FD-RTDETR: Frequency Enhancement and Dynamic Sequence-Feature Optimization for Object Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Wavelet Transform in Computer Vision

2.2. Multi-Scale Feature Fusion

2.3. Feature Map Sampling Methods

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Datasets

3.2. FD-RTDETR

3.2.1. Architecture

3.2.2. FAIFI

3.2.3. DFSS

3.2.4. Overall Architecture Flow

3.3. Experimental Setup

3.3.1. Experimental Environment

3.3.2. Evaluation Metrics

4. Experimental Results and Analysis

4.1. Comparison of Different Detection Models

4.2. Ablation Experiment

4.2.1. Comparison of Different Modules in FAIFI

4.2.2. Comparison of Different Fusion Strategies

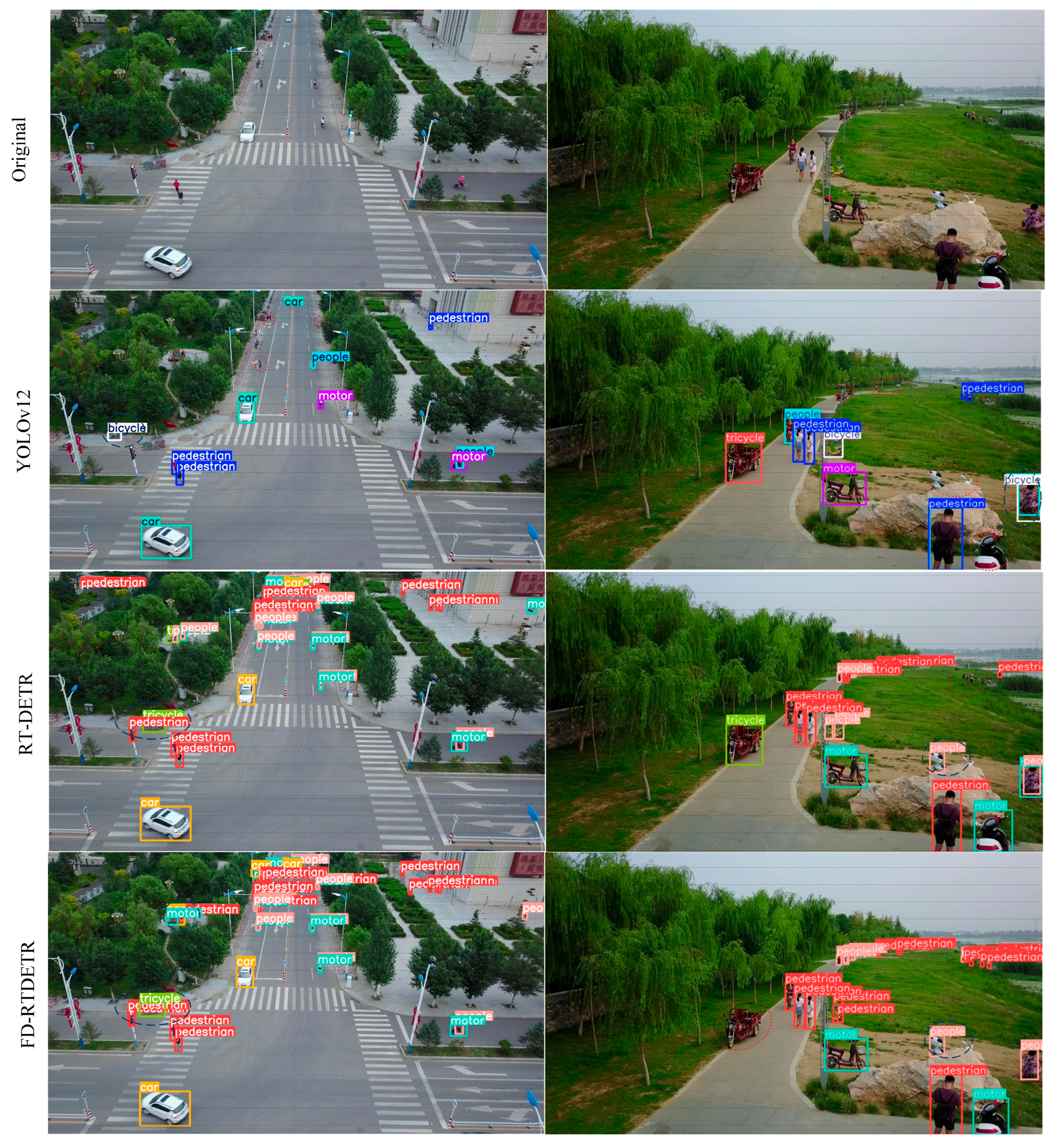

4.3. Visualization Experiments

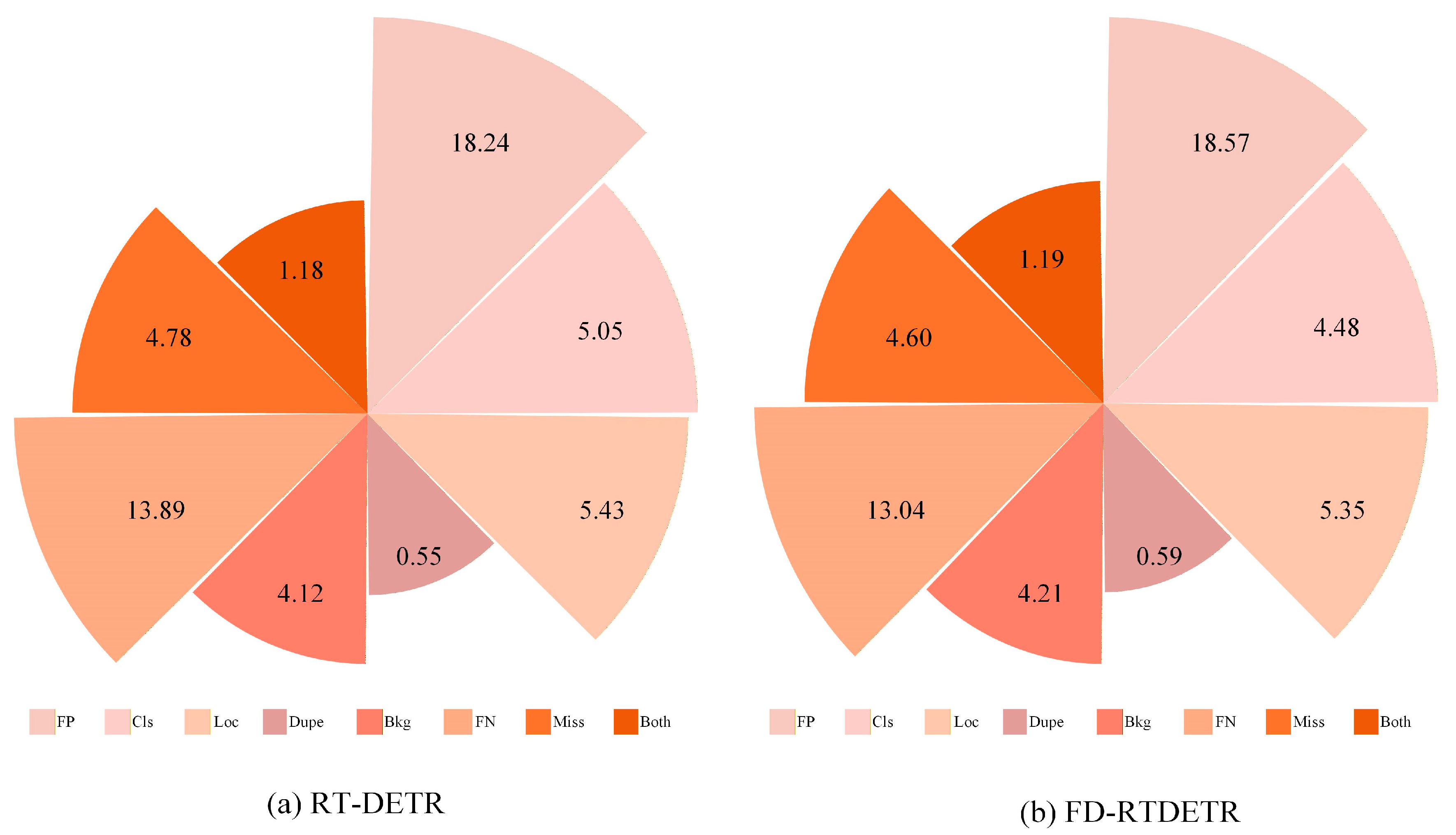

4.4. Error Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2012, 25, 89–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carion, N.; Massa, F.; Synnaeve, G.; Usunier, N.; Kirillov, A.; Zagoruyko, S. End-to-end object detection with transformers. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 213–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Su, W.; Lu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, X.; Dai, J. Deformable DETR: Deformable Transformers for End-To-End Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.04159. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Zhang, P.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, L. Dynamic detr: End-to-end object detection with dynamic attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 2988–2997. [Google Scholar]

- Roh, B.; Shin, J.; Shin, W.; Kim, S. Sparse detr: Efficient end-to-end object detection with learnable sparsity. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.14330. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Du, D.; Zhu, P.; Wen, L.; Bian, X.; Lin, H.; Hu, Q.; Peng, T.; Zheng, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. VisDrone-DET2019: The vision meets drone object detection in image challenge results. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27–28 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Suo, J.; Wang, T.; Zhang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhou, W.; Shi, W. HIT-UAV: A high-altitude infrared thermal dataset for Unmanned Aerial Vehicle-based object detection. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guo, T.; Seyed Mousavi, H.; Huu Vu, T.; Monga, V. Deep wavelet prediction for image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 104–113. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, P.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, K.; Lin, L.; Zuo, W. Multi-level wavelet-CNN for image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 773–782. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Guo, H.; Liu, X.; Liang, K.; Hu, J.; Ma, Z.; Guo, J. Efficient face super-resolution via wavelet-based feature enhancement network. In Proceedings of the32nd ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Melbourne, Australia, 28 October–1 November 2024; pp. 4515–4523. [Google Scholar]

- Finder, S.E.; Amoyal, R.; Treister, E.; Freifeld, O. Wavelet convolutions for large receptive fields. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 363–380. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, T.; Pan, Y.; Li, Y.; Ngo, C.-W.; Mei, T. Wave-vit: Unifying wavelet and transformers for visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 25–27 October 2022; pp. 328–345. [Google Scholar]

- Li, A.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, C. Feature modulation transformer: Cross-refinement of global representation via high-frequency prior for image super-resolution. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 12514–12524. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Q.; Yang, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, G.; Ding, W.; Wu, W.; Pelusi, D. Information fusion for multi-scale data: Survey and challenges. Inf. Fusion 2023, 100, 101954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.-Y.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Hariharan, B.; Belongie, S. Feature pyramid networks for object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 2117–2125. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, S.; Qi, L.; Qin, H.; Shi, J.; Jia, J. Path aggregation network for instance segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 8759–8768. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, M.; Pang, R.; Le, Q.V. Efficientdet: Scalable and efficient object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 21–24 June 2020; pp. 10781–10790. [Google Scholar]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Boston, MA, USA, 7–12 June 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.-C.; Papandreou, G.; Kokkinos, I.; Murphy, K.; Yuille, A.L. Deeplab: Semantic image segmentation with deep convolutional nets, atrous convolution, and fully connected crfs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2017, 40, 834–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.; Ting, C.-M.; Ting, F.F.; Phan, R.C.-W. ASF-YOLO: A novel YOLO model with attentional scale sequence fusion for cell instance segmentation. Image Vis. Comput. 2024, 147, 105057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, T. Video saliency prediction via single feature enhancement and temporal recurrence. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 160, 111840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noh, H.; Hong, S.; Han, B. Learning deconvolution network for semantic segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Santiago, Chile, 7–13 December 2015; pp. 1520–1528. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Z.; He, T.; Shen, C.; Yan, Y. Decoders matter for semantic segmentation: Data-dependent decoding enables flexible feature aggregation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3126–3135. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Chen, K.; Xu, R.; Liu, Z.; Loy, C.C.; Lin, D. Carafe: Content-aware reassembly of features. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 3007–3016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Lu, H.; Fu, H.; Cao, Z. Learning to upsample by learning to sample. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 6027–6037. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, T.; Li, R. Wavelet pooling for convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 April–3 May 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Liao, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; He, X.; Wu, X. Haar wavelet downsampling: A simple but effective downsampling module for semantic segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 143, 109819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, C.; Zhang, W.; Huang, H.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, S.; Chen, K. RTMDet: An empirical study of designing real-time object detectors. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2212.07784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Jiang, H.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; Ma, X.; Chen, J.; Tang, X. PHSI-RTDETR: A lightweight infrared small target detection algorithm based on UAV aerial photography. Drones 2024, 8, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Z.; Ai, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, C. Efficient detr: Improving end-to-end object detector with dense prior. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2104.01318. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-Y.; Yeh, I.-H.; Mark Liao, H.-Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. YOLOv11: An Overview of the Key Architectural Enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. YOLOv12: Attention-Centric Real-Time Object Detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Bolya, D.; Foley, S.; Hays, J.; Hoffman, J. Tide: A general toolbox for identifying object detection errors. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 558–573. [Google Scholar]

| Overall framework of FD-RTDETR |

| Input: Input image I |

| Output: |

| 1: Step 1: Backbone Feature Extraction |

| 2: F2, F3, F4, F5 Backbone(I) |

| 3: Step 2: FAIFI Processing |

| 4: S5 FAIFI(F5) |

| 5: Step 3: DSFF Processing |

| 6: S2 HWD Downsample(F2) |

| 7: S3 Cnov1×1(F3) |

| 8: S4 DySample Upsample(F4) |

| 9: Conv3D (Stack (S2, S3, S4)) |

| 10: Step 4: Feature Fusion |

| 11: CCFF (F3, F4, S5, M) |

| 12: Step 5: Decoder&Head |

| 13: E Decoder&Head () |

| 14: return E |

| CNN-Based Object Detector | |||||||

| RTMDet | 52.3 | 80 | 55.7 | 41.3 | 43.2 | 26.4 | 37.7 |

| YOLOv8-M | 25.8 | 78.7 | 54.1 | 42.1 | 42.8 | 26.1 | 65.7 |

| YOLOv9-M | 20.0 | 76.5 | 55.3 | 42.4 | 43.9 | 26.8 | 55.5 |

| YOLOv10-M | 15.3 | 58.9 | 54.3 | 40.4 | 42.4 | 25.9 | 82.6 |

| YOLOv11-M | 20.0 | 67.7 | 55.2 | 42.8 | 44.3 | 27.2 | 62.5 |

| YOLOv12-M | 20.1 | 67.2 | 54.8 | 42.0 | 43.3 | 26.5 | 65.8 |

| DETR-Based Object Detector | |||||||

| Deformable DETR | 40 | 196 | 54.6 | 40.9 | 42.8 | 26.8 | _ |

| Efficient DETR | 32.1 | 159 | 58.8 | 44.0 | 46.1 | 28.5 | _ |

| RT-DETR-R18 | 20 | 57.3 | 61.6 | 45.0 | 46.6 | 28.6 | 65.4 |

| RT-DETR-R34 | 31.4 | 90 | 60.8 | 44.4 | 46.2 | 28.3 | 62.5 |

| PHSI-RTDETR | 14.0 | 47.5 | 60.8 | 45.6 | 47.1 | 28.7 | 39.9 |

| FD-RTDETR | 21 | 61.5 | 62.0 | 46.5 | 47.9 | 29.3 | 64.5 |

| YOLOv8-M | 94.5 | 96.6 | 91.4 | 57.8 | 59.3 | 79.9 | 51.0 |

| YOLOv9-M | 91.0 | 98.7 | 89.6 | 74.5 | 45.5 | 79.8 | 51.9 |

| YOLOv10-M | 88.0 | 96.8 | 84.5 | 66.1 | 52.5 | 77.7 | 47.4 |

| YOLOv11-M | 91.3 | 98.0 | 91.2 | 66.8 | 66.1 | 82.7 | 54.2 |

| RT-DETR-R18 | 93.5 | 96.7 | 91.0 | 60.8 | 66.2 | 81.7 | 52.3 |

| RT-DETR-R34 | 93.3 | 96 | 91.3 | 59.4 | 59.5 | 79.9 | 51.4 |

| FD-RTDETR | 94.3 | 94.9 | 91.4 | 67.1 | 64.2 | 82.4 | 53.1 |

| vs RT-DETR-R18 | +0.8 | −1.8 | +0.4 | +6.3 | −2.0 | +0.7 | +0.8 |

| YOLOv10 | YOLOv10s | 44.4 | 61.1 | 48.3 | 25.0 | 49.0 | 61.1 |

| YOLOv11 | YOLOv11s | 44.3 | 60.9 | 48.1 | 25.0 | 48.6 | 61.7 |

| RT-DETR | Resnet-18 | 44.4 | 61.3 | 47.9 | 26.5 | 47.7 | 57.9 |

| FD-RTDETR | Resnet-18 | 45.1 | 62.2 | 48.4 | 27.2 | 47.5 | 59 |

| RT-DETR-R18 | 71.7 | 71.1 | 91.5 | 89.1 | 88.9 | 85.1 |

| FD-RTDETR | 72.4 | 74.1 | 91.1 | 87.8 | 89.2 | 86.3 |

| vs | +0.7 | +3 | −0.4 | −1.3 | +0.3 | +1.2 |

| RT-DETR-R18 | 90.8 | 59.5 | 67.6 | 45.9 | 59.2 | 40.4 |

| FD-RTDETR | 90.7 | 59.7 | 67.1 | 48.4 | 62.3 | 39.6 |

| vs | −0.1 | +0.2 | −0.5 | +2.5 | +3.1 | −0.8 |

| Baseline | 19.97 | 57.3 | 143 | 44.4 | 61.3 | 47.9 | 26.5 | 47.7 | 57.9 |

| +FAIFI | 20.70 | 57.4 | 125 | 44.9 | 61.8 | 48.3 | 26.9 | 47.4 | 58.7 |

| +DFSS | 20.21 | 61.3 | 133 | 44.6 | 61.7 | 48.1 | 27.1 | 47.7 | 58.5 |

| +ALL | 20.94 | 61.5 | 118 | 45.1 | 62.2 | 48.4 | 27.2 | 47.5 | 59 |

| Baseline | 19.97 | 57.3 | 44.4 | 61.3 | 47.9 | 26.5 | 47.7 | 57.9 |

| CNRB | 21.15 | 57.7 | 44.1 | 61.2 | 47.7 | 26.3 | 47.4 | 58.5 |

| DSRB | 20.63 | 57.4 | 44.7 | 61.6 | 48.1 | 27.1 | 47.6 | 58.1 |

| D4RB | 20.70 | 57.4 | 44.9 | 61.8 | 48.3 | 26.9 | 47.4 | 58.7 |

| Fusion Strategy | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCFF | 44.4 | 61.3 | 63.6 | 64 | 43.7 | 66.9 | 79.8 |

| +SSFF | 44.0 | 61.1 | 63.5 | 64.1 | 43.5 | 67.9 | 78.7 |

| +DFSS | 44.6 | 61.7 | 64.5 | 64.8 | 44.4 | 68.1 | 80.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, W.; Wang, Q.; Zou, K.; Huang, Y.; Xu, Q. FD-RTDETR: Frequency Enhancement and Dynamic Sequence-Feature Optimization for Object Detection. Electronics 2025, 14, 4715. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234715

Wang W, Wang Q, Zou K, Huang Y, Xu Q. FD-RTDETR: Frequency Enhancement and Dynamic Sequence-Feature Optimization for Object Detection. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4715. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234715

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Wu, Qijin Wang, Kun Zou, Yichi Huang, and Qi Xu. 2025. "FD-RTDETR: Frequency Enhancement and Dynamic Sequence-Feature Optimization for Object Detection" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4715. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234715

APA StyleWang, W., Wang, Q., Zou, K., Huang, Y., & Xu, Q. (2025). FD-RTDETR: Frequency Enhancement and Dynamic Sequence-Feature Optimization for Object Detection. Electronics, 14(23), 4715. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234715