1. Introduction

Underwater wireless sensor networks (UWSNs) are employed for data acquisition, disaster prevention, and navigation [

1,

2]. Given the challenge of battery replacement for nodes on the ocean floor, energy harvesting from vortex-induced vibrations using piezoelectric materials offers an effective solution for powering these sensors. Recent research has explored the conversion of vortex-induced vibration energy into electrical energy, including preliminary analyses and verifications of the underlying mechanisms and collection efficiency. Li et al. [

3] proposed a new type of piezoelectric cantilever beam energy harvester based on vortex-induced vibration. The results verify that when the bluff body is a cylinder with a diameter of 0.02 m and a height of 0.05 m, and the ratio of the distance between the bluff body and the bluff body diameter is 2, the maximum voltage of the T-shaped piezoelectric cantilever energy harvester is 1.02 V. It provides a theoretical and experimental reference for energy collection in the wind. Kamenar et al. [

4] discussed the solution of piezoelectric eels and hybrid turbines coupled with piezoelectric beams. The energy harvester is integrated into an autonomous wireless sensor node under real river conditions. After testing, the energy harvester successfully powered the entire sensor cluster. Abdelkefi [

5] proposed a free resonant cylinder with piezoelectric patches on support rods aligned parallel or perpendicular to the tube’s axis. When water flows perpendicularly to the tube’s axis, vortex-induced vibrations cause transverse resonance, driving bending in the piezoelectric patches for energy conversion. Li et al. [

6] developed a flexible circular tube energy harvester with an integrated piezoelectric beam, addressing sealing and corrosion issues. Laboratory tests of a 0.03 m diameter and 0.05 m height prototype yielded 1.46 mW power at 30.9 Hz and 1 MΩ resistance, with a water flow velocity of 1.1 m/s. Rong et al. [

7] proposed a nested piezoelectric ring energy harvesting structure based on vortex-induced vibration. The result of the experimental test verifies that when the distance between the rigid bluff body and the energy harvesting structure is 0.07 m, the maximum voltage peak is 4.869 V. Jin et al. [

8] proposed a piezoelectric energy harvester with a wavy cylinder with pits and hemispherical protrusions. Especially for the 5-column pit structure of 10 mm, the peak voltage can reach 47 V, the peak power can reach 1.21 mW, and the resistance is 800 kΩ, which is 0.57 mW higher than that of the wavy cylinder. Shi et al. [

9] developed a hydrodynamic piezoelectric energy harvester inspired by fishtails, utilizing a forced separation topological vortex. The harvester with an elliptic cylinder (aspect ratio 2.5) achieved an output voltage of 38.4 V at 0.45 m/s water velocity, 21.5 times higher than a circular cylinder. Zhao et al. [

10] proposed a system composed of an elastically supported wavy cylinder and a tuned mass damper (TMD) to improve energy harvesting efficiency. The results indicate that when the wavelength λz is greater than or equal to 3.6 times the diameter of the wave column (Dm), the performance of the corrugated column is better than that of the wavy cylinder, and reaches a peak at λz = 6.0 Dm and amplitude a = 0.25 Dm, which is increased by 70%. Shah [

11] designed a series of cylindrical and piezoelectric thin films, systematically analyzed the influence of structural spacing on power generation performance, and found the optimal configuration. At a flow rate of 0.34 m/s and a spacing of 3 times the diameter of the cylinder, the power reaches 19.17 µW.

Current research on piezoelectric vibration energy harvesting predominantly utilizes

d33 and

d31 modes; however,

d15 mode has been shown to produce higher output power, A comparative analysis of the three primary piezoelectric modes, detailed in

Table 1. For instance, Ren et al. [

12] compared a PMN-PT cantilever harvester using shear mode (

d15) with one using thickness mode (

d31). Despite being only half the volume of the

d31 harvester, the

d15 device generates 8.3 times the output voltage and approximately 7 times the maximum output power. Malakooti [

13,

14] showed that

d15 mode provides better impedance-frequency response than

d31 mode for PZT piezoelectric cantilever beams, with significant variations in maximum output power across frequencies and impedances. Using Timoshenko beam theory, they developed a model indicating that shear mode harvesters generate about 50% more power than those in transverse modes. The exploration of

d15 mode with higher electrical constants and better suitability for underwater shear stress environment is still absent. In addition, existing designs mostly focus on unidirectional energy capture and fail to fully utilize the bidirectional vibration characteristics.

Based on this, this paper proposes a shear mode bidirectional piezoelectric energy harvesting structure based on underwater vortex-induced vibration and conducts numerical simulation to explore the vibration performance and piezoelectric characteristics of the energy harvesting structure under different conditions. The potential applications of this technology extend beyond powering static UWSN nodes. It could be deployed for long-term ocean monitoring tasks, such as providing power for sensors on autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), profiling floats, or mounting on underwater infrastructure for structural health monitoring, contributing to the development of self-powered systems in marine science and engineering.

2. Materials and Methods

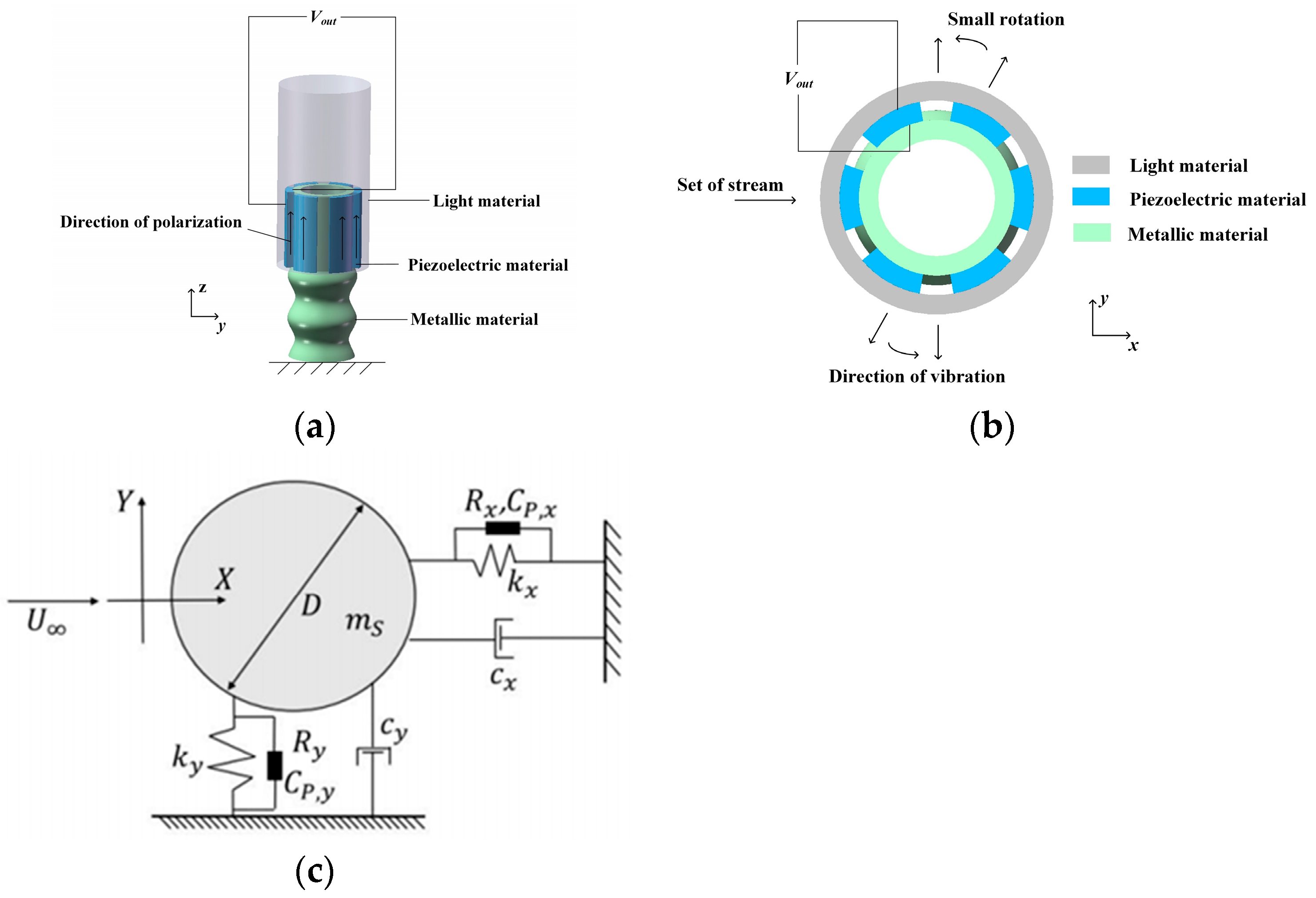

Figure 1a,b depict a bidirectional piezoelectric energy harvesting structure that operates in shear mode. This design harnesses vortex-induced vibrations of a tube to apply shear strain to a piezoelectric material, which is positioned between the tube and its support structure, thereby generating electrical charge. The high shear electromechanical coupling coefficient of the piezoelectric material facilitates efficient conversion of vibrational energy in both transverse and downstream directions into electrical energy, thereby improving energy conversion efficiency and expanding the operational bandwidth. Additionally, the piezoelectric material’s resilience to significant shear strain enhances its durability and extends its service life.

The bidirectional shear mode vortex-induced vibration piezoelectric energy harvester can be regarded as two independent piezoelectric energy harvesting systems in the transverse and downstream directions. The simplified electromechanical model is shown in

Figure 1c. From the diagram, it can be seen that the flow direction is the x-axis direction; the tube is free vibration in the y direction;

U∞ is the flow velocity;

D is the diameter of the tube;

ms is the mass of the tube;

ky and

cy are the elastic stiffness and equivalent damping in the transverse direction;

kx and

cx are the elastic stiffness and equivalent damping in the downstream direction; and

Rx,

Ry,

Cp,x,

Cp,y are the equivalent resistance and capacitance in two directions, respectively. Then, there is the following [

15]:

Equations (1) and (3) are the linear oscillator equations for the vibration of an elastically supported tube in the x and y directions, respectively, where mf denotes the potential added mass of the fluid; X and Y denote the displacement in x and y directions, respectively; t denotes the time; θx and θy denote the electromechanical coupling constant; ρ denotes the fluid density; L denotes the length of tube; Vx and Vy denote the electric tension; and Cx;v and Cy;v denote the force coefficient caused by the vortex shedding. Equations (2) and (4) are the wave characteristics of a vortex-induced vibration cylinder wake which satisfy the equation of van der Pol nonlinear oscillator, where ωf is the vortex shedding frequency, , St is the Strouhal number; qx, qy represent wake variables; and εx, Ax, Ay, εy represent the parameters of the wake oscillator model. When the right side of (2) and (4) is 0, that is, the vibration frequency of the energy harvesting structure is equal to the vortex shedding frequency, the limit cycle periodic solution of the amplitude is obtained.

The working mechanism of different modes of the piezoelectric sheet [

16]:

Equation (8) is the expression of the electromechanical relationship between piezoelectric materials. Under the condition of a certain external force, the electric displacement changes linearly with stress. Among them, {D} is the electric displacement tensor; [d] is the piezoelectric strain constant; and {T} is the stress tensor.

We use

T,

W,

L to represent the length, width, and height of the piezoelectric material, respectively; then, the bottom area

S = L ×

W.

P represents the polarization direction, the field strength is

E, and the voltage is

V. Then, there is

Combining the above equations, we can obtain

Again

,

, there is

Among them, ε represents the dielectric constant, d represents the piezoelectric constant, and d is different under different vibration conditions. Commonly used modes include d15, d31, and d33; the subscript next to the letter represents the polarization direction, and the second subscript represents the deformation direction. However, the piezoelectric constants of typical piezoelectric materials have the relationship d15 > d33 > d31. It can be seen from Equation (15) that the output voltage of piezoelectric materials working in d15 mode is higher than that of piezoelectric materials working in d33 and d31 modes.

According to Reference [

17], there is an optimal load, which can maximize the output power of the energy harvesting structure, and the expression of the optimal load resistance is

Among them,

and

represent the natural frequency. It can be seen from Equation (16) that the optimal load of the energy harvesting structure is only related to the natural frequency and internal capacitance of the structure itself. Therefore, after the natural frequency of the energy harvesting structure is determined, the optimal load resistance is also determined. The parameters in

Table 1 are substituted into Equation (16), and the optimal load resistance is 1 MΩ. Therefore, the load resistance of 1 MΩ is connected in tandem in this experiment.

The total electric power equation is

In order to simplify the calculation, the dimensionless parameters are defined:

The total energy harvesting efficiency is obtained as follows:

where

denotes the dimensionless fluid velocity,

fn,y = 0.62 Hz;

m* indicates structural mass, where

md represents the mass of fluid displaced by the cylinder;

Ca denotes the additional mass of dimensionless fluid; and

and

represents the dimensionless electrical tension in two directions, respectively.

The coupled fluid–solid–piezoelectric simulation is governed by the following sets of equations:

Fluid Domain: The fluid flow is described by the incompressible Navier–Stokes equations, which govern the conservation of mass and momentum:

where

u is the fluid velocity vector,

p is the pressure,

ρ is the fluid density, and

v is the kinematic viscosity.

Solid and Piezoelectric Domain: The piezoelectric material behavior is governed by the linear constitutive relations, which couple the mechanical and electrical fields:

where {

T} and {

S} are the stress and strain tensors, {

D} and {

E} are the electric displacement and electric field vectors, [

cE] is the elasticity matrix at constant electric field, [

e] is the piezoelectric stress coefficient matrix, and [

εS] is the dielectric permittivity matrix at constant strain.

3. Results and Discussion

According to the theoretical model of the shear mode bidirectional piezoelectric energy harvesting structure based on underwater vortex-induced vibration proposed in the previous section, the finite element analysis is used to simulate the fluid–solid coupling and piezoelectric coupling of the energy harvesting structure, respectively [

18]. The vibration characteristics and output voltage are obtained, which proves the feasibility of the structure. A comparison of output voltage across three piezoelectric modes indicated that shear mode offers the highest power generation efficiency. On this basis, the optimal performance parameters are determined by changing the thickness of the piezoelectric sheet, the shape of the support, the flow velocity, the shape of the bluff body and

L/

D. In addition, by observing the changes in the flow field and the output voltage, the performance of the dual energy harvesting structure with tandem-parallel configuration in the fluid domain is analyzed.

Finite element simulation of the model based on ANSYS, mesh strategy: The fluid domain adopts a 5 mm tetrahedral mesh; In the solid domain, the piezoelectric sheet adopts a 1 mm regular hexahedral mesh, while the rest adopts a 2 mm regular tetrahedral mesh.

Boundary conditions: Select ‘Velocity Inlet’ as the inlet of the fluid domain, set the velocity as needed, and select ‘Pressure Outlet’ as the outlet and set it to 0; the boundary of the solid domain adopts fixed constraints; set one side of the piezoelectric material to zero voltage and the other side to the terminal.

3.1. Performance of Single Energy Harvester

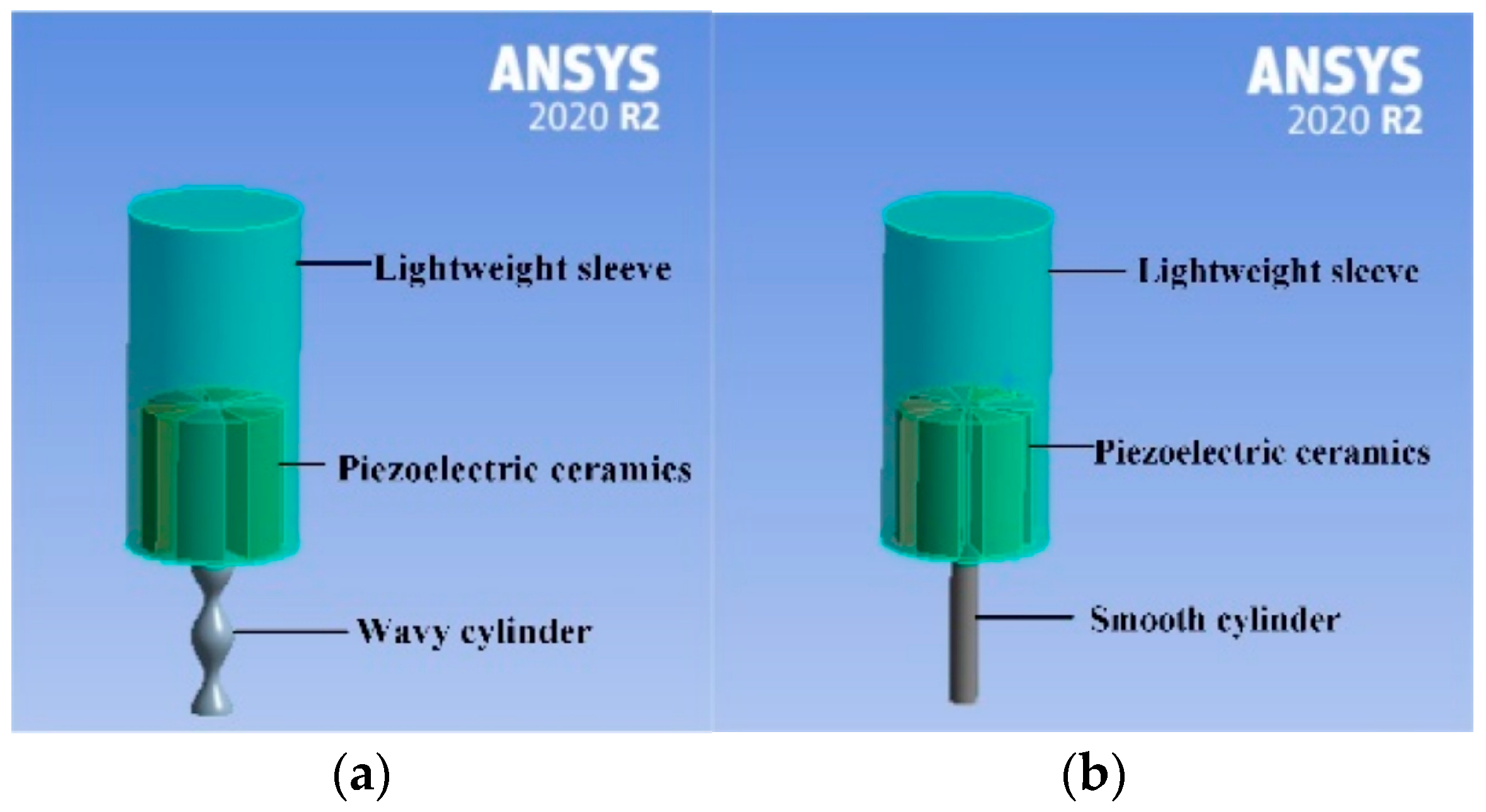

The numerical simulation analysis of single energy harvesting structure is completed. The three-dimensional geometric model is shown in

Figure 2a. The specific parameters of the energy harvesting structure are shown in

Table 2.

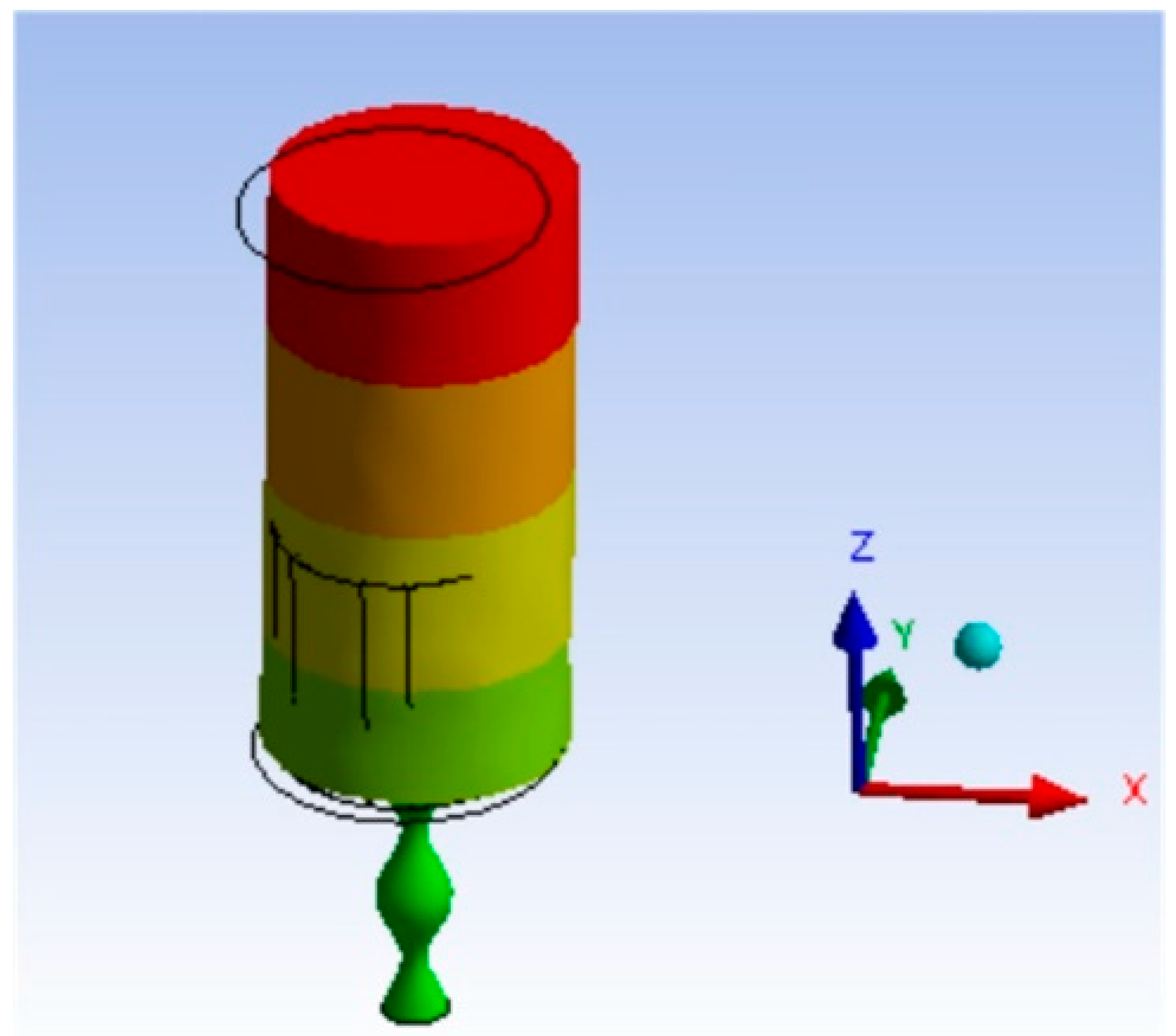

The trajectory of the piezoelectric energy harvesting structure in the fluid domain is shown in

Figure 3. The black contour represents the original position of the energy harvesting structure. Compared with the current position, it is found that the energy harvesting structure is subjected to both the drag force in the downstream direction and the vortex lift force in the transverse direction. Vibration is generated in two directions, and its vibration form is reciprocating vibration in the transverse direction, accompanied by a small rotation in the downstream direction.

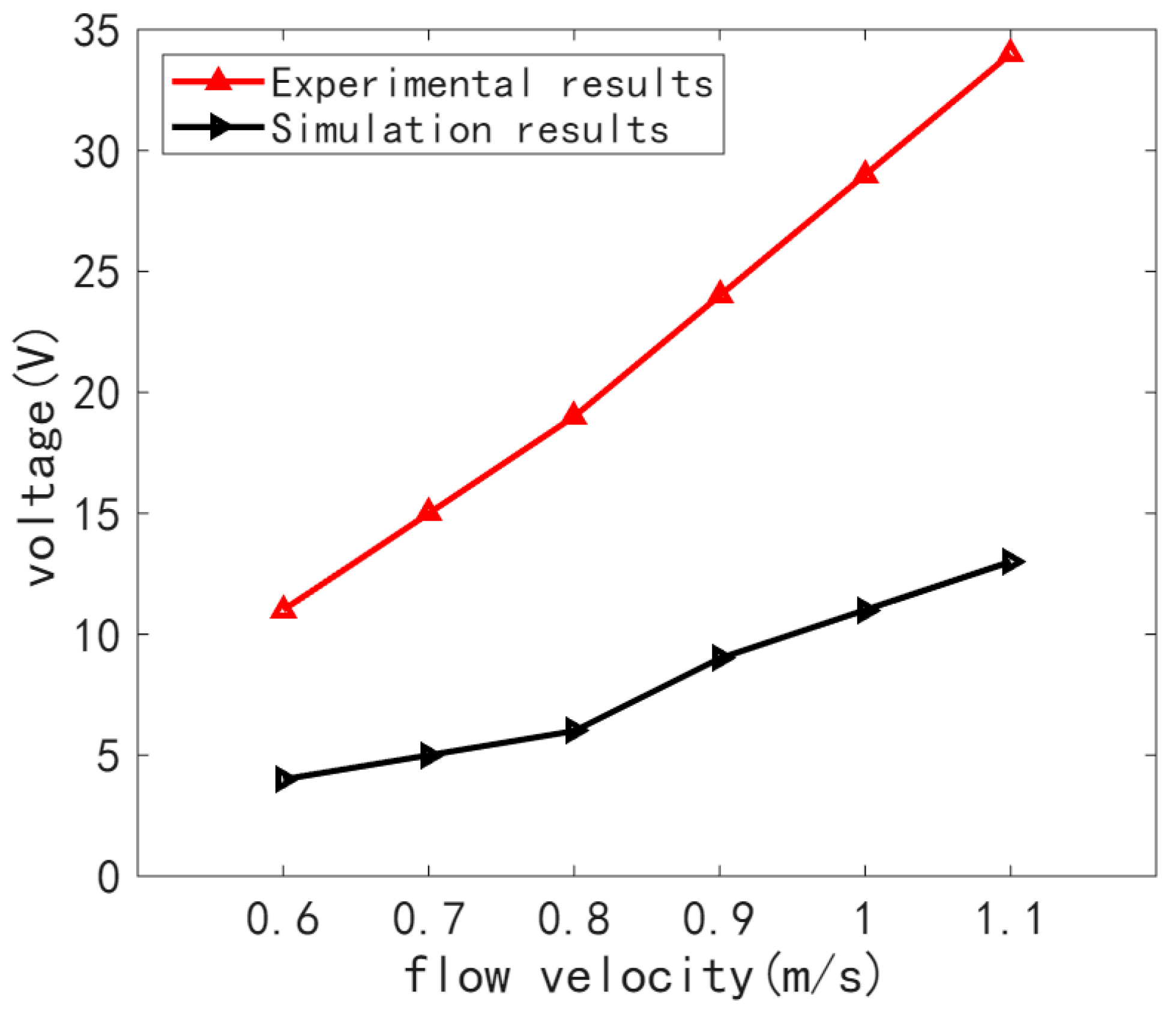

3.1.1. The Influence of Piezoelectric Mode on the Energy Harvesting Structure

Figure 4 shows the variation curves of the output voltage of the three piezoelectric modes with flow velocity. It can be seen from the diagram that the output voltage under different piezoelectric modes increases with the increase in the flow velocity. When the velocity is the same, the voltage of

d15 is the largest, followed by

d33, and the worst is the

d31. When the velocity is 1.1 m/s and the piezoelectric mode is in shear mode (

d15), the voltage generated by the energy harvesting structure is the largest, and the voltage amplitude is 34.88 V.

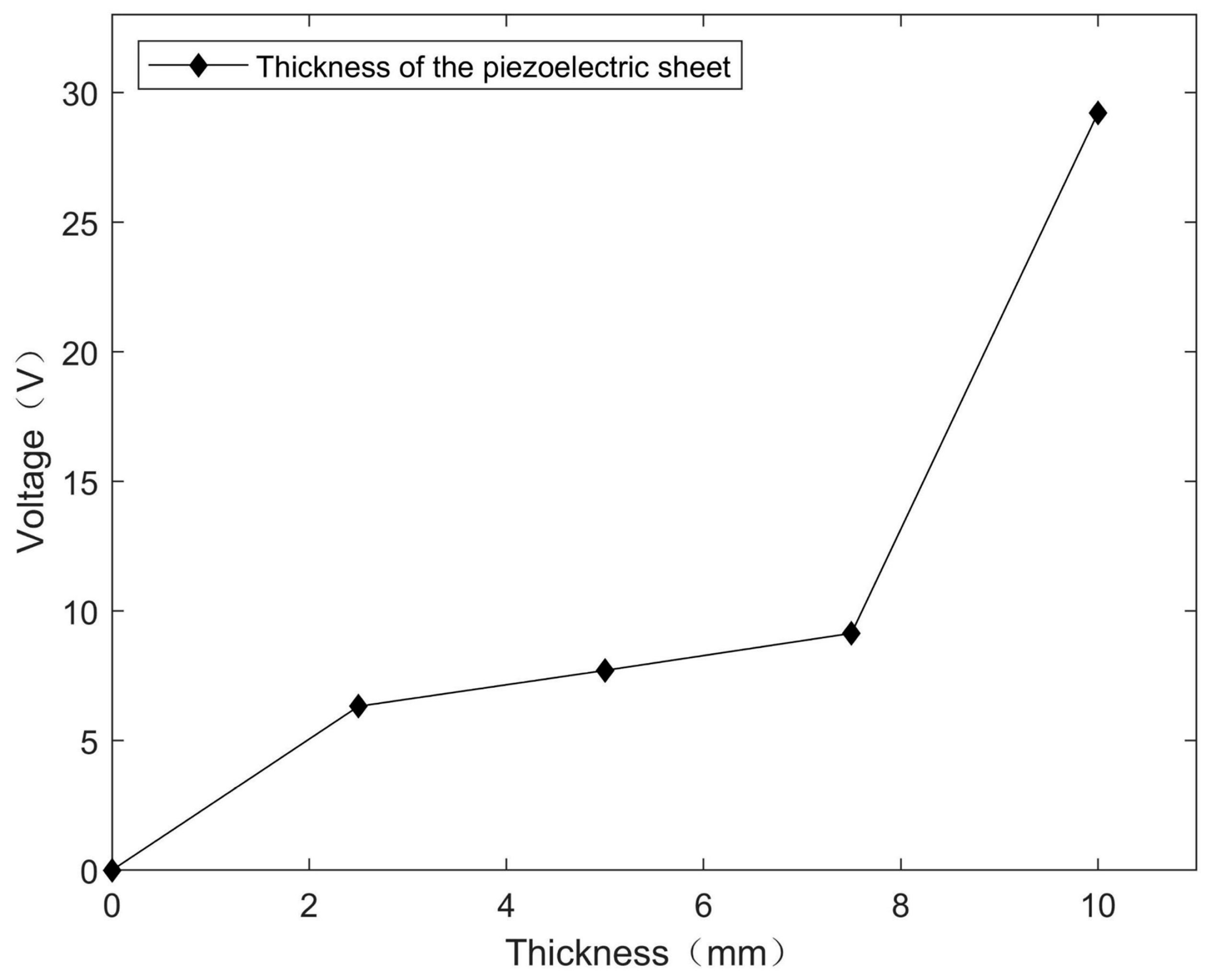

3.1.2. The Influence of the Thickness of the Piezoelectric Sheet and the Support Shape

Figure 5 is the voltage change curve with the thickness of the piezoelectric sheet when the velocity is 1 m/s and the piezoelectric sheet working on the shear mode. From the diagram, it can be seen that the output voltage of the energy harvesting structure increases with the increase in the thickness of the piezoelectric sheet, reaching 29.21 V at 0.01 m.

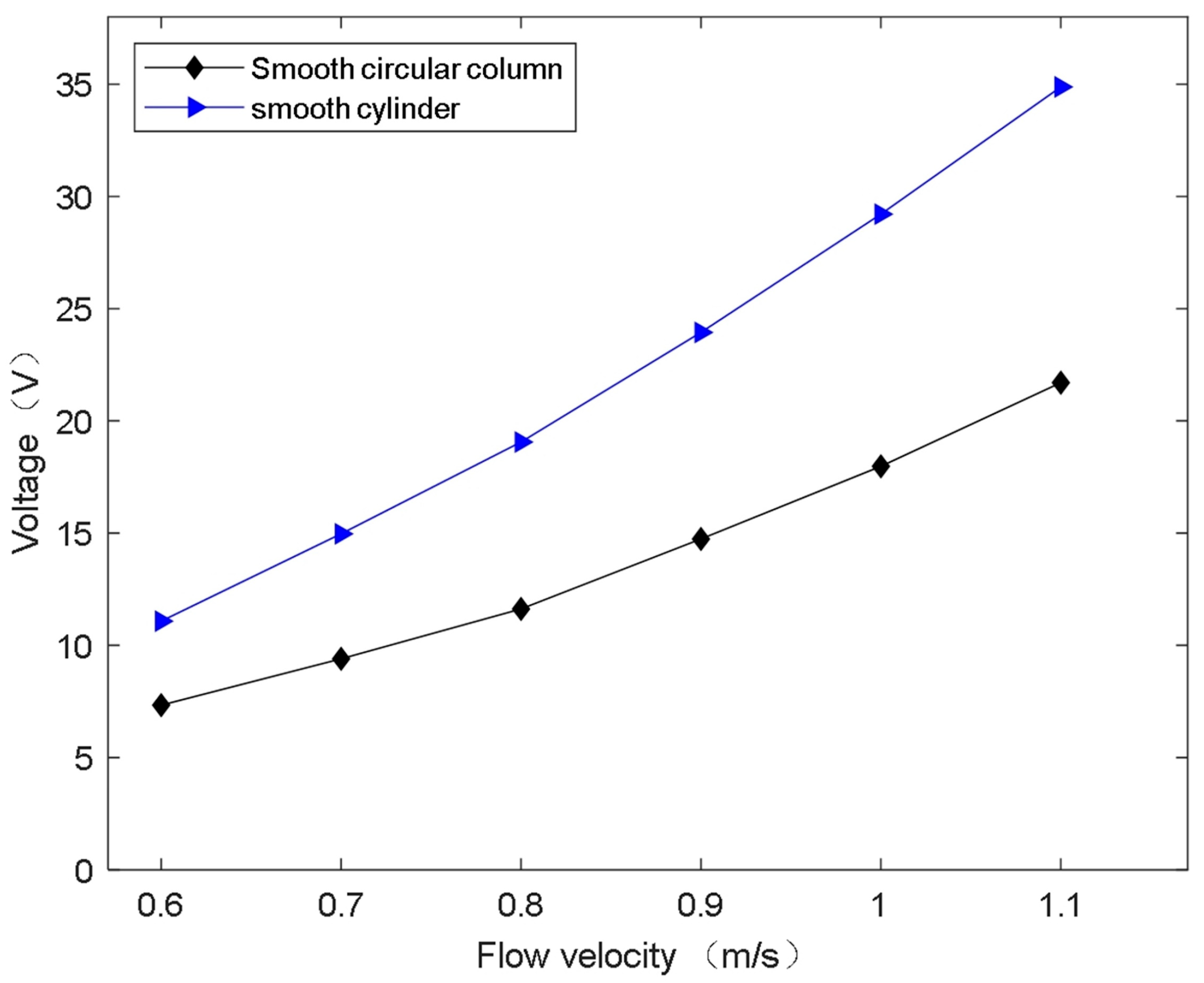

Figure 6 shows the voltage response of different supports as flow velocity varies. Using a piezoelectric sheet with a thickness of 0.01 m, the supports are either smooth or wavy cylinders, and the flow velocity ranges from 0.6 to 1.1 m/s. The results indicate that voltage increases with flow velocity, and for the same velocity, the wavy cylinder support generates higher voltage than the smooth cylinder support.

3.1.3. The Influence of Bluff Body and L/D Ratio

L is the distance between the bluff body and the center of energy harvesting structure, and the

L/

D is set to 2. The three-dimensional geometric model is shown in

Figure 7a. The amplitude response variation law obtained by numerical simulation is shown in

Figure 7b.

It can be seen from

Figure 7b. The structural amplitude increases with the increase in the velocity. At low velocities, a long low-speed zone forms behind the bluff body, resulting in low energy density and minimal input energy, with most energy used for damping, thus small amplitude. As velocity increases, energy density rises, and the input energy surpasses damping losses, leading to larger amplitude vibrations.

When the flow velocity is the same, the amplitude of the energy harvesting structure supported by wavy cylinder is larger than that by smooth cylinder. This is because when the bluff body is a wavy cylinder, hairpin vortices are formed on both sides of the wavy cylinder. Under the action of the hairpin vortex, a wider wake can be formed, and a larger force is generated on the energy harvesting structure, which increases the relative displacement between the two tubes, drives the piezoelectric sheets sandwiched in the middle to vibrate, and further produces a larger output voltage. When the flow velocity is 1.1 m/s and the bluff body is a wavy cylinder, the maximum amplitude generated by the energy harvesting structure is 1.72 × 10−4 m.

Figure 7c shows that the voltage of the structure behind different-shaped bluff bodies increases with flow velocity. When the bluff body is a wavy cylinder, the voltage is greater than that of the smooth cylinder. At a flow velocity of 1.1 m/s and the bluff body is a wavy cylinder, the voltage generated by the energy harvesting structure is the largest, the voltage amplitude is 56.97 V, corresponding to an output power of 3.25 mW according to Equation (17).

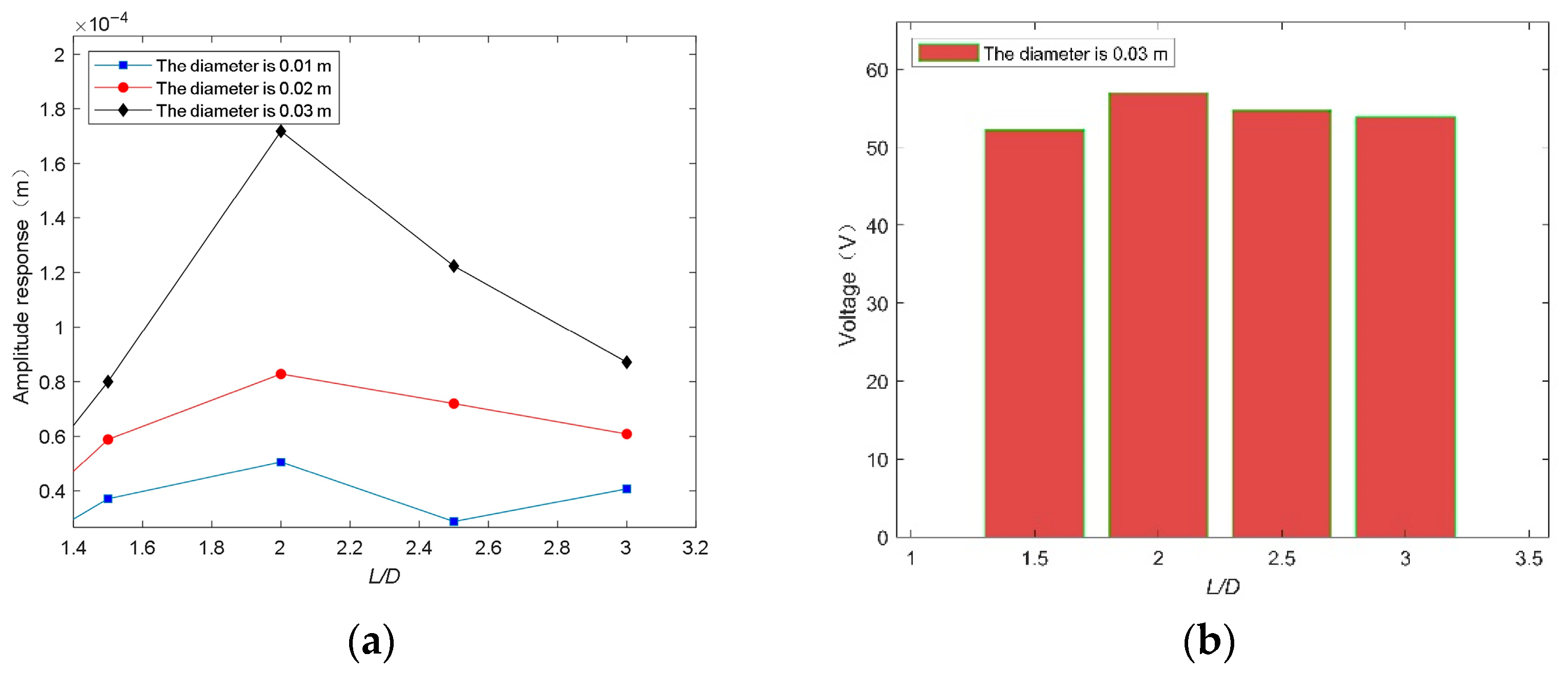

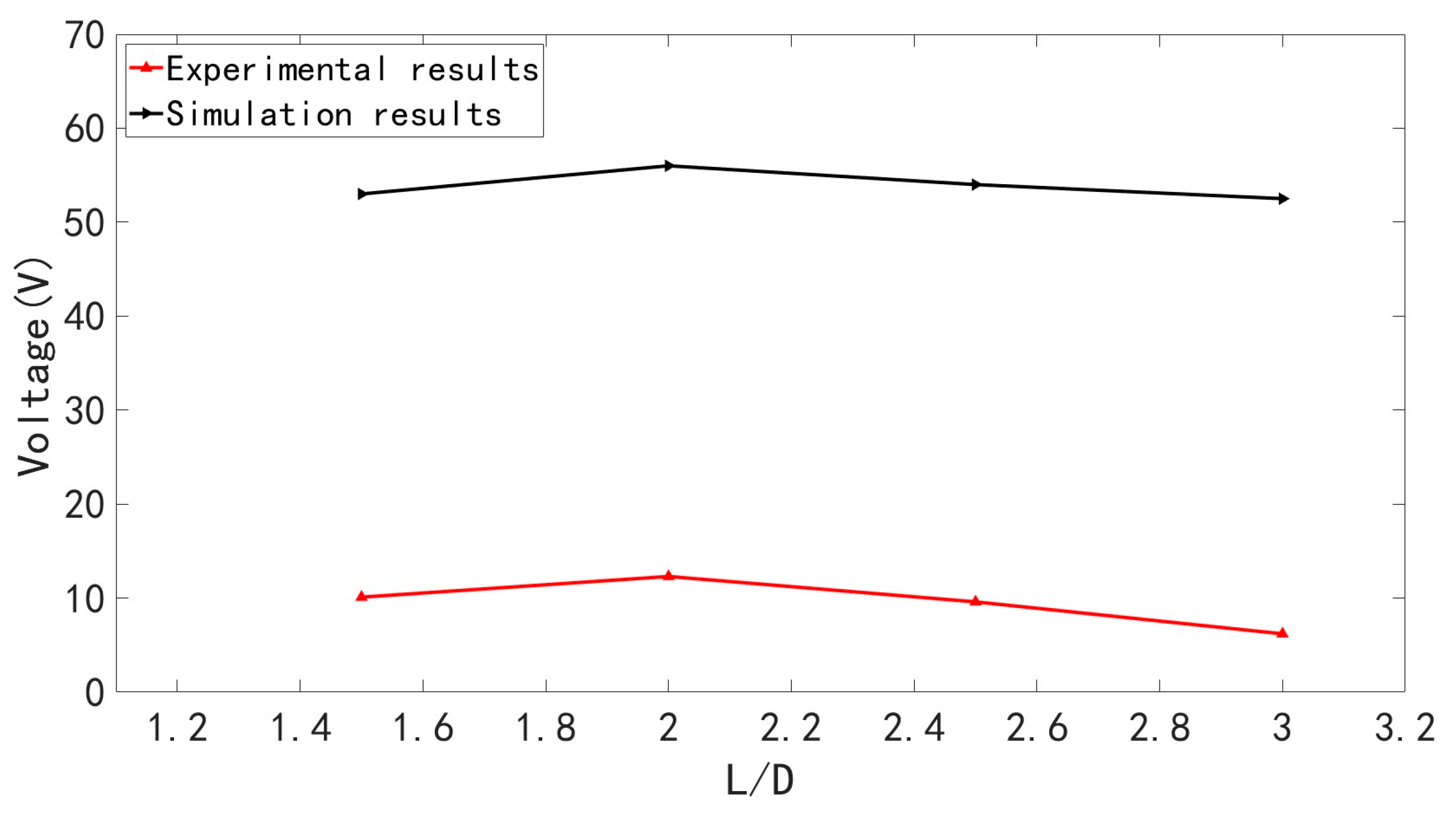

In the next part, the flow velocity is selected to be 1.1 m/s, and the diameters of the bluff body are changed to 0.01, 0.02, 0.03 m, respectively. The

L/

D is from 1.5 to 3, and the increment is 0.5. The influence of the three groups of bluff body on the amplitude is compared by simulation. The amplitude response and voltage of the energy harvesting structure is shown in

Figure 8.

It can be seen from

Figure 8a that when

L/

D is 2 and the diameter of the bluff body is 0.03 m, the maximum displacement amplitude of the energy harvesting structure is 1.72 × 10

−4 m.

Figure 8b is the voltage amplitude curve obtained by piezoelectric coupling simulation. It can be seen that the voltage response curve has similar changes corresponding with the displacement. The

L/

D has a certain influence on the performance of the piezoelectric energy harvesting device. Therefore, choosing a reasonable

L/

D will be more conducive to improving the output voltage of the energy harvesting structure.

3.1.4. Resonance Frequency Analysis

The energy harvesting efficiency is significantly enhanced when the vortex shedding frequency synchronizes with the natural frequency of the harvester structure. The vortex shedding frequency

fv can be estimated by the Strouhal number

St:

where

U is the flow velocity and

D is the characteristic diameter of the bluff body. For the wavy cylinder bluff body with

D = 30 mm at

U = 1.1 m/s, and assuming

St = 0.2,

fv = 7.33 Hz.

The natural frequency of the proposed harvester structure, obtained from modal analysis, was found to be fn = 7.5 Hz. The close proximity between fv and fn explains the peak performance observed in our simulations. This frequency matching is crucial for maximizing the power generation of piezoelectric energy harvesters.

3.2. Performance of Dual Energy Harvester Array Configurations

3.2.1. Tandem Energy Harvesting Structure

Two energy harvesting structures with the same parameters are placed in tandem in the flow field. Under the action of fluid, the two energy harvesting structures generate vibration and output voltage, respectively. The energy harvesting structure near the inlet of the flow field is called the upstream structure, and the other is called the downstream structure. Taking the L/D as 2, the flow velocity is changed to 0.6–1.1 m/s, and the amplitude and voltage changes in the two energy harvesting structures are analyzed.

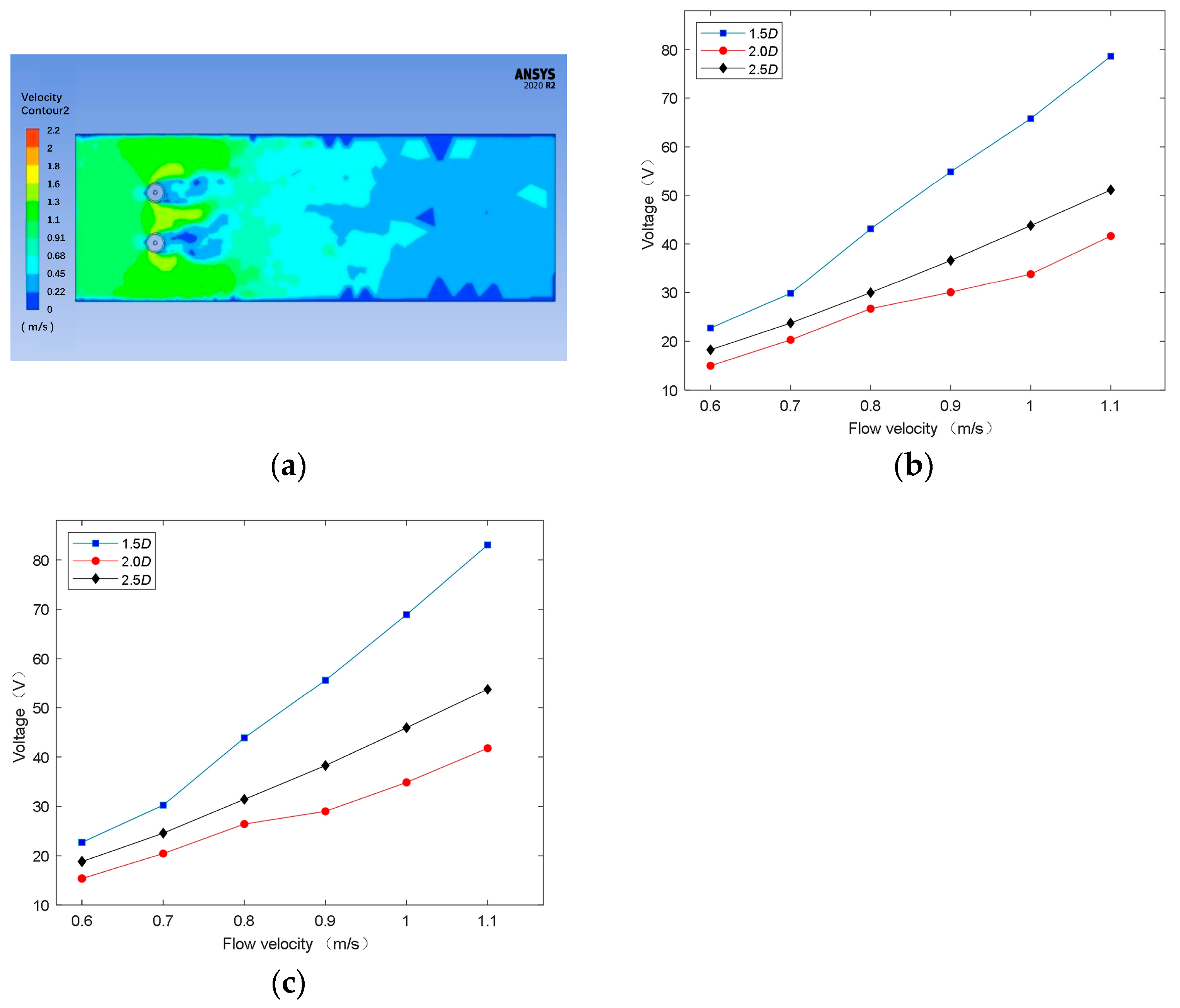

Figure 9a shows the velocity distributions of the fluid domain when the inlet velocity is 1.1 m/s and the

L/

D is 2. At this time, the vortex shedding from the upstream energy harvesting structure acts on the downstream structure, affecting its force and vibration amplitude.

Figure 9b,c are the vibration displacement of the upstream and downstream energy harvesting structure, respectively. The downstream structure is simultaneously subjected to the coupling effect between itself and the fluid, and the vortex shedding generated by the upstream structure. The superposition of the two vibration forms leads to the continuous change in its force, and the amplitude is much larger than the amplitude generated by the upstream energy harvesting structure.

From

Figure 9d, it can be seen that the voltage generated by the downstream structure is greater than that generated by the upstream structure too. At 1.1 m/s of the velocity, the maximum output voltage of the upstream and downstream are 36.62 V and 48.95 V, respectively. According to Equation (17), the corresponding output power values are 1.34 mW and 2.40 mW, respectively.

From the comparison of

Figure 8b and

Figure 9d, it can be seen that the upstream and downstream energy harvesters of the double-structure tandem can convert the mechanical energy of the water flow into electrical energy, and then more electrical energy can be obtained.

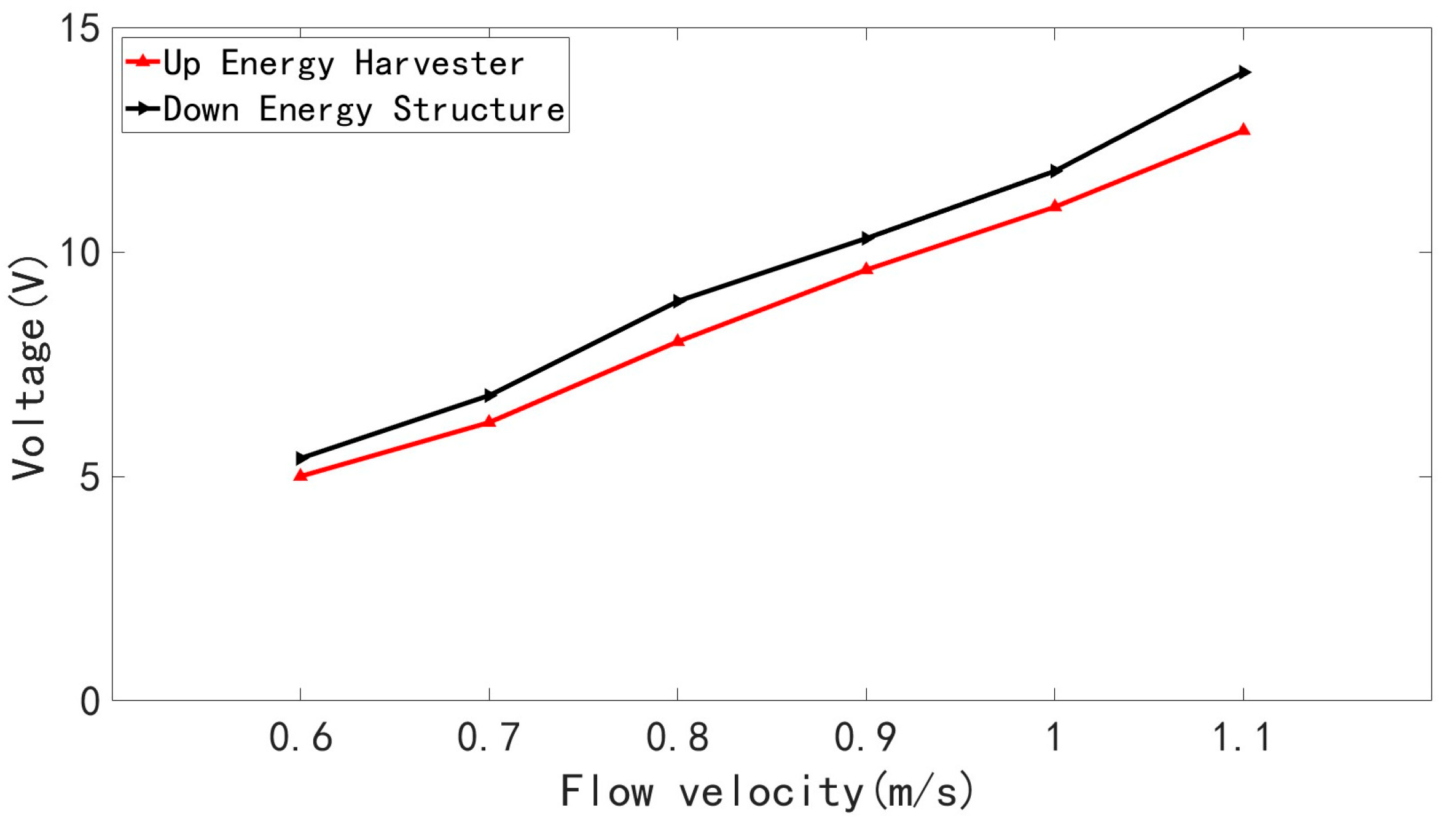

3.2.2. The Parallel Energy Harvesting Structures

Two energy harvesting structures identical to the previous section are placed in parallel in the fluid domain. The energy harvester is called the upper energy harvesting structure in the top-down order, and the latter is the lower energy harvesting structure. The spacing between the upper and lower structures is adjusted to make L/D to be 1.5, 2, 2.5, respectively, and the amplitude response and power of the two energy harvesting structures are studied in the range of fluid velocity of 0.6–1.1 m/s.

Figure 10a shows the velocity distributions of the double parallel energy harvesting structure with a flow velocity of 1.1 m/s and

L/D of 2.5. From the diagram, it can be seen that the vortexes behind the two energy harvesting structures move independently of each other.

From

Figure 10b,c, it can be seen that the voltage generated by the upper and lower of the double parallel energy harvesting structure increases with the increase in L/

D value. When

L/

D is 1.5 and the velocity is 1.1 m/s, the output voltage of the upper and lower structure reaches the peak values of 78.65 V and 83.05 V, respectively. According to Equation (17), the output power values are 6.19 mW and 6.90 mW, respectively. This is because when the distance between the two energy harvesting structures is small, the area of the fluid domain is small, resulting in an increase in the pressure difference, which in turn increases the vortex-induced force, accelerates the vibration of the two energy harvesting structures, and generates large amplitude and voltage. The simulations verify that the change in the

L/

D has a certain influence on the performance of the piezoelectric energy harvester. Therefore, choosing a reasonable

L/

D will be more conducive to improving the output voltage of the energy harvesting structure.

Table 3 provides the power density of various energy harvesting structures at a flow velocity of 1.1 m/s. The area of each piezoelectric sheet is 0.6 cm

3, and the energy harvesting structure uses six piezoelectric sheets with a total volume of 2.4 cm

3.

4. Experiments

To further validate the performance of the piezoelectric energy harvesting structure, this chapter will described the test that were conducted within a water circulation system. Firstly, the piezoelectric energy harvester was fabricated according to the simulation conditions, and the experimental platform is set up. Subsequently, experimental tests were carried out on a harvester with an upstream bluff body, and dual harvesters in both tandem and parallel configurations. The influence of parameters such as flow velocity, bluff body shape and size, and spacing ratio on the piezoelectric performance was investigated to determine the conditions for optimal power generation performance, thereby further exploring the feasibility of using the piezoelectric energy harvesting structure to power low-energy consumption electronic devices.

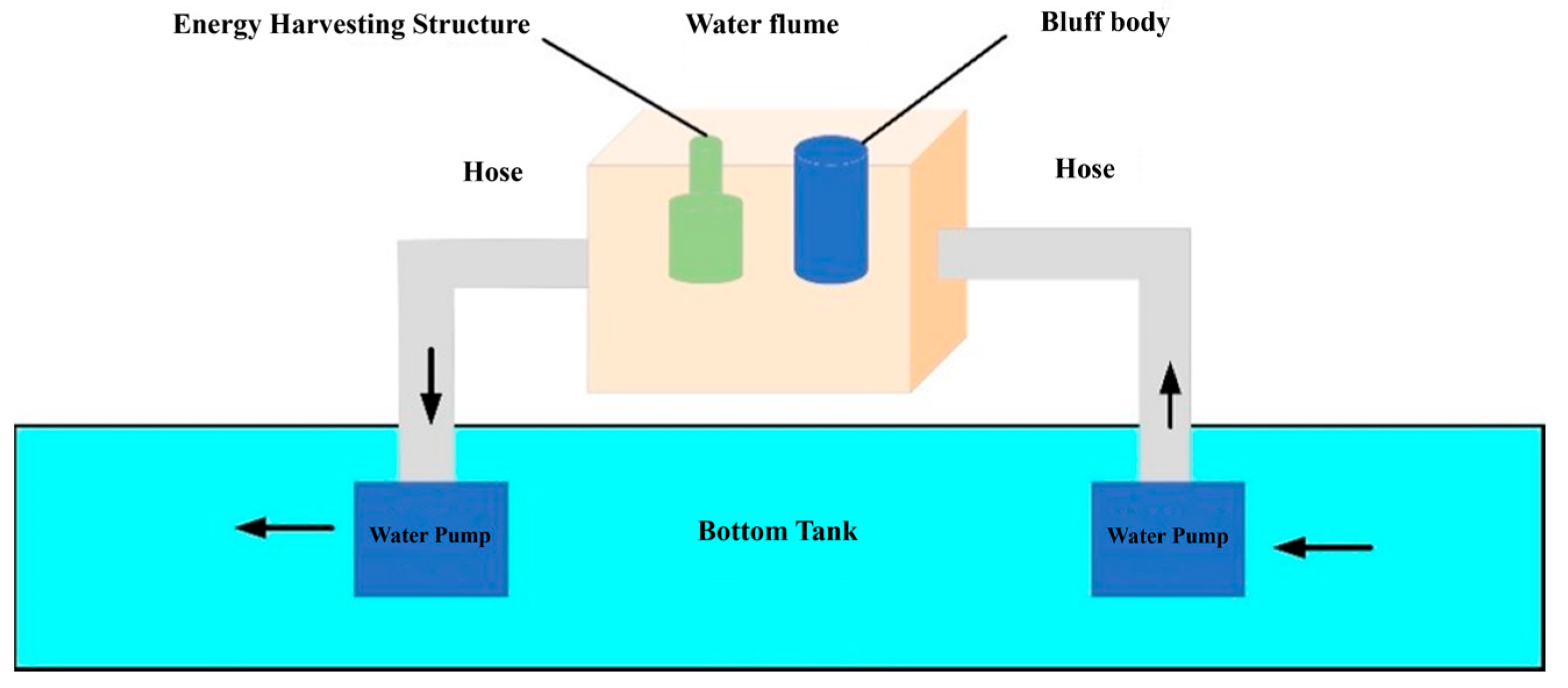

4.1. Design and Setup of the Experimental System

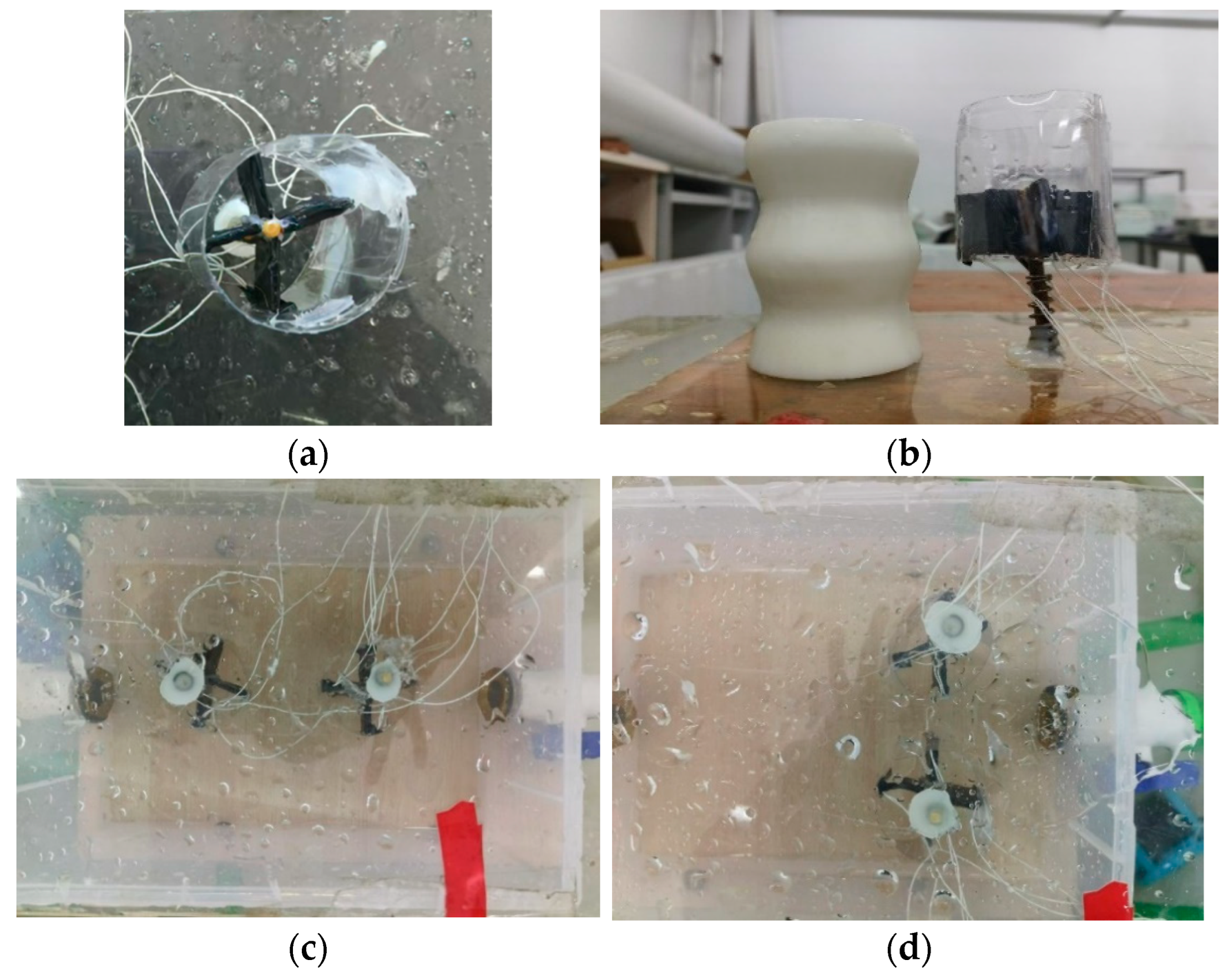

To test the energy harvesting structure in water flow, a water circulation experimental system was designed, as shown in

Figure 11. This system mainly consists of a bottom water tank, an experimental water channel, a submersible pump, a digital oscilloscope, and a computer, forming a closed-loop water circulation experimental platform.

Based on the design requirements of the experimental platform, the water circulation experimental platform was set up. The specific experimental devices are shown in

Figure 12.

4.2. Experiment of Single Energy Harvester

To further analyze factors affecting the power generation performance of the piezoelectric energy harvester, a bluff body was placed upstream of the harvester. Based on the numerical simulation conclusion that the optimal spacing between the harvester and the upstream bluff body is 2D, the bluff body was positioned accordingly.

In the experiment, the flow velocity range was set from 0.6 m/s to 1.1 m/s, with an increment of 0.1 m/s. The output voltage of the harvester in series with the bluff body was systematically measured under these six different flow velocities. Based on this data, the curve shown in

Figure 13 was plotted and compared with the simulation results.

Figure 13 shows the voltage variation trend of the energy harvester with an upstream bluff body at different flow velocities. It can be observed that as the flow velocity increases, the output voltage of the single harvester with an upstream bluff body shows a growing trend, consistent with the simulation results, reaching a maximum value of 12.4 V at 1.1 m/s. This is because the influence of the upstream bluff body on the harvester gradually strengthens with increasing flow velocity. The vortex shedding state of the fluid causes deformation of the piezoelectric material in the harvester, thereby generating voltage.

To investigate the influence of the spacing ratio L/D on the power generation performance when using a wavy cylinder as the bluff body. Based on the simulation conclusion that the wavy cylinder is one of the most effective bluff body shapes under known conditions, experiments were continued to validate and refine this conclusion.

In the experiment, the key parameters of the piezoelectric energy harvester remained unchanged to ensure the comparability of results under identical conditions. Specifically, the wavy cylindrical bluff body and the piezoelectric energy harvester were arranged in a tandem configuration at a flow velocity of 1.1 m/s. The

L/

D ratio was then gradually adjusted from 1.5 to 3, increasing by 0.5 each time, to observe the voltage output of the harvester under different settings. The results are shown in

Figure 14.

The output voltage of the harvester initially increases and then decreases with increasing L/D, a phenomenon consistent with the numerical simulation results. When L/D < 1.5, the distance between the bluff body and the harvester is small, causing them to be perceived as a single entity, resulting in the formation of only one vortex street, and consequently, a relatively low output voltage under this condition. As the L/D value increases from 1.5 to 2.5, vortices appearing in-phase and anti-phase alternately emerge on both sides of the bluff body, known as the “coupled vortex street” state, which can generate a higher output voltage.

4.3. Experiment of Dual Energy Harvester Array Configurations

To further investigate the power generation performance of piezoelectric energy harvesters in a tandem configuration, two harvesters with identical parameters were placed sequentially in the experimental water channel for testing. The flow velocity was maintained constant at 1.1 m/s throughout the experiment. The results are shown in

Figure 15.

Comparative analysis clearly verifies that under the same conditions, the output voltage variation trend of the tandem dual-harvester structure is consistent with the numerical simulation results. For the same type of harvester, the voltage generated by the downstream harvester is significantly higher than that generated by the upstream harvester.

Two piezoelectric energy harvesters with identical parameters were arranged in parallel in the experimental water channel. Based on the optimal configuration scheme determined from prior simulation results,

L/

D was set to 1.5. The flow velocity range was adjusted from 0.6 m/s to 1.1 m/s to investigate the output voltage of each harvester under different flow velocity conditions. The results are shown in

Figure 16.

The results verify that the voltage values of both the upper and lower energy harvesters have a steady upward trend with the increase in water flow velocity. At a flow velocity of 1.1 m/s, the output voltage of the two energy harvesting structures reaches its maximum value, as shown in the numerical simulation results.