Enhancing JPEG XL’s Weighted Average Predictor: Genetic Algorithm Optimization of Expanded Sub-Predictor Ensemble

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. System Overview

2.2. Original Predictors

2.3. Predictor Enhancement

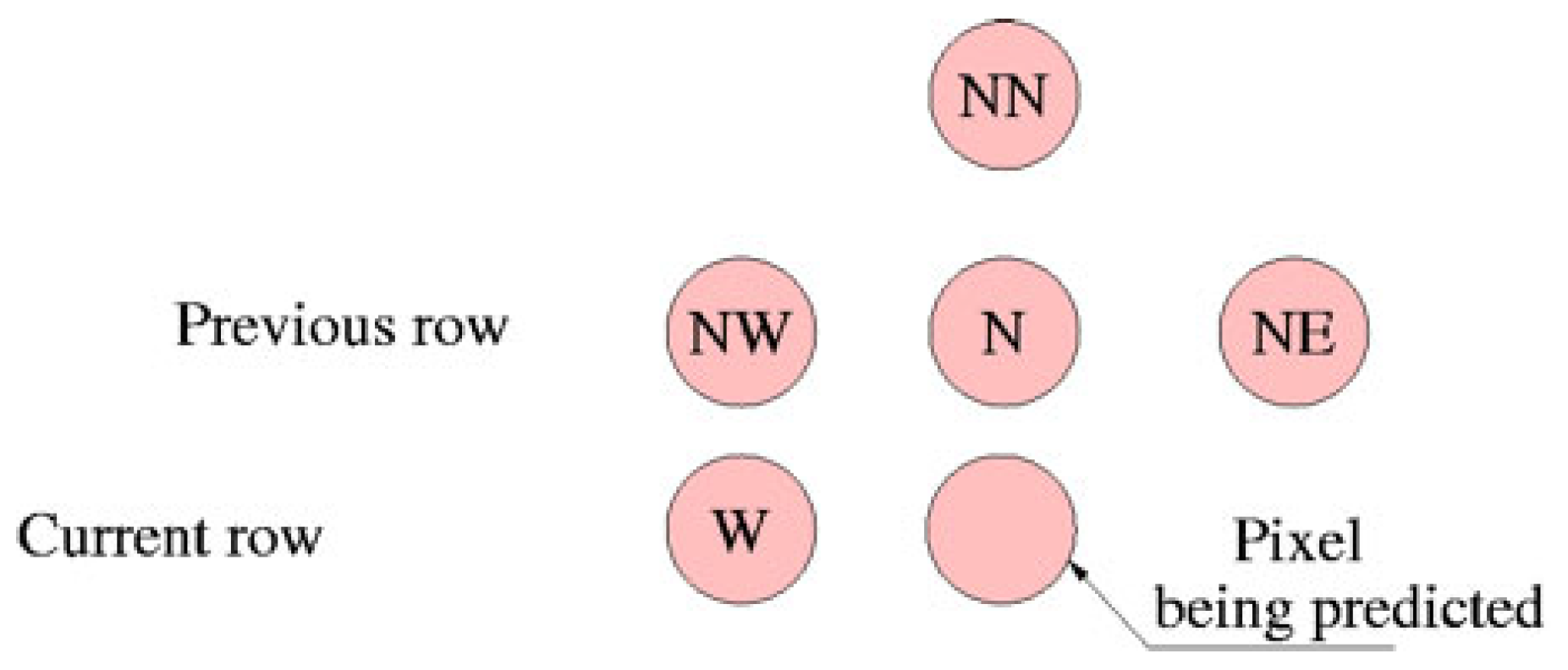

- Adaptive MED predictor: This predictor was selected for its established role as the core predictor in the JPEG-LS standard [3]. Weinberger et al. [3] demonstrated that MED provides competitive compression performance while maintaining low computational complexity through its simple edge detection mechanism. MED tends to pick N in cases where a vertical edge exists left of the current location, W in cases of a horizontal edge above the current location, or W + N − NW if no edge is detected. The traditional MED predictor was augmented with error correction capabilities.

- Adaptive Median predictor: This predictor implements a computationally efficient approach that incorporates error feedback mechanisms. Building upon the median filter’s inherent robustness, it adds adaptive error correction capabilities to improve the prediction accuracy. This predictor calculates the median of W, N, and NW pixels, whereas the adaptive MED predictor also considers edges. The adaptive nature of these first two additional predictors is based on a dynamic error-correcting mechanism that is utilized by the original sub-predictors of the weighted average predictor [9].

- Paeth predictor: We selected this predictor for its proven prediction reliability in the PNG standard [16]. The Paeth predictor uses the formula (W + N − NW) to estimate pixel values by selecting from the neighboring pixel (W, N, or NW) closest to this computed value [16]. The Paeth predictor offers a unique computational approach that complements the strengths of our prediction ensemble.

- Simplified GAP-based predictor: This predictor was incorporated due to its documented success in the CALIC algorithm, where it demonstrated superior prediction accuracy compared with simpler predictors [5]. The GAP (gradient-adjusted prediction) predictor utilizes W, NW, N, NE, and NN. It first estimates the local horizontal (|W − NW| + |N − NN|) and vertical (|N − NW| + |N − NE|) gradients. This estimation simplifies the original GAP estimation, which also relies on WW and NNE pixels. Next, three heuristic-defined thresholds that utilize the estimated local horizontal and vertical gradients are used to obtain the value of the predicted pixel. This context-aware approach allows it to switch between different prediction strategies based on local image characteristics, making it particularly effective at preserving sharp edges while maintaining accuracy in smooth regions [5].

2.4. WOP8 Core Algorithm

| Algorithm 1. WOP8 (weighted optimization predictor for 8 sub-predictors) |

| Algorithm: WOP8 Predict |

| INPUT: pixel_position(x,y), neighboring_pixels(W, NW, N, NE, and NN), ga_optimized_weights [8] OUTPUT: predicted_pixel_value BEGIN // Initialize adaptive weights using GA-optimized initial values FOR each predictor i in [0 to 7]: weights[i] ← CalculateAdaptiveWeight(ga_optimized_weights[i]) END FOR // Original JPEG XL predictors (0–3) predictions[0] ← GradientPredictor(W, NE, N) predictions[1] ← AdaptiveNorthPredictor(N) predictions[2] ← AdaptiveWestPredictor(W) predictions[3] ← AdaptiveMulticontextPredictor(N) // New WOP8 predictors (4–7) // MED with error feedback predictions[4] ← AdaptiveMEDPredictor(N, W, NW) // Robust median prediction predictions[5] ← EnhancedMedianPredictor(N, W, NW) // PNG-style predictor predictions[6] ← PaethPredictor(N, W, NW) // Gradient-adjusted prediction predictions[7] ← GAPPredictor(W, NW, N, NE, NN) // Compute weighted average using GA-optimized weights final_prediction ← WeightedAverage(predictions[0…7], weights[0…7]) RETURN final_prediction END |

2.5. Modified Weighted Average Predictor Implementation

2.6. Initial Weight Optimization

2.7. Genetic Algorithm Implementation

| Algorithm 2. Genetic Algorithm Weight Optimizer |

| Algorithm: GA OptimizeWeights |

| INPUT: training_dataset, population_size, generations, mutation_rate, crossover_rate OUTPUT: optimal_weight_configuration [8] BEGIN population ← InitializeRandomPopulation(population_size) best_solution ← null best_fitness ← negative_infinity FOR each generation in [0 to generations-1]: fitness_scores ← empty_list // Evaluate compression performance for each weight configuration FOR each candidate in the population: compression_improvement ← TestCompressionRatio(candidate, training_dataset) fitness ← CalculateFitness(compression_improvement) ADD fitness to fitness_scores IF fitness > best_fitness: best_fitness ← fitness best_solution ← candidate END IF END FOR // Preserve elite solutions elite_candidates ← SelectTopPerformers(population, fitness_scores) next_generation ← elite_candidates // Generate offspring through selection and reproduction WHILE population not full: parent_a ← TournamentSelection(population, fitness_scores) parent_b ← TournamentSelection(population, fitness_scores) IF random_probability < crossover_rate: offspring ← UniformCrossover(parent_a, parent_b) ELSE offspring ← parent_a END IF offspring ← ApplyMutation(offspring, mutation_rate) ADD offspring to next_generation END WHILE population ← next_generation END FOR RETURN best_solution END |

2.8. Weight Integration

3. Implementation Setup and Results

3.1. Experimental Design

3.1.1. Dataset Selection and Validation

3.1.2. Data Partitioning

3.1.3. Baseline Measurements

3.1.4. Training and Evaluation Process

3.1.5. Implementation

3.1.6. Computing Environment

3.2. Compression Performance Analysis

3.3. Generalizability Validation

3.4. Computational Performance Analysis

3.5. Genetic Algorithm Parameter Optimization

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Compression Performance Results

4.1.1. Mechanisms of WOP8 Compression Improvement

4.1.2. Significance of Weighted Average Predictor Improvements

4.1.3. Scope and Validation of the Enhancement Approach

4.2. Genetic Algorithm Effectiveness and Predictor Optimization

4.3. Limitations and Future Works

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| GA | Genetic algorithm |

| WOP8 | Weighted optimization predictor for 8 sub-predictors |

| MA Tree | Meta-adaptive tree |

| GAP | Gradient-adjusted prediction |

| MED | Median edge detector |

References

- Hussain, A.J.; Al-Fayadh, A.; Radi, N. Image compression techniques: A survey in lossless and lossy algorithms. Neurocomputing 2018, 300, 44–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungureanu, I.; Negirla, P.; Korodi, A. Image-compression techniques: Classical and “region-of-interest-based” approaches presented in recent papers. Sensors 2024, 24, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weinberger, M.J.; Seroussi, G.; Sapiro, G. The LOCO-I lossless image compression algorithm: Principles and standardization into JPEG-LS. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2000, 9, 1309–1324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Wide Web Consortium. Portable Network Graphics (PNG) Specification, 2nd ed.; World Wide Web Consortium: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2003; Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/2003/REC-PNG-20031110/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Wu, X.; Memon, N. CALIC—A context-based adaptive lossless image codec. In Proceedings of the 1996 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech, and Signal Processing, Atlanta, GA, USA, 7–10 May 1996; Volume 4, pp. 1890–1893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alakuijala, J.; Sneyers, J.; Versari, L.; Wassenberg, J. JPEG White Paper: JPEG XL Image Coding System; Version 2.0; ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 29/WG1: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://ds.jpeg.org/whitepapers/jpeg-xl-whitepaper.pdf (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- JPEG XL Encode Effort Documentation. Available online: https://github.com/libjxl/libjxl/blob/main/doc/encode_effort.md (accessed on 15 July 2025).

- Rhatushnyak, A.; Wassenberg, J.; Sneyers, J.; Alakuijala, J.; Vandevenne, L.; Versari, L.; Obryk, R.; Szabadka, Z.; Kliuchnikov, E.; Comșa, I.-M.; et al. JPEG XL Image Coding System; Committee Draft ISO/IEC 18181; ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 29/WG1: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019; Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1908.03565 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Rhatushnyak, A.; Wassenberg, J.; Sneyers, J.; Alakuijala, J.; Vandevenne, L.; Versari, L.; Obryk, R.; Szabadka, Z.; Kliuchnikov, E.; Comșa, I.-M.; et al. JPEG XL Reference Implementation; Software; 2019. Available online: http://gitlab.com/wg1/jpeg-xl (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Holland, J.H. Adaptation in Natural and Artificial Systems, 1st ed.; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, D.E. Genetic Algorithms in Search, Optimization, and Machine Learning, 1st ed.; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, S.K.; Murthy, C.A.; Kundu, M.K. Technique for fractal image compression using genetic algorithm. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 1998, 7, 586–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, B.V.; Karpagam, G.R.; Naresh, S.P. Generation of JPEG quantization table using real coded quantum genetic algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2016 International Conference on Communication and Signal Processing, Melmaruvathur, India, 6–8 April 2016; pp. 1705–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, W.; Chan, K.-H. A Multilayer CARU Framework to Obtain Probability Distribution for Paragraph-Based Sentiment Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 11344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Z.; Lam, C.-T.; Yuan, X.; Im, S.-K.; Machado, P. MMQW: Multi-Modal Quantum Watermarking Scheme. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Security 2024, 19, 5181–5195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paeth, A.W. Image File Compression Made Easy. In Graphics Gems 2; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1991; pp. 93–100. ISBN 0-12-064480-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- W-OP8 Genetic Algorithm Implementation. Available online: https://github.com/xavierhillroy/libjxl-wop8/blob/main/W-OP8/src/genetic_algorithm/genetic_algorithm.py (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- Baluja, S. Removing the Genetics from the Standard Genetic Algorithm; Technical Report; Carnegie Mellon University: Pittsburgh, PA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hill Roy, X. W-OP8: JPEG XL Lossless Optimization with Genetic Algorithm-Optimized Predictor Weights; Software; 2025. Available online: https://github.com/xavierhillroy/libjxl-wop8 (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Sundararajan, V.; Ayswarya, S. Genetic algorithm-based feature selection for effective data classification—A survey. Information 2019, 10, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodak Lossless True Color Image Suite. Available online: http://r0k.us/graphics/kodak/ (accessed on 3 October 2024).

- Asuni, N.; Giachetti, A. TESTIMAGES: A Large Data Archive For Display and Algorithm Testing. J. Graph. Tools 2015, 17, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asuni, N.; Giachetti, A. TESTIMAGES: A large-scale archive for testing visual devices and basic image processing algorithms. In Proceedings of the STAG—Smart Tools & Apps for Graphics Conference, Verona, Italy, 8–9 October 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Python Software Foundation. Python Random Library. Available online: https://docs.python.org/3/library/random.html (accessed on 8 May 2025).

- W-OP8 Core Processor Implementation. Available online: https://github.com/xavierhillroy/libjxl-wop8/blob/main/W-OP8/src/core/processor.py (accessed on 28 August 2025).

- W-OP8 System Documentation. Available online: https://github.com/xavierhillroy/libjxl-wop8/blob/main/W-OP8/docs/W-OP8_System_Documentation.md (accessed on 28 August 2025).

| Effort Level | Predictor Configuration | Other Key Features |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fixed ClampedGradient predictor | Fast-lossless, fixed YCoCg RCT, simple palette detection |

| 2 | Fixed ClampedGradient predictor | Global channel palette, fixed MA tree |

| 3 | Fixed weighted predictor | Fixed the MA tree with WP-error context |

| 4 | ClampedGradient + weighted predictor, learned MA tree | Global palette |

| 5 | Same as effort level 4 | Patches, local palette/channel palette |

| 6 | Same as effort level 5 | More RCTs and MA tree properties |

| 7 | Same as effort level 6 | Additional RCTs and MA tree properties |

| 8 | Same as effort level 7 | Enhanced RCTs, MA tree properties, and more weighted predictor parameters |

| Effort Level | Baseline BPP | WOP8 BPP | Difference BPP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 8.85 | 8.61 | 0.24 |

| 7 | 8.91 | 8.67 | 0.24 |

| 6 | 9.05 | 8.85 | 0.20 |

| 5 | 9.23 | 9.14 | 0.09 |

| 4 | 9.40 | 9.31 | 0.09 |

| 3 | 9.46 | 9.36 | 0.10 |

| 2 | 10.33 | 10.33 | 0.00 |

| Effort Level | Baseline BPP | WOP8 BPP | Difference BPP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 8.61 | 8.55 | 0.06 |

| 7 | 8.65 | 8.58 | 0.07 |

| 6 | 8.81 | 8.74 | 0.07 |

| 5 | 9.20 | 9.16 | 0.04 |

| 4 | 9.39 | 9.36 | 0.03 |

| 3 | 9.46 | 9.36 | 0.10 |

| 2 | 10.33 | 10.33 | 0.00 |

| Effort Level | Baseline BPP | WOP8 BPP | Difference BPP |

|---|---|---|---|

| 8 | 8.52 | 8.46 | 0.06 |

| 7 | 8.66 | 8.57 | 0.09 |

| 6 | 8.79 | 8.70 | 0.09 |

| 5 | 8.88 | 8.80 | 0.08 |

| 4 | 9.22 | 9.14 | 0.08 |

| 3 | 9.25 | 9.17 | 0.08 |

| 2 | 10.33 | 10.33 | 0.00 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hill Roy, X.; El-Sakka, M.R. Enhancing JPEG XL’s Weighted Average Predictor: Genetic Algorithm Optimization of Expanded Sub-Predictor Ensemble. Electronics 2025, 14, 4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204116

Hill Roy X, El-Sakka MR. Enhancing JPEG XL’s Weighted Average Predictor: Genetic Algorithm Optimization of Expanded Sub-Predictor Ensemble. Electronics. 2025; 14(20):4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204116

Chicago/Turabian StyleHill Roy, Xavier, and Mahmoud R. El-Sakka. 2025. "Enhancing JPEG XL’s Weighted Average Predictor: Genetic Algorithm Optimization of Expanded Sub-Predictor Ensemble" Electronics 14, no. 20: 4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204116

APA StyleHill Roy, X., & El-Sakka, M. R. (2025). Enhancing JPEG XL’s Weighted Average Predictor: Genetic Algorithm Optimization of Expanded Sub-Predictor Ensemble. Electronics, 14(20), 4116. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14204116