Abstract

The proposed forest monitoring photo trap ecosystem integrates a cost-effective architecture for observation and transmission using Internet of Things (IoT) technologies and long-range digital radio systems such as LoRa (Chirp Spread Spectrum—CSS) and nRF24L01 (Gaussian Frequency Shift Keying—GFSK). To address low-bandwidth links, a novel approach based on the Monte Carlo sampling algorithm enables progressive, bandwidth-aware image transfer and its thumbnail’s reconstruction on edge devices. The system transmits only essential data, supports remote image deletion/retrieval, and minimizes site visits, promoting environmentally friendly practices. A key innovation is the integration of no-reference image quality assessment (NR IQA) to determine when thumbnails are ready for operator review. Due to the computational limitations of the Raspberry Pi 3, the PIQE indicator was adopted as the operational metric in the quality stabilization module, whereas deep learning-based metrics (e.g., HyperIQA, ARNIQA) are retained as offline benchmarks only. Although single-pass inference may meet initial timing thresholds, the cumulative time–energy cost in an online pipeline on Raspberry Pi 3 is too high; hence these metrics remain offline. The system was validated through real-world field tests, confirming its practical applicability and robustness in remote forest environments.

1. Introduction

Despite the continuous advancement of data transmission systems aimed at achieving global Internet coverage, there remain regions where the network is either unavailable, limited, or too expensive. One approach to mitigating this issue involves shifting a part of the data transmission to long-range radio networks, e.g., LoRa-based solutions or using the nRF24L01 module. Within the scope of this study, the focus is placed on economically viable solutions that do not increase the overall investment cost. Unfortunately, many of these solutions, although offering free data transmission, suffer from very low bitrates.

Nevertheless, there exists a category of applications where slow image transmission is acceptable due to longer permissible data collection times. A good example of such a device is the camera trap. Forest camera traps, in particular, are deployed in locations characterized by significant distances between devices and a lack of network infrastructure, often in areas without access to stationary power sources.

Among the available long-range radio technologies, the LoRa standard is selected for analysis due to its demonstrated capability to transmit large datasets in the form of images from cameras, as evidenced in previous studies [1,2,3,4]. An alternative type of long-range transmission compared to LoRa may be provided by the popular nRF24L01 module [5,6,7,8]. The technological limitation of low bitrate is addressed by the authors through data reduction techniques, including strong compression and optional image size reduction. The segmentation of the image into smaller compressed parts reduces the amount of data required for the retransmission of lost fragments while still allowing for full image reconstruction upon the successful transmission of all segments. However, a compression combined with image size reduction may result in the loss of critical information. The above-referenced implementations do not address the accuracy of image content transfer or the quality of the transmitted image. Moreover, these solutions significantly reduce energy efficiency during emergency retransmissions, thereby limiting their practical applicability.

Based on these observations, some postulates are formulated for optimizing data transmission from camera traps. First, image data transmission is ensured in a way that allows image quality to improve over time as more data is received, enabling preliminary content recognition by human observers and maintaining high energy efficiency. In the context of image quality control, image quality indicators are used for evaluation. To assess the correctness of image transmission, blind metrics [9,10,11] may be employed. Considering the postulate of energy efficiency, the selection of quality indicators should take into account the computational power requirements. In this study, existing solutions are analyzed, and an energy-optimized alternative is proposed that incorporates image quality evaluation and an effective data reduction and control process for proper image reconstruction.

Effective data reduction for transmission is achieved using the Monte Carlo method to generate image thumbnails while preserving essential image details. This serves as an alternative to lossy compression with resolution reduction [12]. This study considers the Monte Carlo method in the context of transmitting individual image samples, which is not addressed in the cited works.

In contrast to the previous Monte Carlo thumbnailing work [12], our method extends the application of Monte Carlo sampling beyond thumbnail generation. We apply it in a real-world, constrained wireless transmission scenario where the sampling process is directly coupled with physical data transmission over long-range RF links.

This combination with an adaptive stopping mechanism based on no-reference IQA metrics is, to our knowledge, novel. Unlike file transfer protocols, where total data volume is predetermined, our approach determines transmission length dynamically based on reconstructed image quality, enabling energy-optimal operation.

Unlike classical progressive/embedded coders (progressive JPEG, SPIHT/EBCOT) [13,14], our method

- does not rely on transform/entropy coding, which is vulnerable to bit errors;

- assumes strictly unidirectional transmission without retransmissions;

- transmits raw random pixel samples inherently resilient to packet loss;

- achieves graceful degradation (noise) rather than catastrophic failure.

This study aims to design and evaluate a forest camera trap network that minimizes energy consumption and RF bandwidth usage while maintaining sufficient image quality for operator-based wildlife identification. Specific objectives include the following: developing a Monte Carlo-based progressive transmission protocol, identifying computationally feasible no-reference IQA metrics for adaptive stopping, comparing LoRa and nRF24L01 performance in forest environments, and demonstrating practical deployment feasibility with off-the-shelf IoT components.

2. Photo Trap Ecosystem

The hardware components of the ecosystem have to address the following fundamental requirements:

- The minimization of investment costs.

- Low energy consumption.

- Long-range radio transmission.

- Short-range radio or wired transmission for local device interconnections.

- Access to the Internet, e.g., via a GSM gateway.

- Sufficient computational resources for offline image processing.

A group of lightweight solutions exists for embedded devices, enabling edge processing using units with limited computational capabilities. The hardware platform must be accompanied by optimized algorithms that ensure a balance between image quality and performance while maintaining the assumed energy efficiency and meeting strict cost optimization requirements.

Following hardware, which is essentially a one-time purchase (unless lost, which is not uncommon in forest environments), the next cost factor is associated with maintaining data transmission in telecommunication networks. Modern solutions such as Starlink are excluded due to their cost, with preference given to GPRS transmission in GSM networks and integration with the Internet. Due to the abundance of available offers, no specific provider is analyzed; it is assumed that a cost-effective solution can be found for the defined ecosystem task. In contrast to free-of-charge networks, such as LoRa and nRF24L01, which operate in license-free bands, GSM-based transmission may involve operational costs; however, the wide range of available offers allows for selecting an optimal plan tailored to the system’s requirements. Nevertheless, this non-zero cost is typically related to the volume of transmitted data. Therefore, the algorithms are designed to optimize the amount of transmitted data, ensuring that only the data necessary for situational assessment is sent, i.e., required to decide whether an image should be retained or deleted, without the need for physical site visits.

2.1. Base Components

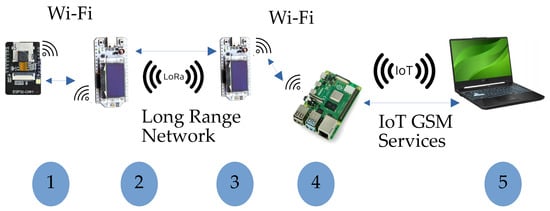

The base components of the photo trap ecosystem (Figure 1) include the following:

Figure 1.

Base components of photo trap ecosystem. 1—camera; 2,3—microcontroller with long-range RF network modem; 4—IoT GSM gateway; 5—user interface; WiFi—local short-range network.

- Camera—provides access to any pixel of the recorded image and allows for the deletion of unnecessary images;

- Microcontrollers with long-range RF network modems—enable the transmission of collected data;

- IoT GSM gateway—ensures integration with the GSM network;

- Operator workstation—equipped with software for evaluating and selecting transmitted images.

Some components may be functionally combined into a single module to reduce purchase costs by eliminating one microcontroller. However, such a solution may complicate development due to the diversity of system architectures.

Table 1 presents some popular universal platforms with Linux-based operating systems available on the market in the embedded device category, comparing their computational performance, energy efficiency, and costs. These platforms most commonly perform key Industrial IoT (IIoT) [15,16] tasks within edge or Fog computing models. The presence of embedded operating systems enhances their flexibility in engineering practice. The results from the 7-Zip benchmark test for the most popular embedded platforms, allowing for a performance comparison based on standardized ratings in a specific operating environment, are presented. In terms of performance, the Jetson Orin Nano [17] is the best choice; however, its high purchase cost and significant energy consumption make it unsuitable from an economical point of view. However, the Jetson Nano family offers CUDA acceleration for computational processes with low response time requirements. Nevertheless, this feature is not decisive for the selection of the platform.

Table 1.

Comparison of computational performance and energy efficiency of embedded platforms with prices valid on date of data acquisition.

The most balanced choice is the Raspberry Pi 4, which offers very good performance [18] in relation to its purchase cost and low energy consumption. Nevertheless, in our tests, we use the Raspberry Pi 3 to verify and optimize the algorithms under worst-case conditions. Additionally, it represents the most cost-effective solution.

However, certain system tasks exhibit lower requirements in terms of responsiveness and computational power. Within the proposed ecosystem, this includes a camera module and transmission modules integrated with a microcontroller. Our focus is placed on the widely adopted Arduino software platform (ver. 1.8.19 for Linux), which facilitates the rapid deployment of technical projects, thereby reducing the cost of application development and testing. This process is further supported by the use of sketches—predefined code snippets readily adaptable for integration into custom applications.

Table 2 presents a comparison of parameters for popular microcontrollers compatible with the Arduino environment. Although energy consumption across both platforms is comparable, performance metrics clearly indicate ESP32 as the most advantageous solution.

Table 2.

Comparison of Arduino Mega 2560 and ESP32 DevKit in terms of cost and performance.

Since both the ESP32 and Raspberry Pi 3 platforms have integrated interfaces for the Wi-Fi standard, the next step involves selecting appropriate transmission modules. We consider two standards operating in license-free radio bands, both of which support documented long-range communication and maintain compatibility with the Arduino platform. The first is the LoRa transmission standard, represented by the SX1278 module; the second is the nRF24L01 module, which operates in the 2.4 GHz ISM band. The costs associated with acquiring and these modules are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Feature comparison between LoRa (SX1276) and nRF24L01 modules.

System transmission to the operator’s station is provided via a GSM modem and the Internet. When used as an IoT gateway, the Raspberry Pi 3 enables integration with a wide range of GSM modems through its USB ports, supporting various transmission standards. The market offers a broad selection of modems priced from a few to several USD, allowing for flexible adaptation to the financial model of the communication service provided by the operator.

2.2. Image Transfer and Reconstruction

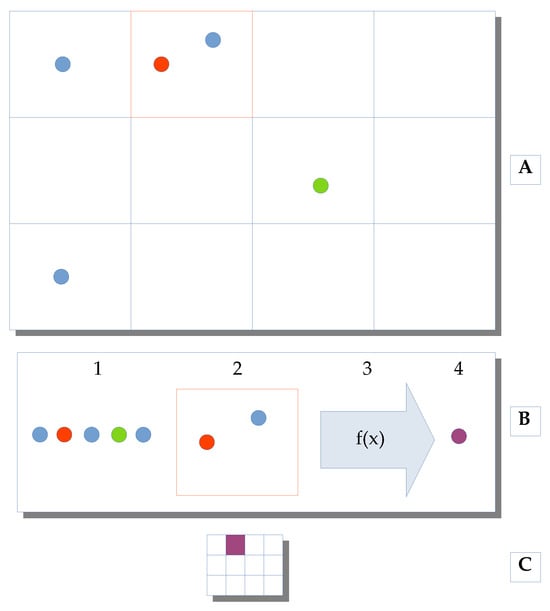

The use of long-range RF networks is inherently constrained by limitations in signal power and transmission distance, which consequently lead to a significant reduction in bitrate. One approach to mitigating this issue involves reducing the volume of transmitted data. To achieve this, we employ Monte Carlo sampling to limit the number of transmitted data points and reconstruct image thumbnails from the sampled data. This method has previously been proposed as an alternative to conventional image downscaling algorithms; the full theoretical aspect of the method is presented in [19]. The image thumbnail shown in Figure 2 is generated by randomly selecting N pixels without replacement and grouping them into blocks of a predefined size (e.g., 6 × 6, 8 × 8, or 16 × 16 pixels) based on their original spatial locations in the image. For each block, a new pixel value is computed using a predefined function f(x)—for example, the arithmetic mean that is used in further studies, considering it as a convenient practical recommendation.

Figure 2.

Monte Carlo image sampling, data transfer, and block-based image reconstruction. (A)—original image with chosen pixels; (B) (1)—data stream from chosen pixels; (B) (2)—reconstruction placement in defined block; (B) (3)—reconstruction pixel formula; (B) (4)—new pixel after reconstruction; (C)—reconstructed image with calculated pixel in position determined by block from original image.

The resulting image serves as an approximation of the original, with its quality depending on the number of samples used in the reconstruction. The greater the number of samples, the higher the fidelity of the reconstructed image.

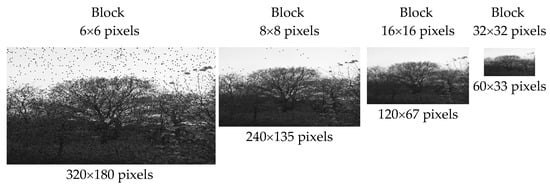

Depending on the chosen block size, the reconstruction yields thumbnails of varying resolutions, as illustrated in Figure 3. For the block size of 6 × 6 pixels, the resulting image resolution approximates the Common Intermediate Format (CIF), which provides sufficient visual clarity for an operator’s analysis of transmitted image thumbnails. It is worth noting that the CIF defines a video sequence with a resolution of 352 × 288 pixels, used in the Video CD, although significantly smaller than a typical one in the PAL standard which is 720 × 576 pixels. Some other low-resolution reconstruction variants are less suitable for human perception but may still be valuable for scene analysis by artificial intelligence systems.

Figure 3.

Image reconstruction with a new image size for a variable block size and 200,000 chosen samples; image ID 3250.

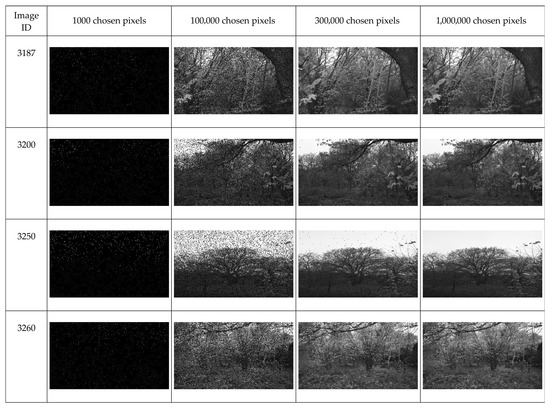

Figure 4 presents four example image reconstructions (rows) obtained with varying numbers of analyzed samples (columns). For 1000 samples, individual reconstructed pixels are visible against the original background, which appears as an artifact resulting from the initialization (zeroing) of the reconstruction array. In subsequent iterations, the images exhibit progressively improved quality, with a decreasing number of artifacts caused by blocks lacking pixel information. These artifacts can either be filtered out or allowed to disappear naturally as more samples are acquired, assuming the sampling process is continuous and the number of samples increases over time.

Figure 4.

Image reconstruction and artifact visualization for block size of 6 × 6 pixels and different numbers of chosen samples.

With 300,000 samples (nearly seven times fewer than the 2,073,600 pixels in an original Full HD image), a clear and detailed reconstruction is achieved, with only minor distortions remaining.

2.3. Data Flow Optimization Processes

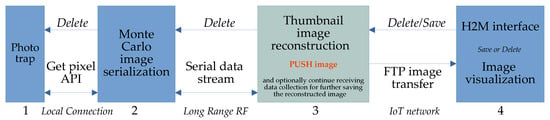

Figure 5 illustrates exemplary information flows within the proposed ecosystem. On one hand, control commands are transmitted, allowing the operator to delete irrelevant images (Delete) or retain them (Save). On the other hand, the primary data stream consists of image data transmitted using Monte Carlo sampling.

Figure 5.

Information flow in photo trap ecosystem: 1—image source; 2—Monte Carlo sampling and data stream sender; 3—data stream receiver for image reconstruction and FTP client; 4—FTP server and application interface; PUSH image—decision process for sending thumbnail or reconstructed image.

The system faces two major constraints:

- Long-range radio networks are characterized by a low bitrate, necessitating data reduction to ensure realistic image transmission times;

- In GSM networks, operators may charge fees based on the volume of transmitted data.

An optimization scenario aimed at reducing network traffic is as follows. Image sampling is performed continuously until all data are transmitted, whereas reconstruction (at the IoT gateway) is executed cyclically. Only a thumbnail of predefined quality is sent to the operator. The transmission process is paused until the operator decides whether to retain or discard the image, based on the evaluation of its contents. If the image should be retained, transmission resumes during periods of system idle time. Once the full image is received, it is made available to the operator for archiving and subsequently deleted from both the camera and the IoT gateway.

A critical aspect of this approach is the automatic determination of the moment when the image reaches sufficient clarity to be submitted for evaluation, taking into account the limited computational resources of the IoT gateway.

To assess the quality of the reconstructed image, blind image quality assessment (IQA) metrics can be used, along with a decision criterion that determines when the image is acceptable for visual content evaluation.

From the variety of blind IQA metrics available in the PyIQA library [20], only those capable of completing computations without software failure or excessive runtime were selected—initially, under 10 min for Full HD images and under 30 s for thumbnails. Metrics were initially filtered by the above time constraints to allow for comparative analysis; however, for operational deployment, only those with sub-second thumbnail evaluation were considered feasible. Although some metrics, such as HyperIQA, met the specified thresholds, their cumulative time–energy cost in an online pipeline on the Raspberry Pi 3 was unacceptable within the system’s operational budget; therefore, they remained offline benchmarks only. The most common cause of failure was insufficient memory, particularly for indicators based on deep learning models. Table 4 summarizes the computation times on a Raspberry Pi 3 for Full HD and 320 × 180-pixel thumbnail images.

Table 4.

Computation time on Raspberry Pi 3 for various IQA metrics with 95% confidence intervals, expressed in seconds.

“Software error” refers to any condition that leads to uncontrolled program termination, most often due to memory allocation errors in image processing libraries. “Excessive execution time” is defined as an empirically determined time threshold of 30 s devoted for computing an IQA metric for a single image.

The evaluation was conducted on a test set of 140 Full HD images captured in forest environments under various conditions and perspectives, along with their corresponding thumbnails generated during reconstruction using different numbers of randomly sampled pixels. All blind IQA indicators available in PyIQA were considered, but only five of them, meeting the above-mentioned time constraints, were included in further analysis.

A brief overview of the blind image quality assessment metrics selected for further analysis is presented below. Each metric represents a distinct methodological approach to evaluating image quality without reference images and has been chosen based on its computational feasibility on resource-constrained platforms such as the Raspberry Pi 3.

The five methods considered in the analysis include the following:

- ARNIQA (leArning distoRtion maNifold for Image Quality Assessment) [21]—A modern deep learning-based metric that utilizes neural networks to learn distortion manifolds in a self-supervised manner; it is based on the assumption that different types of distortions form continuous spaces in the feature domain, enabling more precise quality assessment.

- BRISQUE (Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator) [22]—A classical metric based on natural scene statistics (NSS), which analyzes local distortions in the spatial domain; it employs a linear regression model to predict image quality based on statistical features extracted from the image; it is fast and reliable for traditional types of distortions.

- HyperIQA [9]—An advanced deep learning metric that incorporates attention mechanisms and a hyper-network architecture to adaptively weight different image regions during quality assessment; it demonstrates a high correlation with human perception across a wide range of distortions.

- NIMA (Neural Image Assessment) [23]—A convolutional neural network-based metric that predicts a distribution of quality scores rather than a single value; it is trained on large datasets with human ratings and effectively models the subjectivity of image quality perception.

- PIQE (Perception-based Image Quality Evaluator) [24]—A metric focused on perceptual as pects of image quality, primarily analyzing blur and blocky distortions; it is computationally efficient and performs well on compressed and blurred images.

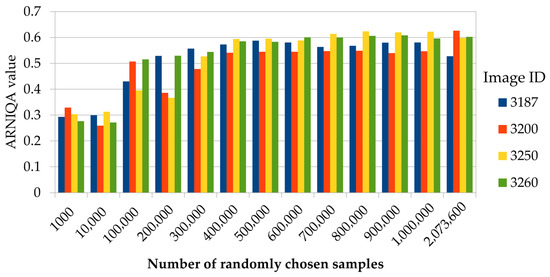

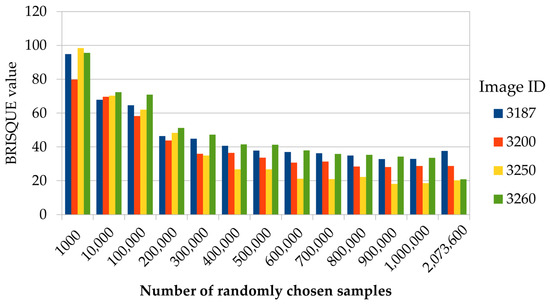

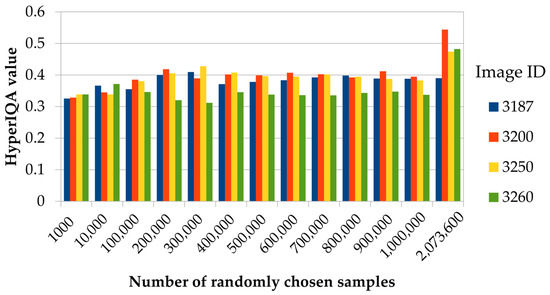

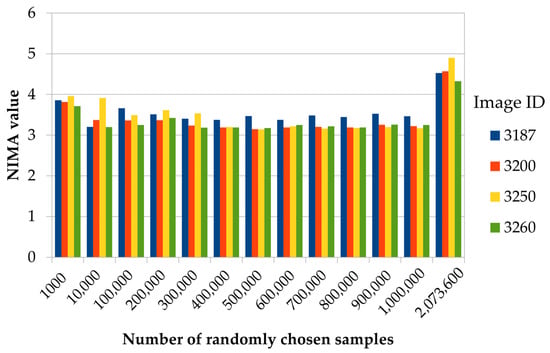

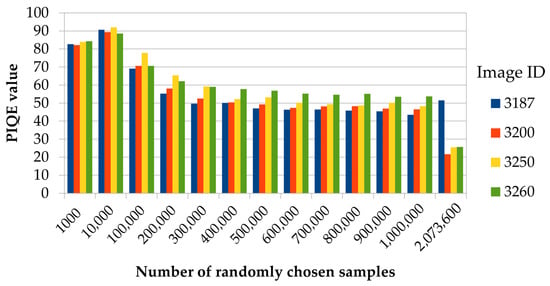

The analysis of the plots presented in Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 enables an assessment of the stabilization potential of each quality evaluation method, using the bars on the right (obtained for the maximum number of samples, i.e., the reconstructed image without the use of the Monte Carlo method) as a reference point. It is important to note that early stabilization and sensitivity to incremental improvements represent different aspects: HyperIQA reaches stable values early, although they are quite far from the reference ones, whereas the BRISQUE metric reacts more strongly to quality changes during reconstruction. It is also worth noting that the penultimate set of bars represents 1,000,000 samples, i.e., less than a half of the full reconstructed image, resulting in a visible difference between the values of some of the metrics for the last two sets of bars in Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10.

Figure 6.

ARNIQA image assessment value for image block size of 6 × 6 pixels and different numbers of chosen samples (reference for 2,073,600 pixels).

Figure 7.

BRISQUE image quality assessment value for image block size of 6 × 6 pixels and different numbers of chosen samples (reference for 2,073,600 pixels).

Figure 8.

HyperIQA image quality assessment value for image block size of 6 × 6 pixels and different numbers of chosen samples (reference for 2,073,600 pixels).

Figure 9.

NIMA image quality assessment value for image block size of 6 × 6 pixels and different numbers of chosen samples (reference for 2,073,600 pixels).

Figure 10.

PIQE image quality assessment value for image block size of 6 × 6 pixels and different numbers of chosen samples (reference for 2,073,600 pixels).

As mentioned, HyperIQA reaches stable values relatively early and then remains stable, whereas the BRISQUE metric exhibits the steepest convergence, making it the most sensitive to incremental improvements during reconstruction. Nevertheless, despite these observations, the PIQE indicator was initially selected for the considered application due to its balance of accuracy and computational efficiency. The PIQE results remain within a narrow range from 0.32 to 0.40, indicating high consistency in quality assessment. The ARNIQA values also stabilize relatively quickly, although this metric exhibits a greater variability during the initial stages of reconstruction. After surpassing 400,000 samples, the values stabilize within the range from 0.54 to 0.60. The NIMA indicator shows moderate stabilization, with a downward trend as the number of samples increases. The PIQE and BRISQUE metrics exhibit the slowest stabilization, with significant fluctuations throughout all reconstruction stages, making them less suitable for an early-stage quality evaluation.

Although HyperIQA demonstrates the fastest stabilization and leads to results consistent with expectations for relatively few samples, it is operationally infeasible on resource-constrained platforms such as the Raspberry Pi 3. It additionally confirms the choice of the PIQE as the practical metric for real-time implementation.

In practice, a more insightful approach involves analyzing the stabilization dynamics of no-reference image quality metrics during the reconstruction process. To quantify this behavior, the convergence rate coefficient b is introduced, defined as the slope in the linear regression model applied to the deviation sequence:

where the following notation is used:

- —deviation;

- b—convergence coefficient;

- j—sample index;

- a —intercept.

This formulation is adapted from classical linear regression theory [25] to address the specific challenge of evaluating the temporal behavior of no-reference quality metrics in low-data image reconstruction scenarios. The coefficient b quantifies how rapidly metric values converge toward their reference value, with negative values indicating the convergence and the magnitude representing the rate of stabilization. The formal definition is given as follows:

where

- n— number of samples;

- i—sample index;

- —deviation from the reference value.

Let denote the quality metric value computed from n randomly sampled pixels and the reference value obtained from the full reconstruction using all 2,073,600 pixels. The deviation quantifies the distance from the reference quality. The linear regression model assumes a constant convergence rate and a monotonic approach to . This assumption holds for 100,000 samples, where visual inspection and residual analysis confirm strong linear behavior across 140 forest images. The empirical threshold was validated by observing consistent convergence patterns with low residual variance in this sampling regime.

During analysis (the results are presented in Table 5), the following factors were taken into account:

Table 5.

Convergence rate coefficients for various IQA metrics and their interpretation.

- Data aggregation—all measurements across different images were treated as a single observation sequence;

- Common trend—the computed convergence rate coefficient (b) represents the overall tendency of approaching the reference value across the entire dataset;

- Averaging effects—differences between individual images were averaged;

- Assumed linearity—the convergence process was assumed to follow a linear trend, which may not hold in the early stages of reconstruction when the sample size is small.

Observations and practical implications:

- BRISQUE shows the fastest convergence toward the reference value, with a steep decline (coefficient = −2.674) as the number of reconstruction samples increases;

- PIQE also converges rapidly, with a coefficient of −0.916, indicating a systematic improvement in quality assessment during reconstruction;

- NIMA demonstrates moderate convergence speed (−0.058) but maintains stability throughout the process;

- ARNIQA and HyperIQA exhibit very small convergence coefficients (−0.001), suggesting that their values remain relatively stable during reconstruction, without a clear trend of improvement.

The PIQE’s (Table 6) opinion-unaware design and low computational cost make it optimal for real-time quality monitoring on resource-constrained IoT devices, despite its slightly lower correlation with subjective scores compared to the BRISQUE metric.

Table 6.

A comparison of PIQE and BRISQUE image quality assessment metrics.

This interpretation aligns with the convergence analysis: the BRISQUE indicator is the best for early detection due to its steep convergence trend, whereas HyperIQA stabilizes quickly but changes further only a little. Summarizing the analysis of the data presented in Table 4 and Table 5, as well as Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10, the optimal final choice—balancing computation time, stability, and convergence rate—is the PIQE metric. Moreover, the observed usage characteristics align well with the practical application guidelines for this metric.

Thumbnail Quality Selection Criteria and Simulation Results

Based on publicly available exemplary programs in MATLAB version R2025a and Python version 3.9.2, e.g., acquired from GitHub (https://github.com, accessed on 11 September 2025), StackOverflow (https://stackoverflow.com, accessed on 11 September 2025), etc., Table 7 summarizes the typical value ranges of the IQA metrics that are most commonly associated with specific subjective image quality ratings. It is important to note that these thresholds are derived from practical recommendations and may require adjustment depending on the specific application domain.

Table 7.

A comparison of image quality metrics with interpretation and threshold information.

These data will be useful for verifying the correctness of the automation process, which is critical for optimizing the amount of data transmitted within the system.

A key aspect of pausing or terminating the data stream is the definition of a quality criterion for the reconstructed thumbnail—its quality must be sufficiently high to allow for a meaningful content evaluation by the operator. This criterion is defined as the presence of at least three stabilization points, where each point corresponds to a quality metric value computed for a specific number of samples, and all three values fall within a predefined range. This range is determined by the mean absolute deviation (MAD) for each metric, and the stabilization points must occur within a defined sampling interval.

The iteration process is terminated if, for at least three consecutive thumbnails, the quality metric value Q remains within a range no wider than the MAD value corresponding to the given metric.

where

- —quality metric values for three consecutive samples.

- —mean absolute deviation for the given quality metric:

- MADBRISQUE = 17.117;

- MADPIQE = 12.996;

- MADNIMA = 0.467;

- MADARNIQA = 0.144;

- MADHyperIQA = 0.02.

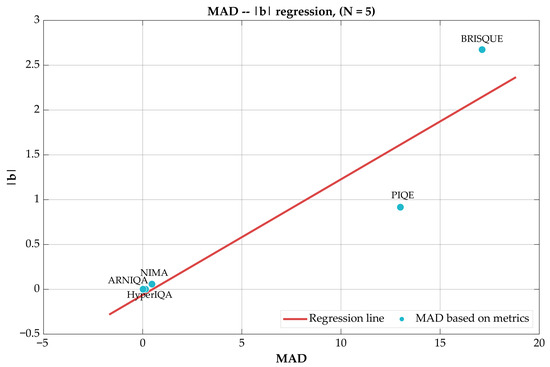

The thumbnail corresponding to the last stabilization point is selected as the final input image for further processing. Pearson’s correlations r between the MAD and convergence rate were analyzed:

- For the full dataset, r = 0.924, p = 0.025, and N = 5 metrics.

- For the trimmed dataset (excluding extreme cases), r = 0.833, and p = 0.080.

The strong positive correlation (r = 0.924, p < 0.05) confirms that metrics with higher mean absolute deviation exhibit proportionally faster convergence rates, analogous to Hooke’s law in mechanics: greater initial displacement from equilibrium generates a stronger restorative force.

The linear scale in Figure 11 reveals that the correlation r = 0.924 is largely dominated by the two high MAD metrics (based on BRISQUE and PIQE), while the three low MAD metrics (based on ARNIQA, HyperIQA, NIMA) are “crowded” to the left. This suggests that the relationship between MAD and is bimodal. In this case, we have two modes with different “stronger restorative forces”. The most useful class of metrics in practice is the one that ensures faster convergence (represented by BRISQUE and PIQE).

Figure 11.

The relation between MAD and .

To verify the correctness of the stabilization detection mechanism, some simulations were conducted using a test dataset, with quality metrics computed every 10,000 samples. Since the early stages of reconstruction often introduce noise-like artifacts, an additional metric—the Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR)—was calculated. For this purpose, the reference image was defined as the thumbnail reconstructed using all available samples.

The selected results from the simulation are presented in Table 8. The evaluation was performed on a dataset of 140 forest images, with sampling intervals of 10,000 pixels.

Table 8.

Image quality assessment results for various IQA metrics.

To evaluate the robustness of the three-point stabilization criterion, a confusion matrix analysis was performed on the complete test dataset of 140 forest images. The ground truth was defined as follows:

- Reference image: Full reconstruction using all available samples (2,073,600 pixels).

- Acceptability threshold: A thumbnail is considered “ready for operator review” if it achieves the following: a PSNR ≥ 28 dB (relative to full reconstruction) AND SSIM ≥ 0.85 (relative to full reconstruction).

These thresholds were established based on pilot studies with human operators, where thumbnails meeting both criteria were consistently rated as “sufficient for wildlife identification and scene analysis.”

The classification outcomes were interpreted as follows:

- True Positive (TP): Stabilization detected AND thumbnail meets the quality threshold;

- False Positive (FP): Stabilization detected BUT thumbnail quality insufficient;

- True Negative (TN): No stabilization detected AND thumbnail quality insufficient;

- False Negative (FN): No stabilization detected BUT thumbnail quality already sufficient.

Table 9 presents the confusion matrix results for all five evaluated IQA metrics, with performance measured across sensitivity (recall), specificity, overall accuracy, and F1-score.

Table 9.

Confusion matrix analysis for stabilization detection determined for 140 images.

The classification metrics used during the analysis are as follows:

- Sensitivity (Recall) = —reflecting the ability to detect when a thumbnail is ready;

- Specificity = —reflecting the ability to avoid premature stopping;

- Accuracy = —reflecting the overall correctness;

- F1-score = —used as an alternative overall index.

The confusion matrix shows that the PIQE achieves a sensitivity of 94% with only a 4.3% false negative rate, confirming the robustness of the three-point MAD-based stopping rule for operational implementation on low-computing systems.

In summary, the proposed photo trap ecosystem integrates the cost-effective hardware and the optimized algorithms to ensure efficient image transmission and processing in remote forest environments. By leveraging modular components and scalable communication protocols, the system achieves a balance between performance, energy consumption, and operational cost, laying the foundation for sustainable and autonomous wildlife monitoring.

Furthermore, the PIQE metric—identified through simulation and analytical comparison as the most suitable for early-stage image quality evaluation—stands out due to its unique balance of computational efficiency, perceptual relevance, and rapid stabilization. Unlike deep learning-based indicators, the PIQE performs reliably on resource-constrained platforms such as the Raspberry Pi 3, with computation times under one second for thumbnail images. Its sensitivity to blur and blocky distortions aligns well with the artifacts introduced by Monte Carlo sampling, making it particularly effective for assessing low-resolution reconstructions.

The PIQE metric also demonstrates a favorable convergence rate and low mean absolute deviation, enabling the robust detection of stabilization points during iterative image reconstruction. These properties ensure that the PIQE can serve as a practical and responsive criterion for terminating data transmission, minimizing bandwidth usage while preserving sufficient image clarity for the operator’s decisions.

In addition to the stabilization point-based criterion, the PIQE metric was further verified during real-world field tests. This step is essential to confirm the practical applicability and robustness of the proposed optimization strategy.

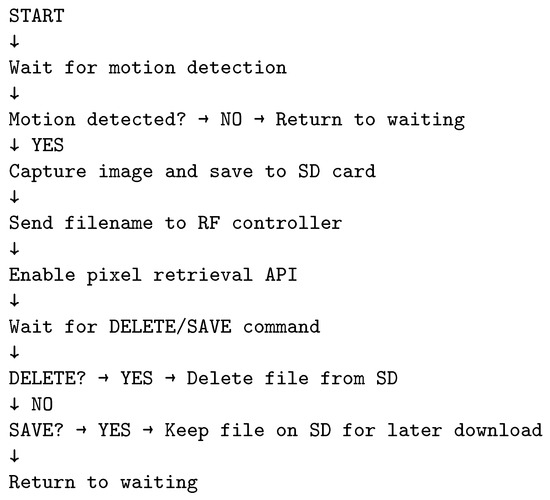

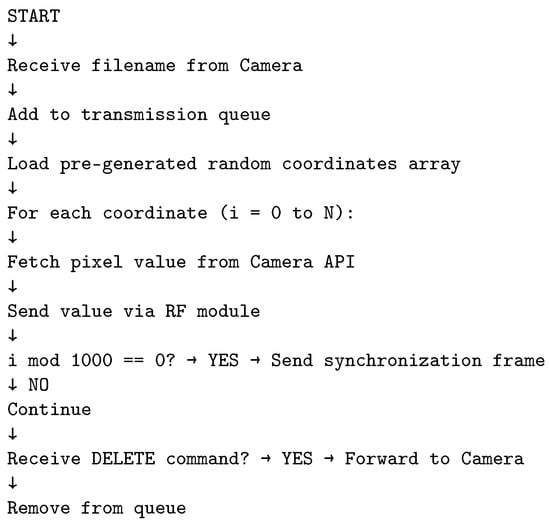

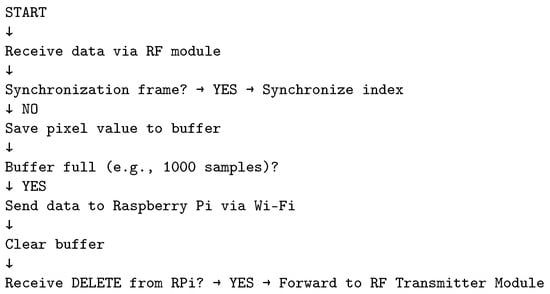

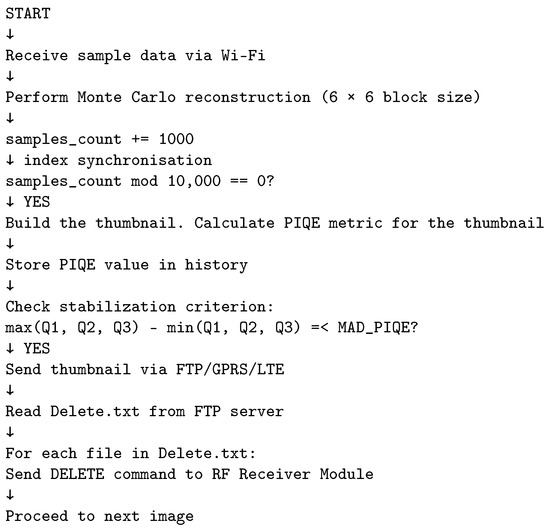

The described algorithms and transmission interruption criteria allow for the definition of a pseudo-code for the entire IoT ecosystem (Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14 and Figure 15).

Figure 12.

Pseudo-code for camera.

Figure 13.

Pseudo-code for RF transmitter module.

Figure 14.

Pseudo-code for RF receiver module.

Figure 15.

Pseudo-code for IoT gateway module (Raspberry Pi).

Monte Carlo sampling exhibits inherent error resilience through statistical averaging:

- Statistical Error Correction: Each 6 × 6-pixel block accumulates multiple random samples during transmission; the block value computed as naturally averages out erroneous samples; for K samples per block, a single transmission error impacts only 1/K of the final value.

- Graceful Degradation: Lost packets reduce sample count but do not corrupt existing data. At stabilization (180,000–230,000 samples), an average of 3–4 samples/block provides 25–33% error dilution without ECC overhead.

- Synchronization Resilience: Periodic sync frames (every 1000 samples) enable recovery from desynchronization; the loss of a single sync frame affects a maximum of 1000 samples before the next resynchronization point.

3. Tests in Real Environment

For practical testing in a real-world environment, the following system configuration was used:

- One ESP32-CAM with a motion sensor, based on the project available at https://www.makerguides.com/motion-activated-esp32-cam (accessed on 11 September 2025); an API was added to enable the pixel’s value retrieval over Wi-Fi based on the coordinates provided in the query.

- Two Wi-Fi Heltec LoRa 32(V3) microcontrollers, ESP32S3 + SX1262 LoRa Node All-in-One.

- Two nRF24L01 modules with a 16 dB directional antenna.

- One Raspberry Pi 3+ microcomputer.

- A Samsung M51 smartphone used as a GPRS/LTE USB modem.

- An Asus TUF 15 laptop serving as the operator’s station.

It is worth noting that forest environments are characterized by a very low level of electromagnetic interference compared to urban areas. This makes them a specific and favorable testing ground for long-range RF communications, as the probability of packet loss due to external interference is significantly reduced.

For long-range RF transmission, either the built-in LoRa module or nRF24L01 was used interchangeably. A frame size compatible with the maximum payload of 32 bytes (for nRF24L01) was adopted. Data streaming over a long-range RF was implemented using the fragments of original demonstration programs for the Arduino platform, provided by the LoRa module manufacturer and the Arduino community for nRF24L01.

The simplification of the transmission protocol was based on the following assumptions:

- Images were transmitted in grayscale.

- Pixel coordinates were not transmitted; the pixel location was inferred from the sample index corresponding to a position in a pre-generated array of random coordinates stored on both controllers, replacing the use of pseudorandom number generators.

- Every 1000 transmitted samples, a synchronization frame was sent containing the sequence 0, 255, 0, 255, 0, 255, followed by the index of the next coordinate in the random array and padding to reach 32 bytes.

The data transfer cycle followed the concept illustrated in Figure 5 and was conducted as follows:

- Upon the detection of motion, an image was saved locally to an SD card. The filename was transmitted via Wi-Fi to the first controller handling long-range communication. Filenames were queued and stored on this controller. A web API was implemented to retrieve pixel values based on coordinates and the filename and to delete images by name.

- The first controller, connected via Wi-Fi, managed the queue of filenames, retrieved and transmitted random samples to the second controller, sent the synchronization frames, forwarded the delete commands to the camera, and updated the queue.

- The second microcontroller received data, synchronized with the first controller, and forwarded the collection of samples along with the image name and coordinates to the Raspberry Pi. If the delete command was received from the Raspberry Pi unit, it was relayed to the first controller. Local communication was handled via Wi-Fi using a web API hosted on the Raspberry Pi.

- The Raspberry Pi executed the thumbnail reconstruction algorithm once the stabilization criterion for the PIQE metric was met (the other metrics were used for comparison only), as defined in the previous sections. Each thumbnail was sent to the operator’s station via FTP. After each transmission, the Raspberry Pi read the Delete.txt file containing the list of images to be removed, then connected to the FTP server via GPRS, transmitted the data, read the file, and closed the connection.

- The operator reviewed the thumbnails and created a list of files to be deleted.

During testing, the full-resolution image transfer was omitted, assuming the two possible strategies as follows:

- The systematic deletion of images from the camera’s SD card would allow the thumbnails to be retained and retrieved during periodic battery replacement.

- The second file (Save.txt) could be added to list images for full transfer; this would require extending the test software to continue data transmission until all samples are sent.

The transmission parameters are summarized in Table 10 for the LoRa standard and in Table 11 for the nRF24L01 module.

Table 10.

The LoRa transmission parameters.

Table 11.

The nRF24L01 transmission parameters.

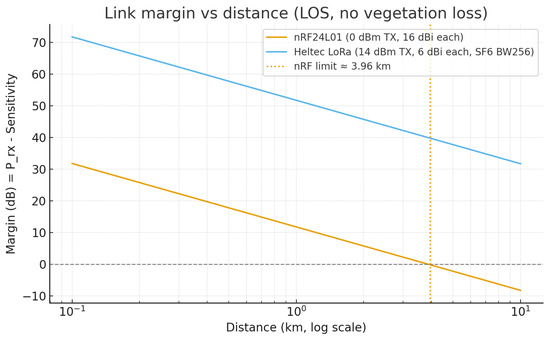

The objective of this analysis is to compare the link margin behavior of two wireless systems as a function of distance under line-of-sight (LOS) conditions [26]. The first system uses an nRF24L01 transceiver, produced by Nordic Semiconductors, Trondheim, Norway, at 2.45 GHz with 16 dBi directional antennas, while the second is a Heltec LoRa module operating at 868 MHz with 6 dBi omnidirectional antennas and spreading factor , bandwidth kHz, and coding rate . A fixed system loss of dB and negligible environmental loss ( dB) are assumed. The received power is computed using the classical link budget relation:

where denotes the transmit power in dBm, and are antenna gains in dBi, and is the free-space path loss given by the following:

The link margin M is then expressed as follows:

where S is the receiver sensitivity in dBm. For each system, was evaluated over logarithmically spaced distances in the range –10 km. The resulting plot (Figure 16) is presented in a semilogarithmic scale (logarithmic x-axis), which linearizes the dependence of path loss on distance and allows for the easy visual identification of threshold points where .

Figure 16.

Link margin vs. distance—semilog analysis for nRF24L01 (2.45 GHz, 16 dBi) and Heltec LoRa (868 MHz, SF6 BW256, 6 dBi).

nRF24L01:

At km,

Heltec LoRa:

At km,

A link margin greater than 6–10 dB is generally considered a comfort zone, providing sufficient robustness against short-term fading, antenna misalignment, and moderate environmental attenuation. In this context,

- for the nRF24L01 system, a 1 km link yields a margin of approximately 12 dB, indicating a stable and reliable 2 Mbps connection under LOS conditions;

- for the Heltec LoRa system, the 3 km link maintains a margin exceeding 40 dB, signifying a very strong and resilient link with substantial fade margin, even in partially obstructed or forested terrain.

Consequently, 1 km for nRF24L01 and 3 km for the Heltec LoRa configuration can be regarded as comfort distances, where both systems operate well within their reliable performance envelope.

In the conducted tests, various distances between devices transmitting data over a long-range wireless network were considered. A synchronization indicator was introduced, which accounts for all instances where the data contained in the transmitted synchronization frame deviated from the estimated values on the receiver side. Such inconsistencies typically occurred during the transmission of the final batch of samples and were attributed to the data loss caused by strong radio interference or changes in radio wave propagation conditions.

Table 12 illustrates the percentage of the Monte Carlo experiments (for 1000 images) for which the stopping criteria (derived using the MAD values for the selected metrics) were determined in various ranges of the randomly chosen samples (K is the number of the selected samples).

Table 12.

The percentages of samples for which the threshold was detected for the assumed range of the number of randomly chosen samples (K).

Analyzing the presented results, the high risk of the influence of noise may be observed for the NIMA metric (low number of the randomly selected samples K), whereas the use of the BRISQUE metric would require the longest transmission (in over half of the cases, the stopping criterion was achieved for over 300,000 samples). Therefore, the domination of the middle ranges, observed for the PIQE metric, demonstrates a good balance between the required transmission time and the reliability of the obtained results, considering the further image analysis.

This study did not take into account the formal limitations associated with LoRa transmission. Future work will include incorporating ETSI duty cycle constraints into the testing process to ensure compliance with regulatory requirements. For a single randomly selected frame, the results are presented in Table 13 for the LoRa standard and in Table 14 for the nRF24L01 module.

Table 13.

A comparison of IQA methods depending on the LoRa transmission distance.

Table 14.

A comparison of IQA methods for short transmission distances (NRF24l01).

To develop a long-term energy balance, field observations that take into account the observation context are recommended. Only with information about the number of acquired images could they be linked to ETSI fill factor limits for LoRa, and then energy consumption for both transmission modes could be recorded and compared. However, Table 15 and Table 16 present the energy consumption measurements for a single miniature transmission and a 1 s idle measurement (measured using a USB logger with a measurement error of 1%). In the case of LoRa transmission, there is a clear negative impact of long transmission times on energy consumption.

Table 15.

Power and energy consumption of selected devices in idle (no deep sleep) state for 1 s.

Table 16.

Energy comparison for LoRa (110 s) and NRF24 (7 s) transmission durations.

To quantitatively evaluate the performance trade-offs between the proposed Monte Carlo sampling algorithm and the conventional progressive JPEG standard, a comparative analysis was conducted under identical transmission conditions. Table 17 summarizes the key performance metrics for transmitting a 320 × 180-pixel grayscale thumbnail over two distinct RF links: a high-throughput, short-range nRF24L01 link at 1 km and a low-throughput, long-range LoRa link at 3 km. The analysis considers both ideal (zero packet loss) and realistic high-BER (15–25% packet loss) scenarios, characteristic of forested environments. Metrics include the total data transmitted (including protocol overhead), transmission time, and resilience to packet loss, providing a comprehensive assessment of each method’s suitability for resource-constrained IoT applications.

Table 17.

A comparison of the Monte Carlo thumbnail and progressive JPEG transmission.

The results presented in Table 17 clearly demonstrate the superiority of the Monte Carlo algorithm in unreliable, high-BER environments, despite its lower data compression efficiency.

The 170,000 samples mentioned in Table 17 refer to the usable pixels used for reconstruction. The actual transmission also includes synchronization overhead (5440 bytes), totaling 175,440 bytes. Based on this, the actual throughput was calculated: for LoRa (3 km), 175,440 bytes/102 s = 1.72 KB/s (13.75 kb/s); for nRF24L01 (1 km), 175,440 bytes/7 s = 25.06 KB/s (200.5 kb/s). While progressive JPEG achieves a 3.9-fold reduction in transmission time under ideal conditions due to its superior compression ratio (1.8 s vs. 7.2 s on nRF24L01), its performance catastrophically degrades with increasing packet loss. At a 15% packet loss rate, JPEG’s reliance on ARQ retransmissions extends its transmission time to 8–12 s, exceeding that achieved for the Monte Carlo method.

Most importantly, the Monte Carlo algorithm’s transmission time remains constant and predictable (7.2 s on nRF24L01, 102 s on LoRa) regardless of packet loss, as its inherent statistical error correction obviates the need for retransmissions. This graceful degradation ensures 100% success in delivering a usable, acceptable-quality thumbnail. In contrast, progressive JPEG faces a significant risk of complete transmission failure due to header corruption. Therefore, for IoT deployments where link stability cannot be guaranteed, the predictability, resilience, and energy efficiency of the Monte Carlo approach provide a decisive advantage over conventional compression-based methods.

The conducted field tests confirmed the feasibility of the proposed system under real-world conditions. Both the LoRa and nRF24L01 modules demonstrated reliable performance across varying distances, with the PIQE emerging as the most practical metric for an early-stage image quality evaluation. The modular architecture and the adaptive transmission protocol proved to be effective in minimizing data volume while maintaining sufficient image clarity for the operator’s decisions.

4. Conclusions and Future Work

This paper presents a novel, cost-efficient photo trap ecosystem designed for remote forest monitoring using low-bandwidth communication. The integration of Monte Carlo sampling for image reconstruction, combined with no-reference (blind) IQA metrics, enables adaptive data transmission and decision-making on edge devices. The system successfully balances image quality, energy efficiency, and transmission cost, making it suitable for deployment in infrastructure-limited environments.

Future work will focus on the following:

- Extending the system to support full-resolution image transfer upon the operator’s request;

- Incorporating machine learning models for automated content recognition and classification;

- Evaluating the system’s scalability across larger networks of camera traps;

- Investigating regulatory constraints and optimizing duty cycles for LoRa-based deployments;

- Analyzing the impact of compression methods on increasing performance.

Considering the rapid development of artificial intelligence systems, one of the most promising directions of further investigation seems to be the integration of lightweight machine learning models, e.g., MobileNet for automatic wildlife classification at the edge, towards semantic-aware transmission prioritization.

Another important direction of further research may be related to the analysis of relations between image quality metrics, used for the considered application, and changes in the SNR and packet loss ratio. Since the application of full-reference metrics in the wildlife environment is troublesome, this analysis should be focused on the use of “blind” IQA metrics based only on the received image data.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.L. and B.M.; methodology, P.L. and K.O.; software, P.L.; validation, P.L. and B.M.; formal analysis, P.L.; investigation, P.L.; resources, P.L.; data curation, P.L.; writing—original draft preparation, P.L.; writing—review and editing, P.L., B.M. and K.O.; visualization, P.L. and K.O.; supervision, B.M.; project administration, P.L.; funding acquisition, P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from one of the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

Piotr Lech would like to thank the authorities of the Faculty of Telecommunications, Computer Science and Electrical Engineering at Bydgoszcz University of Science and Technology in Poland for their cooperation during his scientific internship in Bydgoszcz, thanks to which the research used to create this publication was carried out.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| API | Application Programming Interface |

| ARNIQA | leArning distoRtion maNifold for Image Quality Assessment |

| ARQ | Automatic Repeat reQuest |

| AVR | Advanced Virtual RISC |

| BER | Bit Error Rate |

| BRISQUE | Blind/Referenceless Image Spatial Quality Evaluator |

| BW | Bandwidth |

| CAM | Camera |

| CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| CR | Coding Rate |

| CSS | Chirp Spread Spectrum |

| CIF | Common Intermediate Format |

| CUDA | Compute Unified Device Architecture |

| EBCOT | Embedded Block Coding with Optimal Truncation |

| ECC | Error Correction Code |

| ESP32 | Espressif Systems 32-bit microcontroller |

| ETSI | European Telecommunications Standards Institute |

| EU | European Union |

| FPS | Frames Per Second |

| FSPL | Free-Space Path Loss |

| FTP | File Transfer Protocol |

| GFSK | Gaussian Frequency Shift Keying |

| GPRS | General Packet Radio Service |

| GPU | Graphics Processing Unit |

| GSM | Global System for Mobile Communications |

| HD | High Definition |

| ID | Identifier |

| IoT | Internet of Things |

| IIoT | Industrial Internet of Things |

| ISM (band) | Industrial, scientific, and medical (band) |

| IQA | Image Quality Assessment |

| JPEG | Joint Photographic Experts Group |

| LoRa | Long-Range (transmission) |

| LOS | Line of Sight |

| LPWAN | Low-Power Wide-Area Network |

| LX6 | Xtensa LX6 |

| MAD | Mean Absolute Deviation |

| MOS | Mean Opinion Score |

| MIPS | Million Instructions Per Second |

| NIMA | Neural Image Assessment |

| NIQE | Naturalness Image Quality Evaluator |

| NSS | Natural Scene Statistics |

| NR IQA | No-Reference Image Quality Assessment |

| PAL | Phase Alternating Line |

| PIQE | Perception-based Image Quality Evaluator |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| PUSH | Push Notification or Command |

| RF | Radio Frequency |

| SD | Secure Digital |

| SF | Spreading Factor |

| SPIHT | Set Partitioning In Hierarchical Trees |

| TUF | The Ultimate Force |

| USB | Universal Serial Bus |

| USD | United States Dollar |

References

- Hemalatha, A.; Vijayakumar, J.; Mervin Paul Raj, M. A Real-Time Monitoring System for Soilless Agriculture Tomato Plants Using Sensors and the Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Emerging Research in Computational Science (ICERCS), Coimbatore, India, 7–9 December 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaparro B., F.; Pérez, M.; Mendez, D. A Communication Framework for Image Transmission through LPWAN Technology. Electronics 2022, 11, 1764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staikopoulos, A.; Kanakaris, V.; Papakostas, G.A. Image Transmission via LoRa Networks—A Survey. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Image, Vision and Computing (ICIVC), Beijing, China, 10–12 July 2020; pp. 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edirisinghe, S.; Sachinda, I. Image Transmission Using LoRa for Edge Learning. SSRN Electron. J. 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey Vaz, F.A.; Sangeetha, T.; Sai Leksmi, S.U.; Dhanusha, A. Performance Analysis of nRF24L01 Wireless Module. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Data Intelligence and Cognitive Informatics (ICDICI), Tirunelveli, India, 18–20 November 2024; pp. 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kollarik, M. Low Power Wireless Communication System: Development of an Expandable Wireless Communication System Based on ATMEGASL and nRF24L01+ for the Deployment in Laboratories. Ph.D. Thesis, Technische Universität Wien, Vienna, Austria, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lova Raju, K.; Vijayaraghavan, V. A Self-Powered, Real-Time, NRF24L01 IoT-Based Cloud-Enabled Service for Smart Agriculture Decision-Making System. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2022, 124, 207–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, J.; Pan, Y.; Hou, Z.Y.; Zhang, R. Research on the System of Image Acquisition and Wireless Transmission. Appl. Mech. Mater. 2014, 668, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, S.; Yan, Q.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, C.; Ge, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. Blindly Assess Image Quality in the Wild Guided by a Self-Adaptive Hyper Network. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 3664–3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M. Blind Image Quality Assessment: A Brief Survey. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2312.16551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Sturtz, J.; Qingge, L. Progress in Blind Image Quality Assessment: A Brief Review. Mathematics 2023, 11, 2766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okarma, K.; Lech, P. Monte Carlo Based Algorithm for Fast Preliminary Video Analysis. In Computational Science—ICCS 2008; Lecture Notes in Computer Science (LNCS); Bubak, M., van Albada, G.D., Dongarra, J., Sloot, P.M.A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 5101, pp. 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sha, H.; Dong, M.; Luo, Q.; Lu, M.; Chen, H.; Ma, Z. Towards Loss-Resilient Image Coding for Unstable Satellite Networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 27 February–2 March 2025; Volume 39, pp. 12506–12514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, Y.; Yap, K.H.; Chau, L.P. Bitstream-corrupted JPEG images are restorable: Two-stage compensation and alignment framework for image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 9979–9988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Tomar, A.; Hazra, A. Edge Computing for Industry 5.0: Fundamental, Applications, and Research Challenges. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 19070–19093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sodiya, E.O.; Umoga, U.J.; Obaigbena, A.; Jacks, B.S.; Ugwuanyi, E.D.; Daraojimba, A.I.; Lottu, O.A. Current State and Prospects of Edge Computing Within the Internet of Things (IoT) Ecosystem. Int. J. Sci. Res. Arch. 2024, 11, 1863–1873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, H.V.; Tran, T.G.; Le, C.D.; Le, A.D.; Vo, H.B. Benchmarking Jetson Edge Devices with an End-to-End Video-Based Anomaly Detection System. In Advances in Information and Communication, Proceedings of the Future of Information and Communication Conference (FICC), Berlin, Germany, 4–5 April 2024; Lecture Notes in Networks and Systems, (LNNS); Arai, K., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 920, pp. 358–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizinski, T.; Cao, X. Design, Implementation and Performance of an Edge Computing Prototype Using Raspberry Pis. In Proceedings of the IEEE 12th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 26–29 January 2022; pp. 0592–0601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okarma, K.; Lech, P. Application of Monte Carlo Preliminary Image Analysis and Classification Method for Automatic Reservation of Parking Space. Mach. Graph. Vis. 2009, 18, 439–452. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Mo, J. IQA-PyTorch: PyTorch Toolbox for Image Quality Assessment. 2022. Available online: https://github.com/chaofengc/IQA-PyTorch (accessed on 11 September 2025).

- Agnolucci, L.; Galteri, L.; Bertini, M.; Del Bimbo, A. ARNIQA: Learning Distortion Manifold for Image Quality Assessment. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 3–8 January 2024; pp. 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Moorthy, A.K.; Bovik, A.C. No-Reference Image Quality Assessment in the Spatial Domain. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2012, 21, 4695–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Talebi, H.; Milanfar, P. NIMA: Neural image assessment. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 3998–4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venkatanath, N.; Praneeth, D.; Maruthi Chandrasekhar, B.; Channappayya, S.S.; Medasani, S.S. Blind Image Quality Evaluation Using Perception Based Features. In Proceedings of the 21st National Conference on Communications (NCC), Mumbai, India, 27 February–1 March 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montgomery, D.C.; Peck, E.A.; Vining, G.G. Introduction to Linear Regression Analysis, 6th ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Vougioukas, S.; Anastassiu, H.; Regen, C.; Zude, M. Influence of foliage on radio path losses (PLs) for wireless sensor network (WSN) planning in orchards. Biosyst. Eng. 2013, 114, 454–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).