An Emotional AI Chatbot Using an Ontology and a Novel Audiovisual Emotion Transformer for Improving Nonverbal Communication

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Proposed Methodology

3.1. Facial Feature Preprocessing

3.2. Audio Feature Preprocessing

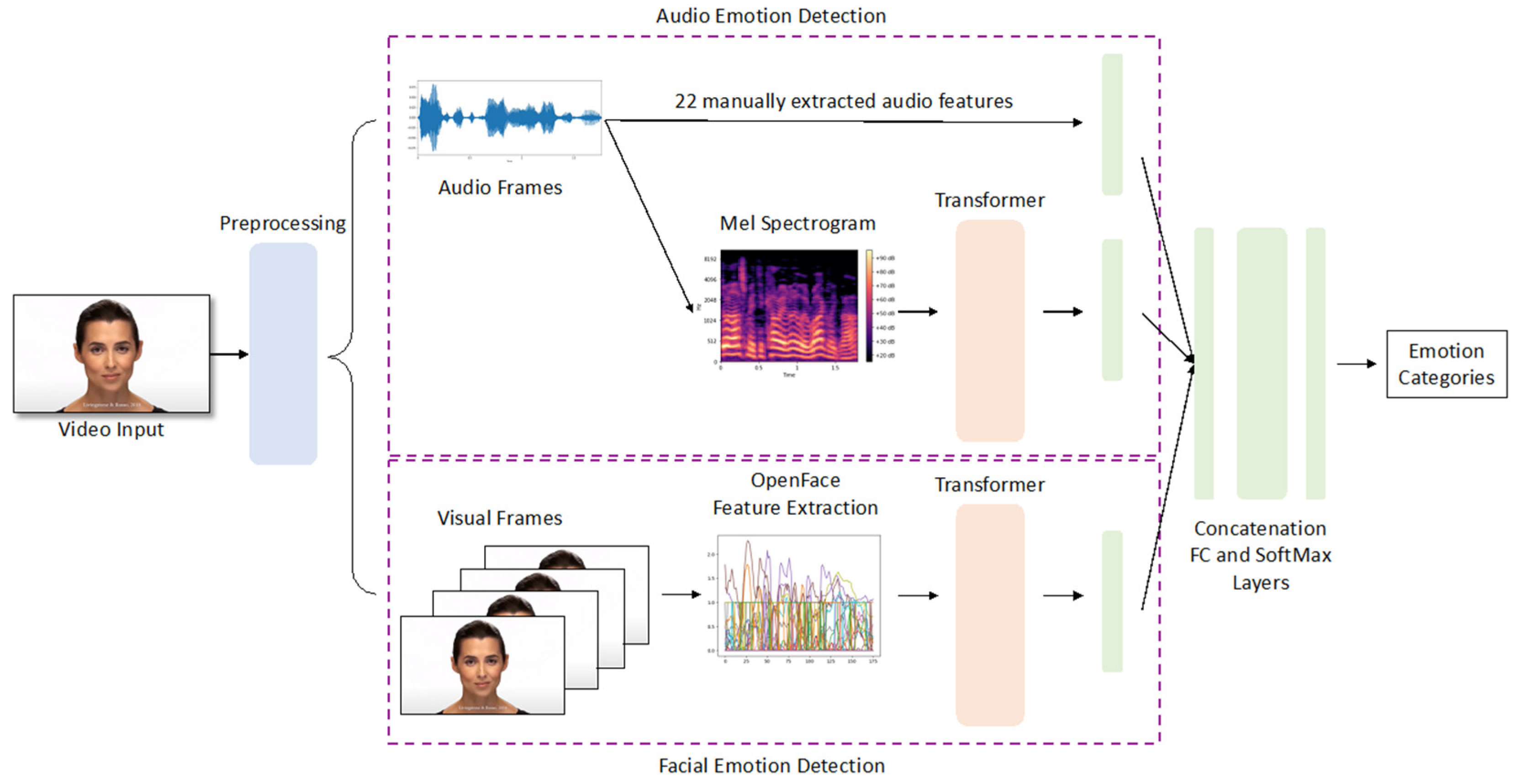

3.3. Transformer-Based Audiovisual Network Architecture

3.4. System Architecture of the Emotion-Ontology-Based Chatbot Engine

4. Experimental Results

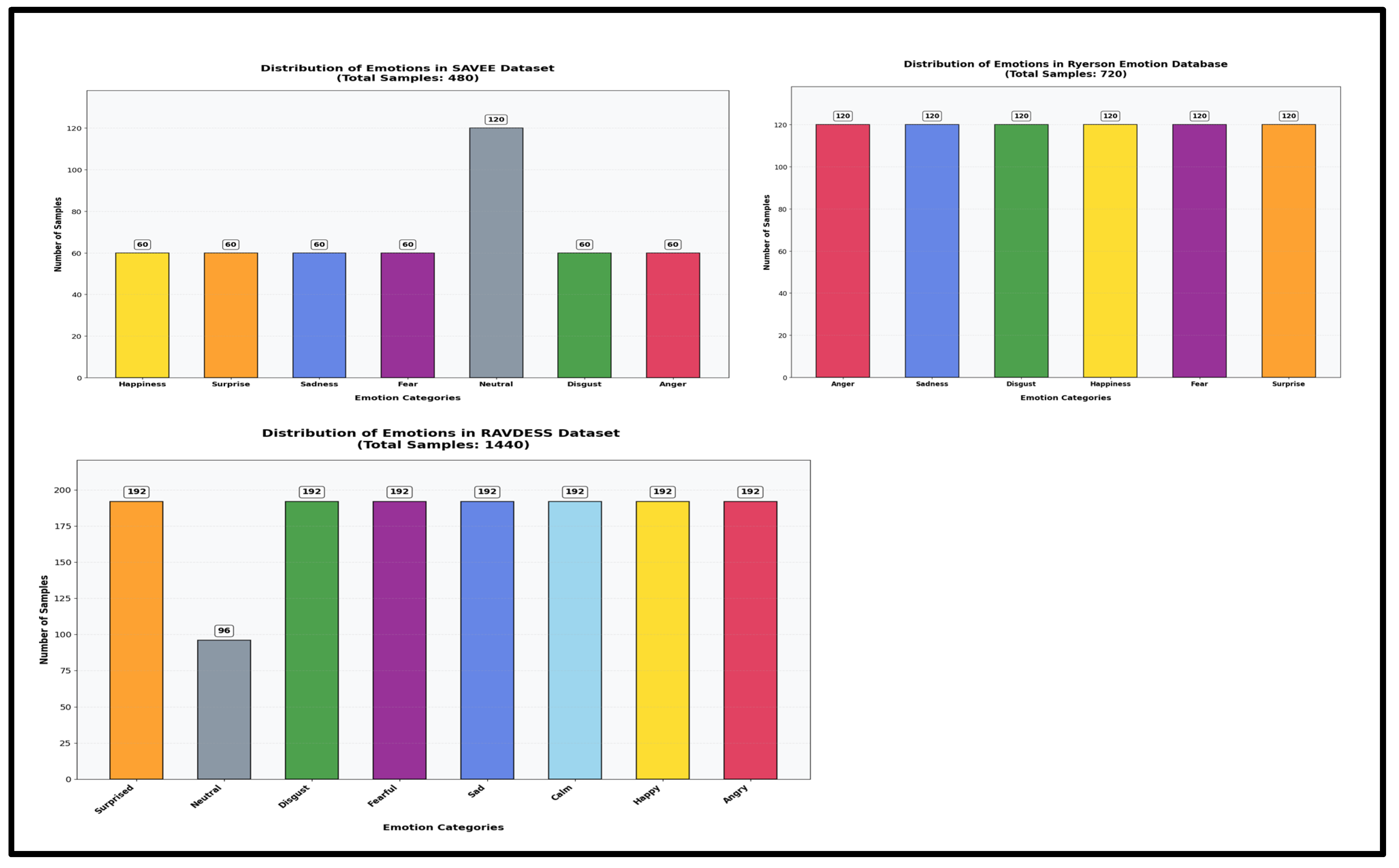

4.1. Datasets

- The Surrey Audio-Visual Expressed Emotion (SAVEE) dataset [15] consists of recordings from four native male British actors at the University of Surrey in seven distinct emotions: neutrality, happiness, sadness, anger, fear, disgust, and surprise. Each actor contributes 120 English utterances, resulting in a total of 480 video samples.

- The Ryerson Audio-Visual Database of Emotion Speech and Song (RAVDESS) dataset [46] contains audio-video clips from 24 professional actors (12 females, 12 males) vocalizing two lexically matched statements in a neutral North American accent. Eight emotion classes are covered: neutrality, calmness, happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust. In our study, we selected only the speech part of the dataset, resulting in 2880 video samples.

- The Ryerson Emotion Lab (RML) dataset [47] contains 720 video samples from eight actors speaking six languages (English, Mandarin, Urdu, Punjabi, Persian, and Italian). Various accents of English and Mandarin are included. Six principal emotions are delivered: happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disgust.

4.2. Parameter Configurations

4.3. Evaluation Metric

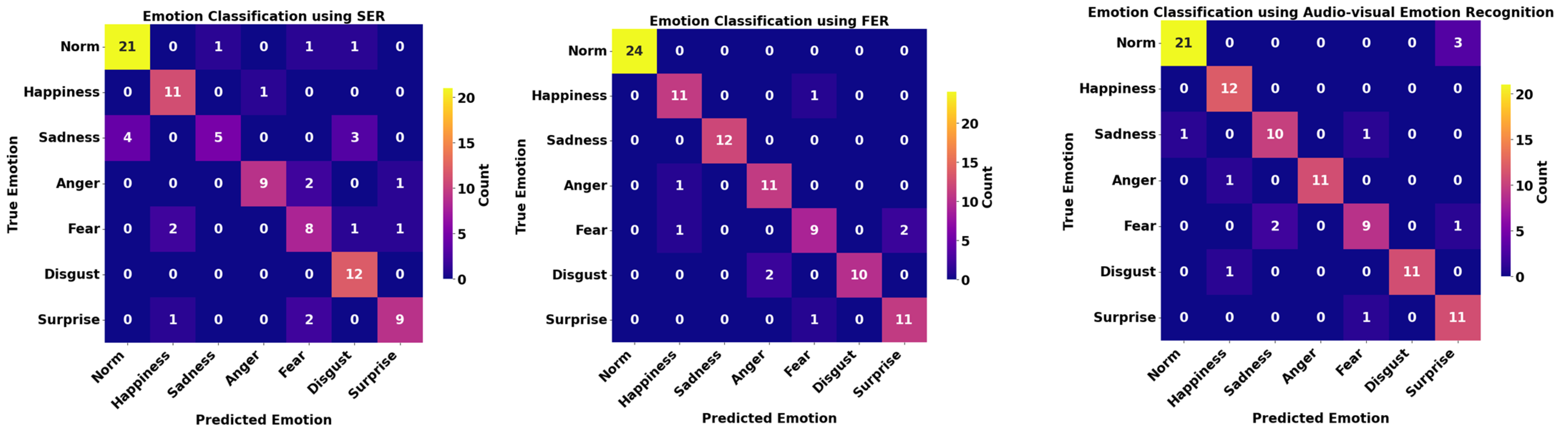

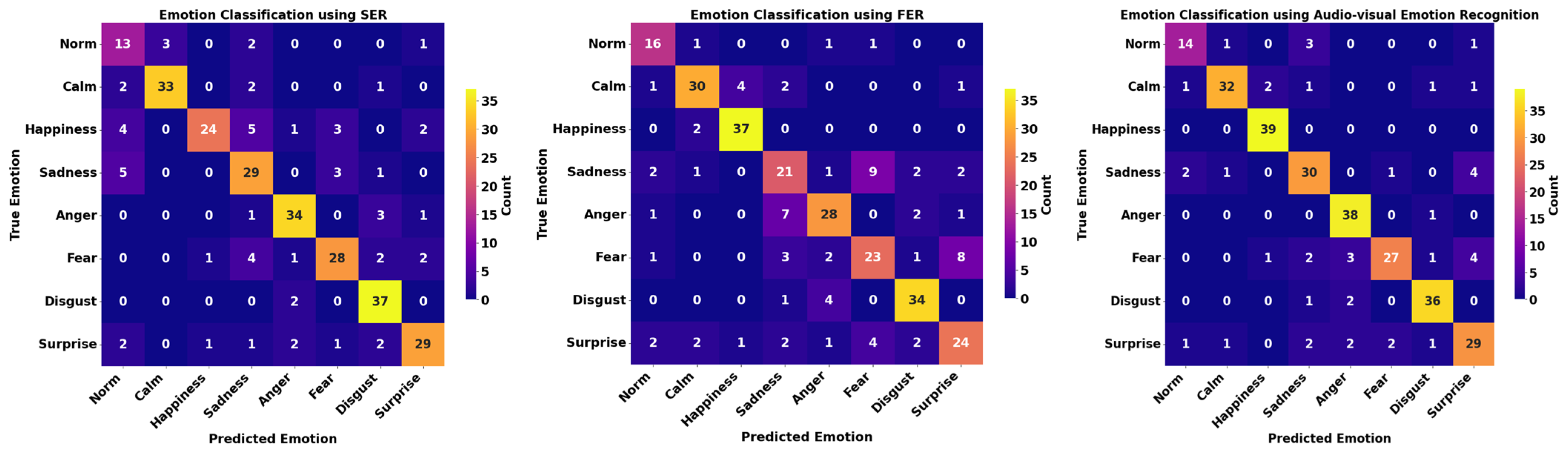

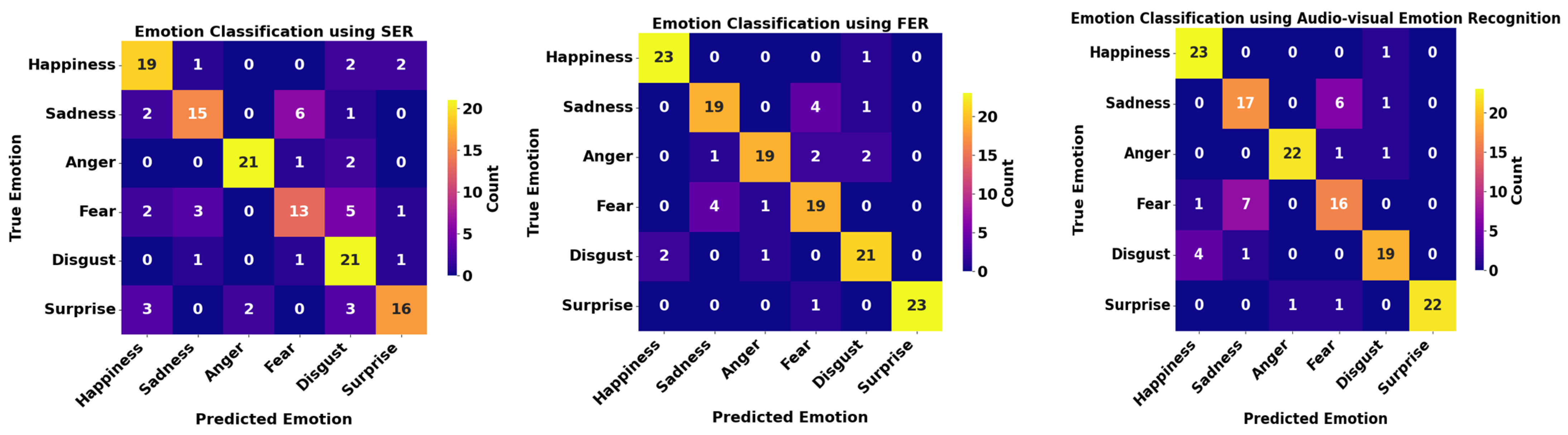

4.4. Results

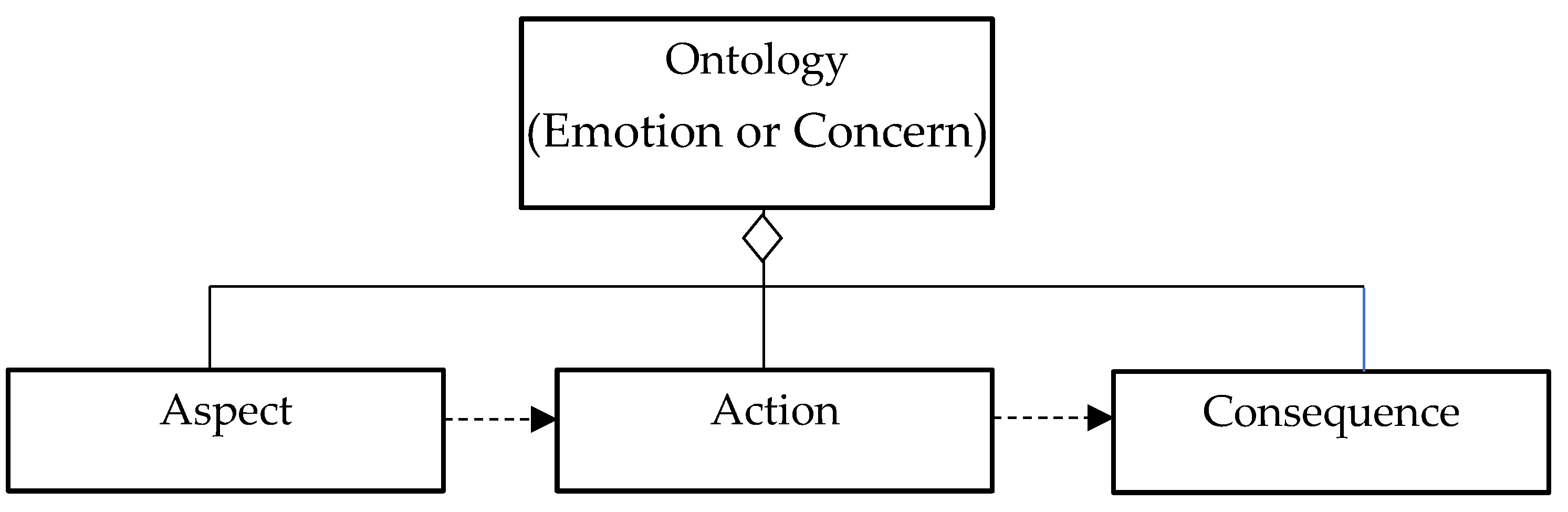

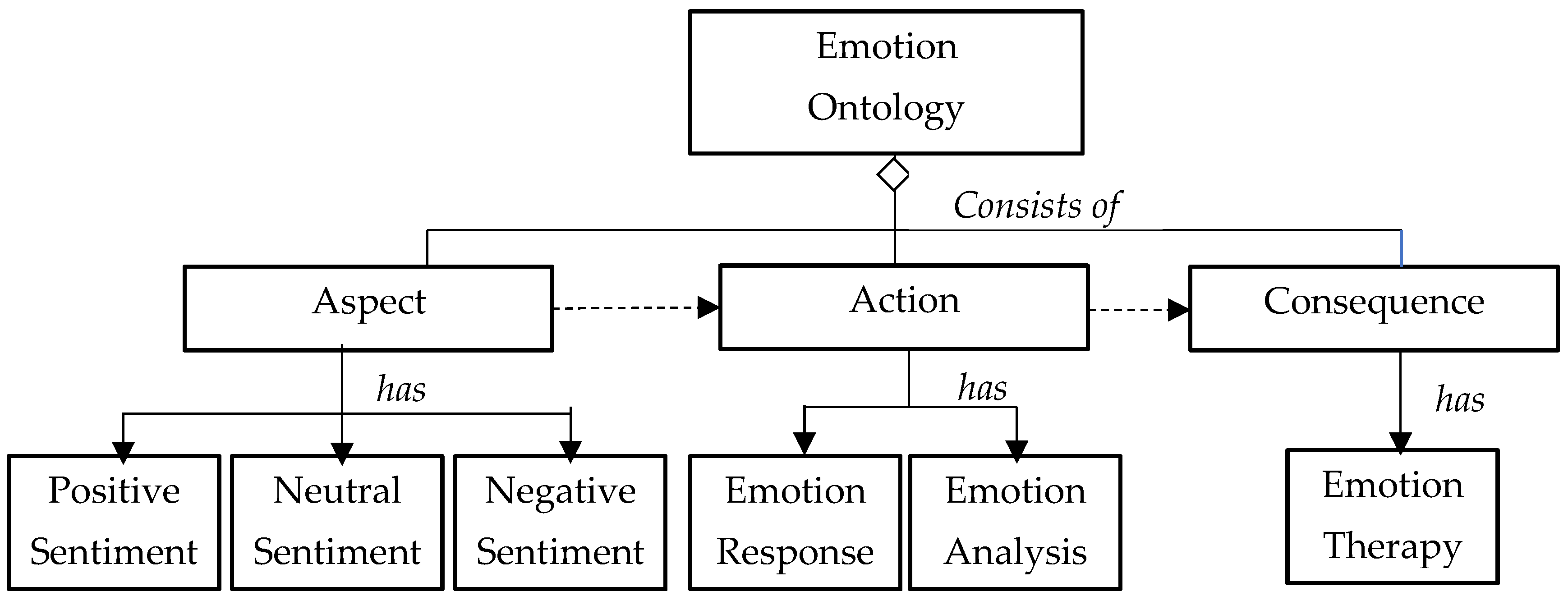

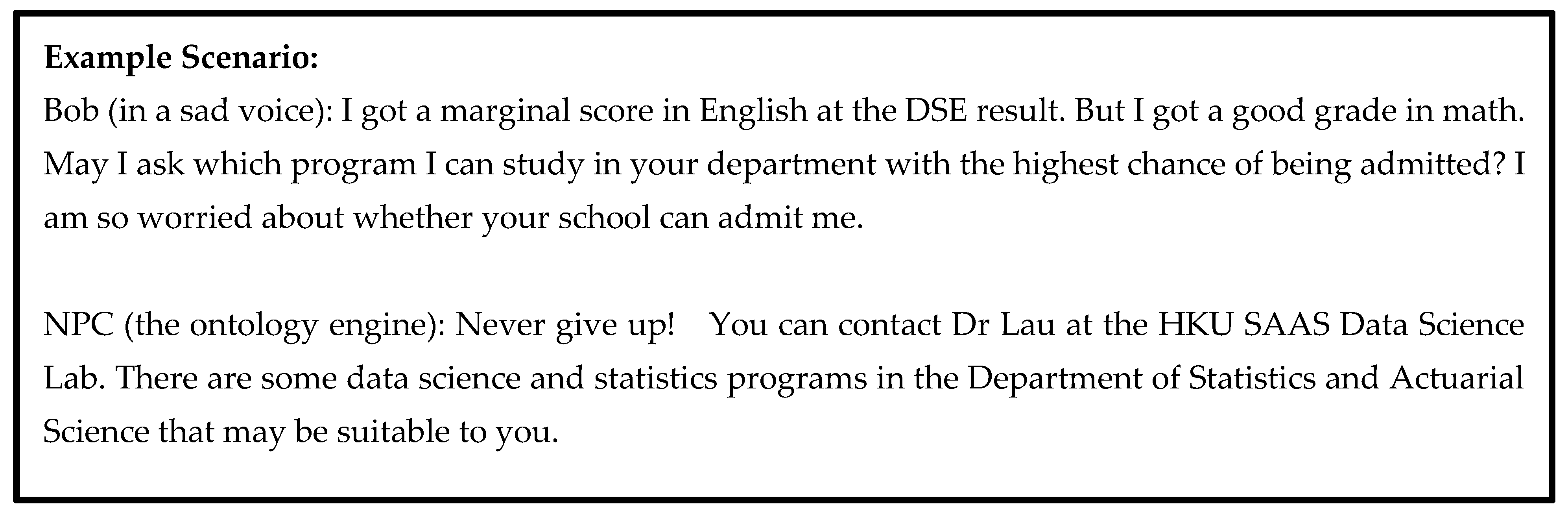

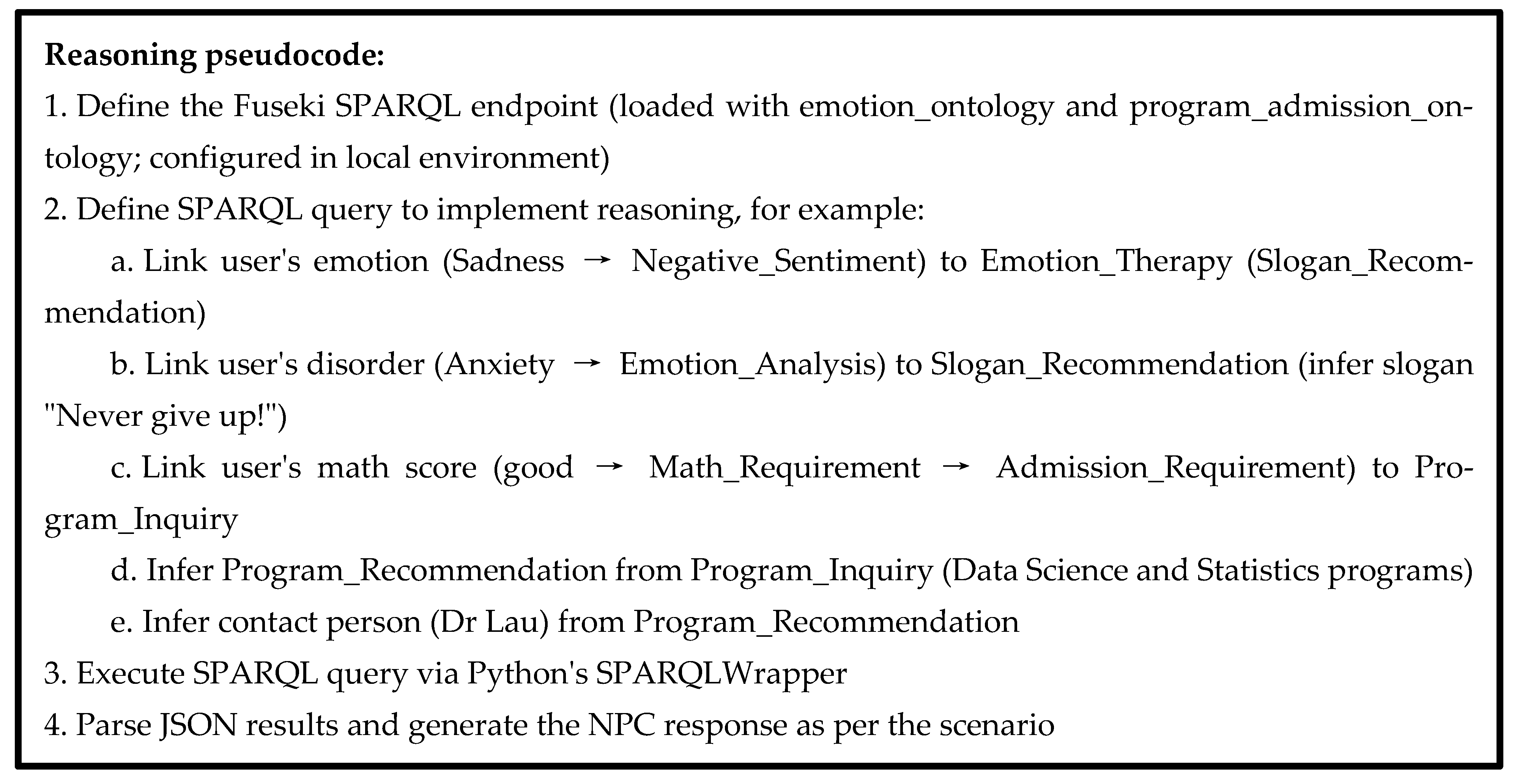

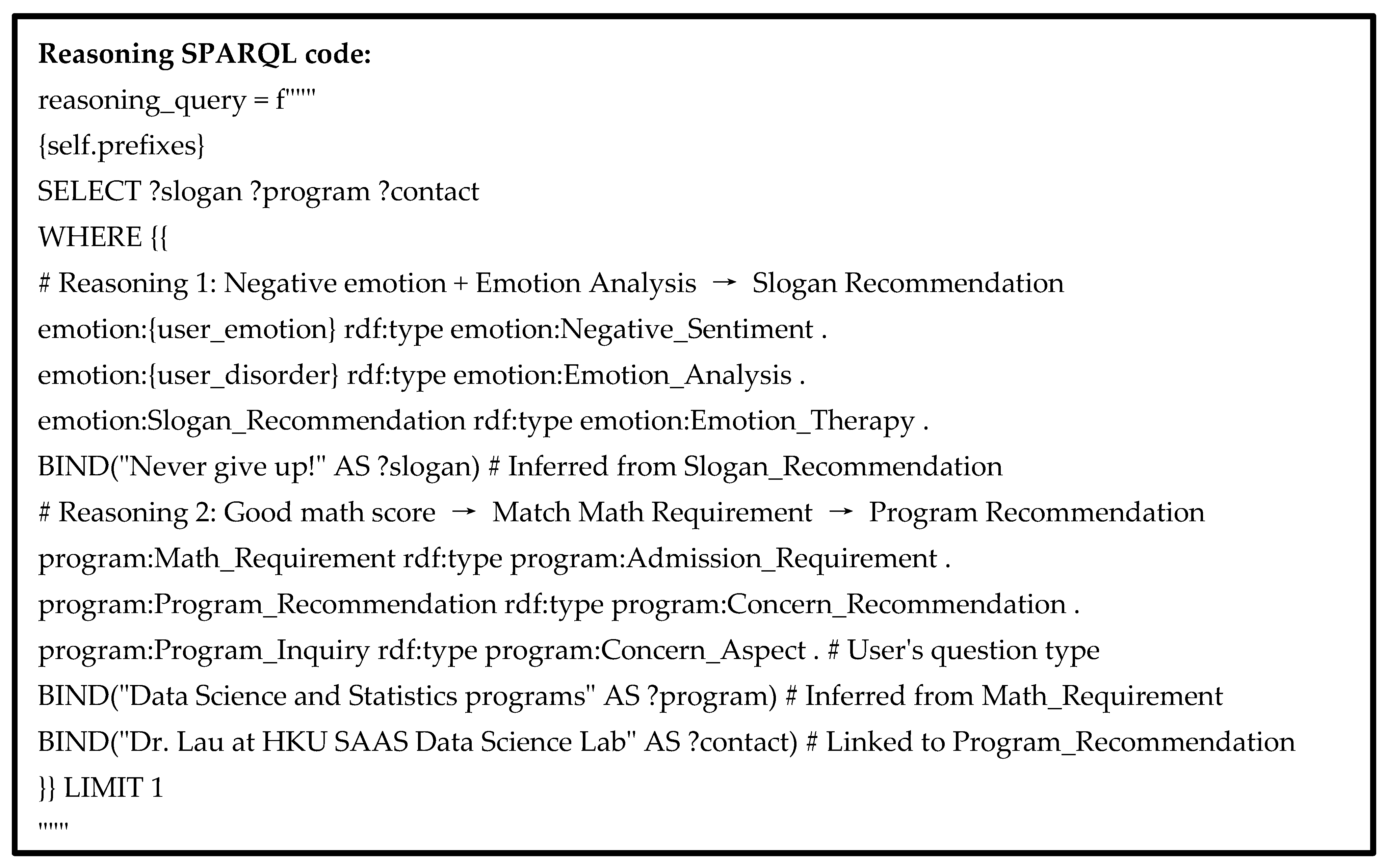

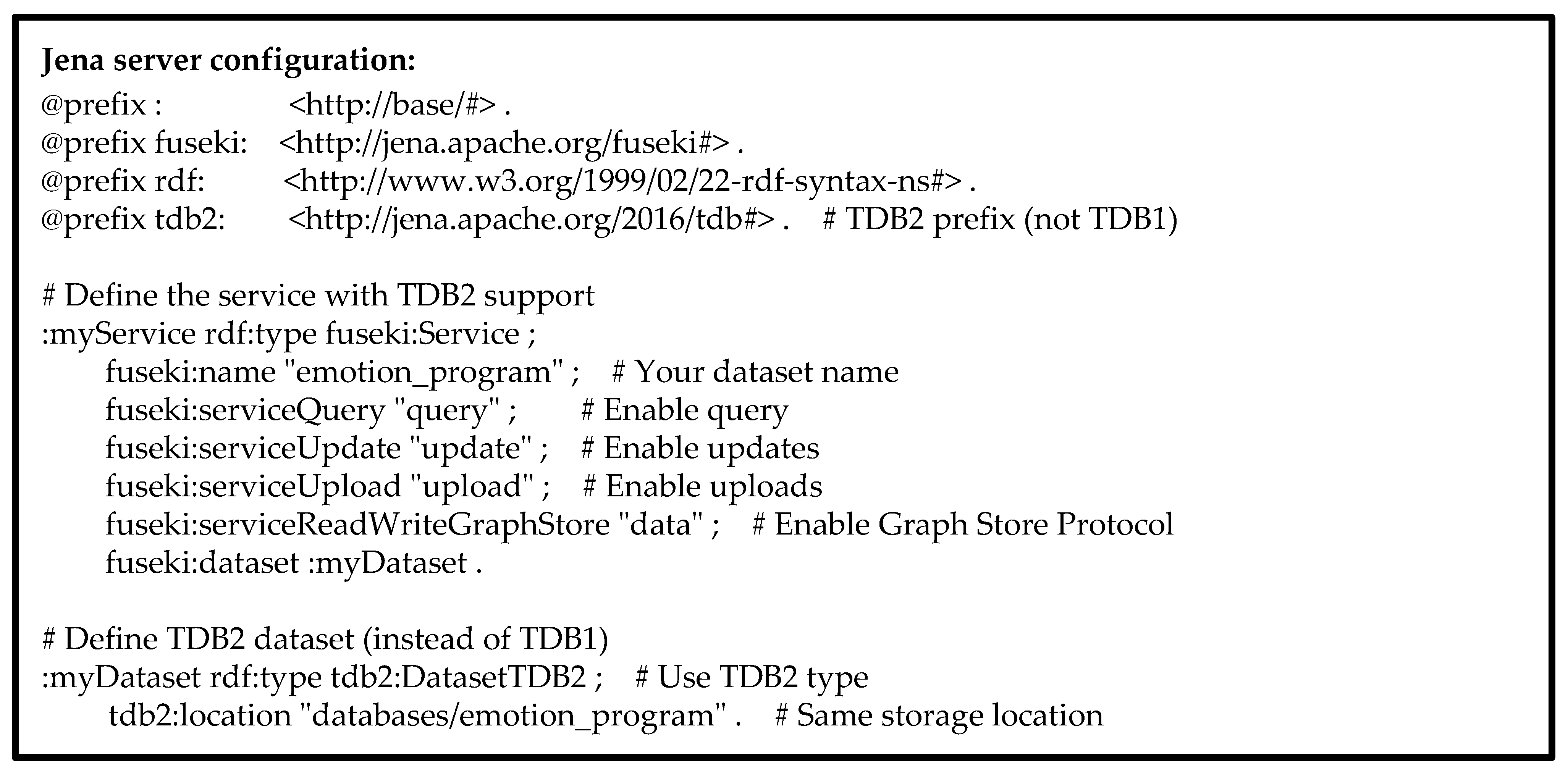

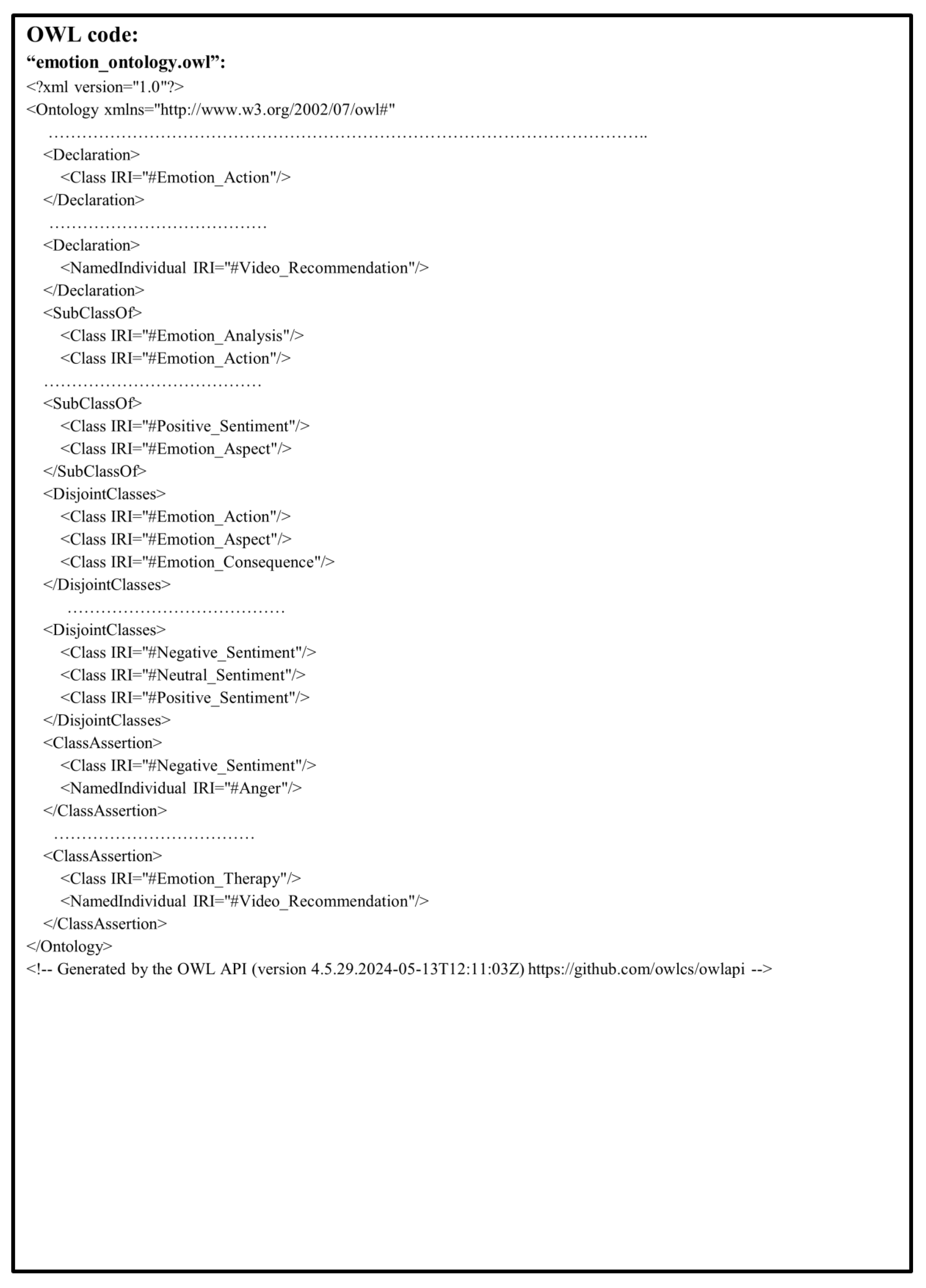

5. Using an Emotion Ontology for Intelligent Responses

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Franzoni, V.; Milani, A.; Nardi, D.; Vallverdú, J. Emotional machines: The next revolution. Web Intell. 2019, 17, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, M.E.; Kamel, M.S.; Karray, F. Survey on speech emotion recognition: Features, classification schemes, and databases. Pattern Recognit. 2011, 44, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowie, R.; Douglas-Cowie, E.; Tsapatsoulis, N.; Votsis, G.; Kollias, S.; Fellenz, W.; Taylor, J.G. Emotion recognition in human-computer interaction. IEEE Signal Process. Manag. 2001, 18, 32–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, J.; Pedrini, H. Bimodal Emotion Recognition Based on Audio and Facial Parts Using Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the 18th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Boca Raton, FL, USA, 16–19 December 2019; pp. 111–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morningstar, M.; Nelson, E.E.; Dirks, M.A. Maturation of vocal emotion recognition: Insights from the developmental and neuroimaging literature. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 90, 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luna-Jiménez, C.; Griol, D.; Callejas, Z.; Kleinlein, R.; Montero, J.M.; Fernández-Martínez, F. Multimodal Emotion Recognition on RAVDESS Dataset Using Transfer Learning. Sensors 2021, 21, 7665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siriwardhana, S.; Kaluarachchi, T.; Billinghurst, M.; Nanayakkara, S. Multimodal Emotion Recognition with Transformer-Based Self Supervised Feature Fusion. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 176274–176285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornejo, J.Y.R.; Pedrini, H. Audio-Visual Emotion Recognition Using a Hybrid Deep Convolutional Neural Network based on Census Transform. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (SMC), Bari, Italy, 6–9 October 2019; pp. 3396–3402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middya, A.I.; Nag, B.; Roy, S. Deep learning based multimodal emotion recognition using model-level fusion of audio–visual modalities. Knowl. Based Syst. 2022, 244, 108580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, M.; Cao, W.-H.; Liu, Z.-T.; Wu, M.; Xiao, P. Visual-audio emotion recognition based on multi-task and ensemble learning with multiple features. Neurocomputing 2020, 391, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.M.; Kim, J.K.; Kim, J.Y. Multi-Detection-Based Speech Emotion Recognition Using Autoencoder in Mobility Service Environment. Electronics 2025, 14, 1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramyasree, K.; Kumar, C.S. Expression Recognition Survey Through Multi-Modal Data Analytics. International. J. Comput. Sci. Netw. Secur. 2022, 22, 600–610. Available online: http://paper.ijcsns.org/07_book/202206/20220674.pdf (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Andayan, F.; Lau, B.T.; Tsun, M.T.; Chua, C. Hybrid LSTM-Transformer Model for Emotion Recognition from Speech Audio Files. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 36018–36027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhalehpour, S.; Onder, O.; Akhtar, Z.; Erdem, C.E. BAUM-1: A Spontaneous Audio-Visual Face Database of Affective and Mental States. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2016, 8, 300–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Guan, L. Recognizing Human Emotional State From Audiovisual Signals. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2008, 10, 936–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, M.; Soleymani, M. A Pre-Trained Audio-Visual Transformer for Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Virtual, 7–13 May 2022; pp. 4698–4702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Yu, Y.; Kim, G.; Breuel, T.; Kautz, J.; Song, Y. Parameter Efficient Multimodal Transformers for Video Representation Learning. arXiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrusaitis, T.; Mahmoud, M.; Robinson, P. Cross-dataset learning and person-specific normalisation for automatic Action Unit detection. In Proceedings of the 11th IEEE International Conference and Workshops on Automatic Face and Gesture Recognition (FG), Ljubljana, Slovenia, 4–8 May 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagheri, E.; Esteban, P.G.; Cao, H.-L.; De Beir, A.; Lefeber, D.; Vanderborght, B. An Autonomous Cognitive Empathy Model Responsive to Users’ Facial Emotion Expressions. ACM Trans. Interact. Intell. Syst. 2020, 10, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekman, P. Basic Emotions. In Handbook of Cognition and Emotion; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2005; pp. 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posner, J.; Russell, J.A.; Peterson, B.S. The circumplex model of affect: An integrative approach to affective neuroscience, cognitive development, and psychopathology. Dev. Psychopathol. 2005, 17, 715–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šumak, B.; Brdnik, S.; Pušnik, M. Sensors and Artificial Intelligence Methods and Algorithms for Human–Computer Intelligent Interaction: A Systematic Mapping Study. Sensors 2022, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, S.; Huang, T.; Gao, W. Speech Emotion Recognition Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network and Discriminant Temporal Pyramid Matching. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2018, 20, 1576–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Liang, R.; Liang, Z.; Huang, C.; Zou, C.; Schuller, B. Speech Emotion Classification Using Attention-Based LSTM. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2019, 27, 1675–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Arunachalam, S.; Balakrishnan, R. Deep self-attention network for facial emotion recognition. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 171, 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Liu, G.; Liu, Q.; Deng, J. Spatio-temporal convolutional features with nested LSTM for facial expression recognition. Neurocomputing 2018, 317, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norhikmah; Lutfhi, A.; Rumini. The Effect of Layer Batch Normalization and Droupout of CNN model Performance on Facial Expression Classification. JOIV Int. J. Inform. Vis. 2022, 6, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkawaz, M.H.; Mohamad, D.; Basori, A.H.; Saba, T. Blend Shape Interpolation and FACS for Realistic Avatar. 3D Res. 2015, 6, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aouani, H.; Ayed, Y.B. Speech emotion recognition with deep learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2020, 176, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yin, Z.; Chen, P.; Nichele, S. Emotion recognition using multi-modal data and machine learning techniques: A tutorial and review. Inf. Fusion 2020, 59, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A. Communication Without Words. In Communication Theory, 2nd ed.; Routledge Press: Oxfordshire, UK, 2017; Chapter 2; pp. 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzirakis, P.; Trigeorgis, G.; Nicolaou, M.A.; Schuller, B.W.; Zafeiriou, S. End-to-End Multimodal Emotion Recognition Using Deep Neural Networks. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Signal Process. 2017, 11, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mocanu, B.; Tapu, R. Audio-Video Fusion with Double Attention for Multimodal Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE 14th Image, Video, and Multidimensional Signal Processing Workshop (IVMSP), Nafplio, Greece, 26–29 June 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baltrusaitis, T.; Zadeh, A.; Lim, Y.C.; Morency, L.P. OpenFace 2.0: Facial Behavior Analysis Toolkit. In Proceedings of the 13th IEEE International Conference on Automatic Face & Gesture Recognition, Xi’an, China, 15–19 May 2018; pp. 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Tao, J.; Liu, B.; Lian, Z.; Niu, M. Multimodal Transformer Fusion for Continuous Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 3507–3511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khorram, S.; Aldeneh, Z.; Dimitriadis, D.; McInnis, M.; Provost, E.M. Capturing Long-term Temporal Dependencies with Convolutional Networks for Continuous Emotion Recognition. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lau, A. Implementation of an onto-wiki toolkit using web services to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of medical ontology co-authoring and analysis. Inform. Health Soc. Care 2009, 34, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsui, E.; Wang, W.M.; Cheung, C.F.; Lau, A. A Concept-Relationship Acquisition and Inference Approach for Hierarchical Taxonomy Construction from Tags. Inf. Process. Manag. 2010, 46, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.; Tse, S. Development of the Ontology Using a Problem-Driven Approach: In the Context of Traditional Chinese medicine Diagnosis. Int. J. Knowl. Eng. Data Min. 2010, 1, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, A.; Tsui, E.; Lee, W.B. An Ontology-based Similarity Measurement for Problem-based Case Reasoning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 43, 6547–6579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Chen, G.; Yu, H.; Bao, Y.; Zhao, L. Speech emotion recognition under white noise. Arch. Acoust. 2013, 38, 457–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Al-onazi, B.B.; Nauman, M.A.; Jahangir, R.; Malik, M.M.; Alkhammash, E.H.; Elshewey, A.M. Transformer-Based Multilingual Speech Emotion Recognition Using Data Augmentation and Feature Fusion. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFee, B.; Raffel, C.; Liang, D.; Ellis, D.P.W.; McVicar, M.; Battenbergk, E.; Nieto, O. Librosa: Audio and Music Signal Analysis in Python. 2015. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MhOdbtPhbLU (accessed on 26 October 2025).

- Wang CRen, Y.; Zhang, N.; Cui, F.; Luo, S. Speech Emotion Recognition Based on Multi-feature and Multi-lingual Fusion. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 4897–4907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, X.; Huang, L.; Li, F.; Duan, S.; Sun, Y. Speech Emotion Recognition Using a Dual-Channel Complementary Spectrogram and the CNN-SSAE Neutral Network. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingstone, S.R.; Russo, F.A. The Ryerson Audio-Visual Database of Emotional Speech and Song (RAVDESS): A dynamic, multimodal set of facial and vocal expressions in North American English. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0196391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haq, S.; Jackson, P.J.B. Speaker-Dependent Audio-Visual Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Audio-Visual Speech Processing, Norwich, UK, 10–13 September 2009; pp. 53–58. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358647534_Speaker-Dependent_Audio-Visual_Emotion_Recognition (accessed on 1 March 2023).

- Seo, M.; Kim, M. Fusing Visual Attention CNN and Bag of Visual Words for Cross-Corpus Speech Emotion Recognition. Sensors 2020, 20, 5559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, R.; Puri, H.; Aggarwal, N.; Gupta, V. An Efficient Language-Independent Acoustic Emotion Classification System. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2020, 45, 3111–3121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Hussain, F.; Baloch, N.K.; Raja, F.R.; Yu, H.; Zikria, B.Y. Impact of Feature Selection Algorithm on Speech Emotion Recognition Using Deep Convolutional Neural Network. Sensors 2020, 20, 6008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansouri-Benssassi, E.; Ye, J. Speech Emotion Recognition With Early Visual Cross-modal Enhancement Using Spiking Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Budapest, Hungary, 14–19 July 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghaleb, E.; Popa, M.; Asteriadis, S. Multimodal and Temporal Perception of Audio-visual Cues for Emotion Recognition. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Affective Computing and Intelligent Interaction (ACII), Cambridge, UK, 3–6 September 2019; pp. 552–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avots, E.; Sapiński, T.; Bachmann, M.; Kamińska, D. Audiovisual emotion recognition in wild. Mach. Vis. Appl. 2019, 30, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahdari, F.; Rashedi, E.; Eftekhari, M. A Multimodal Emotion Recognition System Using Facial Landmark Analysis. Iran. J. Sci. Technol. Trans. Electr. Eng. 2019, 43, 171–189. [Google Scholar]

- Achilleos, G.; Limniotis, K.; Kolokotroni, N. Exploring Personal Data Processing in Video Conferencing Apps. Electronics 2023, 12, 1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.; Marinheiro, C.; Mateus, C.; Rodrigues, P.P.; Rodrigues, M.A.; Rocha, N. Overcoming Challenges in Video-Based Health Monitoring: Real-World Implementation, Ethics, and Data Considerations. Sensors 2025, 25, 1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barker, D.; Tippireddy, M.K.R.; Farhan, A. Ethical Considerations in Emotion Recognition Research. Psychol. Int. 2025, 7, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitwi, A.; Chen Yu Zhu, S.; Blasch, E.; Chen, G. Privacy-Preserving Surveillance as an Edge Service Based on Lightweight Video Protection Schemes Using Face De-Identification and Window Masking. Electronics 2021, 10, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Cilloni, T.; Walter, C.; Fleming, C. Multi-Scale, Class-Generic, Privacy-Preserving Video. Electronics 2021, 10, 1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, D.; Hao, D.; Lu, J.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, J. A Visually Meaningful Color-Video Encryption Scheme That Combines Frame Channel Fusion and a Chaotic System. Electronics 2024, 13, 2376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Feature Name | Description |

|---|---|

| flatness | A measure to quantify how noise-like a sound is, as opposed to being tone-like. |

| zerocr | The rate at which a signal changes from positive to zero to negative or vice versa. |

| meanMagnitude | The mean of the magnitude of the spectrogram. |

| maxMagnitude | The maximum magnitude of the spectrogram. |

| stdMagnitude | The standard deviation of the magnitude of the spectrogram. |

| meancent | The mean of the spectral centroid, which indicates the location of the center of mass of the spectrum. |

| maxcent | The maximum spectral centroid. |

| stdcent | The standard deviation of the spectral centroid. |

| pitchmean | The mean of the pitch, which is the interpolated frequency estimate of a particular harmonic. |

| pitchmax | The maximum pitch. |

| pitchmin | The minimum pitch. |

| pitchstd | The standard deviation of the pitch. |

| pitch_tuning_offset | The tuning offset (in fractions of a bin) relative to 440.0 Hz. |

| meanrms | The mean of the root-mean-square (RMS) energy. |

| maxrms | The maximum root-mean-square (RMS) energy. |

| stdrms | The standard deviation of the root-mean-square (RMS) energy. |

| mfccs | The mean of MFCCs, which are derived from a cepstral representation of the audio speeches. |

| mfccmax | The maximum MFCC. |

| mfccsstd | The standard deviation of MFCCs. |

| chroma | Chroma represents the tonal content of a musical audio signal in a condensed form. |

| mel_mean | The mean of the Mel spectrogram. |

| contrast | Contrast is the difference between instrument sounds. |

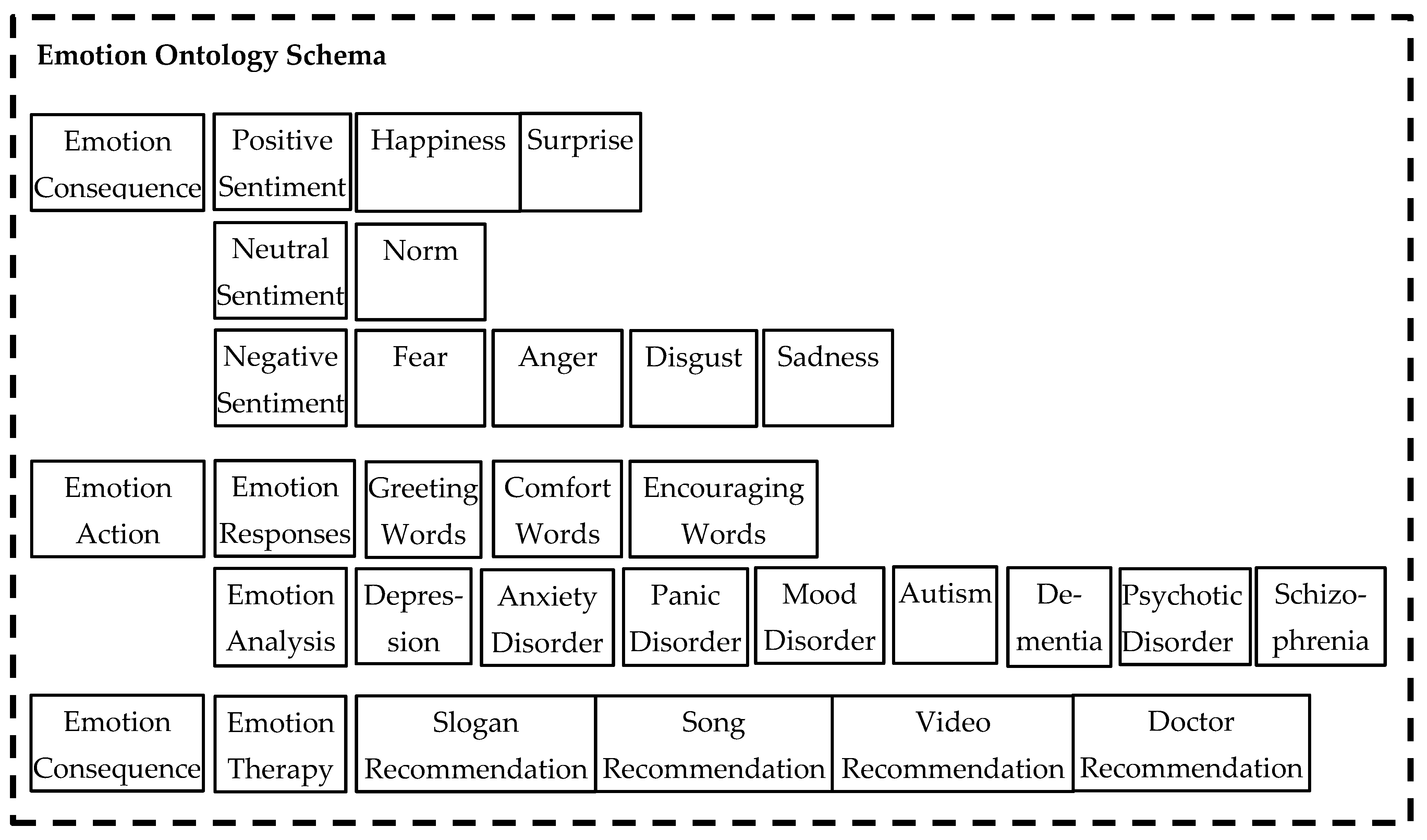

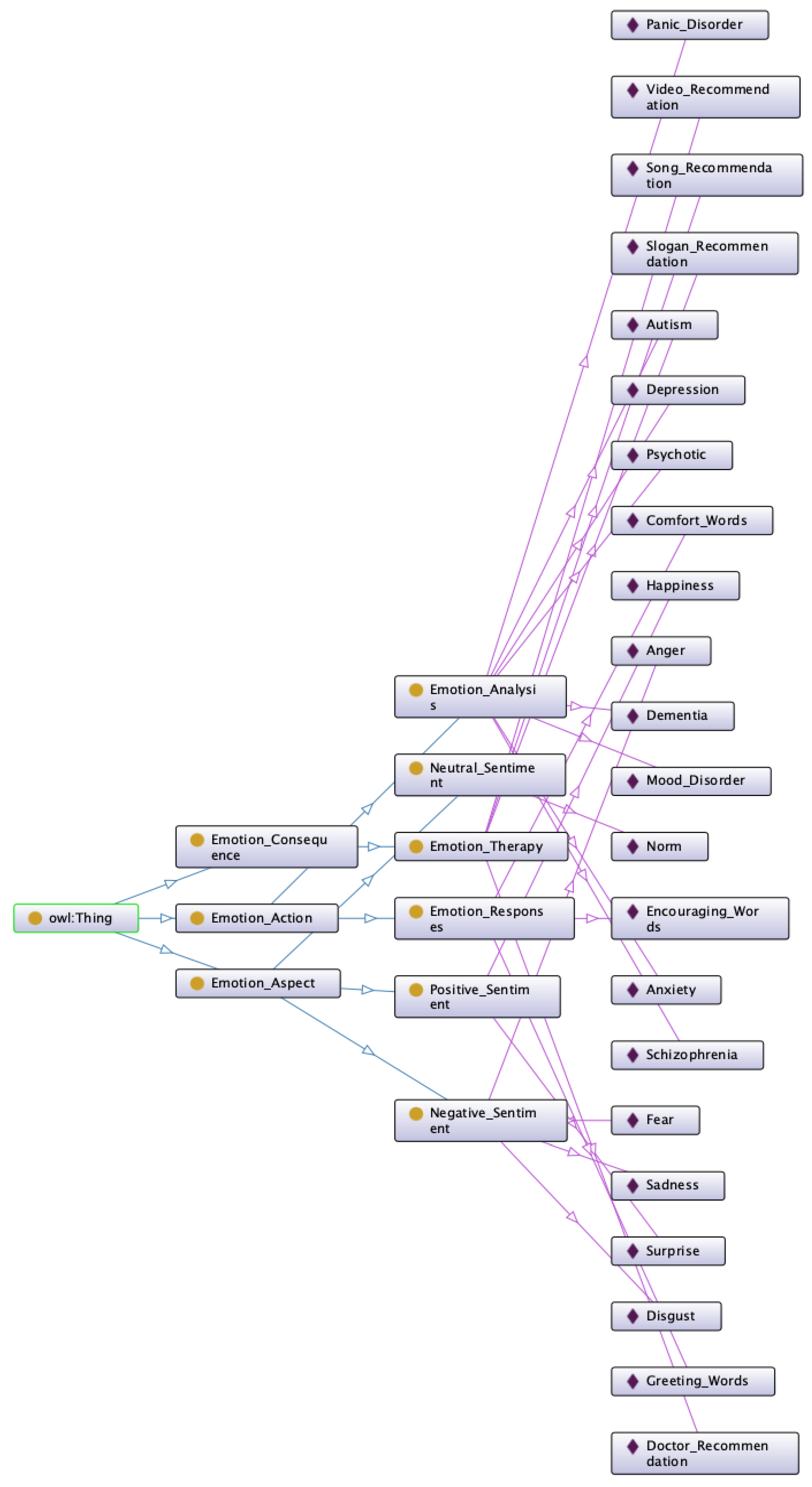

| Step 1: Construct the Components of the Emotion Aspect in the Emotion Ontology. | It contains a Positive Sentiment Entity, a Negative Sentiment Entity, and a Neutral Sentiment Entity. |

| The attributes of the positive sentiment entity. | Happiness, surprise. |

| The attributes of the neutral sentiment entity. | Neutrality. |

| The attributes of the negative sentiment entity. | Anger, fear, sadness, disgust. |

| Step 2: Construct the components of the emotion action in the emotion ontology. | It contains the emotion response entity and the emotion analysis entity. |

| The attributes of the emotion response entity. | Greeting words, comfort words, encouraging words, etc. |

| The attributes of the emotion analysis entity. | Depression, anxiety disorders, panic disorders, mood disorders, autism, dementia, psychotic disorders, schizophrenia, etc. |

| Step 3: Construct the components of the emotion consequence in the emotion ontology. | It contains an emotion therapy entity. |

| The attributes of the emotion therapy entity. | Slogan recommendation, song recommendation, video recommendation, and doctor recommendation. |

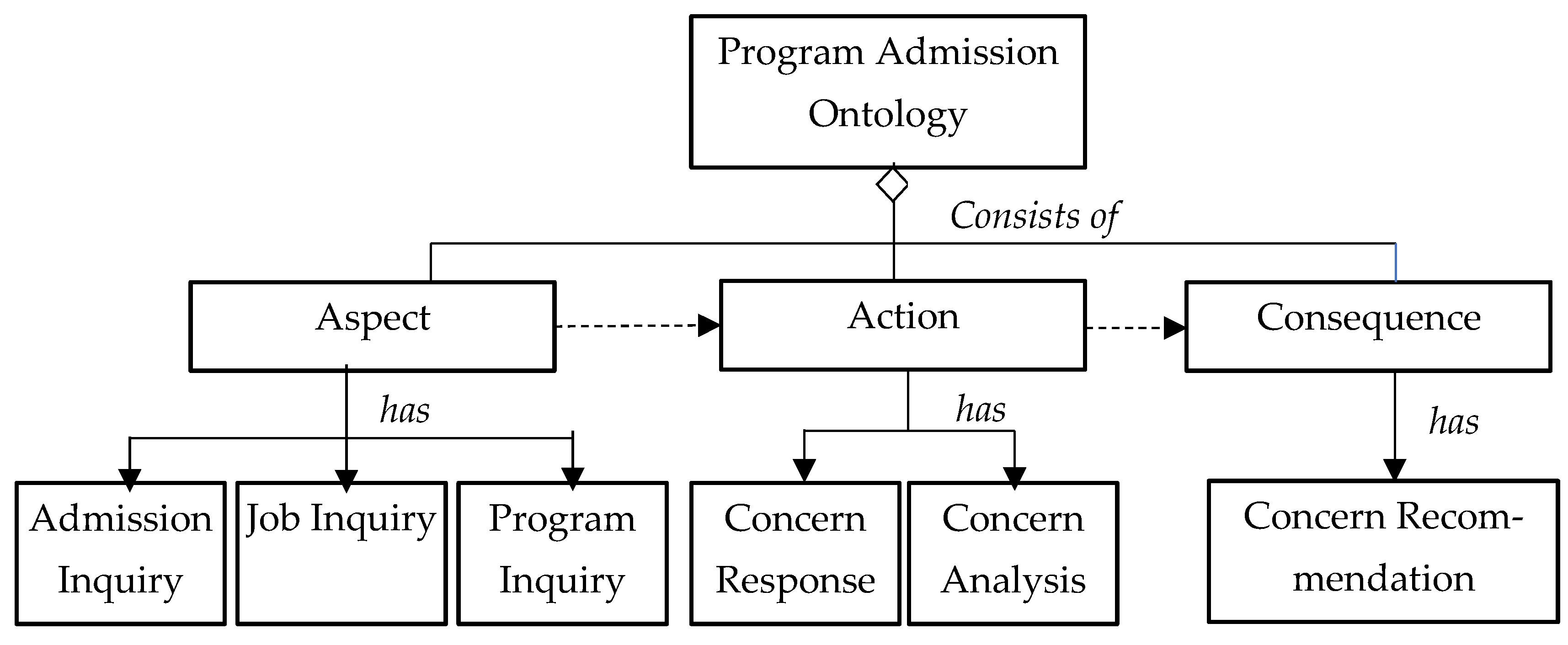

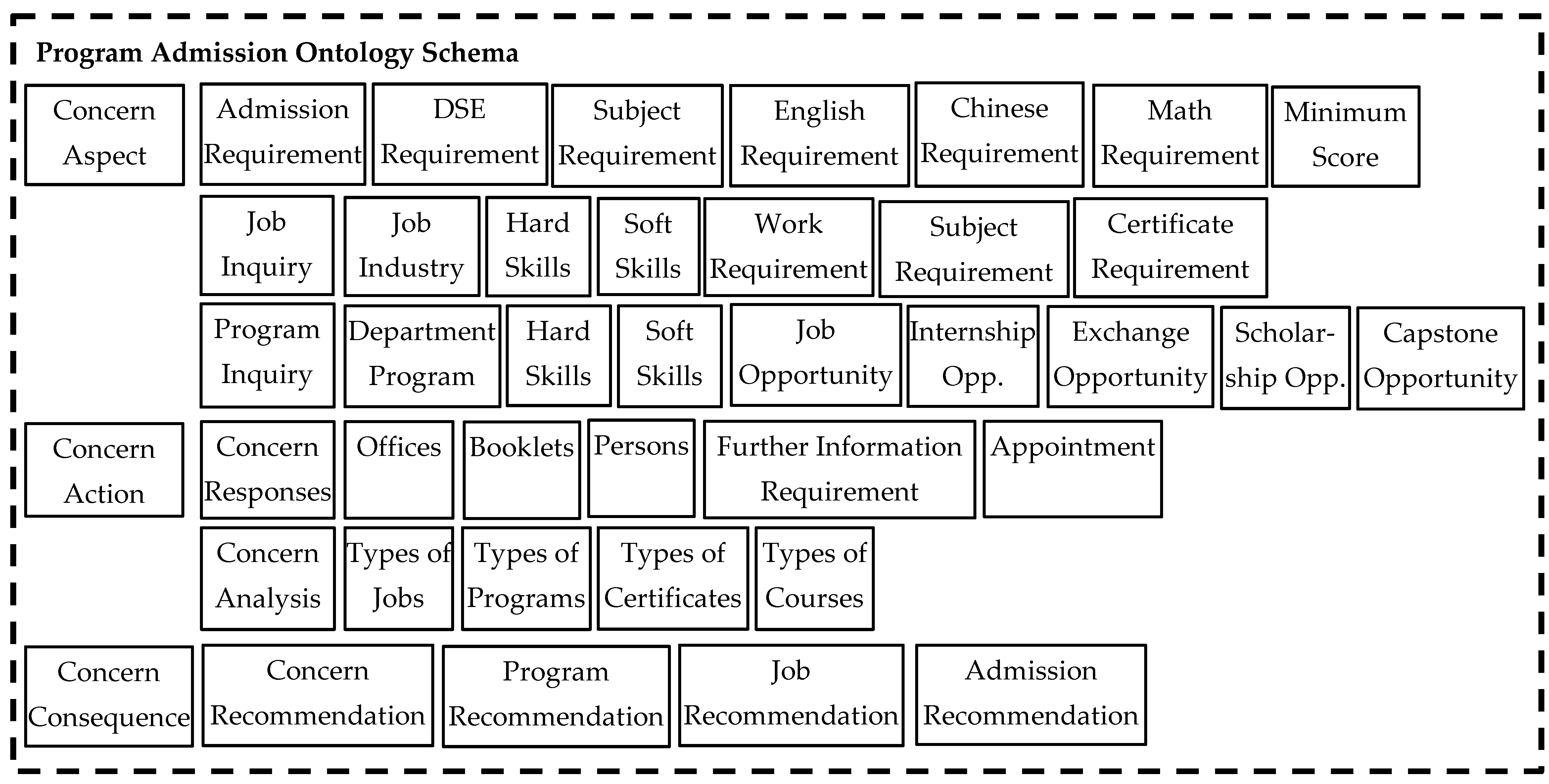

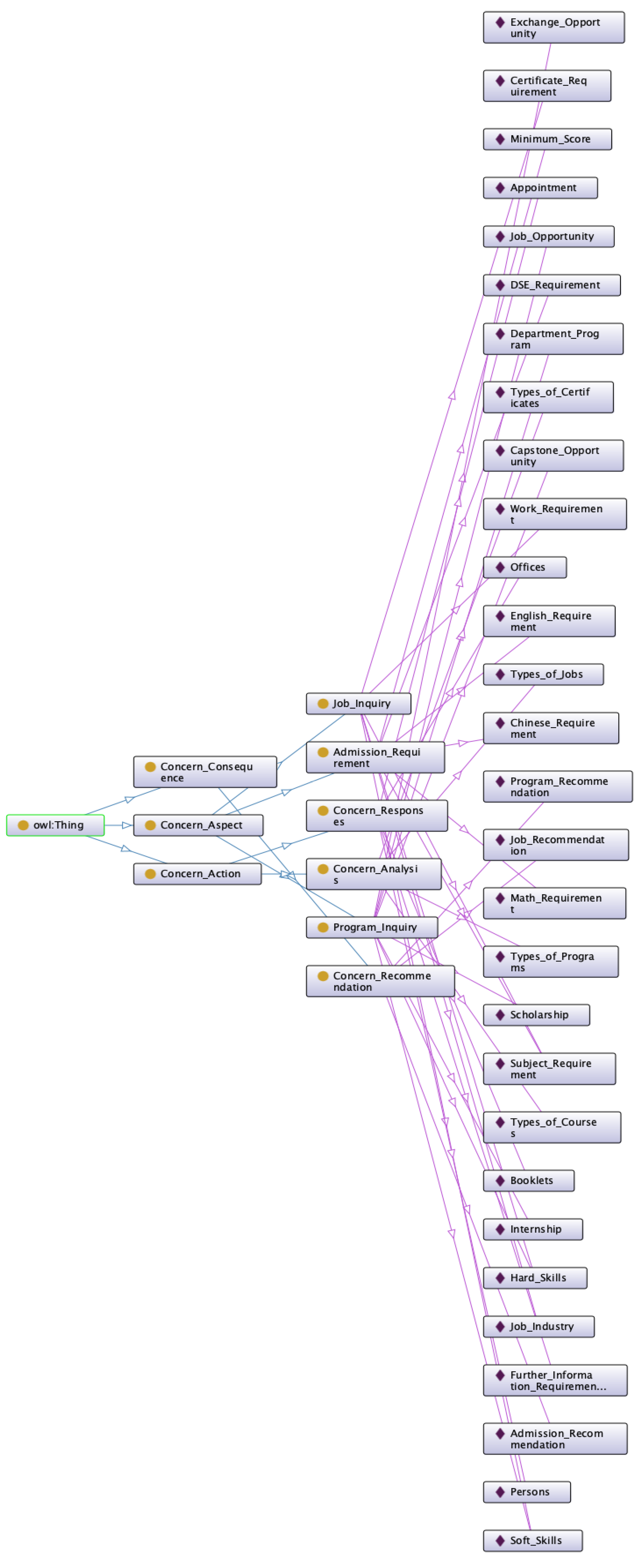

| Step 1: Construct the Components of the Concern Aspect in the Program Admission Ontology. | It contains the Admission Requirement Inquiry Entity, the Job Inquiry Entity, and the Program Inquiry Entity. |

| The attributes of the admission requirement inquiry entity. | DSE results, subjects to be taken, English score, Chinese score, math score, minimal score, etc. |

| The attributes of the job inquiry entity. | Job industry, required hard and soft skills, working experience, subjects taken, certificates, etc. |

| The attributes of the program inquiry entity. | Program’s department, required hard and soft skills, job opportunities, internship opportunities, exchange opportunities, scholarship opportunities, capstone opportunities, etc. |

| Step 2: Construct the components of the concern action in the program admission ontology. | It contains the concern response entity and the concern analysis entity. |

| The attributes of the concern response entity. | Offices, booklets, persons, further information requirements, appointments, etc. |

| The attributes of the concern analysis entity. | Types of jobs, types of progress, types of certificates, types of courses, etc. |

| Step 3: Construct the components of the concern consequence in the program admission ontology. | It contains the concern recommendation entity. |

| The attributes of the concern recommendation entity. | Program recommendation, job recommendation, admission recommendation, etc. |

| Audio-Only | Video-Only | Audiovisual | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hidden layers | 2 | 3 | 2 |

| Hidden neurons | 1024 | 256 | 128 |

| Epochs | 500 | 500 | 250 |

| Batch size | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| Learning rate | 0.001 | 1 × 10−5 | 0.001 |

| Weight decay | 1 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−5 | 1 × 10−5 |

| Dropout rate | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 |

| SAVEE | RAVDESS | RML | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SER | 83.33% | 81.25% | 75% |

| FER | 90.62% | 75.69% | 86.11% |

| Audiovisual | 92.71% | 86.46% | 91.67% |

| Dataset | Literature | Year | Model | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAVEE | Seo et al. [48] | 2020 | VACNN | 75.00 |

| Singh et al. [49] | 2020 | RNN | 77.38 | |

| Farooq et al. [50] | 2020 | DCNN + CFS + SVM | 82.10 | |

| Li et al. [45] | 2022 | CNN + SSAE | 88.96 | |

| - | - | Our Method | 92.71 | |

| RAVDESS | Mansouri-Benssassi et al. [51] | 2019 | SNN + MFCC | 86.30 |

| Singh et al. [49] | 2020 | RNN | 64.15 | |

| Ghaleb et al. [52] | 2020 | KNN + LSTM | 67.70 | |

| Farooq et al. [50] | 2020 | DCNN + CFS + SVM | 81.30 | |

| Middya et al. [9] | 2022 | ConvLSTM2D + 1D CNN | 86.00 | |

| - | - | Our Method | 86.46 | |

| RML | Avots et al. [53] | 2018 | SVM + AlexNet | 60.20 |

| Rahdari et al. [54] | 2019 | NB + FRNN + SMO + BG + RF | 73.12 | |

| Li et al. [45] | 2022 | CNN + SSAE | 83.18 | |

| - | - | Our Method | 91.67 |

| SAVEE-SER | SAVEE-FER | SAVEE Audio-Visual | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

| Happiness | 0.786 | 0.917 | 0.846 | 0.846 | 0.917 | 0.880 | 0.857 | 1.000 | 0.923 |

| Sadness | 0.833 | 0.417 | 0.556 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.833 | 0.833 | 0.833 |

| Anger | 0.900 | 0.750 | 0.818 | 0.846 | 0.917 | 0.880 | 1.000 | 0.917 | 0.957 |

| Fear | 0.615 | 0.667 | 0.640 | 0.818 | 0.750 | 0.783 | 0.818 | 0.750 | 0.783 |

| Disgust | 0.706 | 1.000 | 0.828 | 1.000 | 0.833 | 0.909 | 1.000 | 0.917 | 0.957 |

| Surprise | 0.818 | 0.750 | 0.783 | 0.846 | 0.917 | 0.880 | 0.733 | 0.917 | 0.815 |

| Norm | 0.840 | 0.875 | 0.857 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.955 | 0.875 | 0.913 |

| RAVDESS-SER | RAVDESS-FER | RAVDESS Audio-Visual | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

| Happiness | 0.923 | 0.615 | 0.738 | 0.881 | 0.949 | 0.914 | 0.929 | 1.000 | 0.963 |

| Sadness | 0.659 | 0.763 | 0.707 | 0.583 | 0.553 | 0.568 | 0.769 | 0.789 | 0.779 |

| Anger | 0.850 | 0.872 | 0.861 | 0.757 | 0.718 | 0.737 | 0.844 | 0.974 | 0.905 |

| Fear | 0.800 | 0.737 | 0.767 | 0.622 | 0.605 | 0.613 | 0.900 | 0.711 | 0.794 |

| Disgust | 0.804 | 0.949 | 0.871 | 0.829 | 0.872 | 0.850 | 0.900 | 0.923 | 0.911 |

| Surprise | 0.829 | 0.763 | 0.795 | 0.667 | 0.632 | 0.649 | 0.744 | 0.763 | 0.753 |

| Norm | 0.500 | 0.684 | 0.578 | 0.696 | 0.842 | 0.762 | 0.778 | 0.737 | 0.757 |

| Calm | 0.917 | 0.868 | 0.892 | 0.833 | 0.789 | 0.811 | 0.914 | 0.842 | 0.877 |

| RML-SER | RML-FER | RML Audio-Visual | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Precision | Recall | F1-Score |

| Happiness | 0.731 | 0.792 | 0.760 | 0.920 | 0.958 | 0.939 | 0.821 | 0.958 | 0.885 |

| Sadness | 0.750 | 0.625 | 0.682 | 0.792 | 0.792 | 0.792 | 0.680 | 0.708 | 0.694 |

| Anger | 0.913 | 0.875 | 0.894 | 0.905 | 0.792 | 0.844 | 0.957 | 0.917 | 0.936 |

| Fear | 0.619 | 0.542 | 0.578 | 0.731 | 0.792 | 0.760 | 0.667 | 0.667 | 0.667 |

| Disgust | 0.618 | 0.875 | 0.724 | 0.840 | 0.875 | 0.857 | 0.864 | 0.792 | 0.826 |

| Surprise | 0.800 | 0.667 | 0.727 | 1.000 | 0.958 | 0.979 | 1.000 | 0.917 | 0.957 |

| All Datasets—SER | All Datasets—FER | All Datasets—Audio-Visual | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotion | Macro-Precision | Macro-Recall | Macro-F1 | Macro-Precision | Macro-Recall | Macro-F1 | Macro-Precision | Macro-Recall | Macro-F1 |

| Happiness | 0.813 | 0.775 | 0.782 | 0.882 | 0.941 | 0.911 | 0.869 | 0.986 | 0.924 |

| Sadness | 0.747 | 0.602 | 0.648 | 0.792 | 0.781 | 0.786 | 0.761 | 0.777 | 0.769 |

| Anger | 0.888 | 0.832 | 0.858 | 0.836 | 0.809 | 0.820 | 0.934 | 0.936 | 0.932 |

| Fear | 0.678 | 0.648 | 0.662 | 0.724 | 0.716 | 0.719 | 0.795 | 0.709 | 0.748 |

| Disgust | 0.709 | 0.941 | 0.807 | 0.890 | 0.860 | 0.872 | 0.921 | 0.877 | 0.898 |

| Surprise | 0.816 | 0.727 | 0.768 | 0.838 | 0.836 | 0.836 | 0.826 | 0.865 | 0.842 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, Y.; Cheung, L.; Ma, P.; Lee, H.; Lau, A.S.M. An Emotional AI Chatbot Using an Ontology and a Novel Audiovisual Emotion Transformer for Improving Nonverbal Communication. Electronics 2025, 14, 4304. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214304

Wang Y, Cheung L, Ma P, Lee H, Lau ASM. An Emotional AI Chatbot Using an Ontology and a Novel Audiovisual Emotion Transformer for Improving Nonverbal Communication. Electronics. 2025; 14(21):4304. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214304

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Yun, Liege Cheung, Patrick Ma, Herbert Lee, and Adela S.M. Lau. 2025. "An Emotional AI Chatbot Using an Ontology and a Novel Audiovisual Emotion Transformer for Improving Nonverbal Communication" Electronics 14, no. 21: 4304. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214304

APA StyleWang, Y., Cheung, L., Ma, P., Lee, H., & Lau, A. S. M. (2025). An Emotional AI Chatbot Using an Ontology and a Novel Audiovisual Emotion Transformer for Improving Nonverbal Communication. Electronics, 14(21), 4304. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214304