Navigating Unstructured Space: Deep Action Learning-Based Obstacle Avoidance System for Indoor Automated Guided Vehicles

Abstract

1. Introduction

- A DAL architecture is employed to perform robust and accurate detection of objects in an indoor environment.

- Object localization is performed using a single monochrome camera fixed to the AGV. An automated navigation capability is realized through the amalgamation of YOLOv4, SURF, and kNN in a seamless DAL architecture.

- The AGV’s self-navigation performance is enhanced by representing obstacles as points or nodes in the AGV mapping system, thereby improving its ability to plan routes around them.

- The experimental outcomes demonstrate that the suggested system performs robustly and meets the requirements of advanced AGV operations.

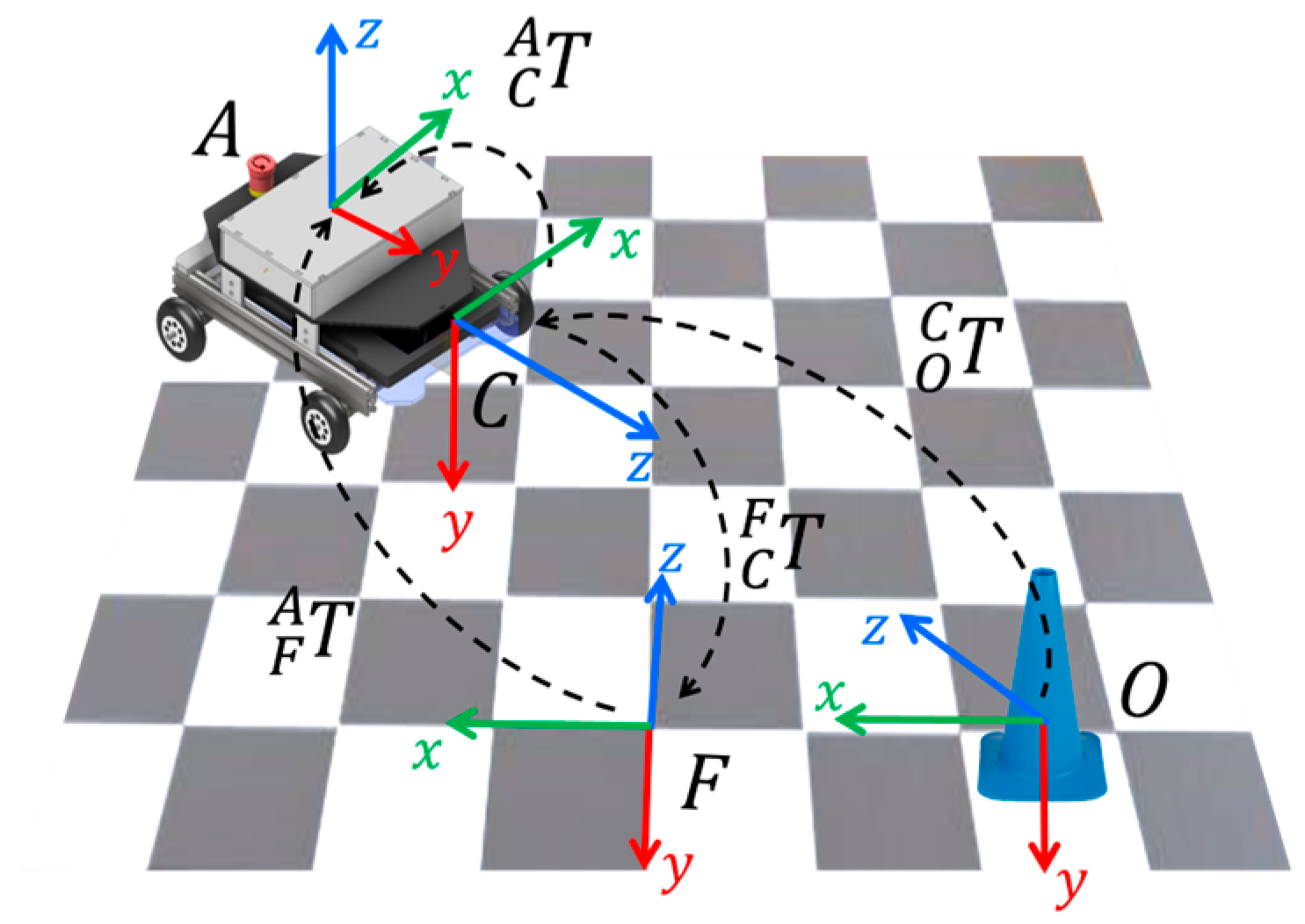

2. System Design

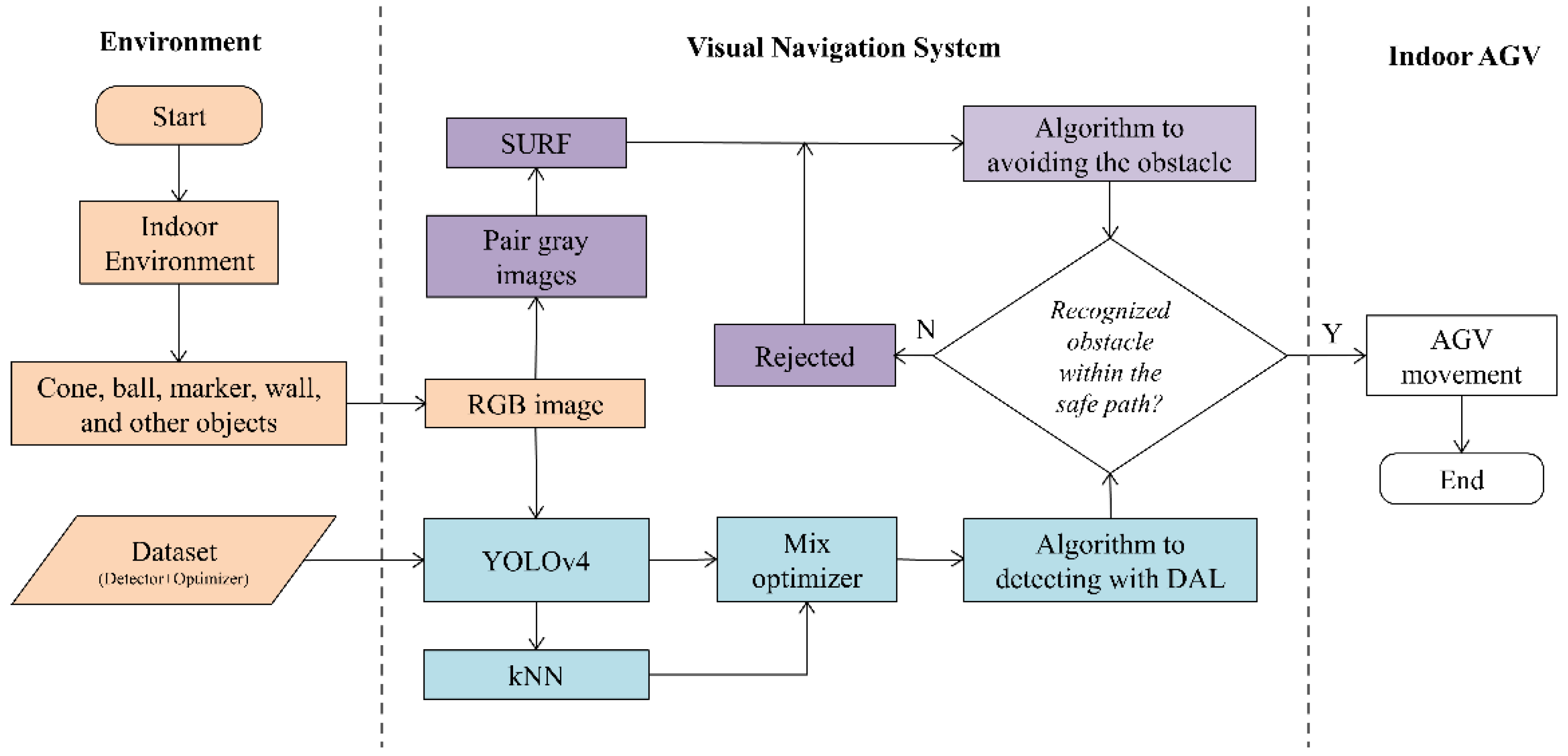

3. AGV with Visual Navigation System

3.1. Visual Navigation

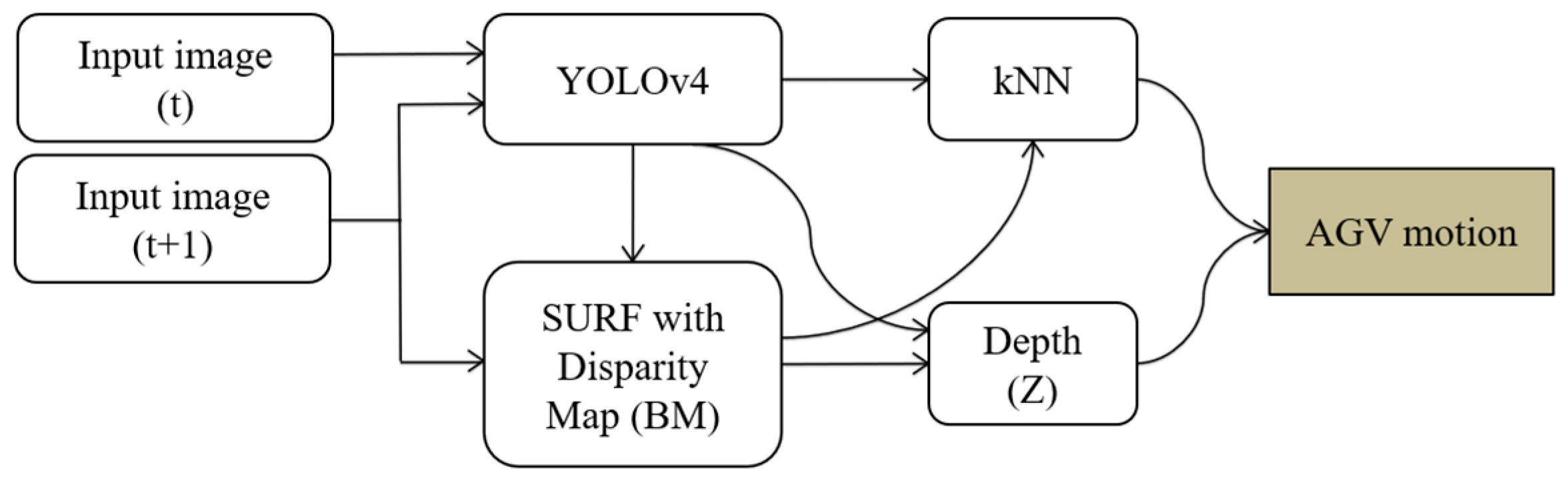

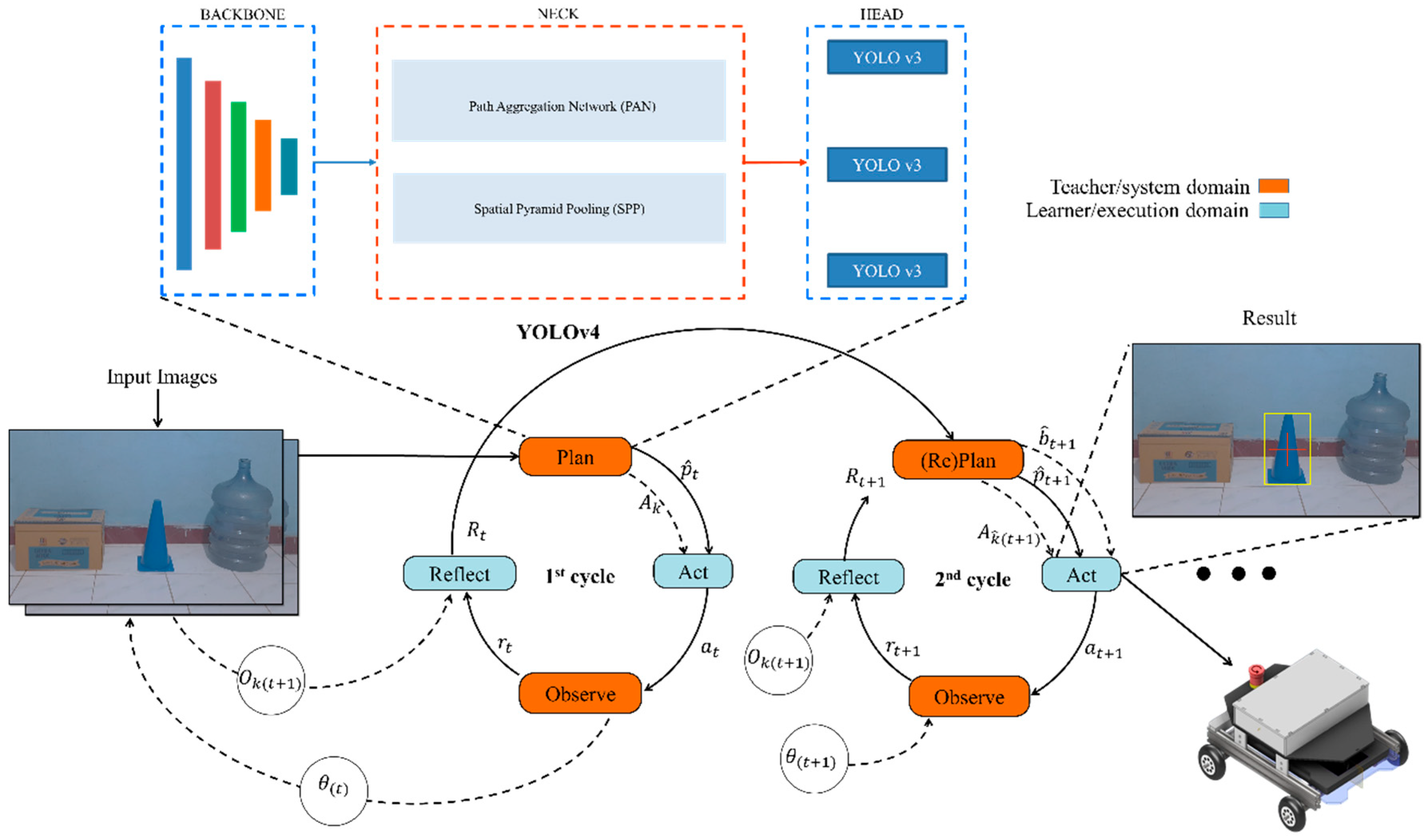

3.2. Indoor AGV with DAL Data-Driven Algorithm

3.3. Deep Action Learning for Obstacle Detection

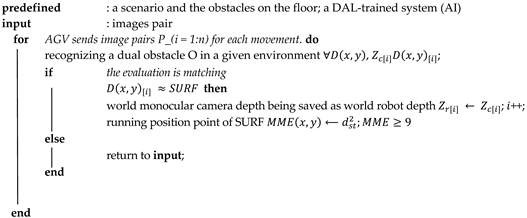

| Algorithm 1 Search Obstacles in Indoor Environment |

|

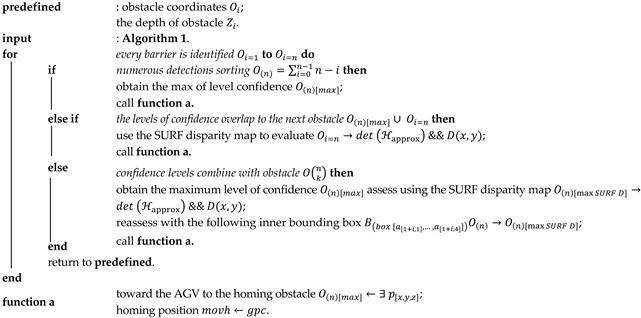

| Algorithm 2 Verification of Obstacle for AGV Step Selection |

|

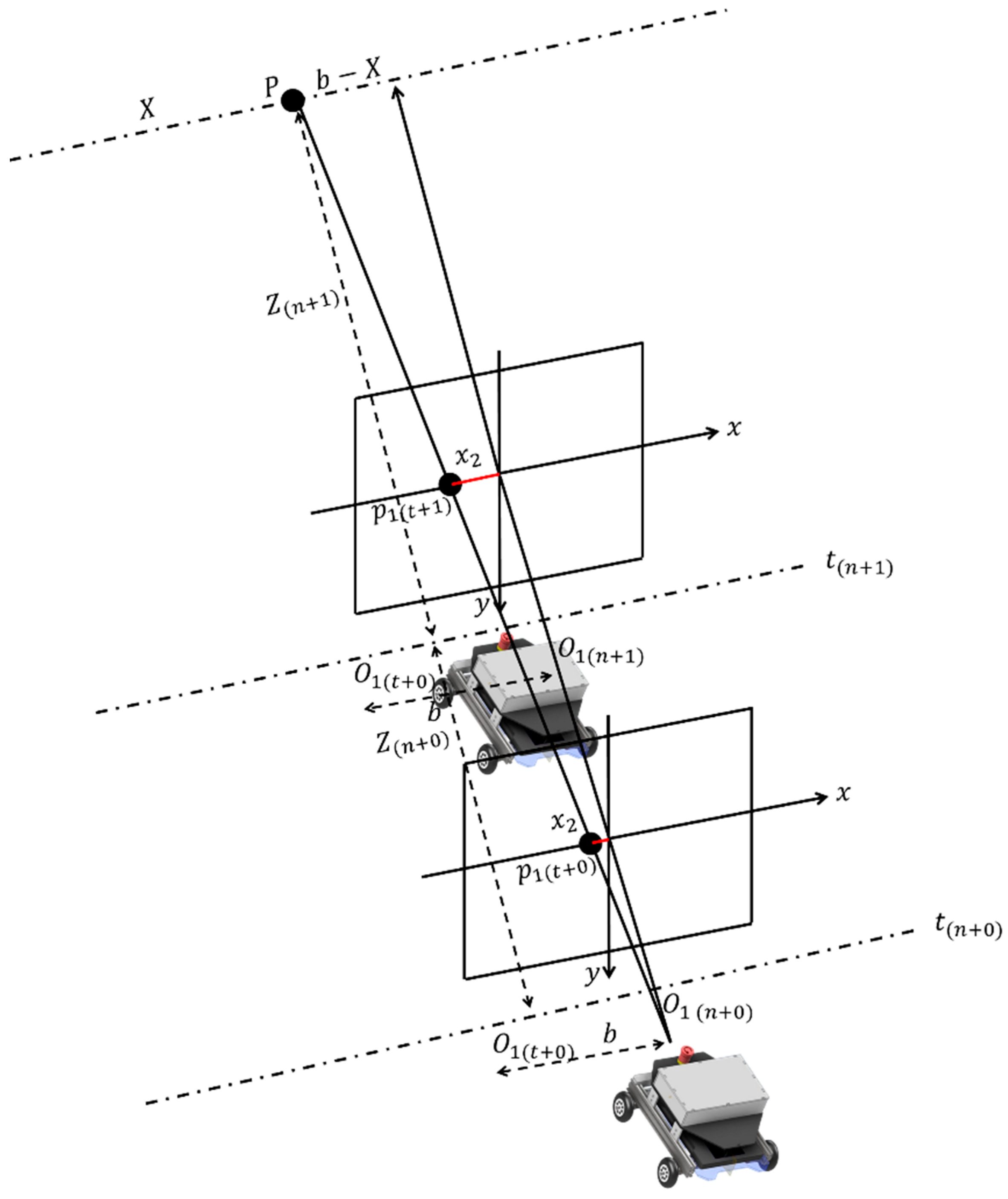

3.3.1. Localization of Recognized Obstacles

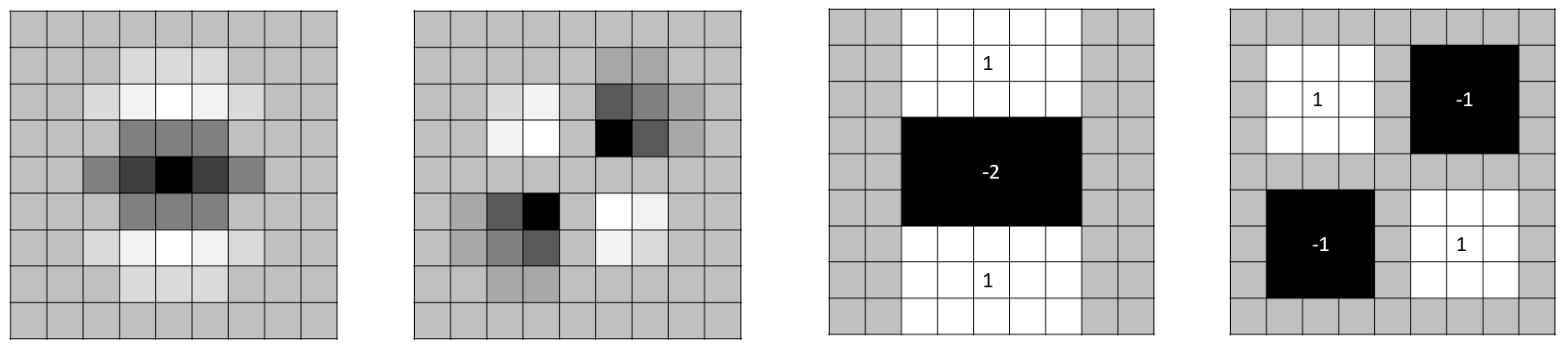

3.3.2. SURF Approach

3.3.3. Verified by kNN

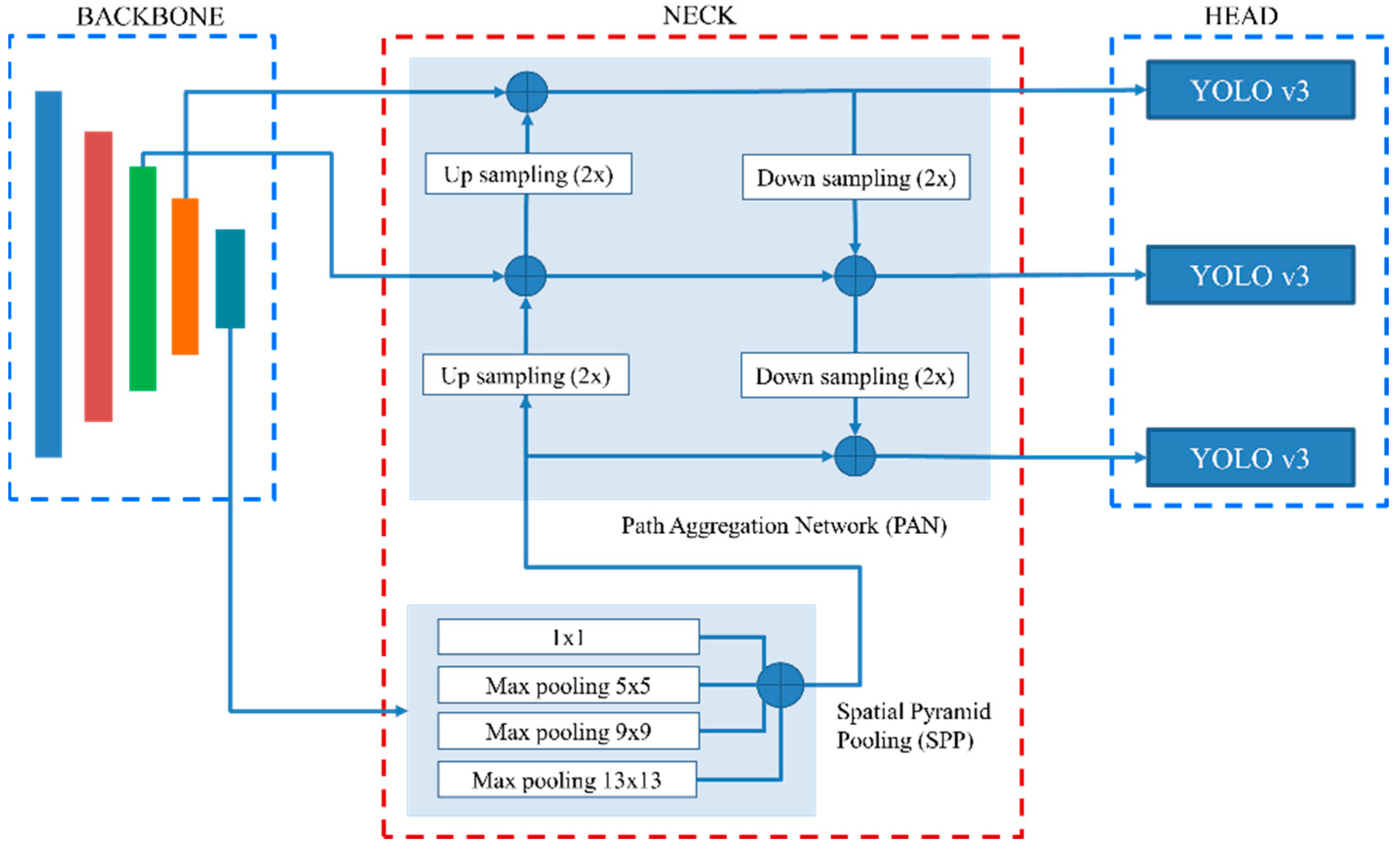

3.3.4. DAL with YOLOv4

4. Visual Navigation Algorithm

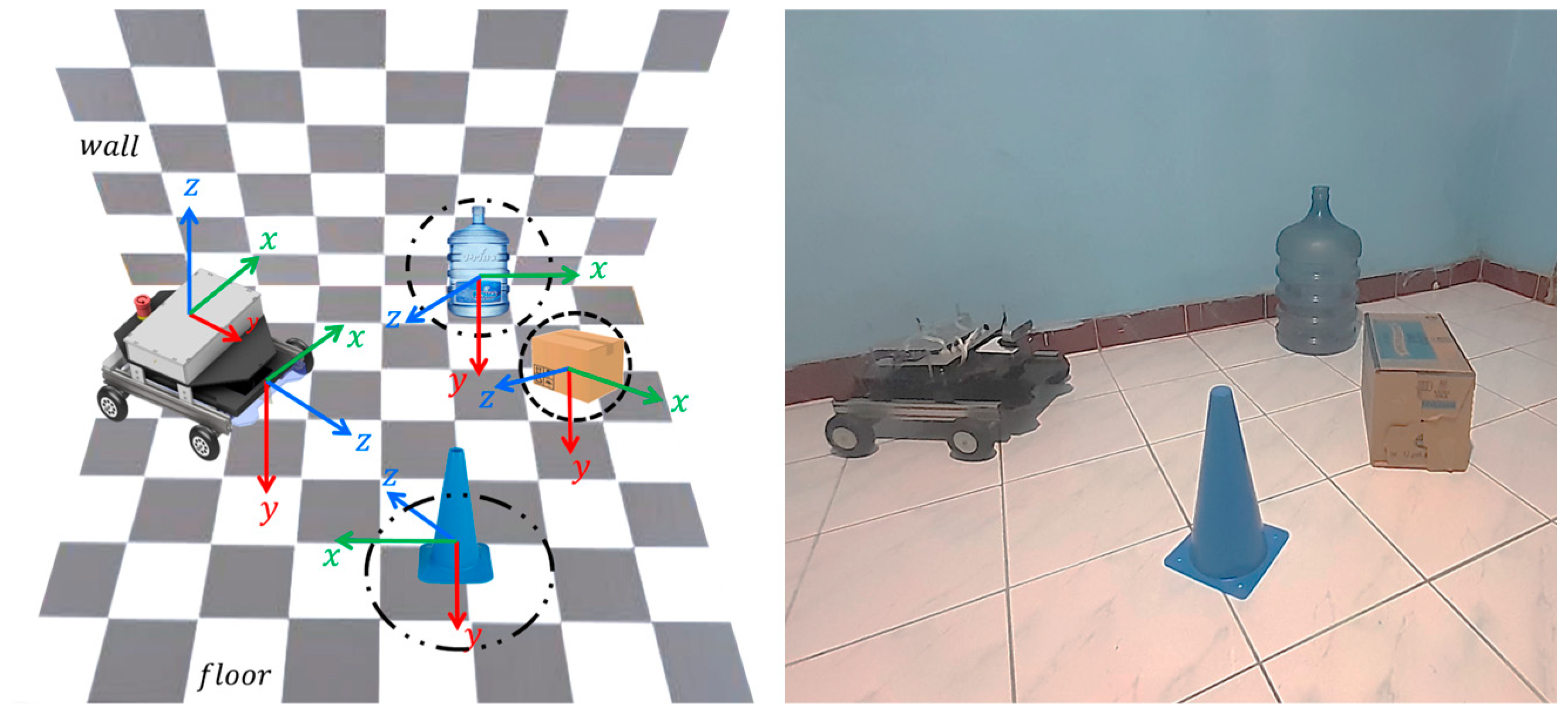

4.1. Obstacles on the Floor

4.2. Avoiding Obstacles

4.2.1. Forward Detection

4.2.2. Decision to Turn

4.2.3. Home Position

5. Experimental Results

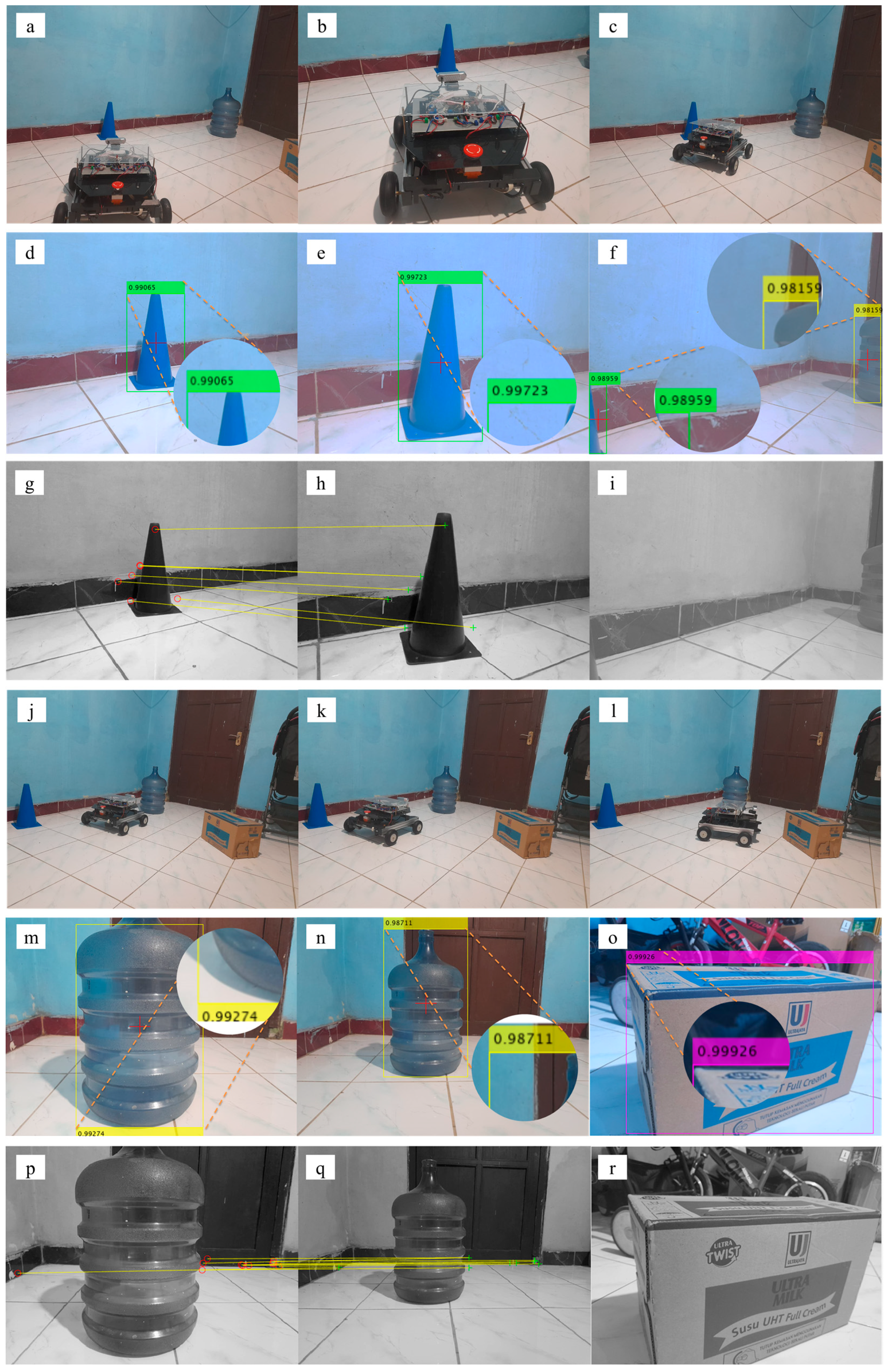

5.1. Experimental Settings

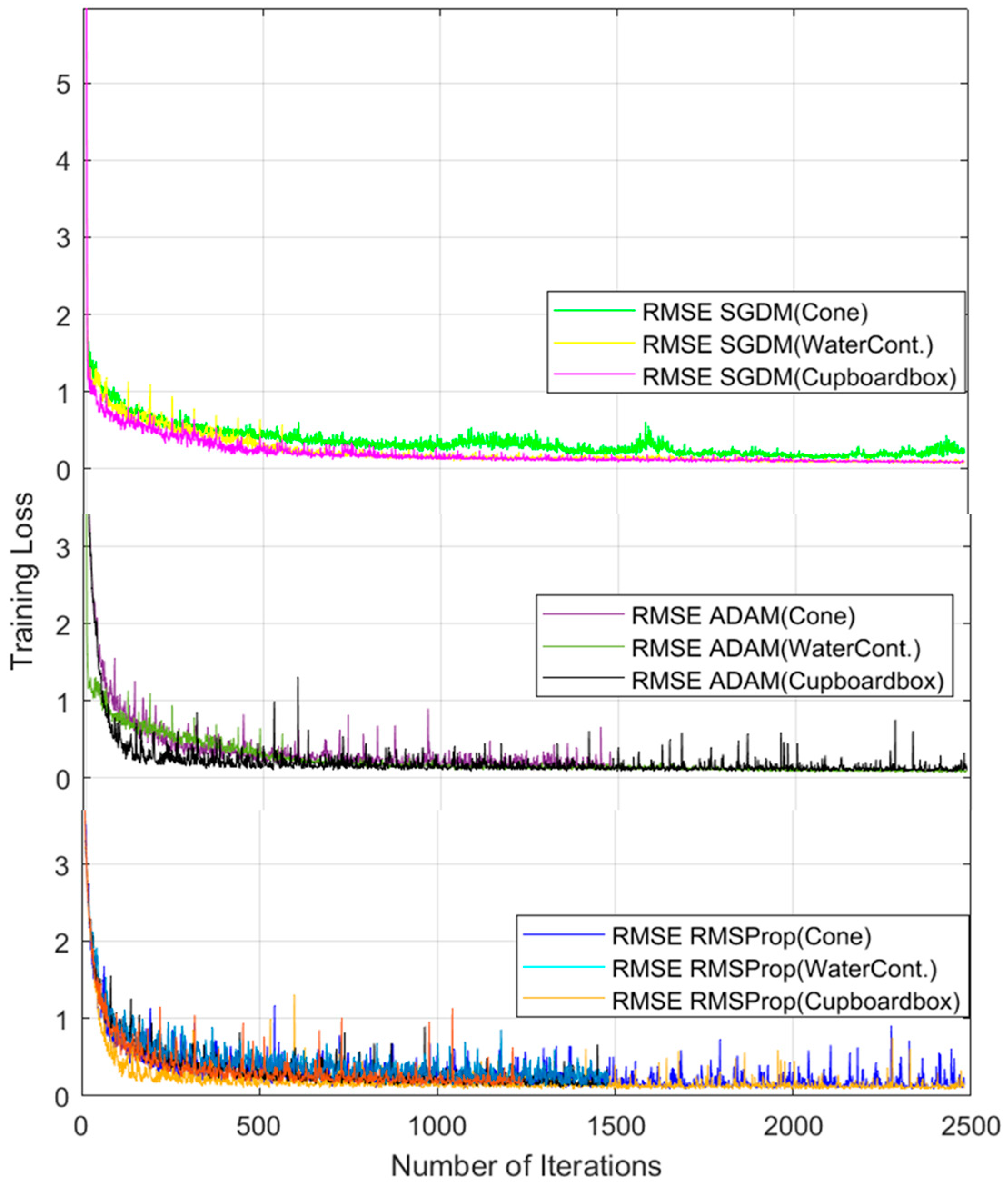

5.2. Detection Evaluation

5.3. DAL Navigation Experiments

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Digani, V.; Sabattini, L.; Secchi, C. A Probabilistic Eulerian Traffic Model for the Coordination of Multiple AGVs in Automatic Warehouses. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2016, 1, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ma, X.; Shu, L.; Hancke, G.P.; Abu-Mahfouz, A.M. From Industry 4.0 to Agriculture 4.0: Current Status, Enabling Technologies, and Research Challenges. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2021, 17, 4322–4334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.; Rebelo, P.M.; Rocha, L.F.; Costa, P.; Veiga, G. A* Based Routing and Scheduling Modules for Multiple AGVs in an Industrial Scenario. Robotics 2021, 10, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liu, J.; Huang, Z.; Peng, Y.; Pu, H.; Ding, L. Adaptive Impedance Control of Human–Robot Cooperation Using Reinforcement Learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 64, 8013–8022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Xiong, M.; Zhong, W.; Xiong, H. Towards Industrial Scenario Lane Detection: Vision-Based AGV Navigation Methods. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation (ICMA), Beijing, China, 13–16 October 2020; pp. 1101–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yang, X.; Wu, L.; Hu, J.; Zou, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, J. Pre-Inpainting Convolutional Skip Triple Attention Segmentation Network for AGV Lane Detection in Overexposure Environment. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 10675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matos, D.; Costa, P.; Lima, J.; Costa, P. Multi AGV Coordination Tolerant to Communication Failures. Robotics 2021, 10, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Khandakar, A.; Ahmed, S.; Al-Khuzaei, F.; Hamdalla, J.; Haque, F.; Reaz, M.B.I.; Al Shafei, A.; Al-Emadi, N. Design, Construction and Testing of IoT Based Automated Indoor Vertical Hydroponics Farming Test-Bed in Qatar. Sensors 2020, 20, 5637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lottes, P.; Behley, J.; Milioto, A.; Stachniss, C. Fully Convolutional Networks with Sequential Information for Robust Crop and Weed Detection in Precision Farming. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 2870–2877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokekar, P.; Hook, J.V.; Mulla, D.; Isler, V. Sensor Planning for a Symbiotic UAV and UGV System for Precision Agriculture. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2016, 32, 1498–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qadeer, N.; Shah, J.H.; Sharif, M.; Khan, M.A.; Muhammad, G.; Zhang, Y.-D. Intelligent Tracking of Mechanically Thrown Objects by Industrial Catching Robot for Automated In-Plant Logistics 4.0. Sensors 2022, 22, 2113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badrloo, S.; Varshosaz, M.; Pirasteh, S.; Li, J. Image-Based Obstacle Detection Methods for the Safe Navigation of Unmanned Vehicles: A Review. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, W.; Thobbi, A.; Gu, Y. An Integrated Framework for Human–Robot Collaborative Manipulation. IEEE Trans. Cybern. 2015, 45, 2030–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bozek, P.; Karavaev, Y.L.; Ardentov, A.A.; Yefremov, K.S. Neural network control of a wheeled mobile robot based on optimal trajectories. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2020, 17, 172988142091607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, R.; Štroner, M.; Kuric, I. The use of onboard UAV GNSS navigation data for area and volume calculation. Acta Montan. Slovaca 2020, 25, 361–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Sebastian, B.; Ben-Tzvi, P. A Collision Avoidance Method Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Robotics 2021, 10, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wu, W.; Qiao, H.; Ji, Y. Brain-Inspired Motion Learning in Recurrent Neural Network With Emotion Modulation. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Dev. Syst. 2018, 10, 1153–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Commun. ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caglayan, A.; Can, A.B. Volumetric Object Recognition Using 3-D CNNs on Depth Data. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 20058–20066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, J.; Xiong, L.; Lin, L.; Ye, M.; Yang, S. Cycle-Consistent Domain Adaptive Faster RCNN. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 123903–123911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, C.; Zhang, D. Deep Learning-Based Object Detection Improvement for Tomato Disease. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 56607–56614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Josef, S.; Degani, A. Deep Reinforcement Learning for Safe Local Planning of a Ground Vehicle in Unknown Rough Terrain. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 6748–6755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Chen, L.; Chen, M.; Ma, Z.; Deng, F.; Li, M.; Li, X. Tender Tea Shoots Recognition and Positioning for Picking Robot Using Improved YOLO-V3 Model. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 180998–181011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Wang, L.; Ren, P. Tinier-YOLO: A Real-Time Object Detection Method for Constrained Environments. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 1935–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyanth, L.G.; Soni, P.; Pareek, C.M.; Machavaram, R.; Nadimi, M.; Paliwal, J. Detection of Coconut Clusters Based on Occlusion Condition Using Attention-Guided Faster R-CNN for Robotic Harvesting. Foods 2022, 11, 3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, Y.-C.; Muslikhin, M.; Hsieh, T.-H.; Wang, M.-S. Stereo Vision-Based Object Recognition and Manipulation by Regions with Convolutional Neural Network. Electronics 2020, 9, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, R.; Wang, K.; Bai, J.; Xu, Z. Unifying Visual Localization and Scene Recognition for People With Visual Impairment. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 64284–64296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chalup, S.K.; Murch, C.L.; Quinlan, M.J. Machine Learning With AIBO Robots in the Four-Legged League of RoboCup. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C Appl. Rev. 2007, 37, 297–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ali, M.A.H.; Baggash, M.; Rustamov, J.; Abdulghafor, R.; Abdo, N.A.-D.N.; Abdo, M.H.G.; Mohammed, T.S.; Hasan, A.A.; Abdo, A.N.; Turaev, S.; et al. An Automatic Visual Inspection of Oil Tanks Exterior Surface Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle with Image Processing and Cascading Fuzzy Logic Algorithms. Drones 2023, 7, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semwal, A.; Lee, M.M.J.; Sanchez, D.; Teo, S.L.; Wang, B.; Mohan, R.E. Object-of-Interest Perception in a Reconfigurable Rolling-Crawling Robot. Sensors 2022, 22, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D. Fast-BoW: Scaling Bag-of-Visual-Words Generation. In Proceedings of the 2018 British Machine Vision Conference, Newcastle, UK, 2–6 September 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, M.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, L.; Zaki, H.F.M.; Mian, A. Benchmark Data Set and Method for Depth Estimation From Light Field Images. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2018, 27, 3586–3598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dornaika, F.; Horaud, R. Simultaneous robot-world and hand-eye calibration. IEEE Trans. Robot. Autom. 1998, 14, 617–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, J.; Wei, J.; Chen, L.; Rech, P.; Adam, K.; Guo, G. Soft errors in DNN accelerators: A comprehensive review. Microelectron. Reliab. 2020, 115, 113969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muslikhin; Horng, J.-R.; Yang, S.-Y.; Wang, M.-S. Self-Correction for Eye-In-Hand Robotic Grasping Using Action Learning. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 156422–156436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.-J.; Yang, S.-Y.; Chen, Y.-P.; Muslikhin, M.; Wang, M.-S. Slip Estimation and Compensation Control of Omnidirectional Wheeled Automated Guided Vehicle. Electronics 2021, 10, 840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, S.; Busoniu, L.; Babuska, R. Experience Replay for Real-Time Reinforcement Learning Control. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C Appl. Rev. 2012, 42, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, A.G.; Smart, W.D. Verifiable Surface Disinfection Using Ultraviolet Light with a Mobile Manipulation Robot. Technologies 2022, 10, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Obstacle | Size (mm) | Weight (gr) | Package | Role |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carton box | 310 × 215 × 235 | 255 | cubical | stop |

| Sporting cone | 475 × 175 | 59 | cone | turn left/right |

| Water container | 510 × 265 | 108 | cylindrical | backward |

| Aspect of the Assessment (Indicators) | Scale/Probability | ω | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Prior to Acting, Plan ( | ||||||

| Calculate the outcome of the YOLOv4 (detection) on one process (%) | - | ≤80 | 81~95 | ≥96 | 5 | |

| Evaluate the present barrier in an indoors of value | - | ≤75 | 76~90 | ≥91 | 3 | |

| SURF-kNN is used to calculate the distance. (%) | - | ≤10 | 11~60 | ≥61 | 7 | |

| Prior to Observe and Consider ( | ||||||

| Verify the prior act of the obstacle achievement | No | - | - | Yes | 15 | |

| Make sure the obstacle is identified | Yes | - | No | 9 | ||

| Compare the current of with the previous of (%) | - | ≥21 | 6~20 | ≤5 | 3 | |

| The cumulative distribution function (CDF) value for the subsequent cycle | - | ≤75 | 76~90 | ≥91 | 5 | |

| Obstacles | Method | Parameters | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confid. | Accur. | Precis. | Recall | F1 | AP | Time (s) | ||

| Sports cone | YOLOv4 | 0.907 | 0.933 | 0.940 | 0.950 | 0.948 | 0.944 | 0.937 |

| DAL (YOLOv4) | 0.938 | 0.963 | 0.943 | 0.950 | 0.967 | 0.933 | 0.949 | |

| Water container | YOLOv4 | 0.908 | 0.922 | 0.921 | 0.934 | 0.948 | 0.877 | 0.918 |

| DAL (YOLOv4) | 0.916 | 0.875 | 0.950 | 0.950 | 0.950 | 0.928 | 0.939 | |

| Carton box | YOLOv4 | 0.932 | 0.940 | 0.950 | 0.938 | 0.943 | 0.921 | 0.937 |

| DAL (YOLOv4) | 0.923 | 0.964 | 0.950 | 0.908 | 0.969 | 0.977 | 0.945 | |

| µ YOLOv4 | 0.916 | 0.932 | 0.937 | 0.941 | 0.946 | 0.914 | 0.931 | |

| µ DAL (YOLOv4) | 0.926 | 0.934 | 0.948 | 0.936 | 0.962 | 0.946 | 0.944 | |

| σ YOLOv4 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.012 | 0.007 | 0.002 | 0.028 | 0.012 | |

| σ DAL (YOLOv4) | 0.009 | 0.042 | 0.003 | 0.020 | 0.009 | 0.022 | 0.013 | |

| Methods | Attempt Number | Rate of | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Success | Failures | ∑ Cycle | Prob. | Ave. | Time (m) | |

| YOLOv4 | 54 | 4 | n/a | 0.931 | 0.902 | 0.40 |

| 49 | 9 | n/a | 0.874 | |||

| ∑ | 103 | 13 | - | - | - | - |

| DAL | 57 | 1 | 63 | 0.982 | 0.952 | 0.36 |

| 50 | 8 | 72 | 0.923 | |||

| ∑ | 107 | 9 | 135 | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aryanti, A.; Wang, M.-S.; Muslikhin, M. Navigating Unstructured Space: Deep Action Learning-Based Obstacle Avoidance System for Indoor Automated Guided Vehicles. Electronics 2024, 13, 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13020420

Aryanti A, Wang M-S, Muslikhin M. Navigating Unstructured Space: Deep Action Learning-Based Obstacle Avoidance System for Indoor Automated Guided Vehicles. Electronics. 2024; 13(2):420. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13020420

Chicago/Turabian StyleAryanti, Aryanti, Ming-Shyan Wang, and Muslikhin Muslikhin. 2024. "Navigating Unstructured Space: Deep Action Learning-Based Obstacle Avoidance System for Indoor Automated Guided Vehicles" Electronics 13, no. 2: 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13020420

APA StyleAryanti, A., Wang, M.-S., & Muslikhin, M. (2024). Navigating Unstructured Space: Deep Action Learning-Based Obstacle Avoidance System for Indoor Automated Guided Vehicles. Electronics, 13(2), 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics13020420