A Novel Strategy for Preventing Commutation Failures During Fault Recovery Using PLL Phase Angle Error Compensation

Abstract

1. Introduction

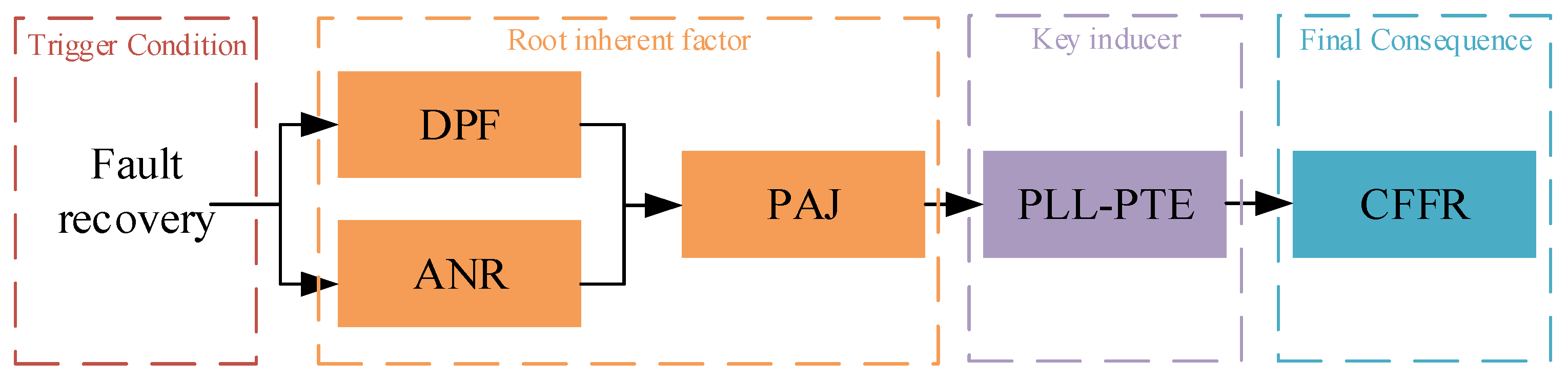

2. Investigation of the Leading Influence of PLL-PTE on CFFR

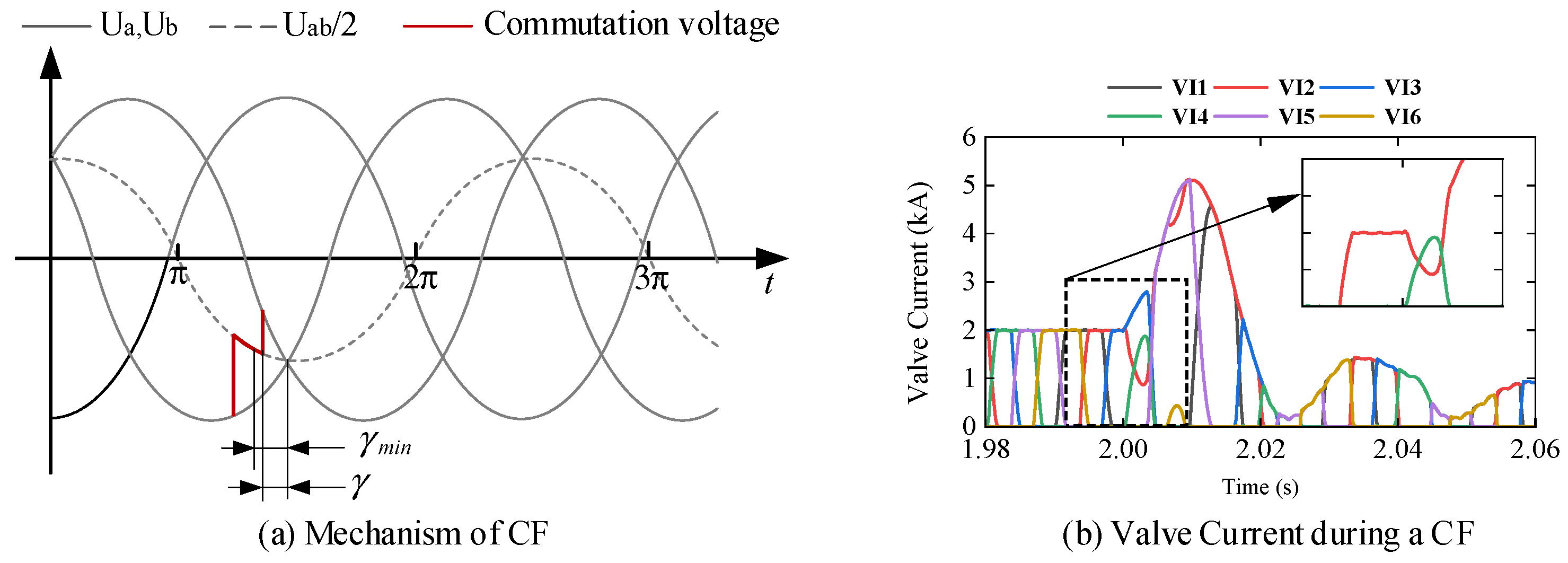

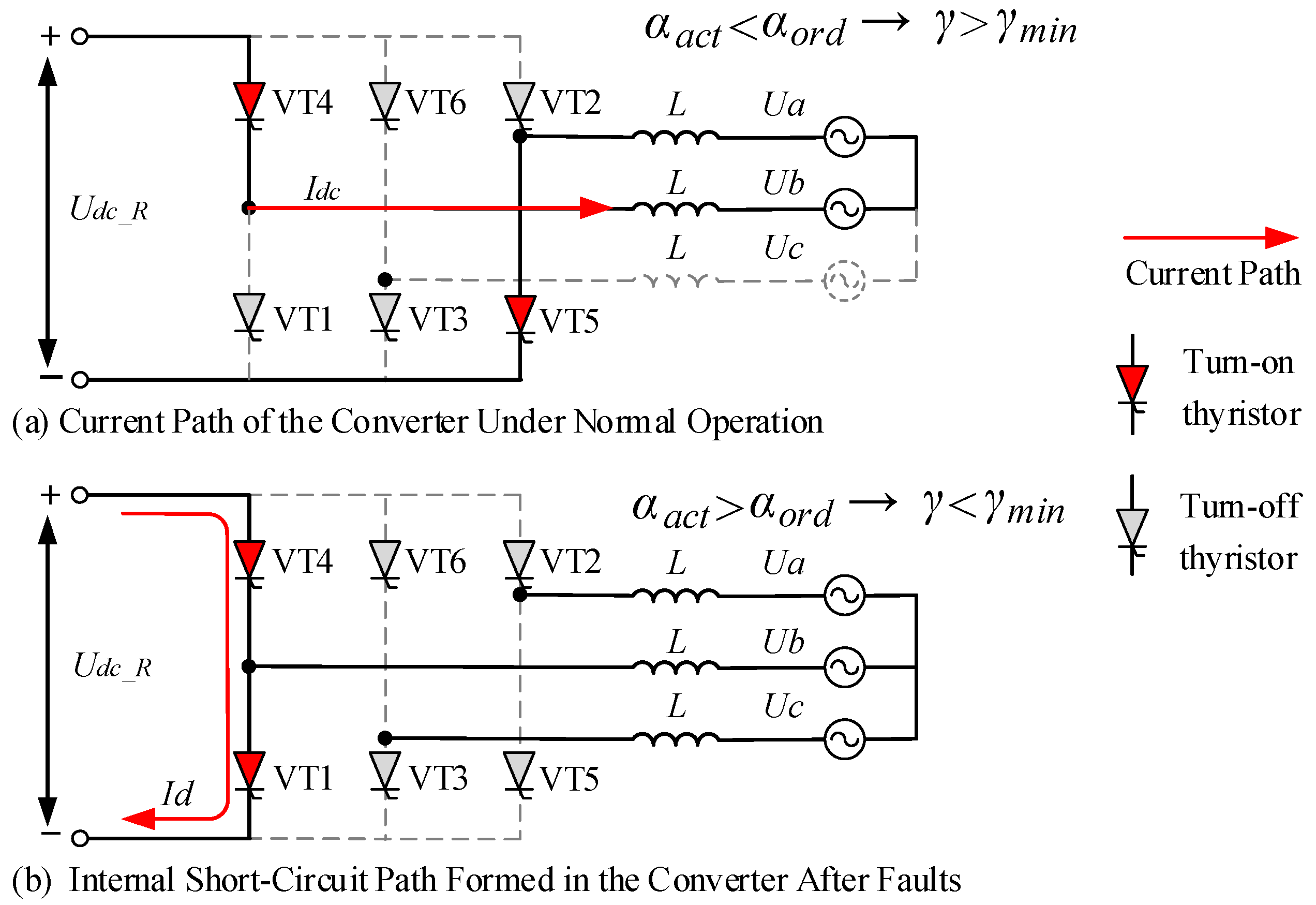

2.1. Mechanism of CF in LCC-HVDC Systems

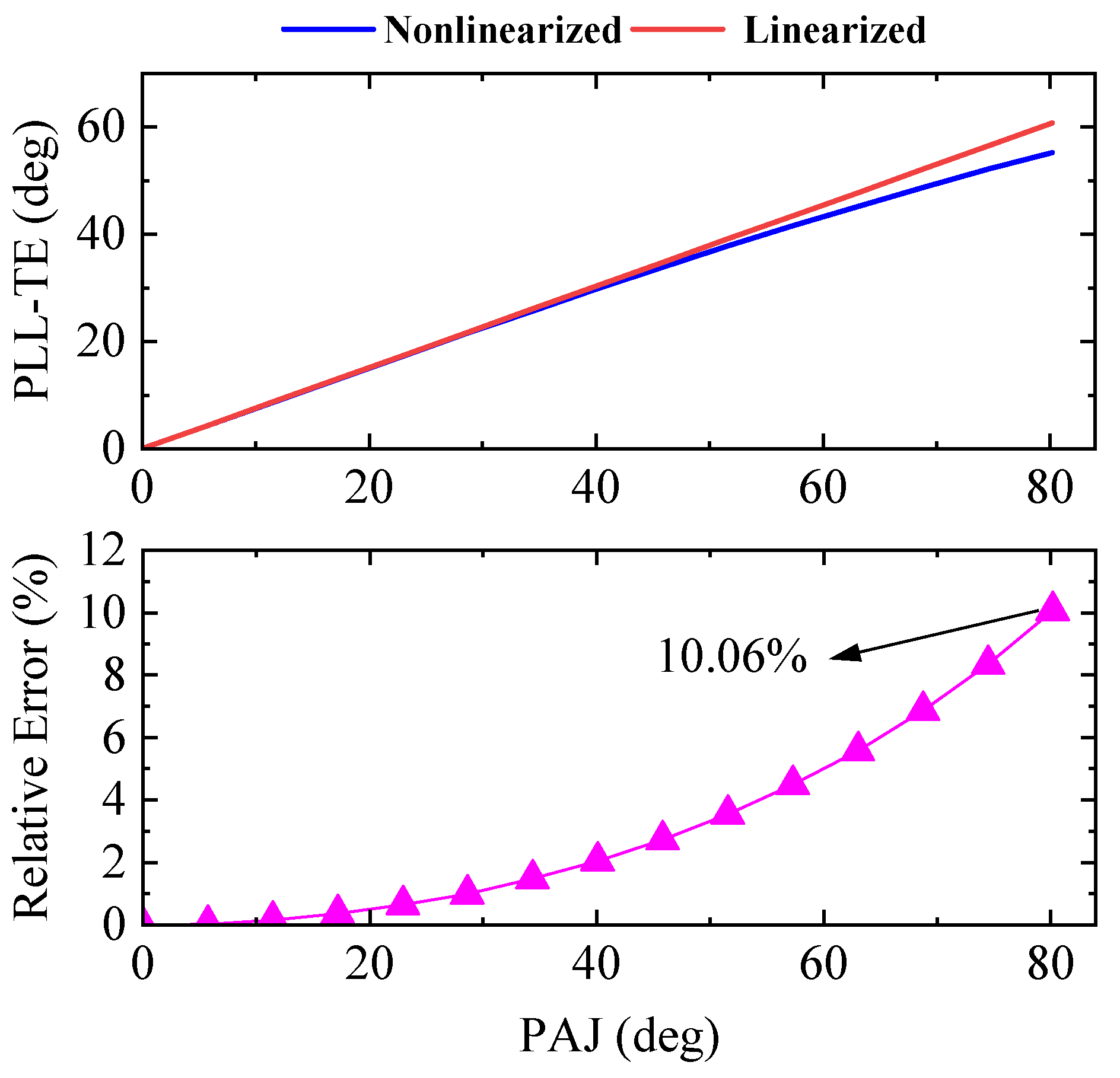

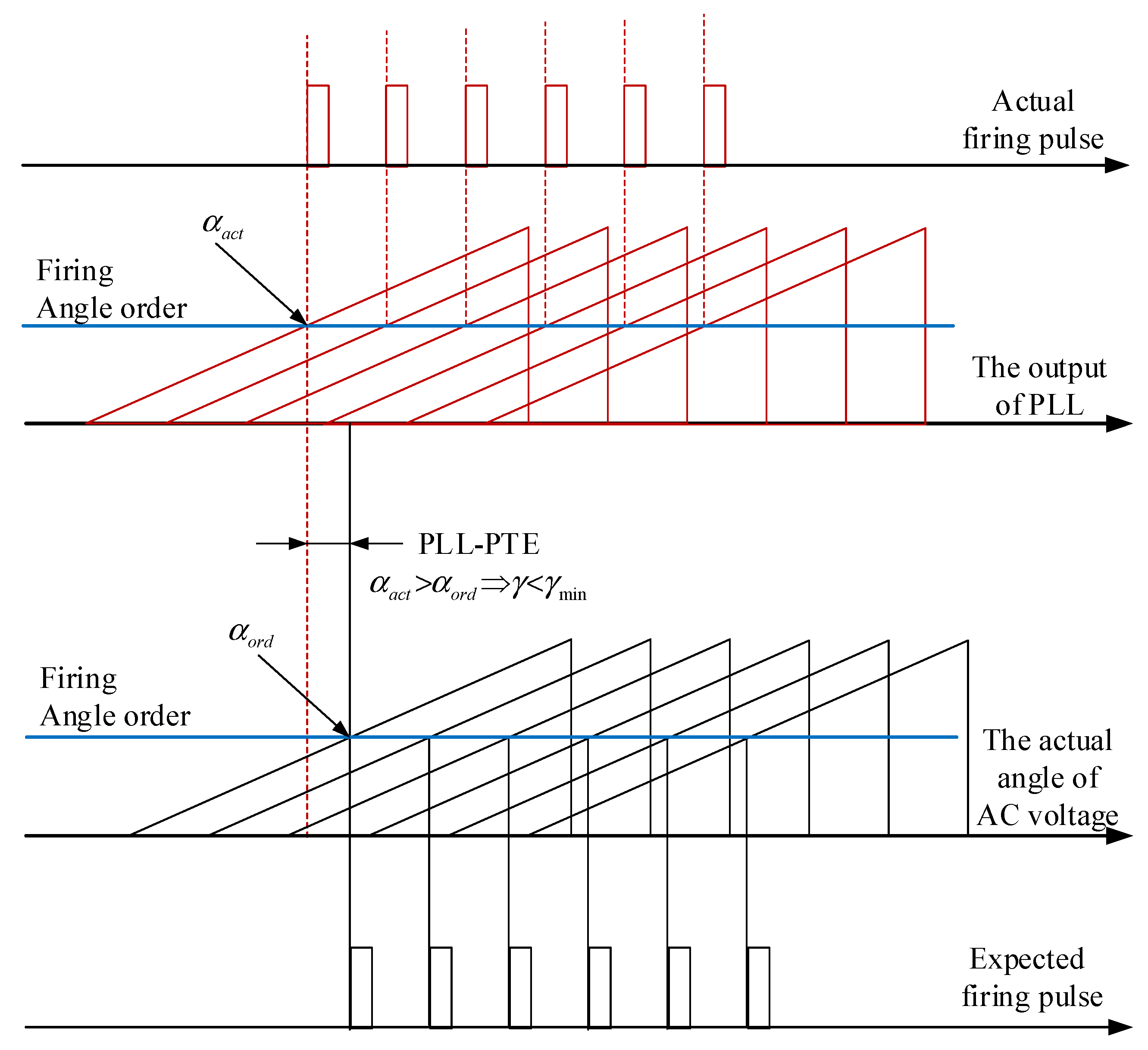

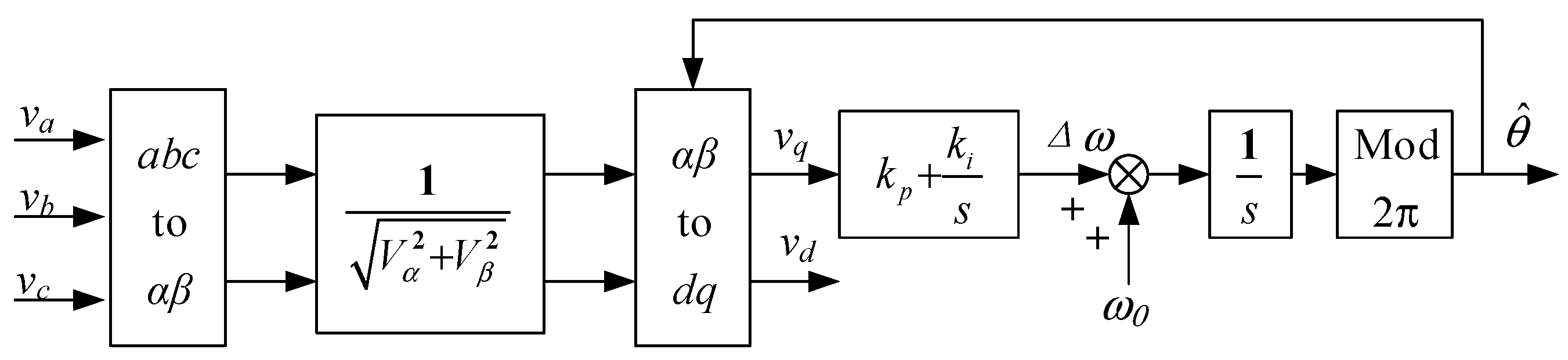

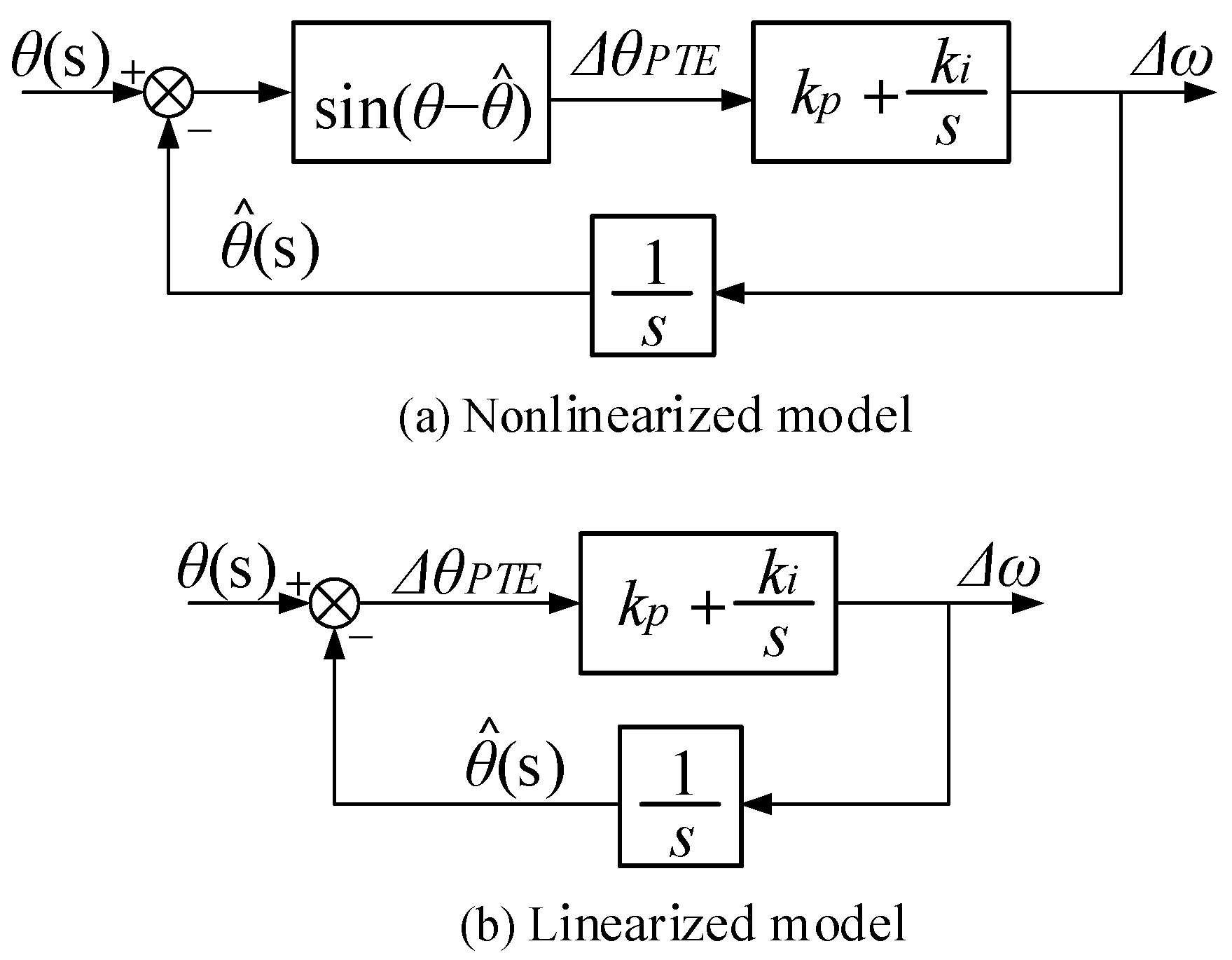

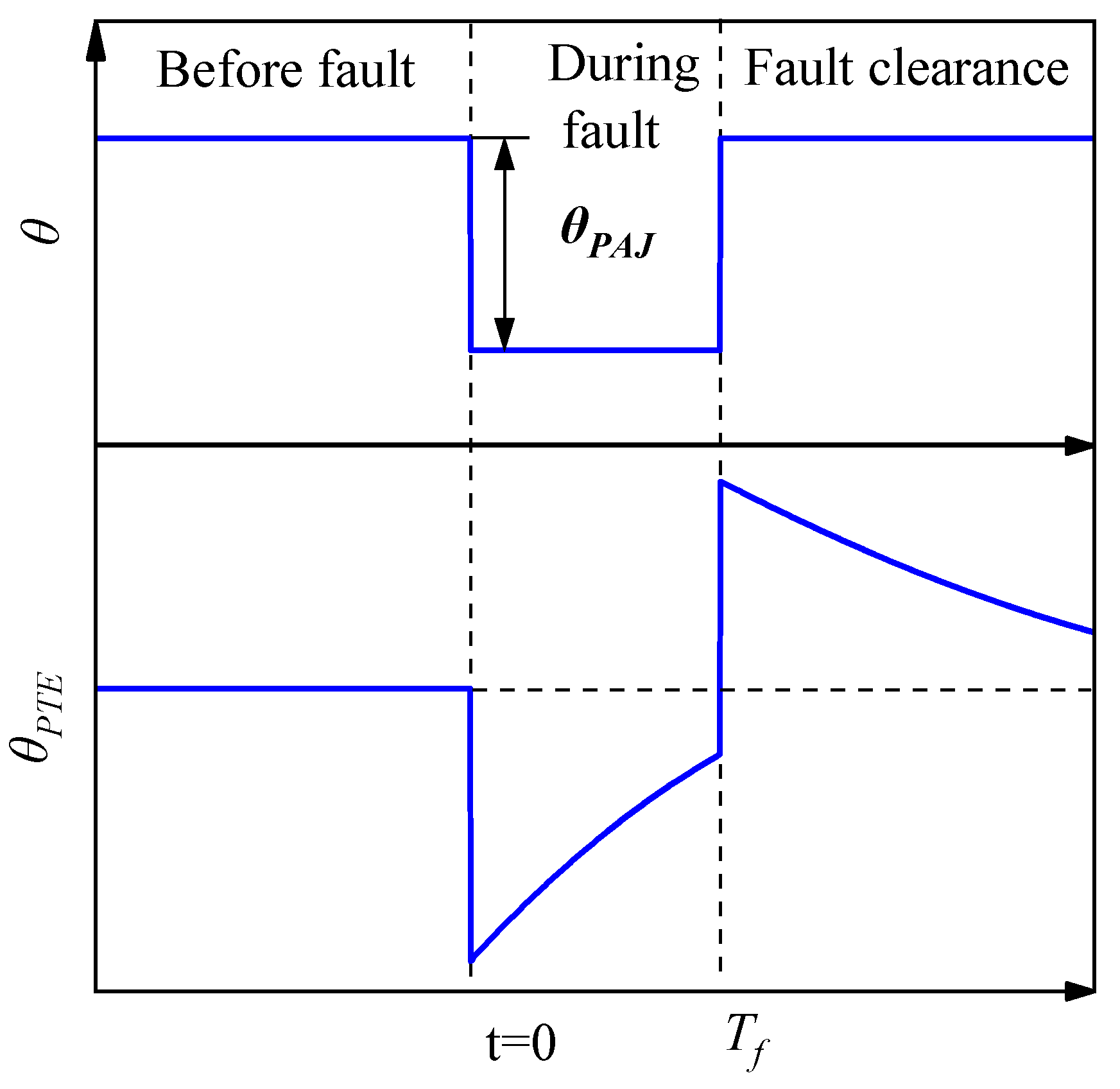

2.2. Mechanism of PLL-PTE Induced by PAJ

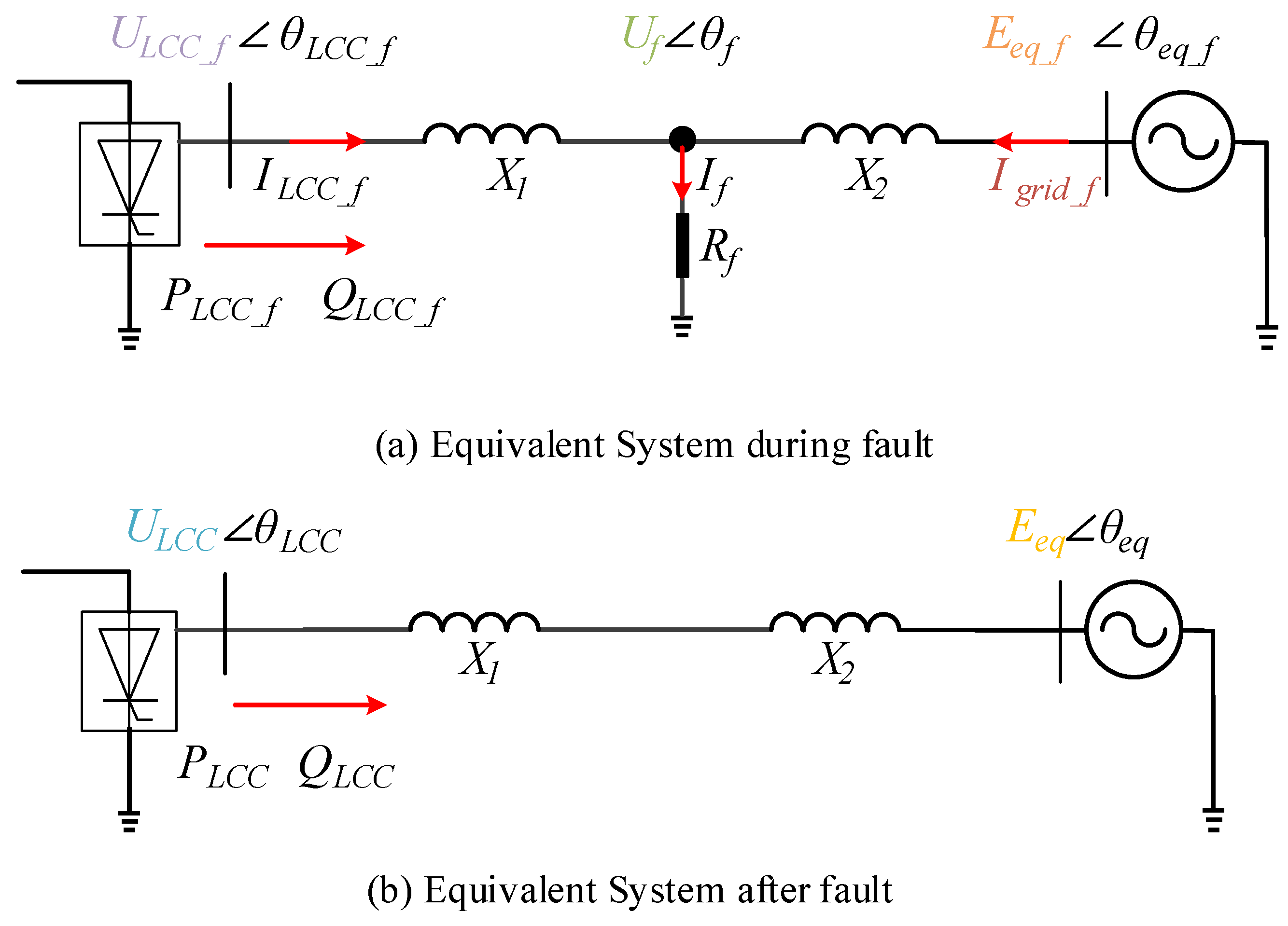

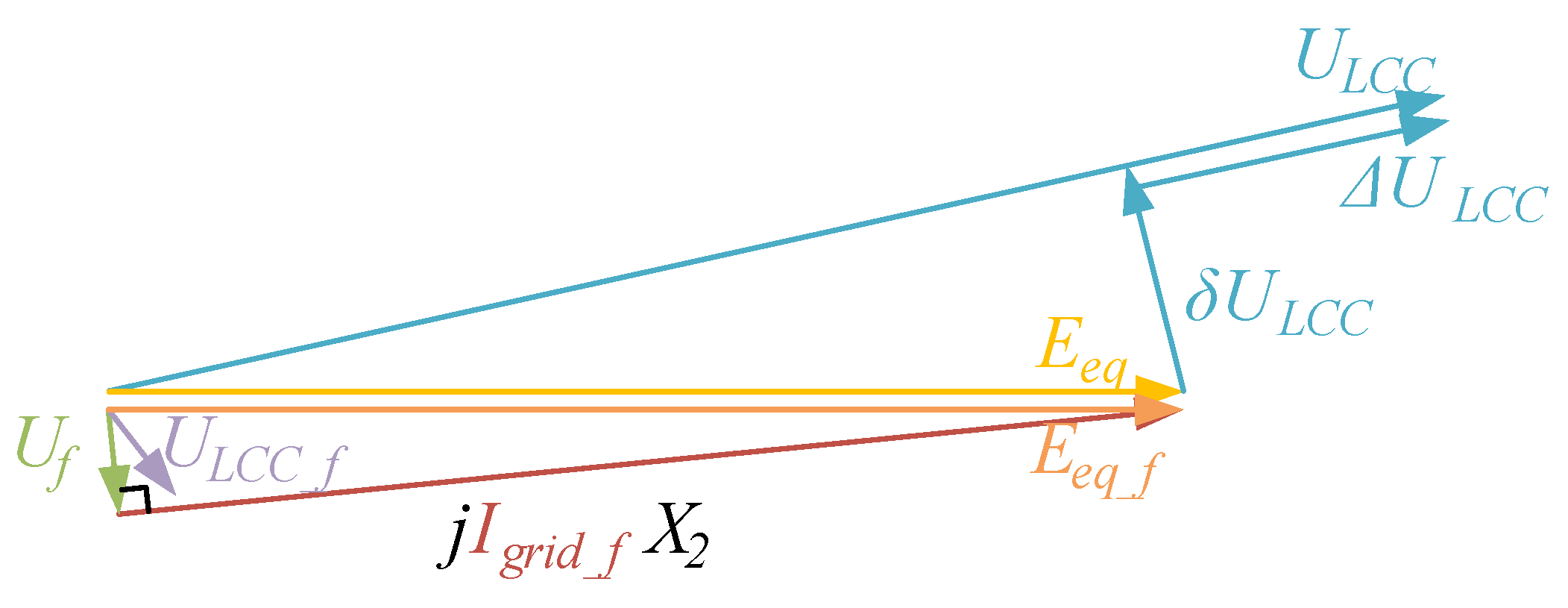

2.3. Mechanism of PAJ After AC Fault Clearance

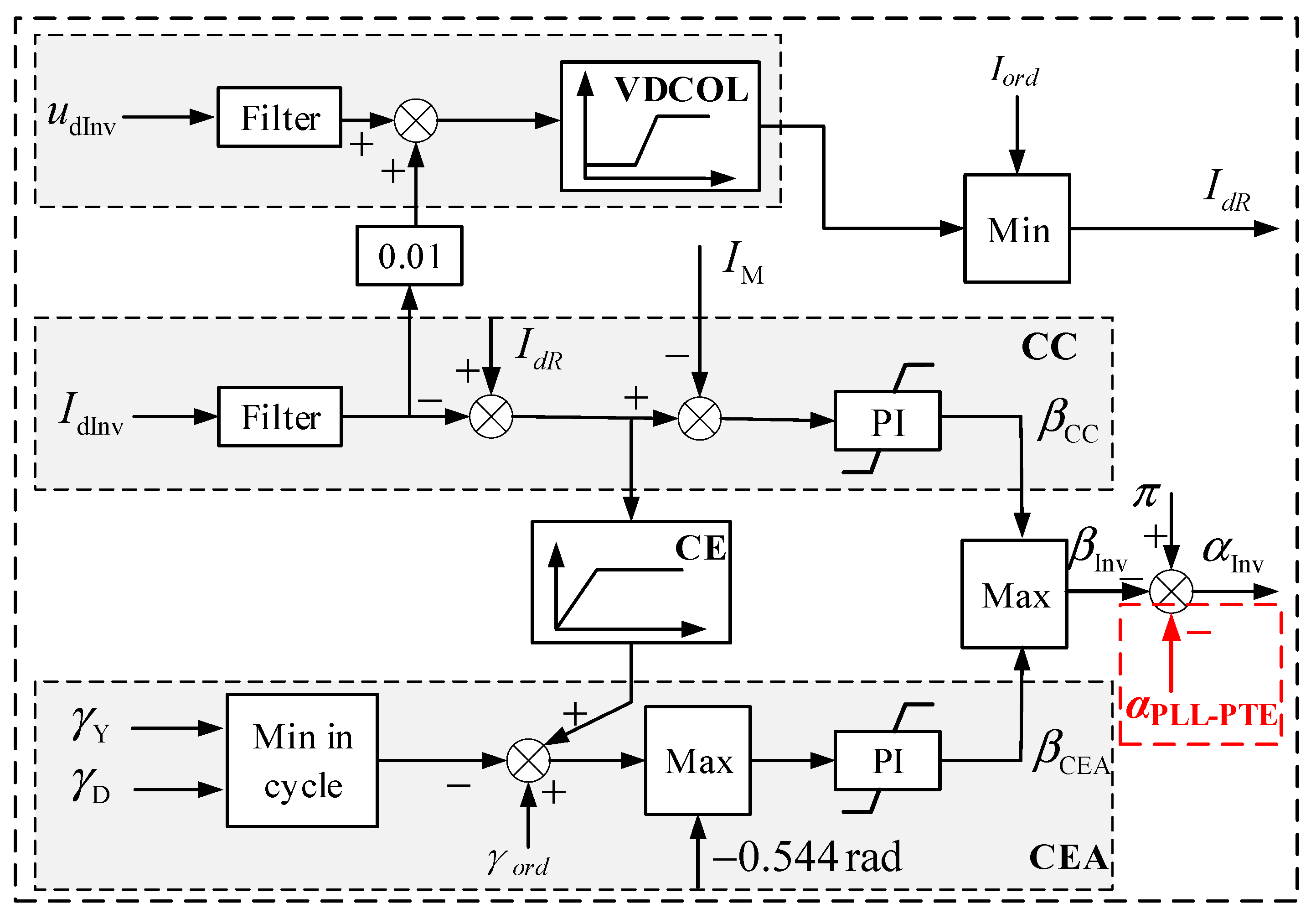

3. Proposed Strategy for Preventing CFFR

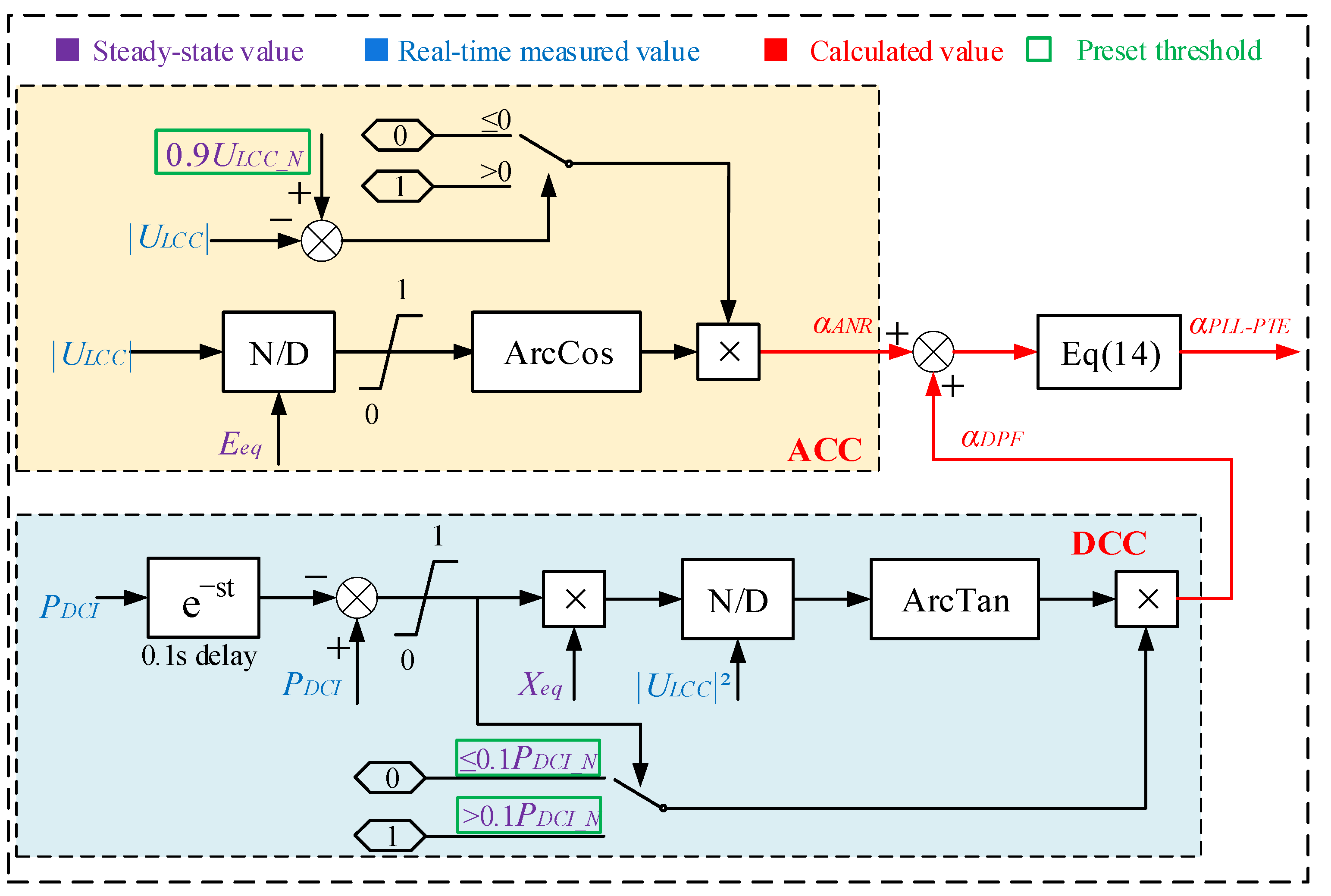

3.1. Overall Control Strategy and Its Advantages

3.2. ANR Compensation Controller (ACC)

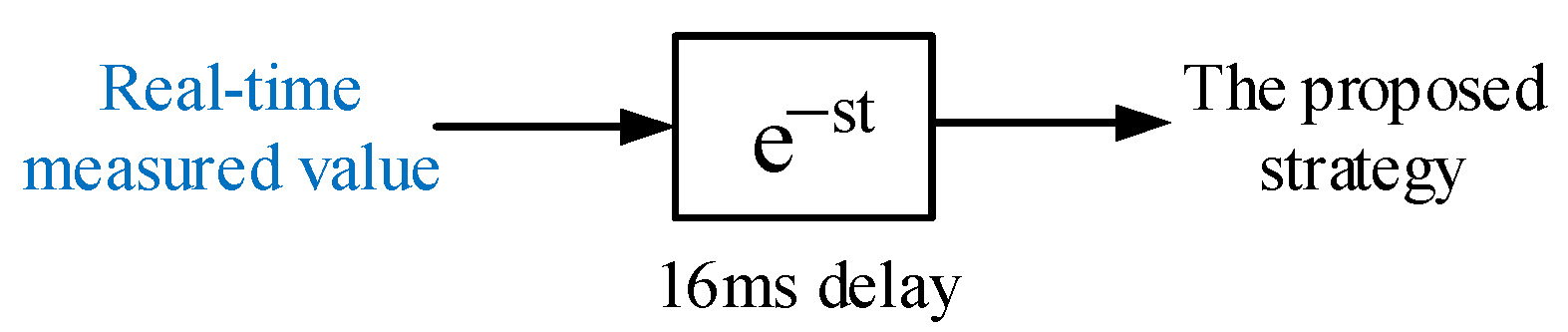

3.3. DPF Compensation Controller (DCC)

4. Case Studies and Validation

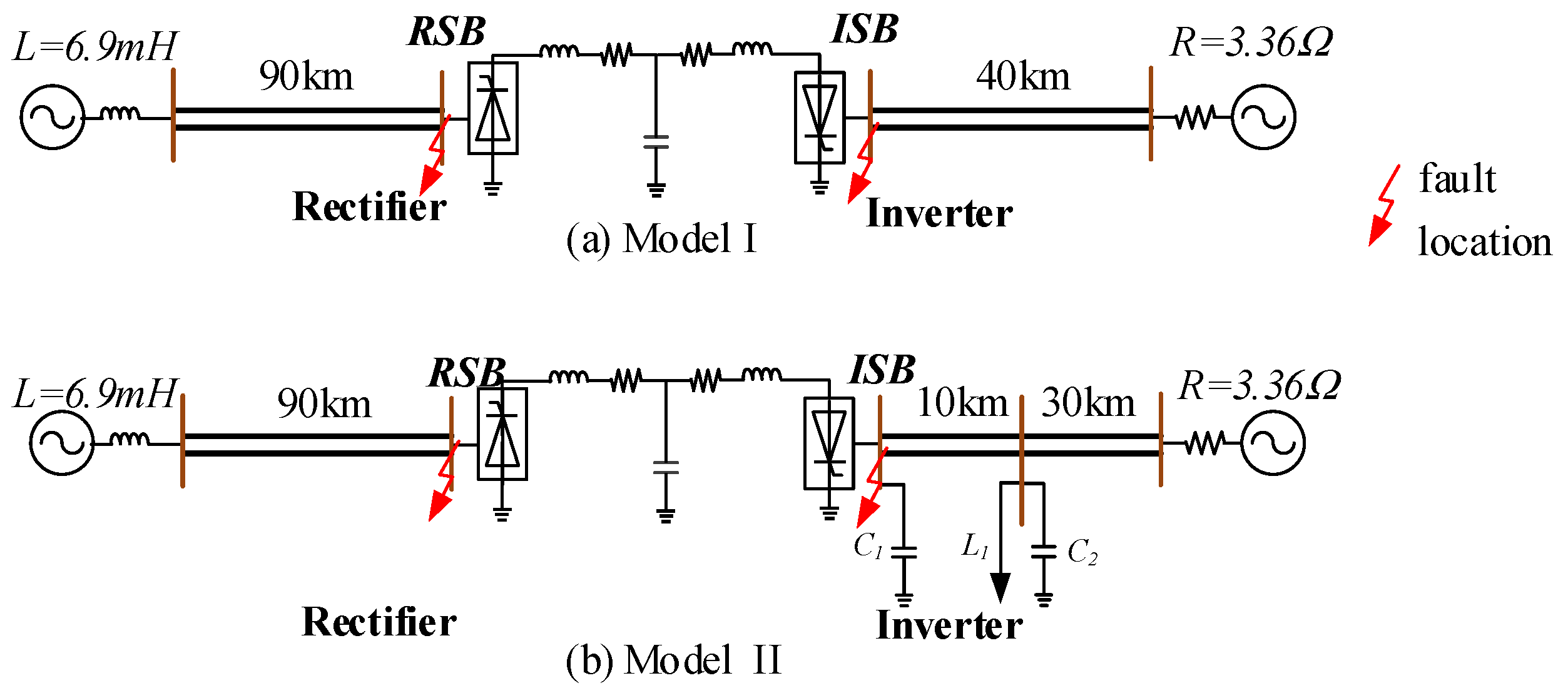

4.1. Test System

4.2. Validation of the Critical Role of PLL-PTE

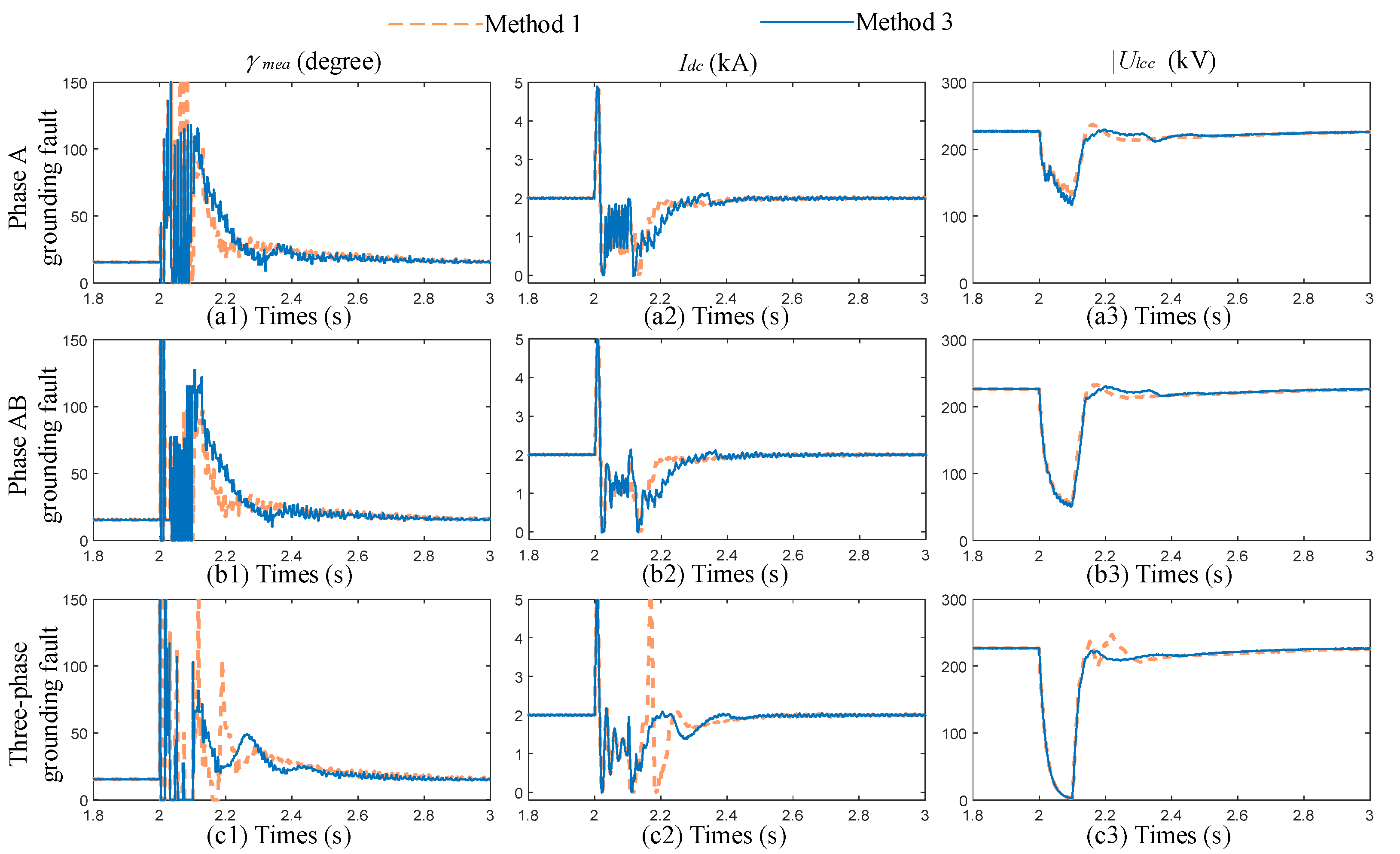

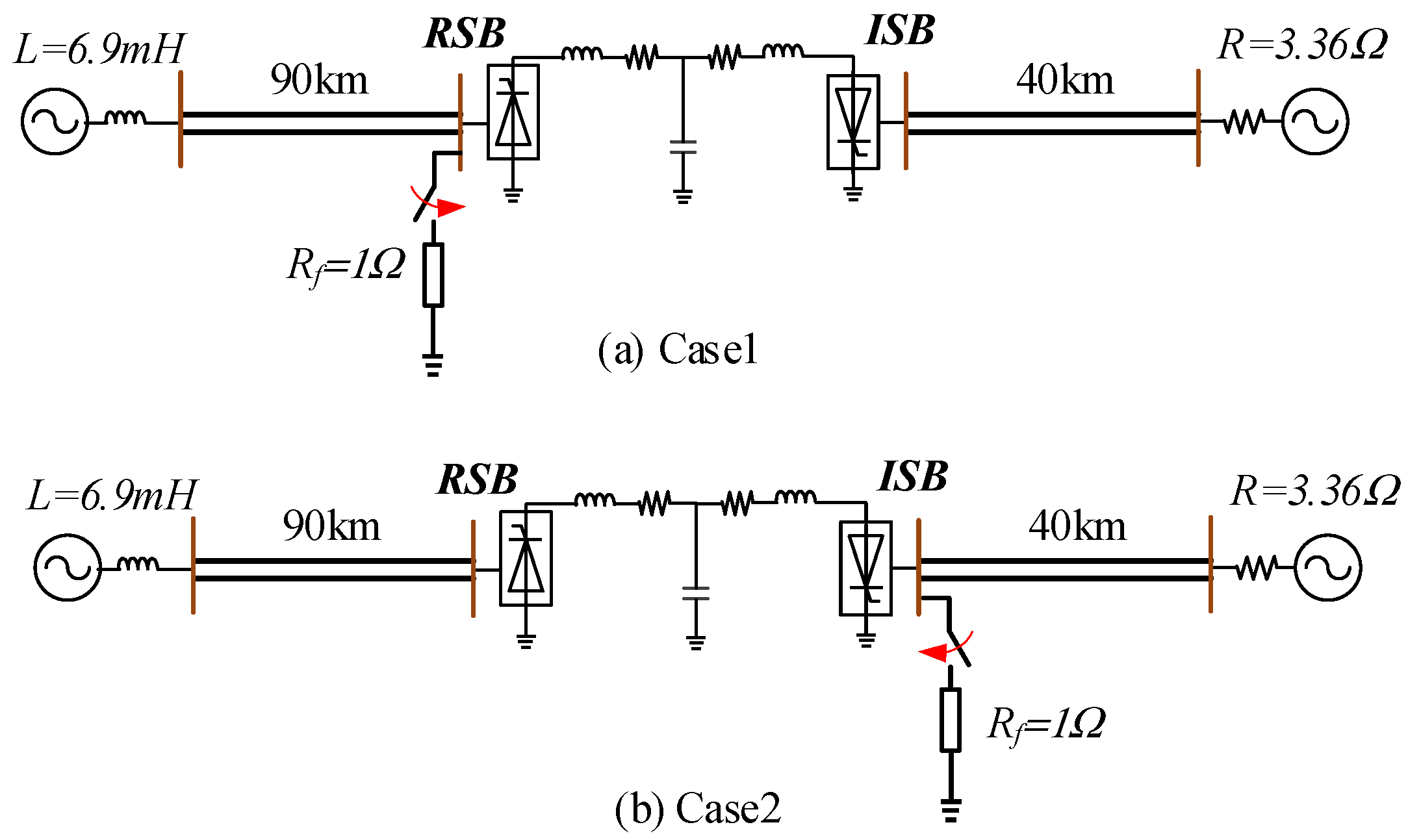

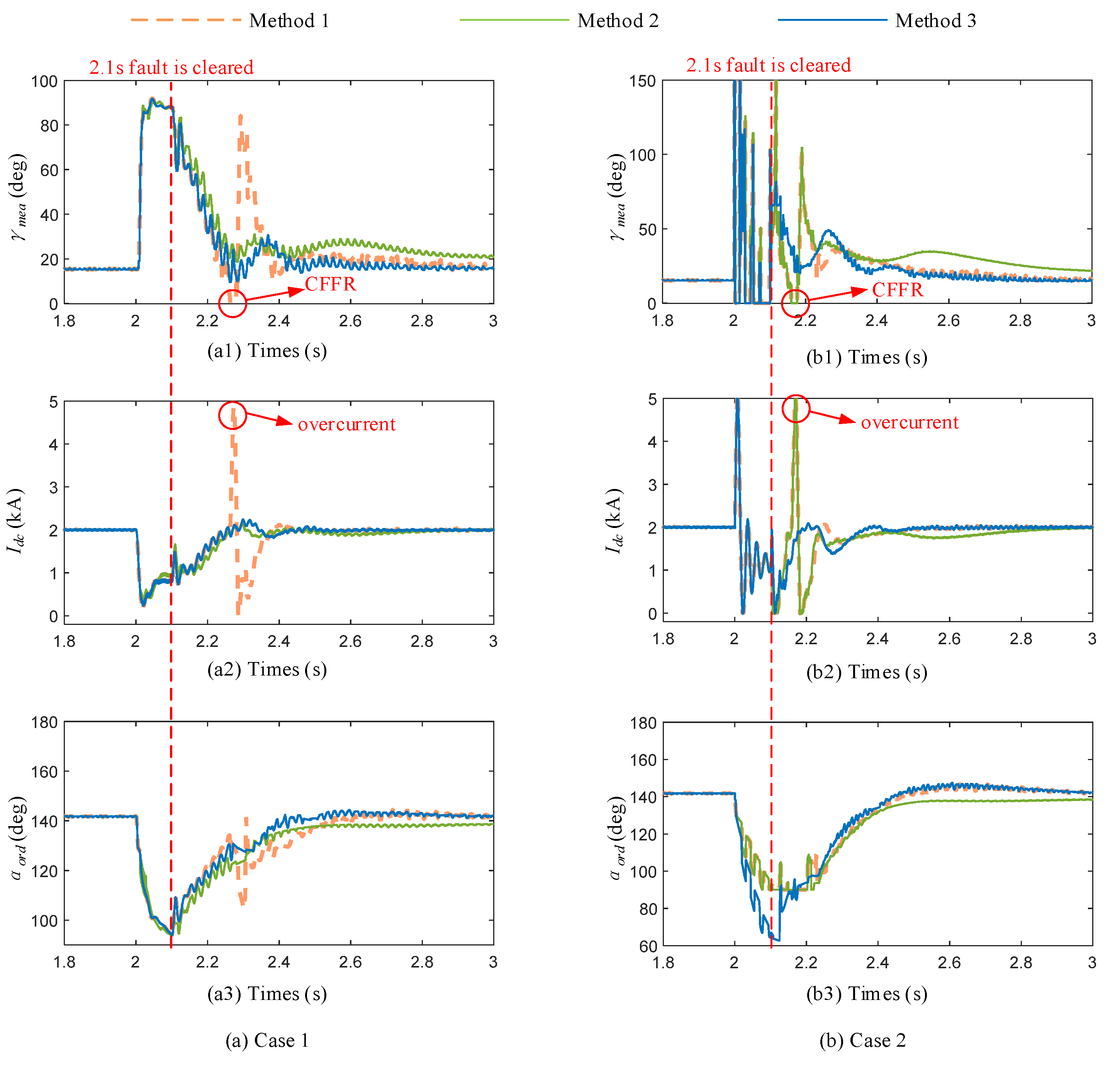

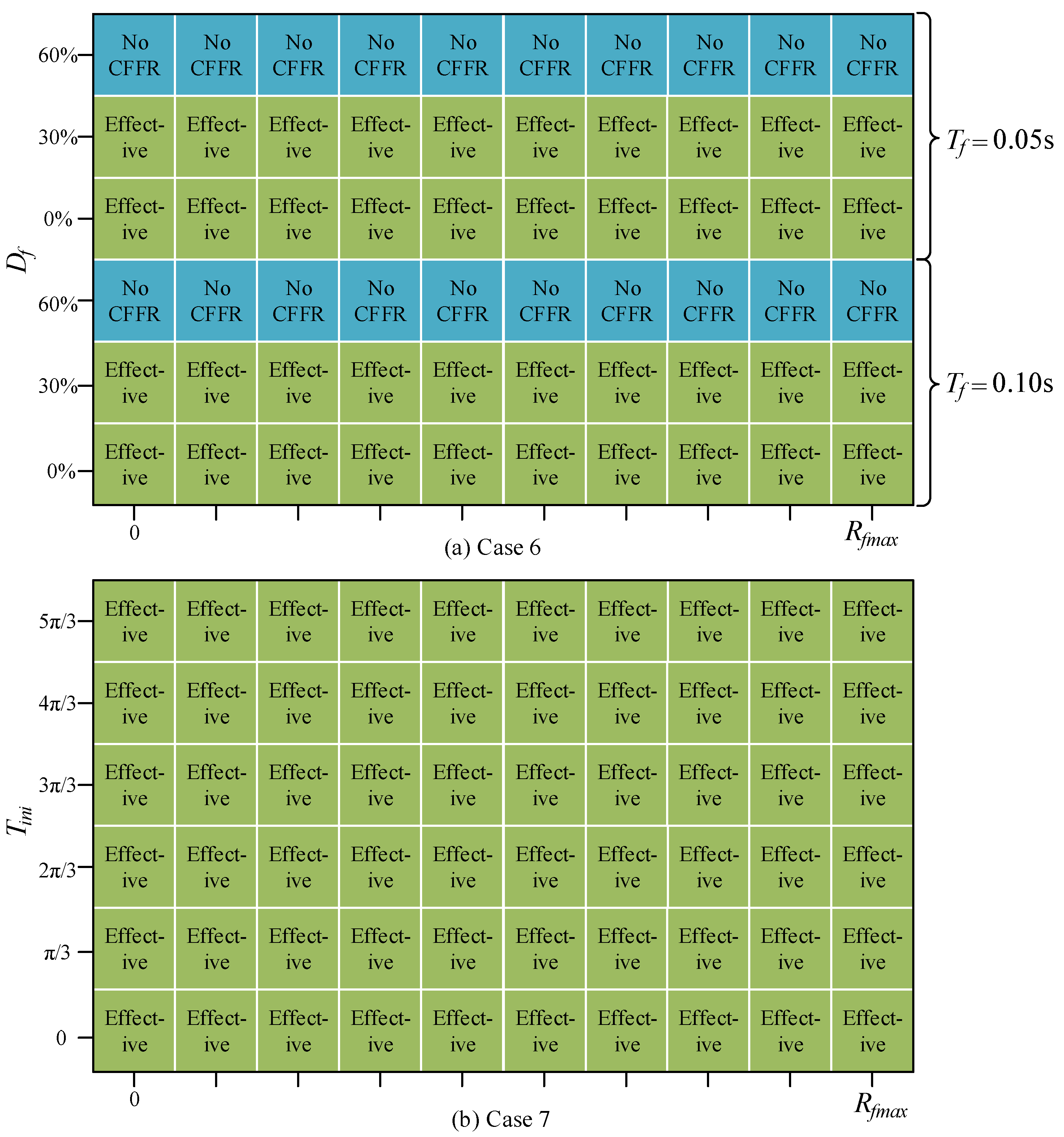

4.3. Validation of the Proposed Controller’s Effectiveness Under Varying Fault Type

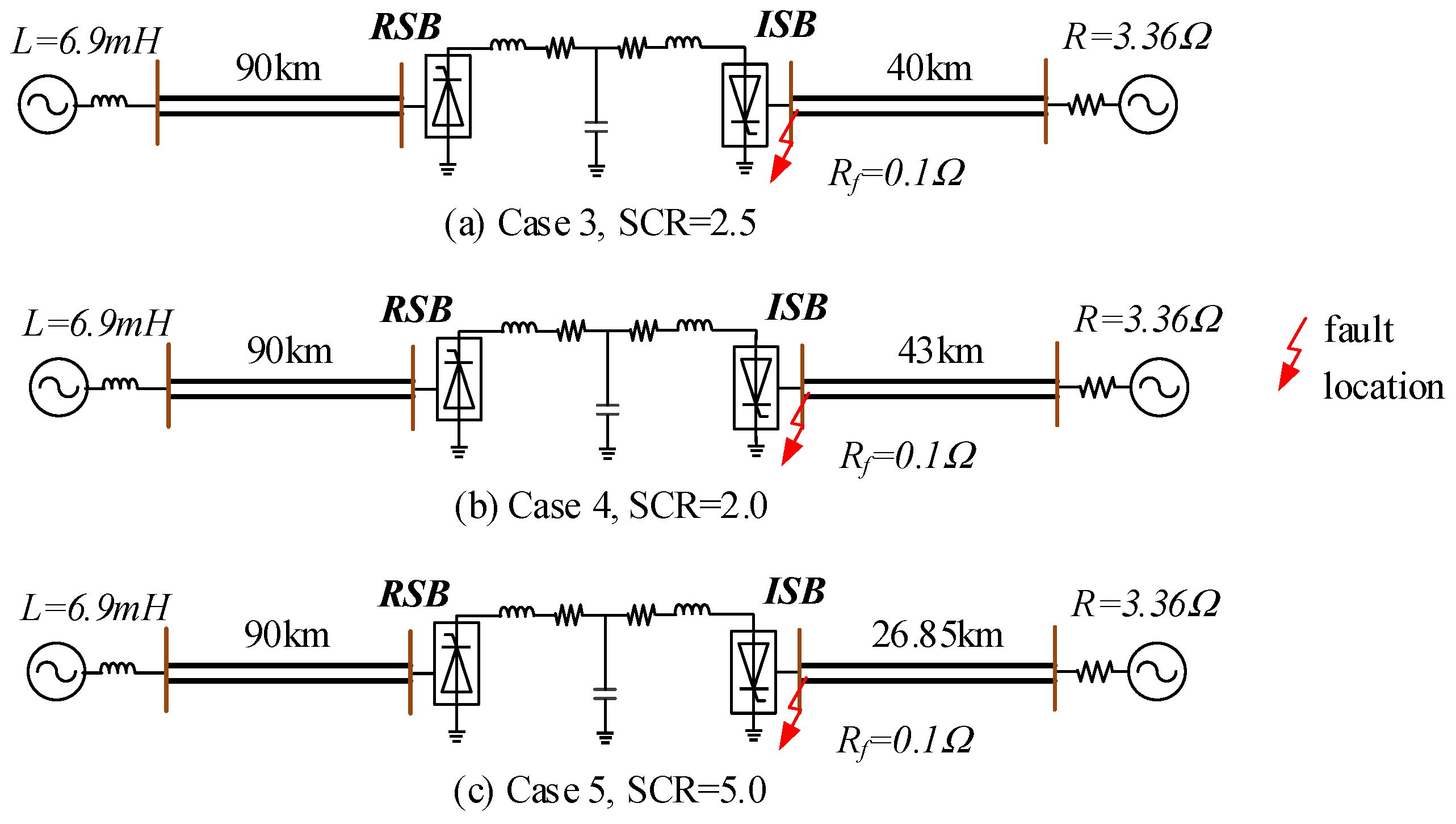

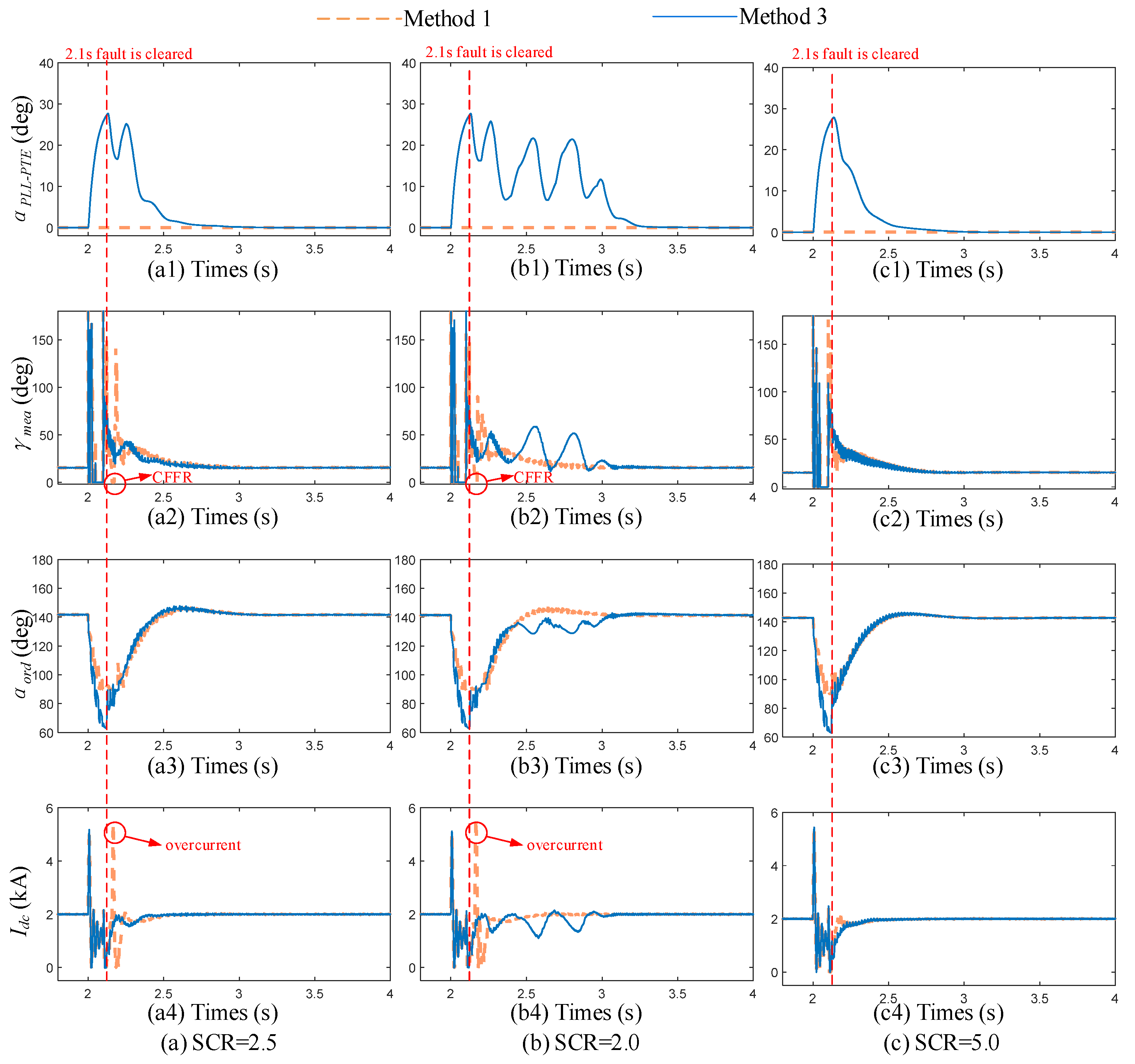

4.4. Validation of the Proposed Controller’s Effectiveness Under Varying System Strengths

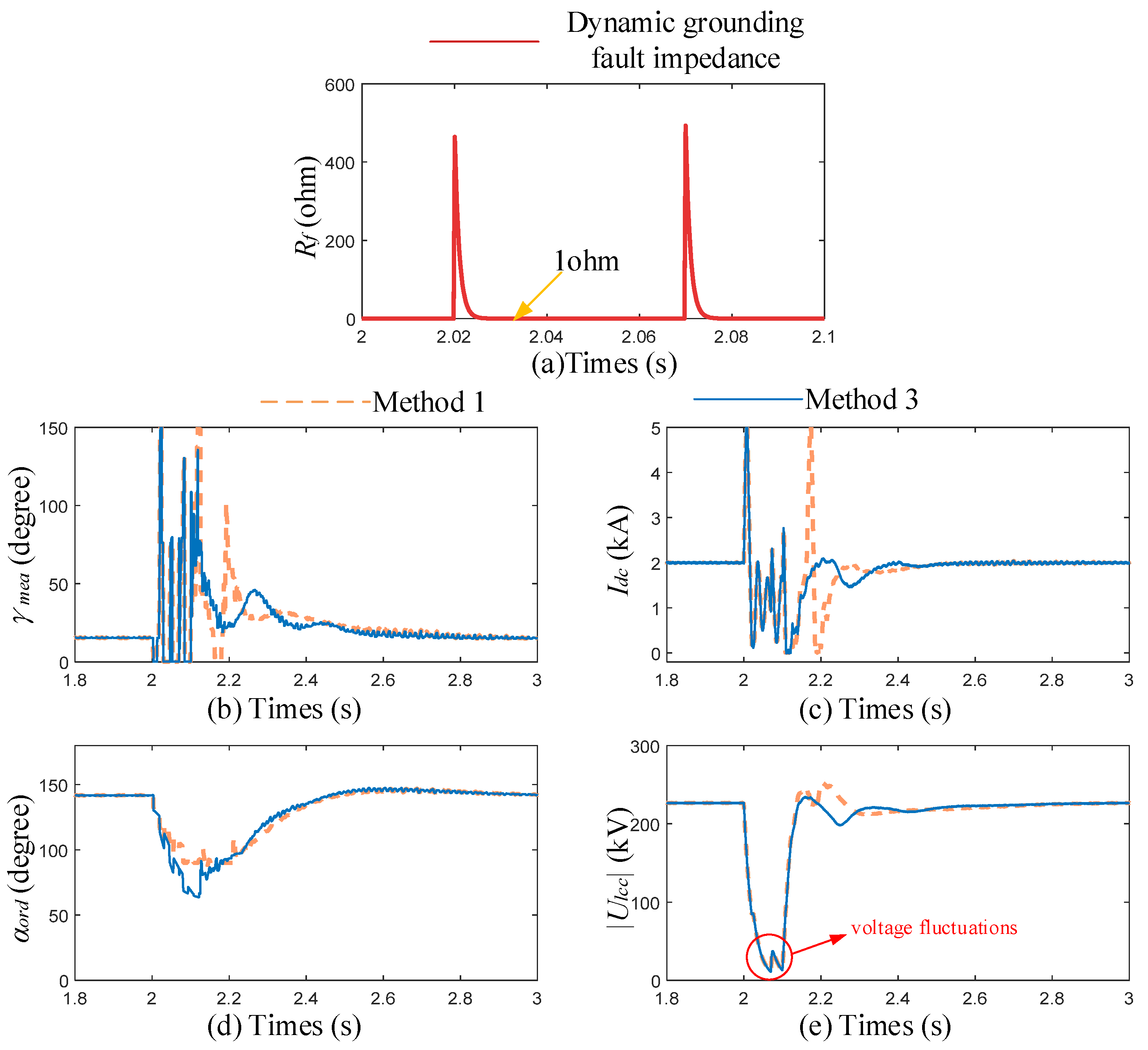

4.5. Applicability Verification of the Proposed Controller

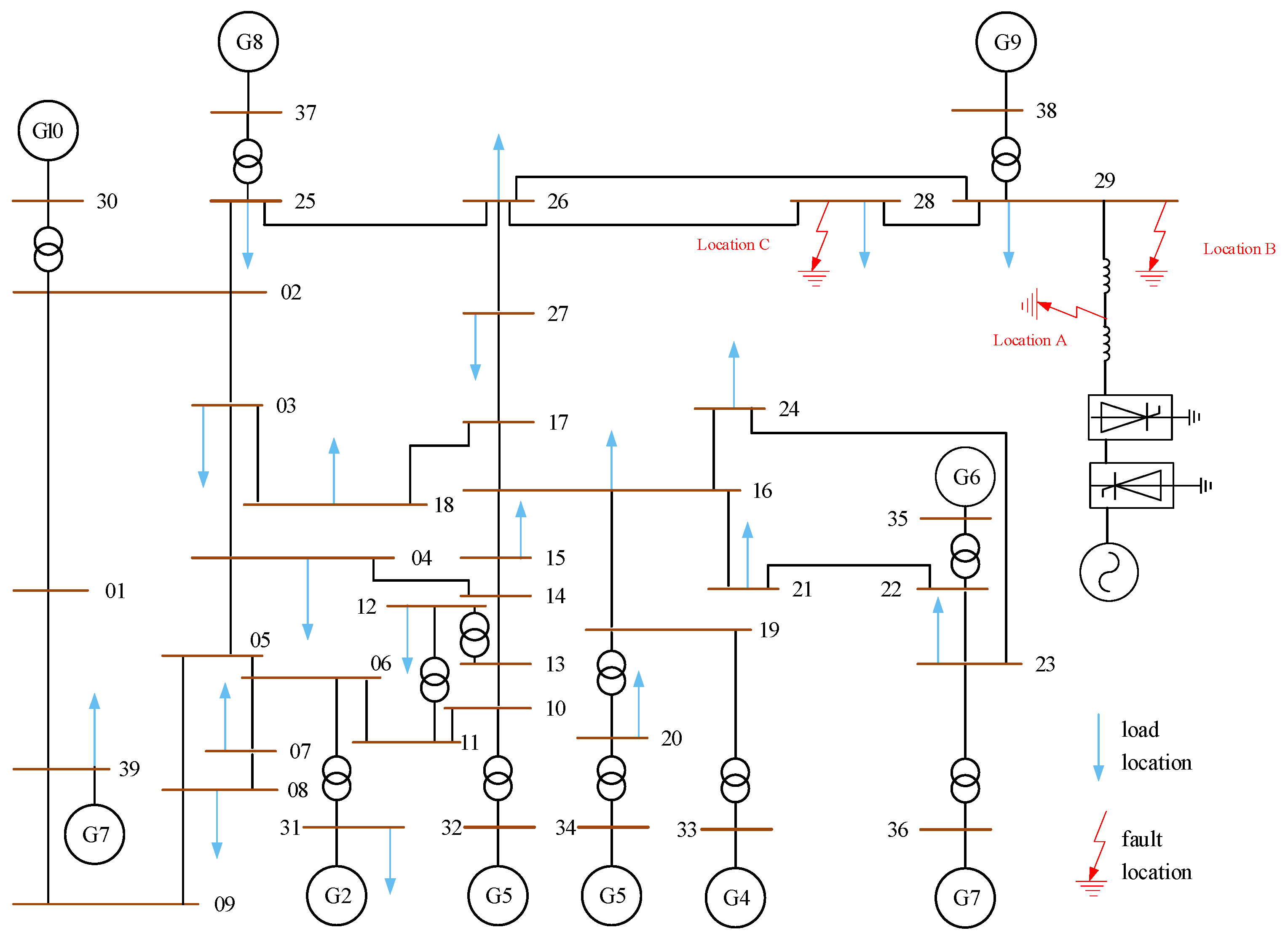

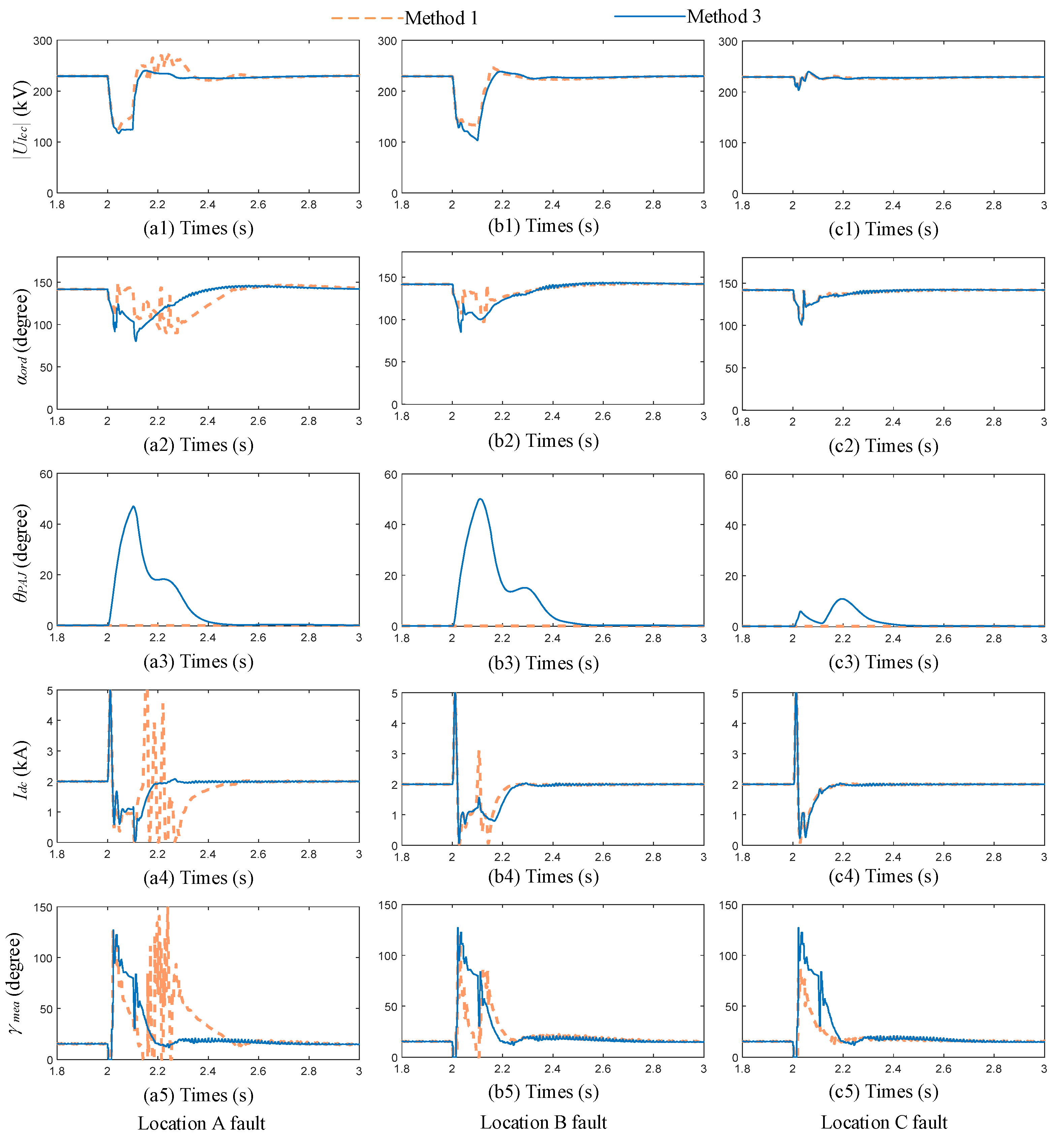

4.6. Validation of the Proposed Controller’s Effectiveness in IEEE 39-Bus System

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Acronyms | |

| ANR | AC network reconfigurations |

| ACC | AC network reconfiguration compensation controller |

| CFFR | commutation failure during fault recovery |

| CF | commutation failure |

| CDSC-PLL | cascaded delayed signal cancellation phase-locked loop |

| DPF | DC power fluctuations |

| DCC | DC power fluctuations compensation controller |

| FCF | first commutation failure |

| HVDC | high-voltage direct current |

| IS, ISB | inverter-side AC system, inverter-side commutation bus |

| LCC-HVDC | line-commutated converter high-voltage direct current |

| MAF-PLL | moving average filter phase-locked loop |

| PLL-PTE | phase-locked loop phase tracking error |

| PAJ | phase angle jump |

| PCC | point of common coupling |

| RS | rectifier-side AC system |

| SCR | short circuit ratio |

| SRF-PLL | synchronous reference frame phase-locked loop |

| Variables | |

| Eeq | AC voltage of equivalent voltage source |

| Idc | direct current of LCC-HVDC |

| If | fault current |

| PLCC, PLCC_f | active power output of LCC on AC side, active power output of LCC on AC side during the fault |

| Pdc | active power transmitted by LCC-HVDC on DC side |

| QLCC, QLCC_f | reactive power output of LCC on AC side, reactive power output of LCC on AC side during the fault |

| Rf | fault resistance |

| Tini, Tf | Initiation time and duration of fault |

| Udc_I | DC voltage of the inverter side |

| ULCC, ULCC_f | AC voltage of LCC, AC voltage of LCC during the fault |

| X1, X2, Xeq | impedance value between PCC and fault point, impedance value between equivalent voltage source and fault point, impedance value of equivalent circuit |

| α, β, γ | firing angle, firing advance angle, and extinction angle of thyristor |

| θ | phase angle |

| ω | angular velocity |

| Subscripts | |

| act | actual value of variables |

| eq | equivalent value of variables |

| mea | measured value of variables |

| min | minimum value of variables |

| N | rated value of variables |

| ref | reference value of variables |

| ord | order value of variables |

| Δ | variation in variables |

Appendix A

References

- Xue, Y.; Li, Z.; Chen, Y.; Zhen, W.; Teng, F.; Strbac, G.; Yang, C.; Tang, W. Sharing of Frequency Response Between Asynchronously Interconnected Systems with Renewable Generation Using LCC-HVDC. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2025. early access. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, J.; Xu, K.; Li, W. Research on the Power Coordinate Control Strategy between a CLCC-HVDC and a VSC-HVDC during the AC Fault Period. Energies 2024, 17, 4478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Li, J.; Li, H.; Yin, S.; Cai, Z. Detection for Abnormal Commutation Process State of Converter Based on Temporal and Amplitude Characteristics of AC Current. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 1052–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Xue, Y.; Tang, Y.; Chen, N.; Yang, C. Adaptive Advancement Angle Compensation for Suppressing Commutation Failures During Rectifier- and Inverter-Fault Recovery. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 4287–4301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Huang, M.; Fu, C.; Li, H.; Xu, S.; Li, X. A New Recovery Strategy of HVDC System During AC Faults. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2019, 34, 486–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, D.; He, S.; Huang, H.; Han, Z.; Cui, L.; Li, Y. Strategy for Suppressing Commutation Failures in High-Voltage Direct Current Inverter Station Based on Transient Overvoltage. Energies 2024, 17, 1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Yuan, Z.; Chen, D.; Li, Z.; Tang, X.; Song, Y.; Zhou, G. Research on Coordinated Control of Dynamic Reactive Power Sources of DC Blocking and Commutation Failure Transient Overvoltage in New Energy Transmission. Energies 2025, 18, 2349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Han, K.; Liu, S.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X.; Zou, K. A Dynamic Nonlinear VDCOL Control Strategy Based on the Taylor Expansion of DC Voltages for Suppressing the Subsequent Commutation Failure in HVDC Transmission. Energies 2023, 16, 7342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, X.P.; Yang, C. Elimination of Commutation Failures of LCC HVDC System with Controllable Capacitors. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2016, 31, 3289–3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; Yuan, X.; Zhang, M.; Hu, J. Supplementary Control for Mitigation of Successive Commutation Failures Considering the Influence of PLL Dynamics in LCC-HVDC Systems. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 8, 872–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golestan, S.; Guerrero, J.M.; Vasquez, J.C. Three-Phase PLLs: A Review of Recent Advances. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2017, 32, 1894–1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.T.; Wang, J.J.; Ye, Y.M.; Wang, Z.H. Influence of Different PLLs on the Stability of LCC-HVDC Control Loop. Power Syst. Technol. 2024, 48, 1202–1217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, I.; Ashraf, M. Comparison of Synchronization Techniques Under Distorted Grid Conditions. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 101345–101354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Gong, Y.; Fu, C.; Wen, Z.; Wu, Q. A Novel Phase-Locked Loop for Mitigating the Subsequent Commutation Failures of LCC-HVDC Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2021, 36, 1756–1767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, H.; Hao, L.; Huang, F.; Chen, Z.; He, J. Research on the Suppression Strategy of Commutation Failure Caused by AC Fault at the Sending End. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 3900–3911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, C.; Han, W.; Ouyang, J.; Xiong, X.; Wang, W. Ride-Through Control Method for the Continuous Commutation Failures of HVDC Systems Based on DC Emergency Power Control. Energies 2019, 12, 4183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, X.P.; Yang, C. AC Filterless Flexible LCC HVDC With Reduced Voltage Rating of Controllable Capacitors. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2018, 33, 5507–5518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Lin, W.; Lin, H. Estimation of Single-Phase Grid Voltage Parameters With Zero Steady-State Error. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2016, 31, 3867–3879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- China Electric Power Engineering Consulting Group Central Southern Electric Power Design Institute Co., Ltd. Design Manual for High-Voltage Direct Current Transmission; China Electric Power Press: Beijing, China, 2017; ISBN 9787519811990. [Google Scholar]

- Szechtman, M.; Wess, T.; Thio, C.V. A Benchmark Model for HVDC System Studies. In Proceedings of the International Conference on AC and DC Power Transmission, London, UK, 17–20 September 1991; pp. 374–378. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Lin, S.; Liu, J.; Sun, P.; Liao, K.; Li, X.; He, Z. Analysis and Prevention of Subsequent Commutation Failures Caused by Improper Inverter Control Interactions in HVDC Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2020, 35, 2841–2852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE Std 1204-1997; IEEE Guide for Planning DC Links Terminating at AC Locations Having Low Short-Circuit Capacities. IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 21 January 1997; pp. 1–216. [CrossRef]

| Transition Resistance (Ω) | PLL-PTE (deg) | CFFR | γmin (deg) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model I | Model II | Model I | Model II | Model I | Model II | |

| 1 | 55.7 | 37.7 | Yes | No | 0 | 21 |

| 20 | 41.7 | 26.7 | Yes | No | 0 | 14.9 |

| 40 | 33.5 | 19.2 | Yes | No | 0 | 17.2 |

| 60 | 28.5 | 14.9 | Yes | No | 0 | 8.8 |

| 80 | 25.1 | 14.0 | Yes | No | 0 | 12.5 |

| 100 | 21.4 | 13.5 | Yes | No | 0 | 11.3 |

| 120 | 20.0 | 12.6 | Yes | No | 0 | 11.4 |

| 140 | 18.9 | 12.0 | Yes | No | 0 | 13.3 |

| 160 | 17.1 | 11.0 | Yes | No | 0 | 12.9 |

| 180 | 16.5 | 10.9 | No | No | 7.3 | 14.4 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, J.; Yao, L.; Deng, J.; Liang, S.; Yuan, R.; Zhang, G.; Ge, X. A Novel Strategy for Preventing Commutation Failures During Fault Recovery Using PLL Phase Angle Error Compensation. Electronics 2025, 14, 4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234651

Deng J, Yao L, Deng J, Liang S, Yuan R, Zhang G, Ge X. A Novel Strategy for Preventing Commutation Failures During Fault Recovery Using PLL Phase Angle Error Compensation. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234651

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Junpeng, Liangzhong Yao, Jinglei Deng, Shuai Liang, Rongxiang Yuan, Guoju Zhang, and Xuefeng Ge. 2025. "A Novel Strategy for Preventing Commutation Failures During Fault Recovery Using PLL Phase Angle Error Compensation" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234651

APA StyleDeng, J., Yao, L., Deng, J., Liang, S., Yuan, R., Zhang, G., & Ge, X. (2025). A Novel Strategy for Preventing Commutation Failures During Fault Recovery Using PLL Phase Angle Error Compensation. Electronics, 14(23), 4651. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234651