A Reinforcement Learning Framework for Scalable Partitioning and Optimization of Large-Scale Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problems

Abstract

1. Introduction

- We propose SPORL, a novel two-phase RL framework that effectively decomposes large-scale CVRP instances into manageable subproblems for parallel solving, addressing the critical scalability challenge.

- We introduce a context-based attention mechanism enhanced with sub-route embeddings. This innovation provides a richer representation of the local solution structure during partitioning, leading to more informed and constraint-aware decisions than the previous method [30].

- We demonstrate through extensive experiments that SPORL achieves a superior balance between solution quality and computation time. It significantly outperforms pure learning-based methods (AM, POMO) and enables classical solvers like LKH3 to find high-quality solutions orders of magnitude faster.

- We provide comprehensive ablation studies and analyses that validate the effectiveness of our core components and offer insights into the performance characteristics of hybrid learning-optimization systems.

2. Related Work

3. Problem Formulation

3.1. Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem

3.2. Set Partitioning Formulation for CVRP

4. Reinforcement Learning for the Partitioning Problem

4.1. MDP Definition and Alignment with CVRP

- State : The state at time t encodes the set of unassigned customers, the remaining vehicle capacity of the current route, and the partial sub-routes constructed so far.

- Action : The agent selects the next unvisited customer (or the depot) to extend or close the current sub-route, thereby incrementally contributing to a partition of the original customer set.

- Reward R: The episodic reward is defined as the negative total travel distance once all customers have been assigned and all routes have been completed. Infeasible solutions (e.g., exceeding the fleet size m) receive a large negative penalty.

- Policy : The reinforcement learning agent learns a stochastic policy that maps states s to partitioning decisions, improving over time through accumulated experience. The policy over a complete solution can be factorized and parameterized aswhere denotes the action selected at step t, conditioned on the state s and the sequence of past actions .

4.2. Model Architecture for Partitioning Problem

- Encoder: The encoder computes the initial -dimensional node embeddings, denoted as , from the input , which consist of the node’s coordinates and demand, along with the graph embedding . Following the Transformer architecture [29] and the Attention Model in [21], both the node embeddings and the graph embedding serve as inputs to the decoder.

- Decoder: The decoder follows the same architecture as proposed in [21], generating solutions sequentially. At each time step t, it selects a node for each sub-route based on the encoder embeddings and the previously selected nodes. The decoding process utilizes a special context node c to facilitate efficient decision-making. Final selection probabilities are computed using a single-head attention mechanism.where is the context query at time t; is the key; the value ; are learning parameters; and is the dimension of hidden state. This masking strategy ensures that capacity constraints are never violated during the construction process. The fleet size constraint is enforced naturally by the process itself: the episode terminates once all nodes have been visited. If the number of routes created equals the fleet size () but unvisited nodes remain, the solution is invalid and receives a large negative reward during training. This incentivizes the RL agent to learn a policy that partitions the graph into at most () capacity-feasible clusters

- Capacity constraints: To enforce the vehicle capacity constraint Q, the model must track the remaining capacity throughout the route construction process. We define a state variable representing the normalized remaining capacity for the current vehicle at time step t, where a value of 1 represents a full capacity and 0 represents an empty vehicle. This variable is initialized and updated as follows:The update rule decreases the normalized capacity by the relative demand of the served customer (). The value is reset to 1 when the vehicle’s capacity is exhausted () or at the start of a new route (), signifying a new vehicle beginning with full capacity. This check ensures that only feasible actions are available for selection, guaranteeing that no vehicle is ever overloaded.

- Context Embedding: The context node represents the current state or context of the decoding process. The context node c of the decoder at time t comes from the encoder and the output up to time t. In existing works [30], the context embedding typically consists of the graph embedding , and the embeddings of the first and last selected nodes (e.g., ) formulated asHowever, this formulation lacks specific information about the local structure of the sub-routes being constructed. As a result, it provides insufficient contextual signals to the decoder, which may lead to suboptimal routing decisions, especially in complex scenarios with multiple interacting sub-tours.To address this limitation, we provide sufficient information to the decoder at any time step t by proposing a more comprehensive context by extending the context node . In our case, this consists of the embedding of the graph , embedding of the sub_graph (containing the nodes of the sub_route) , and the previous (last) node . However, in cases where the vehicle capacity is saturated or , the context embedding consists of the node embedding of the depot and a randomly selected unvisited node , with the remaining capacity sets as in (10). Formally, the context embedding is defined aswhere is the remaining vehicle capacity, and is the embedding of the current sub-route, computed as the average of the node embeddings of the customers already visited on that route:The set contains all nodes assigned to the current vehicle’s tour, forming a partial solution. The sub-route embedding is computed as the average of the node embeddings for all customers in . This operation produces a compact representation that encodes the structural properties of the sub-route, effectively summarizing its current state. By integrating this rich contextual information, the decoder gains awareness of the local structure of the evolving solution, leading to more adaptive decision-making and significantly improved partition quality.

4.3. Training Process

4.3.1. Loss Function

4.3.2. Policy Optimization

4.3.3. Training Procedure

| Algorithm 1 Training Algorithm |

Require: policy network , number of epochs E, batch size B, number of training iterations T, Route Optimization TSP Ensure: Optimized policy parameters

|

4.3.4. Route Optimization

- Traditional Heuristics: As a baseline, we also considered classical optimization algorithms such as LKH3 (a variant of the Lin–Kernighan heuristic).

5. Experiments

5.1. Experimental Setup

5.2. Datasets

5.3. Evaluation Metric

5.4. Performance Evaluation

- Medium-Sized Instances :Table 1 presents the performance results for medium-sized problem instances in the benchmark set. Our proposed approach, SPORL-LKH3, achieved an average optimality gap of 8.53% on the dataset, demonstrating a substantial improvement over the AM and POMO baselines, which yielded gaps of 241.29% and 179.86%, respectively. In particular, incorporating the LKH3 heuristic enabled our method to achieve significantly smaller gaps than the other approaches. Moreover, the computation time in Table 3 is drastically reduced (0.45 s on average) compared to the standalone LKH3, which required up to 15 h. Compared to state-of-the-art solvers, SPORL-LKH3 consistently generated the best solutions in under 2 s, clearly outperforming both AM and POMO in terms of solution quality and efficiency

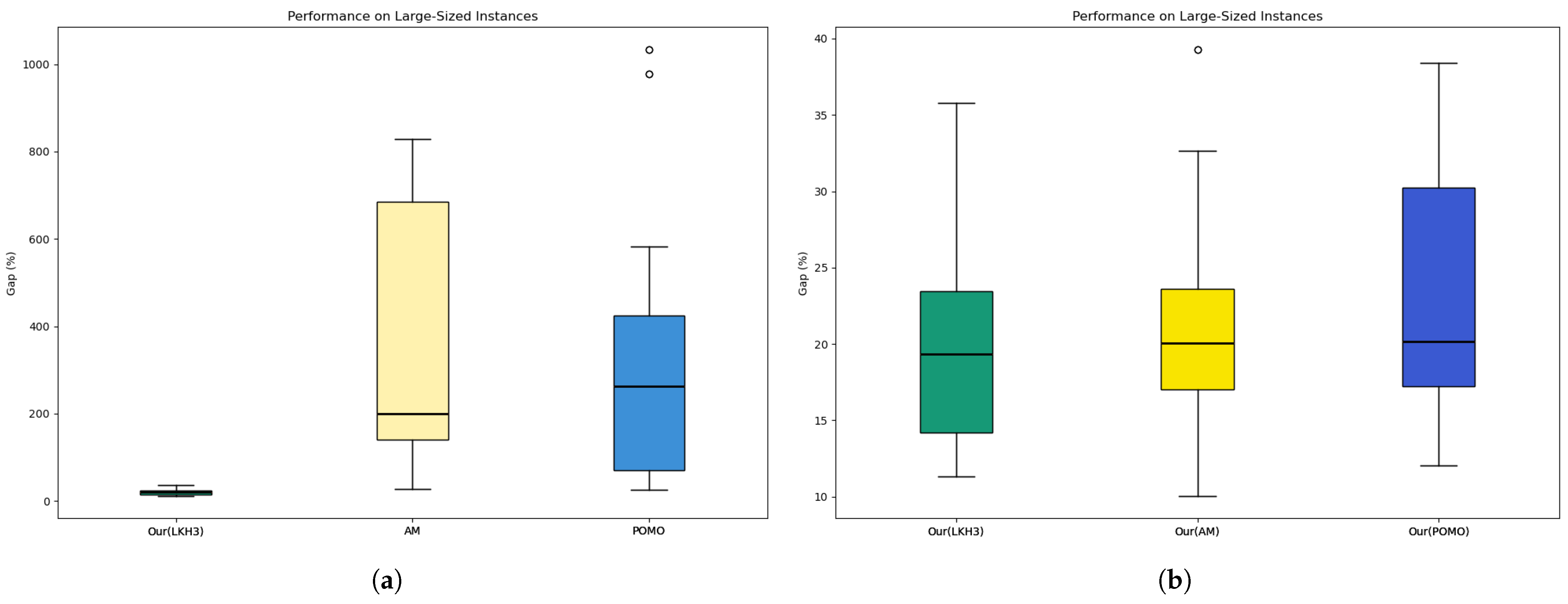

- Large-Sized Instances :Table 2 also reports the performance on the larger problem instances from the benchmark set. Consistently with the results observed on medium-sized instances, our method SPORL-LKH3 achieved a mean optimality gap of less than 3.3% relative to the best known solutions. This marks a significant improvement over the AM and POMO heuristics, which exhibited average gaps of 80.4% and 74%, respectively, across all instances in this category.

- Comparison of Route Optimization Methods:To understand the effect of the downstream solver, we compared the performance of SPORL-LKH3, SPORL-AM, and SPORL-POMO. The results in Table 1 and Table 2 show that SPORL-LKH3 consistently struck the best balance between solution quality and computational time. For example, on the X-n701-k44 instance, SPORL-LKH3 achieved a gap of 11.77% in 2.07 s, outperforming SPORL-AM and SPORL-POMO, which achieved gaps of 17.02% and 16.58%, respectively, with similar runtimes in Table 3 and Table 4. This highlights the effectiveness of combining our learned partitioning strategy with a powerful heuristic solver such as LKH3.

5.5. Ablation Study: Impact of Context Embedding

6. Discussion

Real-World Applicability

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Golden, B.L.; Raghavan, S.; Wasil, E.A. The Vehicle Routing Problem: Latest Advances and New Challenges; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; Volume 43. [Google Scholar]

- Bullo, F.; Frazzoli, E.; Pavone, M.; Savla, K.; Smith, S.L. Dynamic vehicle routing for robotic systems. Proc. IEEE 2011, 99, 1482–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosoda, J.; Maher, S.J.; Shinano, Y.; Villumsen, J.C. A parallel branch-and-bound heuristic for the integrated long-haul and local vehicle routing problem on an adaptive transportation network. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 165, 106570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Bian, X.; Mei, X. An Adaptive Multi-Objective Genetic Algorithm for Solving Heterogeneous Green City Vehicle Routing Problem. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campuzano, G.; Lalla-Ruiz, E.; Mes, M. The two-tier multi-depot vehicle routing problem with robot stations and time windows. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 147, 110258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Yang, T. Improved Adaptive Large Neighborhood Search Combined with Simulated Annealing (IALNS-SA) Algorithm for Vehicle Routing Problem with Simultaneous Delivery and Pickup and Time Windows. Electronics 2025, 14, 2375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lan, H.; Saldanha-da Gama, F.; Chen, Y. On Optimizing a Multi-Mode Last-Mile Parcel Delivery System with Vans, Truck and Drone. Electronics 2021, 10, 2510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldacci, R.; Mingozzi, A.; Roberti, R. Recent exact algorithms for solving the vehicle routing problem under capacity and time window constraints. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 218, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, P.; Vigo, D. The Vehicle Routing Problem; SIAM: Bangkok, Thailand, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Christofides, N.; Mingozzi, A.; Toth, P. Exact algorithms for the vehicle routing problem, based on spanning tree and shortest path relaxations. Math. Program. 1981, 20, 255–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naddef, D.; Rinaldi, G. 3. Branch-And-Cut Algorithms for the Capacitated VRP. In The Vehicle Routing Problem; Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2002; pp. 53–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, C.C.; Hansen, P.; Desaulniers, G.; Desrosiers, J.; Solomon, M.M. Accelerating Strategies in Column Generation Methods for Vehicle Routing and Crew Scheduling Problems; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Perron, L.; Furnon, V. OR-Tools. 2019. Available online: https://developers.google.com/optimization (accessed on 3 September 2025).

- Helsgaun, K. An Extension of the Lin-Kernighan-Helsgaun TSP Solver for Constrained Traveling Salesman and Vehicle Routing Problems; Roskilde University: Roskilde, Denmark, 2017; Volume 12, pp. 966–980. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, G.; Wright, J.W. Scheduling of vehicles from a central depot to a number of delivery points. Oper. Res. 1964, 12, 568–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, T.; Crainic, T.G.; Gendreau, M.; Lahrichi, N.; Rei, W. A hybrid genetic algorithm for multidepot and periodic vehicle routing problems. Oper. Res. 2012, 60, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidal, T. Hybrid genetic search for the CVRP: Open-source implementation and SWAP* neighborhood. Comput. Oper. Res. 2022, 140, 105643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinyals, O.; Fortunato, M.; Jaitly, N. Pointer networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2015, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bello, I.; Pham, H.; Le, Q.V.; Norouzi, M.; Bengio, S. Neural Combinatorial Optimization with Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1611.09940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazari, M.; Oroojlooy, A.; Snyder, L.V.; Takác, M. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Solving the Vehicle Routing Problem. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1802.04240. [Google Scholar]

- Kool, W.; van Hoof, H.; Welling, M. Attention, Learn to Solve Routing Problems! arXiv 2019, arXiv:1803.08475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y.; Choo, J.; Kim, B.; Yoon, I.; Min, S.; Gwon, Y. POMO: Policy Optimization with Multiple Optima for Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2010.16011. [Google Scholar]

- Kool, W.; van Hoof, H.; Gromicho, J.; Welling, M. Deep Policy Dynamic Programming for Vehicle Routing Problems. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2102.11756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottung, A.; Kwon, Y.D.; Tierney, K. Efficient Active Search for Combinatorial Optimization Problems. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2106.05126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hottung, A.; Tierney, K. Neural large neighborhood search for the capacitated vehicle routing problem. In ECAI 2020; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 443–450. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick, J.; Ajwani, D.; Carroll, P. A scalable learning approach for the capacitated vehicle routing problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2024, 171, 106787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yan, Z.; Wu, C. Learning to Delegate for Large-scale Vehicle Routing. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2107.04139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, Z.; Wang, H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, M.; Li, Y. RBG: Hierarchically Solving Large-Scale Routing Problems in Logistic Systems via Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the KDD ’22 28th ACM SIGKDD Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Washington, DC, USA, 14–18 August 2022; pp. 4648–4658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, L.; Polosukhin, I. Attention Is All You Need. arXiv 2023, arXiv:1706.03762. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hou, Q.; Yang, J.; Su, Y.; Wang, X.; Deng, Y. Generalize learned heuristics to solve large-scale vehicle routing problems in real-time. In Proceedings of the Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Tian, Y. Learning to perform local rewriting for combinatorial optimization. In Proceedings of the NIPS’19: 33rd International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 8–14 December 2019; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2019; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, C.C.; Hansen, P.; Taillard, E.D.; Voss, S. POPMUSIC—Partial optimization metaheuristic under special intensification conditions. In Essays and Surveys in Metaheuristics; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2002; pp. 613–629. [Google Scholar]

- Ayachi Amar, C.; Bouanane, K.; Aiadi, O. Learning Different Separations in Branch and Cut: A Survey. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Systems and Pattern Recognition, Budva, Montenegro, 9–11 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 214–226. [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian, A.; Uchoa, E.; Ochi, L. A hybrid algorithm for the vehicle routing problem with simultaneous pickup and delivery. Comput. Oper. Res. 2013, 40, 1050–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, R.J. Simple statistical gradient-following algorithms for connectionist reinforcement learning. Mach. Learn. 1992, 8, 229–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uchoa, E.; Pecin, D.; Pessoa, A.; Poggi, M.; Vidal, T.; Subramanian, A. New benchmark instances for the capacitated vehicle routing problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 257, 845–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instance | LKH3 [14] | AM [21] | POMO [22] | SPORL-AM | SPORL-POMO | SPORL-LKH3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-n303-k21 | 2.27 | 28.91 | 18.25 | 6.25 | 7.12 | 5.01 |

| X-n308-k13 | 0.86 | 39.32 | 45.48 | 12.89 | 16.61 | 2.83 |

| X-n313-k71 | 7.03 | 176.05 | 57.07 | 5.24 | 9.14 | 6.64 |

| X-n317-k53 | 8.74 | 186.84 | 73.48 | 8.41 | 9.85 | 4.85 |

| X-n322-k28 | 0.43 | 66.75 | 57.45 | 7.48 | 8.42 | 5.44 |

| X-n327-k20 | 4.33 | 678.42 | 301.48 | 9.12 | 7.45 | 6.63 |

| X-n331-k15 | 1.29 | 823.16 | 153.48 | 10.84 | 6.45 | 4.82 |

| X-n336-k84 | 0.80 | 71.49 | 84.95 | 5.78 | 7.58 | 2.73 |

| X-n344-k43 | 2.28 | 399.86 | 48.24 | 9.21 | 9.65 | 4.82 |

| X-n351-k40 | 4.70 | 94.47 | 147.28 | 7.58 | 7.95 | 5.74 |

| X-n359-k29 | 1.40 | 621.88 | 86.72 | 11.45 | 9.97 | 7.91 |

| X-n367-k17 | 8.90 | 711.52 | 502.87 | 13.47 | 14.25 | 9.57 |

| X-n376-k94 | 1.40 | 188.74 | 80.25 | 8.24 | 8.92 | 7.51 |

| X-n384-k52 | 5.60 | 30.47 | 59.71 | 10.47 | 8.64 | 7.52 |

| X-n393-k38 | 4.80 | 66.10 | 30.70 | 9.58 | 9.73 | 7.34 |

| X-n401-k29 | 1.76 | 20.63 | 34.77 | 20.63 | 10.77 | 9.73 |

| X-n411-k19 | 2.21 | 58.24 | 89.54 | 19.24 | 13.24 | 8.14 |

| X-n420-k130 | 1.91 | 42.10 | 48.50 | 5.78 | 4.85 | 4.24 |

| X-n429-k61 | 2.60 | 65.12 | 73.40 | 12.36 | 8.74 | 4.37 |

| X-n439-k37 | 5.66 | 55.85 | 81.25 | 14.58 | 9.77 | 8.64 |

| X-n449-k29 | 3.70 | 52.38 | 80.74 | 12.40 | 13.74 | 9.24 |

| X-n459-k26 | 5.02 | 29.80 | 67.85 | 13.80 | 11.85 | 9.54 |

| X-n469-k138 | 0.74 | 85.54 | 64.12 | 4.25 | 8.47 | 7.51 |

| X-n480-k70 | 3.26 | 440.64 | 89.42 | 9.74 | 10.71 | 15.58 |

| X-n491-k59 | - | 88.42 | 327.15 | 8.97 | 8.12 | 9.54 |

| X-n502-k39 | - | 410.83 | 772.65 | 11.54 | 9.98 | 10.41 |

| X-n513-k21 | - | 791.83 | 524.78 | 10.89 | 11.86 | 11.75 |

| X-n524-k153 | - | 201.05 | 120.95 | 5.96 | 7.82 | 6.24 |

| X-n536-k96 | - | 85.91 | 15.32 | 10.48 | 15.32 | 7.15 |

| X-n548-k50 | - | 479.21 | 130.81 | 8.25 | 6.47 | 7.14 |

| X-n561-k42 | - | 917.54 | 842.37 | 6.12 | 7.48 | 9.27 |

| X-n573-k30 | - | 234.28 | 425.12 | 12.41 | 11.32 | 10.97 |

| X-n586-k159 | - | 155.88 | 98.42 | 8.24 | 6.14 | 13.08 |

| X-n599-k92 | - | 36.62 | 59.18 | 7.25 | 10.45 | 9.12 |

| X-n613-k62 | - | 86.12 | 124.48 | 14.82 | 15.48 | 13.50 |

| X-n627-k43 | - | 624.64 | 325.49 | 20.16 | 20.47 | 16.48 |

| X-n641-k35 | - | 70.86 | 430.12 | 17.86 | 19.47 | 12.27 |

| X-n655-k131 | - | 179.86 | 283.67 | 13.48 | 16.48 | 10.65 |

| X-n670-k130 | - | 202.12 | 152.96 | 17.56 | 18.01 | 16.48 |

| X-n685-k75 | - | 52.45 | 184.28 | 13.57 | 10.95 | 9.95 |

| Average | 3.40 | 241.29 | 179.86 | 10.91 | 10.74 | 8.50 |

| Instance | AM [21] | POMO [22] | SPORL-AM | SPORL-POMO | SPORL-LKH3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-n701-k44 | 432.03 | 419.62 | 17.02 | 16.58 | 11.77 |

| X-n716-k35 | 30.02 | 116.67 | 20.30 | 18.23 | 14.19 |

| X-n733-k159 | 297.96 | 437.21 | 15.44 | 17.23 | 16.84 |

| X-n749-k98 | 70.83 | 53.22 | 14.23 | 15.42 | 21.34 |

| X-n766-k71 | 423.98 | 464.65 | 20.01 | 19.45 | 16.84 |

| X-n783-k48 | 50.32 | 27.11 | 10.05 | 12.04 | 21.77 |

| X-n801-k40 | 977.09 | 829.38 | 16.40 | 14.32 | 27.23 |

| X-n819-k171 | 49.26 | 174.11 | 22.10 | 20.14 | 12.80 |

| X-n837-k142 | 272.51 | 198.39 | 22.61 | 20.43 | 20.35 |

| X-n856-k95 | 582.17 | 684.60 | 18.75 | 17.35 | 23.47 |

| X-n876-k59 | 24.73 | 45.51 | 25.94 | 25.68 | 24.99 |

| X-n895-k37 | 263.25 | 724.37 | 23.62 | 24.12 | 35.76 |

| X-n916-k207 | 249.15 | 200.09 | 32.64 | 31.89 | 11.33 |

| X-n936-k151 | 318.02 | 143.33 | 32.12 | 32.01 | 13.70 |

| X-n957-k87 | 80.82 | 714.06 | 20.08 | 30.45 | 17.39 |

| X-n979-k58 | 81.14 | 139.66 | 20.07 | 30.24 | 19.35 |

| X-n1001-k43 | 1033.88 | 699.56 | 39.29 | 38.41 | 31.39 |

| Average | 308.06 | 357.14 | 21.80 | 22.58 | 20.03 |

| Instance | LKH3 [14] | AM [21] | POMO [22] | SPORL-AM | SPORL-POMO | SPORL-LKH3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-n303-k21 | 15 (h) | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.49 | 0.23 | 0.45 |

| X-n308-k13 | 18 (h) | 0.62 | 1.02 | 0.56 | 0.37 | 1.02 |

| X-n313-k71 | 18 (h) | 0.77 | 0.83 | 0.64 | 0.75 | 1.42 |

| X-n317-k53 | 19 (h) | 0.88 | 0.92 | 0.68 | 0.81 | 1.98 |

| X-n322-k28 | 20 (h) | 0.54 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 0.68 | 1.36 |

| X-n327-k20 | 20 (h) | 0.82 | 0.65 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 2.06 |

| X-n331-k15 | 18 (h) | 0.97 | 0.89 | 0.43 | 0.38 | 1.06 |

| X-n336-k84 | 20 (h) | 0.80 | 0.94 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 1.04 |

| X-n344-k43 | 22 (h) | 0.92 | 0.81 | 0.73 | 0.80 | 1.72 |

| X-n351-k40 | 21 (h) | 0.60 | 0.74 | 0.69 | 0.49 | 1.02 |

| X-n359-k29 | 19 (h) | 1.03 | 1.02 | 0.83 | 0.95 | 1.87 |

| X-n367-k17 | 17 (h) | 1.03 | 1.20 | 0.64 | 0.71 | 2.07 |

| X-n376-k94 | 23 (h) | 1.00 | 1.03 | 0.63 | 0.68 | 0.98 |

| X-n384-k52 | 19 (h) | 0.99 | 1.05 | 0.73 | 0.82 | 0.85 |

| X-n393-k38 | 19 (h) | 1.14 | 1.30 | 1.02 | 1.15 | 1.05 |

| X-n401-k29 | 16 (h) | 0.64 | 0.79 | 1.17 | 1.04 | 1.04 |

| X-n411-k19 | 17 (h) | 0.90 | 0.89 | 1.13 | 1.10 | 1.35 |

| X-n420-k130 | 24 (h) | 1.20 | 0.97 | 1.24 | 1.19 | 1.23 |

| X-n429-k61 | 22 (h) | 0.70 | 0.82 | 1.01 | 1.00 | 0.73 |

| X-n439-k37 | 21 (h) | 0.93 | 1.02 | 1.06 | 1.11 | 1.68 |

| X-n449-k29 | 25 (h) | 0.73 | 0.80 | 1.14 | 1.19 | 1.48 |

| X-n459-k26 | 26 (h) | 0.71 | 0.95 | 1.16 | 1.03 | 1.56 |

| X-n469-k138 | 30 (h) | 1.00 | 0.99 | 1.21 | 1.41 | 1.38 |

| X-n480-k70 | 31 (h) | 1.27 | 1.30 | 1.19 | 1.16 | 1.85 |

| X-n491-k59 | - | 1.17 | 1.20 | 1.23 | 1.21 | 1.23 |

| X-n502-k39 | - | 1.31 | 1.24 | 1.14 | 1.09 | 1.82 |

| X-n513-k21 | - | 1.11 | 1.15 | 1.13 | 1.23 | 1.42 |

| X-n524-k153 | - | 1.16 | 1.07 | 1.17 | 1.17 | 0.82 |

| X-n536-k96 | - | 1.02 | 1.06 | 1.09 | 1.12 | 1.09 |

| X-n548-k50 | - | 1.35 | 1.24 | 1.19 | 1.09 | 1.62 |

| X-n561-k42 | - | 1.47 | 1.50 | 1.03 | 1.18 | 1.58 |

| X-n573-k30 | - | 1.35 | 1.42 | 1.26 | 1.23 | 1.90 |

| X-n586-k159 | - | 1.46 | 1.28 | 1.13 | 1.24 | 1.68 |

| X-n599-k92 | - | 1.01 | 1.06 | 1.41 | 1.20 | 1.84 |

| X-n613-k62 | - | 1.02 | 1.10 | 1.32 | 1.35 | 1.42 |

| X-n627-k43 | - | 1.65 | 1.80 | 1.27 | 1.30 | 1.78 |

| X-n641-k35 | - | 1.61 | 1.50 | 1.15 | 1.07 | 1.83 |

| X-n655-k131 | - | 1.55 | 1.08 | 1.22 | 1.29 | 1.05 |

| X-n670-k130 | - | 1.67 | 1.42 | 1.17 | 1.24 | 1.31 |

| X-n685-k75 | - | 1.03 | 1.04 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 1.13 |

| Average | 20.83 (h) | 1.04 | 1.05 | 0.97 | 0.98 | 1.93 |

| Instance | AM [21] | POMO [22] | SPORL-AM | SPORL-POMO | SPORL-LKH3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-n701-k44 | 1.78 | 1.68 | 1.98 | 1.47 | 2.07 |

| X-n716-k35 | 1.03 | 1.22 | 2.00 | 1.89 | 2.01 |

| X-n733-k159 | 1.44 | 1.85 | 2.01 | 2.03 | 1.04 |

| X-n749-k98 | 1.19 | 1.82 | 1.98 | 1.99 | 2.16 |

| X-n766-k71 | 1.92 | 1.64 | 1.65 | 1.53 | 2.98 |

| X-n783-k48 | 1.21 | 1.07 | 1.89 | 1.87 | 2.57 |

| X-n801-k40 | 2.10 | 1.65 | 2.03 | 1.52 | 2.84 |

| X-n819-k171 | 1.47 | 1.86 | 2.07 | 2.01 | 1.32 |

| X-n837-k142 | 2.81 | 1.97 | 2.14 | 2.18 | 1.14 |

| X-n856-k95 | 1.94 | 2.01 | 2.06 | 2.10 | 3.06 |

| X-n876-k59 | 1.43 | 1.47 | 2.84 | 2.65 | 3.01 |

| X-n895-k37 | 1.41 | 2.03 | 3.01 | 2.98 | 3.36 |

| X-n916-k207 | 2.36 | 2.14 | 3.45 | 3.49 | 3.53 |

| X-n936-k151 | 2.14 | 2.07 | 4.04 | 3.98 | 3.65 |

| X-n957-k87 | 2.47 | 1.98 | 4.15 | 4.20 | 4.02 |

| X-n979-k58 | 1.58 | 2.04 | 5.02 | 5.08 | 4.01 |

| X-n1001-k43 | 2.81 | 2.23 | 5.13 | 5.20 | 5.53 |

| Average | 1.82 | 1.80 | 2.79 | 2.84 | 2.71 |

| Benchmarks | Gap (%) | Time (s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With | Without | With | Without | |

| 8.50 | 10.12 | 1.39 | 1.07 | |

| 20.03 | 41.07 | 2.84 | 1.20 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ayachi Amar, C.; Bouanane, K.; Aiadi, O. A Reinforcement Learning Framework for Scalable Partitioning and Optimization of Large-Scale Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problems. Electronics 2025, 14, 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193879

Ayachi Amar C, Bouanane K, Aiadi O. A Reinforcement Learning Framework for Scalable Partitioning and Optimization of Large-Scale Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problems. Electronics. 2025; 14(19):3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193879

Chicago/Turabian StyleAyachi Amar, Chaima, Khadra Bouanane, and Oussama Aiadi. 2025. "A Reinforcement Learning Framework for Scalable Partitioning and Optimization of Large-Scale Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problems" Electronics 14, no. 19: 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193879

APA StyleAyachi Amar, C., Bouanane, K., & Aiadi, O. (2025). A Reinforcement Learning Framework for Scalable Partitioning and Optimization of Large-Scale Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problems. Electronics, 14(19), 3879. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14193879