1. Introduction

The modern power grid, a vast and interconnected infrastructure of transmission lines and substations, demands exceptional reliability amid increasing climate variability and aging equipment [

1,

2]. Routine maintenance now relies heavily on unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) patrols that capture high-resolution images of critical components, complemented by textual inspection logs documenting on-site observations. Automating anomaly detection, identifying issues such as insulator fractures, conductor corrosion, or foreign object intrusions—through the fusion of visual and linguistic data can prevent cascading failures that may incur billions in losses annually. However, achieving precise semantic alignment between raw imagery and descriptive text remains a formidable challenge. Environmental variations can obscure subtle irregularities, while inspection logs differ in length, vocabulary, and specificity. In recent years, a broad spectrum of deep learning techniques has been applied to both multimodal fusion [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8] and other learning-based applications [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15], demonstrating the growing potential of cross-modal intelligence for industrial inspection and automation.

Foundational vision-language models such as CLIP [

16] have revolutionized zero-shot learning by jointly embedding massive image-text corpora [

17]. Yet, CLIP’s global scale contrastive learning—aligning entire images to short captions—struggles in fine-grained anomaly detection scenarios within the power domain. Defects in this context often occupy only a few pixels amid complex visual backgrounds, causing crucial cues such as pitting depth or micro-crack texture to be overlooked. These limitations arise from both architectural constraints (e.g., a 77-token cap) and the model’s insufficient ability to discriminate between semantically similar yet operationally distinct states, resulting in a high false-negative rate.

To overcome these challenges, recent research has focused on improving fine-grained alignment capabilities. Approaches such as detail-oriented prompting [

18] and region-based contrastive learning [

19] have shown that precise visual-language correspondence requires specialized training strategies capable of directing the model’s attention toward subtle, localized visual cues. Nevertheless, most existing efforts remain generic and lack domain-specific adaptation. In particular, a unified training curriculum that jointly integrates long-caption comprehension and fine-grained discrimination against visually similar power-domain distractors has yet to be established.

To fill this gap, we present VisPower, a curriculum-guided multimodal alignment framework built upon the standard CLIP backbone, explicitly designed to enhance fine-grained perception for power equipment inspection and maintenance. The proposed curriculum first constructs a robust global semantic foundation and then progressively refines local feature discrimination. Specifically, our framework consists of (1) a Semantic Grounding (SG) stage that performs global alignment on a large-scale corpus of 100 K long-caption pairs to establish contextual grounding and (2) a Contrastive Refinement (CR) stage that leverages 24 K annotated region-text pairs and 12 K synthesized hard negatives to sharpen the model’s ability to distinguish subtle anomalies. Trained on our curated PowerAnomalyVL dataset, this method achieves an 18.4% absolute uplift in zero-shot image-text retrieval accuracy compared with strong CLIP-based baselines.

Our main contributions are summarized as follows:

We propose VisPower, a vision-language framework featuring a two-stage curriculum-guided training paradigm tailored for fine-grained anomaly perception and defect discrimination in power operations.

We introduce a progressive learning pipeline: Stage 1 performs robust long-text semantic grounding, while Stage 2 applies region-level supervision and 12 K synthesized hard-negative samples to reinforce discrimination of subtle defects.

We curate the PowerAnomalyVL Dataset, a privacy-compliant and high-quality benchmark emphasizing semantic diversity and defect precision for multimodal alignment research in power maintenance.

We demonstrate state-of-the-art performance, achieving an 18.4% absolute improvement in zero-shot image–text retrieval Recall@1, establishing a strong new baseline for reliable and accurate anomaly perception.

2. Related Work

2.1. Fine-Grained Vision-Language Enhancements

Contrastive Language-Image Pre-training (CLIP) [

16] has set a benchmark for vision-language tasks, but its global alignment strategy limits its performance on fine-grained tasks that require nuanced, localized understanding [

19,

20,

21,

22]. To address this, a significant body of work has emerged to enhance granularity. One line of research focuses on improving regional feature representation. For instance, DetailCLIP [

18] utilizes detail-oriented prompting, while FineCLIP [

19] employs self-distillation on region-based crops to refine sub-image alignments. Another direction aims to extend CLIP’s text comprehension for longer, more descriptive inputs. Models like FineLIP [

23] and LongCLIP [

22] incorporate extended positional encodings to process inputs exceeding 200 tokens, boosting performance on long-caption retrieval tasks.

Collectively, these works establish that moving beyond global alignment toward region-focused and multi-stage training is essential for fine-grained tasks. However, they are typically designed for general-domain benchmarks and lack mechanisms to handle the specific semantic ambiguities found in industrial inspection, such as distinguishing corrosion from shadows. Our VisPower framework builds on these principles by proposing a progressive curriculum that not only focuses on regions but also introduces domain-specific hard negatives to resolve such ambiguities.

2.2. Anomaly Detection with CLIP Adaptations

CLIP’s zero-shot capabilities have been widely adapted for industrial anomaly detection. A prominent approach involves using text prompts to guide the model. AA-CLIP [

24], for example, injects anomaly-aware negative textual cues to sharpen decision boundaries on benchmarks like MVTec AD [

25]. Other methods, such as

[

26], fuse perceptual queries to reduce false positives in unsupervised inspections. Another synergistic approach combines CLIP with generative models; for instance, some works [

27] use diffusion-based inpainting to synthesize anomaly masks, outperforming purely reconstructive models in localization tasks.

In the context of power grids, CLIP integrations are emerging but remain fragmented [

28,

29,

30]. Researchers have applied CLIP within continual learning frameworks to track evolving faults like insulator degradation [

31,

32] or within semantic networks to prioritize substation defects [

33]. While powerful, these adaptations often rely on generic prompting or lack a structured mechanism for distinguishing between highly similar but semantically distinct states. VisPower extends these ideas by creating a dedicated training stage that explicitly forces the model to learn the subtle visual differences defined by power-domain ontologies, using curated hard negatives for robust, query-driven reporting.

3. Methods

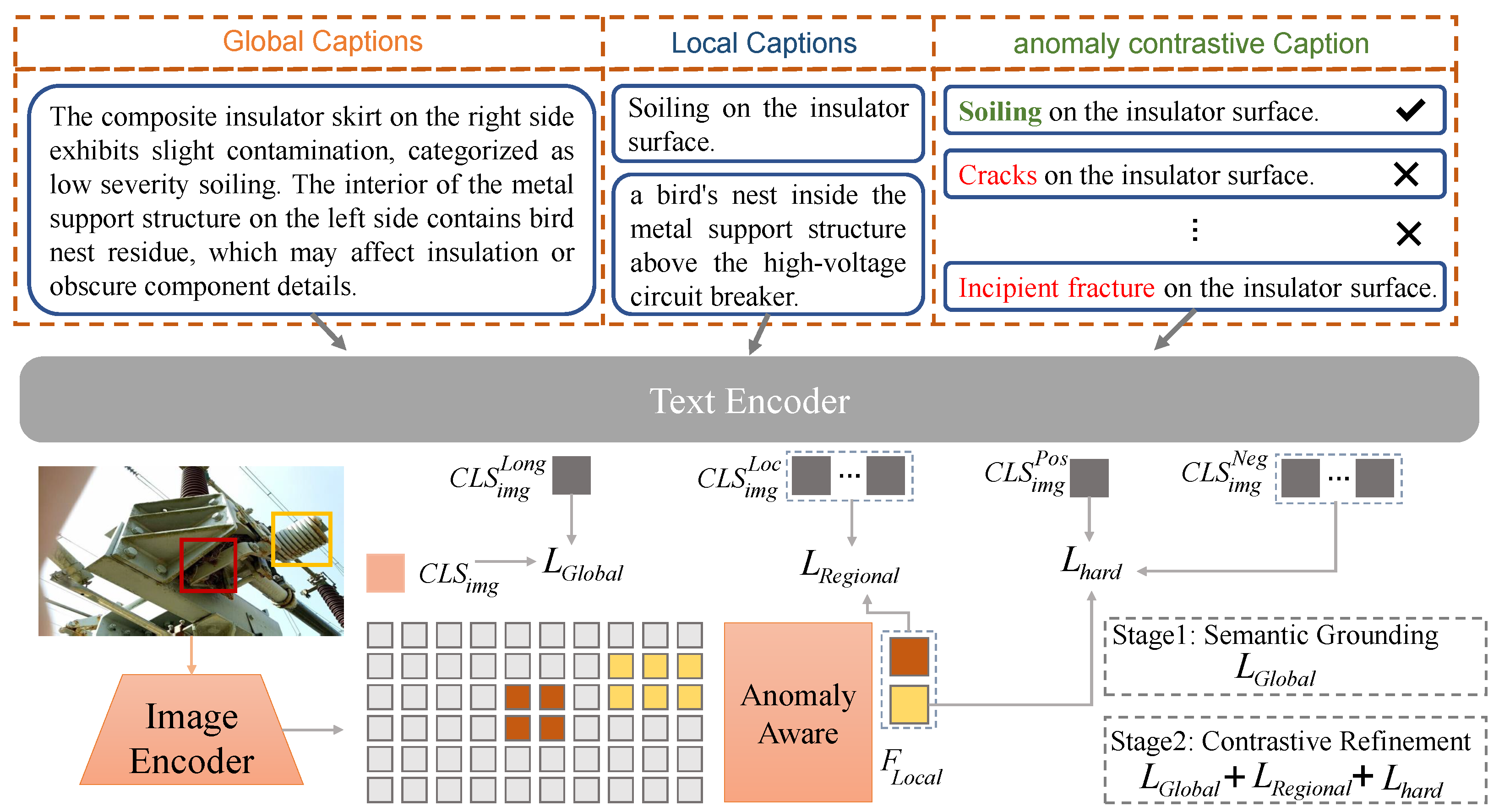

3.1. Overview of VisPower

VisPower adopts a standard CLIP-style dual-encoder architecture composed of a ViT-B/16 image encoder and a Transformer-based text encoder [

16]. The central innovation lies in a two-stage curriculum-guided contrastive training framework that progressively refines the joint vision-language embedding space, enhancing its capacity to capture fine-grained and domain-specific visual semantics. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the model first establishes a semantically rich alignment through long-text grounding and then performs localized refinement to enhance discriminative power for subtle anomalies. This design explicitly targets the unique challenge of matching minute visual patterns with complex, descriptive inspection language in the power operation domain.

For any normalized embedding vectors

u and

v, the cross-modal similarity is computed using cosine similarity:

The two-stage curriculum employs three complementary contrastive objectives—global, regional, and hard-negative losses—that collectively shape a coherent yet discriminative multimodal representation.

3.2. Two-Stage Curriculum-Guided Training

3.2.1. Stage 1: Semantic Grounding (SG)

The first stage aims to construct a semantically grounded embedding space capable of handling detailed and domain-rich textual descriptions common in inspection reports. We pretrain the model on

100 K long-caption image–text pairs, using global contrastive learning to align entire images with detailed textual narratives. To overcome the 77-token constraint of the original CLIP, we extend positional encodings following [

23], enabling effective modeling of up to 256-token captions. The training objective is the symmetric Global InfoNCE loss

, which enforces bidirectional consistency between global visual representations

and textual embeddings

:

where

here,

N denotes the batch size,

is the learnable temperature, and

,

correspond to pooled [CLS] embeddings for vision and text modalities, respectively. This stage serves as a curriculum foundation, ensuring that the model captures detailed contextual semantics before engaging in region-level discrimination.

3.2.2. Stage 2: Contrastive Refinement (CR)

The second stage enhances fine-grained discrimination through region-level supervision and hard-negative contrastive learning. We employ

24 K curated training pairs, consisting of

12 K annotated region–text pairs and

12 K synthesized hard negatives. This stage builds upon the global knowledge from Stage 1 while refining feature boundaries for subtle defect differentiation. The total loss function is defined as:

where

and

are balancing coefficients for the regional and hard-negative components.

3.2.3. Regional Feature Alignment ()

To explicitly guide the model toward localized semantic correspondence, we utilize defect bounding boxes to extract region-level visual features (

) via RoI pooling from the ViT backbone. These are paired with the corresponding local textual descriptions (

). The regional alignment loss follows a symmetric InfoNCE form:

with

where

K is the number of region-level samples per batch. This component teaches the model to associate specific defect regions—such as corroded joints or insulator cracks—with precise textual descriptors.

3.2.4. Hard-Negative Contrastive Enhancement ()

To mitigate semantic confusion between visually similar defect types, we incorporate a hard-negative contrastive term focused on the region-to-text direction. For each region

, there exists one positive caption

and

visually similar but semantically distinct negative captions

. The hard-negative loss is formulated as

This formulation drives the model to pull together embeddings of correct region–text pairs while aggressively pushing apart false associations (e.g., “rusted surface” vs. “dust-covered surface”), thereby reinforcing fine-grained anomaly perception.

3.3. PowerAnomalyVL Dataset Construction and Curation

The PowerAnomalyVL dataset underpins both stages of training, providing diverse visual conditions and fine-grained defect patterns relevant to power equipment inspection. It contains approximately 200 K vision–language pairs derived from 80 K collected inspection images, including 100 K long-caption pairs for Stage 1 and 24 K region-level and hard-negative pairs for Stage 2.

Acquisition and Filtering: Images are collected from real inspection scenarios and filtered to retain samples covering subtle, ambiguous, and visually similar defect types.

Annotation and Verification: Text descriptions and region annotations are created by trained annotators following internal guidelines. Consistency is verified through cross-checking to ensure defect terminology and labeling correctness.

Hard-Negative Construction: From 8 K verified defect annotations, we generate 12 K synthetic hard-negative captions using domain-specific attribute perturbation (e.g., material mismatch, severity flipping, or incorrect component references) to strengthen the model’s discriminative capability.

This curation process ensures that PowerAnomalyVL provides rich fine-grained variation while maintaining the annotation quality required for reliable multimodal alignment.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

To rigorously evaluate the effectiveness of VisPower’s curriculum-guided multimodal alignment, we design experiments across two core tasks: zero-shot image–text retrieval and open-vocabulary defect detection (OV-DD). These tasks directly assess two essential capabilities, namely (1) fine-grained semantic discrimination between visually similar anomalies and (2) generalization to unseen defect categories during grid inspection—key requirements for practical power operation scenarios.

4.1.1. Dataset

All evaluations are performed on a dedicated benchmark subset of the PowerAnomalyVL dataset. The overview of the PowerAnomalyVL dataset as showed in

Figure 2. We select

field-captured inspection images spanning

fine-grained defect categories, emphasizing three key challenges: Subtle Defects, Hard Negatives, and Complex Environments (

Table 1). The model is trained using the full

100 K long-caption corpus (Stage 1: Semantic Grounding) and

24 K regional and contrastive pairs (Stage 2: Contrastive Refinement). To ensure a strict zero-shot setup, category names used during evaluation do not appear in any training captions or region-level annotations; only natural-language descriptions are seen during training. Train/val/test splits are created to avoid identical or near-duplicate images across partitions. Hard negatives are constructed from manually verified region annotations (8 K) and synthetically generated textual negatives (12 K) through domain-specific attribute flipping and synonym/antonym substitution. Results are reported exclusively on the zero-shot benchmark subset and its corresponding defect detection annotations.

4.1.2. Baselines

We compare VisPower with a set of state-of-the-art vision–language models and anomaly-oriented CLIP variants. The baselines include the foundational CLIP [

16] (ViT-B/16), and advanced domain adaptation or fine-grained variants such as AdaptCLIP [

34], AA-CLIP [

24], and FineLIP [

23]. For the open-vocabulary defect detection task, we follow a unified pipeline by adapting all visual encoders (including VisPower) into a consistent detection head, isolating the effect of representation learning. We also include RegionCLIP [

35] as a strong open-vocabulary detection baseline.

4.1.3. Implementation Details

All experiments are implemented in PyTorch (2.1.0). VisPower employs a ViT-B/16 backbone for vision and a Transformer text encoder whose positional embeddings are extended from 77 to 256 tokens via interpolation, following the long-text extension strategy used in LongCLIP [

22]. For region-level grounding and open-vocabulary detection, we follow the design paradigm of RegionCLIP [

35], using a unified two-stage region encoder and detection head built on top of ViT patch tokens; bounding boxes are mapped to the ViT grid using the same feature-grid alignment strategy as FG-CLIP.

Training follows a two-stage protocol. Stage 1 (Semantic Grounding) performs end-to-end contrastive learning on the 100 K long-caption corpus to stabilize global alignment, while Stage 2 (Contrastive Refinement) fine-tunes the visual backbone and region-level head on 24 K region/hard-negative pairs, freezing the text encoder to prevent language drift. Both stages use the AdamW optimizer with different learning rates. Stage 1 adopts a base learning rate of to stabilize global semantic grounding on long captions, while Stage 2 uses a smaller learning rate ( for the visual backbone and for the lightweight region-level head) to avoid disrupting the pretrained alignment during refinement. Weight decay is set to and the batch size to 256 in both stages. Positive/negative assignment and post-processing follow standard open-vocabulary detection practice used in FG-CLIP (IoU-based matching and NMS with a 0.5 threshold).

4.2. Main Results: Zero-Shot Image–Text Retrieval

Table 2 summarizes the zero-shot image–text retrieval results on the PowerAnomalyVL benchmark. Following standard practice in fine-grained vision–language alignment (e.g., FG-CLIP), we adopt Recall@1 (R@1) as the primary retrieval metric. R@1 measures whether the correct image is ranked in the top position for a given text query, providing a direct indicator of fine-grained matching quality.

VisPower achieves an overall R@1 of 81.1%, an 18.4% absolute improvement over the CLIP baseline (62.7%). This demonstrates that the proposed curriculum combining Stage 1 Semantic Grounding with Stage 2 Contrastive Refinement substantially enhances the model’s ability to resolve subtle visual-textual discrepancies across power equipment anomaly scenarios.

To further assess robustness across anomaly types, we report category-level R@1 grouped by the five high-level categories defined in PowerAnomalyVL. As shown in

Table 2, VisPower yields consistent gains across all categories, indicating that both global semantic grounding and regional refinement generalize effectively to diverse operational conditions.

4.3. Open-Vocabulary Defect Detection (OV-DD)

To evaluate spatial grounding and localization ability, we test VisPower on open-vocabulary defect detection using the same 2 K benchmark subset, as shown in

Table 3 Each model must localize defect regions using only text queries of unseen anomaly types. Following standard COCO-style OV-detection practice, we report mAP (IoU 0.50–0.95), AP

50, and additionally AP

75 for a stricter localization evaluation.

VisPower achieves substantial improvements across all metrics, improving mAP by and AP75 by over RegionCLIP. The gains demonstrate the effectiveness of Stage 2’s region-level grounding and hard-negative refinement in enhancing spatial precision, particularly for subtle defects that require fine-grained localization.

4.4. Ablation Studies and Analysis

We perform systematic ablation experiments to examine the contribution of each component in the curriculum. As shown in

Table 4, removing either stage or the hard-negative term causes notable performance degradation, confirming their complementary roles in achieving fine-grained multimodal alignment.

Without Contrastive Refinement (Stage 2): Training solely with Stage 1 yields 66.8% R@1, indicating that global semantic grounding alone is insufficient to resolve the subtle distinctions between similar anomalies. The 14.3% drop underscores the necessity of region-level supervision and hard-negative reasoning for precise anomaly perception.

Without Hard Negatives: Excluding the 12 K synthesized hard negatives results in an 8.0% decrease (73.1% R@1), revealing the importance of in reinforcing semantic boundaries between near-duplicate defect types.

Without Semantic Grounding (Stage 1): Training solely on Stage 2’s 24 K regional pairs achieves 71.5% R@1 (−9.6%), reflecting insufficient generalization without the large-scale textual grounding from Stage 1. This verifies that Stage 1 provides essential contextual understanding that enables Stage 2’s regional refinement to achieve optimal discriminability.

Together, these results confirm that VisPower’s curriculum-guided training paradigm effectively integrates broad semantic grounding and fine-grained contrastive refinement, forming a unified framework for accurate and robust power anomaly perception.

5. Conclusions

We presented VisPower, a curriculum-guided vision–language framework designed to advance fine-grained anomaly perception in power operation and maintenance. The core innovation lies in a robust two-stage contrastive training paradigm that progressively enhances multimodal alignment—from global Semantic Grounding to localized Contrastive Refinement. This curriculum enables VisPower to bridge large-scale contextual understanding with precise regional discrimination, effectively capturing subtle differences between anomalous and normal power components. In particular, the incorporation of 24 K region-level and synthesized hard-negative samples in the second stage substantially improves the model’s ability to distinguish visually similar defects under complex environmental conditions. Evaluated on the challenging PowerAnomalyVL benchmark, VisPower achieves state-of-the-art results, surpassing strong CLIP-based baselines by an 18.4% absolute gain in zero-shot retrieval accuracy.

While VisPower achieves strong performance, it may be sensitive to domain shifts such as changes in device appearance or imaging conditions. In addition, the fine-grained regional annotations used in Stage 2 introduce a moderate annotation cost. In future work, we plan to extend VisPower toward multi-sensor fusion and temporal reasoning across sequential inspection data, enabling more robust and scalable anomaly perception in real-world power systems.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.C., H.Y., Y.Y. and J.D.; Methodology, Z.C., H.Y., Y.Y. and J.D.; Software, Z.C., H.Y. and J.D.; Validation, Z.C., H.Y. and S.Z.; Formal analysis, Z.C., H.Y. and S.Z.; Investigation, Z.C., Y.Y. and S.Z.; Data curation, Z.C. and J.D.; Writing—original draft, Z.C., Y.Y. and H.Y.; Writing—review & editing, Z.C., Y.Y. and J.D.; Visualization, Z.C., H.Y. and J.D.; Supervision, J.D.; Project administration, H.Y. and J.D.; Funding acquisition, Z.C., H.Y. and J.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Science and Technology Project of the State Grid Corporation Headquarters (Grant No. 5700-202490330A-2-1-ZX).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article; further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the editorial board and reviewers for their support in improving this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors Zhenyu Chen, Huaguang Yan and Jianguang Du were employed by the company Information and Telecommunication Center, State Grid Corporation of China. Author Shuai Zhao was employed by the company Information and Communication Branch, State Grid Zhejiang Electric Power Co., Ltd. The authors declare that this study received funding from State Grid Corporation Headquarters. The funder was not involved in the study design; collection, analysis, or interpretation of data; the writing of this article; or the decision to submit it for publication.

References

- Mishra, D.P.; Ray, P. Fault detection, location and classification of a transmission line. Neural Comput. Appl. 2018, 30, 1377–1424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Panigrahi, B.; Maheshwari, R. Transmission line fault detection and classification. In Proceedings of the 2011 International Conference on Emerging Trends in Electrical and Computer Technology, Nagercoil, India, 23–24 March 2011; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 15–22. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Pi, H.; Li, R.; Qin, Y.; Tang, Z.; Li, K. VLScene: Vision-Language Guidance Distillation for Camera-Based 3D Semantic Scene Completion. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Pennsylvania, PA, USA, 25 February–4 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 7808–7816. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, B.; Wei, J. Deep learning to hash with application to cross-view nearest neighbor search. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 3882–3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gao, X.; Wu, M.; Lam, S.K.; He, S.; Tiwari, P. Looking Clearer with Text: A Hierarchical Context Blending Network for Occluded Person Re-Identification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 4296–4307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, C.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Z. I-adapt: Using iou adapter to improve pseudo labels in cross-domain object detection. In Proceedings of the ECAI 2024, Santiago de Compostela, Spain, 19–24 October 2024; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2024; pp. 57–64. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Li, Z.; Shi, H.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, P. Scribble-Supervised Video Object Segmentation via Scribble Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 2999–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Zhou, S.; Yu, H.; Li, C.; Hu, X. SCESS-Net: Semantic consistency enhancement and segment selection network for audio-visual event localization. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2025, 262, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Wu, Q.; Li, M.; Xiahou, K. Detection of false data injection attacks on power systems using graph edge-conditioned convolutional networks. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2023, 8, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zeng, T.; Liu, Z.; Xie, L.; Xi, L.; Ma, H. Automatic generation control in a distributed power grid based on multi-step reinforcement learning. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 9, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cao, R.; Wang, R. Learning discriminative topological structure information representation for 2D shape and social network classification via persistent homology. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 311, 113125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Ma, H.; Chen, L.; Wang, B.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Gao, W. Short-term load forecasting of an integrated energy system based on STL-CPLE with multitask learning. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2024, 9, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Chen, Z.; Wei, J.; Wang, R.; Zhao, Z. Deep mutual distillation for unsupervised domain adaptation person re-identification. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2024, 27, 1059–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Yu, T.; Pan, Z.; Wang, Z.; Yang, S. Graph representation learning-based residential electricity behavior identification and energy management. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2023, 8, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Zheng, T.; Du, P.; Chen, Z. An Intelligent Assisted Assessment Method for Distribution Grid Engineering Quality Based on Large Language Modelling and Ensemble Learning. Prot. Control Mod. Power Syst. 2025, 10, 83–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radford, A.; Kim, J.W.; Hallacy, C.; Ramesh, A.; Goh, G.; Agarwal, S.; Sastry, G.; Askell, A.; Mishkin, P.; Clark, J.; et al. Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, PMLR, Online, 18–24 July 2021; pp. 8748–8763. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Z.; Ma, M.; Wang, K.; Qin, Z.; Yue, X.; You, Y. Preventing zero-shot transfer degradation in continual learning of vision-language models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 19125–19136. [Google Scholar]

- Monsefi, A.K.; Sailaja, K.P.; Alilooee, A.; Lim, S.; Ramnath, R. DetailCLIP: Detail-Oriented CLIP for Fine-Grained Tasks. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.06809. [Google Scholar]

- Jing, D.; He, X.; Luo, Y.; Fei, N.; Yang, G.; Wei, W.; Zhao, H.; Lu, Z. FineCLIP: Self-distilled Region-based CLIP for Better Fine-Grained Understanding. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 10–15 December 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Deng, Y.; Li, Y.; Gu, Q. Understanding Transferable Representation Learning and Zero-shot Transfer in CLIP. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2310.00927. [Google Scholar]

- Su, J.; Jiang, C.; Jin, X.; Qiao, Y.; Xiao, T.; Ma, H.; Wei, R.; Jing, Z.; Xu, J.; Lin, J. Large language models for forecasting and anomaly detection: A systematic literature review. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2402.10350. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Zhang, P.; Dong, X.; Zang, Y.; Wang, J. Long-clip: Unlocking the long-text capability of clip. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 310–325. [Google Scholar]

- Asokan, M.; Wu, K.; Albreiki, F. FineLIP: Extending CLIP’s Reach via Fine-Grained Alignment with Longer Text Inputs. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025; pp. 14495–14504. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Zhang, X.; Yao, Q.; Tang, F.; Wu, H.; Li, Y.; Yan, R.; Jiang, Z.; Zhou, S.K. AA-CLIP: Enhancing Zero-shot Anomaly Detection via Anomaly-Aware CLIP. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Heckler-Kram, L.; Neudeck, J.H.; Scheler, U.; König, R.; Steger, C. The MVTec AD 2 Dataset: Advanced Scenarios for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.21622. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Xu, J.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Li, X. ViP2-CLIP: Visual-Perception Prompting with Unified Alignment for Zero-Shot Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.17692. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.; Won, J.; Lee, S.; Shin, J. CLIP Meets Diffusion: A Synergistic Approach to Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.11772. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Koh, H.Y.; Jin, M.; Chi, L.; Wang, H.; Phan, K.T.; Chen, Y.P.P.; Pan, S.; Xiang, W. Graph spatiotemporal process for multivariate time series anomaly detection with missing values. Inf. Fusion 2024, 106, 102255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ITU. Requirements and Framework of Intelligent Video Surveillance Platform for Power Grid Infrastructure; Technical Report F.743.27; ITU: Geneva, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, C.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Mao, Z.; Shen, J.; Cheng, Z. Breakthrough in fine-grained video anomaly detection on highway: New benchmark and model. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 296, 129127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamedi, P.; Razavi-Far, R.; Hallaji, E. Federated Continual Learning: Concepts, Challenges, and Solutions. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.07059. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L. Awesome-Continual-Learning. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/lywang3081/Awesome-Continual-Learning (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Wang, Y.; Kuang, J.; Teng, Y.; Xiang, S.; Li, L.; Zhou, Y. LEAD-Net: Semantic-Enhanced Anomaly Feature Learning. Processes 2025, 13, 2341. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, B.B.; Zhou, Y.; Yan, J.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Liu, J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, L.; Wang, C. AdaptCLIP: Adapting CLIP for Universal Visual Anomaly Detection. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.09926. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, P.; Li, C.; Codella, N.; Li, L.H.; Zhou, L.; Dai, X.; Yuan, L.; Li, Y.; et al. RegionCLIP: Region-based Language-Image Pretraining. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.09106. [Google Scholar]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).