1. Introduction

Light field imaging enables the reconstruction of 3D information by capturing both spatial and angular information [

1,

2]. Due to this property, light field imaging has been applied in various fields [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, to extend its applications further, the angular resolution of light field imaging needs to be improved. One of the primary challenges in this task is processing a large number of views. This requirement substantially increases the number of network parameters. In addition, parallax between views complicates the reconstruction process. Moreover, factors such as light reflections and occlusions make the restoration process more difficult. Consequently, enhancing light field resolution remains a highly challenging problem.

Conventional view synthesis methods [

9,

10,

11,

12,

13] generate novel views using classical approaches. Geometry-based techniques [

9,

11] use estimated depth or disparity maps to guide pixel rearrangement. They perform well in simple scenes but have difficulty handling occlusions, complex lighting, or strong reflections. To address these limitations, Zhou et al. [

14] proposed learning an appearance mapping from input images via appearance flow, thus avoiding explicit depth estimation. While this method can yield high-quality reconstructions under favorable conditions, it is still challenged by occlusions and regions not visible in the input views. Moreover, its reliance on flow-based warping limits flexibility in handling novel pixels and complex scenes.

Recently, deep learning-based methods [

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26] have been introduced for light field reconstruction. These approaches are categorized into depth-based and non-depth-based methods. Depth-based methods generate novel views by predicting a depth map from the input images. However, inaccurate depth estimation causes problems that reduce the quality of the novel view. Non-depth-based methods can avoid these issues since they do not rely on depth maps. However, due to the inherent complexity of light field, the quality of the reconstructed images remains limited. To overcome this limitation, non-depth-based approaches focus on efficiently utilizing the intrinsic information across light field views without relying on explicit depth estimation.

In our previous work, we proposed Prex-Net [

27], which progressively fused feature maps across views using a modified back-projection structure [

28]. We extend our previous approach and propose Prex-NetII, an improved algorithm for high-quality light field reconstruction. Unlike our previous network [

27], Prex-NetII employs pixel shuffle and spatial attention for initial feature extraction. The pixel shuffle approach efficiently aggregates multi-view information with fewer parameters than 3D convolution.

In addition, the spatial attention module improves the network’s capacity to capture spatial correlations across sub-aperture images. Furthermore, channel attention is incorporated into the up- and down-projection modules within the refinement network to better exploit inter-view dependencies and underlying 3D structural information. To further stabilize training and improve reconstruction performance, long skip connections are applied before and after the refinement network. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

Efficiently extracts the initial feature map using pixel shuffle, reducing the number of parameters compared to our previous work.

Enhanced training stability achieved by adopting long skip connections around the refinement network.

Improved cross-view representation through attention mechanisms that better capture structural dependencies across views.

2. Related Works

A common strategy for synthesizing novel views is to predict a depth map and warp the input images. The accuracy of the estimated depth map directly determines the quality of the resulting views. Traditional depth-based light field reconstruction methods have explored various approaches. Wanner and Goldluecke [

9] introduced a variational framework for disparity estimation and angular super-resolution, deriving disparity maps from local slope estimations to generate warp maps. However, this approach is limited to local regions and shows reduced performance in areas with complex structures or strong specular reflections. Mitra and Veeraraghavan [

10] proposed a patch-based method using Gaussian mixture model to model disparity patterns, integrating patches to reconstruct high-resolution light field images. This method struggles when the patch sizes are smaller than the maximum disparity in the light field.

With the introduction of deep learning, CNN-based methods have been applied to light field reconstruction. Flynn et al. [

15] demonstrated a method for synthesizing novel views from wide-baseline stereo images, providing guidelines for disparity-based CNN synthesis. However, generating views using only two input images limits the total number of novel views. Kalantari et al. [

16] proposed a framework that estimates depth from densely sampled light field images, warps the inputs accordingly, and refines intermediate synthesis images through color estimation. Although effective, this method requires cropping boundary regions due to missing data in warped inputs and is computationally expensive when producing multiple views. Jin et al. (LFASR-geometry) [

17] addressed speed limitations by predicting multiple depth maps simultaneously, but remaining inaccuracies in depth estimation still cause distortions. Jin et al. (LFASR-FS-GAF) [

18] further enhanced intermediate synthesis by incorporating attention maps and plane sweep volumes (PSVs), improving synthesis quality, but limitations remain in improving the accuracy of depth maps. Chen et al. [

19] proposed a hybrid method that combines depth-based and non-depth-based synthesis through region-wise disparity guidance. However, it still suffers from detail loss and artifacts due to disparity estimation errors.

Several methods reconstruct light fields without estimating depth explicitly, relying on structural cues or frequency-domain information instead. Shi et al. [

12] restored the sparsity of light field images in the Fourier domain via nonlinear gradient descent, although their approach required specific sampling along image borders and diagonals. Vagharshakyan et al. [

13] applied adaptive discrete shearlet transforms and EPI-based inpainting, but sequential synthesis along axes slowed processing and limited occlusion handling.

As in depth-based methods, CNN-based models have been proposed to reconstruct light fields without explicit depth estimation. Yoon et al. [

20] proposed a network to synthesize an intermediate view from two adjacent views, but it had a limitation in the location of synthesized views. Gul and Gunturk [

21] fed lenslet stacks into a network to achieve angular super-resolution more efficiently, yet simple architectures caused quality degradation. Wu et al. [

22] reconstructed light fields via EPIs using a blur-restoration-deblur framework, but the reconstruction failed for scenes with disparities beyond a certain range. To address this, Wu et al. [

23] proposed a shear-aware light field reconstruction network that integrates learnable shearing, downscaling, and prefiltering into the rendering process. It reduces aliasing in epipolar-plane images by processing and fusing multiple sheared inputs. Wang et al. (DistgASR) [

24] combined MacPI structures and multiple filters to extract spatial and angular features simultaneously, achieving high quality with minor inference delays. Fang et al. (GLGNet) [

25] proposed an EPI-based framework that incorporates a bilateral upsampling module to perform angular super-resolution at arbitrary interpolation rates. However, the method tends to lose fine details in scenes with complex textures. Salem et al. (LFR-DFE) [

26] integrated dual feature extraction and macro-pixel upsampling, producing high-quality reconstructions under sparse inputs, but the approach struggled with complex occlusion boundaries.

In summary, inaccurate depth estimation causes distortions in the reconstructed views of depth-based methods. Although non-depth-based approaches can avoid this issue, they still suffer from image artifacts and loss of fine details in regions with complex occlusions or reflections. This is because existing models have difficulty capturing the spatial–angular relationships required for accurate reconstruction. To solve these problems, we propose an attention-based back-projection network that enhances feature interaction across views and improves reconstruction quality.

3. Proposed Network

The proposed network consists of an initial feature extraction network and a refinement network. The initial feature extraction network integrates spatial and angular information from multiple input views. It generates a fused feature representation of the corner sub-aperture images through pixel shuffle. This allows the use of 2D convolutions to capture spatio-angular dependencies with a low computational cost. A spatial attention module is then applied to focus on informative regions. The initial feature map is then fed into the refinement network for reconstruction. The refinement network adopts a back-projection structure to refine the extracted features. The refinement network consists of multiple up- and down-projection blocks that reduce reconstruction errors and recover fine spatial details while maintaining consistency across views.

As shown in

Figure 1, the initial feature extraction network concatenates corner images

,

,

, and

of the 7 × 7 light field image to create

, where

H and

W are the height and width of light field images, respectively. Then,

is rearranged to

by pixel shuffle, where

r is the upscaling factor and is set to 2. Consequently, the input images of the four corners are rearranged into a single-channel feature map with double the spatial resolution. This allows the network to efficiently extract spatio-angular features from multiple images using only 2D convolution.

The pixel-shuffled image passes through 2D convolution layers of 256, 128, 64, 49, and 49 with 3 × 3 kernels. The spatial attention module is inserted after the first convolution layer to improve spatial features. As a result, the initial feature map is obtained. The stride and padding of all convolution layers are set to 1, except for the last layer. To match the spatial resolution of the initial feature map and the input light field image, the stride of the last convolution layer is set to 2 and the padding is set to 1. Each convolution layer is followed by LeakyReLU with a negative slope of 0.01.

In the spatial attention module, the input feature map is processed through both average and max pooling to produce two spatial maps. These maps are concatenated and passed to a 2D convolution layer with a 7 × 7 kernel, stride 1, and padding 1. This layer generates the spatial attention map. The 7 × 7 kernel size is adopted to provide a wider receptive field for capturing long-range spatial correlations. The attention map is normalized using a sigmoid activation and multiplied with the original feature map to obtain spatially refined features. The structure of the spatial attention module is shown in

Figure 2.

To capture the inherent correlations in the initial feature map, we introduce a refinement network based on a back-projection structure [

28]. As shown in

Figure 1, the up- and down-projection blocks of the refinement network are densely connected to each other. The first up-projection block takes the initial feature map as input. The subsequent up-projection blocks concatenate the outputs of the down-projection blocks from the previous stage and use them as input. Similarly, the first down-projection block takes the output of the first up-projection block as input, and the following down-projection blocks concatenate the outputs of the up-projection blocks from the previous stage and use them as input.

The input of the last convolution layer is the concatenated outputs of the down-projection blocks. The last convolution layer has a filter size of 3 × 3 and is not followed by an ReLU. Finally, the output feature map of the refinement network is added to the initial feature map , via a long skip connection, to generate the final reconstructed light field images. This long skip connection helps to improve the quality of the reconstructed light field images and enables stable training of the proposed network.

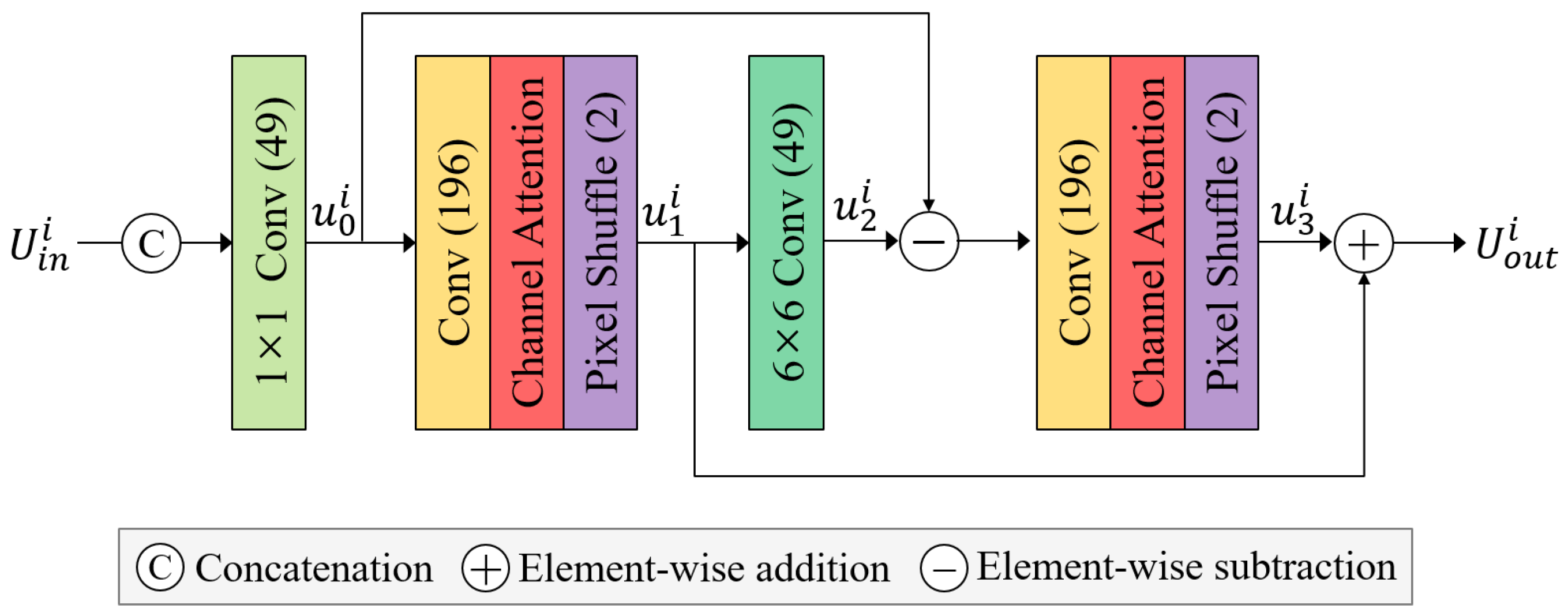

3.1. Up-Projection Bock

The up-projection block is shown in

Figure 3. The input feature map

of the up-projection block is the initial feature map or the concatenated outputs of the down-projection blocks. It can be expressed as

where

i represents the

i-th block. As

i increases, the number of channels of the input feature map

increases by

. Therefore, a 1 × 1 convolution layer is employed to set the channel number of the input feature map

to 49. The following 3 × 3 convolution layer expands the 49-channel feature map to a 196-channel feature map. The expanded 196-channel feature map is passed through a channel attention module to assign weights to each channel. This expanded feature map enhances feature representation and captures more complex spatial relationships. Subsequently, the feature map is rearranged into a 49-channel feature map

using pixel shuffle with an upscaling factor of 2. The pixel-shuffled 49-channel feature map

is processed by a 6 × 6 convolution layer with a stride of 2 and padding of 2. This operation produces a 49-channel feature map

with spatial resolution matching that of the input light field image. The feature map

becomes a residual feature map by subtracting

. This 49-channel residual feature map passes through a 3 × 3 convolution layer for channel expansion and pixel shuffle with an upscaling factor of 2. Each convolution layer is followed by LeakyReLU with a negative slope of 0.2. The resulting

is then added to

to produce

. The final output of the up-projection block can be expressed as

where

. Here,

represents the LeakyReLU activation function,

denotes the pixel shuffle operation, and

denotes the channel attention module, while

and

refer to

and

convolution layers, respectively.

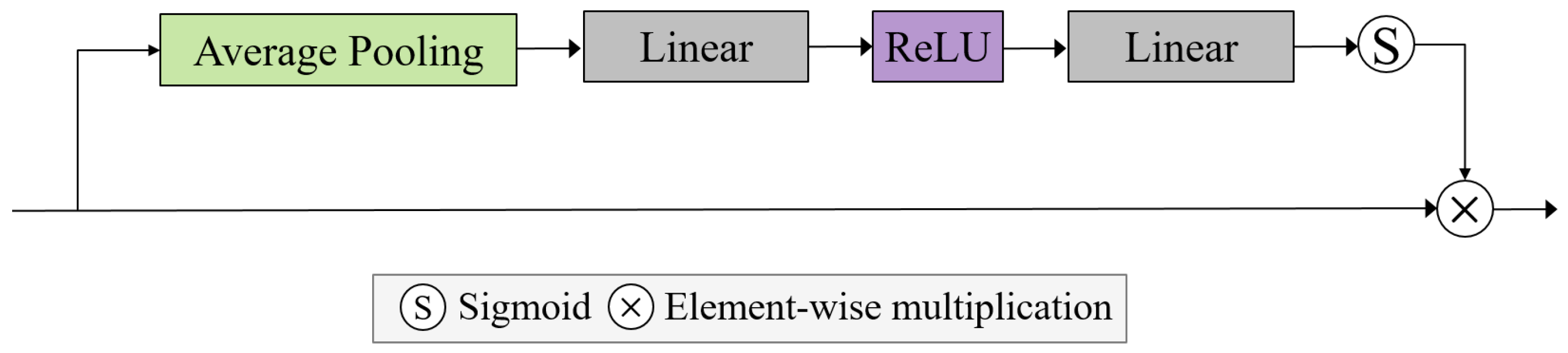

The channel attention module is shown in

Figure 4. First, a feature map with 196 channels is input and compressed into a channel-wise descriptor by applying average pooling. Although max pooling can also be used in this step, we used only average pooling to reduce the computational cost. The average-pooled feature map with a shape of (196 × 1 × 1) is passed through two fully connected layers to generate the attention map, where the reduction ratio is set to 14. Here, the feature dimension is reduced from 196 to 14 and then expanded back to 196. This enables the network to learn channel-wise weights that represent the importance of each channel. An ReLU activation is applied between the layers. The resulting attention map is normalized using a sigmoid activation function and then multiplied element-wise with the input feature map. This produces the final channel-attended feature representation.

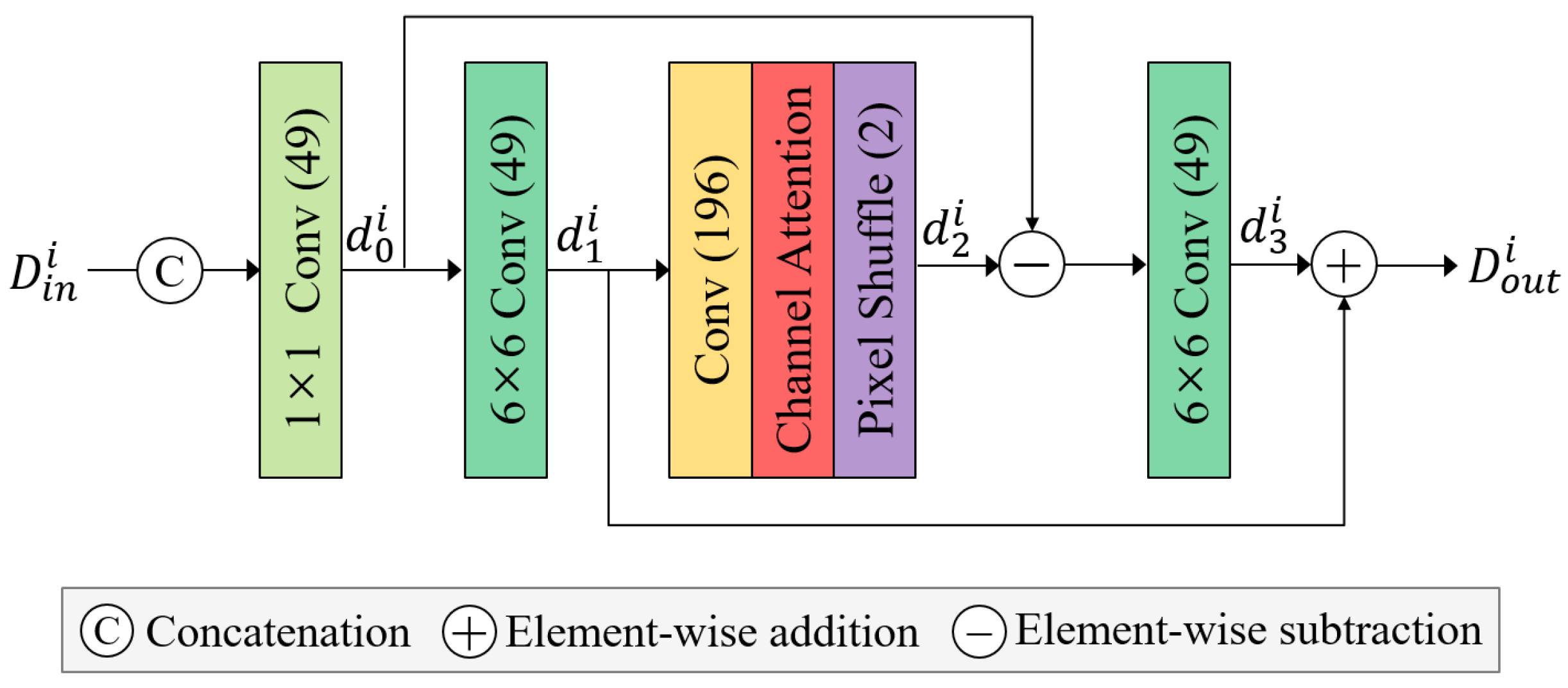

3.2. Down-Projection Bock

The down-projection block is shown in

Figure 5. The input feature map

of the down-projection block is the concatenated outputs of the up-projection blocks. It can be expressed as

Similar to the up-projection block, each increment in

i increases the channels of the input feature map for the down-projection block by

. Therefore, a 1 × 1 convolution layer is employed to set the channel number of the input feature map

to 49. Unlike the up-projection block, the spatial resolution of the feature map

is double that of the input light field image. Therefore, we resize it using a 6 × 6 convolution layer with a stride of 2 and padding of 2. The 49-channel feature map

is expanded to 196-channel feature map using a 3 × 3 convolution layer. The 196-channel feature map is then passed through the channel attention module and subsequently rearranged into a 49-channel feature map

by pixel shuffle with an upscaling factor of 2. The 49-channel feature map

becomes a residual feature map by subtracting the feature map

previously generated by the 1 × 1 convolution layer. This 49-channel residual feature map passes through a 6 × 6 convolution layer to match the spatial resolution of the input light field image. It is then added to

to produce the output of the down-projection block. It can be expressed as

4. Simulation Results

For training, we used the Stanford Lytro light field archive [

29] and the Kalantari dataset [

16]. These datasets have an angular resolution of 14 × 14 and a spatial resolution of 376 × 541. We used only the 7 × 7 light field images from the center of the 14 × 14 light field images. We converted RGB color images to YCbCr color images and conducted experiments using only luminance. For testing, we used real-world light field images named 30Scenes [

16], Occlusions [

29], and Reflective [

29] datasets. The 30Scenes dataset consists of general images, the Occlusions dataset contains images with overlapping objects, and the Reflective dataset includes images with reflective areas. In particular, light field images with occlusions or diffuse reflections make it difficult to predict the pixels of the reconstructed light field images. We evaluated the performance of the proposed method using datasets with various characteristics.

We used randomly cropped patches with a spatial resolution of 96 × 96 for training, and the cropped patch was augmented by flipping and rotation. To avoid memory limitation issues, the batch size was set to 1. For optimization, we used Adam optimizer with

. The learning rate was initialized as

and decreased to

by

every 5000 epochs. The proposed network was trained using the Charbonnier loss [

30], which minimizes the error between the original high-resolution (HR) light field image and the reconstructed light field image. This loss function is adopted for its robustness to outliers and its smooth approximation of the

norm. The loss is defined as

where

and

denote the ground-truth and predicted HR light field images, respectively. The value of

is set to

, which is commonly used in image reconstruction tasks.

To evaluate the performance of the proposed method, various metrics were compared with those of existing approaches.

Table 1 presents the PSNR comparison results. Non-depth-based methods [

24,

26,

27] achieve better performance than early depth-based approaches [

16,

18] as they reconstruct images directly without relying on depth estimation. On average, the PSNR of the proposed method was 2.33 dB, 1.44 dB, 0.61 dB, 0.38 dB, and 0.27 dB higher than that of Kalantari et al. [

16], LFASR-FS-GAF [

18], DistgASR [

24], Prex-Net [

27], and LFR-DFE [

26], respectively. The proposed method consistently outperformed competing approaches across the entire dataset, regardless of its characteristics.

To analyze the influence of the number of projection blocks, we conducted experiments by varying the number of blocks in the refinement network. All models were trained under identical conditions, and their reconstruction performance was evaluated in terms of PSNR and SSIM. As shown in

Table 2, the performance improved as the number of projection blocks increased. However, as the number of projection blocks increased, the performance gain gradually decreased. We determined the optimal number of up- and down-projection blocks to be 12 for each, considering the trade-off between performance and model parameters. In addition, the proposed model achieved better performance while reducing the number of parameters compared to our previous work [

27].

We conducted a series of experiments to validate the effectiveness of the proposed method. This ablation study was conducted to evaluate the contribution of the applied attention blocks to performance improvement. We applied different attention modules to the initial feature extraction and projection blocks. As shown in

Table 3, the results indicate that the best performance was achieved when spatial attention was applied at the initial feature extraction stage and channel attention was integrated within the projection block.

Spatial attention applied at an early stage helped the network to focus on relevant regions in the input image, improving spatial feature learning. Channel attention within the projection block refined the features by strengthening channel-wise correlations, which led to improved reconstruction performance.

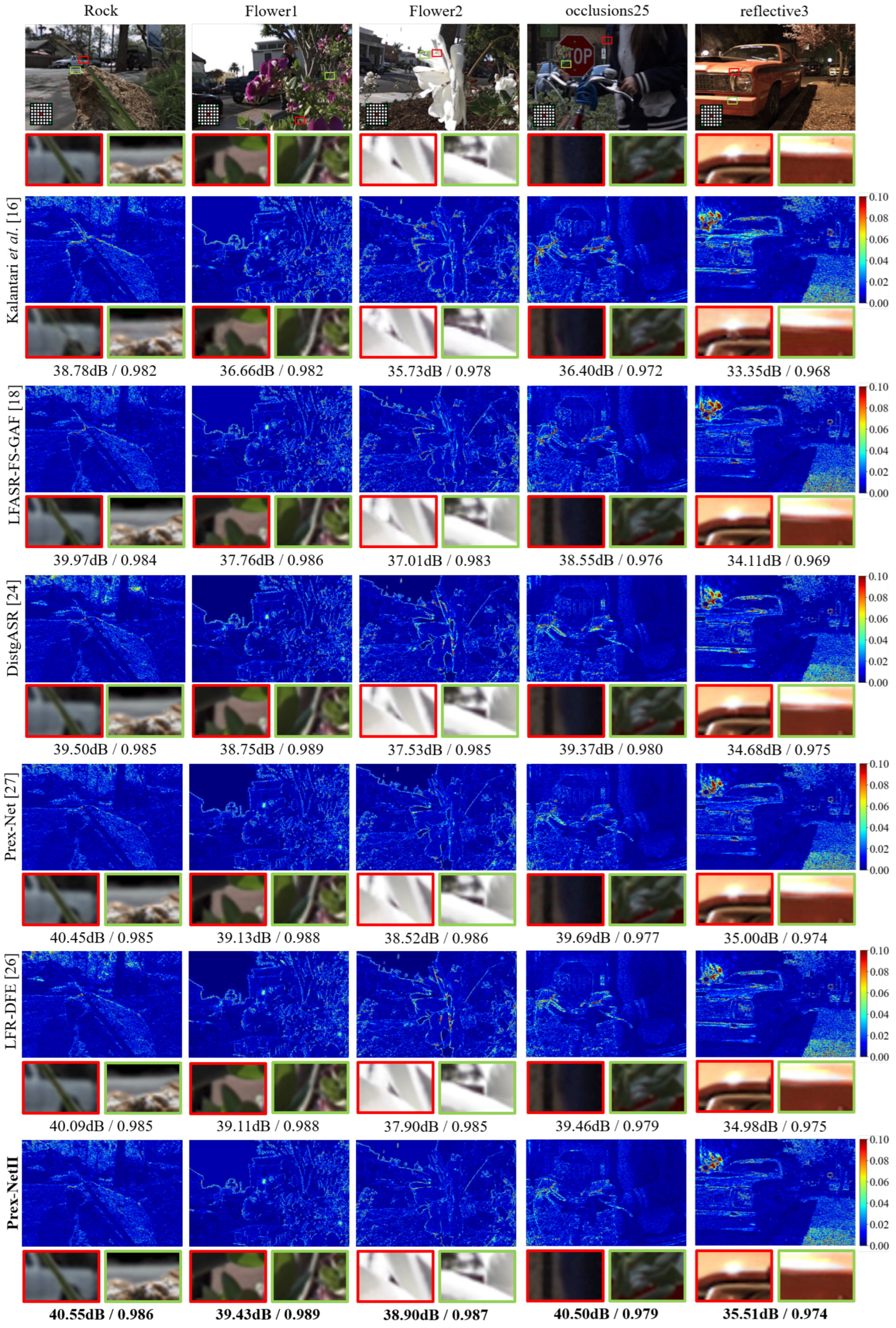

Figure 6 presents a comparison between the proposed method and existing methods using both error maps and cropped image regions. The error maps show the pixel-wise differences between the reconstructed and ground-truth images. Smaller errors are shown in blue, while larger errors are shown in red. For clearer comparison, error values were clipped to the range of 0 to 0.1, with values above 0.1 truncated to 0.1. As shown in

Figure 6, the proposed method more accurately reconstructs the ground-truth images than existing methods.

Methods that rely on depth maps reconstruct light field images by warping input views based on estimated depth. As shown in

Figure 6, blur or artifacts can be seen because the predicted depth map is inaccurate. In contrast, methods that do not rely on depth maps avoid such issues. However, the figure shows that they may not fully exploit angular correlations in the light field data, which leads to reduced texture quality.

For example, in the first cropped region of the Flower2 scene, the proposed method recovers the background object between the petals more accurately than existing methods. In the second crop of the Occlusion25 scene, the proposed method recovers leaf textures more clearly than existing methods. This indicates that the proposed method provides consistently higher-quality reconstructions across these examples. In the first crop of the Reflective3 scene, the proposed method restores reflected light that closely matches the ground truth. Additionally, in the second crop of the same scene, existing methods tend to produce unwanted white lines in reflective regions due to interference from neighboring regions. The results show that the proposed method is more robust in handling reflections.