Electric-Field and Magnetic-Field Decoupled Wireless Power and Full-Duplex Signal Transfer Technology for Pre-Embedded Sensors

Abstract

1. Introduction

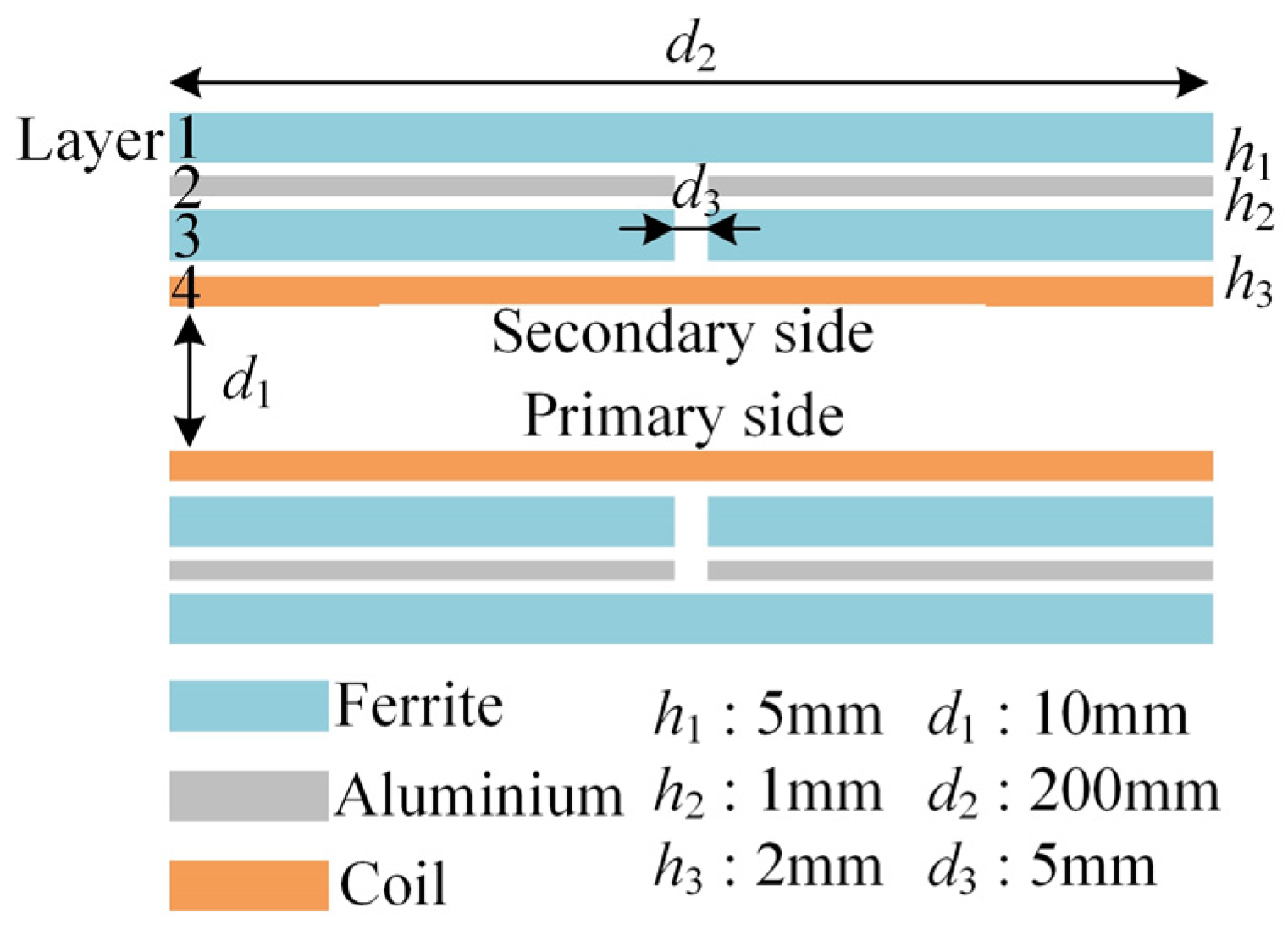

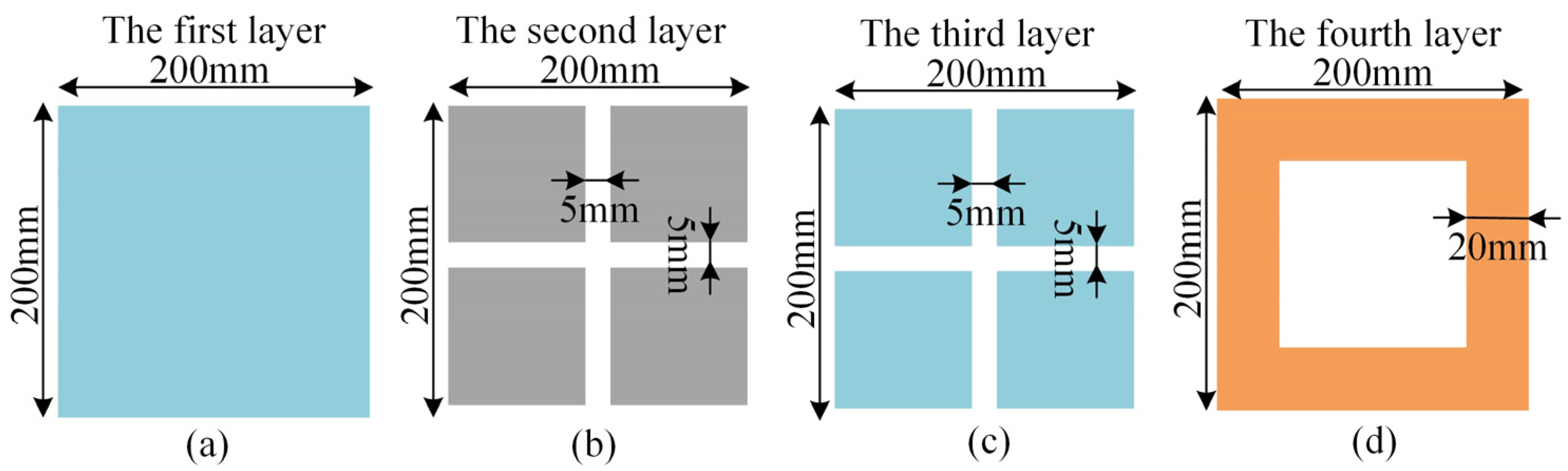

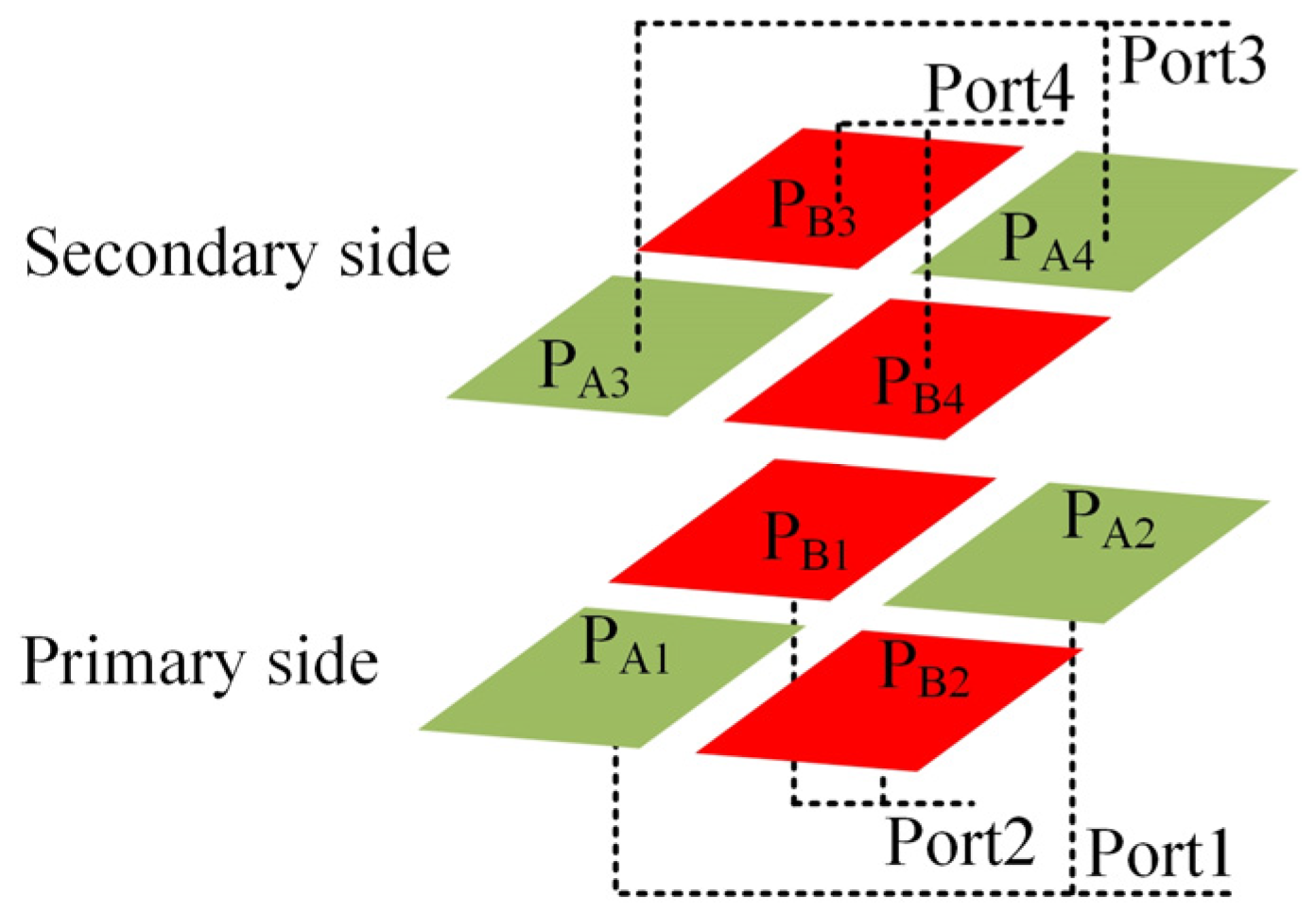

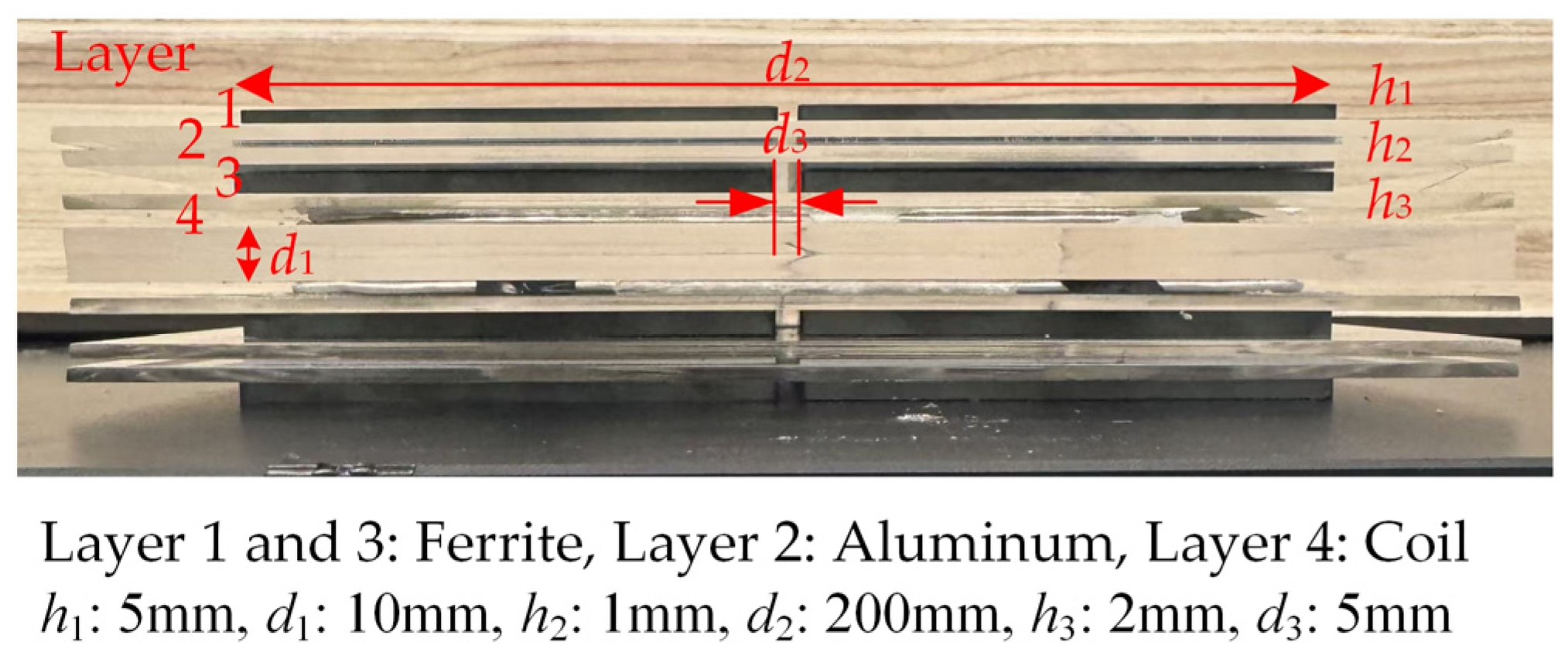

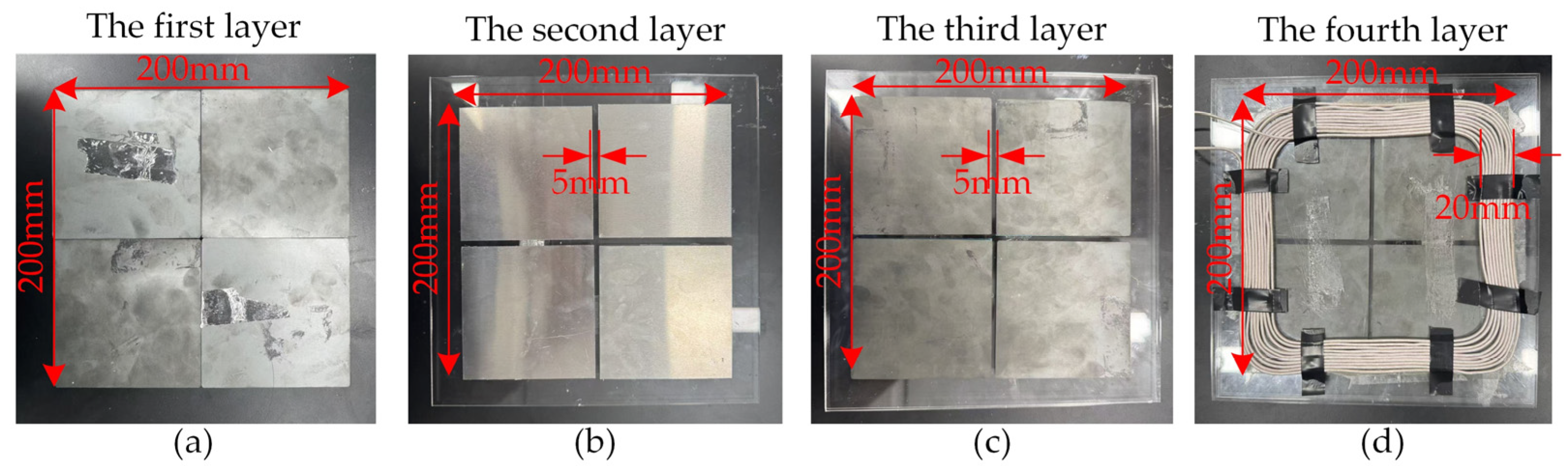

2. Design of Hybrid Electric–Magnetic Field Coupler

2.1. Coupler Structure Description

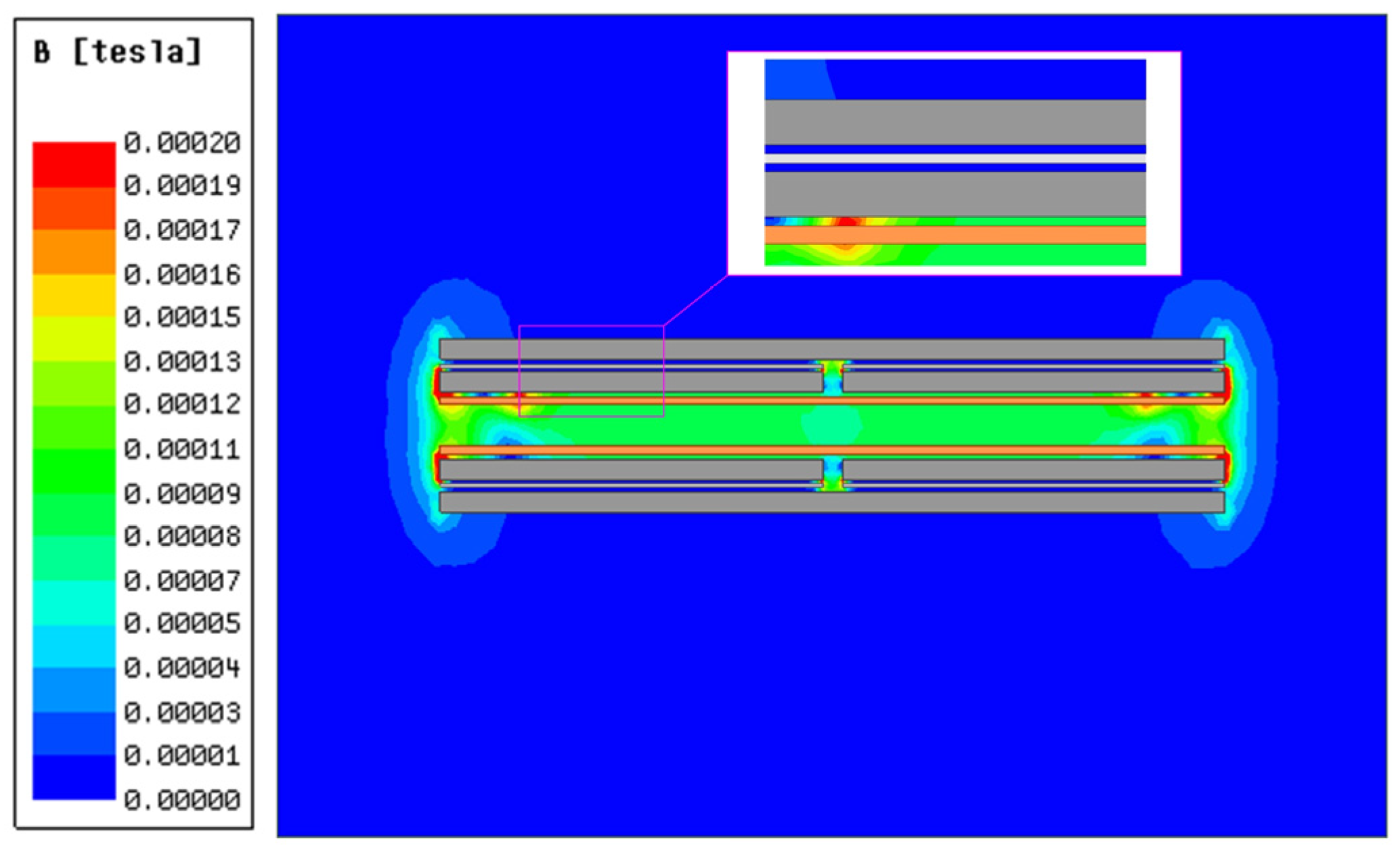

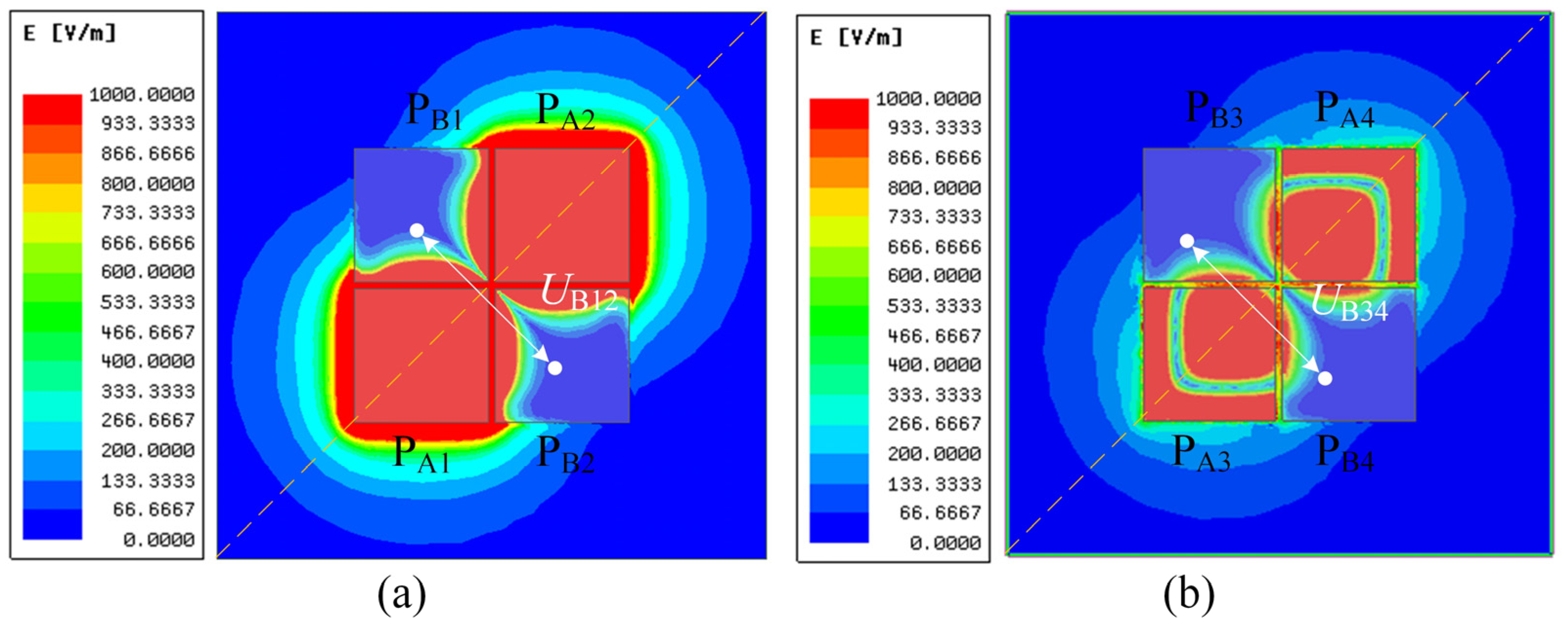

2.2. Finite Element Simulation of Coupler

3. System Modeling and Design

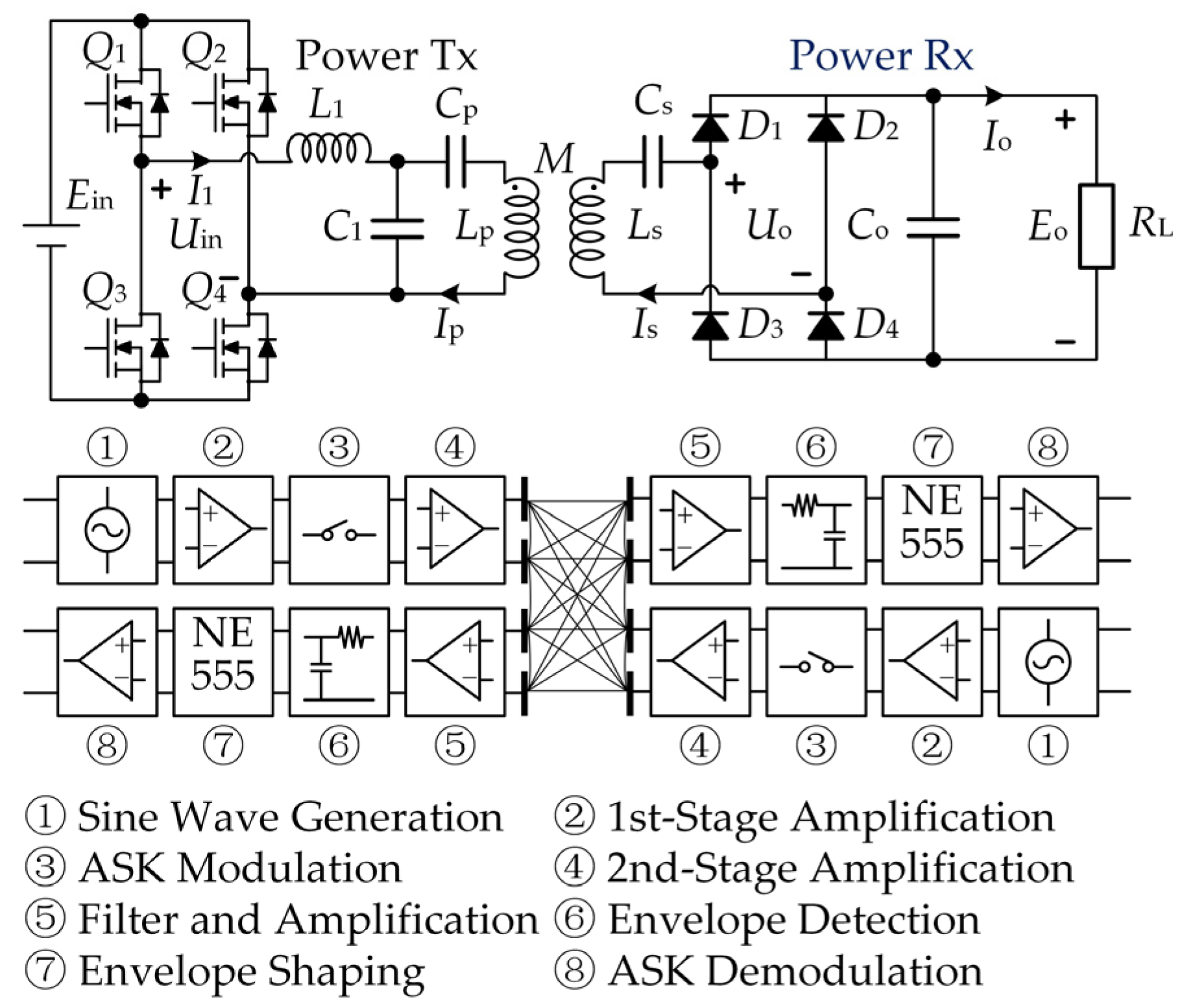

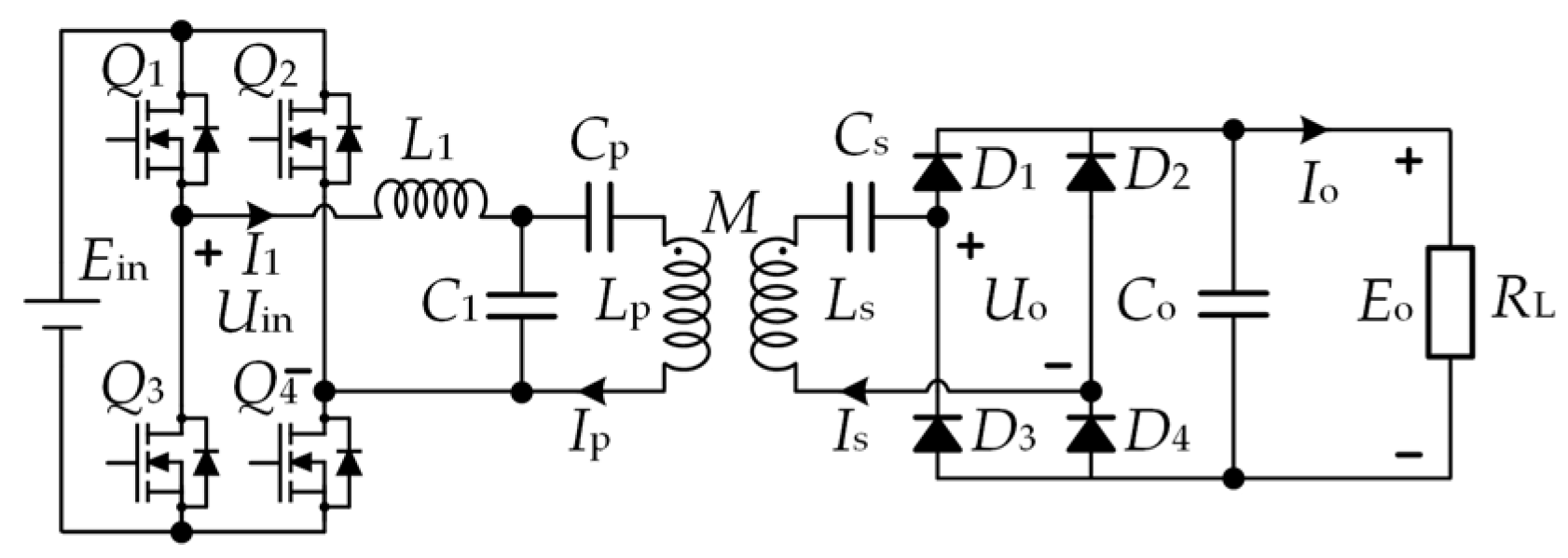

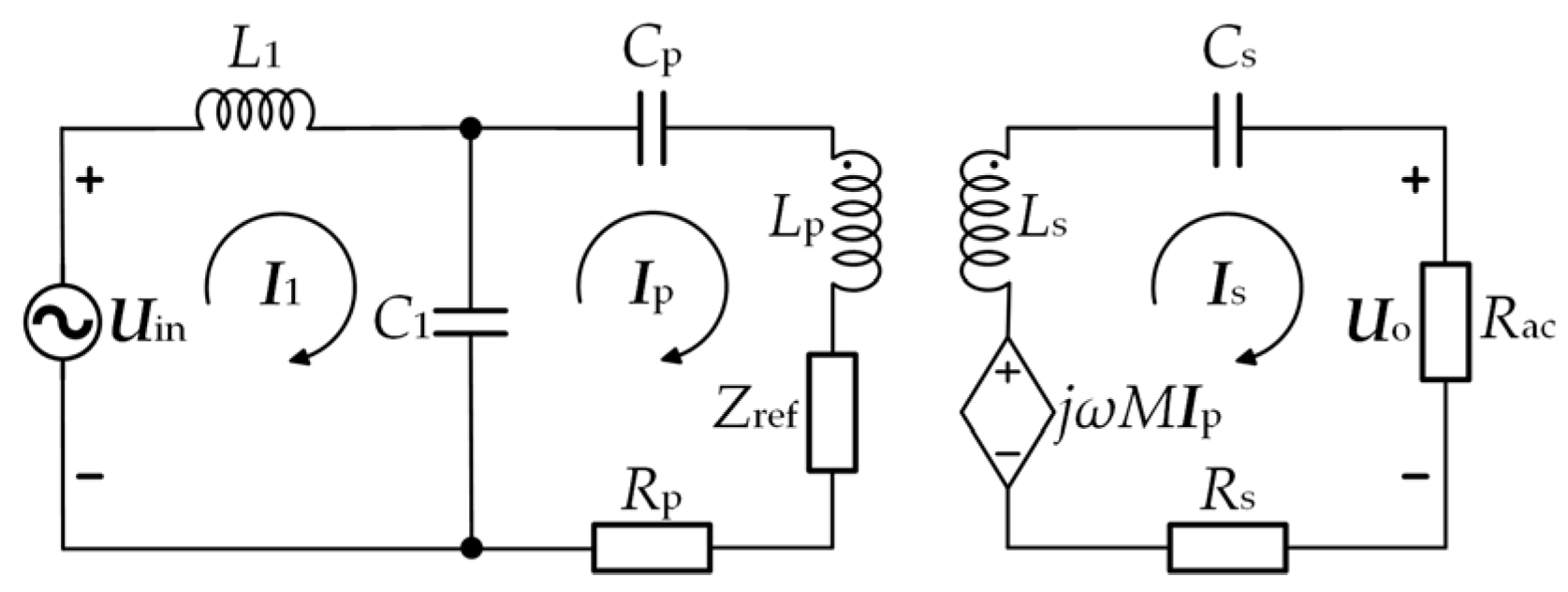

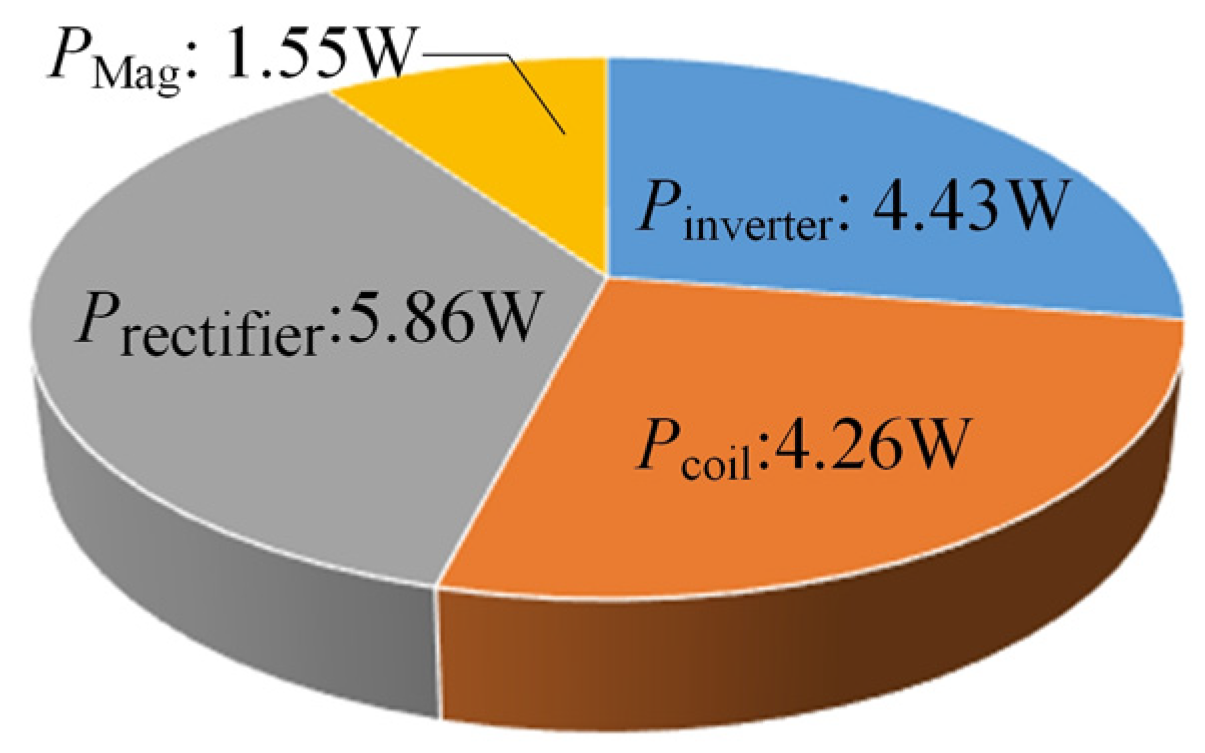

3.1. Power Transmission Channel

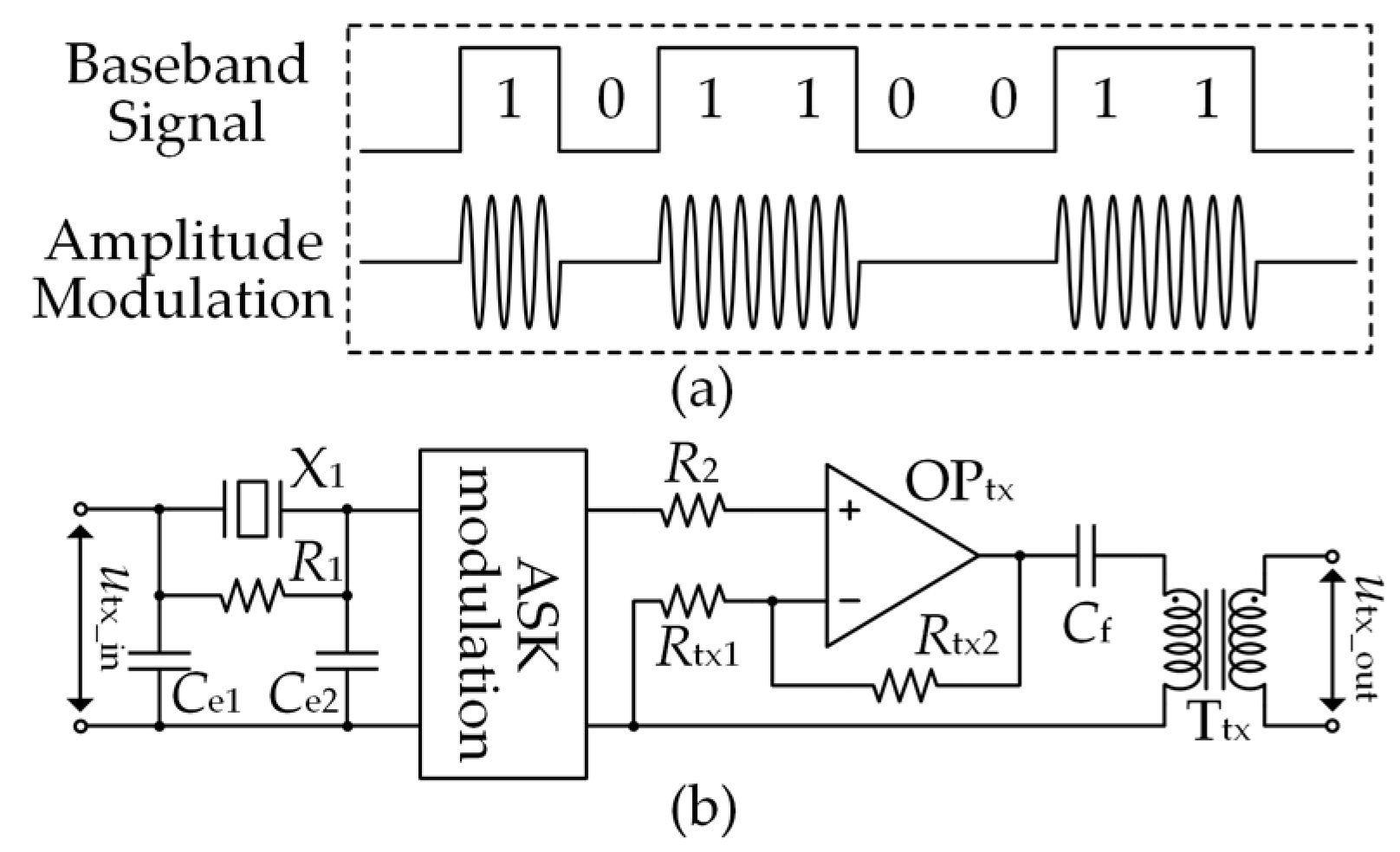

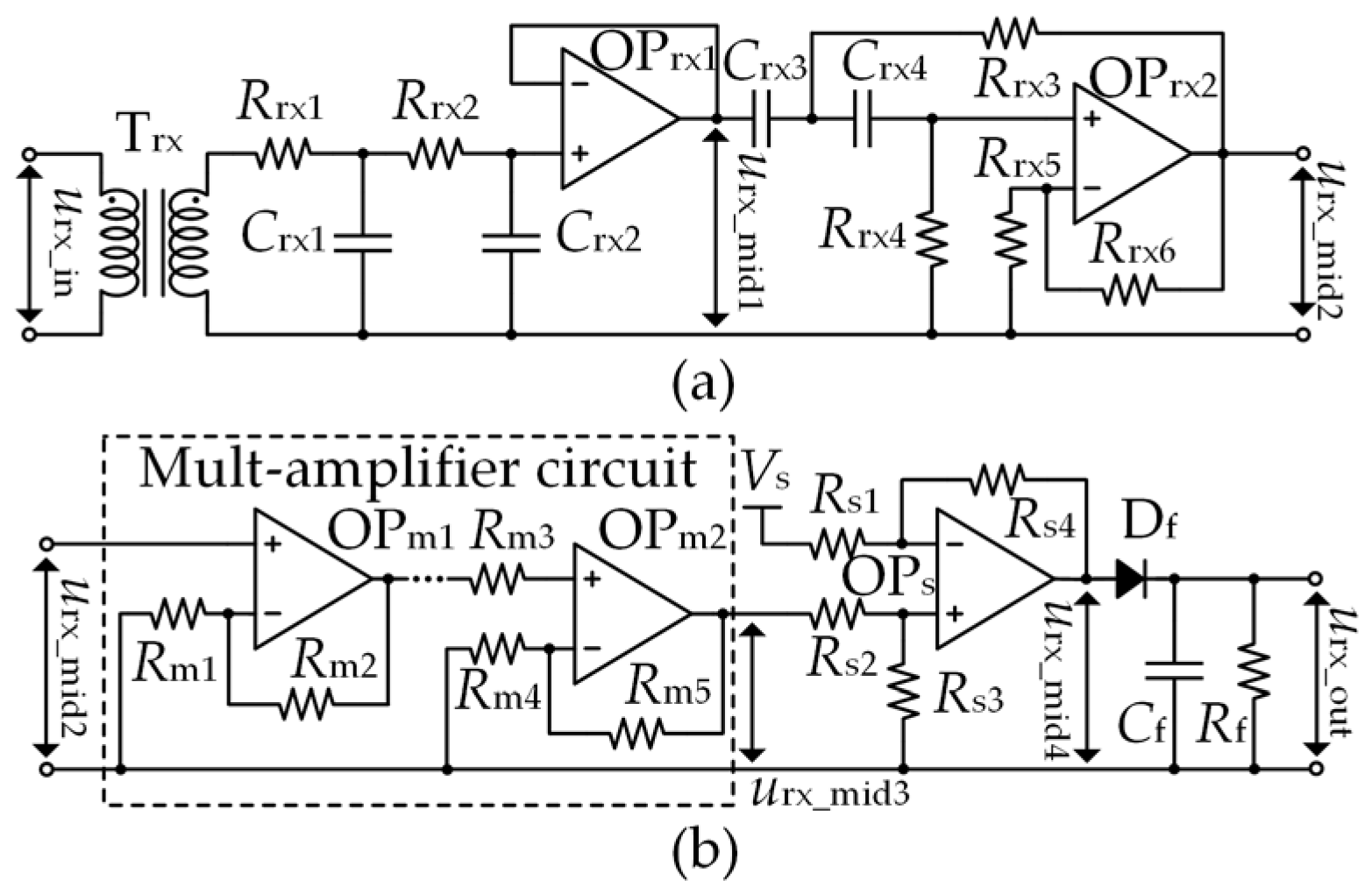

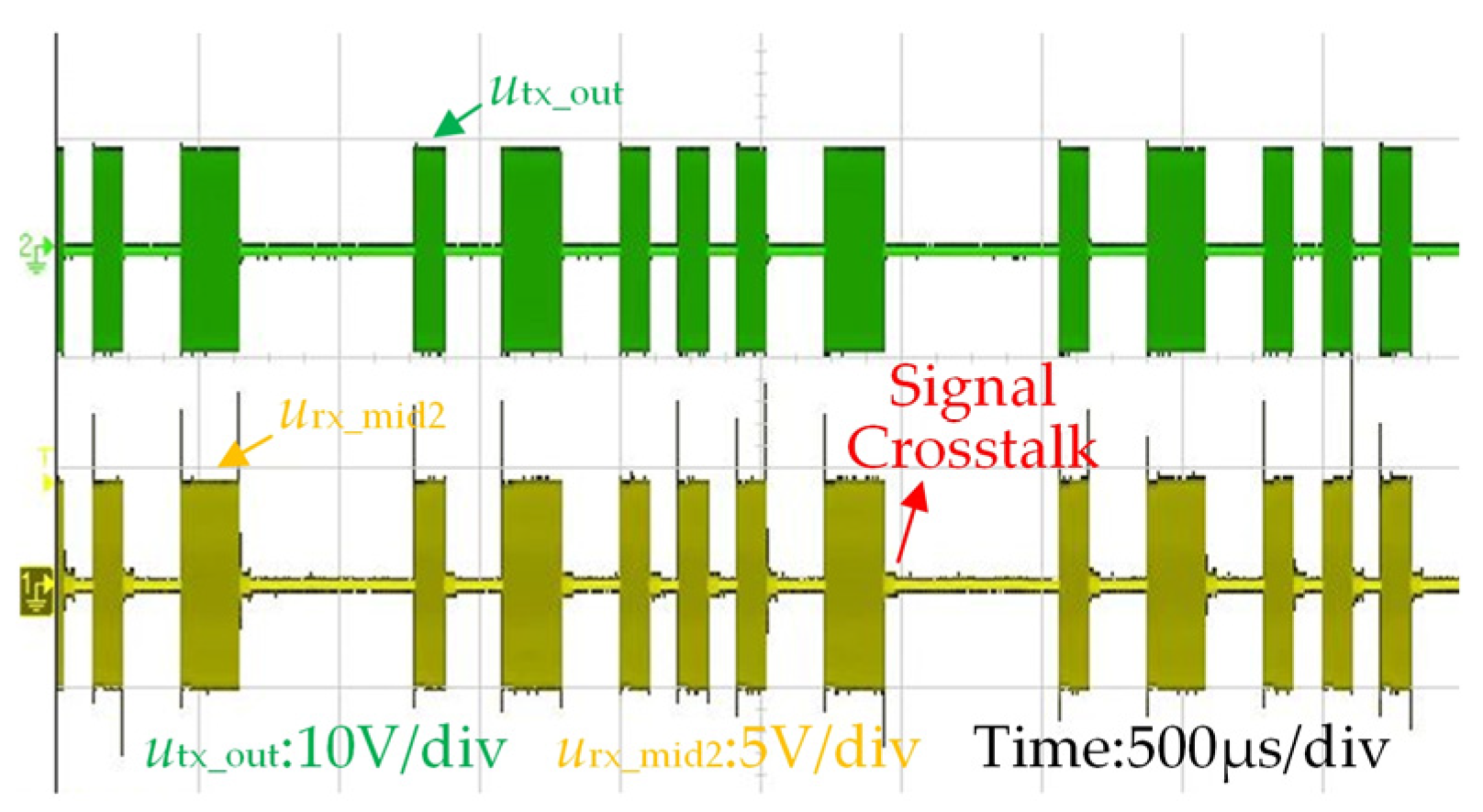

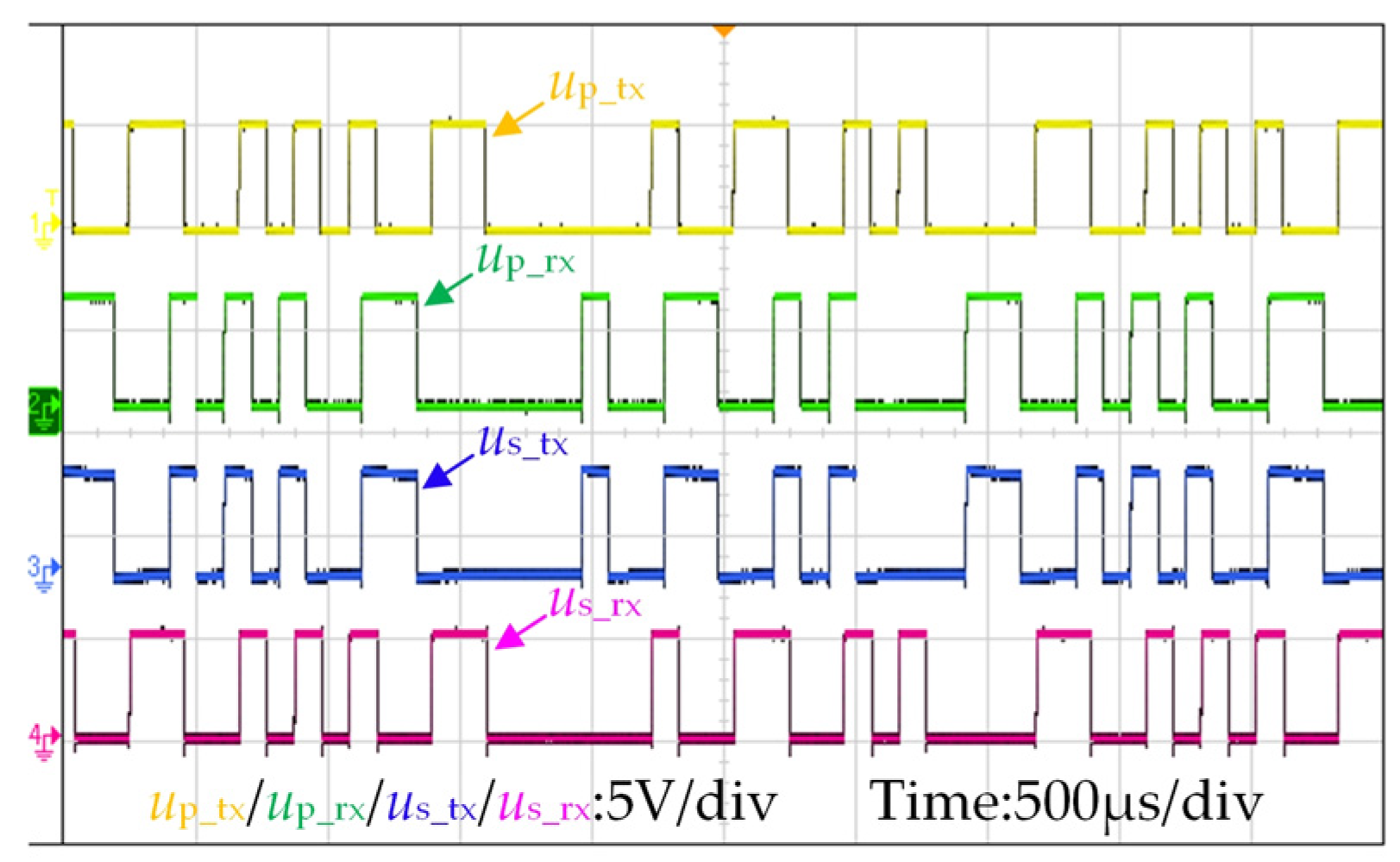

3.2. Signal Transmission Channel

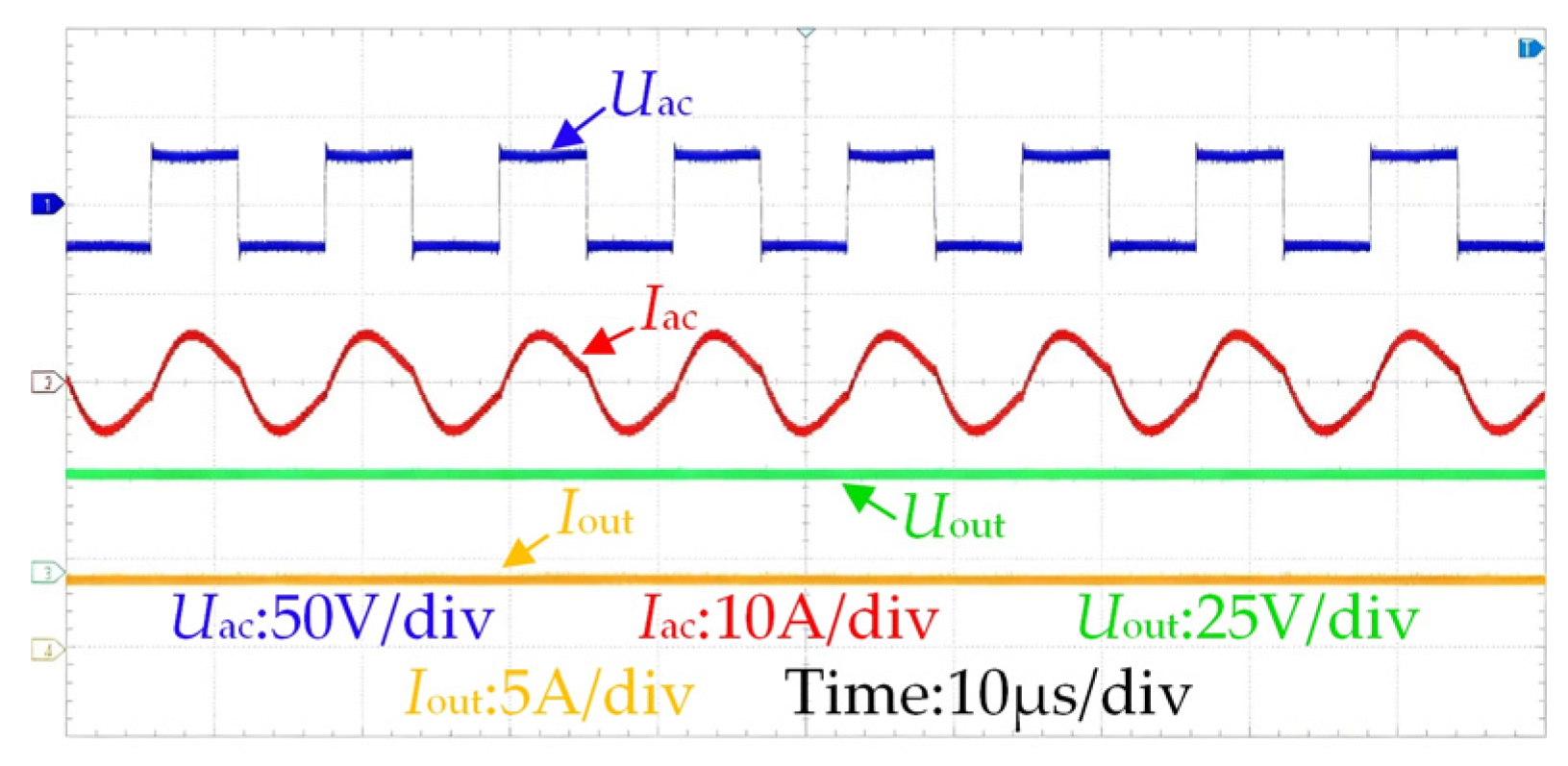

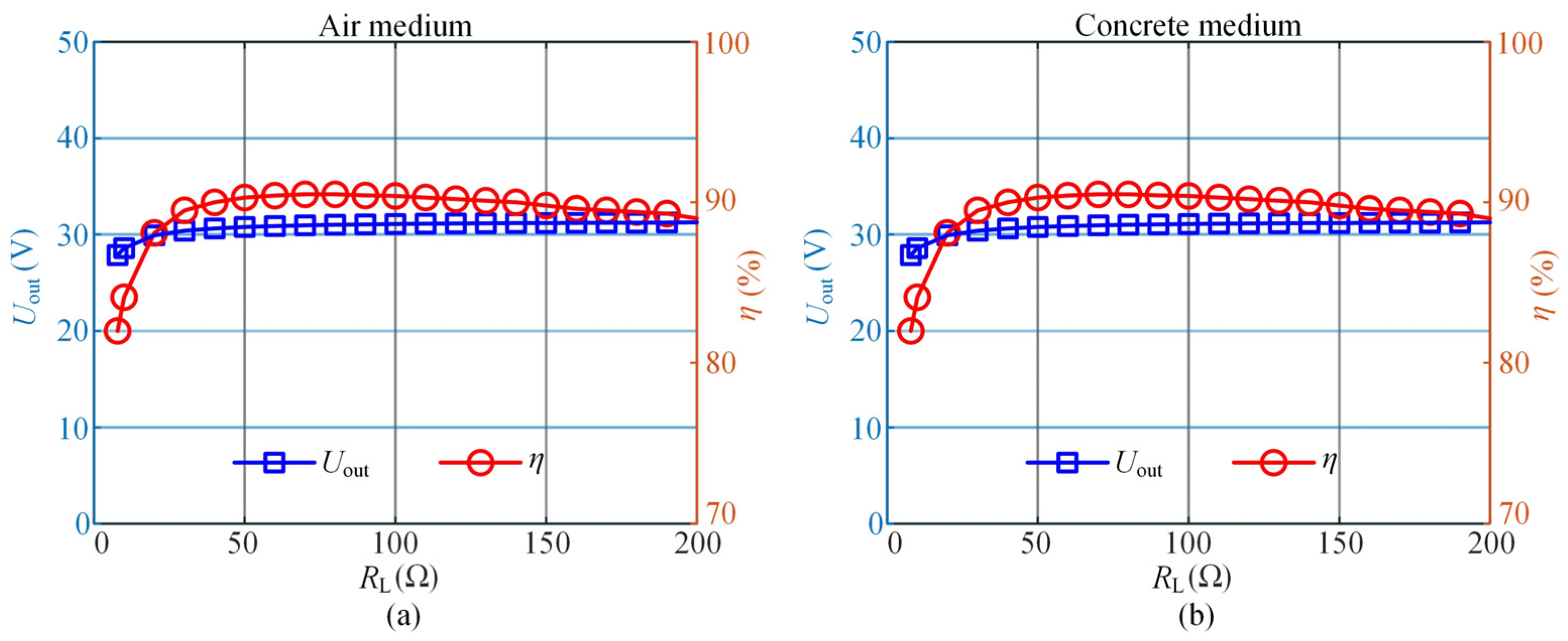

4. Experimental Verification

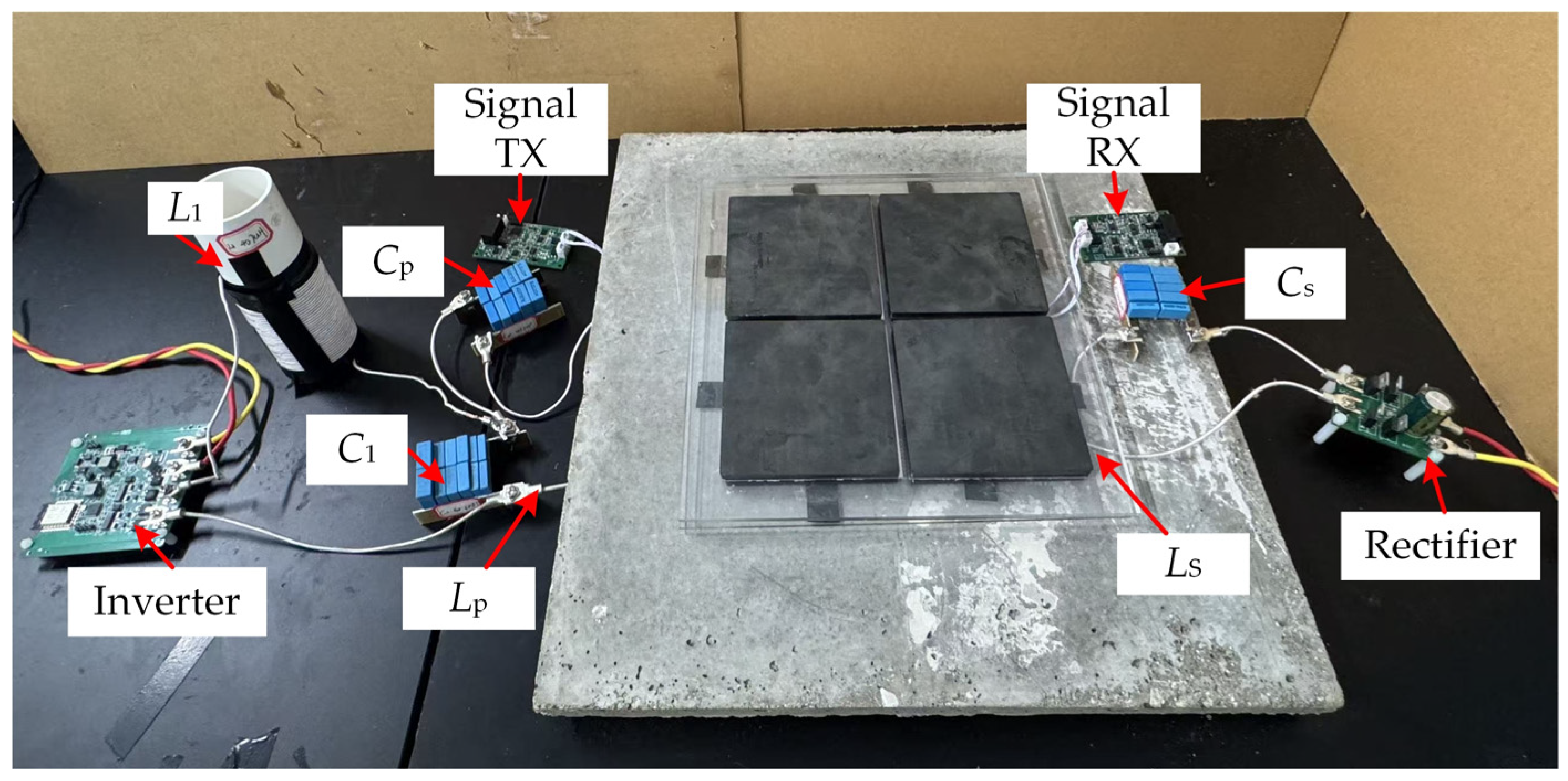

4.1. Experimental Prototype

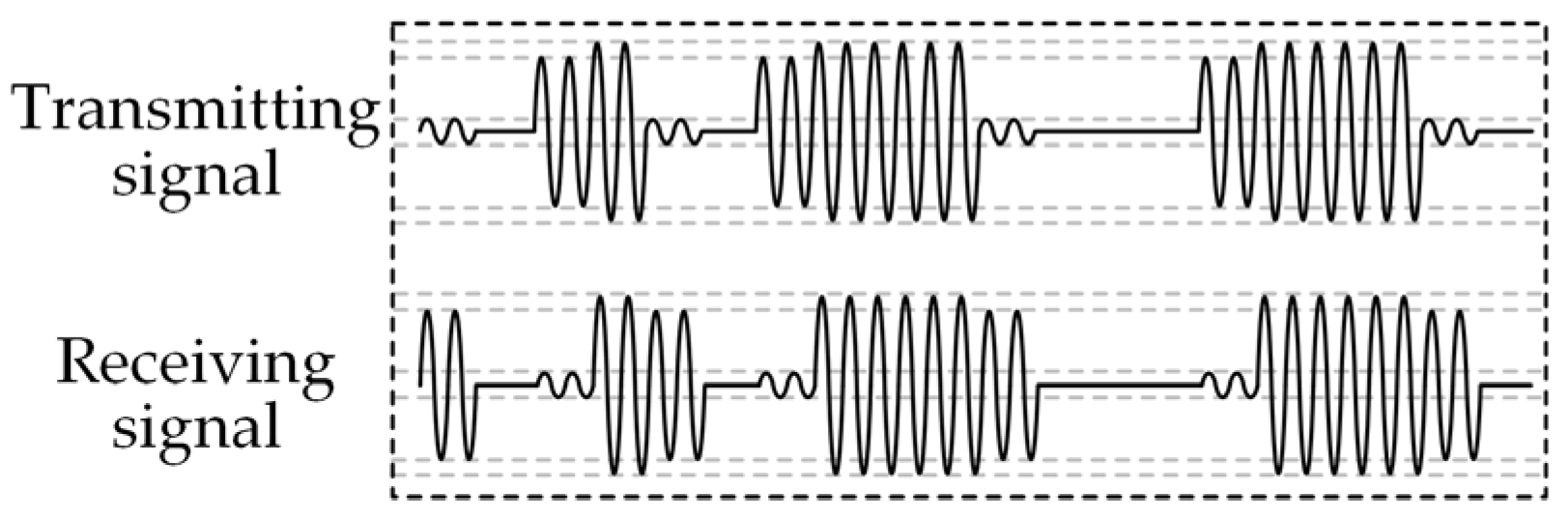

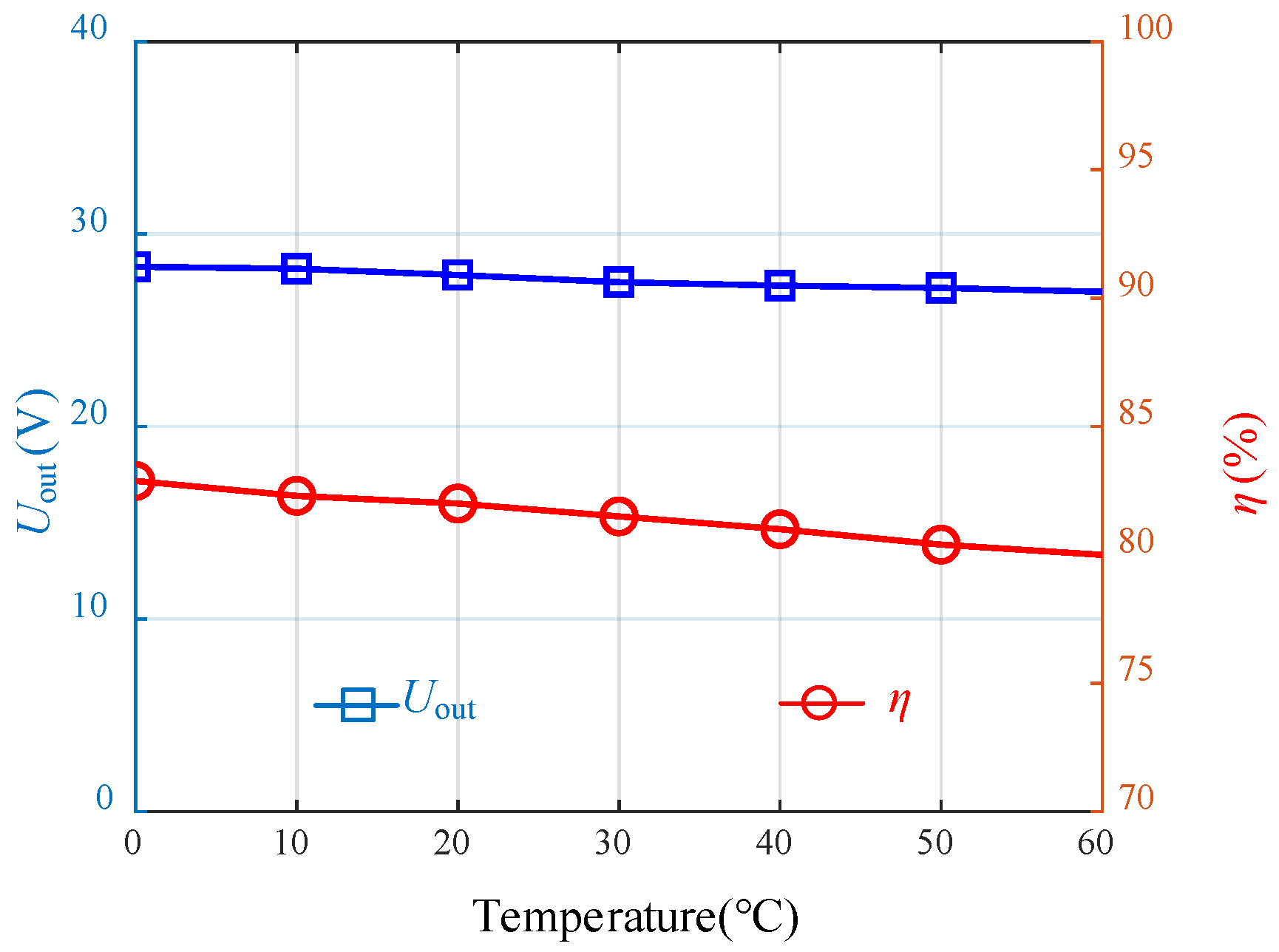

4.2. Discussion of Experimental Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Jing, B.; Wang, X.; Li, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zou, J.; Luo, X.; Liu, F.; Li, G. Frequency measurement method of vibrating wire sensor in complex noise environment. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Advanced Control Systems and Automation Technologies, Nanjing, China, 15–17 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Han, D.; Kim, K.; Shin, J.; Park, J. Gesture-based secure authentication system using triboelectric nanogenerator sensors. Sensors 2025, 25, 5170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, Y.; Ma, E.; Wang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Mai, R.; Madawala, U.K. Maximizing output power of inductive power transfer systems under rebar array shielding. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 13934–13945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Qi, W.; Chen, Y.; Mai, R.; Madawala, U.K. Wireless sensor power supply based on eddy currents for structural health monitoring. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 7252–7261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Ma, C.; Wang, Z. An Electro-Optic (EO) pulsed electric field sensor powered by photovoltaic cell. Phys. Scr. 2024, 99, 025001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, M.; Lourenco, P.B.; Ramana, G.V. Structural health monitoring of civil engineering structures by using the internet of things: A review. J. Build. Eng. 2022, 48, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almania, N.; Alhouli, S.; Sahoo, D. A photovoltaic light sensor-based self-powered real-time hover gesture recognition system for smart home control. Electronics 2025, 14, 3576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gouda, O.E.; Darwish, M.M.F.; Mahmoud, K.; Lehtonen, M.; Elkhodragy, T.M. Pollution severity monitoring of high voltage transmission line insulators using wireless device based on leakage current bursts. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 53713–53723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajad, H.; Alireza, H. A novel self-powered, high-sensitivity piezoelectric vibration sensor based on piezoelectric combo effect. IEEE Sens. J. 2023, 23, 25797–25803. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.; Jia, Q.; Hu, Y.; Yang, C.; Jian, L. Safety management technologies for wireless electric vehicle charging systems: A review. Electronics 2025, 14, 2380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlavan, S.; Shooshtari, M.; Maleki, M. Using overlapped resonators in wireless power transfer for uniform electromagnetic field and removing blank spots in free moving applications. Electronics 2022, 11, 1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlavan, S.; Shooshtari, M.; Jafarabadi Ashtiani, S. Star-shaped coils in the transmitter array for receiver rotation tolerance in free-moving wireless power transfer applications. Energies 2022, 15, 8643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de SouzaGomes, Y.; Saidi, M.; Lushnikova, A.; Ple, O. Fibre Optic-based patch sensor for crack monitoring in concrete structures. Strain 2025, 61, e12489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Dong, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, F.; Zhou, Q.; Ba, P. Research on the defect detection method of steel-reinforced concrete based on piezoelectric technology and weight analysis. Sensors 2025, 25, 3844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Z.; Cheng, H.; Li, Z.; Chen, F.; Chen, Y.; He, Z.; Mai, R. Wireless sensor power supply for rotating shaft using DC-side diode array with stable output. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 15414–15419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.L.; He, L.X.; Tang, N.; Lee, C.-K. Wireless power transfer using domino-resonator for 110-kV power grid online monitoring equipment. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 11380–11390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Sun, P.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, D. Simultaneous wireless power and data transfer: A comprehensive review. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 3650–3667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajer, R.; Chowdhury, A.; Redic, M. Demodulation of feedback signal for wireless charging systems according to the Qi standard. In Proceedings of the 2018 25th International Conference on Systems, Signals and Image Processing, Maribor, Slovenia, 20–22 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Y.; Yang, Y.; Hong, H.; Dai, Z. A simultaneous wireless power and data transfer system with full-duplex mode for underwater wireless sensor networks. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 12570–12583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xie, S.; Chen, L. A capacitive power and signal transfer system based on ring-coupler with mitigated inter-channel crosstalk. Electr. Eng. 2024, 106, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J. Misalignment Tolerance Improvement and High Efficiency Design for Wireless Power Transfer System Based on DDQ-DD Coil. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2024, 52, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da, C.; Wang, L.; Li, F.; Tao, C.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of Undersea Simultaneous Wireless Power and 1 Mb/s Data Rate Transfer System Based on DDQ Coil. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 11814–11825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Wang, M.; Tang, J.; Wang, T.; Bai, L.; You, J. An Underwater Simultaneous Wireless Power and Analog-Digital Hybrid Signal Transfer System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 17569–17574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Wu, S.; Xiao, J.; Wang, Z. A Bidirectional Simultaneous Wireless Power and Data Transfer System with Non-Contact Slip Ring. Electronics 2024, 13, 3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Mu, X.; Chen, J. Hybrid Beamforming Design for Near-Field SWIPT Networks. In Proceedings of the ICC 2024—IEEE International Conference on Communications, Denver, CO, USA, 9–13 June 2024; pp. 1807–1812. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter | Definition | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ein | DC input voltage | 28.00 | V |

| f | Operating frequency | 100.00 | kHz |

| L1 | Compensation inductor at primary side | 40.70 | μH |

| Lp | Self-inductance of transmitting coil | 102.30 | μH |

| Ls | Self-inductance of receiving coil | 106.40 | μH |

| M | Mutual inductance of the coupler | 60.67 | μH |

| C1 | Compensation capacitor at primary side | 62.20 | nF |

| Cp | Compensation capacitor for transmitting coil | 41.10 | nF |

| Cs | Compensation capacitor for receiving coil | 23.80 | nF |

| RL | Load resistor | 7.84 | Ω |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| rds | 0.11 Ω | VF | 0.7 V |

| toff | 3 × 10−7 s | rd | 0.05 Ω |

| ioff | 0.29 A | io | 3.06 A |

| i1 | 4.36 A | r1 | 0.08 Ω |

| i2 | 0.57 A | r2 | 0.17 Ω |

| i3 | 3.98 A | r3 | 0.17 Ω |

| Parameter | Simulated Value | Experimental Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ein | 28.00 | 28.00 | V |

| I1 | 4.29 | 4.36 | A |

| Uo | 28.08 | 26.53 | V |

| Io | 3.58 | 3.77 | A |

| Pin | 120.12 | 122.08 | W |

| Po | 100.53 | 100.02 | W |

| η | 83.70% | 82.0% | / |

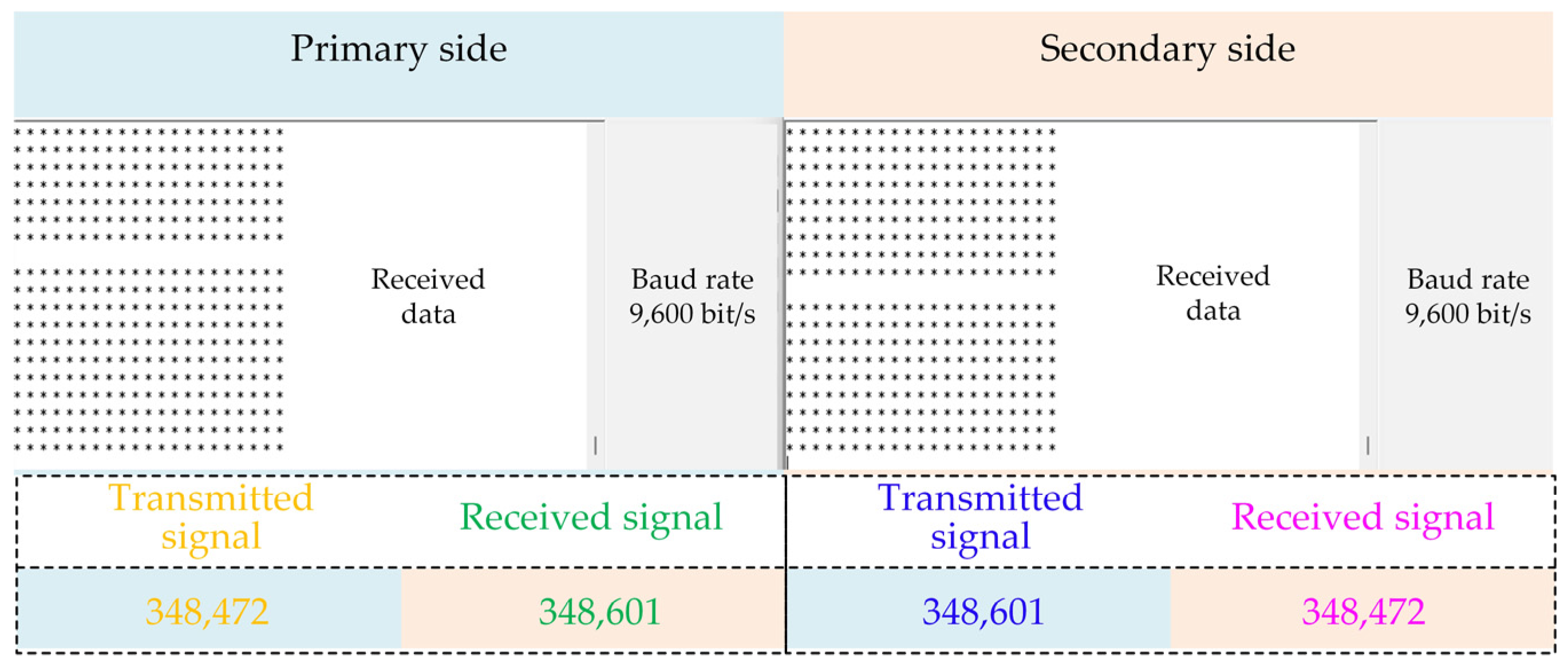

| Test | Primary Side | Secondary Side | Error Rate | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transmitted Signal | Received Signal | Transmitted Signal | Received Signal | ||

| 1 | 348,472 | 348,601 | 348,601 | 348,472 | 0% |

| 2 | 327,561 | 329,652 | 329,652 | 327,561 | 0% |

| 3 | 356,325 | 355,896 | 355,896 | 356,325 | 0% |

| This Paper | [19,23] | [24,25] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Power/Signal Decoupling | No additional design is required, relying only on the natural decoupling of the electric field and magnetic field | Relies on complex filter circuits | Relies on precision-decoupled coil structures |

| Bidirectional Signal Decoupling | Simple orthogonal structure of coupling plates | Not realized | Not realized |

| Filter Circuit | Simple | Very complicated | Simple |

| Coupler structure | No additional components | No additional components | No additional components |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, X.; Wei, X.; Jia, L. Electric-Field and Magnetic-Field Decoupled Wireless Power and Full-Duplex Signal Transfer Technology for Pre-Embedded Sensors. Electronics 2025, 14, 4302. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214302

Wang X, Wei X, Jia L. Electric-Field and Magnetic-Field Decoupled Wireless Power and Full-Duplex Signal Transfer Technology for Pre-Embedded Sensors. Electronics. 2025; 14(21):4302. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214302

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Xiaolong, Xiaozhou Wei, and Laiqiang Jia. 2025. "Electric-Field and Magnetic-Field Decoupled Wireless Power and Full-Duplex Signal Transfer Technology for Pre-Embedded Sensors" Electronics 14, no. 21: 4302. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214302

APA StyleWang, X., Wei, X., & Jia, L. (2025). Electric-Field and Magnetic-Field Decoupled Wireless Power and Full-Duplex Signal Transfer Technology for Pre-Embedded Sensors. Electronics, 14(21), 4302. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14214302