1. Introduction

Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) [

1,

2] constitutes a fundamental capability in autonomous robotic systems, enabling the construction of consistent environmental maps while determining the robot’s position within unknown surroundings. Among various sensing modalities, Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) has emerged as one of the most reliable technologies due to its high spatial resolution and robustness in indoor and dynamic environments [

3]. Recent advancements in LiDAR-based SLAM [

4], along with improvements in computational frameworks such as ROS 2, have enhanced real-time map construction and localization performance in mobile robots.

Over the past decade, these developments have led to the emergence of numerous SLAM frameworks within the Robot Operating System (ROS) ecosystem [

5]. Graph-based and optimization-based SLAM approaches have become dominant due to their scalability, flexibility, and suitability for real-time robotic applications. Among the available open-source solutions, SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer are two of the most widely adopted 2D SLAM packages in ROS 2. While both provide robust localization and mapping capabilities, they differ significantly in algorithmic structure, optimization strategies, computational requirements, and parameter configuration complexity.

Despite their popularity, comparative studies that evaluate SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer under identical simulation and real-world conditions remain limited in the literature. Existing works often compare these tools independently, or within isolated scenarios, making it difficult for researchers and developers to determine which SLAM solution is more suitable for specific operational requirements and hardware constraints.

This study aims to address this gap by presenting a comprehensive comparative analysis of SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer using the ROS 2 Humble Hawksbill distribution. Both tools are evaluated in the same Gazebo-based simulation environment and in real indoor scenarios using an identical mobile robot equipped with LiDAR, IMU, and wheel encoder sensors. Key performance metrics—including mapping accuracy, trajectory estimation error, computational load (CPU and memory usage), and transform frame (TF) behavior—are quantitatively measured and compared. The findings offer practical insights into the performance and behavior of both SLAM systems across simulated and physical environments.

The main contributions of this study are as follows:

A unified evaluation framework that compares SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer under identical ROS 2 configurations.

A quantitative analysis of mapping accuracy, trajectory error, and computational load in both simulation and real-world tests.

Experimental insights into the effects of sensor fusion and parameter tuning on SLAM stability and mapping performance.

Practical recommendations for selecting suitable SLAM tools for resource-constrained autonomous robotic platforms.

Based on the algorithmic differences identified in prior studies, this work is guided by the following research hypotheses:

SLAM Toolbox, as a pose-graph SLAM method, will achieve higher accuracy when reliable fused odometry is available, but will degrade sharply when odometry is perturbed.

Cartographer will exhibit stronger sensitivity to a small subset of scan-matching and optimization parameters, making tuning more critical for achieving stable performance.

Due to its continuous scan-to-submap optimization, Cartographer will consume fewer computational resources in real-world conditions but may show increased CPU load in simulation environments.

Cartographer will perform worse in noise-free simulation because its scan matcher relies on natural sensor noise to improve scan-to-scan diversity, whereas SLAM Toolbox—driven by EKF odometry—will maintain stable performance.

These hypotheses directly shaped the experimental design in

Section 3.7 and

Section 3.9, where each algorithm was evaluated under controlled simulation conditions and realistic indoor scenarios, including odometry-perturbation stress tests.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the related works and the basic knowledge for each key subject of this study.

Section 3 describes the methodology based on SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer.

Section 4 discusses the experimental results and their implications.

Section 5 presents the conclusions. Finally, the statements and declarations are provided at the end of the paper.

2. Related Work

This study investigates efficient mapping methods in both virtual and real environments by comparing two prominent SLAM algorithms, SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer, through using LiDAR technology. Technological advancements and algorithmic improvements have enabled autonomous systems to navigate effectively even under challenging environmental conditions. SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer differ fundamentally in their architectural principles: SLAM Toolbox primarily relies on pose-graph optimization and externally provided odometry, whereas Cartographer adopts a submap-based optimization pipeline with tightly integrated IMU support. These distinctions influence their computational load, robustness, and tuning sensitivity, underscoring the importance of comparative evaluations.

Despite several SLAM-related studies in the literature, direct head-to-head evaluations of SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer under identical ROS 2 configurations and consistent simulation–real-world setups remain scarce. This gap highlights the need for comprehensive benchmarking across varied environments to assist researchers and practitioners in selecting suitable SLAM solutions.

LiDAR technology, which measures distances using laser beams through time-of-flight computation, has become indispensable in autonomous vehicles, geographic information systems, and industrial robotics [

6]. Its ability to generate high-resolution point clouds makes it a preferred sensor for SLAM applications, including challenging settings such as featureless tunnel environments [

7]. Early LiDAR systems such as Colidar Mark II, introduced by Hughes Aircraft Company in the 1960s, achieved a range of 11 km and an accuracy of 4.5 m [

8]. Over time, LiDAR evolved from single-beam sensors to sophisticated multi-beam and airborne systems, exemplified by NASA’s GLAS instrument launched in 2003, designed for high-precision elevation mapping from orbit [

9]. The practical value of LiDAR-based navigation gained significant momentum with Stanford University’s Stanley vehicle in the 2005 DARPA Grand Challenge, demonstrating real-world SLAM capabilities [

10]. In addition to academic surveys, practice-oriented overviews of LiDAR-based SLAM techniques and applications are also available in the recent technical literature [

11].

LiDAR-based SLAM algorithms such as GMapping [

6], HectorSLAM [

12], Cartographer, and SLAM Toolbox [

13] gained widespread use due to their resilience in dynamic and low-light environments where vision-based SLAM methods struggle. Further enhancements came from LiDAR Odometry and Mapping (LOAM) [

14], which improved performance through continuous odometry correction. Other research introduced point cloud submapping [

15], graph-based map generation [

16], and multi-sensor fusion that integrates LiDAR with visual and inertial data [

17,

18], significantly improving robustness and accuracy.

Li et al. [

19] proposed a 2D LiDAR SLAM method that integrates Weighted Signed Distance Function (WSDF) maps with the Levenberg–Marquardt optimization technique for scan matching, achieving improved mapping accuracy. Similarly, Murotani et al. [

20] introduced step detection and skid-steer navigation using LiDAR, aligning with the goals of precision mapping and trajectory tracking in complex indoor environments. Dynamic submapping and real-time loop closure approaches have further expanded SLAM capabilities [

21]. Sensor fusion techniques including the Unscented Kalman Filter (UKF) and Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) remain essential components for mitigating sensor noise and uncertainty in SLAM systems [

18,

22]. Huang et al. [

23] presented FOSLAM, which integrates odometry constraints to improve efficiency. Probabilistic techniques such as Rao-Blackwellized and minimax particle filters have further strengthened estimation robustness under uncertainty [

24].

Reinforcement learning combined with SLAM-generated topological maps, as demonstrated by Xue et al. [

25], has advanced real-time decision-making capabilities in autonomous systems. As SLAM systems expand into hazardous, industrial, and GPS-denied environments, studies like Nguyen et al. [

26] have become crucial for evaluating algorithmic performance under diverse operational constraints. These works collectively form the foundation for evaluating the suitability of SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer across simulation and physical environments.

Cartographer, introduced by Google in 2014, supports both 2D and 3D mapping through multi-resolution grid maps, submap optimization, and loop closure detection, enabling high mapping accuracy [

27,

28]. Its real-time processing capabilities and multi-sensor integration make it robust for dynamic scenarios. Hess et al. [

29] demonstrated improvements in global consistency through submap refinement and IMU–LiDAR fusion via branch-splitting and scan matching. Hybrid approaches that combine odometry and Iterative Closest Point (ICP) have also been proposed to reduce motion-induced distortion in LiDAR data [

30].

SLAM Toolbox, developed by Steve Macenski [

31], is optimized for ROS 2 and supports both online and offline mapping. It is recognized for its low memory usage, high update frequency, and suitability for large-scale 2D environments [

32]. Unlike Cartographer, SLAM Toolbox depends heavily on externally provided odometry, often from wheel encoders fused with IMU measurements which make accurate transformation frame (TF) configuration essential for map consistency and localization reliability.

This study leverages these insights by implementing both SLAM algorithms on a unified hardware platform. Odometry from wheel encoders and orientation from the IMU are fused via EKF [

22], enhancing trajectory estimation in indoor settings with limited features. Similar LiDAR–inertial fusion approaches have demonstrated improved SLAM robustness, such as the Virtual Inertial Navigation System framework proposed by Cai et al. [

33], which showed significant performance gains in dynamic environments.

Further supporting this study, Sobczak et al. [

27] evaluated Cartographer’s performance under various sensor configurations in both simulation and real-world tests, concluding that combining 2D LiDAR with IMU and wheel odometry provides a cost-effective yet highly accurate mapping solution for indoor robotics. Likewise, EKF’s capability to linearize non-linear motion models offers superior estimation stability compared to basic Kalman filtering techniques. ROS 2, particularly the Humble Hawksbill distribution, provides a scalable and modular middleware architecture to support such multi-sensor SLAM implementations [

34]. Key parameters affecting SLAM performance include submap resolution, loop closure frequency, scan matching thresholds, and transform timeouts [

35], which require careful tuning for optimal results.

Cartographer’s Lua configuration file allows detailed tuning of SLAM parameters to match sensor characteristics and environmental conditions (see

Section 3.5).

From an algorithmic standpoint, the performance gap observed in simulation is consistent with how Cartographer internally constructs maps. Cartographer relies heavily on real-time scan matching and IMU-constrained pose extrapolation. Its Ceres-based scan matcher performs best when consecutive scans contain small but natural variations, allowing the optimizer to converge toward a stable minimum. In noise-free simulation, however, LiDAR measurements become overly uniform, reducing scan-to-scan diversity and causing the optimization to converge more slowly or become over-sensitive to small geometric features. Furthermore, Cartographer’s submap-based architecture depends on continuous alignment between IMU-extrapolated poses and LiDAR scans, and the absence of realistic IMU noise can disrupt the balance between these two information sources. These architectural characteristics explain why Cartographer underperforms under idealized simulation conditions compared to real-world environments.

3. Methodology

This study is based on the Robot Operating System 2 (ROS 2), an open-source, modular, and real-time middleware framework widely adopted in modern robotic applications. Specifically, the Humble Hawksbill distribution was utilized due to its long-term support (LTS), deterministic execution model, and enhanced support for real-time communication and control. ROS 2 provides a Data Distribution Service (DDS)-based messaging architecture that enables configurable Quality of Service (QoS) profiles for sensor topics such as /scan, /imu, and /odom.

The system architecture leverages ROS 2 packages including slam_toolbox, cartographer_ros, robot_state_publisher, joint_state_publisher, tf2_ros, rviz2, and nav2_bringup.

Table 1 summarizes the installed ROS 2 packages used for mapping, visualization, sensor fusion, and data logging.

3.1. Mathematical Background of SLAM

Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) is formulated as a Bayesian estimation problem expressed as

where

xt is the robot’s pose at time t;

m is the map of the environment;

z1:t denotes the sequence of all sensor observations up to time t;

u1:t denotes the sequence of control inputs.

SLAM operates through:

Two main algorithmic paradigms form the basis of this study:

Pose-Graph Optimization (SLAM Toolbox): Constructs a graph of robot poses and constraints, optimized through loop closure and scan-to-map matching.

Submap-Based Optimization (Cartographer): Generates local submaps, performs real-time scan matching, and periodically optimizes globally using IMU-constrained optimization.

3.2. Sensor Architecture and Data Fusion

The robot incorporates a 360° LiDAR, an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), and wheel encoders. These sensors are fused using an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) from the robot_localization package to produce a stable odometry estimate.

A correct transformation frame (TF) structure is essential for consistent SLAM operation:

Map → Odom → Base_footprint → Base_link → Laser_frame

This hierarchy ensures accurate spatial alignment across all sensor modalities.

Section 3.9.1 includes the validated TF tree used in this study.

3.3. Cartographer Pipeline Overview

Cartographer processes sensor data through two main components:

Local SLAM

Real-time scan matching using the Ceres solver;

Motion filtering and pose extrapolation;

Construction of local submaps;

Global SLAM

Cartographer can operate with or without externally provided odometry, enabling broad applicability across platform types.

3.4. SLAM Toolbox Pipeline Overview

SLAM Toolbox operates as a pose-graph SLAM system with the following properties:

Scan-to-map matching for continuous refinement;

Loop closure optimization for global consistency;

Supports synchronous and asynchronous modes;

Relies heavily on externally fused odometry (EKF).

Accurate TF broadcasting is essential for achieving alignment and minimizing distortion during mapping.

3.5. Cartographer Configuration (Lua Parameters)

Table 2 summarizes the key parameters defined in the Lua configuration file used for Cartographer.

Cartographer Parameter Tuning Protocol (Systematic and Fair Tuning)

Cartographer includes more than 40 adjustable configuration parameters (

Table 2), covering frame definitions, scan-matching thresholds, optimization weights, sampling ratios, and submap generation settings. Since not all parameters directly influence mapping accuracy, a systematic, literature-supported tuning strategy was implemented to ensure fairness and avoid suboptimal settings.

Identification of high-impact parameters:

Based on Cartographer’s official documentation, in [

27,

29], and other benchmark studies, the following parameters were identified as the primary determinants of mapping accuracy and drift:

num_accumulated_range_data;

translation_weight, rotation_weight;

motion_filter.max_time_seconds;

voxel_filter_size;

huber_scale;

min_range, max_range;

submap_resolution.

Structured parameter sweep (coarse-to-fine search):

A two-stage tuning process was applied:

Performance criteria:

For each configuration, the following were measured:

Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE)

Loop-closure correctness;

Submap alignment score;

Real-time CPU utilization;

Consistency of pose graph.

Stopping condition (performance ceiling):

Tuning iterations stopped when further parameter variation produced <2% improvement in ATE or map alignment metrics, indicating proximity to the performance ceiling.

The tuning process focused on the subset of parameters in

Table 2 that directly influence scan-matching and submap optimization, while system-level parameters were held constant to ensure fair comparison.

The parameter sweep ranges used during tuning are summarized in

Table 3.

3.6. SLAM Toolbox Configuration Modes

Table 4 provides the configuration files and corresponding use cases for SLAM Toolbox.

3.7. Simulation Experiments

To clearly separate virtual and physical evaluations, all simulation-related configuration, procedures, and results are consolidated under this subsection.

3.7.1. Simulation Environment Specification

A consistent virtual environment was created in Gazebo to ensure comparability between both SLAM algorithms. Key properties include the following:

Indoor world size: approximately 6 × 8 m.

Robot max velocity: 0.25 m/s.

Static obstacles: walls, corners, and narrow passages.

Controlled lighting conditions and noise-free sensor simulation.

Identical URDF, sensors, and TF configuration.

Manual teleoperation via/cmd_vel.

3.7.2. Simulation with the SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer

This subsection explains how to perform robot simulation and mapping in a virtual environment using both the SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer algorithms within the ROS 2 framework. The simulation environment was created using Gazebo and visualized through RViz, enabling preliminary testing of sensor integration, algorithmic behavior, and system stability before real-world deployment. The robot model, environment, and sensor configurations were kept identical for both SLAM approaches to ensure a fair comparison.

The robot’s structure was defined using URDF (Unified Robot Description Format) and Xacro (XML Macros) files, which describe the physical components, sensor placements, and kinematics of the robot. The mapping results obtained by SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer in this shared virtual environment are analyzed in the following subsections.

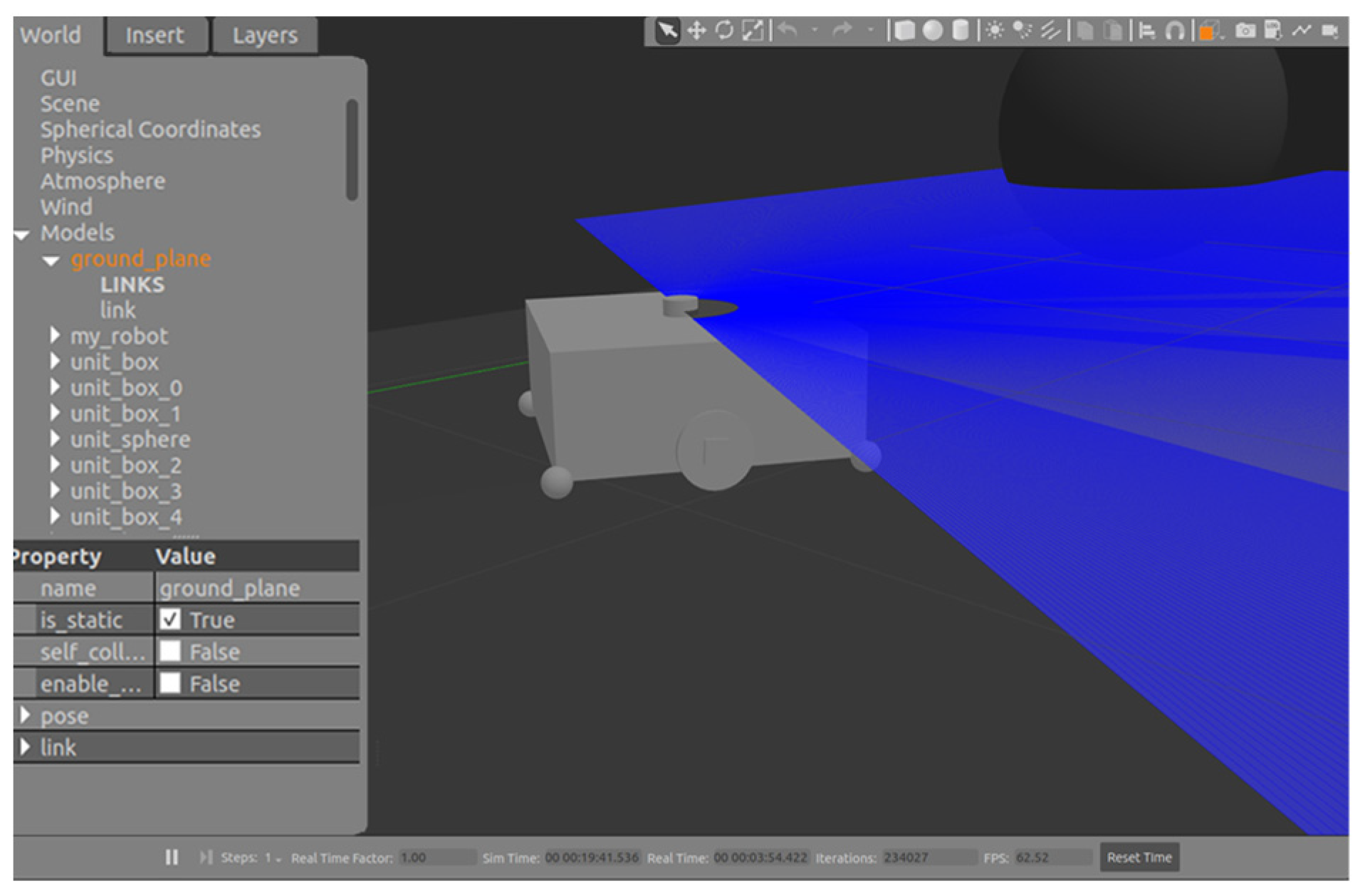

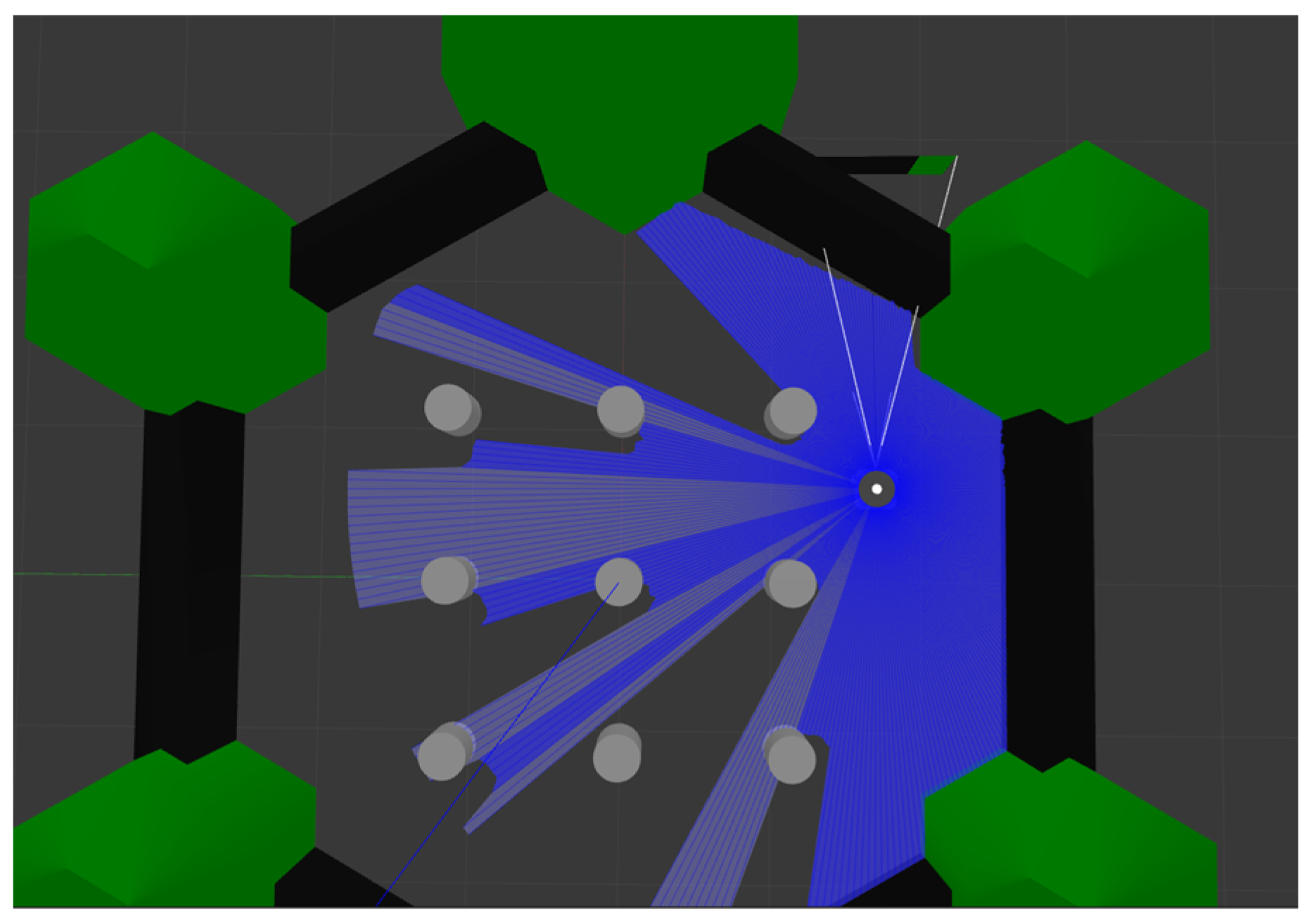

The physical structure and sensor placement of the robot used in this study were defined using URDF and Xacro files. These files describe the robot’s mechanical components including the base, wheels, and sensors in XML format, which were then visualized and simulated within the Gazebo environment (see

Figure 1 and

Figure 2).

A virtual indoor environment was created in Gazebo, where the robot navigated through obstacles to simulate a real-world mapping scenario. This environment was saved as a ‘.world’ file and reused for both SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer simulations to maintain experimental consistency. After validating the robot’s movement and sensor operations, the mapping process was performed using both SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer algorithms in separate test runs. Each algorithm was configured with its respective parameter files. For SLAM Toolbox, the ‘mapper_params_online_async.yaml’ configuration was used, while for Cartographer, a customized ‘.lua’ configuration file was employed.

The robot was teleoperated in the simulation environment, and the resulting maps were visualized in RViz for both cases. This simulation process enabled the evaluation and comparison of both SLAM algorithms under identical conditions prior to real-world deployment.

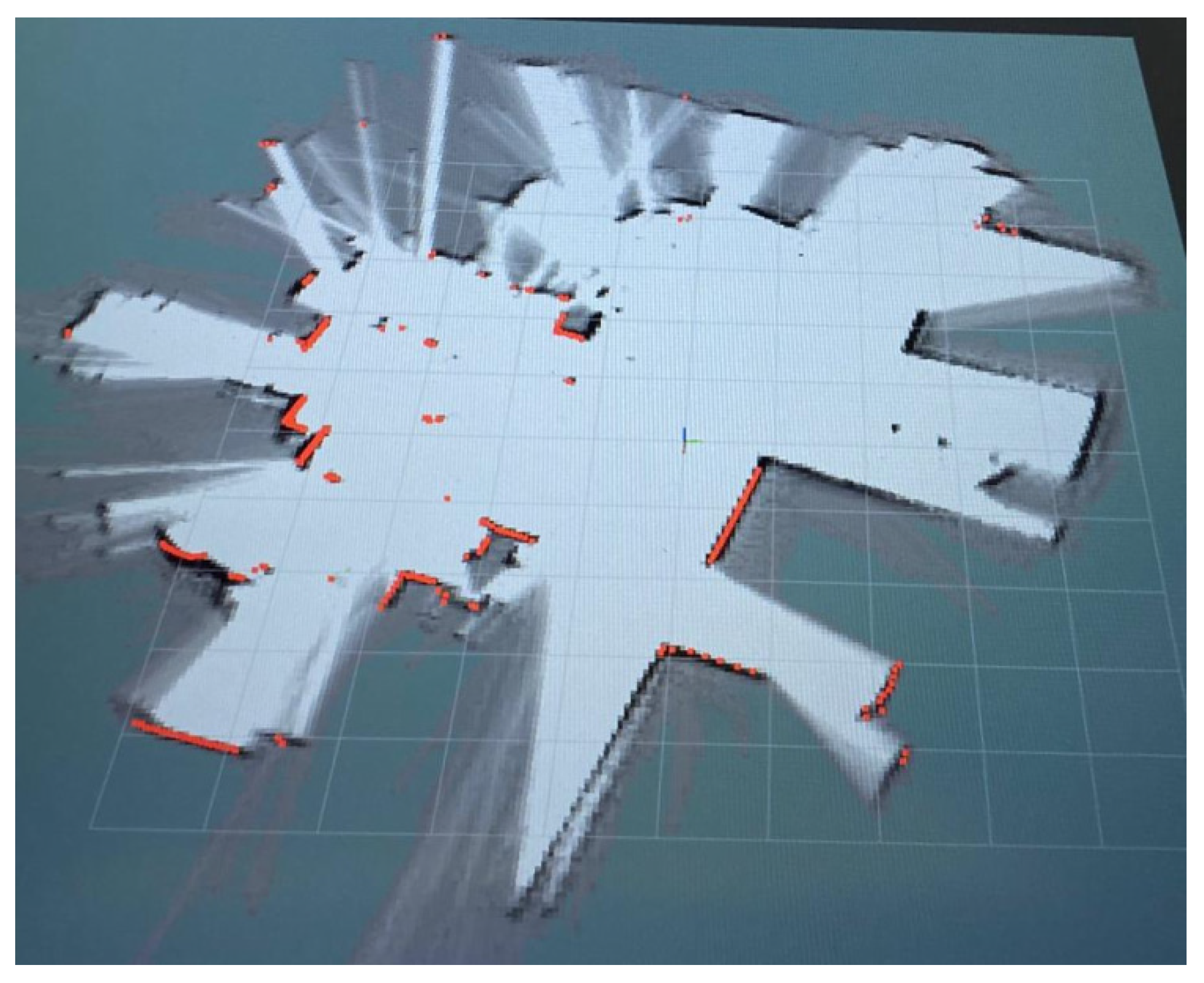

3.7.3. Simulation Results and Comparative Evaluation

The use of a controlled simulation environment in Gazebo, paired with RViz for real-time visualization, provided a valuable platform for evaluating the behavior and performance of both SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer under identical conditions (see

Figure 3). This environment enabled the verification of sensor integration, kinematic accuracy, TF transformations, and mapping behavior prior to real-world deployment, minimizing risks and configuration errors.

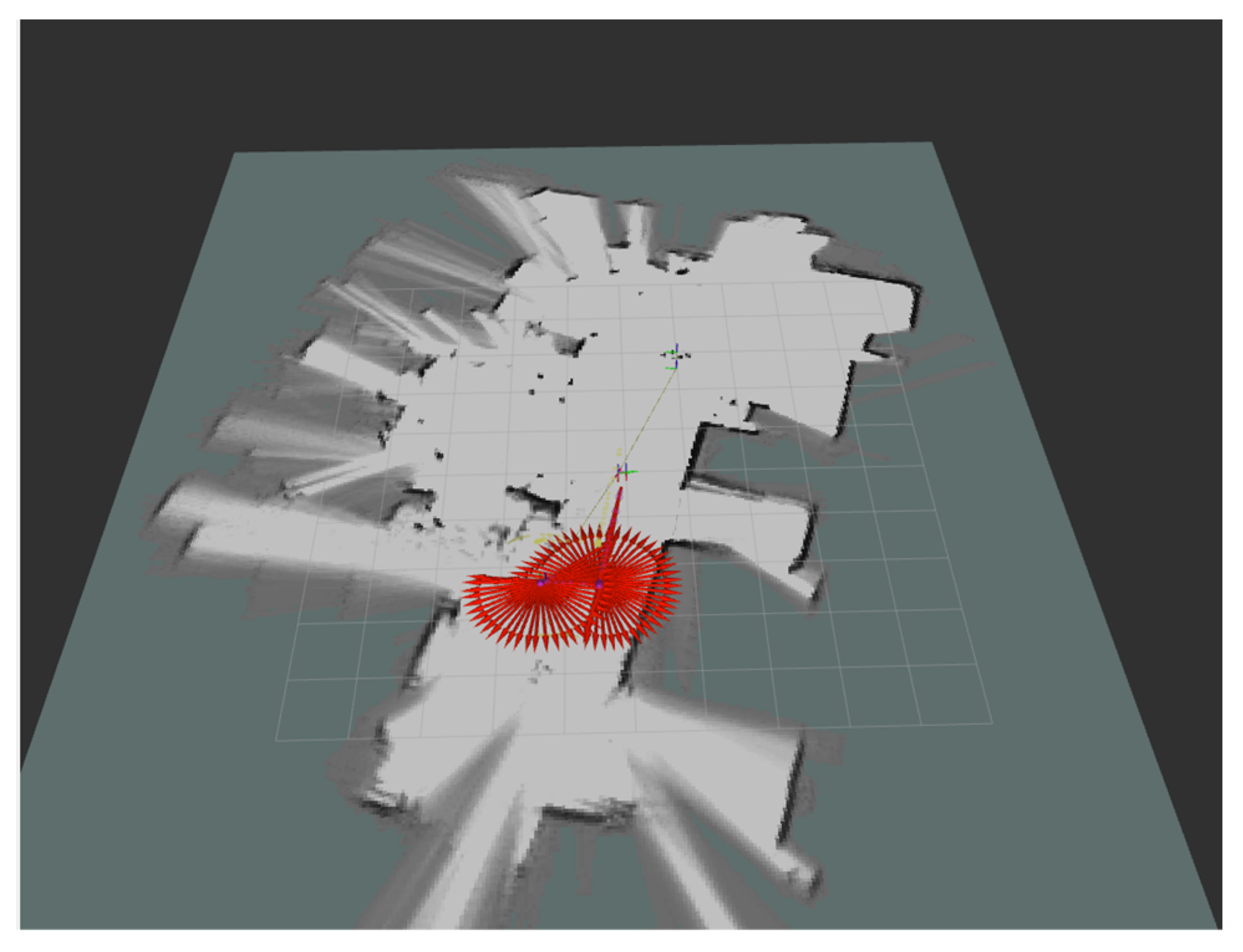

The SLAM Toolbox demonstrated superior odometry integration in the simulation, effectively utilizing simulated encoder and IMU data to produce a smoother and more consistent map (see

Figure 4).

In contrast, Cartographer, while generally efficient in real time applications, exhibited less consistent trajectory estimation in the simulation due to its dependence on internal LiDAR odometry, which proved to be more susceptible to error in the simulated noise-free environment (see

Figure 5). Because Cartographer relies on internal scan-matching odometry, the absence of natural sensor noise that typically improves scan registration may cause over-sensitivity in idealized simulation environments.

3.8. Performance Metrics

To evaluate and compare SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer, the following performance metrics were used:

Calculated as the root-mean-square error (RMSE) between the estimated and ground-truth trajectories in simulation.

Measured using htop and executor cycle logs.

Computed using timestamp differences between TF publishing and consumption.

Assessed based on loop-closure correctness, submap alignment accuracy, and deformation artifacts.

3.9. Real-World Experiments

This subsection groups all real-world experiments, including robot configuration, operational procedures, stress testing, and mapping results for both SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer.

3.9.1. Real-World Mapping Using SLAM Toolbox

The real-world SLAM implementation was carried out in indoor environments where Global Positioning System (GPS) data is unavailable. To enable autonomous localization and map generation under these conditions, the robot leveraged a sensor fusion architecture, integrating data from an Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU) and wheel encoders using an Extended Kalman Filter (EKF).

The EKF algorithm was employed to estimate the robot’s pose in real time by combining high-rate but drift-prone inertial measurements with lower-frequency encoder data. This fusion process utilized Jacobian-based linearization to handle the nonlinearity of motion and measurement models, thereby enabling accurate state prediction and correction. This approach significantly mitigated accumulated odometric errors and allowed the SLAM Toolbox to maintain a stable and accurate pose estimate during mapping. The fused odometry data served as the primary localization input to the SLAM Toolbox, ensuring consistent map alignment and trajectory estimation throughout the mission.

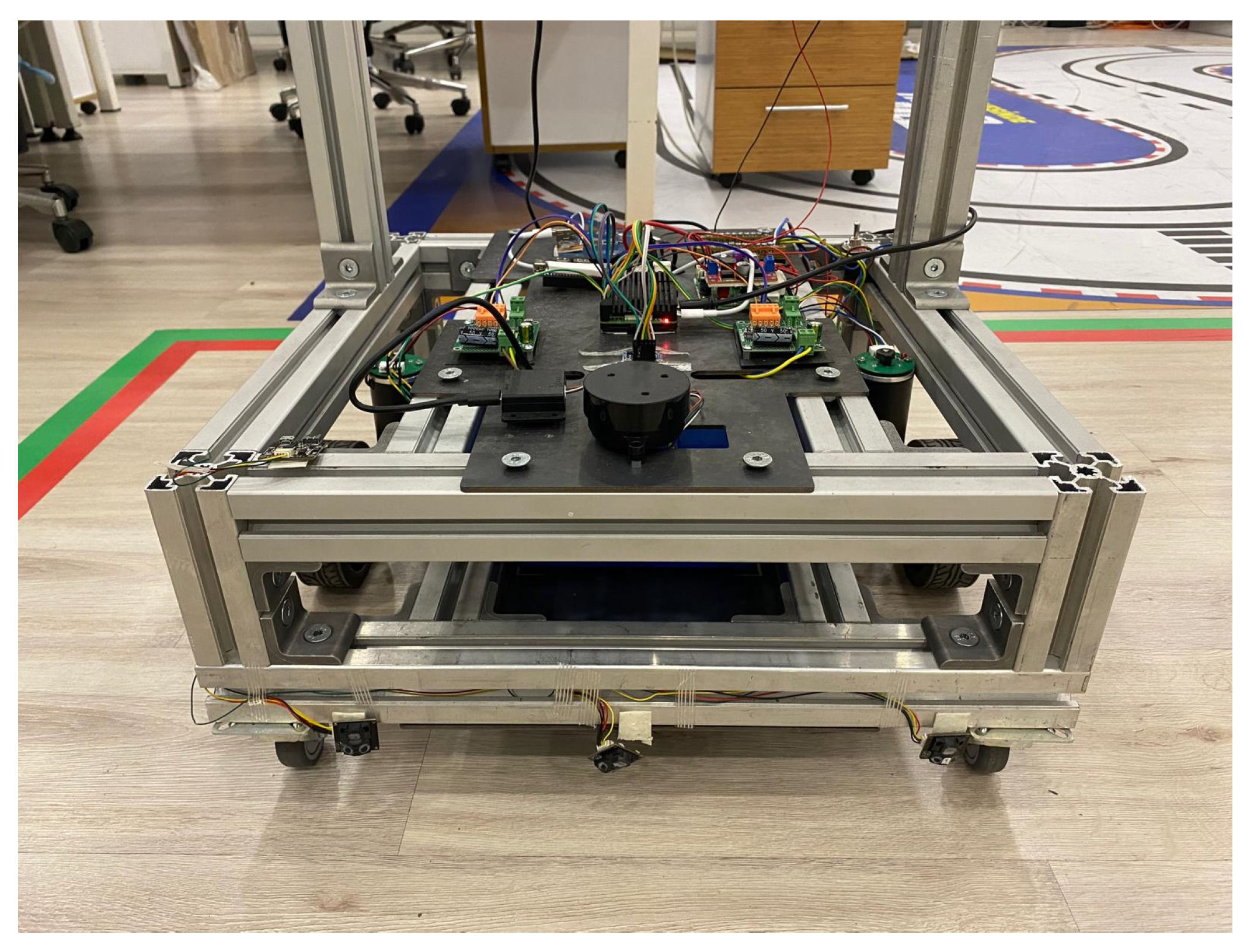

Figure 6 shows the actual physical configuration of the robot used in indoor mapping experiments, while

Figure 7 provides its corresponding schematic representation used for visualization and software configuration purposes.

The use of Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) is pivotal in achieving precise odometry information by mitigating sensor noise and drift. In real-world deployments of SLAM Toolbox, the accuracy of Transform Frames (TFs) and frame hierarchies becomes equally critical, as they govern spatial relationships between sensors and the robot base. Transform frames in the ROS 2 ecosystem are generally categorized into static and dynamic types. Static frames such as /base_link and /base_footprint represent fixed spatial relationships between the robot’s body and its onboard sensors. In contrast, dynamic frames, such as /odom and /laser, are updated in real time and reflect the robot’s motion through the environment. The integrity of these dynamic updates is crucial, especially when odometry sources change or shift due to sensor noise or motion irregularities.

Additionally, the parent–child relationships defined in the TF tree must be configured accurately to ensure correct data propagation across frames. Misaligned or misconfigured TF relationships can result in spatial distortions during SLAM execution. These frame hierarchies can be visualized and validated using RViz, as illustrated in

Figure 8, which shows a correctly established TF tree used during our SLAM Toolbox experiments.

The mapping process is initiated by configuring the SLAM Toolbox parameter file with appropriate frame names and operational thresholds. In this study, a custom configuration was created for real-time mapping, incorporating the following data sources:

EKF-based odometry derived from IMU and encoder fusion.

Real-time laser scan data from the /scan topic.

Correctly defined and broadcasted TFs.

Robust topic communication validated via ROS 2 tools.

Figure 9 presents the hardware setup based on a Raspberry Pi 4, including sensor modules and their corresponding TF sources. This schematic clarifies how each sensor contributes to the TF structure used in mapping.

Operational validation was conducted using rqt_graph, a tool that provides visual insights into active ROS 2 nodes and topic connections. The runtime configuration of the system during mapping is shown in

Figure 10.

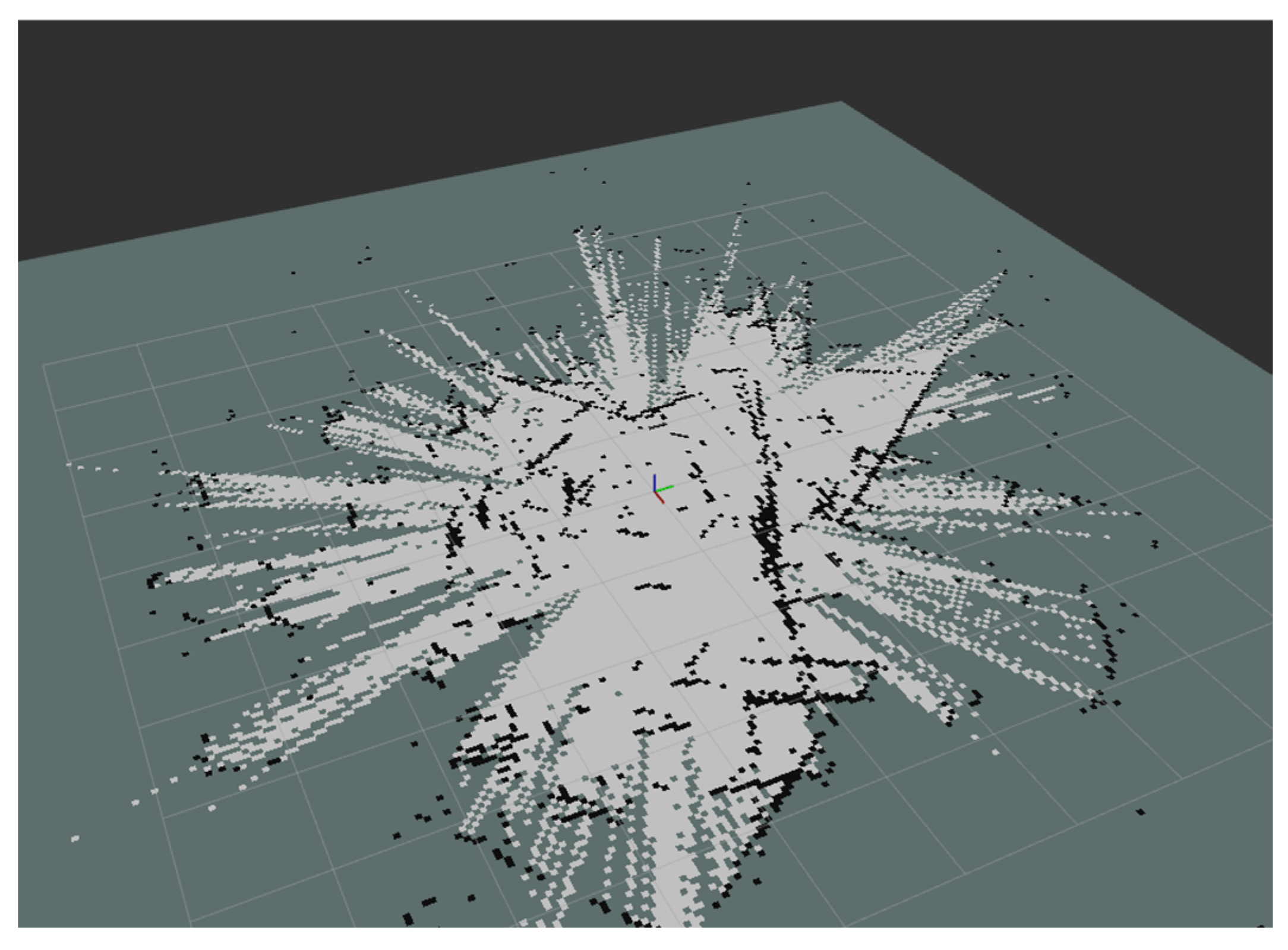

Although SLAM Toolbox offers robust mapping capabilities in dynamic environments, it is highly sensitive to TF misconfigurations and odometry inconsistencies. Incorrect or noisy data from any source can significantly degrade mapping quality. This sensitivity is demonstrated in

Figure 11, where a misaligned odometry source resulted in a distorted and unusable map. Conversely,

Figure 12 displays a correctly generated map using validated odometry and TF settings, highlighting the critical impact of accurate configuration.

3.9.2. Odometry-Perturbation Stress Test (Wheel-Slippage Scenario)

To experimentally validate the vulnerability of SLAM Toolbox to unreliable external odometry, a dedicated stress test was conducted by intentionally perturbing the wheel-encoder odometry. In this test, artificial drift, pose jumps, and intermittent discontinuities were injected into the odometry stream to emulate real-world wheel slippage conditions and low-friction floor interactions.

When this corrupted odometry was used as the primary localization source, the SLAM Toolbox pose-graph diverged, producing the severely distorted map shown in

Figure 11. This demonstrates the algorithm’s strong dependence on high-quality, well-fused odometry.

After restoring the correct EKF-fused odometry, SLAM Toolbox immediately recovered and produced the clean and consistent map shown in

Figure 12. This confirms that the failure was not due to LiDAR or TF issues but directly caused by degraded odometry input.

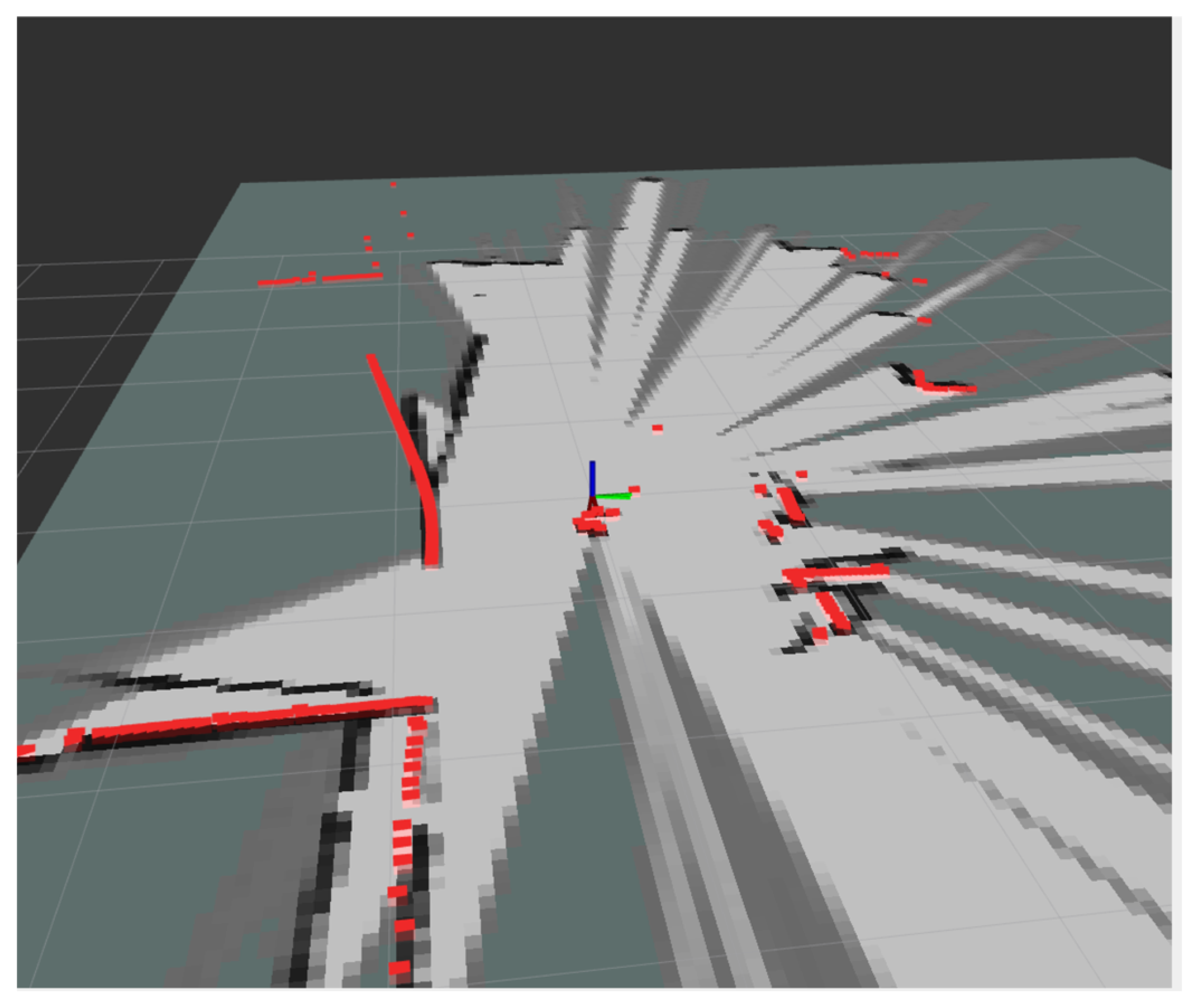

3.9.3. Real-World Mapping Using Cartographer

Cartographer is an open-source SLAM framework developed by Google that supports both 2D and 3D mapping in real time. Its architecture is designed for adaptability in complex and dynamic environments. Compared to SLAM Toolbox, Cartographer offers certain advantages in terms of integration simplicity and automated transformations (TFs). Notably, it can operate without externally provided odometry, relying instead on LiDAR-based scan matching and internal pose estimation mechanisms.

One of Cartographer’s strengths lies in its automated transform tree (TF) broadcasting, reducing the configuration burden often required in SLAM Toolbox. Additionally, Cartographer integrates its mapping pipeline tightly with the sensor data stream, supporting robust scan-to-submap matching and global loop closure mechanisms.

The mapping performance is governed by several configurable parameters located in the Lua configuration file, which determines behaviors such as submap resolution, scan matching thresholds, and loop closure frequency. However, incorrect parameter tuning or inappropriate LiDAR frequency settings may introduce artifacts and noise in the generated maps (as illustrated in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14). These issues emphasize the importance of careful calibration and environment-specific tuning.

When correctly configured, Cartographer achieves high-speed and high-resolution mapping in indoor scenarios. The operational ROS 2 nodes and topic communications during the real-world Cartographer deployment are visualized via rqt_graph, as shown in

Figure 15. The node structure demonstrates the system’s modularity and its ability to maintain real-time performance even under high-frequency data streaming.

3.10. Comparative Feature and Performance Tables

To facilitate a structured comparison between Cartographer and SLAM Toolbox,

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7 summarize their respective feature sets and performance metrics. These tables aim to support informed selection based on system requirements and operational constraints.

Feature Comparison Summary. The following

Table 5 outlines a qualitative comparison between SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer, focusing on flexibility, computational efficiency, and integration capabilities with external data sources.

Simulation-Based Performance Evaluation Results. The following

Table 6 summarizes the performance comparison between SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer based on computational efficiency, mapping accuracy, and responsiveness in real time applications within a simulated environment using Gazebo.

Real-World Performance Evaluation Results. The following

Table 7 summarizes the performance comparison between SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer based on computational efficiency, mapping accuracy, and responsiveness in real-time applications conducted on a physical robot in real indoor environments.

Following the computational and trajectory-based comparisons in

Table 5,

Table 6 and

Table 7, a complementary set of multi-dimensional map-quality metrics was evaluated to objectively quantify mapping performance beyond ATE and qualitative visual inspection. These metrics are widely adopted in the SLAM literature and capture different aspects of map completeness, geometric accuracy, and global consistency.

Specifically, the following three metrics were computed for both algorithms:

The ratio between the occupied and free-space regions successfully mapped by the algorithm relative to the total traversable indoor area. Higher values indicate more complete exploration.

A correlation-based similarity score comparing the produced occupancy grid with an annotated reference layout of the indoor environment. This metric assesses global geometric correctness and wall-alignment accuracy.

The mean positional discrepancy between loop-closure revisit points and their corresponding initial positions, reflecting the system’s global drift and loop-closure stability.

The results for these metrics are summarized in

Table 8.

4. Discussion

The comparative analysis of SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer reveals several important insights regarding how algorithmic design choices affect mapping performance, computational efficiency, and robustness in both simulated and real-world environments. The results demonstrate that the two frameworks behave differently not only because of parameter tuning or sensor configurations, but primarily due to their fundamental architectural principles.

In the simulation environment, SLAM Toolbox consistently produced smoother trajectories and higher-quality maps (

Table 6), which can be attributed to its strong reliance on externally fused odometry from the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF). Because Gazebo provides idealized encoder and IMU signals with minimal noise, EKF can deliver highly stable pose estimates. This advantage directly benefits SLAM Toolbox’s pose-graph optimization, explaining why its Absolute Trajectory Error (ATE) was significantly lower than Cartographer in simulation (0.13 m vs. 0.21 m). These findings are consistent with earlier reports indicating that hybrid odometry fusion improves map consistency in structured and noise-free environments [

18,

22].

Conversely, Cartographer performed more efficiently in real-world experiments, achieving lower CPU usage and faster map construction (

Table 7). This behavior aligns with its architectural design, which prioritizes real-time scan-to-submap matching and includes IMU-based motion compensation. Real sensor data inherently contains small variations and natural noise, which help Cartographer’s scan matcher converge more accurately—unlike simulation, where noise-free conditions reduce scan-to-scan diversity and may cause over-sensitivity. This observation is also in agreement with the findings of Hess et al. [

29] and Sobczak et al. [

32], who noted that Cartographer’s performance improves in realistic environments with richer sensor dynamics.

In addition, the multi-dimensional map-quality indicators reported in

Table 8—namely map coverage, structural consistency, and revisit accuracy—confirm that both algorithms produce globally consistent and practically usable maps, with SLAM Toolbox achieving slightly higher geometric fidelity and lower revisit error under the tested conditions.

Because Cartographer is highly sensitive to a small set of core optimization parameters, its tuning was performed using a structured parameter sweep (Section Cartographer Parameter Tuning Protocol (Systematic and Fair Tuning)), ensuring that reported performance differences are due to algorithmic characteristics rather than insufficient tuning.

The odometry-perturbation experiments (

Section 3.9.2) further confirmed that SLAM Toolbox degrades sharply under wheel-slip-like disturbances, supporting our claim that the method is inherently more vulnerable to external odometry failures.

The contrasting performance of both algorithms highlights a clear trade-off:

SLAM Toolbox offers higher mapping accuracy and better loop-closure stability when reliable odometry is available, but at the cost of higher CPU usage and slower map updates.

Cartographer, by comparison, provides faster processing and lower resource consumption, making it suitable for real-time applications on embedded hardware, yet remains more sensitive to parameter tuning and sensor misalignment.

These trade-offs indicate that algorithm selection should be guided by the operational context. For example, SLAM Toolbox may be more appropriate for indoor mobile robots operating in dynamic environments where precise odometry is available, whereas Cartographer may be preferred in scenarios requiring high-speed mapping with moderate computational resources.

Despite producing reliable insights, this study is subject to several limitations. The experiments were conducted using a single robot platform, one LiDAR model, and a limited variety of indoor layouts, which may restrict generalizability. The Raspberry Pi 4 used as the onboard computer also imposes computational constraints that may influence CPU and RAM measurements. Furthermore, dynamic obstacles were limited, and no outdoor or large-scale environments were tested. Future work should expand these evaluations to different robot types, sensor combinations, and diverse indoor–outdoor scenarios to assess broader applicability.

5. Conclusions

This study conducted a comparative evaluation of two prominent ROS 2-based SLAM frameworks—SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer—using identical robot hardware, sensor fusion architecture, and experimental conditions in both simulation and real-world environments. The results demonstrate that the differences observed between the two algorithms stem primarily from their architectural design choices rather than from ROS 2 configuration or sensor selection.

Overall, SLAM Toolbox produced more stable and consistent mapping results across both simulation and physical tests due to its reliance on externally fused odometry through the Extended Kalman Filter. This external odometry support allowed it to maintain accurate pose estimates even in dynamic or noise-free environments. In contrast, Cartographer delivered faster map generation and lower computational load in real-world experiments, benefiting from its integrated scan-to-submap matching pipeline. However, its mapping quality degraded significantly in simulation without realistic sensor noise, and its performance remained highly sensitive to parameter tuning.

Key Contributions of This Study:

A unified experimental framework was designed to compare SLAM Toolbox and Cartographer under identical ROS 2 Humble configurations.

Quantitative and qualitative evaluations were conducted in both Gazebo simulation and real-world indoor environments using LiDAR–IMU–encoder fusion.

The study identifies the conditions under which each SLAM algorithm performs optimally and highlights their respective limitations in practical use.

The results provide actionable guidance for researchers and developers selecting suitable SLAM tools based on computational constraints, sensor fidelity, and application environments.

Future research will extend this comparison to 3D SLAM frameworks, evaluate performance on alternative hardware platforms, and explore multi-robot SLAM coordination. Additionally, benchmarking under outdoor and large-scale environments may offer further insight into the scalability and generalization of each SLAM solution. Future work will also investigate hybrid SLAM pipelines that combine the fast scan-to-submap matching of Cartographer with the odometry-based stability of SLAM Toolbox. Moreover, we plan to incorporate image-based and information-theoretic map quality metrics such as structural similarity (SSIM) and map entropy to obtain more fine-grained quantitative evaluations. Finally, reinforcement learning-guided exploration strategies and experiments in highly dynamic environments with moving obstacles and significant lighting changes are also considered as promising directions for future research.