Hyperspectral Imaging System Applications in Healthcare

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Objectives of the Review

- Analysis of the relevance of HSI in the context of contemporary healthcare;

- The exploration of the unique features of HSI, including the sensors, calibration, and types of images that may be produced using the HSI technique;

- Comparison of HSI with other techniques to determine the strengths and limitations of HSI systems;

- Recommendations on the process to improve HSI by considering the opportunities from technological breakthroughs.

1.2. Selected Sources

2. HSI and Related Concepts

2.1. Distinction from Multispectral Imaging

2.2. Comparison with Traditional Imaging

2.3. The Electromagnetic Spectrum and HSI

3. Fundamentals of Hyperspectral Imaging in Biomedical Context

3.1. HSI Data Cube

3.2. Acquisition Methods Through Hypercube

3.3. Spectral Basis in Tissue

3.4. Spectral Ranges in Medicine

4. Historical Development

4.1. Early Development of HSI

4.2. Historical Background of HSI in Healthcare

4.3. Technological Evolution of HSI Systems in the Medical Field

5. HSI Systems and Technologies

5.1. Components of the HSI System

5.1.1. High Spectral Resolution

5.1.2. Creation of Hyperspectral Data Cubes

5.1.3. Versatile Applications

5.1.4. Non-Destructive Analysis

5.2. Types of Hyperspectral Sensors

5.2.1. Push-Broom (Line Scanning) Sensors

5.2.2. Whisk-Broom (Point Scanning) Sensors

5.2.3. Snapshot Imaging Sensors

5.3. Platforms for HSI Data Acquisition

5.4. Advances in Sensor Technology

6. Pre-Processing and HSI Systems in Healthcare

6.1. Acquisition of Reflectance and Absorbance

6.2. Image Acquisition

6.2.1. Methods for Image Acquisition

6.2.2. Normalization and Scatter/Glare Correction

6.3. Noise Reduction and Correction

6.3.1. Sources of Noise

6.3.2. Noise Reduction Techniques

6.3.3. Smoothing, Band Pruning, and Hybrid Methods

6.3.4. Noise at Spectral-Range Edges

6.4. Background Removal Through Region-of-Interest Segmentation

6.5. Band Wavelength and Correlation

6.5.1. Selection of Wavelength Band

6.5.2. Correlation of Neighboring Spectral Bands

6.6. Data Normalization and Standardization

7. Applications of HSI Systems in the Healthcare Sector

7.1. Detection of Tumors

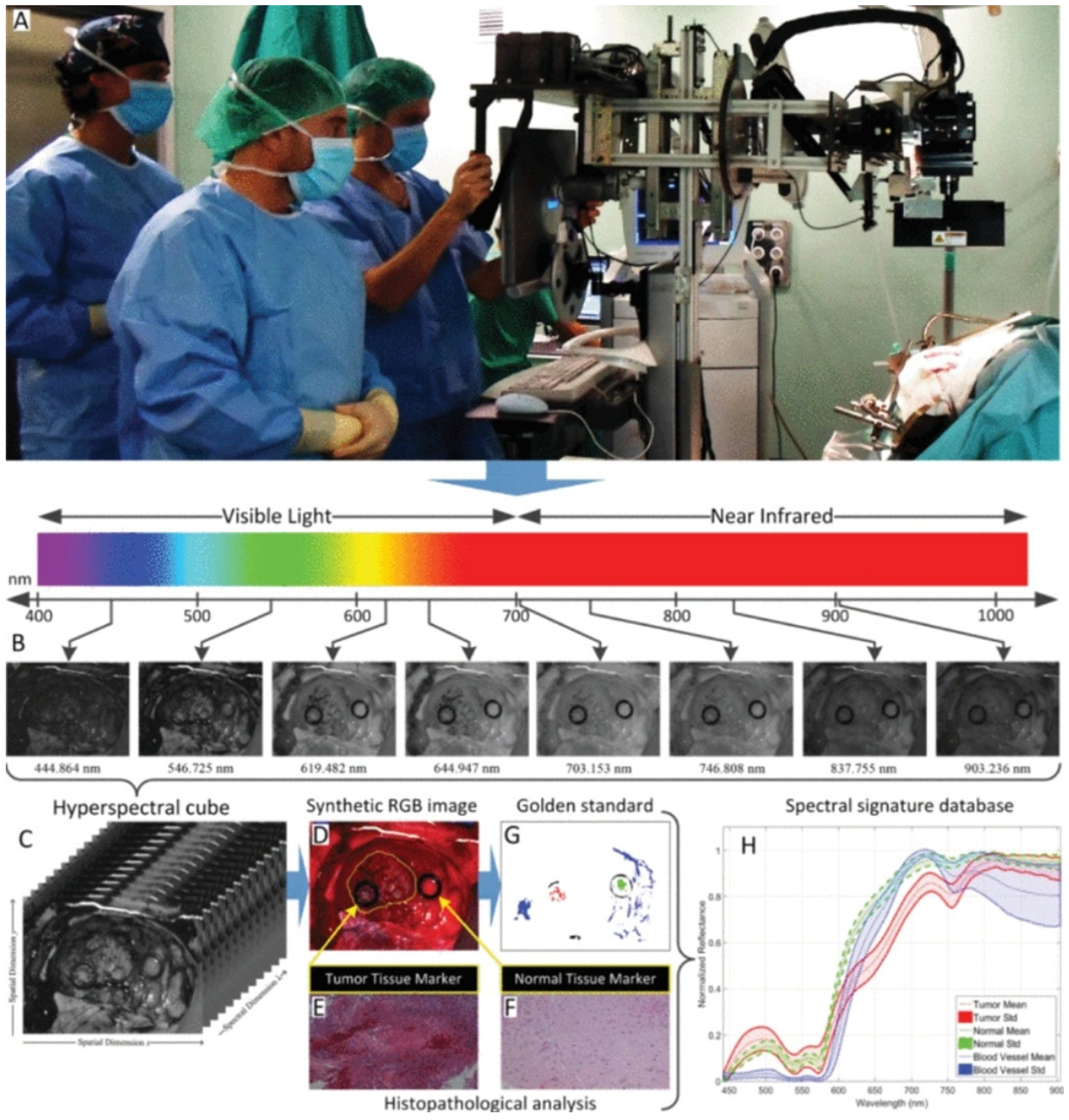

7.2. Image-Based Surgical Application

7.3. Burn Assessment and Wound Healing

7.4. Endoscopy and Gastrointestinal Imaging

7.5. Tissue Oxygenation and Perfusion Monitoring

8. Advanced Analytical Techniques for Hyperspectral Image Processing

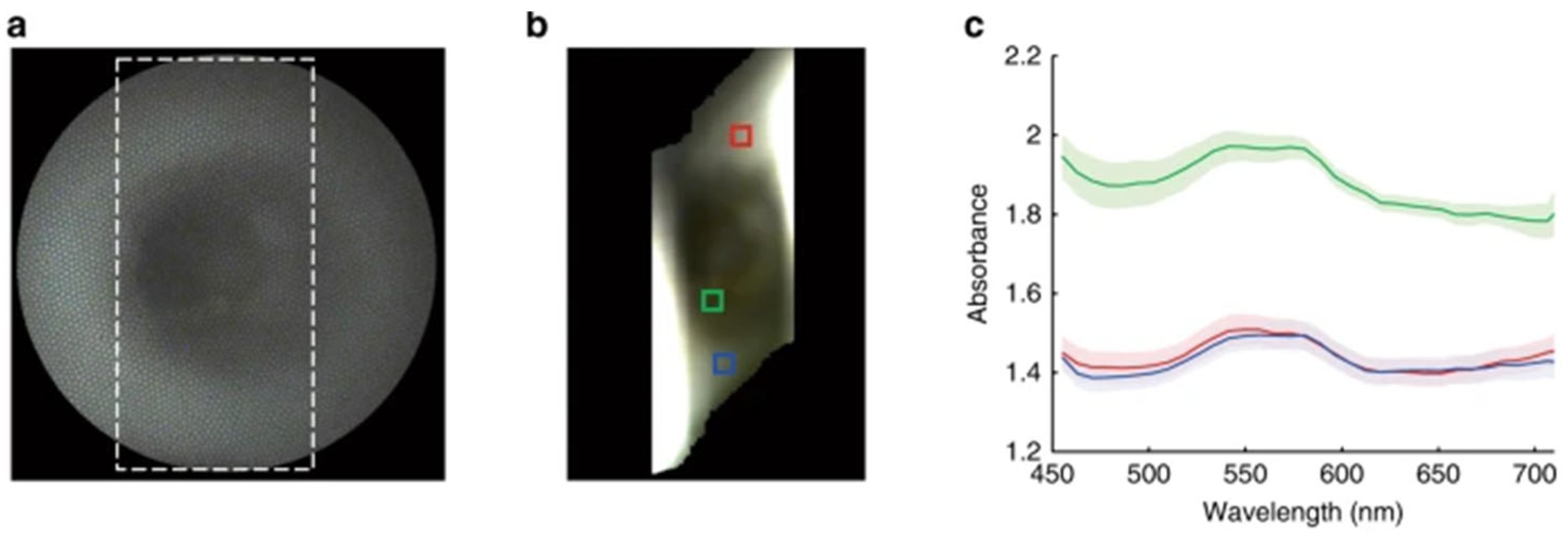

8.1. Spectral Feature Extraction in Clinical Hyperspectral Imaging

8.1.1. Reflectance and Absorbance Computation

8.1.2. Spectral Biomarkers for Specific Tissues

8.1.3. Construction of Spectral Vector

8.1.4. Application in Clinical Environments

8.1.5. Visualization of Spectral Discrimination

8.2. HSI and Dimensionality Reduction

8.2.1. Principal Component Analysis

8.2.2. Independent Component Analysis

8.3. Classification, Deep Learning Models, and Transformer Methods in Clinical HSI

8.3.1. Machine Learning Methods

8.3.2. Deep Learning Approaches

8.3.3. Transformer Methods

9. Clinical Utility and Emerging Impact Areas of HSI

9.1. HSI Utility in Organ Transplantation

9.2. Microcirculatory Monitoring in Critically Ill Patients

9.3. Screening of Ophthalmic Disease

9.4. Neonatal Jaundice Detection

9.5. Evaluation of Perfusion Quality in Haemodynamic Therapy

10. Challenges and Limitations

10.1. Data Complexity and Volume

10.2. High Computational Requirements

10.3. Cost and Accessibility of Equipment

10.4. Calibration and Standardization Issues

11. Recent Advances and Emerging Trends

11.1. Integration with Other Technologies

11.2. Miniaturization and Portability

11.3. Enhanced Data Processing Algorithms

11.4. Cloud Computing and Big Data Solutions

11.5. Advances in Sensor Materials and Design

12. Potential Research Areas

12.1. Advanced Machine Learning Techniques

12.2. Real-Time Data Processing and Analysis

12.3. Sensor Development and Optimization

12.4. Integration with IoT and Smart Systems

12.5. Enhanced Calibration and Standardization Methods

12.6. Standardization of HSI Protocols in Clinical Setups

12.7. Wearable HSI Devices

12.8. Real-Time Neuro-Vascular Imaging

13. Future Directions

13.1. Potential Breakthroughs

13.2. Creation of Disease-Specific Databases

13.3. Integrating HSI in Clinical Setups

13.4. Clinical Validation and Regulatory Standards

14. Conclusions

14.1. Summary of Key Points

14.2. Implications for Research and Industry

14.3. Future Research Directions

14.4. Final Thoughts

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Oyeniyi, J.; Oluwaseyi, P. Emerging Trends in AI-Powered Medical Imaging: Enhancing Diagnostic Accuracy and Treatment Decisions. Int. J. Enhanc. Res. Sci. Technol. Eng. 2024, 13, 2319–7463. [Google Scholar]

- Kitson, S.L. Modern Medical Imaging and Radiation Therapy. Open MedScience. 2024. Available online: https://openmedscience.com/wp-content/uploads/_pda/2024/05/Modern-Medical-Imaging-Radiation-Therapy.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Roya, M.; Mostafapour, S.; Mohr, P.; Providência, L.; Li, Z.; van Snick, J.H.; Brouwers, A.H.; Noordzij, W.; Willemsen, A.T.; Dierckx, R.A. Current and Future Use of Long Axial Field-of-View Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography Scanners in Clinical Oncology. Cancers 2023, 15, 5173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-GarciaLuna, J.L.; Martinez-Jimenez, M.A.; Fraser, R.D.; Bartlett, R.; Lorincz, A.; Liu, Z.; Berry, G.K. Is My Wound Infected? A Study on the Use of Hyperspectral Imaging to Assess Wound Infection. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1165281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, S.; Ma, D.; Tan, X.; Yang, M.; Jiao, Q.; Xu, L. Bibliometric Analysis of the Current Status and Trends on Medical Hyperspectral Imaging. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1235955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Landro, M.; Espíritu García-Molina, I.; Barberio, M.; Felli, E.; Agnus, V.; Pizzicannella, M.; Saccomandi, P. Hyperspectral Imagery for Assessing Laser-Induced Thermal State Change in Liver. Sensors 2021, 21, 643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akewar, M.; Chandak, M. Hyperspectral Imaging Algorithms and Applications: A Review. Available online: https://www.techrxiv.org/users/706929/articles/692094-hyperspectral-imaging-algorithms-and-applications-a-review?commit=853ecccdea95eedfb8dddf299a78d2b4a77cb7e9 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Hussain, S.; Mubeen, I.; Ullah, N.; Shah, S.S.U.D.; Khan, B.A.; Zahoor, M.; Ullah, R.; Khan, F.A.; Sultan, M.A. Modern diagnostic imaging technique applications and risk factors in the medical field: A review. BioMed Res. Int. 2022, 2022, 5164970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, D.; Pratap, B.; Boora, N.; Kumar, R.; Sah, N.K. A comparative study of medical imaging modalities. Int. J. Radiol. Sci. 2021, 3, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haleem, A.; Javaid, M.; Singh, R.P.; Suman, R. Medical 4.0 technologies for healthcare: Features, capabilities, and applications. Internet Things Cyber-Phys. Syst. 2022, 2, 12–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira Neto, N.F.d.; Caixeta, R.A.V.; Zerbinati, R.M.; Zarpellon, A.C.; Caetano, M.W.; Pallos, D.; Junges, R.; Costa, A.L.F.; Aitken-Saavedra, J.; Giannecchini, S.; et al. The Emergence of Saliva as a Diagnostic and Prognostic Tool for Viral Infections. Viruses 2024, 16, 1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karim, S.; Qadir, A.; Farooq, U.; Shakir, M.; Laghari, A.A. Hyperspectral Imaging: A Review and Trends towards Medical Imaging. Curr. Med. Imaging Rev. 2023, 19, 417–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, I.C.; Chen, Y.C.; Karmakar, R.; Mukundan, A.; Gabriel, G.; Wang, C.-C.; Wang, H.-C. Advancements in hyperspectral imaging and computer-aided diagnostic methods for the enhanced detection and diagnosis of head and neck cancer. Biomedicines 2024, 12, 2315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perri, A.; Vinco, L.; Polli, D.; Preda, F. A Fourier-Transform Hyperspectral Camera Based on a Common-Path Interferometer Working from 400 to 2200 nm. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1364/opticaopen.26927731.v1 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Magnusson, M.; Sigurdsson, J.; Armansson, S.E.; Ulfarsson, M.O.; Deborah, H.; Sveinsson, J.R. Creating RGB Images from Hyperspectral Images Using a Color Matching Function. In Proceedings of the IGARSS 2020—2020 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 26 September–2 October 2020; pp. 2045–2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.-Q.; Fan, Y.-H.; Jin, M.-S. Application of hyperspectral remote sensing for supplementary investigation of polymetallic deposits in Huaniushan ore region, northwestern China. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, S.E. Hyperspectral Satellites, Evolution, and Development History. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2021, 14, 7032–7056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, G.; Fei, B. Medical Hyperspectral Imaging: A Review. J. Biomed. Opt. 2014, 19, 010901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Space Agency (ESA). “Hyperspectral Imaging.” eoPortal Directory, 13 August 2023. Available online: https://www.eoportal.org/other-space-activities/hyperspectral-imaging (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Innoter. “Hyperspectral Imaging.” Innoter Articles. 15 December 2023. Available online: https://innoter.com/en/articles/hyperspectral-imaging/ (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Nireos. What is Hyperspectral Imaging? 2023. Available online: https://nireos.com/application/what-is-hyperspectral-imaging (accessed on 22 April 2025).

- JOUAV “Hyperspectral Imaging: Types, Benefits, and Applications.” JOUAV Blog, Updated September 4, 2024. Available online: https://www.jouav.com/blog/page/4 (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Morales, A.; Horstrand, P.; Guerra, R.; Leon, R.; Ortega, S.; Díaz, M.; Melián, J.M.; López, S.; López, J.F.; Callico, G.M.; et al. Laboratory Hyperspectral Image Acquisition System Setup and Validation. Sensors 2022, 22, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushalatha, M.R.; Prasantha, H.S. Pre-processing Approach for HIS. High Technol. Lett. 2022, 28, 462–476. [Google Scholar]

- Shaikh, M.S.; Jaferzadeh, K.; Thörnberg, B.; Casselgren, J. Calibration of a Hyper-Spectral Imaging System Using a Low-Cost Reference. Sensors 2021, 21, 3738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellar, R.G.; Boreman, G.D. Classification of Imaging Spectrometers for Remote Sensing Applications. Opt. Eng. 2005, 44, 013602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geladi, P.; Lestander, T.A.; Burger, J. HSI: Calibration Problems and Solutions. Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst. 2004, 72, 209–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hruska, R.; Mitchell, J.; Anderson, M.; Glenn, N.F. Radiometric and Geometric Analysis of Hyperspectral Imagery Acquired from an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 2736–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazdeyasna, S.; Arefin, M.S.; Fales, A.; Leavesley, S.J.; Pfefer, J.; Wang, Q. Evaluating Normalization Methods for Robust Spectral Performance Assessments of HSI Cameras. Biosensors 2025, 15, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.; Abdulla, W. Optimizing HSI Classification Performance with CNN and Batch Normalization. Appl. Spectrosc. Pract. 2023, 1, 27551857231204622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chang, C.-I. Independent Component Analysis-Based Dimensionality Reduction with Applications in Hyperspectral Image Analysis. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2006, 44, 1586–1600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgin, G.; Erturk, S.; Yildirim, T. Unsupervised Classification of Hyperspectral-Image Data Using Fuzzy Approaches That Spatially Exploit Membership Relations. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2008, 5, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Wang, X. Overview of Hyperspectral Image Classification. J. Sens. 2020, 2020, 4817234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Du, S. Spectral–Spatial Feature Extraction for Hyperspectral Image Classification: A Dimension Reduction and Deep Learning Approach. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2016, 54, 4544–4554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.X.; Xie, C.; Fan, Z.; Duan, Q.; Zhang, D.; Jiang, L.; Wei, X.; Hong, D.; Li, G.; Zeng, X.; et al. Hyperspectral Anomaly Detection Using Deep Learning: A Review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, R.; Yu, H.; Xu, T.; Xing, X.; Cao, X.; Yan, K.; Chen, J. Deep Learning in Medical Hyperspectral Images: A Review. Sensors 2022, 22, 9790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Booysen, R.; Lorenz, S.; Thiele, S.T.; Fuchsloch, W.C.; Marais, T.; Nex, P.A.; Gloaguen, R. Accurate HSI of Mineralized Outcrops: An Example from Lithium-Bearing Pegmatites at Uis, Namibia. Remote Sens. Environ. 2022, 269, 112790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wu, X.; He, L.; Meng, C.; Du, S.; Bao, J.; Zheng, Y. Applications of HSI in the Detection and Diagnosis of Solid Tumors. Transl. Cancer Res. 2020, 9, 1265–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, D.; Mallick, P.K.; Bhoi, A.K.; Ijaz, M.F.; Shafi, J.; Choi, J. Hyperspectral Image Classification: Potentials, Challenges, and Future Directions. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 3854635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucher, R.; Scheuermann, U.; Rademacher, S.; Lederer, A.; Sucher, E.; Hau, H.M.; Brandacher, G.; Schneeberger, S.; Gockel, I.; Seehofer, D. Intraoperative reperfusion assessment of human pancreas allografts using hyperspectral imaging (HSI). Hepatobiliary Surg. Nutr. 2022, 11, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markgraf, W.; Lilienthal, J.; Feistel, P.; Thiele, C.; Malberg, H. Algorithm for Mapping Kidney Tissue Water Content during Normothermic Machine Perfusion Using Hyperspectral Imaging. Algorithms 2020, 13, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.S.; Fereydooni, S.; Lee, M.C.; Polkampally, S.; Huynh, J.; Kuchibhotla, S.; Shah, M.M.; Ayoub, N.F.; Capasso, R.; Chang, M.T.; et al. Scoping review of deep learning research illuminates artificial intelligence chasm in otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. NPJ Digit Med. 2025, 8, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhargava, A.; Sachdeva, A.; Sharma, K.; Alsharif, M.H.; Uthansakul, P.; Uthansakul, M. Hyperspectral imaging and its applica-tions: A review. Heliyon 2024, 10, e33208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, C.L.; Karmakar, R.; Mukundan, A.; Natarajan, R.K.; Lu, S.C.; Wang, C.Y.; Wang, H.C. Advancing hyperspectral imaging and machine learning tools toward clinical adoption in tissue diagnostics: A comprehensive review. APL Bioeng. 2024, 8, 041504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Choi, W.J.; Oh, J.; Lee, K.; Kim, J.K. Smartphone-Based Rigid Endoscopy Device with Hemodynamic Response Imaging and Laser Speckle Contrast Imaging. Biosensors 2023, 13, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boese, A.; Wex, C.; Croner, R.; Liehr, U.B.; Wendler, J.J.; Weigt, J.; Illanes, A. Endoscopic imaging technology today. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, W.Y. Clustering-based compression connected to cloud databases in telemedicine and long-term care applications. Telemat. Inform. 2017, 34, 299–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Z.; Ding, X.; Hou, N.; Wan, J. A deep-learning-based collaborative edge–cloud telemedicine system for retinopathy of prematurity. Sensors 2022, 23, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yan, F.; Liu, P. The Application of Hyperspectral Imaging for Wheat Biotic and Abiotic Stress Analysis: A Review. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 221, 109008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazarika, C.J.; Borah, A.; Gogoi, P.; Ramchiary, S.S.; Daurai, B.; Gogoi, M.; Saikia, M.J. Development of non-invasive biosensors for neonatal jaundice detection: A review. Biosensors 2024, 14, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanegrungsunk, O.; Patikulsila, D.; Sadda, S.R. Ophthalmic imaging in diabetic retinopathy: A review. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2022, 50, 1082–1096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dietrich, M.; Marx, S.; von der Forst, M.; Bruckner, T.; Schmitt, F.C.F.; Fiedler, M.O.; Schmidt, K. Bedside hyperspectral imaging indicates a microcirculatory sepsis pattern—An observational study. Microvasc. Res. 2021, 136, 104164. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhatti, D.S.; Choi, Y.; Wahidur, R.S.; Bakhtawar, M.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, H.N. AI-Driven HSI: Multimodality, fusion, challenges, and the deep learning revolution. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.06894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, F.; Pfahl, A.; Köhler, H.; Vychopen, M.; Güresir, E.; Wach, J. Hyperspectral imaging and FLAIR signal intensity: A step toward improved detection of nonenhancing glioma tissue. Neurosurg. Focus 2025, 59, E5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römer, P.; Ponciano, J.-J.; Kloster, K.; Siegberg, F.; Plaß, B.; Vinayahalingam, S.; Al-Nawas, B.; Kämmerer, P.W.; Klauer, T.; Thiem, D. Enhancing Oral Health Diagnostics with Hyperspectral Imaging and Computer Vision: Clinical Dataset Study. JMIR Med. Inform. 2025, 13, e76148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tkachenko, M.; Chalopin, C.; Jansen-Winkeln, B.; Neumuth, T.; Gockel, I.; Maktabi, M. Impact of pre-and post-processing steps for supervised classification of colorectal cancer in hyperspectral images. Cancers 2023, 15, 2157. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar, S.; Arbabi, A.; Viegas, J. Advances in Spectral Imaging: A Review of Techniques and Technologies. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 35848–35902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Domingo, M.Á.; Valero-Benito, E.M.; Hernández-Andrés, J. Multispectral and Hyperspectral Imaging. In Non-Invasive and Non-Destructive Methods for Food Integrity; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 175–201. [Google Scholar]

- Kistler, M.; Köhler, H.; Theopold, J.; Gockel, I.; Roth, A.; Hepp, P.; Osterhoff, G. Intraoperative hyperspectral imaging (HSI) as a new diagnostic tool for the detection of cartilage degeneration. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskin, M.; Tamir, S. Dictionary of Nutraceuticals and Functional Foods; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jacques, S.L. Optical properties of biological tissues: A review. Phys. Med. Biol. 2013, 58, R37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.F.; Mukundan, A.; Karmakar, R.; Valappil, M.A.E.; Jouhar, J.; Wang, H.C. Modern Trends and Recent Applications of Hyperspectral Imaging: A Review. Technologies 2025, 13, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

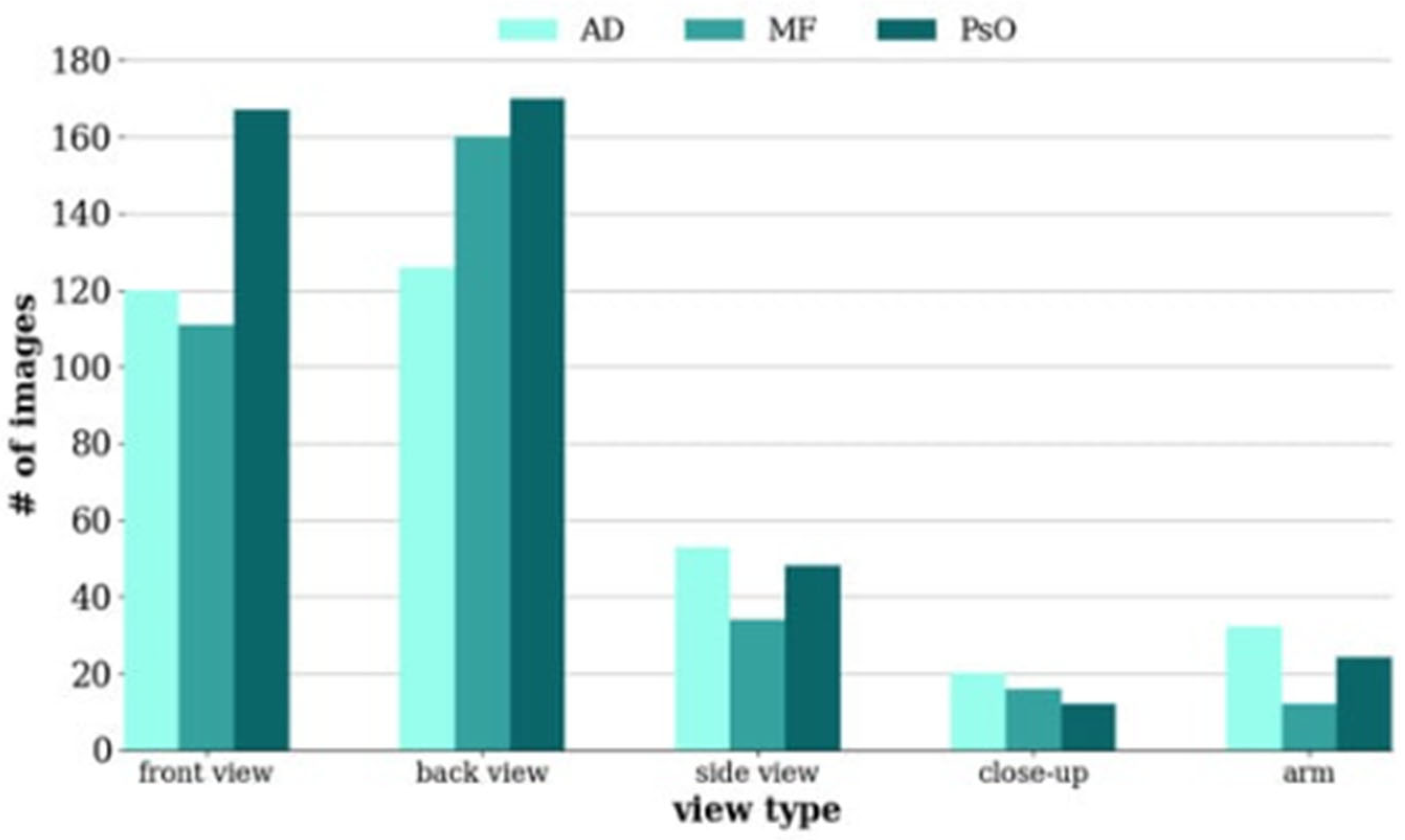

- Hetz, M.J.; Garcia, C.N.; Haggenmüller, S.; Brinker, T.J. Advancing dermatological diagnosis: Development of a hyperspectral dermatoscope for enhanced skin imaging. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.00612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, S.; Halicek, M.; Fabelo, H.; Callico, G.M.; Fei, B. Hyperspectral and multispectral imaging in digital and computational pathology: A systematic review. Biomed. Opt. Express 2020, 11, 3195–3233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kondratovich, V. Method for Assessment of the Apparent Detector Stack Position in a Whisk-Broom Sensor. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2022, 16, 014523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, K.; Wang, M.; Chen, M.; Wang, X.; Ni, K.; Zhou, Q.; Bai, B. Snapshot Spectral Imaging: From Spatial-Spectral Mapping to Metasurface-Based Imaging. Nanophotonics 2024, 13, 1303–1330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabelo, H.; Ortega, S.; Szolna, A.; Bulters, D.; Piñeiro, J.F.; Kabwama, S.; JO’Shanahan, A.; Bulstrode, H.; Bisshopp, S.; Kiran, B.R.; et al. In-vivo hyperspectral human brain image database for brain cancer detection. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 39098–39116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Singh, K.K.; Pandey, P.C.; Devrani, R.; Pandey, A.K.; Raju, K.P.; Pandey, M. Spectral Indices across Remote Sensing Platforms and Sensors Relating to the Three Poles: An Overview of Applications, Challenges, and Future Prospects. In Advances in Remote Sensing Technology and the Three Poles; John Wiley and Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2022; pp. 83–116. [Google Scholar]

- Rasti, B.; Scheunders, P.; Ghamisi, P.; Licciardi, G.; Chanussot, J. Noise Reduction in Hyperspectral Imagery: Overview and Application. Remote Sens. 2018, 10, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhaminia, B.; Alsalemi, A.; Nasir, E.; Jahanifar, M.; Awan, R.; Young, L.S.; Raza, S.E.A. From Traditional to Deep Learning Approaches in Whole Slide Image Registration: A Methodological Review. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.19123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witteveen, M.; Sterenborg, H.J.; van Leeuwen, T.G.; Aalders, M.C.; Ruers, T.J.; Post, A.L. Comparison of preprocessing techniques to reduce non-tissue-related variations in hyperspectral reflectance imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 2022, 27, 106003. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, H.; Ren, Y.; Yu, L.; Cai, Z.; Xia, X.; Qi, G.; Shen, C. Enhancing the Accuracy of Skin Lesion Diagnosis Using Hyperspectral Imaging and Deep Learning. J. Biophotonics 2025, 18, e202500182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Chen, B.; Zhang, J.; Xue, L.; Zhu, L. A new HSI denoising method via interpolated block matching 3D and guided filter. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gupta, P.; Jaiswal, G.; Kumar, A. Recent Advances in Denoising Techniques for Hyperspectral Image Enhancement. In International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Speech Technology; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang, L.; Ng, M.K. FastHyMix: Fast and parameter-free hyperspectral image mixed noise removal. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 34, 4702–4716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, J.M.; Dias, J.M. Vertex component analysis: A fast algorithm to unmix hyperspectral data. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2005, 43, 898–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Vega, B.; Tkachenko, M.; Matkabi, M.; Ortega, S.; Fabelo, H.; Balea-Fernandez, F.; Chalopin, C. Evaluation of Preprocessing Methods on Independent Medical Hyperspectral Databases to Improve Analysis. Sensors 2022, 22, 8917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachdeva, S.; Bhatia, S.; Al Harrasi, A.; Shah, Y.A.; Anwer, M.K.; Philip, A.K.; Halim, S.A. Unraveling the Role of Cloud Computing in Health Care System and Biomedical Sciences. Heliyon 2024, 10, e29044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

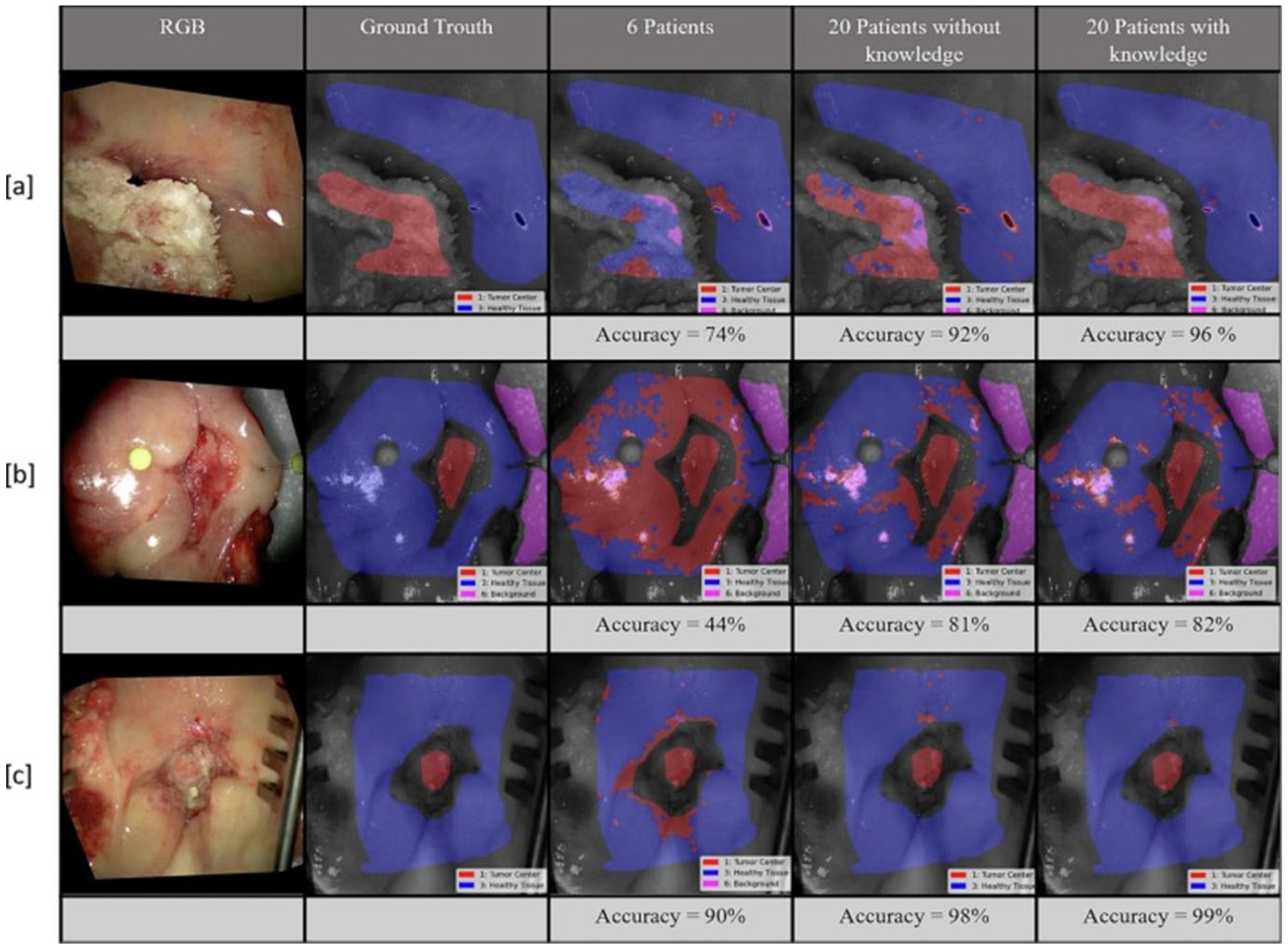

- Giannantonio, T.; Alperovich, A.; Semeraro, P.; Atzori, M.; Zhang, X.; Hauger, C.; De Vleeschouwer, S. Intra-Operative Brain Tumor Detection with Deep Learning-Optimized Hyperspectral Imaging. In Optical Biopsy XXI: Toward Real-Time Spectroscopic Imaging and Diagnosis; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2023; Volume 12373, pp. 80–98. [Google Scholar]

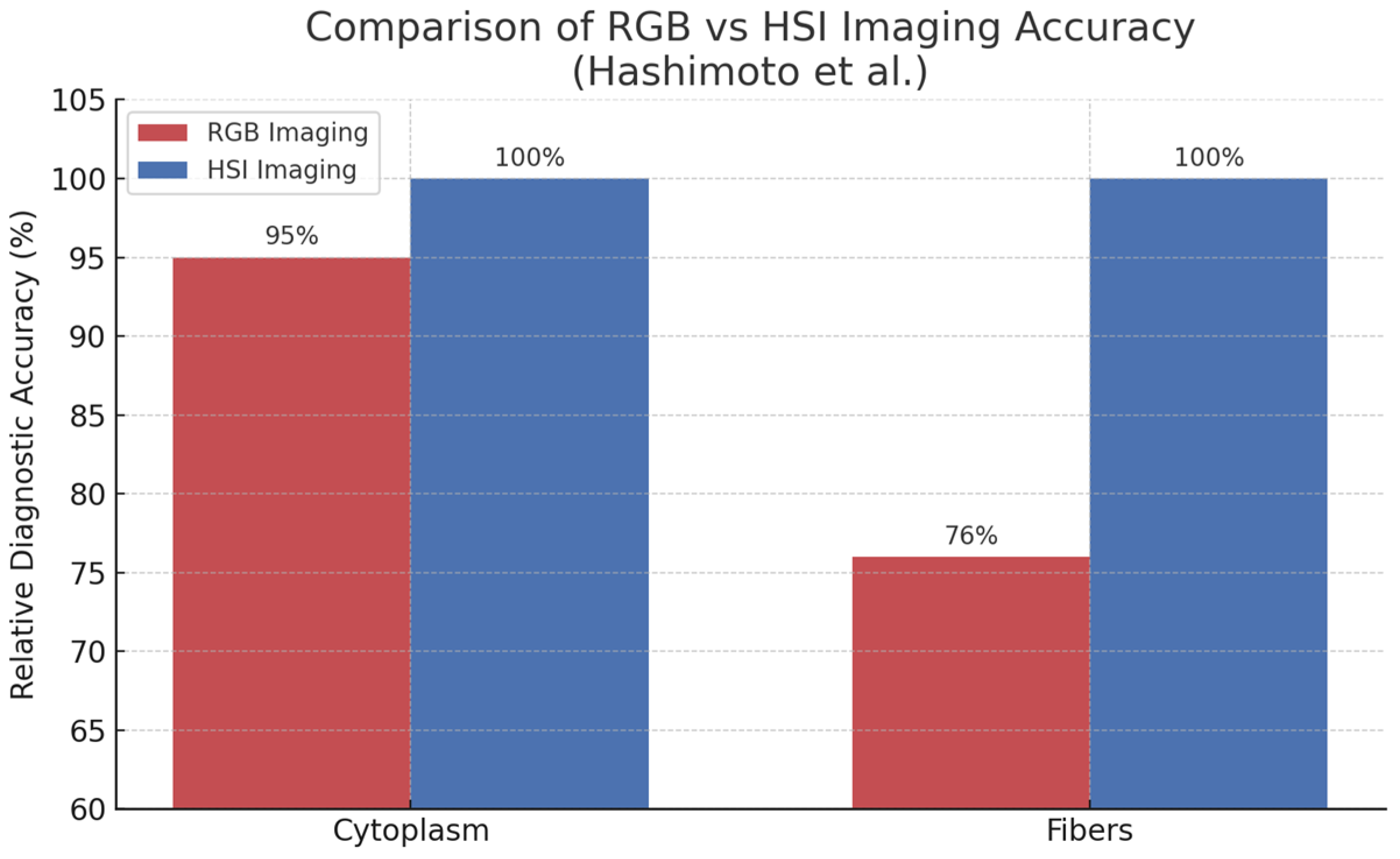

- Hashimoto, E.; Ishikawa, M.; Shinoda, K.; Hasegawa, M.; Komagata, H.; Kobayashi, N.; Hashizume, M. Tissue Classification of Liver Pathological Tissue Specimens Image Using Spectral Features. In Medical Imaging 2017: Digital Pathology; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2017; Volume 10140, pp. 243–248. [Google Scholar]

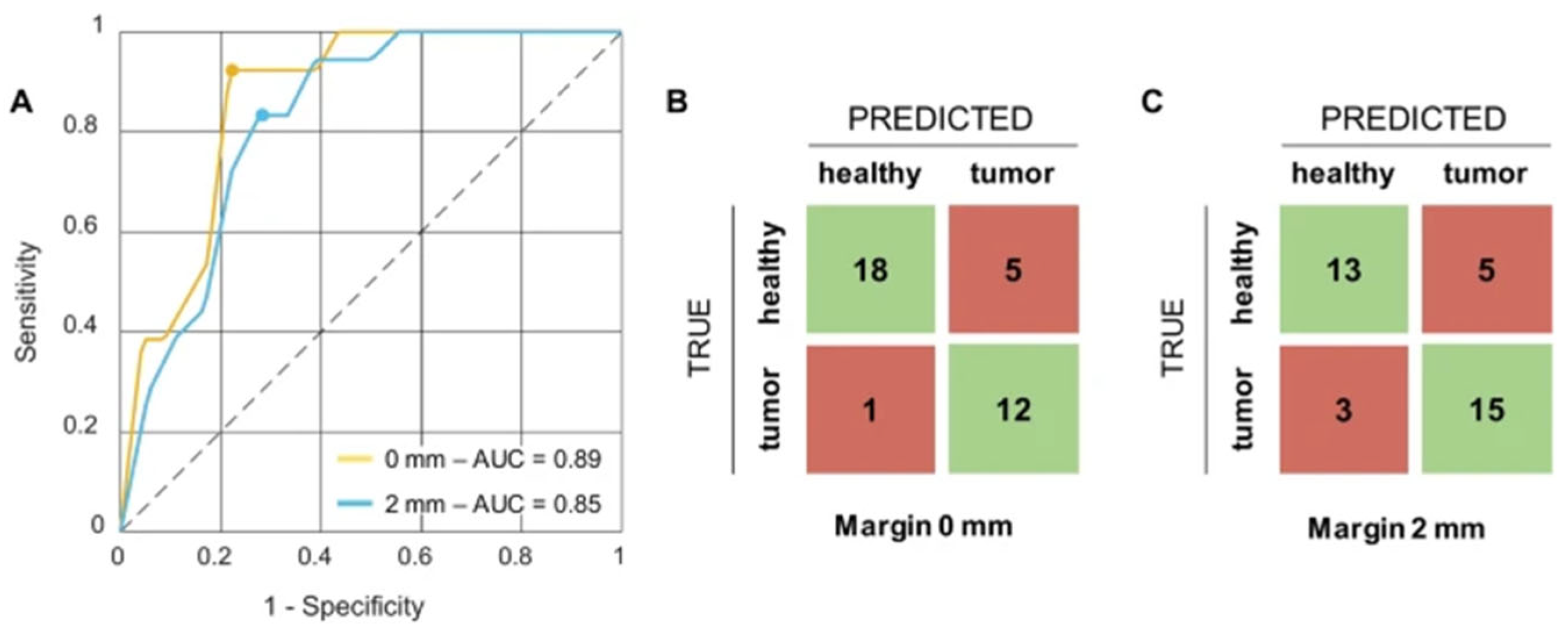

- Boehm, F.; Alperovich, A.; Schwamborn, C.; Mostafa, M.; Giannantonio, T.; Lingl, J.; Schuler, P.J. Enhancing Surgical Precision in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck: Hyperspectral Imaging and Artificial Intelligence for Improved Margin Assessment in an Ex Vivo Setting. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2025, 332, 125817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jong, L.J.S.; Veluponnar, D.; Geldof, F.; Sanders, J.; Guimaraes, M.D.S.; Vrancken Peeters, M.J.T.; Ruers, T.J. Toward Real-Time Margin Assessment in Breast-Conserving Surgery with Hyperspectral Imaging. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 9556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marotz, J.; Schulz, T.; Seider, S.; Cruz, D.; Aljowder, A.; Promny, D.; Siemers, F. 3D-Perfusion Analysis of Burn Wounds Using Hyperspectral Imaging. Burns 2021, 47, 157–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.Y.; Nguyen, H.T.; Lin, T.L.; Saenprasarn, P.; Liu, P.H.; Wang, H.C. Identification of Skin Lesions by Snapshot Hyperspectral Imaging. Cancers 2024, 16, 217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.Y.; Hsiao, Y.P.; Mukundan, A.; Tsao, Y.M.; Chang, W.Y.; Wang, H.C. Classification of Skin Cancer Using Novel Hyperspectral Imaging Engineering via YOLOv5. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, J.; Joseph, J.; Waterhouse, D.J.; Luthman, A.S.; Gordon, G.S.; Di Pietro, M.; Januszewicz, W.; Fitzgerald, R.C.; Bohndiek, S.E. A Clinically Translatable Hyperspectral Endoscopy (HySE) System for Imaging the Gastrointestinal Tract. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 1902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Huang, P.; He, P.; Wei, B.; Guo, X.; Xiao, H.; Sun, Y.; Tian, S.; Zhou, M.; Feng, P. DCA-DAFFNet: An end-to-end network with deformable fusion attention and deep adaptive feature fusion for laryngeal tumor grading from histopathology images. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 5031115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, B.; Dao, P.D.; Liu, J.; He, Y.; Shang, J. Recent Advances of HSI Technology and Applications in Agriculture. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 2659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, T.; Mukhopadhyay, S.C.; Da Costa, J.P.J.; RoyChaudhuri, C.; Lan, L.; Demitri, N. Spatial Environment Perception and Sensing in Automated Systems: A Review. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 21813–21833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezhov, I.; Giannoni, L.; Shit, S.; Lange, F.; Kofler, F.; Menze, B.; Tachtsidis, I.; Rueckert, D. Identifying Chromophore Fingerprints of Brain Tumor Tissue on Hyperspectral Imaging Using Principal Component Analysis. In European Conference on Biomedical Optics; Optica Publishing Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; p. 1262826. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Su, H.; Shen, J. Hyperspectral Dimensionality Reduction Based on Multiscale Superpixelwise Kernel Principal Component Analysis. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndu, H.; Sheikh-Akbari, A.; Singh, K.K. Enhancing Vein Detection in Hyperspectral Images Using Correlation-PCA Fusion and Clustering. In Proceedings of the 2024 8th International Conference on Imaging, Signal Processing and Communications (ICISPC), Fukuoka, Japan, 19–21 January 2024; pp. 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicek, M.; Lu, G.; Little, J.V.; Wang, X.; Patel, M.; Griffith, C.C.; Chen, A.Y.; El-Deiry, M.W.; Fei, B. Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Classifying Head and Neck Cancer Using Hyperspectral Imaging. J. Biomed. Opt. 2017, 22, 060503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poonkuzhali, P.; Prabha, K.H. Deep Convolutional Neural Network Based Hyperspectral Brain Tissue Classification. J. X-Ray Sci. Technol. 2023, 31, 777–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengs, M.; Westermann, S.; Gessert, N.; Eggert, D.; Gerstner, A.O.; Mueller, N.A.; Betz, C.; Laffers, W.; Schlaefer, A. Spatio-Spectral Deep Learning Methods for In-Vivo Hyperspectral Laryngeal Cancer Detection. In Medical Imaging 2020: Computer-Aided Diagnosis; SPIE: Bellingham, WA, USA, 2020; Volume 11314, pp. 369–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halicek, M.; Little, J.V.; Wang, X.; Chen, A.Y.; Fei, B. Optical Biopsy of Head and Neck Cancer Using Hyperspectral Imaging and Convolutional Neural Networks. J. Biomed. Opt. 2019, 24, 036007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Guerrero, I.A.; Campos-Delgado, D.U.; Mejía-Rodríguez, A.R.; Leon, R.; Ortega, S.; Fabelo, H.; Camacho, R.; Plaza, M.D.L.L.; Callico, G. Hybrid Brain Tumor Classification of Histopathology Hyperspectral Images by Linear Unmixing and an Ensemble of Deep Neural Networks. Healthc. Technol. Lett. 2024, 11, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; He, P.; Tian, S.; Ma, M.; Feng, P.; Xiao, H.; Mercaldo, F.; Santone, A.; Qin, J. A ViT-AMC network with adaptive model fusion and multiobjective optimization for interpretable laryngeal tumor grading from histopathological images. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2022, 42, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Luo, F.; Yang, X.; Wang, Q.; Sun, Y.; Tian, S.; Feng, P.; Huang, P.; Xiao, H. The Swin-Transformer network based on focal loss is used to identify images of pathological subtypes of lung adenocarcinoma with high similarity and class imbalance. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 149, 8581–8592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, P.; Xiao, H.; He, P.; Li, C.; Guo, X.; Tian, S.; Feng, P.; Chen, H.; Sun, Y.; Mercaldo, F.; et al. La-vit: A network with transformers constrained by learned-parameter-free attention for interpretable grading in a new laryngeal histopathology image dataset. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inform. 2024, 28, 3557–3570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietrich, M.; Oezdemir, B.; Gruneberg, D.; Petersen, C.; Studier-Fischer, A.; von der Forst, M.; Schmitt, F.C.F.; Fiedler, M.O.; Nickel, F.; Müller-Stich, B.P.; et al. Hyperspectral imaging for the evaluation of microcirculatory tissue oxygenation and perfusion quality in haemorrhagic shock: A porcine study. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuzak, K.J.; Wehner, E.; Rao, S.; Litorja, M.; Allen, D.W.; Singer, M.; Livingston, E. The robustness of DLP hyperspectral imaging for clinical and surgical utility. Proc. SPIE 2010, 7596, 22–30. [Google Scholar]

- Clancy, N.T.; Jones, G.; Maier-Hein, L.; Elson, D.S.; Stoyanov, D. Surgical spectral imaging. Med. Image Anal. 2020, 63, 101699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdelmajeed, A.Y.; Juszczak, R. Challenges and Limitations of Remote Sensing Applications in Northern Peatlands: Present and Future Prospects. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, A.; Harrison, N.; French, A.P. Hyperspectral Image Analysis Techniques for the Detection and Classification of the Early Onset of Plant Disease and Stress. Plant Methods 2017, 13, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stuart, M.B.; McGonigle, A.J.; Willmott, J.R. HSI in Environmental Monitoring: A Review of Recent Developments and Technological Advances in Compact Field Deployable Systems. Sensors 2019, 19, 3071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noor Asmat, B.; Syed Muhammad Bilal, H.; Uddin, M.I.; Khalid Karim, F.; Mostafa, S.M.; Varela-Aldás, J. Enhancing feature learning of hyperspectral imaging using shallow autoencoder by adding parallel paths encoding. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 17363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golovynskyi, S.; Golovynska, I.; Roganova, O.; Golovynskyi, A.; Qu, J.; Ohulchanskyy, T.Y. Hyperspectral Imaging of Lipids in Biological Tissues Using Near-Infrared and Shortwave Infrared Transmission Mode: A Pilot Study. J. Biophotonics 2023, 16, e202300018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sowmya, V.; Soman, K.P.; Hassaballah, M. Hyperspectral image: Fundamentals and advances. In Recent Advances in Computer Vision: Theories and Applications; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 401–424. [Google Scholar]

- Kurzawa, M.; Jędryczka, C.; Wojciechowski, R.M. Application of Multi-Branch Cauer Circuits in the Analysis of Electromagnetic Transducers Used in Wireless Transfer Power Systems. Sensors 2020, 20, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, D.; Manickavasagan, A. Machine Learning Techniques for Analysis of Hyperspectral Images to Determine Quality of Food Products: A Review. Curr. Res. Food Sci. 2021, 4, 28–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, F.; Gao, M.; Li, J.; Lu, W.; Wu, C. Compact dual-channel (hyperspectral and video) endoscopy. Front. Phys. 2020, 8, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aversano, N.; Bonifazi, G.; D’Adamo, I.; Palmieri, S.; Serranti, S.; Simone, A. Circular and Sustainable Space: Findings from HIS. J. Clean. Prod. 2024, 471, 143386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, J.; Yousaf, A.; Khan, H.S.; Khan, H.S.; Khurshid, K. Modern Trends in Hyperspectral Image Analysis: A Review. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 14118–14129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruan, Q.; Moradian-Oldak, J. Development of amelogenin-chitosan hydrogel for in vitro enamel regrowth with a dense interface. J. Vis. Exp. 2014, 89, 51606. [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal, G.; Rani, R.; Mangotra, H.; Sharma, A. Integration of HSI and Autoencoders: Benefits, Applications, Hyperparameter Tuning, and Challenges. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2023, 50, 100584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picollo, M.; Cucci, C.; Casini, A.; Stefani, L. Hyper-Spectral Imaging Technique in the Cultural Heritage Field: New Possible Scenarios. Sensors 2020, 20, 2843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALThagafi, S.H.; ALMutairi, A.A.; Qassem, O.K.; Sbeay, N.E.A.L.; Sowailim, I.S.A.L. Revolutionizing healthcare: The technological transformation of medical laboratory outcomes. Int. J. Biol. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 8, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, A.; Hadoux, X.; van Wijngaarden, P. Hyperspectral retinal imaging biomarkers of ocular and systemic diseases. Eye 2025, 39, 667–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, D.; Bai, X.; Zhang, W. Progress in the application of hyperspectral imaging technology in quality detection and in the modernization of Chinese herbal medicines. Front. Chem. 2025, 13, 1620154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, J. Hyperspectral imaging for clinical applications. BioChip J. 2022, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Author(s), Year | Method | Application | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hussain et al., 2022 [8] | Diagnostic Imaging | Medical Field | Disease detection through modern imaging. |

| Kumar et al., 2021 [9] | Comparative Study | Medical Imaging | Image modality comparison |

| Haleem et al., 2022 [10] | Medical 4.0 Tech | Healthcare | IoT and cyber-physical systems |

| Oliveira Neto et al., 2024 [11] | Saliva Diagnostics | Viral Infections | Diagnostic tool potential |

| Karim et al., 2023 [12] | HSI Overview | Medical Imaging | Trends in hyperspectral imaging |

| Wu et al., 2024 [13] | Diagnostic Imaging | Hyperspectral images | Head and Neck cancer results accuracy |

| Akewar & Chandak, 2024 [7] | HSI Algorithms | General Imaging | Challenges include data complexity and algorithm limitations. |

| Perri et al., 2024 [14] | FT HSI Camera | Optical Sensing | Fourier-transform hyperspectral camera |

| Magnusson et al., 2020 [15] | Color Matching | Hyperspectral | RGB creation from HSI data |

| Wan et al., 2021 [16] | Remote Sensing | Ore Investigation | HSI in mining exploration |

| Qian, 2021 [17] | Hyperspectral Satellites | Remote Sensing | Evolution of hyperspectral satellites |

| Lu & Fei, 2014 [18] | HSI Overview | Medical Imaging | Medical HSI applications |

| ESA, 2023 [19] | HSI Overview | General | Space-based HSI applications |

| Innoter, 2023 [20] | HSI Overview | General | HSI tech applications in everyday life |

| Nireos, 2023 [21] | HSI Overview | General | Applications in multiple sectors |

| JOUAV, 2024 [22] | HSI Overview | General | Applications in surveillance & security |

| Morales et al., 2022 [23] | HSI System Setup | Laboratory | Hyperspectral system validation |

| Kushalatha & Prasantha, 2022 [24] | HSI Preprocessing | General | Pre-processing techniques for HSI |

| Shaikh et al., 2021 [25] | HSI Calibration | Imaging Systems | Low-cost calibration method |

| Sellar & Boreman, 2005 [26] | Imaging Classification | Remote Sensing | Classification methods for remote sensing |

| Geladi et al., 2004 [27] | HSI Calibration | General | Calibration challenges in HSI |

| Hruska et al., 2012 [28] | HSI Analysis | UAV Imaging | UAV-based HSI analysis for remote sensing |

| Mazdeyasna et al., 2025 [29] | Normalization Methods | HSI Cameras | Normalization for spectral performance |

| Zhang & Abdulla, 2023 [30] | CNN and Batch Normalization | HSI Classification | Optimizing classification performance |

| Wang & Chang, 2006 [31] | ICA Dimensionality Reduction | HSI Analysis | ICA for dimensionality reduction in HSI |

| Bilgin et al., 2008 [32] | Unsupervised Classification | Remote Sensing | Fuzzy-based classification of HSI |

| Lv & Wang, 2020 [33] | HSI Overview | Image Classification | HSI classification methods reviewed |

| Zhao & Du, 2016 [34] | Feature Extraction | HSI Classification | Spectral-Spatial feature extraction |

| Hu et al., 2022 [35] | Anomaly Detection | Remote Sensing | Deep learning for anomaly detection |

| Cui et al., 2022 [36] | Deep Learning | Medical HSI | Applications of deep learning in medical HSI |

| Booysen et al., 2022 [37] | HSI of Minerals | Remote Sensing | HSI for mineral detection in Africa |

| Zhang et al., 2020 [38] | Tumor Detection | Medical | HSI in solid tumor diagnosis |

| Datta et al., 2022 [39] | HSI Classification | General | Challenges in HSI classification |

| Sucher et al., 2024 [40] | HSI Analysis | Medical Imaging | HSI enabled intraoperative perfusion monitoring |

| Markgraf et al., 2020 [41] | Anomaly Detection | Medical | Accurate prediction of kidney tissue |

| Liu et al., 2025 [42] | Comparative study | Medical Imaging | Image modality trends |

| Bhargava et al., 2024 [43] | Disease Detection | Medical Imaging | Challenges in clinical translation |

| Lai et al., 2024 [44] | HSI Application | Medical Imaging | Disease detection through medical imaging |

| Kim et al., 2017 [45] | Diagnostic imaging | Healthcare/Cardiovascular | Smartphone-endoscope with LSCI enabled real-time blood perfusion mapping |

| Boese et al., 2022 [46] | Comparative Study | Medical Imaging | Image modality comparison |

| Hsu et al., 2017 [47] | HSI Algorithms | Healthcare | clustering-based compression improved telemedicine data transfer and storage |

| Luo et al., 2022 [48] | Medical 4.0 Tech | Medical Imaging | AI-enabled edge–cloud telemedicine |

| Zhang et al., 2024 [49] | HSI Overview | General | Trends in hyperspectral imaging |

| Hazarika et al., 2024 [50] | Saliva Diagnostics | Healthcare | Early-stage development of non-invasive biosensors for neonatal jaundice |

| Nanegrungsunk et al., 2022 [51] | Diagnostic Imaging | Medical Imaging | Review of retinal imaging techniques in diabetic retinopathy |

| Dietrich et al., 2021 [52] | HSI Analysis | Medical Field | HSI monitored microcirculatory oxygenation and perfusion |

| Bhatti et al., 2025 [53] | Deep Learning | Detection and delineation of glioma tissue | Deep learning enhances HSI healthcare accuracy. |

| Weber et al., 2025 [54] | FLAIR-MRI sequence | Develops DL algorithms for endoscopic HSI data | Accuracy in detecting non-enhancing glioma tissue Intraoperative oral diagnostics and noninvasive pathological tissue analysis for early cancer detection. |

| Romer et al., 2025 [55] | Endoscopic HSI system | Colorectal cancer detection | Provide unique preprocessing configurations for better classification performance in medical imaging. |

| Tkachenko et al., 2025 [56] | Spectrum scaling | Cancer diagnosis | Enable improved classification compared to raw spectral features. |

| Spectral Range (nm) | Dominant Absorber | Diagnostic Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| 520–580 | Oxyhemoglobin (HbO2) | Tissue perfusion, inflammation [89]. |

| 600–750 | Deoxyhemoglobin (Hb) | Tumor hypoxia, ischemic regions [90]. |

| 900–1000 | Water | Hydration status, edema, burn depth analysis [89]. |

| 1000–1400 | Lipids and proteins | Tumor boundary delineation, soft tissue contrast [89]. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wołk, K.; Wołk, A. Hyperspectral Imaging System Applications in Healthcare. Electronics 2025, 14, 4575. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234575

Wołk K, Wołk A. Hyperspectral Imaging System Applications in Healthcare. Electronics. 2025; 14(23):4575. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234575

Chicago/Turabian StyleWołk, Krzysztof, and Agnieszka Wołk. 2025. "Hyperspectral Imaging System Applications in Healthcare" Electronics 14, no. 23: 4575. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234575

APA StyleWołk, K., & Wołk, A. (2025). Hyperspectral Imaging System Applications in Healthcare. Electronics, 14(23), 4575. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14234575