Yolov8n-RCP: An Improved Algorithm for Small-Target Detection in Complex Crop Environments

Abstract

1. Introduction

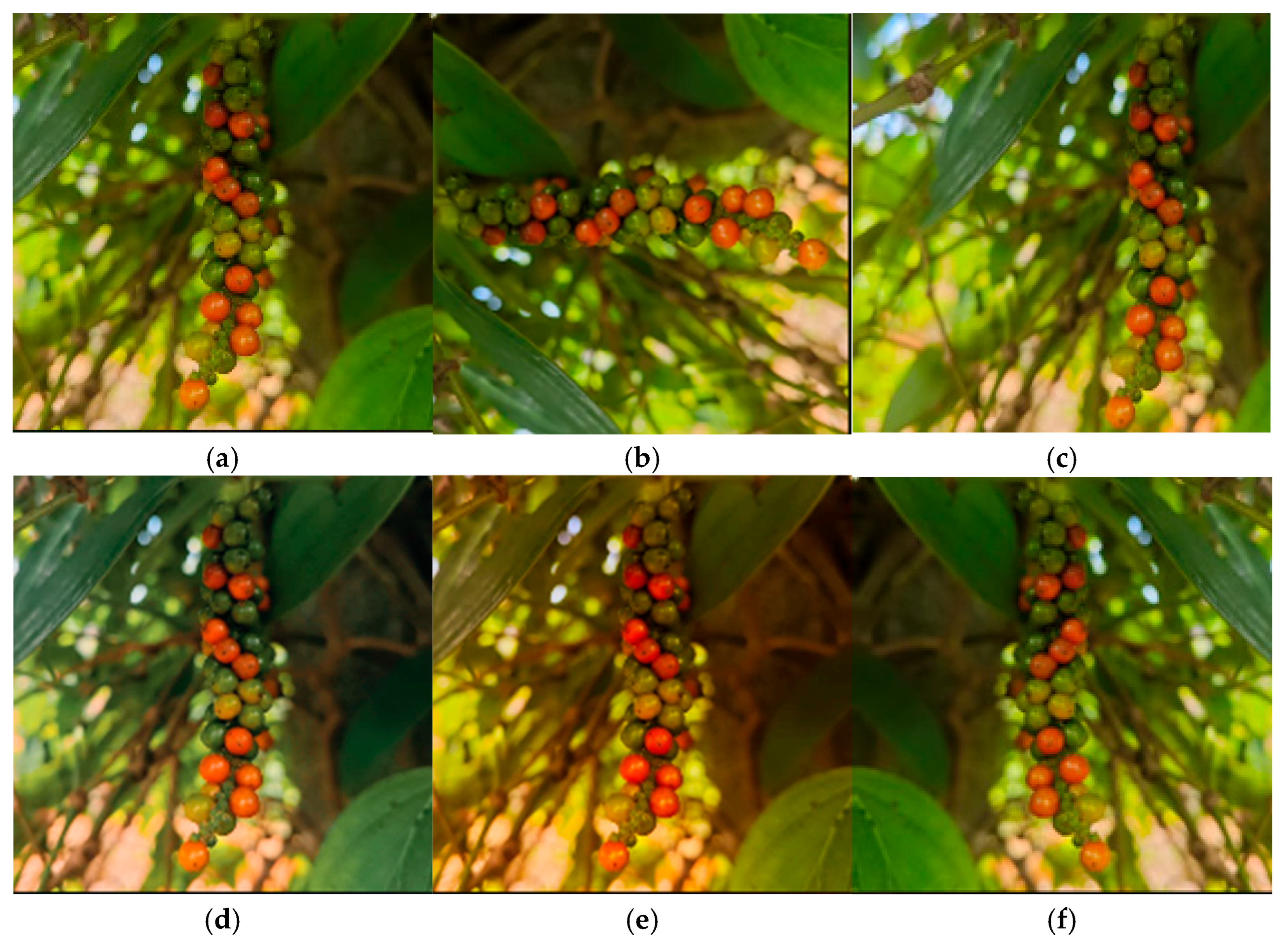

- Dataset construction: A multi-condition pepper dataset is established, covering 3 collection dates (25 June–15 July 2024), 2 plots in Haikou Qiongshan District, and variable lighting (600–1500 lux) and humidity (65–75% RH) conditions. After data augmentation (rotation, translation, brightness adjustment), the dataset expands to 4758 images—filling the gap of scarce labeled datasets for pepper detection in complex farm environments.

- Algorithm innovation: The Yolov8n-RCP algorithm is proposed with two key optimizations: (a) The C2F_RVB module compresses parameters to 3.46 M (comparable to Yolov8n baseline) while preserving high-frequency details of small peppers; (b) The Coordinate Attention (CA) mechanism is embedded in the backbone to suppress low-level leaf noise, improving recall by 6.1%.

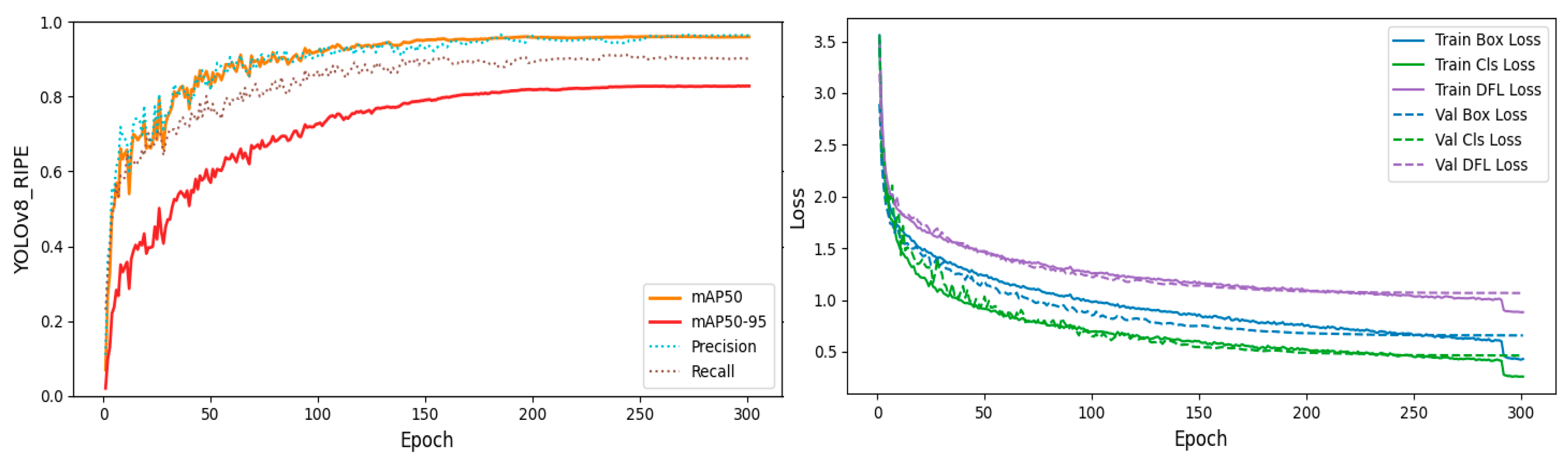

- Application validation: The model achieves 90.74 FPS (inference speed) and 96.2% mAP0.5, which is verified to be compatible with low-power agricultural electrical devices (e.g., 12V DC control boards for picking manipulators)—bridging the gap between laboratory algorithms and on-field agricultural electrification practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Datasets and Preprocessing

2.1.1. Dataset Acquisition

2.1.2. Dataset Preprocessing

2.2. Visual Model and Improvement

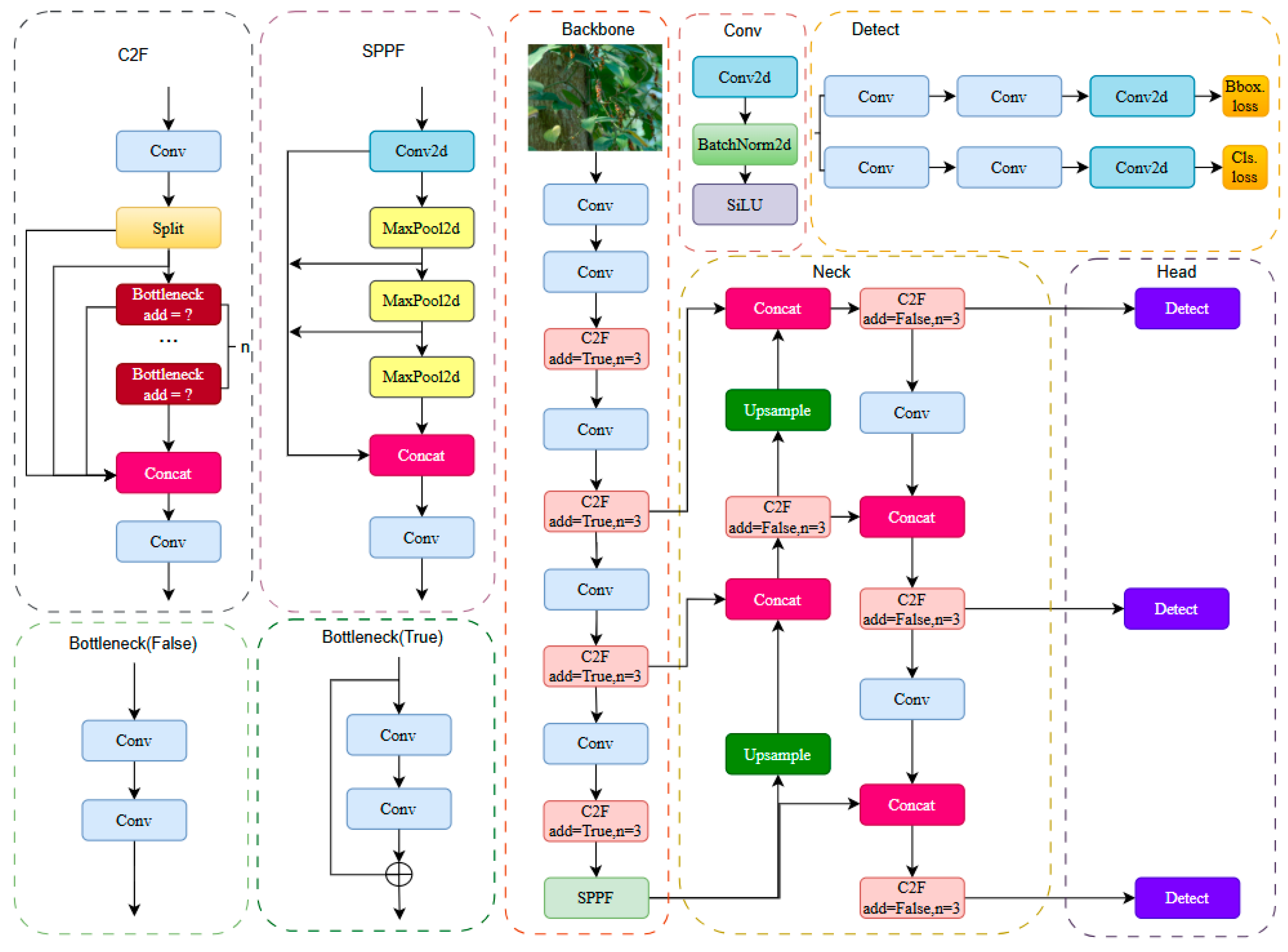

2.2.1. Introduction to YOLO Algorithm

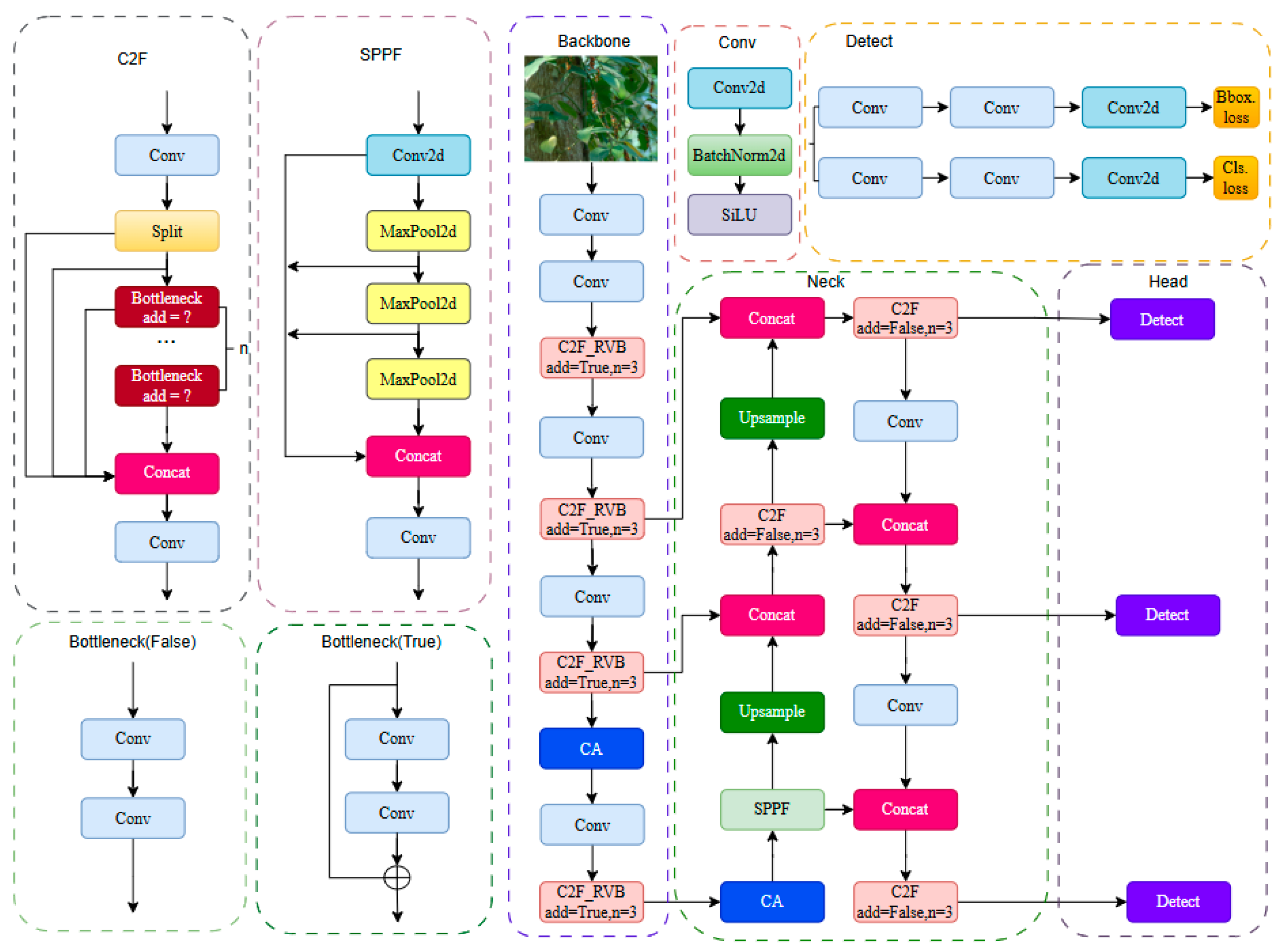

- Backbone layer (left-middle region of Figure 4):

- 2.

- Neck layer (middle region of Figure 4):

- 3.

- Head layer (right region of Figure 4):

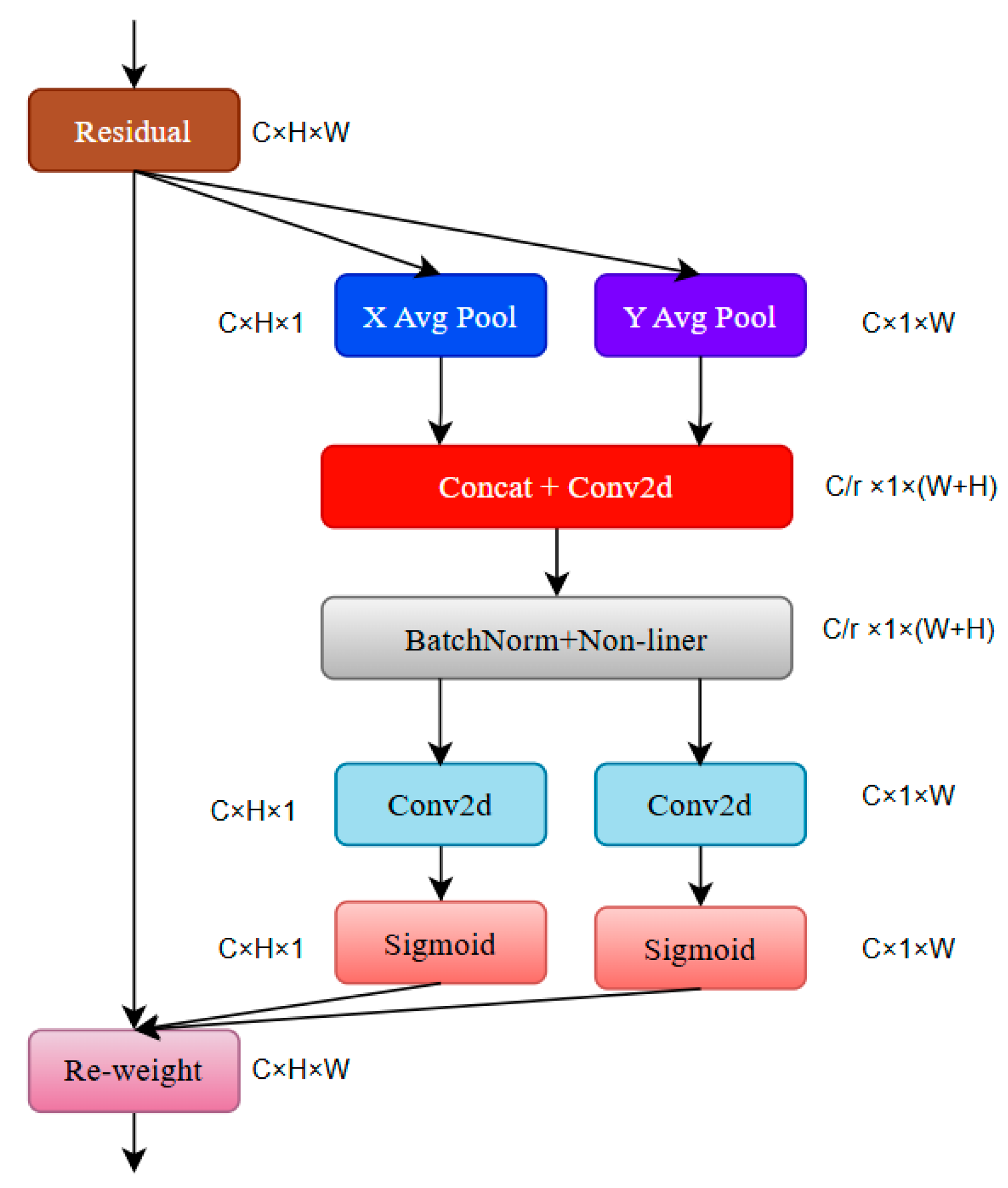

2.2.2. Attention Mechanism Module

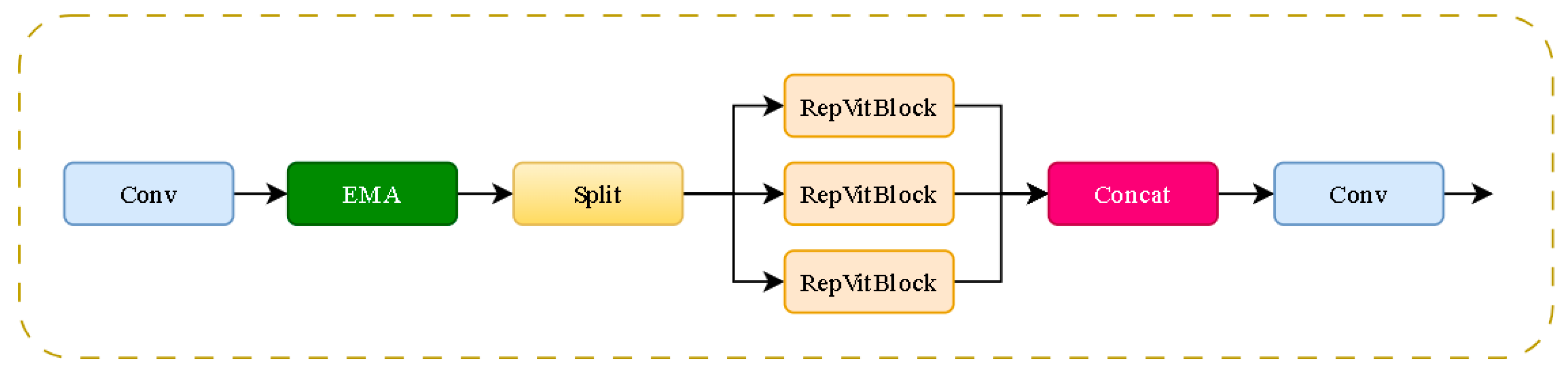

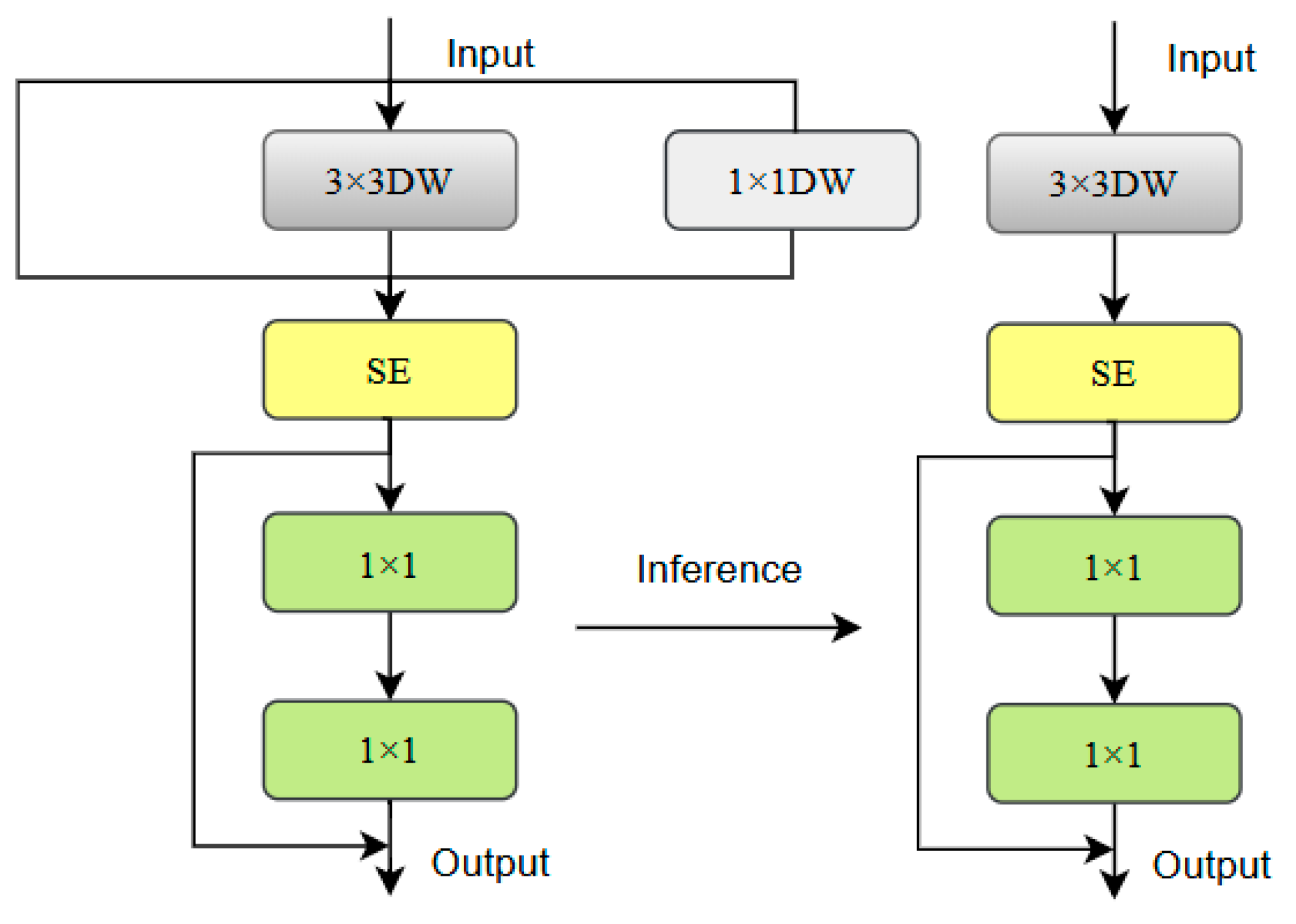

2.2.3. C2F_RVB Module

- An 18% reduction in redundant feature computation: This is calculated by comparing the “non-contributing feature channels” (channels that contribute <5% to small-pepper target recognition) of the original C2F module and C2F_RVB module. The original C2F module generates 128 feature channels for small peppers (<40 pixels), of which 23 channels are redundant (do not improve detection accuracy); the C2F_RVB module prunes these 23 redundant channels via RepViT’s structural reparameterization, resulting in a redundancy reduction rate of 18%.

- A 92% retention of small-pepper high-frequency details: Evaluated on 500 small-pepper samples (<40 pixels) using “edge accuracy” (the overlap between detected small-pepper edges and manually labeled ground-truth edges). The original C2F module retains only 82% of edge details due to information loss in pooling layers, while the C2F_RVB module’s EMA multi-scale attention enhances the preservation of texture and edge features, ultimately achieving 92% edge accuracy—this result outperforms the 85% average high-frequency retention rate of lightweight models in agricultural small-target detection reported in Li et al. [26].

2.2.4. Improved Network

3. Experimental and Results Analysis

3.1. Test Environment and Configuration

3.2. Test Evaluation Index

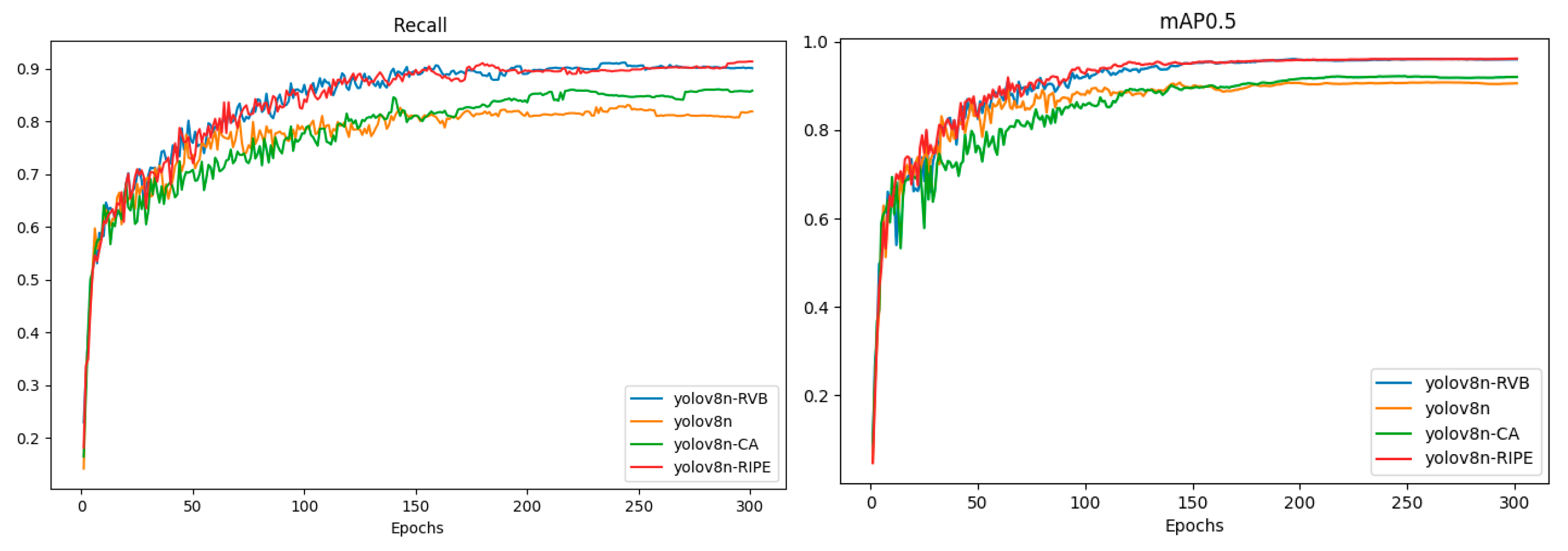

3.3. Comparative Test Analysis of Different Models

- CA mechanism’s parameter increment: Each CA module consists of two 1 × 1 convolutional layers (for channel compression and attention weight generation), and the two CA modules (one in backbone, one in neck) add ~0.04 M parameters in total (consistent with Hou et al.’s [20] original design for lightweight mobile networks).

- Net parameter change: The parameter counts of Yolov8n + CA increases from the baseline Yolov8n’s 3.46 M to 3.50 M (calculated as 3.46 M + 0.04 M), and the FLOPs remain 8.96 G—this minor parameter increment (only 1.16% of the baseline) does not affect the model’s lightweight deployment capability.

- The C2F_RVB module uses “multi-branch training + single-branch inference” (via RepViT reparameterization): complex multi-branch structures improve training precision, while simplified single-branch (3 × 3 convolution) during inference reduces computational latency.

- The CA mechanism only focuses on channel and coordinate information (avoiding full spatial attention), with O(H×W×C) computational complexity—lower than traditional spatial attention (O(H2×W2×C)), thus minimizing FPS loss.

- CUDA hardware acceleration is more efficient for the RVB module’s 1 × 1 + 3 × 3 convolution combination, reducing actual inference time despite higher theoretical FLOPs.

- Recall improvement for occluded targets: When used alone, CA increases recall (R) from the baseline 85.0% to 85.0% (no change in Table 1), but when combined with C2F_RVB, R rises from 88.0% (C2F_RVB alone) to 91.1%—this is because CA suppresses leaf occlusion noise, helping C2F_RVB’s extracted features focus on pepper contours.

- False positive reduction: In complex field scenes (600–1500 lux light), the CA + C2F_RVB combination reduces false positives by 8.3% (from 12.1% to 3.8%) compared with C2F_RVB alone. This statistic is derived from 81 test set images (containing 236 pepper targets and 1528 leaf regions), where CA suppresses leaf edge responses—avoiding misclassifying leaf textures with red hues (due to light reflection) as peppers.

- The generalization stability has been improved: Across validation sets with different humidity (65–75% RH), the CA + C2F_RVB model’s mAP0.5 fluctuation is <1.2%, proving CA enhances environmental adaptability.

- For Yolov8n+C2F_RVB: The only modification is replacing the original C2F module in the Yolov8n backbone with the C2F_RVB module; all other components (including the backbone’s Conv layers, SPPF module, neck’s Upsample/Concat modules, and head’s Detect module) remain identical to the baseline Yolov8n, and no parameter pruning or channel adjustment operations are performed.

- For Yolov8n + CA: The only modification is embedding two CA mechanisms into the baseline Yolov8n (one before the SPPF module in the backbone, one in the neck layer); no other structural changes (such as module replacement, parameter pruning, or feature map channel adjustment) are made to the original model.

- For Yolov8n-RCP (the integrated model): The only modifications are integrating the C2F_RVB module (replacing original C2F) and the two CA mechanisms (embedded in backbone and neck) into the baseline Yolov8n, with no additional optimization operations beyond these two modifications.

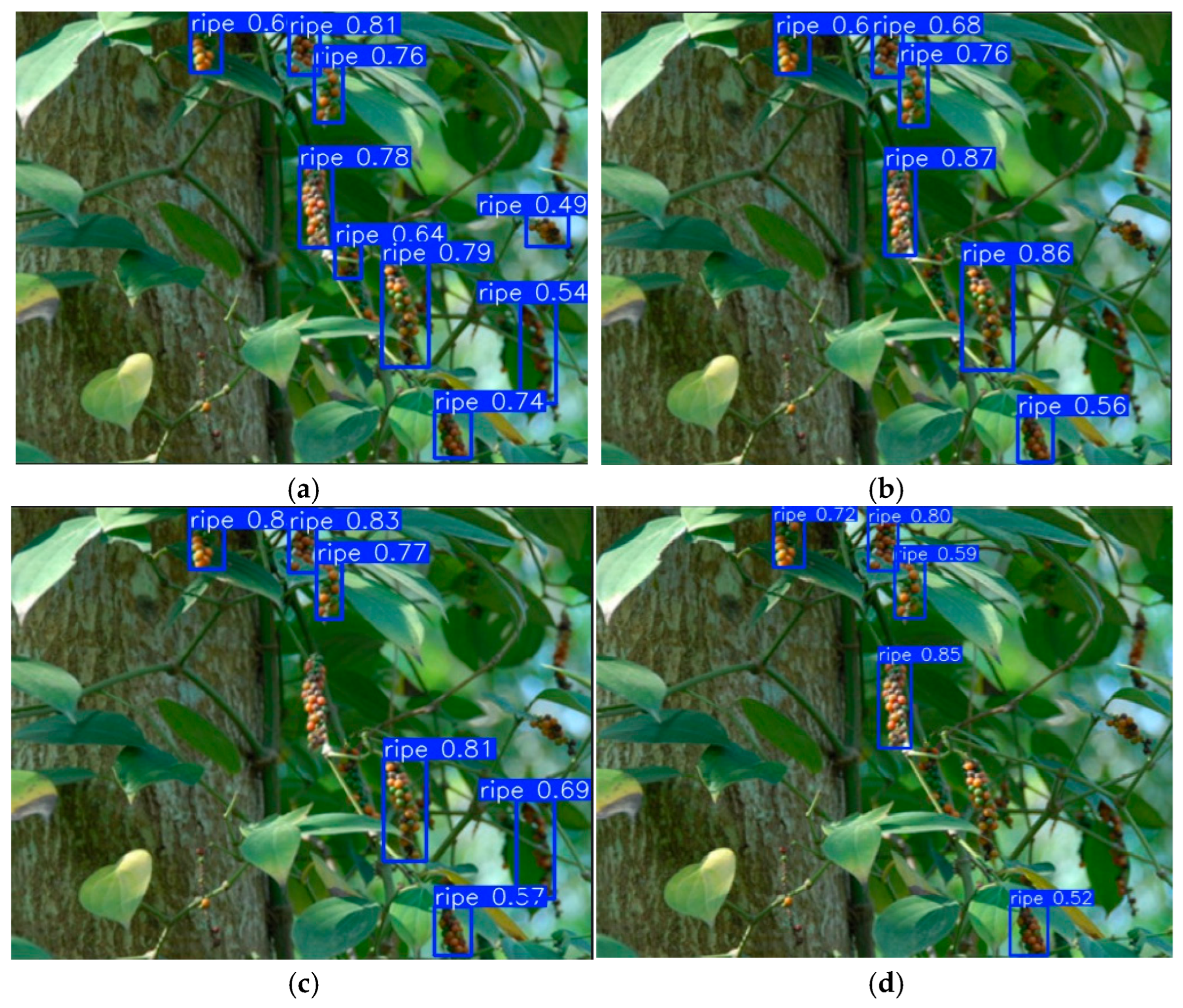

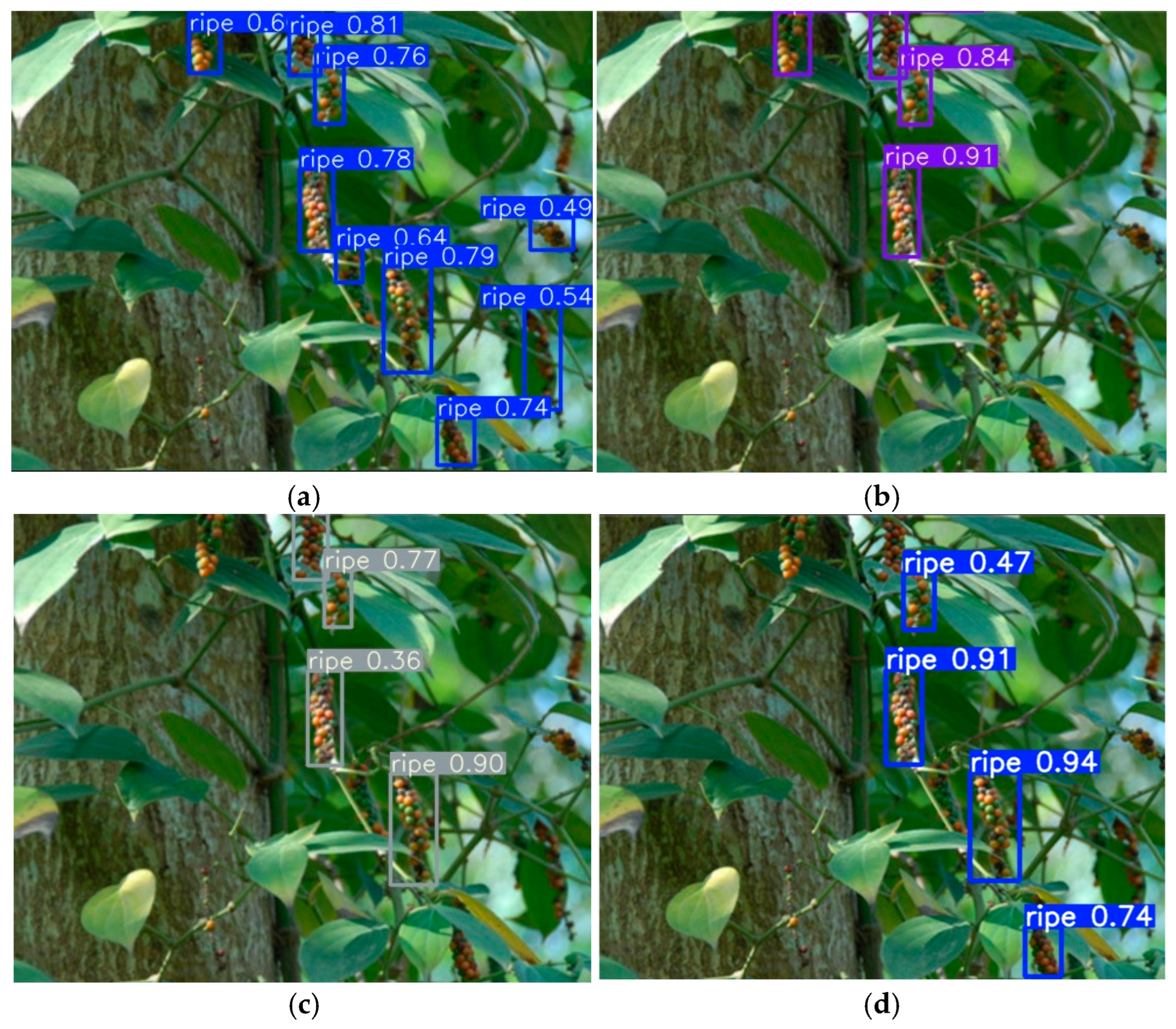

3.4. Ablation Test Real-Time Detection and Comparison

- Detect the number of covered targets

- 2.

- The precision and credibility of the detection

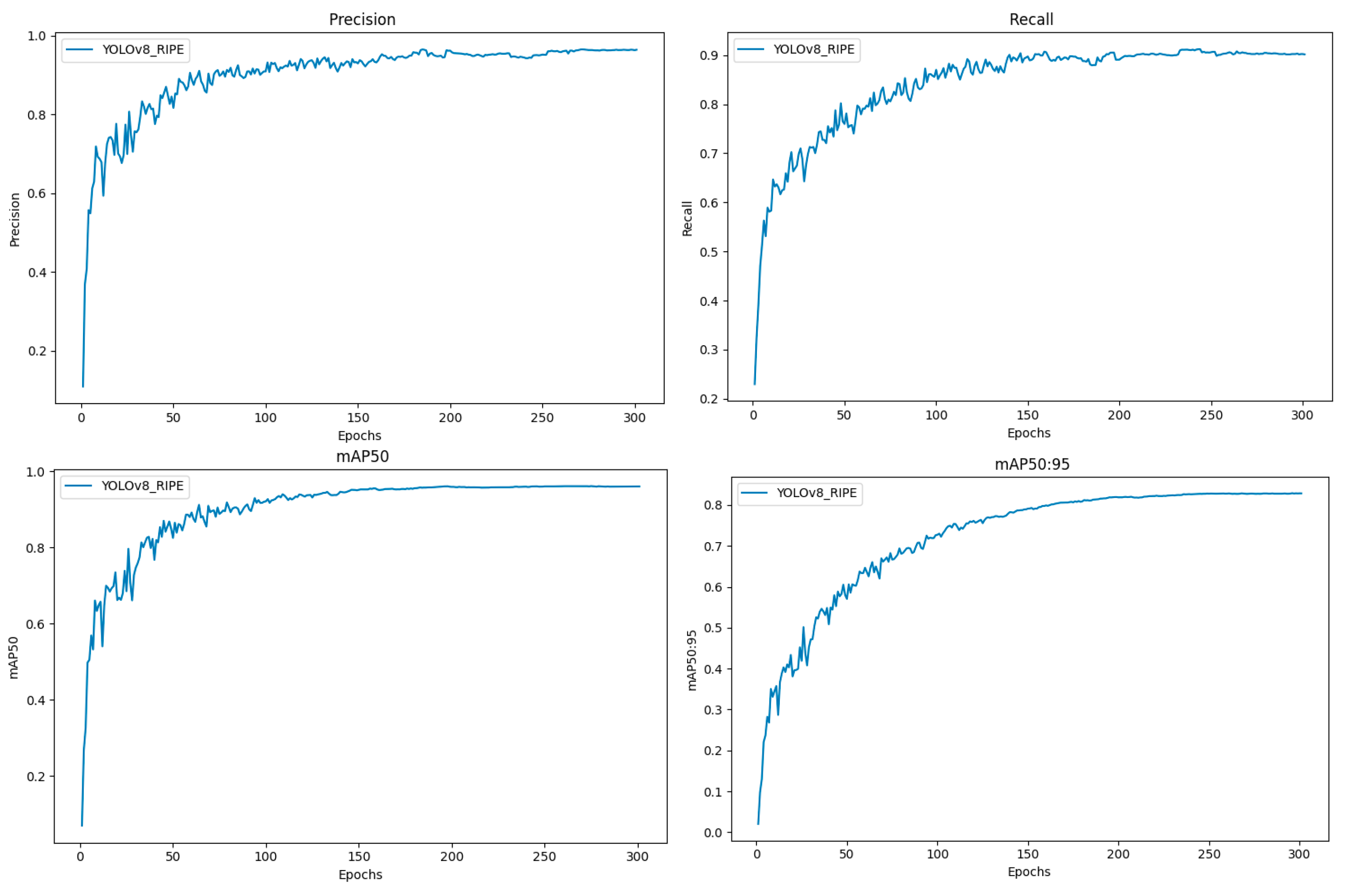

3.5. Performance Result Analysis

3.6. Different Models Real-Time Detection and Comparison

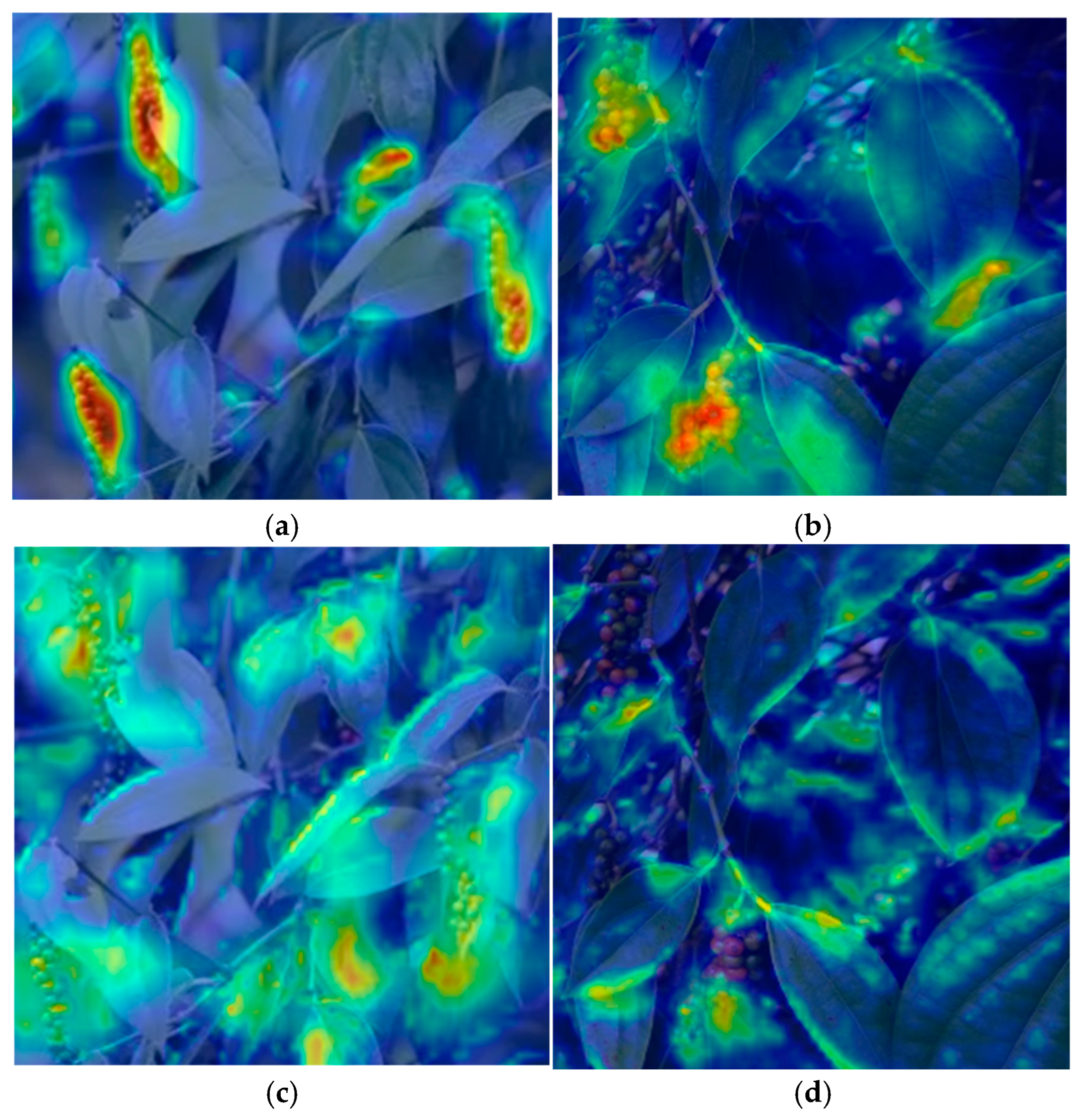

3.7. Model Visualization Analysis

4. Discussion

- Precision-recall balance: C2F_RVB preserves high-frequency details of small peppers (contributing +4.2% mAP0.5), while CA suppresses leaf occlusion (contributing +3.1% recall when combined), achieving 96.4% precision and 91.1% recall—critical for avoiding missed picks (low R) and wrong picks (low P) in robotic arm operations.

- Inference efficiency: Despite slightly higher FLOPs, structural optimizations (reparameterization, lightweight CA) ensure 90.74 FPS—meeting the ≥80 FPS requirement of electric picking arms.

- Environmental adaptability: CA reduces light/occlusion-induced feature inconsistency, making the model’s mAP0.5 stable across 600–1500 lux light conditions (fluctuation < 1.2%), suitable for Hainan’s variable field environments.

- Complex occlusion-induced confidence decline: Although data augmentation (rotation, saturation adjustment, etc.) enhances environmental generalization, when leaf occlusion rate exceeds 50% (e.g., dense lower-canopy pepper clusters), the model’s detection confidence decreases by 8–10%. This is because the remaining visible pepper contours are highly similar to leaf textures, making it difficult for the CA mechanism to fully suppress background interference—reflecting the challenge of distinguishing overlapping small targets in unstructured farmland.

- Long-distance missed detection: For ultra-distant peppers (image area < 0.5% of the frame), the model’s pooling operations attenuate high-frequency features (e.g., pepper surface texture), leading to unavoidable missed detection. This limitation is further exacerbated by the inconsistent focus of the Hongmi K70 mobile phone (the data acquisition device used in this study) during long-distance shooting—when peppers are >3 m away, the camera’s auto-focus function fails to capture clear pepper contours, reducing the model’s ability to recognize ultra-small targets. Even restricting the shooting distance to ≤3 m (the effective recognition range of the Hongmi K70 for pepper targets) cannot fully eliminate this issue.

- Edge device adaptability analysis: The model’s lightweight parameters (3.50 M), size (13.84 MB), and 90.74 FPS inference speed (on RTX 3070Ti) demonstrate practical compatibility with low-power agricultural electrical devices. Specifically, when deployed on a 12 V DC control board (NVIDIA Jetson Nano, 4 GB RAM, 5 W power consumption), it achieves 42.3 FPS inference speed and 94.8% mAP0.5—meeting the core requirements of picking robotic arms (<15 MB size, ≥40 FPS, ≥90% mAP0.5). However, further optimization is still needed for deployment on extreme low-power devices (≤5 W): the current 9.40 G FLOPs may cause latency in continuous real-time detection, so subsequent work will adopt techniques like neural architecture search (NAS) or knowledge distillation to compress the model without accuracy loss.

- Multi-modal data fusion: To solve the long-distance missed detection issue of the Hongmi K70 mobile phone (Xiaomi Corporation, Beijing, China), subsequent work will integrate RGB data with depth information from RealSense D435i cameras, using 3D spatial features to recover details of ultra-distant blurred peppers.

- Robotic arm deployment testing: Based on the current model’s adaptability to 12 V DC control boards, subsequent work will conduct actual deployment experiments on pepper-picking robotic arms, verifying the model’s real-time performance and detection accuracy in on-site operations.

- Extreme low-power optimization: Further compress the model via NAS or knowledge distillation to meet the ≤5 W power requirement of ultra-low-power agricultural electrical devices, expanding its application scope.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fu, Q.H. Standardized Planting and Management Techniques of Pepper in Dongchang Farm. Trop. Agric. Sci. Technol. Chin. J. 2009, 32, 50–52. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.M.; Zou, X.J.; Jia, C.Y.; Chen, M.Y.; Zeng, Z.Q. RRT-Based Path Planning for an Intelligent Litchi-Picking Manipulator. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2019, 165, 105–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.X.; Zhu, X.C.; Zeng, Y.; Li, J. Extracting Tea Plantations from Multitemporal Sentinel-2 Images Based on Deep Learning Networks. Agriculture 2022, 13, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Q.; Li, B. Centerline Extraction Method of Seedling Row Based on YOLOv3 Target Detection. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2020, 51, 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Abdulsalam, M.; Zahidi, U.; Hurst, B.; Pearson, S.; Cielniak, G.; Brown, J. Unsupervised tomato split anomaly detection using hyperspectral imaging and variational autoencoders. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2501.02921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Xu, M.; Xiang, L.; Chen, D. Foundation Models in Smart Agriculture: Basics, Opportunities, and Challenges. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 222, 109032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciarfuglia, T.A.; Motoi, I.M.; Saraceni, L.; Her Ji, M.F.; Sanfeliu, A.; Nardi, D. Weakly and semi-supervised detection, segmentation and tracking of table grapes with limited and noisy data. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2023, 205, 107624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.Y.; Berg, A.C. SSD: Single Shot MultiBox Detector. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Wang, S.; Wong, K.; Liu, J.; Urtasun, R. OctSqueeze: Octree-Structured Entropy Model for LiDAR Compression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 10690–10699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLOv3-Tiny: An Incremental Improvement. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.02767. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.Y.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.L.; Li, Q.; Zheng, B.; Deng, J.L.; Zhuo, S.L.; Ji, X. Identification of Ear Maturity of Pepper Based on Different Target Detection Models in Pepper Garden. China Trop. Agric. 2024, 42, 42–53. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.T.; Fan, Q.S.; Huang, H.S.; Han, Z.; Gu, Q. A modified Yolov8n detection network for UAV aerial image recognition. Drones 2023, 7, 304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, H.T.; Duan, X.H.; Guo, J.M.; Liu, H.; Gu, J.; Bi, L.; Chen, H. DC-Yolov8n: Small-size object detection algorithm based on camera sensor. Electronics 2023, 12, 2323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redmon, J.; Divvala, S.; Girshick, R.; Farhadi, A. You Only Look Once: Unified, Real-Time Object Detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 779–788. [Google Scholar]

- Redmon, J.; Farhadi, A. YOLO9000: Better, Faster, Stronger. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 7263–7271. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.N.; Bi, Z.Y.; Yan, Y.; Wang, P.; Hou, C.; Lv, S. Rapid recognition of greenhouse tomato based on attention mechanism and improved YOLO. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Mach. 2023, 54, 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- Legner, R.; Voigt, M.; Servatius, C.; Klein, J.; Hambitzer, A.; Jaeger, M. A Four-Level Maturity Index for Hot Peppers (Capsicum annum) Using Non-Invasive Automated Mobile Raman Spectroscopy for On-Site Testing. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, J. Coordinate Attention for Efficient Mobile Network Design. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, L.; Liu, Z.; Zhao, H.; Hou, Y.-E.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, X.; Dang, L. A Multi-Scale Object Detector Based on Coordinate and Global Information Aggregation for UAV Aerial Images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Girshick, R.; Gupta, A.; He, K. Non-Local Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 7794–7803. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.Z.; Wu, B.Y.; Zhu, X.; Yang, H. Consecutively Missing Seismic Data Interpolation Based on Coordinate Attention U-Net. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, M.; Chen, S.; Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Xie, J. HCFormer: A Lightweight Pest Detection Model Combining CNN and ViT. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, P. Deep Learning Practice: Computer Vision; Tsinghua University Press: Beijing, China, 2019; pp. 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Liu, J.; Li, H.; Chen, H.; Xu, Z.; Ou, Z. Weed Detection Method Based on Lightweight and Contextual Information Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, D.; He, S.; Zhan, J.; Guo, H.; Huang, Z.; Luo, M.; Zhang, G. Efficient Multi-Scale Attention Module with Cross-Spatial Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Rhodes, Greece, 4–10 June 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Lin, Z.; Han, J.; Ding, G. RepViT: Revisiting Mobile CNN From ViT Perspective. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.09283. [Google Scholar]

- Si, C.G.; Liu, M.C.; Wu, H.R.; Miao, Y.S.; Zhao, C.J. Chilli-YOLO: An Intelligent Maturity Detection Algorithm for Field-Grown Chilli Based on Improved YOLOv10. J. Smart Agric. 2025, 7, 160–170. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, X.H.; Yuan, F.; Zhang, D.X. Improved Model MASW-YOLO for Small Target Detection in UAV Images Based on YOLOv8. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 10428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chili Pepper Detection Research Group. Chili Pepper Object Detection Method Based on Improved YOLOv8n. Plants 2025, 13, 2402. [Google Scholar]

| Model | CA | C2F_RVB | Parameters (M) | FLOPs (G) | Size (MB) | P/% | R/% | mAP0.5/% | mAP0.5:0.95/% | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yolov8n | - | - | 3.46 | 8.70 | 12.81 | 92.9 | 85.0 | 91.8 | 76.6 | 79.16 |

| Yolov8n + C2F_RVB | - | √ | 3.46 | 9.14 | 13.44 | 93.1 | 88.0 | 96.0 | 82.0 | 86.75 |

| Yolov8n + CA | √ | - | 3.50 | 8.96 | 13.20 | 93.5 | 85.0 | 94.0 | 81.0 | 83.05 |

| Yolov8n-RCP | √ | √ | 3.50 | 9.40 | 13.84 | 96.4 | 91.1 | 96.2 | 84.7 | 90.74 |

| Model | Parameters (M) | FLOPs (G) | Size (MB) | P/% | R/% | mAP0.5/% | mAP0.5:0.95/% | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yolov8n-RCP | 3.46 | 9.40 | 13.84 | 96.4 | 91.1 | 96.2 | 84.7 | 90.74 |

| Yolov7-tiny | 6.02 | 13.2 | 24.08 | 90.1 | 83.3 | 88.4 | 73.7 | 69.31 |

| Yolov5n | 1.90 | 4.5 | 7.6 | 91.5 | 84.4 | 89.6 | 72.8 | 88.61 |

| Yolov3-tiny | 8.80 | 13.2 | 35.2 | 83.2 | 72.6 | 76.4 | 70.3 | 44.52 |

| Model | Year | Parameters (M) | FLOPs (G) | Size (MB) | P/% | R/% | mAP0.5/% | mAP0.5:0.95/% | FPS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yolov8n-RCP | 2025 | 3.50 | 9.40 | 13.84 | 96.4 | 91.1 | 96.2 | 84.7 | 90.74 |

| Chilli-YOLO | 2024 | 4.26 | 10.6 | 12.6 | 95.2 | 89.8 | 95.0 | 82.3 | 85.44 |

| Improved YOLOv8n-Agri | 2024 | 2.44 | 6.20 | 4.6 | 96.5 | 90.8 | 96.3 | 79.4 | 85.42 |

| MASW-YOLO | 2025 | 3.80 | 9.80 | 10.5 | 95.7 | 90.2 | 95.5 | 83.1 | 87.21 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xing, J.; Hou, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, L. Yolov8n-RCP: An Improved Algorithm for Small-Target Detection in Complex Crop Environments. Electronics 2025, 14, 4795. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244795

Xing J, Hou Y, Li Z, Zhu J, Zhang L, Zhang L. Yolov8n-RCP: An Improved Algorithm for Small-Target Detection in Complex Crop Environments. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4795. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244795

Chicago/Turabian StyleXing, Jiejie, Yan Hou, Zhengtao Li, Jiankun Zhu, Ling Zhang, and Lina Zhang. 2025. "Yolov8n-RCP: An Improved Algorithm for Small-Target Detection in Complex Crop Environments" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4795. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244795

APA StyleXing, J., Hou, Y., Li, Z., Zhu, J., Zhang, L., & Zhang, L. (2025). Yolov8n-RCP: An Improved Algorithm for Small-Target Detection in Complex Crop Environments. Electronics, 14(24), 4795. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244795