Ontology-Driven Architecture for Managing Environmental, Social, and Governance Metrics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background and Literature

2.1. Challenges in ESG Solutions

2.2. Role of Ontologies in ESG

3. Development Methodology

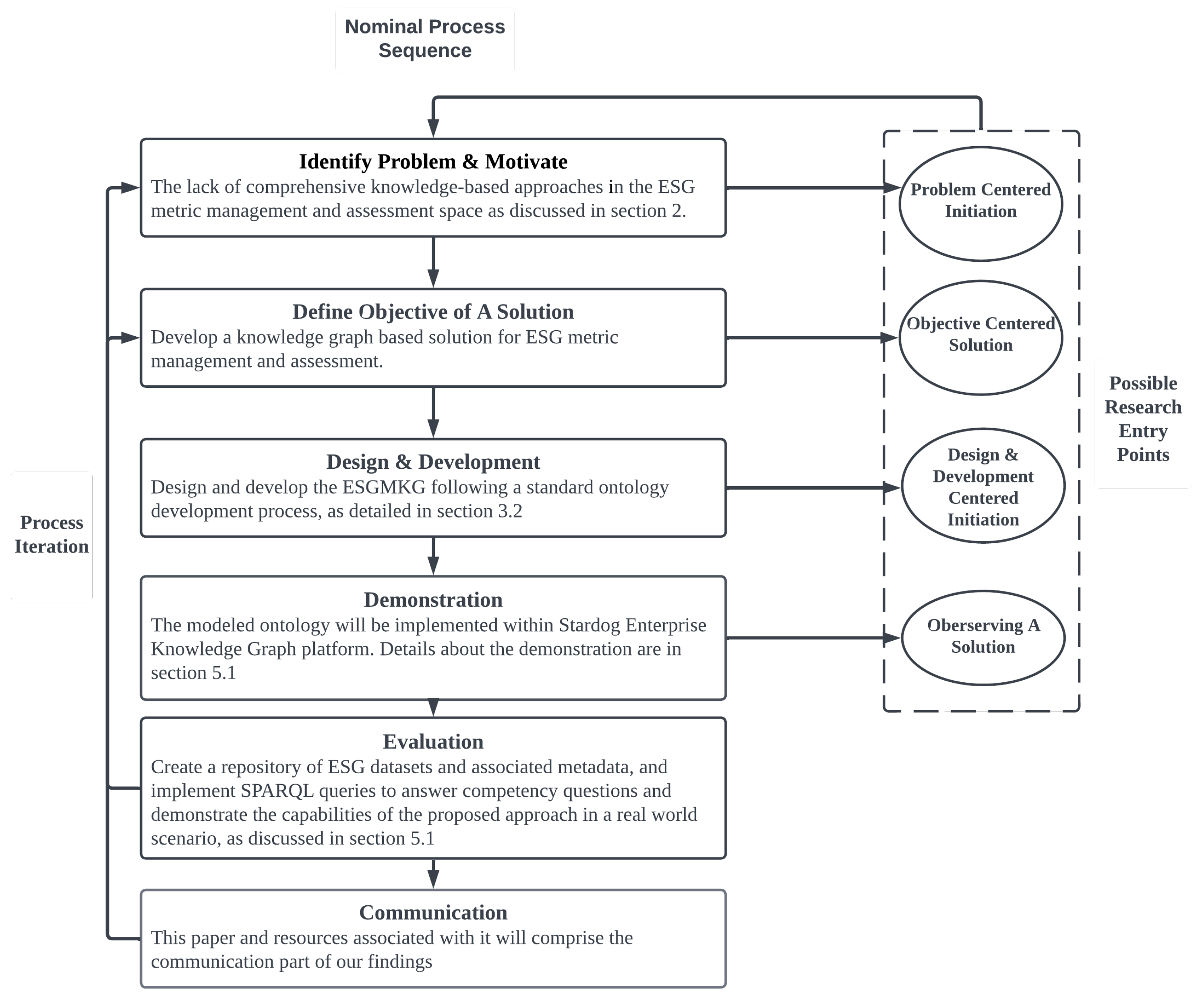

3.1. Research Methodology

3.2. Ontology Development

3.3. Ontology Validation

4. Proposed Architecture and Ontology

4.1. Architecture Overview

- Graphical user interface (GUI) layer: This layer is tailored to meet the needs of key system user roles, namely those of chief sustainability officer, investor, and regulator. Each user role interacts with the system differently, with the Chief Sustainability Officer focusing on reporting, the investor on portfolio management, and the regulator on monitoring. This design ensures that the system provides relevant functionalities and information to each user type, facilitating the efficient and effective use of the ESG metric management system.

- Service layer: Within the system development life cycle, this layer encompasses three main services: the ESG framework categorisation service, the ESG metric modelling service, and the ESG data collection service. Each service is designed to handle a specific aspect of ESG data processing, ensuring that the system is modular, scalable, and capable of evolving to meet future needs. Organisations can implement these services, as web services or microservices following a technology that suits their overall technical architecture. For example, an ESG data collection service can be implemented by an organisation as a discrete entity that can access specific data sources and feed data into an ESG metric modelling service that calculates metrics based on requests from the GUI layer, as guided by ESGMKG.

- ESGMKG ontology data management platform layer: this layer provides a number of modules to manage the ESGMKG that will be discussed in Section 4.2. The data governance module ensures adherence to data governance principles. Other modules handle critical factors such as authentication and security to ensure that the system is robust and secure.

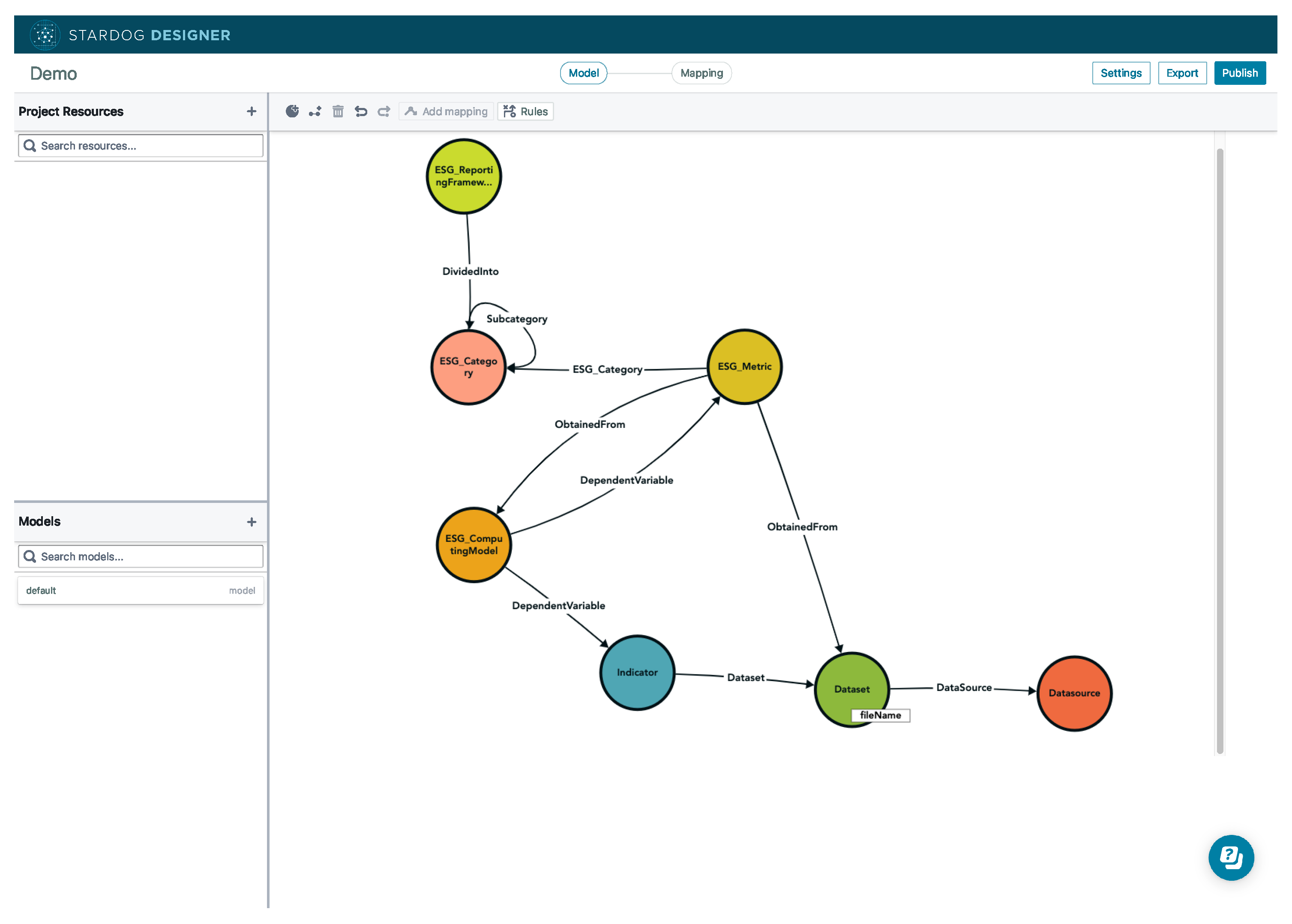

4.2. ESGMKG Design

- Enhanced querying and search capabilities: providing more nuanced and context-aware search results by understanding the semantic relationships between ESG reporting framework categories and metrics.

- Improved ESG data connectivity and contextualisation: creating a web of ESG reporting metrics where connections between disparate reporting requirements add context and depth to data analysis.

- ESG knowledge discovery and insight generation: facilitating the discovery of ESG reporting metrics and their hidden patterns, relationships, and insights through the interconnected nature of the graph.

- Decision support: offering a foundational layer for advanced decision-making tools and AI applications, such as recommendation systems, by providing rich, interconnected ESG data.

- ESG Data interoperability and sharing: promoting ESG data reuse and sharing across organisational, domain, and technical boundaries through a common, understandable framework.

- ESG reporting personalisation and customisation: tailoring content, recommendations, and interactions to sustainable investment users or scenarios based on the rich understanding of corporations’ preferences, performance, and industry and region context provided by the knowledge graph.

4.3. ESGMKG Integration

5. Demonstration and Evaluation

5.1. ESGMKG Instantiation

5.2. Usage Scenarios and Competency Questions

5.3. Linked Data Implementation

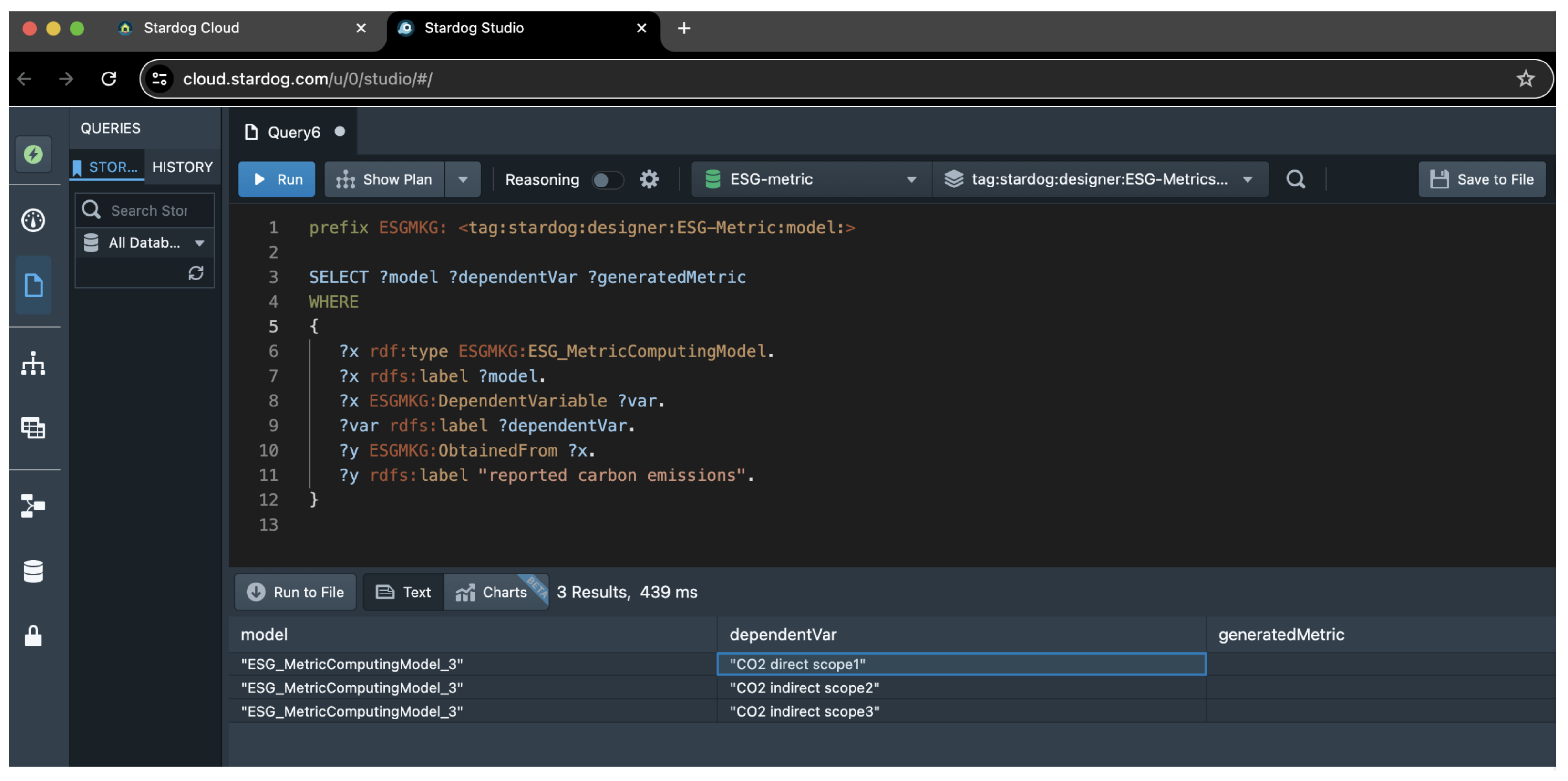

5.4. Querying the Implementation

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ESG | Environmental, Social, and Governance |

| ESGMKG | ESG Metric Knowledge Graph |

| DSR | Design Science Research |

| RDF | Resource Description Framework |

| OWL | Web Ontology Language |

| SPARQL | SPARQL Protocol and RDF Query Language |

| IFRS | International Financial Reporting Standards |

| TCFD | Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures |

| TNFD | Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures |

| SASB | Sustainability Accounting Standards Board |

| APRA | Australian Prudential Regulation Authority |

| CER | Clean Energy Regulator |

| GUI | Graphical User Interface |

| ERM 1 | Environmental Risk Metric 1 |

| MSCI | Morgan Stanley Capital International |

References

- Australian Prudential Regulation Authority. Prudential Practice Guide: Draft CPG 229 Climate Change Financial Risks. 2021. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&source=web&rct=j&opi=89978449&url=https://www.apra.gov.au/sites/default/files/2021-11/Final%2520Prudential%2520Practice%2520Guide%2520CPG%2520229%2520Climate%2520Change%2520Financial%2520Risks.pdf&ved=2ahUKEwitmZq1u9qFAxX8cvUHHZhUAAEQFnoECBMQAQ&usg=AOvVaw2H1HYzEaB49QpQ1eyC1dw_ (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Elkington, J. Cannibals with Forks: The Triple Bottom Line of 21st Century Business. Capstone 1997, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KPMG International. KPMG International Survey of Corporate Responsibility Reporting; KPMG International: Amstelveen, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Flower, J. The International Integrated Reporting Council: A Story of Failure. Crit. Perspect. Account. 2015, 27, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, N. Towards a Comprehensive Climate Change Agreement in Paris; The London School of Economics and Political Science: London, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Capelle-Blancard, G.; Petit, A. Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Performance and Sovereign Bond Spreads: An Empirical Analysis of OECD Countries. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 246, 267–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R.G.; Krzus, M.P. One Report: Integrated Reporting for a Sustainable Strategy; John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010.

- Konys, A. An ontology-based knowledge modelling for a sustainability assessment domain. Sustainability 2018, 10, 300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Cormican, K.; Yu, M. Ontology-based Systems Engineering: A State-of-the-Art Review. Comput. Ind. 2019, 111, 148–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, V.W.B.; Rampasso, I.S.; Anholon, R.; Quelhas, O.L.G.; Leal Filho, W. Knowledge management in the context of sustainability: Literature review and opportunities for future research. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 489–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labuschagnea, C.; Brenta, A.C.; Van Ercka, R.P.G. Assessing the sustainability performances of industries. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP Finance Initiative. Sustainability Metrics: Translation and Impact on Property Investment and Management. Available online: https://www.unepfi.org/fileadmin/documents/UNEPFI_SustainabilityMetrics_Web.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Burritt, R.; Schaltegger, S. Accounting towards sustainability in production and supply chains. Br. Account. Rev. 2014, 46, 327–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haffar, M.; Searcy, C. The use of context-based environmental indicators in corporate reporting. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 192, 496–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, D.; Liu, B.; Chang, M. Carbon Emissions and TCFD Aligned Climate-Related Information Disclosures. J. Bus. Ethics 2023, 182, 967–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.; Joukhadar, J.; Thorogood, A.; Rabhi, F.A. Capabilities for Improving ESG Reporting. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Information Systems (ECIS’2024), Paphos, Cyprus, 13–19 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Lokuwaduge, C.S.D.S.; Heenetigala, K. Integrating environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure for a sustainable development: An Australian study. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 438–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD). ESG Investing: Practices, Progress, and Challenges. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/finance/ESG-Investing-Practices-Progress-Challenges.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Pan, J.Z.; Vetere, G.; Gomez-Perez, J.M.; Wu, H. (Eds.) Exploiting Linked Data and Knowledge Graphs in Large Organisations; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, B.; Cheng, J.; Zhao, X.; Duan, Z. Knowledge graph completion: A review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 192435–192456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fensel, D.; Simsek, U.; Angele, K.; Huaman, E.; Kärle, E.; Panasiuk, O.; Toma, I.; Umbrich, J.; Wahler, A. Knowledge Graphs; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.; Ji, Z.; Li, X.; Yin, L.; Liu, L.; Sun, M.; Liu, Q.; Yang, R. Construction and application of a knowledge graph. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- d’Aquin, M.; Noy, N.F. Where to Publish and Find Ontologies? A Survey of Ontology Libraries. J. Web Semant. 2012, 11, 96–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Protégé Software Page. Available online: https://protege.stanford.edu/software.php (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- BioPortal. Available online: https://bioportal.bioontology.org (accessed on 13 March 2024).

- Peffers, K.; Tuunanen, T.; Rothenberger, M.A.; Chatterjee, S. A Design Science Research Methodology for Information Systems Research. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 2007, 24, 45–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noy, N.F.; McGuinness, D.L. Ontology Development 101: A Guide to Creating Your First Ontology; Stanford Knowledge Systems Laboratory Technical Report KSL-01-05. 2001. Available online: https://corais.org/sites/default/files/ontology_development_101_aguide_to_creating_your_first_ontology.pdf (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Suárez-Figueroa, M.C.; Gómez-Pérez, A.; Fernández-López, M. The NeOn Methodology for Ontology Engineering. In Ontology Engineering in a Networked World; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011; pp. 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Tamašauskaitė, G.; Groth, P. Defining a knowledge graph development process through a systematic review. ACM Trans. Softw. Eng. Methodol. 2023, 32, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRS S1; General Requirements for Disclosure of Sustainability-Related Financial Information. IFRS Foundation: London, UK, 2022; Exposure Draft IFRS Sustainability Disclosure Standard.

- Financial Stability Board. Recommendations of the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures; Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures. 2017. Available online: https://apo.org.au/node/97651 (accessed on 6 March 2024).

- Bezerra, C.; Freitas, F.; Santana, F. Evaluating ontologies with competency questions. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/WIC/ACM International Joint Conferences on Web Intelligence (WI) and Intelligent Agent Technologies (IAT), Atlanta, GA, USA, 17–20 November 2013; Volume 3, pp. 284–285. [Google Scholar]

- CFA Institute. CFA Institute Certificate in ESG Investing: 2023 Course Overview; CFA Institute: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, M. An ESG Metrics Management System for Sustainable Financial System. In Proceedings of the Enterprise Design, Operations, and Computing. EDOC 2023 Workshops, Groningen, The Netherlands, 30 October–3 November 2023; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 343–348. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.M.; Fox, M.S.; Gruninger, M. An Ontology of Quality for Enterprise Modelling. In Proceedings of the 4th IEEE Workshop on Enabling Technologies: Infrastructure for Collaborative Enterprises (WET ICE’95), Berkeley Springs, WV, USA, 20–22 April 1995; pp. 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- NGFS Climate Scenarios Phase 2. Available online: https://www.ngfs.net/sites/default/files/media/2021/08/27/ngfs_climate_scenarios_phase2_june2021.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- UNEP. Increasing Climate Ambition, Decreasing Emissions. Available online: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/increasing-climate-ambition-decreasing-emissions (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- TNFD. The TNFD Nature-Related Risk and Opportunity Management and Disclosure Framework—Beta v0.4 Release. 2023. Available online: https://tnfd.global/publication/tnfd-v0-4-integrated-framework/ (accessed on 25 February 2024).

- W3C RDF Working Group. RDF Semantic Web Standards. 2014. Available online: https://www.w3.org/TR/turtle/ (accessed on 21 March 2024).

- Beckett, D.; Berners-Lee, T.; Prud’hommeaux, E.; Carothers, G. RDF 1.1 Turtle. World Wide Web Consortium. 2014. pp. 18–31. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/70283847.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2024).

| Purpose | Competency Question |

|---|---|

| Exploring the frameworks that apply to an organisation | Which reporting framework applies to a specific company? |

| Understanding the different reporting dimensions in a framework | What are the available metric categories for a specific reporting framework? |

| Discovering which metric can be used for which category | What metrics represent a specific category? |

| Relating a metric to the measurement method behind it | What model is used for calculating a specific metric? |

| Relating a metric to the data used to calculate it | What metric or indicator is involved in calculating a specific metric? |

| Locating the datasets that are used to calculate metrics | What is the dataset used for a specific indicator? |

| Locating the origin of datasets used to calculate metrics | Where is the original data source for an available metric or dataset? |

| ESGMKG Class | Definition |

|---|---|

| ESG_ReportingFramework | A reporting framework that emerges from ESG initiatives, including standards and guidelines such as IFRS S1, TCFD, etc. |

| ESG_Category | Categories recommended by the framework or required by corporations for ESG reporting and compliance. |

| ESG_Metric | Metrics under various ESG categories, also definable by corporations according to their specific needs and goals. |

| ESG_ComputingModel | A mathematical or computing model transforming selected ESG metrics or indicators into a composite metric for a comprehensive view of ESG performance. |

| Indicator | Any data variable usable in the computation of an ESG metric. |

| Dataset | A set of values from a data source usable to compute ESG metrics. |

| Datasource | The origin of an ESG dataset, which can be a primary or secondary source. |

| Competency Questions | Solution |

|---|---|

| 1. Which reporting framework is applicable for this company in Australia? | The applicable reporting framework is IFRS S1 (disclosures can be submitted to the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA)) and TCFD (disclosures can be submitted to Clean Energy Regulator (CER)). |

| 2. What are the available metric categories for the IFRS S1 reporting framework? | They are environmental risk, environmental opportunity, social risk, and governance risk. |

| 3. What metric can be used for measuring impact in the category of environmental risk? | Environmental Risk Metric 1, Environmental Risk Metric 2. |

| 4. What model is used to compute Environmental Risk Metric 1? | ESG MetricComputingModel 1. |

| 5. What inputs Environmental Risk Metric 1 needs to be calculated? | Reported Carbon Emissions, Electricity Purchased Total, Energy Consumed Total, Waste Total, and Water Withdrawal Total are needed for Environmental Risk Metric 1 calculation. |

| 6. What model is used for computing Reported Carbon Emission? | ESG MetricComputingModel 3. |

| 7. What inputs Reported Carbon Emissions needs to be calculated? | CO2 Direct Scope1, CO2 Indirect Scope2, and CO2 Indirect Scope 3 are needed for Reported Carbon Emission calculation. |

| 8. What model is used to compute CO2 Direct Scope 1? | ProxyModel(copy of input). |

| 9. What inputs CO2 Direct Scope 1 needs to be calculated? | CO2DirectScope1. |

| 10. What model is used to compute CO2DirectScope1? | It is a column in ‘esg_raw_data_on_corporations.csv.zip’ dataset. |

| 11. What is the datasource for the dataset ‘esg_raw_data_on_corporations.csv.zip’? | It is obtained from the Eurofidai data source. |

| Subject | Predicate | Object |

| # Instance of Reporting Framework IFRS_S1 | ||

| <ESGMKG:IFRS_S1> | a | <ESGMKG:ESG_ReportingFramework> |

| <ESGMKG:IFRS_S1> | rdfs:label | “IFRS_S1” |

| <ESGMKG:IFRS_S1> | ESGMKG:ReportingBody | “Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA)” |

| <ESGMKG:IFRS_S1> | ESGMKG:DividedInto | <ESGMKG:Environmental_Risk>, <ESGMKG:Environmental_Opportunity>, <ESGMKG:Governance_Risk>, <ESGMKG:Social_Risk> |

|

# Instance of ESG Computing MetricComputingModel 3 | ||

| <ESGMKG:ESG_MetricComputingModel3> | a | <ESGMKG:ESG_ComputingModel> |

| <ESGMKG:ESG_MetricComputingModel3> | rdfs:label | “ESG MetricComputingModel 3” |

| <ESGMKG:ESG_MetricComputingModel3> | ESGMKG:DependentVariable | <ESGMKG:CO2_DirectScope1>, <ESGMKG:CO2_IndirectScope2>, <ESGMKG:CO2_IndirectScope3> |

| <ESGMKG:Reported_Carbon_Emission> | ESGMKG:ObtainedFrom | <ESGMKG:ESG_MetricComputingModel3> |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, M.; Rabhi, F.A.; Bandara, M. Ontology-Driven Architecture for Managing Environmental, Social, and Governance Metrics. Electronics 2024, 13, 1719. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13091719

Yu M, Rabhi FA, Bandara M. Ontology-Driven Architecture for Managing Environmental, Social, and Governance Metrics. Electronics. 2024; 13(9):1719. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13091719

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Mingqin, Fethi A. Rabhi, and Madhushi Bandara. 2024. "Ontology-Driven Architecture for Managing Environmental, Social, and Governance Metrics" Electronics 13, no. 9: 1719. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13091719

APA StyleYu, M., Rabhi, F. A., & Bandara, M. (2024). Ontology-Driven Architecture for Managing Environmental, Social, and Governance Metrics. Electronics, 13(9), 1719. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13091719