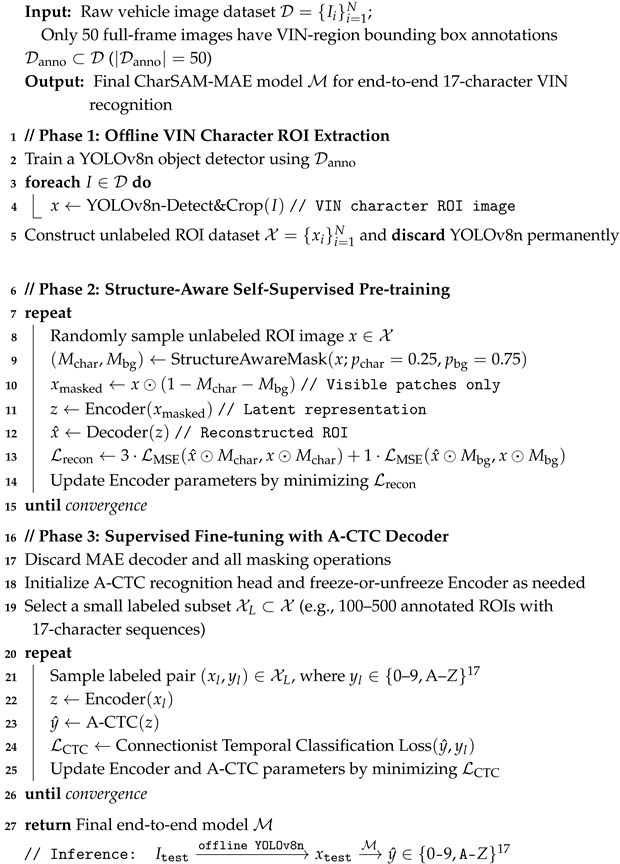

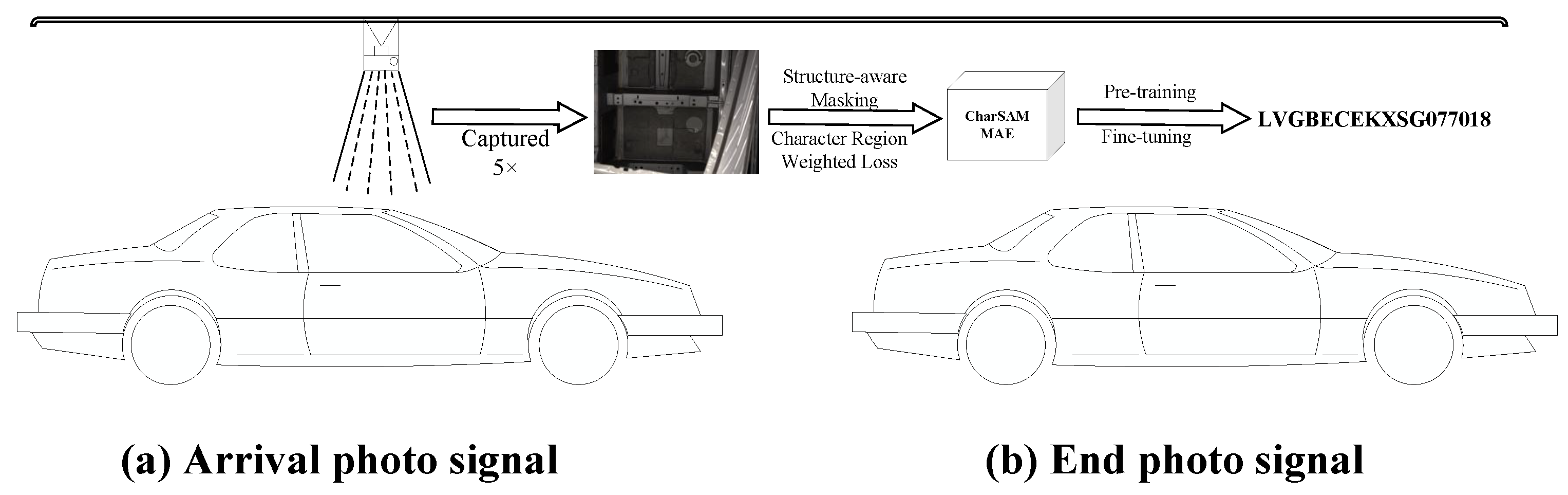

4.1. Data Preprocessing

The original vehicle character dataset contained 7967 images. To enhance model robustness and increase training diversity, data augmentation was performed by randomly selecting 30% of the images for % linear brightness adjustment and 10% for mild Gaussian blur, simulating illumination variation and defocus effects. After augmentation, the dataset was expanded to 13,544 images.

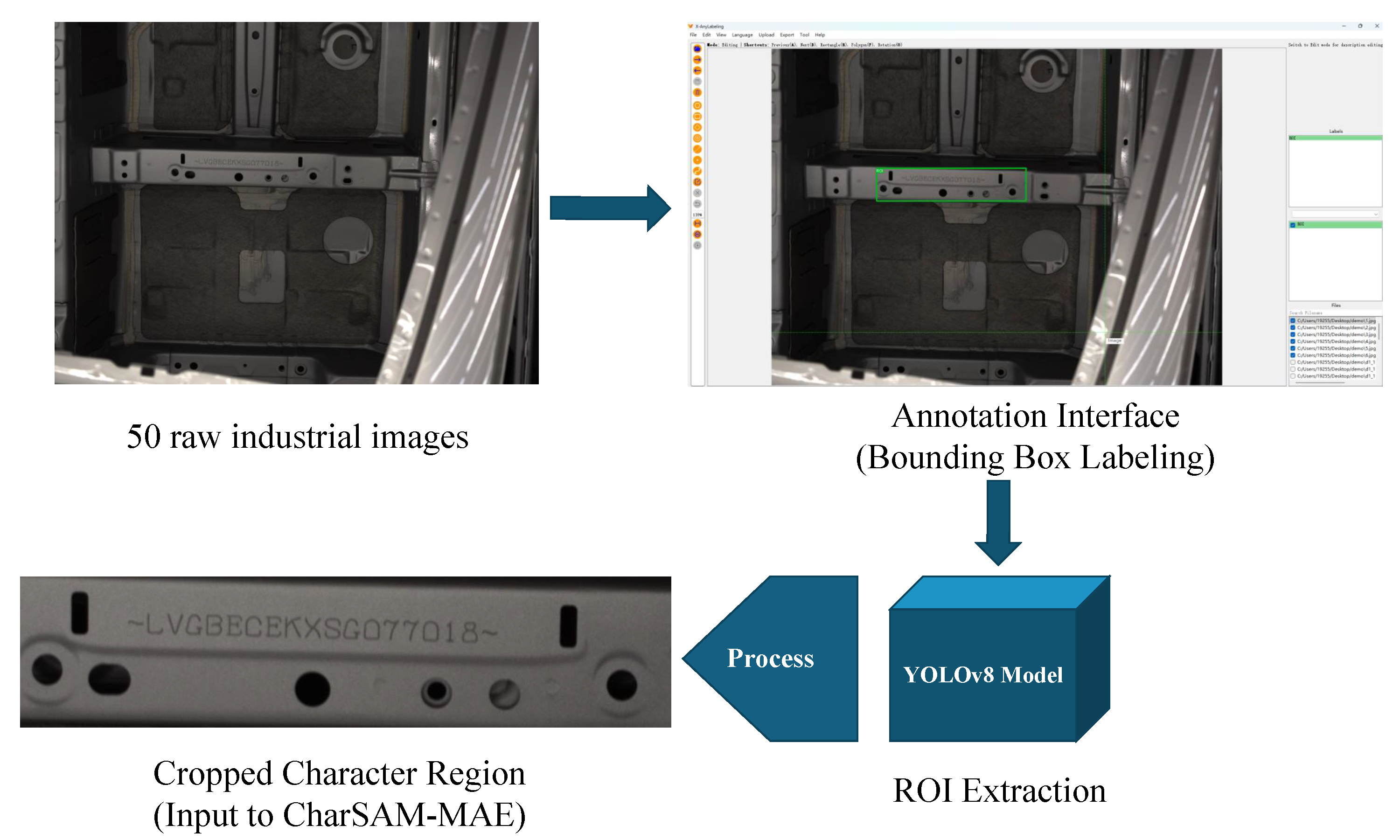

Before augmentation, all images were preprocessed using a YOLOv8n cropping stage to remove irrelevant background and retain only the VIN character region. Only these cropped ROI images were used for both pre-training and fine-tuning of the CharSAM-MAE model. It should be emphasized that the 50 raw annotated images used to train YOLOv8n were not included in this dataset and were discarded immediately after training the detector, ensuring no interaction between YOLO-based preprocessing and the subsequent self-supervised learning process.

Two distinct data partitions were used during model training. In the self-supervised pre-training stage, all 13,544 unlabeled ROI images were utilized to train the structure-aware MAE for generalizable representation learning. During the fine-tuning stage, only 5% of the original labeled data (approximately 400 images) were employed for supervised adaptation [

30], further divided into training (70%), validation (20%), and test (10%) subsets.This strategy significantly reduces dependence on labeled data while maintaining strong generalization capability, as summarized in

Table 1.

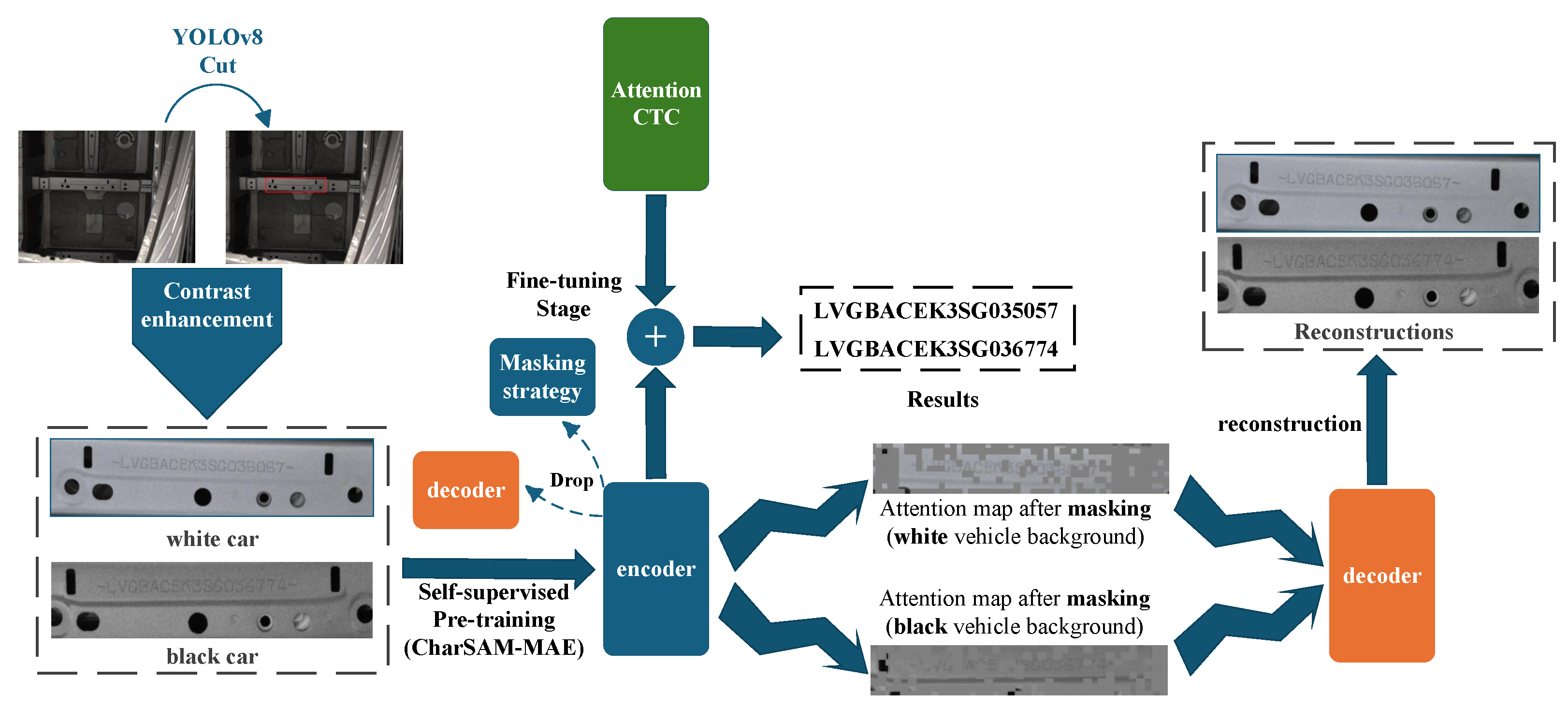

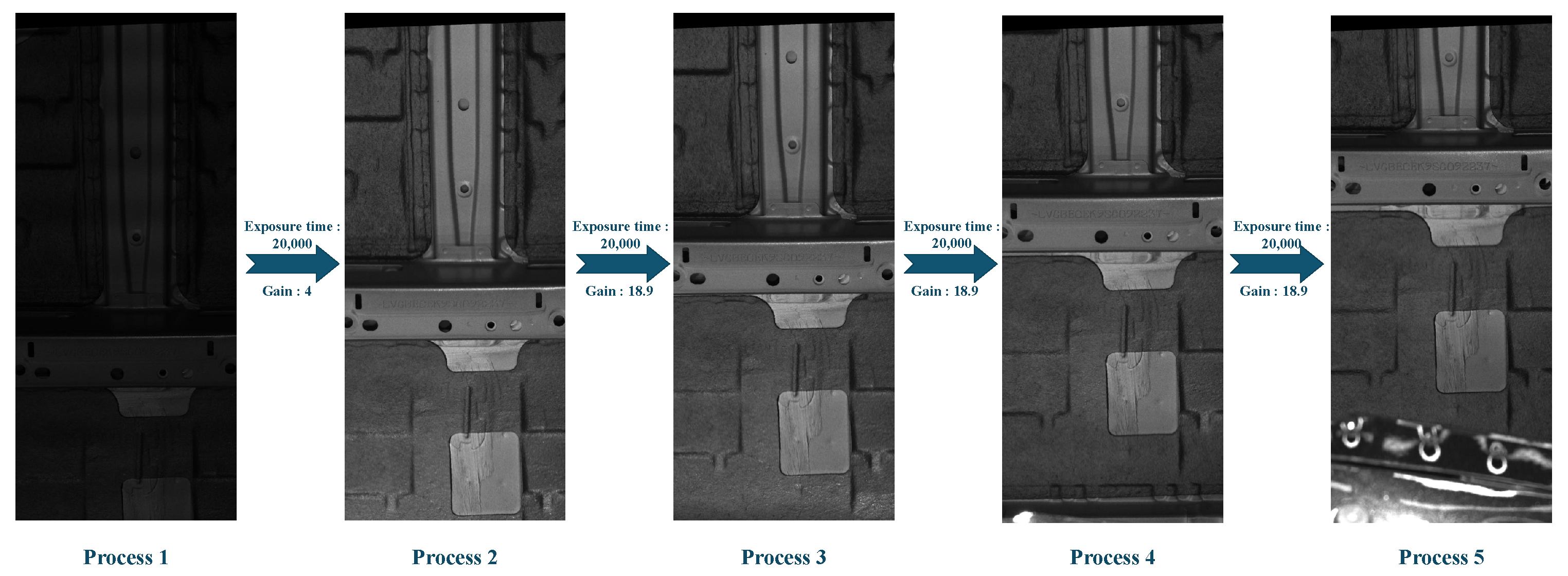

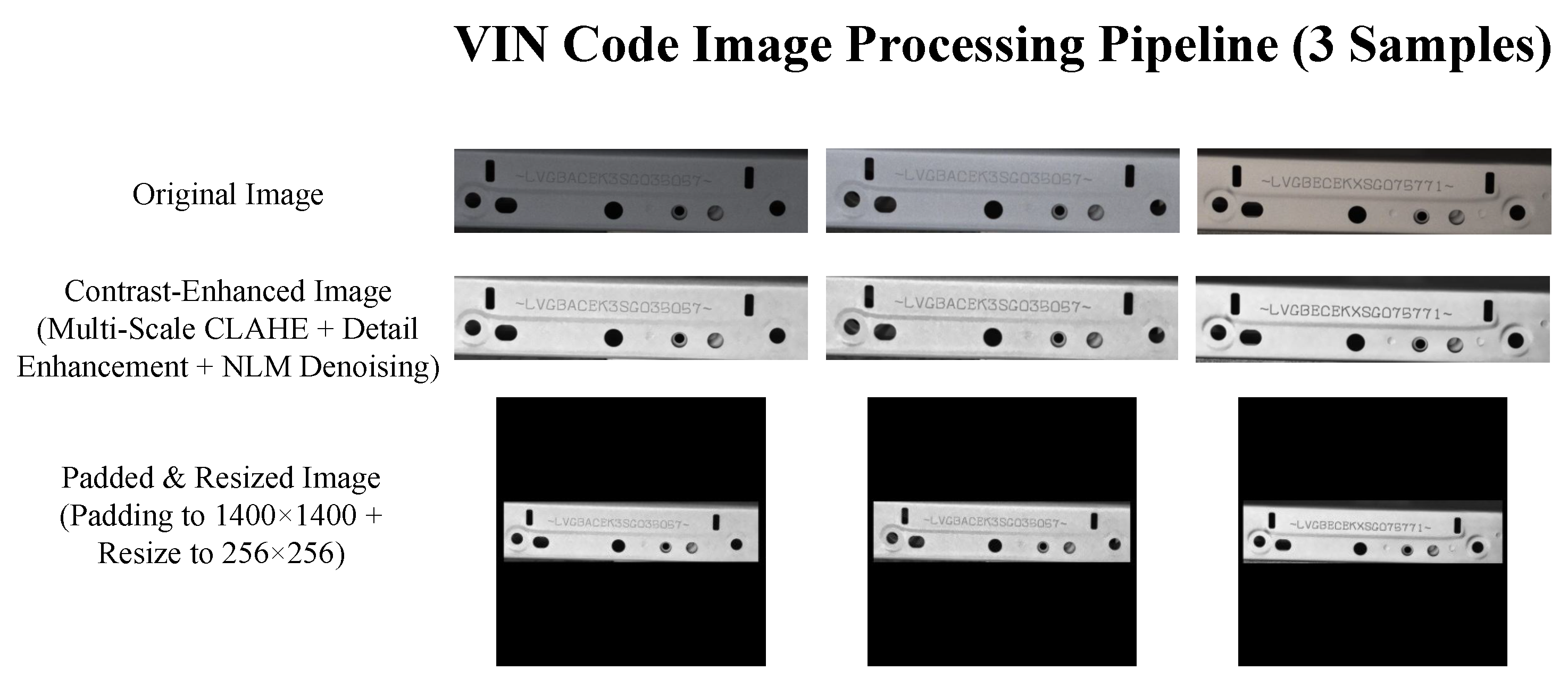

To enhance the quality of vehicle character images and improve recognition performance, a multi-stage image preprocessing pipeline was designed. First, the original RGB images were converted to grayscale and normalized to ensure uniform pixel distribution. Then, contrast-limited adaptive histogram equalization (CLAHE) was applied at multiple scales (8 × 8, 16 × 16, and 32 × 32 grid sizes) to simultaneously enhance local character details and global contrast. The enhanced results from different scales were fused with weighted averaging, followed by bilateral filtering to preserve edges while smoothing. In addition, a combination of detail enhancement and non-local means denoising was employed to suppress noise and highlight character contours and textures. This preprocessing significantly improved the clarity and signal-to-noise ratio of character regions, providing a solid foundation for downstream deep feature extraction, The full preprocessing pipeline is illustrated in

Figure 10.

Given that most raw images had a resolution of 1300 × 300, black padding was applied to maintain the original structure while resizing them to a square format. All images were finally rescaled to 256 × 256 pixels to standardize input dimensions, ensuring centered character regions without distortion and improving training efficiency.

4.2. Experimental Setup

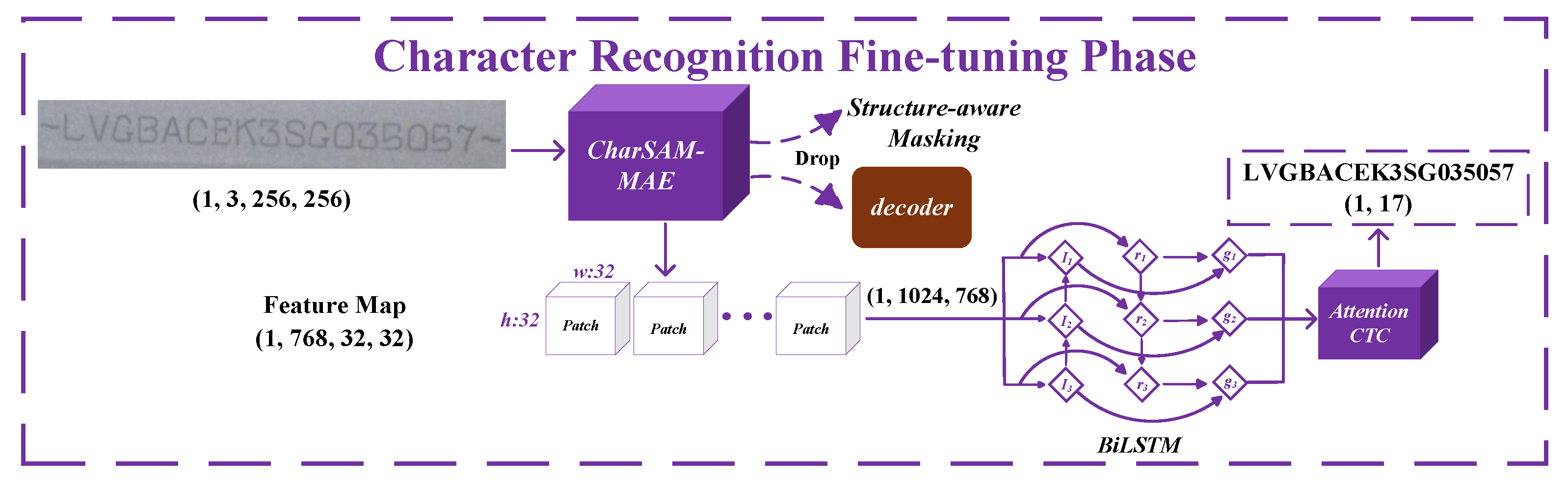

The proposed method first performs self-supervised pretraining on the full unlabeled dataset using the structure-aware MAE to learn key structural features of vehicle characters. Then, 15% of the labeled samples are used for supervised fine-tuning, with a 70%-20%-10% split for training, validation, and testing, respectively. During fine-tuning, high-level features are extracted via the pretrained MAE encoder, further enhanced by a multi-head self-attention module, and decoded by an attention-integrated CTC decoder for character sequence prediction. The model is optimized using the AdamW optimizer, with class weights incorporated into the loss function to address class imbalance.

Model performance is evaluated using multiple metrics: character-level accuracy (CharAcc), character error rate (CER), and sequence-level accuracy (SeqAcc), providing a comprehensive assessment of recognition quality. The corresponding metric formulas are defined as follows:

where

denotes the number of correctly predicted characters,

represents the total number of characters,

,

, and

indicate the number of character substitutions, insertions, and deletions, respectively, and

L denotes the length of the character sequence.

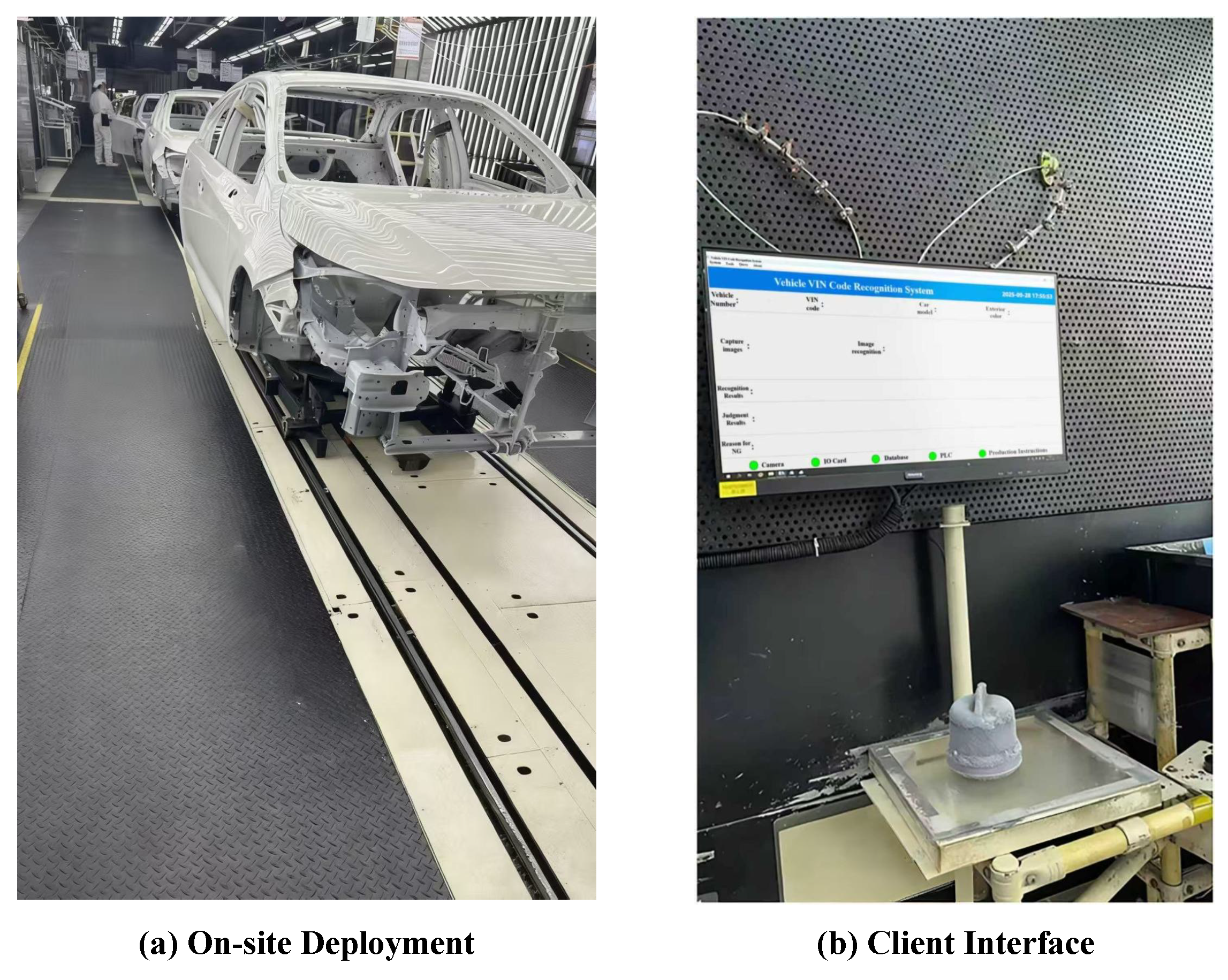

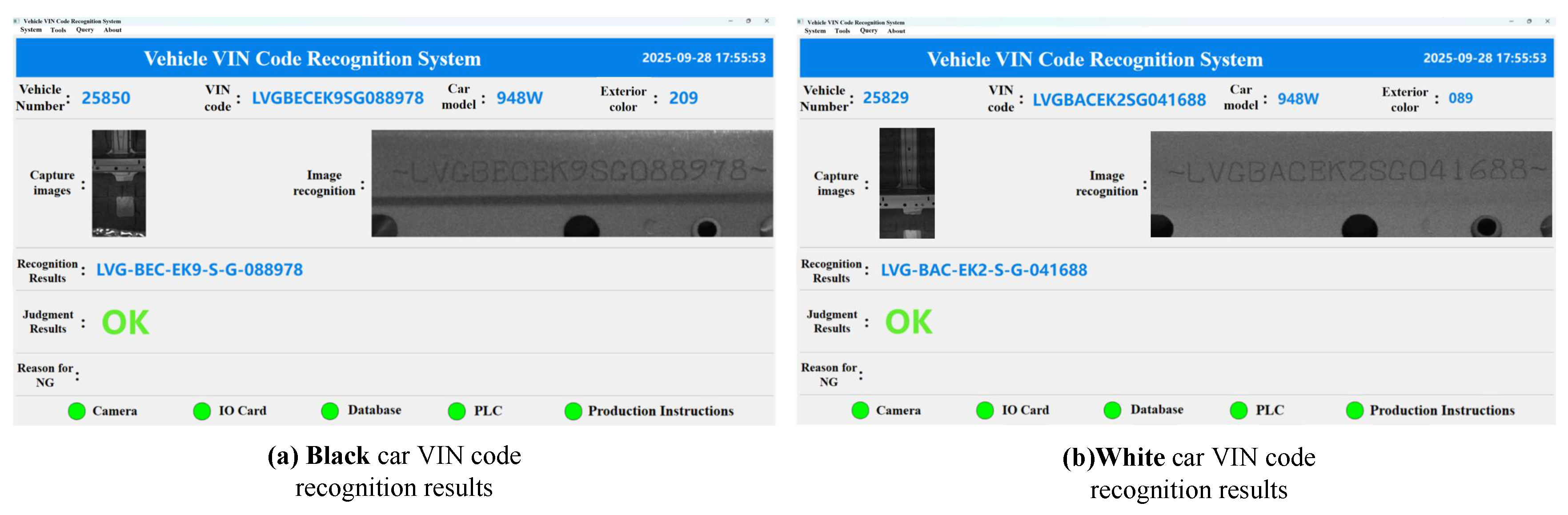

Considering the practical industrial production workflow, the VIN acquisition cycle is approximately 60 s per vehicle, during which image capturing and manufacturing data synchronization dominate total processing time. In contrast, the inference stage of the proposed method accounts for only a negligible fraction of this period and does not impose any delay on the overall pipeline. Therefore, model efficiency is not a limiting factor for deployment, and the recognition module fully meets real-time operational requirements under factory conditions.

4.3. Comparison with Baselines

To validate the effectiveness of CharSAM-MAE in the VIN code recognition task, we conducted two groups of comparative experiments: one comparing the performance of different models on VIN recognition, and another evaluating the impact of data augmentation on model performance.

As shown in the experimental results, CharSAM-MAE clearly outperforms both CRNN and PaddleOCR v5 in terms of CharAcc and SeqAcc.Specifically, CharSAM-MAE achieves a CharAcc of 99.25%, compared to 98.61% for CRNN and 98.92% for PaddleOCR v5 [

31]. The improvement in SeqAcc is even more pronounced, reaching 88.6%, while CRNN and PaddleOCR v5 obtain 79.6% and 85.2%, respectively. Regarding the CER, CharSAM-MAE records the lowest value at 0.85%, further confirming its superior recognition capability.

The results demonstrate that CharSAM-MAE exhibits a clear advantage in recognizing complete VIN sequences. The significant improvement in SeqAcc indicates that the structure-aware masking strategy effectively mitigates cumulative errors caused by sparse character sequences, enabling more reliable recognition in industrial continuous-shooting scenarios. To ensure that these improvements are not due to random fluctuations, all experiments were repeated under identical deployment settings, and the variance of CharAcc, SeqAcc, and CER across repeated evaluations remained within ±0.05%. This level of stability is considerably below the performance gains observed in

Table 2, confirming the robustness and statistical reliability of the proposed method.

4.4. Ablation Study

To comprehensively assess the contribution of each component within the proposed CharSAM-MAE framework to VIN recognition, multiple groups of ablation experiments were performed. In addition, training convergence behavior was evaluated using loss and accuracy curve analysis.

Furthermore, to investigate the influence of contrast-enhanced preprocessing on recognition robustness, the original VIN images were processed using contrast enhancement and subsequently evaluated on CharSAM-MAE without modifying any other parameters. As shown in

Table 3, this preprocessing step led to a substantial improvement in recognition performance: character accuracy increased from 87.46% to 99.25%, sequence accuracy rose from 11.72% to 88.3%, and CER was reduced from 12.54% to 0.85%. These results indicate that contrast enhancement effectively strengthens visual feature extraction on sparse character input, particularly for complete VIN sequence recognition.

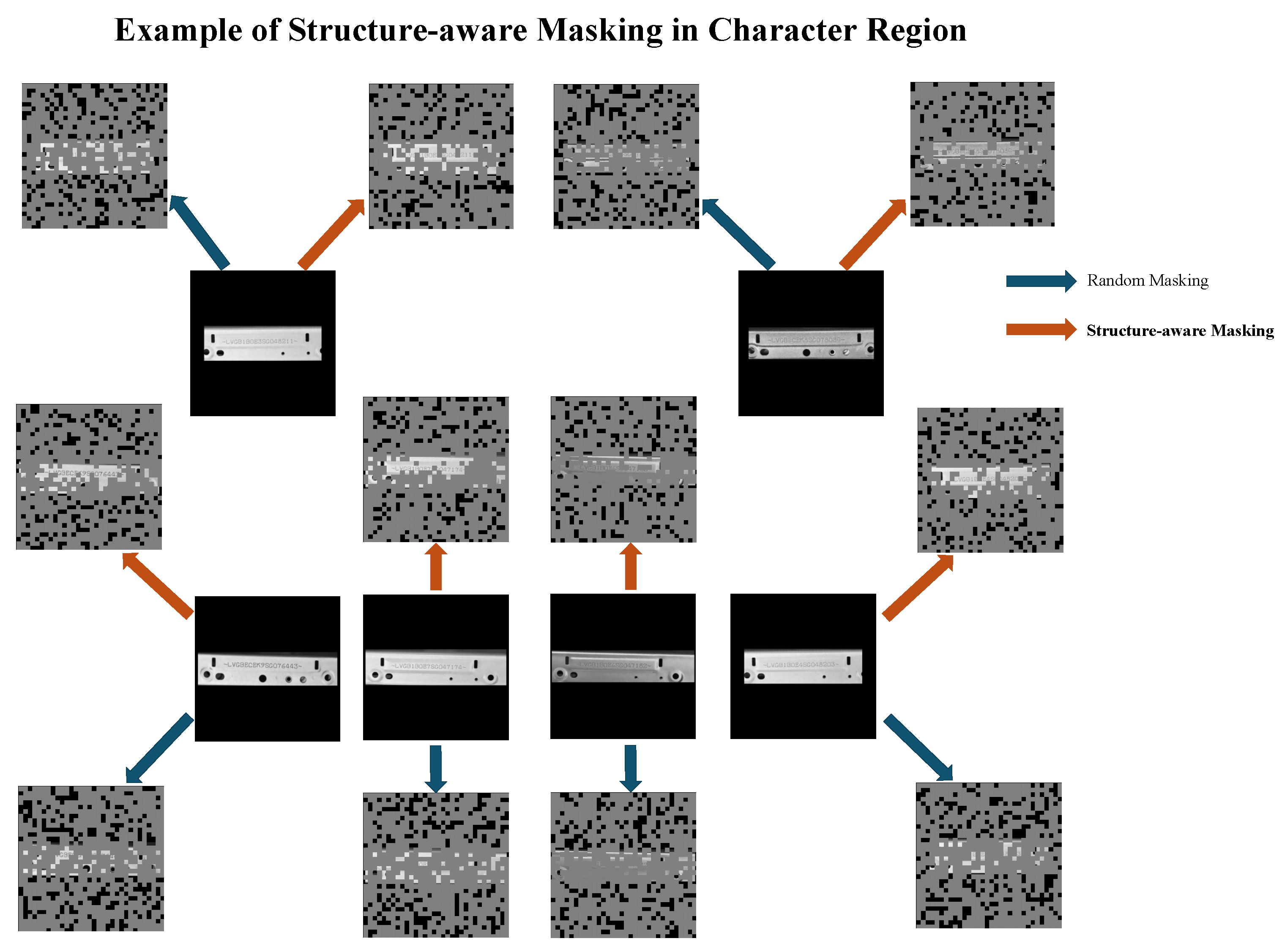

As shown in

Table 4, both the Structure-Aware Masking strategy and the Region-Weighted Reconstruction Loss independently contribute to performance improvement over the baseline MAE configuration, increasing the sequence accuracy to 86.1% and 86.4%, respectively. When the two components are jointly applied, the sequence accuracy further improved to 88.6%, indicating a clear synergistic enhancement rather than a simple additive effect. This confirms that the observed performance gain arises from the intrinsic effectiveness of the proposed architectural design, rather than from model scaling or hyperparameter tuning alone.

To further quantify the effectiveness of the proposed attention-enhanced decoding scheme, an additional comparison was conducted between the standard CTC and A-CTC decoders while all other components were kept unchanged. As summarized in

Table 5, the introduction of multi-head self-attention leads to a consistent improvement in recognition performance, particularly on long VIN sequences.

This confirms that the attention mechanism effectively improves contextual dependency modeling while maintaining the alignment flexibility of the CTC paradigm.

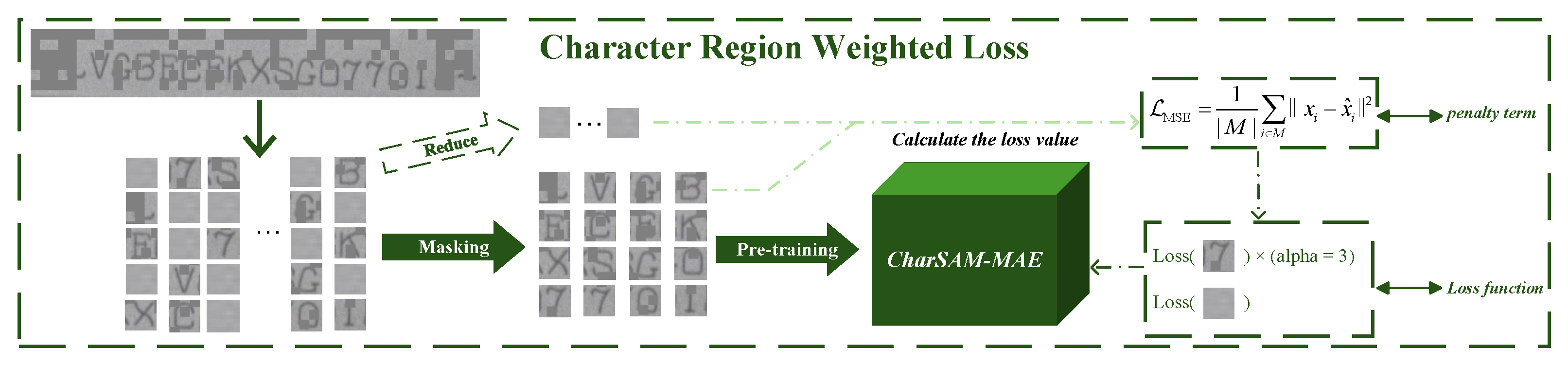

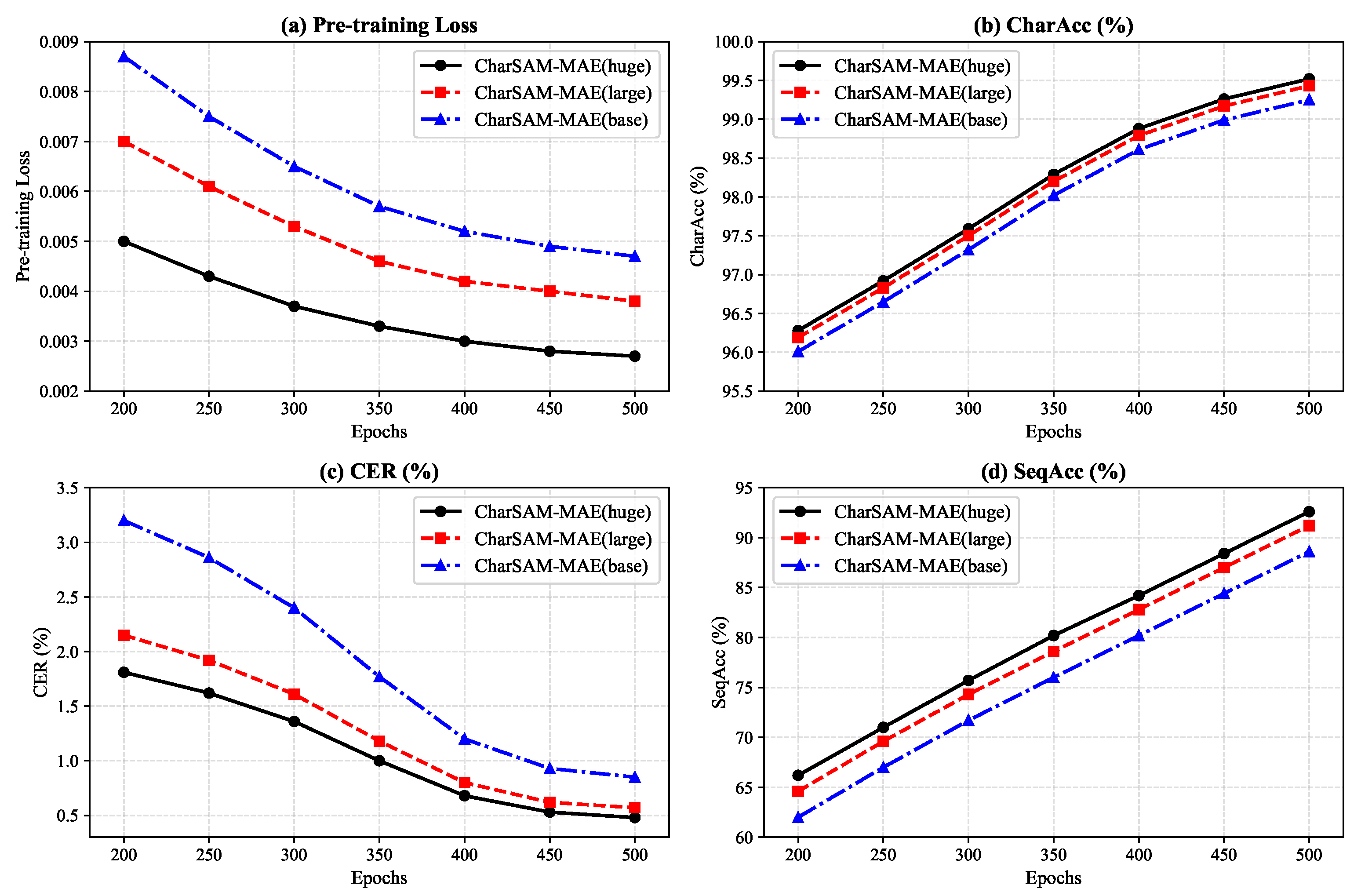

The experiments also examined the effects of model scale, character retention ratio, and loss penalty strategy, as illustrated in

Figure 11. Specifically, CharSAM-MAE was tested in three configurations—base, large, and huge—with parameter sizes of 110.92 M, 328.35 M, and 655.90 M, respectively. Results show that the model capacity increases and the recognition performance consistently improves: the base model achieves a CharAcc of 99.25% and a SeqAcc of 88.6%, the large model reaches 99.43% and 91.2%, and the huge model further attains 99.52% and 92.6%.

It can be observed that enlarging the model scale improves recognition accuracy but also leads to a substantial increase in parameters, requiring a trade-off between performance and computational cost for industrial deployment.

To examine the adaptability of the structure-aware masking strategy to sparse character images, different character retention ratios were explored during pre-training, as shown in

Table 6. The results show that a 25%/75% retention ratio achieves the best balance, giving a CharAcc of 99.25% and a SeqAcc of 88.6%. Higher or lower ratios cause a decrease in SeqAcc—for example, 30%/70% results in 88.2%, while 15%/85% drops to 87.0%.

This experiment investigates the impact of different loss penalty schemes (w/o penalty,

= 2,

= 3,

= 4) on model performance, as shown in

Table 7. The results indicate that the introduction of a penalty factor of

= 3 yields the best results, achieving a CharAcc of 99.25% and a SeqAcc of 88.6%, significantly outperforming the no-penalty setting (SeqAcc 82.6%). Meanwhile, the CER decreases from 1.10% to 0.85%, demonstrating the effectiveness of the penalty strategy in improving the robustness of the recognition.

Comprehensive comparison and ablation experiments demonstrate that the proposed CharSAM-MAE consistently outperforms existing industrially deployable approaches for VIN character recognition, exhibiting superior robustness under low-contrast conditions and in the presence of complex imaging artifacts. The ablation findings further confirm that both the character-region retention ratio and the region-weighted reconstruction strategy are essential to improve the quality of the feature reconstruction and maintain sequence integrity.

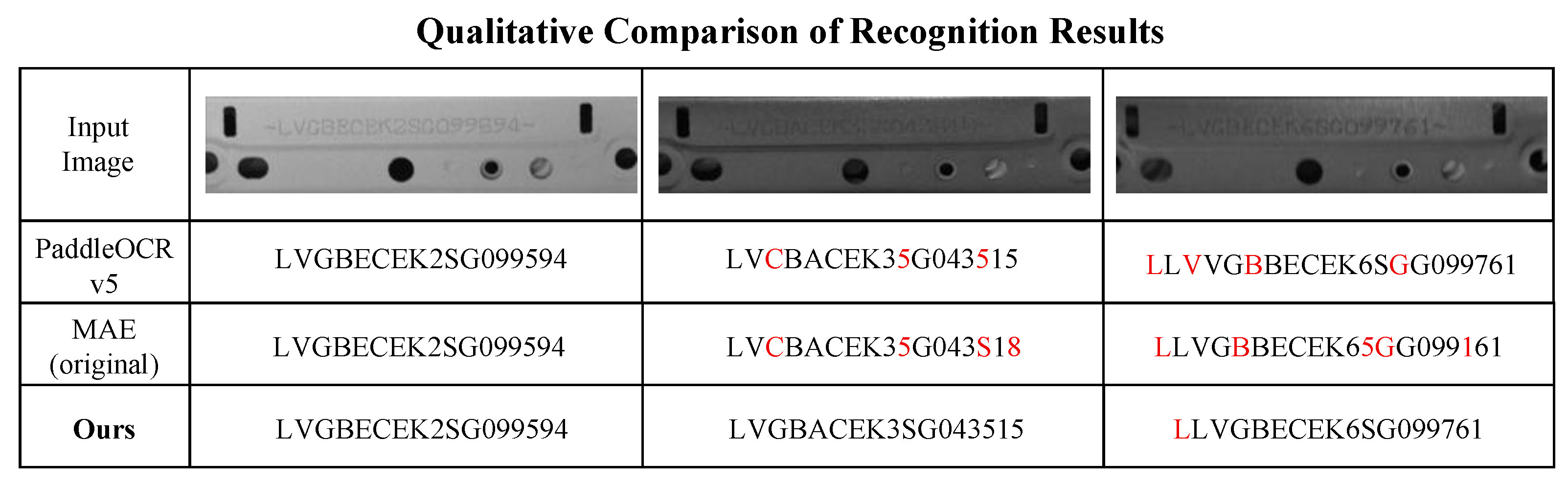

To complement the quantitative analysis, a qualitative comparison is provided to visually illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed modules. As shown in

Figure 12, both PaddleOCR v5 and the original MAE framework suffer character-level recognition errors (highlighted in red), particularly in cases involving weak contrast or character adhesion. In contrast, CharSAM-MAE demonstrates improved structural consistency and significantly reduces misrecognition across all illustrated samples.

It should be noted that, in the third example, all models—including ours—produce duplicated leading characters. This behavior is attributed to motion-induced streaking and optical defocus in the source image, which distorts structural boundaries and impairs separability between adjacent characters at the feature level. Although such degradation lies beyond the modeling scope of self-supervised pre-training, CharSAM-MAE still produces results that are most closely aligned with the ground truth. This observation indicates that the proposed structure-aware masking strategy and the attention-enhanced decoding mechanism substantially improve resilience against extreme imaging degradation, while the remaining inconsistency mainly originates from inherent limitations in the acquisition process rather than from the recognition architecture itself.