1. Introduction

1.1. Increasing Demands for High-Energy, High-Power Electron Accelerators

The radiation processing industry constitutes one of the most technologically comprehensive and economically influential sectors within non-power nuclear applications. Modern irradiation infrastructures predominantly consist of cobalt-60 (

60Co) facilities and electron-beam (EB) accelerators. Historically,

60Co irradiators dominated the field owing to their technological maturity and operational reliability. However, the tightening of environmental and radiological safety regulations, together with growing geopolitical and supply chain risks surrounding radioactive cobalt sources, has accelerated a global transition toward EB-based irradiation technologies [

1,

2,

3]. Benefiting from their high electrical efficiency, precise dose controllability, and intrinsic freedom from radioactive materials, EB accelerators are now widely adopted in advanced manufacturing, agricultural production, medical sterilization, public health, and environmental remediation [

4,

5,

6].

Over the past decades, several classes of electron accelerators have achieved industrial maturity, including electrostatic accelerators, linear electron accelerators, and reentrant accelerators. Electrostatic accelerators—typically Van de Graaff or Dynamitron types—have long served irradiation applications but are fundamentally constrained in attainable beam energy and current. In contrast, high-power electron linear accelerators have enabled substantially higher output capabilities; for example, the ILU-14 series developed in Russia delivers 7.5–10 MeV electron beams with powers approaching 100 kW and has been successfully deployed in large-scale industrial irradiation facilities. Reentrant accelerators represent another major technological route, with the Rhodotron and ridgetron being the most prominent designs. The Belgian company IBA has achieved industrial-scale production of rhodotron-type accelerators [

7,

8]. Meanwhile, Noriyosu et al. in Japan demonstrated a ridgetron accelerator in 2002 capable of producing 2.5 MeV, 2.5 mA beams [

9]. More recently, the China Institute of Atomic Energy (CIAE) advanced the development of ridgetron technology, designing a system capable of delivering 10 MeV electron beams at an average power of 50 kW [

10,

11,

12]. These developments collectively highlight the growing industrial demand for high-power accelerators that combine compact structure, high efficiency, operational robustness, and long-term economic viability.

1.2. Need for Effective Longitudinal Beam Bunching

For high-power industrial accelerators, where stable operation and high efficiency are essential, an effective longitudinal bunching system is therefore a key component.

In high-power electron accelerators, particularly those operating in continuous-wave (CW) or high-duty-cycle modes, the quality of the electron beam injected into the main accelerating cavity critically influences overall acceleration efficiency. Electron guns typically generate beams with relatively long pulse widths and diffuse phase distributions. If such unconditioned beams are injected directly into the ridgetron cavity, only a fraction of the electrons will reside within the effective accelerating phase. Consequently, beam capture efficiency is reduced, energy-transfer performance deteriorates, and the RF system must provide additional power to sustain the required accelerating field.

Insufficient beam capture also increases the likelihood of electrons striking accelerator components rather than being effectively accelerated. In high-power systems, these losses lead to elevated thermal loads, enhanced outgassing, and potential damage to critical components. For accelerators intended for prolonged operation, These effects may gradually accumulate, thereby undermining the stability and reliability of the system. To address the above issues, a longitudinal buncher is typically installed between the electron gun and the main ridgetron cavity. The buncher imparts a controlled RF-induced velocity modulation along the beam axis, causing electrons to compress longitudinally into well-defined microbunches after a drift section. These microbunches are phase-synchronized with the main accelerating field, thereby enhancing capture efficiency, reducing beam loss, and improving the overall utilization of the beam power.

For high-power industrial accelerators, where both operational stability and energy efficiency are critical, an optimized longitudinal bunching system constitutes a key component of the front-end injector section.

1.3. Status and Limitations of Existing Buncher Technologies

In modern electron accelerators, the choice of buncher plays a crucial role in determining beam capture efficiency, phase stability, and overall beam quality. Various types of bunchers have been developed to meet the diverse requirements of high-current and high-power systems. The ballistic buncher [

13] offers a simple pre-bunching solution that improves beam capture, although it necessitates a separate RF cavity and drift space. Direct injection without a buncher provides the simplest configuration but suffers from poor capture efficiency and large energy and phase spreads, making it suitable only for systems with high-voltage injection or where beam transmission is not critical. Waveguide bunchers, designed either with phase velocity equal to the injection velocity or higher, can achieve high capture ratios and reduced energy spread; however, they often require low-β cavities or high-voltage injection, and single-section designs may limit performance at high amplitudes. Multi-section bunchers offer improved capture efficiency and beam quality compared with single-section configurations but introduce more complex beam dynamics and RF tuning requirements. Finally, tapered velocity bunchers provide the highest capture efficiency and optimal beam parameters, enabling simultaneous acceleration, but involve the most challenging RF and mechanical design considerations. Overall, the selection of a buncher entails a trade-off between simplicity and performance, with bunching being particularly critical for high-current, high-power accelerators to enhance phase capture and minimize beam loss [

13].

However, it is worth noting that there is no single buncher design universally suitable for all applications. In high-energy, high-power accelerators, the ballistic buncher is widely used, typically implemented as an independent RF cavity separated from the main accelerating structure by a drift space. Currently, ballistic bunchers are predominantly realized through coaxial RF cavities operating in the TEM mode, with their resonant frequency typically matched to that of the main accelerating cavity or set to a sub-harmonic.

Examples include the subharmonic prebuncher in the FEL project at the China Institute of Atomic Energy [

14], the subharmonic buncher of the 150 MeV linear accelerator at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility [

15], and the subharmonic buncher of the Beijing Electron–Positron Collider II (BEPC II) project [

16]. These implementations highlight the practical utility of ballistic bunchers.

1.4. Motivation for a T-Shaped Buncher

In modern high-power, high-current linear accelerators, achieving efficient beam capture while maintaining superior beam quality is essential to overall accelerator performance. At the same time, contemporary accelerator systems are increasingly expected to satisfy requirements of reliability, cost-effectiveness, and operational adaptability. Although conventional coaxial bunchers can provide effective longitudinal modulation of the electron beam prior to its injection into the main accelerating structure, they exhibit inherent limitations in terms of system compactness, RF field uniformity, power-handling capability, and tuning flexibility.

To address the above issues, a T-shaped buncher cavity is proposed. Its T-shape geometry enables a compact integration between the electron gun and the main accelerating structure at relatively low operating frequencies, while still maintaining effective longitudinal modulation of the electron beam. At the same time, the introduction of the T-shaped structure alters the electromagnetic boundary conditions, allowing the RF field to redistribute over a larger volume and thereby achieving a more uniform field distribution. Compared with a conventional single-cell coaxial buncher, the T-shaped configuration significantly reduces the central field peak and radial gradient, thus mitigating transverse field non-uniformity. Moreover, the T-branch structure of the buncher helps to distribute the high-power, reducing local overheating and power dissipation. The T-geometry also provides enhanced tuning flexibility, as adjustments to the transverse branch allow convenient control of the resonant frequency and RF field distribution.

1.5. Objective of This Work

The objective of this study is to design and simulate a T-shaped coaxial buncher for high-power ridgetron accelerators, with the aim of enhancing beam capture efficiency and reducing beam loss in the accelerator system. The scope of this work includes the physical design of the T-shaped buncher, three-dimensional electromagnetic simulations, optimization of the key structural parameters, and comprehensive analyses of the field distribution and bunching performance. The study further demonstrates the feasibility of integrating the proposed structure into high-power ridgetron accelerators and highlights its advantages in improving the overall accelerator performance.

2. 10 MeV, 50 kW Ridgetron Accelerator

The 10 MeV/50 kW ridgetron accelerator developed by the China Institute of Atomic Energy (CIAE) consists primarily of two resonant accelerating cavities, deflection magnets, and a grid-controlled electron gun. The accelerator system adopts dual resonantcavity configuration, in which a high-current electron beam emitted from the grid-controlled electron gun is focused and matched by a solenoid before being injected into the first resonant accelerating cavity. After passing through the accelerating gap, the electrons gain an energy increment of approximately 0.5 MeV. The accelerated beam is then extracted from the first cavity and injected into the second resonant cavity for further acceleration. A deflection magnet subsequently bends the electron beam by 180°, enabling it to be re-injected into the second resonant cavity for multiple back-and-forth acceleration cycles. Through this recirculating acceleration process, the beam energy is ultimately increased to 10 MeV. To further reduce beam losses and enhance capture efficiency, a buncher is proposed to be installed between the grid-controlled electron gun and the ridge-type resonant cavity. The schematic diagram of the final ridge-type accelerator system is presented in

Figure 1.

3. Principle of T-Shaped Buncher

The T-shaped buncher is an important part of the linear accelerator for modulating the electron beam emitted by the electron gun into an electron beam bunch with narrower pulse width, higher density and more concentrated phase. Its main function is to use the RF electric field to modulate the longitudinal velocity of the electron beam, so that the electrons form dense bunches in the subsequent drift section. This bunching process is the key to achieve high capture efficiency and high beam quality for high frequency linear accelerators. When the electron beam passes through the buncher, electrons at different phase positions experience different longitudinal electric fields, and thus acquire different changes in velocity. The electron energy in the accelerating phase of the electric field increases, while the electron energy in the decelerating phase decreases. Subsequently, in the drift section, due to the accumulation of velocity difference, the latter catches up with the former and gradually forms an electron-dense beam, thereby achieving longitudinal bunching.

This process can be divided into two stages:

Velocity modulation stage: the electron passes through the bunch gap and is subjected to a high-frequency electric field that changes with time, resulting in energy modulation;

Space bunching stage: The electrons whose energy is modulated fly in the drift segment. Due to the velocity difference, the electrons re-converge at a certain position to form a bunch.

The specific schematic diagram is shown in the following

Figure 2.

4. Structure Design and Simulation Analysis of T-Type Buncher

4.1. Design Rationale and Equivalent-Circuit-Based Theoretical Analysis

To meet the stringent compactness requirements of modern electron irradiation accelerators, the available space between the electron gun and the main accelerating cavity on the injection side of the ridgetron is extremely limited. Under such spatial constraints, the buncher must provide sufficient longitudinal modulation voltage within a shortened axial length, while ensuring manufacturability and maintaining electromagnetic stability during high-power operation. However, conventional coaxial TEM buncher cavities become excessively long at low operating frequencies, and the electric field is highly concentrated near the inner conductor, which not only complicates compact integration but also increases transverse field components, leading to beam divergence and reduced beam capture efficiency.

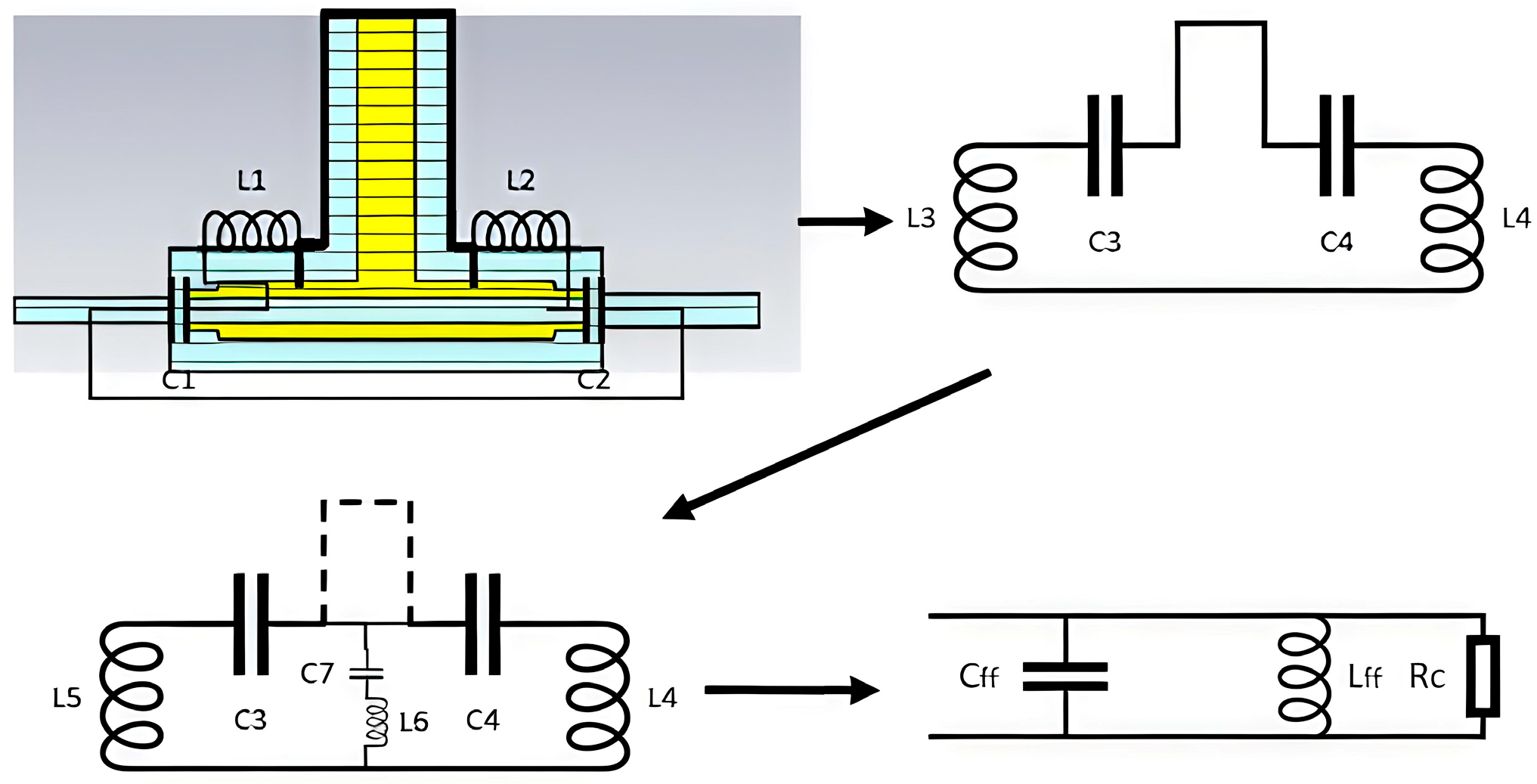

To address these challenges, a T-shaped coaxial buncher is proposed. Its frequency characteristics and impedance matching can be analyzed using an equivalent circuit model. The equivalent circuit is shown in

Figure 3. In this simplified model, the T-shaped buncher can be represented as a combination of a gap capacitor and a short-circuited coaxial cavity: the gap capacitor provides the longitudinal electric field required for bunching, while the short-circuited coaxial cavity serves as the energy storage resonator [

17]. The acceleration gap is approximated as a capacitance

, the loop formed by the central conductor and the outer shell as an inductance

, and the T-shaped branch is treated as an additional capacitive branch from the perspective of the longitudinal electric field. Using this equivalent circuit, the fundamental-mode resonant frequency of the buncher can be estimated by the standard LC formula:

where

represents the effective inductance of the combined main cavity and branch, and

is the sum of the capacitances of the main cavity, the T-shaped branch, and the acceleration gap. It should be noted that this equivalent circuit is a simplified approximate model that considers only the input and output characteristics at the accelerating-gap end while neglecting the transition behavior of the RF field inside the resonant cavity. Therefore, its predictions of the resonant frequency and electric-field distribution must be validated through full electromagnetic simulations.

The inclusion of the T-shaped branch allows the resonant frequency to be reduced even with a shorter axial length compared to a conventional coaxial buncher. Simultaneously, the effective cavity volume is increased, which improves the uniformity of the longitudinal electric field and enhances the peak modulation voltage. These characteristics make the T-shaped buncher particularly suitable for achieving compact integration while maintaining high bunching performance in modern high-power ridgetron accelerators.

4.2. Geometric Parameters of T-Shaped Buncher Cavity

The T-shaped buncher cavity designed in this paper is shown in

Figure 4. The key geometric parameters of the cavity are as follows: cavity length C, cavity height H, outer conductor radius

Rc, inner conductor radius

Ri, and acceleration gap length G—are indicated in

Figure 5.

4.2.1. Cavity Length

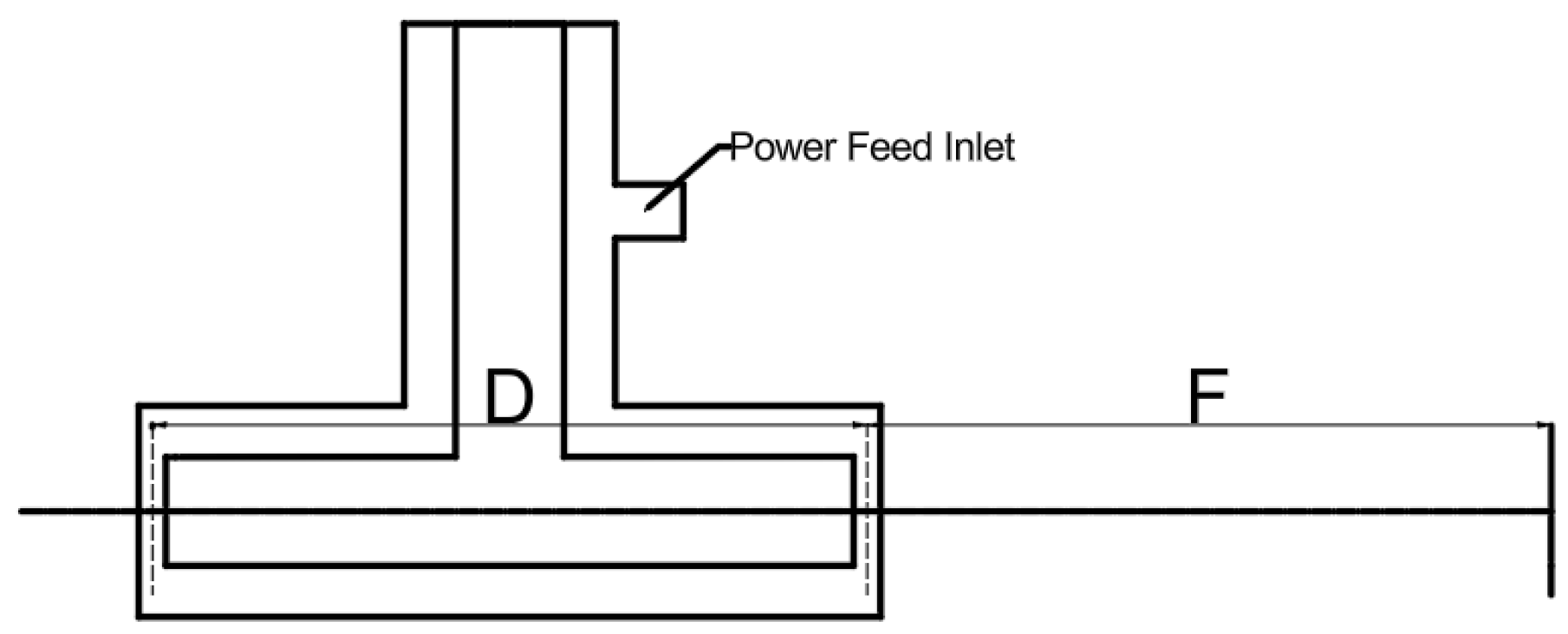

The double-gap structure is adopted in the T-cavity buncher [

18]. The structure principle is shown in

Figure 6. Two modulation slots are formed on both sides of the inner and outer conductors of the buncher. After the power is fed through the power feed inlet, the bunching electric field is formed in the modulation slot.

In order to make the particles have the same modulation effect when passing through the two bunching gaps, the distance between the center of the bunching field D is required to be the distance of the central particle flying at the odd multiple time interval of the half cycle [

19], that is:

E is the energy of the accelerating electron, the unit is eV, me is the mass of the electron, the unit is Kg; c is the speed of light, the unit is m/s, f is the frequency of the modulation signal of the prebuncher, the unit is Hz, Ve is the particle velocity, the unit is m/s, T is the period of the modulation signal of the prebuncher, the unit is s. For the designed T-shaped buncher, the energy of the injected electrons is 35 keV, and the modulation signal frequency is 100 MHz. The distance between the two acceleration gaps should be 528 mm.

4.2.2. Cavity Radius, Inner Conductor Radius and Gap Length

The T-shaped buncher cavity adopts a coaxial resonant structure, with the outer conductor radius and inner conductor radius jointly determining the resonant frequency and electric field distribution. For the T-shaped coaxial configuration, the resonant frequency can be increased by reducing or increasing ; however, an excessively small inner conductor radius may distort the field distribution and increase power loss. Based on measurements of the available space and to ensure that the assembly of the deflection magnet and buncher is not affected, was set to 78 mm in accordance with compactness requirements.

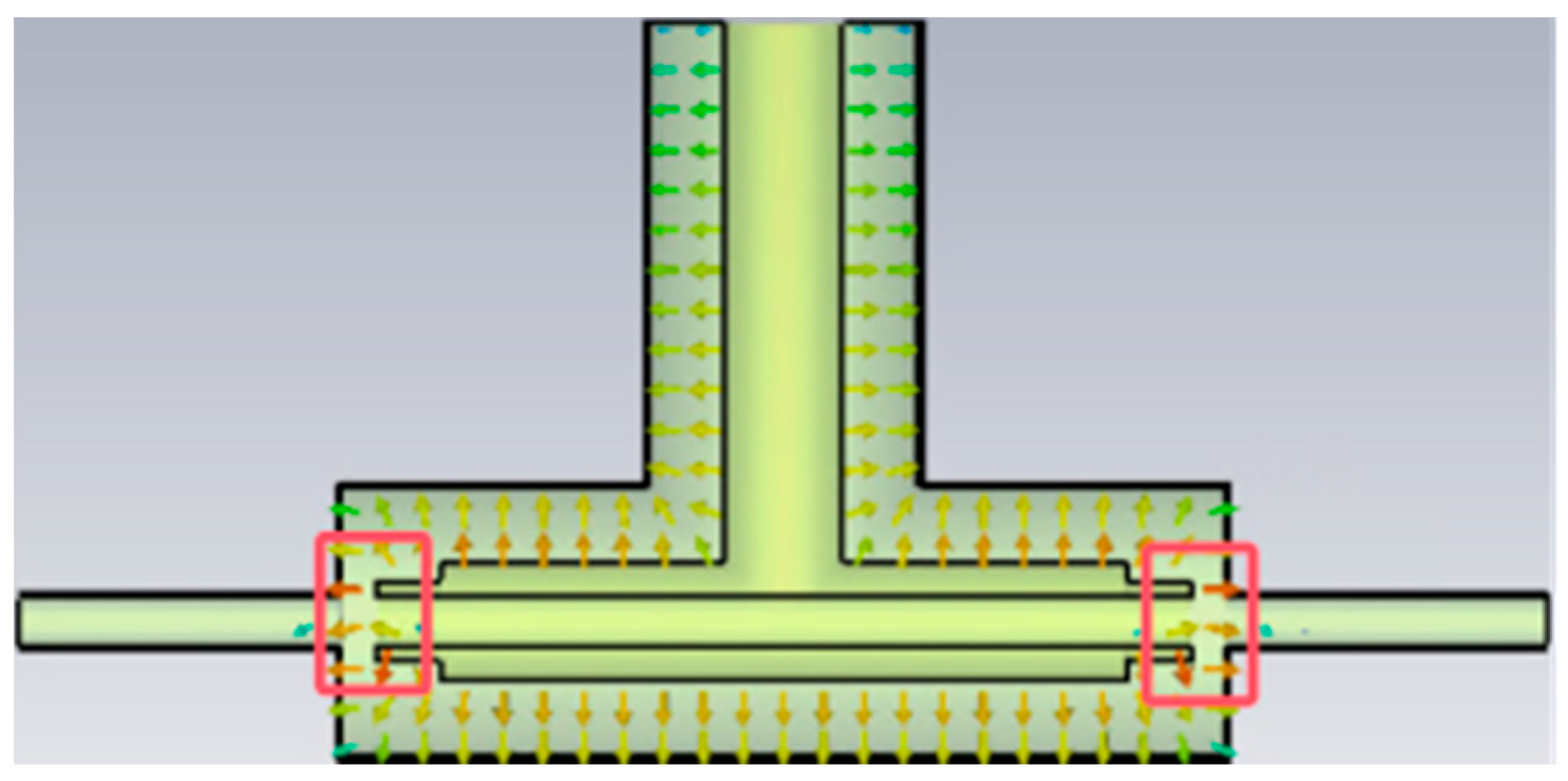

The high-frequency electric field within the bunching cavity critically influences the longitudinal modulation of the electron beam. A strong longitudinal field produces greater velocity modulation, resulting in tighter bunching in the drift section and significantly improving beam focusing and pulse width compression. For the designed T-shaped coaxial structure, the maximum surface electric field occurs at the end of the bunching gap adjacent to the drift tube, as shown in

Figure 7, and the field strength can be indirectly monitored via the maximum surface electric field. To avoid vacuum discharge and electrical breakdown, the Kilpatrick criterion was applied: at 100 MHz, the breakdown field is approximately 10.8 MV/m, setting the upper limit for the operating field [

20]. Therefore, a balance must be achieved between sufficient longitudinal modulation and safe operation.

Considering these factors, CST simulations were performed to study the influence of key geometric parameters on cavity performance. The distance between the two acceleration gaps

was set to 528 mm. To integrate with the electron gun and the main accelerating cavity, the beam pipe diameters at the electron gun and drift tube sides were set to 30 mm and 40 mm, respectively. Under the constraint of maintaining a resonant frequency of 100 MHz, multiple simulations were conducted by varying

,

,

. The resulting variations in maximum surface electric field and cavity quality factor

for different acceleration gap configurations are presented in

Figure 8.

According to

Figure 8, the acceleration gap is set to 20 mm, and the corresponding values of

RC,

Ri and H are 78 mm, 37 mm, and 372 mm, respectively.

4.2.3. Cavity Tuning Mechanism Design

In the manufacturing process of the bunching cavity, there is often a certain deviation in the actual processing size; at the same time, under high power operation conditions, the cavity material will undergo thermal deformation due to temperature rise. These factors will cause the shift in the resonant frequency of the cavity, resulting in the mismatch between the operating frequency of the bunching cavity and the frequency of the microwave source, affecting the effective transmission of microwave energy to the electron beam and reducing the bunching efficiency. Therefore, it is necessary to design a frequency tuning mechanism in the bunching cavity structure to achieve accurate adjustment of the resonant frequency. On the premise of ensuring that the electric field distribution in the acceleration gap is not significantly affected, the design of the tuning device should expand the adjustable frequency range as much as possible to improve the adaptability of the system operation.

The cavity tuner of the T-type buncher is designed at the bottom of the buncher, 150 mm from the center of the buncher, the tuning rod range is 2–40 mm, and the radius of the tuner is 17.5 mm.

4.2.4. Determination of the Final Design Data of the Cavity

After completing the multi-round simulation optimization of the above content, considering the factors such as cavity frequency, cavity quality factor, gap electric field strength, and cavity coupling degree, the final design parameters of the cavity are listed in

Table 1.

5. Calculation and Result Analysis of Buncher

5.1. Electromagnetic Field Simulation Results

The RF electromagnetic field of the buncher under the above dimensional parameters was simulated using CST’s Frequency Domain Solver. The buncher requires the introduction of high-frequency power through a coupling structure to establish the desired electric field distribution within the cavity. To reduce the output power demand of the microwave source, the cavity design should, on one hand, maximize the quality factor to minimize cavity power loss, and on the other hand, ensure good impedance matching between the high-frequency source and the cavity to minimize reflected power and improve energy transmission efficiency. The power was fed into the T-shaped buncher via a magnetically coupled coupling loop. The structural dimensions of the coupling loop were optimized through simulation in CST. The computational model of the buncher cavity and the coupler constructed in CST is shown in

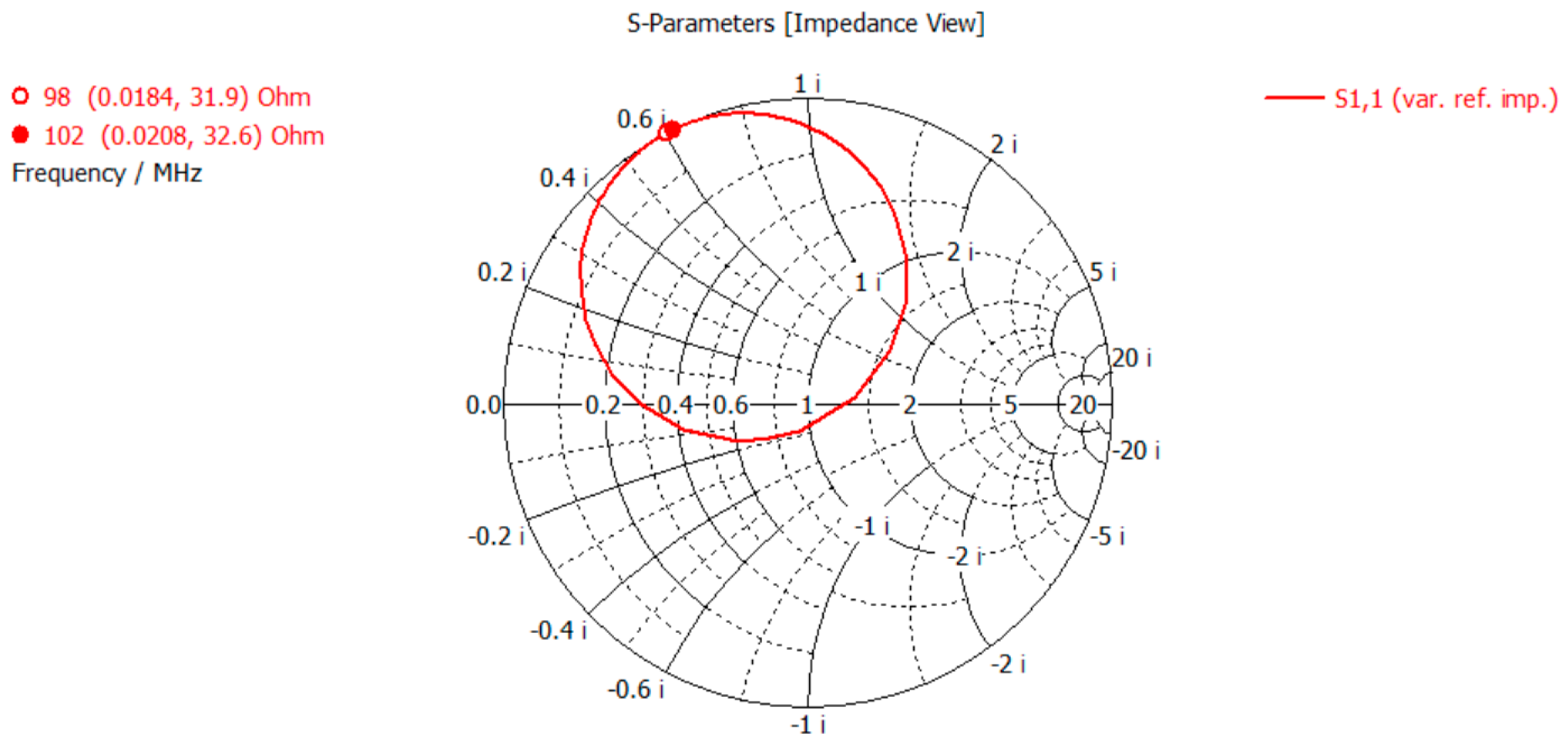

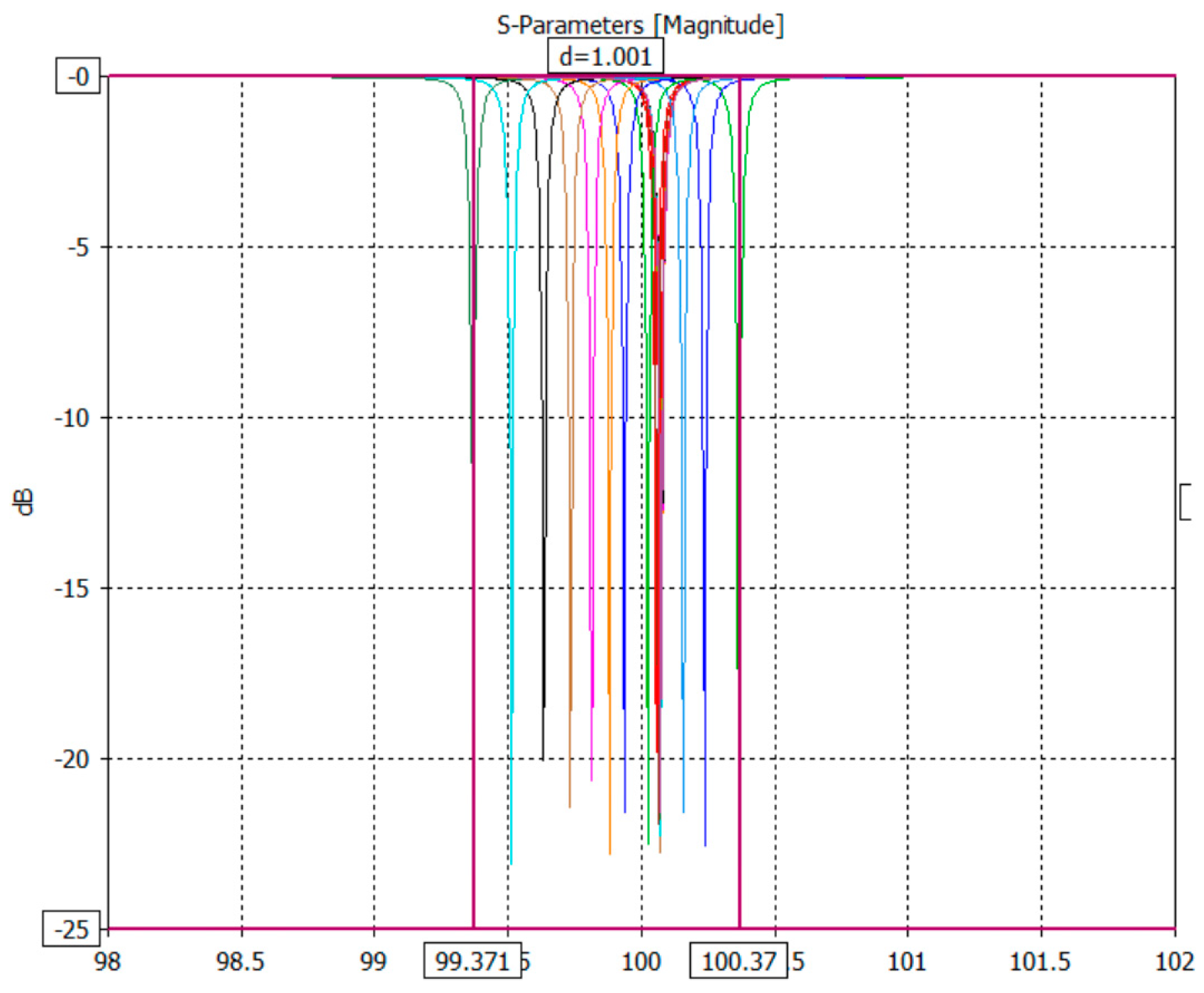

Figure 9, with both the interior and exterior of the cavity defined as vacuum, and the cavity walls and coupling loop conductors modeled as oxygen-free copper. The input port of the coupling loop was designated as Port 1, and a single-port calculation was performed on the cavity. Optimization was carried out with respect to two parameters: the size and the penetration depth of the coupling loop. By adjusting these parameters, the standing wave ratio at the port was minimized, achieving near-perfect impedance matching between the buncher and the transmission line. Simulation results indicate that with a coupling loop penetration depth of 7 mm and a radius of 9.05 mm, the resonant frequency is 100.03 MHz, S11 is below −20 dB, shown in

Figure 10, the input port of the coupler is perfectly matched, and the power is fully delivered into the buncher. The simulated electric field distribution within the buncher is shown in

Figure 11, and the corresponding Smith chart is presented in

Figure 12. Under a simulation with an input power of 0.5 W, the excitation produces a maximum electric field of 187 kV/m. With the allowable maximum input power of 200 W, the corresponding peak electric field reaches 3.7 MV/m, which remains below the breakdown threshold, thereby satisfying the design requirements. It can be inferred that the buncher cavity is in an over-coupled state, and the coupling coefficient at this condition can be estimated to be approximately 1.2 based on the S11 parameter.

To further clarify the influence of the electric field distribution on beam bunching efficiency, it can be observed from the simulated field patterns that regions with higher longitudinal electric field strength along the beam path contribute more effectively to accelerating slower electrons and decelerating faster ones, thereby enhancing velocity modulation. This velocity modulation leads to a gradual longitudinal compression of the electron beam, resulting in improved bunching efficiency. The uniformity of the field distribution along the cavity axis ensures that the bunching process is consistent across the beam cross-section, minimizing beam loss.

The tuner of the buncher is simulated. The variable range of the tuning rod is 10–40 mm, and the radius of the tuner is 17.5 mm. The frequency variation range caused by the tuning rod is about 1 MHz, as shown in

Figure 13.

5.2. Simulation of Bunching Effect

5.2.1. Simulation of Single Buncher Bunching Effect

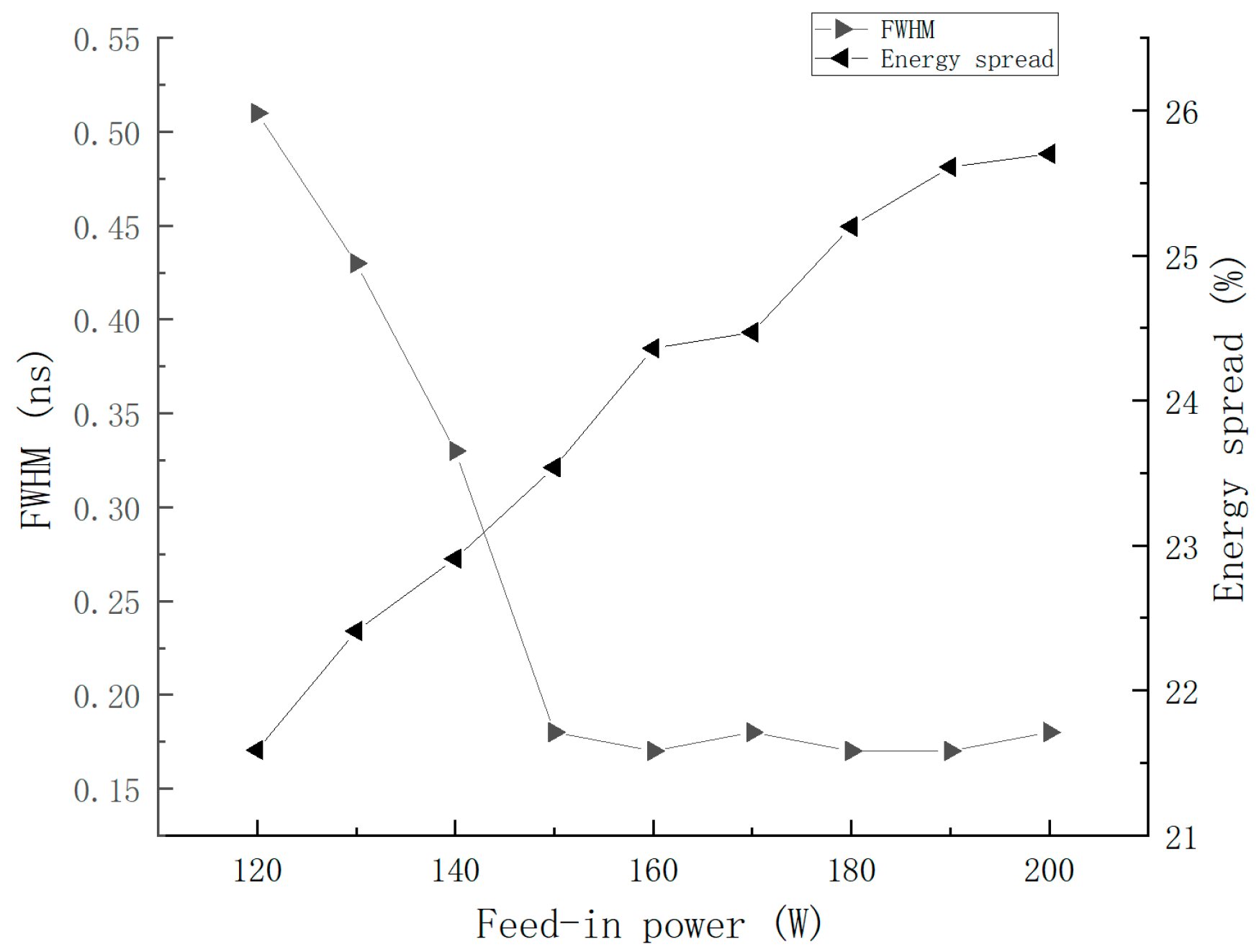

The longitudinal bunching characteristics of the buncher are simulated by using the Particle-in-Cell (PIC) solver in CST Studio Suite, focusing on the full width at half maximum (FWHM) and energy divergence of the electron beam after bunching. FWHM is a standard index to measure the bunching effect, which can directly reflect the degree of beam aggregation. Under the action of the bunching electric field, the longitudinal velocity of the electron beam is modulated, which can form an electron beam with narrow pulse width and concentrated phase, but at the same time, it will increase the energy divergence of the electron beam cluster, which will have a significant impact on the beam quality of the ridge accelerator during the acceleration and deflection of the beam into the main acceleration cavity. The different feed power will cause the difference in the bunching voltage, and the different bunching voltage will affect the electron beam velocity modulation intensity, resulting in different energy divergence changes. And the size of the bunching voltage is also inversely proportional to the drift distance after bunching. Therefore, the requirements of space and energy divergence will be considered comprehensively to simulate the bunching effect of the buncher [

21,

22].

The electron beam with energy of 35 keV and FWHM of 5 ns is injected into the bunching cavity. The high-frequency electric field frequency in the cavity is 100.03 MHz, and the input power is 120–200 W. The simulation results show that the electron beam undergoes longitudinal velocity modulation, and a high-density bunch with phase concentration is formed at the exit, as shown in

Figure 14. The variation in pulse width at 140 W power (

Figure 15) shows effective bunching.

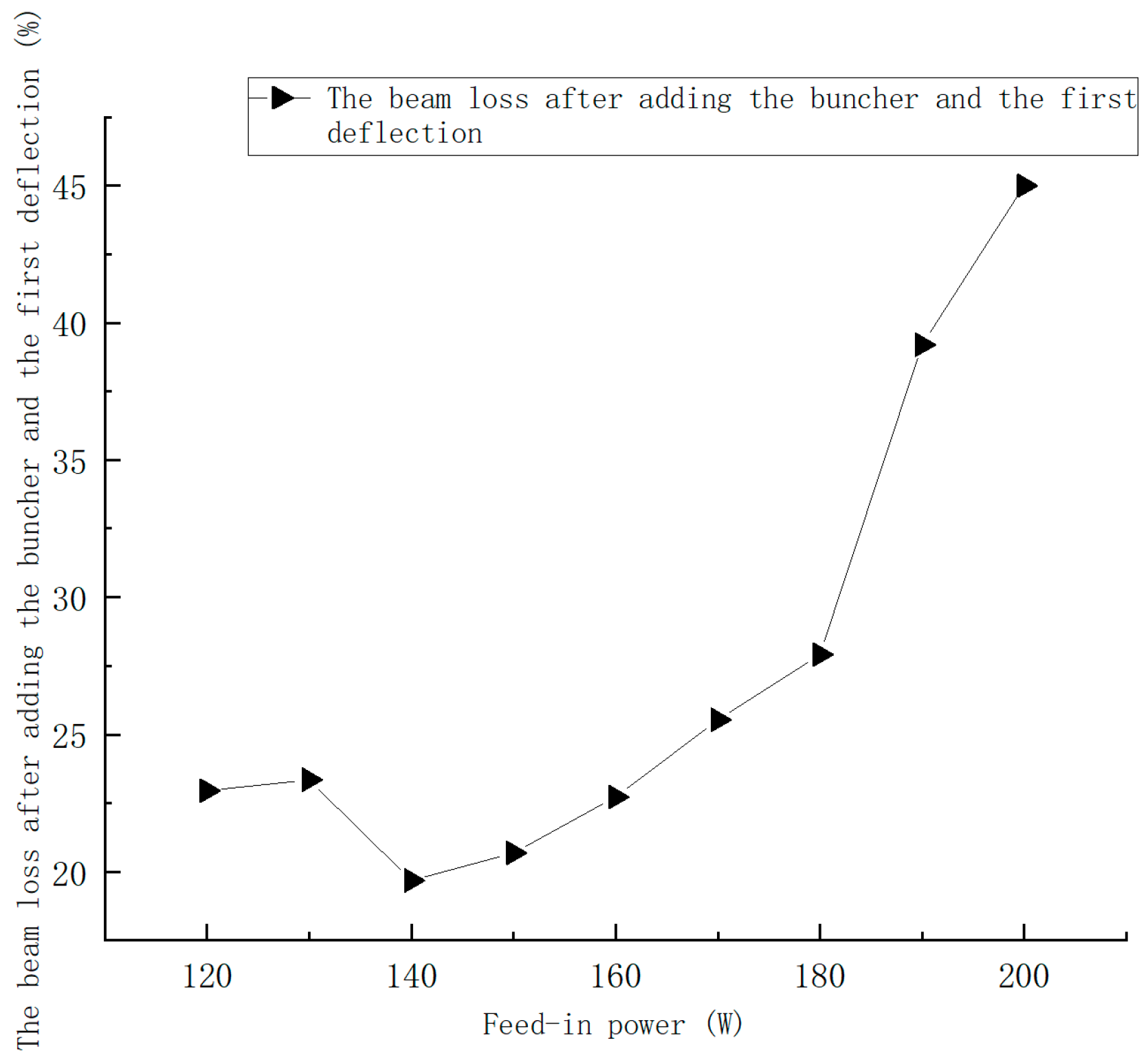

When the input power is set to 120–200 W, the corresponding bunch exhibits a FWHM compression range of 0.53–0.18 ns and an energy spread of 21.3–25.8%, as shown in

Figure 16. Within this power range, the drift section length varies from 1490 mm to 1700 mm, and the beam loss inside the bunching cavity is less than 0.5%, as shown in

Figure 17.

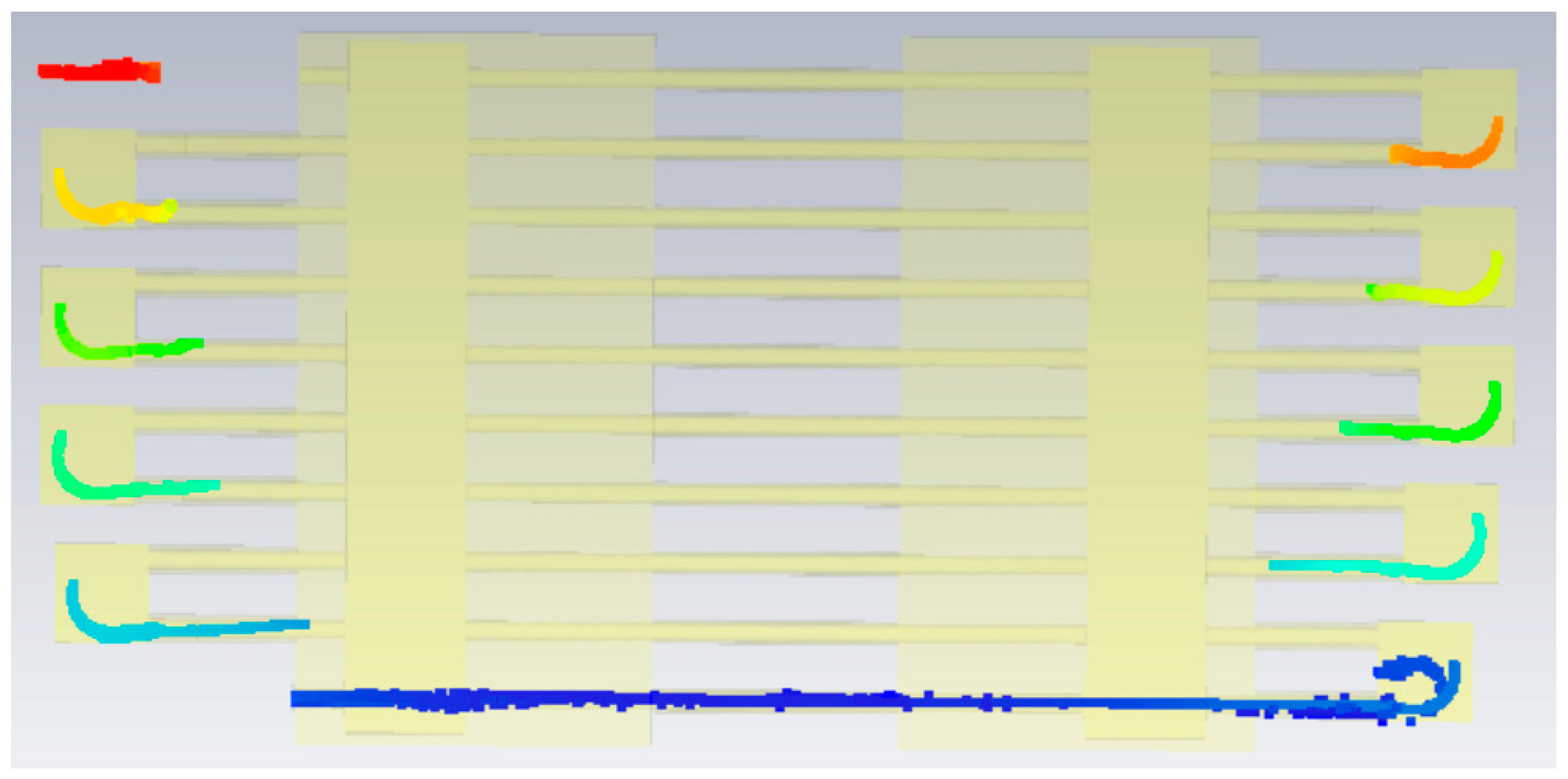

5.2.2. Ridge Accelerator System Simulation

In order to more accurately evaluate the dynamic characteristics of the electron beam in the acceleration system, this paper uses the PIC solver in CST Studio Suite to jointly simulate the designed buncher and the ridge acceleration cavity. The buncher is integrated between the electron gun and the ridge cavity accelerator cavity. By considering the electromagnetic coupling and beam modulation process of the two in the same model, the complete process of the electron beam from modulation to acceleration is obtained. As shown in

Figure 18.

In the joint simulation, the output from the single-buncher simulation in the previous section was used as the input for the main acceleration cavity. Multiple accelerating RF fields, deflection magnetic fields, and focusing magnetic fields were introduced in CST Particle Studio to realize a full-process simulation of the electron beam, from initial modulation to acceleration in the main cavity. In the simulation, the initial electron energy was set to 35 keV, and the initial bunch pulse width was set to 5 ns. The drift section length and the relative phase between the accelerating field of the main cavity and the buncher were adjusted to achieve optimal beam transport. The performance improvement provided by the buncher was evaluated by comparing the beam loss after the first deflection, thereby quantitatively assessing the influence of the buncher on beam transmission and capture efficiency in the ridge cavity accelerator. The simulation results are shown in

Figure 19.

As shown in

Figure 19, the beam loss after the first deflection is 19.8% at an input power of 140 W and 45% at 200 W. Meanwhile, when the buncher is not employed and the initial pulse width is 5 ns, the beam loss after the first deflection reaches 65%. The comparison indicates that the inclusion of the buncher reduces the beam loss by approximately 40%. However, when the initial pulse width is 5 ns, a portion of the beam loss arises from phase mismatch, as shown in

Figure 20. To further assess the performance of the buncher, simulations were conducted to compare the output beam current for an initial pulse width of 5 ns with and without the buncher. As shown in

Figure 21, the peak current reaches 0.25026 with the buncher, whereas it is only 0.08 in the absence of the buncher. These results demonstrate that, under identical conditions, the buncher substantially enhances the electron beam current, with the peak value being approximately 3.13 times higher than that of the non-bunched case. This confirms that the buncher effectively improves the longitudinal phase distribution of the beam, increases the bunch density, and enhances the overall current intensity.

6. Conclusions

In this study, the structural design and system-level simulation of a T-type buncher for a high-power ridgetron accelerator were conducted using CST Studio Suite. After confirming the adoption of the T-type buncher configuration, the eigenmode and frequency-domain solvers were employed to simulate and optimize the cavity geometry, electromagnetic field distribution, and coupling characteristics, thereby determining the key dimensional parameters, power-feeding scheme, and electric-field profile of the T-type bunching cavity. Subsequently, the PIC solver was used to further evaluate the bunching performance and its impact on beam transport in the ridgetron accelerator.

The designed T-type buncher has a resonant frequency of 100.03 MHz. Within an input power range of 120–200 W, a 5 ns input beam pulse can be compressed to below 0.6 ns (FWHM), with the energy spread maintained between 22% and 26%. PIC simulation results indicate that, at an input power of 140 W and a drift section length of 1630 mm, the inclusion of the buncher reduces the beam loss after the first deflection by approximately 40%. When a 5 ns electron bunch is compressed to 2 ns (non-FWHM), the beam current increases by a factor of approximately 3.13 compared with the injection without the buncher.

These results clearly demonstrate the effectiveness of the buncher in enhancing beam capture efficiency and overall accelerator performance, and provide a valuable reference for further power enhancement in ridge-type accelerators.

Future work will focus on high-power experimental validation of the buncher to further assess its applicability and reliability in high-power ridgetron irradiation systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.L. and Y.Y.; methodology, D.L.; validation, D.L.; resources, Z.Z.; data curation, D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, D.L.; writing—review and editing, D.L.; project administration, Y.Y.; visualization, Y.Y.; funding acquisition, Y.Y.; supervision, Z.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Supported by the China National Nuclear Corporation Centralized R&D Project (FA16000104, Linear Accelerator).

Data Availability Statement

Some of the data in the manuscript will be made available through. request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- IAEA. Industrial Radiation Processing with Electron Beams and X Rays; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2011.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Radioactive Sources: Applications and Alternative Technologies; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Department of Energy. Commercial Potential Evaluation: Cobalt-60 Alternative Equipment; U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- IAEA. Emerging Applications of Radiation Processing; Technical Reports Series No. 1386; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2004.

- Ozer, Z.N. Electron beam irradiation processing for industrial and medical applications. EPJ Web Conf. 2017, 154, 01019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IAEA. Radiation Technologies for the Treatment of Gaseous and Liquid Effluents; Technical Reports Series No. 409; IAEA: Vienna, Austria, 2002.

- Bassaler, J.M.; Etievant, C. Project of a Free Electron Laser in the Far Infrared Using a Rhodotron Accelerator. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. A 1991, 304, 177–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassaler, J.M.; Baudrand, H. Calculation of the Resonance Frequencies of the Rhodotron Cavity Using Green Function. In Proceedings of the EPAC, Berlin, Germany, 24–28 March 1992; pp. 898–900. [Google Scholar]

- Jongen, Y. The Rhodotron: A New 10 MeV, 100 kW, CW Metric Wave Electron Accelerator. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 1993, 79, 865–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayashizaki, N.; Hattori, T.; Odera, M.; Nakayama, K.; Isokawa, K.; Sato, K.; Fujisawa, T. Beam Acceleration Test of the Ridgetron Electron Accelerator. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. B 2002, 188, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Li, C. Improved Design of Ridge Resonant Cavity. At. Energy Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 756–761. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Wu, Q.; Wang, X. Development of Input Coupler for 10 MeV/50 kW Ridgetron Accelerator. At. Energy Sci. Technol. 2021, 55, 555–560. [Google Scholar]

- Kutsaev, S.V. Electron Bunchers for Industrial RF Linear Accelerators: Theory and Design Guide. Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2021, 136, 446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, W.; Pu, D.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y.; Hu, J.; Ding, S. Development of a Subharmonic Prebuncher in High-Current RF Electron Linear Accelerators. High Power Laser Part. Beams 1990, 2, 311–318. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, S.; Zhao, M.; Wang, B. Design and Commissioning of the Subharmonic Cavity Coupler for the 150 MeV Linear Accelerator at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. High Power Laser Part. Beams 2010, 22, 1125–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, S.; Wang, S.; Gu, P. Physical Design of a 571.2 MHz Subharmonic Buncher Cavity. At. Energy Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 385–389. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Cao, D.; Dong, G.; Yang, Z.; Guan, G.; Zhou, W. Cavity Resonant Field Prebuncher. High Power Laser Part. Beams 1997, 9, 321–325. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Guan, X. Physical Design of a Double-Drift Harmonic Buncher. At. Energy Sci. Technol. 1998, 32, 152–157. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, F. Improvement of a Single-Drift Bunching Cavity. At. Energy Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 493–496. [Google Scholar]

- Pei, S.; Wang, S.; Gu, P.; Geng, Z. Structural Optimization Design of 142.8 MHz Subharmonic Bunching Cavity. High Power Laser Part. Beams 2004, 16, 795–799. [Google Scholar]

- An, S.; Zhang, T.; Wu, L.; Ji, B.; Zhong, J.; Yao, H.; Guan, F.; Wei, S.; Jia, X.; Yang, J. Design and Calculation of the Buncher in the Beam Pulsing System. Annu. Rep. China Inst. At. Energy 2006, 1, 61–62. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qin, C.; Yang, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, C.; Lü, Y.; Li, L.; Yan, J.; Wang, X.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, G. Development of a proton beam buncher. Rev. Nucl. Phys. 2025, 42, 54–60. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of ridge accelerator system.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of ridge accelerator system.

Figure 2.

Principle of buncher.

Figure 2.

Principle of buncher.

Figure 3.

Equivalent circuit.

Figure 3.

Equivalent circuit.

Figure 4.

T-shaped cavity structure.

Figure 4.

T-shaped cavity structure.

Figure 5.

Key geometric parameter labeling of the cavity. 2*Ri indicates the diameter (twice the radius).

Figure 5.

Key geometric parameter labeling of the cavity. 2*Ri indicates the diameter (twice the radius).

Figure 6.

T-beamer double gap structure schematic diagram.

Figure 6.

T-beamer double gap structure schematic diagram.

Figure 7.

Position diagram of maximum surface electric field. Red indicates high electric field values, and green indicates low electric field values.

Figure 7.

Position diagram of maximum surface electric field. Red indicates high electric field values, and green indicates low electric field values.

Figure 8.

Quality factor, the maximum surface electric field with the acceleration gap change diagram.

Figure 8.

Quality factor, the maximum surface electric field with the acceleration gap change diagram.

Figure 9.

Computational model of the buncher cavity and coupler.

Figure 9.

Computational model of the buncher cavity and coupler.

Figure 10.

S1,1 simulation outcomes.

Figure 10.

S1,1 simulation outcomes.

Figure 11.

Electric field diagram of the buncher.

Figure 11.

Electric field diagram of the buncher.

Figure 12.

S-parameter Smith chart of the buncher.

Figure 12.

S-parameter Smith chart of the buncher.

Figure 13.

The adjustable frequency range diagram of the tuner.

Figure 13.

The adjustable frequency range diagram of the tuner.

Figure 14.

(a) 5 ns electron bunches emitted by electron gun (b) bunched electron bunches.

Figure 14.

(a) 5 ns electron bunches emitted by electron gun (b) bunched electron bunches.

Figure 15.

(a) initial electron beam pulse width (b) electron beam pulse width after bunching at 140 W power.

Figure 15.

(a) initial electron beam pulse width (b) electron beam pulse width after bunching at 140 W power.

Figure 16.

FWHM, energy spread with the injection power change diagram.

Figure 16.

FWHM, energy spread with the injection power change diagram.

Figure 17.

Dependence of drift section length and in-cavity beam loss on the input power.

Figure 17.

Dependence of drift section length and in-cavity beam loss on the input power.

Figure 18.

The whole process of electron bunch modulation and acceleration.

Figure 18.

The whole process of electron bunch modulation and acceleration.

Figure 19.

Beam loss after the first deflection at different injection powers.

Figure 19.

Beam loss after the first deflection at different injection powers.

Figure 20.

The phase mismatch that occurs when the initial pulse width is 5 ns without the buncher.

Figure 20.

The phase mismatch that occurs when the initial pulse width is 5 ns without the buncher.

Figure 21.

Beam current comparison with and without the buncher for an initial pulse width of 5 ns.

Figure 21.

Beam current comparison with and without the buncher for an initial pulse width of 5 ns.

Table 1.

The final design parameters of the cavity.

Table 1.

The final design parameters of the cavity.

| Cavity Parameter | Value |

|---|

| G/mm | 20 |

| C/mm | 548 |

| H/mm | 372 |

| RC/mm | 78 |

| Ri/mm | 37 |

| f/MHz | 100.065 |

| Q | 5295 |

| Tuning mouth distance from the center distance/mm | 150 |

| Tuning port radius | 17.5 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).