Apple Scab Classification Using 2D Shearlet Transform with Integrated Red Deer Optimization Technique in Convolutional Neural Network Models

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Current Approaches in the Literature

1.2. Motivation and Contributions

2. Methodology

2.1. Proposed Framework for Apple Scab Classification Model

2.2. Dataset

2.3. Data Labeling

2.4. Data Augmentation

2.4.1. Rotation

2.4.2. Flipping

2.4.3. Zooming

2.4.4. Shifting

2.4.5. Brightness and Contrast Adjustment

2.4.6. Adding Noise

2.4.7. Adding Salt and Pepper Noise

2.4.8. Cropping

2.5. 2D Shearlet Transform

2.6. Deep Learning Models

2.6.1. AlexNet

2.6.2. VGG-16

2.6.3. ResNet-18

2.7. Red Deer Optimization Method

2.8. Performance Evaluation in Classification Algorithms: Basic Concepts and Formulas

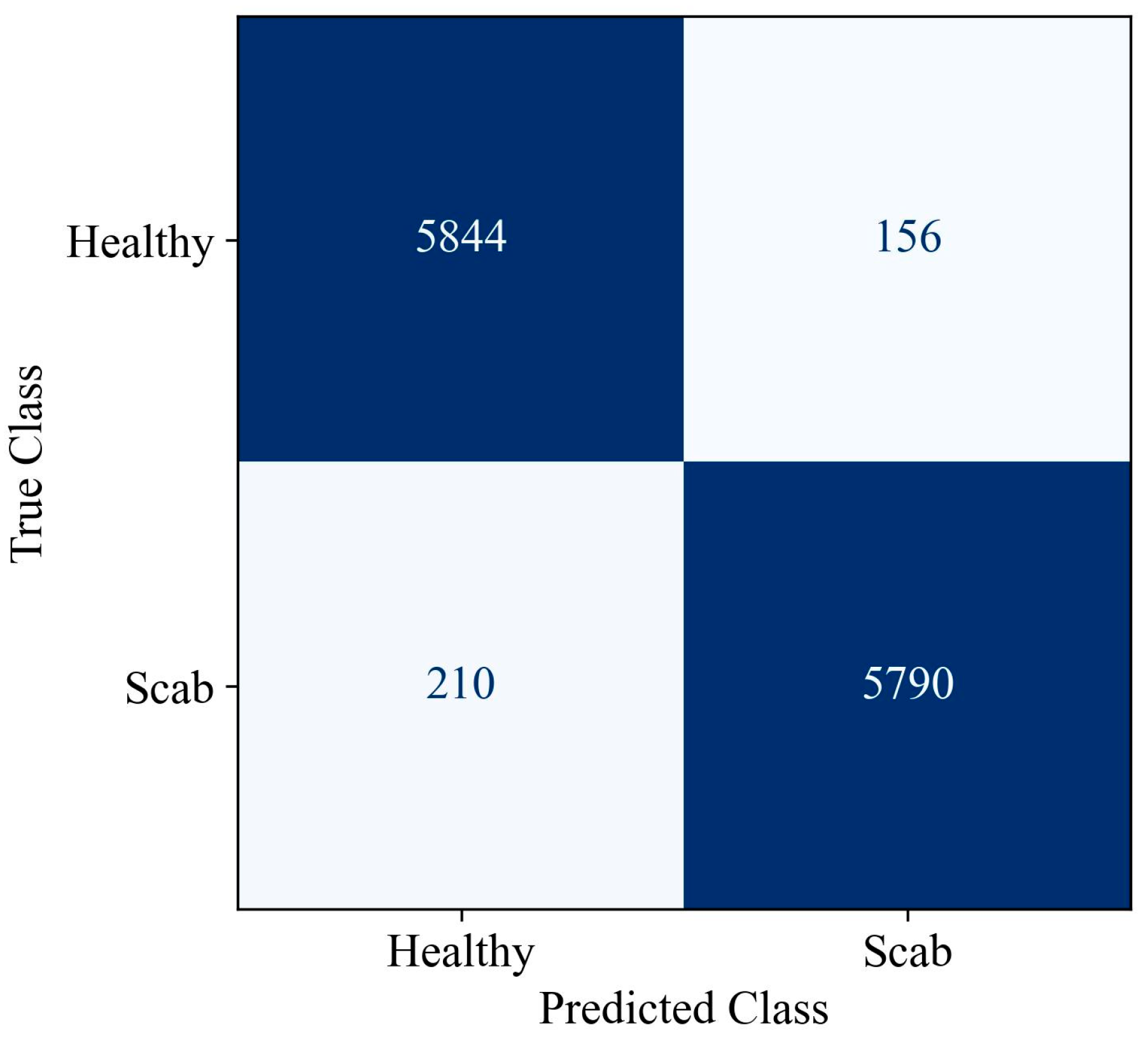

2.8.1. Confusion Matrix

2.8.2. Precision

2.8.3. Recall

2.8.4. F1-Score

2.8.5. Accuracy

2.8.6. Specificity

3. Simulation Study Results

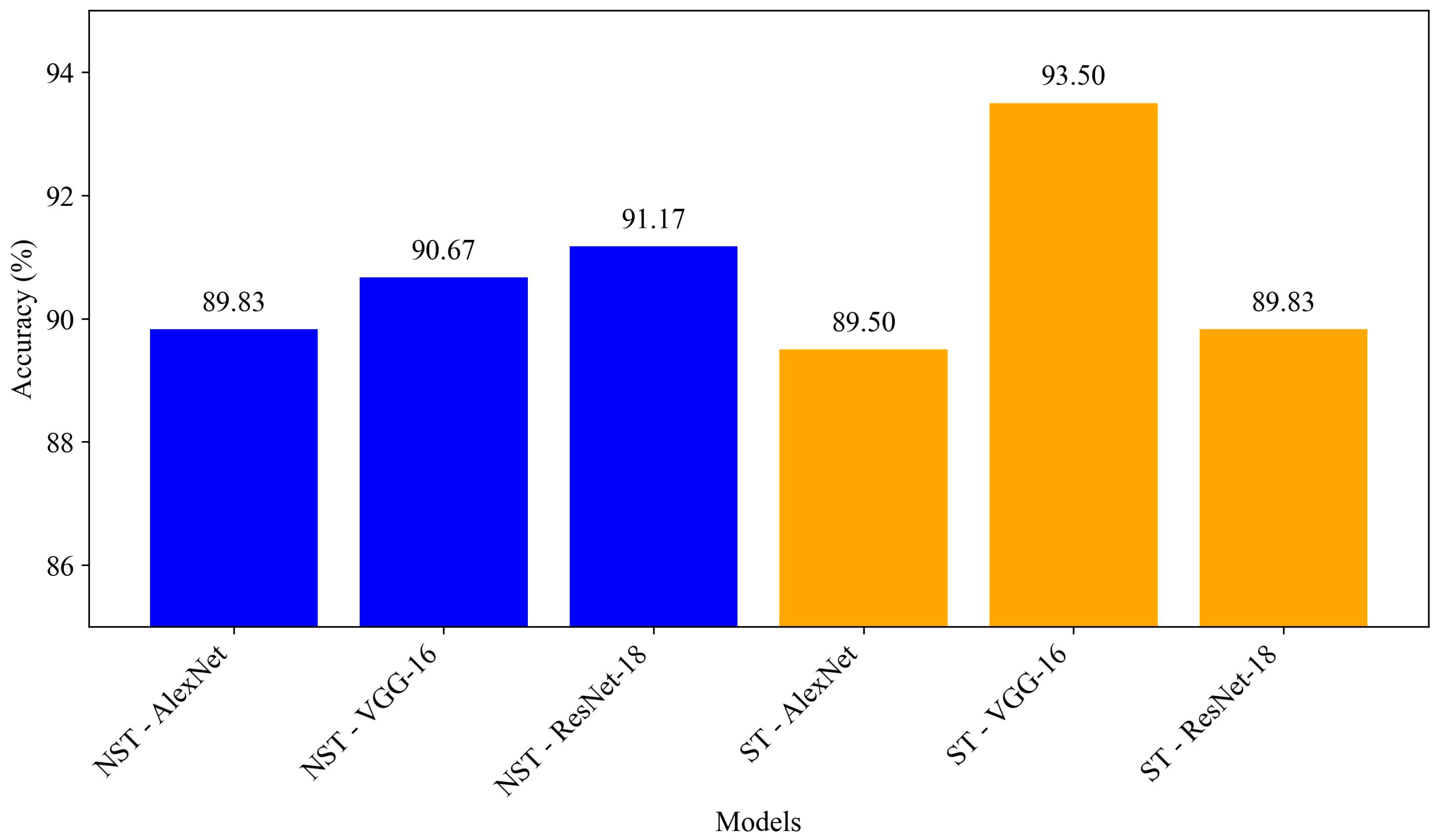

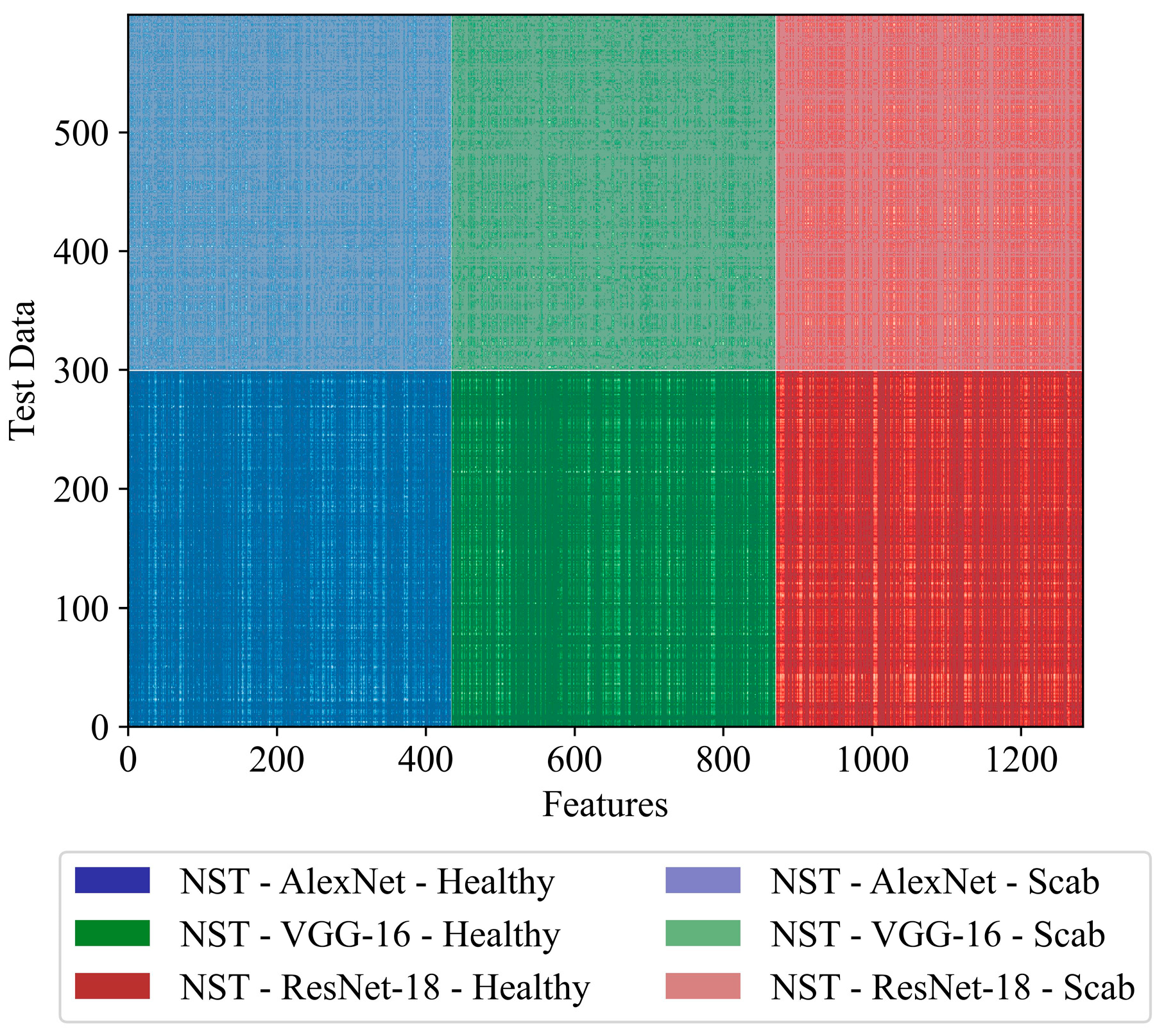

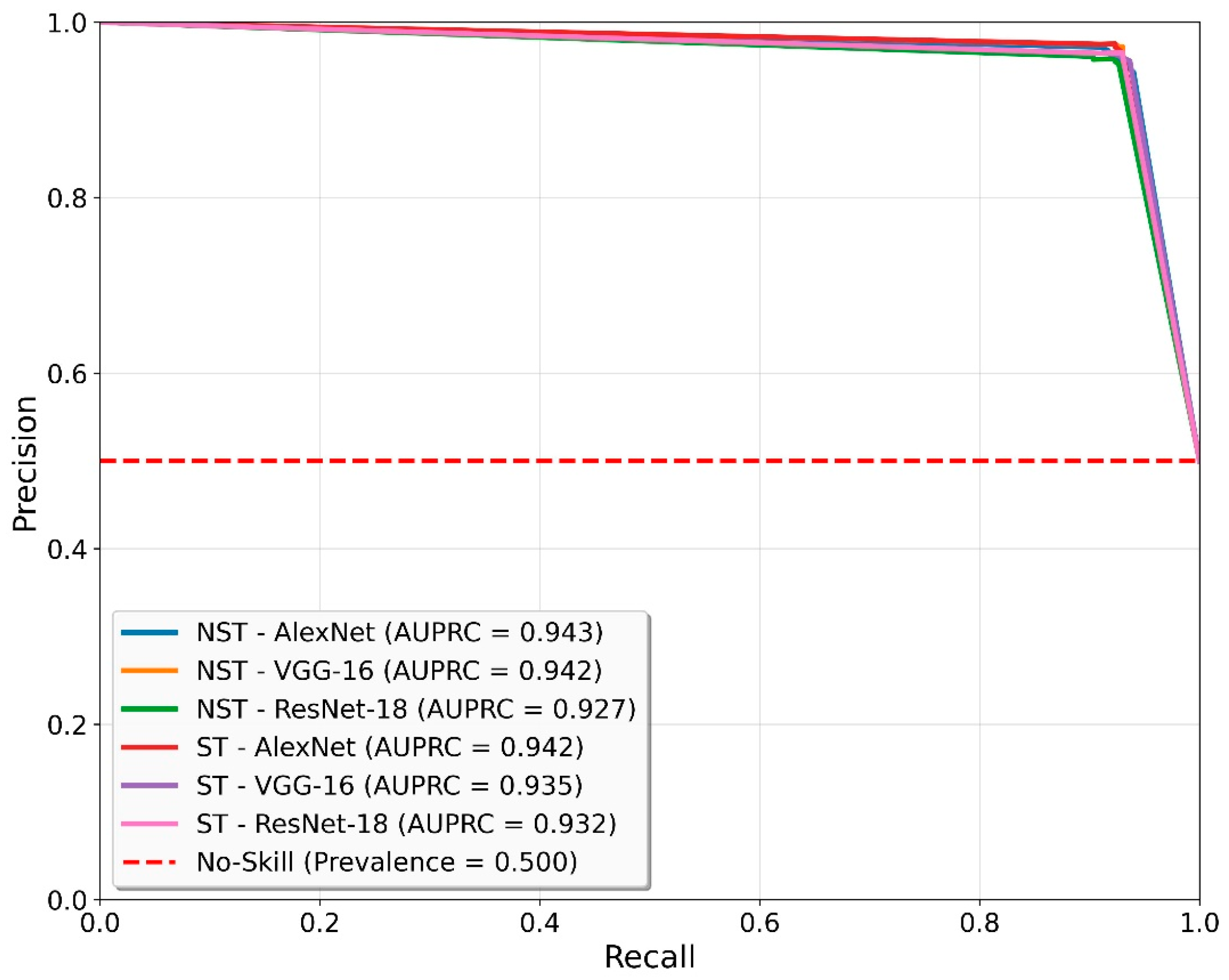

3.1. Single Models

3.1.1. Performances Without Signal Processing

3.1.2. Performances with Signal Processing

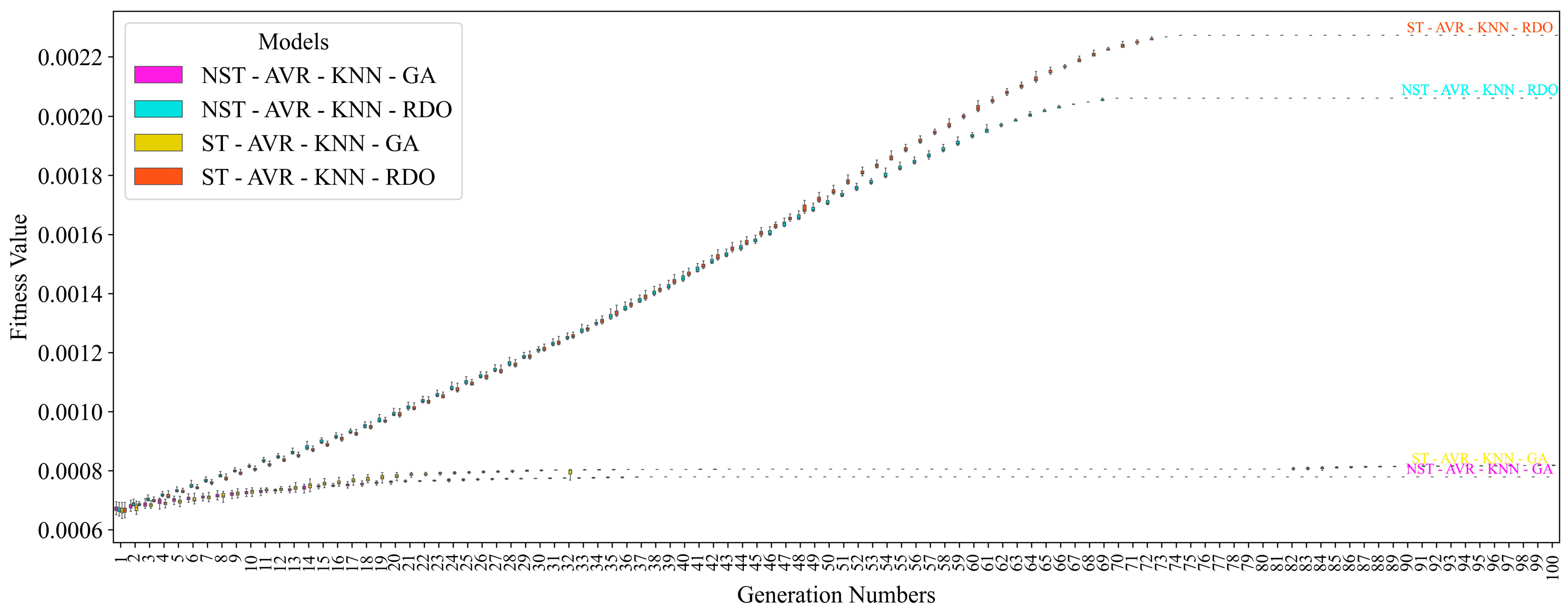

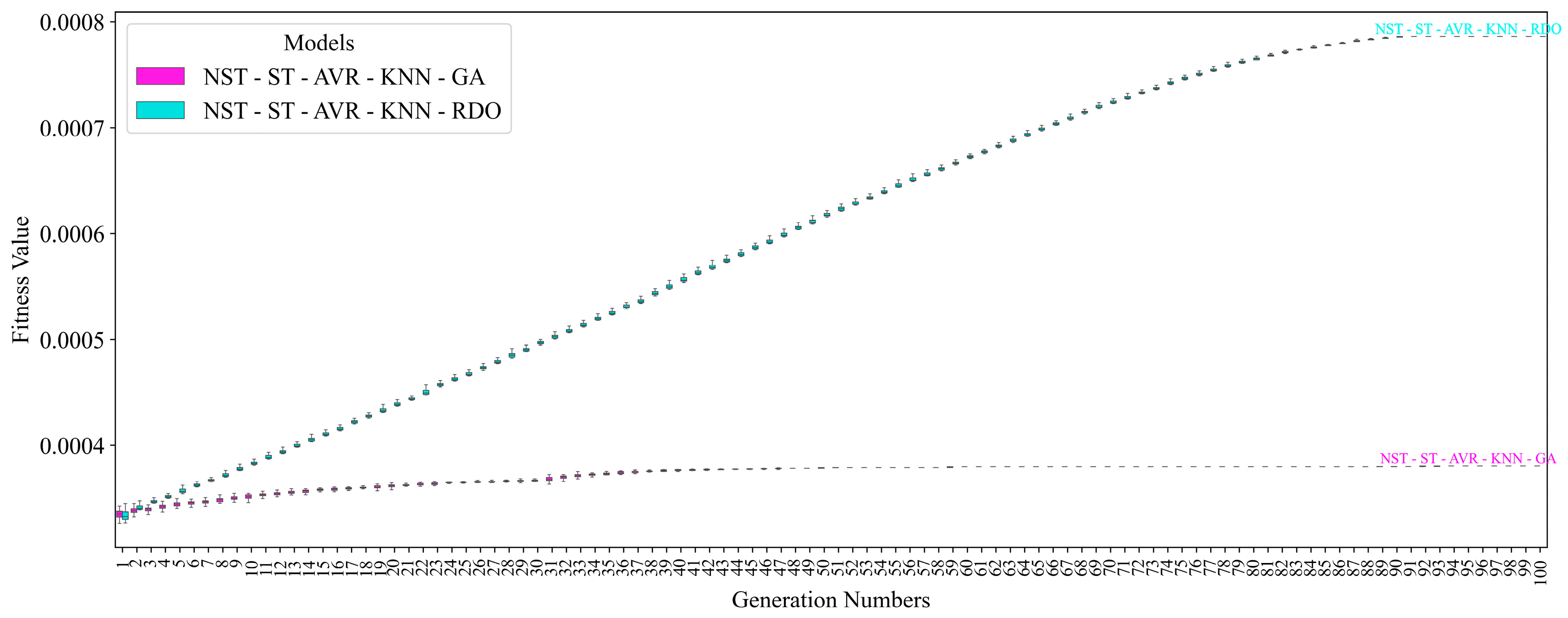

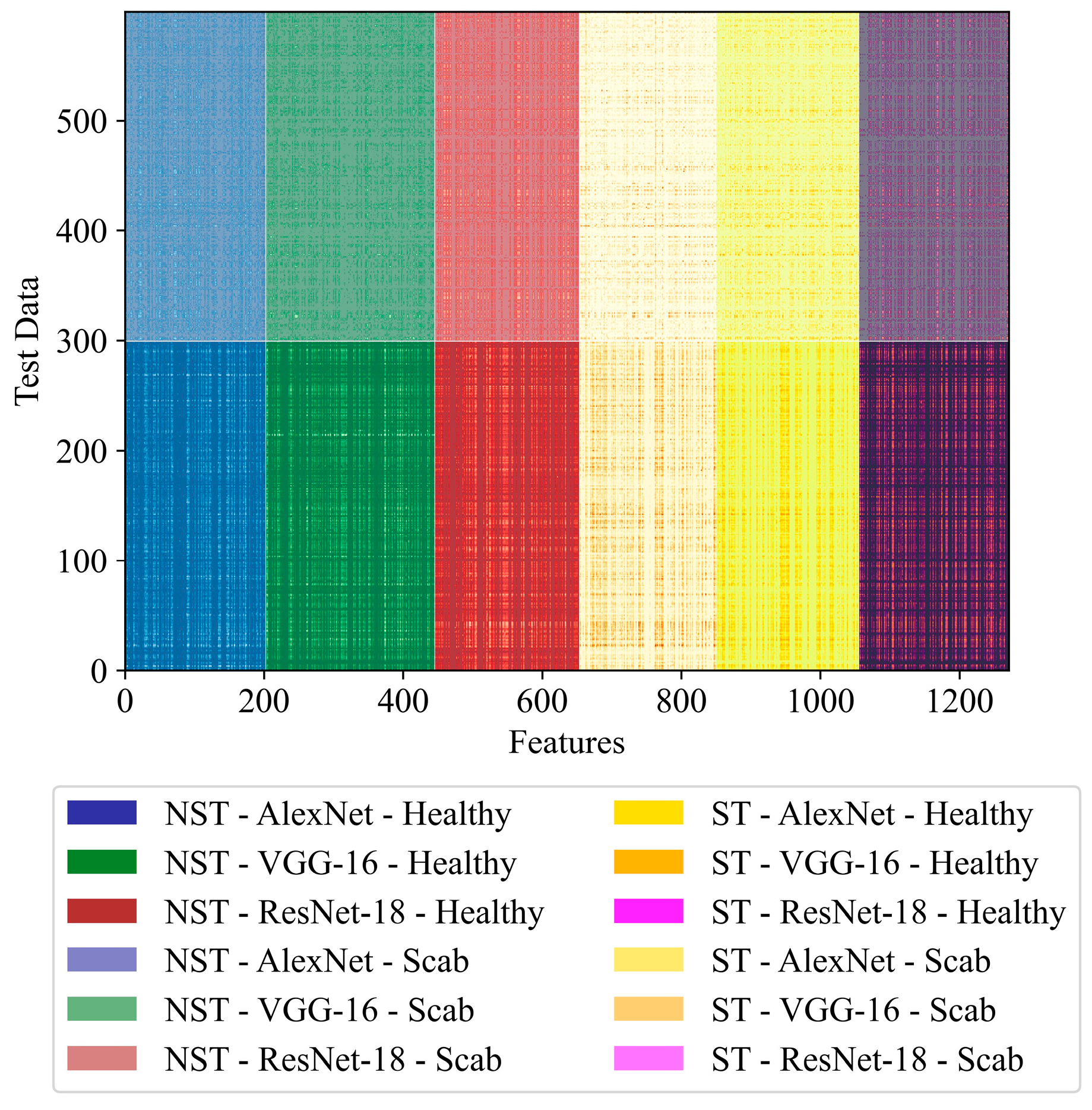

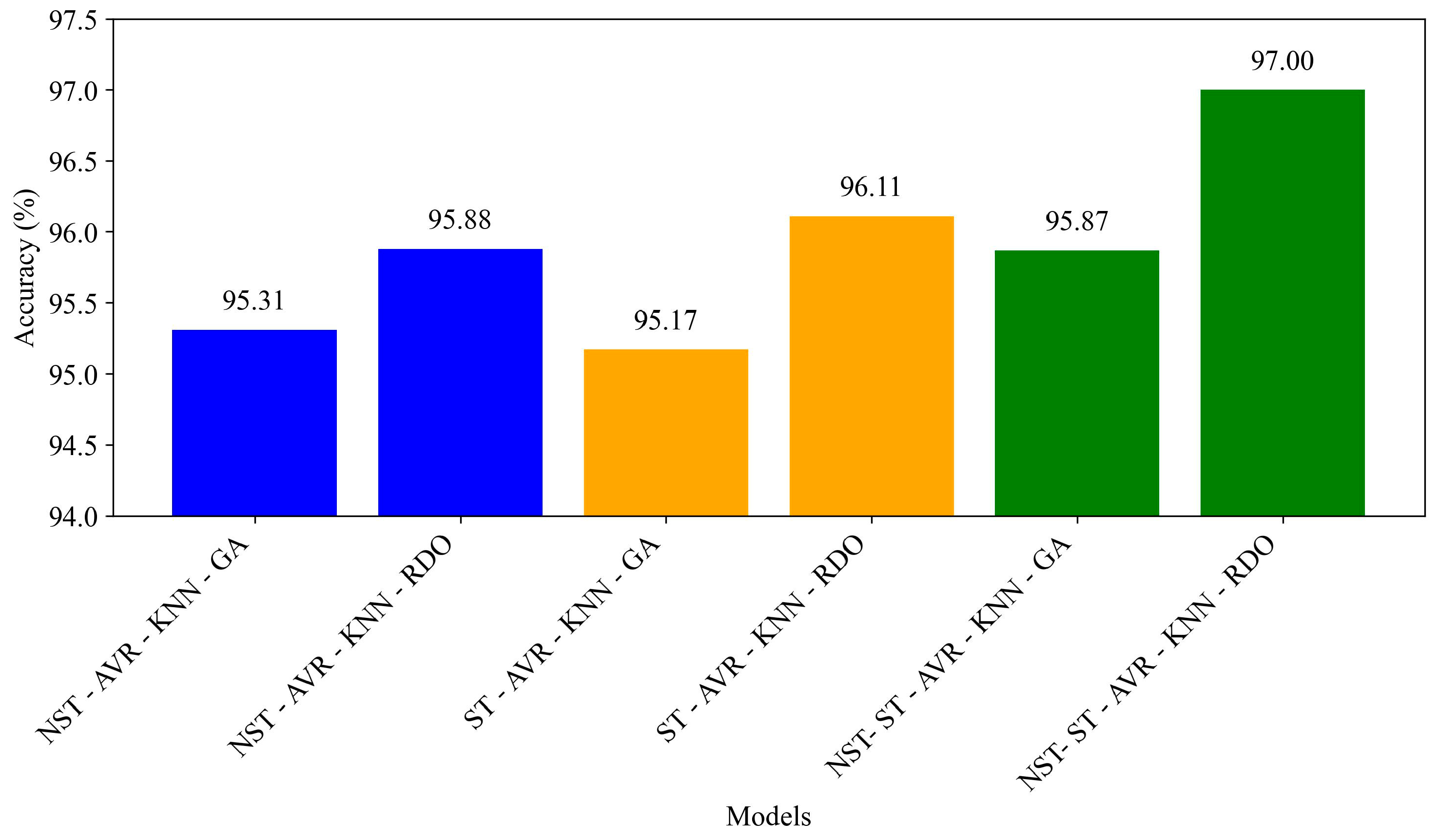

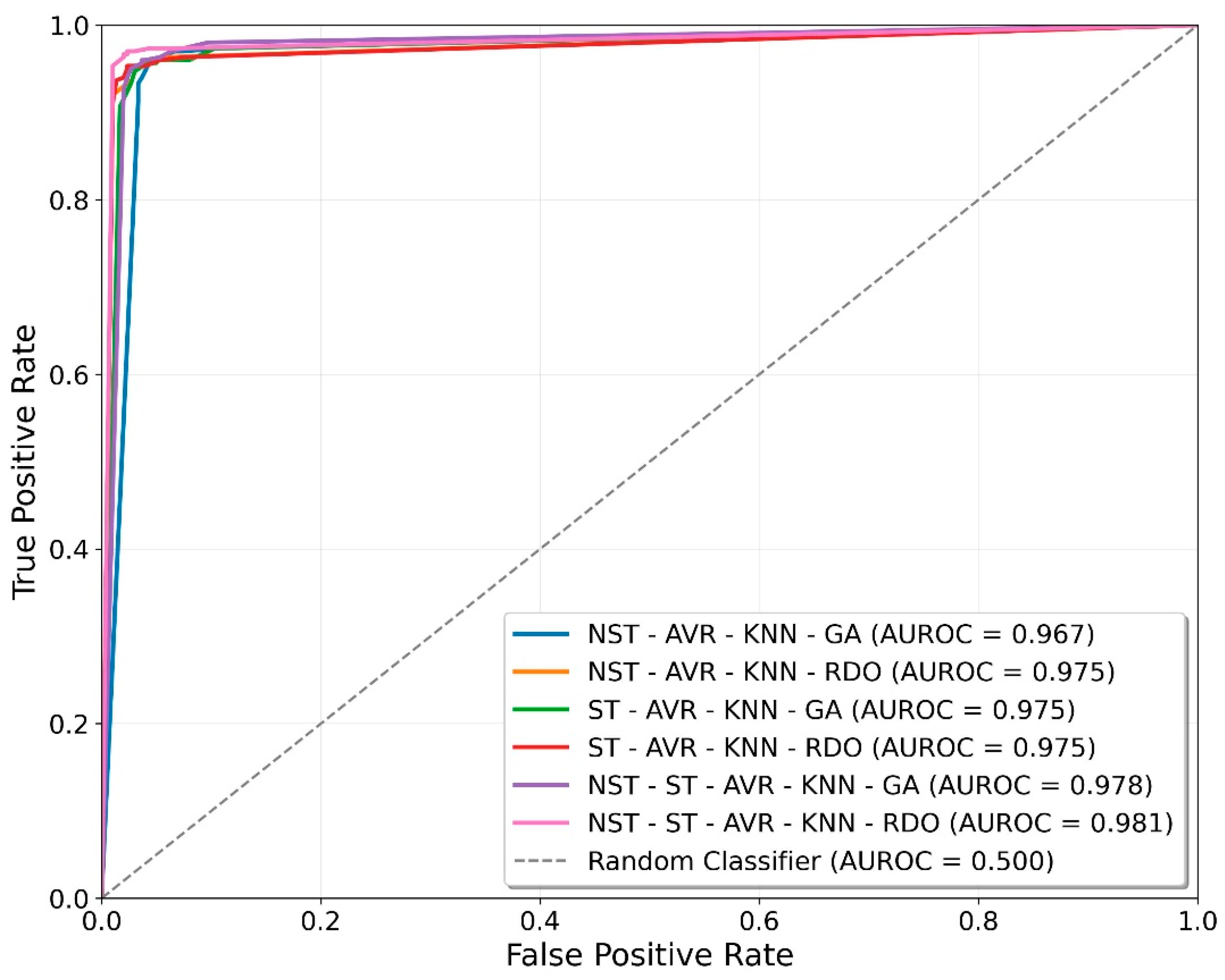

3.2. Hybrid Models

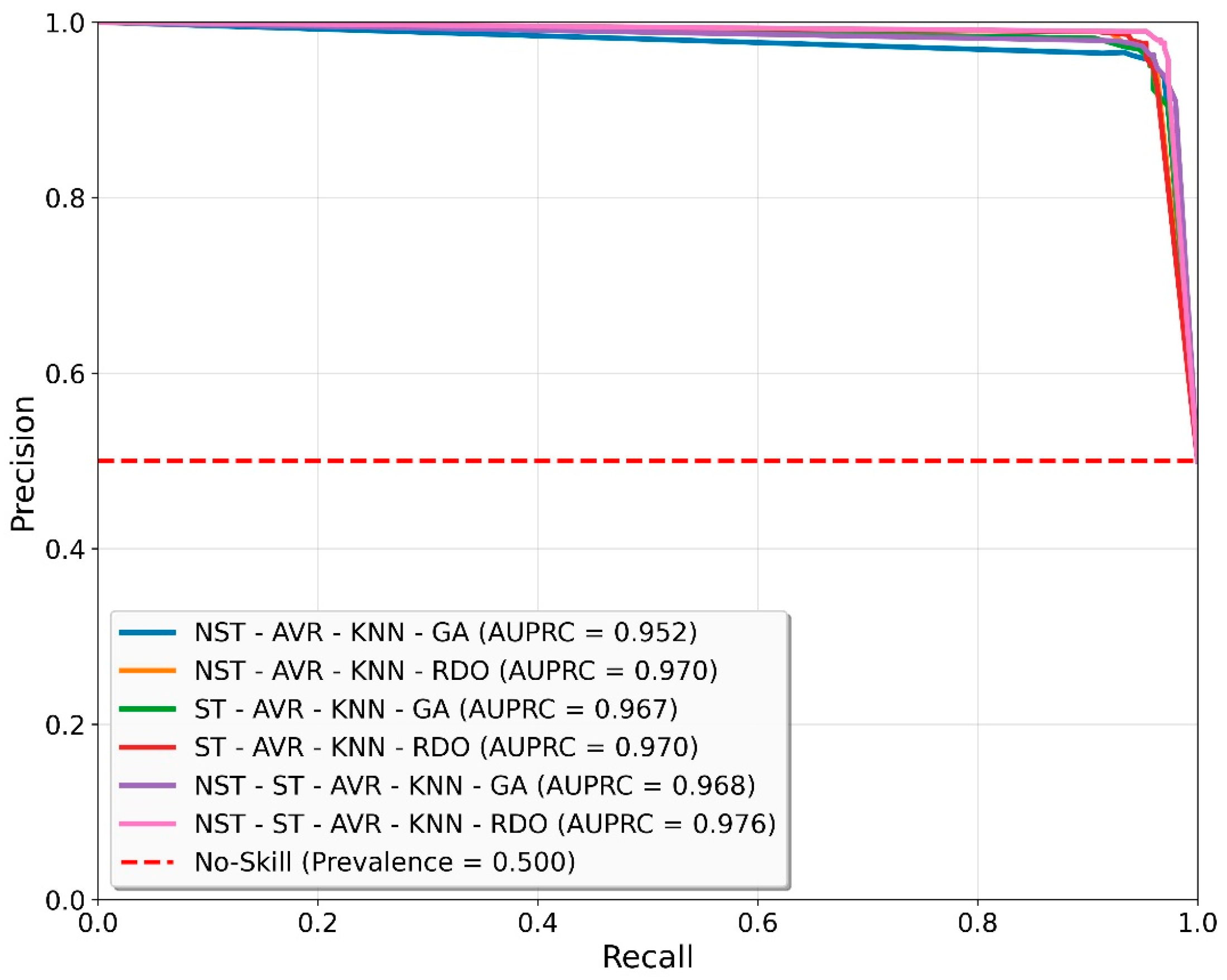

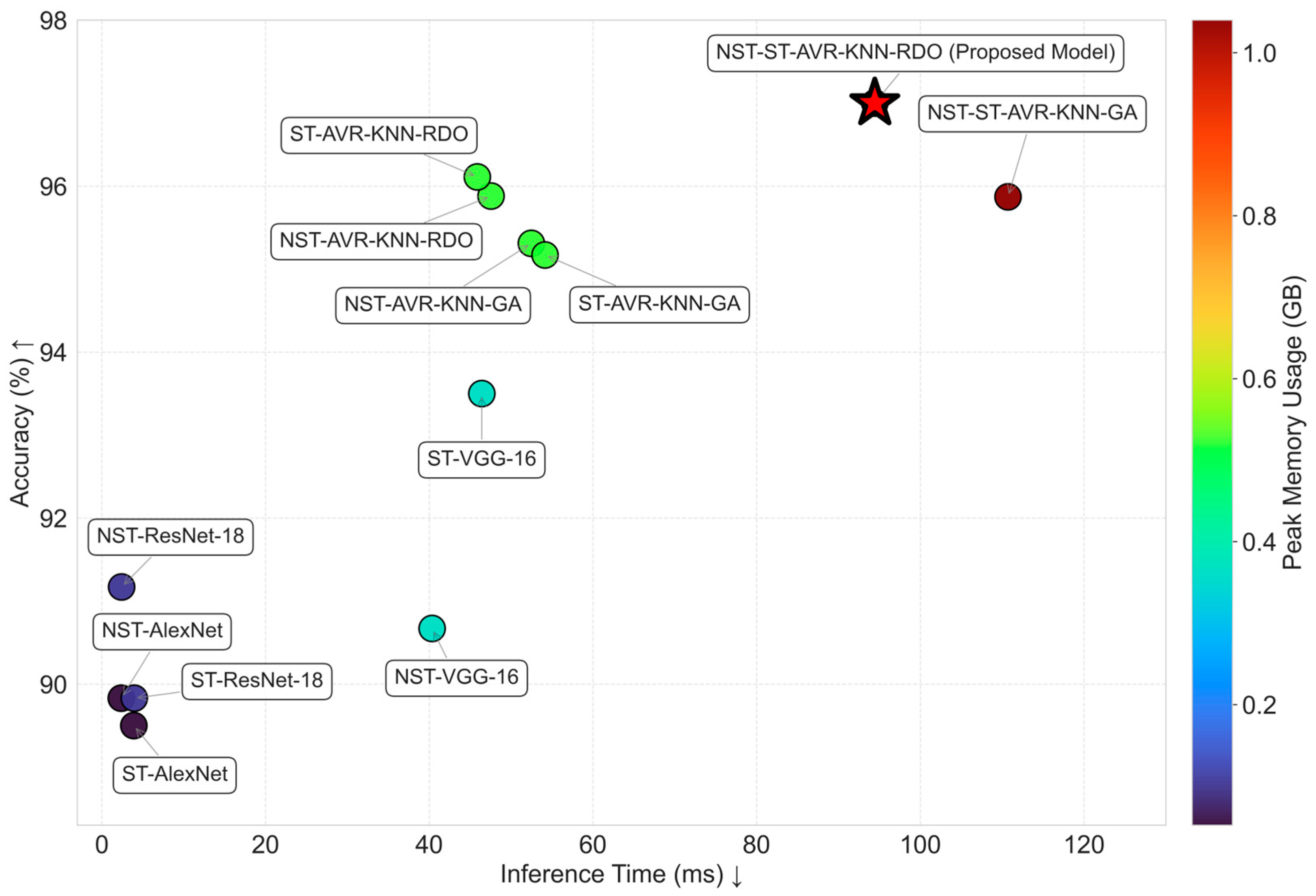

Performances with Optimization Techniques

4. Conclusions and Future Research

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Berry, E.; Dernini, S.; Burlingame, B.; Meybeck, A.; Conforti, P. Food security and sustainability: Can one exist without the other? Public Health Nutr. 2015, 18, 2293–2302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagarajan, S.; Nagarajan, S. Abiotic tolerance and crop improvement. In Abiotic Stress Adaptation in Plants: Physiological, Molecular and Genomic Foundation; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Simsek, M.; Ergun, M.; Ozbay, N. Development of Fruit Sapling Cultivation in Bingöl. In Proceedings of the 3rd Bingöl Symposium, Bingöl, Türkiye, 17–19 September 2010; pp. 261–265. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, L.S.; Oweis, T.; Zairi, A. Irrigation management under water scarcity. Agric. Water Manag. 2002, 57, 175–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.D. Double fertilization. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1992, 140, 357–388. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmanič, S.; Strnad, D.; Kohek, Š.; Benes, B.; Hirst, P.; Žalik, B. An algorithm for automatic dormant tree pruning. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 99, 106931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzidakis, I.; Martinez-Vilela, A.; Nieto, G.C.; Basso, B. Intensive olive orchards on sloping land: Good water and pest management are essential. J. Environ. Manag. 2008, 89, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Agricultural Production Statistics. 2000–2020; FAOSTAT Analytical Brief Series 41; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Rouš, R.; Peller, J.; Polder, G.; Hageraats, S.; Ruigrok, T.; Blok, P.M. Apple scab detection in orchards using deep learning on colour and multispectral images. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.08818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Zhao, M. Research on deep learning in apple leaf disease recognition. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2020, 168, 105146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, J.; Mesarich, C.; Bus, V.; Beresford, R.; Plummer, K.; Templeton, M. Venturia inaequalis: The causal agent of apple scab. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2011, 12, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearson, R. Suppression of Cedar Apple Rust Pycnia on Apple Leaves Following Postinfection Applications of Fenarimol and Triforine. Phytopathology 1978, 68, 1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, N.; Shahid, M.; Naz, F.; And, G. Surveillance and characterization of Botryosphaeria obtusa causing frogeye leaf spot of Apple in District Quetta. Mycopathologia 2020, 16, 111–115. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Rytlewski, D.; Mcmanus, P. Virulence of Botryosphaeria dothidea and Botryosphaeria obtusa on Apple and Management of Stem Cankers with Fungicides. Plant Dis. 2020, 84, 1031–1037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacHardy, W.E.; Gadoury, D.M.; Gessler, C. Parasitic and biological fitness of Venturia inaequalis: Relationship to disease management strategies. Plant Dis. 2001, 85, 1036–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuthbertson, A.G.S.; Murchie, A.K. The impact of fungicides to control apple scab (Venturia inaequalis) on the predatory mite Anystis baccarum and its prey Aculus schlechtendali (apple rust mite) in Northern Ireland Bramley orchards. Crop Prot. 2003, 22, 1125–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moura, L.; Pinto, R.; Rodrigues, R.; Brito, L.; Rego, R.; Valín, M.; Mariz-Ponte, N.; Santos, C.; Mourão, I. Effect of Photo-Selective Nets on Yield, Fruit Quality and Psa Disease Progression in a ‘Hayward’ Kiwifruit Orchard. Horticulturaei 2022, 8, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodors, S.; Lacis, G.; Sokolova, O.; Zhukovs, V.; Apeinans, I.; Bartulsons, T. Apple scab detection using CNN and Transfer Learning. Agron. Res. 2021, 19, 507–519. [Google Scholar]

- Kodors, S.; Lācis, G.; Moročko-Bičevska, I.; Zarembo, I.; Sokolova, O.; Bartulsons, T.; Apeinâns, I.; Žukovs, V. Apple Scab Detection in the Early Stage of Disease Using a Convolutional Neural Network. Proc. Latv. Acad. Sci. 2022, 76, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vishnoi, V.K.; Kumar, K.; Kumar, B.; Mohan, S.; Khan, A.A. Detection of Apple Plant Diseases Using Leaf Images Through Convolutional Neural Network. IEEE Access 2022, 11, 6594–6609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karpyshev, P.; Ilin, V.; Kalinov, I.; Petrovsky, A.; Tsetserukou, D. Autonomous mobile robot for apple plant disease detection based on cnn and multi-spectral vision system. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/SICE International Symposium on System Integration (SII), Iwaki, Japan, 11–14 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey, S.R.; Jalal, A.S. Apple disease classification using color, texture and shape features from images. Signal Image Video Process. 2016, 10, 819–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raman, S.; Chougule, A.; Chamola, V. A low power consumption mobile based IoT framework for real-time classification and segmentation for apple disease. Microprocess. Microsyst. 2022, 94, 104656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H.; Saxena, K.; Jaiswal, A.K. Apple disease classification built on deep learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 3rd International Conference on Intelligent Engineering and Management (ICIEM), London, UK, 27–29 April 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Patidar, A.; Chakravorty, A. Using Machine Learning to Identify Diseases and Perform Sorting in Apple Fruit. Int. J. Innov. Sci. Res. Technol. 2024, 9, 732–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subha, V.; Kasturi, K. Structural Invariant Feature Segmentation Based Apple Fruit Disease Detection Using Deep Spectral Generative Adversarial Networks. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Dyk, D.; Meng, X. The Art of Data Augmentation. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 2001, 10, 1–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shon, H.S.; Batbaatar, E.; Cho, W.S.; Choi, S.G. Unsupervised pre-training of imbalanced data for identification of wafer map defect patterns. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 52352–52363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslej-Krešňáková, V.; El Bouchefry, K.; Butka, P. Morphological classification of compact and extended radio galaxies using convolutional neural networks and data augmentation techniques. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2021, 505, 1464–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Zhan, X.; Wu, R.; Guan, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, W.; Pilanci, M.; Wang, Y.; Luo, Z.; Li, G. Boost AI power: Data augmentation strategies with unlabeled data and conformal prediction, a case in alternative herbal medicine discrimination with electronic nose. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 22995–23005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shorten, C.; Khoshgoftaar, T. A survey on Image Data Augmentation for Deep Learning. J. Big Data 2019, 6, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huang, G.; Song, S.; Pan, X.; Xia, Y.; Wu, C. Regularizing Deep Networks with Semantic Data Augmentation. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 44, 3733–3748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Fang, B.; Qian, J.; Yang, S.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, J. Perspective Transformation Data Augmentation for Object Detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 4935–4943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Lussi, R.; Qu, X.; Huang, F.; Kim, H. Reversible Data Hiding with Automatic Brightness Preserving Contrast Enhancement. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2019, 29, 2271–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortés-Ciriano, I.; Bender, A. Improved Chemical Structure-Activity Modeling Through Data Augmentation. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2015, 55, 2682–2692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Xu, J.; Tan, J.; Li, D.; Zha, W. Deep CNN for removal of salt and pepper noise. IET Image Process. 2019, 13, 1550–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, S.; Ping, W.; Peiyi, J.; Hu, S. Research on data augmentation for image classification based on convolution neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 Chinese Automation Congress (CAC), Jinan, China, 20–22 October 2017; pp. 4165–4170. [Google Scholar]

- Easley, G.; Labate, D.; Lim, W. Sparse directional image representations using the discrete shearlet transform. Appl. Comput. Harmon. Anal. 2008, 25, 25–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.; Labate, D.; Easley, G.; Krim, H. A Shearlet Approach to Edge Analysis and Detection. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2009, 18, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.; Baan, M. Multicomponent microseismic data denoising by 3D shearlet transform. Geophysics 2018, 83, A45–A51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, P.; Labate, D. 3-D Discrete Shearlet Transform and Video Processing. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2012, 21, 2944–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidyasagar, K.; Kumar, R.; Sai, G.; Ruchita, M.; Saikia, M. Signal to Image Conversion and Convolutional Neural Networks for Physiological Signal Processing: A Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 66726–66764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, H.; Lee, J. AdvGuard: Fortifying Deep Neural Networks Against Optimized Adversarial Example Attack. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 5345–5356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoughi, T.; Homayounpour, M.; Deypir, M. Adaptive windows multiple deep residual networks for speech recognition. Expert Syst. Appl. 2020, 139, 112840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, T.; Gandhi, T. Deep convolutional neural networks with transfer learning for automated brain image classification. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2020, 31, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Ge, H.; Li, H.; Sun, Y.; Qian, X. Hierarchical deep convolution neural networks based on transfer learning for transformer rectifier unit fault diagnosis. Measurement 2021, 167, 108257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 25; Curran Associates, Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Simonyan, K.; Zisserman, A. Very deep convolutional networks for large-scale image recognition. arXiv 2014, arXiv:1409.1556. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M.; Tavakkoli-Moghaddam, R. Red deer algorithm (RDA): A new nature-inspired meta-heuristic. Soft Comput. 2020, 24, 14637–14665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juneja, S.; Kaur, K.; Singh, H.; Richa. Bio Inspired Meta Heuristic Approach based on Red Deer in WSN. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Communication and Electronics Systems (ICCES), Coimbatore, India, 22–24 June 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Fathollahi-Fard, A.M.; Niaz Azari, M.; Hajiaghaei-Keshteli, M. An improved red deer algorithm for addressing a direct current brushless motor design problem. Sci. Iran. 2021, 28, 1750–1764. [Google Scholar]

- Ganesh, N.; Jayalakshmi, S.; Narayanan, R.; Mahdal, M.; Zawbaa, H.; Mohamed, A. Gated Deep Reinforcement Learning with Red Deer Optimization for Medical Image Classification. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 58982–58993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goudarzi, P.; Rahmani, A.; Mosleh, M. A mathematical optimization model using red deer algorithm for resource discovery in CloudIoT. Trans. Emerg. Telecommun. Technol. 2022, 33, e4646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Predicted: Positive | Predicted: Negative | |

| Actual: Positive | TP (True Positive) | FN (False Negative) |

| Actual: Negative | FP (False Positive) | TN (True Negative) |

| Data Type | Train Data | Test Data | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy | Scab | Healthy | Scab | ||

| Real Data | 276 | 226 | 69 | 57 | 628 |

| Augmented Data | 924 | 974 | 231 | 243 | 2372 |

| Total | 1200 | 1200 | 300 | 300 | 3000 |

| Type | Models | Signal Processing (Shearlet Transform) | Optimization | All Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Models | NST-AlexNet | No | No | 1000 |

| NST-VGG-16 | No | No | 1000 | |

| NST-ResNet-18 | No | No | 1000 | |

| ST-AlexNet | Yes | No | 1000 | |

| ST-VGG-16 | Yes | No | 1000 | |

| ST-ResNet-18 | Yes | No | 1000 | |

| Hybrid Models | NST-AVR-KNN-GA | No | GA | 3000 |

| NST-AVR-KNN-RDO | No | RDO | 3000 | |

| ST-AVR-KNN-GA | Yes | GA | 3000 | |

| ST-AVR-KNN-RDO | Yes | RDO | 3000 | |

| NST-ST-AVR-KNN-GA | Both | GA | 6000 | |

| NST-ST-AVR-KNN-RDO | Both | RDO | 6000 |

| Models | Input Size | Total Layers | Total Parameters (Original) | Parameters After Modification | Modifications Applied |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlexNet | 224 224 | 8 (5 conv + 3 fc) | 61.10 M | 11.68 M | Last FC layer replaced: 9216 → 1000 → 2 |

| VGG-16 | 224 224 | 16 (13 conv + 3 fc) | 138.30 M | 39.81 M | 25,088 → 1000 → 2 (with ReLU + Dropout) |

| ResNet-18 | 224 224 | 18 (17 conv + 1 fc) | 11.68 M | 11.69 M | 512 → 1000 → 2 (ReLU + Dropout 0.5) |

| Models | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Accuracy | Specificity | C1 | C2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NST-AlexNet | 90.45 | 89.83 | 89.79 | 89.83 | 96.00 | 96.00 | 83.67 |

| NST-VGG-16 | 90.81 | 90.67 | 90.66 | 90.67 | 93.67 | 93.67 | 87.67 |

| NST-ResNet-18 | 91.73 | 91.17 | 91.14 | 91.17 | 97.00 | 97.00 | 85.33 |

| ST-AlexNet | 90.05 | 89.50 | 89.46 | 89.50 | 95.33 | 95.33 | 83.67 |

| ST-VGG-16 | 93.68 | 93.50 | 93.49 | 93.50 | 96.67 | 96.67 | 90.33 |

| ST-ResNet-18 | 90.26 | 89.83 | 89.81 | 89.83 | 95.00 | 95.00 | 84.67 |

| Models | No Shearlet Transform (NST) | Shearlet Transform (ST) | Total Selected Features | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlexNet | VGG-16 | ResNet-18 | AlexNet | VGG-16 | ResNet-18 | ||

| NST-AVR-KNN-GA | 435 | 436 | 413 | - | - | - | 1284 |

| NST-AVR-KNN-RDO | 160 | 156 | 169 | - | - | - | 485 |

| ST-AVR-KNN-GA | - | - | - | 406 | 420 | 395 | 1221 |

| ST-AVR-KNN-RDO | - | - | - | 142 | 152 | 146 | 440 |

| NST-ST-AVR-KNN-GA | 451 | 444 | 419 | 444 | 442 | 416 | 2616 |

| NST-ST-AVR-KNN-RDO | 203 | 243 | 208 | 197 | 205 | 216 | 1272 |

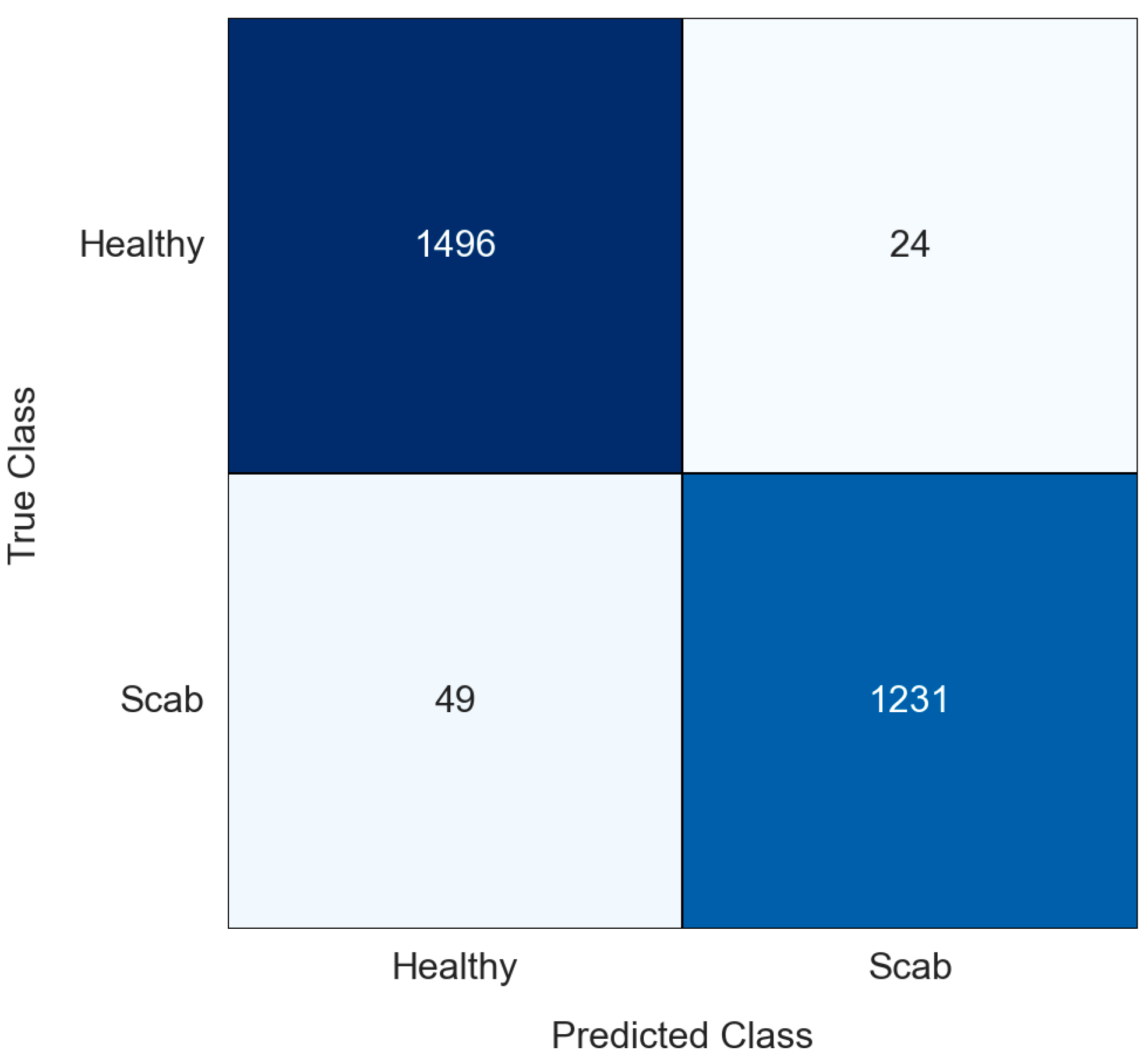

| Hybrid Models | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Specificity | C1 | C2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NST-AVR-KNN-GA | 95.31 ± 0.46 | 94.99 ± 0.60 | 95.67 ± 0.57 | 95.33 ± 0.46 | 94.95 ± 0.63 | 94.95 ± 0.63 | 95.67 ± 0.57 |

| NST-AVR-KNN-RDO | 95.88 ± 0.35 | 96.54 ± 0.45 | 95.18 ± 0.43 | 95.85 ± 0.35 | 96.58 ± 0.46 | 96.58 ± 0.46 | 95.18 ± 0.43 |

| ST-AVR-KNN-GA | 95.17 ± 0.43 | 95.02 ± 0.55 | 95.35 ± 0.53 | 95.18 ± 0.43 | 95.00 ± 0.58 | 95.00 ± 0.58 | 95.35 ± 0.53 |

| ST-AVR-KNN-RDO | 96.11 ± 0.29 | 97.12 ± 0.51 | 95.03 ± 0.28 | 96.07 ± 0.29 | 97.18 ± 0.51 | 97.18 ± 0.51 | 95.03 ± 0.28 |

| NST-ST-AVR-KNN-GA | 95.87 ± 0.19 | 95.90 ± 0.41 | 95.83 ± 0.31 | 95.87 ± 0.18 | 95.90 ± 0.44 | 95.90 ± 0.44 | 95.83 ± 0.31 |

| NST-ST-AVR-KNN-RDO | 97.00 ± 0.31 | 97.40 ± 0.45 | 96.58 ± 0.39 | 96.99 ± 0.31 | 97.42 ± 0.46 | 97.42 ± 0.46 | 96.58 ± 0.39 |

| Models | Memory (MB) | Inference Time (s) | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| NST-AlexNet | 53.4 | 0.00238 | 89.83 |

| NST-VGG-16 | 371.03 | 0.04036 | 90.67 |

| NST-ResNet-18 | 107.98 | 0.00242 | 91.17 |

| ST-AlexNet | 53.4 | 0.00391 | 89.50 |

| ST-VGG-16 | 371.03 | 0.04643 | 93.50 |

| ST-ResNet-18 | 107.98 | 0.00396 | 89.83 |

| NST-AVR-KNN-GA | 532.41 | 0.05248 | 95.31 |

| NST-AVR-KNN-RDO | 532.41 | 0.04756 | 95.88 |

| ST-AVR-KNN-GA | 532.41 | 0.05415 | 95.17 |

| ST-AVR-KNN-RDO | 532.41 | 0.04588 | 96.11 |

| NST-ST-AVR-KNN-GA | 1064.82 | 0.11072 | 95.87 |

| NST-ST-AVR-KNN-RDO | 1064.82 | 0.09444 | 97.00 |

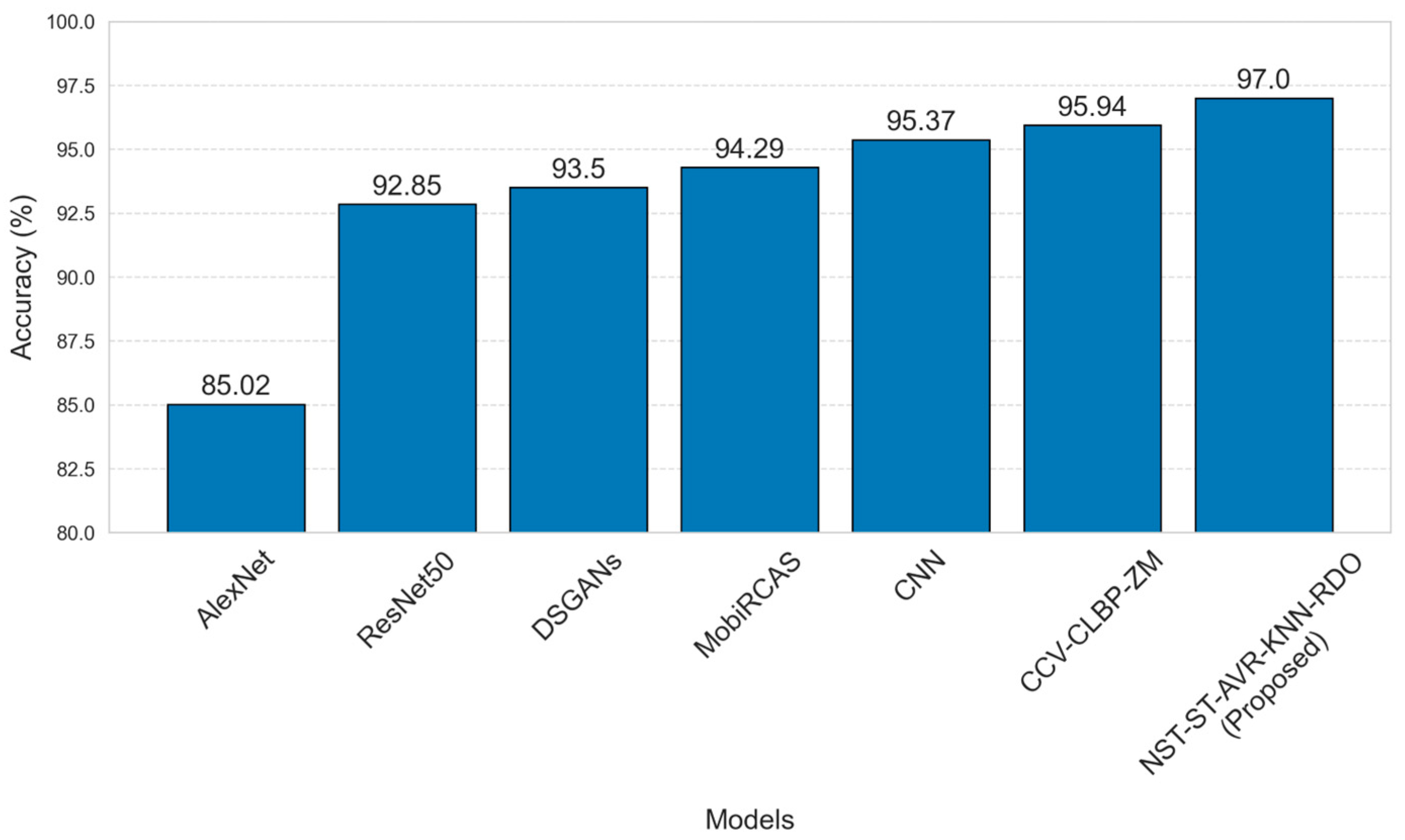

| Studies | Year | Methods | Normal | Scab | Others | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [18] | 2021 | AlexNet | - | - | - | 85.02 |

| [22] | 2016 | CCV-CLBP-ZM | 100.00 | 93.75 | 95.00 | 95.94 |

| [23] | 2022 | MobiRCAS | - | - | - | 94.29 |

| [24] | 2022 | ResNet50 | 95.23 | 80.95 | 97.61 | 92.85 |

| [25] | 2024 | CNN | 88.23 | 80.00 | - | 95.37 |

| [26] | 2024 | DSGANs | - | - | - | 93.50 |

| Proposed Model | NST-ST-AVR-KNN-RDO | 97.42 | 96.58 | - | 97.00 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Karasu, S. Apple Scab Classification Using 2D Shearlet Transform with Integrated Red Deer Optimization Technique in Convolutional Neural Network Models. Electronics 2025, 14, 4678. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234678

Karasu S. Apple Scab Classification Using 2D Shearlet Transform with Integrated Red Deer Optimization Technique in Convolutional Neural Network Models. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4678. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234678

Chicago/Turabian StyleKarasu, Seçkin. 2025. "Apple Scab Classification Using 2D Shearlet Transform with Integrated Red Deer Optimization Technique in Convolutional Neural Network Models" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4678. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234678

APA StyleKarasu, S. (2025). Apple Scab Classification Using 2D Shearlet Transform with Integrated Red Deer Optimization Technique in Convolutional Neural Network Models. Electronics, 14(23), 4678. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234678