Abstract

Aiming at the problems of fixed trigger patterns that are prone to detection in existing invisible backdoor attacks, this paper proposes a backdoor attack method that integrates local binary pattern (LBP) with dynamic randomized least significant bit (LSB) steganography. The multi-bit coding characteristic of LBP is leveraged to enrich the representational expressiveness of trigger information within the embedding budget, combined with LSB steganography to maintain visual imperceptibility, and a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) is introduced to randomize embedding locations to mitigate detectors that rely on fixed-position patterns. Experiments show that the proposed method demonstrates potential advantages in terms of steganography, attack success rate, and anti-detection capability on both CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet datasets. Among them, the structural similarity index (SSIM) and peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) reach up to 0.98 and above 36 dB in terms of covertness, respectively. In anti-detection experiments, the attack method maintains high attack success rates under D-BR defense (CIFAR-10: Test_ASR > 85%; Tiny-ImageNet: Test_ASR > 95%), while under SPECTRE defense—a spectral-based statistical method—the defender’s leakage detection rate of poisoned samples remains low (CIFAR-10: 5.96%; Tiny-ImageNet: 10.56%). This clearly validates the proposed attack’s robustness against mainstream defense mechanisms.

1. Introduction

In recent years, research into deep neural networks (DNNs) has achieved significant progress, demonstrating outstanding performance in fields such as facial recognition [1], autonomous driving [2], natural language processing [3], and object detection [4], thereby driving the widespread application of artificial intelligence technologies. However, as model complexity increases and reliance on third-party data and training resources grows, security concerns have gradually become a focal point of research. Backdoor attacks, which implant hidden triggers to ensure models perform well under normal inputs while outputting predetermined misclassifications when triggered, represent one of the most threatening attack vectors today. Gu et al.’s BadNets [5] first exposed this risk by adding visible grid patches or stickers to the corners of clean samples as triggers. However, traditional LSB-based methods suffer from two fundamental limitations. First, they typically modify only the lowest 1–2 bits per pixel, which constrains embedding capacity and makes it difficult for pure LSB schemes to encode more complex information or directly improve trigger robustness [6]. Second, most approaches rely on fixed embedding regions (e.g., image centers or predetermined blocks), causing embedded positions to exhibit predictable distributions in the pixel or frequency domains, which makes such triggers vulnerable to detectors that exploit fixed-position or fixed-pattern priors [7]. Consequently, achieving dynamic trigger embedding while enhancing robustness under perturbations has become a central challenge in the design of invisible backdoor attacks.

To address this bottleneck, this paper proposes an invisible-trigger design that combines Local Binary Patterns (LBP) [8] with Least Significant Bit (LSB) steganography [6] and employs a Pseudo-Random Number Generator (PRNG) [9] to enable dynamic randomized embedding. The method uses LBP to compute local contrast relationships among neighboring pixels, generating structured representations of local textures. By mapping these LBP-derived descriptors into LSB-based embeddings, the approach enhances trigger robustness against perturbations while maintaining visual imperceptibility. The PRNG-driven random position selection mechanism further disperses the trigger information across different image regions, improving concealment and reducing detectability by defenses that rely on fixed embedding locations [10].

The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We propose a complementary LBP–LSB invisible-trigger generation method, where LBP encodes local texture structure and LSB maintains visual imperceptibility, and their synergy enhances trigger robustness.

- We design a PRNG-based dynamic randomized embedding mechanism, in which pseudo-random coordinate selection breaks fixed-position patterns, reducing detectability by defenses that assume fixed embedding locations.

- We conduct systematic experiments and comparative analyses on CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet. The results demonstrate that the proposed method performs well in terms of concealment and attack success rate.

2. Relevant Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Local Binary Pattern

Local Binary Pattern (LBP) serves as a classical texture description algorithm, whose core principle lies in capturing the statistical characteristics of microscopic textures through relative intensity variations within pixel neighbourhood systems. This algorithm systematically quantifies the grey-level intensity differences between the central pixel and its neighbouring pixels: first generating a binary bit sequence in spatial order, then directly converting it into a decimal feature descriptor via a polynomial-weighted mapping. This achieves a mathematical representation of the image’s local texture structure.

Its formula is defined as:

Local Binary Pattern (LBP) is a classical texture descriptor that encodes local texture by comparing the intensity of a center pixel with its neighbors. For a given center pixel with intensity and neighboring intensities ), LBP is defined as:

where denotes the centre pixel within the neighbourhood, its pixel value is , and represents the pixel values of other pixels within the neighbourhood.

Where is a threshold function defined as:

2.2. Least Significant Bit

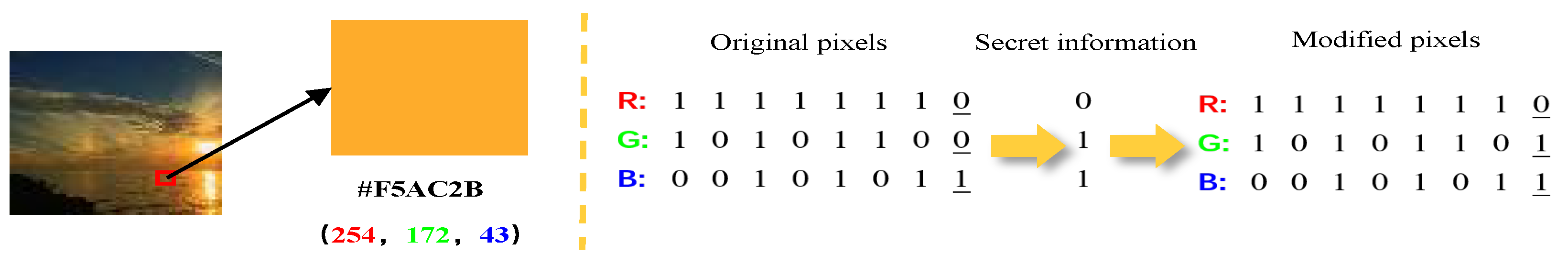

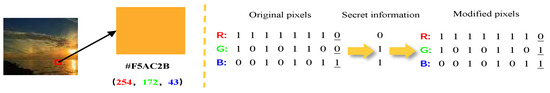

LSB steganography embeds information directly in the image’s spatial domain by modifying the least significant bit (s) of pixel values. In typical 24-bit RGB images each color channel is represented by 8 bits (256 levels), yielding possible colors. Small changes to the least significant bits produce color differences that are generally imperceptible to the human visual system, allowing secret data to be hidden without noticeable visual distortion. Figure 1 illustrates the basic LSB embedding process.

Figure 1.

Basic process of LSB steganography.

2.3. Pseudorandom Number Generator (PRNG)

A Pseudo-Random Number Generator (PRNG) deterministically produces sequences that approximate randomness. In our implementation, we derive seeds via the SHA-256 hash of input data (for example, image content). We extract a fixed portion (e.g., the first 8 bits) of the hash as the seed; this approach balances uniqueness and computational efficiency. Using a master seed combined with per-image hash seeds enables reproducible experiments while supporting dynamic, randomized embedding of triggers at runtime.

2.4. Backdoor Attack

With the widespread adoption of deep learning models, the stealth and robustness of backdoor attacks have become key research focuses. Early backdoor attack methods such as BadNets and Blended [11] both achieve model contamination by introducing fixed, visible triggers. The former relies on a white square placed at a specific location (the bottom-right corner of the target image), while the latter employs a globally embedded pattern with mixed transparency. Although these approaches are straightforward to implement, the visual saliency of their triggers makes them susceptible to human observation or detection by defence mechanisms based on activation analysis. To enhance concealment, researchers progressively shifted towards invisible trigger designs. WaNet [12] generates dynamic triggers through image distortion, ReFool [13] conceals trigger features using reflection patterns in natural scenes, while Low Frequency [14] embeds global perturbations within low-frequency components in the frequency domain. Nevertheless, these approaches still exhibit room for improvement in both concealment and anti-detection capabilities. Whilst WaNet’s dynamic distortion enhances concealment, it risks semantic corruption and residual feature exposure. ReFool’s light sensitivity and fixed-region embedding render it susceptible to spatial detection tools, while Low Frequency suffers from efficient identification due to anomalous spectral distributions.

Addressing these challenges, this paper proposes a backdoor attack method based on local texture feature fusion and dynamic steganographic embedding. Experiments demonstrate that our approach maintains attack effectiveness whilst achieving superior concealment.

2.5. Backdoor Defence

With the rapid advancement of deep neural network (DNN) backdoor attack techniques, corresponding defence methods tailored to different attack scenarios have emerged. The categories of backdoor defence methods are outlined in Table 1. Existing defences can be classified into four types based on their implementation mechanisms and defence stages.

Table 1.

Taxonomy of backdoor defense methods.

Among the aforementioned defence methods, D-BR and SPECTRE respectively represent two typical defence strategies: model optimisation and data cleansing. D-BR achieves end-to-end defence without requiring prior knowledge by decoupling the sensitivity of backdoor features during training and dynamically adjusting model parameters to suppress backdoor activation. SPECTRE, grounded in statistical robustness theory, detects poisoned samples by analysing distribution shifts in model outputs, demonstrating universality against complex trigger patterns. Both exhibit state-of-the-art defence performance on public benchmarks; hence, this paper selects D-BR and SPECTRE for defence experiments.

3. Dynamic Invisible Backdoor Attack Method with LBP-LSB

3.1. Threat Model

3.1.1. Problem Definition

In this threat model, backdoor attacks implant specific malicious behaviour into deep neural networks (DNNs) by contaminating their training data. Attackers inject trigger-poisoned samples into the training set, whose visual features remain highly consistent with original data while their class labels are tampered to predetermined target categories. Attackers require partial control over training data, mastery of trigger generation and dynamic embedding techniques, and need not rely on specific knowledge of the target model’s architecture.

Our threat model differs from prior steganographic backdoors by explicitly combining local texture encoding with randomized, per-image embedding, which reduces both spectral and spatial detection signatures. Comparative experiments (LSB-only, fixed-position, and full methods) in Section 4.5.3 demonstrate that only the combined design achieves the desired trade-off between stealth (high SSIM) and robustness (high ASR).

3.1.2. Attack Targets

The attack target achieves the following dual characteristics through backdoor implantation: Stealth requires the model to maintain normal classification performance when not triggered (with negligible accuracy deviation from the clean model) and for the trigger to be imperceptible to the visual system. Attack effectiveness necessitates that, upon triggering, the model outputs the predefined target category with high probability, thereby enabling precise initiation of malicious actions under specific conditions while maintaining functional compliance.

3.2. Attack Design

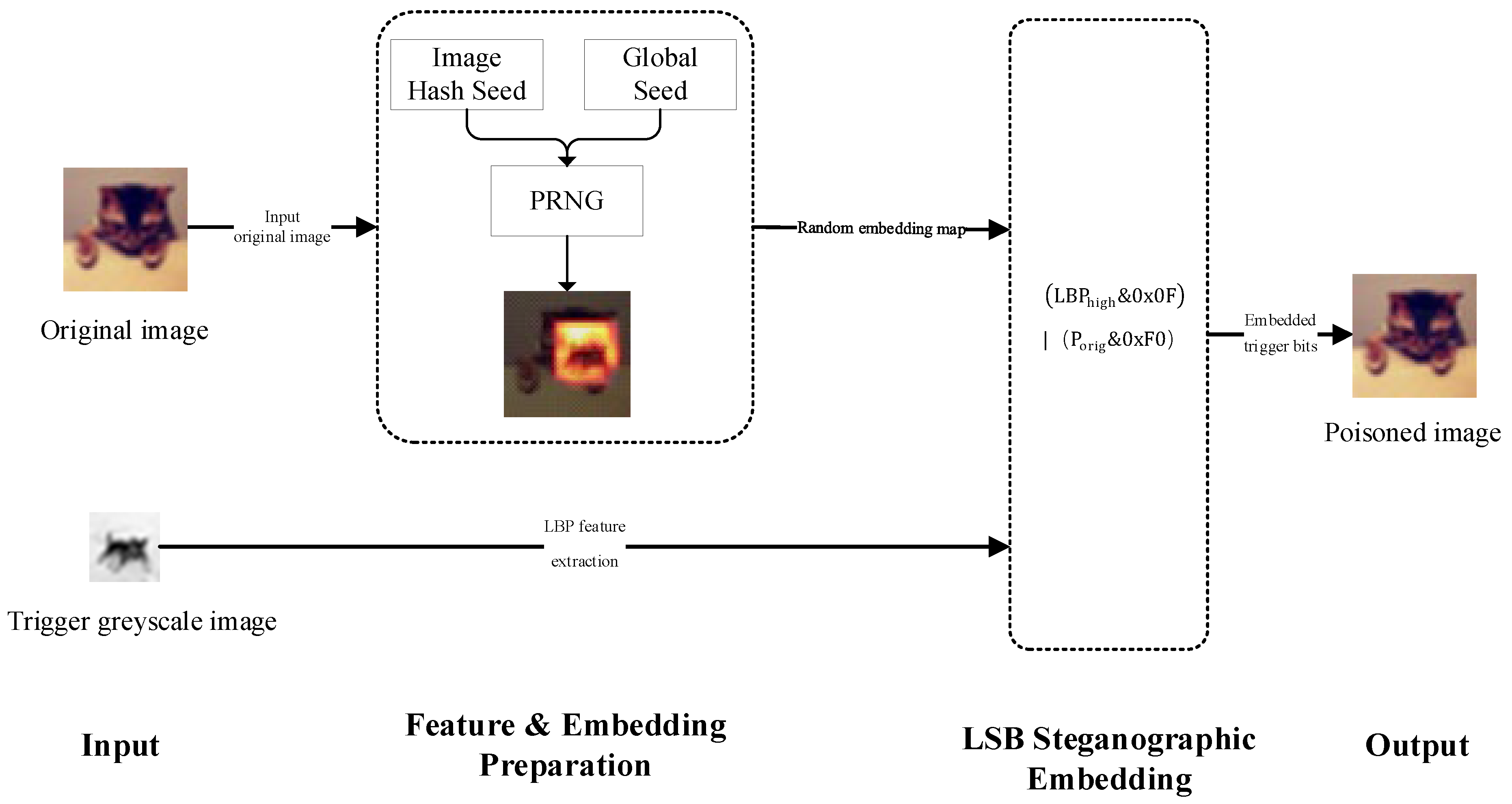

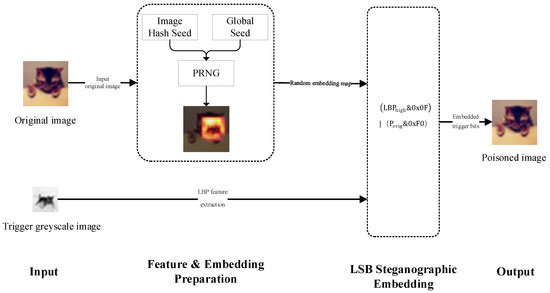

The implementation steps for the LBP-LSB collaborative optimisation dynamic invisible backdoor attack method are as follows, with the technical approach illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Technical roadmap of attack method framework.

- (1)

- Step One: Trigger Feature Extraction

Based on predefined trigger images, the LBP algorithm calculates the relative relationships between pixel grey values within local image neighbourhoods to generate a binary encoding pattern. This pattern effectively characterises the image’s local texture structure and serves as the core feature information for backdoor triggering.

- (2)

- Step Two: Dynamic Embedding Position Selection

To enhance concealment and anti-detection capabilities, a pseudo-random number generator (PRNG) dynamically determines the embedding location.

- (3)

- Step Three: LSB Steganography Embedding

The LBP feature data from the trigger image is embedded into the target image using LSB steganography techniques.

To complement the technical roadmap in Figure 2, we provide a pseudocode of the LBP–LSB co-optimization embedding procedure (Algorithm 1). The pseudocode covers three stages: trigger preprocessing and LBP feature extraction; image-specific seed generation and deterministic PRNG-based selection of an embedding start; and extraction of the top LBP bits which are embedded into the target image LSBs (per channel for RGB).

| Algorithm 1: LBP-LSB Co-optimization for dynamic unseen backdoor attack | |

| Step | Operation |

| 1 | Require: Target image ; optional trigger image ; LBP radius (default 1); number of neighbors (default 8); LSB bits (default 4); master seed (default 1234) |

| 2 | Ensure: Poisoned image |

| 3 | Initialize PRNG with seed . |

| 4 | If trigger image is provided then Convert Trigger to grayscale using BT.601 formula: Resize Trigger to dataset-specific dimensions. (Use 16 × 16 for CIFAR-10 triggers; 28 × 28 for Tiny-ImageNet triggers.) Compute LBP pattern . End If |

| 5 | Compute image-specific seed: |

| 6 | Initialize PRNG with combined seed |

| 7 | Randomly select embedding start position such that the trigger fits inside the image |

| 8 | Extract the high b bits of the LBP pattern: |

| 9 | For each pixel in do If Image is grayscale then Else For each channel do End For End If End For |

| 10 | Return Image’ |

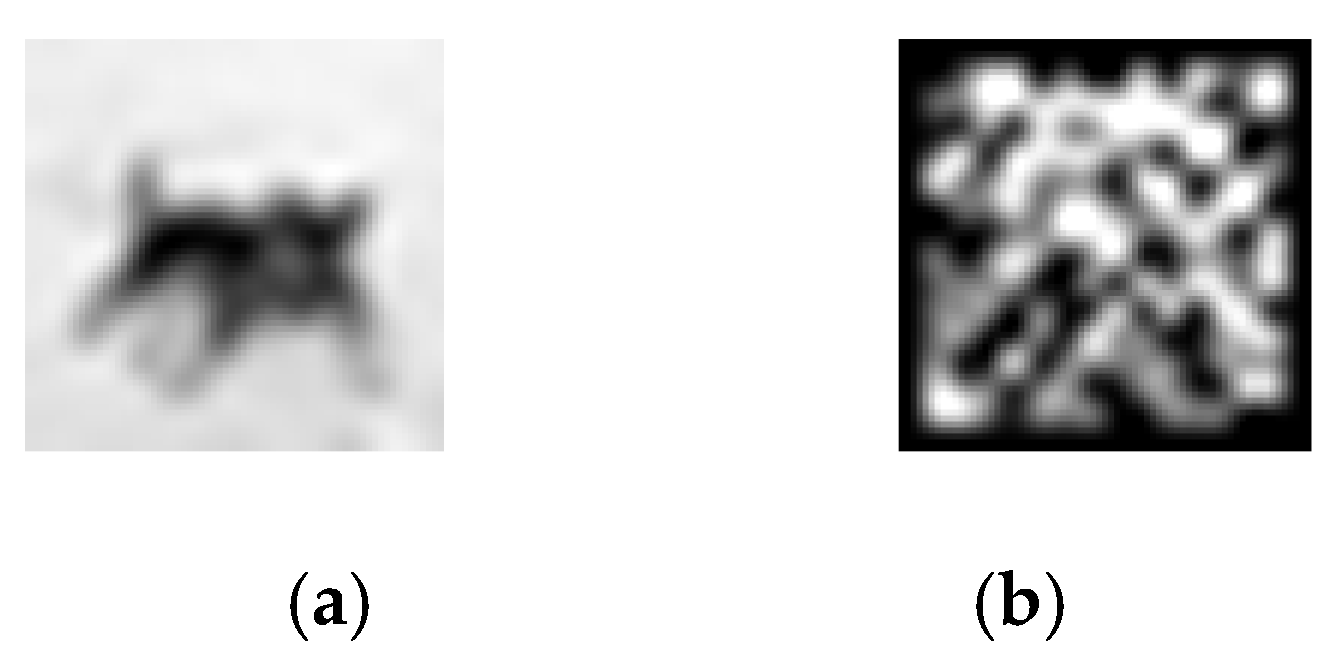

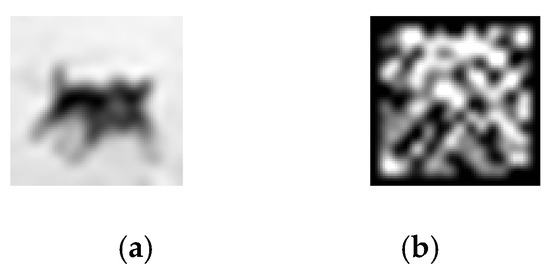

3.3. Trigger LBP Value Extraction

The LBP feature extraction for triggers undergoes a standardised preprocessing workflow: resizing images to a preset resolution through dimension adjustment balances attack effectiveness with concealment; greyscale conversion maps RGB images to a single-channel greyscale space, simplifying information while enhancing texture features; normalisation linearly maps pixel values to the [0, 255] range, ensuring consistent data distribution and mitigating feature bias caused by brightness variations. Building upon this foundation, LBP feature generation comprises the following core operations: threshold determination based on the grey-scale value of the centre pixel within a sliding window, where the grey-scale values of the surrounding 8-neighbourhood pixels are compared against this threshold to generate a binary encoding sequence (≥threshold = 1, otherwise = 0); Applying a weighted sum by assigning weights from to to the binary bits in a clockwise direction and accumulating them to generate a local texture encoding value; Finally, using the weighted sum result as the LBP encoding value for that window to represent local texture features. Figure 3 shows the trigger grey-scale image and the trigger LBP feature map.

Figure 3.

Grayscale image and LBP feature map of trigger. (a) Grayscale image of trigger, (b) LBP feature map of trigger.

3.4. Trigger Embedding Position

To achieve dynamic random embedding of trigger information, this paper designs a hierarchical control mechanism based on a pseudorandom number generator (PRNG). This ensures that trigger information can be embedded randomly and unpredictably into different regions of the attacked image while maintaining experimental reproducibility.

Seed Generation:

- (1)

- Master Seed: Injected via the seed parameter to guarantee experimental reproducibility. If unspecified, dynamically generated using a system entropy source (timestamp ⊕ process ID) to ensure controllable global randomness.

- (2)

- Image Seed: Derived from the first 8 bits of the SHA-256 hash of the target image’s content, guaranteeing identical embedding locations for the same image across different runs. Altering the master seed will change the image seed.

Finally, trigger information is randomly embedded into distinct regions of the target image to generate backdoor samples. These backdoor samples are then used to train deep neural networks, yielding DNN models incorporating the backdoor.

3.5. LSB Steganography

During the trigger feature embedding stage, this method extracts the upper four significant bits of LBP texture features as trigger features. This design leverages the bit-weighting characteristics of LBP values: the upper four bits carry the primary structural information of the image, enabling efficient data compression while preserving core texture representation. Subsequently, mask techniques precisely embed the high-order 4 bits of the trigger feature into the low-order 4 bits of target image pixels. This design ensures the embedded features significantly contribute to the model’s texture recognition while maintaining visual quality through LSB modification strategies. Visual alterations remain imperceptible to the human eye, thereby guaranteeing attack effectiveness alongside excellent concealment. Based on LSB steganography principles, the pixel value modification process can be precisely defined through bitwise operations: Let the original pixel value be and the trigger’s high-order 4-bit texture feature be . The generation of the new pixel value can be formally expressed as:

Moreover, addressing the multi-channel nature of RGB images, this method independently performs the aforementioned embedding operations on each colour channel. This effectively prevents colour distortion arising from differing modifications across channels, thereby ensuring overall tonal consistency within the image. This LSB steganography strategy maintains the visual quality of the image while guaranteeing the effectiveness of the backdoor attack, thus achieving covertness in the attack.

4. Experimental Evaluation

4.1. Datasets and Models

This study employs two benchmark datasets: CIFAR-10 (comprising 10 classes of 3-channel, 32 × 32-pixel low-resolution images for small-scale image classification tasks) and Tiny-ImageNet (encompassing 200 classes of 3-channel, 64 × 64-pixel medium-resolution natural images). to construct a multi-dimensional gradient evaluation scenario spanning resolution, category complexity, and data scale.

The ResNet-18 model was employed to evaluate the effectiveness of backdoor attacks under varying image semantic densities and task scales. The training configuration was set as follows: batch size = 128, epochs = 100, optimizer = SGD (lr = 0.01), learning rate scheduler = CosineAnnealingLR, momentum = 0.9, and weight decay = 0.0005.

4.2. Attack Success Rate and Clean Data Accuracy

Experiments utilised single-target attacks with the target label set to 0 and a poisoning rate of 0.1. To validate the effectiveness of the proposed attack method, two primary metrics—attack success rate (ASR) and clean sample accuracy (ACC)—were employed for evaluation. Experimental results are summarised in Table 2.

Table 2.

Comparison of ASR and ACC performance across attack methods.

To ensure fair comparisons, all attack methods were trained and evaluated under the following unified settings: consistent preprocessing and training/validation split, and the same evaluation metrics (ASR, ACC). Details specific to each attack method are as follows:

WaNet 12: The warp-based method employed cross_ratio = 2, random_rotation = 10, random_crop = 5, s = 0.5, k = 4, and grid_rescale = 1 for trigger generation. Learning rate scheduler: MultiStepLR with milestones [100, 200, 300, 400] and gamma = 0.1.

BadNets 5: Training hyperparameters follow a unified configuration.

ReFool 13: Used pratio = 0.1, with parameters ghost_rate = 0.49, alpha_t = 0.4, offset = [0, 25], sigma = −1, ghost_alpha = −1, and clean_label = False. All training and evaluation followed the unified settings.

Low Frequency 14: The low-frequency injection method used pratio = 0.1. Other parameters followed the original implementation.

Our Method: Employed lbp_radius = 1, lbp_neighbors = 8, lbp_seed = 1234 (fixed for reproducibility), and lsb_bits = 4.

Experimental Results

On the CIFAR-10 dataset, the proposed method achieved an ASR of 99.43% alongside an ACC of 93.12%, significantly outperforming other comparative approaches. This demonstrates that our attack method achieves high attack success rates in small-scale image classification tasks while preserving the model’s normal classification performance.

On the Tiny-ImageNet dataset, our method achieved an ASR of 98.51%, lower than the BadNets method (99.06%), while maintaining an ACC of 55.17%, still higher than other invisible attack methods. As shown in Table 2, all methods exhibit lower ACC on Tiny-ImageNet than on CIFAR-10, indicating that increased dataset complexity universally impacts overall model classification performance.

In summary, the proposed attack method demonstrates excellent performance on small-scale datasets with simple feature distributions. It maintains high attack effectiveness and superior model usability on complex datasets, exhibiting robust stability and applicability.

4.3. Sensitivity Analysis

4.3.1. Model Sensitivity Analysis

To investigate the impact of backbone choice, we run the same attack pipeline on two datasets with the following model configurations: (1) baseline ResNet-18 on both CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet; (2) MobileNetV3-Large on CIFAR-10 (additional lightweight backbone); and (3) ConvNeXt-Tiny on Tiny-ImageNet (additional deeper backbone). All other settings (poisoning rate, optimizer, augmentation, training schedule) are kept identical to the main experiments. Table 3 summarizes the results. The proposed attack maintains high ASR across lightweight and deeper backbones, demonstrating robustness to backbone selection.

Table 3.

Attack performance across backbones.

4.3.2. Target Label Sensitivity Analysis

Target Label Sensitivity Analysis (all-to-one). To evaluate sensitivity to target choice, we perform single-target (all2one) attacks on ResNet-18 for CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet. For CIFAR-10 we test targets {0: airplane (original), 1: automobile (semantically close), 6: frog (semantically distant)}. For Tiny-ImageNet we test targets {0: Egyptian cat (original), 66: tabby (close), 71: teapot (distant)}. All other settings (poisoning rate, trigger, optimizer, augmentation, training schedule) remain identical to the main experiments. Results are shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Attack performance across targets.

4.3.3. Poisoning Rate Sensitivity

To evaluate the robustness of the proposed method under different poisoning intensities, we test poisoning rates pratio ∈ {0.01, 0.02, 0.05, 0.10} on ResNet-18 for CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet. For CIFAR-10, results are reported for target label 0 (airplane); for Tiny-ImageNet, results are reported for target label 0 (Egyptian cat). All other experimental settings (trigger design, optimizer, data augmentation, training schedule, and random seeds for model initialization) are kept identical to the main experiments. Attack success rate (ASR) and clean accuracy (ACC) are reported. Table 5 provides the complete numerical results.

Table 5.

Attack success rate (ASR) and clean accuracy (ACC) under different poisoning rates (pratio) for CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet.

The results show that ASR is low at small poisoning rates but increases sharply at moderate rates. These results indicate that our method maintains high attack success rates at moderate poisoning rates (0.05–0.10), demonstrating strong robustness against varying poisoning intensities.

4.4. Analysis of Concealment and Dynamism

4.4.1. Concealment Analysis

In this section, we perform covert-quality analysis of poisoned samples using PSNR [23] (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio), SSIM [24] (Structural Similarity Index Measure), FID [25] (Fréchet Inception Distance), and LPIPS [26] (Learned Perceptual Image Patch Similarity).

PSNR (Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio) values are typically expressed in decibels (dB) and serve to quantify the degree of image distortion. A PSNR value exceeding 40 dB indicates excellent image quality with virtually imperceptible distortion; values between 30–40 dB denote good quality with minor distortion; 20–30 dB signifies average quality with noticeable distortion; while values below 20 dB indicate poor quality with severe distortion. Higher PSNR values correspond to superior image quality.

The PSNR formula is:

where: and denote the original image and the distorted image respectively. and represent the dimensions of the images.

The SSIM value ranges from −1 to 1, measuring the similarity between two images in terms of brightness, contrast, and structure. When SSIM falls between 0.95 and 1, the images are highly similar with distortion being virtually imperceptible; a value between 0.8 and 0.95 indicates good image quality with minor distortion; a value between 0.5 and 0.8 indicates average image quality with noticeable distortion; while a value below 0.5 indicates poor image quality with severe distortion. The closer the SSIM value is to 1, the higher the image quality.

The SSIM formula is:

where: and denote the mean values (luminance) of images and respectively. and denote the standard deviations (contrast) of images and respectively. denotes the covariance (structural similarity) between images and . and are constants employed to prevent the denominator from becoming zero.

FID is adopted to evaluate the distributional similarity between poisoned and clean images rather than between generated and real images as in its original use for generative models. Specifically, we extract deep feature representations from a pretrained Inception network for both clean and poisoned image sets, and compute the distance between their feature distributions. A lower FID indicates that poisoned images are perceptually closer to clean ones, implying higher stealthiness of the poisoning process.

The FID formula is:

Here, and denote the mean feature vectors of the poisoned and clean image sets, respectively, and and are their corresponding covariance matrices. denotes the trace of a matrix.

In this context, smaller FID values indicate that the poisoned samples have feature distributions that are more consistent with clean data, suggesting higher imperceptibility. Conversely, larger FID values reveal stronger deviations, indicating that the poisoning process introduces visually detectable artifacts.

LPIPS measures perceptual similarity using learned deep features and is complementary to the above metrics: while FID measures distributional similarity at the set level and PSNR/SSIM measure pixel- or patch-level fidelity, LPIPS evaluates pairwise perceptual differences between individual poisoned-clean image pairs. LPIPS values are lower for more perceptually similar images (0 indicates near-identical perceptual appearance); in practice, small LPIPS (e.g., ≈0.01–0.1) suggests that human observers would find the poisoned image hardly distinguishable from its clean counterpart, whereas larger LPIPS indicates perceptible visual differences. In our experiments LPIPS is computed per poisoned-clean pair and averaged across all poisoned samples to report an overall perceptual-distance score.

Table 6 presents comparative results for SSIM, PSNR, FID and LPIPS across different backdoor attack methods on CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet. The SSIM and PSNR indices for the CIFAR-10 dataset were calculated by averaging pairwise comparisons between all poisoned samples in the CIFAR-10 validation set (totalling 4995 poisoned samples) and their corresponding clean samples. The SSIM and PSNR metrics for the Tiny-ImageNet dataset represent the average of pairwise comparisons between all poisoned samples in the Tiny-ImageNet validation set (450 poisoned samples in total) and their corresponding clean samples.

Table 6.

Comparison results of PSNR, SSIM, FID and LPIPS across attack methods.

According to the reported results, the proposed method attains the highest PSNR (36.23) and SSIM (0.9804) on CIFAR-10, and similarly achieves high PSNR (37.89) and SSIM (0.9871) on Tiny-ImageNet, indicating minimal pixel-wise and structural distortions compared with other methods. In terms of distribution-level consistency, the smaller FID values (0.0135 for CIFAR-10 and 0.0615 for Tiny-ImageNet) suggest that the overall feature distributions of the poisoned samples remain highly consistent with the clean data. Complementing these measures, the lowest LPIPS values (0.0010 and 0.0037) show that the poisoned images are also perceptually almost indistinguishable from their clean counterparts, reflecting strong visual concealment.

Overall, these results collectively demonstrate that the proposed attack achieves high stealthiness across multiple levels—pixel, structural, distributional, and perceptual—while maintaining effective attack performance.

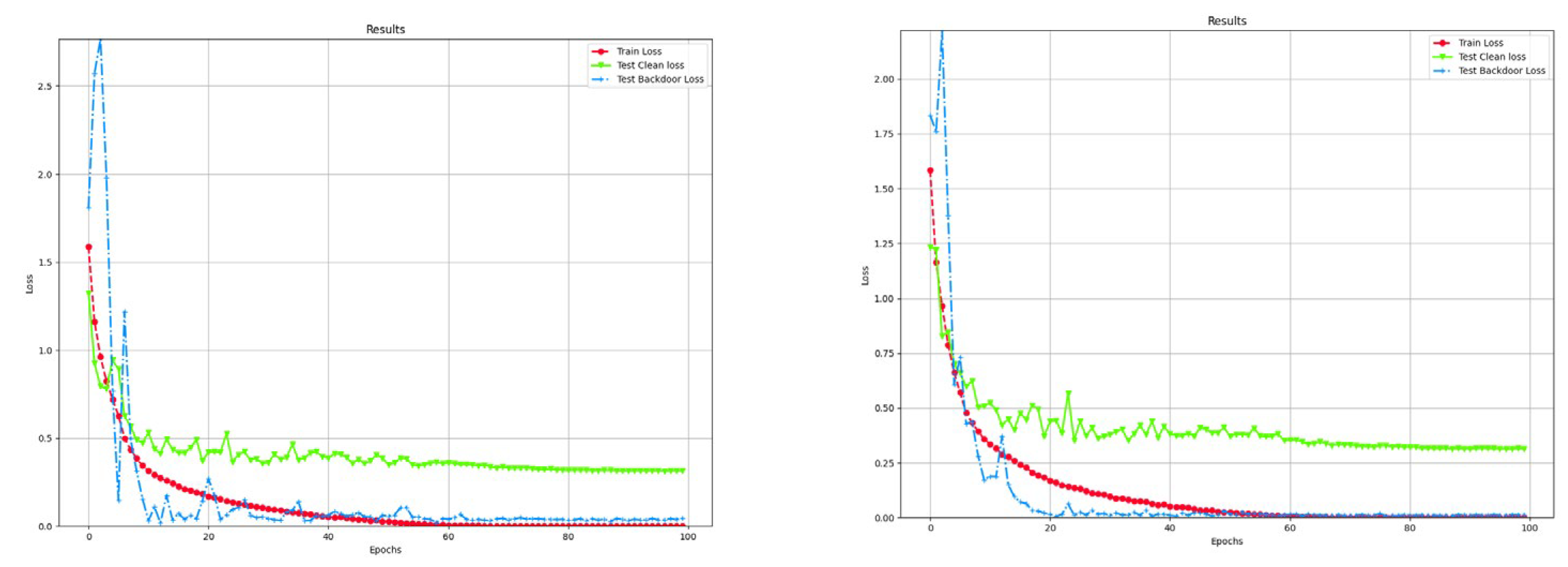

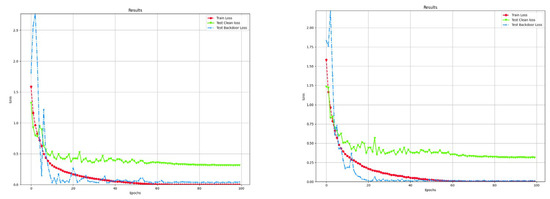

4.4.2. Dynamism Analysis

To evaluate the impact of dynamic embedding on model training, we conduct experiments using CIFAR-10 as a representative dataset, comparing dynamic and static embedding schemes under the same experimental settings. As shown in Figure 4, dynamic embedding exhibits slight fluctuations in training loss, clean loss, and backdoor loss curves, indicating a minor decrease in stability. However, both schemes show similar downward trends in loss and converge within comparable numbers of epochs. Static embedding converges around the 18th epoch, whereas dynamic embedding, due to the randomness of trigger positions, stabilizes around the 25th epoch.

Figure 4.

Training loss curves of dynamic (left) and static (right) embedding.

Table 7 summarizes the final performance metrics. The results indicate that dynamic embedding achieves clean accuracy (ACC) comparable to the static scheme, while the attack success rate (ASR) is slightly lower (dynamic 99.43 vs. static 99.73), suggesting that the position randomness introduces some fluctuations without significantly compromising the attack effectiveness. Overall, dynamic embedding achieves a favorable balance between reliability and randomness.

Table 7.

Dynamic vs. static embedding ACC/ASR/convergence.

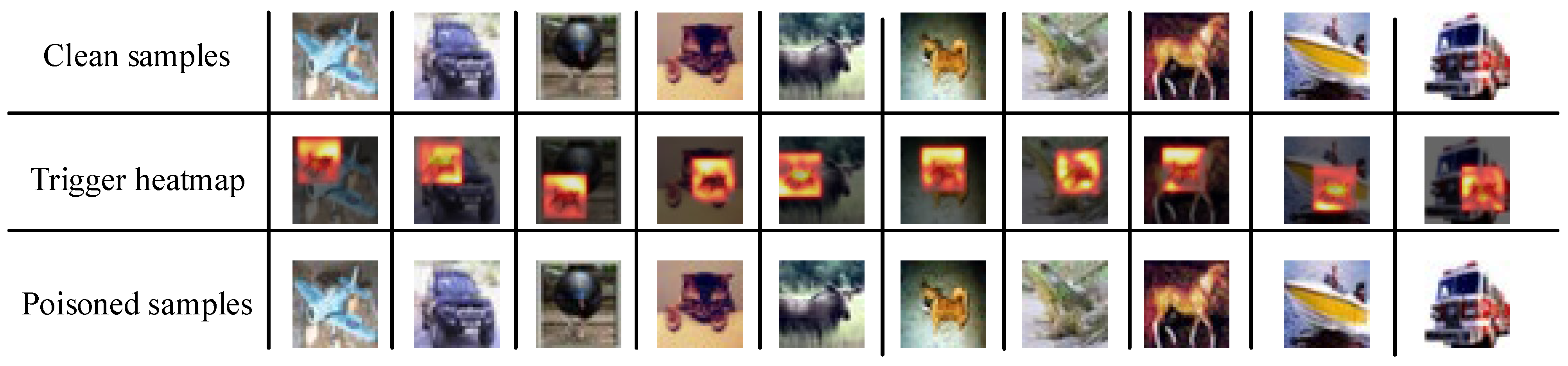

In addition, we visually demonstrate the core characteristics of the attack scheme by comparing clean and poisoned samples from the CIFAR-10 dataset and visualizing embedding positions. As shown in Figure 5, the first row displays the original clean samples of the 10 classes in CIFAR-10. The second row, labelled ‘Heatmap,’ illustrates the dynamic distribution characteristics of the trigger. Across different categories such as aeroplanes, cars, and birds, the trigger can randomly appear at the image edges, center, or any corner region (e.g., the aeroplane’s tail fin, car tyres, or bird backgrounds), exhibiting significant spatial randomness. The third row displays the corresponding poisoned samples. Visual comparison reveals minimal discernible differences, confirming the attack’s stealthiness. This dynamic embedding strategy visually validates the proposed approach’s advantages in visual concealment and positional randomness.

Figure 5.

Spatial distribution of clean samples, poisoned samples, and triggers in CIFAR-10 Dataset.

4.5. Ablation Experiments

To identify appropriate trigger sizes and embedding bit settings that balance attack effectiveness and stealth, we performed two-stage ablation studies on CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet. First, with the embedding bit fixed at 4, we swept candidate trigger image dimensions on each dataset and evaluated attack success rate (ASR) and concealability metrics (e.g., SSIM, PSNR and visual inspection). From this stage we selected 16 × 16 for CIFAR-10 and 28 × 28 for Tiny-ImageNet. Second, using the selected trigger sizes, we compared embedding bit numbers {1, 2, 3, 4} on both datasets; the results show that bit = 4 yields the best trade-off between ASR and stealth. Consequently, we use bit = 4 and trigger size 16 × 16 (CIFAR-10)/28 × 28 (Tiny-ImageNet) in subsequent experiments.

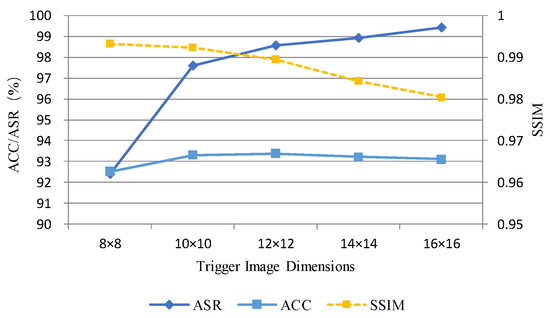

4.5.1. Trigger Image Dimension

- CIFAR-10 dataset

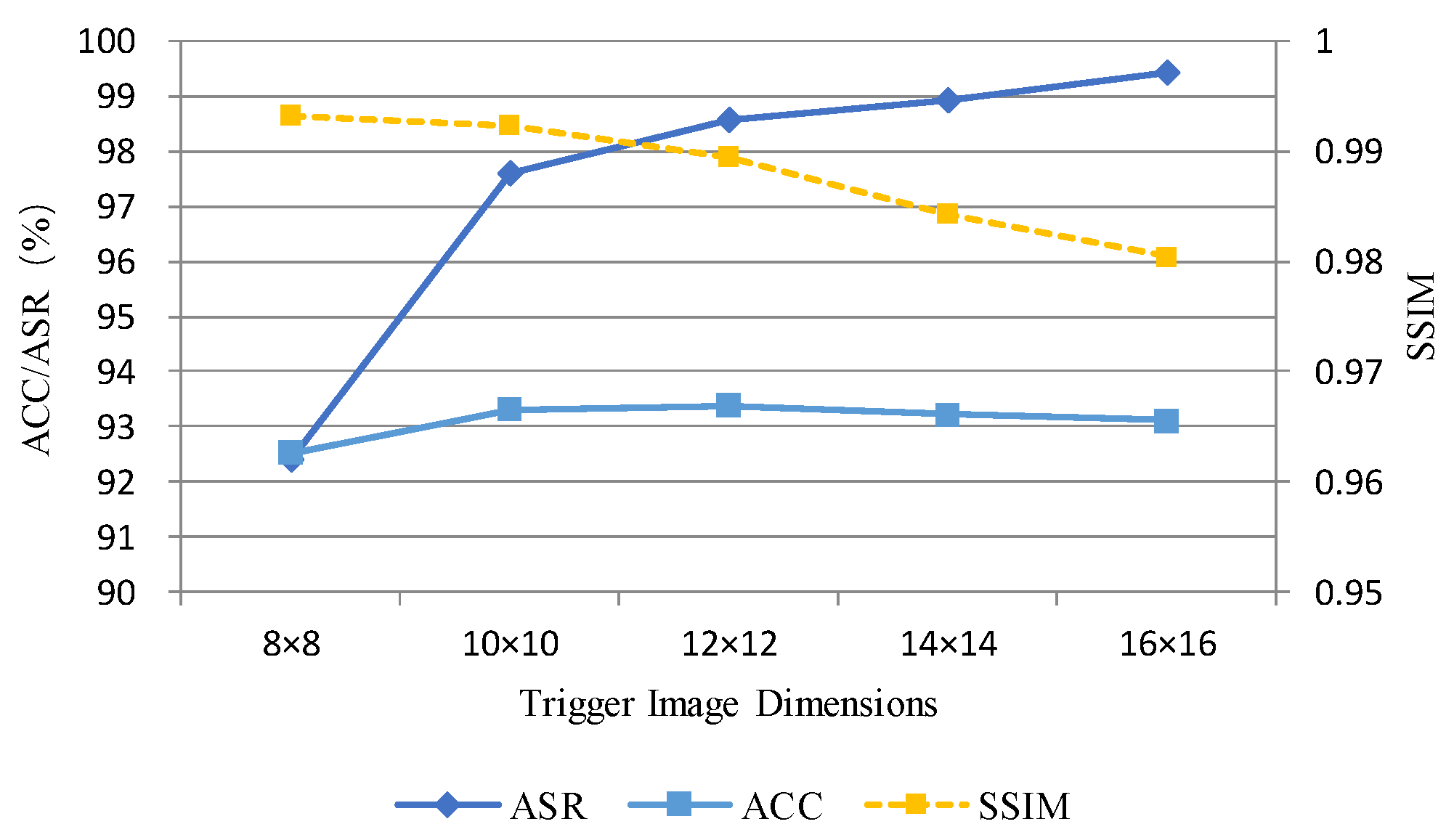

For the CIFAR-10 dataset, five trigger image sizes—8 × 8, 10 × 10, 12 × 12, 14 × 14, and 16 × 16—were selected. Analysis was conducted on the attack success rate (ASR), classification accuracy (ACC), and similarity index (SSIM) metrics for each group.

Figure 6 illustrates the impact of trigger image size on ASR, ACC, and SSIM for the CIFAR-10 dataset. The trendlines reveal that ASR increases with larger trigger image sizes, whereas SSIM decreases as trigger image sizes grow. As shown in Table 8, the recorded values indicate that when the trigger image size increases from 8 × 8 to 16 × 16, the ASR rises from 92.40% to 99.43%, while the SSIM decreases from 0.9932 to 0.9804. The ACC remains stable at approximately 93%. With the trigger image size set to 16 × 16, the corresponding ASR reaches 99.43%, ensuring the effectiveness of the backdoor attack. Simultaneously, it achieves an SSIM value of 0.9804, making it visually challenging to distinguish between clean and poisoned samples. Therefore, to balance attack success rate and stealthiness, this paper employs 16 × 16 trigger images in the CIFAR-10 dataset.

Figure 6.

Impact of trigger image size on ASR, ACC, and SSIM in CIFAR-10 dataset.

Table 8.

Impact of trigger image size on ASR, ACC, and SSIM in CIFAR-10 dataset.

- 2.

- Tiny-ImageNet dataset

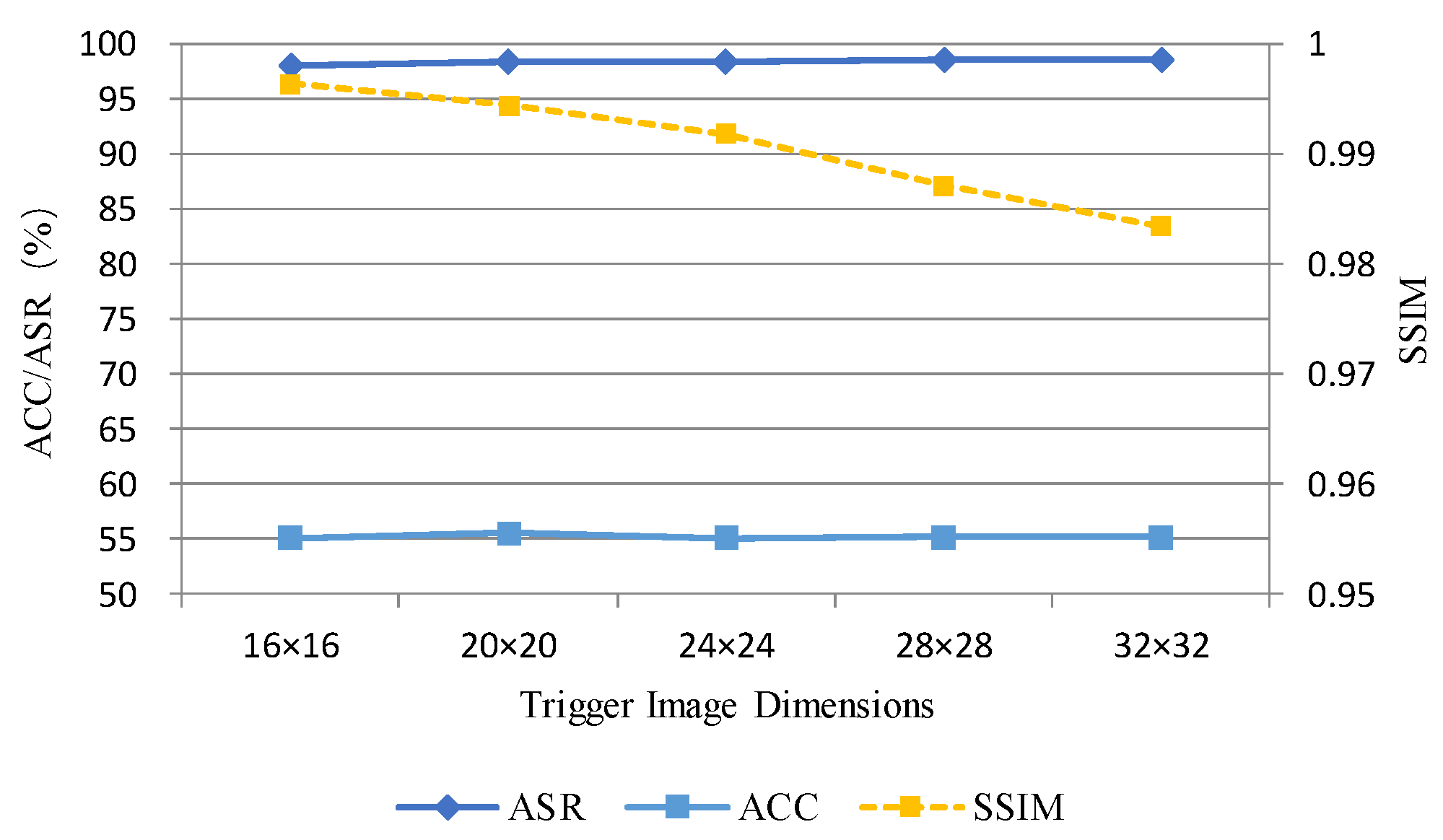

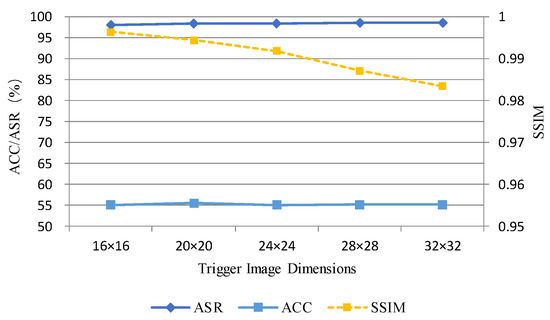

For the Tiny-ImageNet dataset, five trigger image sizes—16 × 16, 20 × 20, 24 × 24, 28 × 28, and 32 × 32—were selected. Analysis was conducted on each group’s attack success rate (ASR), classification accuracy (ACC), and similarity index (SSIM).

As evident from Table 9 and Figure 7, when the trigger size increased from 16 × 16 to 32 × 32 on the Tiny-ImageNet dataset, the ASR remained consistently above 98%, while the ACC generally stabilised around 55%. However, the SSIM gradually decreased with increasing size, indicating that larger triggers are more easily detectable within the image. Overall, a trigger size of 28 × 28 achieves the highest ASR (98.51%) while maintaining an SSIM of 0.9871, striking an optimal balance between attack success rate and concealment.

Table 9.

Impact of trigger image size on ASR, ACC, and SSIM in tiny-ImageNet dataset.

Figure 7.

Impact of trigger image size on ASR, ACC, and SSIM in tiny-ImageNet dataset.

Through experiments investigating trigger image dimensions on the CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet datasets, we observed that the optimal trade-off between attack success rate (ASR) and visual concealment (SSIM) occurs when the trigger occupies approximately 19–25% of the image area in our settings. Specifically, the 16 × 16 trigger on 32 × 32 CIFAR-10 images (25% of the area) and the 28 × 28 trigger on 64 × 64 Tiny-ImageNet images (19% of the area) both demonstrate high ASR and acceptable SSIM, as shown in Figure 6 and Figure 7. We emphasize that this range is an empirical observation based on our experimental configurations. The optimal trigger size may vary across datasets depending on image resolution, texture complexity, and embedding parameters. These findings indicate that moderate-sized triggers can balance attack effectiveness and stealthiness within our experimental scope.

4.5.2. Embedding Bit Numbers

We conducted ablation experiments to investigate the effect of different embedding bit numbers (1–4) on attack performance and visual imperceptibility. The experiments were performed on CIFAR-10 and Tiny ImageNet datasets using the previously determined trigger image sizes (16 × 16 for CIFAR-10 and 28 × 28 for Tiny ImageNet). The evaluation metrics include attack success rate (ASR), clean accuracy (ACC), and SSIM as a measure of visual similarity.

As shown in Table 10, increasing the embedding bit number significantly improves ASR for both datasets, but at the cost of slightly reduced visual similarity. In particular, bit = 4 achieves the highest ASR (99.43% for CIFAR-10, 98.51% for Tiny ImageNet) while maintaining acceptable SSIM values (0.9804 and 0.9871, respectively). Meanwhile, the clean accuracy also remains high. Therefore, 4-bit embedding provides the best trade-off between attack effectiveness and imperceptibility, and is adopted in the subsequent experiments.

Table 10.

Impact of embedding bit number on attack performance and visual imperceptibility.

4.5.3. Complementarity of LBP and PRNG

To quantify the contributions of LBP encoding and PRNG-based spatial randomization, we evaluate three variants of the proposed attack on CIFAR-10 with ResNet-18 backbone, and the results are summarized in Table 11.

Table 11.

Effect of LBP and PRNG on backdoor robustness.

- (1)

- V1—Plain LSB + PRNG: High bits of trigger pixels are embedded into carrier pixels with PRNG-based random start positions, without LBP encoding.

- (2)

- V2—LBP LSB static: Trigger pixels are replaced by their LBP-coded values and embedded at a fixed position (no PRNG).

- (3)

- V3—LBP LSB + PRNG: Full method, combining LBP-coded trigger with PRNG randomization (original proposed method).

Other settings (poisoning rate, optimizer, data augmentation, and training schedule) are kept identical to the main experiments.

- CIFAR-10 Ablation Analysis:

SPECTRE detection (FNR, False Negative Rate): V1 = 0.9584, V2 = 0.8359, V3 = 0.9404. The high FNR values indicate that SPECTRE fails to effectively detect backdoor samples in all three variants.

D-BR defense (ASR): V1 = 6.96%, V2 = 7.18%, V3 = 85.94%. D-BR strongly suppresses fixed LBP triggers (V2), while PRNG randomization alone (V1) is insufficient. Only the combination of LBP and PRNG (V3) maintains high ASR, demonstrating their complementary roles: LBP enhances local texture encoding of the trigger, and PRNG randomizes embedding positions to mitigate detectors relying on fixed-location patterns.

- 2.

- Tiny-ImageNet Analysis:

SPECTRE detection (FNR): V1 = 0.8454, V2 = 0.8072, V3 = 0.8944. High FNR again indicates that SPECTRE cannot effectively detect backdoor samples for any variant.

D-BR defense (ASR): V1 = 96.45%, V2 = 10.43%, V3 = 98.74%. Although V1 and V2 already achieve relatively high ASR on Tiny-ImageNet, V3 still clearly outperforms both V1 and V2, further validating the complementary effect of LBP and PRNG.

The difference in D-BR performance between CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet can be attributed to dataset characteristics. CIFAR-10 images are smaller and simpler, so low-bit LSB triggers are more vulnerable to D-BR, leading to low ASR for V1. In contrast, Tiny-ImageNet images are larger and more complex, allowing V1 triggers to survive better. Across datasets, the LBP + PRNG combination in V3 consistently achieves the highest robustness, demonstrating that enhancing local texture representation and randomizing embedding positions are key strategies for improving the defense robustness of backdoor attacks.

4.6. Defence Experiments

This section systematically evaluates the adversarial capabilities of the proposed method against existing mainstream backdoor defence mechanisms through experimental testing. To validate the robustness of the attack scheme in practical defence scenarios, we selected two backdoor detection and defence models—D-BR and SPECTRE—for experimentation.

4.6.1. D-BR Defence Experimental Methodology

The model’s robustness on clean data (RA) was evaluated under the D-BR (Distinguish-and-Remove Backdoor) defense. D-BR is a two-stage method: poisoned samples are first detected via feature transformation sensitivity, then backdoors are removed through alternating optimization. Key hyperparameters were ratio = 0.05, clean_ratio = 0.2, and poison_ratio = 0.05.

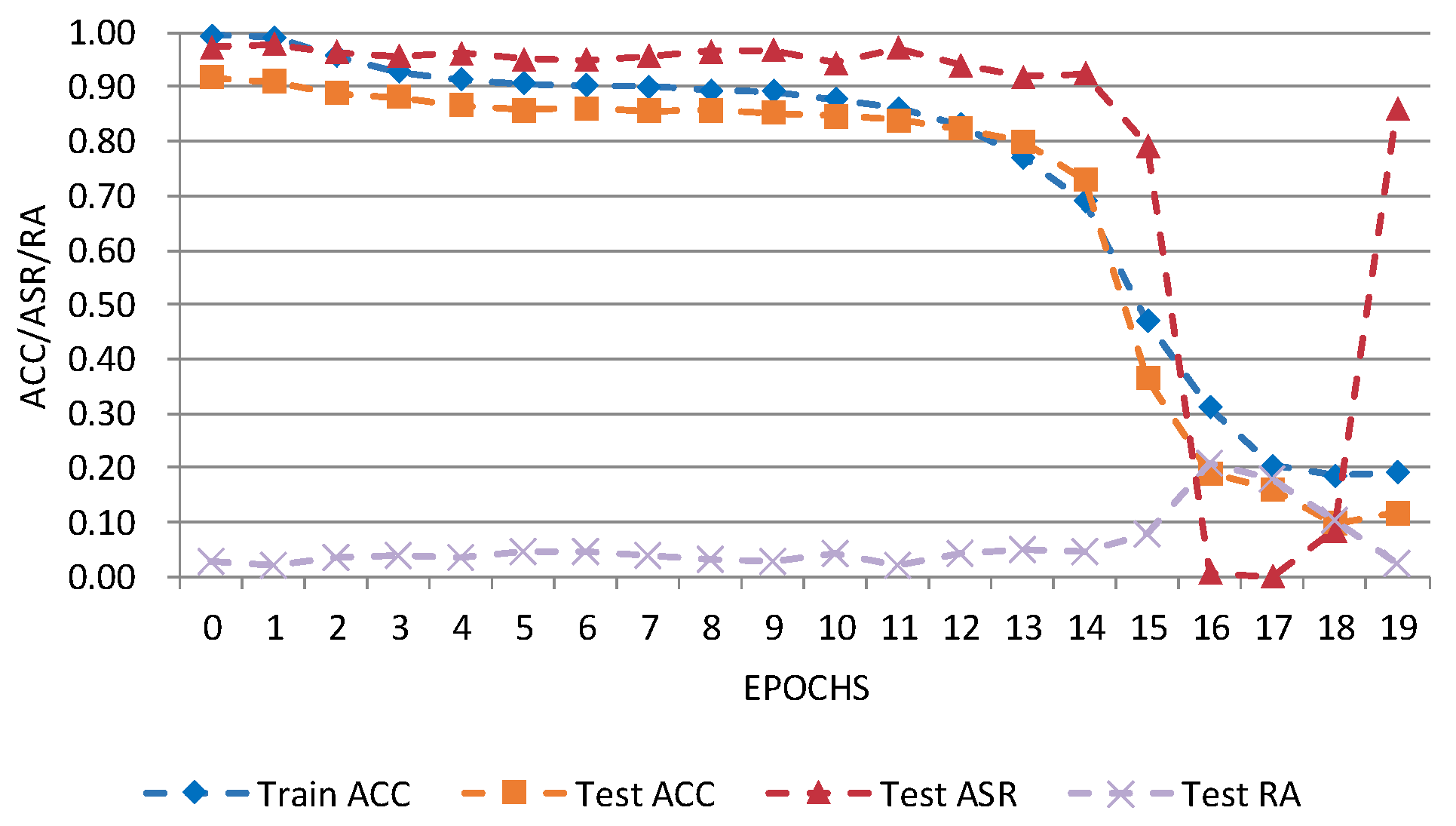

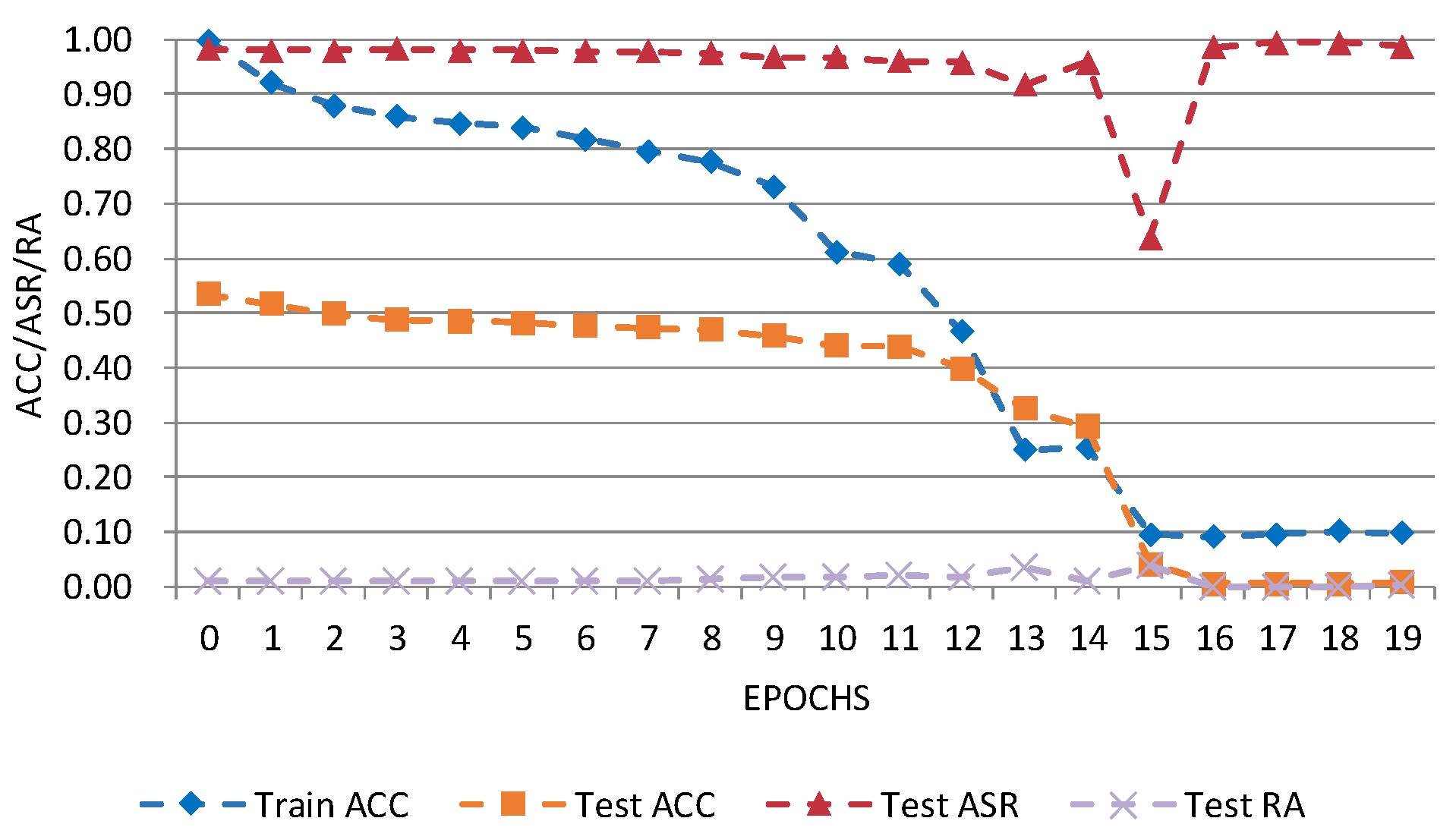

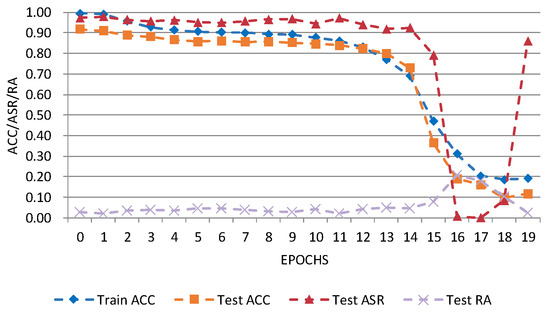

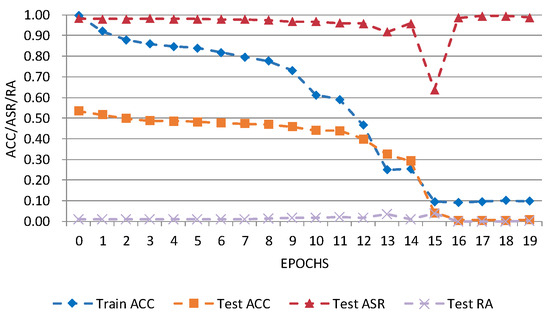

Figure 8 and Figure 9 show D-BR’s performance on CIFAR-10 and Tiny ImageNet. The attack success rate (Test_ASR) remains high, while robustness on clean data (Test_RA) is low. Short-term fluctuations during later training arise from D-BR’s dynamic weight adjustment and model sensitivity. Overall, the proposed attack remains effective under D-BR.

Figure 8.

D-BR detection results on CIFAR-10 dataset. Blue: Train ACC (accuracy on training data); Orange: Test ACC (accuracy on test data); Red: Test ASR (attack success rate); Purple: Test RA (robustness on clean data).

Figure 9.

D-BR detection results on Tiny-ImageNet dataset. Blue: Train ACC (accuracy on training data); Orange: Test ACC (accuracy on test data); Red: Test ASR (attack success rate); Purple: Test RA (robustness on clean data).

Table 12 compares ASR and ACC of different attacks under D-BR. On CIFAR-10, the proposed attack achieves an ASR of 85.94%, second only to WaNet (89.53%). On Tiny ImageNet, it attains an ASR of 98.74%, higher than all other attacks. These results indicate that the proposed attack remains effective under D-BR defense.

Table 12.

Performance comparison under D-BR defence (epoch 20).

4.6.2. SPECTRE Defence Experimental Methodology

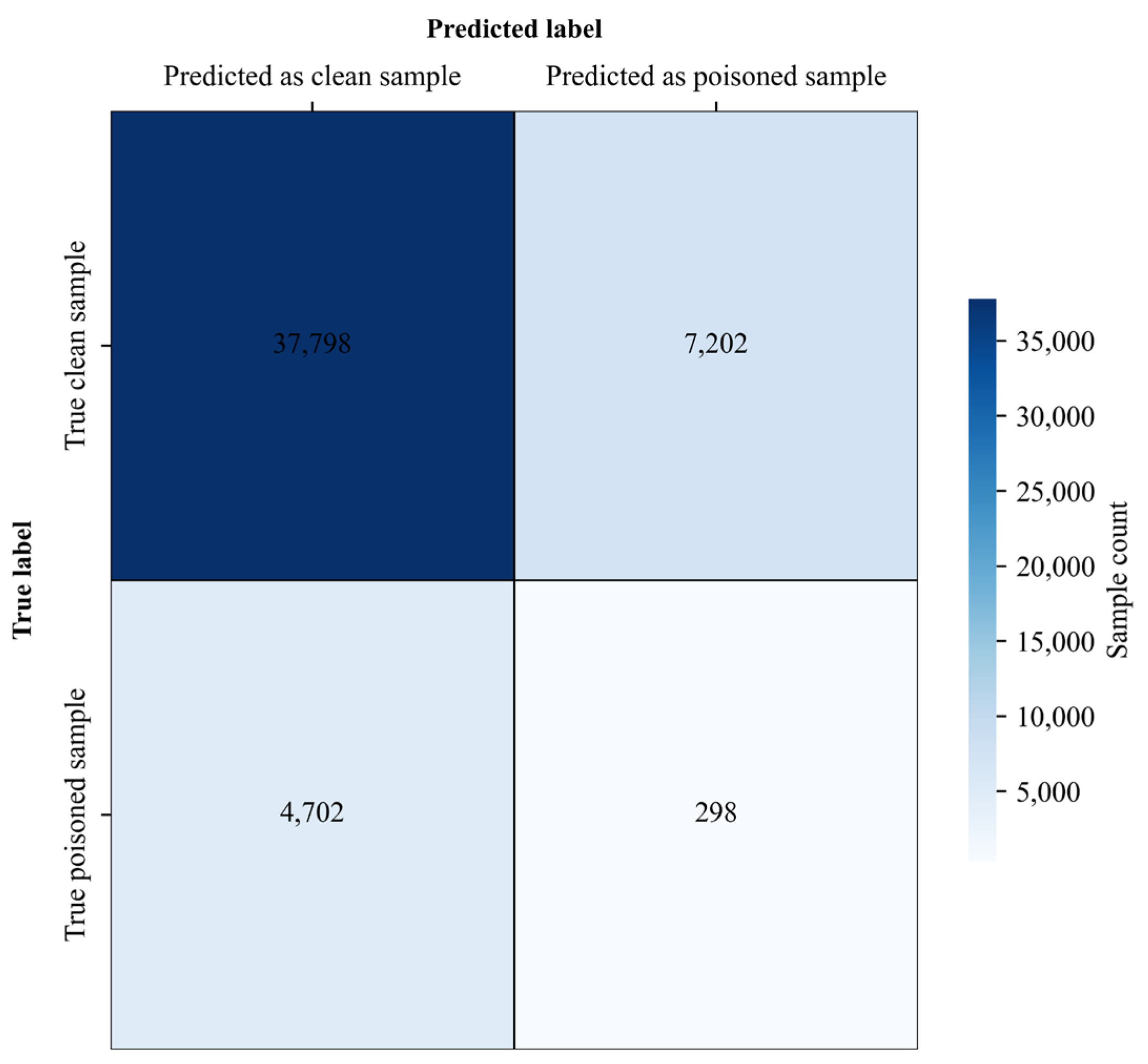

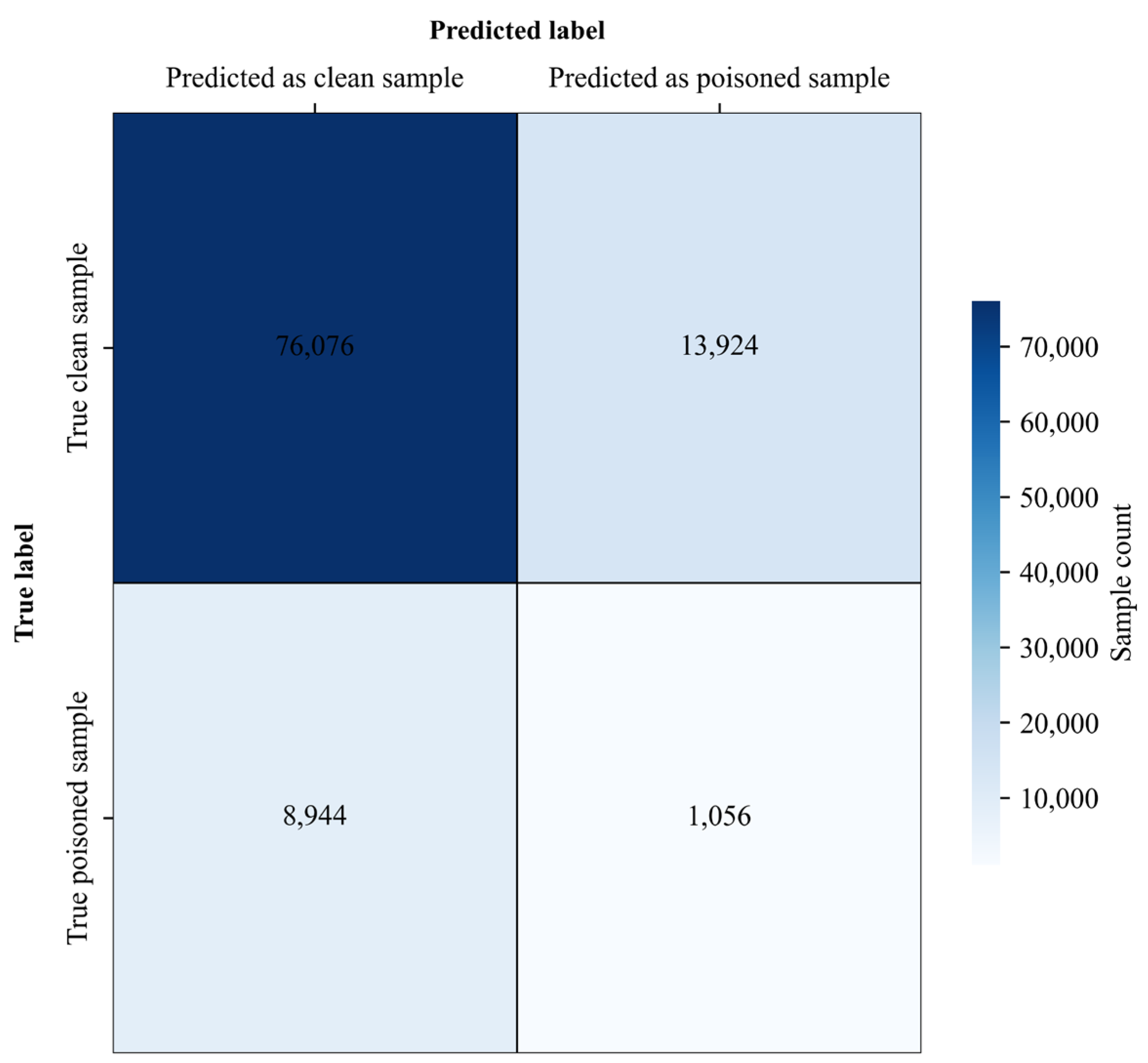

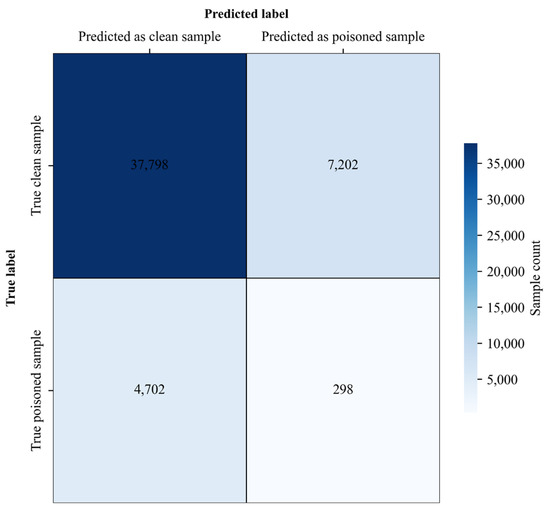

SPECTRE (Spectral Poison Excision Through Robust Estimation) is a robust statistical detection method that identifies potentially poisoned samples by analyzing spectral anomalies in the feature covariance space and attempts to mitigate their effects via robust estimation. Figure 10 and Figure 11 show SPECTRE’s performance against the proposed attack on CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet.

Figure 10.

SPECTRE Detection Results on CIFAR-10 Dataset.

Figure 11.

SPECTRE Detection Results on Tiny-ImageNet Dataset.

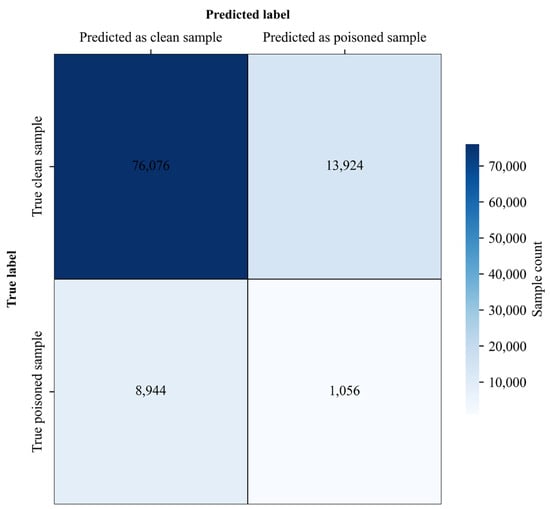

As summarized in Table 13, for CIFAR-10, SPECTRE detected 298 out of 5000 poisoned samples (TPR = 0.0596), missed 4702 (FNR = 0.9404), and incorrectly flagged 7202 out of 45,000 clean samples (FPR = 0.16). For Tiny-ImageNet, it detected 1056 out of 10,000 poisoned samples (TPR = 0.1056), missed 8944 (FNR = 0.8944), and misclassified 13,924 out of 90,000 clean samples (FPR = 0.1547).

Table 13.

Quantitative comparison of different attack methods under SPECTRE defence.

Table 11 also summarizes the FNR of different attacks under SPECTRE. On CIFAR-10, the proposed attack exhibits the highest FNR (0.9404), indicating it is the most likely to evade detection. On Tiny-ImageNet, its FNR (0.8944) is slightly lower than ReFool (0.8945), demonstrating the limited detection capability of SPECTRE against the proposed attack.

5. Conclusions

Addressing the limitations of existing invisible backdoor attacks—such as fixed trigger patterns that render them susceptible to detection—this paper proposes a dynamically randomized backdoor attack method based on the complementary use of LBP texture features and LSB steganography. By encoding local texture patterns with LBP and combining this with PRNG-randomized embedding positions, the method strengthens the robustness of the trigger under defensive perturbations while preserving visual invisibility via LSB low-bit steganography. Experiments on CIFAR-10 and Tiny-ImageNet datasets show that this approach achieves effective concealment, high attack success rates, and strong resistance to detection.

This method provides novel insights for covert backdoor design. Its dynamic triggers, enhanced by LBP-PRNG synergy, offer more robust evaluation benchmarks for defense methods. However, dynamic embedding may introduce additional random noise during model training; future work could further improve concealment through adaptive embedding region selection, such as edge-aware or saliency-driven strategies to insert triggers in high-frequency or salient regions, balancing invisibility and robustness. For defense, combining frequency domain analysis with LBP-based feature reconstruction is recommended to detect spectral anomalies caused by randomized triggers.

In addition, while this work focuses on image-based backdoor attacks, recent studies have highlighted the emergence of backdoor threats in Large Language Models (LLMs). Zhou et al. (2025) [27] provide a comprehensive survey of attack and defense methods in LLMs, emphasizing the unique challenges posed by sequential and contextual information. Yuan et al. (2025) [28] further demonstrate flexible and stealthy backdoor attacks in physical domains, which underscores the importance of evaluating dynamic, high-capacity triggers beyond conventional image datasets. Incorporating insights from LLM backdoor research can help guide future extensions of our method, potentially adapting dynamic embedding strategies to textual or multi-modal domains.

6. Limitations

While our method randomizes trigger embedding locations across different images to mitigate detectors that rely on fixed-position statistics, the embedded trigger content remains identical across all poisoned samples. This design makes location randomization effective against detectors relying solely on spatial cues, but it does not guarantee evasion from defenses that examine content consistency or model output/latent representation consistency. In our experiments, detectors such as STRIP, SCAN, and TeCo were able to identify the backdoor by exploiting output-entropy differences or clustering patterns in latent representations caused by the same trigger content. Therefore, although our approach demonstrates potential advantages in concealment and attack success, it has limitations against content-consistency-based defenses. Future work could explore strategies to reduce trigger-content consistency, such as semantic variations or context-aware transformations, while maintaining stealth.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.L.; Methodology, J.P.; Software, F.L.; Validation, F.L.; Formal analysis, F.L.; Investigation, F.L.; Resources, J.P.; Data curation, J.P.; Writing—original draft preparation, F.L.; Writing—review and editing, Z.L. and F.L.; Visualization, F.L.; Supervision, Z.L.; Project administration, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Li, L.; Mu, X.; Li, S.; Peng, H. A review of face recognition technology. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 139110–139120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zablocki, É.; Ben-Younes, H.; Pérez, P.; Cord, M. Explainability of deep vision-based autonomous driving systems: Review and challenges. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2022, 130, 2425–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhary, K.R.; Chowdhary, K.R. Natural language processing. In Fundamentals of Artificial Intelligence; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2020; pp. 603–649. [Google Scholar]

- Amit, Y.; Felzenszwalb, P.; Girshick, R. Object detection. In Computer Vision: A Reference Guide; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 875–883. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, T.; Liu, K.; Dolan-Gavitt, B.; Garg, S. Badnets: Evaluating backdooring attacks on deep neural networks. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 47230–47244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheddad, A.; Condell, J.; Curran, K.; Mc Kevitt, P. Digital image steganography: Survey and analysis of current methods. Signal Process. 2010, 90, 727–752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Xue, M.; Zhao, B.; Zhu, H.; Zhang, X. Invisible backdoor attacks on deep neural networks via steganography and regularization. IEEE Trans. Dependable Secur. Comput. 2020, 18, 2088–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Chen, S. A comparative study on local binary pattern (LBP) based face recognition: LBP histogram versus LBP image. Neurocomputing 2013, 120, 365–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kietzmann, P.; Schmidt, T.C.; Wählisch, M. A guideline on pseudorandom number generation (PRNG) in the IoT. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2021, 54, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Zhu, C.; Wang, W. A new image encryption algorithm based on chaos and secure hash SHA-256. Entropy 2018, 20, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Liu, C.; Li, B.; Lu, K.; Song, D. Targeted backdoor attacks on deep learning systems using data poisoning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.05526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, A.; Tran, A. Wanet--imperceptible warping-based backdoor attack. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.10369. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Bailey, J.; Lu, F. Reflection backdoor: A natural backdoor attack on deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 182–199. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, Y.; Park, W.; Mao, Z.M.; Jia, R. Rethinking the backdoor attacks’ triggers: A frequency perspective. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, QC, Canada, 10–17 October 2021; pp. 16473–16481. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Lyu, X.; Koren, N.; Lyu, L.; Li, B.; Ma, X. Anti-backdoor learning: Training clean models on poisoned data. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 14900–14912. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Wu, B.; Wang, H. Effective backdoor defense by exploiting sensitivity of poisoned samples. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 9727–9737. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, B.; Li, J.; Madry, A. Spectral signatures in backdoor attacks. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Montréal, QC, Canada, 3–8 December 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Y.; Xu, C.; Wang, D.; Chen, S.; Ranasinghe, D.C.; Nepal, S. Strip: A defence against trojan attacks on deep neural networks. In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Computer Security Applications Conference, San Juan, PR, USA, 9–13 December 2019; pp. 113–125. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, D.; Wang, X.F.; Tang, H.; Zhang, K. Demon in the variant: Statistical analysis of {DNNs} for robust backdoor contamination detection. In Proceedings of the 30th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 21), Virtual Event, 11–13 August 2021; pp. 1541–1558. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, E.; Tramer, F.; Pellegrino, G. Sentinet: Detecting localized universal attacks against deep learning systems. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Security and Privacy Workshops (SPW), San Francisco, CA, USA, 21 May 2020; pp. 48–54. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Li, M.; Wang, H.; Hu, S.; Ye, D.; Jin, H.; Wu, L.; Xiao, C. Detecting backdoors during the inference stage based on corruption robustness consistency. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 16363–16372. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, Z.; Wei, S.; Yuan, D.; Zhu, M.; Wang, R.; Liu, L.; Shen, C. Backdoorbench: A comprehensive benchmark of backdoor learning. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 10546–10559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanchenko, A. Visual-PSNR measure of image quality. J. Vis. Commun. Image Represent. 2014, 25, 874–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakurov, I.; Buzzelli, M.; Schettini, R.; Castelli, M.; Vanneschi, L. Structural similarity index (SSIM) revisited: A data-driven approach. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 189, 116087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasumana, S.; Ramalingam, S.; Veit, A.; Glasner, D.; Chakrabarti, A.; Kumar, S. Rethinking fid: Towards a better evaluation metric for image generation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 9307–9315. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, R.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A.; Shechtman, E.; Wang, O. The unreasonable effectiveness of deep features as a perceptual metric. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 586–595. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Y.; Ni, T.; Lee, W.B.; Zhao, Q. A Survey on Backdoor Threats in Large Language Models (LLMs): Attacks, Defenses, and Evaluation Methods. Trans. Artif. Intell. 2025, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Xu, G.; Li, H.; Zhang, R.; Qian, X.; Jiang, W.; Cao, H.; Zhao, Q. FIGhost: Fluorescent Ink-based Stealthy and Flexible Backdoor Attacks on Physical Traffic Sign Recognition. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.12045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).