1. Introduction

In recent years, there has been growing interest in utilizing the purchase, repair and consultation behaviors of customers to predict future buying behavior or to cluster similar customers into coherent groups [

1,

2]. The aim of this paper is effectively embedding sequential behaviors from customers into latent spaces (i.e., embedding spaces) that reflect the meaningful findings of customer behaviors with products or services [

3]. Effort has been focused on their representation models, particularly their training methodologies, since these approaches ultimately determine the quality and applicability of the resulting latent vectors [

4]. Today, contrastive learning has emerged as a key technique, improving domain matching across customer segments and enhancing both embedding reliability and predictive performance [

5].

Despite the growing advancements in representation models, it remains uncertain which approach yields better latent vector representations for our customer data [

6]. To address this, we designed experiments using deep learning models based on LLMs, utilizing their capabilities to represent customer behaviors as latent spaces tailored to our data [

7]. This approach unfolds in three main steps. In step (1), we convert various customer behaviors—encompassing purchases, repairs, and consultations—into a sequence text for each customer, ensuring that the model can better understand and capture the contextual nuances of each action. In step (2), we train the LLM-based representation model on these behaviors, allowing it to learn features that effectively encapsulate the diverse aspects of customer behaviors. In step (3), by using latent vectors extracted from step (2), classifiers are trained to predict whether a customer will purchase a particular product. The results of step (3) demonstrate how the learned representation models can enhance real-world predictive performance.

Our objective is to determine the effective strategy for embedding customers’ sequential behaviors into latent spaces, focusing on their ability to capture meaningful patterns and enhance predictive performance in real-world scenarios. With this focus, we keep steps (1) and (3) fixed and place our primary emphasis on step (2). We compare two different strategies for making the representation model on customer data, who consented to its use for research purposes. The first strategy (2-1) trains a model BERT4Rec from scratch [

8]. The second strategy (2-2) employs a pre-trained model, ELECTRA, that is fine-tuned by our data [

9]. For whole steps, we use a dataset containing purchase, repair, and consultation records from 14 million customers. Both models are trained on this data and evaluated based on their ability to predict the next home product each customer is likely to purchase.

To compare the (2-1) and (2-2) approaches based on their performance, eight binary classifiers, using a Random Forest, are trained by using their latent vector to predict purchase outcomes for eight different products. We observe that the fine-tuned ELECTRA approach (2-2) achieves a slight gap against the BERT4Rec trained from scratch (2-1). The fine-tuned ELECTRA achieves an average AUC of 0.613—outperforming BERT4Rec by 0.012. BERT4Rec’s F1-score is 0.025, which is 0.007 lower than that of the fine-tuned ELECTRA. On the other hand, in terms of the top 10% lift value (an important performance, relevant to targeting customers for advertising), fine-tuned ELECTRA exceeds BERT4Rec by 0.27. Given that the purchase rate in this dataset is only about 0.5% of all customers, even a modest improvement in the top 10% predicted segments can translate into a substantial advantage. Consequently, this study concludes that the fine-tuned ELECTRA model is better suited for practical deployment in corporate settings, where the focus is on embedding customers.

Ideally, the quality of customer’s latent vectors from representation models should be verified rather than relying solely on classifier comparisons [

10,

11]. To achieve this, we show 2-dimensional projections using PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP and attention variations using AttentionViz to uncover meaningful patterns [

12,

13,

14]. Unfortunately, although we do not observe any interpretable clusters in 2-dimensional projections, this is likely due to the high-dimensional semantics of LLMs and challenges such as dimensional interference [

15,

16]. We also employ AttentionViz to compare the attention mechanisms in the original ELECTRA and fine-tuned ELECTRA by our data [

17]. Finally, to compare the performance of unidirectional and bidirectional models, we conduct an experiment with fine-tuning ELECTRA and LLaMA2 [

18], finding similar performance but highlighting ELECTRA’s efficiency due to its smaller dimensionality (256 vs. 1048).

Despite the increasing use of LLMs for customer behavior modeling, it remains unclear whether domain-specific training or fine-tuning is more effective for large-scale industrial data. The gap is particularly evident for sequential behaviors that are text-like but domain-constrained. To address this, we compare BERT4Rec and ELECTRA under identical preprocessing and classification pipelines.

The main contributions in this paper are three-fold:

Three-step framework for evaluating the representation methods to represent meaning into latent space.

Empirical evaluation of training the recommendation model from scratch vs. fine-tuning the pre-trained LLM.

Follow-Up questions and explorations: Examination of attention-based analysis and demonstration of efficiency in fine-tuned LLaMA2 vs. fine-tuned ELECTRA.

Unlike studies that introduce new model architectures, our contribution lies in the empirical comparison of two training methods: training BERT4Rec from scratch versus fine-tuning a pre-trained ELECTRA model. Our goal is to provide practical evidence on which representation-learning strategy better fits large-scale industrial customer behavior data.

2. Background

The methodology for learning and representing customer behaviors in latent spaces has become a crucial technique in predictive modeling and recommendation systems [

19]. Conventional efforts frequently relied on autoencoders to map sequences of customer behaviors into compact, meaningful vector representations [

20]. These methods showed potential but often faced challenges in capturing the subtle context and dynamic relationships present in sequential data. The advent of transformer-based LLMs, especially those employing attention mechanisms and multi-head transformer learning, has improved the ability to embed complex relationships into latent spaces, but also makes it confusing to interpret the meaningful relations among these latent vectors [

21,

22].

Recent studies in sequential recommendation have expanded this direction by using transformer architectures for modeling user behavior. BERT4Rec demonstrated that bidirectional self-attention with a cloze-style objective can effectively capture contextual patterns in sequential interactions [

8]. At the same time, the use of pre-trained LLM representations has shown promise in enhancing the semantic relevance of customer embeddings, even when the underlying behavior sequences are domain-specific [

23]. In addition, contrastive learning has emerged as an effective self-supervised approach for improving robustness in behavior representation, with graph-based alignment [

24], debiased contrastive training [

25], and LLM-oriented contrastive alignment such as CALRec [

26]. These trends highlight the increasing role of pre-training and self-supervision in customer representation learning. While contrastive learning has become a promising direction for representation modeling, it is not implemented in the present study. Instead, we consider it a future extension of our framework, particularly for disentangling customer behavioral patterns.

Among these LLM-based methodologies, models like BERT4Rec and ELECTRA have gained popularity due to their adaptability and robust performance in domain-specific tasks. BERT4Rec, originally designed for recommendation systems, applies a masked language modeling approach to sequential customer data, leveraging sequence context to predict masked next sequences [

8]. ELECTRA, meanwhile, is developed for a general language model but has proven effective in fine-tuning scenarios because of its lightweight architecture and efficient domain adaptation [

9]. Both models capitalize on attention mechanisms to capture meaningful patterns from large volumes of data, yet their application to industrial-scale customer behavior modeling remains underexplored.

Transformer-based approaches such as SASRec have shown that self-attention can model sequential dependencies without relying on recurrent networks [

27]. Self-supervised strategies such as sequential contrastive learning have further improved representation quality through temporal or structural augmentations [

24,

25]. Meanwhile, advancements in LLM pre-training, such as ELECTRA discriminator objectives [

28], meta controller based pre-training [

29], and self augmentation strategies [

30], demonstrate that pre-training choices significantly influence downstream performance. These developments strengthen the need to compare domain-specific models trained from scratch with fine-tuned LLMs in industrial-scale customer representation learning.

Beyond representation learning for recommendation, large language models have also been applied in customer-facing and marketing scenarios. Recent work has examined LLM-generated service messages in service recovery and customer support settings and reported that evaluation in realistic, domain-specific environments is important for assessing model usefulness [

31,

32]. Other studies have proposed emotion-aware embedding fusion to improve response quality by combining semantic and affective cues [

33]. LLMs have also been used to simulate multi-turn online customer behavior and to support consumer segmentation and marketing decision-making based on real behavioral data [

34,

35]. These studies suggest that LLMs are increasingly adopted as tools for modeling and interacting with customers, which further motivates our empirical comparison of training strategies on large-scale industrial customer data.

Our study evaluates the effectiveness of training a domain-specific model (BERT4Rec) from scratch versus fine-tuning a pre-trained LLM (ELECTRA) on a large dataset from customers. In particular, we compare BERT4Rec’s sequence-based training, which is popular in recommendation contexts, with ELECTRA’s fine-tuning approach, prized for its efficiency and adaptability in real-world environments.

3. Method

In this study, we implement a 3-step pipeline to ensure clarity and adaptability: step (1) transforms raw customer data—including purchase, repair, and consultation behaviors—into natural language descriptions; step (2) uses these text-based behavioral sequences to train or fine-tune our chosen representation models; and step (3) evaluates the quality of the learned-only embedded vectors from representation models. The following subsections delve into each step in detail, explaining how we define behaviors in natural language, how we train and fine-tune the models, and how we measure the resulting performance. An overview of this workflow is provided in

Figure 1. In this figure, step (1) corresponds to stages 1 to 3, step (2) aligns with stage 4, and step (3) is represented in stage 5. Details of these 5 stages and 3 steps are treated in the subsection below.

3.1. Step (1): Defining Customer Behavior Data

The process of transforming customer behaviors into natural language is illustrated in

Figure 1 (stage 1, 2, and 3). As shown in

Figure 1, this study defines 8 main customer behaviors: no action, receiving, repairing, buying, renting, using, consulting, and visiting. For each of these 8 main behaviors, we identify which products or situations are involved. We ultimately define 309 distinct actions from whole customer behaviors. In BERT4Rec, these 309 actions map directly to tokens. By contrast, ELECTRA utilizes a pre-defined tokenizer and does not rely on this custom set of 309 tokens since ELECTRA should be fine-tuned in this study. When customers have no recorded action within a one-month window, their behavior is categorized as “No Action”. This structured definition of customer behavior ensures that our model input data captures both the variety and the temporal nature of each user’s activity, setting the stage for the subsequent training process.

After defining the 309 distinct actions, we assign them to each customer to create a comprehensive sequence dataset. As shown in stage 2 from

Figure 1, we aggregate all relevant events for each individual from their earliest recorded activity through January 2023. We then organize these actions in chronological order, forming continuous timelines akin to stage 3, according to behavioral sequence. Given that LLMs can process code-like syntax, we follow an approach similar to the one described in the paper [

23], separating each user’s data block with a newline character

\n and using an arrow

-> to represent each successive action within that block, from oldest to newest. This process yields a total of 1.1 billion actions across approximately 14 million customers, establishing a rich foundation for the subsequent representation learning tasks.

3.2. Step (2): Training/Fine-Tuning Representation Models

After the defined sequence data described in step (1), the next stage of our research involves training or fine-tuning representation models to embed these sequences into latent vectors. The primary goal is to capture both the chronological progression and contextual relationships within each customer’s behavior, assuming that the vectors could reflect nuanced behaviors such as purchase timing, repair patterns, or consultation tendencies. To achieve this, we explore two distinct strategies. One is rooted in constructing a domain-specific vocabulary from scratch, and the other relies on fine-tuning a pre-trained language model. The training duration of the two strategic models below utilizes data up to January 2023.

3.2.1. Training BERT4Rec from Scratch

Our first approach employs BERT4Rec, a bidirectional transformer model originally designed for recommendation systems [

8]. BERT4Rec adopts a masked language modeling objective tailored to sequential recommendation contexts. It predicts masked next actions within a user’s activity sequence, effectively capturing the bidirectional dependencies present in real-world data.

Since step (1) established 309 distinct tokens representing customer behaviors, these tokens form the customized vocabulary for BERT4Rec. This allows BERT4Rec to learn robust contextual embeddings that are specific to customer behaviors in our domain. By training from scratch on domain-specific tokens, BERT4Rec aims to develop highly specialized representations that might be more sensitive to the complexity of customer data.

3.2.2. Fine-Tuning Pre-Trained ELECTRA

In contrast to the training of BERT4Rec from scratch, our second strategy centers on fine-tuning a pre-trained ELECTRA [

9]. Unlike the way that each behavior is represented by a unique token in BERT4Rec, we use a pre-trained tokenizer and vocabulary for finetuning ELECTRA. Fine-tuned ELECTRA also involves formulating a masked learning task.

Since ELECTRA is originally trained on large-scale text, we hypothesize that its pre-trained knowledge provides an advantage, requiring only minimal domain-specific updates by fine-tuning it. Therefore, we performed a single epoch of fine-tuning on our entire dataset. However, one potential drawback is the absence of any task to represent the next customer behaviors. This limitation could lead to latent vectors that are slightly less tailored to domain-specific actions.

3.2.3. Training Parameter Comparison

Table 1 summarizes the key model and training parameters used for both BERT4Rec and fine-tuned ELECTRA. The two models differ substantially in architecture and pre-training strategy. ELECTRA uses a deeper transformer encoder with a larger hidden dimension (256 vs. 64) and more attention heads, reflecting its origin as a general-purpose language model. In contrast, BERT4Rec is trained from scratch with a lighter configuration, which is consistent with typical sequential recommendation settings.

For training, ELECTRA is initialized from the publicly available google/electra-small-generator checkpoint and fine-tuned for a single epoch with a small learning rate 5 × as pre-trained models generally require only modest updates to adapt to domain-specific behavior sequences. BERT4Rec is trained from scratch without pre-training, using a larger batch size and higher learning rate, and requires substantially more epochs (200) to converge due to the absence of prior knowledge. Both models employ the same masking probability (0.15), ensuring comparable masking-based training signals.

To ensure a fair comparison and isolate the effect of the two training paradigms, most hyperparameter choices follow the configurations suggested in the original BERT4Rec and ELECTRA papers. Adhering to these standard settings minimizes the influence of implementation-specific variations and allows the evaluation to focus on the fundamental differences between training from scratch and fine-tuning a pre-trained LLM.

These parameter settings highlight the fundamental differences between the two training paradigms: ELECTRA relies on efficient domain adaptation from a pre-trained model, while BERT4Rec must learn all sequential patterns from scratch. Providing these details enhances the reproducibility of our experiments and clarifies the contrast between the two approaches, addressing a reviewer’s request for a more transparent experimental setup.

In this study, we do not perform a systematic hyperparameter search for either model. Instead, we keep both BERT4Rec and ELECTRA close to the commonly used settings in the original papers. Our goal is to compare the training paradigms (training from scratch vs. fine-tuning a pre-trained model) rather than to optimize each model with heavy tuning. Therefore, the reported results should be interpreted under these standard configurations.

3.3. Step (3): Training Prediction Classifiers

We evaluate the prediction results of the two strategic models, BERT4Rec and fine-tuned ELECTRA, using 8 Random Forest classifiers. In this step (3), each Random Forest is trained on data from January to March 2023 and used to predict data from April to July 2023. During training, we split negative and positive labels evenly. For testing, data is randomly sampled from the actual dataset, and the results are considered to reflect the real-world distribution. The details of the data used for training and testing can be found in

Table 2 and is described in detail in

Section 4.

We use standard metrics such as the AUC and the F1-score to quantify overall predictive performance. In addition, we measure the top 10% lift, a business-critical metric that highlights how effectively the model identifies those customers who are most likely to make a high-value purchase—a particularly relevant consideration for targeted marketing campaigns. Comparing these metrics across BERT4Rec and ELECTRA reveals the strengths and weaknesses of each approach, especially in terms of fine-grained domain adaptation versus efficiency and potential ease of deployment.

Beyond predictive performance, interpretability remains central to evaluating representation models in large-scale industrial contexts. Therefore, we perform additional analyses, including dimensionality reduction techniques such as PCA, t-SNE, and UMAP [

12,

13,

14], to visually inspect the learned embeddings. We also conduct attention-based examinations using tools like AttentionViz to observe how each model focuses on specific behavioral transitions [

17]. These explorations could provide insights into whether the embeddings capture meaningful structure or whether certain interactions are overlooked in the process of domain adaptation.

We establish a unified framework for embedding large behavior data into latent spaces by using models from 2 strategies, training models from scratch or through fine-tuning. The results of this process highlight the comparison of BERT4Rec and ELECTRA while also providing valuable insights into methodological considerations for future applications of language behavior models in industrial contexts.

4. Experiments

This section presents the experimental procedures undertaken to evaluate the proposed approaches (BERT4Rec and fine-tuned ELECTRA) using the large-scale customer behavior dataset described earlier. We outline the data splitting and pre-processing strategies, followed by implementation details for each model. We discuss the performance metrics used to compare these two training paradigms, along with an interpretability analysis that sheds light on the learned representations.

As described in the

Section 3, we utilize proprietary customer data, which includes approximately 1.1 billion recorded behaviors from 14 million customers covering various purchase, repair, and consultation events. All customer data used in this study was fully anonymized under strict internal governance procedures. Personally identifiable information was removed prior to analysis, and only data with consent was used for research purposes. According to institutional guidelines, ethical approval was not required for anonymized operational data. We added this clarification to explicitly address ethical and privacy considerations.

Each customer’s behaviors are arranged chronologically and divided into sequences in step (1). To assess the predictive capabilities of the models, the data is split three-fold: dataset for training/fine-tuning LLM, train sets for classifiers, and test sets for predictions. This temporal split strategy reflects a realistic application scenario in which future events must be predicted from customer behavior data. For step (2), the training/fine-tuning portion of the timeline, leading up to January 2023, is held out as the train and test set for measuring out-of-sample performance. In addition to the dataset with eight classifiers for step (3), the training data from February through April 2023 was employed, and we tested the classifier using data collected between May and July 2023. As shown in

Table 2, we train classifiers for each product and evaluate them using the entire customer dataset. Furthermore, the study examines four LG-branded products, including LG Objet (premium lines encompassing various appliances), LG CordZero A9 (vacuum cleaners), LG Gram (laptops), and LG Styler (steam closet clothing care systems). In addition, four other products are categorized as general appliances.

The original purchase rate (≈0.5%) is too sparse for stable classifier training in

Table 2, causing models to fail to converge under realistic imbalance. Therefore, we adopt a 50/50 balanced split for classifier training to ensure signal-preserving optimization. Importantly, because both representation methods are compared under identical training conditions, the relative comparison remains valid. We include this as a limitation and an area for future improvement.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Comparison of BERT4Rec and Fine-Tuned ELECTRA

The main goal of this study is to determine which approach to learning customer representation, training BERT4Rec from scratch or fine-tuning a pre-trained ELECTRA model, delivers better performance in predicting customers’ next purchases. To ensure a fair comparison, we identified that using only basic classifier settings of Random Forest provides a consistent evaluation framework.

Table 3 summarizes the performance of both models. Although there is no significant difference between AUC and F1-scores, the fine-tuned ELECTRA achieves an average AUC of 0.613, outperforming BERT4Rec by 0.012. This slight improvement in AUC demonstrates that ELECTRA has a marginally better ability to distinguish between customers who will make a purchase and those who will not. Meanwhile, BERT4Rec achieves an F1-score of 0.025, which is 0.007 lower than the F1-score of the fine-tuned ELECTRA.

A closer examination of the product-level results in

Table 3 shows that performance differences are largely driven by the underlying behavioral distributions of each category. Fine-tuned ELECTRA achieves substantial gains in products with frequent or regular customer activities. For example, in the water purifier category, ELECTRA improves AUC from 0.695 to 0.817 and increases the top 10% lift from 3.21 to 6.88, the largest margin observed across all products. Similar improvements appear in LG Objet (+0.031 AUC) and Refrigerators (+0.008 AUC), reflecting that ELECTRA adapts well when the behavioral signals are dense and consistent.

In contrast, categories with sparse or irregular interactions show weaker benefits from fine-tuning. LG Styler and LG Gram, which have fewer and more heterogeneous customer behaviors, exhibit small or negative changes in AUC (e.g., 0.615 to 0.592 for LG Styler) and F1. In these cases, BERT4Rec occasionally performs comparably or slightly better, likely because training from scratch on domain-specific tokens allows the model to fit the localized behavioral structure more effectively.

These observations clarify that ELECTRA is advantageous in behavior-rich environments, while BERT4Rec can remain competitive in sparse categories, providing a more detailed understanding of where each model excels in industrial customer behavior modeling.

Additionally, in terms of top 10% lift, which measures how well the model identifies high-value customers within the top 10% of predictions, the fine-tuned ELECTRA surpasses BERT4Rec by 0.27. This metric is particularly important for targeted advertising, where marketing efforts are concentrated on the most likely buyers. Given that the real purchase rate in the dataset is only about 0.5% of all customers, this improvement in precision within the top predicted segments has a significant impact. Even a modest increase in the top 10% lift means that the model is more effective in narrowing down the high-probability customers, allowing businesses to allocate resources more efficiently and potentially increase revenue. This highlights the practical value of fine-tuned ELECTRA in real-world marketing scenarios. From an operational perspective, the top 10% lift directly translates into advertising efficiency: even a 0.27 improvement implies significantly more correct high-value customer targeting under fixed marketing budgets. We also report that ELECTRA requires substantially lower inference time and smaller model footprint than BERT4Rec and LLaMA2, making it more suitable for large-scale deployment.

Although statistical tests such as permutation testing could be applied to quantify significance, the AUC and F1 differences observed across the eight independent product-level tasks are very small and exhibit high cross-task variance. Because our primary deployment-driven evaluation metric is the top 10% lift, which already shows substantial and practically meaningful differences, we focus on operational significance rather than statistical significance. Further, given the heterogeneity of product-level tasks and very small numerical gaps in AUC/F1, statistical significance tests provide limited interpretive value. Instead, we focus on the top 10% lift, which shows meaningful deployment-relevant differences.

5.2. Follow-Up Questions and Explorations

5.2.1. Selection for the Classifier

To examine the suitability of different downstream classifiers, we conducted a sample evaluation using only the refrigerator category, which provides a representative subset of customer behaviors.

Table 4 presents the performance of six widely used models on this dataset. Random Forest achieves the highest accuracy (0.65) and F1-score (0.55), showing consistent improvements over boosting-based models such as XGBoost and LightGBM, as well as logistic regression. Precision is also highest for Random Forest (0.75), indicating a strong ability to identify customers with higher purchase likelihood. Although several models exhibit similar recall values, Random Forest provides the best balance across all metrics in this sample test. Based on this comparative analysis, Random Forest was chosen as the primary classifier for evaluating the representations produced by BERT4Rec and ELECTRA.

5.2.2. Explanation for High AUC Scores of Water Purifier

When evaluating the classifier performance of each product, the results in terms of AUC scores are roughly equivalent between BERT4Rec and ELECTRA, except for a notable deviation for water purifiers, where both models exhibit particularly high accuracy (BERT4Rec: 0.695, fine-tuned ELECTRA: 0.817). To investigate why the classifier of the water purifier shows better performance than others, we analyzed the distribution of customer behaviors across the eight predefined actions.

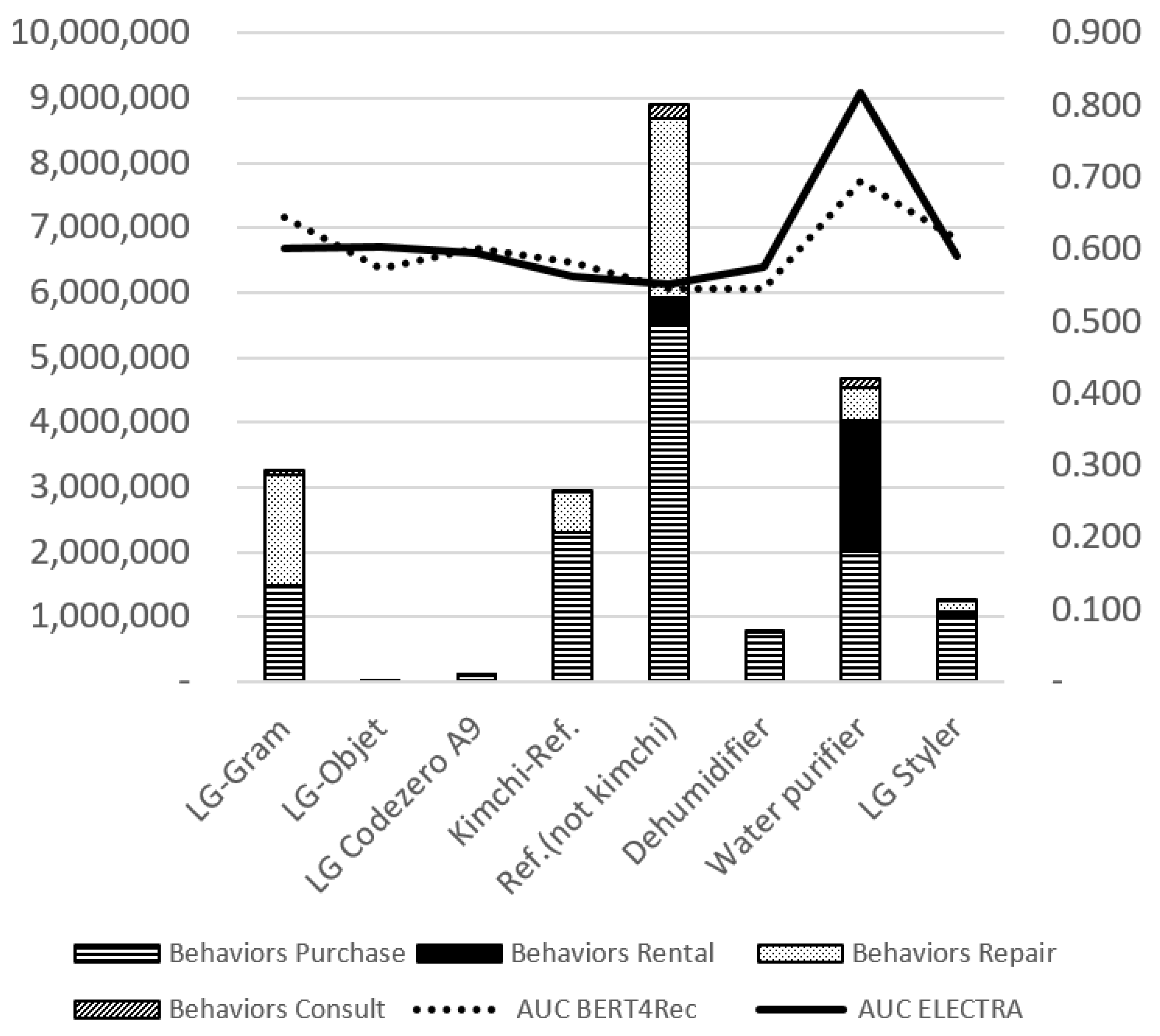

As depicted in

Figure 2, the AUC for water purifiers, with a data volume of 9 million records, is 0.264 higher for ELECTRA compared to refrigerators. Even the name of our laptop product, LG Gram, has a similar volume of purchase with that of the water purifier, and the AUC difference is around 0.216. In contrast, the differences observed with BERT4Rec are smaller, at approximately 0.15 and 0.05, respectively. We hypothesize that this disparity stems from the difference in how each model learn customer representations, training a model from scratch and fine-tuning a pre-trained model. Moreover, we observe that fine-tuning demonstrates superior performance when the data distribution is more balanced, a finding that has also been validated in previous studies [

36,

37].

5.3. Comparison of Accuracy and Precision of Binary Classification

We were able to confirm that Random Forest was the best among the results of ELECTRA, and we compared the results with BERT4Rec. The random forest classifier trained on latent vectors generated by fine-tuned ELECTRA outperformed BERT4Rec in all evaluation metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. These results demonstrate the effectiveness of fine-tuning a pre-trained model for domain-specific customer behavior prediction. In particular, the accuracy difference was more pronounced for certain product categories, such as water purifiers, indicating a nuanced advantage in specific contexts.

The superior performance of fine-tuned ELECTRA is attributed to its ability to leverage pre-trained knowledge during fine-tuning, enabling it to capture domain-specific nuances more efficiently than BERT4Rec. The results support the hypothesis that pre-trained models provide a more robust starting point for representation learning compared to training a new model from scratch. Future work may explore the impact of alternative classifiers and hyperparameter optimization to further improve prediction accuracy. Fine-tuned ELECTRA shows benefits, which are particularly effective for sparse, heterogeneous customer sequences. In contrast, BERT4Rec may suffer from limited vocabulary expressiveness despite domain-specific tokenization. We also acknowledge that the latent space remains difficult to interpret quantitatively; future work will incorporate explainability techniques such as sparse autoencoder-based feature extraction or contrastive objectives.

5.4. Comparison of Lift Divided by 10%

Since it usually forms a target group of customers to advertise based on the top x%, the top x% result is actually more important to expose advertisements to customers.

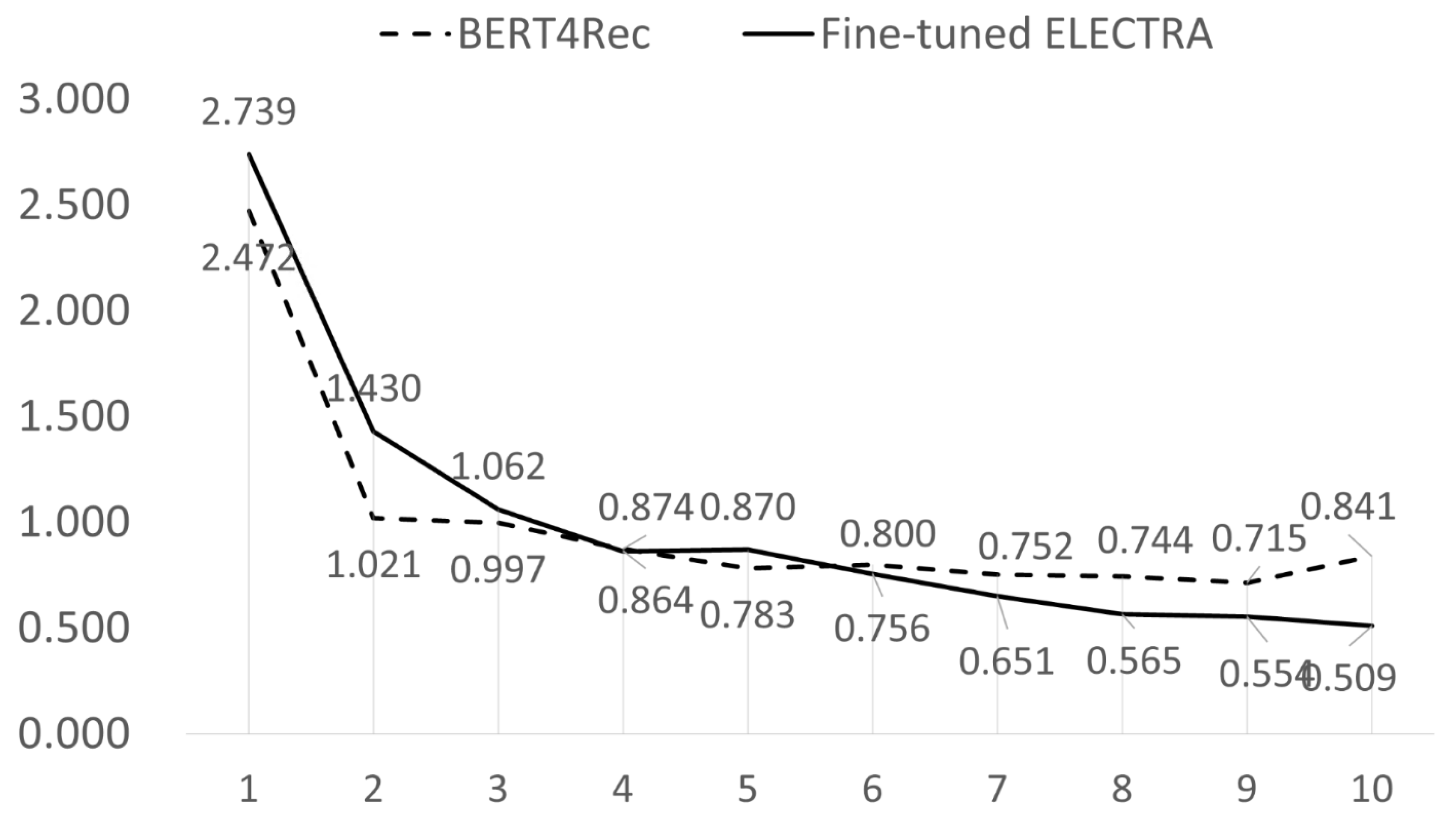

Figure 3 shows the lift result value of BERT4Rec and ELECTRA for each section after dividing the total data by 10. ELECTRA is confirmed to have a larger value of the upper lift collectively. Therefore, in this study, we believe that the fine-tuning version of step (2-2), the pre-trained ELECTRA, performs better because ELECTRA differs more clearly between the two models with little difference in accuracy.

Lift analysis reveals that the fine-tuned ELECTRA model achieves a higher lift in the top deciles compared to BERT4Rec. The top 10% of customers, ranked by predicted probabilities, exhibited a significant increase in purchase likelihood for ELECTRA. This result underscores the model’s ability to identify high-value customers more effectively.

In marketing applications, lift analysis is critical for targeting efforts, as it quantifies the benefit of focusing on the most likely responders. The stronger lift demonstrated by ELECTRA highlights its utility in real-world scenarios, where accurate segmentation of high-value customers can significantly enhance marketing ROI. Future research could investigate the integration of cost-sensitive learning techniques to optimize lift further in resource-constrained environments.

5.4.1. Challenges in Identifying Patterns Through 2-Dimensional Analysis

In an effort to visualize and interpret the latent space learned by the fine-tuned ELECTRA, we attempted to plot customer embeddings (e.g., using t-SNE or UMAP) and observe any meaningful separation between buyers and non-buyers [

12,

13,

14]. As shown in

Figure 4, most customer embeddings are located very close and are classified as a small number of clusters. This suggests that while the embeddings contain sufficient information for accurate predictions, their high-dimensional semantics cannot be easily separated into distinct groups in a two-dimensional projection. This aligns with broader challenges in interpreting LLM-based vectors, where multiple overlapping factors (e.g., product categories, temporal sequencing, and customer demographics) may blur distinct cluster boundaries [

15,

16].

5.4.2. Attention Variation of ELECTRA Before and After Fine-Tuning

We also analyzed the attention patterns of the ELECTRA before and after fine-tuning to understand how domain-specific data affects the relationships among the eight defined actions (e.g., buying, consulting, and repairing). Using AttentionViz [

17], we observed significant shifts in specific layer-head combinations, as illustrated in

Figure 5. Attention visualization provides qualitative insights but does not constitute quantitative validation. Because customer sequences contain overlapping semantic factors, certain product categories naturally exhibit inconsistent performance. We added this clarification and acknowledge the need for more rigorous interpretability methods.

In Layer 0, Head 0, the general-purpose context attention transformed into a more domain-specific pattern after fine-tuning, showing strong connections between receiving and buying actions. This suggests that customers who receive loyalty points are more likely to make purchases, and the model has effectively captured this relationship during fine-tuning.

In Layer 3, Head 2, we identified a strong link between consulting and buying, indicating that fine-tuning enhances the model’s ability to recognize that customers who consult are more likely to make a purchase. Moreover, consulting and buying also co-occurred in at least four other heads, further emphasizing that consultations play a significant role in predicting purchasing behavior of our customers.

These findings highlight that fine-tuning reorients the model’s attention from general language patterns to domain-specific insights, demonstrating the value of tailoring LLMs to focused, real-world datasets.

5.4.3. Fine-Tuned ELECTRA vs. LLaMA2

To investigate whether ELECTRA remains an optimal solution despite its older architecture and smaller latent dimensionality, we compare it with a fine-tuned LLaMA2 [

18]. Both models follow the same procedures described in step (2-2) and step (3). Instead of evaluating all product categories, we focus on the prediction results of two products: water purifiers, which achieved the highest accuracy in prior experiments, and refrigerators, which show the highest sales volume.

As shown in

Table 5, the results reveal no significant differences in predictive accuracy between the two models. However, when comparing model sizes, ELECTRA’s smaller footprint offers practical benefits, making it more suitable for large-scale industrial use. This reinforces its effectiveness in scenarios requiring computational efficiency.

6. Conclusions

This study compared two approaches to learning customer representations using LLM: training BERT4Rec from scratch and fine-tuning ELECTRA. The results of the downstream task (next purchase prediction) on step (3) show that fine-tuned ELECTRA performs slightly better, with improvements in AUC (+0.012) and top 10% lift (+0.27). Its computational efficiency also makes it suitable for large-scale applications. This study provides practical insights for embedding customer behaviors and highlights areas for further research to enhance the application of LLMs in real-world scenarios. These preliminary trials under the original 0.5% purchase rate resulted in near-zero recall for positive cases, and a more systematic imbalance-aware evaluation is left for future work. Although simpler sequential models (e.g., LSTM, GRU) could serve as baselines, our study specifically isolates the effects of training strategy within LLM-based architectures. We plan to extend future work to include additional baselines for broader comparison.

However, challenges remain in interpreting the high-dimensional latent spaces generated by LLMs. Dimensionality reduction and attention analysis revealed that extracting meaningful patterns is difficult. Future work for learning customer representations should focus on improving interpretable methods like sparse autoencoders and enhanced attention analysis. In addition, we tested imbalanced training scenarios but observed unstable convergence and degraded predictive quality. Because our application prioritizes high-recall identification of potential buyers, the balanced training setup remains appropriate for evaluation. We list this as a methodological limitation.

Overall, the experiments confirm that both BERT4Rec and ELECTRA can yield strong performance on next-purchase prediction tasks, with ELECTRA showing particular promise for rapid deployment and actionable marketing insights. Future work may explore ensemble strategies or hybrid approaches that harness the best of both worlds, combining the specificity of domain-defined tokens with the adaptability of pre-trained models. Another limitation is that we did not conduct extensive hyperparameter tuning for either model. A more systematic search may change the absolute performance and slightly adjust the performance gap, and we leave this for future work.

Despite the insights gained from our AttentionViz analysis, a key limitation arises from the inherent complexity of LLM-based latent spaces. Recent studies suggest that dimensional interference makes it challenging to accurately interpret latent vectors when they are projected into just two dimensions, as crucial semantic information may be lost or distorted. Sparse Autoencoder–based approaches are increasingly employed to mitigate these issues by preserving more structure during dimensionality reduction. Exploring such methods in conjunction with our existing framework presents a promising avenue for future research.

Additionally, this study primarily focused on fine-tuning and training methods for LLMs, comparing domain-specific token creation against leveraging pre-trained models. However, contrastive learning has recently gained significant traction in representation learning. In subsequent work, we plan to investigate contrastive approaches for customer behavior modeling—treating each defined action as a distinct embedding target and applying contrastive objectives to more robustly separate relevant behaviors across customers. This direction holds potential for further enhancing the interpretability and predictive power of latent representations in large-scale industrial applications.

Beyond representation accuracy, the study has limitations due to imbalanced real-world purchase rates and challenges in high-dimensional latent space interpretation. Future work will explore contrastive learning formulations tailored to customer actions, interpretable embedding extraction using sparse autoencoders, and expanded baseline comparisons including non-LLM sequential models.