Recent Advances in Sliding Mode Control Techniques for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- A concise overview of PMSM dynamics and the fundamental principles of SMC;

- (2)

- A thorough review of SMC design, including Reaching Law methods, Sliding Surface design, Second-Order SMC, Arbitrary-Order SMC, as well as both classical and advanced control strategies;

- (3)

- An in-depth discussion of Observer-Integrated SMC and Intelligent SMC incorporating advanced control techniques;

- (4)

- An assessment of open challenges and identification of potential directions for future research.

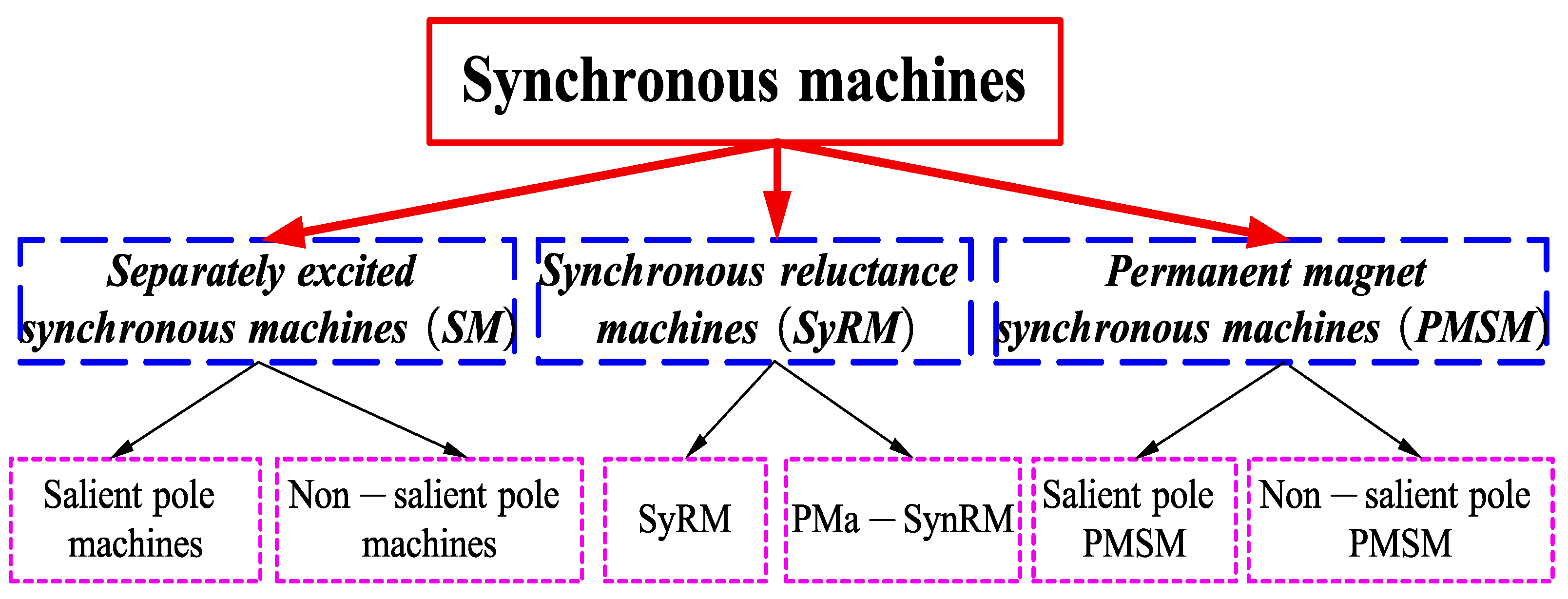

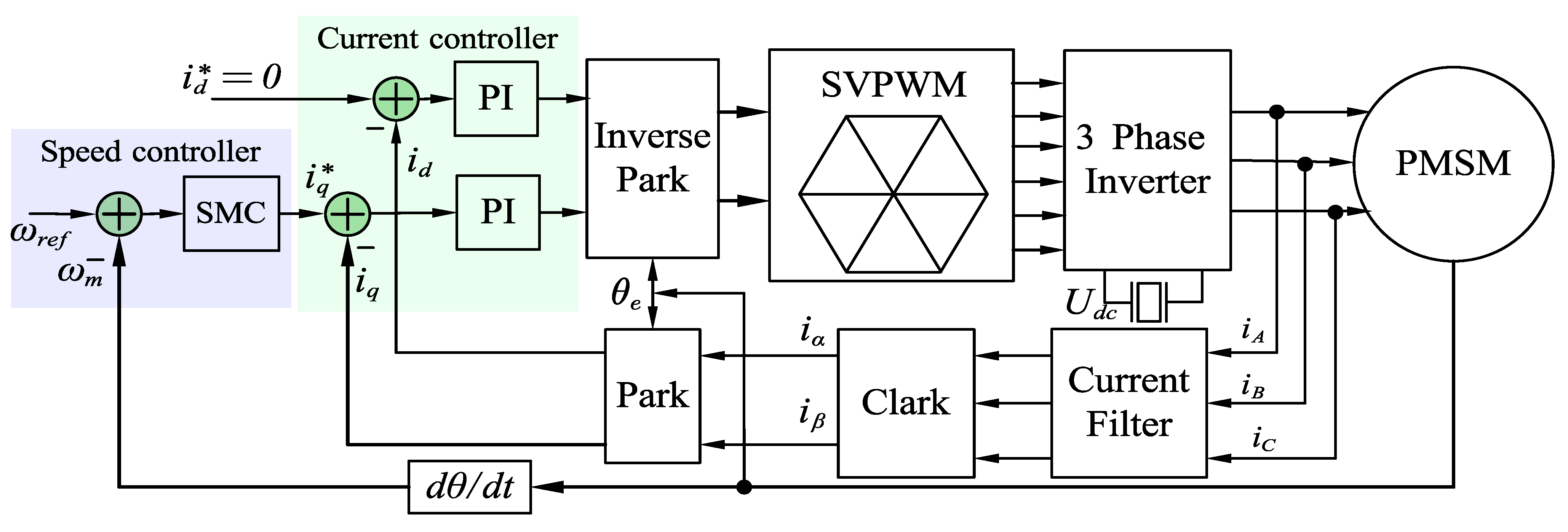

2. Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor

2.1. Structural Configuration of PMSM

2.2. Mathematical Model of PMSM Dynamics

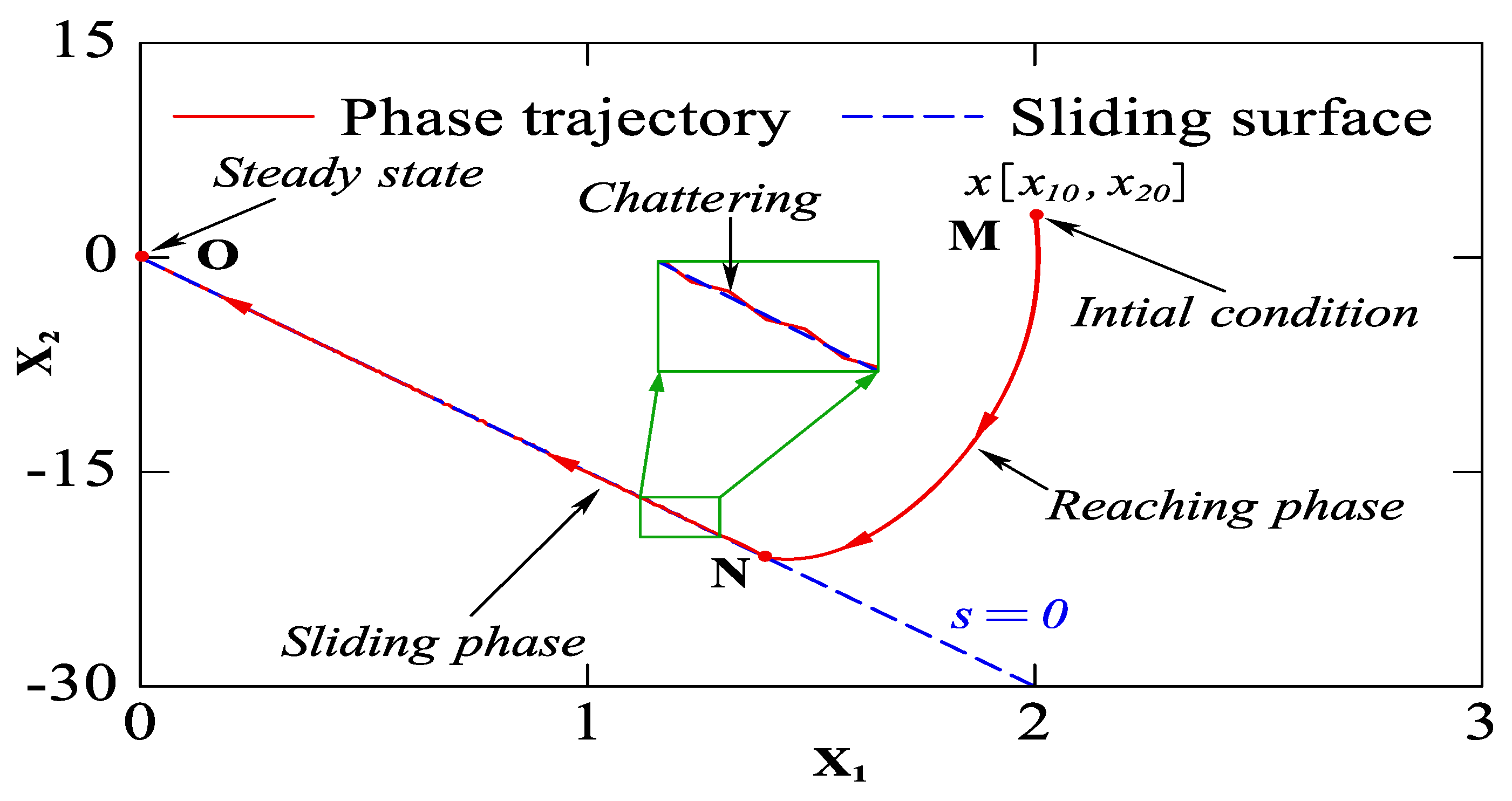

3. Fundamentals of Sliding Mode Control

3.1. Operating Principles of SMC

3.2. Current Research and Development Trends in SMC

4. Sliding Mode Control Design

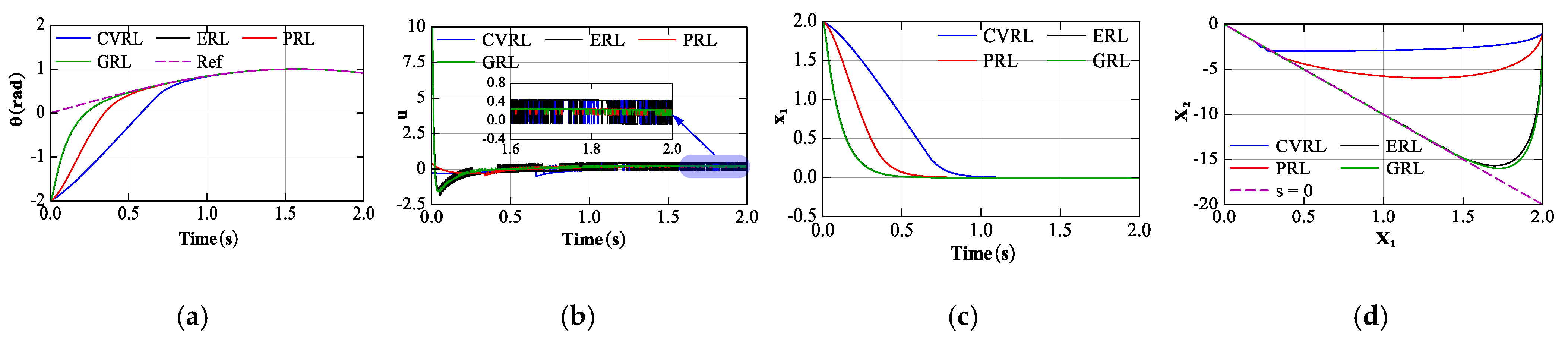

4.1. Reaching Law Approach

- ✓

- Constant Velocity Reaching Law (CVRL):

- ✓

- Exponential Reaching Law (ERL):

- ✓

- Power Reaching Law (PRL):

- ✓

- General Reaching Law (GRL):

4.2. Sliding Surface Design

4.2.1. Linear Sliding Mode Surface

4.2.2. Nonlinear Sliding Mode Surface

4.3. Second-Order SMC

4.3.1. Super-Twisting Algorithm

4.3.2. Twisting Control Algorithm

4.3.3. Prescribed Convergence Law

4.3.4. Sub-Optimal Algorithm

4.4. Arbitrary-Order SMC

4.5. Reduction of Chattering Phenomenon in SMC

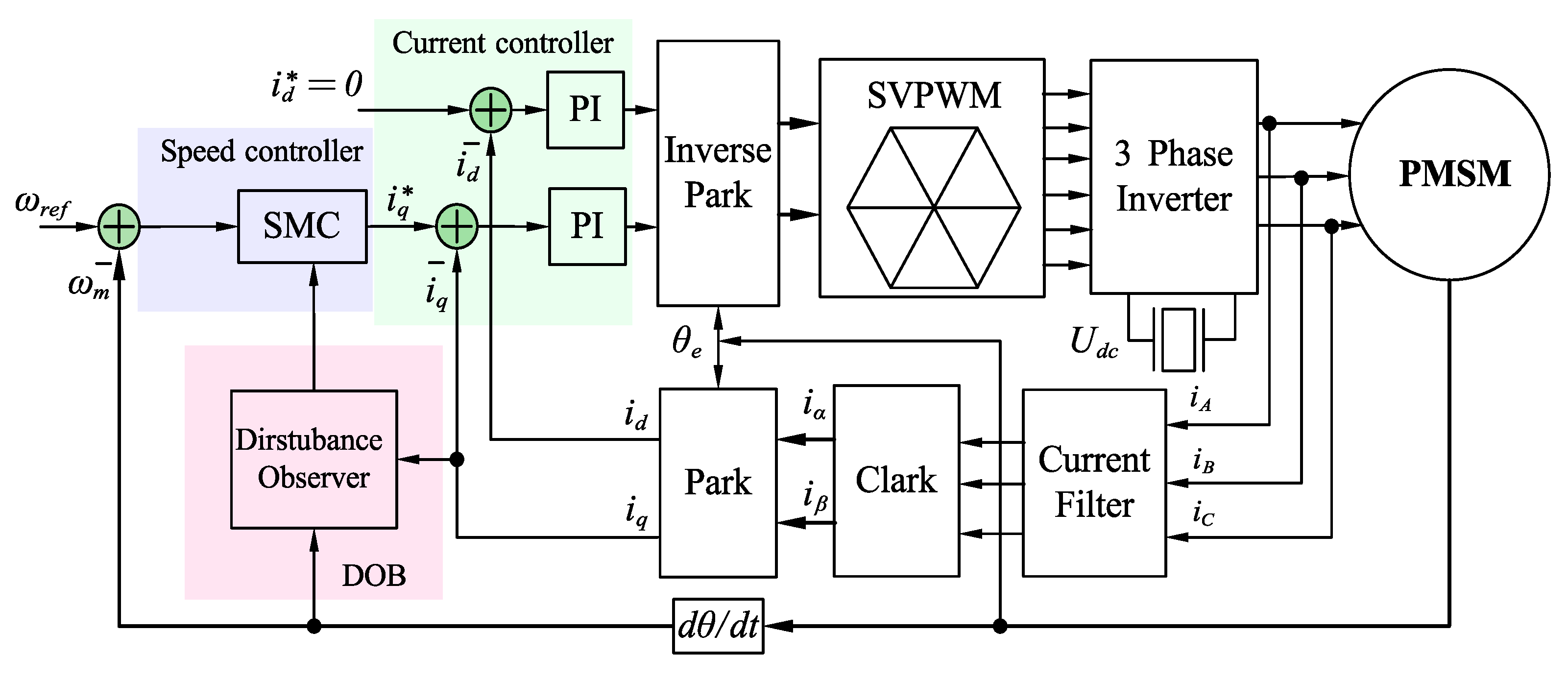

5. Observer-Integrated SMC

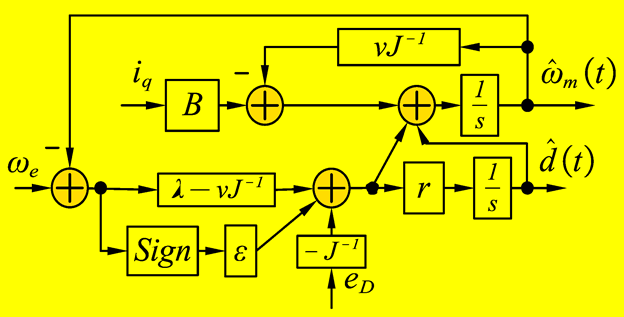

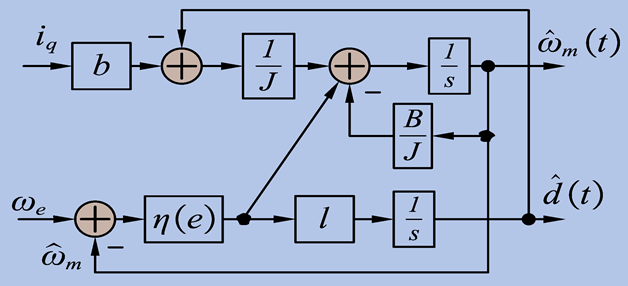

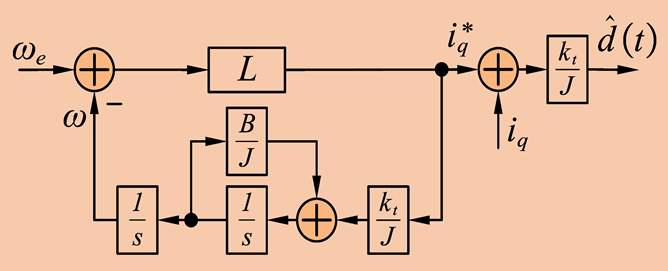

5.1. The Disturbance Observer

5.2. The Sliding Mode Observer

5.3. Linear Parameter Varying—Observer SMC

6. Intelligent SMC

6.1. Fuzzy Logic

6.2. Neural Networks

6.3. Reinforcement Learning

6.4. Metaheuristic Algorithms

7. Discussions and Future Research Trends

7.1. Integration and Hybridization of SMC with Advanced Control Methods and Intelligent Algorithms

7.2. Advanced Techniques for Minimizing Chattering in SMC

7.3. Model-Free and Data-Driven SMC

7.4. Enhancing SMC Reliability Through Fault-Tolerant Design

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fakhar Manesh, M.; Pellegrini, M.M.; Marzi, G.; Dabic, M. Knowledge Management in the Fourth Industrial Revolution: Mapping the Literature and Scoping Future Avenues. IEEE Trans. Eng. Manag. 2021, 68, 289–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.O.N.H.; Nguyen, T.Y.T.; Jeon, J.A.E.W.; Member, S. Improving Speed Regulation of a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Using Modified Model Predictive Control with an Adaptive Second-Order Disturbance Observer. IEEE Open J. Ind. Electron. Soc. 2025, 6, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Yang, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Fan, M.; Wang, Y.; Wen, H.; Lim, C.S.; Yang, H.; Rodriguez, J. Sensorless FCS-MPCC PMSM Drives with Improved Sliding Mode Observer and Low-Complexity Discrete Vector Selection—An Assessment Assessment. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 40, 208–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Zhang, L.; Xu, D.; Chen, Q.; Li, J. Development of Deep Learning-Based Cooperative Fault Diagnosis Method for Multi-PMSM Drive System in 4WID-EVs. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2024, 73, 3506513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dursun, C.; Ozcira Ozkilic, S. A Novel Filtering Observer: A Cost-Effective Estimation Solution for Industrial PMSM Drives Using in-Motion Control Systems. Energies 2025, 18, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Zhang, W.; Xu, W. Integration Design of MR Fluid Brake-Based External Rotor PMSM for Robotic Arm Applications. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2025, 61, 8202705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, D.T.; Nguyen, M.D.; Kim, S.M.; Bang, T.K.; Kim, Y.J.; Shin, K.H.; Choi, J.Y. Irreversible Demagnetization Prediction Due to Overload and High-Temperature Conditions in PMSM Based on Nonlinear Analytical Model. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 40, 2256–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, H.; Deng, Y.; Zuo, Y.; Liu, X.; Wang, J.; Lee, C.H.T. A Variable Structure ADRC for Enhanced Disturbance Rejection and Improved Noise Suppression of PMSM Speed System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 72, 4481–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, C. Model Predictive Voltage Control for PMSM System with Low Parameter Sensitivity. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 13601–13613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, W.; Zhao, X.; Tyrrell, A.; Perinpanayagam, S.; Niu, S.; Wen, G. Application of Artificial Intelligence-Based Technique in Electric Motors: A Review. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 13543–13568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Lin, X.; Wu, T.; Luo, T.; Wang, W.; Liu, T.; Zhang, D. An Extended Model Predictive Control for PMSM with Minimum Ripples and Small Runtimes. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 9367–9376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Young, H.; Fang, S.; Ke, D.; Xie, H.; Wang, F.; Rodriguez, J. Low Prediction Error Model-Free Predictive Control on PMSM Drives with Ordinary Kriging Time-Shift. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 7367–7378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Rodriguez, J. Variable-Vector-Based Model Predictive Control with Reduced Current Harmonic and Controllable Switching Frequency for PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 16429–16441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Sun, Z.; Sun, H.; Wang, W.; Mei, X. A Novel Control Method for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Linear Motor Based on Model Predictive Control and Extended State Observer. Actuators 2024, 13, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, P.; Shen, J.X.; Jiang, C.; Huang, X.; Long, T. Adaptive Periodic Disturbance Observer Based on Fuzzy Logic Compensation for Speed Fluctuation Suppression of PMSM Under Periodic Loads. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 5751–5762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Chen, X.; Liu, J.; Yu, J. Discrete-Time Adaptive Fuzzy Event-Triggered Control for PMSMs with Voltage Faults via Command Filter Approximator. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 7343–7350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelwanis, M.I.; Hegab, A.; Albatati, F. Adaptive Speed Tuning of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors Using Intelligent Fuzzy Based Controllers for Pumping Applications. Processes 2025, 13, 1393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, W.; Guo, S.; Fan, Z.; Li, J. Improved Adaptive PI-like Fuzzy Control Strategy of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Energies 2025, 18, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Peng, J.; Pan, J. A Novel Friction Compensation Method Based on Stribeck Model with Fuzzy Filter for PMSM Servo Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 12124–12133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Wang, S. An Improved Model-Free Adaptive Current Control for PMSM Based on Prior-Optimization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 72, 5591–5601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Dan, H.; Li, X.; Zhou, F.; Su, M. SPMSM Adaptive Control with Guaranteed Dynamic Response under Parameter Mismatch. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 16471–16481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Yu, X.; Zhang, G. Adaptive Model Predictive Current Control for PMSM Drives Based on Bayesian Inference. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 8490–8502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Ye, H.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Y.; Liang, L. Optimal Output-Feedback Controller Design Using Adaptive Dynamic Programming: A Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Application. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2024, 72, 208–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Li, L.; Zhong, C.; Wang, J.; Bai, X.; Liu, J. Adaptive Hybrid Active Disturbance Rejection Speed Control for Vehicle PMSM Electric Propulsion System Under Uncertain Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Liu, C.; Che, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Q. Research on the Coordinated Control of Mining Multi-PMSM Systems Based on an Improved Active Disturbance Rejection Controller. Electronics 2025, 14, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Gan, C.; Wang, H.; Wang, S.; Qu, R.; Liu, X. Active Disturbance Rejection Speed Control with Double-Stage-ESO Considering Aperiodic and Periodic Disturbances for PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, J.; Tong, C.; Zheng, Y.; Bai, J.; Zheng, P. Decoupled Active Disturbance Rejection Control for PMSM Drives to Retain Deadbeat Properties Using Composite Disturbance Observer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 15445–15456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Ling, Z.; Li, T.; Liu, H.; Zhou, F.; Ouyang, X. High-Precision Third Harmonic Fault-Tolerant Control for F-PMSM Based on Adaptive Control Set. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 12242–12256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Yu, H.; Zhang, J.; Yang, Q.; Fu, C. Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Cooperative Optimization Control for PMSM Servo System with Input Saturation and Multisource Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 40, 6506–6518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T.; Wang, Z.; Mao, Y. Online Current Optimization-Based Fault-Tolerant Control of Standard PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 15521–15531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Jiang, H.; Shi, P.; Zhou, Y.; Xiao, D.; Wang, Z. Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control Based Fault Diagnosis of Dual Three-Phase PMSM Drives. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 2556–2564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Xu, Q.; Wang, Y. A New Sliding-Mode Observer-Based Deadbeat Predictive Current Control Method for Permanent Magnet Motor Drive. Machines 2024, 12, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Sun, X.; Guo, D.; Yao, M.; Diao, K. Advanced Torque Sharing Function Strategy with Sliding Mode Control for Switched Reluctance Motors. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 2302–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuyen, T.T.; Yang, J.; Liao, L.; Zhou, J. Integrated Sliding Mode Control for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives Based on Second-Order Disturbance Observer and Low-Pass Filter. Electronics 2025, 14, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Pan, T.; Ding, S. Finite-Time Fast Integral Terminal Sliding Mode Speed Control Method with Disturbance Observer for SPMSM. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 10694–10704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N.; Jeon, J.W. Robust Speed Controller Using Dual Adaptive Sliding Mode Control (DA-SMC) Method for PMSM Drives. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 63261–63270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, A.T.; Van Huynh, V.; Shim, J.W.; Lim, C.P. Optimized Sliding Mode Frequency Controller for Power Systems Integrated Energy Storage System with Droop Control. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 43749–43766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, J.Y.; Gao, W.; Hung, J.C. Variable Structure Control: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 1993, 40, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallaha, C.J.; Saad, M.; Kanaan, H.Y.; Al-Haddad, K. Sliding-Mode Robot Control with Exponential Reaching Law. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidi, K.; Xu, J.; Yu, X. On the Discrete-Time Integral Sliding-Mode Control. IEEE Trans. Automat. Control 2007, 52, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta, H.; Loukianov, A.G.; Canedo, J.M. Passivity Sliding Mode Control of Large-Scale Power Systems. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2019, 27, 1219–1227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orlov, Y.; Utkin, V.I. Unit Sliding Mode Control in Infinite-Dimensional Systems. Appl. Math. Comput. Sci. 1998, 8, 7–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, D.W.C.; Niu, Y. Robust Fuzzy Design for Nonlinear Uncertain Stochastic Systems via Sliding-Mode Control. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2007, 15, 350–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.; Spurgeon, S.K. Sliding Mode Control: Theory and Applications; CRC Press: New York, NY, USA, 1998; Volume 11, ISBN 9780429075933. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Wang, Y.; Wang, T.; Hu, Z.; Yang, X.; Rodriguez-Andina, J.J. Time-Delay Sliding Mode Control for Trajectory Tracking of Robot Manipulators. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 13083–13091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhang, H.; Wang, M.; Zeng, L. Robust Adaptive Fixed-Time Sliding-Mode Control for Uncertain Robotic Systems with Input Saturation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2023, 53, 2636–2646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Liu, G.; Diao, S.; Yang, T.; Fang, Y.; Sun, N. Admittance-Based Output Feedback Fuzzy Switching Control for PAM-Driven Parallel Robots via Nonsingular Terminal Sliding Mode. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 14247–14259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Zheng, T.; He, Y. Fractional-Order Sliding Mode Controller Based on ESO for a Buck Converter with Mismatched Disturbances: Design and Experiments. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 8451–8462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Li, X.; Dong, Y. Improved DC-Link Voltage Sliding Mode Control for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator Systems with Three-Phase AC-DC Converters. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 2285–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseinabadi, P.A.; Mekhilef, S.; Pota, H.; Kermadi, M. Finite-Time Robust Controller Using Sliding Mode Approach for Grid-Connected Inverters. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Energy Technologies for Future Grids (ETFG 2023), Wollongong, Australia, 3–6 December 2023; Volume 61, pp. 4027–4039. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Fei, J. Adaptive Sliding Mode Control with Chebyshev Neural Disturbance Observer for Active Power Filter. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 16355–16372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Liu, Y.; Gao, H. Reliability-Constrained Uncertain Spacecraft Sliding Mode Attitude Tracking Control with Interval Parameters. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 61, 6589–6600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javaid, U.; Dong, H.; Ijaz, S.; Alkarkhi, T.; Haque, M. High-Performance Adaptive Attitude Control of Spacecraft with Sliding Mode Disturbance Observer. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 41990–41999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A.B.; Shehu, M.A.; Gali, V.; Do, T.D. Disturbance Observer-Based Super-Twisting SMC for Variable Speed Wind Energy Conversion System under Parametric Uncertainties. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 11003–11020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhassan, A.B.; Do, T.D. The Influence of Higher-Order Disturbance Estimation on Wind Power Generation of WECS Using SMC with Sensorless Wind Speed Estimation. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 62179–62197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, C.; Yin, T.; Qiao, W.; Zhu, Y. Disturbance Rejection Control for PMSGs Based on Novel Sliding Mode Control Law and Unknown System Disturbance Estimator. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Fang, S.; Song, Z.; Xu, Q.; Wang, J.; Meng, Y. Low-Pass Sliding Mode Control for Arc Motor Based on Adaptive Reaching Law. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Jiao, R.; Li, B.; Zhang, X.; Yan, H. Finite-Time Consensus of Second-Order Multiagent Systems with Input Saturation via Hybrid Sliding-Mode Control. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 14623–14632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiliveri, V.R.; Kalpana, R.; Kishan, D. Sliding Mode Predictive Control for Enhanced Lateral Motion Stability in Independent Drive Electric Vehicle with Input Delay and Disturbance Compensation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 139821–139836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Ding, D.; Shen, B.; Ge, X. Integral Sliding Mode Control for Automated Vehicles under Coding-Decoding Mechanisms with Constrained Bit Rate. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 16214–16226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, X.; Wei, L.; Zhuang, P. Barrier Function-Based Neural Network Adaptive Integral Sliding Mode Control for Multi-Axle Steering Vehicles Lateral Dynamics Control. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 9903–9914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.J.; Chen, S.Y.; Hsu, I.M.; Xu, C.X. Robust Deadbeat Predict Current Control Using Intelligent Integral Sliding Mode Control for Interior Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drive. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 8282–8293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh Trieu, N.; Tan No, N.; Nguyen Vu, T.; Thinh, N.T. Chattering-Free PID-Nested Nonsingular Terminal Sliding Mode Controller Design for Electrical Servo Drives. Mathematics 2025, 13, 1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarkhani, R.; Krim, S.; Mansouri, M.; Mimouni, M.F. Robust Current Sensor Fault-Tolerant Controller Using Third Order Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Observer and Controller for Induction Motors. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 52841–52862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wogi, L.; Morawiec, M.; Ayana, T. Sensorless Control of Induction Motor Based on Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Observer with Speed Convergence Improvement. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 74239–74250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junejo, A.K.; Xu, W.; Tang, Y.; Liao, K.; Xiao, H.; Li, Y. Enhanced Cascade Sliding Mode Direct Thrust Control for Linear Induction Machine Based on Linear Metro. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 11517–11531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Wang, N.; Yao, M.; Lei, G. Position Sensorless Control of SRMs Based on Improved Sliding Mode Speed Controller and Position Observer. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 72, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddique, F.; Singh, B. HOSMO and Reference Model Based Control for SRM Drive. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 6222–6231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, K.; Yang, M.; Li, X.; Shi, P.; Wang, P. Research on a New Adaptive Integral Sliding Mode Controller Based on a Small BLDC. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 73204–73213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, H.; Kiyoumarsi, A.; Madani, S.M.; Ataei, M. Torque Ripple Reduction of Nonsinusoidal Brushless DC Motor Based on Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Direct Power Control. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 3769–3779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yu, S.; Lu, E.; Wei, Q.; Yang, Z. Study on Cross-Coupling Synchronous Control Strategy of Dual-Motor Based on Improved Active Disturbance Rejection Control–Nonsingular Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Control Strategy. Electronics 2025, 14, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Wang, X.; Ji, W.; Ding, S.; Liu, T. A Composite Sliding Mode Control with the Modified Variable Exponential Reaching Law and Super-Twisting Extended State Observer for PMSM. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 21284–21294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Member, S.; Wang, L. Finite-Time Control of Permanent Magnet Linear Synchronous Motor via Variable Gain Fractional-Order Terminal Sliding Mode Control. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 9105–9120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Jiang, W.; Zhou, L.; Sun, J.; Song, X. Improved Model-Free Sliding Mode Control of Linear Motor Based on Time-Varying Gain Model-Assisted Linear Extended State Observer. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 20726–20733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouabhi, R.; Herizi, A.; Djerioui, A. Performance of Robust Type-2 Fuzzy Sliding Mode Control Compared to Various Conventional Controls of Doubly-Fed Induction Generator for Wind Power Conversion Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 3778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, F.J.; Chen, S.G.; Huang, M.S.; Liang, C.H.; Liao, C.H. Adaptive Complementary Sliding Mode Control for Synchronous Reluctance Motor with Direct-Axis Current Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lixian, S.; Rahiman, W. A Compound Control for Hybrid Stepper Motor Based on PI and Sliding Mode Control. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 163536–163550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Hu, W.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, C.; Sun, X. A Gain Adaptive High-Order Terminal Sliding Mode Observer under SPMSM Sensorless Control. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 6555–6565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Xu, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chai, X. Error Analysis and Design of Sliding-Mode-Observer-Based Sensorless PMSM Drives under a Low Sampling Ratio. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 7783–7792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Lai, C.; Iyer, K.L.V. A Review of Sliding Mode Observer Based Sensorless Control Methods for PMSM Drive. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2023, 38, 11352–11367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Ye, Y.; Chen, X.; Yuan, Y. Adaptive High-Order Sliding Mode Low-Speed Control with RBF Neural Network Nonlinear Disturbance Observer for PMSM Drive System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 10865–10876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C.; Shtessel, Y.B. Adaptive Continuous Higher Order Sliding Mode Control. Automatica 2016, 65, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D.; Qian, L.F.; Zou, Q.; Liang, D. Adaptive High-Order Sliding Mode Control for PMSM Drives with Load Disturbance. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 5th Information Technology and Mechatronics Engineering Conference (ITOEC 2020), Chongqing, China, 12–14 June 2020; pp. 240–248. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Wang, B.; Yu, Y.; Xu, D. High-Order Sliding-Mode Observer with Adaptive Gain for Sensorless Induction Motor Drives in the Wide-Speed Range. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 11055–11066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gieras, J.F.; Shen, J.X. Modern Permanent Magnet Electric Machines; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; ISBN 9780367610586. [Google Scholar]

- Pyrhonen, J.; Jokinen, T.; Hrabovcova, V. Design of Rotating Electrical Machines; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2014; Volume 614, ISBN 9781118581575. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Zhou, J.; Yang, J.; Xu, C.; Gao, S.; Lu, L. Linear Regression-Based Dead-Time Identification Strategy for PMSM Using Static Voltage Injection. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Mechatronics Technology and Intelligent Manufacturing (ICMTIM 2024), Nanjing, China, 26–28 April 2024; pp. 291–296. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Yang, K.; Chen, K. An Improved Position-Sensorless Control Method at Low Speed for PMSM Based on High-Frequency Signal Injection into a Rotating Reference Frame. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 86510–86521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shtessel, Y.; Edwards, C.; Fridman, L.; Levant, A. Sliding Mode Control and Observation; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 9780817648930. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, S.C.; Lai, Y.M.; Tse, C.K. Sliding Mode Control of Switching Power Converters: Techniques and Implementation; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2018; Volume 301, ISBN 9781315217796. [Google Scholar]

- Utkin, V.; Guldner, J.; Shi, J. Sliding Mode Control in Electro-Mechanical Systems; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2009; ISBN 9781420065602. [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo, H.; Orosco, R.; Huerta, H.; Vazquez, N.; Estrada, L.; Pinto, S.; De Castro, A. A Finite-Set Integral Sliding Modes Predictive Control for a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drive System. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shevitz, D.; Paden, B. Lyapunov Stability Theory of Nonsmooth Systems. IEEE Trans. Automat. Control 1994, 39, 1910–1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ortiz, D.; Chairez, I.; Poznyak, A. Sliding-Mode Control of Full-State Constraint Nonlinear Systems: A Barrier Lyapunov Function Approach. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2022, 52, 6593–6606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Wang, F.; Ke, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, W. Robust Continuous Model Predictive Speed and Current Control for PMSM with Adaptive Integral Sliding-Mode Approach. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 14398–14408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Liu, J.; Vazquez, S.; Mazumder, S.K. Sliding Mode Control in Power Converters and Drives: A Review. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2022, 9, 392–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, B.; Lu, W.; Yan, B.; Lu, K.; Feng, J.; Guo, L. A Novel Position Speed Integrated Sliding Mode Variable Structure Controller for Position Control of PMSM. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 12621–12631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Ding, J.; Sun, X.; Lei, G.; Dianov, A.; Demidova, G.; Prakht, V. Compensation Control of PMSMs Based on a High-Order Sliding Mode Observer with Inertia Identification. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 5084–5096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeli, D.; Sontag, E.D.; Wang, Y. A Characterization of Integral Input-to-State Stability. IEEE Trans. Automat. Control 2000, 45, 1082–1097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sontag, E.D.; Wang, Y. New Characterizations of Input-to-State Stability. IEEE Trans. Automat. Control 1996, 41, 1283–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Niu, Y.; Song, J. Input-to-State Stabilization of Interval Type-2 Fuzzy Systems Subject to Cyberattacks: An Observer-Based Adaptive Sliding Mode Approach. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2020, 28, 190–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, M.; Kamal, S.; Bandyopadhyay, B.; Vachhani, L. Continuous Higher Order Sliding Mode Control for a Class of Uncertain MIMO Nonlinear Systems: An ISS Approach. Eur. J. Control 2018, 41, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Deng, M.; Xu, S.; Huang, D. Speed Regulation for PMSM Drives Based on a Novel Sliding Mode Controller. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 63577–63584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Ahn, H.; Park, J.; You, K. A Modified Exponential Reaching Law for Sliding Mode Control and Its Applications. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2024, 34, 9783–9796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, T.T.; Nguyen, V.Q.; Le, K.M.; Tran, H.N.; Jeon, J.W. An Adaptive Sliding-Mode Controller with a Modified Reduced-Order Proportional Integral Observer for Speed Regulation of a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 7181–7191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Huang, S.; Lu, K.; Peng, Y.; Wang, H.; Yang, J. A Fast Sliding Mode Speed Controller for PMSM Based on New Compound Reaching Law with Improved Sliding Mode Observer. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 2955–2968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Dou, M.; Yan, S.; Dang, M.; Hua, Z.; Zhao, D. A Sliding Mode Prediction Error Compensation of Incremental Model Based Deadbeat Predictive Current Control for SPMSM Drives with a Sliding Mode Speed Controller. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2025, 11, 9724–9739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Dou, M.; Yan, S.; Dang, M.; Hua, Z. Deadbeat Predictive Current Control Using Super-Twisting Observer for SPMSM Drives with Anti-Disturbance Sliding Mode Speed Controller. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2021, 40, 1826–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dang, C.; Dou, M.; Yan, S.; Dang, M.; Zhao, D. An Improved Model-Free Predictive Current Control for SPMSM Drives Based on Adaptive Extended State Observer with Robust Sliding Mode Speed Controller. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 12378–12392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derbel, N.; Ghommam, J.; Zhu, Q. Applications of Sliding Mode Control; Springer: Singapore, 2017; ISBN 9789811023736. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J. Sliding Mode Control Using MATLAB; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; ISBN 9780128025758. [Google Scholar]

- Li, S.; Zhou, M.; Yu, X. Design and Implementation of Terminal Sliding Mode Control Method for PMSM Speed Regulation System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2013, 9, 1879–1891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, X.; Liang, J. A New Reaching Law for Antidisturbance Sliding-Mode Control of PMSM Speed Regulation System. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2020, 35, 4117–4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, P.; Jia, B. A Saturation Adaptive Nonlinear Integral Sliding Mode Controller for Ship Permanent Magnet Propulsion Motors. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkataraman, S.T.; Gulati, S. Control of Nonlinear Systems Using Terminal Sliding Modes. J. Dyn. Syst. Meas. Control. Trans. ASME 1993, 115, 554–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Zhihong, M. Fast Terminal Sliding-Mode Control Design for Nonlinear Dynamical Systems. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Fundam. Theory Appl. 2002, 49, 261–264. [Google Scholar]

- Musarrat, M.N.; Fekih, A.; Islam, M.R. NFTSMC-Based Approach for Mitigating SSR in a DFIG-Based WECS. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2024, 34, 5207806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Zhang, W. A New Fast Observer-Based Speed Control Algorithm for PMSM Motor Drive Based on Sliding Mode Theory. Int. J. Dyn. Control 2024, 12, 4274–4283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Jiang, Y.; Xiong, L.; Wang, P. Sliding Mode Control Approach with Integrated Disturbance Observer for PMSM Speed System. CES Trans. Electr. Mach. Syst. 2023, 7, 118–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Junejo, A.K.; Liu, Y.; Hussien, M.G.; Zhu, J. An Efficient Antidisturbance Sliding-Mode Speed Control Method for PMSM Drive Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2021, 36, 6879–6891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X.; Yu, J.; Yu, H. Time-Varying Disturbance Observer Based Improved Sliding Mode Single-Loop Control of PMSM Drives with a Hybrid Reaching Law. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2023, 38, 2539–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, D.; Cai, H.; Zeng, W. Fast Terminal Sliding-Mode Predictive Speed Controller for Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motor Drive Systems. Energies 2024, 17, 3767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, A. Sliding Order and Sliding Accuracy in Sliding Mode Control. Int. J. Control 1993, 58, 1247–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belkhier, Y.; Shaw, R.N.; Bures, M.; Islam, M.R.; Bajaj, M.; Albalawi, F.; Alqurashi, A.; Ghoneim, S.S.M. Robust Interconnection and Damping Assignment Energy-Based Control for a Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Using High Order Sliding Mode Approach and Nonlinear Observer. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 1731–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Dai, L.; Min, H.; Yang, J.; Li, S. Prescribed-Time Nonsingular Terminal Sliding Mode Control and Its Application in PMSM Servo Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 72, 3072–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J. A Novel High Order Sliding Mode Control Method. ISA Trans. 2021, 111, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djouadi, H.; Ouari, K.; Belkhier, Y.; Lehouche, H. Real-Time HIL Simulation of Nonlinear Generalized Model Predictive-Based High-Order SMC for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Machine Drive. Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst. 2024, 2024, 5536555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, S. An Improved Super-Twisting High-Order Sliding Mode Observer for Sensorless Control of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. Energies 2021, 14, 6047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.Y.; Chen, X.X.; Liu, Y.X.; Yan, S.; Zhang, Y.P.; Wang, H.Y. Research on Current Harmonic Suppression Strategy of HSPMSM Based on Super Twisting Sliding Mode Control. Electr. Eng. 2024, 107, 2273–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.; Zhan, Z.; Xia, J.; Ding, S.; Yu, X. Second-Order Sliding Mode Control for Nonminimum Phase Boost Converters with Mismatched Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 11, 5555–5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales-Zurita, O.; Andino, O.L.; Clairand, J.M.; Escriva-Escriva, G. PSO Tuning of a Second-Order Sliding-Mode Controller for Adjusting Active Standard Power Levels for Smart Inverter Applications. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2023, 14, 4182–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohapatra, B.; Sahu, B.K.; Pati, S.; Bajaj, M.; Blazek, V.; Prokop, L.; Misak, S. Optimizing Grid-Connected PV Systems with Novel Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Controllers for Real-Time Power Management. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inomoto, R.; Filho, A.J.S.; Monteiro, J.R.; da Costa, E.C.M. Genetic Algorithm Based Tuning of Sliding Mode Controllers for a Boost Converter of PV System Using Internet of Things Environment. Results Control Optim. 2024, 14, 100389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, A.; Deb, S.; Kar, N.; Sarkar, J.L.; Mondal, A. Event-Triggered Sliding Mode Controller for Cognitive Internet of Things. IEEE Trans. Netw. Serv. Manag. 2024, 22, 1046–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karami-Mollaee, A.; Barambones, O. Higher Order Sliding Mode Control of MIMO Induction Motors: A New Adaptive Approach. Mathematics 2023, 11, 4558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.G. Performance Enhancement of Permanent Magnet DC Motor with SEPIC Converter through Higher-Order Sliding Surface. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2024, 22, 789–797. [Google Scholar]

- Long, Y.; Song, E.; Yao, C. Second-Order Discrete-Time Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Control Based on Exponential Reaching Law for Electronic Throttle. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 13770–13782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Wang, H.; Lee, C.H.T.; Ding, S. Composite Adaptive Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Control Using Barrier Function for PM Motor Drives Toward Electric Aircraft Applications. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 16255–16264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Hao, Y.; Guo, T.; Lv, B.; Wang, Q. Second-Order Sliding Mode Control of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Based on Singular Perturbation. Energies 2022, 15, 8028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makhad, M.; Zazi, K.; Zazi, M.; Loulijat, A. Adaptive Super-Twisting Terminal Sliding Mode Control and LVRT Capability for Switched Reluctance Generator Based Wind Energy Conversion System. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2022, 141, 108142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, K.; Li, Q.; Chen, W.; Chen, C.C.; Ding, S. Modified Discrete-Time Super-Twisting Control of PMSM Speed Regulation System: Theory and Experimentation. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 7980–7993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrara, A.; Rubagotti, M. A Sub-Optimal Second Order Sliding Mode Controller for Systems with Saturating Actuators. IEEE Trans. Automat. Control 2009, 54, 1082–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perruquetti, W.; Barbot, J.P. Sliding Mode Control in Engineering; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Volume 39, ISBN 0824706714. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, S.; Mei, K.; Li, S. A New Second-Order Sliding Mode and Its Application to Nonlinear Constrained Systems. IEEE Trans. Automat. Contr. 2019, 64, 2545–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merabet, A. Cascade Second Order Sliding Mode Control for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drive. Electronics 2019, 8, 1508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Mei, K. A State-Constrained Second-Order Sliding Mode Control for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. Nonlinear Dyn. 2024, 112, 12269–12282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levant, A. Universal Single-Input–Single-Output (SISO) Sliding-Mode Controllers with Finite-Time Convergence. Trans. Autom. Control 2001, 46, 1447–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plestan, F.; Glumineau, A.; Laghrouche, S. A New Algorithm for High-Order Sliding Mode Control. Int. J. Robust Nonlinear Control 2008, 18, 441–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamal, S.; Bandyopadhyay, B. Arbitrary Higher Order Sliding Mode Control Based on Control Lyapunov Approach. In Proceedings of the 2012 12th International Workshop on Variable Structure Systems, Mumbai, India, 12–14 January 2012; pp. 446–451. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X. Advanced Sliding Mode Control for Mechanical Systems: Design, Analysis and MATLAB Simulation; Springer Nature: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2011; ISBN 9787302248279. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Mei, X.; Tao, T.; Xu, M. The Sliding-Mode Control Based on a Novel Reaching Technique for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors. Electr. Power Components Syst. 2019, 47, 1505–1513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghababa, M.P.; Akbari, M.E. A Chattering-Free Robust Adaptive Sliding Mode Controller for Synchronization of Two Different Chaotic Systems with Unknown Uncertainties and External Disturbances. Appl. Math. Comput. 2012, 218, 5757–5768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, D.; Yi, J. Hierarchical Sliding Mode Control for Under-Actuated Cranes: Design, Analysis and Simulation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; ISBN 9783662484173. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.; Xie, Z.; Wang, X.; Lei, Z.; Shangguan, C. Sliding Mode Disturbance Compensated Speed Control for PMSM Based on an Advanced Reaching Law. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2024, 53, 1541–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, H.; Zhang, M.; Chen, B.; Jia, R.; Mao, J. Non-Singular Fast Terminal Sliding Mode Control of PMSMs with Disturbance Compensation. J. Power Electron. 2024, 25, 1245–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Xiong, Y.; Yang, J.; Tian, X. Torque Ripple Reduction for a 12/8 Switched Reluctance Motor Based on a Novel Sliding Mode Control Strategy. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2023, 9, 359–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Zhu, Y.; Cai, Y.; Yao, M.; Sun, Y.; Lei, G. Optimized-Sector-Based Model Predictive Torque Control with Sliding Mode Controller for Switched Reluctance Motor. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 39, 379–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Cao, J.; Lei, G.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, J. A Composite Sliding Mode Control for SPMSM Drives Based on a New Hybrid Reaching Law with Disturbance Compensation. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2021, 7, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, S.; Hou, Q.; Wang, H. Disturbance-Observer-Based Second-Order Sliding Mode Controller for Speed Control of PMSM Drives. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2023, 38, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Liu, X. An Improved Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Single-Loop Control with Current-Constraint for PMSM Based on Two-Time Scale Disturbance Observer. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2024, 10, 5389–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, M.; Ahn, H.; Chung, Y.; You, K. Speed Regulation for PMSM with Super-Twisting Sliding-Mode Controller via Disturbance Observer. Mathematics 2023, 11, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, T.; Deng, Y.; Li, H.; Sun, Z.; Cao, H.; Wei, Z. Fast Integral Terminal Sliding Mode Control with a Novel Disturbance Observer Based on Iterative Learning for Speed Control of PMSM. ISA Trans. 2023, 134, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Xu, W.; Jin, N.; Xiao, H. A DC-Offset Removed Sensorless Control Method for PMSM Based on SMO with an Improved Pre-Filter and a Speed Immune Position Error Compensation Strategy. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 40, 5163–5176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahat, A.; Liu, G.; Chen, Q. Back EMF Harmonics and DC Components Rejection for Improvement in Sensorless FTC for Multiphase PMSM Based on SMO with Enhanced Cross-Coupling Second-Order Sequence Filter. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2025, 13, 2612–2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamma, J.S.; Athans, M. Analysis of Gain Scheduled Control for Nonlinear Plants. IEEE Trans. Automat. Control 1990, 35, 898–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sereni, B.; Galvao, R.K.H.; Assuncao, E.; Teixeira, M.C.M. An Output-Feedback Design Approach for Robust Stabilization of Linear Systems with Uncertain Time-Delayed Dynamics in Sensors and Actuators. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 20769–20785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Wu, F.; Su, J. Harmonic State-Space Modeling and Closed-Loop Control of Single-Stage High-Frequency Isolated DC-AC Converter. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 4576–4585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, S.; Guo, X.; Xu, S.; Min, H.; Dai, L. Recursive Higher Order Non-Singular Terminal Sliding Mode Control with Prescribed Convergence Time: Application to PMSM Servo Systems. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 17955–17966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xian, J.; Shen, L.; Chen, J.; Feng, W. Continuous Sliding Mode Control of Robotic Manipulators Based on Time-Varying Disturbance Estimation and Compensation. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 43473–43480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Kaynak, O. Sliding-Mode Control with Soft Computing: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 56, 3275–3285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, P.; Rajan, R.; Shanmugam, L.; Joo, Y.H. Adaptive Fractional Fuzzy Integral Sliding Mode Control for PMSM Model. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2019, 27, 1674–1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B.; Zhu, D.; Tao, T. Model-Free Adaptive Fuzzy Sliding-Mode Observer Control for PMSM. Energies 2025, 18, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; You, S.; Kim, W.; Moon, J. Fuzzy Event-Triggered Super Twisting Sliding Mode Control for Position Tracking of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors under Unknown Disturbances. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2023, 19, 9843–9854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuppusamy, S.; Joo, Y.H. Memory-Based Integral Sliding-Mode Control for T-S Fuzzy Systems with PMSM via Disturbance Observer. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2021, 51, 2457–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Wang, Y.K.; Zheng, W.X.; Niu, Y. Adaptive Terminal Sliding Mode Speed Regulation for PMSM Under Neural-Network-Based Disturbance Estimation: A Dynamic-Event-Triggered Approach. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 8446–8456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sousy, F.F.M.; Alenizi, F.A.F. Optimal Adaptive Super-Twisting Sliding-Mode Control Using Online Actor-Critic Neural Networks for Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 82508–82534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Nicola, C.I.; Selișteanu, D.; Șendrescu, D. Rapid Control Prototyping of Sensorless Control System for PMSM Based on Multi-Agent Reinforcement Learning and Fractional Order Sliding Mode Control. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2025, 66, 102054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Fang, S.; Hu, J.; Huang, D. Multiscenarios Parameter Optimization Method for Active Disturbance Rejection Control of PMSM Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 10957–10968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Nicola, C.I.; Selișteanu, D. Improvement of PMSM Sensorless Control Based on Synergetic and Sliding Mode Controllers Using a Reinforcement Learning Deep Deterministic Policy Gradient Agent. Energies 2022, 15, 2208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahraoui, Y.; Zaihidee, F.M.; Kermadi, M.; Mekhilef, S.; Alhamrouni, I.; Seyedmahmoudian, M.; Stojcevski, A. Optimal Tuning of Fractional Order Sliding Mode Controller for PMSM Speed Using Neural Network with Reinforcement Learning. Energies 2023, 16, 4353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, H.; Wang, H.; Yang, C.; Gui, J.; Fu, R. Sliding Mode Active Disturbance Rejection Control of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Based on Improved Genetic Algorithm. Actuators 2023, 12, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Cao, B.; Nan, N.; Li, M.; Chen, Y.Q. An Adaptive PID-Type Sliding Mode Learning Compensation of Torque Ripple in PMSM Position Servo Systems towards Energy Efficiency. ISA Trans. 2021, 110, 258–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qu, H.; Meng, L.; Huang, C.; Chen, Q.; Wang, Q. A Sliding Mode Control of the Bearingless Permanent Magnet Slice Motor for the Blood Pump Based on the GAPSO. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 18929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Zhang, X.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, P.; Wu, X. A New Fuzzy Sliding Mode Control Method for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Servo System Based on Optimization of Fuzzy Rules. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2022, 17, 1748–1754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Yuan, P.; Han, S.; Wang, G. Anti-Interference Sliding Mode Control of PMSM Based on Improved Salp Swarm Algorithm. IEEJ Trans. Electr. Electron. Eng. 2024, 20, 614–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumitrescu, C.; Ciotirnae, P.; Vizitiu, C. Fuzzy Logic for Intelligent Control System Using Soft Computing Applications. Sensors 2021, 21, 2617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotikunnan, P.; Roongprasert, K.; Chotikunnan, R.; Pititheeraphab, Y.; Puttasakul, T.; Wongkamhang, A.; Thongpance, N. Hybrid Fuzzy-Expert System Control for Robotic Manipulator Applications. J. Robot. Control 2025, 6, 155–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amador-Angulo, L.; Castillo, O.; Melin, P.; Castro, J.R. Interval Type-3 Fuzzy Adaptation of the Bee Colony Optimization Algorithm for Optimal Fuzzy Control of an Autonomous Mobile Robot. Micromachines 2022, 13, 1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madebo, N.W. Enhancing Intelligent Control Strategies for UAVs: A Comparative Analysis of Fuzzy Logic, Fuzzy PID, and GA-Optimized Fuzzy PID Controllers. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 16548–16563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzoundja Fapi, C.B.; Tchakounté, H.; Ndje, M.; Wira, P.; Abdeslam, D.O.; Louzazni, M.; Kamta, M. Fuzzy Logic-Based Maximum Power Point Tracking Control for Photovoltaic Systems: A Review and Experimental Applications. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2025, 32, 2405–2428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakmak, R.; Bayrak, G.; Koc, M. A Fuzzy Logic-Based Energy Management Approach for Fuel Cell and Photovoltaic Powered Electric Vehicle Charging Station in DC Microgrid Operations. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 49905–49921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Dewantoro, G.; Xiao, T.; Swain, A. A Comparative Analysis of Fuzzy Logic Control and Model Predictive Control in Photovoltaic Maximum Power Point Tracking. Electronics 2025, 14, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, R.; Li, Q.; Wang, K.; Li, M.; Zhu, X. Reliability-Driven Fuzzy Rule Inference for Critical Safe Driving in Vehicle Tracking Control. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 7073–7085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, P.; Liu, P.; Qu, P. High-Performance Speed Control of PMSM Using Fuzzy Sliding Mode with Load Torque Observer. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 7053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoszewicz, A. Sliding Mode Control; BoD–Books on Demand: Rijeka, Croatia, 2011; ISBN 9789533071626. [Google Scholar]

- Methodologies, E. Adaptive Sliding Mode Neural Network Control for Nonlinear Systems; Academic Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019; ISBN 9780128153727. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Yuan, Y.; Sun, W. Finite-Time Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Control for Robot Manipulators with Guaranteed Transient Performance. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 3336–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Li, H.; Chen, Z.; Han, Q.L. A Fault Diagnosis Method for Quadruped Robot Based on Hybrid Deep Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2025, 21, 3027–3036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y. Robot Trajectory Tracking Control Based on Neural Networks and Sliding Mode Control. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 96740–96757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Sun, L.; Kawaguchi, T.; Hashimoto, S. Fault Diagnosis of Wire Disconnection in Heater Control System Using One-Dimensional Convolutional Neural Network. Processes 2025, 13, 402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hng Lim, W.; Sfarra, S.; Hsiao, T.Y.; Yao, Y. Physics-Informed Neural Networks for Defect Detection and Thermal Diffusivity Evaluation in Carbon Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Using Pulsed Thermography. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 4500910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabhu, N.; Thirumalaivasan, R.; Ashok, B. Design of Sliding Mode Controller with Improved Reaching Law through Self-Learning Strategy to Mitigate the Torque Ripple in BLDC Motor for Electric Vehicles. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2024, 118, 109438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Yang, R.; Yu, N. Physics-Informed Graph Neural Networks for Collaborative Dynamic Reconfiguration and Voltage Regulation in Unbalanced Distribution Systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 2538–2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, X.; Wen, H.; Member, G.S.; Yang, X.; Yu, X.; Rodriguez-andina, J.J. Adaptive Neural Zeta-Backstepping With Predefined Damping Ratio. Application to DC Motors. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2025, 55, 1701–1705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Lee, Y.; Lee, M.; Jin, D.; Yoon, Y. Estimation of Flux Saturation Model for SynRMs Using Artificial Neural Network. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 3143–3151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.R.; Mahesh, P.; Ray, P. Optimal Elman Recurrent Neural Networks-Based Induction Motor Drives with Estimated Machine Parameters. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 8480–8489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Guo, Y.; Zhu, S.; Tan, N.; Liao, B.; Zhang, H. A Novel Data-Driven DRNN-SMC Model for Redundant Manipulators. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 4322–4333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demora, A.T.; Abdissa, C.M. Neural Network-Based Lower Limb Prostheses Control Using Super Twisting Sliding Mode Control. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 24929–24953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Zhao, X. Complementary Sliding Mode Control via Elman Neural Network for Permanent Magnet Linear Servo System. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 82183–82193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Deng, Y.; Li, H.; Cao, H.; Sun, Z.; Yang, T. Composite Control Based on FNTSMC and Adaptive Neural Network for PMSM System. ISA Trans. 2024, 151, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Liu, N.; Song, J.; Zhang, Y. An Improved Sliding Mode Observer Algorithm for PMSM Based on Deformable Fuzzy Neural Network. AIP Adv. 2025, 15, 025213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhari, R.A.; Shekhar, H. A Review on Design Optimization of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motors for Modern Applications. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 14th International Conference on Communication Systems and Network Technologies (CSNT 2025), Bhopal, India, 7–9 March 2025; pp. 1263–1267. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Z.; Huang, W.; Zhu, S.; Yang, X. Multiobjective Design Optimization of Dual-Stator Unequal-Slot Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 6248–6260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Chen, H.; Mao, Y.; Ye, X.; Kang, R. Robustness-Oriented Design Optimization Approach for Cogging Torque of Batch Production PMSM. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 39, 1711–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, G.; Ge, H.; Wang, G.; Wang, L. Preassigned-Time Sliding-Mode Control of Chaotic Memristive Neural Networks with Time-Varying Delays. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2025, 72, 823–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, C.; Li, F.; Xie, Q.; Liao, Y.; Huang, T.; Yang, C.; Gui, W. Integrated Guidance and Control of Morphing Flight Vehicle via Sliding-Mode-Based Robust Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 3350–3362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Hao, L.Y.; Che, W.W. Bi-LSTM-Based Resilient Data-Driven Integral Sliding Mode Control for UMVs Under Hybrid Attacks. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 6702–6714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, A.; Hosseinabadi, P.A.; Panigrahi, B.K.; Pota, H.R. A Black Start Solution for Voltage-Controlled Inverters with Chattering-Free Fixed-Time Sliding Mode Power Synchronization Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 8015–8026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junejo, A.K.; Tang, Y.; Xu, W.; Ge, J.; Islam, M.R. Adaptive Fast Super-Twisting Sliding Mode Direct Thrust Control for Linear Induction Machine Adapted to Linear Metro. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shi, Q.; Wei, Y.; Wang, M.; Guo, C.; He, L. A Predictive Sliding Control Algorithm and Application to Angle Following of Steer-by-Wire. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Syst. 2025, 55, 2670–2680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lin, J.; Pan, J. Disturbance Rejection with Transmission Torque Constraint Using a Novel EMPC-DSMC Method in Elastic Servo Drive Systems. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2025, 40, 13023–13034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, L.; Tan, M.K.; Lim, K.G.; Teo, K.T.K. Adaptive Disturbance Stability Control for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Based on Radial Basis Function Neural Networks and Backstepping Sliding Mode Control. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2025, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero, J.; Chemori, A.; Creuze, V.; Torres, J. Improved Adaptive High-Order Sliding Mode-Based Control for Trajectory Tracking of Autonomous Underwater Vehicles. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2024, 49, 1337–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Chen, G.; Zhou, Q.; Li, H.; Huang, T. Fully Distributed Model-Free Adaptive Sliding Mode Control for MASs with Hybrid-Attacked Topology. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2025, 22, 12336–12346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, B.; Liu, H.S.; Hao, L. Model-Free Adaptive Sliding Mode Control of Shape Memory Alloy Actuated Parallel Platform. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 160845–160854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Pan, L.; Tian, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, L. Adaptive Fault-Tolerant Fixed-Time Sliding Mode Tracking Control for Steer-by-Wire System with Dual-Three-Phase PMSM. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2025, 74, 7554–7564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahid, F.; Luo, H.; Jiang, Y.; Hasan, M.N. Finite-Time Adaptive Sliding Mode Fault-Tolerant Attitude Control for Flexible Spacecraft. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2025, 33, 1700–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensalem, Y.; Kouzou, A.; Abbassi, R.; Jerbi, H.; Kennel, R.; Abdelrahem, M. Sliding-Mode-Based Current and Speed Sensors Fault Diagnosis for Five-Phase PMSM. Energies 2021, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bensalem, Y.; Abbassi, R.; Jerbi, H. Fuzzy Logic Based-Active Fault Tolerant Control of Speed Sensor Failure for Five-Phase PMSM. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2021, 16, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Reaching Law | Advantages | Disadvantages | Accuracy | Anti—Interference Ability | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVRL |

|

|

|

|

|

| ERL |

|

|

|

|

|

| PRL |

|

|

|

|

|

| GRL |

|

|

|

|

|

| Techniques | Year | Structures | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New variable gain reaching law (NVGRL) [35] | 2025 | where > 0, |

|

|

| Modified exponential reaching law (MERL) [104] | 2024 | where > 0, |

|

|

| Adaptive SMC (ASMC) [105] | 2022 | where > 0, |

|

|

| New compound reaching law (NCRL) [106] | 2023 | where > 0, |

|

|

| Composite reaching law (CRL) [107] | 2025 | where > 0, |

|

|

| Techniques | Year | Structures | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modified variable ERL (MVERL) [72] | 2025 | where > 0 |

|

|

| Variable exponential reaching law [VERL] [97] | 2022 | where > 0 |

|

|

| New SMRL (NSMRL) [98] | 2025 | where > 0 |

|

|

| Novel reaching law (NRL) [108] | 2021 | where > 0 |

|

|

| Novel reaching law (NNRL) [109] | 2025 | where |

|

|

| Techniques | Year | Structures | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Integral sliding mode surface (ISMS) [98] | 2025 | where |

|

|

| Differential-ISMS (DISMS) [103] | 2020 | where |

|

|

| Integral-type TSMS (ITSMS) [107] | 2025 | where |

|

|

| Noval non-singular TSMS (NNTSMS) [121] | 2023 | where |

|

|

| Improved nonsingular fast TSMS (INFTSMS) [72] | 2025 | where c1, c2 > 0. p, q, m, and n be odd positive integers such that 1 < p/q < 2 and m/n > p/q. |

|

|

| Discrete-time fast TSMS (DTFTSMS) [122] | 2024 | where |

|

|

| Techniques | Year | Structures | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New super-twisting algorithm (NSTA) [139] | 2022 | , |

|

|

| Discrete-time super-twisting control (DTSTC) [141] | 2025 | , where , |

|

|

| Second-order sliding-mode (SOSM) [144] | 2019 | , |

|

|

| Cascade SOSMC (CSOSMC) [145] | 2019 | , |

|

|

| State constrained SOSMC (SCSOSMC) [146] | 2024 | , |

|

|

| Techniques | Year | Structures | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

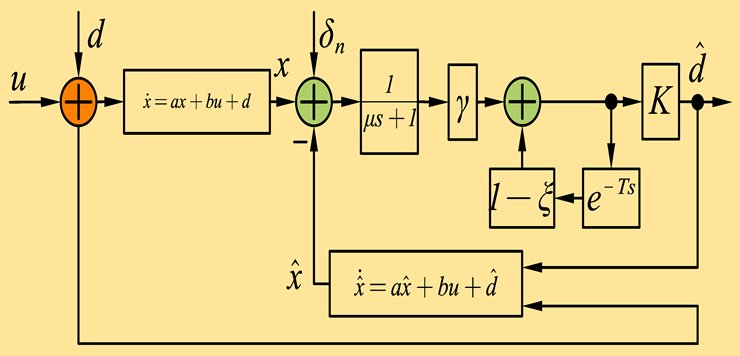

| Extended sliding mode disturbance observer (ESMDO) [158] | 2021 |  |

|

|

| Extended sliding-mode disturbance observer (ESO) [161] | 2023 |  |

|

|

| DOB-Based SOSMC (DOBSOSMC) [159] | 2023 |  |

|

|

| Time-varying two-time scale disturbance observer (TV-TTSDO) [160] | 2024 |  |

|

|

| Novel DOB based on iterative learning strategy (ILC-DOB) [162] | 2023 |  |

|

|

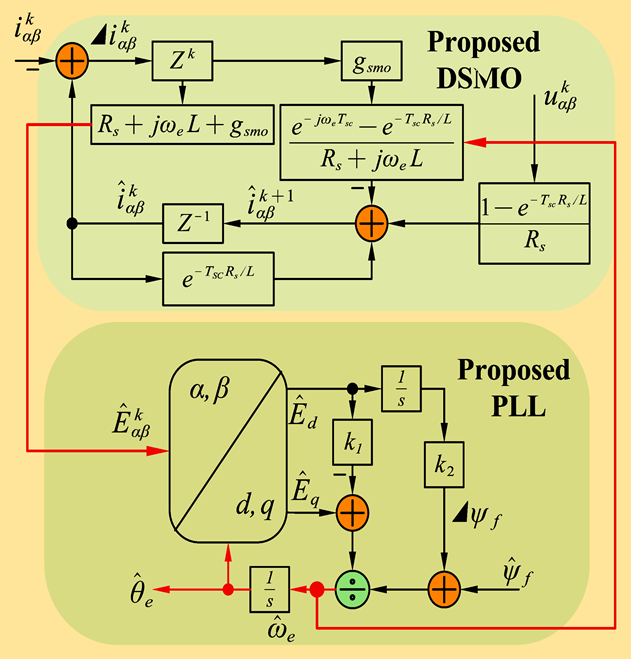

| Techniques | Year | Structures | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMO+LPF+ ACPLL [163] | 2024 |  |

|

|

| GAHOTSMO+ QPLL [78] | 2025 |  |

|

|

| Sigmoid SMO-CCSOSF+QPLL [164] | 2025 |  |

|

|

| Proposed DSMO+PLL [79] | 2024 |  |

|

|

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages | Application Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMC+FL |

| ||

| SMC+NN |

|

| |

| SMC+NN +FL |

|

| |

| SMC+RL |

|

| |

| SMC+ Improved GA |

|

| |

| SMC+PSO |

|

| |

| SMC+ Improved DE |

|

|

|

| SMC+ Improved SSA |

|

|

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages | Application Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaching law approach |

|

|

|

| Sliding surface design |

|

|

|

| SOSMC |

|

|

|

| AOSMC |

|

|

|

| Observer based SMC |

|

|

|

| Intelligent SMC |

|

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tuyen, T.T.; Yang, J.; Liao, L.; Thao, N.G.M. Recent Advances in Sliding Mode Control Techniques for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. Electronics 2025, 14, 3933. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193933

Tuyen TT, Yang J, Liao L, Thao NGM. Recent Advances in Sliding Mode Control Techniques for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. Electronics. 2025; 14(19):3933. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193933

Chicago/Turabian StyleTuyen, Tran Thanh, Jian Yang, Liqing Liao, and Nguyen Gia Minh Thao. 2025. "Recent Advances in Sliding Mode Control Techniques for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives" Electronics 14, no. 19: 3933. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193933

APA StyleTuyen, T. T., Yang, J., Liao, L., & Thao, N. G. M. (2025). Recent Advances in Sliding Mode Control Techniques for Permanent Magnet Synchronous Motor Drives. Electronics, 14(19), 3933. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193933