Abstract

This study explores the usability and interaction experience of preschool-aged children with the Artsteps platform, a web-based tool for creating and navigating virtual exhibitions. The goal is to assess the platform’s suitability for early childhood learners and to reflect on its potential educational value. Following a child-centered design methodology, the research involves the participation of 35 children aged 4–6 in classroom-based activities. Observational methods and an adapted version of the System Usability Scale (SUS) for young learners were used to collect quantitative and qualitative data. The analysis focuses on interaction patterns, the comprehension of basic functions, and emotional responses during the use of the platform. Findings offer exploratory insights into the affordances and limitations of the platform in preschool settings, offering insights into how such digital tools may support digital literacy and experiential learning in early childhood education.

1. Introduction

Digital technology has become a dominant element in children’s daily lives, with the use of touchscreen devices becoming increasingly widespread, even among children under 5 years old [1,2,3]. This trend has led to the development of a wide variety of educational applications and digital tools aimed at young learners [4,5]. However, the extensive use of mobile learning at such early ages has sparked significant debate regarding the suitability of content for young children and has caused concern among parents [6,7]. There is a recognized need for more attention in this area and an absence of sufficient evaluation tools is highlighted [8,9,10].

Despite the estimated number of 80,000 applications labeled as “educational” on the market [1,4], there is widespread consensus among researchers that the majority of these applications lack true educational value and are often not based on scientific research. This makes selecting high-quality applications a difficult challenge for caregivers and educators. Existing evaluation tools, for the most part, are not considered adequate to help educators and parents properly and easily evaluate the pedagogical potential of applications [6,7]. Some are considered outdated, while others have “limited dimensions”. Consequently, there is a strong need for effective evaluation tools.

Within the broader context of digital media in education, Web 2.0 tools stand out for their ease of use, potential for interaction and collaboration, and support for content creation and sharing. Research has shown that using Web 2.0 tools can have a positive impact on students’ academic performance and attitudes [8]. One application of Web 2.0 tools is the creation of virtual environments, such as virtual museums or virtual exhibitions, which have gained a significant place in education. The platform Artsteps is one such web-based tool that allows for the design of virtual exhibitions or museums [10].

Virtual museums offer an effective teaching environment, leveraging three-dimensional and interactive technology. They provide an alternative approach to the traditional classroom model and can transform passive visitors into active explorers. They have been shown to positively affect variables such as academic performance, motivation, higher-order thinking skills, and student participation. Their use extends to various educational levels, including primary education [3,6,7].

In preschool education, the integration of digital technology, especially in artistic education, can support the development of creativity, active participation, and digital literacy. Virtual spaces, such as those that can be created with Artsteps, have already been explored for their potential in arts education [3,10].

Despite the recognized potential of virtual environments, their suitability and accessibility for very young learners, such as preschool-aged children, require further investigation. It is crucial to understand how children of this age interact with such platforms and what their usability experience is. This understanding can guide the selection and design of digital tools that can truly support digital literacy and experiential learning in early childhood education.

The current study aims to address this gap by exploring the usability and interaction experience of preschool-aged children with the Artsteps platform. Through classroom-based activities involving the participation of 35 children aged 4–6, and using observational methods and an adapted version of the System Usability Scale (SUS) for young learners, this research seeks to assess the platform’s suitability for this age group [11]. The analysis focuses on interaction patterns, the comprehension of basic functions, and emotional responses, aiming to reveal the affordances and limitations of the Artsteps platform in preschool settings and offer insights into the role of such digital tools in early childhood education.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the background and related work in the domain of early childhood education and digital technologies. Section 3 introduces the Artsteps platform and its educational affordances. Section 4 outlines the research objectives and the guiding research questions. Section 5 describes the methodological framework, including the research design, participants, and data collection techniques. Section 6 reports the findings of the study, including both quantitative and qualitative data. Section 7 discusses key insights, implications, and areas for improvement. Finally, Section 8 concludes the article by summarizing the main contributions and outlining directions for future research.

2. Related Work

Early childhood education is widely recognized as a crucial stage in a child’s development, laying the foundation for cognitive, social, and emotional skill acquisition [12,13]. In modern preschool settings, Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) are adopted to support constructive, goal-oriented, and reflective learning experiences [13]. However, designing digital tools for young learners requires attentiveness to their limited reading abilities, fine motor control, and attention spans, thus prioritizing child-friendly interfaces, multimodal feedback, and guided navigation [14,15].

A number of evaluation frameworks have been proposed to guide educators and parents in selecting effective educational applications. Papadakis [1] systematically reviewed mobile learning app evaluations for preschoolers, finding that most existing rubrics and checklists are outdated and lack robust usability criteria. This gap emphasizes the need for contemporary, reliable assessment instruments specifically tailored to early learners.

Regarding the design and development of preschool-focused digital tools, Idris et al. [5] introduced the M-Kids mobile learning application, using thematic qualitative analysis of stakeholder feedback to refine multimedia elements (text, visuals, and audio) for young users. Similarly, Pan and Cheng [4] developed a web-based interactive system for preschool art education, demonstrating how shared digital platforms can facilitate the co-construction of content and enhance pedagogical engagement.

Beyond standalone apps, Web 2.0 technologies offer a spectrum of affordances for social collaboration, content creation, and knowledge sharing. Arslan [8] categorizes these tools into social communities (e.g., Facebook), content-sharing platforms (e.g., YouTube), and content-editing environments (e.g., Google Docs), highlighting their potential across educational contexts and age groups.

Virtual museum and immersive learning environments exemplify the innovative application of Web 2.0 principles. Cruz and Torres [10] explored Artsteps in a professional development program for in-service teachers, where participants designed 3D virtual exhibitions on socially relevant themes. The study reported increased engagement and willingness to integrate virtual exhibitions into curricula, suggesting promising implications for younger, preschool-aged audiences.

Finally, immersive, game-based approaches have been applied to specialized domains such as cybersecurity education. Karakos et al. [7] developed a virtual reality-based curriculum for children aged 10+, finding that immersive interactions enhance user engagement and learning retention. Although targeting older children, these findings offer methodological insights for adapting immersive systems to preschool learners.

3. Artsteps Platform

Artsteps is a web-based platform designed for the creation and exploration of virtual 3D exhibitions. Its user-friendly interface and accessibility via standard web browsers without additional software requirements make it an appealing tool for both educators and learners. Artsteps allows users to design custom exhibition spaces, embedding multimedia content such as images, texts, audio, video, and external web links. These features enable the development of interactive, narrative-rich environments suitable for a wide range of educational purposes.

Originally intended for artists and cultural organizations to showcase digital galleries, Artsteps has found increasing use in educational contexts. The platform supports the construction of immersive learning environments where learners can navigate, observe, and interact with digital artifacts, fostering both engagement and experiential learning. Exhibitions may include two-dimensional elements like posters and photographs, or three-dimensional components such as virtual installations and embedded videos, thereby promoting multisensory interaction.

In a recent exploratory study by Cruz and Torres [16], Artsteps was employed in a professional development program for thirty-five in-service teachers in Portugal. The training aimed to promote digital teacher empowerment through the use of Virtual and Immersive Learning Environments (VILEs). Teachers were introduced to Artsteps and tasked with designing virtual exhibitions relevant to their subject domains. The study reported that the majority of participants had little or no prior experience with immersive technologies. Nevertheless, all participants succeeded in creating their own 3D galleries and expressed strong interest in integrating such tools into their teaching practice. Importantly, the study highlighted Artsteps’ capacity to stimulate active learning, encourage student engagement, and support curricular integration through innovative pedagogical approaches.

The positive reception of Artsteps by educators, as well as its capacity to facilitate content-rich, customizable, and interactive virtual spaces, underscores its potential as a platform for educational applications—particularly in early childhood education where visual and exploratory stimuli play a crucial role.

4. Research Objectives and Questions

The overarching objective of this study is to evaluate the usability and interaction experience of preschool-aged children with the Artsteps platform—a web-based tool for creating and exploring virtual exhibitions. Recognizing the growing presence of digital environments in early childhood education, this study investigates how such platforms align with the cognitive, perceptual, and motor capabilities of young learners. The aim is not only to assess functional usability but to also explore how engaging, accessible, and pedagogically meaningful the experience is for this specific population.

Adopting a child-centered approach, the study employs both behavioral observation and adapted usability assessment tools to evaluate user experience. A further goal is to identify opportunities for tailoring digital environments in ways that foster the development of digital literacy skills in early education contexts.

The investigation is guided by the following research questions:

- RQ1: How do preschool children interact with the Artsteps platform in classroom settings?

- RQ2: What are the main challenges or difficulties children encounter while navigating the platform?

- RQ3: To what extent do children understand the basic functions of the platform and exhibit autonomous navigation?

- RQ4: How do children emotionally and behaviorally experience the use of Artsteps during classroom activities?

- RQ5: In what ways could the platform be adapted or enhanced to better suit the developmental needs of preschool-aged users?

- RQ6: Does the use of Artsteps contribute to the educational process in early childhood classrooms?

- RQ7: Are there observable behaviors indicating the emergence of digital literacy skills during the interaction?

These questions provide the foundation for the study’s mixed-method research design, supporting the generation of insights that may inform pedagogical strategies and the inclusive design of interactive digital tools tailored to young learners.

5. Proposed Methodology

This study adopts an action research methodology, grounded in a real-world educational setting—a public kindergarten in Kefalonia, Greece—spanning the academic years 2023–2024 and 2024–2025. A total of 35 preschool-aged children, between 4 and 6 years old, participated in the research, which aimed to explore the usability and interaction experience of the Artsteps platform in early childhood education. The study was designed to assess not only the functional aspects of the platform but also its pedagogical value and emotional resonance within this age group.

5.1. Study Context

The methodological framework is informed by the principles of participatory and experiential learning. Both the educator and the students were treated as co-researchers, engaging actively in the design, implementation, and reflection phases of the research. Children were not merely passive users but active participants in the creation of a virtual exhibition titled Digital Children’s Book Museum. Through this initiative, they contributed to the thematic planning, curatorial decisions, and content development, thereby engaging with digital tools in a meaningful, developmentally appropriate way. The project thus had as dual function as both a learning intervention and an evaluative environment, allowing for the integration of digital literacy development within early childhood pedagogy, as suggested by Mertler [17].

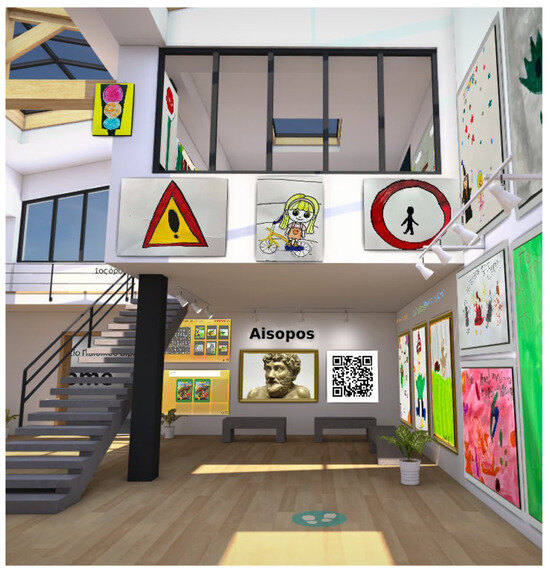

The virtual museum was composed of five thematic rooms that combined educational and creative objectives (see Figure 1). These included the following: (1) a storytelling space where children authored and narrated their own fairy tales; (2) a reading promotion area linked to World Children’s Book Day; (3) interactive modules featuring digital educational content and e-books; (4) a traffic safety simulation room designed for role-playing activities; and (5) a virtual AI space where children’s drawings were animated using the Animated Drawings tool developed by Meta AI Research. These thematic zones supported different forms of cognitive and emotional engagement while promoting multimodal interaction with digital content.

Figure 1.

Artsteps’ screenshot during experiments.

5.2. Data Collection

Prior to the study sessions, we collected informal background data from teachers and parents regarding each child’s familiarity with digital technologies. Most participants had regular access to touchscreen devices (e.g., tablets or smartphones) and were accustomed to using educational or entertainment apps. However, none of the children had prior exposure to the Artsteps platform, while individual digital fluency may have varied slightly, the overall group was considered moderately homogeneous in terms of prior digital experience. During the study, consistent guidance and scaffolding were provided to all participants to minimize any performance disparities arising from familiarity differences.

To accommodate the developmental stage of preschool-aged participants, we adapted the System Usability Scale (SUS) following guidelines from Vlachogianni and Tselios [11]. The standard Likert items were reworded in simplified, child-friendly language and presented orally alongside a three-point smiley-face scale as follows: positive, neutral, and negative. Children pointed to the face that best represented their experience, and responses were numerically coded as 5, 3, and 1, respectively. The ten items used are listed in Table 1 below. The scale addressed various dimensions including enjoyment, comprehension, autonomy, emotional response, and interface design. To evaluate internal consistency, we calculated Cronbach’s alpha, which yielded a reliability score of a = 0.82, indicating good internal reliability for the adapted scale.

Table 1.

Mean response ratings by gender and age group.

To evaluate usability, a modified version of the System Usability Scale (SUS) was used, adapted to the developmental stage of the participants. The original Likert-scale responses were replaced with intuitive visual icons—smiley faces representing positive, neutral, and negative experiences—allowing children to self-report their perceptions in a comprehensible manner. The adapted SUS instrument evaluated key usability dimensions such as ease of navigation, comprehension of features, degree of autonomy, and emotional responses during interaction, aligning with the approach proposed by Vlachogianni and Tselios. Responses were collected and analyzed through the KwikSurveys platform to provide quantitative insights.

In addition to the structured instrument, qualitative data were gathered through systematic field observations. The educators recorded behavioral cues, verbal and non-verbal expressions, and interaction patterns observed during classroom activities involving the Artsteps platform. Children’s digital artifacts, including virtual exhibits and animated stories, were also subjected to thematic content analysis to identify emerging patterns related to digital agency, interaction fluency, and storytelling strategies.

The analytical approach integrated both quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Quantitative data from the SUS questionnaire provided statistical measures of the usability and satisfaction, while qualitative observations enriched the understanding of user behavior and platform affordances. This mixed-methods design ensured the triangulation of findings and increased the internal validity of the study.

In addition to the quantitative responses, qualitative data were collected through in situ observation notes and audio-recorded child utterances during interaction sessions. These data were analyzed using an inductive thematic analysis approach. Two researchers independently reviewed the material, generating open codes based on recurring expressions, behaviors, and emotional indicators (e.g., “I love this”, “I’m confused”, jumping, clapping, or facial expressions). Initial codes were then grouped into broader themes such as positive emotional engagement, confusion or frustration, and autonomy or dependence on adult help. Inter-rater agreement was discussed to ensure consistency, and selected quotes were included in the results to illustrate representative patterns, while the data are not statistically generalizable, they provide rich insights into the user experience and emotional resonance of the platform.

5.3. Data Analysis

Moreover, this research introduces a number of pedagogical and technological innovations situated at the intersection of human–computer interaction and early childhood education. One of the most significant contributions is the implementation of a child-led co-creation model, where children directly influenced the aesthetic and narrative construction of the virtual museum. This process enhanced their sense of ownership, agency, and creative confidence. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence through animation of children’s drawings offered a unique blend of analog and digital creative expression, enriching both the cognitive and emotional dimensions of their learning experience.

To supplement the usability ratings, we analyzed the interaction logs and observation notes to identify behavioral trends during task performance. On average, children required 3–5 min to complete core navigation and object placement tasks. Approximately 65% of participants initiated basic exploration (e.g., movement and camera rotation) without prompting, while 35% needed initial verbal guidance. The most common hesitation points involved navigating multi-level menus, with 40% of children pausing or asking for help when selecting 3D objects to place.

Children demonstrated greater fluency in tasks with immediate visual feedback (e.g., placing or moving objects) and showed prolonged engagement when the task involved personalization. Tasks involving multiple sequential steps (e.g., choosing → placing → renaming) were more error-prone. Autonomy increased with age, as older children (5–6 years) were more likely to complete the full sequence without intervention. The frequency of help requests was higher in the Reading Room zone, which had fewer direct visual cues, while the Animated AI zone prompted more spontaneous trial-and-error interaction. The use of interdisciplinary and experiential environments—such as the traffic safety room and AI-enabled art space—offered new pathways for narrative-driven, cross-curricular learning. These immersive settings allowed children to explore themes ranging from civic awareness to digital creativity in a developmentally appropriate and emotionally engaging manner. Overall, the study aims to contribute empirical data and pedagogical insights for the future design of inclusive and developmentally sensitive digital learning platforms for early childhood education [18].

5.4. Ethical Considerations and Limitations

Finally, regarding the limitations of the project, it is important to note that the present study was conducted with a relatively small sample of 35 preschool-aged children. While this size is consistent with similar exploratory studies in early childhood HCI contexts, it inherently limits the statistical power of inferential analyses. For this reason, we employed descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) and qualitative thematic observations rather than performing t-tests or ANOVAs. The aim was to identify indicative trends and user behaviors, not to produce generalizable conclusions. The findings should therefore be interpreted as exploratory in nature, serving to generate hypotheses and guide future research with larger and more diverse participant groups.

6. Expected Results

The preliminary data collected from the usability questionnaire administered to 35 preschool children is anticipated to yield meaningful insights into the user experience associated with the Artsteps virtual exhibition platform in early childhood education. The questionnaire was specifically adapted to assess five core dimensions of usability from the perspective of young learners as follows: (1) enjoyment and engagement, (2) ease of navigation and comprehension, (3) degree of autonomy, (4) emotional response, and (5) intention for future use. These dimensions are expected to provide a holistic understanding of how preschool-aged children perceive and interact with immersive digital environments (see Table 1 and Table 2).

Table 2.

Detailed analysis by questionnaire items.

6.1. Quantitative Findings

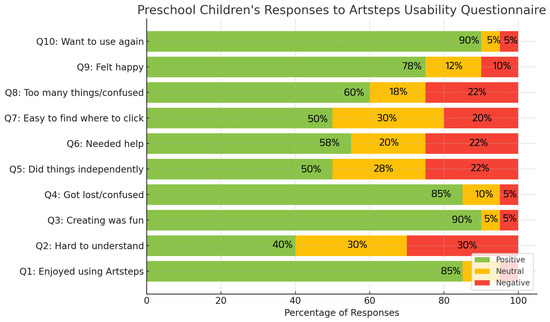

The following Figure 2 presents the distribution of answers using a stacked bar format, which facilitates a clear comparison between positive, neutral, and negative reactions across all items. As shown, the majority of children reported positive responses across most usability items. Notably, over 85% expressed enjoyment, and 90% indicated they would like to use the platform again. However, around 40% of children reported some difficulty understanding how to navigate the interface, suggesting that while the platform is engaging, its complexity may pose a barrier for younger users. These mixed patterns reflect both the motivational potential and the cognitive challenges of immersive digital environments for preschool learners.

Figure 2.

Distribution of preschool children’s responses to the Artsteps usability questionnaire (n = 35), with percentage values shown for each response type (positive, neutral, and negative) across ten usability dimensions.

Initial trends suggest that the majority of participating children respond positively to the platform, with approximately 85% reporting high enjoyment and 90% expressing interest in engaging with the platform again. These indicators underscore the motivational potential of Artsteps and support its application as a stimulating educational medium. However, a closer examination reveals that around 40% of the children experience difficulties in understanding the interface, indicating that cognitive load and visual complexity may hinder independent use, especially among younger or less digitally experienced users.

It is expected that 50% of participants will report being able to perform basic tasks without adult assistance, while the remainder will require varying degrees of support. This finding may point to developmental differences in cognitive and motor skills among the 4–6-year-old demographic, which must be considered when designing interfaces for early learners.

6.2. Qualitative Insights

Moreover, the qualitative data—derived from spontaneous verbal comments—are expected to reflect the children’s imaginative engagement with the virtual environment. Early observations include remarks such as “It’s awesome, it’s not like Minecraft” and “The books have buttons that make sounds”, suggesting that children are not only interacting with the content but are actively interpreting and constructing narratives around their digital experiences.

Further analysis, disaggregated by gender and age group, will likely reveal additional patterns. For instance, older children (ages 5–6) are expected to demonstrate higher levels of independence, comprehension, and overall satisfaction compared to younger peers (ages 4–5). Gender-related trends may also emerge, with girls generally reporting fewer difficulties and higher affective engagement than boys, particularly in the younger subgroup.

From an emotional perspective, approximately 75% of the children are likely to report positive affective states—such as happiness and curiosity—while using Artsteps. Given that emotional engagement is strongly associated with sustained attention and learning outcomes in early education, this result is especially promising.

In light of these findings, we expect to formulate specific design recommendations to enhance the ergonomic and pedagogical alignment of the Artsteps platform with the developmental needs of preschool users. These may include the following: (i) simplification of navigational structure, (ii) integration of intuitive icons and auditory cues, and (iii) inclusion of scaffolding mechanisms to support independent exploration.

6.3. Engagement Across Thematic Zones

Overall, the anticipated outcomes of this study aim to inform both technology developers and educators on best practices for integrating digital platforms into early childhood education. By grounding interface design in empirical data and child-centered evaluation, this work contributes to the ongoing discourse on age-appropriate digital literacy and interactive learning environments.

Finally, regarding comparative engagement across thematic zones, observational data and qualitative responses suggest differential levels of engagement across the three thematic zones of the exhibition. The Animated AI zone elicited the strongest emotional reactions, including laughter, verbal commentary, and spontaneous gestures (e.g., pointing, dancing), indicating a high degree of immersive stimulation. The Children’s Creations zone also generated strong interest, particularly when children recognized their own work, expressing pride and initiating peer discussions. Conversely, the Reading Room zone, which featured more static visuals and relied on audio-narrated text, resulted in comparatively subdued reactions, especially among younger participants with limited narrative comprehension. These patterns highlight how the modality and interactivity of content may shape children’s levels of emotional and cognitive engagement.

7. Discussion

The responses gathered from the kindergarten participants provide valuable insights into the usability, emotional engagement, and educational potential of integrating digital platforms such as Artsteps in early childhood education. The data reveal both the strengths and limitations of the platform from the perspective of preschool users, offering guidance for its refinement and more effective pedagogical implementation.

7.1. Quantitative Interpretation

Quantitatively, the study found that a substantial majority of the children responded positively to their interaction with the platform. Specifically, 85% of the participants reported that they enjoyed using Artsteps, while 90% expressed a clear desire to use it again. This aligns with the rationale of Section 1 and Section 2 on the educational affordances of virtual exhibitions.

Despite these encouraging indicators, several usability challenges were also identified. Approximately 40% of the children indicated that they found the platform somewhat difficult to understand, citing confusion arising from the number of features and navigational complexity. This finding highlights the cognitive load associated with interacting with interfaces originally designed for older users or general audiences, while 50% of the children successfully navigated and completed tasks independently, the other half required adult support, suggesting that scaffolding is essential, especially during initial interactions. These observations align with established principles in child–computer interaction research, which emphasize the need for simplicity, visual cues, and multimodal feedback to accommodate developmental limitations in literacy and attention span.

7.2. Emotional and Qualitative Insights

The emotional responses of the participants further reinforce the platform’s viability in early educational contexts. A notable 75% of children reported feeling happy while using Artsteps. Emotional engagement is a critical component of effective learning in early childhood, influencing both short-term motivation and long-term retention. The positive affective experiences reported here are indicative of a user-centered digital interaction that resonates with children’s emotional and cognitive expectations.

Beyond numerical data, qualitative insights derived from the children’s spontaneous verbal expressions during the activity offered further depth. These utterances, rich in imagination and metaphor, reflect the extent to which the children internalized and personalized the virtual experience. Representative comments included the following:

“It’s awesome, it’s not like Minecraft", “Who will be checking the tickets on the computer?”, “It has many rooms, large corridors", “The books inside are made of glass", “The books have buttons on them that make sounds", “Lots of rooms, lots of doors", “How does the museum lock?”, “It has wires", “It has glass things", “Glass walls", “It will have a triangular roof like the Polytechnic", “In the museum we learn things", and “It has a map so we can find our way”.

These reflections indicate a high level of immersion and cognitive investment. The children’s descriptions demonstrate their ability to project real-world knowledge onto virtual spaces, effectively engaging in symbolic thinking and narrative construction. Such imaginative interpretations affirm the potential of virtual museum environments to cultivate creativity, spatial awareness, and exploratory learning—skills highly valued in early education.

7.3. Design Implications

Overall, the results suggest that while Artsteps holds considerable promise as an educational platform for preschool children, further adaptations are required to optimize its accessibility and developmental appropriateness. Interface simplification, multimodal interaction support, and teacher-mediated facilitation are key areas for improvement. Nonetheless, the study affirms the critical role that thoughtfully designed digital experiences can play in early childhood education by supporting emotional engagement, digital literacy, and creative exploration. One of the key usability challenges identified was the visual complexity of the interface, particularly for younger users who had difficulty parsing multiple icons and panels. While adult scaffolding helped mitigate this issue, it highlights the need for interface simplification in future iterations. Design adaptations such as progressive disclosure of options, larger buttons, simplified menus, and context-aware audio prompts could reduce cognitive load and support more autonomous navigation. These strategies are well aligned with child-centered design principles and findings in early HCI literature.

7.4. Limitations and Future Work

The study offers valuable insights into the interaction patterns and usability perceptions of preschool-aged children in immersive digital environments. Following the initial submission, the sample was expanded to 35 participants, which strengthens the descriptive robustness of the findings. Nonetheless, the study remains exploratory in nature, and its conclusions should be interpreted within the context of a still limited and context-specific sample. Our intent is not to generalize across all preschool learners, but to highlight salient patterns that merit further validation. While the current study highlights positive short-term engagement outcomes—particularly among older girls—it does not assess whether this emotional connection translates into long-term digital literacy development. Future research should adopt a longitudinal design, incorporating repeated measures over time to track changes in skills such as spatial navigation, multimodal comprehension, and independent digital exploration. Including pre-/post-testing and retention intervals would allow for a more robust understanding of how early interactive experiences shape foundational digital competencies.

The comparative analysis of the three thematic zones underscores the importance of content modality in designing engaging experiences for early learners. Animated, interactive, and personally relevant content—such as AI characters or self-made exhibits—appears to foster greater emotional and behavioral engagement than static, text-oriented environments. This finding is particularly relevant when designing for non-readers or children with limited narrative processing skills. Furthermore, the interaction-level analysis suggests that immediate visual feedback and low cognitive load are crucial factors supporting autonomy in preschool interfaces. Tasks involving sequential choices or abstract symbols posed greater difficulty, aligning with developmental expectations for this age group. These findings underscore the importance of minimizing navigation depth and incorporating redundant visual cues when designing for non-readers.

Future research with larger and demographically diverse cohorts—as well as longitudinal and experimental designs—will be crucial in verifying the developmental appropriateness and pedagogical value of virtual exhibition platforms like Artsteps. While general digital familiarity was relatively balanced across participants, future studies could benefit from including a formal digital literacy assessment to better control for baseline experience and its impact on interaction outcomes. Emerging research in child-centered systems employing real-time tracking and machine learning, demonstrates how sensor data and adaptive feedback loops can be used to dynamically tailor user interfaces to children’s moment-to-moment behaviors and emotional states [19]. While our current study did not include such technologies, future iterations could benefit from integrating gaze-, gesture-, or speech-based cues to improve accessibility and engagement for diverse user profiles.

8. Conclusions

The preliminary findings of this study underscore the critical importance of integrating digital literacy education within pre-primary curricula. As societies become increasingly shaped by digital technologies, early childhood education must evolve to equip learners with the competencies and dispositions necessary to navigate and participate meaningfully in this emerging landscape. These findings reinforce our earlier point in Section 1 that virtual exhibition tools can foster digital literacy and experiential learning in early childhood.

The empirical evidence gathered in this study suggests that preschool-aged children, when supported by appropriate scaffolding strategies, are not only capable of engaging meaningfully with virtual exhibition environments, but they also derive enjoyment, agency, and a sense of accomplishment from these experiences. As shown in Section 6, 85% of children reported enjoyment and 90% intended to reuse the platform—underscoring its motivational potential.

Nonetheless, the study also brings to light several limitations in the current design of the platform that constrain its accessibility for very young users. In particular, issues related to interface complexity, non-intuitive navigation, and the absence of auditory scaffolding present substantial barriers to autonomous use. To enhance pedagogical effectiveness and broaden accessibility, future iterations of such platforms should consider the design priorities and recommendations appear in Section 7.

In addition to design improvements, future research should extend the scope and depth of inquiry in several directions. First, studies involving larger and more heterogeneous participant samples are needed to improve generalizability and account for variation across socio-cultural contexts. Second, the role of collaborative engagement within shared virtual spaces warrants further exploration, particularly in relation to social-emotional learning and peer interaction. Third, longitudinal designs may offer insights into how sustained exposure to digital platforms like Artsteps impacts the development of narrative competence, spatial reasoning, and foundational digital literacy skills over time. Finally, attention should be given to demographic factors—such as age, gender, and baseline digital familiarity—that may mediate user experience and learning outcomes. Future work will also involve a controlled usability redesign study, in which the current Artsteps interface will be compared to an adapted version optimized for preschool users. The redesigned version will feature simplified UI layouts and integrated audio-based guidance, aiming to increase accessibility and reduce interface-induced confusion. Usability outcomes will be compared across age groups using both quantitative and qualitative measures, further validating and refining the design recommendations derived from the current exploratory findings.

In conclusion, this study contributes to a growing body of literature that supports the integration of immersive digital environments into early childhood education. While challenges remain in ensuring accessibility and pedagogical appropriateness, the findings reaffirm the transformative potential of virtual exhibition platforms when thoughtfully designed and contextually embedded within age-appropriate learning frameworks.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, G.T. and M.K.; methodology, G.T., M.K. and G.H.; software, G.T.; validation, G.T. and M.K.; formal analysis, G.T., M.K. and G.H.; investigation, G.T. and M.K.; data curation, G.T. and M.K.; writing—original draft preparation, G.T. and M.K.; writing—review and editing, M.K. and G.H.; visualization, M.K. and G.T.; supervision, G.H. and M.K.; project administration, M.K.; funding acquisition, M.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| ICT | Information and Communication Technologies |

| HCI | Human–Computer Interaction |

| UX | User Experience |

| SUS | System Usability Scale |

| VILE | Virtual and Immersive Learning Environment |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

| UI | User Interface |

| KPI | Key Performance Indicator |

| 4Cs | Critical Thinking, Communication, Collaboration, and Creativity |

References

- Papadakis, S. Tools for evaluating educational apps for young children: A systematic review of the literature. Interact. Technol. Smart Educ. 2021, 18, 18–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolak, J.; Norgate, S.H.; Monaghan, P.; Taylor, G. Developing evaluation tools for assessing the educational potential of apps for preschool children in the UK. J. Child. Media 2021, 15, 410–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakis, M.; Lykiardopoulou, A.; Lykiardopoulou, E.; Tasiouli, G.; Heliades, G. An exploratory study of mobile-based scenarios for foreign language teaching in early childhood. Educ. Sci. 2022, 12, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, R.; Cheng, J. Design and Application of the Digital-Oriented Interactive System for Teaching Preschool Art Education. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1242038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idris, W.I.S.; Razak, R.A.; Rahman, S.S.B.A. The Design and Development of Mobile Learning for Preschool Education. JuKu J. Kurikulum Pengajaran Asia Pasifik 2021, 9, 37–48. [Google Scholar]

- Şeyihoğlu, A.; Kartal, A.; Vekli, G.S.; Tekbıyık, A.; Konur, K.B. Design of Online Digital Disaster Training Program for Pre-Service Teachers. J. Learn. Teach. Digit. Age 2024, 9, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakos, D.; Maneta, G.; Rantos, K.; Drosatos, G.; Karakos, A. Enhancing Information Security Education for Children: A Game-Based Approach Using Immersive Technologies. In Proceedings of the Hellenic Scientific Association of Information and Communication Technologies in Education, Kavala, Greece, 29 September–1 October 2023; pp. 221–226. [Google Scholar]

- Arslan, K.; Arı, A.G. Online science teaching supported by Web 2.0 tool: Virtual museum event. J. Hum. Soc. Sci. 2021, 4, 285–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.K.; Li, D. Pre-service art teachers’ perspectives on building virtual art gallery exhibitions. Int. J. Arts Educ. 2021, 19, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Kayaalp, F.; Namlı, Z.B.; Meral, E. My museum: A study of pre-service social studies teachers’ experience in designing virtual museums. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2024, 29, 24047–24085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlachogianni, P.; Tselios, N. Perceived usability evaluation of educational technology using the System Usability Scale (SUS): A systematic review. J. Res. Technol. Educ. 2022, 54, 392–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konstantakis, M. From physical to digital classroom using digital storytelling and serious games to increase children’s participation: An interactive lesson plan through Padlet web tool. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Open and Distance Education, Athens, Greece, 2 November 2022 2022; Volume 11, pp. 21–32. [Google Scholar]

- Ralli, A.M.; Kazali, E.; Kanellou, M.; Mouzaki, A.; Antoniou, F.; Diamanti, V.; Papaioannou, S. Oral language and story retelling during preschool and primary school years: Developmental patterns and interrelationships. J. Psycholinguist. Res. 2021, 50, 949–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulju, P.; Mäkinen, M. Phonological strategies and peer scaffolding in digital literacy game-playing sessions in a Finnish pre-primary class. J. Early Child. Lit. 2021, 21, 338–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sticca, F.; Brauchli, V.; Lannen, P. Screen on= development off? A systematic scoping review and a developmental psychology perspective on the effects of screen time on early childhood development. Front. Dev. Psychol. 2025, 2, 1439040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, S.; Torres, A. Virtual and Immersive Learning Environments Using ArtSteps: Exploratory Study with Teachers. In Proceedings of the International Association for Development of the Information, Lisbon, Portugal, 19 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mertler, C.A. Action Research: Improving Schools and Empowering Educators; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Buchan, M.C.; Bhawra, J.; Katapally, T.R. Navigating the digital world: Development of an evidence-based digital literacy program and assessment tool for youth. Smart Learn. Environ. 2024, 11, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zendehdel, N.; Leu, M.C.; Yin, Z. A gaze-driven manufacturing assembly assistant system with integrated step recognition, repetition analysis, and real-time feedback. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 144, 110076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).