4.1. Machine Learning Model Selection Results

This section presents a comprehensive analysis of the results obtained from the systematic application of the machine learning methods described previously. For each method, hyperparameter optimization yielded a distinct set of models, enabling a thorough evaluation of their performance. We provide a detailed discussion of the optimal results for each algorithm individually, followed by a comparative analysis to assess their relative performance and effectiveness.

To provide additional practical value, we report the computational burden associated with the hyperparameter grid and model training process. Across all experiments, the relative runtime order was as follows: kNN was the fastest method, followed by Decision Trees, which also completed training quickly. XGBoost and LightGBM required moderate computation time, while Neural Networks exhibited moderate to high runtime depending on the number of layers and complexity of the architecture. Random Forest showed the highest overall computational cost due to the large number of trees and repeated cross-validation. These observations help practitioners understand the trade-off between predictive accuracy and computational resources when selecting models for large-scale EMF prediction tasks.

Neural Networks (NN)

We implemented a large-scale evaluation of neural network architectures, systematically varying hyperparameters related to topology (number of layers L), activation functions (), and optimization settings (learning rate , optimizer choice). The best-performing configurations achieved mean RMSE values between 0.909277 and 0.911257, with differences lying within the error margin, indicating comparable accuracy and robustness across cross-validation folds. The numerical optimal model consisted of two hidden layers with ReLU activation, Adam optimizer, and , yielding a mean RMSE of 0.909277 (). Although ReLU combined with high learning rates produced competitive results, these models exhibited lower reproducibility.

In contrast, networks with logistic or tanh activation functions, compact architectures (2–20 hidden units), and moderate learning rates (

, Adam) consistently achieved near-optimal accuracy while maintaining greater stability. These models dominated the top-ranked results, underscoring their reliability and efficiency in capturing nonlinear patterns in electric field strength prediction, as we can see in the summarized ranking

Table 3. Conversely, identity activations and excessively large networks often diverged, producing inflated errors and instability, highlighting their unsuitability. Overall, compact architectures with logistic or tanh activations and moderate learning rates represent the most robust and practical solutions for deployment, while further statistical paired tests on fold-level predictions are required to claim that any of the best configurations is better than another.

k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN)

The evaluation of the k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) models revealed a consistent trend of better results by the use of distance-based weighting schemes (inverse-distance) over uniform weighting (equal weights), regardless of the number of neighbors or Minkowski distance parameter

p. Specifically, the five best-performing configurations, as measured by mean RMSE, were very tightly grouped in the interval [0.623153, 0.627706], with the best of them

achieving RMSE 0.623153 (SD 0.042993), closely followed by the second best

with RMSE 0.623335 (SD 0.043059), and the rest of the top 5 as clearly depicted in summarized

Table 4, accompanied with their corresponding CIs.

The above results indicate that medium neighborhood sizes (–25) combined with inverse distance weighting achieved an optimal balance between local sensitivity and generalization and thus yielded the lowest prediction errors. In contrast, uniform weighting schemes systematically underperformed, with RMSE values increasing substantially as k grew larger, underscoring the importance of accounting for proximity when aggregating neighbor contributions, especially for spatial applications like EMF predictions, because measurements are spatially autocorrelated and nearer sensors are more informative. Summing up, distance-weighted kNN models with moderate neighborhood sizes (–25) yielded the most robust performance, with only minor RMSE variation across top settings. Moreover, the slightly best results at may indicate that the feature space geometry could be best captured by a non-integer continuous Minkowski p norm.

Decision Trees (DT)

The evaluation of Decision Tree models demonstrated that adjustments to the hyperparameter, which controls the minimum number (or fraction) of samples required to split an internal node, produced a systematic bias–variance trade-off consistent with theoretical expectations. Specifically, very small thresholds (e.g., ) yielded the weakest performance (mean RMSE = 0.869772, SD = 0.075755), indicating overfitting and unstable predictions across folds. Increasing the threshold clearly improved generalization, with the best performance observed at (mean RMSE = 0.812665, SD = 0.060873). However, further increasing the threshold (e.g., ) slightly degraded the performance (mean RMSE = 0.817838, SD = 0.061485), suggesting underfitting as the model became overly constrained.

The above results indicate that moderate complexity constraints, specifically a splitting threshold around 20, yielded the best performing configuration and provide the most favorable balance between flexibility and stability, clearly indicated in the summarized

Table 5, by the lower mean RMSE score. Overall, this configuration achieved to reduce the variance without sacrificing his predictive accuracy, yielding the most robust results between DTs models for EMF strength prediction in urban environments.

Random Forest (RF)

The evaluation of Random Forest models indicates that the squared-error and Friedman MSE criteria consistently yielded superior performance across all ensemble sizes. The best configuration with 200 estimators, squared-error splitting and maximum depth of 10, achieved the lowest mean RMSE of 0.757916 (SD = 0.066344). In contrast, the absolute-error criterion showed considerably weaker results (mean RMSE ≈ 0.817), underscoring its unsuitability for accurate EMF estimation. Moreover, by increasing the number of estimators from 50 to 200 we obtained marginal improvements, with refinements of less than 0.002 in mean RMSE, improvements that, although consistent, were small relative to cross-validation variability, as we can see in the summarized top 5 ranking

Table 6.

Overall, performance differences among the top Random Forest settings (squared-error and Friedman MSE with 100–200 trees) were minor and largely within overlapping confidence intervals, suggesting further statistical testing (e.g., paired t-tests) to confirm notable statistical significance. From a computational perspective, ensembles of ∼100 trees appear to provide an optimal trade-off between predictive accuracy and efficiency, while 200 trees offer slightly greater stability at higher computational cost.

LightGBM

The evaluation of LightGBM models across a broad hyperparameter space revealed a consistent pattern in predictive accuracy, with the lowest errors obtained from larger tree structures combined with sufficient gradient boosting iterations. The best performing configuration with Num_Leaves = 100, N_Estimators = 500, Learning_Rate = 0.1, and Max_Depth = 20 achieved a mean RMSE of 0.716689 (SD = 0.053689), indicating both high accuracy and stable generalization across all folds. Comparable performance was observed for slightly less complex settings, such as N_Estimators = 300 or Learning_Rate = 0.05, which yielded mean RMSE values in the range 0.720822–0.722759, as summarized in the

Table 7.

The above results confirm that LightGBM benefits from deeper and broader trees when combined with sufficient gradient boosting rounds, particularly under moderate learning rates that balance convergence speed and generalization. However, deeper architectures and larger ensembles increase computational demands and may increase overfitting risks if the available data are limited or noisy. Overall, while the results show that more complex configurations yield superior accuracy in the estimation of EMF, the marginal gains diminish beyond a certain complexity, e.g., differences between 300 and 500 estimators are modest, a fact that must taken under consideration in applications where the computational resources are limited. So, from a practical standpoint, configurations with 100 leaves, 300 estimators, and depth 20 may offer a near-optimal trade-off between accuracy and efficiency.

XGBoost

The evaluation of XGBoost models across varied hyperparameter configurations revealed that the strongest predictive performance was consistently obtained with deep trees (Max_Depth = 20) combined with stronger L2 regularization parameters (i.e., Lambda_option

= 10). Specifically, the best configuration, with

= 10, N_Estimators = 100 and Learning_Rate

= 0.05, achieved the lowest mean RMSE = 0.711201 (SD = 0.059282). Comparable results were observed with lower learning rates (

= 0.01) but considerably larger ensembles (300–500 estimators), as summarized in

Table 8.

The above results highlight two effective strategic approaches that can be followed: (i) moderate learning rates ( = 0.05) with fewer boosting rounds (N_Estimators ≈ 100), which reduce computational cost while maintaining accuracy, and (ii) smaller learning rates ( = 0.01) with considerably larger ensembles (300–500 estimators), which yield similar accuracy but at higher computational expense. The consistent presence of strong L2 regularization ( = 5–10) among the top-performing models, suggests that high-capacity XGBoost trees tend to overfit in that specific settings unless they are adequately penalized and thus underscoring its critical role of regularization in mitigating overfitting in high-capacity deep trees.

Overall, the best-performing configurations balance well the ability to capture complex spatial–environmental dependencies in the EMF data combined with stable generalization across folds. However, the narrow differences among the top results, coupled with overlapping confidence intervals, suggest that observed improvements are incremental and may depend on the specific dataset partitioning. From a practical standpoint, the configuration with = 10, N_Estimators = 100 and = 0.05 offers an effective trade-off between accuracy and efficiency, while low–learning rate settings may be advantageous in occasions when computational resources are plentiful and marginal gains in stability are important.

Comparative Analysis Machine Learning Models

The comparative analysis of the six machine learning models Neural Networks (NN), k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Decision Trees (DTs), Random Forest (RF), LightGBM and XGBoost demonstrates notable differences in their predictive accuracy, variability, and robustness. Specifically, models’ evaluation (The models were ranked according to their mean RMSE values, reported with six-decimal precision.) was conducted using the root mean squared error (RMSE) as the primary performance metric, complemented by variability measures including the standard deviation of RMSE (SD RMSE) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

The best-performing model was kNN, achieving a mean RMSE of 0.623153 (SD = 0.042993; 95% CI: [0.611236, 0.635070]). This result indicates a strong predictive accuracy and comparatively low uncertainty, highlighting kNN’s capacity to capture local structures within the dataset. The second-best performer was XGBoost, with a mean RMSE of 0.711201 (SD = 0.059282; 95% CI: [0.694769, 0.727633]), followed closely by LightGBM at 0.716689 (SD = 0.053689; 95% CI: [0.701807, 0.731571]). Both gradient boosting methods demonstrated competitive performance with consistent generalization, benefiting from their ensemble-based optimization against weak learners (single learners, e.g., Decision Trees), aligns with theoretical expectations that ensemble and boosting methods reduce variance and bias through aggregation.

Random Forest obtained a mean RMSE of 0.757916 (SD = 0.066344; 95% CI: [0.739527, 0.776306]), ranking fourth. It is worth mentioning that while Random Forest outperformed simpler models in terms of variance reduction, its predictive accuracy was inferior compared to boosting methods and kNN. Furthermore, the Decision Tree ML approach, a baseline of tree methods, yielded a mean RMSE of 0.812665 (SD = 0.060873; 95% CI: [0.795792, 0.829538]), underlining the limitations of single-tree learners, which are prone to high variance and overfitting. Finally, the Neural Networks configuration tested achieved the weakest performance, with a mean RMSE of 0.909277 (SD = 0.070638; 95% CI: [0.889697, 0.928857]). This result suggests that the chosen hyperparameter settings and network depth were not well-suited to the dataset, leading to suboptimal convergence, as clearly depicted in

Figure 3.

In summary, the results establish a clear ranking order of predictive EMF performance as follows:

k-Nearest Neighbors: mean RMSE = 0.623153, SD = 0.042993, CI = [0.611236, 0.635070]

XGBoost: mean RMSE = 0.711201, SD = 0.059282, CI = [0.694769, 0.727633]

LightGBM: mean RMSE = 0.716689, SD = 0.053689, CI = [0.701807, 0.731571]

Random Forest: mean RMSE = 0.757916, SD = 0.066344, CI = [0.739527, 0.776306]

Decision Tree: mean RMSE = 0.812665, SD = 0.060873, CI = [0.795792, 0.829538]

Neural Networks: mean RMSE = 0.909277, SD = 0.070638, CI = [0.889697, 0.928857]

The superior accuracy of kNN highlights the effectiveness of instance-based learning for this specific EMF prediction task, though its computational efficiency may pose limitations for very large datasets. On the other hand, more novel gradient boosting approaches, such as XGBoost and LightGBM, provide a strong trade-off between predictive performance and scalability, while Random Forest remains a robust yet slightly less accurate alternative. Conversely, single-tree and neural architectures require careful hyperparameter refinement-calibration in order to approach the performance of ensemble-based methods. Summing up, these findings suggest that future work should prioritize boosting models or optimized kNN schemes, while indicating the potential of exploring hybrid approaches that integrate the effectiveness of instance-based learning with the interpretability of decision trees and the accuracy of ensemble learning methods.

Figure 4 showcase a comparative analysis of RMSEs distributions across all ML modes. Also, the

Figure 5 shows how the predicted values are mapped over the area of interest.

4.2. XAI Results and Explanations

4.2.1. SHAP

The SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) framework offers a unified, model-agnostic approach for interpreting complex machine learning predictions by quantifying the marginal contribution of each feature to the model’s output. In particular, SHAP decomposes a model’s prediction into additive feature attributions, ensuring both local accuracy and global consistency across instances. The global perspective aggregates feature contributions across all samples to identify the dominant predictors driving EMF variability at the population level. Conversely, the local perspective focuses on individual predictions, explaining how specific feature interactions influence the model’s output for a given observation.

Specifically, in the context of electromagnetic field (EMF) strength prediction, the SHAP dual approach of the above two perspectives facilitate a comprehensive understanding of both the overall model behavior and case-specific explanatory patterns and so, enables a detailed examination of how spatial, demographic, and environmental variables-features influence model outputs, thereby providing transparent and theoretically grounded insights into the underlying decision mechanisms of the employed ML algorithms.

In the subsequent subsections, SHAP results are presented for the top-performing ML models, including k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) and XGBoost. The global SHAP summary plots (beeswarm plots) illustrate the average magnitude and direction of each feature’s contribution to EMF prediction, while local explanations (waterfall plots) reveal instance-specific deviations and contextual dependencies. This dual analysis enables the identification of consistent explanatory trends across models and environments, forming a robust interpretive basis for assessing predictive performance and environmental significance.

kNN SHAP Analysis

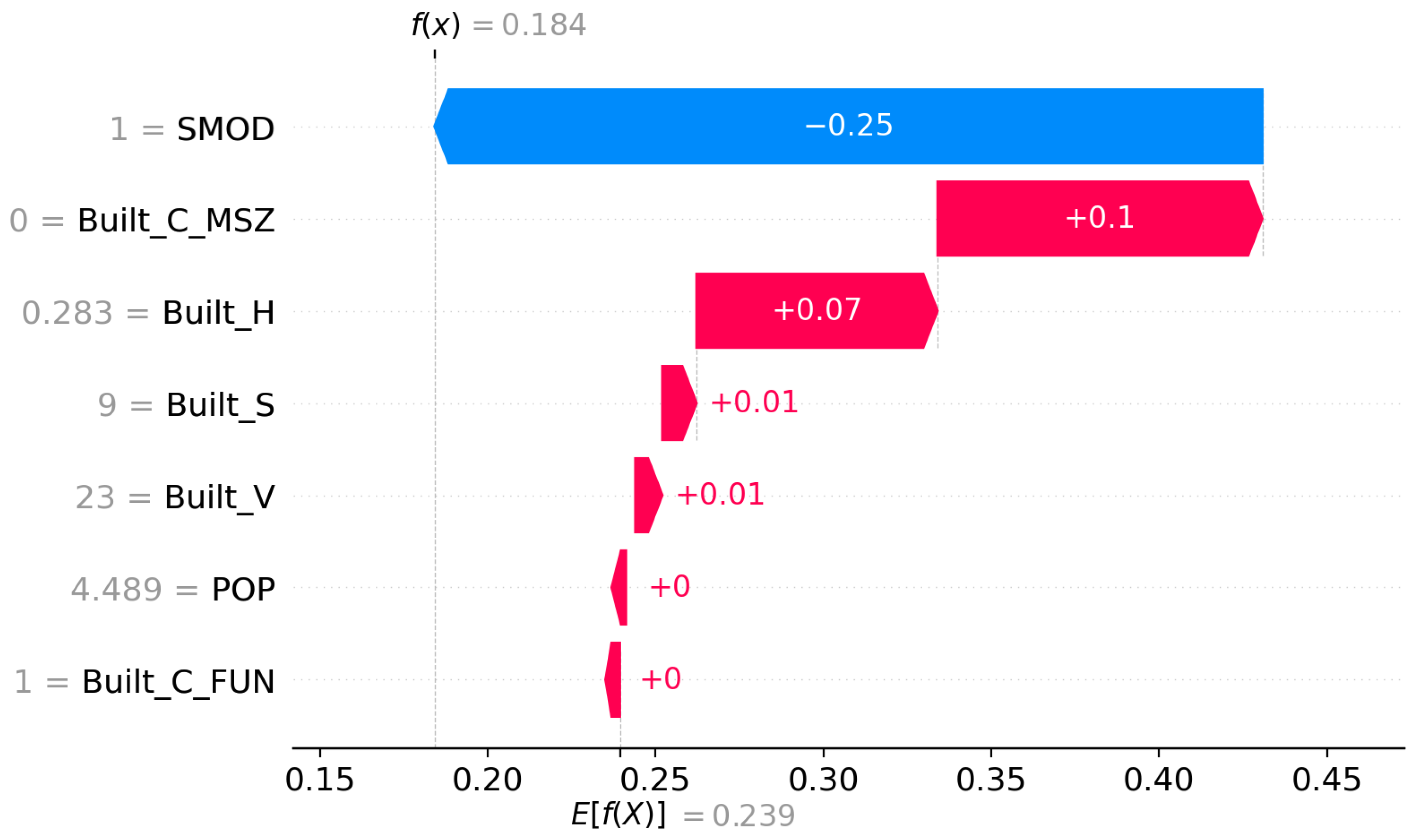

Figure 6 (beeswarm plot) visualizes both the magnitude and directionality of each feature’s impact, whereas

Figure 7 (waterfall plot) illustrates the additive effect of the most influential variables for a representative prediction instance. The signed mean SHAP values reflect whether a feature predominantly increases or decreases the predicted electromagnetic field (EMF) strength, while the absolute mean SHAP values capture the overall influence magnitude, independent of direction.

Among all predictors, SMOD (Degree of Urbanisation) emerges as the most influential variable (

Figure 7), displaying the strongest negative SHAP contribution on average. This suggests that areas classified with higher urbanisation degrees correspond to a relative decrease in predicted EMF strength within the kNN model’s local decision structure, possibly due to attenuation effects or signal diffusion associated with denser morphological configurations. Conversely, Built_C_MSZ, representing the Morphological Settlement Zone classification, exerts a positive influence, indicating that denser or morphologically structured settlements tend to elevate EMF predictions, which likely reflects a potential increased infrastructure and emitter density in such zones.

The features Built_H (average building height), Built_S (built-up surface), and Built_V (built-up volume) also show moderate positive contributions, emphasizing the importance of vertical and horizontal development intensity in shaping EMF propagation, whereas the feature variable POP (population density) appears to have a relatively minor but still meaningful impact, consistent with the idea that population distribution serves as an indirect indication for built infrastructure. Finally, Built_C_FUN (residential vs. non-residential functional classification) demonstrates minimal impact, suggesting that functional land-use type alone does not strongly determine EMF variations once structural characteristics are accounted for.

Overall, the SHAP-based interpretability analysis reveals that urban morphology and spatial structural variables, particularly the degree of urbanisation, settlement delineation, and built environment metrics, constitute the most decisive factors in the kNN model’s EMF strength predictions. This evidence underscores the model’s sensitivity to fine-grained geospatial geometric attributes rather than purely demographic factors. From a methodological standpoint, SHAP confirms that the kNN model captures locally heterogeneous spatial geometrical dependencies, reinforcing the value of spatially explicit variables in EMF modeling frameworks.

XGBoost SHAP Analysis

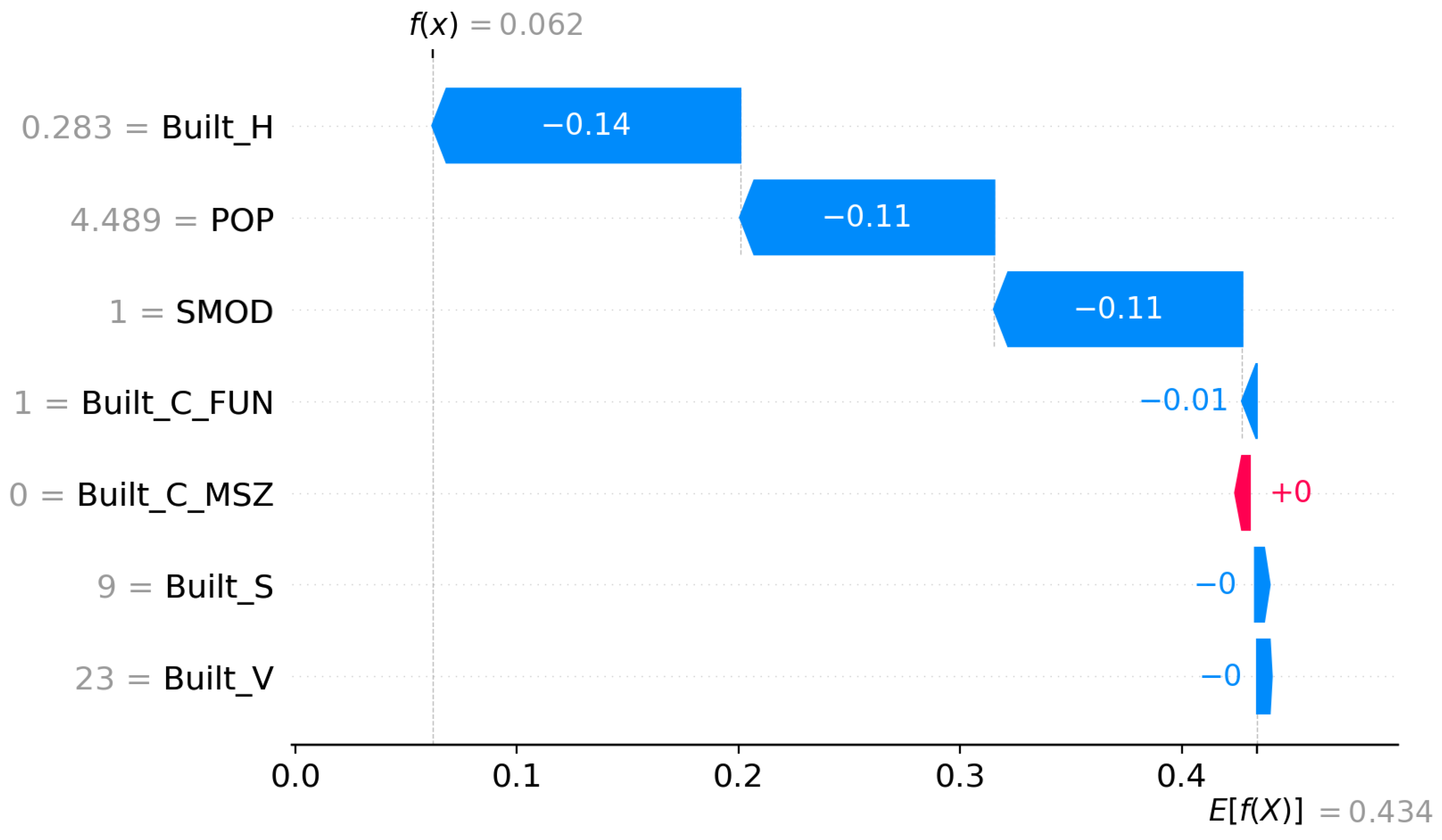

The summary of the XGBoost SHAP analysis as depicted in (beeswarm) plot in

Figure 8 visualizes the distribution of SHAP values across all test samples, thereby quantifying both the magnitude and direction of each feature’s effect on the predicted EMF intensity. Meanwhile, the waterfall plot in

Figure 9 illustrates a single prediction instance, showing how the cumulative contributions of features shift the prediction from the baseline expectation

to the final model output

. The signed mean SHAP values reveal whether a feature tends to increase or decrease the predicted EMF, while the absolute mean SHAP values highlight its overall importance in shaping the model output.

Among the examined predictors, Built_H (building height), POP (population density), and SMOD (degree of urbanisation) emerge as the most influential variables, as clearly illustrated in

Figure 9, in determining the model’s predictions. The SHAP values indicate that higher building heights and higher population densities generally lead to a decrease in predicted EMF levels, as shown by the negative SHAP contributions for these variables. This pattern can be attributed to the signal attenuation and scattering effects introduced by taller structures and densely populated urban cores, which can obstruct direct line-of-sight propagation. Similarly, SMOD, representing the urbanisation level, exerts a negative influence, suggesting that highly urbanized zones, often characterized by dense building clusters and infrastructure, tend to experience lower EMF intensities at ground level due to increased multipath fading and signal absorption.

On the other hand, features related to morphological classification, such as the variables Built_C_MSZ (Morphological Settlement Zone) and Built_C_FUN (functional classification of the built environment), exhibit comparatively smaller yet non-negligible impacts. The weak positive or near-zero contributions of these variables suggest that while the categorical partitioning of urban morphology provides structural context, it alone does not substantially modify EMF predictions beyond the physical characteristics that already captured by building height and surface data. Similarly, Built_S (built-up surface) and Built_V (built-up volume) show marginal contributions, reinforcing the idea that geometric and structural aspects of the urban fabric, although interacting with EMF propagation mechanisms, still remain secondary to the building height and population-related attenuation factors.

Overall, the SHAP analysis confirms that structural and demographic urban characteristics jointly govern EMF distribution, with XGBoost effectively capturing the nonlinear dependencies between physical urban morphology and exposure levels. The model assigns higher importance to attenuative factors (e.g., height, density) rather than purely spatial classifications, aligning well with established radio propagation theory. From an interpretability standpoint, these results validate the physical plausibility of the XGBoost model’s learning behavior, where the identified feature effects are consistent with empirical observations in urban electromagnetic environments, thereby enhancing confidence in its predictive transparency and reliability.

SHAP Discussion

Comparative dual SHAP interpretations reveal that the k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) and XGBoost models achieve similar predictive accuracy but through fundamentally different explanatory mechanisms. The kNN model exhibits heightened sensitivity to spatial and morphological-topological structure, relying on neighborhood similarity in the feature space to infer electromagnetic field (EMF) strength. Its predictions are primarily influenced by local contextual features, particularly morphological indicators such as urban form and settlement classification, reflecting the model’s instance-based reasoning and dependence on spatial geometric distance-based proximity.

In contrast, the XGBoost model emphasize on physical attenuation dynamics and quantitative urban metrics, capturing complex nonlinear interactions and cumulative effects among structural and demographic variables. This behavior aligns more closely with theoretical signal propagation principles, as the model generalizes more effectively across heterogeneous urban settings by learning hierarchical relationships rather than specific localized associations.

Together, these complementary interpretability profiles demonstrate that kNN encodes better upon spatial similarity while XGBoost learns more effective parametric attenuation functions, two distinct but yet potential synergistic approaches to modeling EMF variability. Integrating both local (kNN-driven) and global (XGBoost-driven) interpretability perspectives yields a more comprehensive and physically consistent understanding of EMF behavior in urban environments, thereby advancing transparent, data-driven methodologies for environmental monitoring and urban planning.

4.2.2. LIME

The LIME (Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations) framework provides a complementary perspective to SHAP by focusing explicitly on local interpretability—that is, understanding the reasoning behind individual model predictions. Unlike SHAP, which derives globally consistent feature attributions based on cooperative game theory, LIME approximates the complex behavior of a trained model in the vicinity of a specific instance by fitting a locally linear alternative substitute model. This approximation allows for the identification of the most influential features contributing to a given prediction, thereby offering interpretable, human-readable insights into the local decision boundaries of non-linear models.

Specifically, in the context of electromagnetic field (EMF) strength prediction, LIME facilitates the examination of localized environmental, demographic, and infrastructural conditions that drive model predictions for specific spatial locations. This approach is particularly valuable for identifying context-sensitive deviations that may not be visible in more global XAI approaches like SHAP. By combining LIME’s fine-grained local analysis with SHAP’s globally consistent attributions, a comprehensive interpretability framework is achieved that can support both the validation of model behavior and the transparent communication of EMF prediction results for scientific and regulatory purposes. In correspondence to SHAP analysis, the following subsections present the LIME results for the top-performing ML models, k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) and XGBoost.

kNN LIME Analysis

Consecutive to the SHAP-based interpretability analysis, Local Interpretable Model-Agnostic Explanations (LIME) was employed in order to complement and examine feature contributions for the k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN) model. LIME was applied in a global aggregation framework, wherein instance-level explanations were averaged across the test set to obtain both absolute mean weights

Figure 10 (indicating importance magnitude irrespective of direction) and signed mean weights

Figure 11 (denoting whether features systematically increase or decrease EMF predictions). This dual representation provides a richer interpretability perspective, capturing the stability, strength, and polarity of each predictor’s influence on the urban electromagnetic field (EMF) estimations.

The LIME absolute mean weights analysis profile highlights Built_H (building height), SMOD (degree of urbanization), and Built_C_FUN (urban functional classification) as dominant drivers of kNN predictions, followed closely by POP (population density) and Built_C_MSZ (morphological settlement zoning), which collectively suggest that both vertical density and urban planning topology are central determinants in EMF variability. Built form intensity feature variables such as, Built_V (volume) and Built_S (surface area), exhibit smaller but nontrivial contributions, reflecting their secondary role in shaping propagation environments. Overall, the absolute LIME map reinforces the hypothesis that the kNN model relies primarily on local morphological and socio-spatial gradients, consistent with its distance-based learning nature.

The signed LIME contributions (

Figure 11) reveal coherent directional patterns. Higher values of Built_H, POP, and SMOD tend to increase EMF levels, consistent with urban densification leading to heightened wireless infrastructure density and reflective interference effects. In contrast, certain categories of Built_C_MSZ and low-rise built environments exhibit negative directional effects, suggesting attenuation or less intensive radiative environments in suburban or semi-urban contexts. The consistent polarity of Built_H and SMOD across most instances underscores their robust explanatory power in shaping EMF exposure gradients, while the mixed-sign behavior of built-form intensity variables (Built_S and Built_V) reflects context-dependent effects, likely driven by variations in infrastructure placement, open-space fragmentation, and various micro-propagation phenomena. Collectively, the LIME interpretations confirm the spatially-adaptive and locally sensitive nature of kNN, which leverages micro-scale morphological attributes to interpolate EMF levels.

XGBoost LIME Analysis

LIME-based interpretability analysis was performed in order to elucidate how the XGBoost model leverages geospatial and morphological urban indicators to predict electromagnetic field (EMF) levels. The global mean absolute LIME weights (

Figure 12) reveal that Built_V (built-up volume) and Built_H (building height) emerge as the most influential spatial predictors, followed closely by POP (population density) and SMOD (degree of urbanisation). This dominance indicates that three-dimensional urban morphology and population intensity act as primary determinants shaping EMF variability. The importance of Built_V and Built_H implies a strong association between vertical structural complexity and electromagnetic propagation dynamics, aligning well with radiofrequency propagation theory wherein higher and denser built forms induce multipath effects, signal obstruction, and power variations. Similarly, the prominence of POP and SMOD underscores that densely populated urban cores, which tend to exhibit intensive telecommunication activity and infrastructure concentration, drive higher EMF exposure levels.

The signed LIME weights (

Figure 13) provide insight into directionality. SMOD, POP, and Built_H predominantly exhibit positive signed effects, suggesting that higher values of these features consistently increase model predictions—i.e., contribute to elevated EMF intensity. In contrast, Built_V demonstrates a mixed effect profile: while highly ranked in absolute magnitude, its signed values oscillate around zero across spatial samples, indicating heterogeneous influence that varies by urban context. This pattern reflects physical reality, where vertical density may either attenuate or amplify field strength depending on line-of-sight availability, antenna configuration, and propagation pathways. Built_C_MSZ (settlement morphology classification) and Built_C_FUN (functional class of built space) appear less influential overall but still contribute meaningfully to local decision boundaries, particularly in delineating residential vs. non-residential urban fabric, which indirectly governs telecom antenna distribution and usage patterns.

Collectively, the LIME results demonstrate that the XGBoost model learns coherent, physically interpretable associations grounded in urban morphology structure allocation and population density. The convergence of high absolute importance for Built_V, Built_H, POP, and SMOD across diverse local samples reinforces the robustness of these predictors as primary drivers of EMF exposure spatial heterogeneity. The subtle positive/negative balance for some variables highlights the context-dependent nature of RF propagation, where interactions between terrain, built form, and antenna topology produce nonlinear effects. These findings validate the model’s capacity to reflect real-world physical propagation mechanisms while also providing transparent local explanations that support regulatory, environmental, and urban planning applications.

LIME Discussion

The LIME analysis provides complementary insights into the interpretive behavior of the kNN and XGBoost models by examining feature contributions at the individual-prediction level. Similar to the SHAP findings, both models consistently identify key built-environment and demographic variables, particularly Built_H (building height), Built_V (built volume), Built_S (built surface area) and POP (population density), as the most dominant predictors of EMF intensity. This convergence reinforces the central role of vertical urban form structures and population concentration in shaping radio-frequency propagation electrodynamics.

For the kNN model, the largest LIME attribution magnitudes are associated with Built_H, SMOD, and Built_C_FUN, followed by POP and Built_C_MSZ. Signed contributions reveal context-dependent influences, where certain urban morphologies increase EMF strength while others attenuate it depending on local neighborhood topological similarity. This behavior is consistent with kNN’s instance-based learning paradigm, wherein predictions are strongly shaped by the characteristics of proximate observations. As a result, kNN exhibits more spatially heterogeneous and locally sensitive interpretability, making it particularly informative for micro-scale EMF variation in highly diverse urban settings.

In contrast, XGBoost demonstrates a more structured and globally stable feature attribution pattern. Built_V and Built_H dominate the local explanations, with POP and SMOD also contributing consistently across instances. Directional effects for these variables align closely with already establised theoretical expectations: taller and denser urban environments, which often associated with increased antenna density and multipath propagation, exert strong influence on EMF levels. Compared to kNN, XGBoost yields smoother, more coherent interpretive profiles, reflecting its increased capacity to capture more complex nonlinear, system-level interactions rather than purely local distance-based analogies. Overall, LIME confirms that while kNN provides granular, location-specific interpretability, XGBoost delivers more consistent and physically aligned explanations, resulting in two complementary interpretive paradigms for urban EMF analysis. Together, these LIME results demonstrate that combining instance-level, context-sensitive explanations with broader model-based insights yields a more complete and operationally meaningful understanding of EMF prediction behavior, reinforcing the value of localized interpretability for urban exposure assessment and decision-support applications.

4.2.3. Comparative Analysis Explainable AI Models

A comparative analysis evaluation of SHAP and LIME was conducted in order to elucidate the interpretability characteristics of the employed machine learning models and to assess the consistency, stability, and physical plausibility of feature attributions in the context of EMF field prediction. Both frameworks identified urban morphology and demographic intensity as primary drivers of EMF variability, with highly consistent emphasis across models on variables capturing three-dimensional built form and urbanisation. Specifically, Built_H (building height), Built_V (built volume), POP (population density), and SMOD (degree of urbanisation) emerged as dominant predictors under both methods, reinforcing that vertical density, infrastructure concentration, and population-driven network intensity jointly shape radiofrequency propagation in dense urban environments. Secondary variables such as Built_S, Built_C_MSZ, and Built_C_FUN provided additional structural context, though with comparatively weaker influence. This convergence across SHAP and LIME substantiates the physical plausibility of the learned EMF patterns, aligning model interpretability outcomes with underlying electromagnetic propagation theory.

Despite this overarching consistency, SHAP and LIME exhibited complementary interpretive behaviors reflecting their methodological underpinnings. SHAP provided globally stable, additive attributions with clear decomposition of prediction contributions, enabling systematic quantification of global importance patterns while preserving local fidelity. This was particularly evident for XGBoost, where SHAP exposed coherent attenuation patterns associated with increasing building height and population density, alongside structured nonlinear interactions across the urban morphology. LIME, by contrast, emphasized high-resolution local interpretability, capturing spatially varying effects driven by neighborhood-specific morphology—particularly pronounced in kNN, where instance-based reasoning produced heterogeneous but physically meaningful feature impacts tied to local similarity relationships. Thus, while SHAP offered robust and globally consistent explanations suitable for model benchmarking and scientific inference, LIME revealed contextual micro-dynamics valuable for localized environmental assessment and scenario-specific interpretation.

Overall, the comparative analysis demonstrates that SHAP and LIME act as complementary interpretability mechanisms. SHAP excels in establishing global causal consistency and theoretical conformity, whereas LIME enhances granularity in local diagnostic interpretation. The combined deployment of both methods results in a comprehensive transparency framework, enabling robust validation of model behavior, improved credibility of EMF predictions, and enhanced interpretive utility for urban-scale electromagnetic exposure monitoring and decision-support applications.

Table 9 and

Figure 14 summarize the explainability results obtained across SHAP and LIME, where feature importance analysis of kNN and XGBoost ML methods consistently highlight Built_H, Built_V, and population density POP as the primary drivers of EMF field variability, with SMOD providing additional contextual differentiation of urban form topology. These findings confirm that vertical urban morphology and demographic intensity exert the strongest influence on RF propagation patterns, reinforcing the physical plausibility and robustness of the learned predictive relationships. As shown in the newly added

Figure 14, we summarize the feature-importance patterns across kNN and XGBoost models using a heatmap that integrates both SHAP and LIME evaluations. In order to visualize the qualitative feature-importance categories in a unified manner, we encoded each textual level into an ordinal numerical scale as follows:

This mapping enables consistent graphical representation of importance intensity across models and interpretability methods.