A Multi-Mode Oscillation Suppression Strategy for Grid-Connected Inverter Systems Based on Amplitude–Phase Reconstruction

Abstract

1. Introduction

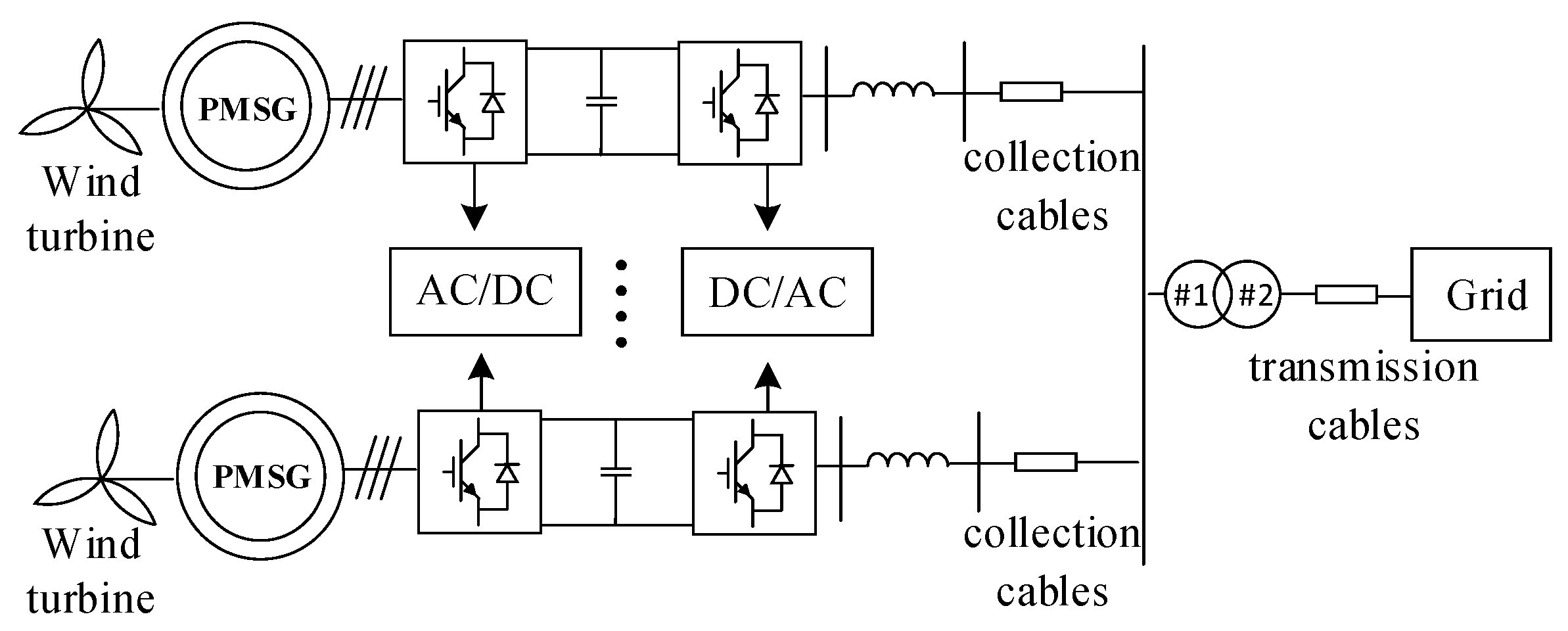

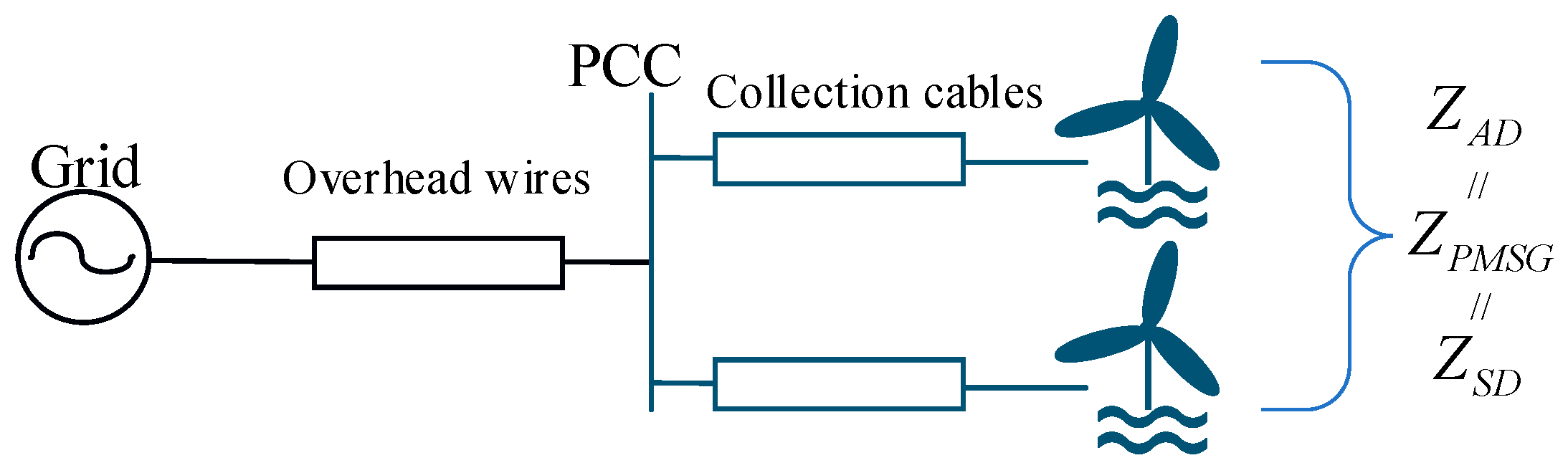

2. Frequency-Domain Impedance Model of Direct-Drive Wind Farms

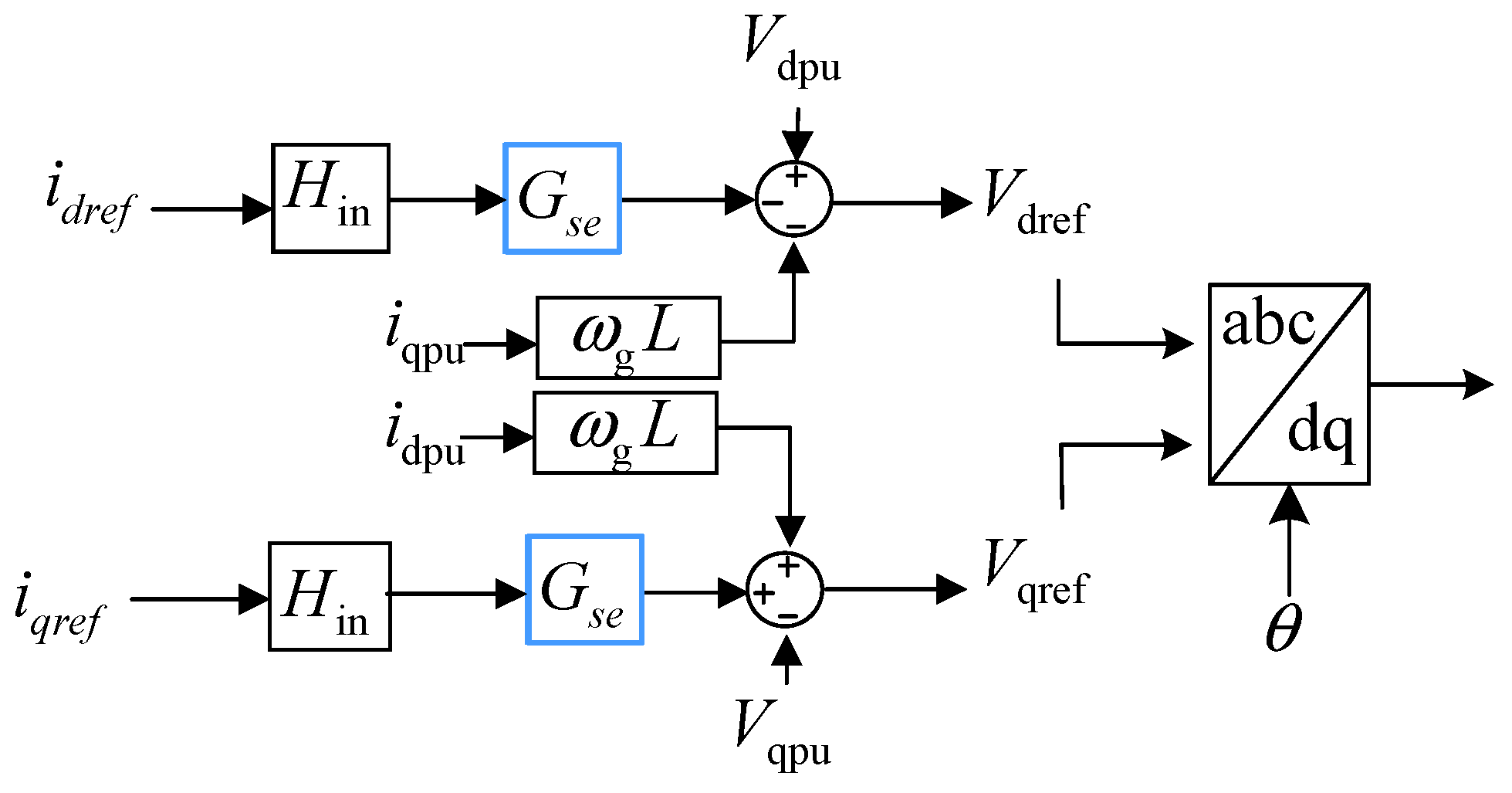

2.1. Direct-Drive Wind Turbine Impedance Model Based on Frequency-Domain Small-Signal Disturbance Method

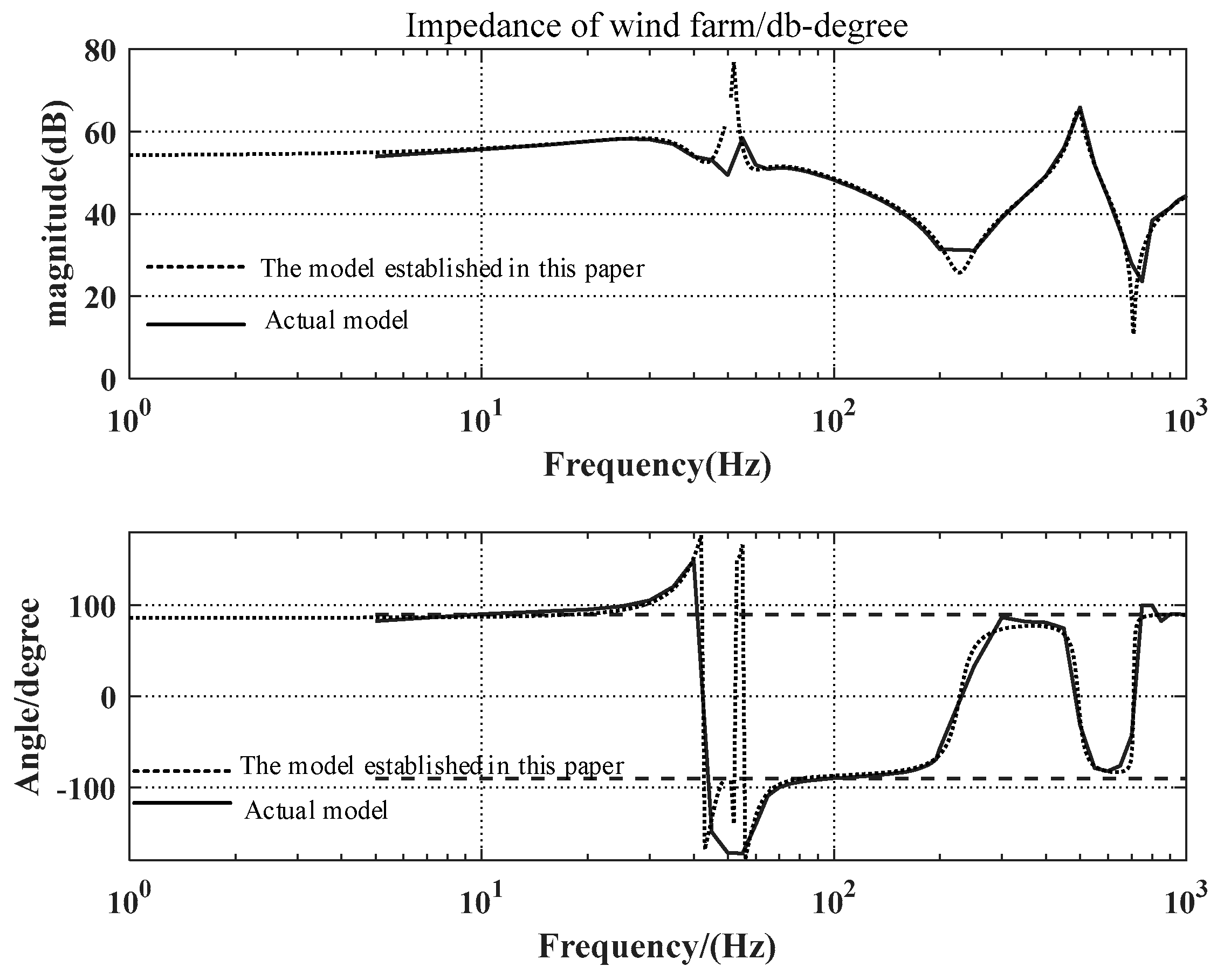

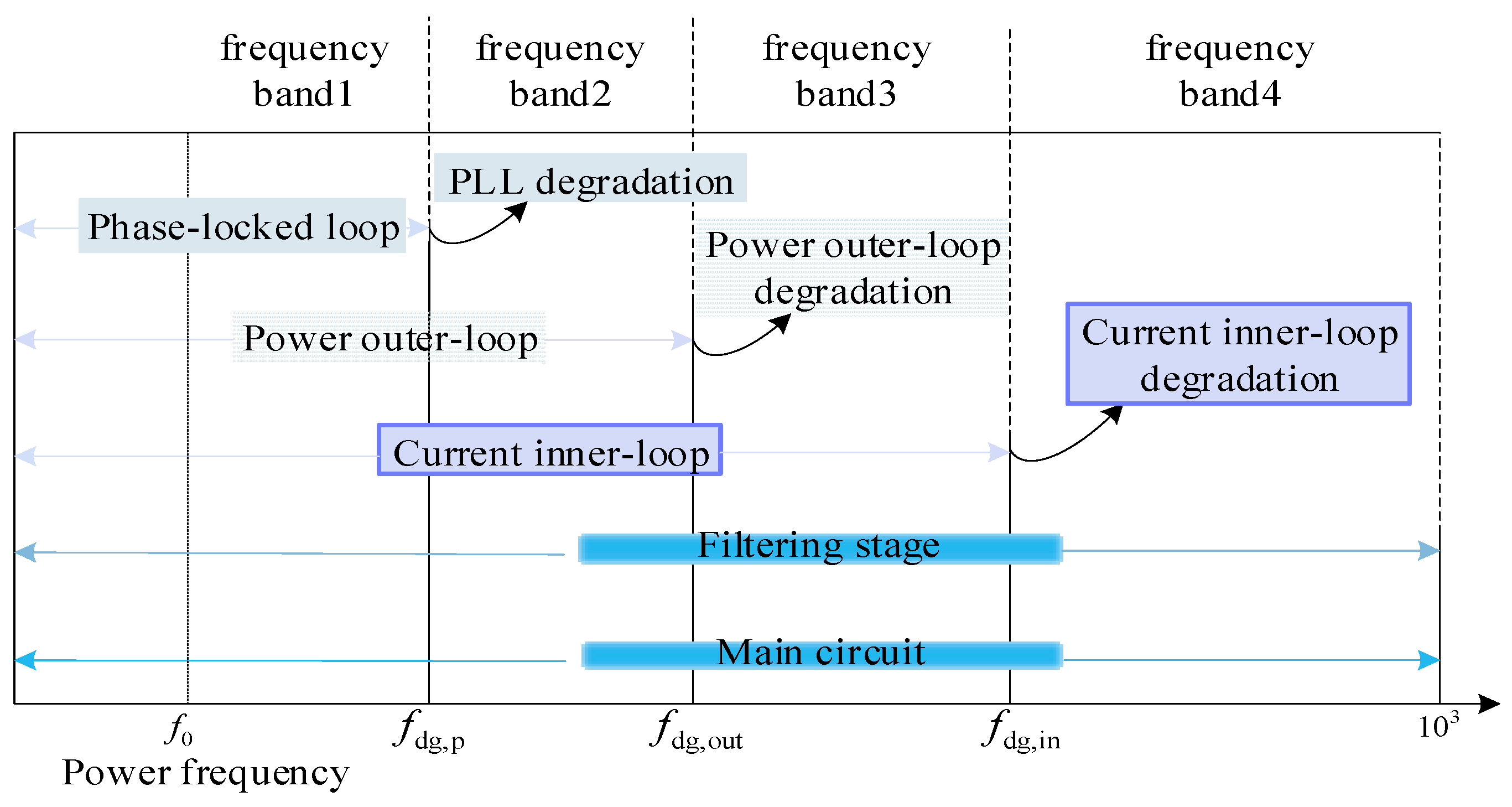

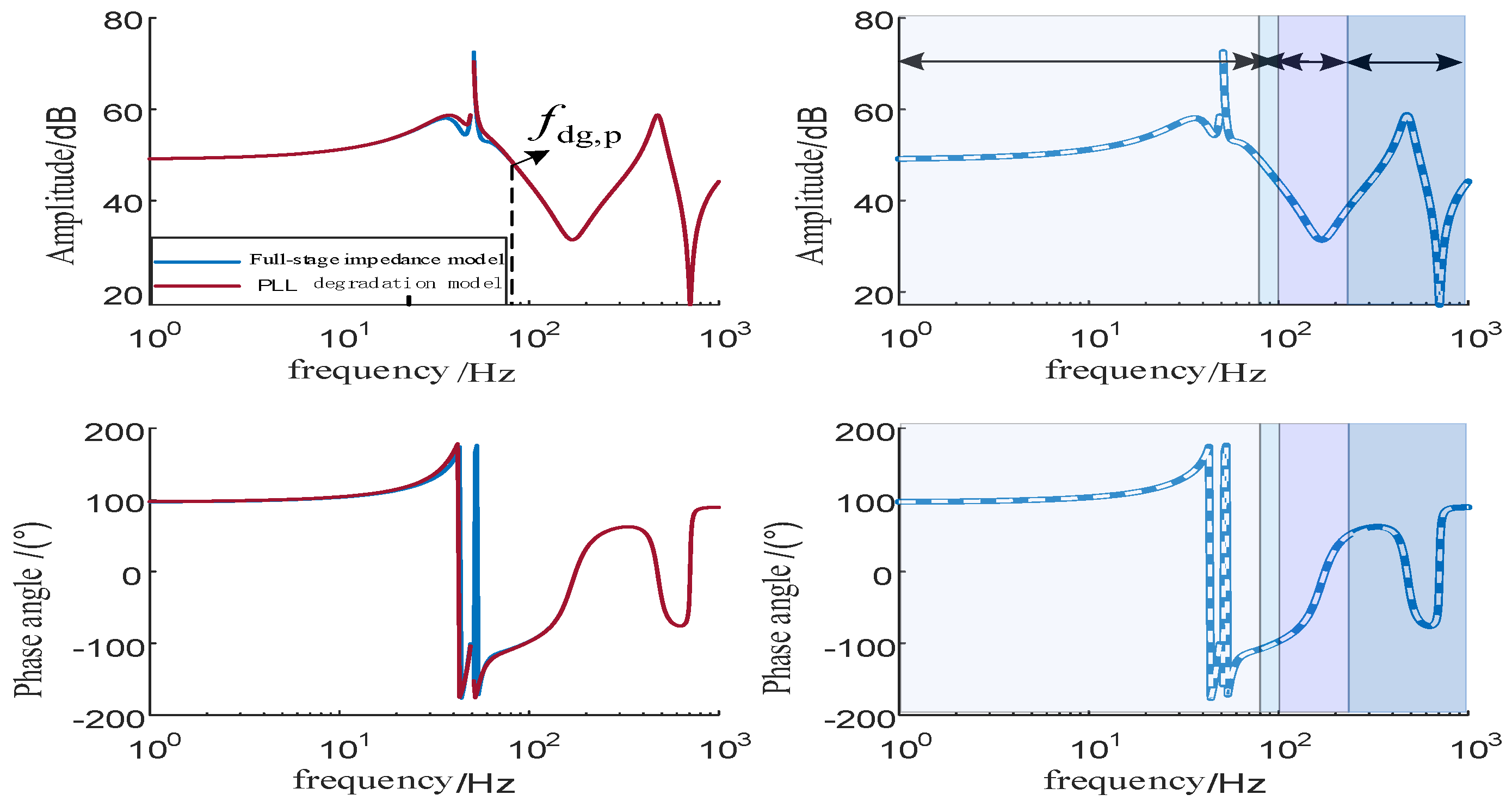

2.2. Dynamic Order Reduction Method for PMSG Frequency-Domain Impedance

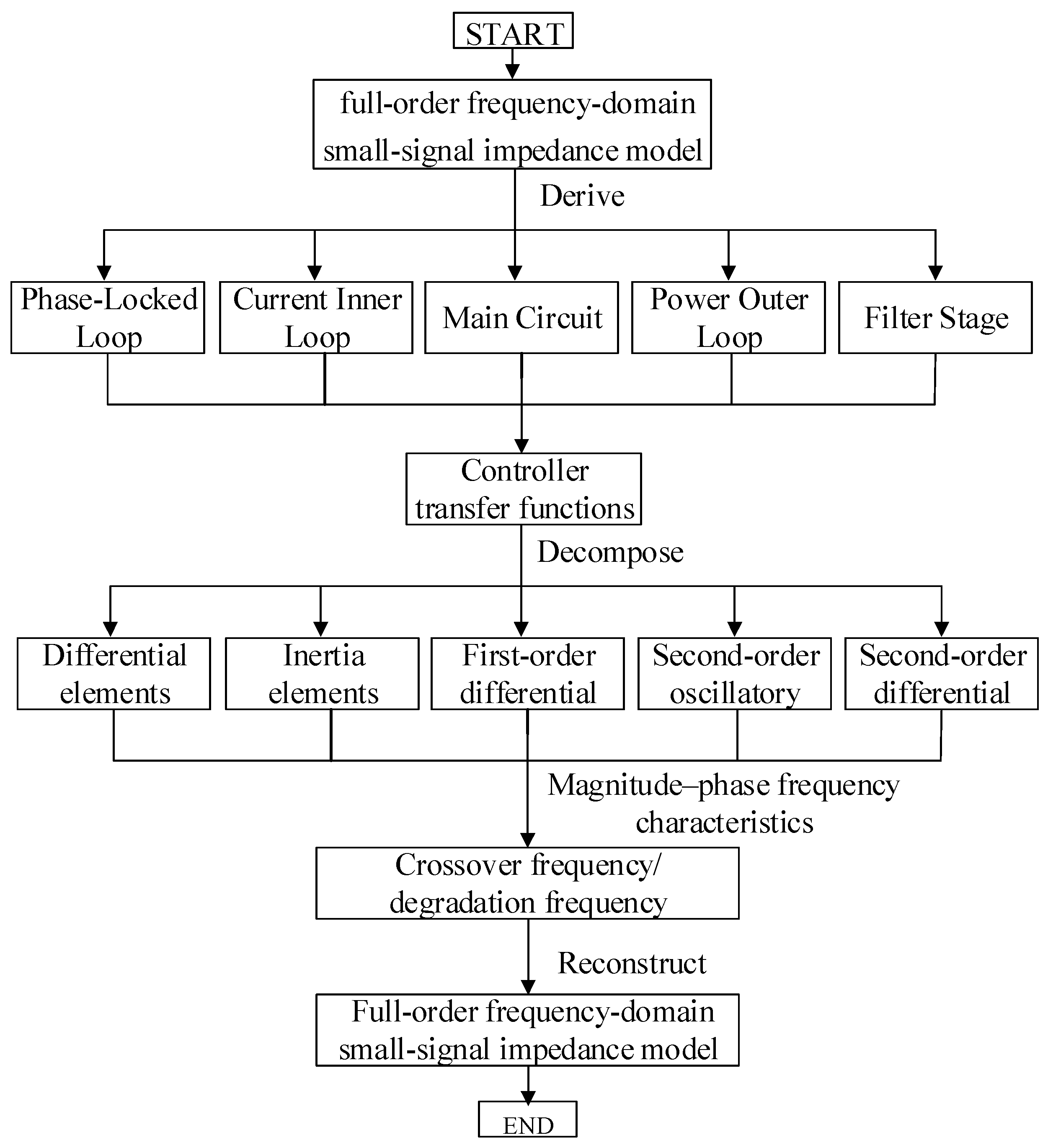

- (1)

- First, starting from the inherent properties of each control loop transfer function, consider the impact of a specific loop—such as the inner loop as a whole, the outer loop as a whole, or the phase-locked loop—on the frequency-domain impedance expression. This involves deriving the disturbance component transfer function for a given loop based on the disturbance signal and the control loop transmission path.

- (2)

- Decompose the transfer functions derived in Step 1 for primary control elements into typical components: differential elements, inertia elements, first-order differential elements, second-order oscillatory elements, second-order differential elements, etc. This enables further analysis of the magnitude of influence exerted by a specific element or part of an element within certain frequency bands.

- (3)

- Analyze the frequency bands where each decomposed typical element acts on the Bode plot of the transfer function. Identify the crossover frequency, and consider a tenfold engineering margin and the fundamental frequency shift to obtain the degradation frequency for that element. Perform order reduction of the transfer function at the degradation frequency, thereby completing the dynamic order reduction of this control element within the full-order impedance expression.

- (4)

- Repeat the above process for primary control elements, organize the degradation frequencies, and complete the reconstruction of the combined impedance model after dynamic order reduction across different frequency bands. The complete process is shown in the flowchart in Figure 2.

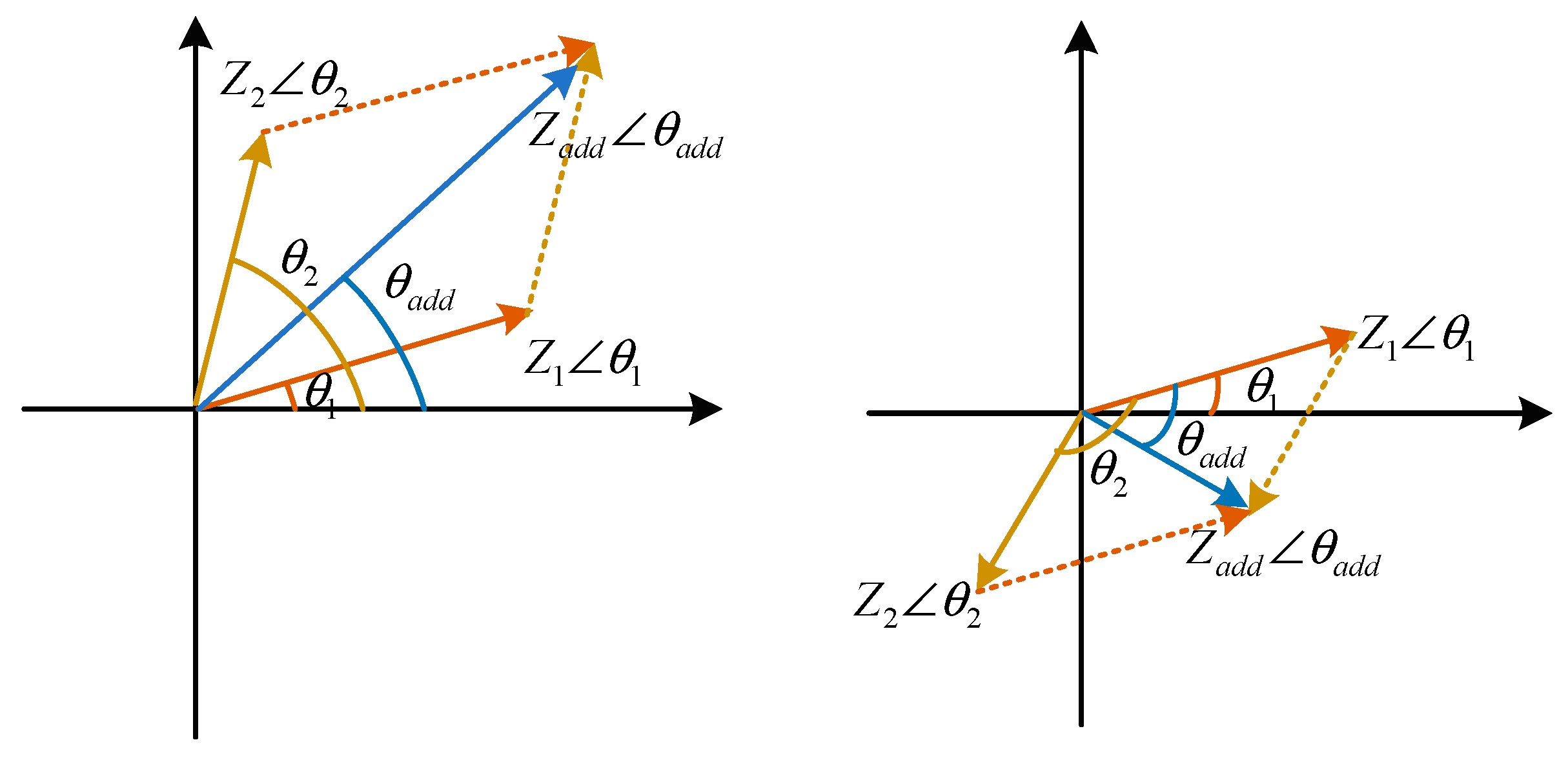

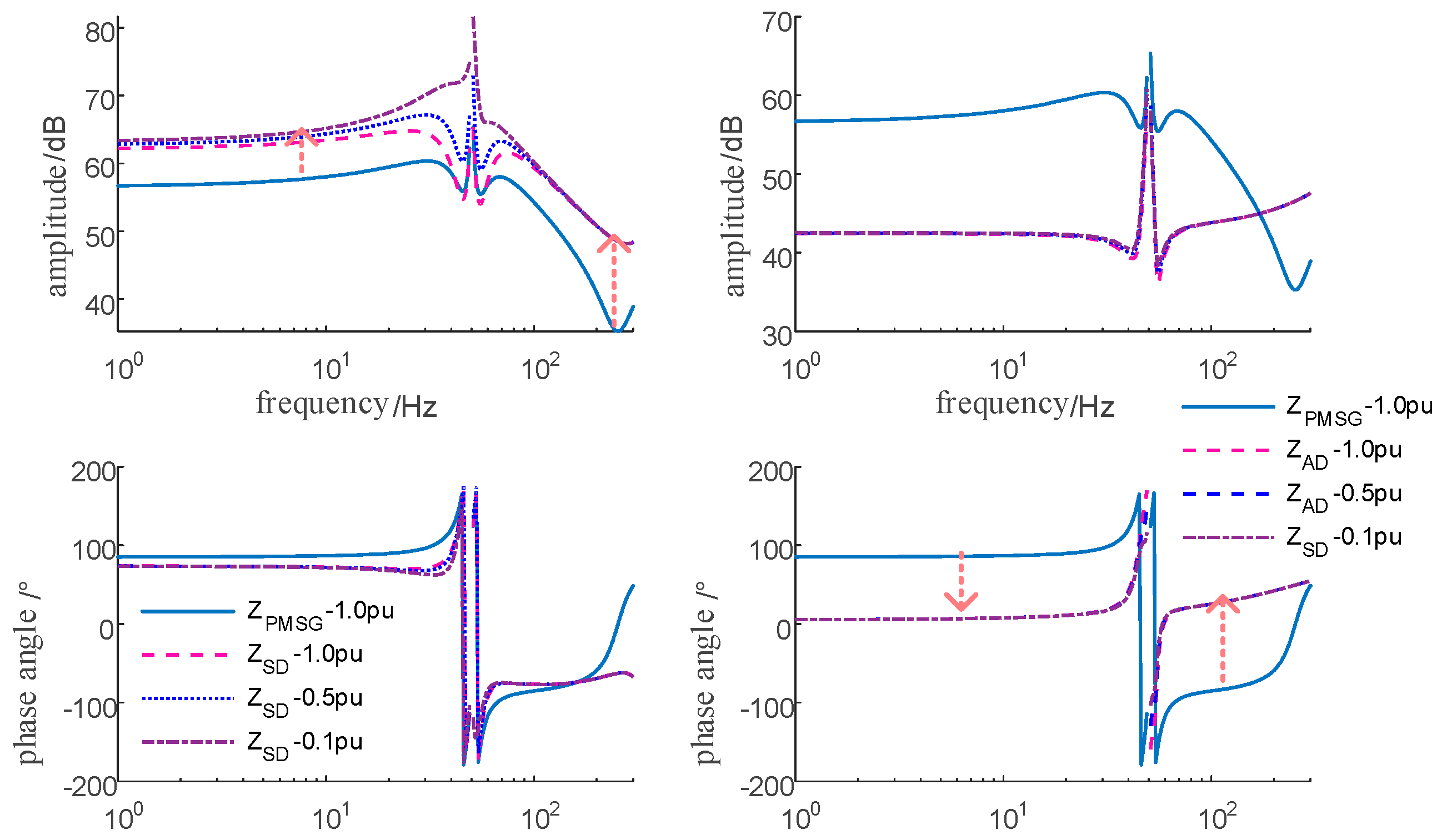

3. Analysis of Parallel Impedance Coupling Characteristics

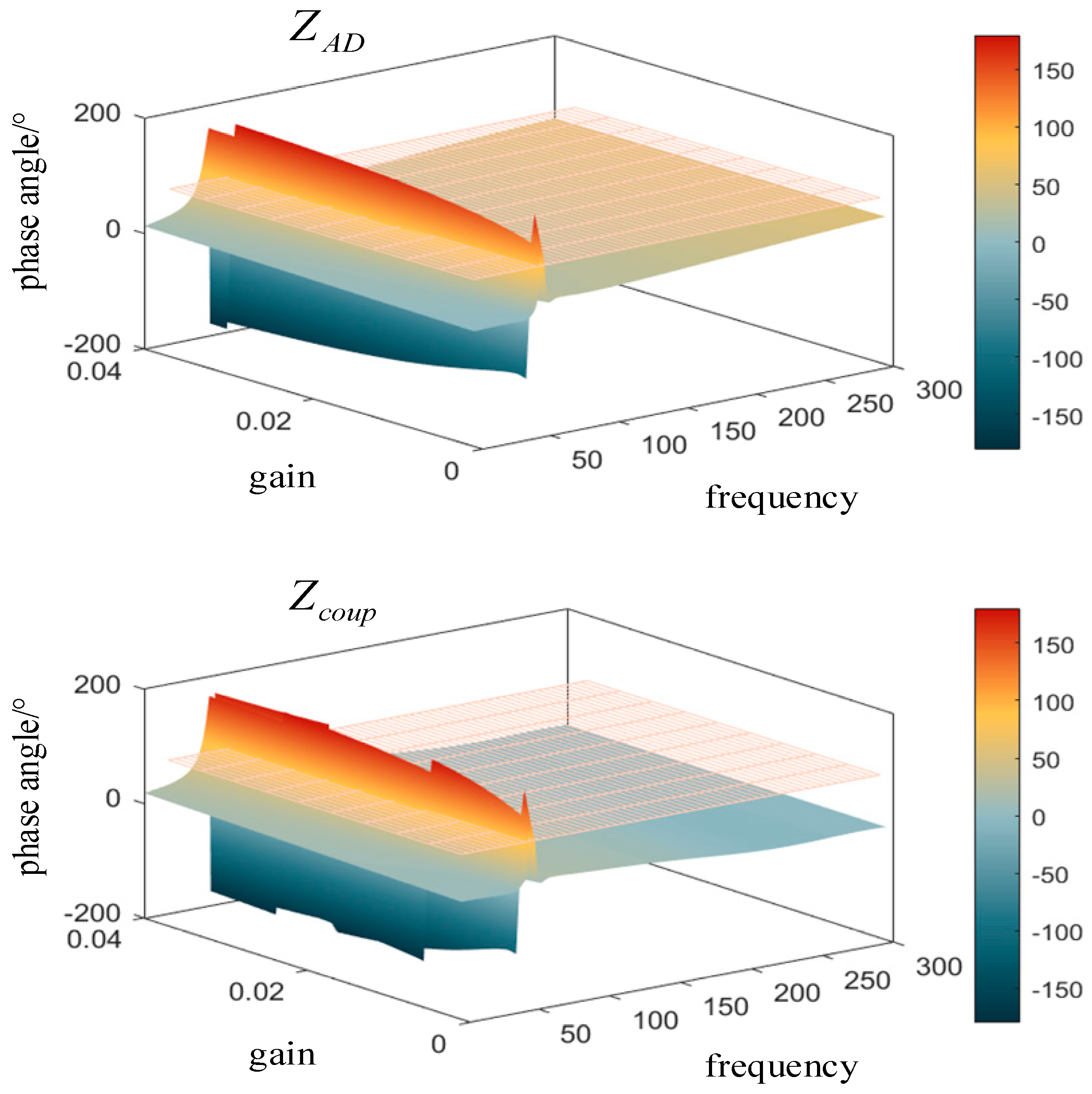

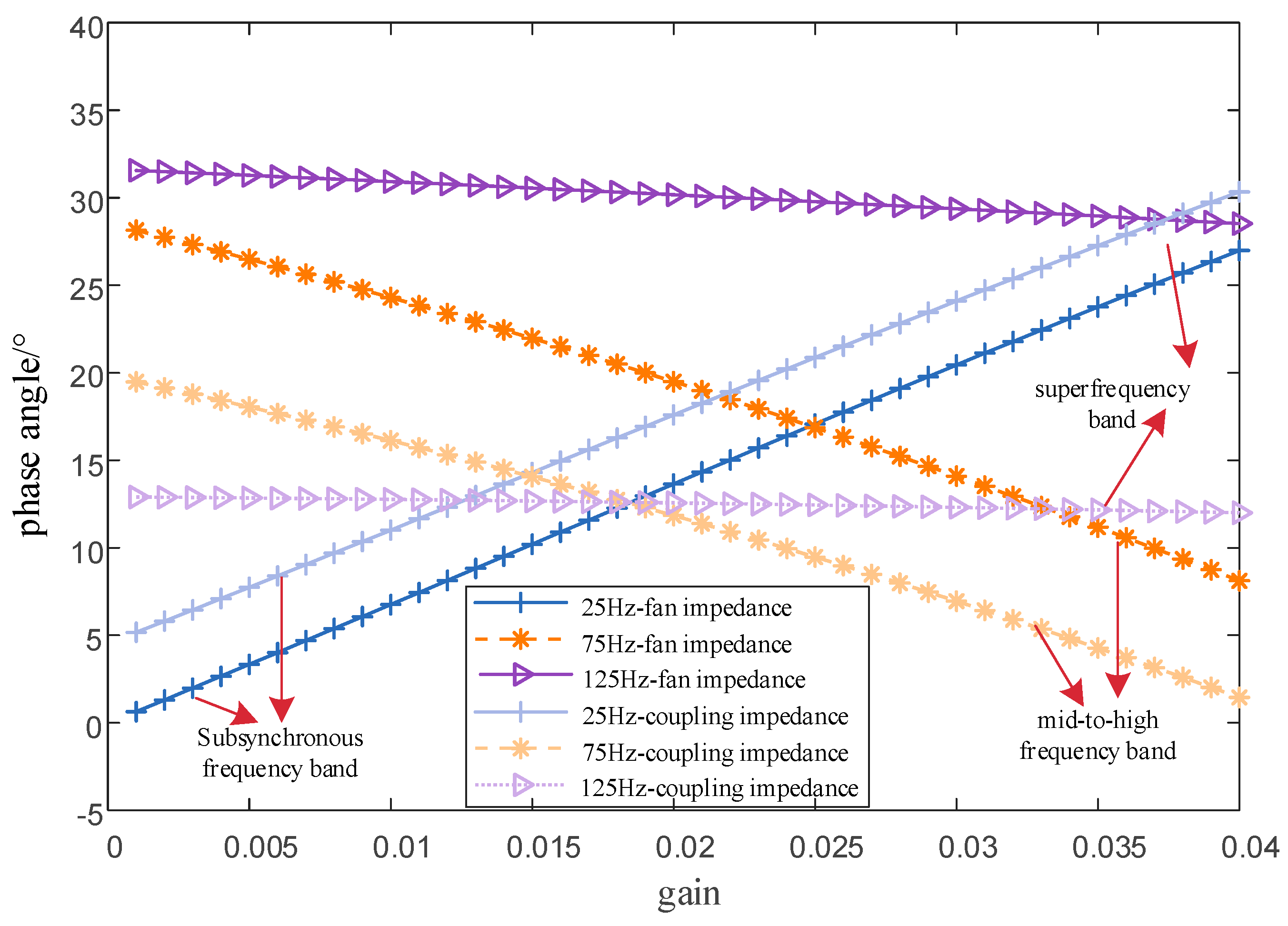

3.1. Phase-Frequency Characteristics of Parallel Coupling Impedance

3.2. Parallel Impedance Damping Characteristics

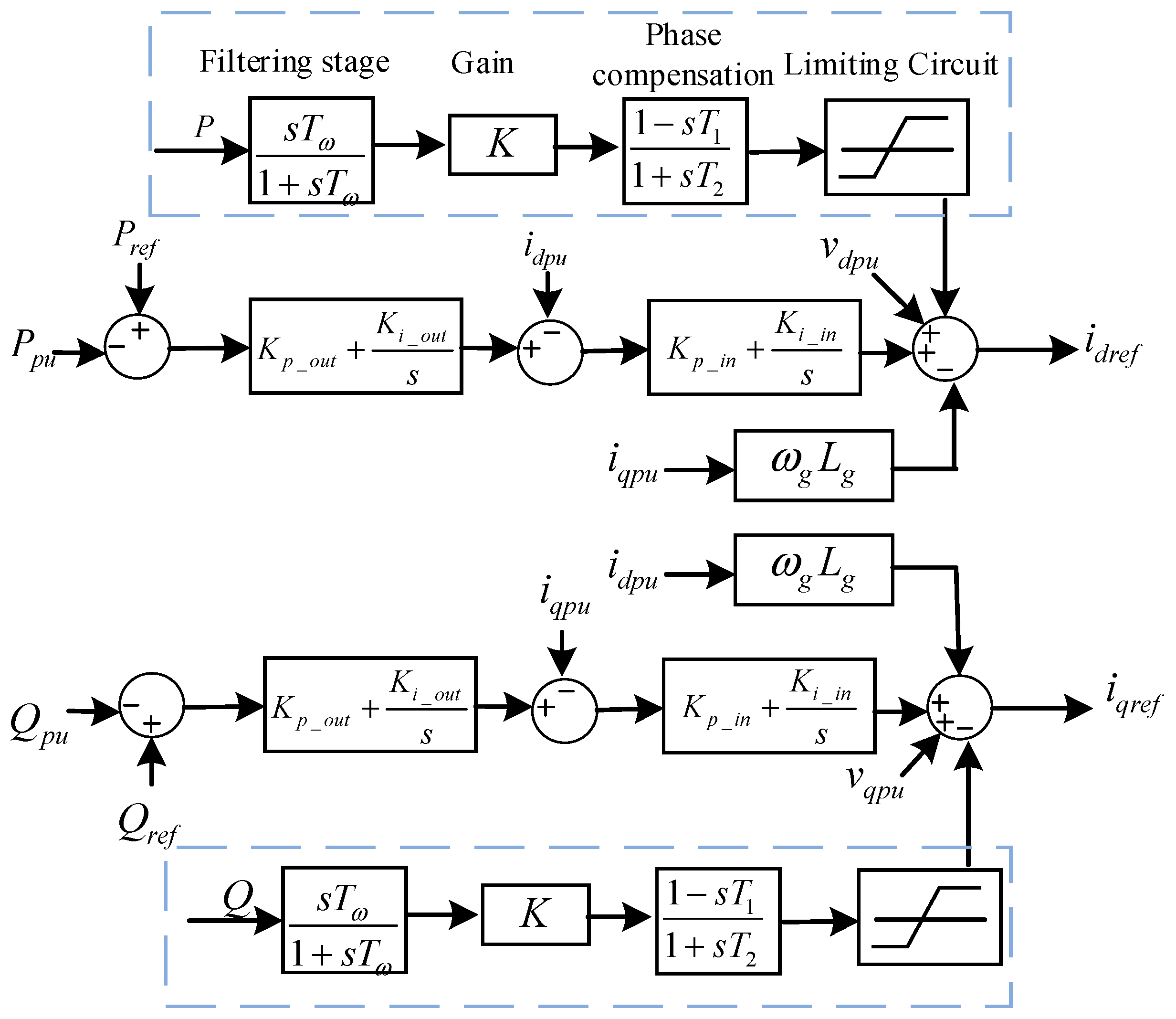

4. Additional Control Design

4.1. Additional Damping Control

4.2. Active Damping Based on Trap Filters

4.3. Design of Coupling Impedance for Parallel Wind Turbines

5. Simulation Verification

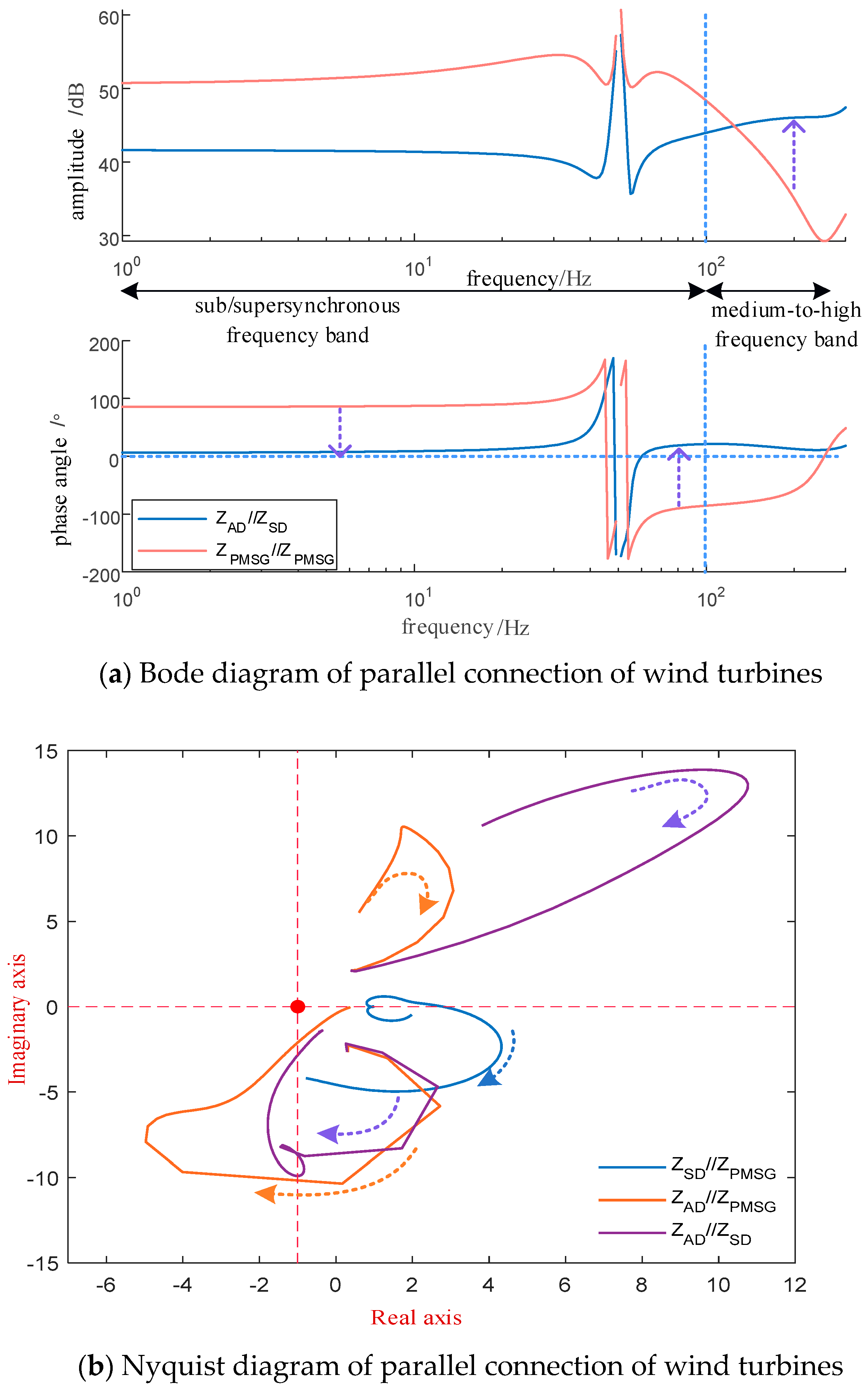

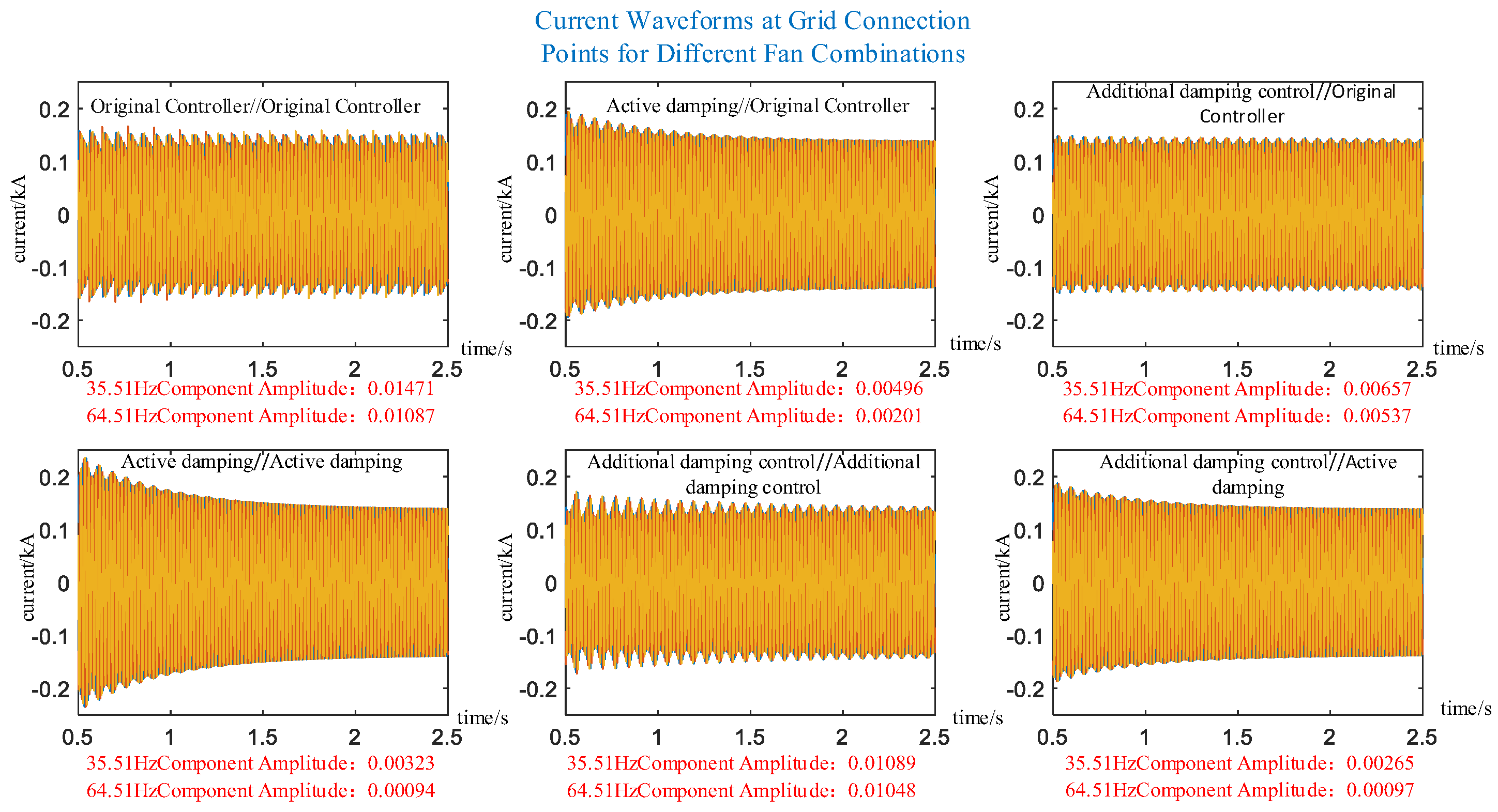

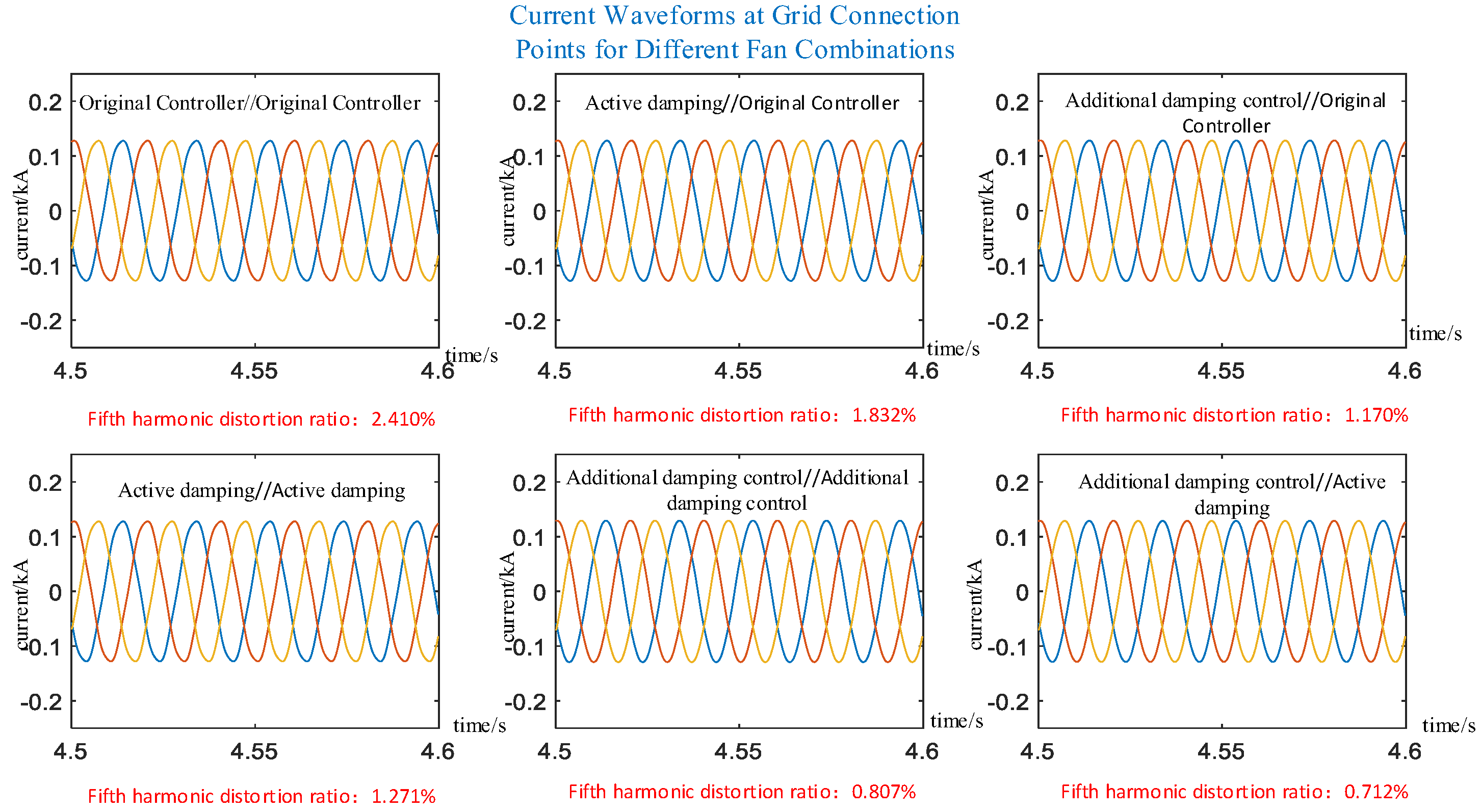

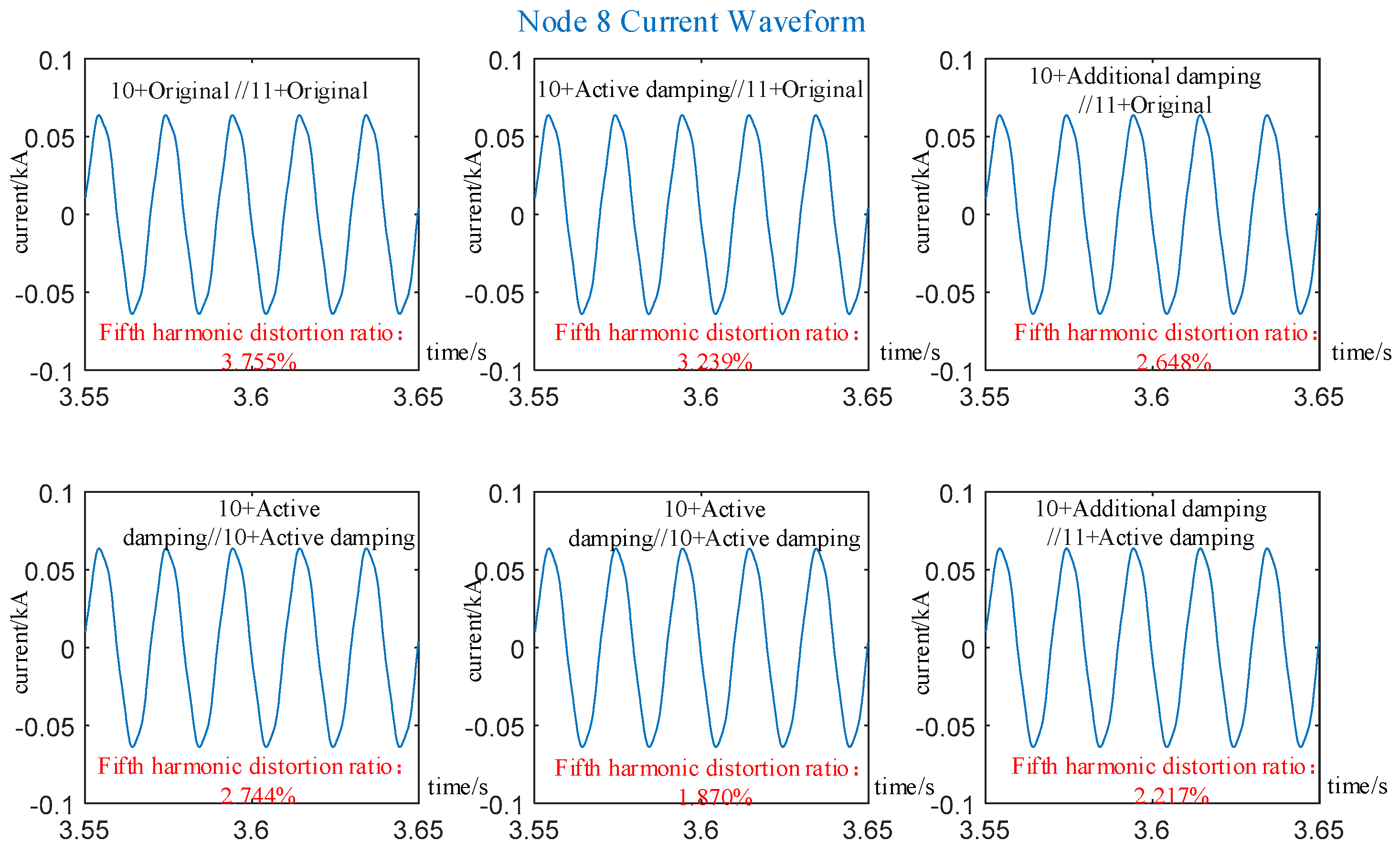

5.1. Analysis and Verification of Two Wind Turbines in an Infinite Grid

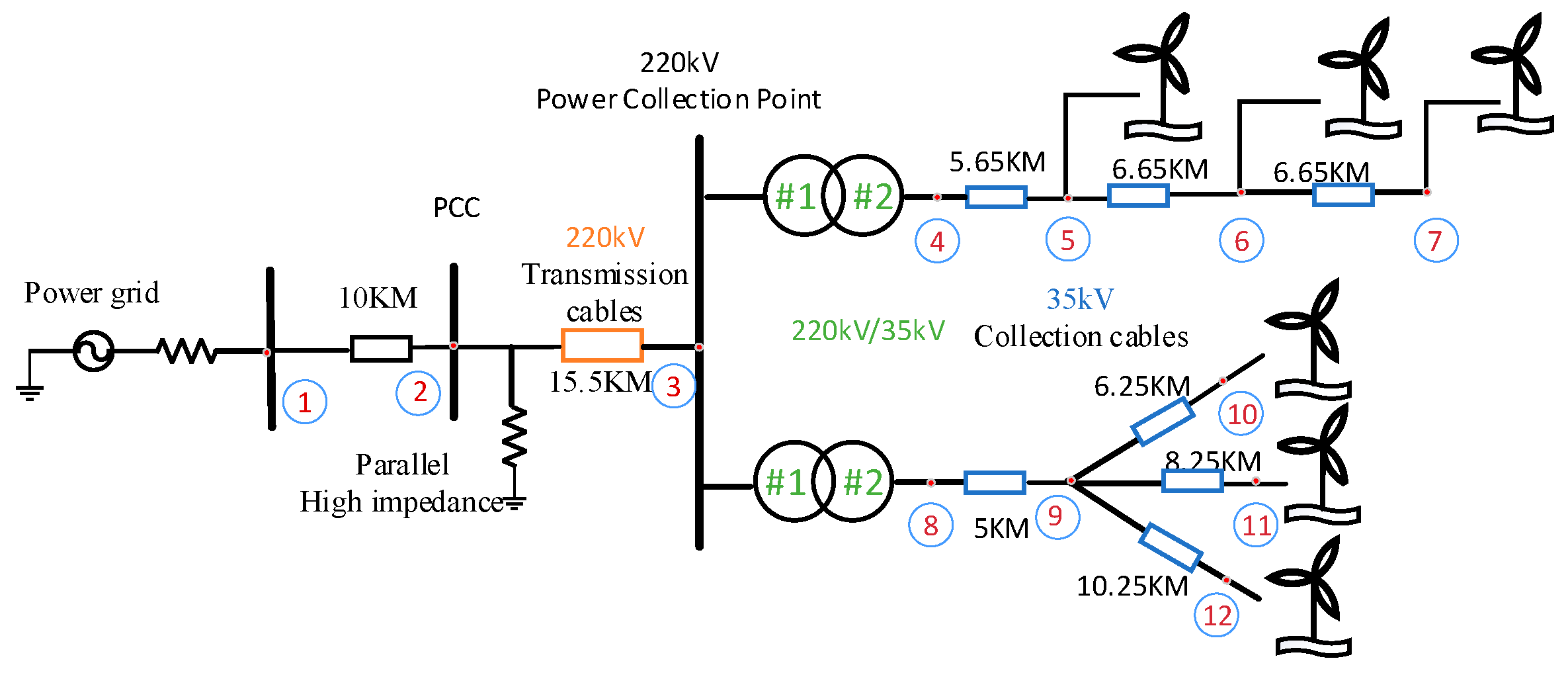

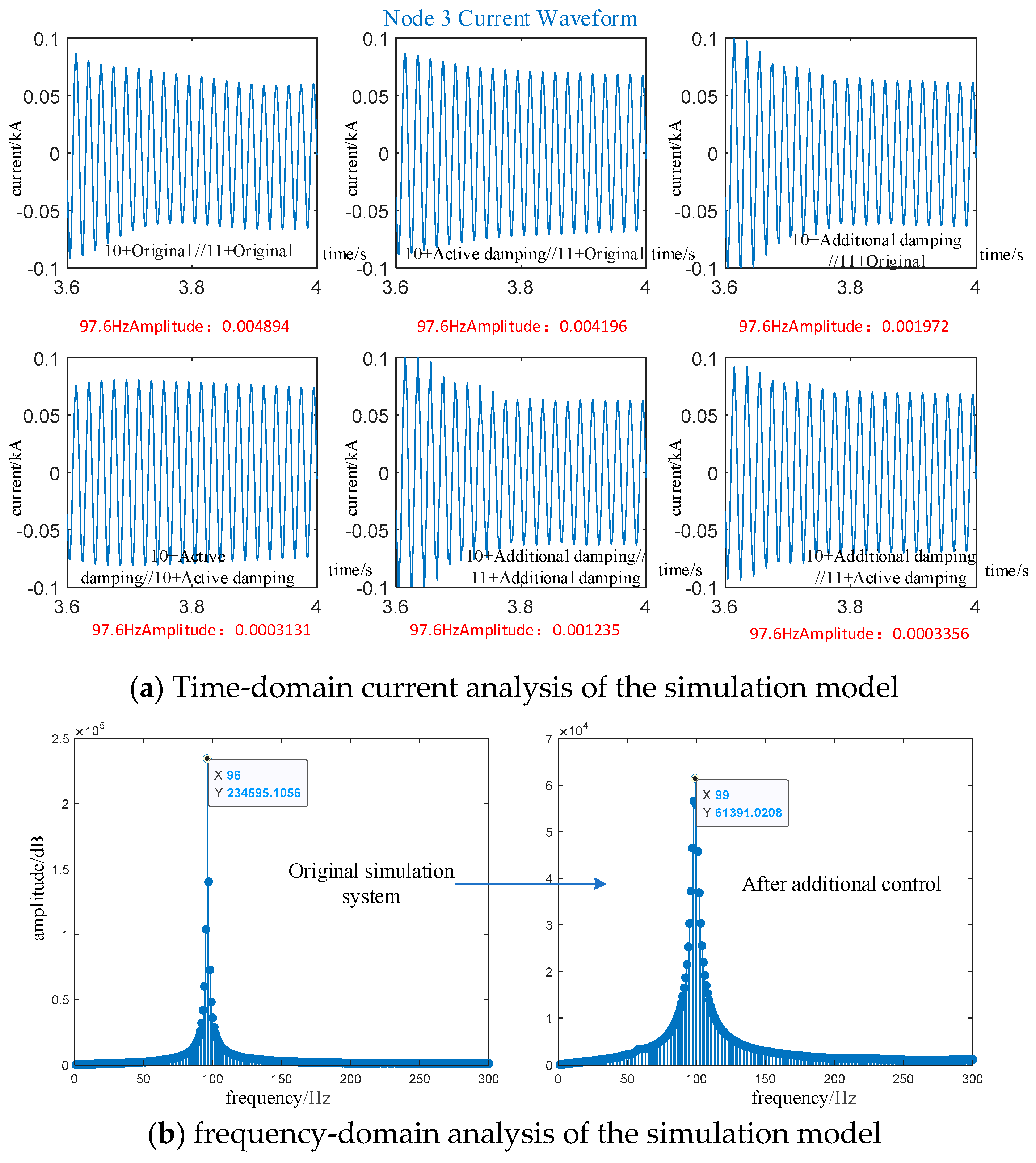

5.2. Simulation Model Validation Using the S-Domain Node Admittance Matrix Method

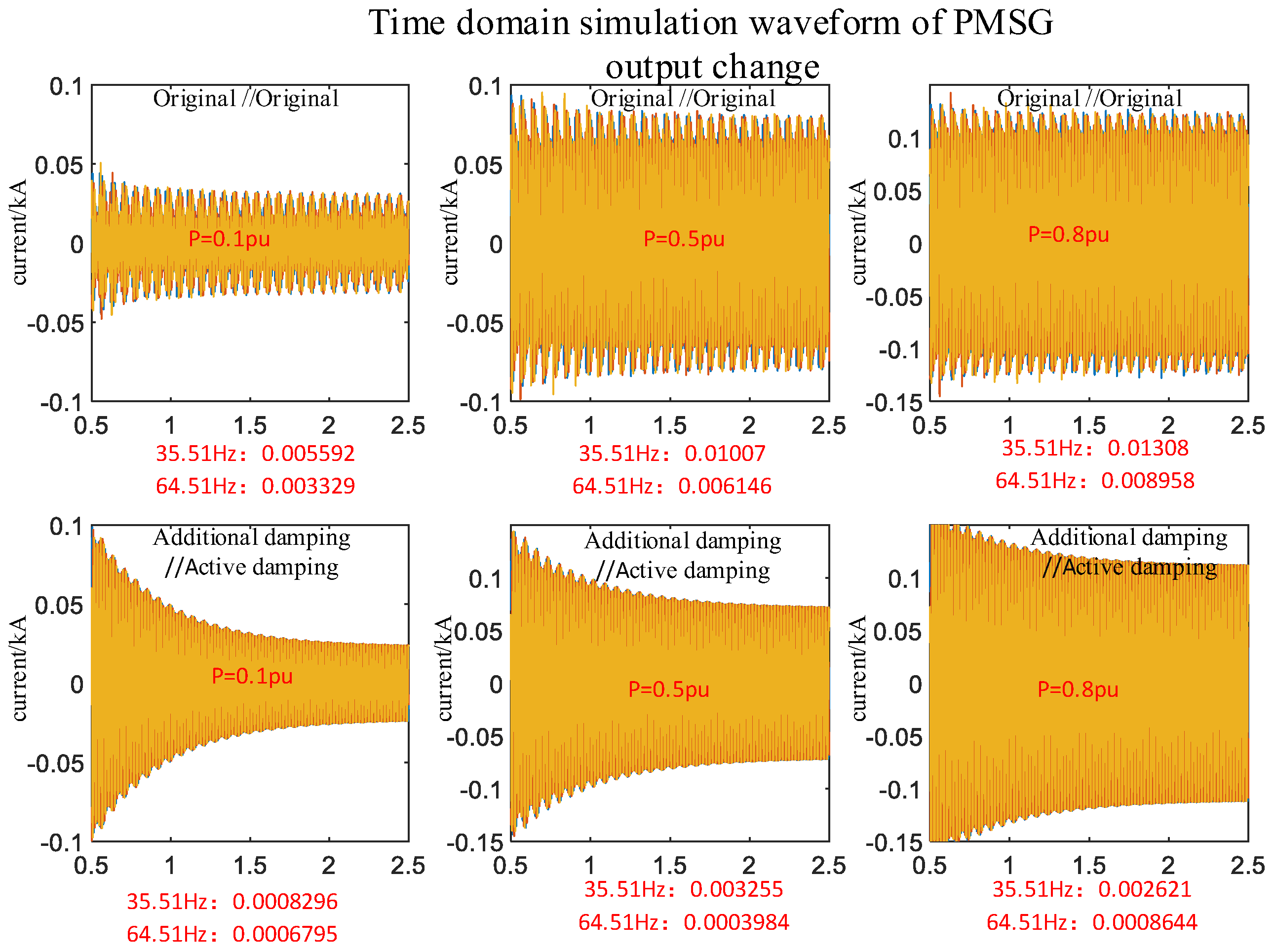

5.3. Verification of Control Strategy Robustness

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| PMSG | Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator |

| GSC | Grid-Side Converter |

| SVG | Static Var Generator |

| Active/Reactive Power Reference Values | |

| Active/Reactive Power Actual Values | |

| Outer Loop Proportional/Integral Coefficients | |

| Inner Loop Proportional/Integral Coefficients | |

| Voltage/Current Small-Signal Vector | |

| Disturbance Transfer Function from AC-side Voltage to PLL Output Phase | |

| Disturbance Transfer Function from PLL Output Phase to Valve-Side Voltage | |

| Disturbance Transfer Function from AC-Side Current to Valve-Side Voltage | |

| Disturbance Transfer Function from AC-Side Voltage to Valve-Side Voltage | |

| Parallel Coupling Impedance | |

| Wind Turbine Impedance Phase Angle | |

| Wind Turbine Admittance Expression | |

| Filtering Link Time Constant | |

| Wind Turbine Impedance with Active Damping Structure | |

| Wind Turbine Impedance with Additional Damping Control Structure | |

| Characteristic Frequency of the Active Damping Filter | |

| Notch Frequency of the Active Damping Structure | |

| L | Inductance Value at the Wind Turbine Terminal |

| PLL | Phase-Locked Loop |

| S | Complex Frequency Domain Variable |

| PLL Proportional/Integral Coefficients | |

| Steady-State Voltage Value | |

| PLL Output Phase Perturbation Signal Component | |

| PLL Total Transfer Function dq Coupling Term | |

| Inner Loop Degeneration Frequency | |

| Degenerated Disturbance Transfer Function from AC-Side Voltage to PLL | |

| Outer Loop Degeneration Frequency | |

| Filtering Link Degeneration Frequency | |

| PLL Degeneration Frequency | |

| Wind Turbine Impedance Magnitude | |

| Parallel Coupling Impedance Magnitude and Phase Angle | |

| Phase Compensation Link Time Constant | |

| Desired Filter Transfer Function | |

| Coupling Impedance after Control Modification | |

| n | Integer Variable |

| Gain of the Active Damping Structure Transfer Function | |

| Damping Ratio of the Active Damping Structure Notch Filter |

Appendix A

| Fifth Harmonic Distortion Ratio | Fifth Harmonic Content Amplitude | System Eigenvalue | Damping Ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10, 11 Original Controller | 4.465% | 0.001989 | −49.19 + j1561.31 | 0.0289 |

| 10 + Active, 11 + Original | 4.191% | 0.001866 | −45.4 + j1548.18 | 0.02931 |

| 10 + Addition,11 + Original | 3.849% | 0.001719 | −47.09 + j1550.14 | 0.03036 |

| 10, 11 Active | 3.886% | 0.001729 | −46.35 + j1531.87 | 0.03024 |

| 10, 11 Addition | 3.147% | 0.001406 | −49.99 + j1518.05 | 0.0329 |

| 10 + Addition, 11 + Active | 3.518% | 0.001572 | −47.53 + j1524.83 | 0.03115 |

References

- Wu, F.; Fang, C. The estimation of wind power resources in China. In Proceedings of the 2009 World Non-Grid-Connected Wind Power and Energy Conference, Beijing, China, 24–26 September 2009; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, J.; Wang, S.; Li, J. Echos, Suggestions, and Directions on New Energy Development in China under the Grid Parity. In Proceedings of the 2023 7th International Conference on Smart Grid and Smart Cities (ICSGSC), Lanzhou, China, 22–24 September 2023; pp. 250–255. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Z.; Wang, C.; Chen, N.; Ye, X.; Wu, S. Policy Requirements and Economic Affordability of Energy Storage for New Energy. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Power and Energy Engineering (ICPEE), Shanghai, China, 25–27 November 2022; pp. 330–333. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, R.; Xiong, Y.; Li, F.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, J.; Han, X.; Zhang, C. Analysis on Development Trend of North China Power Grid under the Background of Building the New Power System. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd Asian Conference on Frontiers of Power and Energy (ACFPE), Chengdu, China, 20–22 October 2023; pp. 585–590. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Suo, L.; Wang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Ma, Y. DFIG Band-Specific Impedance Reshaping and Wide-Band Oscillation Suppression Based on an Impedance-Decoupling Model. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 5th New Energy and Energy Storage System Control Summit Forum (NEESSC), Hohhot, China, 15–16 November 2025; pp. 115–120. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, N.; Li, H.; Xiong, W.; Wang, R. Small-Signal Stability Analysis and Oscillation Suppression Method for Grid-Following Inverters. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 3rd International Conference on Power Science and Technology (ICPST), Kunming, China, 16–18 May 2025; pp. 162–167. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, C.; Li, P.; Bin, Z. Study on the negative effect mechanism of the active damping suppression strategy of the wind power grid-connected inverter based on the damping factor. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Electrical, Mechanical and Computer Engineering (ICEMCE), Xi’an, China, 25–27 October 2024; pp. 856–860. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Gao, S.; Zhao, X.; Dong, Y.; Ding, J.; Xia, J.; Wang, H. An Active Damping Method for Harmonic Resonance of PV Station Based on Impetance Measurement. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE Sustainable Power and Energy Conference (iSPEC), Nanjing, China, 25–27 November 2021; pp. 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; Tu, Y.; Liu, Z. Comprehensive Analysis of Virtual Impedance-Based Active Damping for LCL Resonance in Grid-Connected Inverters. In Proceedings of the 2018 International Power Electronics Conference (IPEC-Niigata 2018-ECCE Asia), Niigata, Japan, 20–24 May 2018; pp. 2681–2687. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, F.; He, Z.; Zhang, J.; Nian, H. Data-Driven Modeling Method of Multi-Operation Impedance Identification for DFIG Based on Transfer Learning Theory. In Proceedings of the 2024 CPSS IEEE International Symposium on Energy Storage and Conversion (ISESC), Xi’an, China, 8–11 November 2024; pp. 377–382. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Liu, J. A Robust Control Strategy Research on PMSG-Based WECS Considering the Uncertainties. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 51951–51963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Z.; Ding, D.; Wang, G.; Li, B.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, G.; Xu, D. Adaptive Virtual Admittance Reshaping-Based Resonance Suppression Strategy for PMSM Drives With Small DC-Link Capacitor. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 3109–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Ma, S.; Zhou, P.; Xiang, Z.; Song, R.; Huang, R.; Hu, J. An Improved SVG Control Strategy to Suppress Sub-Synchronous Oscillation in Renewable Energy Power System. In Proceedings of the 2023 8th Asia Conference on Power and Electrical Engineering (ACPEE), Tianjin, China, 14–16 April 2023; pp. 2395–2399. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, X.; Chi, Y.; Li, Y.; Tang, H.; Liu, C.; Su, Y. Coordinated damping optimization control of sub-synchronous oscillation for DFIG and SVG. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 7, 140–149. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, M.; Li, D.; Liu, X.; Fan, L.; Zheng, K.; Chen, Q. Design of Passive Damping Filter for High-Frequency Oscillation Suppression of MMC. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 2nd International Power Electronics and Application Symposium (PEAS), Guangzhou, China, 10–13 November 2023; pp. 1531–1535. [Google Scholar]

- Micallef, A.; Apap, M.; Spiteri-Staines, C.; Guerrero, J.M. Mitigation of Harmonics in Grid-Connected and Islanded Microgrids Via Virtual Admittances and Impedances. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2017, 8, 651–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, Z.; Ding, G. Sub-synchronous Oscillation Suppression Measures for Doubly-fed Wind Turbine Based on Eigenvalue Analysis Method and Correlation Factor Method. In Proceedings of the 2019 6th International Conference on Systems and Informatics (ICSAI), Shanghai, China, 2–4 November 2019; pp. 234–238. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, B.; Wei, Y.; Xu, L.; Liu, Z. Sub-synchronous oscillation mechanism and analysis for wind farm integration through HVDC system. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Urban Engineering and Management Science (ICUEMS), Zhuhai, China, 24–26 April 2020; pp. 578–583. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, G.; Qifei, H.; Zhiguo, H.; Baohui, Z. The research of sub synchronous oscillation in PMSG wind farm. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE PES Asia-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference (APPEEC), Xi’an, China, 25–28 October 2016; pp. 1883–1887. [Google Scholar]

- An, Z.; Shen, C.; Zheng, Z.; Liu, F.; Zhang, X.; Chang, X.; Wei, W. Analysis on Sub-Synchronous Oscillation Associated with Wind Farms Based on Direct-Driven Wind Generators. In Proceedings of the 2018 37th Chinese Control Conference (CCC), Wuhan, China, 25–27 July 2018; pp. 1282–1286. [Google Scholar]

- Rawal, M.; Nauityal, D.C.; Rawat, M.S. Analysis of Small Signal Stability in DFIG Integrated Power System. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Advances in Electrical, Computing, Communication and Sustainable Technologies (ICAECT), Bhilai, India, 19–20 February 2021; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Supplementary Control of DFIG for Inter-Area Oscillation Damping. In Proceedings of the IECON 2014-40th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Dallas, TX, USA, 29 October–1 November 2014; pp. 5599–5605. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, T.; Zhao, H.; Wang, P. Impedance Model of PMSG-Based Wind Turbine System And Stability Analysis Based on Routh Criterion. In Proceedings of the 2024 7th International Conference on Energy, Electrical and Power Engineering (CEEPE), Yangzhou, China, 26–28 April 2024; pp. 1345–1350. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, L.; Xu, Z.; Feng, L.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, Z.; Xing, F. Analysis on Harmonic Resonance of Offshore Wind Farm Transmitted by MMC-HVDC System. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Innovative Smart Grid Technologies—Asia (ISGT Asia), Chengdu, China, 21–24 May 2019; pp. 2296–2301. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, H.; Nian, H.; Hu, B.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q. High-Frequency Resonance Analysis Between DFIG Based Wind Farm with Direct Power Control and VSC-HVDC. In Proceedings of the 2021 24th International Conference on Electrical Machines and Systems (ICEMS), Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 31 October–3 November 2021; pp. 2207–2212. [Google Scholar]

- Ge, H.; Zhen, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, D. Research on LCL filter active damping strategy in active power filter system. In Proceedings of the 2017 9th International Conference on Modelling, Identification and Control (ICMIC), Kunming, China, 10–12 July 2017; pp. 476–481. [Google Scholar]

- Zou, B.; Bakhshai, A.; Jain, P. Active Damping of LCL Filter Resonance for Grid-Connected Distributed Power Generation Systems. In Proceedings of the IECON 2019-45th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Lisbon, Portugal, 14–17 October 2019; pp. 4683–4688. [Google Scholar]

- Adapa, A.K.; John, V. Virtual Resistor Based Active Damping of LC Filter in Standalone Voltage Source Inverter. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), San Antonio, TX, USA, 4–8 March 2018; pp. 1834–1840. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Chen, Y.; Luo, A.; Liu, X. Wideband Harmonic Voltage Feedforward Control Strategy of STATCOM for Mitigating Subsynchronous Resonance in Wind Farm Connected to Weak Grid and LCC HVDC. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2021, 9, 4546–4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.X.; Li, H.Y.; Li, Z.W. Impedance modeling and stability analysis of LCL-type grid-connected inverters with different current sampling schemes. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 8th International Power Electronics and Motion Control Conference (IPEMC-ECCE Asia), Hefei, China, 22–26 May 2016; pp. 974–981. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Liu, H. Impedance modeling and analysis of modular multilevel converters. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 17th Workshop on Control and Modeling for Power Electronics (COMPEL), Trondheim, Norway, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Z.; Ruan, X.; Wu, L.; Zhang, H.; Li, W. Multi resonant Component-Based Grid-Voltage-Weighted Feedforward Scheme for Grid-Connected Inverter to Suppress the Injected Grid Current Harmonics Under Weak Grid. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 9784–9793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. Impedance-Based Stability Criterion for Grid-Connected Inverters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2011, 26, 3075–3078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z. Resonance stability analysis method based on s-domain node admittance matrix. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2023, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

| Research Literature | Control Strategy Type | Complexity | Efficiency | Feasibility | Controller Cost | Core Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [7] | Current Loop Filter | Modification only to the current loop; Simple | Effective only at sub-synchronous frequencies; No suppression at mid/high frequencies; High control efficiency | High | No hardware required; Low cost | Only targets a single frequency band; Does not account for multi-unit impedance magnitude and phase coupling |

| [8] | Adaptive Notch Filter | Can dynamically update to track oscillation frequency | Low computational efficiency | Medium | No hardware required; Low cost | Only considers a single machine; Does not account for multi-unit impedance magnitude and phase coupling |

| [9] | Additional Damping Branch | Additional damping channel; Modification is relatively simple | Effective only at sub-synchronous frequencies; No suppression at mid/high frequencies; High control efficiency | High | No hardware required; Low cost | Only targets a single frequency band; Does not account for multi-unit impedance magnitude and phase coupling |

| [10] | Data-Driven Control | Can self-adapt to oscillation frequency; Complex structure | Low computational efficiency | Low | No hardware required; Low cost | Only targets inter-area low-frequency oscillations; Does not account for multi-unit impedance magnitude and phase coupling |

| [15] | External Compensation Device | Simple | Wide frequency coverage; High efficiency | High | Requires hardware equipment; High cost | Cannot suppress oscillations at their root cause |

| This Paper | Coordinated Reshaping of Magnitude-Frequence Characteristics | Simple | Covers sub-/super-synchronous and mid/high frequency bands; High efficiency | High | No hardware required; Low cost | Coordinated control for hybrid systems with heterogeneous multi-type units requires further investigation |

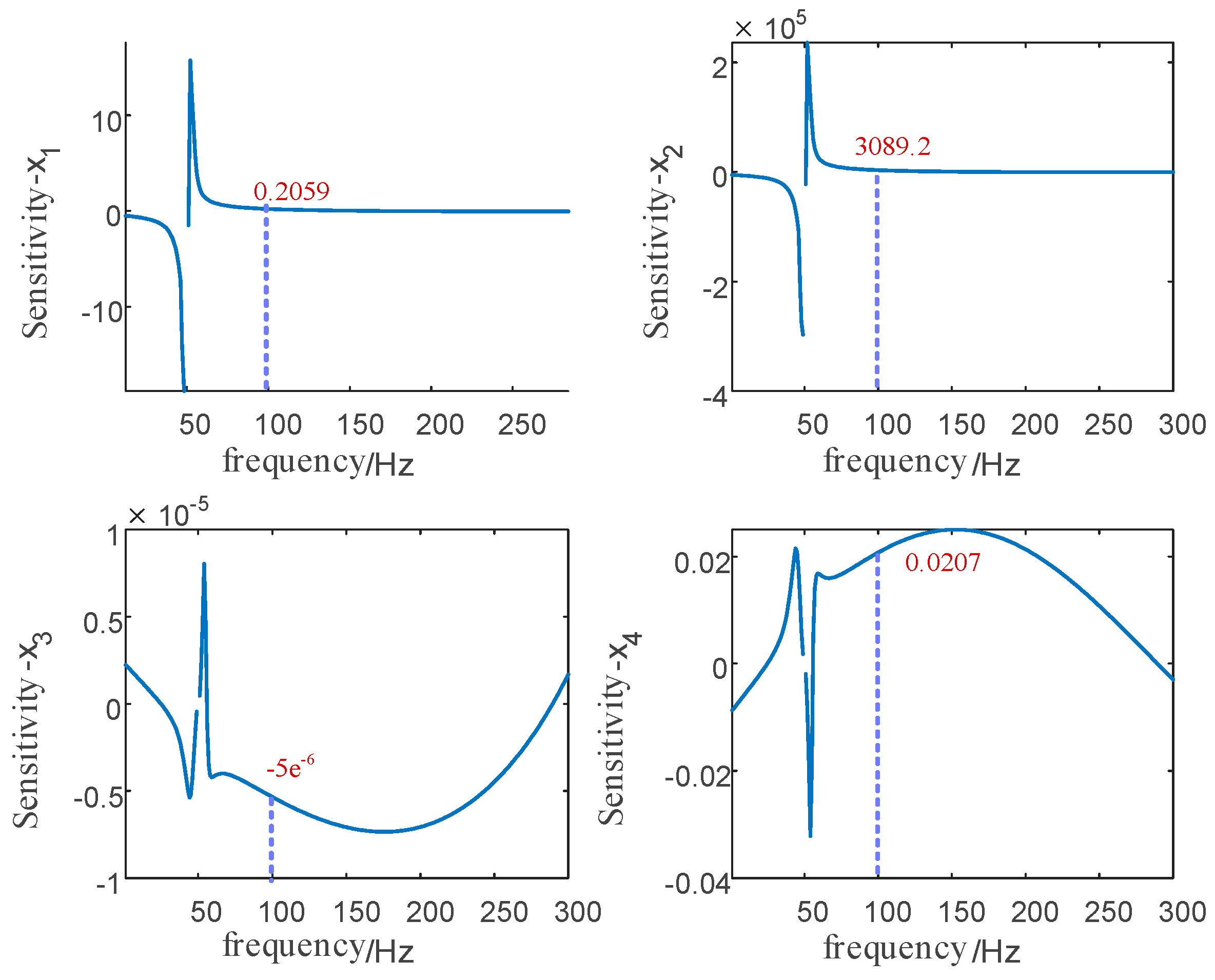

| Objective | X1 | X2 | X3 | X4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| objective 1 | 300 | 0.01 | 50 | 0.1 |

| objective 2 | 300 | 0.04 | 50 | 0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sun, H.; Fu, G.; Wang, X.; Gan, Y.; Ding, Y.; Sun, S.; Wang, T. A Multi-Mode Oscillation Suppression Strategy for Grid-Connected Inverter Systems Based on Amplitude–Phase Reconstruction. Electronics 2025, 14, 4761. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234761

Sun H, Fu G, Wang X, Gan Y, Ding Y, Sun S, Wang T. A Multi-Mode Oscillation Suppression Strategy for Grid-Connected Inverter Systems Based on Amplitude–Phase Reconstruction. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4761. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234761

Chicago/Turabian StyleSun, Haibin, Guobin Fu, Xuebin Wang, Yuxin Gan, Yujie Ding, Shangde Sun, and Tong Wang. 2025. "A Multi-Mode Oscillation Suppression Strategy for Grid-Connected Inverter Systems Based on Amplitude–Phase Reconstruction" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4761. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234761

APA StyleSun, H., Fu, G., Wang, X., Gan, Y., Ding, Y., Sun, S., & Wang, T. (2025). A Multi-Mode Oscillation Suppression Strategy for Grid-Connected Inverter Systems Based on Amplitude–Phase Reconstruction. Electronics, 14(23), 4761. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234761