Abstract

In dense crowds and complex electromagnetic environments of metro stations, UWB-based seamless payment suffers from limited positioning accuracy and insufficient stability. A promising solution is to incorporate the vision modality, thereby enhancing localization robustness through cross-modal trajectory alignment. Nevertheless, high similarity among passenger trajectories, modality imbalance between vision and UWB, and UWB drift in crowded conditions collectively pose substantial challenges to trajectory alignment in metro stations. To address these issues, this paper proposes a multi-modal trajectory progressive alignment algorithm under modality imbalance. Specifically, a progressive alignment mechanism is introduced, which leverages the alignment probabilities from previous time steps to exploit the temporal continuity of trajectories, thereby gradually increasing confidence in alignments while mitigating the uncertainty of individual matches. In addition, contrastive learning with the InfoNCE loss is employed to enhance the model’s ability to learn from scarce but critical positive samples and to ensure stable matching on the UWB modality. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method consistently outperforms baseline approaches in both off-peak and peak periods, with its matching error rate reduced by 68% compared to the baseline methods during peak periods.

1. Introduction

An increasing number of smartphones, including those produced by Apple, Xiaomi, and Samsung, are now equipped with Ultra-Wideband (UWB) technology [1,2]. Beyond data transmission, UWB supports high-accuracy localization by measuring the propagation time or time differences of wideband pulse signals [3]. This capability makes it well-suited for seamless identity authentication and interactive applications [4]. In public transportation, UWB-based seamless payment enables passengers to pass through gates without taking out their phones, unlocking screens, or scanning QR codes. The gate automatically authenticates and opens, creating a smooth and natural passage process [5]. Compared with QR-code-based payment, this approach improves efficiency and convenience while reducing operational delays. As adoption grows, it can help eliminate gate congestion during peak hours.

However, while UWB can deliver high-accuracy localization in line-of-sight (LOS) or weak-reflection environments, its performance degrades significantly in metro stations—where dense crowds and reflective structures are common. In these environments, human bodies absorb electromagnetic waves and block direct paths. Such non-line-of-sight (NLOS) propagation increases signal path length and instability, reducing localization accuracy [6]. Moreover, metal structures in metro stations act as strong reflectors and scatterers, generating severe multipath effects that interfere with the TOA- and TDOA-based ranging models [7]. As a result, UWB localization accuracy can degrade substantially. Empirical studies show that UWB localization errors in complex environments can range from 12 to 130 cm, far exceeding the typical 7–25 cm error range in simpler settings [8]. In subway seamless payment scenarios, such errors may cause misidentification between passengers standing only 30–50 cm apart at the gate, since UWB tags are usually embedded in handheld devices rather than located at the user’s body center, introducing additional spatial offset and localization ambiguity. Therefore, centimeter-level localization accuracy is essential to ensure the reliable operation of subway seamless payment systems.

To mitigate the accuracy limitations of single-modality UWB localization, vision-based localization offers a complementary solution. It leverages optical features such as clothing textures and body contours for detection and tracking [9]. Unlike UWB, it is immune to electromagnetic interference and provides stable trajectory outputs in metro stations. By aligning UWB trajectories of tagged passengers with their corresponding vision trajectories, the system can correct UWB drift and distinguish overlapping trajectories. This multimodal integration compensates for UWB limitations and improves system robustness.

Nevertheless, cross-modal trajectory alignment in metro stations poses two key challenges:

- High similarity among passenger trajectories: In metro stations, passenger movement paths are relatively fixed, with many trajectories overlapping, caused by groups traveling together or dense flows. Combined with UWB drift, this leads to a high risk of confusion in cross-modal alignment, thereby limiting the success rate of single matching attempts.

- Severe modality imbalance between vision and UWB: In real-world transportation scenarios, all passengers generate vision trajectories, but only a small subset carries UWB tags. This imbalance yields an overwhelming majority of negative samples in training, causing the model to overemphasize mismatches while neglecting scarce but critical true associations.

To overcome these challenges, this paper introduces two strategies tailored for subway seamless payment scenarios:

- Prior knowledge-guided progressive trajectory alignment: The alignment probability from the previous time step is used as prior information to guide and constrain the current attention module. This design leverages the temporal continuity of trajectories, progressively increasing confidence in alignments while mitigating the uncertainty of individual matches.

- Contrastive learning for modality imbalance mitigation: The contrastive learning with InfoNCE loss is employed to deal with the severe modality imbalance. By maximizing the similarity of true UWB–Vision pairs while contrasting them against a large set of negatives, the model is encouraged to learn from scarce yet critical associations, thereby promoting stable matching on the UWB modality.

Based on these strategies, we propose a progressive multi-modal trajectory alignment algorithm under modality imbalance. It should be noted that this work focuses exclusively on the trajectory alignment stage, without addressing subsequent multimodal trajectory fusion-based positioning or payment processes. Experiments in both peak and off-peak subway scenarios show that our method consistently outperforms baseline approaches.

2. Related Work

Accurate cross-modal data association is a prerequisite for multimodal data fusion. Traditionally, when multimodal spatiotemporal features can be projected into a shared metric space, they can be matched based on distances in this space. For instance, 3D point correspondences are used to calibrate extrinsic parameters of LiDAR and cameras, aligning coordinate systems and enabling cross-modal alignment [10]. In multimodal sensing, sensor displacements caused by vibration or aging may lead to misaligned coordinate systems. To correct this, classical methods such as the Iterative Closest Point (ICP) or Normal Distributions Transform (NDT) [11] iteratively minimize spatial errors between contours [12] or segmentation features [13] of the same target captured by different sensors, thereby achieving precise feature alignment. Similarly, in UWB and vision fusion, Peng et al. [14] applied the Hungarian algorithm to minimize total errors between UWB and vision coordinates, thereby associating localization results. For UWB and vision trajectory alignment, Fang et al. [15] and Sun et al. [16] achieved trajectory alignment by minimizing the total error between UWB and vision trajectories.

Recently, deep learning has been widely applied to cross-modal alignment for its strong feature extraction and nonlinear modeling capabilities. A common approach is to design feature extractors for each modality, project them into a common space to enable cross-modal similarity computation, or employ matching networks to associate extracted features. For instance, Cao et al. [17] used separate extractors for RF and vision features, followed by a cross-modal metric learning model for human identity matching. Cai et al. [18] proposed an uncertainty-guided fusion method to project thermal and mmWave features into a shared space. Liu et al. [19] aligned RF and vision features via a joint representation module. For trajectory data matching, Dai et al. [20] extracted comparative features from mmWave radar and IMU trajectories and applied bipartite graph matching based on cosine similarity.

With the successful application of the Transformer architecture in multimodal data processing, many recent approaches employ attention mechanisms to model inter-modality and temporal interactions, yielding more discriminative feature representations. For single-modality multi-object tracking, TrackFormer [21] and TransTrack [22] take the target features of the previous frame as Query, and the feature map of the current frame as Key and Value, enhancing temporal consistency via attention, facilitating subsequent alignment. Miah et al. [23] proposed TWiX, which uses a Transformer to model the interactions between trajectories and achieves cross-time-step matching between past and future trajectories of each object. It concatenates past–future trajectory pairs and leverages motion predictability as an implicit prior, which differs from our cross-modal setting involving heterogeneous noise distributions and unaligned observations; moreover, it performs association between all tracklet pairs, which is computationally prohibitive in dense crowd scenarios such as metro stations. In cross-modal scenarios, feature extraction networks are typically designed separately for each modality to capture their distinct characteristics, and cross-attention modules are then used to explicitly model inter-modality interactions, where one modality’s features often serve as Key and Value and another’s as Query, thereby deriving more discriminative and fused feature representations. In this way, Tuzcuoğlu et al. [24] achieved feature fusion between visible and thermal infrared images, Bai et al. [25] realized feature fusion of LiDAR and images, and Pang et al. [26] achieved Camera-And-Radar feature fusion. In addition, Fang et al. [27] proposed another idea, concatenating visible and thermal infrared features together and simultaneously using them as Query, Key, and Value to achieve bidirectional feature fusion.

However, in these methods, cross-modal targets are usually balanced in number, relatively sparse, and suffer from limited trajectory drift. This differs significantly from metro stations, where dense crowds, UWB drift, and modality imbalance create unique challenges.

Meanwhile, it is worth noting that beyond trajectory-level optimization, researchers have also explored communication-layer optimization techniques—such as reconfigurable intelligent surfaces (RIS)—to mitigate channel distortion and enhance multi-link reliability [28,29]. In addition, event-triggered and adaptive learning mechanisms can be further considered for deployment to improve the overall robustness of complex systems under uncertainty [30,31,32]. These studies collectively indicate that measures at the communication layer and the system layer can be considered to help improve the stability of system operation.

3. Methodology

3.1. Scene Description

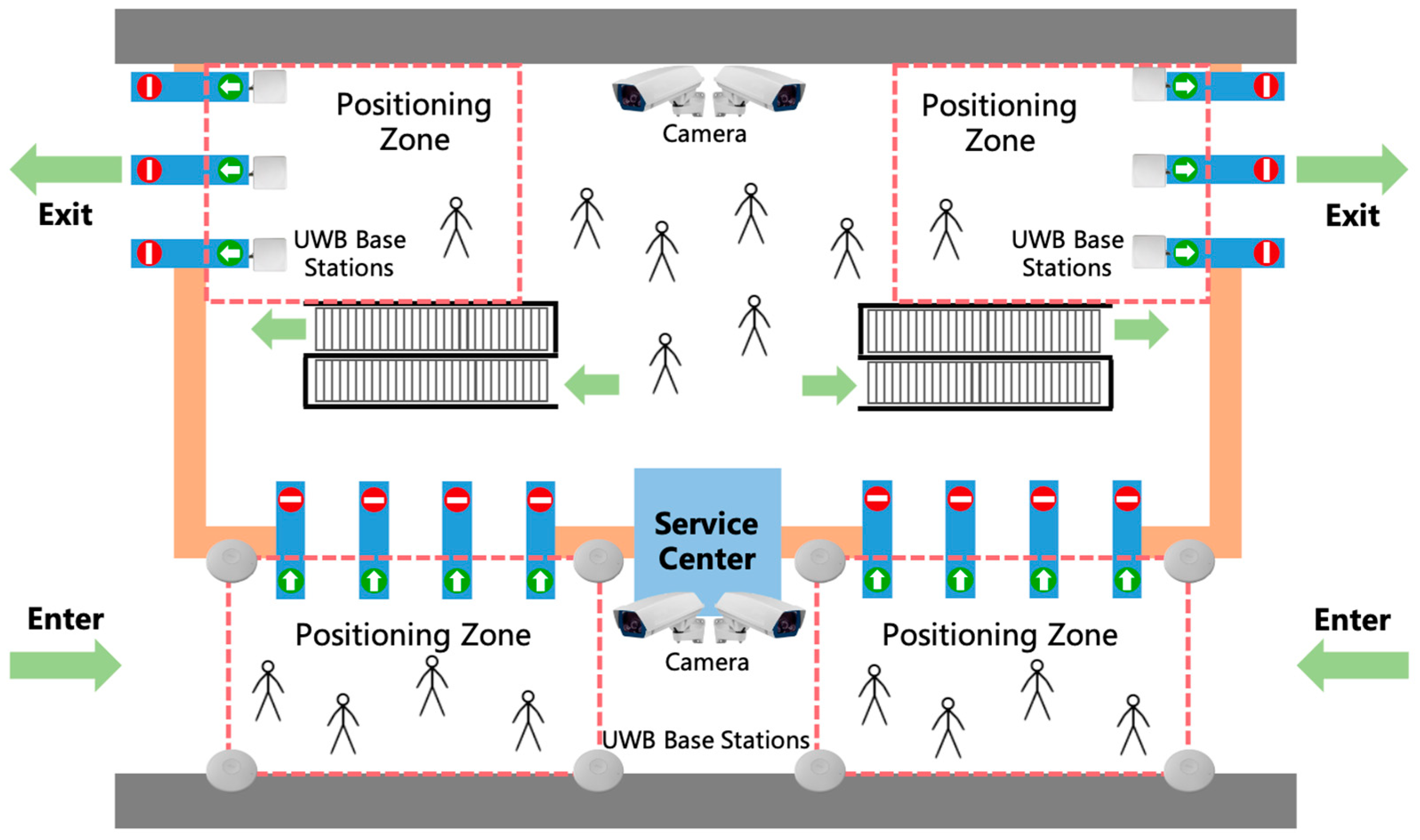

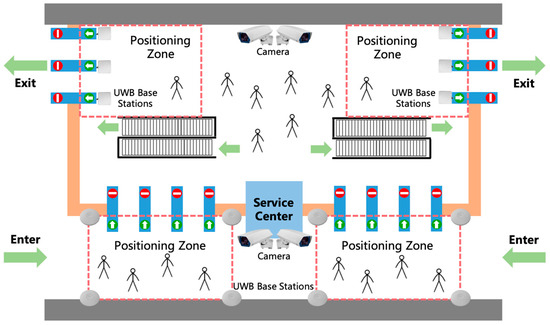

The overall workflow of seamless payment in metro stations is shown in Figure 1. To mitigate the potential drift of a single UWB trajectory, a dedicated positioning zone is established near station entrances and exits. Within this zone, both UWB and vision trajectories are collected simultaneously. A trajectory alignment algorithm then links the two modalities, leveraging their complementary strengths to improve robustness. Once passenger identity and position are consistently verified, the gate automatically authenticates and opens, creating a smooth and natural passage.

Figure 1.

Seamless payment scenario in metro station. The blue bars represent the gates, and the red-and-green markers on them indicate the gates’ direction of passage.

For privacy protection, the system does not collect high-resolution facial images or other biometric data, making it infeasible to associate passenger identities with UWB tags through face recognition. Consequently, correspondence across modalities must be established exclusively through trajectory alignment within the positioning zone.

3.2. Trajectory Coordinate Unification

UWB and vision trajectories originate from different coordinate systems, coordinate unification is required before trajectory alignment. In many metro stations, UWB base stations are deployed in an approximately collinear layout along the gates, or only a single camera is available within the positioning zone, which limits the system to providing two-dimensional passenger positions. Therefore, to ensure algorithmic generalizability across different stations, the vertical dimension is excluded, and trajectory alignment is conducted in a unified two-dimensional ground coordinate system.

3.2.1. UWB Data Processing

In metro stations, UWB tags transmit pulse signals that are received by multiple base stations, which then estimate tag positions using either Time of Flight (ToF) or Time Difference of Arrival (TDoA) to each base station. As mentioned earlier, only two-dimensional ground-plane coordinates are retained for trajectory alignment. So, the vertical component is discarded.

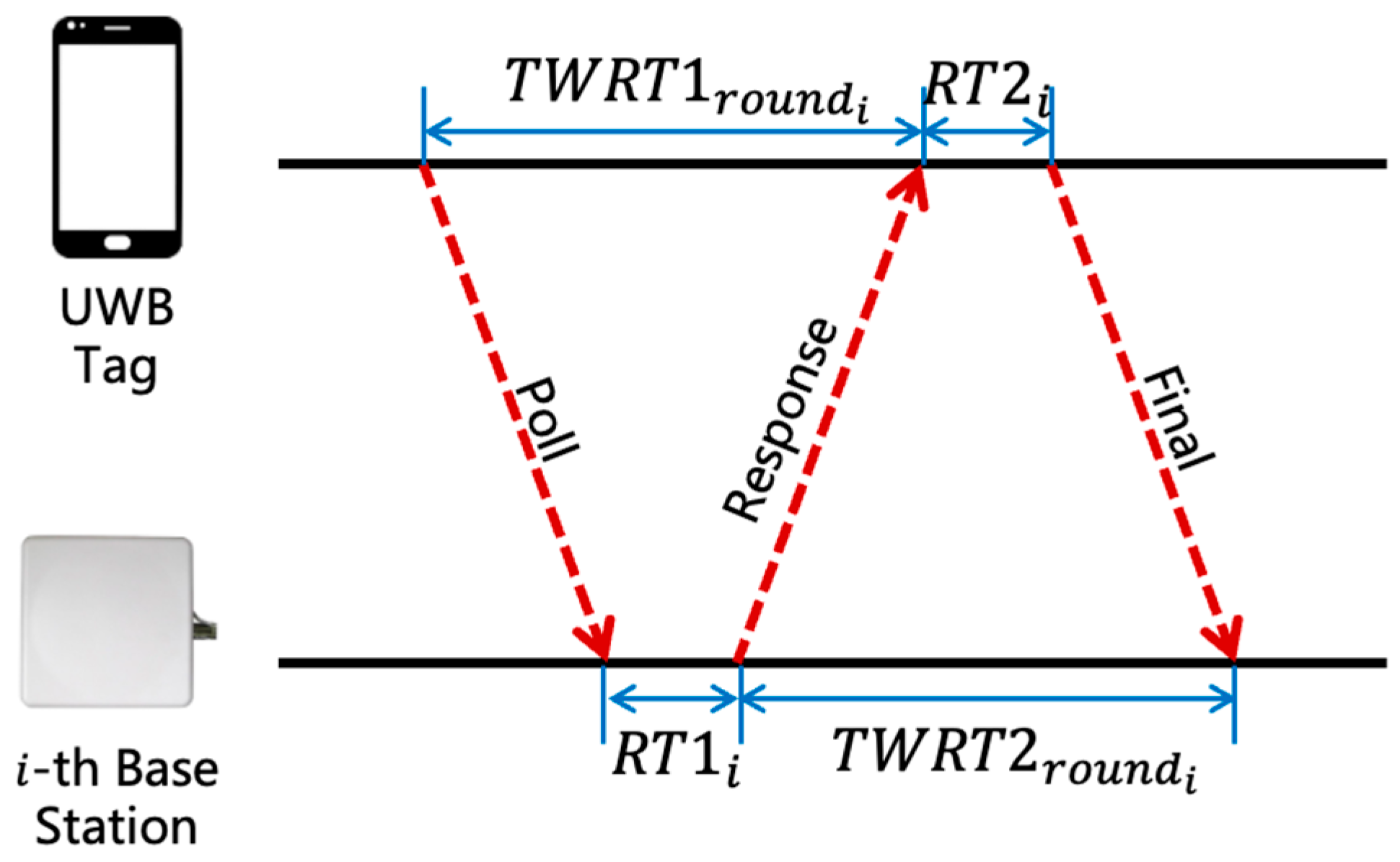

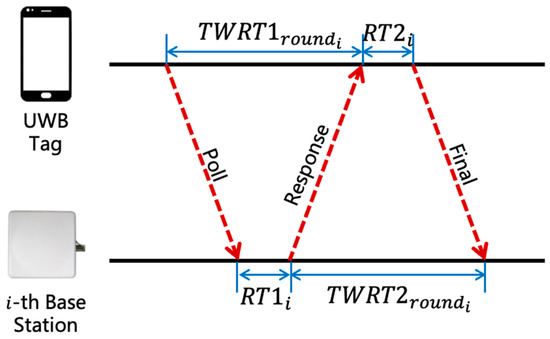

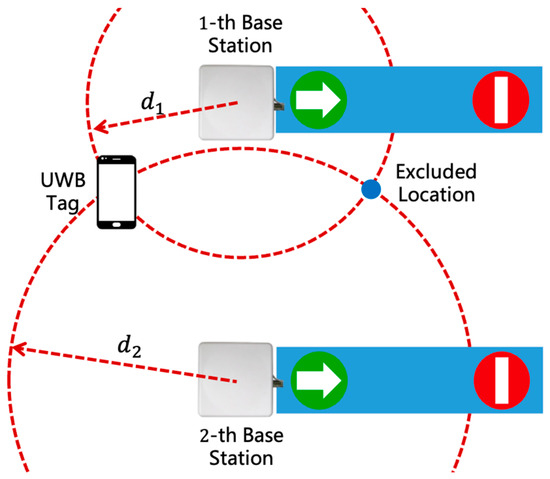

When UWB base stations are deployed in an approximately collinear layout along the gates—resulting in limited geometric diversity—ToF-based localization is adopted. This method determines the distance between the tag and each base station through two-way time of arrival measurements, as shown in Figure 2, and does not require precise synchronization between stations and tags.

Figure 2.

Signal propagation time calculations in ToF-based localization.

The distance between the tag and the -th base station can be expressed as:

where and are the two-way return time and and are the response times of the base station and tag, respectively; denotes the speed of light.

The position of the tag can then be obtained by solving:

where are the coordinates of the -th base station.

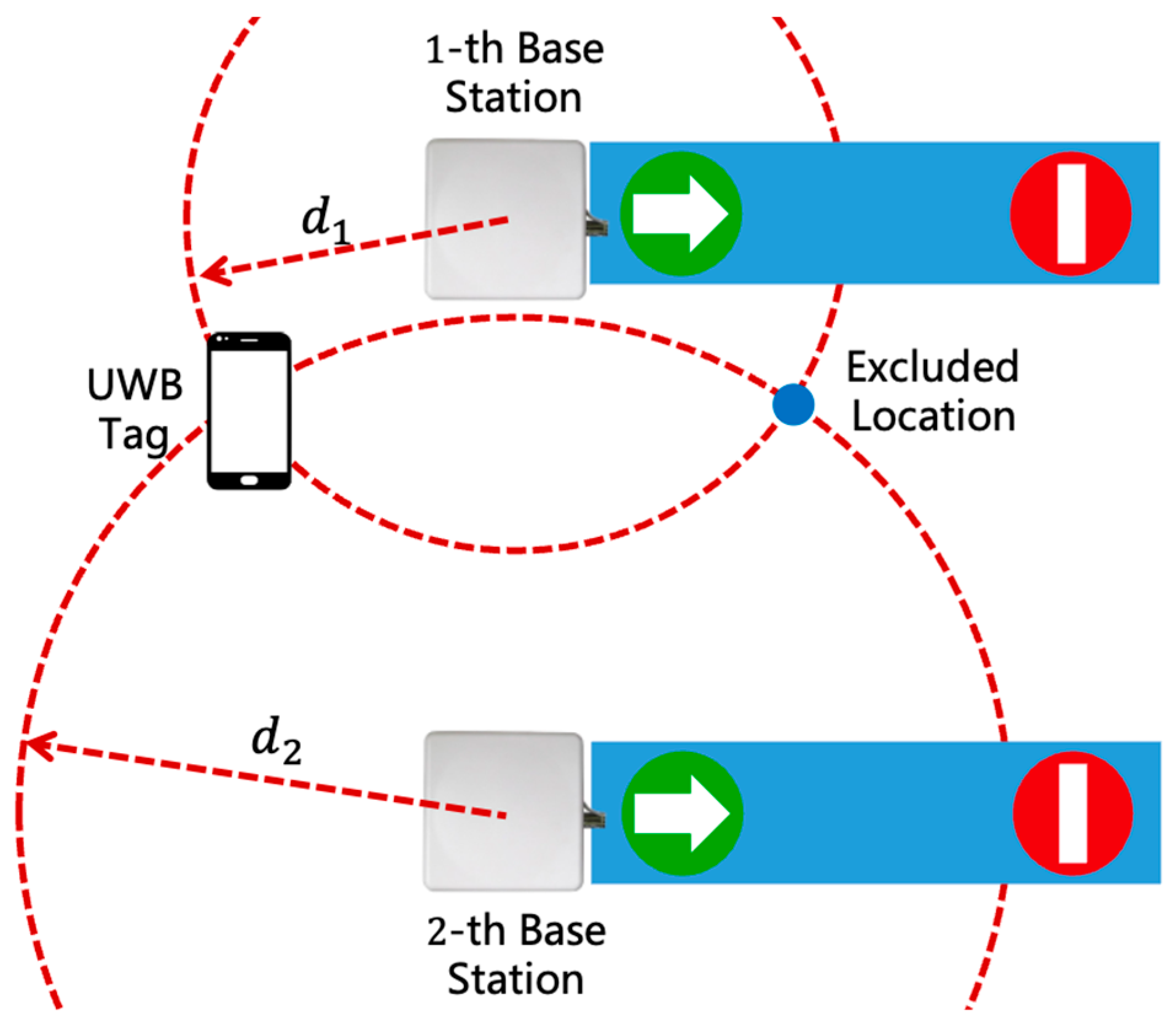

Since only two base stations are available, two intersection points can be derived from the equations above, as shown in Figure 3. Given that passengers always appear on one side of the gate, the valid position is selected based on the known side constraint.

Figure 3.

ToF-based localization in metro gate scenarios. The blue bars represent the gates, and the red-and-green markers on them indicate the gates’ direction of passage.

For independently deployed UWB base stations, TDoA-based localization is used, which is particularly well-suited for scenarios with a high density of tags. This method determines the tag position by measuring the time difference of arrival between precisely synchronized stations. In this case, the stations must maintain precise clock synchronization, while the tags do not. The tag position can be obtained by solving the following equations:

where represent the signal arrival time at the -th station.

Since only the horizontal position is of interest, an additional fifth station is unnecessary. Although the base stations are typically installed on the ceiling and thus approximately coplanar, which makes the estimation of the vertical coordinate less stable, using four synchronized base stations still enables a reliable estimation of the horizontal position. By solving for and discarding the vertical component , the final two-dimensional coordinate can be obtained—usually yielding better accuracy than directly solving the tag position by assuming a fixed height.

However, due to the effects of NLOS propagation, multipath interference, and measurement noise discussed earlier, the aforementioned localization results may exhibit noticeable drift. For instance, in TDoA-based localization, the hyperbolic surfaces derived from range differences may fail to intersect at a single point because of measurement errors, leading to unstable or even spurious position estimates. To alleviate this problem, when the number of stations only meets the minimum requirement (i.e., four stations for TDoA), this study employs the Least Squares (LS) method to determine the final position by minimizing the sum of squared residuals of all range measurements. In scenarios where more stations are available than the minimum requirement, a residual-based Weighted Least Squares (WLS) approach [33] is further adopted. By incorporating redundant ranging information and assigning weights based on residual magnitudes, this method enhances the overall robustness and accuracy of localization, yielding the final position estimate . Additionally, for systematic bias caused by fixed NLOS propagation paths, the range bias of each station is obtained through on-site calibration during deployment and pre-compensated in subsequent positioning.

3.2.2. Vision Data Processing

Vision-based trajectories are obtained using FairMOT [34], a multi-object tracking algorithm optimized for crowded environments with frequent occlusions. FairMOT outputs the bounding boxes of each passenger across frames within a single camera’s field of view. For larger positioning zones requiring multiple cameras, PP-Tracking [35] is further employed to maintain consistent cross-camera tracking.

For each passenger, the bottom-center pixel coordinates of the bounding box are projected into the camera coordinate system as using the intrinsic matrix :

3.2.3. Coordinate Transformation

After preprocessing, UWB and vision trajectories remain in their respective local coordinate systems. To enable cross-modal alignment, both trajectories are transformed into a common global ground-plane coordinate system using rotation matrix and a translation vector :

where is a trajectory point in the local coordinate system of either modality, and is its unified representation in the global system.

3.3. Progressive Alignment of Trajectories

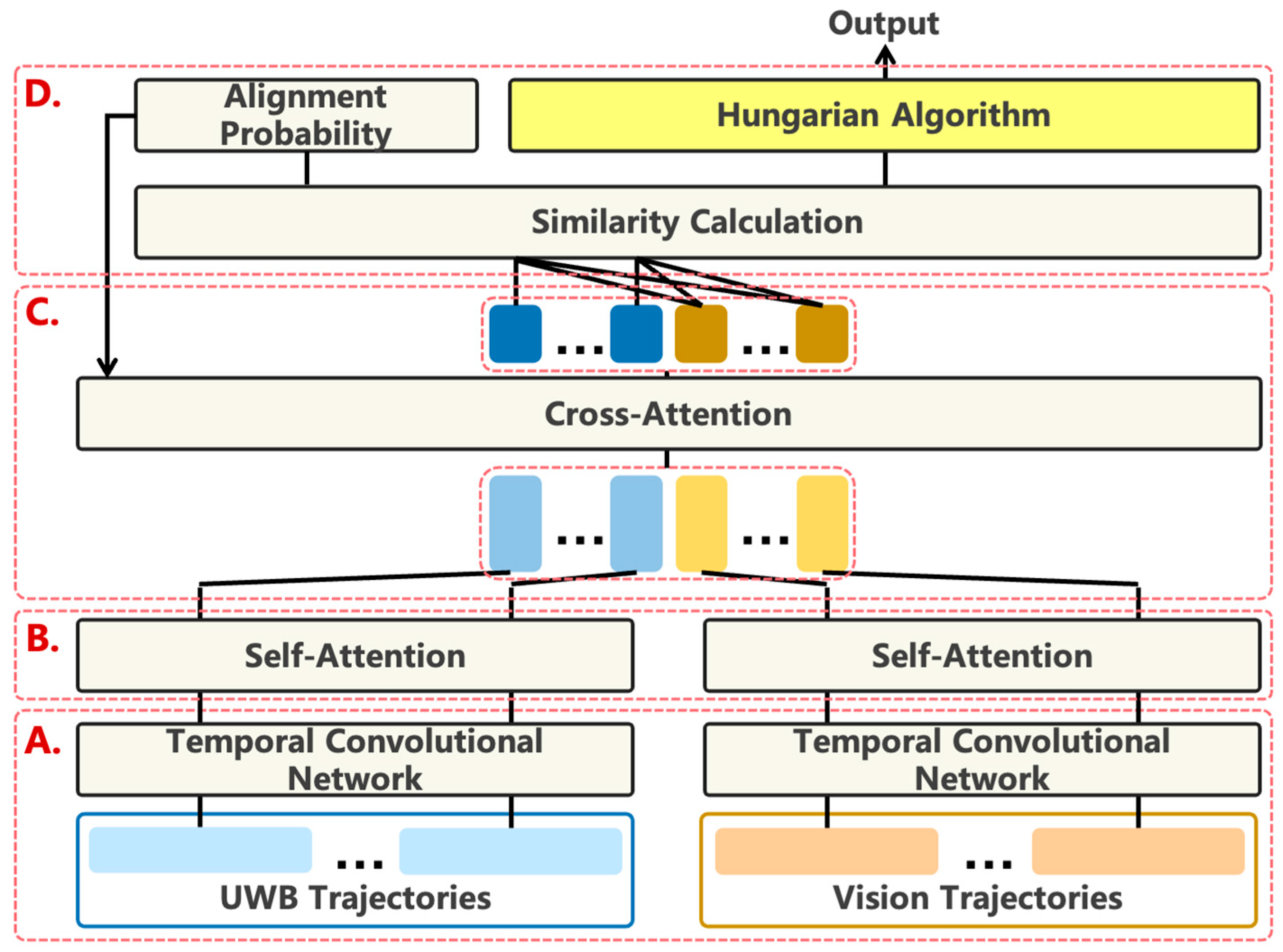

Once passenger positions are obtained, trajectories can be generated through periodic sampling. However, in metro stations, high similarity among passenger trajectories, modality imbalance between vision and UWB, and UWB drift under dense crowds collectively introduce substantial challenges for trajectory alignment. To address these issues, we propose a progressive multimodal trajectory alignment algorithm under modality imbalance, as illustrated in Figure 4. The core idea is to leverage alignment probabilities at time step as priors to guide cross-modal attention at time step , thereby progressively improving confidence in alignments while reducing the uncertainty of individual matches. In addition, the InfoNCE loss [36] is adopted to mitigate modality imbalance, ensuring stable alignments for the critical UWB modality.

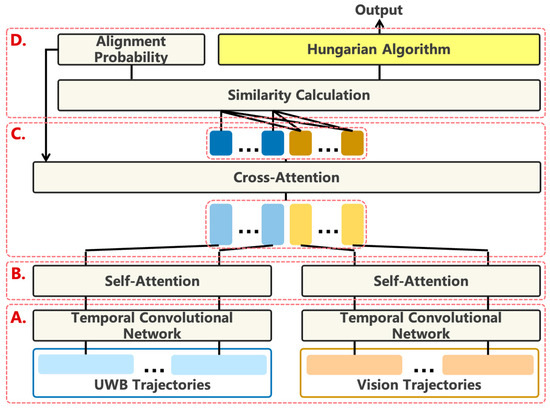

Figure 4.

The overall architecture of the multi-modal trajectory alignment model. (A) Trajectory feature representation and encoding; (B) Self-attention for individual trajectories; (C) Cross-modal attention; (D) Model output and post-processing.

The proposed framework comprises five main components:

- Trajectory feature representation and encoding (Figure 4A): Position and displacement information are fused and normalized, followed by a TCN-based encoder to obtain local temporal features of each trajectory (see Section 3.3.1).

- Self-attention for individual trajectories (Figure 4B): Long-range temporal dependencies within each trajectory are modeled to enhance the representation quality of features (see Section 3.3.2).

- Cross-modal attention (Figure 4C): This module leverages visual-UWB trajectory interactive information and incorporates a prior knowledge-guided attention mechanism to highlight critical associations, thus enhancing trajectory feature representation (see Section 3.3.3).

- Model output and post-processing (Figure 4D): Contrastive learning and Hungarian matching generate final alignment results, while converting alignment probabilities into priors for the next time step (see Section 3.3.4).

- Loss function: The InfoNCE loss is employed to enhance the separability between positive and negative pairs, thereby guiding the model to capture the essential cross-modal alignments (see Section 3.3.5).

3.3.1. Trajectory Feature Representation and Encoding

In multimodal trajectory alignment, the first step is trajectory feature representation and encoding, which lays the foundation for subsequent steps and enables attention mechanisms to effectively capture both intra-trajectory temporal dynamics and inter-modality correlations.

Firstly, to better characterize passenger motion patterns, we incorporate not only absolute position coordinates , but also displacement between consecutive time steps, , , to capture local motion trends. The trajectory sequence is thus represented as:

where denotes the modality of the trajectory.

Then, normalization is applied to prevent disparities in feature magnitudes that may destabilize training. Considering the characteristics of UWB localization errors—mainly transient drift caused by random measurement noise, multipath propagation, and the motion of handheld devices—these errors affect features of different scales in distinct ways. Specifically, the absolute coordinates are meter-level quantities, where the relative influence of UWB errors is minor; in contrast, the displacements are centimeter-level quantities, for which even a single large UWB error may produce an outlier far exceeding the normal range of values. Therefore, we adopt a hybrid normalization strategy tailored to these differing sensitivities:

- For , min–max normalization is applied. Since UWB localization errors have a limited impact on these larger-scale coordinates, this approach effectively preserves the geometric consistency of each trajectory. Moreover, normalization is performed within each network input rather than across the entire dataset, thereby enhancing sample diversity and improving model generalization.

- For , tanh-based normalization is employed to mitigate the effects of transient drift or hand-induced motion perturbations. Given that these displacement features are small in scale but prone to extreme fluctuations, tanh normalization smoothly bounds abnormal values while maintaining sensitivity to normal motion dynamics, thereby preserving richer feature information.

Finally, the normalized sequences are encoded using a Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN), which is applied independently to the UWB and vision modalities, respectively.

This encoding preserves temporal dynamics while generating compact and discriminative feature representations for subsequent self-attention modeling.

3.3.2. Self-Attention for Individual Trajectories

After TCN-based encoding, a Transformer-style self-attention mechanism is employed to model long-range dependencies within each trajectory. Self-attention enables the network to capture complex interactions across the temporal span, thereby enriching the feature representations.

Since noise distributions differ between UWB and vision trajectories, separate self-attention modules are applied to each modality. To maintain temporal consistency, fixed positional encoding based on sine and cosine functions [37] is incorporated into feature sequences to explicitly encode time order.

where is the fixed positional encoding.

Within each self-attention layer, trajectory features are projected into query, key, and value spaces through learnable linear transformations.

where , and are trainable weight matrices.

The updated representation is expressed as:

where attention weights are computed from query–key similarities and normalized using softmax, with denoting the feature dimensionality.

It should be noted that in practical applications, the length of the input trajectory sequence is variable. For vacant positions, padding is adopted to fill the gaps; during the computation process, the mask mechanism is used to set the attention weights of the padded parts to negative infinity, thereby avoiding their interference.

Following self-attention, a feed-forward network (FFN) is added to further enhance nonlinear representation capacity. Residual connections and layer normalization are applied after both attention and FFN blocks to stabilize training, alleviate gradient vanishing, and accelerate convergence.

3.3.3. Cross-Modal Attention

After temporal feature modeling of UWB and vision trajectories, a cross-modal attention mechanism is employed to enhance trajectory representations through inter-modality interactions.

As mentioned earlier, in metro stations, passenger movement paths are highly similar, often leading to confusion in cross-modal alignment. Hence, relying solely on single-step alignments is unreliable. To mitigate this, the first cross-attention layer incorporates a prior knowledge-guided attention mechanism, which leverages the temporal continuity of trajectories to progressively refine alignment confidence while reducing uncertainty.

Formally, the self-attention enhanced UWB and vision features are concatenated as , and projected into query, key, and value spaces via learnable linear transformations.

To integrate historical priors, we extend the standard attention by incorporating the prior probability matrix from the previous time step, (see Section 3.3.4). This is implemented through the Hadamard product (i.e., element-wise product) of and , thereby biasing the model toward alignments consistent with historical priors. This multiplicative design allows the prior knowledge to function as a confidence mask, directly modulating (rather than overriding) the pairwise similarity. High-confidence correspondences from the previous step are amplified, while implausible alignments are suppressed, thereby reducing the risk of confusion among highly similar trajectories. Meanwhile, it preserves the original similarity structure encoded in , thus enabling a seamless integration of historical alignment priors with current observations for more coherent and temporally consistent cross-modal alignment.

It should be emphasized again that we only add such prior knowledge to the attention of the first layer, as that layer’s attention is broad and uninformed [38]. Incorporating the temporal prior at this stage provides essential external guidance to stabilize the early alignment. In contrast, the subsequent layers operate on refined representations that already encode implicit temporal dependencies, so standard attention suffices without additional priors.

For subsequent layers, the standard attention formulation is retained, with padding and masking applied to accommodate sequence-length variability:

Each layer is followed by FFN, residual connections, and layer normalization, consistent with the self-attention design.

3.3.4. Model Output and Post-Processing

Following cross-modal attention, explicit UWB–Vision alignments are established using contrastive learning. For each UWB–Vision trajectory pair, similarity is computed using cosine similarity:

Similarity values approach 1 for strongly associated pairs and −1 for dissimilar ones.

To enforce optimal alignments, we employ the Hungarian algorithm to maximize the global similarity, rather than greedily selecting the highest similarity candidate for each UWB trajectory. To enhance robustness under dense crowding, a similarity threshold can be introduced, and pairs below this threshold are labeled as “unmatched”. This mechanism is crucial for seamless payment, where even a small number of mismatches is intolerable.

To provide priors for the next time step, the UWB-to-Vision similarity matrix is normalized with softmax to yield a probability matrix , which is then expanded to size . Diagonal entries (self-to-self) are set to 1, UWB–UWB and Vision–Vision entries are set to 0, and Vision-to-UWB entries mirror UWB-to-Vision probabilities. At initialization, when no historical priors are available, similarity scores are estimated from the reciprocal of the average trajectory distance across time steps and rescaled via min–max normalization to the range [−0.6, 0.6]. These similarity scores are then converted into probabilities through softmax. The rescaling step stabilizes the value range, while the softmax transformation prevents negative similarity scores from producing negative-times-negative-is-positive effects when combined multiplicatively with . It should be noted that, due to the assignment of ones on the diagonal (self-to-self correspondences), the resulting matrix does not strictly conform to a standard probability matrix. However, since the Transformer attention mechanism applies another softmax operation externally, the overall attention distribution is automatically re-normalized. The detailed construction process of the prior probability matrix is illustrated in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. Construction of the prior probability matrix |

| Require: For initialization: Average trajectory distances across time steps , where ; For non-initialization: Trajectory pair similarities output by the model , where . Ensure: Prior probability matrix . |

| .

If in the initialization phase: For each UWB-vision trajectory pair, compute initial similarity scores: ; ; . : ; Set UWB-to-vision probability:; Set vision-to-UWB probability: ; . |

3.3.5. Loss Function

As previously discussed, UWB–Vision trajectory alignment in metro stations is inherently characterized by severe class imbalance, with negative pairs far outnumbering positive ones, making it challenging for the model to learn discriminative features. To address this, we adopt the InfoNCE loss [36], which maximizes the similarity of positive pairs while contrasting them against a large set of negatives, thereby reinforcing essential cross-modal alignments.

Formally, for a positive pair with similarity value relatively to a set of negative pairs , the loss is formulated as:

where is a temperature parameter.

The overall loss is defined as the mean over all positives:

4. Experiments

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method in dense crowd scenarios, we conducted experiments at multiple metro station entrances in Shenzhen. Passenger trajectory data were collected from 20 March to 27 March 2024, covering several stations to ensure both diversity and representativeness. Since passenger flow varies considerably over time, the data were divided into peak (7:30–9:30 and 17:30–19:30) and off-peak categories to assess the adaptability of the UWB–vision trajectory alignment algorithm under different crowd densities.

Since seamless payment is still in a pilot stage, the number of real users remains limited, leading to sparse UWB trajectories in the collected data. Therefore, we employed the UWB positioning system simulation method proposed by Paszek et al. [39] for data augmentation. Specifically, UWB trajectories were synthetically generated by injecting simulated UWB errors into the original vision trajectories. The final dataset was split into 80% for training and 20% for testing. Importantly, the test set included station entry areas not present in the training set, allowing for a comprehensive evaluation of the model’s cross-scene generalization capability.

4.1. Implementation Details

To support efficient alignment between large-scale vision trajectories and sparse UWB data, for each input to the network, the input consists of 20 UWB trajectories and 100 vision trajectories. In practice, the number of UWB trajectories in the positioning zone may exceed 20, and the number of visual trajectories may also exceed 100. To handle this, UWB trajectories are processed in batches. Within each batch, for every UWB trajectory, the number of candidate vision trajectories is set to . Candidates are selected based on the smallest average trajectory error with respect to the target UWB trajectory.

For trajectory sampling, we considered both the average walking speed and dwell time of passengers within the positioning zone during peak and off-peak periods. The sampling frequency was set to approximately 12.5 Hz, with each trajectory spanning about 5 s, yielding a sequence length of 64 frames. This configuration can effectively capture the typical walking process of passengers.

Regarding the network architecture, a three-layer TCN is first applied to extract local temporal features from trajectories. This is followed by two layers of Self-Attention to model long-range dependencies within each trajectory. To further exploit cross-modal interactions, three layers of Cross-Attention modules are integrated. In particular. Notably, the first Cross-Attention layer incorporates a prior knowledge-guided attention mechanism to emphasize critical association relationships, while the number of attention heads is fixed at 8 to improve feature diversity and robustness.

4.2. Model Performance

Considering that this study primarily focuses on the alignment between visual and UWB trajectories, the experiments aim to evaluate the model’s intrinsic discriminative ability under full alignment conditions, rather than relying on post-processing strategies (such as similarity thresholding) to filter low-confidence results. Therefore, no similarity threshold is applied in the experiments, allowing us to directly assess the model’s capability under open conditions.

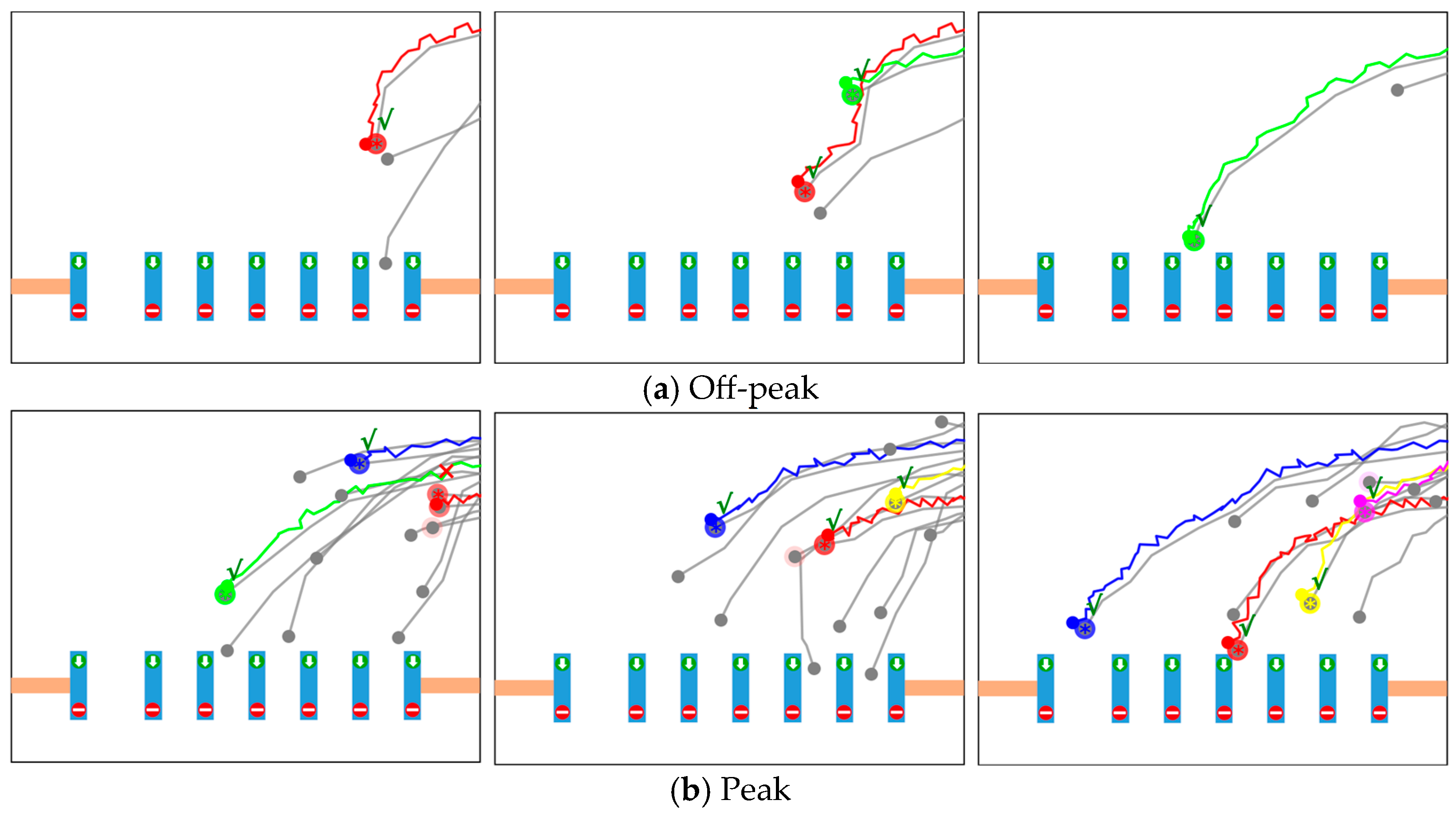

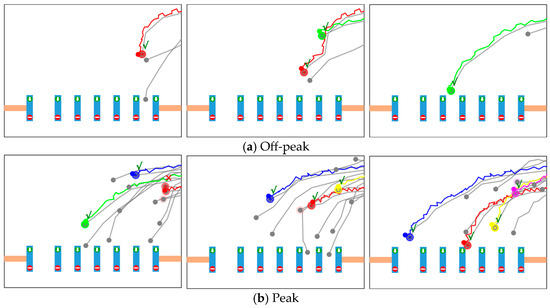

Under this setting, the model’s performance in both peak and off-peak periods at a station entrance scenario is illustrated in Figure 5. In the figure, gray lines represent visual trajectories, while colored lines denote UWB trajectories. The gray and colored dots at the endpoints indicate passenger positions at the current time step. The colored shadows overlaid on the gray points represent the model’s alignment outputs, where the brightness of the color reflects the inter-trajectory similarity score, i.e., the match confidence. In addition, colored “*” markers denote the final match results obtained using the Hungarian algorithm, with “√” indicating a correct match and “×” indicating a mismatch.

Figure 5.

Alignment results of the proposed model. Among them, gray lines and colored lines represent visual trajectories and UWB trajectories respectively; dots represent current-time passenger positions; the brightness of colored shadows on gray dots represent the model’s output similarity scores; colored “*” represent matching results, with the adjacent “√” indicating correct match and “×” indicating mismatch.

As shown in the figure, during off-peak periods, passenger density is low, and the spatial separability among trajectories is clear. The model can accurately establish correct matches shortly after the passengers enter the sensing area, with stable and concentrated confidence distributions. In contrast, during peak periods, the high passenger density, close proximity between trajectories, and visual occlusions—combined with UWB signal drift and tag position offset (as the UWB tag is usually held in hand rather than located at the body center)—make initial alignment substantially more challenging. The model may simultaneously attend to multiple visually similar trajectories, leading to occasional confusion and mismatches, particularly when the inter-passenger distance is less than 30–50 cm. As time progresses and more sequential observations are accumulated, the model progressively distinguishes subtle differences among trajectories and gradually narrows its focus range, eventually achieving a progressive convergence from multiple candidates to the most probable trajectory.

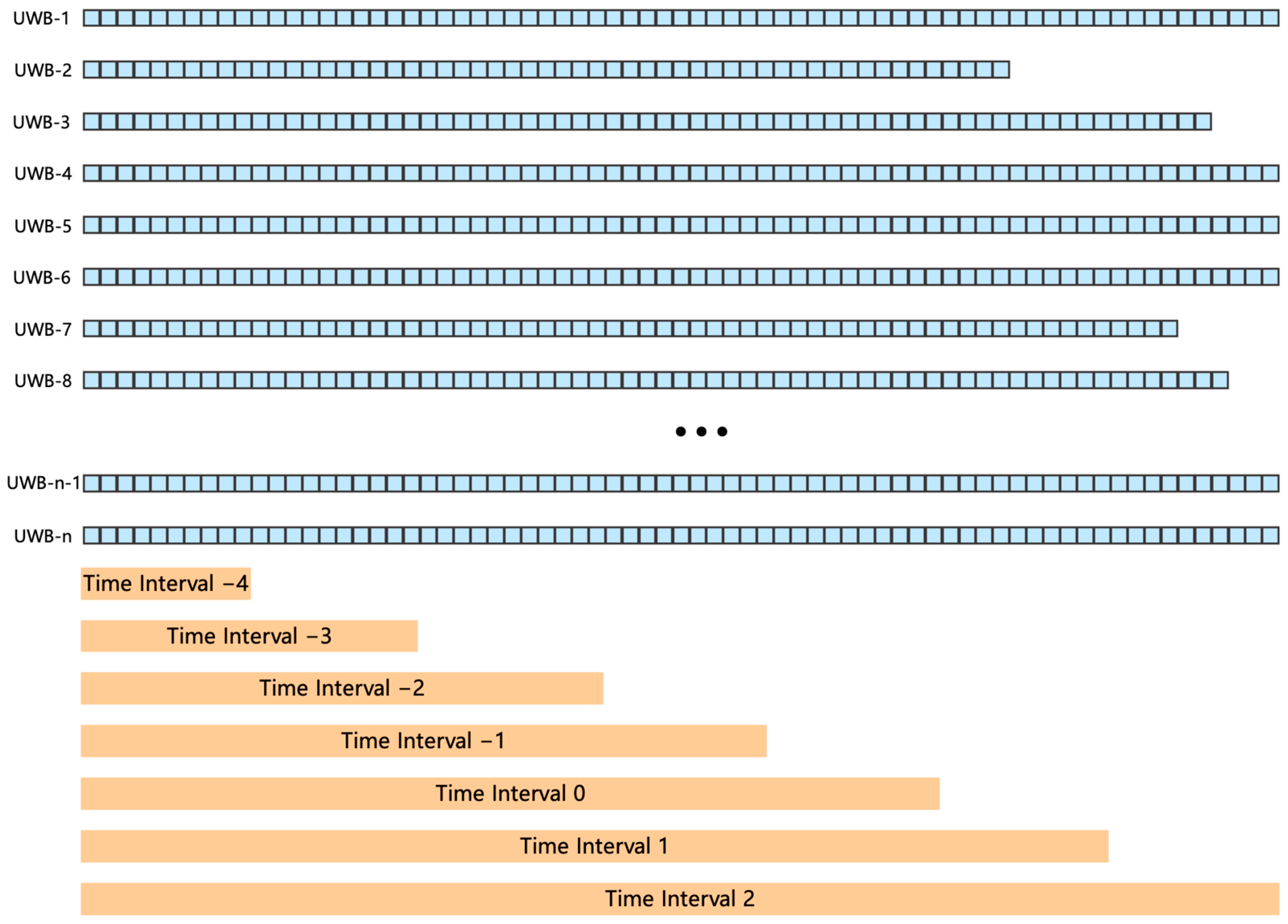

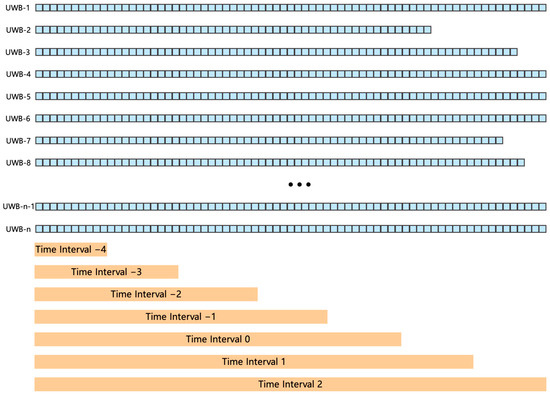

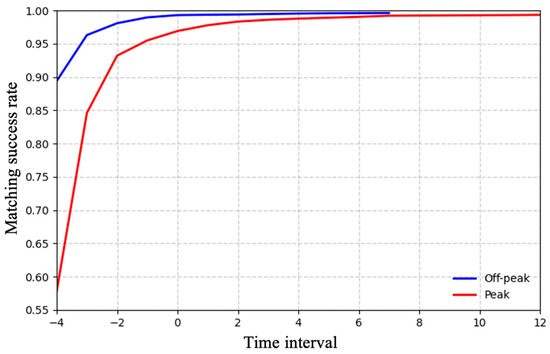

Next, to evaluate the model performance more systematically, we need to calculate the trajectory matching success rate. In this paper, we emphasize the correct alignment of UWB trajectories, as this is crucial for downstream seamless payment applications. Accordingly, accuracy is defined as the proportion of correctly matched UWB trajectories. Meanwhile, to demonstrate the progressive alignment effect of the algorithm, we counted the matching success rate of all UWB trajectories at the end of different time intervals. Here, each Time Interval indicates the portion of the trajectory that has been fed into the network. Considering that the network input length is 64 frames, Time Interval 0 is designated as the reference segment corresponding to the first 64 frames of the trajectory, as shown in Figure 6. Time Intervals are spaced by one second: a positive value means seconds after Time Interval 0 (e.g., Time Interval 2 corresponds to approximately 89 frames), and a negative value means seconds before Time Interval 0 (e.g., Time Interval −4 corresponds to approximately 13 frames). Note that trajectories may vary in length, since passengers may take different amounts of time to pass through the positioning zone. Importantly, during actual network input, frames are always fed in their original temporal order; trajectory alignment is applied here solely to evaluate the matching success rate across sequences of different lengths.

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of time interval division in trajectory alignment.

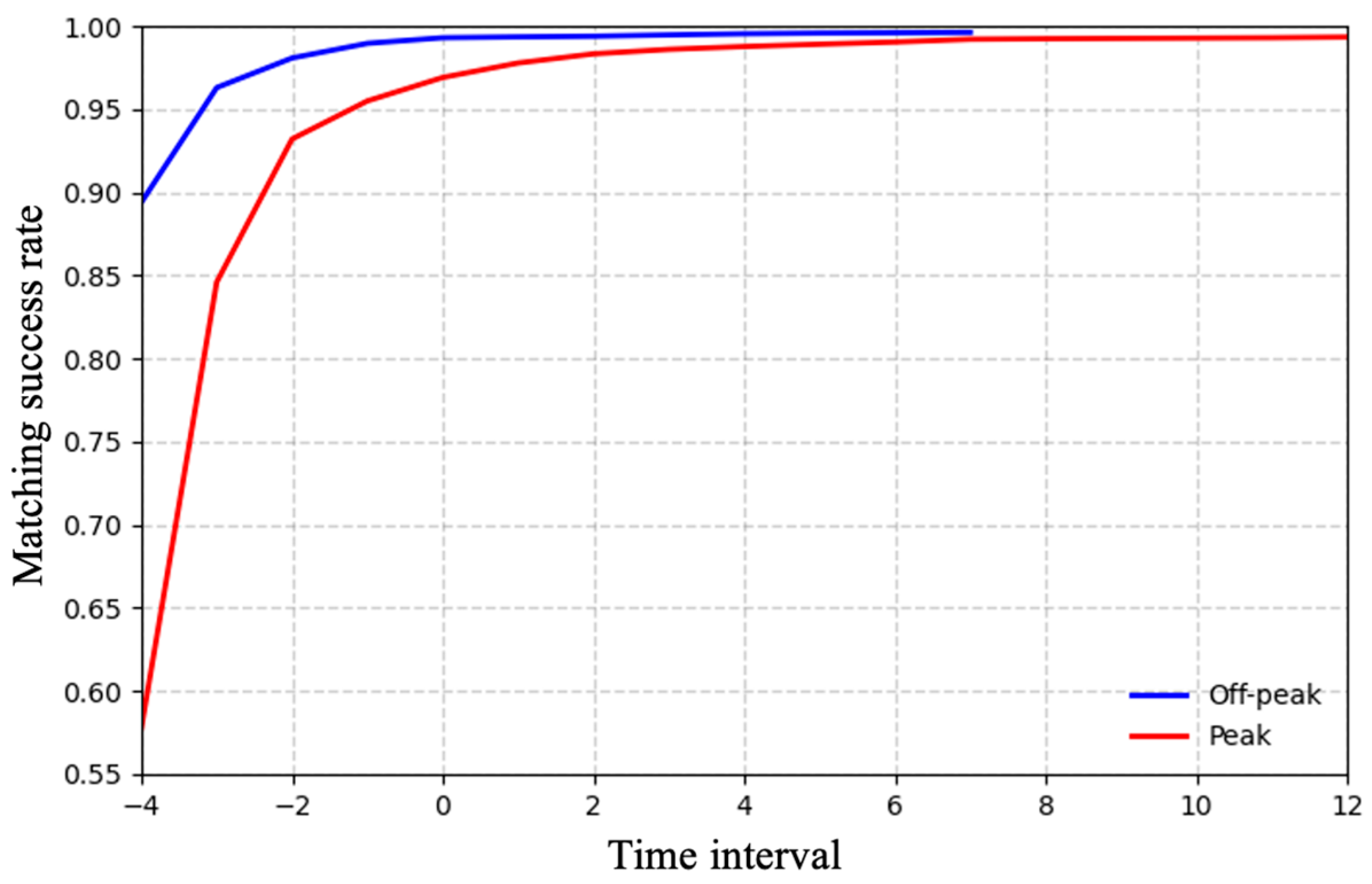

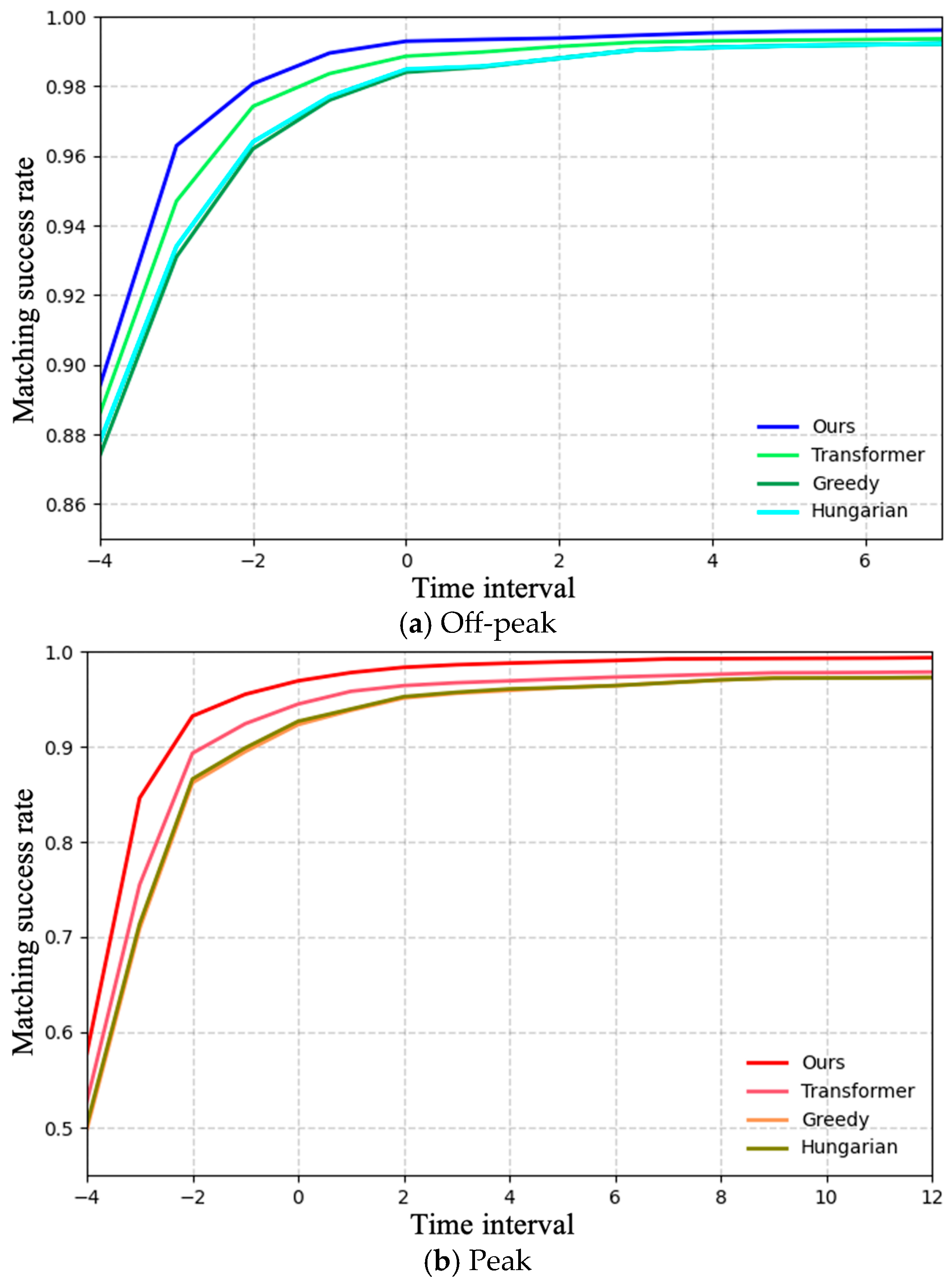

Figure 7 shows the trajectory matching success rate curves for both peak and off-peak scenarios, with time intervals on the horizontal axis and accuracy on the vertical axis. As time progresses, accumulated temporal information enhances the model’s performance, yielding progressively higher accuracy. During peak periods, where trajectory overlap and UWB drift are more severe, accuracy remains lower than in off-peak conditions but gradually converges as more temporal evidence is incorporated.

Figure 7.

The trajectory matching success rate for peak and off-peak scenarios.

A close observation of Figure 7 reveals that accuracy rises most sharply within the first three steps, suggesting that even limited temporal accumulation effectively resolves most mismatches. After approximately six steps (for off-peak periods) or ten steps (for peak periods), the performance stabilizes, with accuracy approaching saturation. These results indicate that the proposed method successfully exploits temporal trajectory features and remains robust in dense crowd environments.

It should be noted that the proposed trajectory alignment algorithm still produces occasional mismatches, primarily because each UWB trajectory is forced to be paired with a visual trajectory. As discussed earlier, to enhance robustness under dense crowding, a similarity threshold can be applied, with pairs falling below this threshold designated as “unmatched”. This mechanism enables additional post-processing for low-confidence associations, thereby ensuring the accuracy of seamless payment billing information. However, this inevitably increases gate-crossing time. An algorithm with a higher matching rate would allow the use of a stricter threshold, reducing the need for post-processing and substantially improving the efficiency of seamless payment. The choice of a specific threshold, however, belongs to the system-level design of the seamless payment workflow and is beyond the scope of this paper.

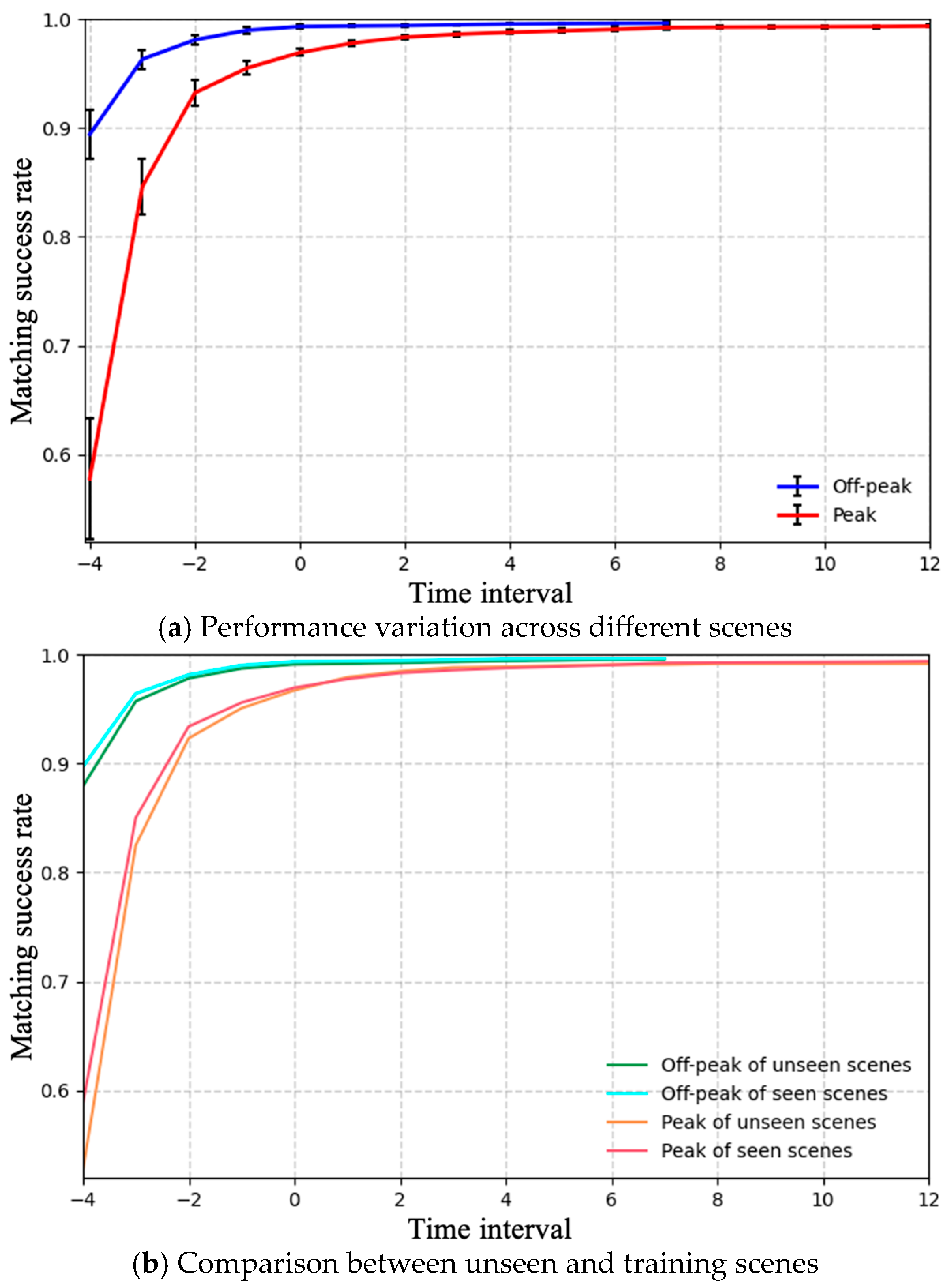

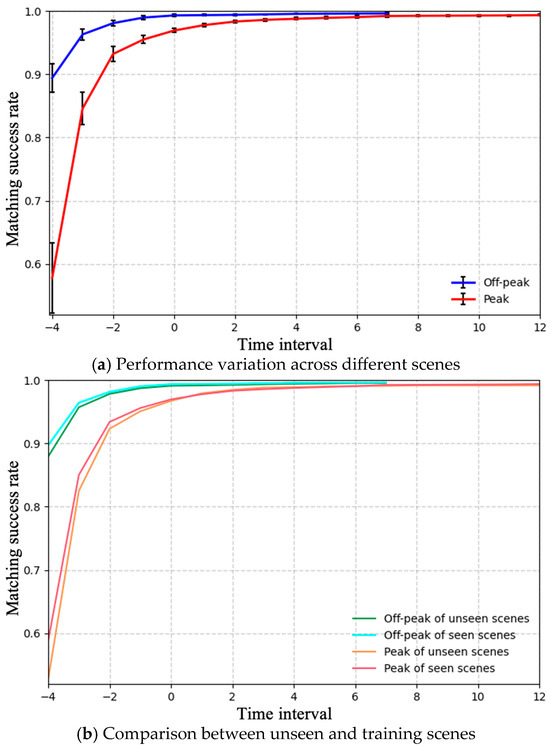

To evaluate the stability and adaptability of the proposed algorithm across different deployment environments, we conducted a systematic assessment of its cross-scene generalization performance. Figure 8 illustrates the statistical distribution of model performance across multiple test scenarios. Figure 8a presents the standard deviation of the matching success rate across scenes, which reflects the consistency and stability of the model’s performance. Figure 8b compares the average performance between unseen scenes (not included in the training data) and seen scenes, thereby quantifying the degree of performance degradation in unseen environments.

Figure 8.

Evaluation of the model’s stability and generalization capability.

As shown in the results, the proposed method achieves a low variance in matching success rate during the later stages, indicating that the model attains comparable performance across different scenes and demonstrates strong generalization capability. The degradation in unseen scenes remains minor and within an acceptable range. A closer observation further reveals that, during the initial phase of matching, the variance across scenes is relatively high. This is due to differences in passenger flow patterns when entering the positioning zone—some scenes have constrained entrances or fixed movement paths, leading to highly similar trajectories and increased matching difficulty. However, as time accumulates, the model gradually mitigates such discrepancies and stabilizes at a high matching success rate, indicating strong reliability and robustness.

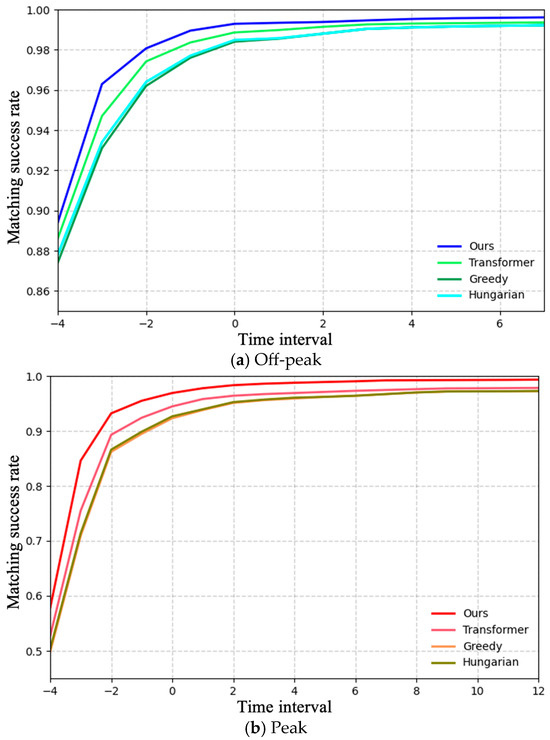

To benchmark performance, we compare the proposed model against both traditional and deep learning-based approaches. To ensure fairness in the comparison, these baseline methods adopt complete sequences, allowing them to access full historical information. The comparative methods selected in this paper include:

- Distance-based greedy matching: For each UWB trajectory, this method selects the vision trajectory with the smallest average trajectory error as its corresponding match.

- Hungarian Algorithm: This algorithm constructs an average trajectory error matrix using all UWB trajectories and candidate vision trajectories involved in the matching process at the time, then identifies the matching relationship with the minimum total average trajectory error to achieve globally optimal matching.

- Transformer-based method: Currently, there are no existing deep learning–based trajectory alignment methods directly applicable to the UWB–vision matching scenario. To provide a deep learning–based baseline, we implemented a simplified Transformer-based contrastive learning framework derived from our proposed architecture. Specifically, the prior alignment probability and the InfoNCE loss were removed, and a standard Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) loss was adopted instead.

Figure 9 reports the results under both peak and off-peak conditions. In general, the proposed method consistently achieves the highest accuracy across all steps and maintains strong performance even in peak periods, underscoring its robustness in metro stations. A detailed analysis shows that in off-peak scenarios, passengers are relatively sparse and UWB drift is minimal, making matching relatively straightforward—even a simple greedy strategy can yield satisfactory results. In contrast, during peak scenarios, where trajectory overlap and UWB drift are more severe, matching errors easily occur when relying solely on average trajectory errors. The Transformer-based method, which employs only basic contrastive learning without adaptation to metro-specific conditions such as the high similarity among passenger trajectories and modality imbalance between vision and UWB, shows only moderate performance—slightly outperforming distance-based methods in dense crowd scenarios. By comparison, our proposed method introduces a progressive alignment mechanism guided by temporal priors and contrastive learning with InfoNCE loss, effectively enhancing robustness under modality imbalance and complex crowd dynamics. Its matching error rate is 76% lower than that of distance-based methods and 68% lower than the Transformer-based baseline.

Figure 9.

Performance comparison between the proposed method and baseline methods in peak and off-peak scenarios.

Additionally, under modality imbalance (where UWB trajectories are sparse), unlike traditional one-to-one matching, it is rare for multiple UWB trajectories to match the same vision trajectory. This results in only a very limited improvement of the Hungarian algorithm over the simple greedy matching method.

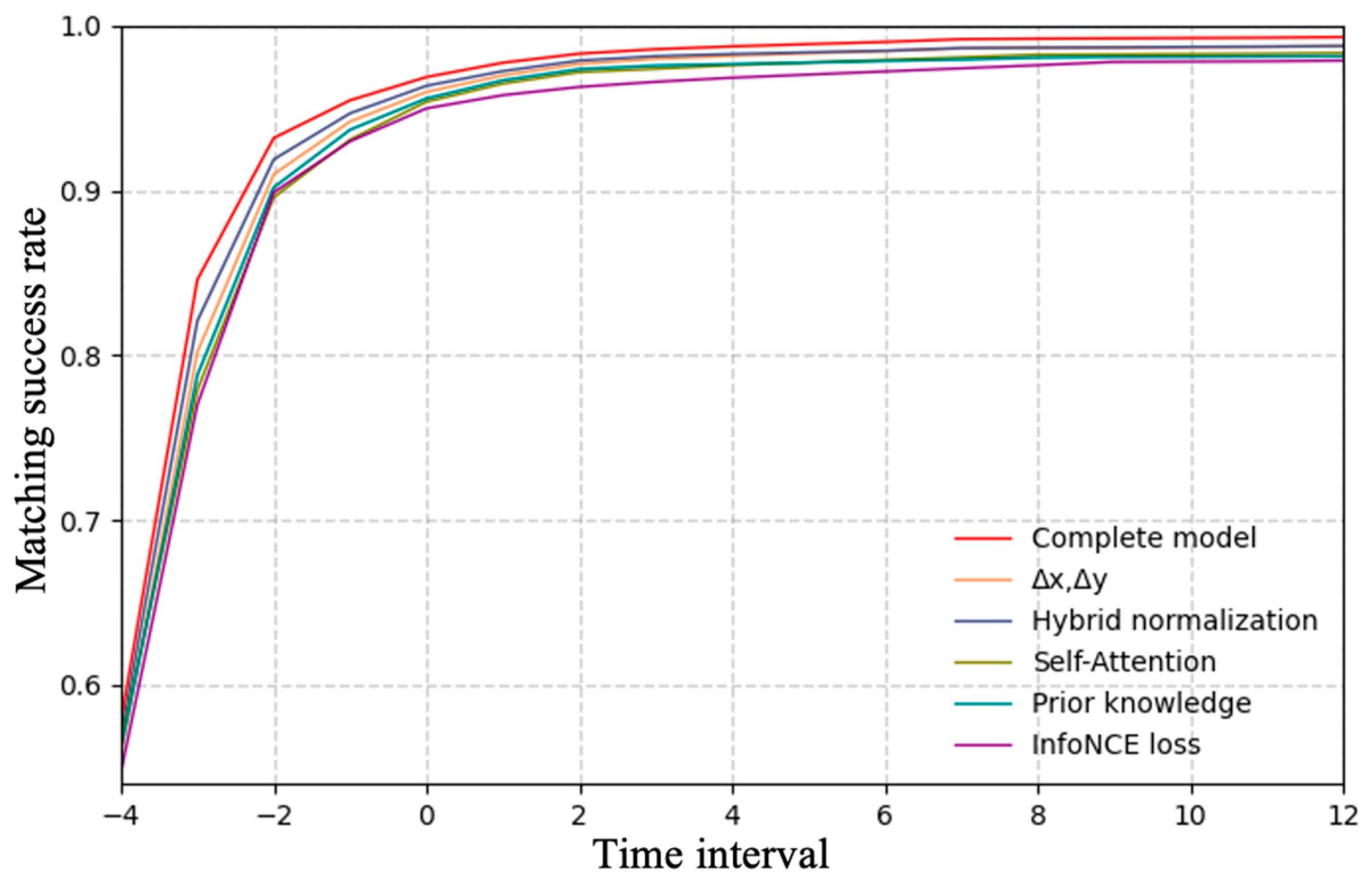

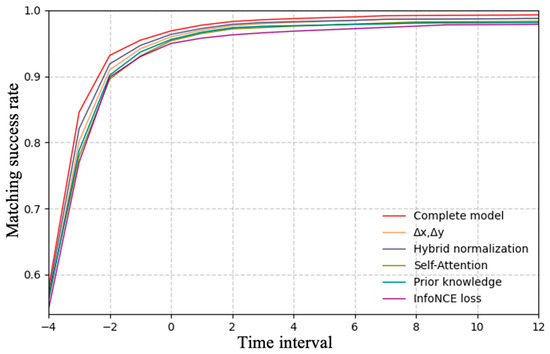

4.3. Ablation Study

To evaluate the contribution of individual components, we performed ablation experiments on the following elements, with detailed descriptions of each ablation setup provided below:

- : If this component is excluded, the network input will only utilize absolute position coordinates as trajectory features.

- Hybrid normalization strategy: When this strategy is removed, and are all normalized using the min–max normalization method.

- Self-Attention mechanism: If this mechanism is removed, the extraction of temporal features for each trajectory will rely solely on the Temporal Convolutional Network (TCN).

- Prior alignment probability: When this prior knowledge is excluded, the first cross-attention layer adopts the standard Transformer attention, identical to the subsequent layers, thus removing the prior constraint.

- InfoNCE loss: If this component is omitted, the model will adopt the standard Binary Cross-Entropy (BCE) Loss as its loss function.

Figure 10 summarizes the results in peak scenarios, with time steps on the horizontal axis and accuracy on the vertical axis. The complete model consistently outperforms all ablation variants.

Figure 10.

Results of ablation experiments in peak scenarios.

Specifically, removing reduces the model’s sensitivity to the short-term dynamics of passenger movement, making it harder to distinguish similar trajectories. When are processed using min–max normalization, a single large UWB error may dominate the scaling process, compressing valid motion information and leading to results similar to those of removing . Excluding the Self-Attention mechanism weakens the model’s ability to capture the long-range dependencies between different time steps in a trajectory, leading to a notable drop in accuracy. Removing the prior alignment probability prevents the model from leveraging prior alignment information, leading to more diffuse attention distributions and reduced matching accuracy and stability. Finally, replacing InfoNCE Loss with BCE Loss prevents the model from effectively distinguishing scarce but critical positive samples, causing the most severe performance degradation. These results confirm that each component plays a critical role, collectively contributing to the robustness and effectiveness of the proposed model.

4.4. Computational Efficiency and Deployment Feasibility

To evaluate whether the proposed trajectory alignment algorithm can be applied to real-world deployment, we conducted inference experiments on a PC equipped with an Intel i5-9300H CPU and an RTX 4060 GPU (16 GB VRAM). Using the trained model, the actual GPU memory allocated by PyTorch 2.7 during inference was approximately 33 MB, while the total memory usage observed via NVIDIA-smi reached 146 MB. This discrepancy may arise from CUDA context initialization and PyTorch’s internal memory caching mechanism.

Under the above configuration, the inference speed reached 207 Hz, demonstrating the model’s high computational efficiency. Furthermore, since the maximum input dimensions of the model are fixed, we can ensure that the worst-case inference time remains predictable and stable, which is critical for real-time deployment scenarios. Given a trajectory sampling frequency of 12.5 Hz, the model can process ten consecutive inputs, corresponding to approximately 200 UWB tags, even under conservative assumptions. Therefore, the proposed trajectory alignment algorithm fully satisfies the real-time performance and scalability requirements of large-scale multi-modal trajectory alignment in dense metro environments.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

To address the challenges of high similarity among passenger trajectories and modality imbalance in UWB–Vision trajectory matching for seamless payment in metro stations, this paper proposes a multi-modal trajectory progressive matching method under modality imbalance. The method incorporates a prior knowledge-guided progressive matching mechanism that effectively leverages the temporal continuity of trajectories, gradually strengthening cross-modal alignment confidence while reducing the uncertainty of individual matches. In addition, a contrastive learning strategy with the InfoNCE loss is introduced to enhance the model’s capability of distinguishing scarce but critical positive samples, thereby ensuring stable matching on the UWB modality. Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed method achieves notable improvements over baseline approaches in both off-peak and peak periods, and reduces the matching error rate by 68% compared to the baseline methods during peak periods. These results confirm that the proposed approach can maintain reliable performance under dense crowds and complex electromagnetic interference, providing strong support for the stable operation of seamless payment systems in metro stations.

Although the proposed method significantly reduces the trajectory match error rate, occasional mismatches remain unavoidable, largely because each UWB trajectory is forced to be paired with a visual trajectory. Nevertheless, as discussed earlier, such occasional mismatches can be mitigated by applying a similarity threshold that labels low-confidence associations as “unmatched”, thereby improving robustness under dense crowd conditions. In future work, we plan to design the overall seamless payment workflow by combining multiple matching strategies, applying threshold-based filtering of low-confidence associations, and incorporating additional post-processing to ensure the accuracy of billing information. Inevitably, these post-processing procedures will increase gate-crossing latency. However, since our method achieves a high matching success rate, it enables the use of stricter thresholds with fewer uncertain cases requiring post-processing, thereby providing a practical advantage in enhancing the overall efficiency of seamless payment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.P. and K.Z.; methodology, K.Z.; software, K.Z.; validation, M.A.G. and N.P.; formal analysis, K.Z., M.A.G. and N.P.; investigation, K.Z., M.A.G. and N.P.; resources, Y.Z.; data curation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, K.Z.; writing—review and editing, M.A.G. and N.P.; visualization, K.Z.; supervision, L.P.; project administration, L.P.; funding acquisition, L.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the Guangdong S&T Programme (Grant No. 2024B0101020004) and the Major Program of Science and Technology of Shenzhen (Grant Nos. KJZD20231023100304010 and KJZD20231023100509018).

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author due to privacy and legal reasons.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yongfeng Zhen was employed by the company Shenzhen Shenzhen Tong Co., Ltd., Shenzhen 518131, China. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Di Pietra, V.; Dabove, P. Recent Advances for UWB Ranging from Android Smartphone. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/ION Position, Location and Navigation Symposium (PLANS), Monterey, CA, USA, 24–27 April 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 1226–1233. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, A.; Krollmann, S.; Putz, F.; Hollick, M. Smartphones with UWB: Evaluating the Accuracy and Reliability of UWB Ranging. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.11220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Win, M.Z.; Dardari, D.; Molisch, A.F.; Wiesbeck, W.; Jinyun Zhang, W. History and Applications of UWB; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Coppens, D.; Shahid, A.; Lemey, S.; Van Herbruggen, B.; Marshall, C.; De Poorter, E. An Overview of UWB Standards and Organizations (IEEE 802.15. 4, FiRa, Apple): Interoperability Aspects and Future Research Directions. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 70219–70241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirch, H.-J.; Leong, F. Introduction to Impulse Radio Uwb Seamless Access Systems. In Proceedings of the Fraunhofer SIT ID: SMART Workshop, Darmstadt, Germany, 28 January 2020; pp. 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, T.B.; Musselman, R.L.; Emessiene, B.A.; Gift, P.D.; Choudhury, D.K.; Cassadine, D.N.; Yano, S.M. The Effects of the Human Body on UWB Signal Propagation in an Indoor Environment. IEEE J. Sel. Areas Commun. 2002, 20, 1778–1782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez-Mireles, F. On the Performance of Ultra-Wide-Band Signals in Gaussian Noise and Dense Multipath. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2002, 50, 244–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stephan, P.; Heck, I.; Krau, P.; Frey, G. Evaluation of Indoor Positioning Technologies under Industrial Application Conditions in the SmartFactoryKL Based on EN ISO 9283. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2009, 42, 870–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morar, A.; Moldoveanu, A.; Mocanu, I.; Moldoveanu, F.; Radoi, I.E.; Asavei, V.; Gradinaru, A.; Butean, A. A Comprehensive Survey of Indoor Localization Methods Based on Computer Vision. Sensors 2020, 20, 2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhall, A.; Chelani, K.; Radhakrishnan, V.; Krishna, K.M. LiDAR-Camera Calibration Using 3D-3D Point Correspondences. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1705.09785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, M.; Nuchter, A.; Lorken, C.; Lilienthal, A.J.; Hertzberg, J. Evaluation of 3D Registration Reliability and Speed-A Comparison of ICP and NDT. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2009; pp. 3907–3912. [Google Scholar]

- Levinson, J.; Thrun, S. Automatic Online Calibration of Cameras and Lasers. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems, Berlin, Germany, 24–28 June 2013; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Nagy, B.; Benedek, C. On-the-Fly Camera and Lidar Calibration. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, P.; Yu, C.; Xia, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Zhao, K.; Chen, W. An Indoor Positioning Method Based on UWB and Visual Fusion. Sensors 2022, 22, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, S.; Islam, T.; Munir, S.; Nirjon, S. Eyefi: Fast Human Identification through Vision and Wifi-Based Trajectory Matching. In Proceedings of the 2020 16th International Conference on Distributed Computing in Sensor Systems (DCOSS), Marina Del Rey, CA, USA, 15–17 June 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, C.; Yang, X.; Zhen, Y.; Bai, Y.; Peng, L. Research on Multimodal Fusion Indoor Positioning Under High-Throughput Passenger Flow: A Case Study of Metro Station. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 27th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Edmonton, AB, Canada, 24–27 September 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 2214–2220. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, D.; Liu, R.; Li, H.; Wang, S.; Jiang, W.; Lu, C.X. Cross Vision-Rf Gait Re-Identification with Low-Cost Rgb-d Cameras and Mmwave Radars. Proc. ACM Interact. Mob. Wearable Ubiquitous Technol. 2022, 6, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, K.; Xia, Q.; Li, P.; Stankovic, J.; Lu, C.X. Robust Human Detection under Visual Degradation via Thermal and Mmwave Radar Fusion. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2307.03623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Yao, T.; Shi, R.; Mei, L.; Wang, S.; Yin, Z.; Jiang, W.; Wang, S. Mission: Mmwave Radar Person Identification with Rgb Cameras. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM Conference on Embedded Networked Sensor Systems, Hangzhou, China, 4–7 November 2024; pp. 309–321. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, Y.; Shuai, X.; Tan, R.; Xing, G. Interpersonal Distance Tracking with mmWave Radar and IMUs. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Information Processing in Sensor Networks, San Antonio, TX, USA, 9–12 May 2023; pp. 123–135. [Google Scholar]

- Meinhardt, T.; Kirillov, A.; Leal-Taixe, L.; Feichtenhofer, C. Trackformer: Multi-Object Tracking with Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 8844–8854. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, P.; Cao, J.; Jiang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xie, E.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, C.; Luo, P. Transtrack: Multiple Object Tracking with Transformer. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2012.15460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M.; Bilodeau, G.-A.; Saunier, N. Learning Data Association for Multi-Object Tracking Using Only Coordinates. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 160, 111169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuzcuoğlu, Ö.; Köksal, A.; Sofu, B.; Kalkan, S.; Alatan, A.A. Xoftr: Cross-Modal Feature Matching Transformer. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 4275–4286. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, X.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, X.; Huang, Q.; Chen, Y.; Fu, H.; Tai, C.-L. Transfusion: Robust Lidar-Camera Fusion for 3D Object Detection with Transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–24 June 2022; pp. 1090–1099. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, S.; Morris, D.; Radha, H. TransCAR: Transformer-Based Camera-and-Radar Fusion for 3D Object Detection. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Detroit, MI, USA, 1–5 October 2023; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2023; pp. 10902–10909. [Google Scholar]

- Qingyun, F.; Dapeng, H.; Zhaokui, W. Cross-Modality Fusion Transformer for Multispectral Object Detection. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2111.00273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Tian, Z.; Huang, H.; Li, X.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, N.; Zhai, W. Heterogeneous Secure Transmissions in IRS-Assisted NOMA Communications: CO-GNN Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 34113–34125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Jiang, D.; Liang, L.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, N. Performance Evaluations for RIS-Assisted GF-NOMA in Satellite Aerial Terrestrial Integrated Networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Pang, M.; Wang, Z.; Hou, S.; Zhang, D. Observer Based Fault Tolerant Control Design for Saturated Nonlinear Systems with Full State Constraints via a Novel Event-Triggered Mechanism. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 161, 112221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Hou, S.; Pang, M.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, D. Reinforcement Learning-Based Secure Tracking Control for Nonlinear Interconnected Systems: An Event-Triggered Solution Approach. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 161, 112243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Wang, Y.; Meng, L.; Yan, J.; Qin, C. Adaptive Critic Design for Safety-Optimal FTC of Unknown Nonlinear Systems with Asymmetric Constrained-Input. ISA Trans. 2024, 155, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güvenç, İ.; Chong, C.-C.; Watanabe, F.; Inamura, H. NLOS Identification and Weighted Least-Squares Localization for UWB Systems Using Multipath Channel Statistics. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2007, 2008, 271984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Zeng, W.; Liu, W. Fairmot: On the Fairness of Detection and Re-Identification in Multiple Object Tracking. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2021, 129, 3069–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PaddlePaddle. PaddleDetection, Object Detection and Instance Segmentation Toolkit Based on PaddlePaddle. Github 2019. Available online: https://github.com/PaddlePaddle/PaddleDetection (accessed on 1 September 2025).

- van den Oord, A.; Li, Y.; Vinyals, O. Representation Learning with Contrastive Predictive Coding 2018. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1807.03748. [Google Scholar]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need 2017. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 30 (NIPS 2017), Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, A.; Kovaleva, O.; Rumshisky, A. A Primer in BERTology: What We Know About How BERT Works. Trans. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2020, 8, 842–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszek, K.; Grzechca, D.; Becker, A. Design of the UWB Positioning System Simulator for LOS/NLOS Environments. Sensors 2021, 21, 4757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).