A Compact GPT-Based Multimodal Fake News Detection Model with Context-Aware Fusion

Abstract

1. Introduction

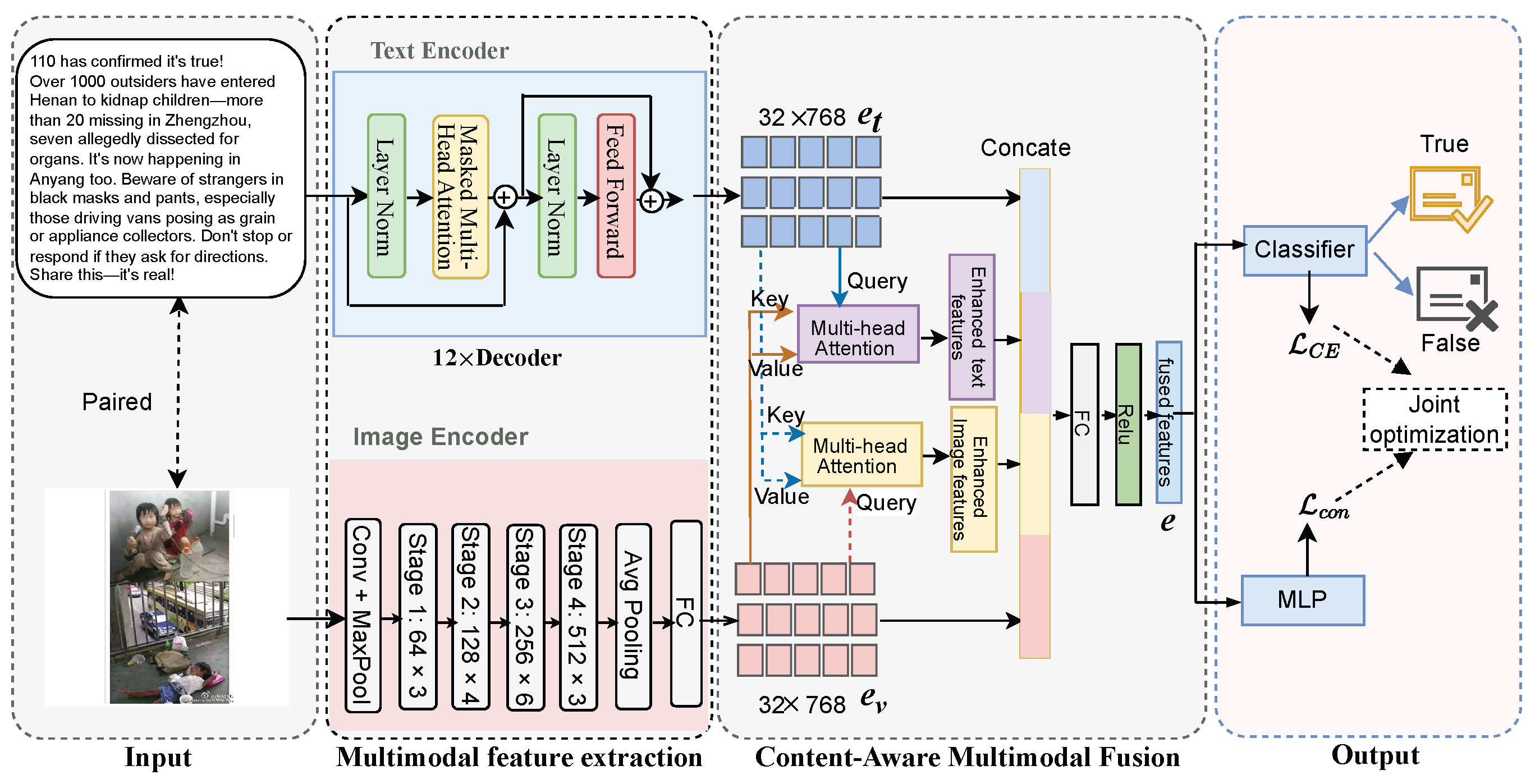

- We propose a multimodal fake news detection model based on T-GPT and context-aware multimodal fusion method (CA-MFD), which efficiently integrates semantic information from both image and text while simultaneously preserving the original text and image features. This approach effectively captures the correlations between modalities and enhances the representation of key features, thereby improving the accuracy and robustness of fake news detection.

- We introduce T-GPT for text feature extraction in multimodal fake news detection. By leveraging T-GPT to encode text data, it successfully extracts deep semantic features, thereby providing strong support for subsequent fake news detection tasks.

- We conduct extensive experiments on two publicly available dataset for multimodal fake news detection. And the experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves a significant performance improvement in fake news detection tasks.

- We design a joint optimization strategy that combines contrastive loss and cross-entropy loss. This strategy enhances the model’s ability to align modalities and discriminate features while optimizing classification performance.

2. Related Works

3. The Proposed Method

3.1. Problem Definition

3.2. Method Overview

3.3. Multimodal Feature Extraction

3.3.1. Text Embedding

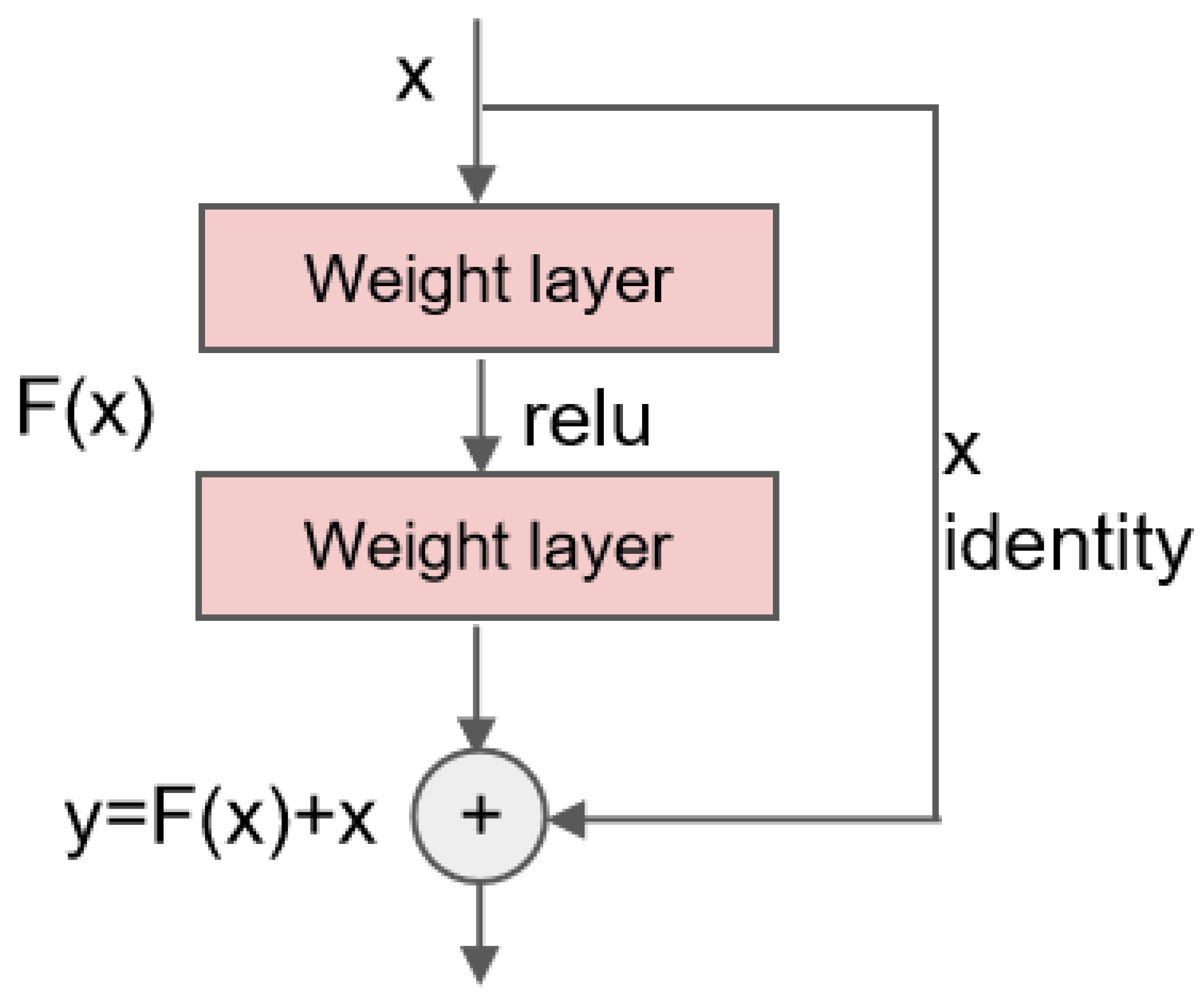

3.3.2. Visual Embedding

3.4. Context-Aware Multimodal Fusion

3.5. Classify

3.6. Model Learning

4. Experiments

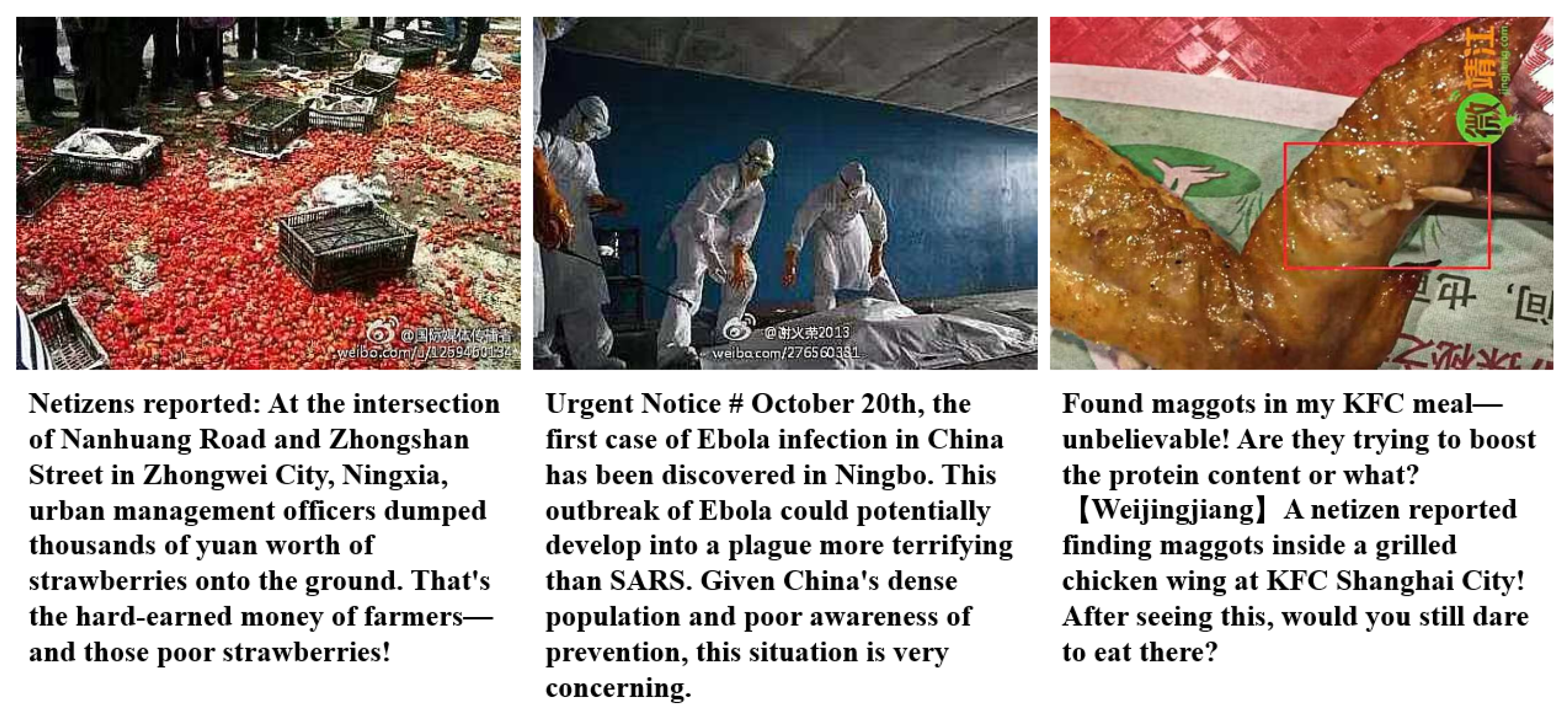

4.1. Dataset

4.1.1. Dataset Description

4.1.2. Preprocessing

- Evaluation Metrics

- True Positives (TP): The number of positive samples accurately predicted by the model.

- True Negatives (TN): The number of negative samples accurately predicted by the model.

- False Positives (FP): The number of actual negative samples incorrectly classified as positive by the model, also known as false alarms.

- False Negatives (FN): The number of actual positive samples incorrectly classified as negative by the model, also known as missed detections.

4.2. Baselines

4.2.1. Multimodal Methods

4.2.2. BERT Series Models

4.3. Comparison Experiments

4.3.1. Experimental Settings

4.3.2. Overall Performance

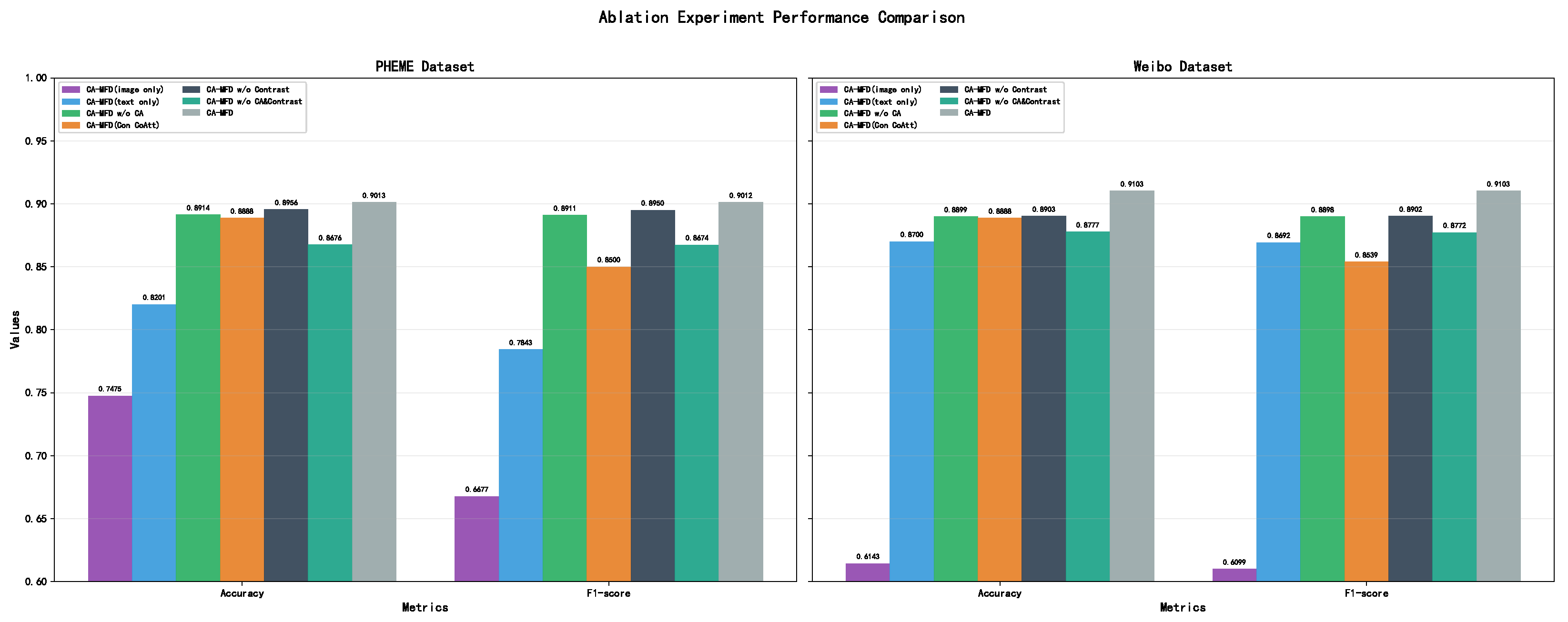

4.3.3. Ablation Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BERT | Bidirectional Encoder Representations from Transformers |

| PERT | Pre-training BERT with Permuted Language Model |

| LERT | Linguistically motivated bidirectional Encoder Representation from Transformer |

| MiniRBT | Mini RoBERTa (A Two-stage Distilled Small Chinese Pre-trained Model) |

| GPT-3 | Generative Pre-trained Transformer 3 |

| ResNet | Residual Network |

| CA | Context-Aware |

| MFD | Multimodal Fake News Detection |

| T-GPT | TurkuNLP/gpt3-finnish-small model |

References

- Comito, C.; Caroprese, L.; Zumpano, E. Multimodal Fake News Detection on Social Media: A Survey of Deep Learning Techniques. Soc. Netw. Anal. Min. 2023, 13, 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, F.; Jin, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Xun, G.; Jha, K.; Su, L.; Gao, J. EANN: Event Adversarial Neural Networks for Multi-Modal Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, London, UK, 19–23 August 2018; pp. 849–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Volume 1 (Long and Short Papers); Association for Computational Linguistics: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.; Wang, J.; Hu, J.; Fang, Q.; Xu, C. Hierarchical Multi-modal Contextual Attention Network for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 44th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, Virtual Event, Canada, 11–15 July 2021; pp. 153–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Obaid, A.; Khotanlou, H.; Mansoorizadeh, M.; Zabihzadeh, D. Multimodal Fake-News Recognition Using Ensemble of Deep Learners. Entropy 2022, 24, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Segura-Bedmar, I.; Alonso-Bartolome, S. Multimodal Fake News Detection. Information 2022, 13, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.B.; Mann, B.; Ryder, N.; Subbiah, M.; Kaplan, J.; Dhariwal, P.; Neelakantan, A.; Shyam, P.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; et al. Language Models Are Few-Shot Learners. In Proceedings of the 34th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 6–12 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Group, T.R. TurkuNLP Finnish GPT-3 Models. 2022. Available online: https://huggingface.co/TurkuNLP/gpt3-finnish-small (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Jin, Z.; Cao, J.; Guo, H.; Zhang, Y.; Luo, J. Multimodal Fusion with Recurrent Neural Networks for Rumor Detection on Microblogs. In Proceedings of the 25th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Mountain View, CA, USA, 23–27 October 2017; pp. 795–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 6000–6010. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, C.; Fu, X.; Feng, Q.; Zhu, Q.; Cao, Y.; Zhu, Y. A Multimodal Fusion Network with Attention Mechanisms for Visual–Textual Sentiment Analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 242, 122731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Liu, Q.; Wu, S.; Wang, L.; Tan, T. A Convolutional Approach for Misinformation Identification. In Proceedings of the 26th International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Melbourne, Australia, 19–25 August 2017;IJCAI’17; pp. 3901–3907. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, T.; Li, X.; Yin, H.; Zhang, J. Call Attention to Rumors: Deep Attention Based Recurrent Neural Networks for Early Rumor Detection. In Trends and Applications in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Ganji, M., Rashidi, L., Fung, B.C.M., Wang, C., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 40–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, R.; Pan, W.; Peng, C.; Yin, P. A Microblog Rumor Detection Method Based on Multi-Task Learning. Comput. Eng. Appl. 2021, 57, 192–197. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, S.; Hu, J.; Fang, Q.; Xu, C. Knowledge-Aware Multi-modal Adaptive Graph Convolutional Networks for Fake News Detection. ACM Trans. Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2021, 17, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Shah, R.R.; Chakraborty, T.; Kumaraguru, P.; Satoh, S. SpotFake: A Multi-modal Framework for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Fifth International Conference on Multimedia Big Data (BigMM), Singapore, 11–13 September 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, A.; Thota, N.; Prakasam, P. Fake News Detection and Classification Using Hybrid BiLSTM and Self-Attention Model. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 18503–18519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahdanau, D.; Cho, K.; Bengio, Y. Neural Machine Translation by Jointly Learning to Align and Translate. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.0473. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Y.; Zhan, P.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, L.; Xu, Z. Multimodal Fusion with Co-Attention Networks for Fake News Detection. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP 2021; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2021; pp. 2560–2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.; Zhao, Z.; Qi, W.; Song, X.; Nie, L. Multimodal Matching-Aware Co-Attention Networks with Mutual Knowledge Distillation for Fake News Detection. Inf. Sci. 2024, 664, 120310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.J.; Li, C.T. GCAN: Graph-aware Co-Attention Networks for Explainable Fake News Detection on Social Media. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 505–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Ma, Y.; An, L.; Li, G. BCMF: A bidirectional cross-modal fusion model for fake news detection. Inf. Process. Manag. 2022, 59, 103063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anggrainingsih, R.; Hassan, G.M.; Datta, A. Evaluating BERT-based Pre-Training Language Models for Detecting Misinformation. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.07731. [Google Scholar]

- Pelrine, K.; Danovitch, J.; Rabbany, R. The Surprising Performance of Simple Baselines for Misinformation Detection. In Proceedings of the Web Conference, WWW ’21, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 3432–3441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kula, S.; Choraś, M.; Kozik, R. Application of the Bert-Based Architecture in Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 13th International Conference on Computational Intelligence in Security for Information Systems (CISIS 2020), Burgos, Spain, 16–18 September 2020; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 239–249. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, W.; Zhang, X.; Shang, M. Multi-View mutual learning network for multimodal fake news detection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 279, 127407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubiaga, A.; Liakata, M.; Procter, R. Exploiting Context for Rumour Detection in Social Media. In Proceedings of the Social Informatics; Ciampaglia, G.L., Mashhadi, A., Yasseri, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 109–123. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Nakashima, Y.; Chen, H.; Babaguchi, N. Enhancing Fake News Detection in Social Media via Label Propagation on Cross-Modal Tweet Graph. In Proceedings of the 31st Acm International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 2400–2408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Wang, W.; Sun, H.; Rocha, A.; Li, H. Robust Domain Misinformation Detection via Multi-Modal Feature Alignment. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2024, 19, 793–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khattar, D.; Goud, J.S.; Gupta, M.; Varma, V. MVAE: Multimodal Variational Autoencoder for Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the World Wide Web Conference, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 May 2019; pp. 2915–2921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Li, D.; Zhang, P.; Sui, J.; Lv, Q.; Tun, L.; Shang, L. Cross-Modal Ambiguity Learning for Multimodal Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the ACM Web Conference 2022, Virtual Event, Lyon, France, 25–29 April 2022; pp. 2897–2905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Wu, J.; Zafarani, R. SAFE: Similarity-Aware Multi-modal Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the Advances in Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining: 24th Pacific-Asia Conference, PAKDD 2020, Singapore, 11–14 May 2020; Proceedings, Part II. Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 354–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, S.; Kabra, A.; Sharma, M.; Shah, R.R.; Chakraborty, T.; Kumaraguru, P. SpotFake+: A Multimodal Framework for Fake News Detection via Transfer Learning (Student Abstract). Proc. AAAI Conf. Artif. Intell. 2020, 34, 13915–13916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Yang, Y.; Ying, Q.; Qian, Z.; Zhang, X. Multimodal Fake News Detection via CLIP-guided Learning. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Multimedia and Expo, Brisbane, Australia, 10–14 July 2023; pp. 2825–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Huang, M.; Hu, Z.; Cai, S.; Zhou, T. Multimodal Fake News Detection with Contrastive Learning and Optimal Transport. Front. Comput. Sci. 2024, 6, 1473457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Che, W.; Wang, S.; Liu, T. LERT: A Linguistically-motivated Pre-trained Language Model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2211.05344. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Yang, Z.; Liu, T. PERT: Pre-training BERT with Permuted Language Model. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.06906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, X.; Yang, Z.; Cui, Y.; Wang, S. MiniRBT: A Two-stage Distilled Small Chinese Pre-trained Model. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.00717. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, T.; Wang, D.; Chen, H.; Zeng, Z.; Guo, W.; Miao, C.; Cui, L. BDANN: BERT-Based Domain Adaptation Neural Network for Multi-Modal Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Glasgow, UK, 19–24 July 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Hu, D.; Zhou, W.; Hu, S. Modeling Both Intra- and Inter-Modality Uncertainty for Multimodal Fake News Detection. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 25, 7906–7916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.; Song, X.; Bontcheva, K.; Aletras, N. Examining the limitations of computational rumor detection models trained on static datasets. In Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), Torino, Italy, 20–25 May 2024; pp. 6739–6751. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, Q.; Cao, J.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, J. MDFEND: Multi-domain Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Information & Knowledge Management, Virtual Event, Queensland, Australia, 1–5 November 2021; pp. 3343–3347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, Y.; Lu, W.; Zhao, Z.; Lai, S.; Shi, T. MMDFND: Multi-modal Multi-Domain Fake News Detection. In Proceedings of the 32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, VIC, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1178–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Layer Name | Output Size | 18-Layer | 34-Layer | 50-Layer | 101/152-Layer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| conv1 | , stride 2 | ||||

| max pool, stride 2 | |||||

| conv2.x | |||||

| conv3.x | |||||

| conv4.x | |||||

| conv5.x | |||||

| Average pool, 1000-d fc, softmax | |||||

| FLOPs | - | ||||

| Dataset | News with Images | No. of Real News | No. of Fake News |

|---|---|---|---|

| 9528 | 4779 | 4749 | |

| PHEME | 3670 | 3830 | 1972 |

| Attribute | Hyperparameters |

|---|---|

| Dropout | 0.3 |

| Required improvement | 2000 |

| Num epochs | 100 |

| Batch size | 32 |

| Pad size | 128 |

| Learning rate | |

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Dataset | Model | Accuracy | Fake News | Real News | Macro Avg | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | |||

| EANN | 0.782 | 0.827 | 0.697 | 0.756 | 0.752 | 0.863 | 0.804 | 0.789 | 0.780 | 0.780 | |

| att-RNN | 0.772 | 0.854 | 0.656 | 0.742 | 0.720 | 0.889 | 0.795 | 0.787 | 0.773 | 0.769 | |

| MVAE | 0.824 | 0.854 | 0.769 | 0.809 | 0.802 | 0.875 | 0.837 | 0.828 | 0.822 | 0.823 | |

| CAFE | 0.840 | 0.855 | 0.830 | 0.842 | 0.825 | 0.851 | 0.837 | 0.840 | 0.841 | 0.840 | |

| SAFE | 0.763 | 0.833 | 0.659 | 0.736 | 0.717 | 0.868 | 0.785 | 0.775 | 0.764 | 0.761 | |

| HMCAN | 0.885 | 0.920 | 0.845 | 0.881 | 0.856 | 0.926 | 0.890 | 0.888 | 0.886 | 0.886 | |

| SpotFake | 0.869 | 0.877 | 0.859 | 0.868 | 0.861 | 0.879 | 0.870 | 0.869 | 0.869 | 0.869 | |

| SpotFake+ | 0.870 | 0.887 | 0.849 | 0.868 | 0.855 | 0.892 | 0.873 | 0.871 | 0.871 | 0.871 | |

| FND-CLIP * | 0.882 | 0.930 | 0.828 | 0.876 | 0.842 | 0.936 | 0.886 | 0.886 | 0.882 | 0.881 | |

| MCOT | 0.901 | 0.895 | 0.911 | 0.903 | 0.906 | 0.890 | 0.898 | 0.901 | 0.901 | 0.901 | |

| CA-MFD (Ours) | 0.910 | 0.924 | 0.896 | 0.910 | 0.897 | 0.925 | 0.911 | 0.911 | 0.911 | 0.911 | |

| PHEME | EANN | 0.685 | 0.664 | 0.694 | 0.701 | 0.750 | 0.747 | 0.681 | 0.707 | 0.721 | 0.691 |

| att-RNN | 0.850 | 0.791 | 0.749 | 0.770 | 0.876 | 0.899 | 0.888 | 0.834 | 0.824 | 0.829 | |

| MVAE | 0.852 | 0.806 | 0.719 | 0.760 | 0.871 | 0.917 | 0.893 | 0.839 | 0.818 | 0.827 | |

| CAFE | 0.861 | 0.812 | 0.645 | 0.719 | 0.875 | 0.943 | 0.907 | 0.844 | 0.794 | 0.813 | |

| SAFE | 0.811 | 0.827 | 0.559 | 0.667 | 0.806 | 0.940 | 0.866 | 0.817 | 0.750 | 0.767 | |

| HMCAN | 0.881 | 0.830 | 0.838 | 0.834 | 0.910 | 0.905 | 0.893 | 0.870 | 0.872 | 0.864 | |

| SpotFake | 0.823 | 0.743 | 0.745 | 0.744 | 0.864 | 0.863 | 0.863 | 0.804 | 0.804 | 0.804 | |

| SpotFake+ | 0.800 | 0.730 | 0.668 | 0.697 | 0.832 | 0.869 | 0.850 | 0.781 | 0.769 | 0.774 | |

| FND-CLIP * | 0.812 | 0.852 | 0.891 | 0.871 | 0.694 | 0.615 | 0.652 | 0.773 | 0.753 | 0.762 | |

| MCOT | 0.870 | 0.839 | 0.727 | 0.779 | 0.882 | 0.936 | 0.908 | 0.861 | 0.832 | 0.844 | |

| CA-MFD (Ours) | 0.901 | 0.888 | 0.909 | 0.898 | 0.914 | 0.894 | 0.904 | 0.901 | 0.902 | 0.901 | |

| Dataset | Model | Accuracy (%) | Fake News | Real News | Macro Avg | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | |||

| BERT | 88.99 | 0.9297 | 0.8453 | 0.8855 | 0.8564 | 0.9351 | 0.894 | 0.893 | 0.8902 | 0.8898 | |

| LERT | 89.81 | 0.9128 | 0.8818 | 0.897 | 0.8841 | 0.9146 | 0.8991 | 0.8985 | 0.8982 | 0.8981 | |

| PERT | 87.53 | 0.9057 | 0.8397 | 0.8714 | 0.8486 | 0.9113 | 0.8789 | 0.8772 | 0.8755 | 0.8751 | |

| MiniRBT | 85.81 | 0.8574 | 0.8615 | 0.8595 | 0.8589 | 0.8547 | 0.8568 | 0.8581 | 0.8581 | 0.8581 | |

| T-GPT | 91.03 | 0.9240 | 0.8955 | 0.9095 | 0.8973 | 0.9253 | 0.9111 | 0.9106 | 0.9104 | 0.9103 | |

| PHEME | BERT | 87.09 | 0.8339 | 0.9125 | 0.8714 | 0.9118 | 0.8325 | 0.8704 | 0.8728 | 0.8725 | 0.8709 |

| LERT | 88.90 | 0.8556 | 0.9245 | 0.8887 | 0.9249 | 0.8562 | 0.8893 | 0.8902 | 0.8904 | 0.8890 | |

| PERT | 88.57 | 0.8616 | 0.9074 | 0.8839 | 0.9103 | 0.8657 | 0.8874 | 0.8859 | 0.8865 | 0.8857 | |

| MiniRBT | 78.54 | 0.8015 | 0.7341 | 0.7663 | 0.7727 | 0.8325 | 0.8015 | 0.7871 | 0.7833 | 0.7839 | |

| T-GPT | 90.13 | 0.8878 | 0.9091 | 0.8983 | 0.9144 | 0.8942 | 0.9042 | 0.9011 | 0.9016 | 0.9012 | |

| Dataset | Model | Accuracy | Fake News | Real News | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | |||

| CA-MFD (Image only) | 61.43 | 0.5976 | 0.7166 | 0.6517 | 0.6399 | 0.5107 | 0.5680 | |

| CA-MFD (Text only) | 87.00 | 0.9438 | 0.7787 | 0.8593 | 0.8163 | 0.9524 | 0.8791 | |

| CA-MFD w/o CA | 88.99 | 0.9250 | 0.8501 | 0.8860 | 0.8596 | 0.9302 | 0.8935 | |

| CA-MFD (Con CoAtt) | 85.40 | 0.8802 | 0.8217 | 0.8500 | 0.8308 | 0.8867 | 0.8578 | |

| CA-MFD w/o Contrast | 89.03 | 0.9313 | 0.8445 | 0.8858 | 0.8560 | 0.9368 | 0.8946 | |

| CA-MFD w/o CA&Contrast | 87.77 | 0.9415 | 0.8073 | 0.8692 | 0.8293 | 0.9491 | 0.8851 | |

| CA-MFD | 91.03 | 0.9240 | 0.8955 | 0.9095 | 0.8973 | 0.9253 | 0.9111 | |

| PHEME | CA-MFD (Image only) | 74.75 | 0.5778 | 0.4483 | 0.5049 | 0.7962 | 0.8681 | 0.8306 |

| CA-MFD (Text only) | 82.01 | 0.6757 | 0.7184 | 0.6964 | 0.8836 | 0.8611 | 0.8722 | |

| CA-MFD w/o CA | 89.14 | 0.9005 | 0.8696 | 0.8848 | 0.8836 | 0.9115 | 0.8974 | |

| CA-MFD (Con CoAtt) | 85.03 | 0.8499 | 0.8353 | 0.8426 | 0.8507 | 0.8641 | 0.8574 | |

| CA-MFD w/o Contrast | 89.56 | 0.9207 | 0.8559 | 0.8871 | 0.8754 | 0.9321 | 0.9028 | |

| CA-MFD w/o CA&Contrast | 86.76 | 0.8625 | 0.8611 | 0.8618 | 0.8722 | 0.8736 | 0.8729 | |

| CA-MFD | 90.13 | 0.8878 | 0.9091 | 0.8983 | 0.9144 | 0.8942 | 0.9042 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chi, Z.; Guo, P.; Liu, F. A Compact GPT-Based Multimodal Fake News Detection Model with Context-Aware Fusion. Electronics 2025, 14, 4755. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234755

Chi Z, Guo P, Liu F. A Compact GPT-Based Multimodal Fake News Detection Model with Context-Aware Fusion. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4755. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234755

Chicago/Turabian StyleChi, Zengxiao, Puxin Guo, and Fengming Liu. 2025. "A Compact GPT-Based Multimodal Fake News Detection Model with Context-Aware Fusion" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4755. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234755

APA StyleChi, Z., Guo, P., & Liu, F. (2025). A Compact GPT-Based Multimodal Fake News Detection Model with Context-Aware Fusion. Electronics, 14(23), 4755. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234755