A Non-Cooperative Game-Based Retail Pricing Model for Electricity Retailers Considering Low-Carbon Incentives and Multi-Player Competition

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

1.2. Literature Review

1.2.1. VPP Operations and Coordination with DSO

1.2.2. Incorporating Low-Carbon Considerations

1.2.3. Pricing Strategies for VPPs

1.3. Contributions

- (1)

- We develop an MDP-based non-cooperative game model for electricity retailers. This model integrates a User Equilibrium (UE) model to capture price-sensitive customer choices, enabling retailers to dynamically optimize their retail prices in a competitive environment while considering the operational constraints and costs of their internal DERs.

- (2)

- We design and incorporate a low-carbon incentive mechanism into the pricing model. This mechanism utilizes spatially differentiated carbon emission factors, which are dynamically adjusted for each retailer based on the real-time proportion of its PV generation to total electricity sales. This directly quantifies and monetizes the low-carbon attributes of a retailer’s energy mix, transforming it into a competitive edge within the pricing game.

- (3)

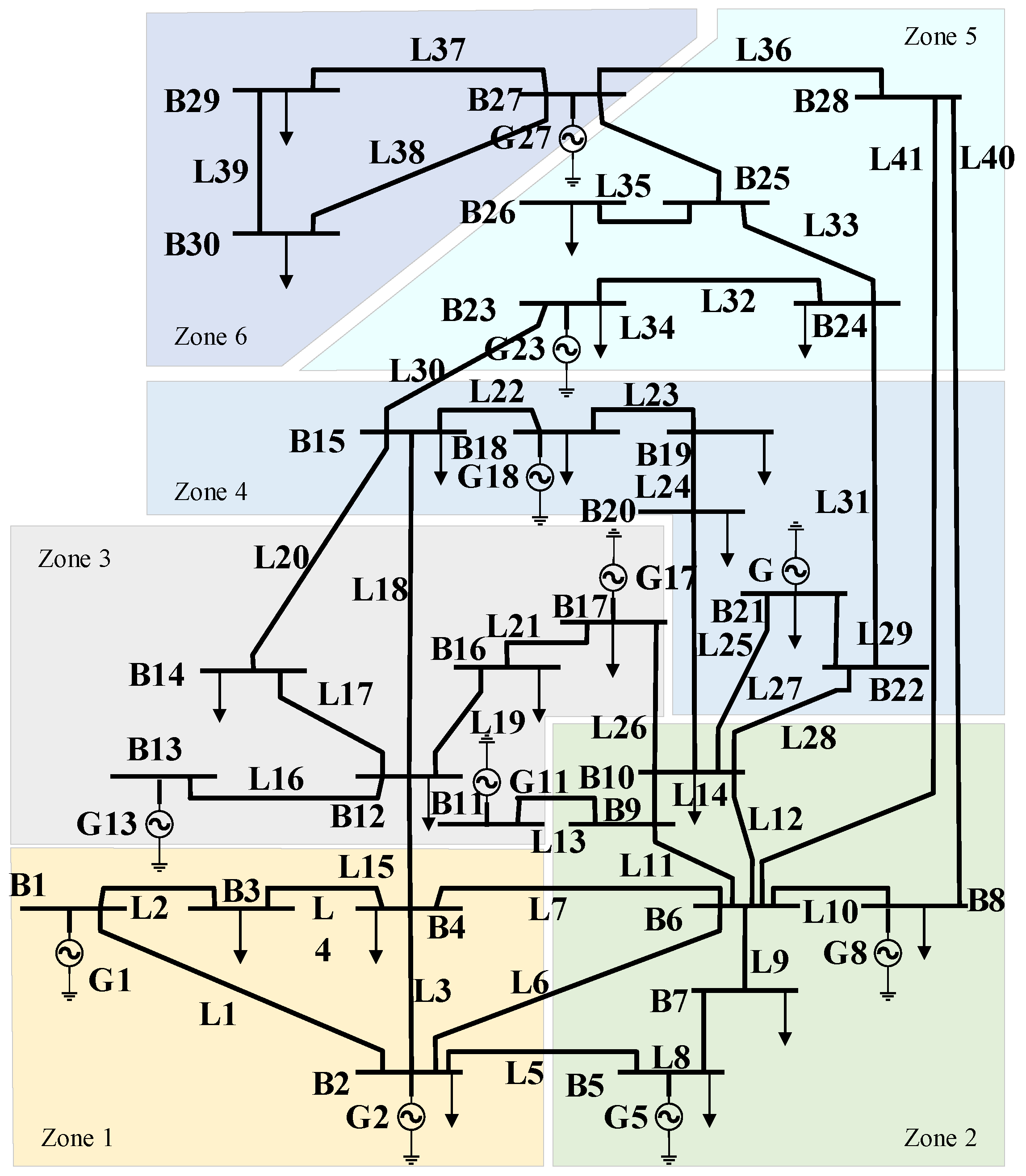

- Through case studies on a modified IEEE 30-bus system, we demonstrate the practical efficacy of the proposed framework. The results validate that our model not only ensures profitability for retailers but also contributes to the technical security of the distribution network by alleviating congestion and mitigating voltage violations.

1.4. Structure of the Paper

2. Problem Analysis

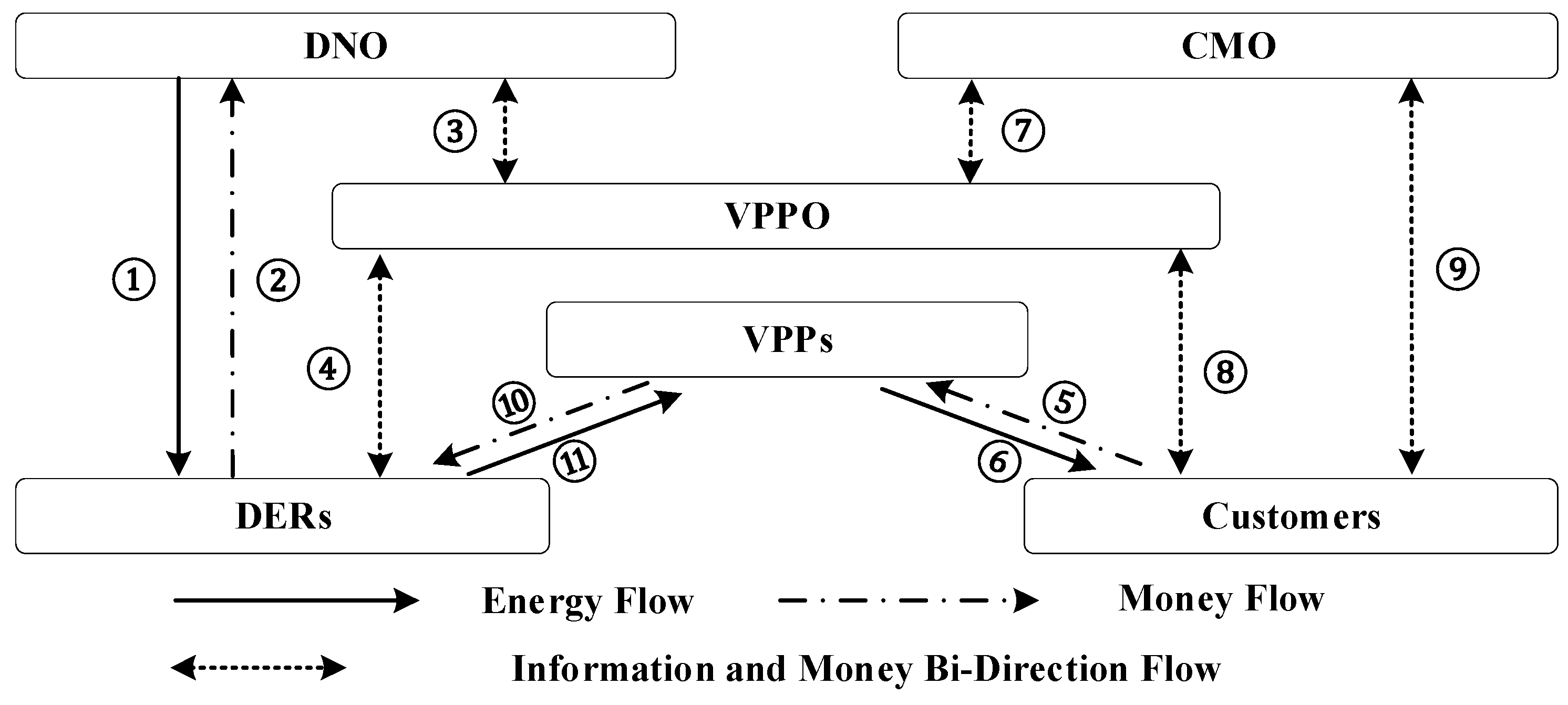

2.1. Multi-VPP Architecture in Electricity and Carbon Markets

2.2. Connections and Business Model of Related Entities

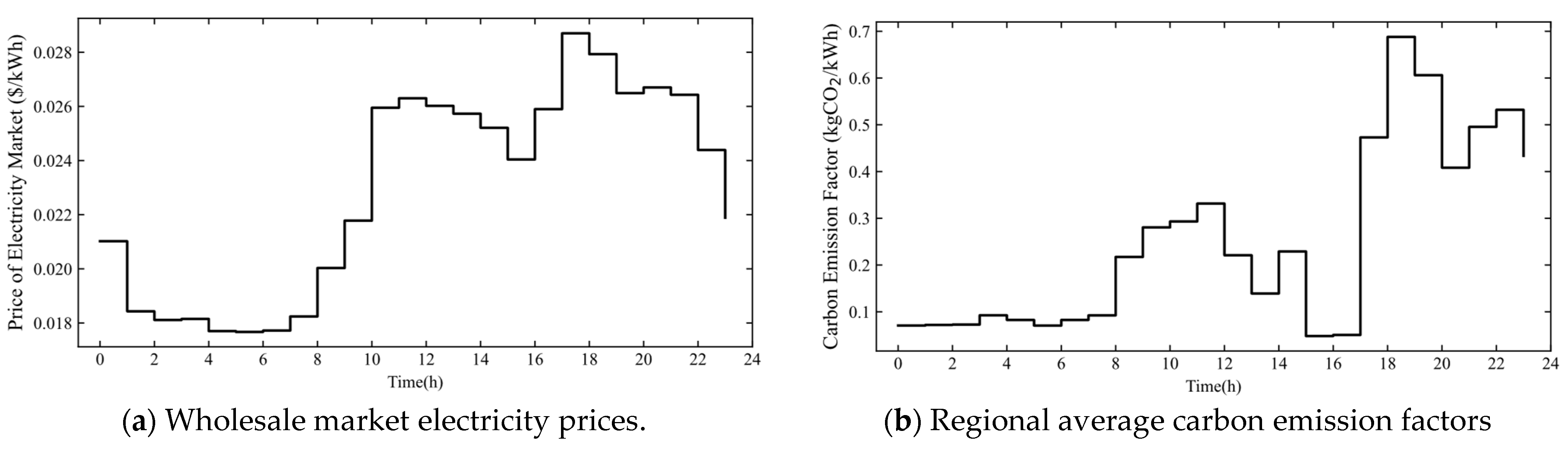

2.3. Carbon Emission Factor

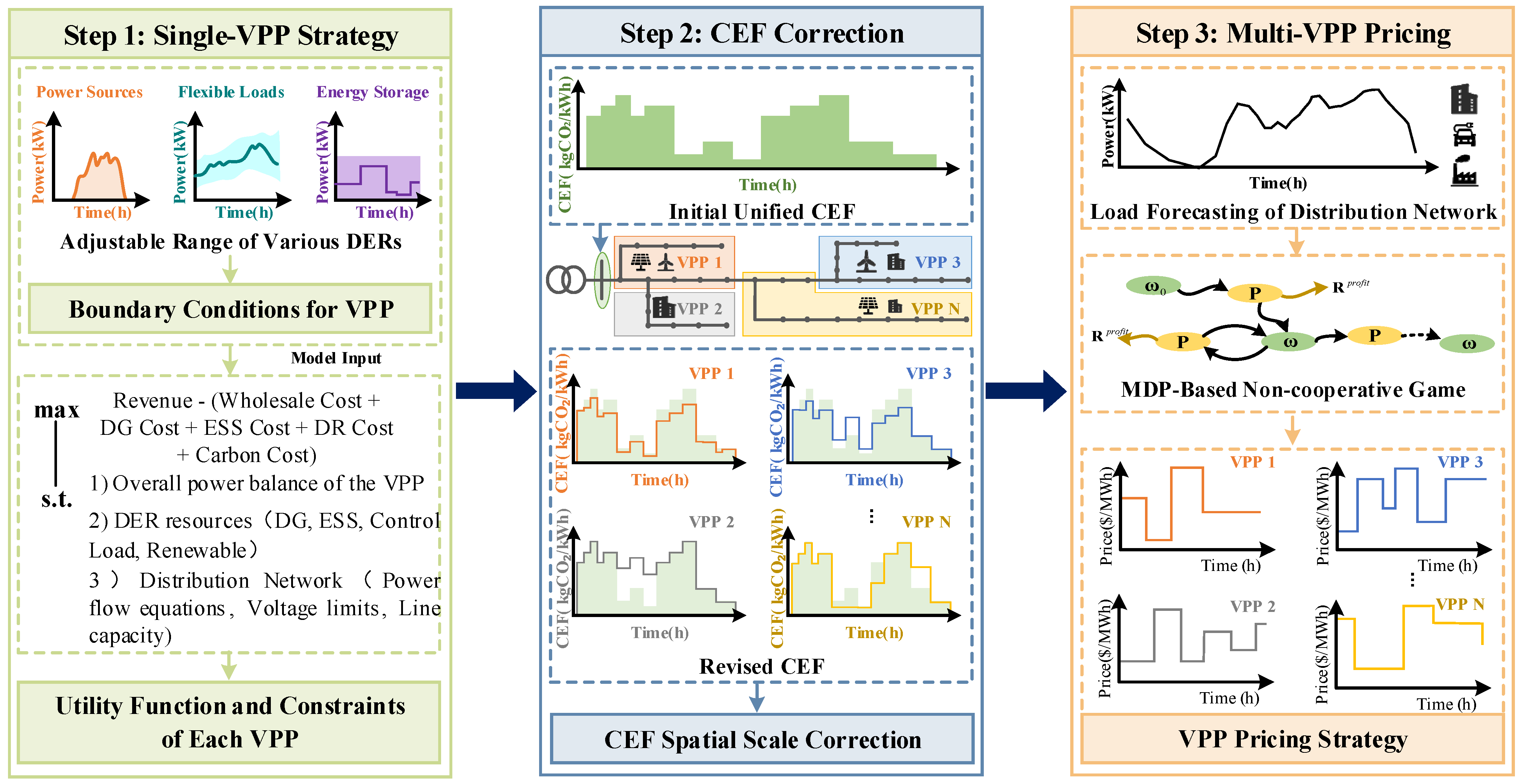

3. Methodology and Mathematical Models

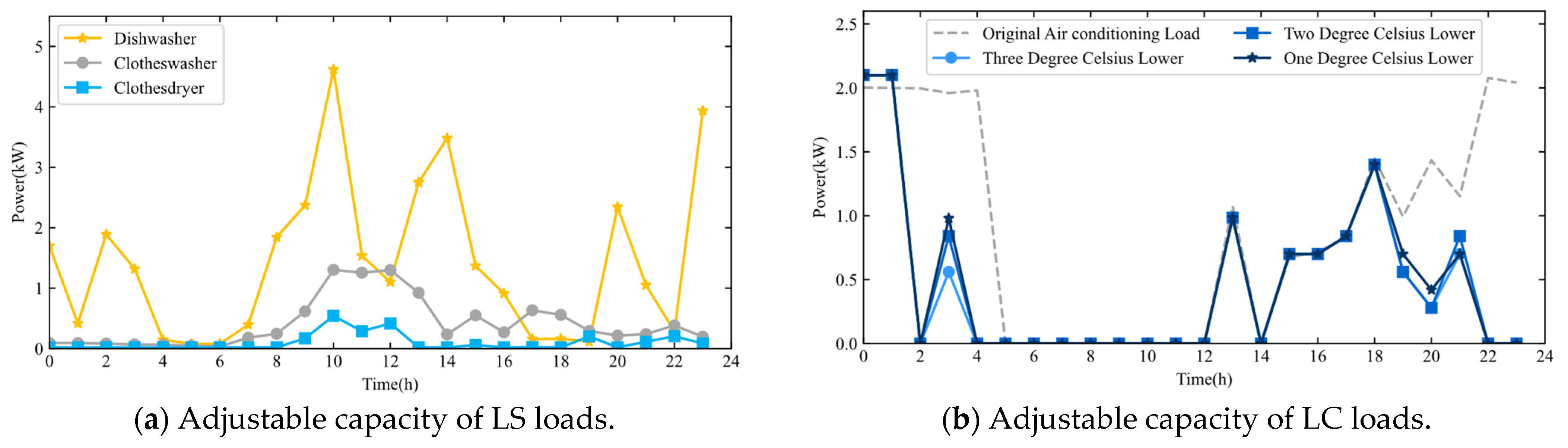

3.1. Dispatching Model for a Single VPP

3.1.1. Objective Function

3.1.2. Constraints

- Overall power balance of the VPP

- 2.

- Generation-type resources

- 3.

- Load-type resources

- 4.

- Storage-type resources

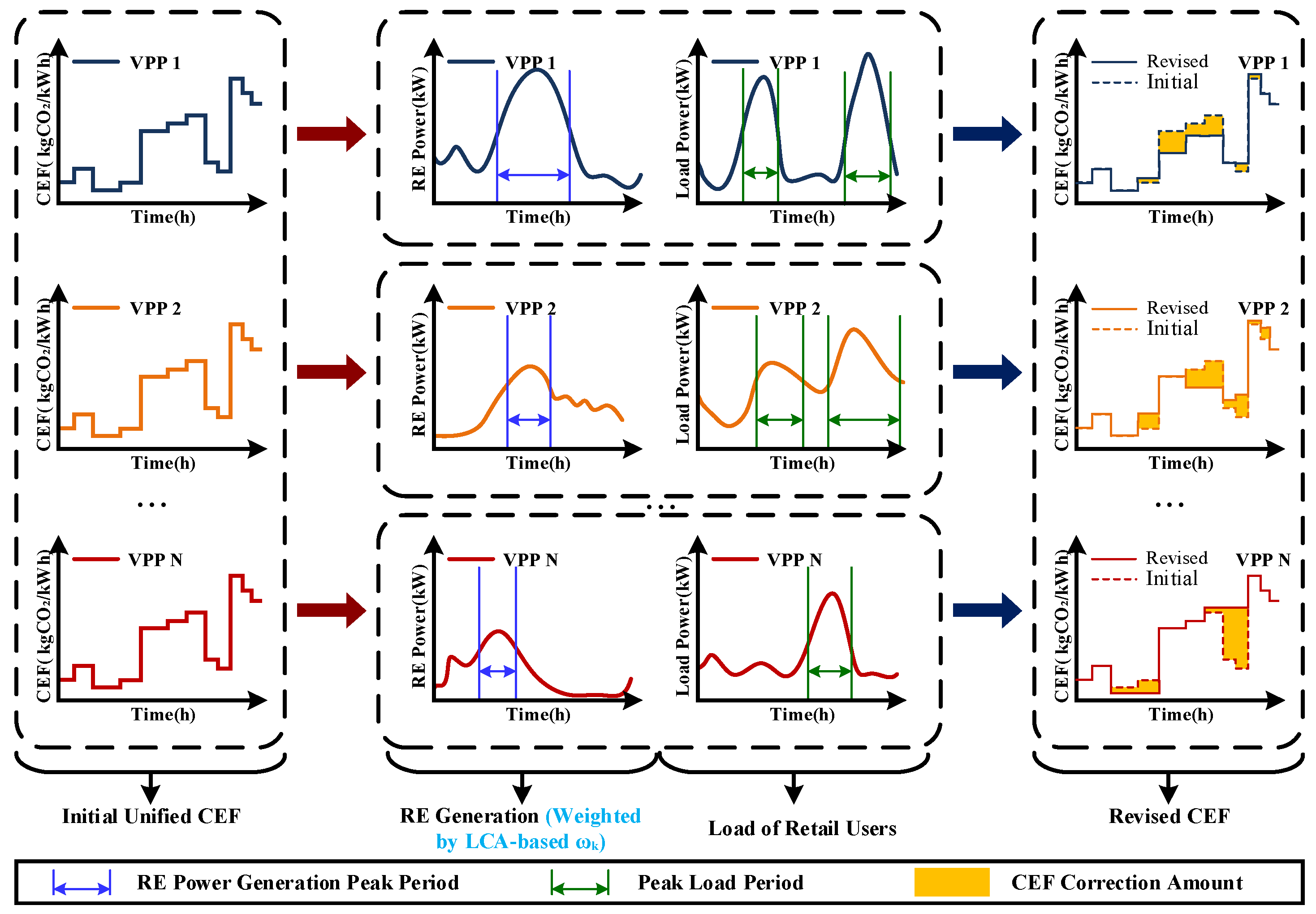

3.2. Carbon Emission Factor Correction

- Adding the corresponding generation term to the summation in Equation (24b).

- Calibrating the weight coefficient based on technology-specific LCA data.

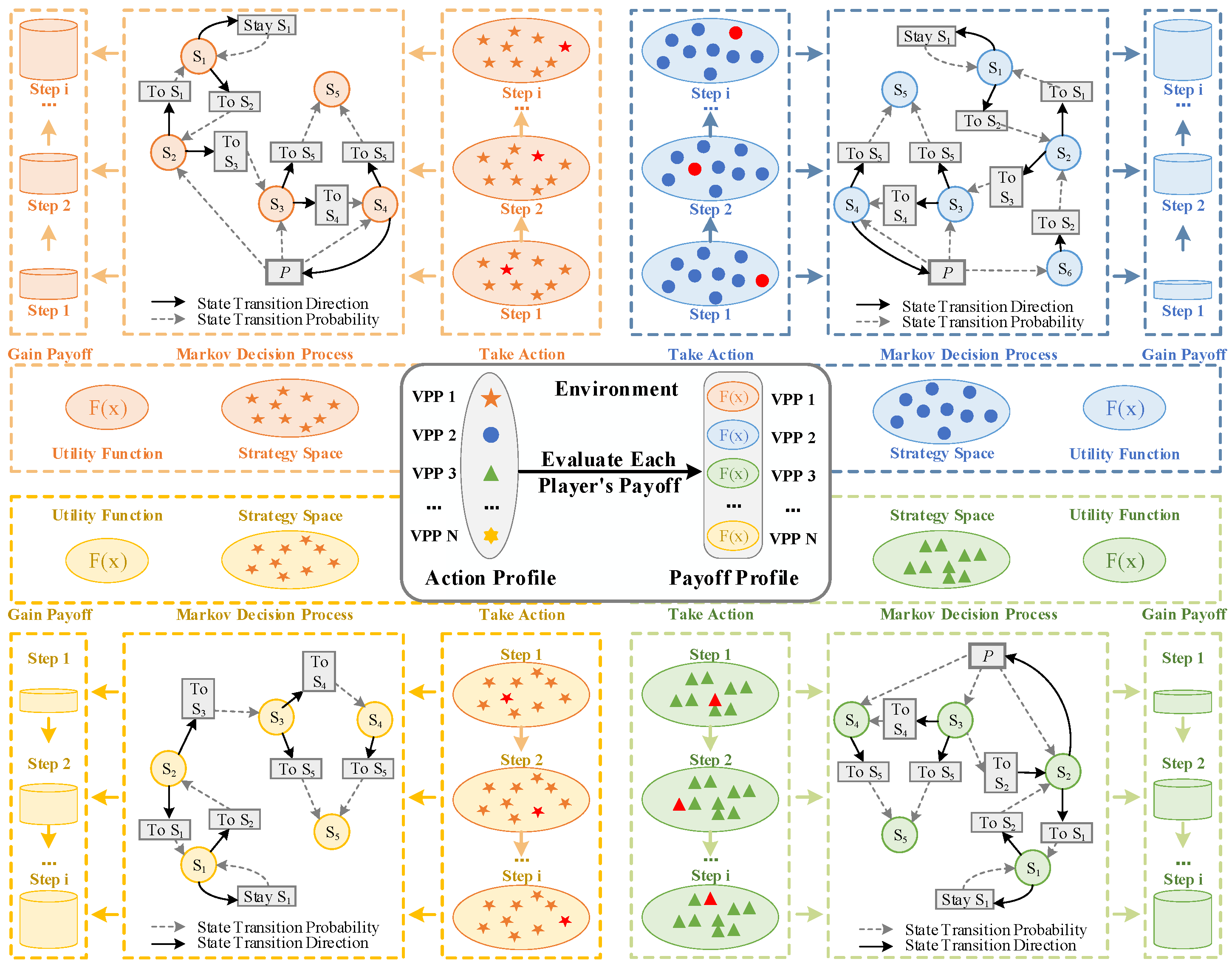

3.3. Non-Cooperative Game Between VPPs Based on MDP

3.3.1. VPP Behavioral Modeling

3.3.2. Pool State Model and State Transition Probability

3.3.3. Distributed VPP Pricing Model Based on MDP

- Participants: VPP set .

- Decision: Develop a pricing strategy for each VPP

- Objective: The goal of each VPP is to find the optimal price strategy in all market conditions to maximize the discounted future revenue. That is, for , find to obtain the maximum , as shown in (40).

3.3.4. Solution Algorithm

| Algorithm 1 Optimal VPP Pricing Strategy Algorithm |

| Input: customers’ demand , budget , discount factor , DER-related parameters, initial unified CEF |

| Output: Optimal price strategy |

| 1: Initialization: select the possible initial values and , and randomly select a state vector as the initial state |

| 2: Set convergence parameters: tolerance ε, maximum iterations max_iter |

| 3: Conditions for the end of the loop: stop: = 0, iterated index: t: = 0 |

| 4: Executed when stop ≠ 0 |

| 5: Sequential VPP Update: For i = 1 to N VPPs in fixed order: |

| 6: Freeze other VPPs: Keep prices of VPPs 1 to i − 1 at their newly updated values, and VPPs I + 1 to N at previous iteration values |

| 7: Solve Optimization: According to (43) and (44) calculating and cc: = |

| 8: Immediate Update: Update VPP i’s price strategy immediately after computation |

| 9: End Sequential Update |

| 10: Convergence Check: Calculate maximum price change across all VPPs: ΔP_max = max|P_new − P_old| |

| 11: when or ΔP_max < ε or t ≥ max_iter: |

| 12: stop: = 1 |

| 13: else |

| 14: Calculate the new market state |

| 15: t: = t + 1 |

| 16: End Convergence Check |

| 17: End Gauss–Seidel Iteration |

| 18: End Algorithm |

4. Case Study

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.2. Simulation Results

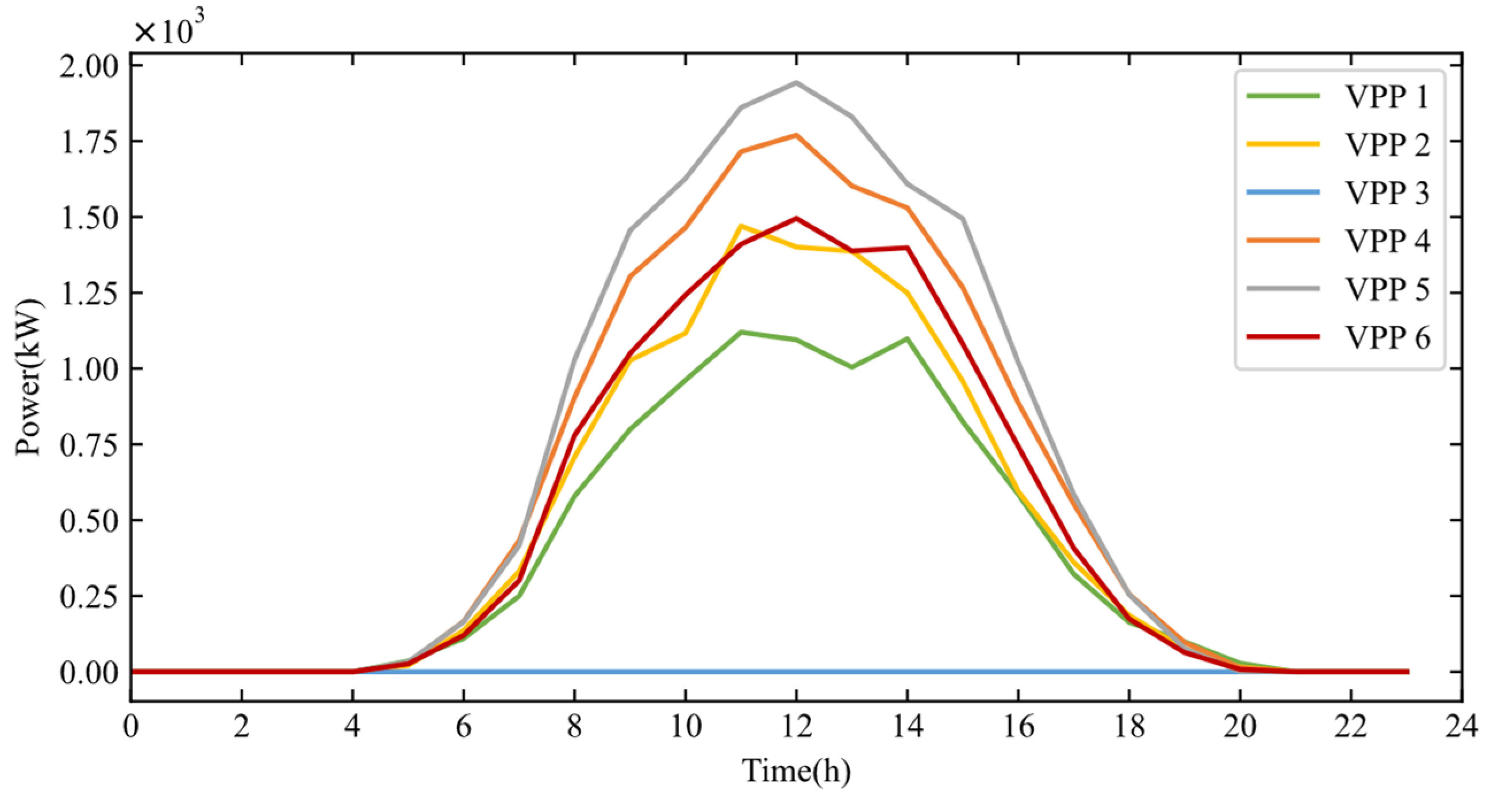

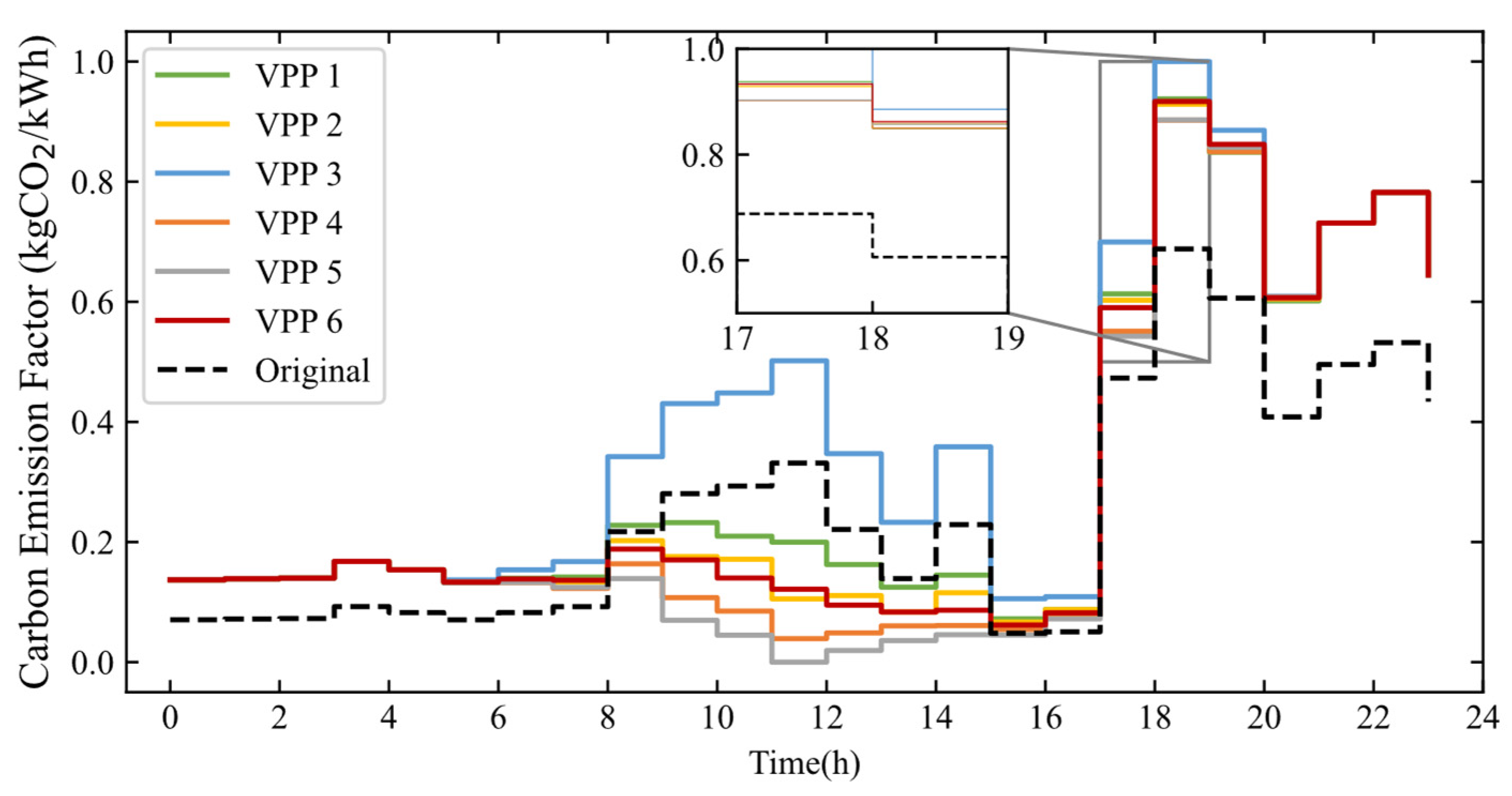

4.2.1. VPP Carbon Emission Factor Calculation

4.2.2. VPP Pricing

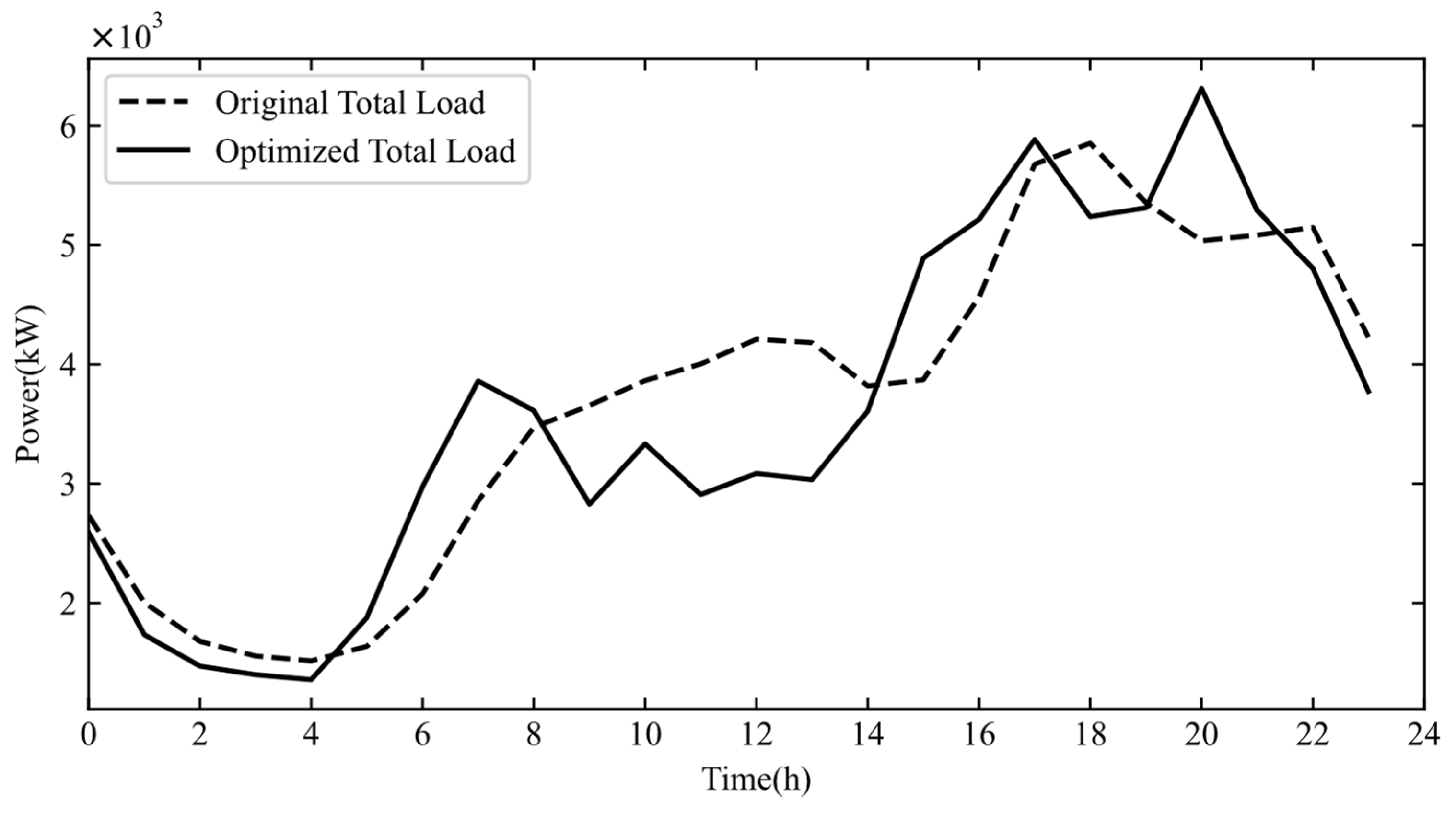

4.2.3. Load Curve Before and After VPP Optimization Pricing

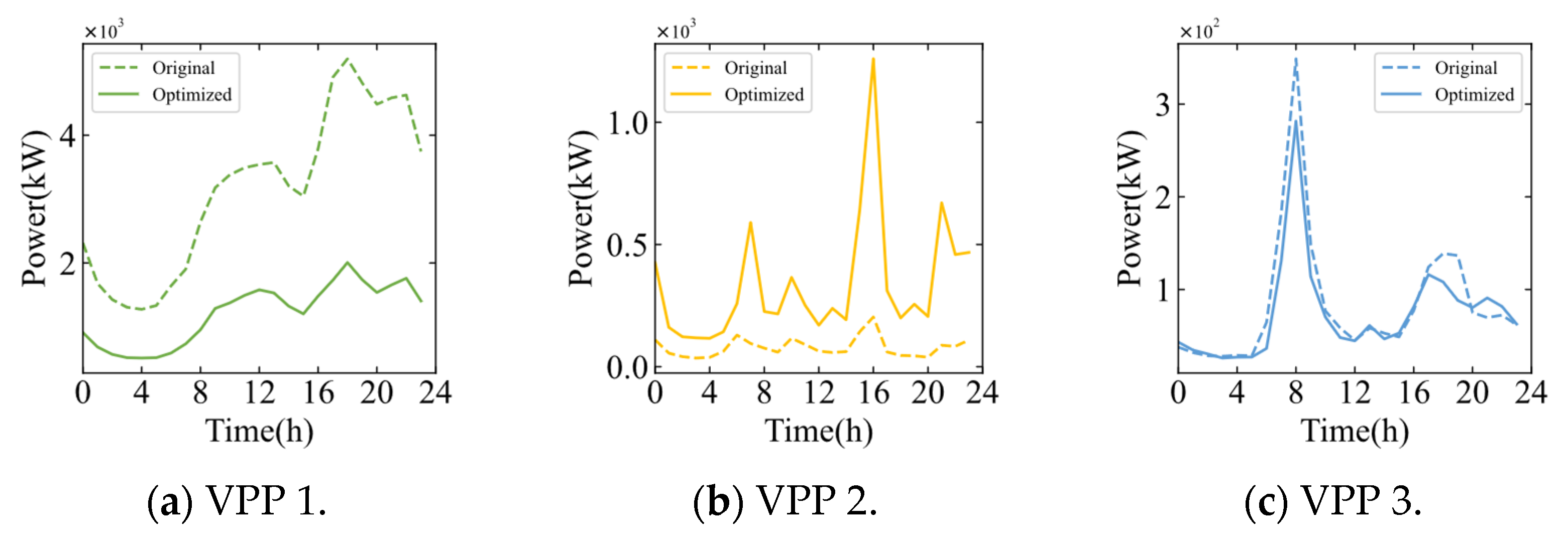

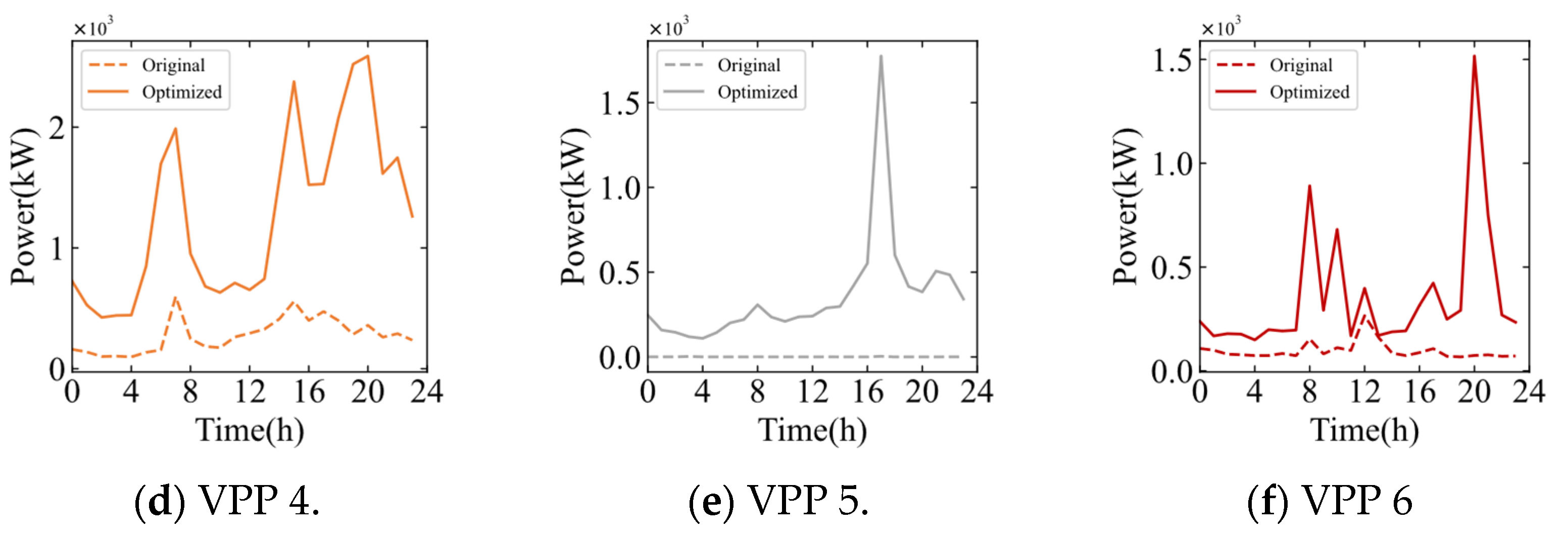

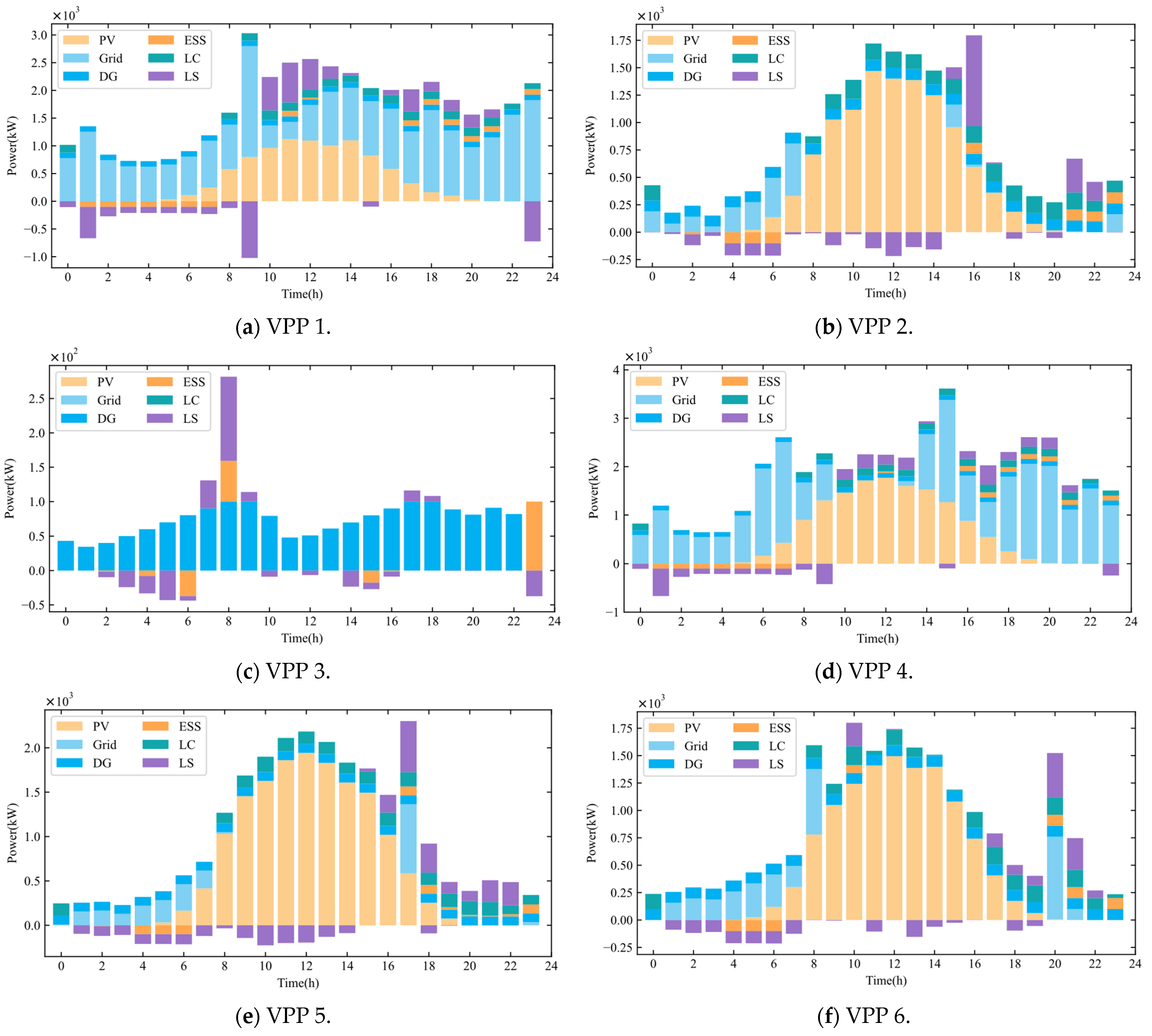

4.2.4. Dispatch of DERs of VPPs

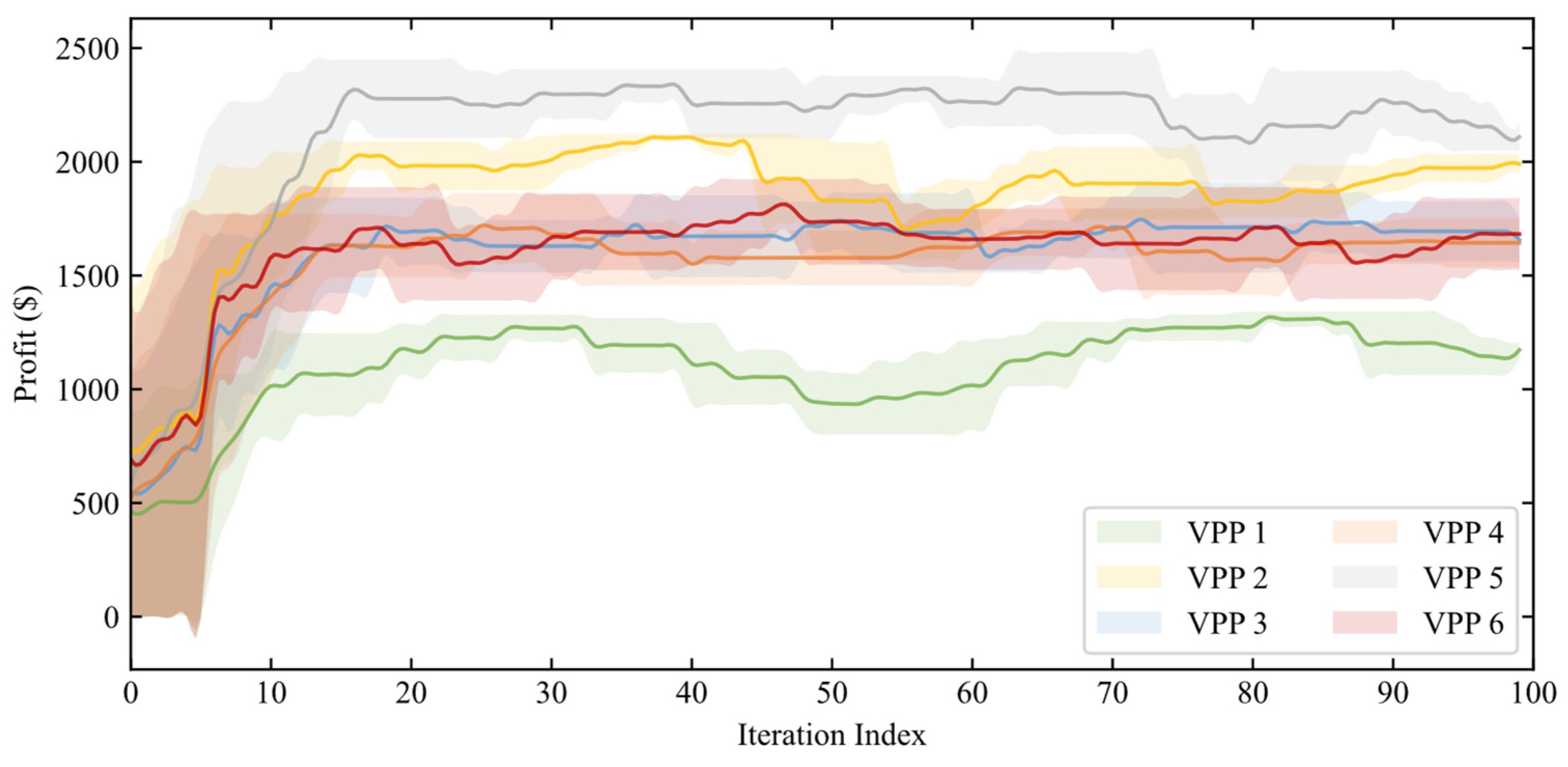

4.2.5. Profits of VPPs

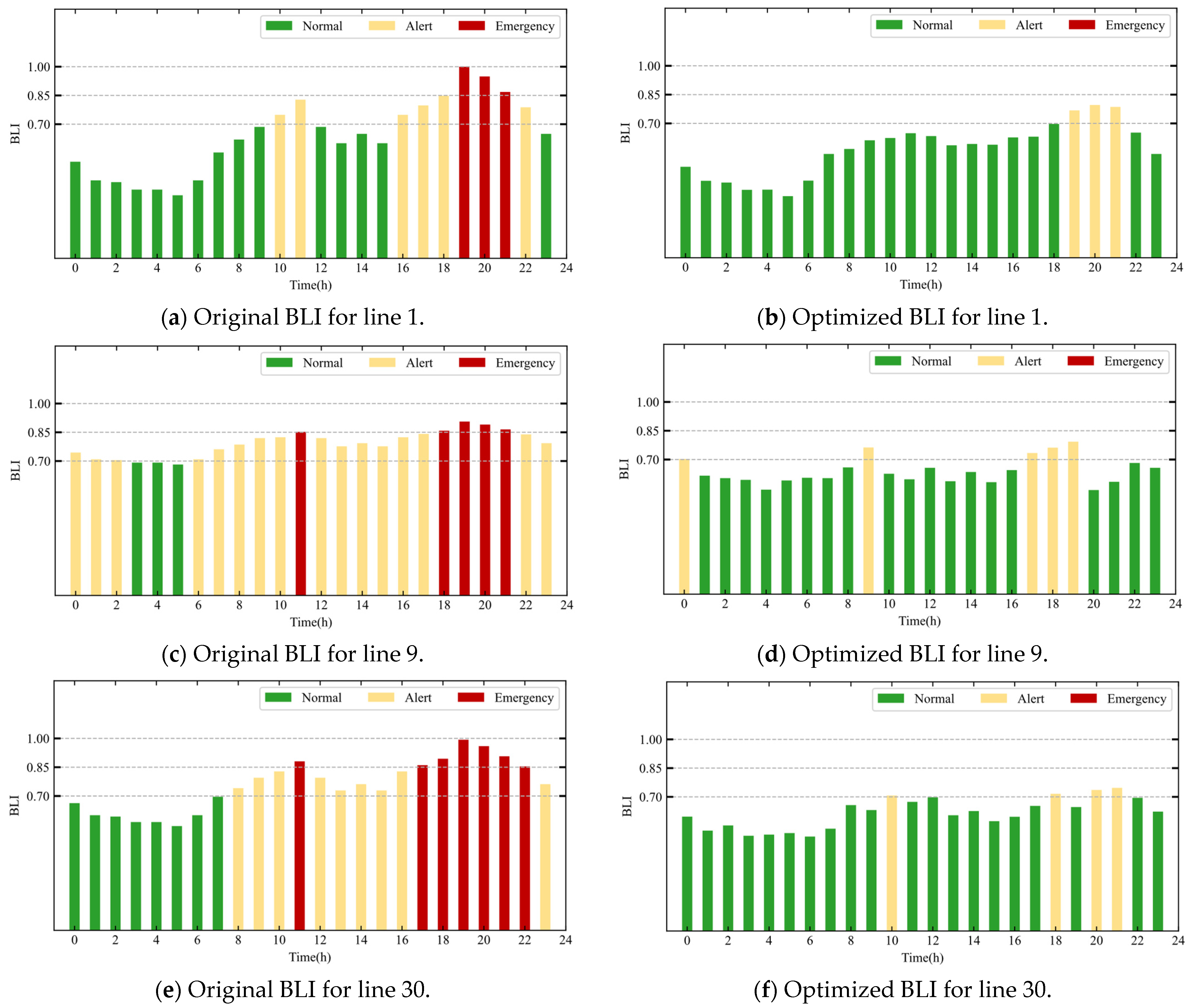

4.2.6. DSO Dispatching

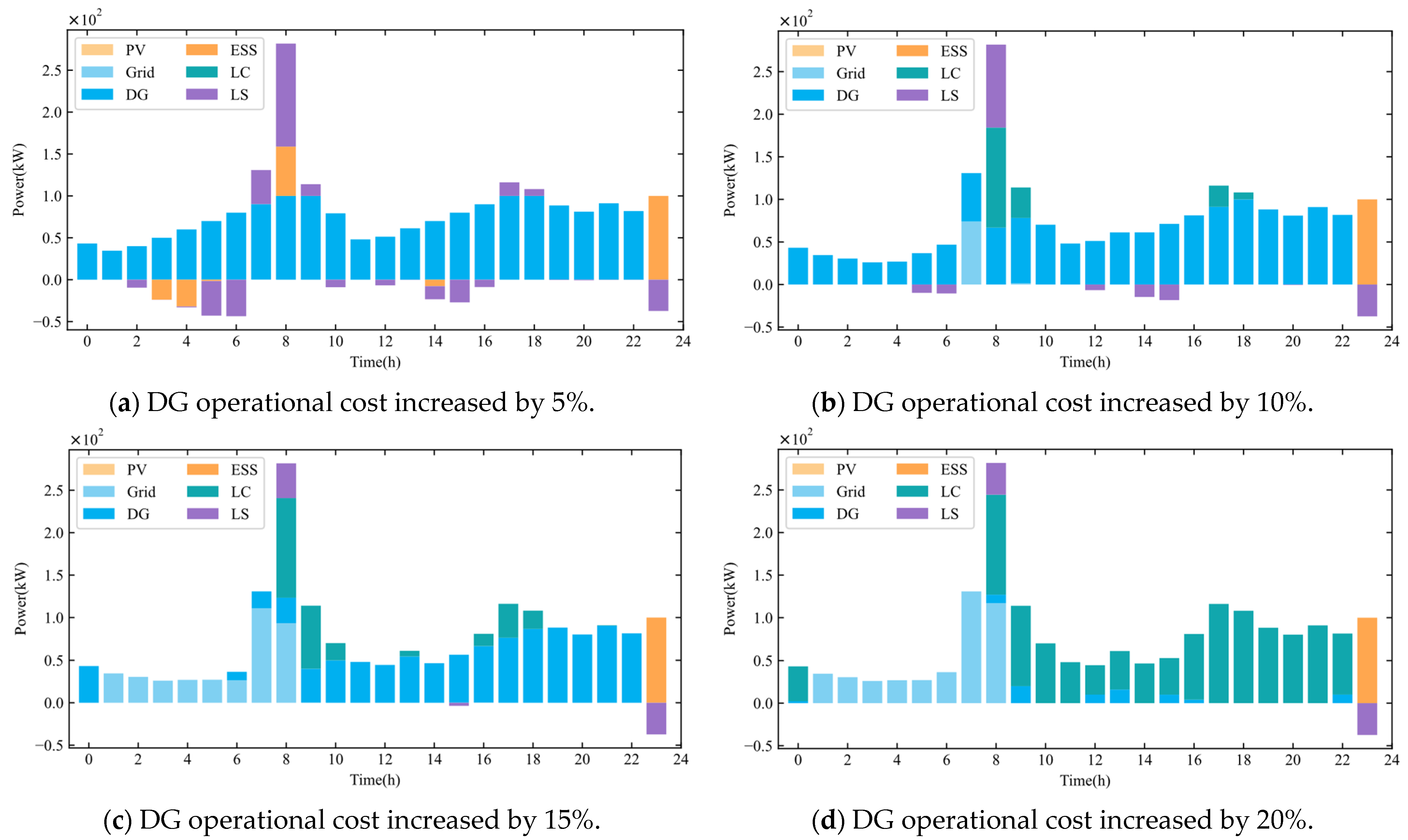

4.2.7. Sensitivity Analysis: Impact of DG Cost Variations on VPP Dispatch

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The case study confirms that VPPs with a higher proportion of DPVs achieve a lower carbon emission factor, constituting a significant low-carbon competitive advantage. This advantage directly translates into higher profitability, as evidenced by VPP 5. In contrast, VPPs with fewer low-carbon resources strategically adopted zero or low-price tariffs to attract price-sensitive consumers, as evidenced by VPP 1 and VPP 3, demonstrating how heterogeneous resource portfolios drive distinct competitive behaviors.

- (2)

- The proposed dynamic pricing mechanism successfully reshaped user demand. It shifted the load from being concentrated on a few VPPs to a more diversified and balanced distribution across all VPPs. This alleviated operational stress on specific distribution network nodes, reducing the Branch Load Index (BLI) by 12% and improving voltage profiles by up to 1.32% at critical nodes.

- (3)

- Profit analysis reveals that a VPP’s profitability is not solely determined by its electricity sales volume. For instance, VPP 3, despite having the lowest sales, achieved comparable profits to VPP 4 and VPP 6 through the optimal dispatch of its internal DERs, particularly its DG. This indicates that efficient internal resource management is a crucial determinant of a VPP’s economic performance.

- (4)

- The framework demonstrably improved the technical operation of the distribution power system. Simulations showed a significant improvement in nodal voltages and a consistent reduction in BLI, transitioning lines from emergency/alert states to normal/alert states. This confirms the model’s efficacy in alleviating network congestion and enhancing operational security.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Muhtadi, A.; Pandit, D.; Nguyen, N.; Mitra, J. Distributed Energy Resources Based Microgrid: Review of Architecture, Control, and Reliability. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2021, 57, 2223–2235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gough, M.; Santos, S.F.; Lotfi, M.; Javadi, M.S.; Osório, G.J.; Ashraf, P.; Castro, R.; Catalão, J.P.S. Operation of a Technical Virtual Power Plant Considering Diverse Distributed Energy Resources. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2022, 58, 2547–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, S.; Zhu, J. Optimal Coordination for Multiple Network-Constrained VPPs via Multi-Agent Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 14, 3016–3031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Qi, L.; Wang, D.; Ai, Q. Two-Stage Coordinated Operation Mechanism for Virtual Power Plant Clusters Based on Energy Interaction. Electronics 2025, 14, 2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirocco, L.; Pudney, P.; Riahi, S.; Liddle, R.; Semsarilar, H.; Hudson, J.; Bruno, F. Thermal Energy Storage for Industrial Thermal Loads and Electricity Demand Side Management. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 270, 116190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grigiante, M.; Mottes, G.; Buratti, A. Effectiveness of Optimization Procedures on the Economic Profitability of a Virtual Tri-Generation Power Plant Connected to a District Heating Cooling Network. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 274, 116466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolzoni, A.; Parisio, A.; Todd, R.; Forsyth, A.J. Optimal Virtual Power Plant Management for Multiple Grid Support Services. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2020, 36, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahloul, M.; Breathnach, L.; Cotter, J.; Daoud, M.; Saif, A.; Khadem, S. Role of Aggregator in Coordinating Residential Virtual Power Plant in “StoreNet”: A Pilot Project Case Study. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2022, 13, 2148–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perfumo, C.; Kofman, E.; Braslavsky, J.H.; Khadem, J.K. Load Management: Model-Based Control of Aggregate Power for Populations of Thermostatically Controlled Loads. Energy Convers. Manag. 2012, 55, 36–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, D.; Shen, Z.; Li, X.; Lv, X. Bi-Level Scheduling Model for a Novel Virtual Power Plant Incorporating Waste Incineration Power Plant and Electric Waste Truck Considering Waste Transportation Strategy. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 298, 117773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fu, W.; Wang, J.; Zhen, Z.; Wang, F. Ultra-Short-Term Distributed PV Power Forecasting for Virtual Power Plant Considering Data-Scarce Scenarios. Appl. Energy 2024, 373, 123890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Feng, X.; Cai, S.; Niu, Y.; Pen, H. A Privacy-Preserving Federated Reinforcement Learning Method for Multiple Virtual Power Plants Scheduling. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I 2025, 72, 1939–1950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Ma, Z.; Shao, X.; Chen, G.; Qi, J. Renewable-Aware Container Migration in Multi-Data Centers. Electronics 2025, 14, 4345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maris, T.I.; Christodoulou, C.; Mladenov, V. Enhancing Distribution Network Resilience Using Genetic Algorithms. Electronics 2025, 14, 4324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Liu, L.; Wang, F.; Wang, T.; Duić, N.; Shafie-khah, M.; Catalão, J.P.S. Impact Factors Analysis on the Probability Characterized Effects of Time of Use Demand Response Tariffs Using Association Rule Mining Method. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 197, 111891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, L.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, H.; Li, F. Privacy-Preserving Multi-Level Co-Regulation of VPPs via Hierarchical Safe Deep Reinforcement Learning. Appl. Energy 2024, 371, 123654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Liu, J.; Tang, Z.; Zhou, Y.; Jiang, B.; Zeng, P.; Zhou, X. Coordinated DSO-VPP Operation Framework with Energy and Reserve Integrated from Shared Energy Storage: A Mixed Game Method. Appl. Energy 2025, 379, 125006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, D.; Koo, D.; Shin, C.; Won, D. Hierarchical Robust Day-Ahead VPP and DSO Coordination Based on Local Market to Enhance Distribution Network Voltage Stability. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 160, 110076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Meng, Q.; Liu, J.; Yan, Y.; Wu, H. Multi-Energy Cooperative Optimal Scheduling of Rural Virtual Power Plant Considering Flexible Dual-Response of Supply and Demand and Wind-Photovoltaic Uncertainty. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 320, 118990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Ren, B.; Zhu, X.; Zhu, D.; Li, H.; Zhang, N.; Jia, Y. The Coordinated Voltage Support Emergency Control Strategy of the Renewable Energy Plants under Extreme Weather. Electronics 2025, 14, 4244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monie, S.; Nilsson, A.M.; Widén, J.; Åberg, M. A Residential Community-Level Virtual Power Plant to Balance Variable Renewable Power Generation in Sweden. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 228, 113597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, T.; Ocłoń, P.; He, L.; Cisek, P.; Nowak-Ocłoń, M.; Fan, Y.V.; Wang, B.; Molnár, P.; Tóth, Á.; Varbanov, P.S. Operational Optimisation of Integrated Solar Combined Cooling, Heating, and Power Systems in Buildings Considering Demand Response and Carbon Trading. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 315, 118737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Jin, T.; Wang, G.; Chen, Q.; Kang, C.; Zhu, J. Low-Carbon Dispatching for Virtual Power Plant with Aggregated Distributed Energy Storage Considering Spatiotemporal Distribution of Cleanness Value. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2024, 12, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Z.; Sun, Q.; Wang, L.; Chen, S.; Gong, T.; Ge, X. Low-Carbon and Economic Scheduling Strategy for Virtual Power Plant Based on Complementary Characteristics and Aggregation Model of DER. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/IAS Industrial and Commercial Power System Asia (I&CPS Asia), Shanghai, China, 18–21 July 2024; pp. 502–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Ni, Y.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, R.; Sun, Q. Multi-VPPs Power-Carbon Joint Trading Optimization Considering Low-Carbon Operation Mode. J. Energy Storage 2024, 83, 110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dou, W.; Tong, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhu, H.; Xu, R.; Yan, N. Optimal Configuration Method of Electric Vehicle’s Participating in Load Aggregator’s VPP Low-Carbon Economy. Energy Rep. 2023, 9, 1093–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Zhao, H.; Lu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, J. Decentralized Coordinated Operation Model of VPP and P2H Systems Based on Stochastic-Bargaining Game Considering Multiple Uncertainties and Carbon Cost. Appl. Energy 2022, 312, 118750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Li, M.; Wang, R.; Feng, J.; Dong, C.; Sun, Q. Low-Carbon Operation of Multi-Virtual Power Plants with Hydrogen Doping and Load Aggregator Based on Bilateral Cooperative Game. Energy 2024, 309, 132984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Wang, M.; Shen, Y.; Li, F.; Lin, S.; Zhou, B. Low-Carbon Operation Strategy of Virtual Power Plant Considering Progressive Demand Response. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2024, 161, 110176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W.; Yang, Q. Low Carbon Oriented Collaborative Energy Management Framework for Multi-Microgrid Aggregated Virtual Power Plant Considering Electricity Trading. Appl. Energy 2023, 351, 121906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, J.; Wu, Y.; Yong, X.; Tan, Q.; Liu, F. Bi-Level Optimization of a Near-Zero-Emission Integrated Energy System Considering Electricity-Hydrogen-Gas Nexus: A Two-Stage Framework Aiming at Economic and Environmental Benefits. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 274, 116434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, X.; Lu, W.; Wu, J.; Wang, C.; Zhao, X.; Hu, W.; Shen, Y. Real-Time Pricing Method for VPP Demand Response Based on PER-DDPG Algorithm. Energy 2023, 271, 127036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Sun, H. Competitive Pricing Game of Virtual Power Plants: Models, Strategies, and Equilibria. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 13, 4583–4595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Q.-H. Hybrid Stochastic–Information Gap Decision Theory Method for Robust Operation of Water–Energy Nexus Considering Leakage. Electronics 2025, 14, 2644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Awami, A.T.; Amleh, N.A.; Muqbel, A.M. Optimal Demand Response Bidding and Pricing Mechanism with Fuzzy Optimization: Application for a Virtual Power Plant. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2017, 53, 5051–5061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, C.; Zhou, T.; Chen, Q.; Wang, J.; Sun, Y.; Xia, Q. Carbon Emission Flow from Generation to Demand: A Network-Based Model. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2015, 6, 2386–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, N.; Wang, F. Precision and Accuracy Co-Optimization-Based Demand Response Baseline Load Estimation Using Bidirectional Data. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 14, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Ge, X.; Li, K.; Mi, Z. Day-Ahead Market Optimal Bidding Strategy and Quantitative Compensation Mechanism Design for Load Aggregator Engaging Demand Response. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2019, 55, 5564–5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. IPCC Special Report on Renewable Energy Sources and Climate Change Mitigation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kouloumpis, V.; Soboloewski, R.; Yan, X. Performance and life cycle assessment of a small scale vertical axis wind turbine. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lombardi, L.; Mendecka, B.; Carnevale, E.; Stanek, W. Environmental impacts of an innovative micro-wind turbine. Renew. Energy 2018, 127, 1011–1020. [Google Scholar]

- Varun; Prakash, R.; Bhat, I.K. Life cycle greenhouse gas emissions estimation for small hydropower schemes in India. Energy 2012, 44, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, L. Study on carbon emissions of a small hydropower plant in Southwest China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1462571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NREL. Life Cycle Greenhouse Gas Emissions from Electricity Generation: Update; Technical Report NREL/FS-6A20-80580; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Gong, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, Q.; Tan, Q.; Liu, Y.; Ma, C. A review of how life cycle assessment has been used to assess the environmental impacts of hydropower energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 167, 112684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, C.; Li, K.; Qian, T.; Shahidehpour, M. Generalized User Equilibrium for Coordination of Coupled Power-Transportation Network. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2022, 14, 2140–2151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wu, S.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Gomes, L. Intelligent Scheduling Method for Bulk Cargo Terminal Loading Process Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Electronics 2022, 11, 1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pecan Street Inc. Pecan Street Dataport. 2020. Available online: https://dataport.pecanstreet.org/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Zhang, Y.; Ge, X.; Li, M.; Li, N.; Wang, F.; Wang, L. Demand Response Potential Day-Ahead Forecasting Approach Based on LSSA-BPNN Considering the Electricity-Carbon Coupling Incentive Effects. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 4505–4516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Wang, J.; Li, G.; Zhang, X.; Ge, X.; Wang, J. Day-Ahead Demand Response Potential Forecasting Model Considering Dynamic Spatial-Temporal Correlation Based on Directed Graph Structure. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2023, 60, 2165–2175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Zone Number | Nodes Involved | Zone Type | Load Capacity/kWh |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | B1, B2, B3, B4 | Residential | 317.75 |

| Zone 2 | B5, B6, B7, B8, B9, B10 | Industrial | 1209.15 |

| Zone 3 | B11, B12, B13, B14, B16, B17 | Industrial | 941.802 |

| Zone 4 | B15, B18, B19, B20, B21, B22 | Commercial | 888.25 |

| Zone 5 | B23, B24, B25, B26, B28 | Commercial | 602.8 |

| Zone 6 | B27, B29, B30 | Residential | 2502.85 |

| Unit | /(MW) | /(MW/h) | Cost Coefficients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /(USD/MWh2) | /(USD/MWh) | /USD | |||

| DG1 | [3, 6] | 1.5 | 0.27 | 60 | 3.4 |

| DG2 | [2, 5] | 1.5 | 0.3 | 56.5 | 3.0 |

| Item | Value | Item | Value | Item | Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [0.2, 0.9] | 3 MW | 15 MWh | |||

| 0.5 | 0.95 | 0.5 USD/MWh |

| Original Average Load (kWh) | Optimized Average Load (kWh) | Load Change Amount (kWh) | Load Change Rate | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VPP 1 | 75,120.81 | 29,112.73 | −46,008.08 | −61.25% |

| VPP 2 | 1913.23 | 8064.18 | 6150.95 | 321.50% |

| VPP 3 | 2026.20 | 1784.56 | −241.64 | −11.93% |

| VPP 4 | 6660.28 | 30,265.27 | 23,604.99 | 354.41% |

| VPP 5 | 21.96 | 8643.27 | 8621.30 | 39,255.95% |

| VPP 6 | 2337.27 | 8531.98 | 6194.70 | 265.04% |

| Total | 88,079.75 | 86,401.97 | −1677.78 | −1.90% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhao, Z.; Bo, B.; Li, X.; Yang, P.; Jiang, D.; Wang, G.; Wang, F. A Non-Cooperative Game-Based Retail Pricing Model for Electricity Retailers Considering Low-Carbon Incentives and Multi-Player Competition. Electronics 2025, 14, 4713. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234713

Zhao Z, Bo B, Li X, Yang P, Jiang D, Wang G, Wang F. A Non-Cooperative Game-Based Retail Pricing Model for Electricity Retailers Considering Low-Carbon Incentives and Multi-Player Competition. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4713. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234713

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhao, Zhiyu, Bo Bo, Xuemei Li, Po Yang, Dafei Jiang, Ge Wang, and Fei Wang. 2025. "A Non-Cooperative Game-Based Retail Pricing Model for Electricity Retailers Considering Low-Carbon Incentives and Multi-Player Competition" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4713. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234713

APA StyleZhao, Z., Bo, B., Li, X., Yang, P., Jiang, D., Wang, G., & Wang, F. (2025). A Non-Cooperative Game-Based Retail Pricing Model for Electricity Retailers Considering Low-Carbon Incentives and Multi-Player Competition. Electronics, 14(23), 4713. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234713