A Sequence Prediction Algorithm Integrating Knowledge Graph Embedding and Dynamic Evolution Process

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Sequence Prediction, Knowledge Graph Embedding, and Dynamic Evolution Process

2.1. Problem Definition of the Sequence Prediction Model

- (1)

- Sequence prediction based on classification: Common scenarios include the click-through rate (CTR) prediction task [15]. CTR is one of the important indicators for measuring the benefits of a product. In the sequence prediction task, has only two values: 0 and 1.0, respectively, representing that the user dislikes or likes the product.

- (2)

- Sequence prediction based on regression and multi-step time: Common regression scenarios include temperature, humidity, and other indicators. The values of these indicators exist within a certain range [16]. A typical multi-step application scenario of time-series prediction is weather forecasting. This scenario not only takes the next time prediction point as a parameter but also simultaneously inputs multiple future time prediction points into the model for prediction purposes. If the set parameters are as , then a single future point in time is denoted as . Here, T represents the length of the future time point. The expression of this type of sequence prediction model is as:

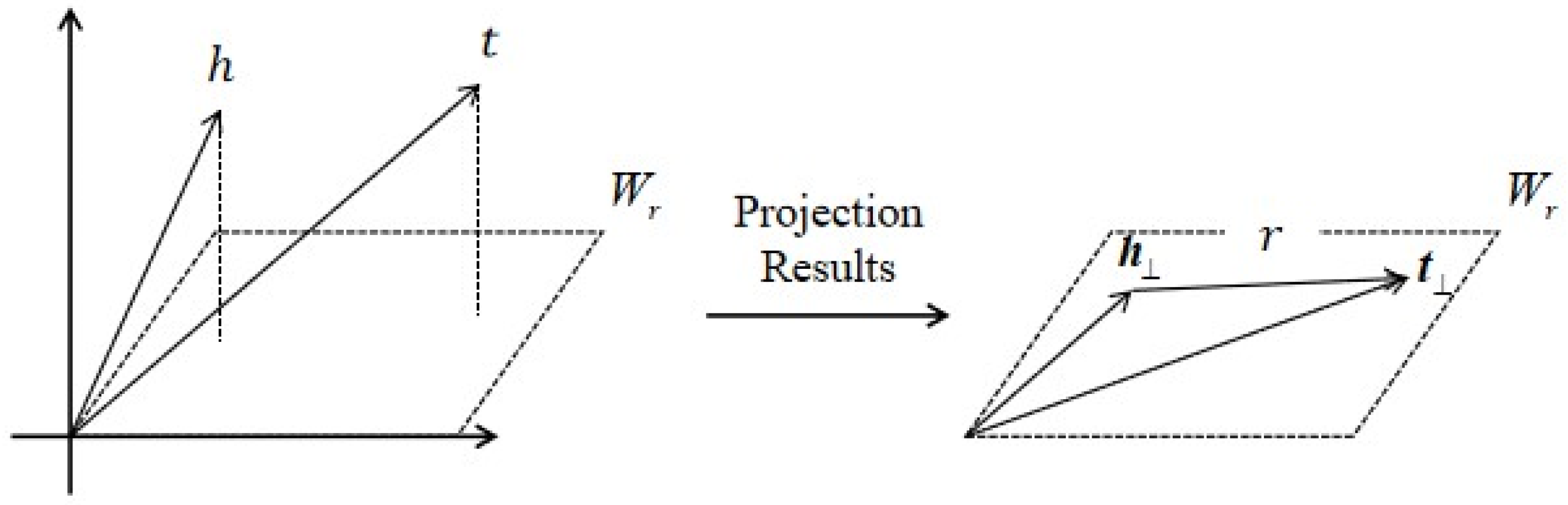

2.2. Embedding of Knowledge Graphs

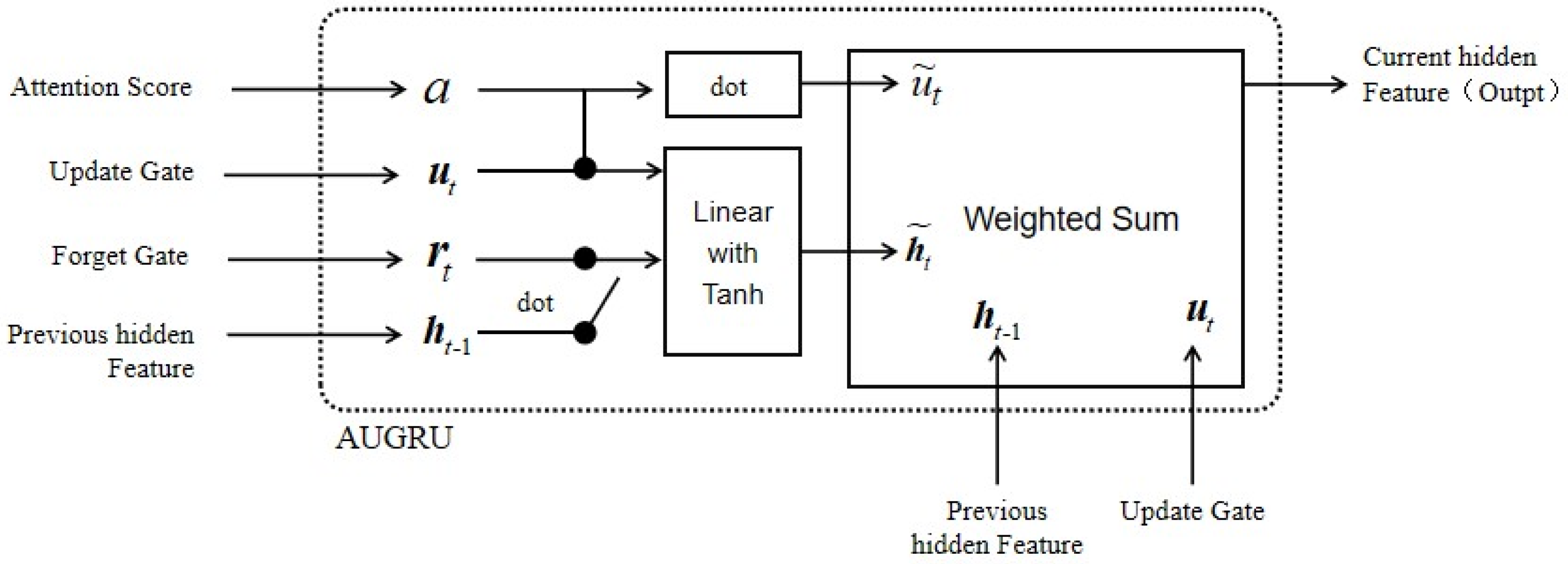

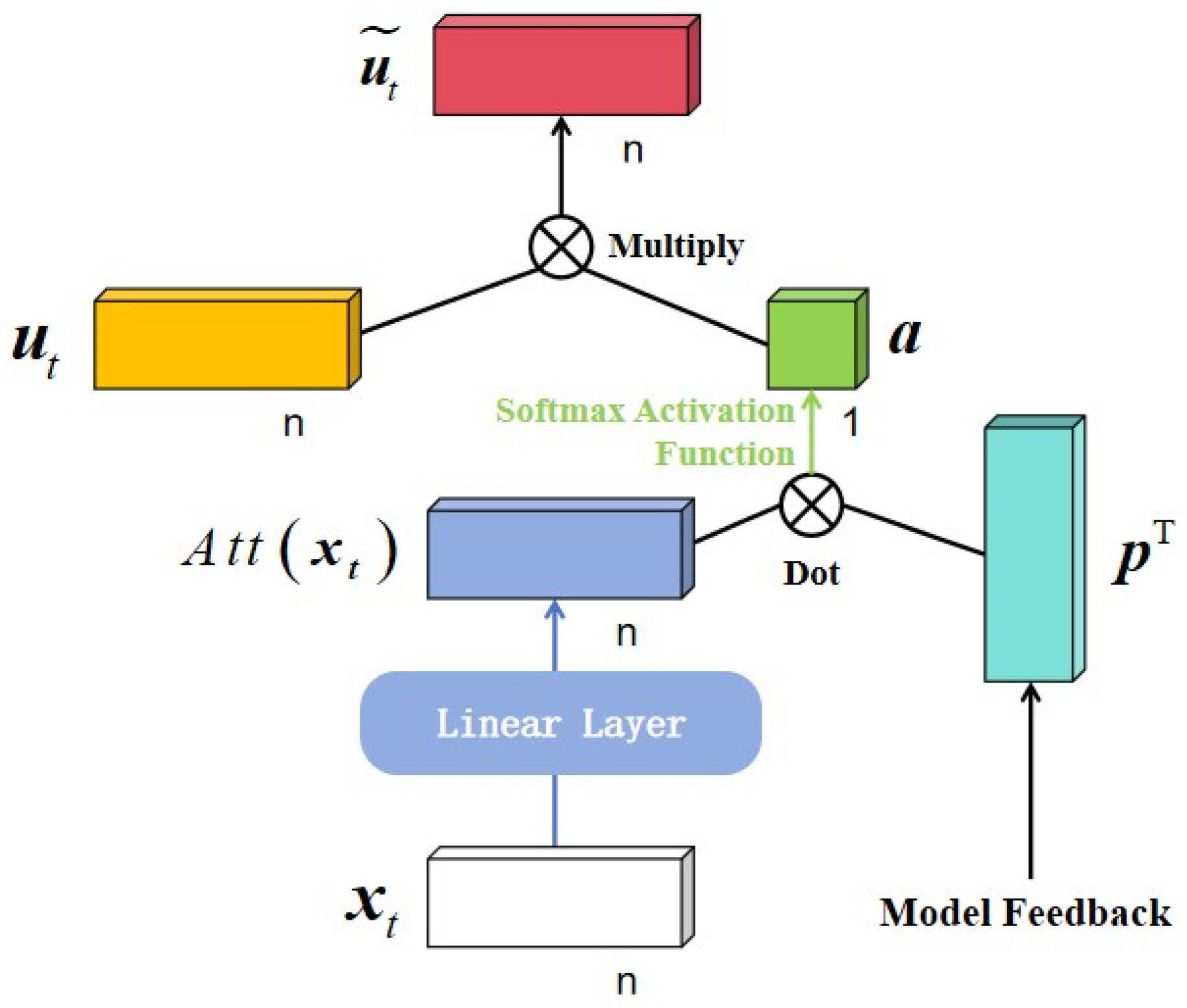

2.3. Dynamic Evolution Method

3. A Sequence Prediction Algorithm Integrating Knowledge Graph Embedding and Dynamic Evolution

3.1. Problem Definition of the KD4SP Algorithm

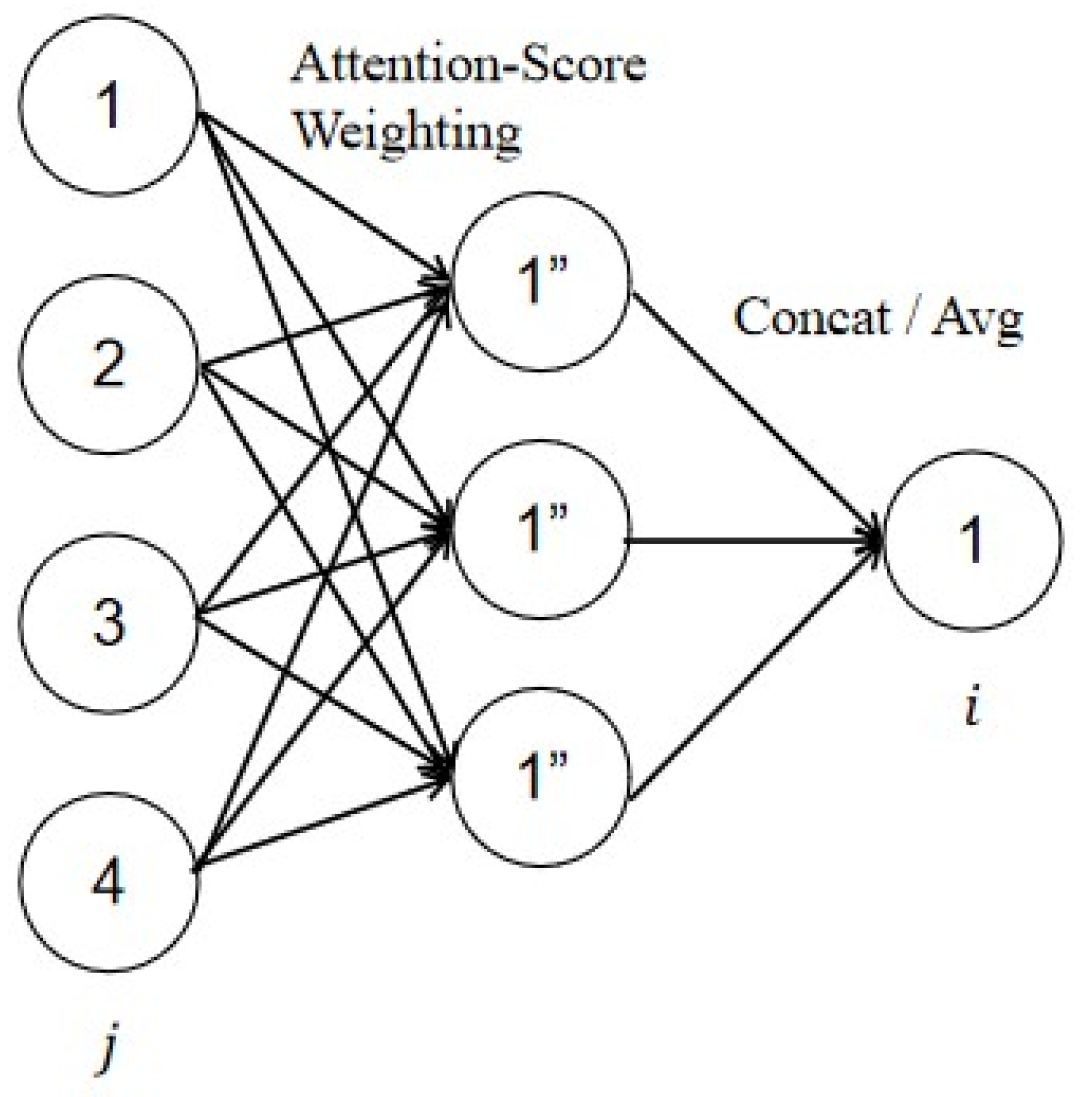

3.2. KD4SP Algorithm Model

3.3. Construction of Knowledge Graph

4. Experiments and Results

4.1. Experimental Dataset

4.2. Data Stationarity Test (ADF Test)

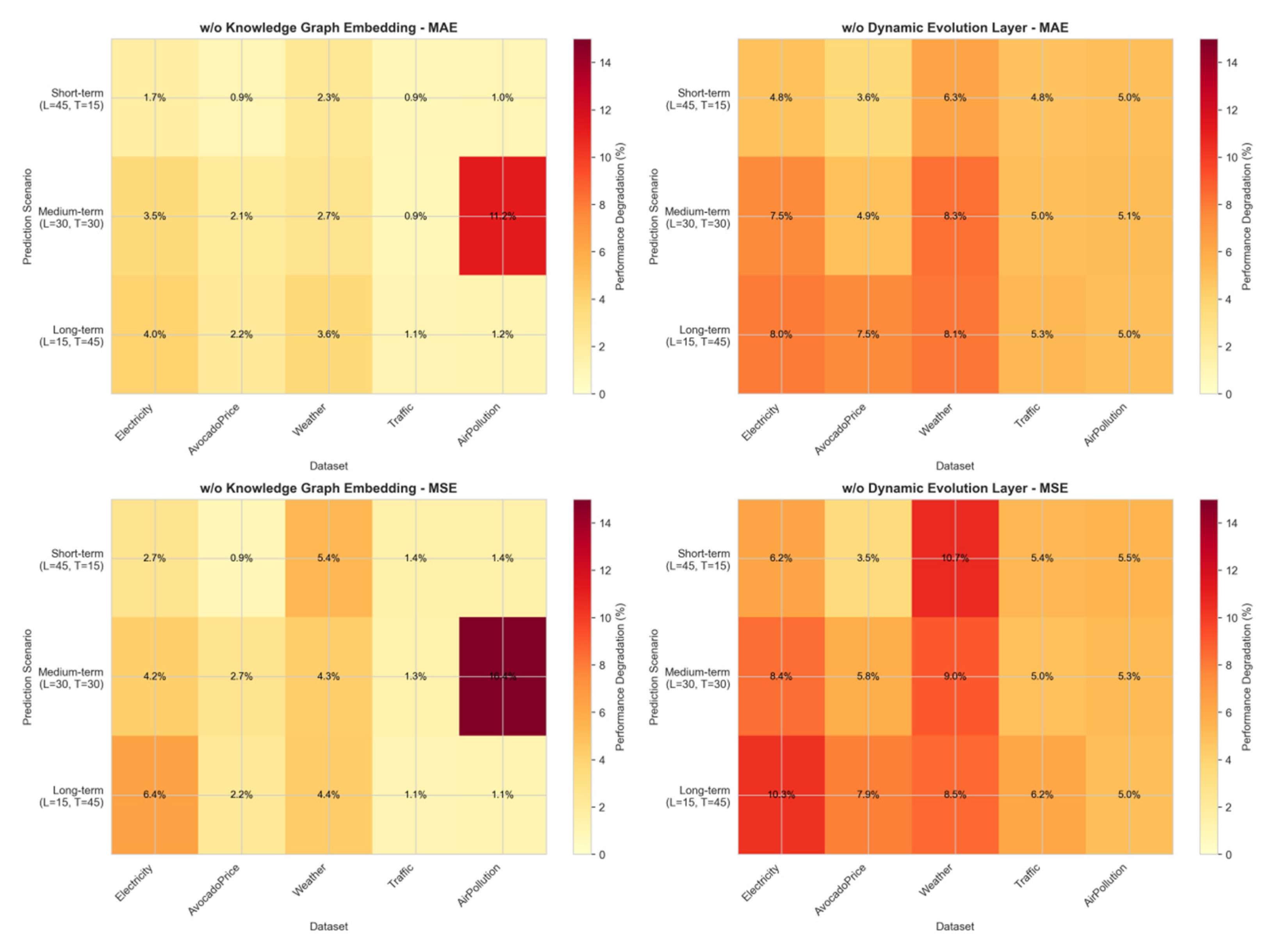

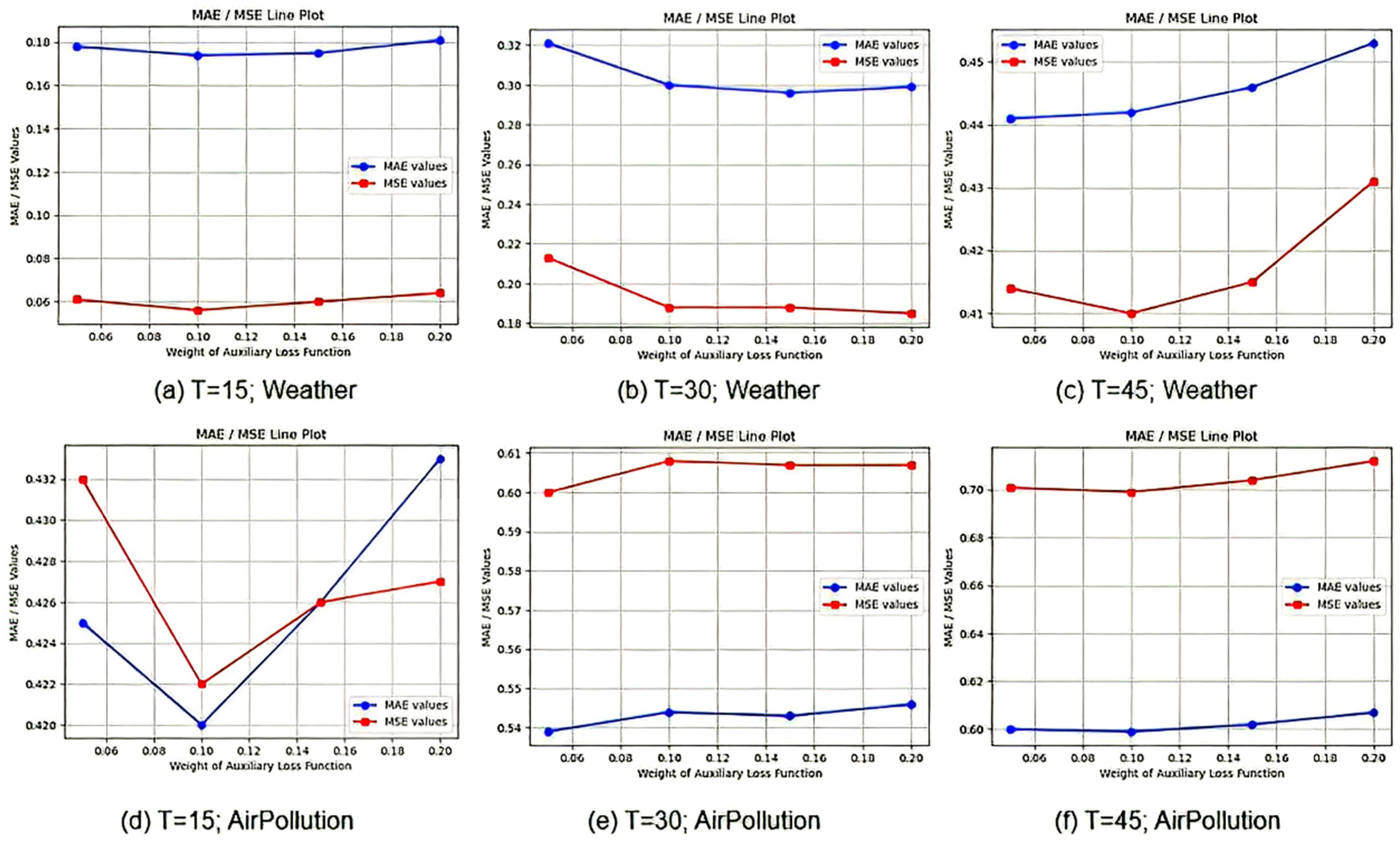

4.3. Ablation Analysis Experiment

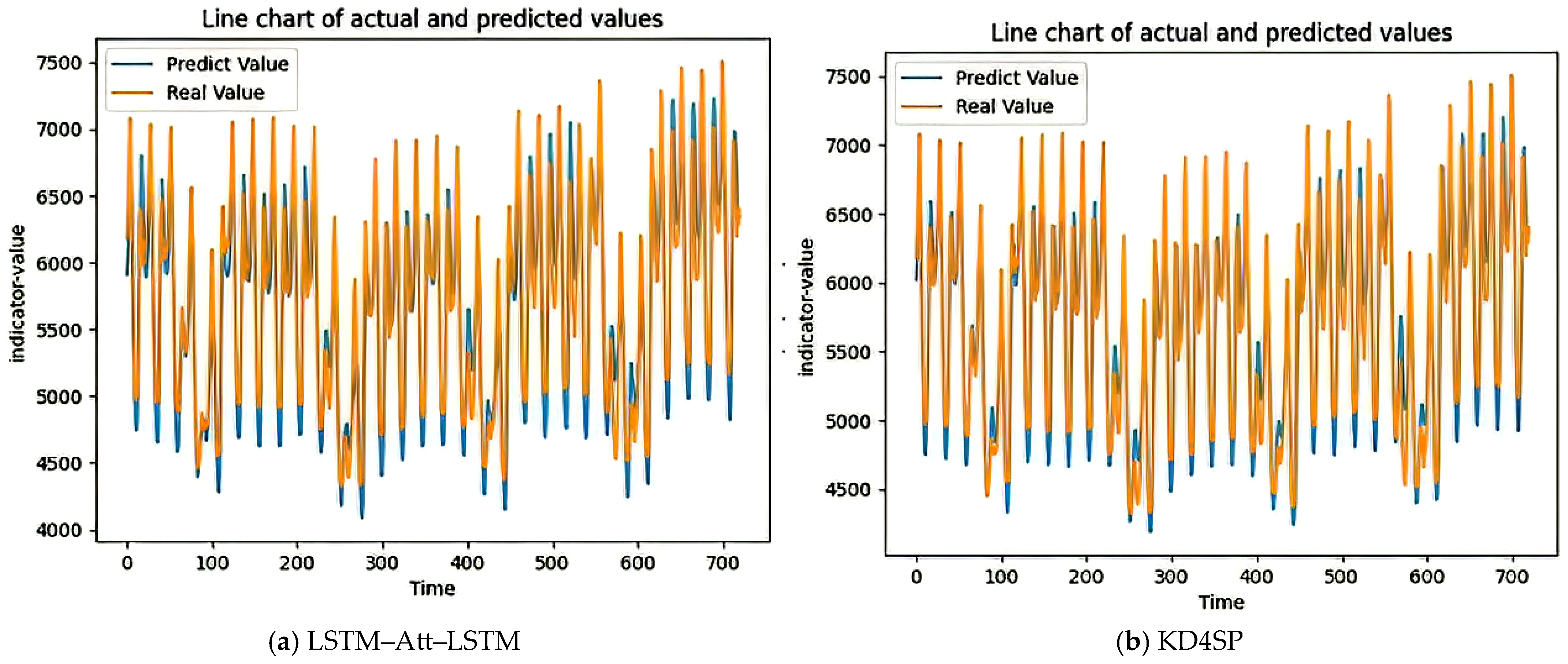

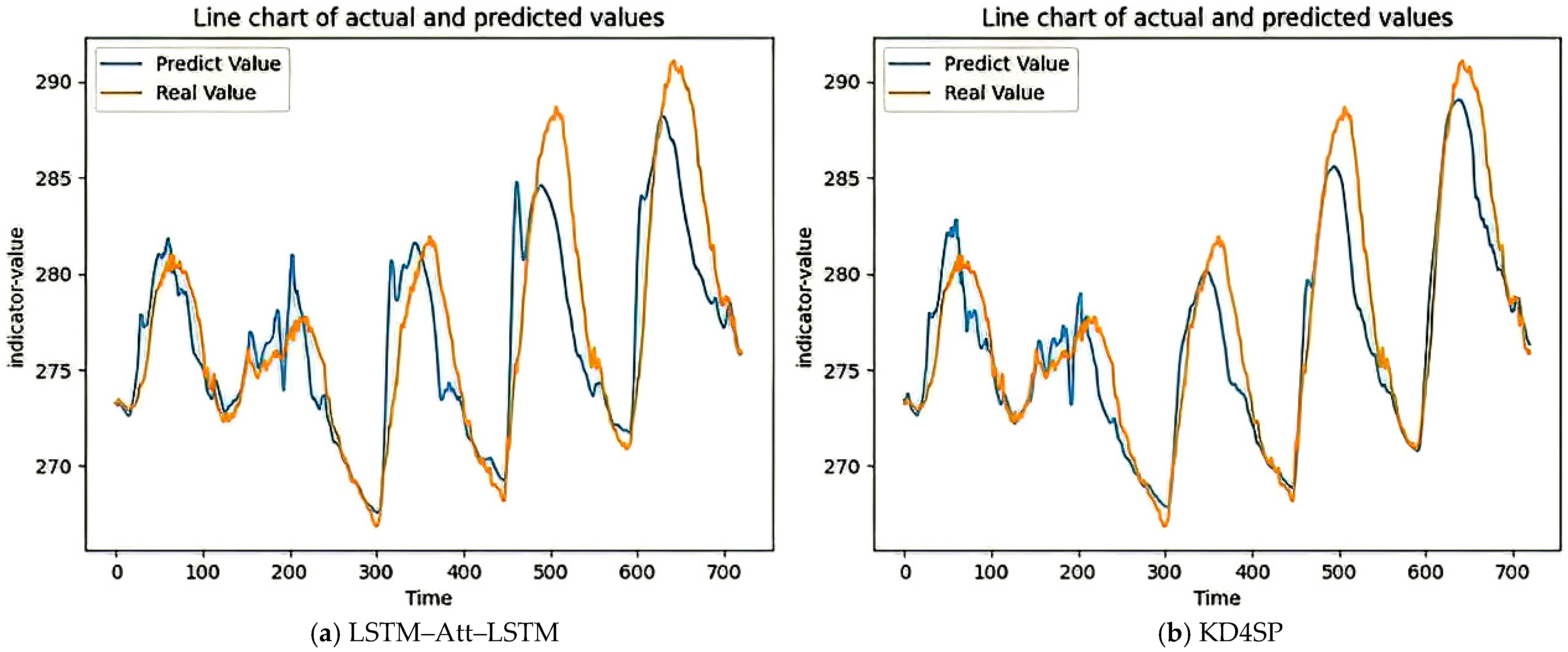

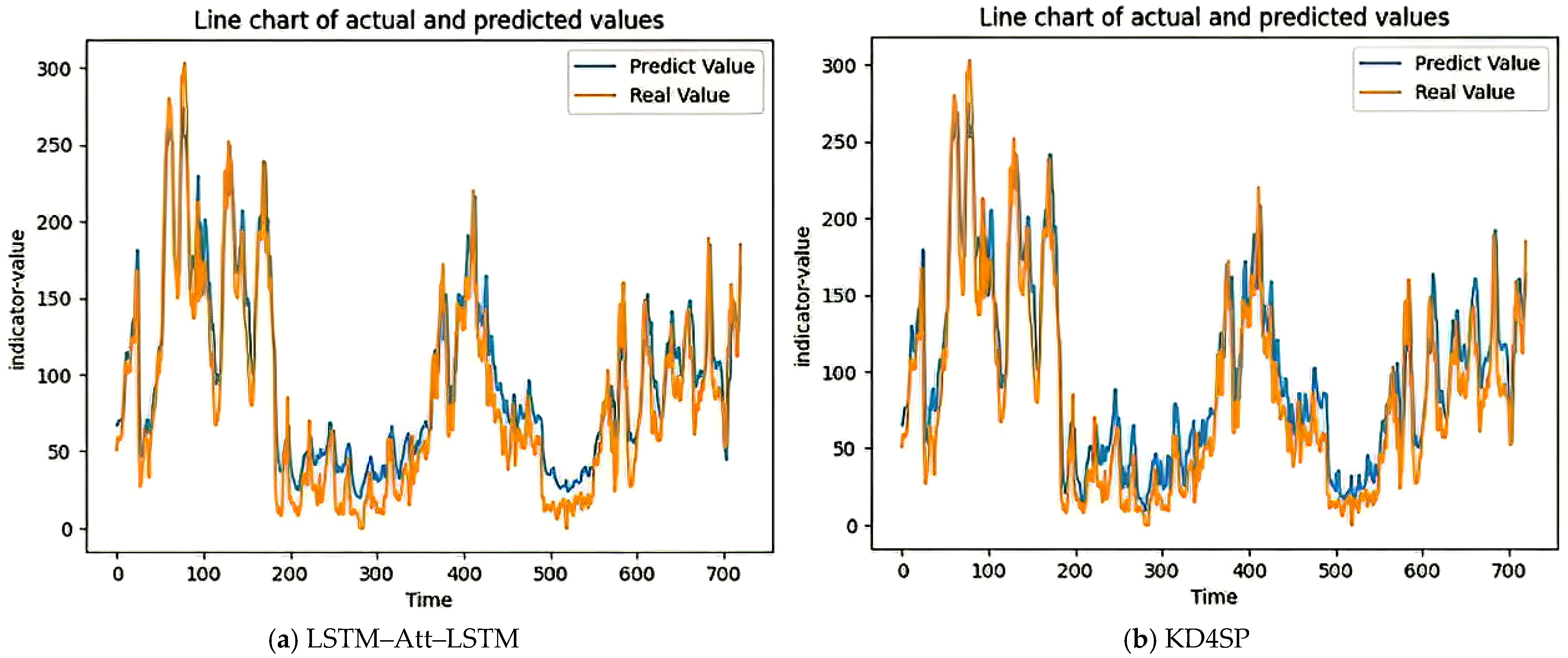

4.4. Experimental Results and Analysis

5. Conclusions and Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Algorithm A1. BuildTemporalFeatureGraph |

| Input:table: A data table containing ID and feature columns graph: Neo4j Graph Database connection Output: The temporal feature relationship graph constructed in Graph BEGIN // Initialize the feature node group of the previous time step last_feature_node_group ← empty list // Traverse each row in the data table (in chronological order) FOR EACH data IN table DO // Extract the current sample information sample_id ← data[“ID column “] feature_values_group ← data[“ Feature Column “] // Create the current sample node in the graph graph.create_node(sample_id, type=“sample”) If there are feature nodes from the previous time step, establish a temporal relationship IF last_feature_node_group ≠ empty THEN FOR EACH last_feature_node IN last_feature_node_group DO // Create the temporal relationship from the previous feature to the current sample graph.create_relationship(last_feature_node → sample_id, type=“TEMPORAL_FLOW”) END FOR // Clear the feature node group of the previous time step last_feature_node_group ← empty list END IF // Handle the feature relationship of the current sample FOR EACH feature_value IN feature_values_group DO // Create the relationship from samples to features graph.create_relationship(sample_id → feature_value, type=“HAS_FEATURE”) // Add the current feature node to the cache for use in the next step last_feature_node_group.append(feature_value) END FOR END FOR END |

References

- Bie, Y. Research on Space-Time Feature Learning Method for Short-Term and Near-Term Precipitation Radar Echo Sequence Prediction. Master’s Thesis, Xi’an University of Technology (China), Xi’an, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Z.; Tang, C. Multi-site PM2.5 mass concentration prediction method based on GCN-GRU-Attention. J. Hubei Minzu Univ. 2025, 43, 67–72+85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Wang, T.; Zhang, Y. Consider the multi-feature expressway traffic flow prediction model. Transp. Syst. Eng. Inf. 2021, 21, 101–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiliotis, E. Decision trees for time-series forecasting. Foresight 2022, 1, 30–44. [Google Scholar]

- Pattanayak, R.M.; Panigrahi, S.; Behera, H.S. High-order fuzzy time series forecasting by using membership values along with data and support vector machine. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 10311–10325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.; Li, W. Time Series Prediction Based on LSTM-Attention-LSTM Model. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 48322–48331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Tian, H.; Xiao, T.; Xu, T.; Lei, H. Time series forecasting of oil production in Enhanced Oil Recovery system based on a novel CNN-GRU neural network. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 233, 212528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rostamian, A.; O’hara, J.G. Event prediction within directional change framework using a CNN-LSTM model. Neural Comput. Appl. 2022, 34, 17193–17205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, S.; Wang, B.O.J. Deep transition network with gating mechanism for multivariate time series forecasting. Appl. Intell. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Neural Netw. Complex Probl.-Solving Technol. 2023, 53, 24346–24359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Ding, F.; Zhai, L. Multi-scale temporal features extraction based graph convolutional network with attention for multivariate time series prediction. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 200, 117011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Shi, S.; Xu, L. A spatial—Temporal graph attention network approach for air temperature forecasting. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 113, 107888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, C. Deep User Interest Evolution Model Based on Graph Data Enhancement. Master’s Thesis, Shanxi University, Taiyuan, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena, A.; Kochsiek, A.; Gemulla, R. Sequence-to-Sequence Knowledge Graph Completion and Question Answering. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Z. Behavior Prediction and Sequence Recommendation Based on User Interaction Intentions. Master’s Thesis, Qinghai Normal University, Xining, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Wang, Y.C.; Wang, B.; Kuo, C.C.J. Knowledge Graph Embedding: An Overview. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2309.12501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Ma, T.; Su, Y. Polynomial projection and information exchange architecture for long-term Time series prediction. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2025, 61, 120. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.2127.tp.20240621.0915.002.html (accessed on 12 May 2025).

- Wang, X.; Liu, H.; Yang, Z.; Du, J.; Dong, X. CNformer: A convolutional Transformer with decomposition for long-term multivariate time series forecasting. Appl. Intell. 2023, 53, 20191–20205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q. Multivariate time series prediction based on deep learning. J. Nanjing Univ. Financ. Econ. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Shangguan, A.; Fei, R.; Ji, W.; Ma, W.; Hei, X. Motion trajectory prediction based on a CNN-LSTM sequential model. Sci. China Inf. Sci. 2020, 63, 212207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, R.; Mei, S.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Yang, F. Multivariate temporal convolutional network: A deep neural networks approach for multivariate time series forecasting. Electronics 2019, 8, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, J. Research on Time Series Prediction Algorithm Based on Deep Learning. Master’s Thesis, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, China, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2020, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.; Luo, J.; He, M.; Gu, W. Graph neural network for traffic forecasting: The research progress. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Huang, B.; Wang, C. Meta-path recommendation algorithm for knowledge graph embedding based on heterogeneous attention networks. J. Univ. Electron. Sci. Technol. China 2025, 54, 776–788. Available online: http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/51.1207.TN.20241225.2003.004.html (accessed on 25 March 2025).

- Electricity. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/individual+household+electric+power+consumption (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Cheng, S. Research and Implementation of Movie Recommendation System Based on Deep Learning and Behavior Sequence. Master’s Thesis, Southwest Jiaotong University, Chengdu, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Avocado Price. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/neuromusic/avocado-prices (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Zhou, G.; Zhu, X.; Song, C.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, H.; Ma, X.; Yan, Y.; Jin, J.; Li, H.; Gai, K. Deep Interest Network for Click-Through Rate Prediction. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 1059–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traffic. Collected, organized and released by an authoritative data storage platform named “UCI Machine Learning Repository” (University of California, Irvine Machine Learning Repository). Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/PEMS-SF (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- Bai, S.; Kolter, J.Z.; Koltun, V. An empirical evaluation of generic convolutional and recurrent networks for sequence modeling. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Weather. Weather.js is designed as a comprehensive JavaScript Weather library built around the OpenWeatherMap API (non-affiliate relationship), originally created by Noah Smith and currently maintained by PallasStreams. Available online: https://github.com/noazark/weather (accessed on 7 December 2025).

- AirPollution. A Well-Known Multivariate Time Series Benchmark Dataset Collated and Published by the UCI Machine Learning Repository. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Air+Quality (accessed on 7 December 2025).

| Dataset | Predictive Indicator | Standard Deviation | Mean Value | Feature Count |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | Consumption volume | 1043.6435 | 6587.6164 | 9 |

| AvocadoPrice | Average price | 0.4026 | 1.4059 | 12 |

| Traffic | Traffic volume | 1986.8400 | 3259.8183 | 7 |

| Weather | Temperature | 5.6636 | 276.8251 | 21 |

| AirPollution | Pollution index | 92.2512 | 94.0135 | 8 |

| Dataset | ADF Statistics | p Value | Conclusion (α = 0.05) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity | −4.823 | 0.0001 | Stable |

| AvocadoPrice | −3.156 | 0.023 | Stable |

| Traffic | −1.847 | 0.358 | Non-stationary |

| Weather | −5.234 | ≈0.00002 | Stable |

| AirPollution | −1.234 | 0.658 | Non-stationary |

| Dataset | MAE | MSE |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 0.357 | 0.230 |

| AvocadoPrice | 0.638 | 0.756 |

| Traffic | 0.443 | 0.358 |

| Weather | 0.178 | 0.059 |

| AirPollution | 0.424 | 0.428 |

| Dataset | MAE | MSE |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 0.412 | 0.298 |

| AvocadoPrice | 0.728 | 0.968 |

| Traffic | 0.581 | 0.550 |

| Weather | 0.308 | 0.196 |

| AirPollution | 0.605 | 0.708 |

| Dataset | MAE | MSE |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 0.467 | 0.381 |

| AvocadoPrice | 0.758 | 1.028 |

| Traffic | 0.651 | 0.655 |

| Weather | 0.458 | 0.428 |

| AirPollution | 0.605 | 0.708 |

| Dataset | MAE | MSE |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 0.368 | 0.238 |

| AvocadoPrice | 0.655 | 0.775 |

| Traffic | 0.460 | 0.372 |

| Weather | 0.185 | 0.062 |

| AirPollution | 0.441 | 0.445 |

| Dataset | MAE | MSE |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 0.428 | 0.310 |

| AvocadoPrice | 0.748 | 0.998 |

| Traffic | 0.605 | 0.570 |

| Weather | 0.325 | 0.205 |

| AirPollution | 0.572 | 0.640 |

| Dataset | MAE | MSE |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity | 0.485 | 0.395 |

| AvocadoPrice | 0.798 | 1.085 |

| Traffic | 0.678 | 0.688 |

| Weather | 0.478 | 0.445 |

| AirPollution | 0.628 | 0.735 |

| Parameter Interpretation | Parameter Value |

|---|---|

| Embedding dimension | 64 |

| Feature extraction layer and hidden layer | 64 |

| Dynamic evolution layer and hidden layer | 64 |

| Regularization coefficient of auxiliary loss function | 1 |

| Auxiliary loss function weights | 0.1 |

| Electricity | Avocado Price | Traffic | Weather | Air Pollution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | |

| LSTM–Att–LSTM | 0.366 | 0.231 | 0.640 | 0.754 | 0.422 | 0.334 | 0.204 | 0.102 | 0.398 | 0.395 |

| AI-DTN | 0.411 | 0.327 | 0.688 | 0.789 | 0.451 | 0.368 | 0.203 | 0.924 | 0.430 | 0.425 |

| TCN | 0.480 | 0.417 | 0.773 | 0.891 | 0.566 | 0.534 | 0.251 | 0.157 | 0.485 | 0.497 |

| CNformer | 0.435 | 0.308 | 0.695 | 0.804 | 0.462 | 0.377 | 0.189 | 0.062 | 0.426 | 0.430 |

| GEIFA | 0.454 | 0.338 | 0.670 | 0.814 | 0.521 | 0.471 | 0.237 | 0.101 | 0.439 | 0.438 |

| KD4SP | 0.351 | 0.224 | 0.632 | 0.749 | 0.439 | 0.353 | 0.174 | 0.056 | 0.420 | 0.422 |

| Electricity | Avocado Price | Traffic | Weather | Air Pollution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | |

| LSTM–Att–LSTM | 0.405 | 0.288 | 0.748 | 1.038 | 0.568 | 0.531 | 0.315 | 0.198 | 0.534 | 0.588 |

| AI-DTN | 0.481 | 0.372 | 0.762 | 1.032 | 0.592 | 0.562 | 0.351 | 0.262 | 0.573 | 0.620 |

| TCN | 0.493 | 0.407 | 0.810 | 1.100 | 0.682 | 0.650 | 0.413 | 0.303 | 0.586 | 0.639 |

| CNformer | 0.466 | 0.361 | 0.758 | 0.982 | 0.588 | 0.563 | 0.296 | 0.194 | 0.539 | 0.601 |

| GEIFA | 0.469 | 0.366 | 0.744 | 0.951 | 0.640 | 0.643 | 0.386 | 0.285 | 0.548 | 0.615 |

| KD4SP | 0.398 | 0.286 | 0.713 | 0.943 | 0.576 | 0.543 | 0.300 | 0.188 | 0.544 | 0.608 |

| Electricity | Avocado Price | Traffic | Weather | Air Pollution | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | MAE | MSE | |

| LSTM–Att–LSTM | 0.455 | 0.371 | 0.772 | 1.103 | 0.647 | 0.642 | 0.457 | 0.432 | 0.593 | 0.696 |

| AI-DTN | 0.524 | 0.434 | 0.804 | 1.102 | 0.690 | 0.714 | 0.486 | 0.514 | 0.630 | 0.743 |

| TCN | 0.569 | 0.487 | 0.862 | 1.221 | 0.761 | 0.814 | 0.527 | 0.533 | 0.625 | 0.735 |

| CNformer | 0.510 | 0.421 | 0.768 | 1.081 | 0.658 | 0.671 | 0.443 | 0.422 | 0.605 | 0.703 |

| GEIFA | 0.495 | 0.410 | 0.795 | 1.150 | 0.685 | 0.713 | 0.514 | 0.536 | 0.613 | 0.733 |

| KD4SP | 0.449 | 0.358 | 0.742 | 1.006 | 0.647 | 0.648 | 0.442 | 0.410 | 0.598 | 0.700 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qiu, J.; Cui, D.; Peng, Z.; Li, Q.; He, J. A Sequence Prediction Algorithm Integrating Knowledge Graph Embedding and Dynamic Evolution Process. Electronics 2025, 14, 4922. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244922

Qiu J, Cui D, Peng Z, Li Q, He J. A Sequence Prediction Algorithm Integrating Knowledge Graph Embedding and Dynamic Evolution Process. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4922. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244922

Chicago/Turabian StyleQiu, Jinbo, Delong Cui, Zhiping Peng, Qirui Li, and Jieguang He. 2025. "A Sequence Prediction Algorithm Integrating Knowledge Graph Embedding and Dynamic Evolution Process" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4922. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244922

APA StyleQiu, J., Cui, D., Peng, Z., Li, Q., & He, J. (2025). A Sequence Prediction Algorithm Integrating Knowledge Graph Embedding and Dynamic Evolution Process. Electronics, 14(24), 4922. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244922