A 0.3 V High-Efficiency Bulk-Driven Rail-to-Rail OTA with High Gain-Bandwidth for Wearable Applications

Abstract

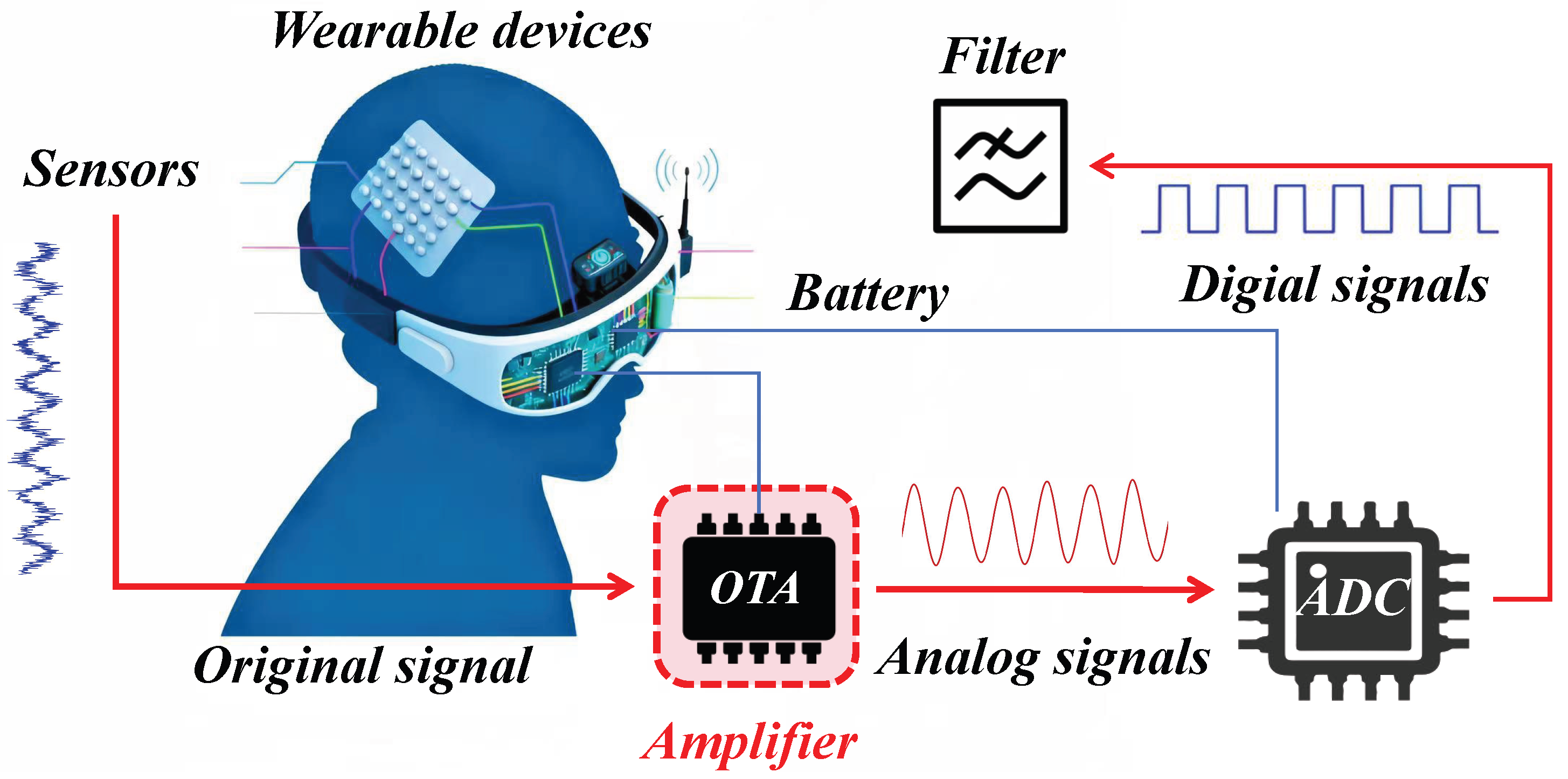

1. Introduction

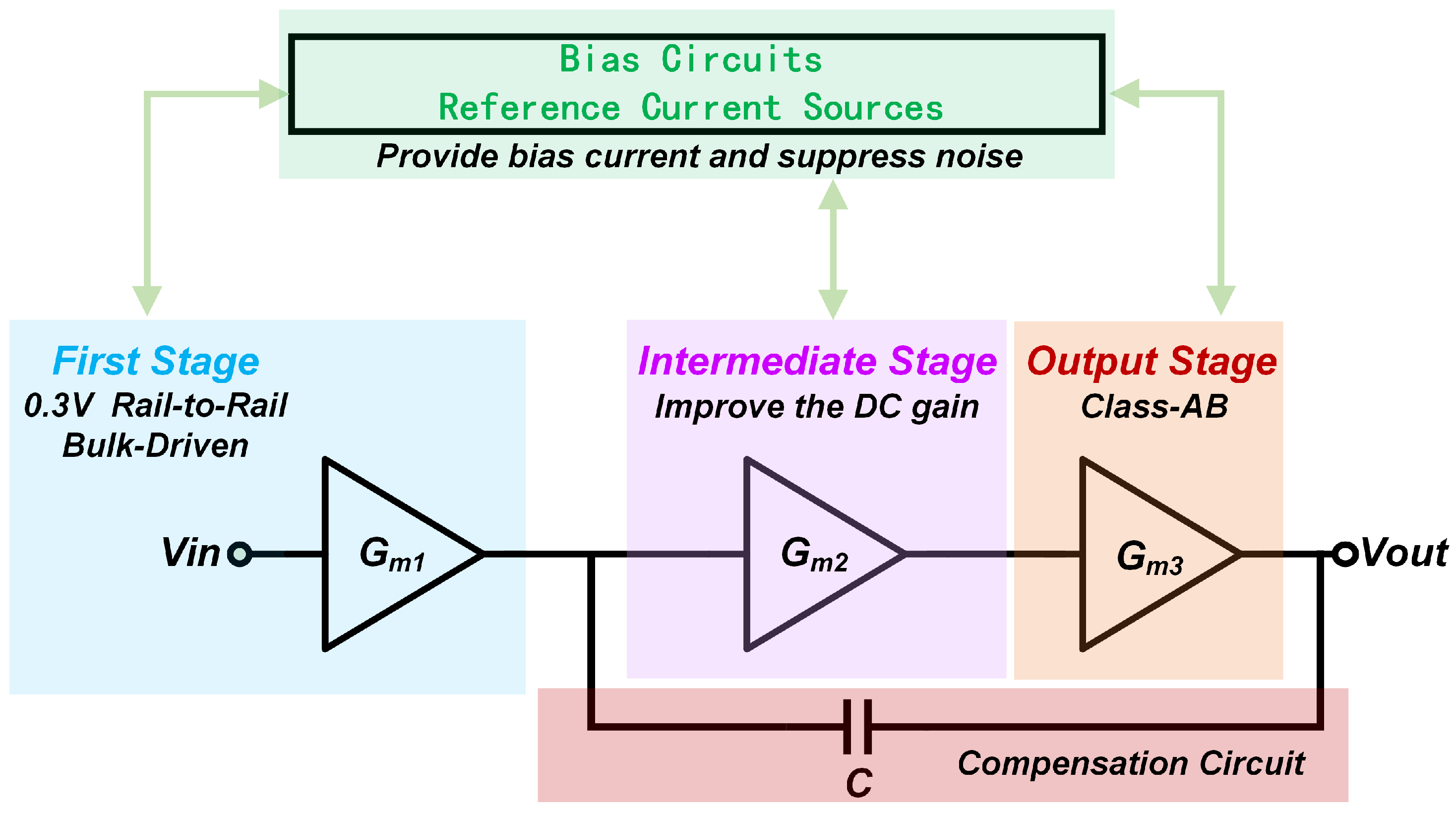

2. Overview of the Proposed OTA

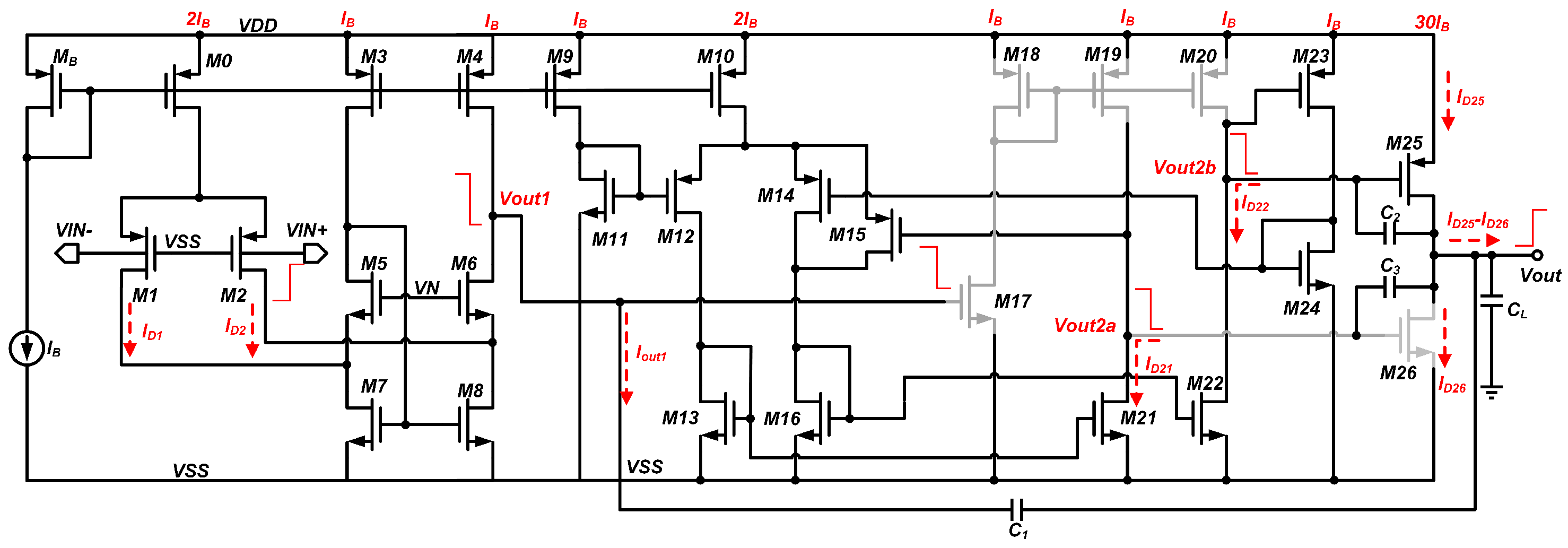

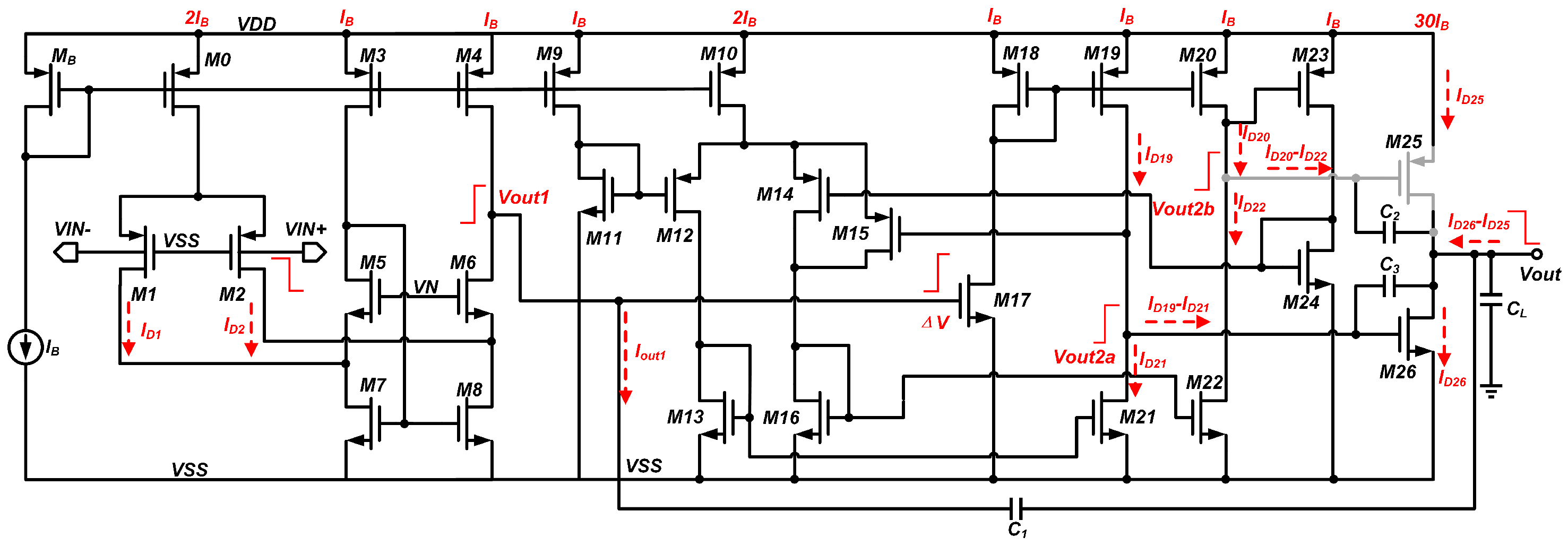

2.1. Overall Circuit

2.2. The Bulk-Driven Input Stage

2.3. Intermediate Stage and Output Stage

2.4. Small-Signal Analysis

2.5. Large-Signal Analysis

3. Simulation and Experimental Results

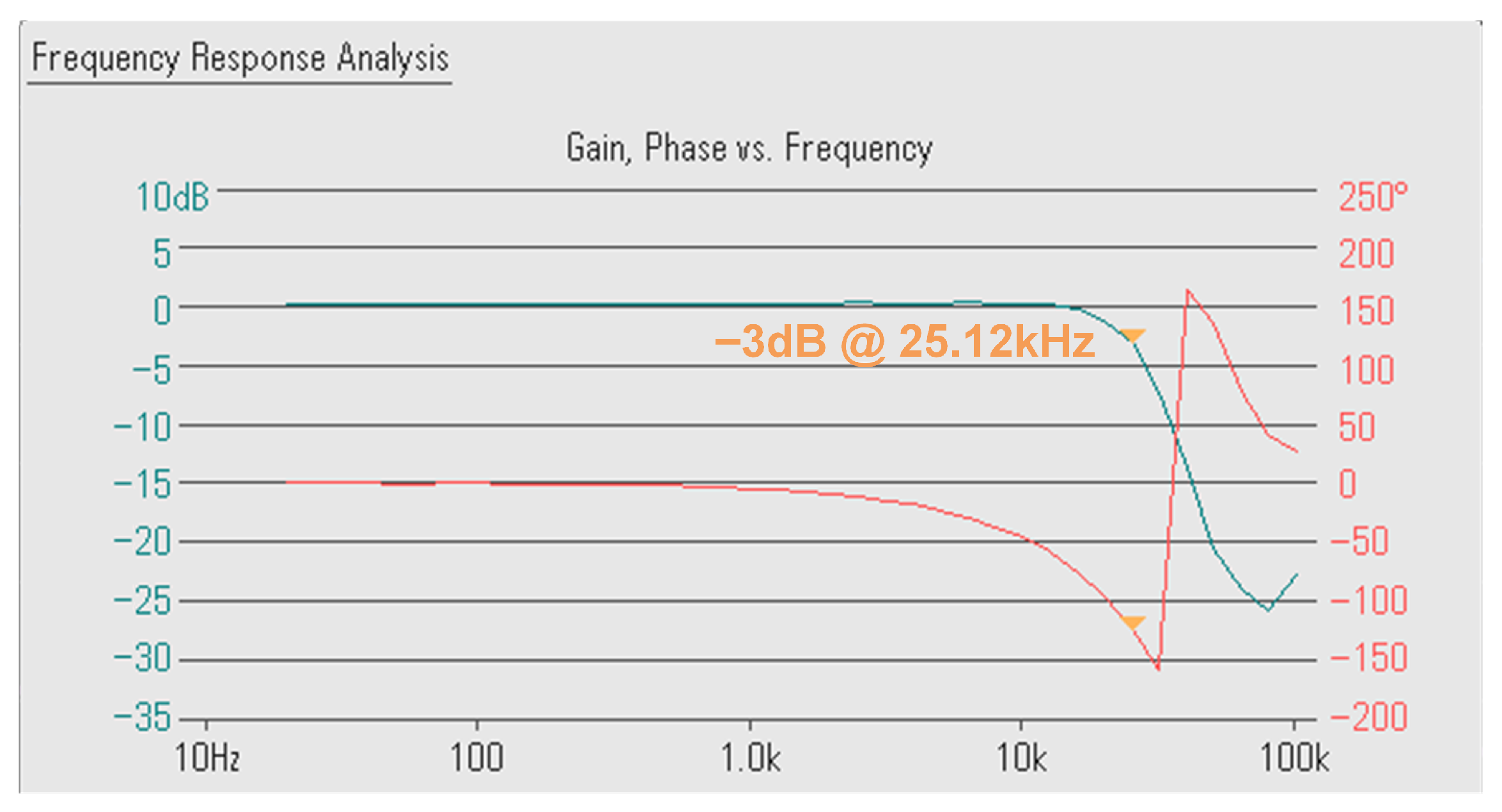

3.1. Simulation Results

3.2. Experimental Results

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jacob Rodrigues, M.; Postolache, O.; Cercas, F. Physiological and behavior monitoring systems for smart healthcare environments: A review. Sensors 2020, 20, 2186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghasemzadeh, H.; Jafari, R. Ultra low-power signal processing in wearable monitoring systems: A tiered screening architecture with optimal bit resolution. ACM Trans. Embed. Comput. Syst. 2013, 13, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, T.; Lee, C. Evolving flexible sensors, wearable and implantable technologies towards bodyNET for advanced healthcare and reinforced life quality. IEEE Open J. Circuits Syst. 2021, 2, 702–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelfattah, O.; Roberts, G.W.; Shih, I.; Shih, Y.C. An ultra-low-voltage CMOS process-insensitive self-biased OTA with rail-to-rail input range. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2015, 62, 2380–2390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, R.; Moradi, F.; Heidari, H. Biointegrated and wirelessly powered implantable brain devices: A review. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2020, 14, 343–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Wang, T.; Wei, X.; Yue, H.; Wei, B.; Duan, J.; Li, H. Low noise, high input impedance digital-analog hybrid offset suppression amplifier for wearable dry electrode ECG monitoring. Electronics 2020, 9, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Tanaka, A.; Takaya, N.; Yoshizawa, H. 0.5-V 70-nW Rail-to-rail operational amplifier using a cross-coupled output stage. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2016, 63, 1009–1013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horestani, F.K.; Eshghi, M.; Yazdchi, M. An ultra-low power amplifier for wearable and implantable electronic devices. Microelectron. Eng. 2019, 216, 111054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duch, L.; Basu, S.; Braojos, R.; Ansaloni, G.; Pozzi, L.; Atienza, D. HEAL-WEAR: An Ultra-Low Power Heterogeneous System for Bio-Signal Analysis. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2017, 64, 2448–2461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Qu, T.; Pan, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Li, Y.; Zhou, J.; Yao, C.; Hong, Z. Analog Front-End Circuit Techniques for Wearable ExG, BioZ, and PPG Signal Acquisition: A Review. IEEE Open J.-Solid-State Circuits Soc. 2025, 5, 251–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, A.D.; Marano, D.; Palumbo, G.; Pennisi, S. Design methodology of subthreshold three-stage CMOS OTAs suitable for ultra-low-power low-area and high driving capability. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2015, 62, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, A.D.; Pennisi, S. Ultra-low power amplifiers for IoT nodes. In Proceedings of the 2018 25th IEEE International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Systems (ICECS), Bordeaux, France, 9–12 December 2018; pp. 497–500. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee, S.; Tsividis, Y.; Kinget, P. Ultra-low voltage analog integrated circuits. IEICE Trans. Electron. 2006, 89, 673–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, M.H.; Park, C.; Prakash, S.; Kinyua, M.; Soenen, E.G.; Silva-Martinez, J. A 27.7 fJ/conv-step 500 MS/s 12-bit pipelined ADC employing a sub-ADC forecasting technique and low-power class AB slew boosted amplifiers. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2019, 66, 3352–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagliardi, F.; Catania, A.; Piotto, M.; Bruschi, P.; Dei, M. Parallel Slew-Rate Enhancer With Current-Recycling Core for Switched-Capacitors Circuits. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2024, 71, 4814–4818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballo, A.; Grasso, A.D.; Pennisi, S. 0.4-V, 81.3-nA bulk-driven single-stage CMOS OTA with enhanced transconductance. Electronics 2022, 11, 2704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khateb, F.; Kumngern, M.; Kulej, T.; Biolek, D. 0.5 V Differential difference transconductance amplifier and its application in voltage-mode universal filter. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 43209–43220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centurelli, F.; Della Sala, R.; Monsurro, P.; Tommasino, P.; Trifiletti, A. An ultra-low-voltage class-AB OTA exploiting local CMFB and body-to-gate interface. AEU-Int. J. Electron. Commun. 2022, 145, 154081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Hussein, S.M.; Hashim, Y.; Tang, K.T. 0.4-V Tail-less quasi-two-stage OTA using a novel self-biasing transconductance cell. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2022, 69, 2805–2818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulej, T.; Khateb, F.; Arbet, D.; Stopjakova, V. A 0.3-V high linear rail-to-rail bulk-driven OTA in 0.13 μm CMOS. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2022, 69, 2046–2050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, K.C.; Yang, B.D. A 0.25-V rail-to-rail three-stage OTA with an enhanced DC gain. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2019, 67, 1179–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, M.; Hussein, S.M.; Hashim, Y.; Tang, K.T. An enhanced input differential pair for low-voltage bulk-driven amplifiers. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 2021, 29, 1601–1611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Sala, R.; Centurelli, F.; Scotti, G.; Tommasino, P.; Trifiletti, A. A differential-to-single-ended converter based on enhanced body-driven current mirrors targeting ultra-low-voltage OTAs. Electronics 2022, 11, 3838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Della Sala, R.; Centurelli, F.; Monsurrò, P.; Scotti, G.; Trifiletti, A. A 0.3 V rail-to-rail three-stage OTA with high DC gain and improved robustness to PVT variations. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 19635–19644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballo, A.; Grasso, A.D.D.; Pennisi, S.; Susinni, G. A 0.3-V 8.5-μ A bulk-driven OTA. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 2023, 31, 1444–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballo, A.; Carvajal, R.G.; Grasso, A.D.; Luján-Martínez, C.I.; Pennisi, S.; Venezia, C. 0.35 V SR-enhanced bulk-driven OTA for loads up to 10 nF. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 71, 6410–6418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centurelli, F.; Della Sala, R.; Monsurrò, P.; Scotti, G.; Trifiletti, A. A 0.3 V rail-to-rail ultra-low-power OTA with improved bandwidth and slew rate. J. Low Power Electron. Appl. 2021, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulej, T.; Khateb, F. Design and implementation of sub 0.5 V OTAs in 0.18-μm CMOS. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2018, 46, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulej, T.; Khateb, F. A compact 0.3-V Class AB bulk-driven OTA. IEEE Trans. Very Large Scale Integr. Syst. 2019, 28, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| MOSFET | W/L(m/m) | MOSFET | W/L(m/m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| M0, M3, M4, M9, M10 | 0.3/1 | M12, M14, M15 | 4/1 |

| M1, M2, M18, M19, M20 | 0.5/1 | M13, M16, M21, M22, M24 | 3/1 |

| M5, M6 | 3/0.9 | M17 | 0.7/1 |

| M7, M8 | 1.8/1 | M23, M25 | 0.8/1 |

| M11 | 5/1 | M26 | 5/1 |

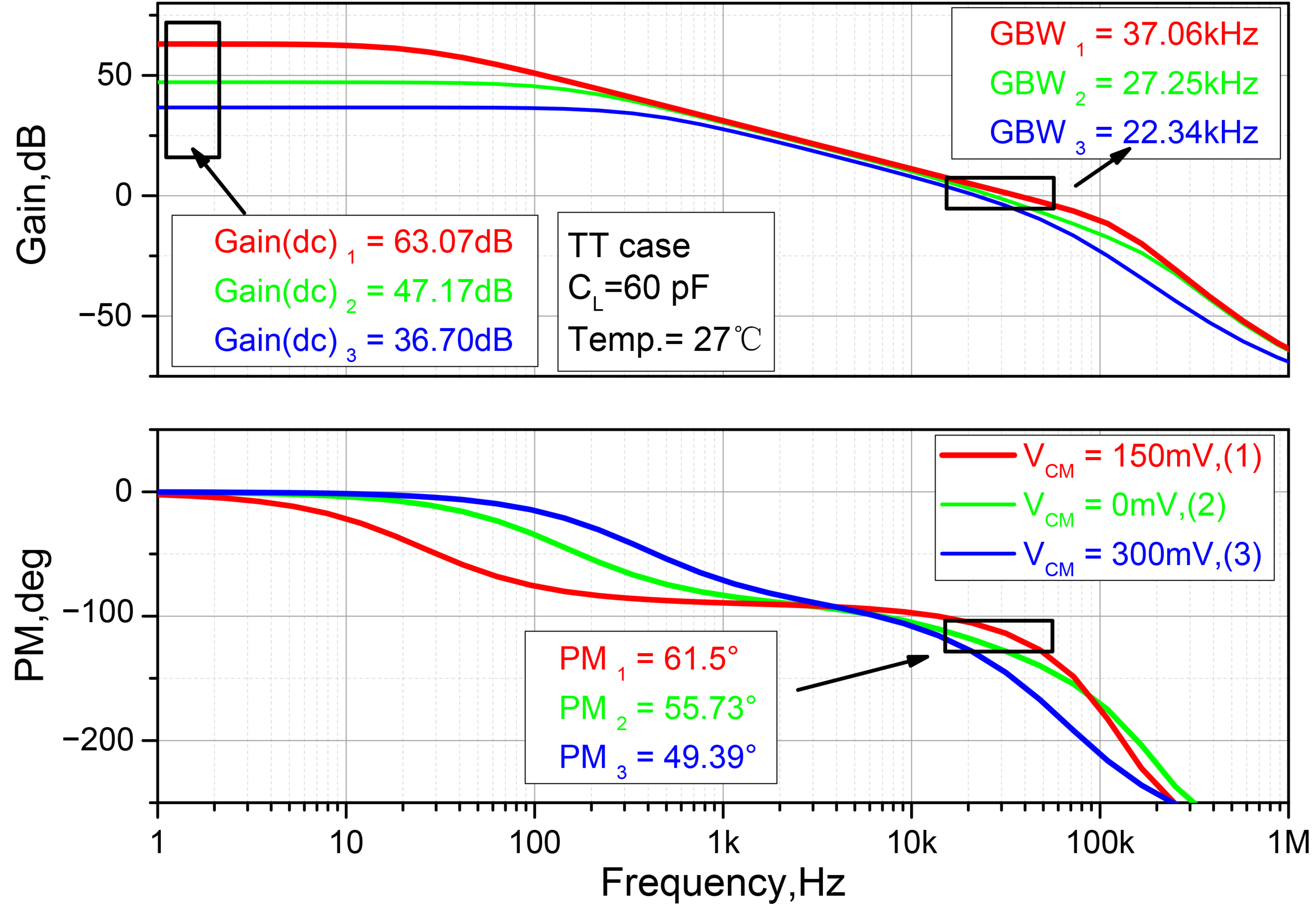

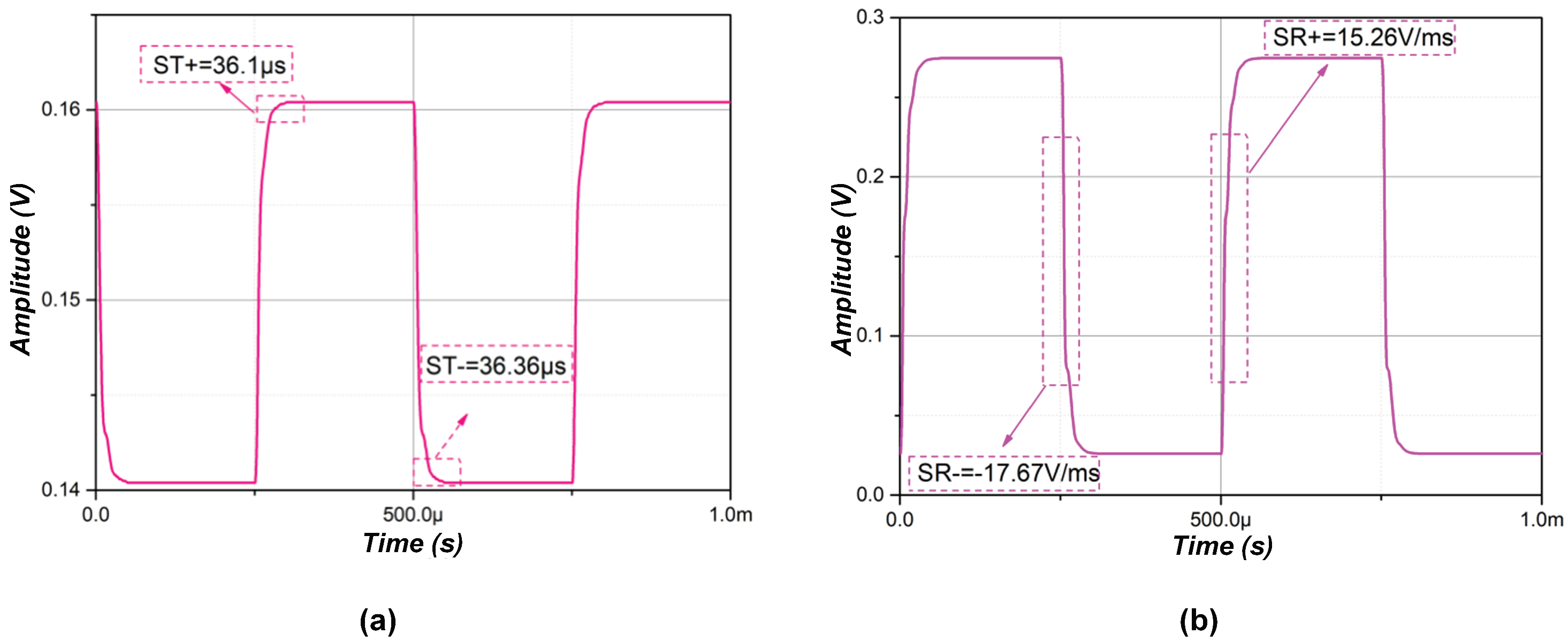

| TT | FF | SS | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | −25 °C | −27 °C | −50 °C | −25 °C | −27 °C | −50 °C | −25 °C | −27 °C | −50 °C |

| ICMR (mV) | 5.45–299.7 | 2.25–298.5 | 21.4–271.3 | 10.2–299.7 | 6.9–250 | 10.88–295.3 | 19.6–299.7 | 10–289.8 | 10.03–287.1 |

| Swing (mV) | 2.65–272.4 | 4.27–299.7 | 70.73–291.6 | 1.41–294.15 | 3.56–296.25 | 4.51–296.7 | 15.42–296.4 | 5.18–296.7 | 13.52–296.7 |

| DC gain (dB) | 69.32 | 63.07 | 45.99 | 32.98 | 28.38 | 25.8 | 69.32 | 67.13 | 66.19 |

| PM (°) | 57.2 | 61.5 | 71.41 | 48.13 | 80.3 | 65.2 | 42.18 | 47.42 | 54.64 |

| GBW (kHz) | 48.46 | 43.91 | 20.99 | 7.62 | 9.95 | 8.2 | 35.07 | 36.37 | 38.64 |

| CMRR (dB) | 75.01 | 69.89 | 26.35 | 45.72 | 41.47 | 42.25 | 50.36 | 52.79 | 65.74 |

| PSRR (dB) | 30.12 | 57.34 | 15.03 | 20.96 | 7.01 | 15.1 | 19.96 | 28.11 | 20.82 |

| ST (s) | 42.95/47.87 | 36.1/36.36 | 54.44/53.73 | 93.54/115.24 | 96.72/112 | 90.29/110 | 45.16/40.28 | 38.25/38.05 | 40.36/39.31 |

| SR (V/ms) | 20.89/−25.95 | 18.22/−20.11 | 11.42/−11.09 | 2.69/−2.6 | 4.65/−4.9 | 21.88/−24.93 | 25.16/−13.78 | 21.54/−14.92 | 16.58/−14.63 |

| Ref. | [28] | [29] | [22] | [27] | [23] | [24] | [26] | This Work |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2018 | 2020 | 2021 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | |

| Tech. (nm) | 180 | 180 | 180 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 65 | |

| Area () | 8.2 | 8.5 | 19 | 3.6 | 2.35 | 2.34 | 52 | |

| Supply Voltage (V) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.35 | |

| Power (nW) | 15.4 | 12.6 | 45.5 | 73 | 33.73 | 33.73 | 490 | |

| CL (pF) | 20 | 30 | 15 | 40 | 250 | 35 | 300 | |

| DC gain (dB) | 65.8 | 64.7 | 78 | 40.8 | 41.28 | 86.83 | 55 | |

| PM (deg) | 61 | 52 | 59 | 51.93 | 58.27 | 58.27 | 65 | |

| GBW (kHz) | 2.78 | 2.96 | 7.5 | 18.65 | 7.95 | 10.32 | 15.4 | |

| CMRR (dB) | 72 | 110 | 113.8 | 67.49 | 35.28 | 57.8 | 58 | |

| PSRR (dB) | 62 | 56 | 84.4 | 45 | 74.41 | 46.59 | 26.5 | |

| SR (V/ms) | 7.12 | 4.15 | 8.6 | 21.6 | 1.25 | 3.74 | 14 | |

| FoMS 1 | 3.61 | 7.047 | 2.47 | 10.2 | 16.563 | 10.7 | 9.43 | |

| FoML 2 | 9.25 | 9.88 | 2.84 | 11.82 | 2.604 | 3.88 | 8.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Q. A 0.3 V High-Efficiency Bulk-Driven Rail-to-Rail OTA with High Gain-Bandwidth for Wearable Applications. Electronics 2025, 14, 4702. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234702

Wang Y, Zhang J, Zhang S, Zheng H, Zhang Q. A 0.3 V High-Efficiency Bulk-Driven Rail-to-Rail OTA with High Gain-Bandwidth for Wearable Applications. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4702. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234702

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yongqing, Jinhang Zhang, Shengyan Zhang, Hongjie Zheng, and Qisheng Zhang. 2025. "A 0.3 V High-Efficiency Bulk-Driven Rail-to-Rail OTA with High Gain-Bandwidth for Wearable Applications" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4702. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234702

APA StyleWang, Y., Zhang, J., Zhang, S., Zheng, H., & Zhang, Q. (2025). A 0.3 V High-Efficiency Bulk-Driven Rail-to-Rail OTA with High Gain-Bandwidth for Wearable Applications. Electronics, 14(23), 4702. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234702