1. Introduction

This study was motivated by the resolution of persistent failures in a low-voltage (LV) distribution grid. Although power quality measurements indicated compliance with the EN 50160 standard, grid-connected components incorporating power electronic converters were repeatedly failing. Subsequent measurements conducted over an extended frequency range revealed the presence of voltage supraharmonics. Following the identification and elimination of their source, the failures ceased, confirming a strong correlation between supraharmonics and the malfunctioning of power electronic devices. These observations prompted a systematic investigation into the influence of supraharmonics on the operation of various power electronic converters under controlled laboratory conditions, which constitutes the primary focus of this work [

1].

The primary drivers of increased supraharmonic emissions are modern power electronic devices, including those found in renewable energy sources like photovoltaic inverters [

2], electric vehicle chargers [

3,

4] industrial converters, streetlamps [

5], and diverse household appliances [

6]. The pursuit of more compact and efficient equipment has led to the adoption of higher switching frequencies in these devices, directly contributing to the generation of these higher frequency emissions. This phenomenon highlights a fundamental shift in power quality challenges like advancements in power electronics, while enhancing energy efficiency and reducing device size, inherently push distortion into the supraharmonic range [

7,

8].

The pervasive nature of power electronic equipment across residential, commercial, and industrial sectors means that supraharmonics are not isolated incidents but a systemic challenge impacting the entire electrical grid [

9,

10]. This complexity is further amplified by the intricate interactions between multiple devices and the varying impedance of the grid, which can lead to unpredictable behaviour and significant resonance amplification [

8,

11].

Supraharmonic emissions significantly degrade overall power quality and negatively affect electrical distribution systems, leading to reduced efficiency and shortened equipment lifespan [

10]. The consequences are multifaceted, encompassing both immediate operational disruptions and long-term degradation of critical assets.

Adverse effects include equipment malfunctions such as unintended activation of alarms and power supply failures. Specific reported issues involve the tripping of residual current devices (RCDs), noticeable light flicker in LED lamps, disruption of Power Line Communication (PLC), and inaccuracies in smart metre readings [

5,

7,

9].

Over the long term, persistent electromagnetic interference (EMI), voltage distortions, and harmonic resonances contribute to the degradation of component lifespans. Supraharmonics are known to increase dielectric stress, leading to arcing and partial discharges within insulation materials. This accelerates ageing and can result in premature breakdown of these critical components [

5,

7]. Capacitors are particularly susceptible to supraharmonic currents, experiencing increased losses and accelerated ageing due to their lower impedance at these higher frequencies, which provides an easier path for current flow. This additional power consumption also translates into increased operating temperatures, posing a significant thermal challenge. This thermal stress also creates localized hotspots within transformer windings, further degrading insulation and contributing to premature failure [

12]. Ultimately, high levels of supraharmonics can destabilize the electricity grid, particularly with the increasing penetration of distributed energy resources [

13,

14].

The diverse impacts of supraharmonics, ranging from nuisance effects like audible noise and light flicker to critical infrastructure degradation such as insulation ageing and transformer failure, reveal a systemic vulnerability in modern power grids [

5].

Power Factor Correction (PFC) circuits, particularly those employing active control, are identified as significant contributors to supraharmonic emissions [

2]. This creates a complex relationship where a technology designed to improve power quality at fundamental frequencies inadvertently introduces new challenges at higher frequencies.

Active PFC, commonly implemented in AC/DC converters controlled by Pulse Width Modulation, is a primary source of emissions in the 2 kHz–150 kHz range [

2,

7,

15,

16].

The majority of publications addressing the impact of supraharmonics on electrical devices [

8], particularly power electronic converters [

11], focus primarily on the analysis of field-measured data. In contrast, this study presents a systematic investigation of the effects of voltage supraharmonics on power electronic converters under controlled laboratory conditions. A key novelty of this work lies in the stepwise increase in a specific supraharmonic component in the supply voltage, allowing observation of its influence on the amplitude and frequency characteristics of the current drawn by the tested converters.

This work was triggered by repeated failures of grid-connected equipment in an LV network. Extended-band measurements revealed a supraharmonic component coinciding with increased feeder currents and device malfunctions. After the source was mitigated, failures ceased. Building on this observation, we investigate how voltage supraharmonics affect PSUs under controlled conditions.

Section 2 describes the measurements carried out in a real distribution grid, which motivated the subsequent investigation under controlled laboratory conditions. The experimental laboratory setup, testing procedures, and the power electronic converters used in the study are presented in

Section 3. The results of the laboratory tests are detailed in

Section 4, followed by a discussion in

Section 5. Finally, concluding remarks are provided in

Section 6.

2. Measurements in the Grid

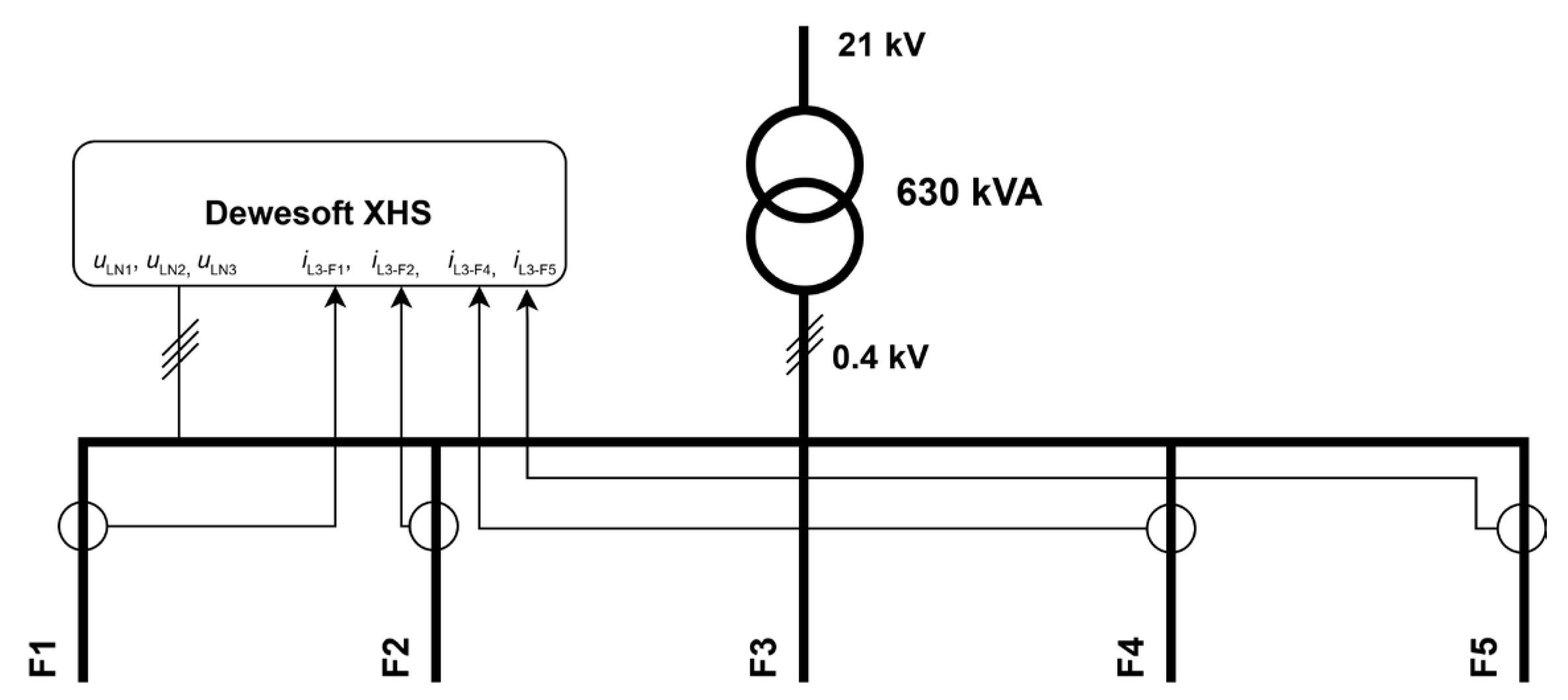

The LV distribution grid under investigation primarily serves residential loads, small industrial consumers (e.g., workshops) and several household photovoltaic (PV) installations. A 630 kVA, 21/0.4 kV transformer supplies five 0.4 kV feeders with connected customers, as illustrated in

Figure 1. Measurements were initiated in response to repeated failures of power electronic converters and unusual audible phenomena observed in a household induction cooker, suspected to be caused by supraharmonic disturbances in the grid. The transformer’s 0.4 kV busbar voltage and the currents of four feeders belonging to the same phase were recorded (see

Figure 1).

A Dewesoft XHS system was used for data acquisition, with a sampling rate of 1 MS/s and 18-bit resolution. The setup included four integrated high-voltage sensor channels (rated up to 2 kVp) and four low-voltage channels connected to Chauvin Arnoux C160 AC current clamps, as shown in

Figure 2.

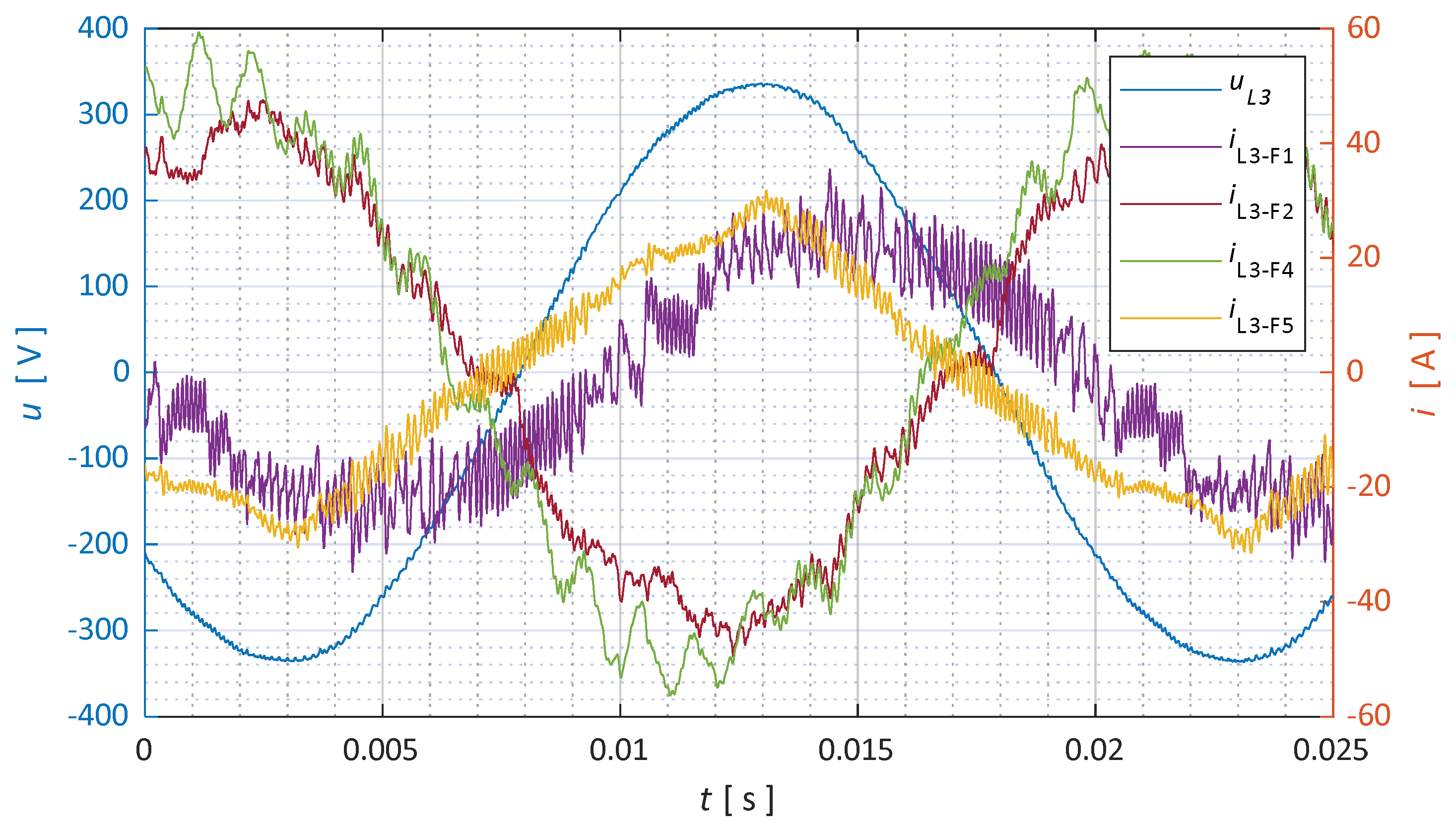

Feeder F1 with the current

iL3-F1, was connected to a workshop. At a specific moment, the waveform of

iL3-F1 indicated the activation of a device with inadequate electromagnetic filtering. This device acted as a source of supraharmonics, which propagated into all feeders with currents

iL3-F2,

iL3-F4 and

iL3-F5, and is clearly visible also in the busbar voltage

uL3, all containing the same frequency components, as illustrated in

Figure 3.

Oscillations in the feeder currents were observed in the frequency range of 6–12 kHz. The corresponding busbar voltage waveform also exhibited clear oscillations at these frequencies, with amplitudes reaching up to 2% of the fundamental 50 Hz voltage component. The highest amplitude of the supraharmonics was recorded at a frequency of 10 kHz. Additionally, an increase in the RMS value of the currents was observed during these events.

3. Laboratory Replication and Supraharmonic Injection

To better understand the interactions and phenomena observed in the grid measurement results (

Figure 3), an experimental setup based on a programmable grid simulator was build up to replicate the observed conditions in a controlled laboratory environment. The objective was to reproduce voltage waveforms similar to those measured in the grid and to analyze the behaviour of various power electronic converters when supplied with voltage distorted by supraharmonics. The highest amplitude of supraharmonic distortion recorded in the field occurred at 10 kHz, corresponding to the 200th harmonic (H200), with an amplitude equal to 2% of the fundamental 50 Hz voltage component.

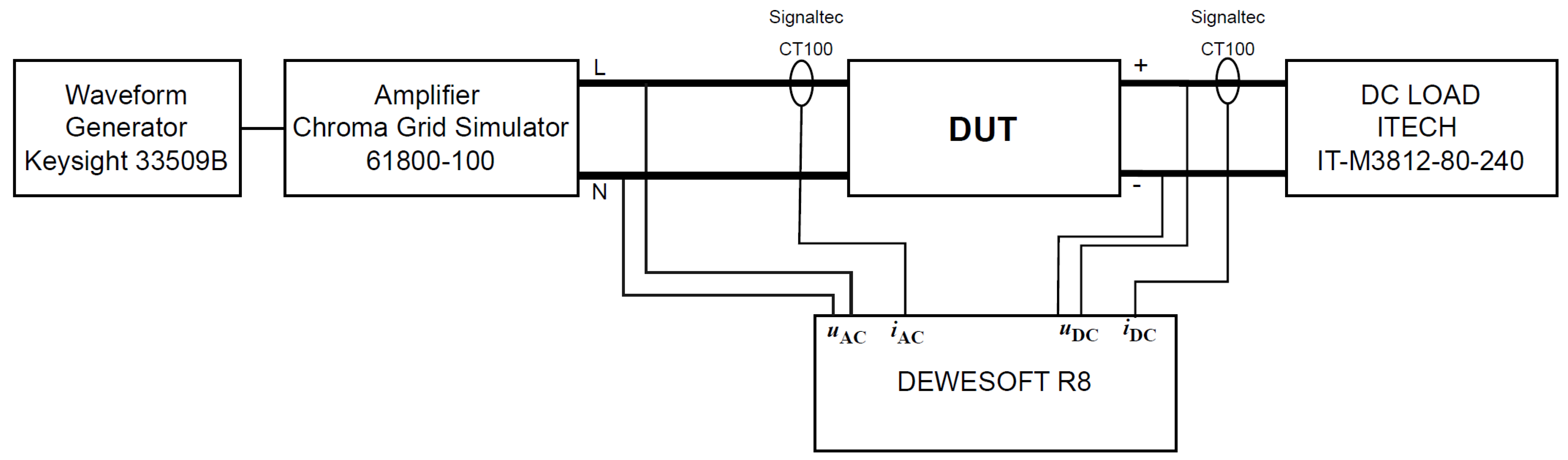

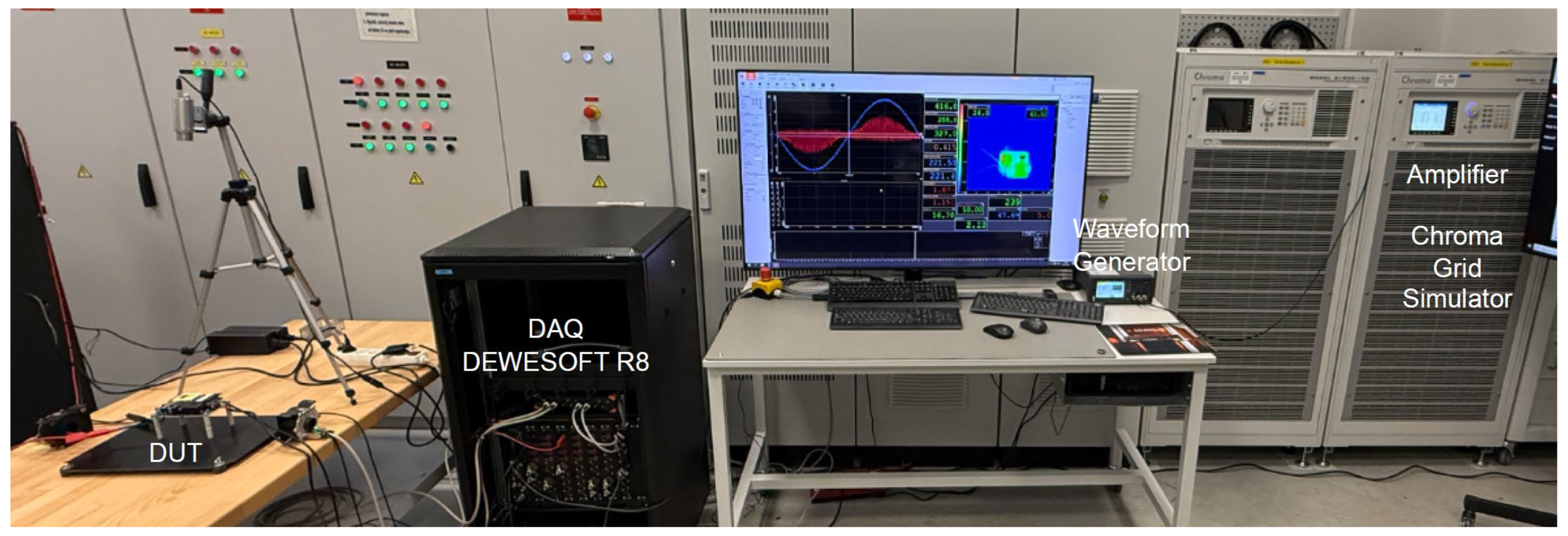

The experimental setup is shown in

Figure 4 and

Figure 5. The voltage source used was a Chroma 61800-100 grid simulator with analogue input capability. A composite signal, consisting of a 50 Hz fundamental component and a 10 kHz supraharmonic component, was generated using a Keysight 33500B signal generator. These two sine waves were summed and fed into the analogue input of the grid simulator. Although the 10 kHz frequency exceeds the nominal bandwidth specified in the Chroma datasheet, a sufficiently amplitude 10 kHz component appeared in the simulator’s output voltage as a superposition onto the 50 Hz fundamental. Data acquisition (DAQ) was performed using a Dewesoft R8 system with a sampling rate of 1 MS/s and integrated voltage sensors rated up to 2 kVp. Current measurements were carried out using Signaltec CT 100 current transducers, featuring a bandwidth from DC to 500 kHz.

Previous studies have demonstrated that power electronic converters are particularly susceptible to supraharmonic disturbances in the supply voltage. To investigate this further, the devices under test (DUTs) were various power electronic converters, each loaded using a DC electronic load (ITECH IT-M3812-80-240).

This study presents the results of laboratory testing for the following power supply units (PSUs):

The PSUs were tested under a load corresponding to two-thirds of their maximum rated output. Specifically, the AIMTEC AMEOF350-48SHAMJZ-B was operated at 2.8 A DC at 48 V, while the MEAN WELL HEP-600-42 was tested at 9.5 A DC at 42 V, both representing approximately 66% of their nominal load. Throughout all measurements, the load remained constant at two-thirds of the nominal power.

During the tests, a supraharmonic voltage component designated H200 at 10 kHz was superimposed on the fundamental supply voltage at 50 Hz. This component corresponds to measurements observed in the real electrical grid (

Figure 3). The injected 10 kHz component was swept from 0 to ≈2% of the 50 Hz amplitude. RMS and peak input currents were computed cycle-by-cycle. Frequency analysis used windowed FFT on high-rate records to resolve the 2–150 kHz band. The amplitude at 10 kHz was tracked together with sidebands and intermodulation products. A scalar metric of voltage supraharmonic distortion at 10 kHz is expressed as percentage of the fundamental amplitude.

Each operating point was recorded multiple times with consistent results, mean values are reported, with qualitative conclusions identical across repetitions.

4. Results

The first tested PSUwas the AIMTEC AMEOF350-48SHAMJZ-B. Initially, the PSU was powered with a pure 50 Hz sinusidal voltage, and a DC load corresponding to two-thirds of the converter’s nominal output was applied, as shown in

Figure 6. Subsequently, a 10 kHz supraharmonic component (H200), replicating conditions observed in field measurements, was superimposed onto the fundamental voltage waveform.

The results presented in

Figure 7 demonstrate a significant increase in input current following the introduction of the supraharmonic component, despite the DC load remaining constant. This suggests that the PSU’s input stage is sensitive to high-frequency voltage components, which may result in increased current consumption and, consequently, elevated thermal stress or electromagnetic interference.

To illustrate the relationship between the amplitude of the supraharmonic voltage component and the resulting converter input current,

Figure 8 depicts a stepwise increase in the amplitude of the 10 kHz (H200) voltage supraharmonic from 0% to 2%. The corresponding rise in current amplitude clearly demonstrates the converter’s sensitivity to high-frequency voltage disturbances.

As shown in

Figure 8, a higher percentage of the added supraharmonic component (H200) in the supply voltage results in a more pronounced increase in both the RMS and peak values of the PSU’s input current. The peak input current increased by up to three times compared to the baseline condition with a pure 50 Hz sinusoidal supply. Additionally, the RMS current increased by approximately 70%. This clearly demonstrates the nonlinear and amplifying effect that supraharmonic voltage components can have on the current drawn by PSU.

Higher amplitudes of supraharmonics in the voltage waveform have a significant impact on the converter’s input current waveform, as clearly illustrated in the frequency domain in

Figure 9. While the dominant frequency component in the voltage remains at 10 kHz (H200), additional frequency components are also present. These become even more pronounced in the current spectrum, where numerous intermodulation and sideband frequencies emerge due to nonlinear interactions within the PSU.

The H200 component exhibits the highest amplitude in both the voltage and current spectra; however, the current spectrum displays a broader range of frequency components, indicating complex harmonic interactions. This spectral broadening is a clear manifestation of the converter’s nonlinear behaviour under supraharmonic excitation.

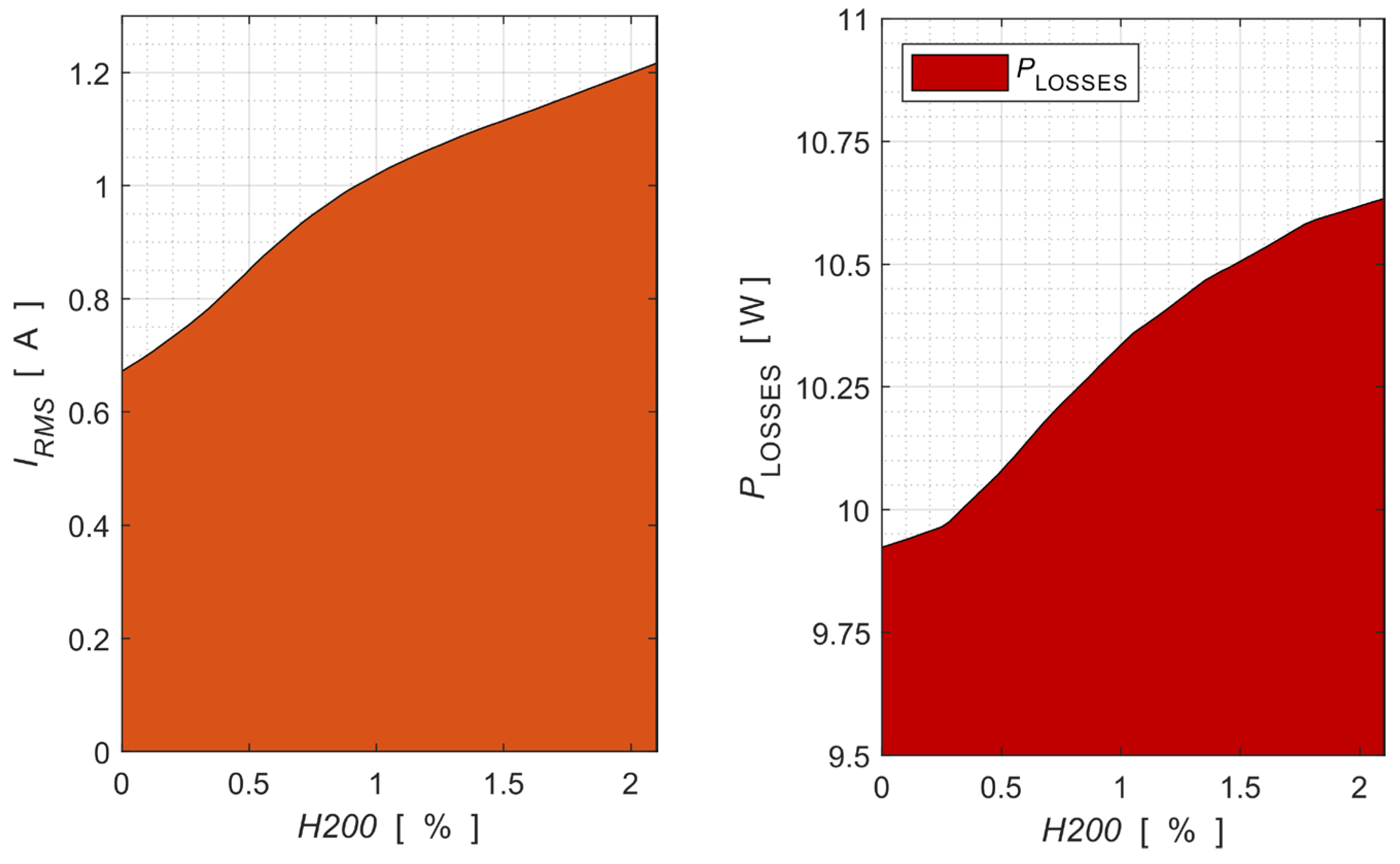

Furthermore, the increase in high-frequency current contributes to a substantial rise in the RMS value of the input current, which scales with the amplitude of the injected H200 component. This relationship is illustrated in

Figure 10.

The increase in RMS current caused by the presence of supraharmonics also results in additional power losses within the PSU. These losses are determined as the difference between the measured input power on the AC side and the measured output power on the DC side of the PSU. As shown in

Figure 10, the losses increase proportionally with the amplitude of the H200 component. In the tested case, total power losses increased by approximately 6%, highlighting the potential impact of supraharmonic distortion on both energy efficiency and thermal performance.

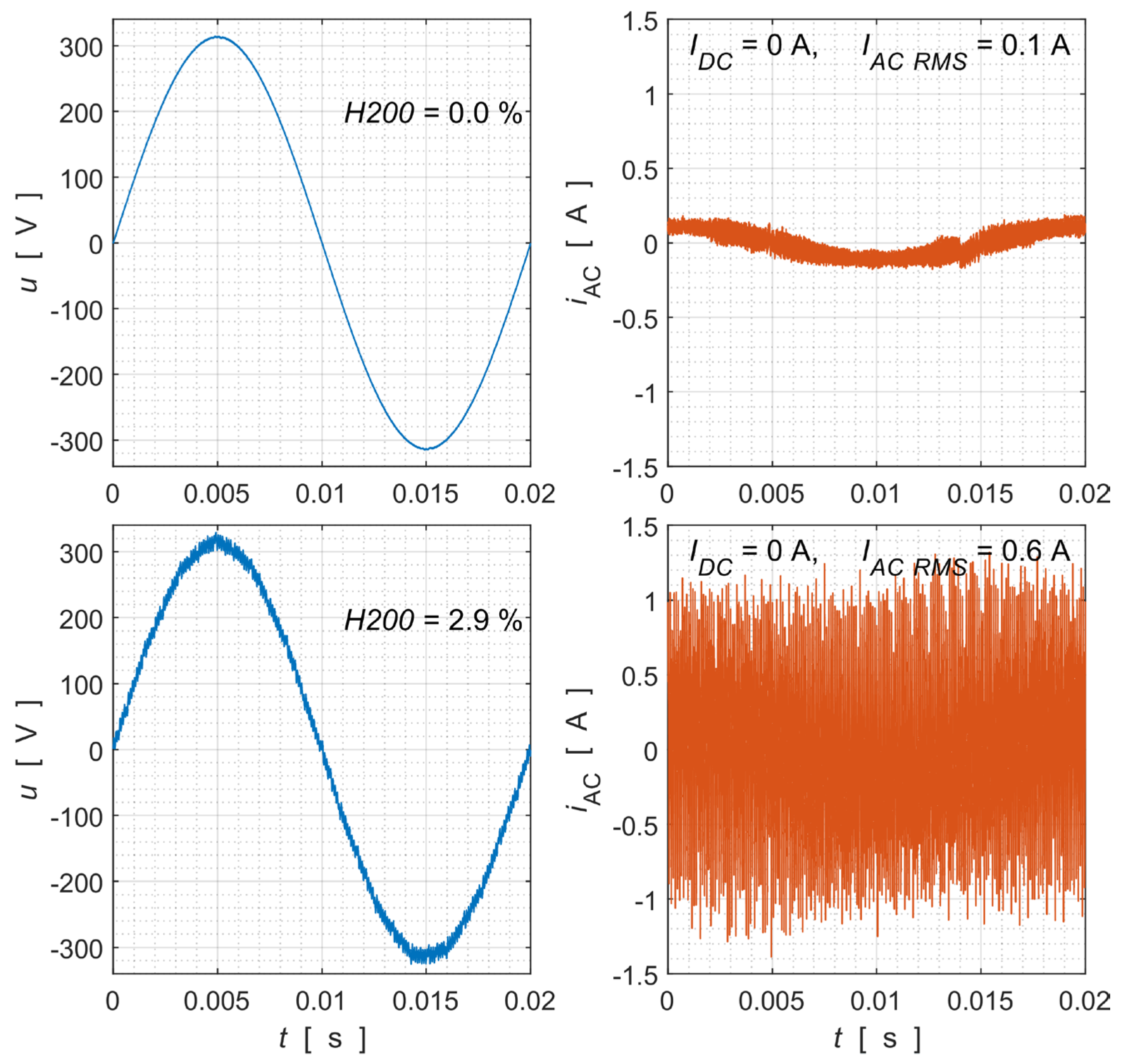

4.1. Impact of Supraharmonics on No-Load Power Supply Operation

Many electronic devices equipped with PSU’s operate predominantly in idle or standby mode, drawing minimal power from the grid while supplying no active load on the DC side. To investigate the impact of supraharmonic disturbances on such devices, the AC input current of a PSU was measured under no-load conditions. Two scenarios were examined: one with a pure 50 Hz sinusoidal supply voltage, and the other with a 10 kHz (H200) supraharmonic component superimposed on the 50 Hz sinusoidal waveform.

Results of measurements presented in

Figure 11 shows that the presence of the supraharmonic component in the supply voltage causes a substantial increase in current peaks up to ten times higher than in the case of a pure 50 Hz sinusoidal supply. The RMS value of the input current also rises significantly, from 0.1 A to 0.6 A, representing a sixfold increase. This finding suggests that even when not actively in use, devices connected to a grid voltage contaminated with supraharmonics can draw considerably higher RMS currents than expected. For devices incorporating PSUs, being plugged into a grid with supraharmonic distortion may lead to increased energy consumption, higher internal losses, and greater electrical and thermal stress on both the device and the grid infrastructure.

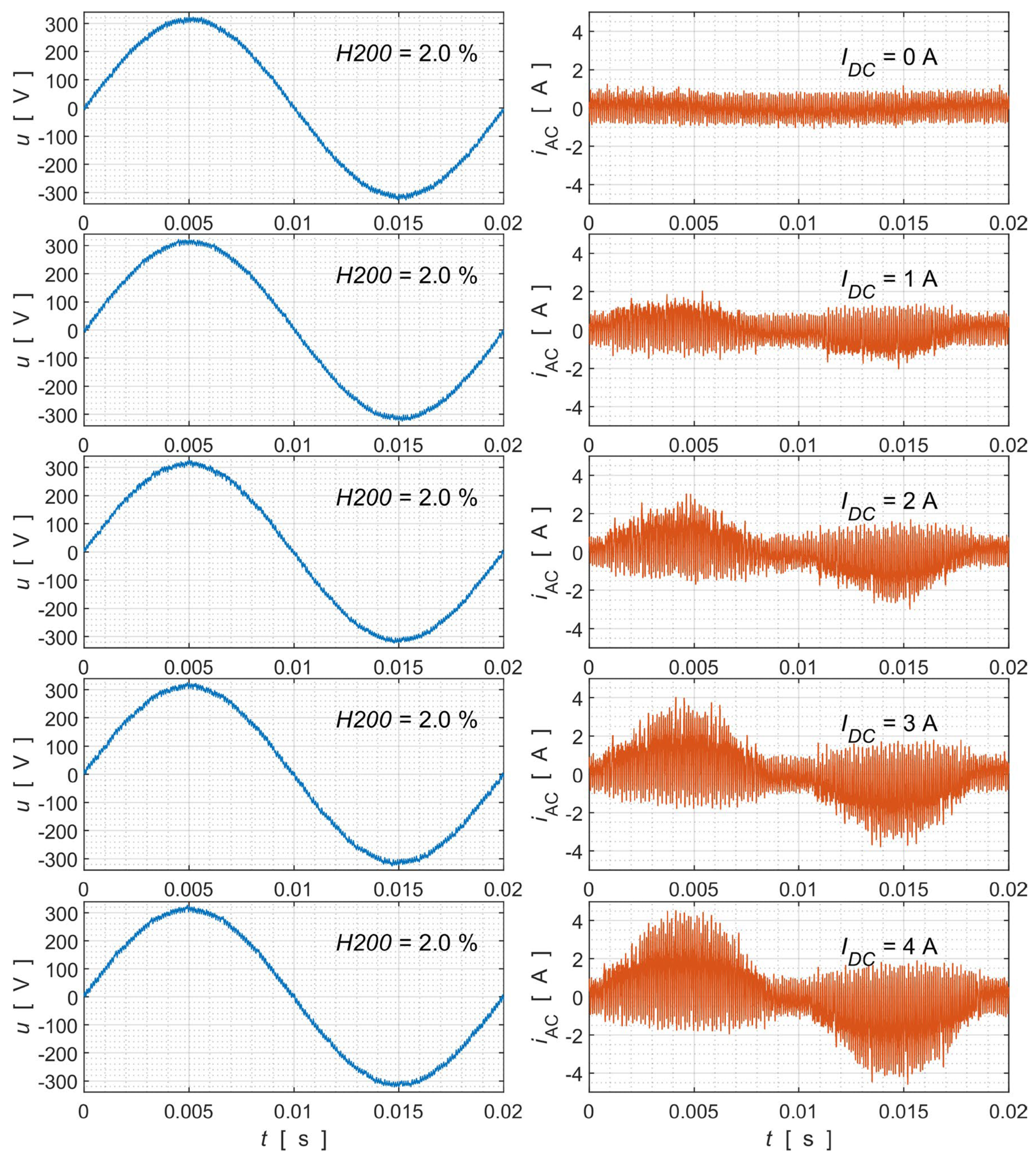

4.2. Impact of DC Load Variation on Supraharmonic Currents

To investigate the impact of DC load variation on the supraharmonic content of the input current in the tested AIMTEC PSU, a series of tests, similar to those previously described, was conducted. In this case, the supply voltage waveform was kept constant, with a fixed 2% amplitude 10 kHz (H200) supraharmonic component superimposed on the fundamental 50 Hz sinusoidal voltage.

Figure 12 shows that the DC load was gradually increased from 0% to 100% of the PSU’s rated output power, corresponding to a current range from 0 A to 4 A. Despite the increasing load, the amplitude of the H200 component in the measured input current remained relatively stable, indicating that the supraharmonic content is primarily determined by the distortion present in the supply voltage rather than by the load level.

According to the measurement results presented in

Figure 12, increasing the DC load naturally results in a higher RMS input current, as expected. However, it is also important to examine the behaviour of current peaks, particularly the high-frequency ripple components, under varying load conditions.

In this test, the peak values of the supraharmonic current spikes increased from approximately 1 A under no-load conditions (0%) to 4 A at full load (100%). While this represents a notable change, it is relatively modest compared to the results shown in

Figure 8, where the introduction of a 10 kHz (H200) supraharmonic in the supply voltage caused the peak ripple current to rise from 0.2 A to 2 A, representing a tenfold increase. This comparison highlights that the amplitude of supraharmonics in the current is far more sensitive to the presence and magnitude of supraharmonics in the voltage than to the load level itself.

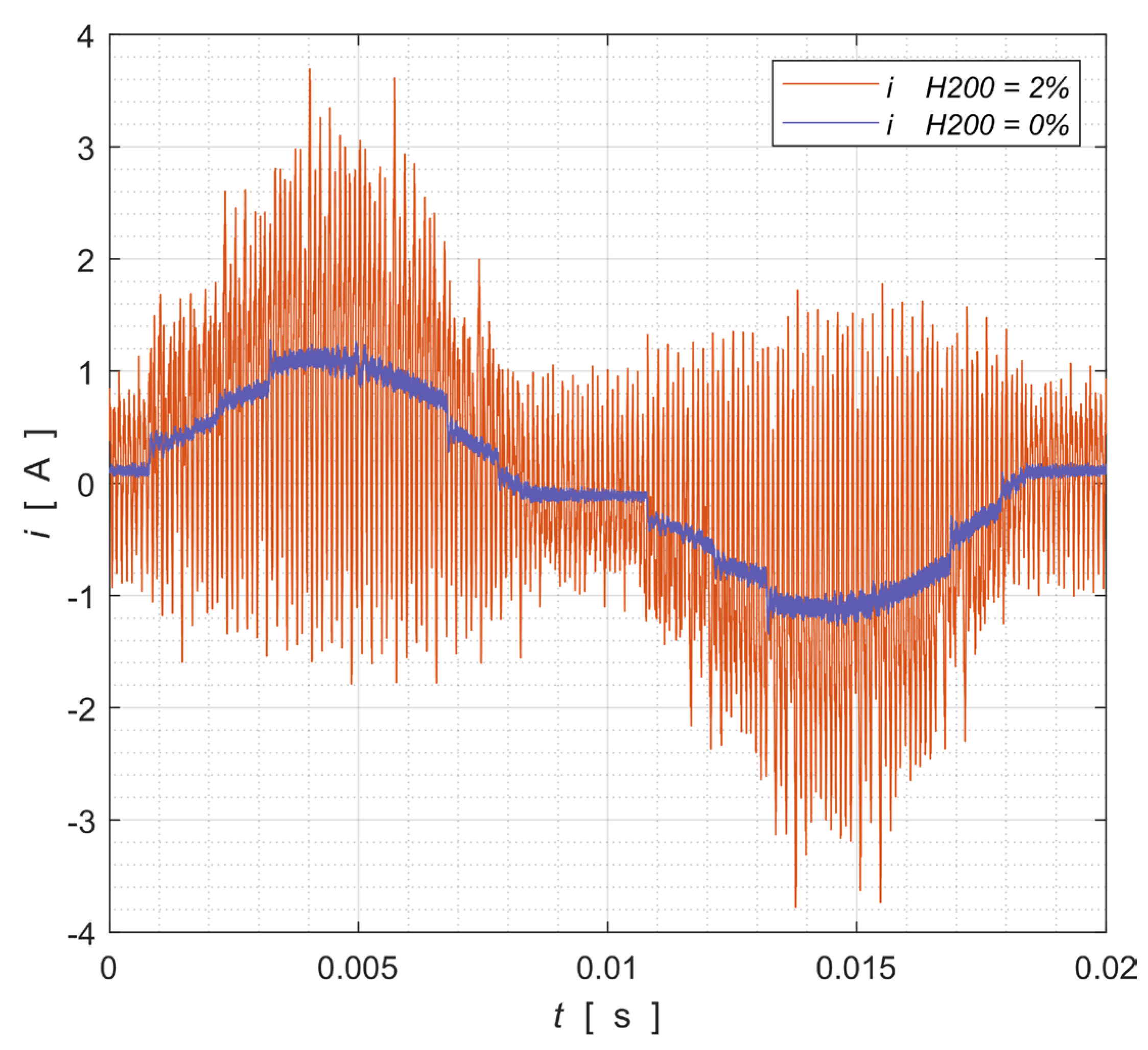

Another important observation from the laboratory tests is that the supraharmonic current component crosses zero, a behaviour not observed when the converter is supplied solely by pure 50 Hz sinusoidal voltage. This phenomenon, illustrated in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14, suggests a fundamental change in the waveform symmetry and spectral content of the converter’s input current, caused by the presence of supraharmonics in the supply voltage. The results presented in

Figure 13 and

Figure 14 correspond to the AIMTEC PSU operating at two-thirds of its rated DC output power.

Figure 14 shows the supraharmonic current waveform exhibiting large amplitude variations over very short time intervals, resulting in a high current change rate (

di/

dt). These rapid current transients can have adverse effects on both the internal components of power electronic devices and the surrounding grid infrastructure.

High di/dt values increase the stress on switching elements, capacitors, and magnetic components within the PSU. In the grid, such sharp current transients can exacerbate the skin effect, resulting in increased conductor resistance at high frequencies. Furthermore, they contribute to elevated core losses in ferromagnetic materials, such as those used in transformers and inductors, due to increased eddy current formation and hysteresis losses.

These effects highlight the importance of understanding and mitigating supraharmonic emissions, particularly in systems containing sensitive components or elements whose performance is frequency-dependent.

4.3. Testing of an Additional Power Supply Unit (PSU)

To determine whether the observed effects were specific to the AIMTEC AMEOF350-48SHAMJZ-B PSU or common among other power electronic converters, a second PSU—the MEAN WELL HEP-600-42 was tested under identical conditions. This enabled a comparative analysis of the converters’ behaviour in the presence of supraharmonics in the supply voltage.

The procedure applied for testing the second PSU (MEAN WELL HEP-600-42) was similar to that used for the first PSU (AIMTEC AMEOF350-48SHAMJZ-B). The converter was initially powered with a pure 50 Hz sinusoidal supply voltage, followed by the superimposed injection of a 10 kHz (H200) supraharmonic component, with its amplitude incrementally increased from 0% to 2.1%. The DC load was fixed at two-thirds of the PSU’s rated output power.

The results presented in

Figure 15 show that a higher percentage of the added supraharmonic component (H200) in the supply voltage leads to a more pronounced increase in both the RMS and peak values of the PSU’s input current. The peak input current approximately doubled compared to the baseline condition with a pure 50 Hz sinusoidal supply, while the RMS current increased by around 50%. These findings clearly confirm that the presence of high-frequency components in the supply voltage significantly amplifies the current drawn by the tested PSU.

In the frequency domain, the MEAN WELL HEP-600-42 PSU exhibited similar behaviour to the AIMTEC unit. As shown in

Figure 16, a wide range of additional frequency components appeared in the current spectrum beyond the injected 10 kHz (H200) supraharmonic. This spectral broadening indicates nonlinear interactions within the converter, resulting in the generation of intermodulation products and additional supraharmonics. These findings further underscore the sensitivity of such devices to the presence of supraharmonic distortion in the supply voltage.

The increase in RMS current due to the presence of supraharmonics also leads to additional power losses within the PSU, as shown in

Figure 17. These losses are defined as the difference between the measured input power on the AC side and the measured output power on the DC side of the PSU. As the amplitude of the H200 supraharmonic component increases, the power losses also rise. In the case of the tested HEP PSU, total power losses increased by approximately 11%, highlighting the potential impact of supraharmonic distortion on both energy efficiency and thermal performance.

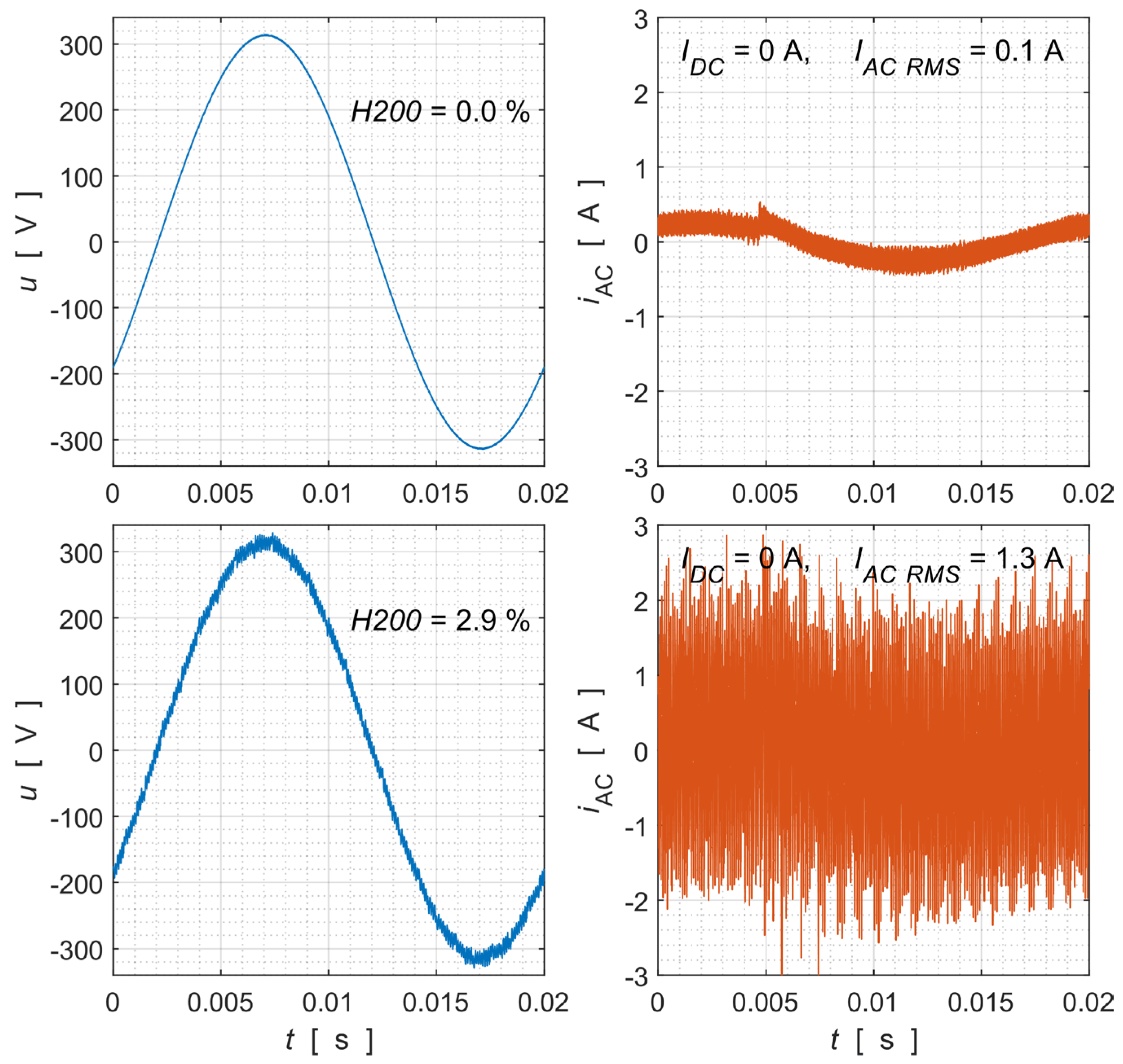

Similarly to the AIMTEC converter, the MEAN WELL HEP-600-42 PSU also exhibited a significant increase in input current, both in peak and RMS values, when operating without a load and supplied with a voltage contaminated by supraharmonic disturbances. Under no-load conditions, the PSU was first powered with a pure 50 Hz sinusoidal supply voltage, followed by a 50 Hz voltage waveform superimposed with a 10 kHz (H200) supraharmonic component.

Figure 18 shows the increase in the RMS value of the PSU input current from 0.1 A to 1.3 A when supraharmonic component appeared in the supply voltage.

This represents a more than tenfold increase in the RMS current, despite the absence of any load on the DC side of the PSU. Such behaviour indicates that PSUs can draw significantly more current than expected simply by being connected to a grid voltage contaminated by supraharmonics, as shown in

Table 1 and

Table 2. This has important implications for standby energy consumption, thermal stress on components, and the cumulative impact on the power system when many devices are left plugged in grid.

Similarly to the AIMTEC converter, the MEAN WELL HEP-600-42 PSU also exhibited a significant increase in input current, both in peak and RMS values, when operating without a load and supplied with a voltage waveform contaminated by supraharmonic disturbances. Under no-load conditions, the PSU was initially powered by a pure 50 Hz sinusoidal supply voltage, followed by a 50 Hz waveform superimposed with a 10 kHz (H200) supraharmonic component. As shown in

Figure 18 and

Table 2, the RMS value of the PSU input current increased from 0.1 A to 1.3 A upon the introduction of the supraharmonic component.

This represents more than a tenfold increase in RMS current, despite the absence of any load on the DC side of the PSU. Such behaviour demonstrates that power supplies can draw substantially higher input currents simply due to the presence of supraharmonics in the supply voltage. This finding has important implications for standby energy consumption, thermal stress on internal components, and the cumulative impact on the power system when numerous devices remain connected to a supraharmonics-contaminated grid.

5. Discussion

The results of this study confirm that supraharmonic disturbances in the supply voltage waveform can significantly influence the behaviour of power supply units, even under no-load conditions. This finding aligns with previous research, which has shown that power electronic converters are particularly sensitive to high-frequency voltage components due to their internal switching mechanisms and input filter designs.

Measurements conducted in a real low-voltage grid revealed that poorly filtered devices can introduce supraharmonics, primarily in the frequency range around 10 kHz (H200), which propagate through the grid and affect other connected equipment. This observation is consistent with earlier studies indicating that supraharmonics can travel across multiple outlets and feeders, interact with other converters, and potentially trigger resonance phenomena or increased electromagnetic interference (EMI).

In both field and laboratory conditions, the presence of supraharmonics in the supply voltage led to a notable increase in the RMS and peak values of the input current drawn by power electronic converters. The emergence of additional frequency components in the current spectrum indicates nonlinear interactions within the converters. A substantial rise in RMS and peak current values was observed even under no-load conditions, with RMS values increasing by up to 13 times compared to the baseline.

These findings suggest that supraharmonics not only degrade power quality but also result in elevated energy consumption, increased thermal stress, and potentially reduced long-term reliability of power supplies. This is particularly concerning given the growing prevalence of electronic devices that remain continuously connected to the grid in idle or standby mode.

The experiments confirm that PSUs with active PFC are sensitive to modest supraharmonic voltage components. The spectral broadening and high di/dt pulses in the input current imply elevated EMI risk and increased stress on rectifiers, boost inductors, capacitors, and magnetic components. Persistent operation under such conditions increases RMS current and losses, raising internal temperatures and accelerating ageing of electrolytics and insulation. From a system perspective, aggregation of supraharmonic currents across many devices can excite feeder resonances and interfere with PLC. Increased RMS currents and high-frequency components can contribute to additional copper and core losses in transformers and to nuisance tripping of RCDs. The field case underscores how a single poorly filtered converter can perturb multiple feeders.

6. Conclusions

This study investigated the influence of supraharmonic disturbances in the supply voltage on the behaviour of power supply units (PSUs) under both field and laboratory conditions. The findings clearly demonstrate that supraharmonics can significantly affect the current drawn by PSUs, even when operating under no-load conditions. Supraharmonic components in the supply voltage waveform lead to substantial increases in both RMS and peak current values. The current spectrum becomes considerably more complex, with additional frequency components emerging due to nonlinear interactions within the converters. Even in idle mode, PSUs may draw several times higher RMS and peak current values when exposed to supraharmonic disturbances in the supply voltage. This behaviour contributes to unnecessary energy consumption and imposes additional stress on the grid infrastructure. Notably, the observed effects were consistent across different PSU models, indicating a broader vulnerability inherent in conventional converter designs. These results underscore the urgent need for improved filtering in power electronic converters and for greater attention to supraharmonic emissions and immunity in power quality standards. As the number of grid-connected power electronic devices continues to grow, effectively addressing supraharmonic-related issues will be essential to ensuring energy efficiency, equipment longevity, reliable operation, and the overall resilience and stability of electrical grids.

There is a clear necessity for enhanced high-frequency filtering in power electronic devices to mitigate both the injection of supraharmonic currents and the effects of incoming supraharmonic voltage disturbances. Many existing converters lack sufficient attenuation in the 2–150 kHz range, leaving them susceptible to performance degradation, increased current draw, thermal stress, and potential long-term reliability issues.

Equally important is the need to raise awareness among manufacturers, designers, and consumers regarding the hidden risks and inefficiencies associated with supraharmonic pollution. Devices may appear to operate normally while in fact drawing excessive current or generating unintended supraharmonic emissions, particularly when in standby mode but still connected to the grid. Tackling this challenge requires not only technical improvements but also broader education and recognition of the implications of power quality beyond traditional harmonic distortion.