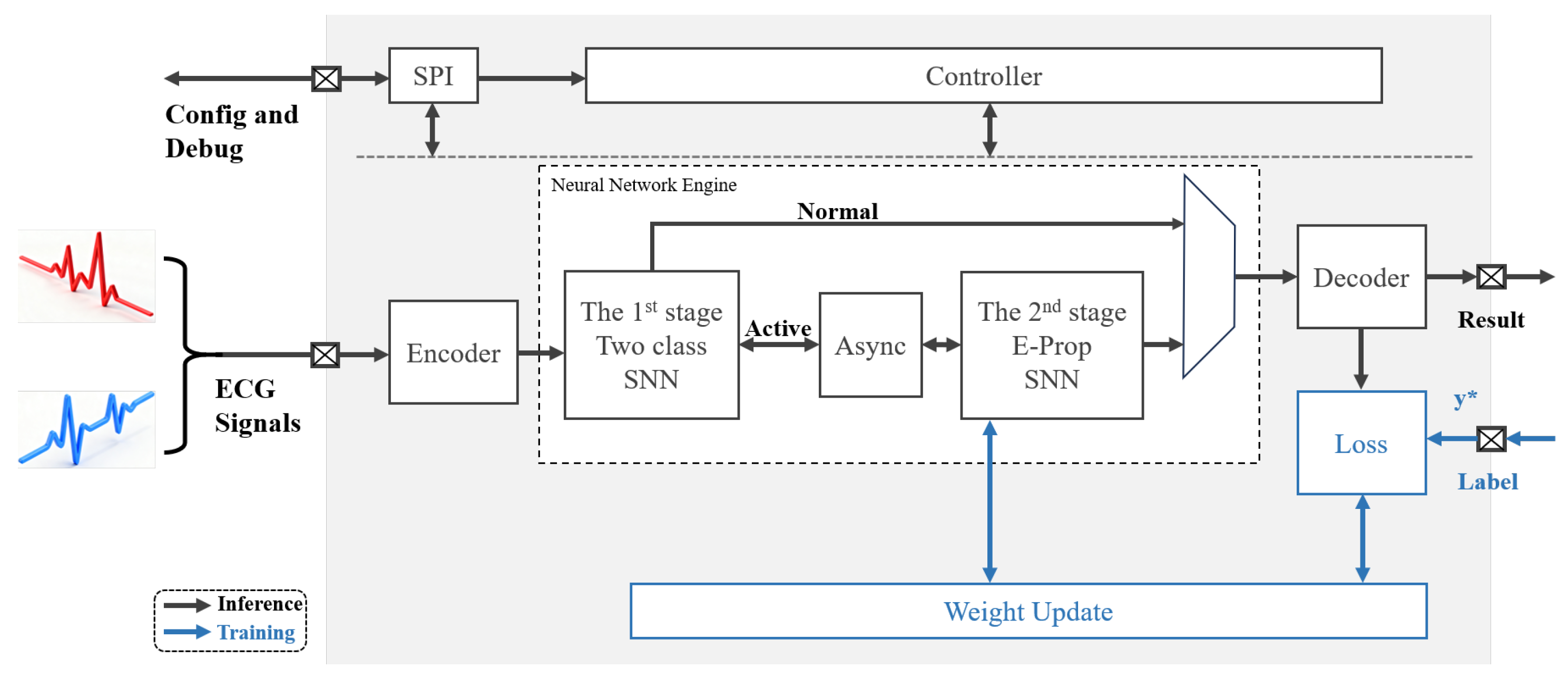

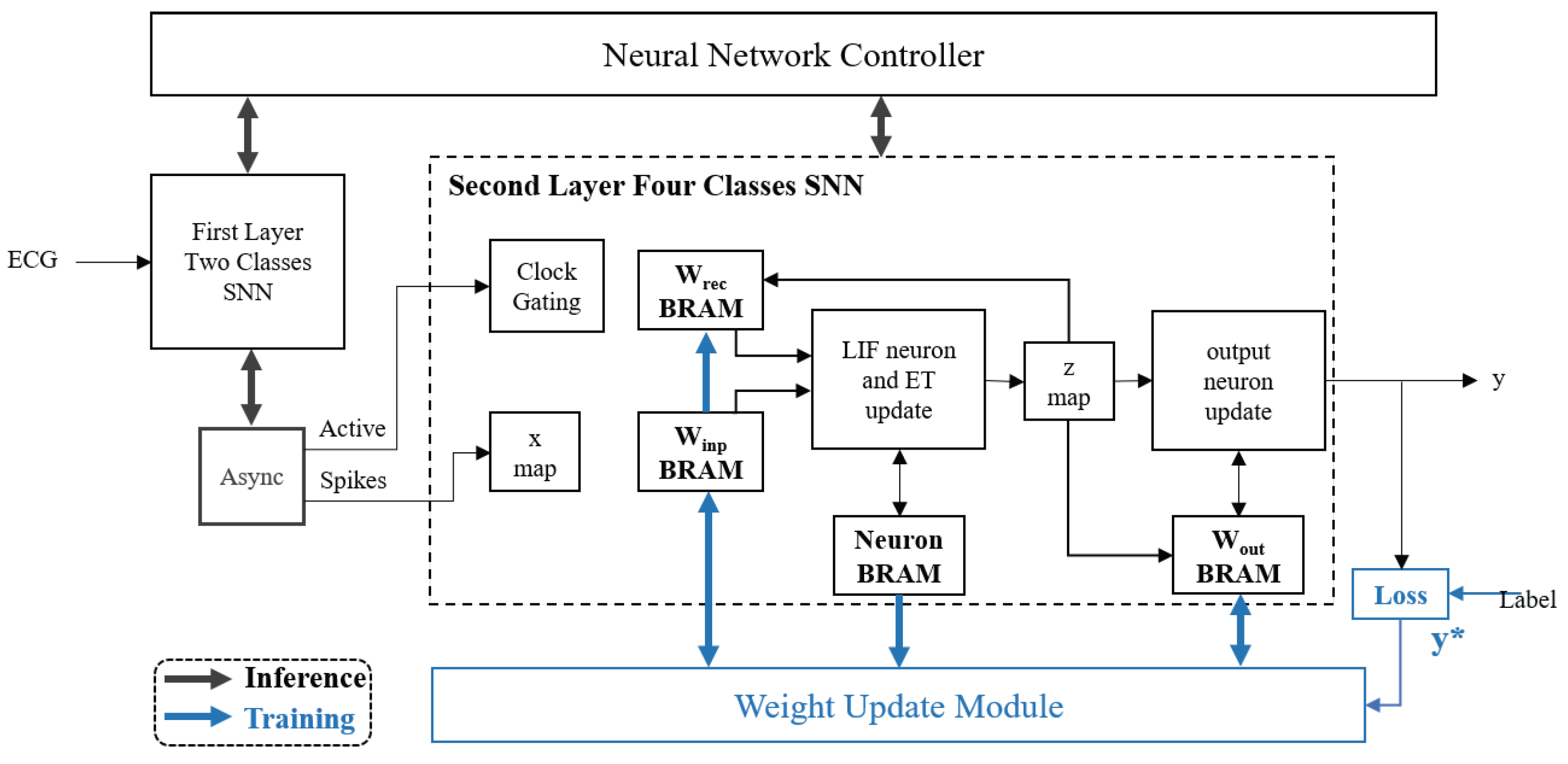

3. SNN Processor Overall Design

3.1. Overall Accelerator Design

3.2. Asynchronous Circuit Technology

3.2.1. Asynchronous Communication Design

3.2.2. Asynchronous Signal Interaction Based on Click Units

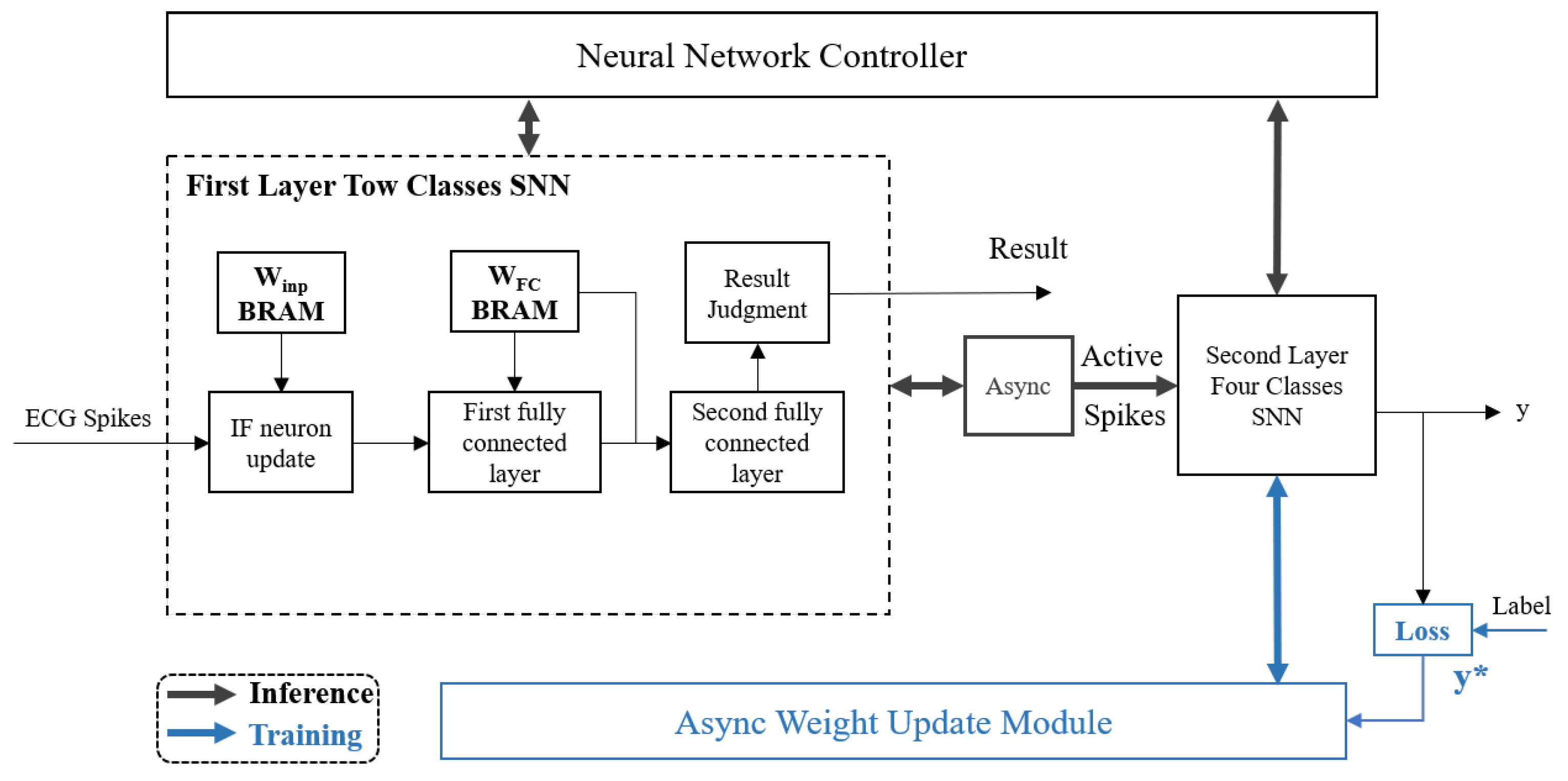

3.3. Design of SNN Two-Class Network

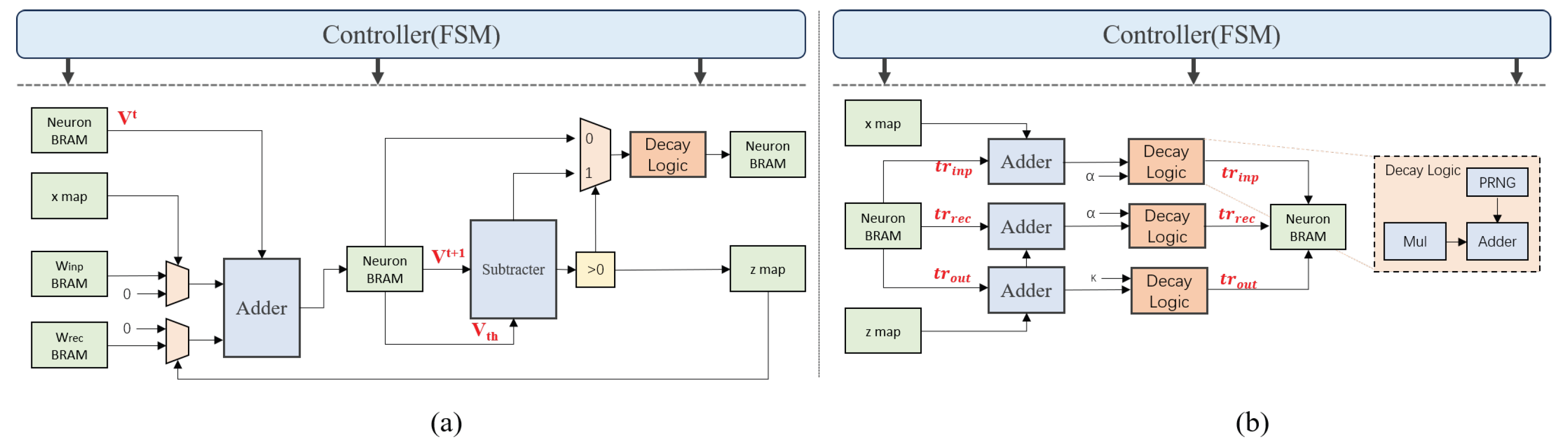

3.4. Design of Four-Class Network Based on e-Prop Algorithm

3.4.1. Forward Inference Design

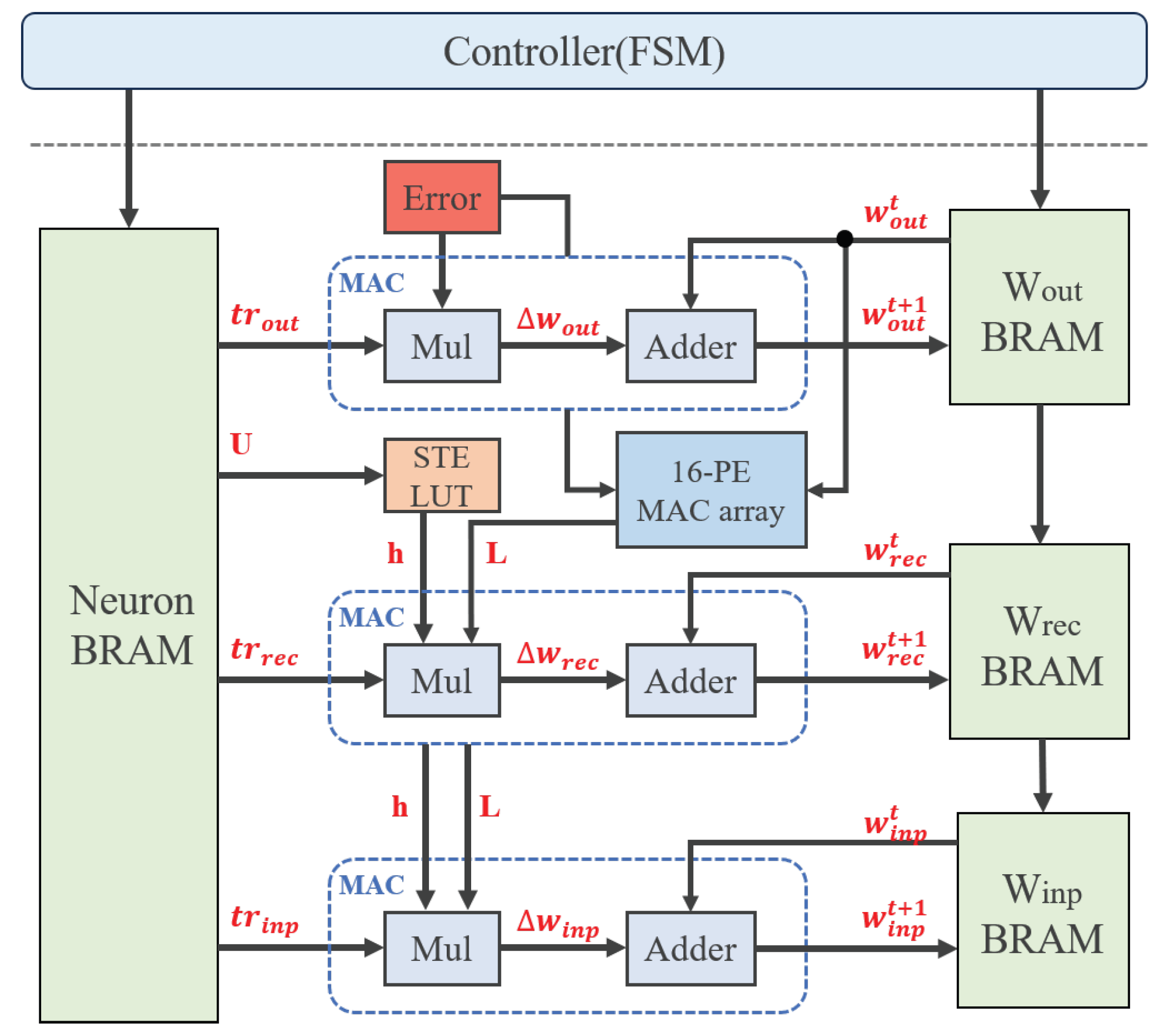

3.4.2. Weight Update Design

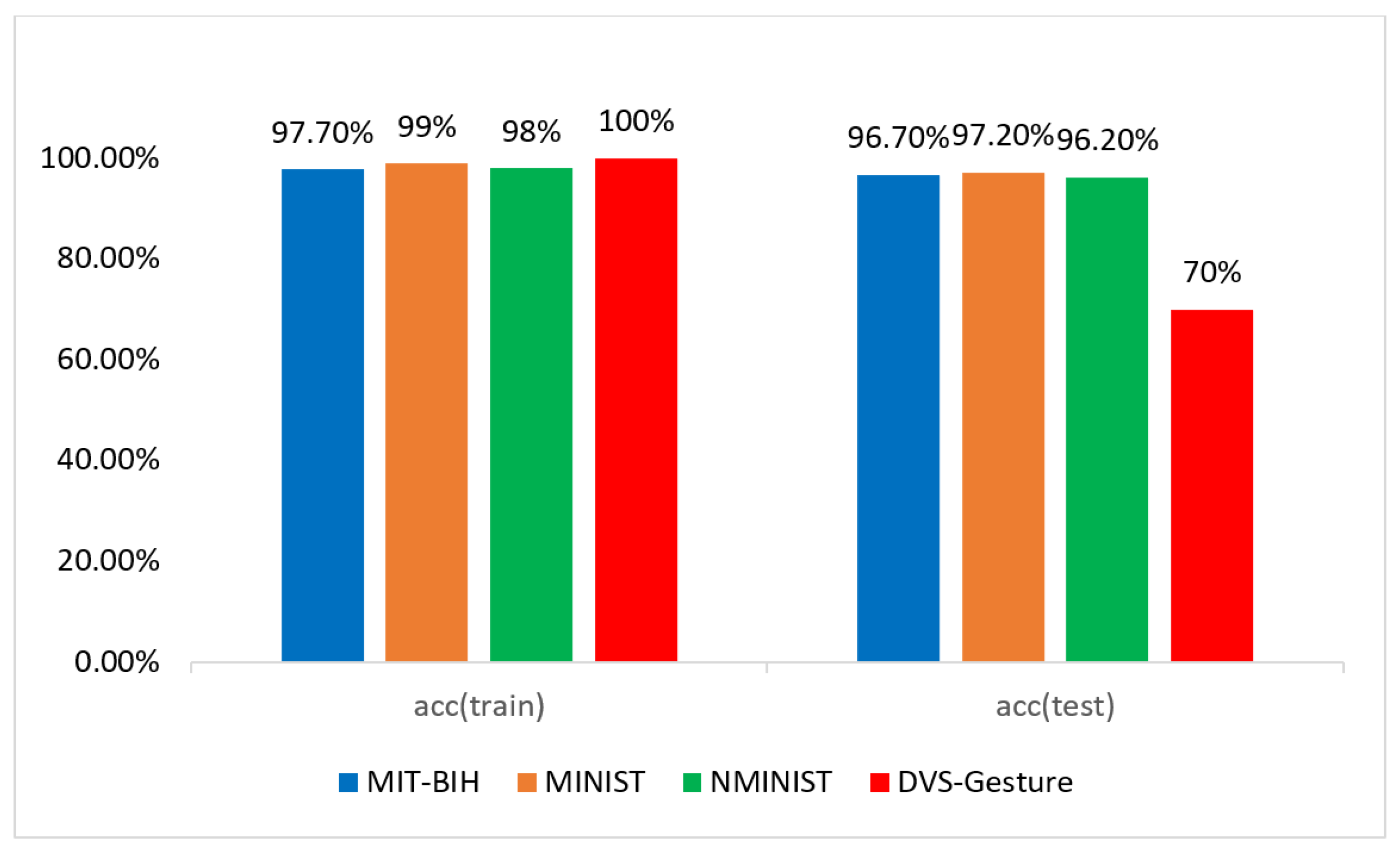

4. Experiments and Results

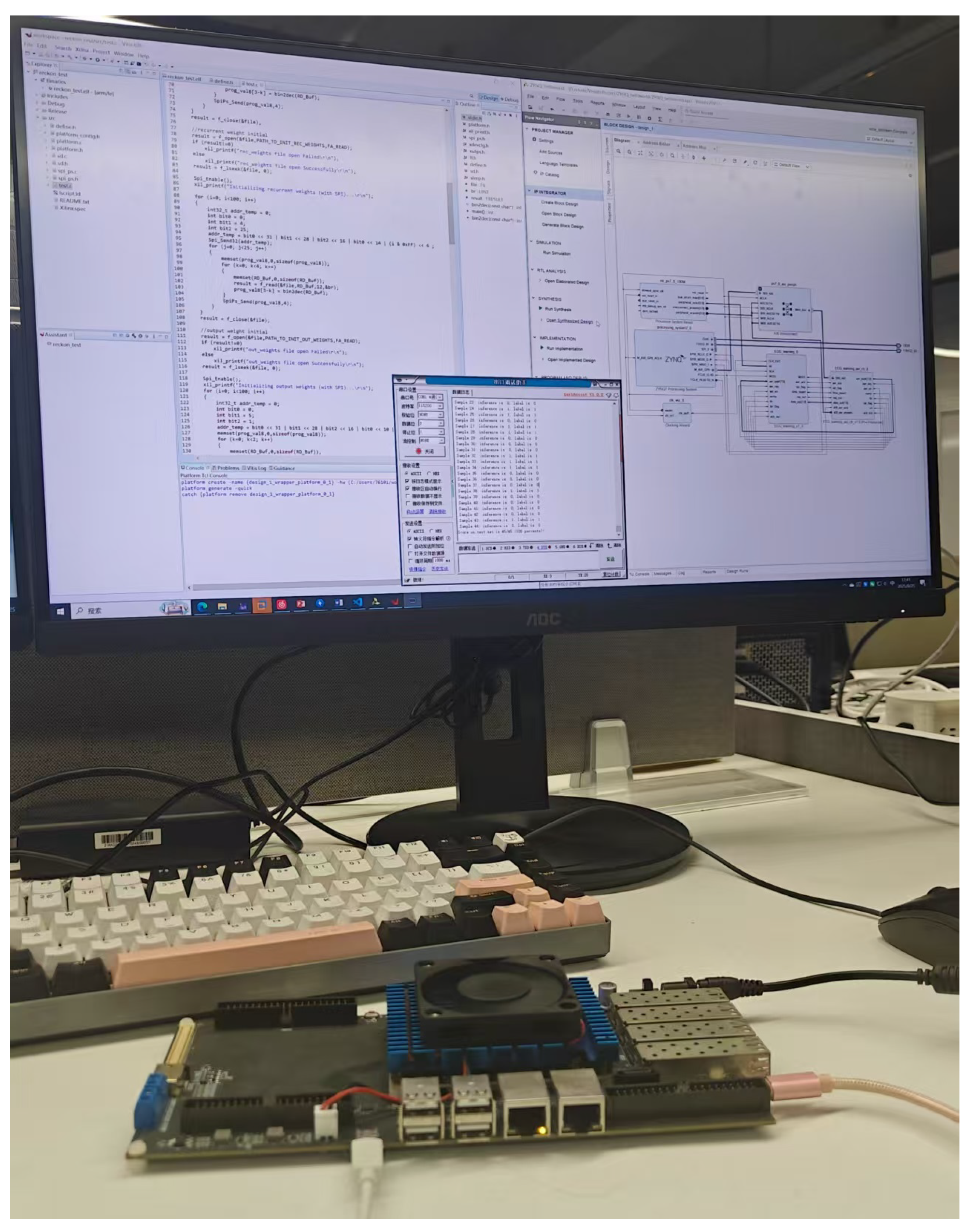

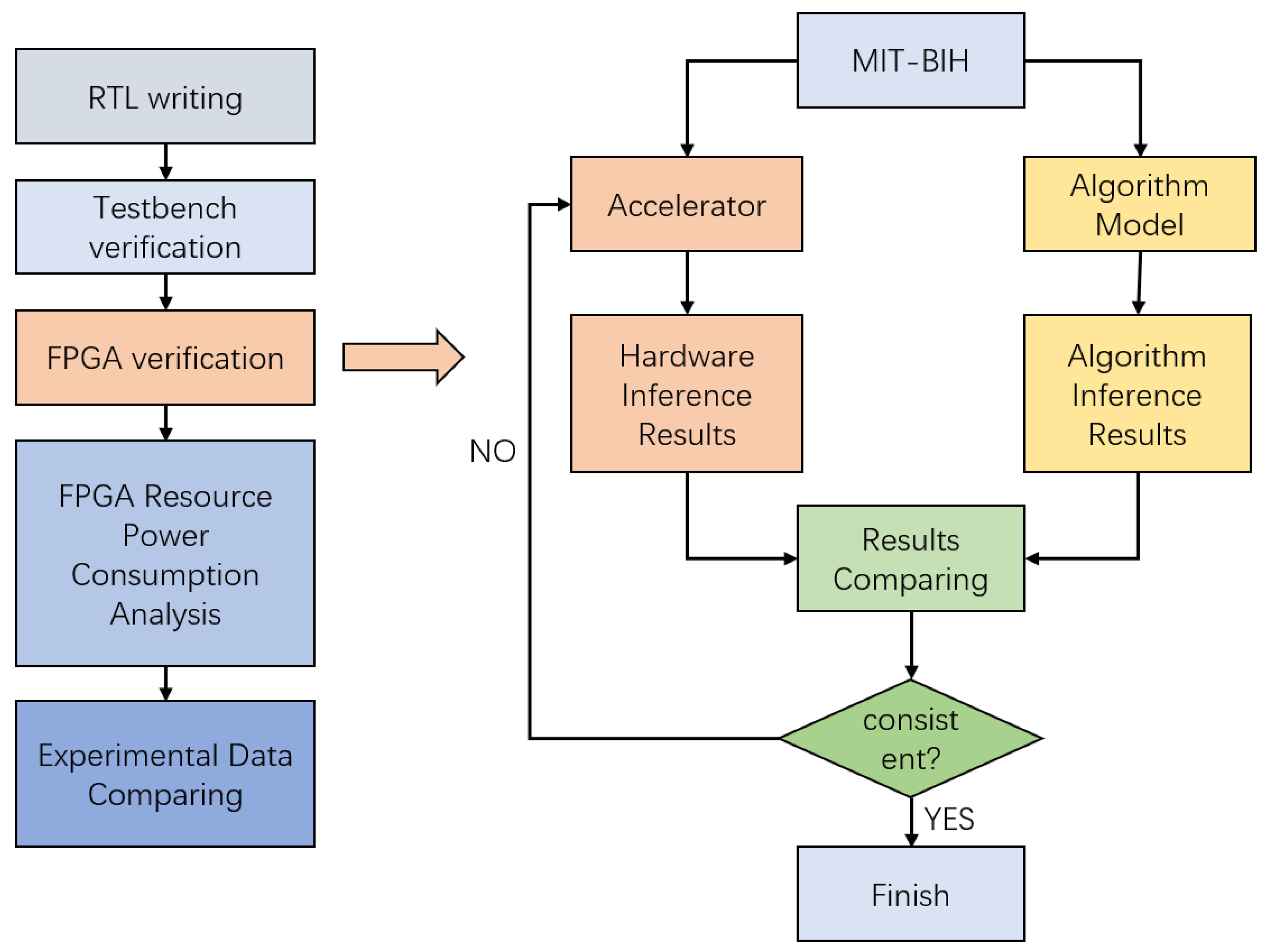

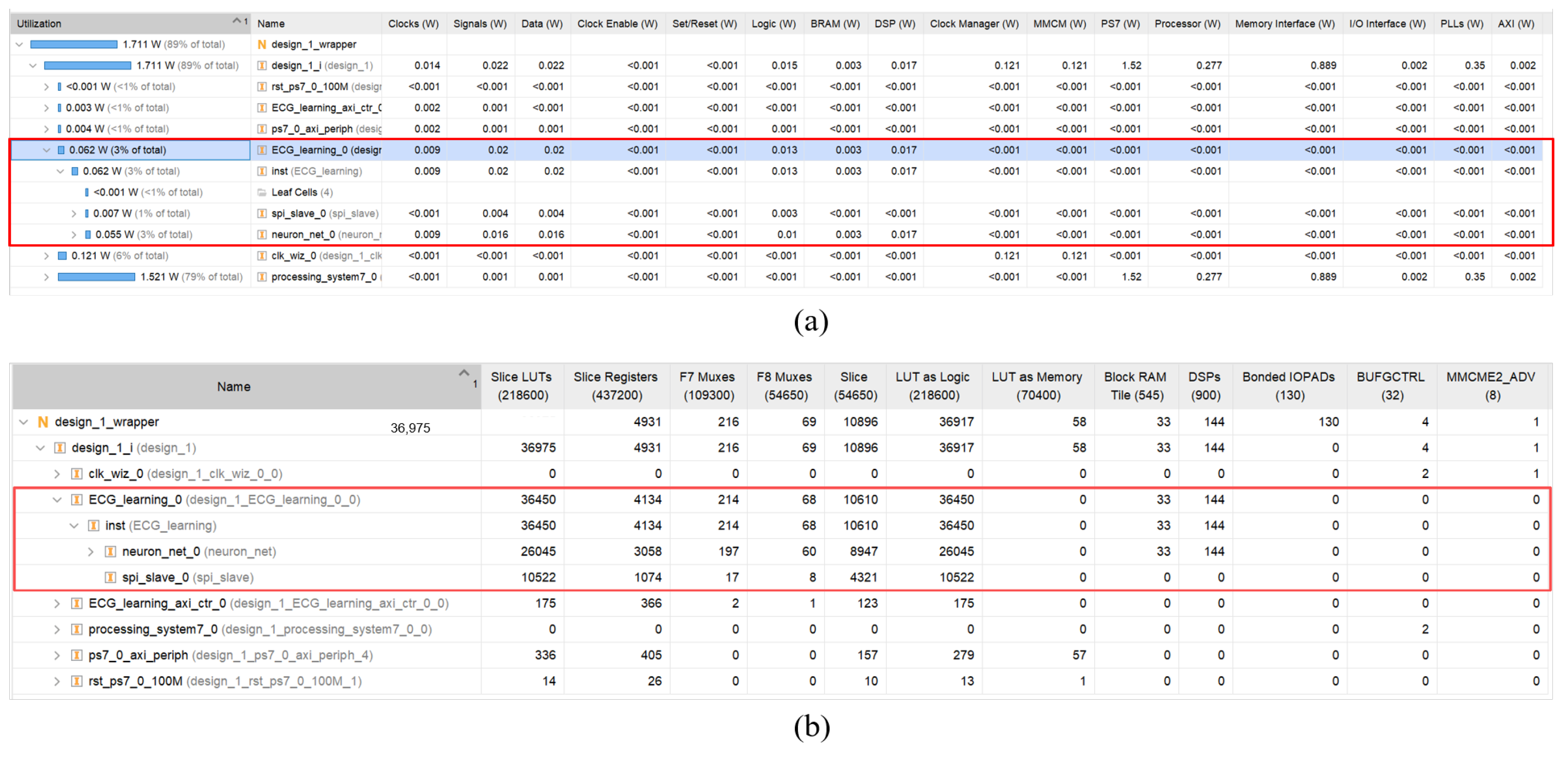

4.1. Experimental Implementation

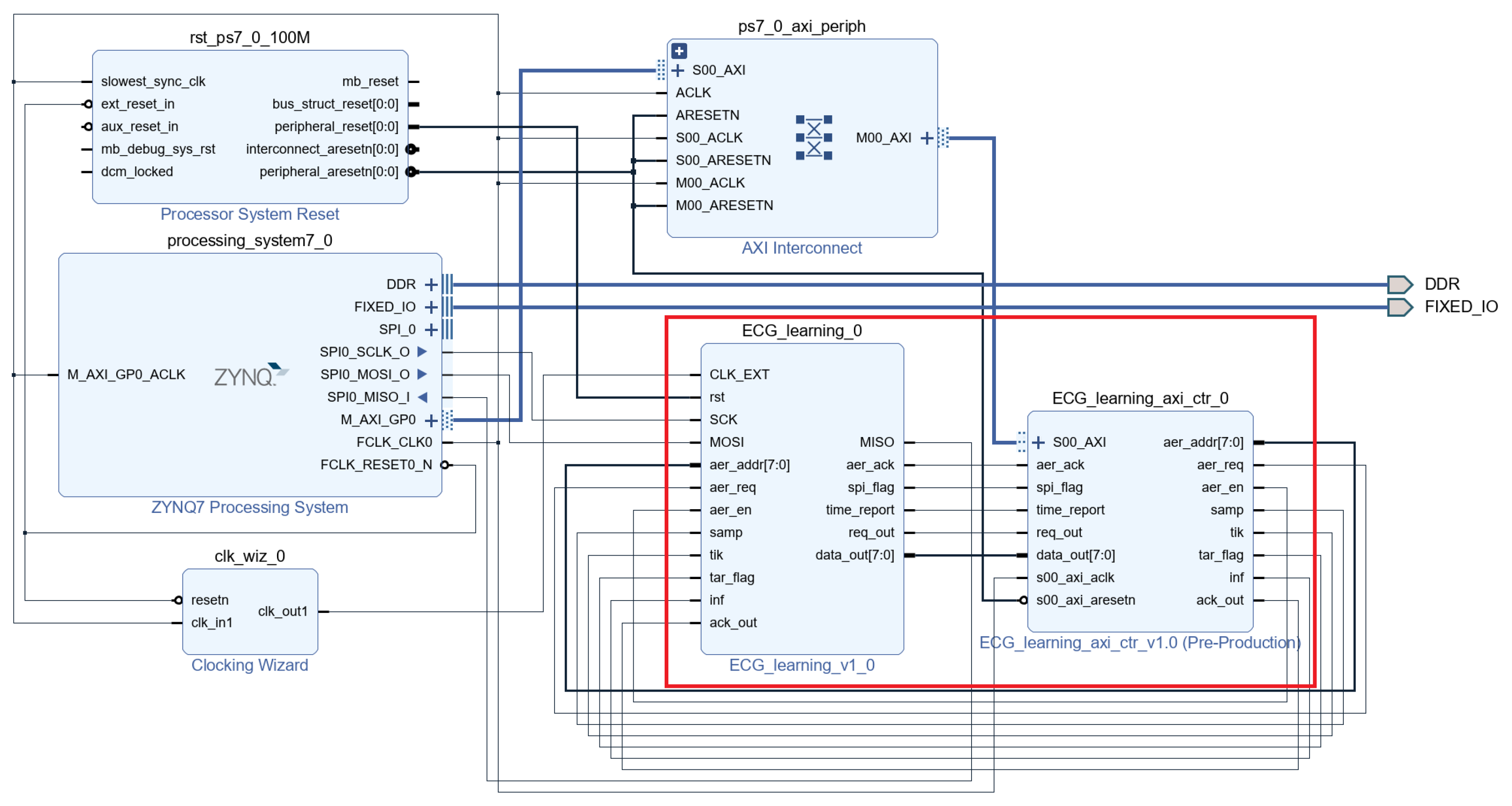

4.2. System Design and Module Integration

4.3. Results

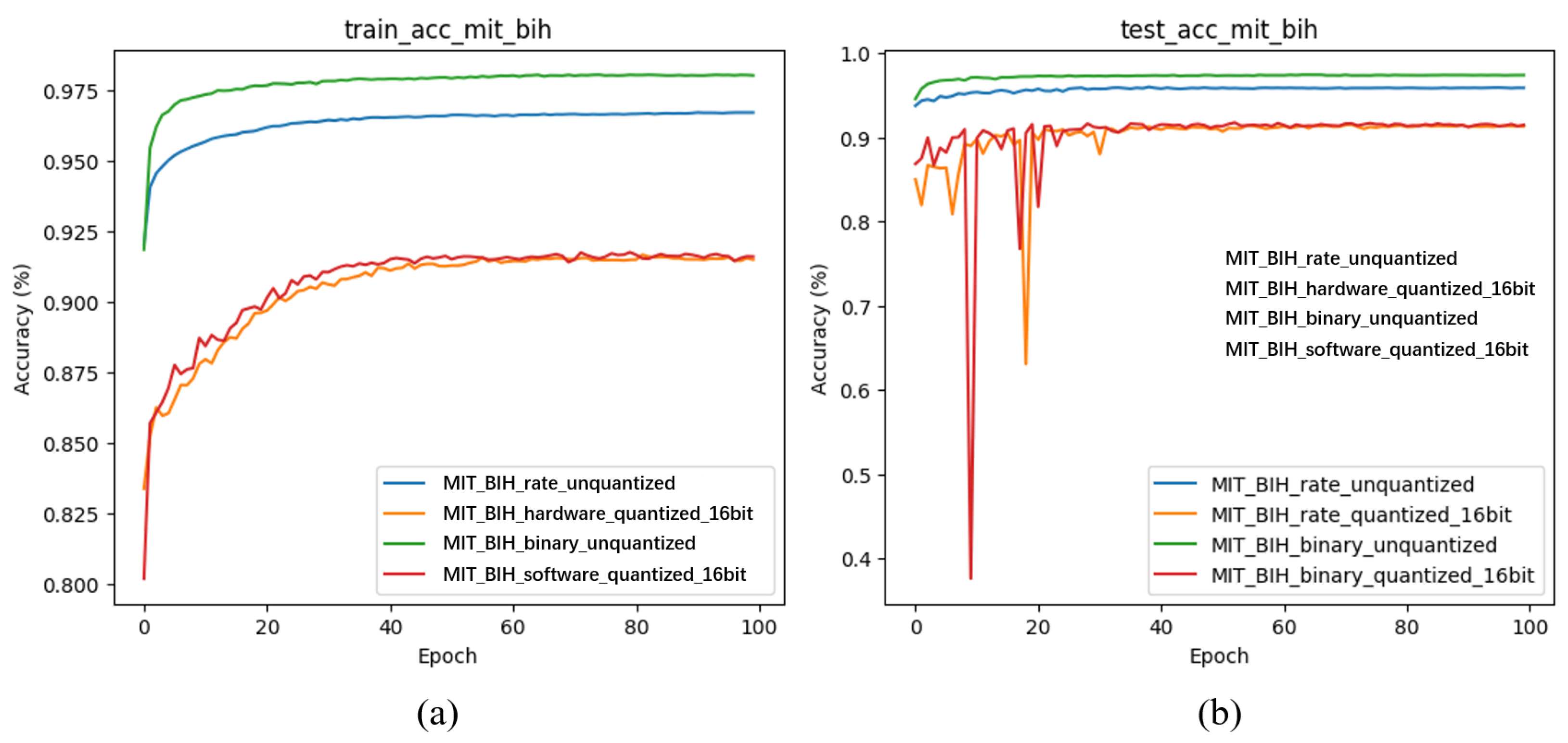

4.3.1. First-Stage Inference Evaluation

4.3.2. Learning Evaluation

4.3.3. Overall Inference Evaluation

4.3.4. Comparison with Other Chips

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiang, Z.; Han, M.; Zhang, H. Nanomaterials based flexible devices for monitoring and treatment of cardiovascular diseases (CVDs). Nano Res. 2023, 16, 3939–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ieong, C.I.; Mak, P.I.; Lam, C.P.; Dong, C.; Vai, M.I.; Mak, P.U.; Pun, S.H.; Wan, F.; Martins, R.P. A 0.83-μW QRS Detection Processor Using Quadratic Spline Wavelet Transform for Wireless ECG Acquisition in 0.35- μm CMOS. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2012, 6, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Raj, S. An Adaptive Scheme for Real-Time Detection of Patient-Specific Arrhythmias Using Single-Channel Wearable ECG Sensor. IEEE Sens. Lett. 2024, 8, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boumaiz, M.; Ghazi, M.E.; Bouayad, A.; Balboul, Y.; El Bekkali, M. Energy-Efficient Strategies in Wireless Body Area Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. IoT 2025, 6, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Hu, D. QRS Complex Detection Using Novel Deep Learning Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 97082–97089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Guan, Y.; Ye, W. An Energy-Efficient ECG Processor with Ultra-Low-Parameter Multistage Neural Network and Optimized Power-of-Two Quantization. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2024, 18, 1296–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzura, S.; Iancu, B.; Dadarlat, V.; Peculea, A.; Cebuc, E. Optimizations for Energy Efficiency in Software-Defined Wireless Sensor Networks. Sensors 2020, 20, 4779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, J.; Liu, D.; Cheng, X.; Wei, L.; Hu, A.; Zou, X. An Efficient Unstructured Sparse Convolutional Neural Network Accelerator for Wearable ECG Classification Device. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Regul. Pap. 2022, 69, 4572–4582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, R.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Xia, Z.; Xiao, J.; Zhu, Z.; Liu, J.; Shan, W.; Chang, L.; Zhou, J. An Ultra-Energy-Efficient and High Accuracy ECG Classification Processor with SNN Inference Assisted by On-Chip ANN Learning. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2022, 16, 832–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, M.; Wei, J.; Wei, S.; Chen, H. A 28 nm Configurable Asynchronous SNN Accelerator with Energy-Efficient Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 27th IEEE International Symposium on Asynchronous Circuits and Systems (ASYNC), Beijing, China, 7–10 September 2021; pp. 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, R.; Pei, X.; Luo, D.; Hussain, S.; Zhang, G. A Fast Spiking Neural Network Accelerator based on BP-STDP Algorithm and Weighted Neuron Model. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 2271–2275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, J.; Fan, J.; Liu, Q.; Zhu, Z.; Li, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, S.; Shan, W.; Lin, S.; et al. An Energy-Efficient Cardiac Arrhythmia Classification Processor using Heartbeat Difference based Classification and Event-Driven Neural Network Computation with Adaptive Wake-Up. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Custom Integrated Circuits Conference (CICC), Newport Beach, CA, USA, 24–27 April 2022; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, M.Y.; Zhong, T.S.; Hsieh, Y.T.; Lee, S.Y.; Chen, J.Y. A High Performance Accelerating CNN Inference on FPGA with Arrhythmia Classification. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 5th International Conference on Artificial Intelligence Circuits and Systems (AICAS), Hangzhou, China, 11–13 June 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J.; Liu, D.; Liu, Z.; Cheng, X.; Wei, L.; Zhang, C.; Zou, X.; Liu, B. Efficient Hardware Architecture of Convolutional Neural Network for ECG Classification in Wearable Healthcare Device. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I (TCASI) 2021, 68, 2976–2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Wang, Y.; Cai, Y.; Bi, B.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Y. A Low Power Spiking Neural Network Accelerator on FPGA for Real-Time Edge Computing. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Autonomous Systems (ISAS), Xi’an, China, 23–25 May 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Ahmadi, A.; MacEachern, L. Low-Cost Spiking Networks on FPGA for Event-Based Gesture Detection. In Proceedings of the 2025 International Symposium on Signals, Circuits and Systems (ISSCS), Iasi, Romania, 17–18 July 2025; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangaraj, S.; Oraon, P.; Ari, S.; Swain, A.K.; Mahapatra, K. FPGA Accelerated Convolutional Neural Network for Detection of Cardiac Arrhythmia. In Proceedings of the 4th IEEE International Conference on VLSI Systems, Architecture, Technology and Applications (VLSI SATA), Bengaluru, India, 17–18 May 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Rawal, V.; Prajapati, P.; Darji, A. Hardware implementation of 1D-CNN architecture for ECG arrhythmia classification. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2023, 85, 104865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameil, A.K.; Al-Raweshidy, H. Efficient CNN Architecture on FPGA Using High Level Module for Healthcare Devices. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 60486–60495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aamir, S.A.; Müller, P.; Kiene, G.; Kriener, L.; Stradmann, Y.; Grübl, A.; Schemmel, J.; Meier, K. A Mixed-Signal Structured AdEx Neuron for Accelerated Neuromorphic Cores. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2018, 12, 1027–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Wu, H.; Wei, J.; Wei, S.; Chen, H. An Asynchronous Reconfigurable SNN Accelerator With Event-Driven Time Step Update. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Asian Solid-State Circuits Conference (A-SSCC), Macao, China, 4–6 November 2019; pp. 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juarez-Lora, A.; Ponce-Ponce, V.H.; Sossa, H.; Rubio-Espino, E. R-STDP Spiking Neural Network Architecture for Motion Control on a Changing Friction Joint Robotic Arm. Front. Neurorobot. 2022, 16, 904017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xing, Y.; Zhang, L.; Hou, Z.; Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, F.; Liang, S.; Li, Z.; Yan, L. Accurate ECG Classification Based on Spiking Neural Network and Attentional Mechanism for Real-Time Implementation on Personal Portable Devices. Electronics 2022, 11, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Dong, L.; Zhang, B.; Xin, Y.; Geng, L. Real Time ECG Classification System Based on DWT and SVM. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Integrated Circuits, Technologies and Applications (ICTA), Nanjing, China, 23–25 November 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 155–156. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; He, W.; Shen, L.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, P.; Wu, M.; Zhang, H.; Zhou, P.; Liu, J.; et al. An 82 nW 0.53 pJ/SOP Clock-Free Spiking Neural Network with 40 µs Latency for AloT Wake-Up Functions Using Ultimate-Event-Driven Bionic Architecture and Computing-in-Memory Technique. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Solid-State Circuits Conference (ISSCC), San Francisco, CA, USA, 20–26 February 2022; Volume 65, pp. 372–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janveja, M.; Parmar, R.; Tantuway, M.; Trivedi, G. A DNN-Based Low Power ECG Co-Processor Architecture to Classify Cardiac Arrhythmia for Wearable Devices. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 2281–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.; Kim, K.K. Comparison of Artificial Neural Networks for Low-Power ECG-Classification System. Senseo Haghoeji 2020, 29, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Ling, X.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, N. FPGA-based 1D-CNN accelerator for real-time arrhythmia classification. J.-Real-Time Image Process. 2025, 22, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Single e-Prop Network | Two-Layer SNN Network | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Classification Time (ms) | 188,815 | 64,099 |

| Sample Size | 18,439 | 18,439 |

| Average Classification Time (ms) | 10.24 | 3.48 |

| Power (W) | 0.047 | 0.062 |

| Energy/Classification () | 481.28 | 215.53 |

| Accuracy (%) | 91.7 | 91.4 |

| [17] | [24] | [23] | [25] | |

| Device | ZCU 104 | XC7Z020 | Artix-7 | 180 nm ASIC |

| Methods | CNN | SVM | SNN | SNN |

| Dataset | MIT-BIH | MIT-BIH | MIT-BIH | MIT-BIH |

| Clock (MHz) | - | - | - | Asynchronous |

| Accuracy (%) | 98.64% | 98.7% | 92.07% | 90.5% |

| Classification Time (ms) | 219 | 0.28 | 1.32 | - |

| Power (W) | 4.177 | 2.059 | 0.246 | 0.35 |

| Energy/Classification () | 914,763 | 576.52 | 324.72 | - |

| On-chip Learning | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| [26] | [27] | [28] | This Work | |

| Device | 180 nm ASIC | XC7Z020 | Zynq-XC7Z020 | XC7Z045 |

| Methods | DNN | CNN | CNN | SNN |

| Dataset | MIT-BIH | MIT-BIH | MIT-BIH | MIT-BIH |

| Clock (Hz) | 12 K | - | 50 M | 25 M |

| Accuracy (%) | 91.6% | 95% | 96.55% | 98.6%/91.4% * |

| Classification Time (ms) | - | 791.6 | 63 | 3.48 |

| Power (W) | 8.75 | 2.266 | 1.78 | 0.062 |

| Energy/Classification () | 2.08 | 1,793,766 | 112,140 | 215.53 |

| On-chip Learning | NO | NO | NO | YES |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mao, J.; Hu, Y.; Song, F.; Li, Y.; Ma, D. A Low-Power SNN Processor Supporting On-Chip Learning for ECG Detection. Electronics 2025, 14, 4923. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244923

Mao J, Hu Y, Song F, Li Y, Ma D. A Low-Power SNN Processor Supporting On-Chip Learning for ECG Detection. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4923. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244923

Chicago/Turabian StyleMao, Jiada, Youneng Hu, Fan Song, Yitao Li, and De Ma. 2025. "A Low-Power SNN Processor Supporting On-Chip Learning for ECG Detection" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4923. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244923

APA StyleMao, J., Hu, Y., Song, F., Li, Y., & Ma, D. (2025). A Low-Power SNN Processor Supporting On-Chip Learning for ECG Detection. Electronics, 14(24), 4923. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244923