1. Introduction

A large number of domain names on the Internet are misused daily for cybercriminal activities, ranging from spoofing victims’ private information (phishing), to maliciously installing software onto end-users’ devices (malware attacks), to distributing illegal obscene videos. Internet abuse continues to victimize millions of people each year, reducing trust in the Internet as a place to conduct business and non-business activities [

1,

2]. This decline in confidence has a detrimental effect on all stakeholders in the Internet ecosystem, from end-users to infrastructure service providers.

A lot of research and resources are devoted to how to identify or detect these abusive domains early and accurately [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8]. However, the issues of determining which Internet entities are responsible and what methods are used to handle discovered abusive domains are worthy of in-depth study [

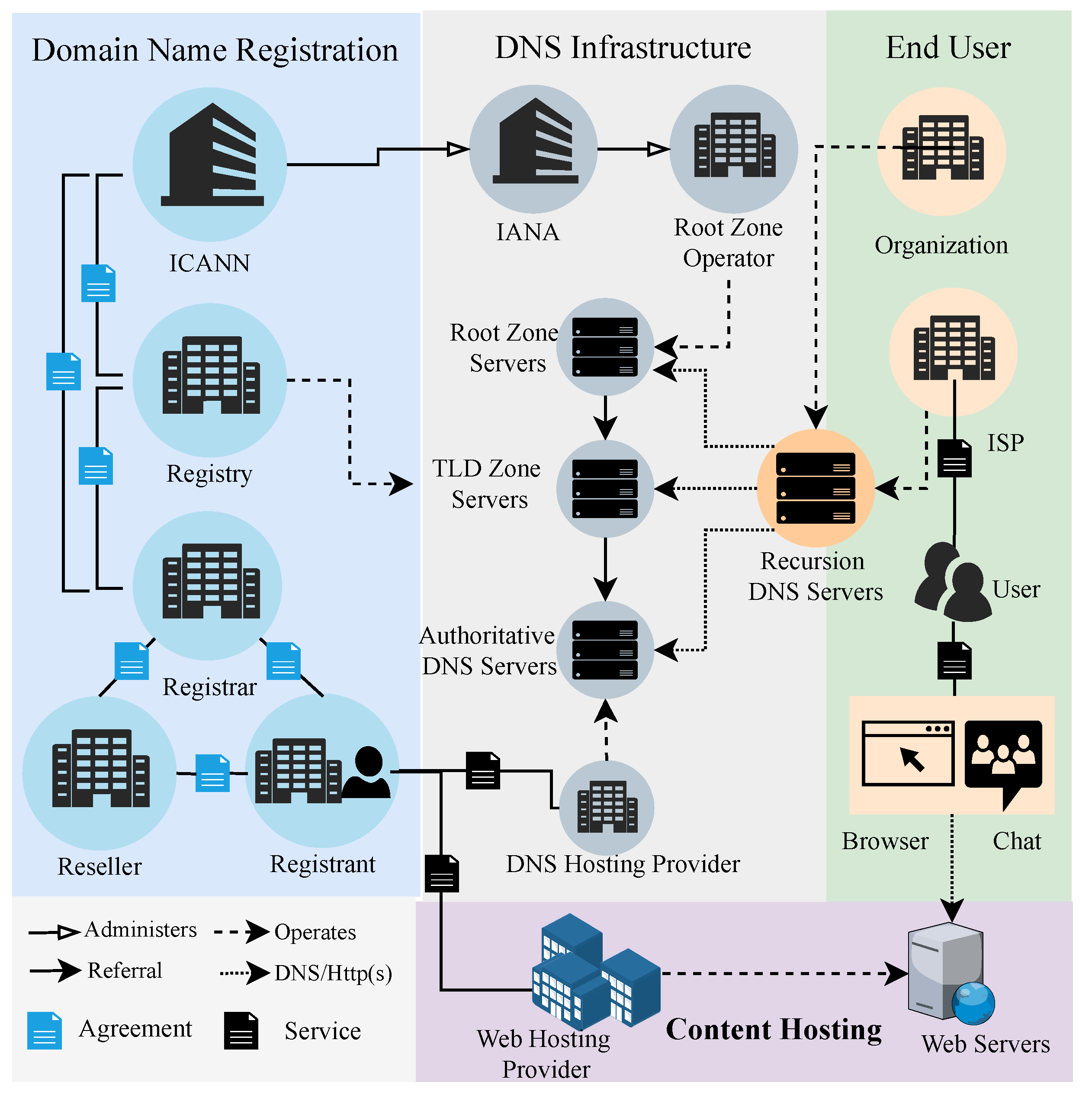

9]. An abusive domain name involves many Internet entities (e.g., registrars and web hosting providers), from registration to the commission of cybercrime, as shown in

Figure 1. As a result, the fight against domain name abuse is not the fight of one person or organization but a battle requiring the entire community’s participation [

10]. The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) states that the best strategy to combat domain name abuse is to join many entities and choose the best approach, such as governments, operators, institutions, and Internet communities.

In China, pornography and gambling domains are not only defined as abusive but are also against the law. At the same time, China has one-fifth of the world’s Internet users. Therefore, the government, the security community, and academia need to study mechanisms to deal with abusive domains quickly and effectively. As a result, using pornography and gambling domain names as examples, we present the first empirical study on the usability and effectiveness of Internet entities for receiving abusive reports and handling abusive domains.

First, we investigate and collate in detail China’s processing mechanisms in receiving reports and dealing with abusive domains. In addition to each Internet entity, the Chinese administration established four administrative governance entities to receive abuse reports about domain names from the public. This cooperative mechanism involves as many Internet entities and individuals as possible in handling abusive domains (

Section 3). Second, we obtained 300,000 pornographic and gambling domains and their associated data, such as registration information and IP addresses. The associated data is used to identify specific Internet entities, such as domain registration including the domain registrar (

Section 4). Next, we selected the appropriate 2433 abusive domains and reported them to 43 companies and service providers across six categories of Internet entities. Then, after nearly two weeks, we observed the changes of the reported domains to evaluate the effectiveness of Internet entities in handling abusive domains (

Section 5). Finally, we discuss the scope of protection and disadvantages of each method of dealing with abusive domains, i.e., whether the abusive domains can escape handling. Moreover, based on the problems discovered in reporting abusive domains, we offer suggestions and solutions to Internet entities (

Section 6).

In short, we make the following contributions:

For the first time, we detail the role and mechanism of the Chinese government in dealing with abusive domains. This cooperative mechanism serves as a reference for Internet organizations (e.g., ICANN), security agencies, and other governments to combat abusive domains.

We present the first empirical study on the usability and effectiveness of all Internet entities in the DNS ecosystem for receiving abuse reports and handling abusive domains. This evaluation provides governments, the Internet community, and security organizations with a more comprehensive and clear view of the current realities of dealing with abusive domains. Moreover, Internet entities in the DNS ecosystem need to be targeted to improve their ability to deal with abuse reports.

Based on the methods used by Internet entities to deal with abusive domains, we analyze the scope of protection of each method and whether abusive domains can escape governance. Then, we provide targeted and practical advice to entities in handling abusive domains.

This paper aims to provide a more detailed overview of the handling of abusive domains, from which Internet entities should report to, to what methods the entities have used to deal with abusive domains, to how effective the methods used have been. This paper is intended for audiences across the Internet infrastructure and cybersecurity industries.

3. Joint Mechanism to Handle Abusive Domains

A government-led, multi-party (e.g., domain name registrars, Internet security organizations) governance mechanism for abusive domains has emerged in China. The Central Committee for Network Security and Informatization is the core of the governance entity, the private sector, civil society, and other multi-body collaborative governance. This occurs through legislation and regulation, administration, self-regulation, technical prevention, international cooperation, and other activities dealing with abusive domain names. This is the same framework as ICANN’s which advocated for handling abusive domain names [

10].

3.1. Handling Abusive Domain Framework

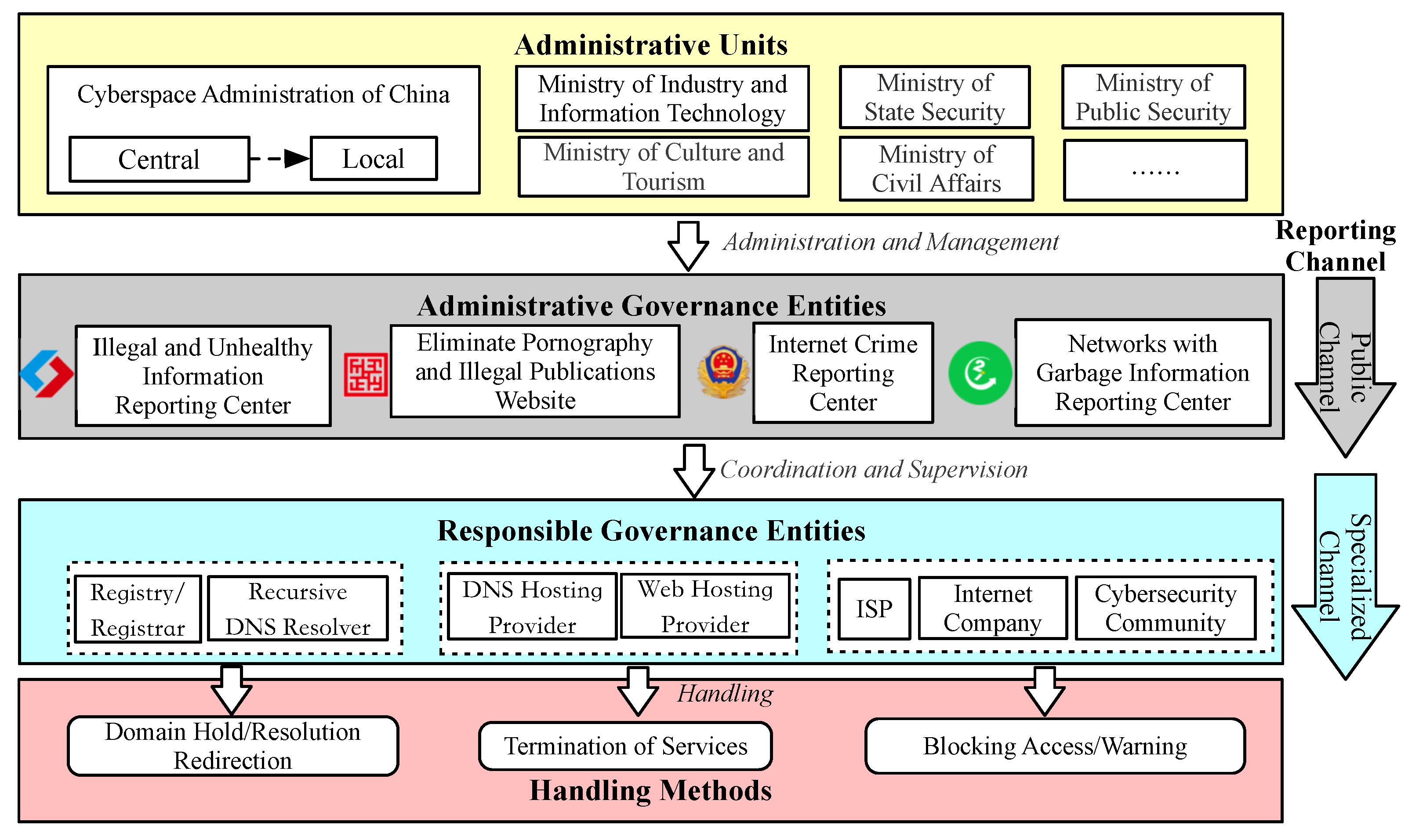

We summarize the handling abusive domain name framework in

Figure 2 by combining the Internet entities involved in domain names as detailed in

Section 2.1.2 and the China-specific mechanism for dealing with abusive domains.

Under multiple Chinese laws and regulations, one or more administrative units jointly establish multiple administrative governance entities based on their responsibilities. These administrative governance entities do not have actual control over the network. However, they are mainly responsible for receiving complaints from the public or organizations and jointly handling and monitoring abusive domains with various responsible governance entities. The responsible governance entity is the Internet entity in the DNS ecosystem that we introduced in

Section 2.1.2. Internet entities have the real ability and responsibility to deal with abusive domains within their jurisdiction.

3.2. Administrative Governance Entities

To address the harm caused by abusive activities, including domain name abuse, more quickly and effectively, several administrative governance entities have been established under the supervision of Chinese government departments. Their primary job is to collect evidence of abusive behavior reported by the public or organizations and work with the appropriate responsible governance authorities to prevent or reduce abusive behaviors promptly. As shown in

Figure 2, there are four main entities, which are described in detail below.

Illegal and Unhealthy Information Reporting Center (

https://www.12377.cn, accessed on 25 February 2022) (12377-Center). This reporting center mainly receives reports of illegal information or content types, such as pornography, gambling, fraud, and rumors. It is currently the most active reporting channel in China, receiving more than 10 million abusive reports every month [

28].

Networks with Garbage Information Reporting Center (

https://www.12321.cn, accessed on 25 February 2022) (12321-Center). It mainly receives reports of abuse information, such as pornographic websites, and spam.

Eliminate Pornography and Illegal Publications Website (

https://www.shdf.gov.cn, accessed on 25 February 2022) (shdf-Center). The website mainly receives reports on pornography, piracy, and illegal publications.

Internet Crime Reporting Center (

http://cyberpolice.cn, accessed on 25 February 2022) (Internet-110). This reporting center receives all types of abusive reports. In addition to content-based abusive reports, the center also receives cyber theft, computer vandalism, terrorism, and other illegal and unlawful abusive reports.

In summary, the administrative governance entities established abusive reporting mechanisms focused on receiving reports from the public. After all, the public is numerous and is a direct victim of abuse. In addition, these reporting channels require a low level of Internet knowledge from the public so that users can easily report. However, as shown in the questionnaire survey conducted in

Section 6.3, nearly 57% of the people are not aware of these reporting channels. Therefore, government departments need to increase publicity and promote joint mechanisms to combat abusive domains.

3.3. Responsible Governance Entities

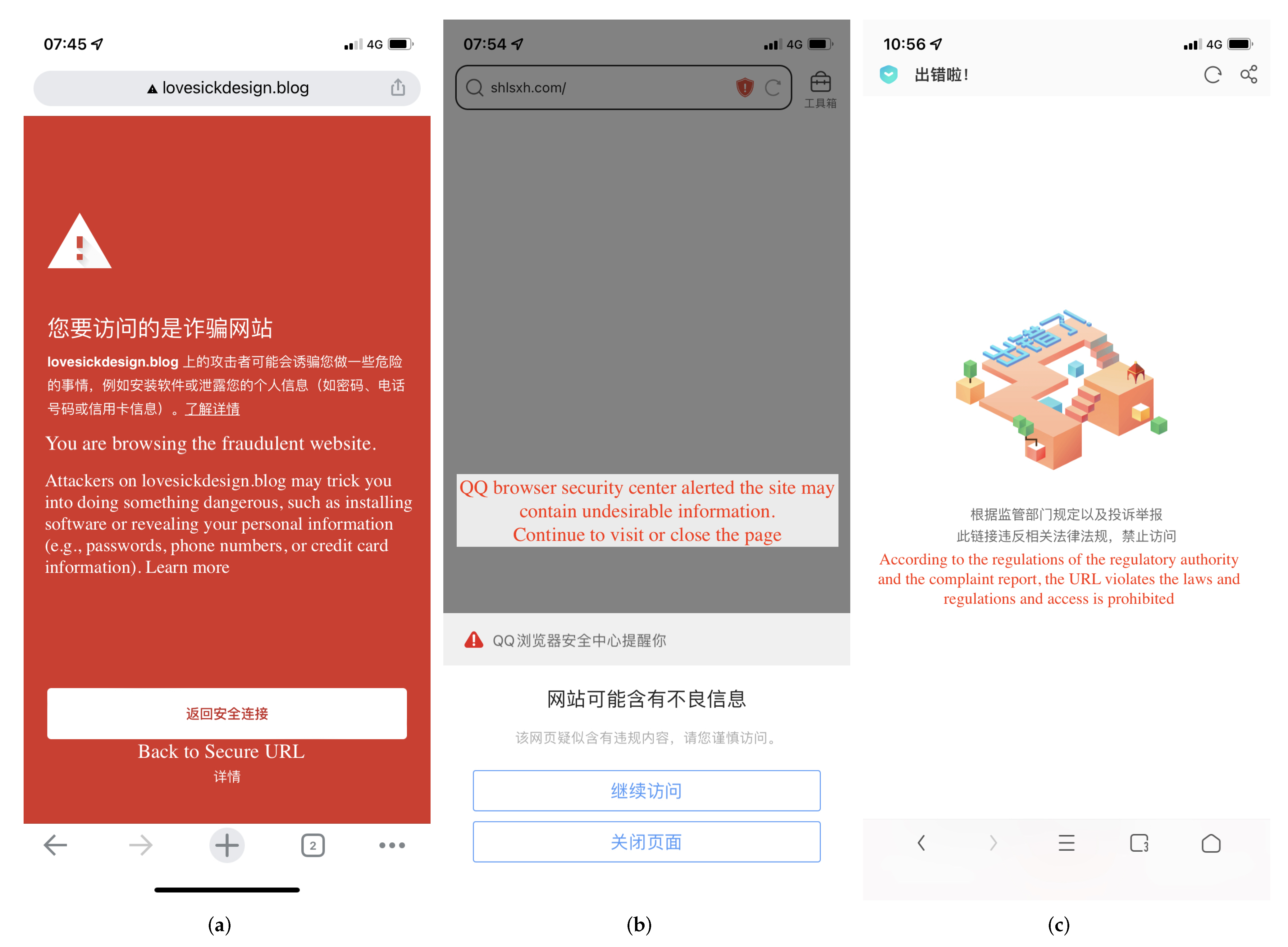

Responsible governance entities, also called Internet Entities, are a critical component of the Internet ecosystem. They are accountable for and capable of dealing with abusive domains. For instance, domain registrars and web hosting providers might remove or refuse to host abusive domain names, respectively. Moreover, it is critical to recognize the role of Internet companies in addressing abusive domains, such as browsers alerting users to the dangers of domain name access, as illustrated in

Figure 3. In

Section 5, we describe in detail the handling of abusive domains by each responsible governance entity. On the other hand, each responsible governance entity only receives and processes reports of domain name abuse within its jurisdiction. Therefore, this requires a higher level of Internet knowledge from the reporters. For example, reporters need to know how to obtain the domain registrar or web hosting provider.

3.4. Handling Methods

Depending on the role of different responsible governance entities in the Internet ecosystem (as illustrated in

Figure 1), their approaches or mechanisms to deal with abusive domain names differ, as shown in

Figure 2. In addition, by analyzing the status of abusive domains after reporting them to the entities (described in detail in

Section 5), we summarize the handling methods of each Internet entity as shown in

Table 1.

One or more entities have the ability and means to handle an abusive domain name. However, different entities handle abusive domain names differently, and some methods are more effective than others. For example, people can no longer be at risk from abusive domains after registrars set the status of the domains to serverhold or clienthold because the domains are essentially deleted from the top-level domain (TLD) zone. In contrast, if only the browser entity puts the abusive domains on its blacklist, then this method can only protect the users who use that browser.

In addition, when choosing which entity to deal with abusive domain names, consider whether the methods they use will cause collateral damage to other non-abusive customers or services. For example, a hacker hacks into a benign website and embeds a phishing page on one of the links. If the entity disables the benign domain, it can impact both non-abuse behaviors and the identified abuse. We explain in detail the handling methods used by all entities in

Section 5.

4. Methodology

In this section, we design the methodology to figure out the methods used by Internet entities to handle abusive domains as well as to evaluate the effectiveness of these entities, as shown in

Figure 4.

4.1. Abusive Domains Detection

In this stage, we detect a large number of pornographic and gambling domains and obtain association data (e.g., domain registration information and DNS records) for abusive domains. This data can support us in reporting abusive domain names to specific Internet entities.

We use keyword matching to obtain a large number of pornographic and gambling domains, and the detailed steps are as follows.

First, we downloaded over 260 million domain names from Domain Monitor (

https://domains-monitor.com/, accessed on 25 February 2022). These domains come from over 1,500 TLD zones, and this also indicates that these domains have DNS records.

Second, we employed a web crawler to attempt to retrieve the web pages of these domains. In particular, for each domain name, the web crawler sequentially fetches the webpage from the URL list (

http://example.com,

http://www.example.com, accessed on 25 February 2022;

https://example.com, and

https://www.example.com, accessed on 25 February 2022), and ends if it successfully fetches the webpage for a particular URL. Then, we extracted the text content from the tags title, keywords, and description on each webpage.

Finally, we identified many pornographic and gambling domains by matching the extracted text with the pre-collected pornographic and gambling keywords. These keywords (shared in GitHub (

https://github.com/mrcheng0910/reporting_abusive_domains/blob/main/abusive_keywords.txt, accessed on 25 February 2022)) are the more frequent Chinese words in pornography and gambling websites that we collected manually in the early stages, such as 做爱(sex), 成人电影(adult movies), and 澳门娱乐场(Macau casinos).

As described earlier, abusive domain detection is popular and worthy of in-depth study. However, the primary objective of this paper is to evaluate the effectiveness of Internet entities in handling abusive domains. Therefore, after we obtained 300,000 pornographic and gambling domain names using the method above, we now have enough abusive domains to support the research in this paper.

In addition, we develop programs to obtain the IP address and domain registration information (WHOIS) of abusive domains. IP addresses are used to find the web hosting providers for domain names. The registration information contains a clue about the domain registrar and the DNS hosting provider. Moreover, the domain status field in the registration information is one of the essential identifiers to determine whether the registrar is handling the abusive domains.

4.2. Abusive Domains Reporting

Reporting abusive domain names to the relevant Internet entities is the first step in dealing with them. Most entities offer different ways to report abusive services. The reporting service consists of two main components: A channel for abuse reporting provided by the network entity; and a requirement for users to provide strong evidence to prove that the domain name is abusive.

4.2.1. Reporting Evidence

When entities receive abuse complaints, they require evidence to substantiate the charge, as all domain abuse is presumed until proven. Reasonable and complete evidence helps entities address abusive activities as quickly as possible, reducing the time of victimization and effort needed for entities to handle abuse reporting. The amount of documentation regarding the abusive domain names required varies from entity to entity, case to case, and type to type. As shown in

Table 2, we summarize what most entities require evidence to be submitted to contain. The Orgs field in the table indicates the number of organizations we surveyed. Desc indicates the description of the reported abusive domain name.

There is no data to suggest that the more evidence there is, the better. The evidence submitted by the reporter can only be used as a reference, and the final judgment of whether a domain name is abusive lies in the abusive criteria set by each entity. More content will only increase the reporter’s workload and reduce the likelihood of reporting.

4.2.2. Reporting Channel

Internet entities provide different channels for receiving reports of abusive domains from reporters. Through our manual aggregation of channels of reporting services for a large number of entities, there are two main ways: Platform and Email. By comparison, the reporting platform format is more user-friendly than email for submitting evidence and maintaining uniformity of evidence for entities to reference and confirm the abuse. While establishing and maintaining the platform requires more resources, this approach helps deal with abusive behavior and enhances the entity’s credibility in the long run. Additionally, the reporting platform is more interactive, and the reporter can view the progress of the reported domain name and offer additional proof as necessary.

Reporting Platform. Users or organizations can report abusive activities to the entities through the reporting platforms. The models for these platforms include the web and apps (

Figure 5), established and maintained by the entities. The entity displays the required evidence content of the abusive domain name (or URL) on the website or app, and the user can directly input and submit it. The administrative governance entity primarily uses a reporting platform to receive reports from the public. Meanwhile, the state or province provides an app to receive fraud or gambling abuse, as shown in

Figure 5. In addition, some larger companies or organizations also use platforms to receive abusive reports, such as registrars like Alibaba Cloud Computing (Beijing) Co., Ltd. and Tencent Cloud Computing (Beijing) Limited Liability Company.

Reporting Email. Reporting abusive domains via email is the way most entities offered, even if a platform has been provided. Entities provide an email to receive reports of abuse, such as

abuse@example-company.com, and require that the content of the email contain evidence of the abusive domain name.

4.2.3. Overall

In this stage, we select the appropriate abusive domain names and report them to the corresponding Internet entities. The administrative governance entities can only coordinate with the responsible governance entities (Internet entities) to deal with abusive domain names. Therefore, this paper focuses on reporting abusive domains to Internet entities and assessing their effectiveness in dealing with abusive domains. Moreover, the abusive domains we report must be within the entities’ jurisdiction. Therefore, the corresponding Internet entity can be figured out by using the extensive base information (e.g., IP and registrar) of the abusive domain names we obtained in the previous stage. For example, using the IP location service provided by MaxMind (

https://www.maxmind.com, accessed on 25 February 2022), we can discover the web hosting provider of the abusive domain.

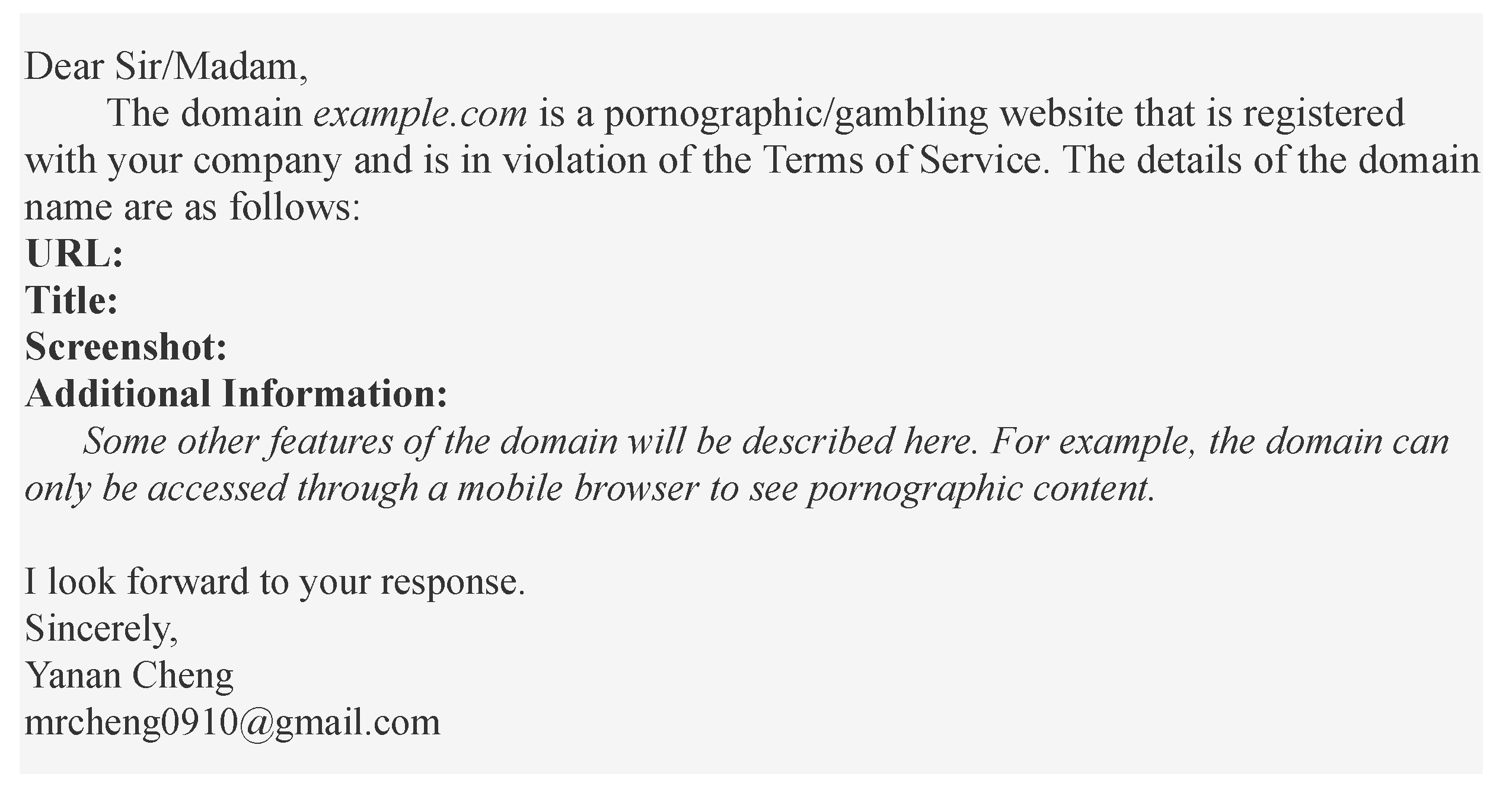

We prefer the reporting platform if the entity gives it; otherwise, we use the email provided by the entity to report abuse. For instance,

Figure 6 illustrates the template we use when reporting the registrar of domain name abuse; the details of the reported abuse for each entity we present in

Section 5.

4.3. Evaluation of Handling Results

After reporting abusive domains to the Internet entities, we monitor changes in the domain names over time (e.g., domain status code) to determine whether the abusive domains are being handled and the methods used. As described in

Section 3.4, various entities may have varying methods for handling abusive domains. As a result, we track changes in the data associated with various domain name dimensions to determine what methods Internet entities use to deal with abusive domains, as illustrated in

Table 3.

For abusive domain names reported to the Internet entities, we need to monitor the changes in the corresponding data.

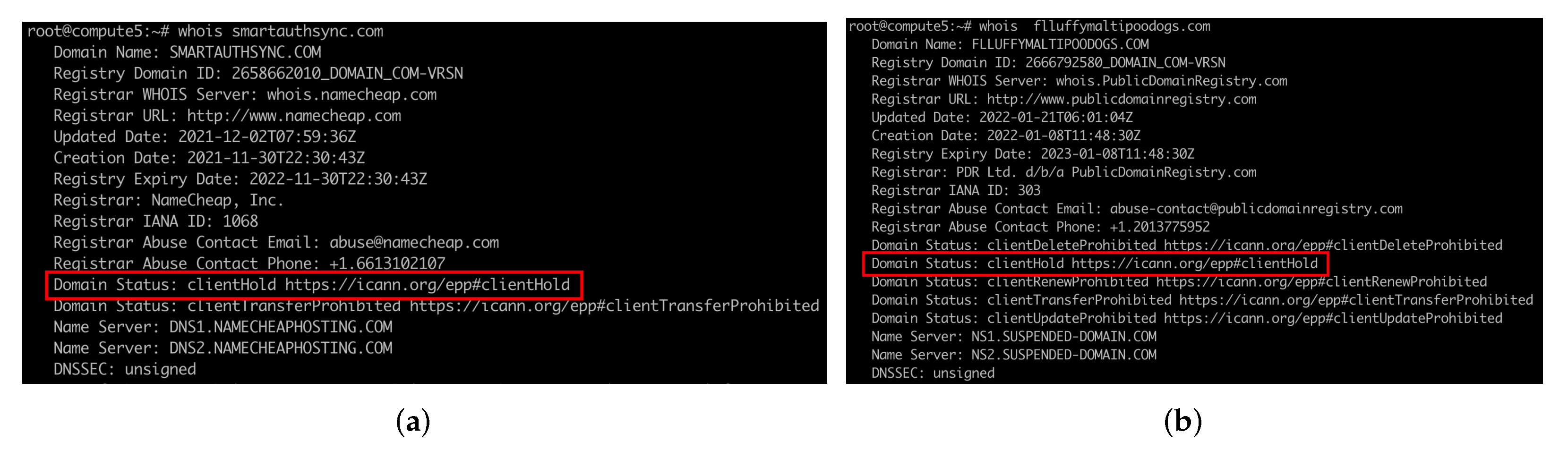

Registrar. We only need to pay attention to the changes in the registration information of the abusive domain names reported to the registrar to identify whether the registrar is handling reported domains. For example, in our subsequent monitoring data (

Section 5), we find that the registrar would change the status of a real abusive domain name from OK to Serverhold or Clienthold, which results in the abusive domain name not being resolved properly.

Recursive DNS Resolver. The recursive server redirects the abused domain name to a specified IP address. We can discover this by tracking the changes in the IP address of the abusive domain.

ISP, DNS and Web Hosting Provider. For abusive domain names reported to these three types of Internet entities, we need to track both DNS and webpages in order to determine what methods they use to handle abusive domains. We use a web crawler to automate the retrieval of web pages for domain names.

Browser. To identify the method and effectiveness of handling abusive domain names at the browser level, we must manually enter the abusive domain into the browser. Then, we track the changes in the content of the web pages displayed by the browser.

We focus on two quantifiable metrics, the number of abusive domains handled and the response time, to evaluate the entity’s effectiveness in handling abusive domains. The more domains handled and the shorter response time indicate that the entity is more effective in handling abusive domains. On the other hand, we evaluate the effectiveness from a practical point of view by analyzing whether the methods used by Internet entities to deal with abusive domain names are evadable.

5. Reporting and Handling Results

In this section, we select and report the appropriate 2433 abusive domains to 43 service providers across six categories of Internet entities. We present the channels used by each provider to receive reports, identify their methods of dealing with abusive domain names, and analyze their effectiveness.

5.1. Domain Name Registrars

Domain registration is the initial step in an attack involving aggressive behavior. When registering domain names, abusers typically choose the appropriate registrar that offers affordable domain names or is less likely to interfere with domain name activities. As a result, registrars have a unique advantage in dealing with abusive domain names. From the registration information (i.e., WHOIS) of the abused domain name acquired, we extract the registrar’s name, a link to the registrar’s home page, and an email address for reporting abused domains. Then, using ICANN-authorized registrar information, we identify registrars affiliated with China, as listed in

Table 4.

5.1.1. Reporting Methods for Registrars

As is well known, the domain registration information contains the registrar’s email for receiving reports of domain name abuse. Additionally, we examine registrars’ websites to see if they provide platforms for receiving reports. If both the platform and email channels are available, we prefer the platform. As seen in

Table 4, all others, except AliCloud, DNSPod, and XinNet, provide solely email reporting channels. Along with domain name registration, the three companies that provide reporting platforms offer various other network services, such as cloud computing, so the platforms are better able to receive all kinds of abusive reports.

On the one hand, we would like to share our experience in the reporting process from the perspective of information feedback. Whether we report abusive domains via email or the platform’s method, most registrars will give us feedback, except for registrar MeiCheng. The feedback is mainly used to confirm that the report was received, that the domain we reported is not registered with this registrar, or to inform us that the abusive domain has been handled. This feedback is critical since it can demonstrate that reporters reported emails had been received rather than filtered into email spam.

On the other hand, we discuss our interactions with the registrar’s staff members who deal with abuse reports from an information interaction standpoint. The email method provides a more interactive experience than the platform. When employees have any questions about the domain that we reported by email, they promptly provide specific feedback, and we add further supporting data by directly replying to the email. However, because the platform’s appearance and ability to provide feedback are fixed, we can only get feedback passively from one another. If we have concerns about their unprocessed domain name, we cannot find an appropriate feedback channel, which may fail this complaint.

5.1.2. Handling Results

In order to promote the development of the Internet network, to ensure the safe and reliable function of the Internet domain name system, China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology formulated the Measures for the Administration of Internet Domain Names of China. The measure explicitly requires that the domain name registry or registrar address the abusive domain names, such as pornography and gambling domains. As a result, as shown in

Table 4, all abusive domain names that we reported are being handled by the registrars. Additionally, most registrars cleaned up abusive domains within 24 h. We discuss those registrars who have unique cases.

Registrar AliCloud. This registrar operates various companies globally specializing in domain name registration, including Alibaba Cloud Computing (Beijing) Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China) and Alibaba.com Singapore E-commerce Private Limited. We reported the abusive domain names to the companies in Singapore and Beijing, respectively. As it turns out, the Beijing-based company handled the abusive domain names within 24 h. In comparison, the domains reported to the Singapore company took about five days to handle. Because two of the abusive domain names reported to the Singapore company did not work anymore, they were not addressed.

Registrar West Digital. Within three hours, the West Digital handled the gambling domains we reported. However, this registrar suggested that we report the pornographic domains to the administrative governance entity 12377-Center (described in

Section 3.2). Two weeks after reporting numerous pornographic domain names to 12377-Center, we discovered that the registrar does not address these domains. We cannot determine whether these domains were not validated by 12377-Center, were not submitted to the registrar, or were not addressed by the registrar. Our future research will assess the administrative governance entity’s performance in dealing with abusive domain names.

5.1.3. Handling Methods

After the registrar handled the abusive domain names, we discovered that the registrar mainly employed two types of methods to handle abusive domains by checking changes of domain registration information. We detail the two types of methods as follows.

Setting domain status code to Serverhold or Clienthold. Extensible Provisioning Protocol (EPP) domain status codes, also called domain name status codes, indicate the status of a domain name registration [

29]. For example, an “OK” EPP code indicates a normal state. The registry and registrar have the authority to set the domain status code to Serverhold and Clienthold respectively, which can cause the domains to be nonexistent in the DNS. As a result, more than 80% of registrars set the status codes of abusive domains to Clienthold to deal with abusive domains.

Invalidating domain nameservers (NS). The registrar changes the abusive domain name’s authoritative server with an incorrect one. As a result, the abusive domain name is not resolved correctly, and the user cannot obtain the domain IP address. For example, the registrars DNSPod, Juming, and MeiCheng are changing the authoritative servers to ns1.domains-hold.com and ns2.domains-hold.com.

In general, registrars are more effective in dealing with abusive domain names than other service providers (described in the next section) because of the guidance and constraints of laws and regulations. Some registrars could improve on their response time a bit more. In addition, we find that over 90% of the abusive domains (porn and gambling) in our database use non-Chinese domain registrars, such as Godaddy (

https://godaddy.com, accessed on 25 February 2022), NameSilo (

https://www.namesilo.com, accessed on 25 February 2022). Furthermore, non-Chinese registrars rarely deal with abusive domain names in the pornography and gambling categories, except for child pornography. This leads to some limitations in the scale of dealing with abusive domain names at the registrar level.

5.2. Internet Service Providers

Internet service providers (ISPs) provide services to users for accessing, using, or participating in the Internet. Theoretically, ISPs have more methods and authority to block abusive domains from accessing by users than other Internet entities. There are three ISPs in China: China Unicom, China Telecom, and China Mobile, as shown in

Table 5.

5.2.1. Reporting Methods and Handling Results

As shown in

Table 5, China Telecom and Mobile use the platform channel to receive reports of abusive domains, while Unicom uses email. In addition, none of the ISPs gave us feedback after we reported abusive domains. China Telecom gives users an inquiry code to check the progress of handling abusive domain names. Usually, abusive domain names, especially pornographic and gambling domain names, expect as many users to browse as possible, so their websites themselves do not restrict access to specific ISP users. Based on this, we design experiments to identify abusive domain names addressed by specific ISPs but not by other Internet entities. The main experimental steps are as follows.

Before reporting an abusive domain name to a specific ISP, confirm that users using the networks of all three ISPs can access the domain name normally.

When the domain name reported to a specific ISP is not accessible using that ISP, we use the other two ISP networks to access the domain name. If at least one ISP can still access the domain name usually, it means that the specific ISP handles the abusive domain name.

If each ISP could not access the domain name, the domain name was offline or was handled by another Internet entity other than the ISPs.

Finally, to our surprise, after one month, the abusive domains we reported were still working normally, except for one domain name that expired and two domains that went offline. All ISPs have not handled abusive domains we reported.

5.2.2. Handling Methods

For some time, ISPs did not handle the abusive domain names we reported. However, based on published studies [

30,

31] and our browsing of misused domains, we find that ISPs handle abusive domains primarily using two methods based on on-path blocking: DNS redirection and TCP reset.

DNS redirection. This method, also known as DNS filtering or poisoning, causes the DNS resolvers to return presupposed domain records (e.g., IP addresses) to the clients. This method may be used for malicious purposes such as phishing, for security and business purposes by a company (providing parental control or antivirus filtering services), for Internet service providers’ (ISPs’) own advertising purposes, or by the government to censor access to specific domains [

32,

33,

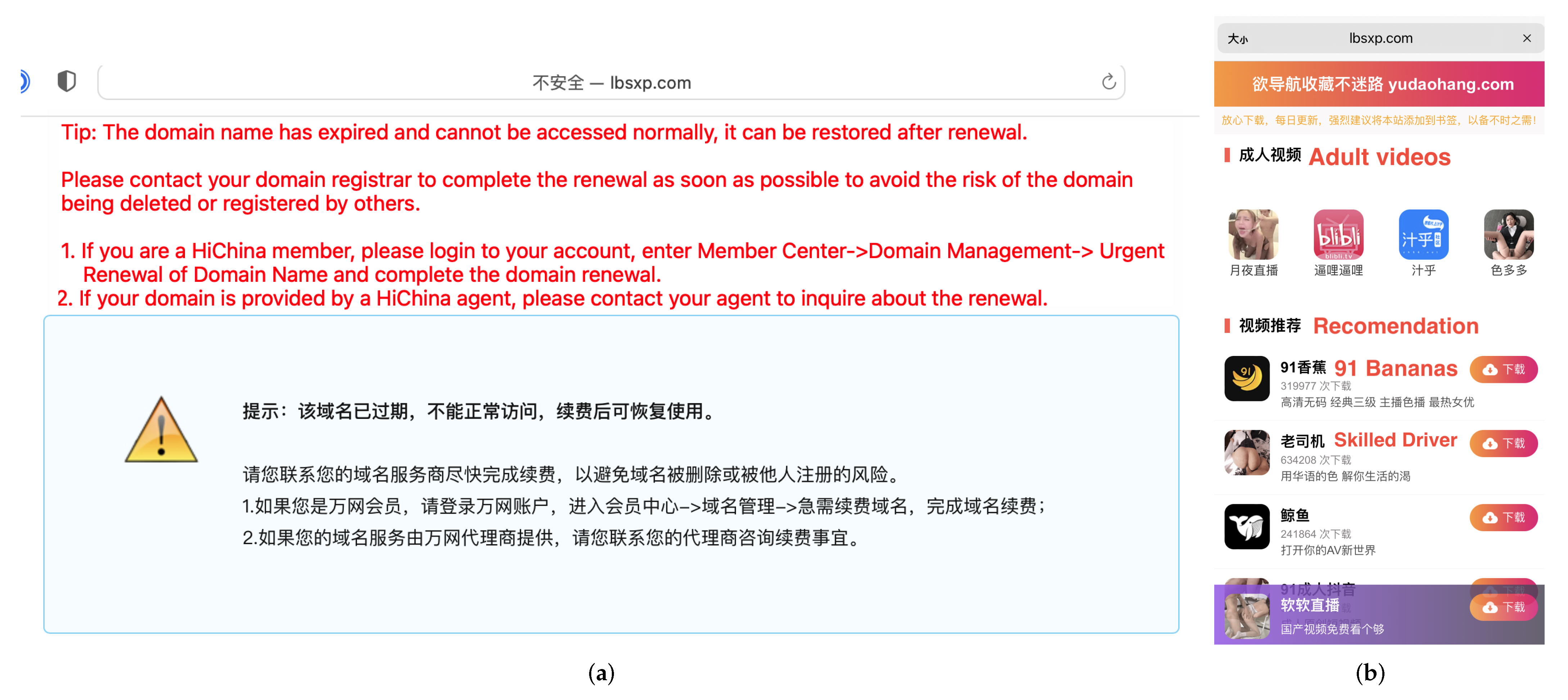

34]. When we use the Telecom cellular network in Weihai City, Shandong province, to visit the domain j***j.com, the warning page shown in

Figure 7a occurs. The page informs the visitor that the domain they visit is fraudulent, thereby prohibiting further access. We discovered that the domain j***j.com’s correct IP address was changed to 182.43.124.6 from 218.6.171.4.

TCP reset. TCP reset is a technique to tamper with and terminate the Internet connection by sending a forged TCP reset packet. This tampering technique can be used by ISPs’ or organizations’ firewalls [

35,

36,

37]. For example, we can access the pornographic domain 6*****r.com normally using Shandong Telecom’s cellular network, but not using ISP Mobile, and the page as shown in

Figure 7b.

ISPs give the public or cybersecurity professionals channels to report abusive domains. In addition, they all have their mechanisms to deal with these domains. However, based on our one-month observation, their response time to deal with abusive domain names needs to be improved. Because different types of abusive domain names have different survival time. For example, phishing domain names only have a few hours [

38]; the longer the response time, the more harm caused by abusive domain names.

5.3. DNS Hosting Providers

DNS hosting providers offer authoritative DNS servers, which are servers that hold, and are responsible for, DNS resource records. The server at the bottom of the DNS lookup chain will respond with the queried resource records, such as IP addresses. Most, but not all, domain registrars include DNS hosting services with registration. Free DNS hosting services also exist. Many third-party DNS hosting services provide free authoritative DNS servers. This paper evaluates how well those providers offering free DNS hosting services handle abusive domain names, as listed in

Table 6.

5.3.1. Reporting Methods

As we described earlier, providers offering multiple Internet services generally receive abuse reports for various types of services on the platform. Providers with only a small number of services can meet the reporting demand through the email channel, as shown in

Table 6. In addition, one week after we reported the abusive domains to each DNS hosting provider, four providers have not given us any feedback on our reports, and the reported domains have not been addressed. Our attempts to contact them by email several times were also unsuccessful.

5.3.2. Handling Results and Methods

As shown in

Table 6, all five DNS hosting providers handled the abusive domains we reported within 24 h, except for three domains that were not accessible at the time of provider verification and were not addressed. Based on the changes in DNS data before and after the abusive domain names were addressed, we inferred the provider’s methods of dealing with abusive domain names. These methods consist of three main types: DNS record deletion, denial of service, and response to servfail.

DNS Record Deletion. This method means that the providers remove the DNS records of the abusive domains we reported from their authoritative DNS servers. This results in the user requesting the IP address of the abused domain and getting a response that the domain name does not exist, thus prohibiting the user from accessing the abused domain name. For example, Providers Juming and 22.cn use this method to deal with abusive domain names.

Denial of Service. After the provider (e.g., Provider Xiamen DNS) uses this method to handle the abused domain name, we request the IP address of the abused domain name and find that the authoritative server does not respond to our request, thus causing the request to time out. This method of denial of service may occur at the authoritative server or at the firewall where the domain name resolution request reaches the authoritative server before.

Response to Servfail. When the authoritative server does not respond, returns a refuse code, or returns Serverfail, both result in the user receiving a Servfail status code returned by the DNS recursive server. For example, we found that Provider Tencent Cloud uses this method to handle abusive domains.

In summary, some DNS hosting providers can deal with reported abusive domains very quickly. However, because there are a large number of free and varying user size providers on the Internet, this results in abusive domains being handled by one provider and then being able to change to another very quickly and with essentially little time and effort. Our experience found that it takes a lot of effort and time to accurately identify the provider based on the name of the authoritative server used for the abused domain name, especially for lesser-known providers. This means that reporting abusive domain names to DNS hosting providers to fight abusive domain names is less effective than other entities.

5.4. Web Hosting Providers

In the same way as the registrar selection, we mainly report abusive domain names using Chinese web hosting providers and then analyze the effectiveness of these providers in dealing with abusive domain names. This is because websites within China require accurate name filing to run online and, at the same time, strict monitoring by domestic web hosting providers. Therefore, most abusive domains are run by non-Chinese web hosting providers. Some abusers choose web services provided by Chinese colocation providers outside of China (e.g., Hong Kong, China). Eventually, we obtained the abusive domains of the colocation providers running in China, as shown in

Table 7.

5.4.1. Reporting Methods

As described in

Section 4, we obtained the IP addresses of the abusive domains. Then, we combine the IP location services provided by MaxMind (

https://www.maxmind.com/en/home, accessed on 25 February 2022), IPinfo (

https://ipinfo.io, accessed on 25 February 2022) and IP138 (

https://www.ip138.com, accessed on 25 February 2022) to identify the web hosting providers of the abusive domains. The methods each provider uses to receive reports of domain name misuse are detailed in

Table 7. We discovered that most providers are offering abusive services reports by email solely. In comparison, most service providers that offer a variety of network-related services use the reporting platform to receive allegations of abuse. For instance, AliCloud, which offers web hosting and domain name registration, receives abuse reports via platform reporting from different businesses.

Several providers provide feedback on the report via email or platform following our reporting. This cordial engagement lets reporters verify that their reporting procedures are correct and providers have received their reports. Particularly in the case of email reporting, there is a great likelihood that the reporter’s email will be filtered into a spam mailbox by the provider’s mail server, resulting in the report’s failure.

5.4.2. Handling Methods and Results

We discovered two primary methods employed by hosting providers to address abusive domain names. One is to notify the website’s owner to remove the abusive content; the other is to cease providing website hosting services. For instance, AliCloud informed us that after receiving and verifying our report, it had instructed the website’s owner to delete the harmful information. Tencent Cloud, on the other hand, immediately ceases hosting abusive websites. As demonstrated in

Table 7, only a few hosting providers responded to our report of abusive domain names seven days later. Tencent Cloud, for example, removed the abusive domain names within 48 h after receiving the report or after requesting additional evidence. AliCloud notified just the abusers, and our investigation revealed that the abusers did not remove the abusive content.

In summary, pornography and gambling-type abusive domains are poorly handled by providers after being reported to Chinese hosting providers. In our opinion, there are two primary causes for this. On the one hand, the IPs associated with abusive domains change frequently, and providers respond slowly to reports. As a result, the provider identifies the abusive domain IP, which may have changed to one that does not fall under the providers’ jurisdiction. Moreover, the IP addresses used for abusive domains may be shared, and a hosting provider that bans abusive IP services risks causing collateral damage to other users.

5.5. Recursive DNS Servers

This paper selects public recursive DNS resolvers (as shown in

Table 8), commonly used in China, to analyze their effectiveness in handling abusive domain names. Some of these DNS servers have features that include handling abusive domain names. For example, the home version of OneDNS blocks pornography and gambling domains.

These recursive DNS servers do not provide reporting channels to the public. Therefore, we used each of these recursive DNS servers to resolve the abusive domains we found and then obtain the IP addresses of these domains. Finally, we discovered how these DNS servers handle abusive domain names by comparing the IPs of the specific domain names that each resolver responded to.

An overview of DNS resolvers and the results of their handling of abusive domain names are presented in

Table 8. On the one hand, we did not find methods for handling abusive domain names from Alibaba 223.5.5.5, Tencent 119.29.29.29, and Baidu 180.76.76.76. We also did not find any relevant information on their official websites for handling abusive domain names (e.g., gambling domains). Of course, it could be because the type or scale of the abusive domain name we used is not on their blacklist of abusive domain names handled. We will continue this in our future research.

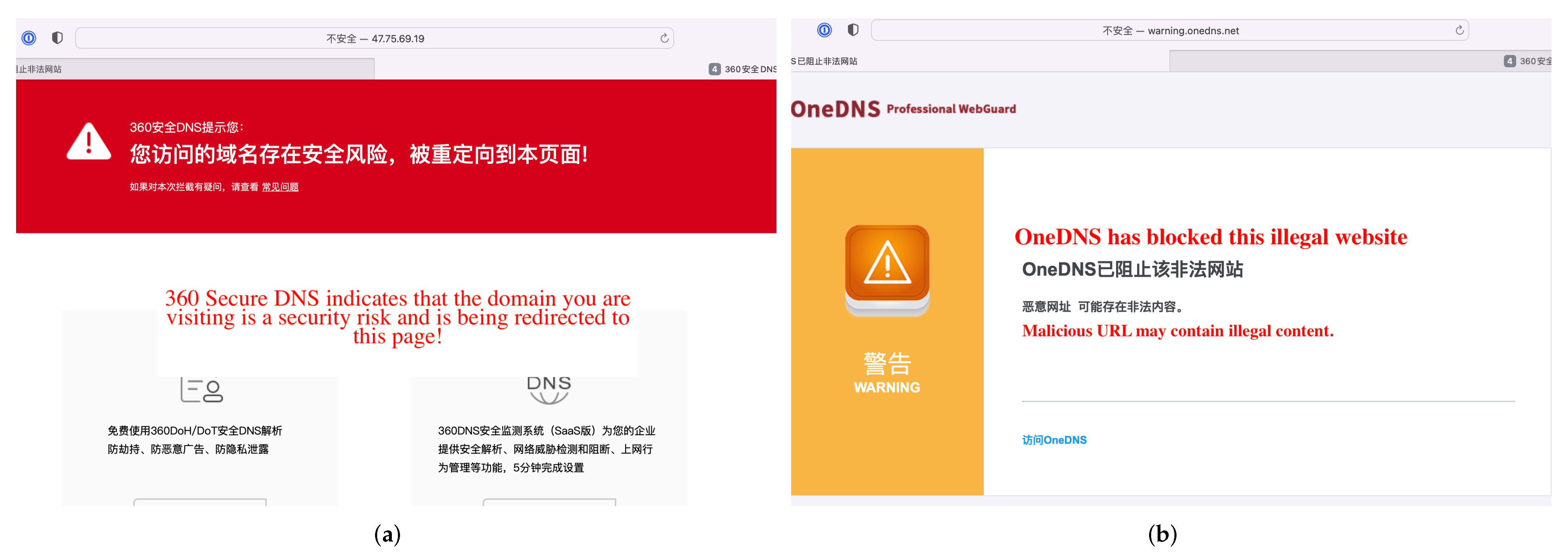

On the other hand, we need to highlight that the other three DNS servers deal with abusive domain names. These DNS recursive servers use DNS redirection (also called DNS hijacking) to block users from accessing abusive domains. The DNS recursive server responds to the user with a preconfigured IP address. For example, DNSPai and OneDNS return 47.75.69.19 and 23.91.96.155, respectively, and when a user accesses an abusive domain name, they will see a warning page, as shown in

Figure 8.

Compared to our abusive domain dataset (300,000 porn and gambling domains), all four DNS recursive servers handle a smaller number of abusive domains, and OneDNS, which handles the most significant number of abusive domains, only accounts for 2% of the total. We speculate that having too many domains in the blacklist affects the response time of the recursive DNS servers. In addition, the long-term maintenance and updating of the blacklist are resource-intensive. Recursive DNS server providers need to balance benefits and security. Overall, DNS recursive servers are important entities that deal with abusive domain names and are well positioned to prevent users from being harmed by abusive domain names.

5.6. Web Browsers

Users use browsers developed by different companies to access pornographic or gambling domains. According to the browser market share published by StatCounter (

https://gs.statcounter.com/browser-market-share/all/china, accessed on 25 February 2022) in February 2022, the top 6 browsers in China are Chrome (48.96%), UC Browser (

https://www.ucweb.com, accessed on 25 February 2022) (11.86%), Safari (11.2%), QQ Browser (

https://browser.qq.com, accessed on 25 February 2022) (8.51%), 360 Safe (

https://browser.360.cn, accessed on 25 February 2022) (7.64%), and Edge (4.47%). In addition, browsers like Chrome, Safari, and Firefox mainly warn users of phishing and malware attacks on the domains or links they are browsing. Finally, we choose the browsers UC, QQ, and 360 Safe (The 360 Safe Browser has a version called 360 Extreme Browser, which can run on multiple platforms, so we chose this version) to see how they handle abusive domains. In addition, to make our evaluation more comprehensive, we evaluate the above three browsers on the Windows, IOS, and Android platforms simultaneously, as shown in

Table 9.

5.6.1. Reporting Methods

All three browsers use the reporting platform to receive abusive domain reports. However, the form of the platform differs from browser to browser, as shown in

Table 10. Both browsers, QQ and 360 Safe, have an independent reporting channel on their interfaces. They have a very prominent reporting button that makes it easy for users to report the abusive domain names they visit. However, 360 Safe Browser only has this service on the android platform, while QQ Browser has it on both mobile platforms. Browsers who want to report abusive domain names to UC Browser need to report them to the online customer service center it provides. This form of reporting is not clear enough, and we had to consult with its customer service before confirming this form.

To our surprise, all browser versions on the PC platform do not provide the channel to report abusive domain names. The friendlier and more convenient the form of domain name reporting for abuse, the more willing and effective the viewer will be in reporting abusive domains. This is supported by the effectiveness of browsers in handling abusive domain names, as described in the following section. At different periods, we reported 50 unaddressed abusive domains to each of the three browsers. Moreover, we set the same number of unreported abusive domains as a comparison group to evaluate how each browser handled abusive domains.

5.6.2. Handling Methods

As shown in

Figure 3, three browsers mainly prevent users from browsing abusive domains by methods of Warning or Redirection. For example,

Figure 3b shows QQ Browser warning users that they are browsing abusive domains. This warning method still allows the user to keep going to the abusive domain name. On the other hand, redirection is a way to redirect the user to a different warning page to inform them that the page is illegal and that they do not have permission to continue accessing the abused domain, as shown in

Figure 3c. In the course of our experiments, we found that the browser’s handling of a domain name is not set in stone and may change from a warning to a redirection.

5.6.3. Handling Results

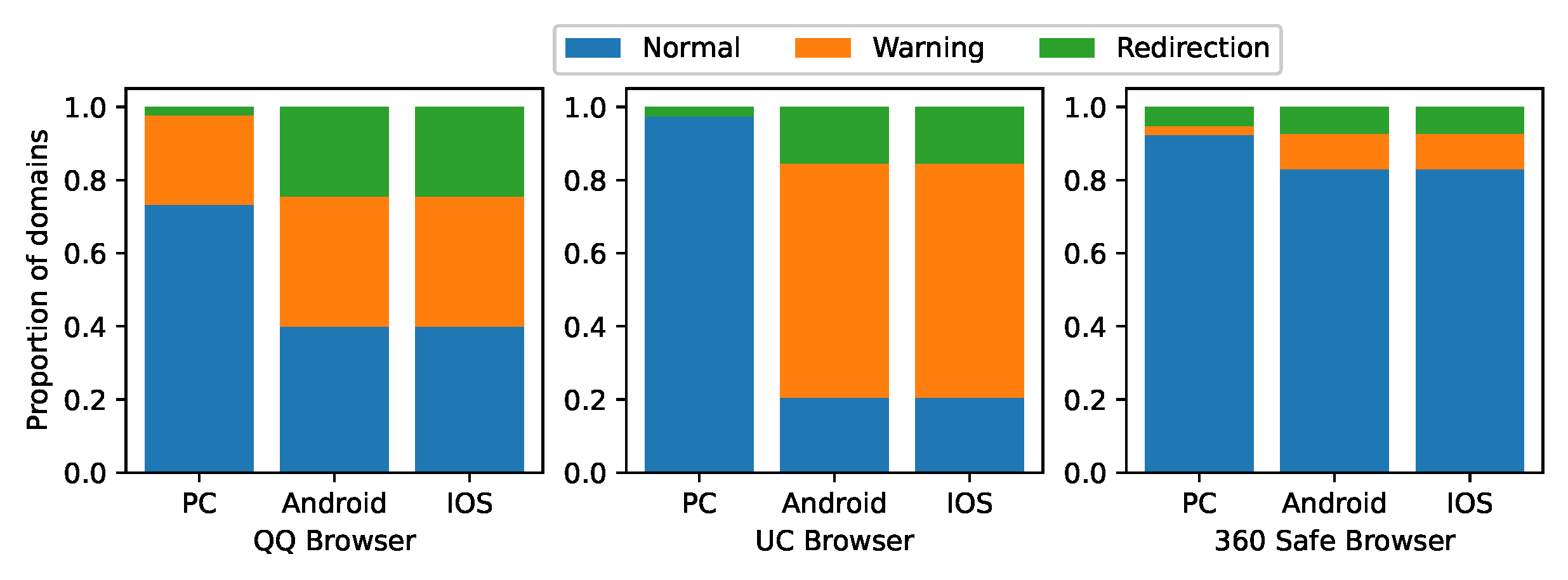

Due to the high volume of images and videos on pornographic and gambling websites, the pages take longer to load completely. Additionally, it takes time for the browser to determine whether or not the domain name is abusive. As a result, we wait 10 s for the page to load and then attempt it no more than three times more. Finally, we get the results of the browser handling the reported abusive domain names, as shown in

Figure 9.

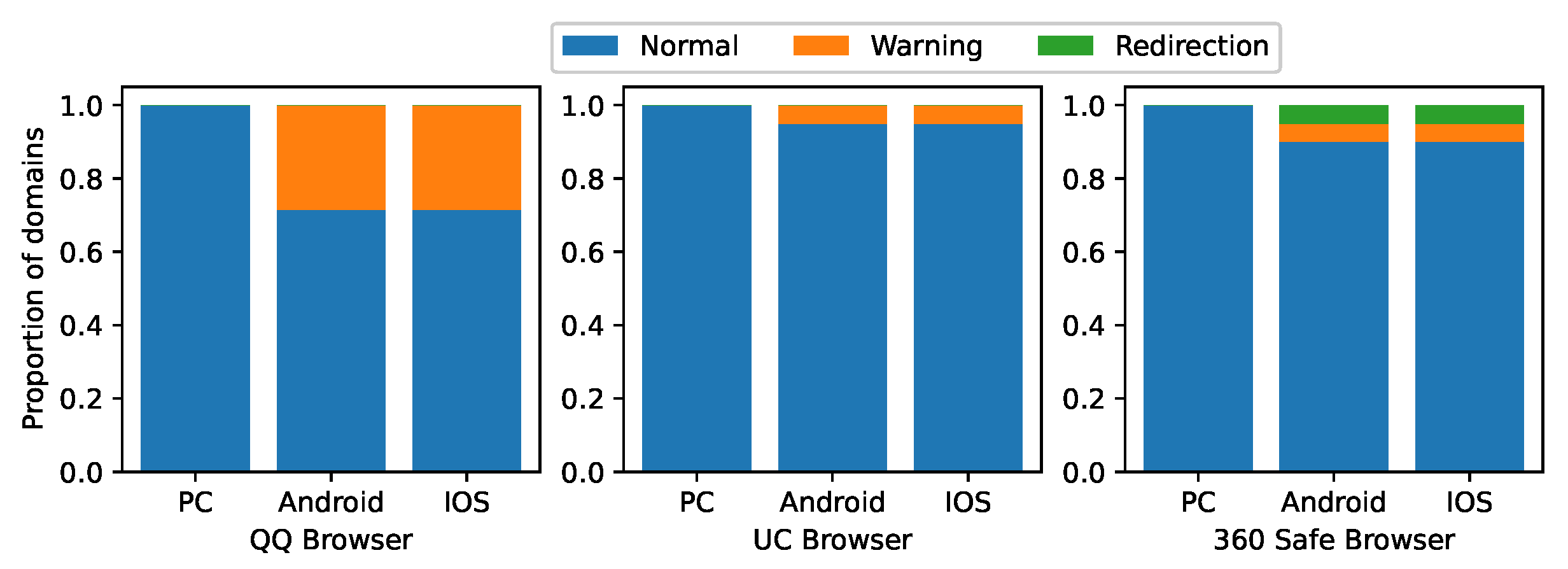

Figure 10 illustrates the browser’s processing of the unreported abusive domain names in the control group.

First, the reported and unreported domains results show that each browser handles some of the reported abusive domains, which proves the validity of our reporting and experimental results.

Second, the number of abusive domain names handled is the highest in the mobile Browser UC, accounting for 80% of the total number, 60% in the Browser QQ, and only 20% in the Browser 360 Safe. We visit the malicious URL reporting channel of the 360 Security Service (

https://fuwu.360.cn/jubao/wangzhi, accessed on 25 February 2022), which mainly receives reports of abuse in the phishing and malware categories. This may be the reason why it handles fewer pornographic and gambling domains.

In addition, the mobile versions of each browser (i.e., Android and IOS) handle the same number of abusive domain names. This indicates that they use the same mechanism for handling abusive domain names, such as blacklists. On the other hand, the quantity of abusive domain names handled by the QQ and UC browsers on Windows is far less than mobile. We brought this security concern to the attention of the UC and QQ browsers’ customer service. The UC Browser’s customer service told us that the browser’s Windows version is no longer being updated and that their product focus is primarily on mobile browsers. Unfortunately, the QQ Browser’s customer service has not given us any feedback yet.

Verifying how different browsers on different platforms handle abusive domain names requires manually typing URLs into mobile browsers, which requires considerable time and effort. As a result, to maximize efficiency, we conducted early experiments to see whether our reported abusive domains were addressed only after a specified period (e.g., three days). However, we later desired to identify when the browsers began handling the reported abusive domains. Therefore, we re-reported 20 abusive domains to the mobile QQ and UC browsers, respectively. We verify whether our reported abusive domains are processed at two-time points (10 a.m. and 4 p.m. from Monday to Sunday) and compute their browser response time accordingly.

The response time of two browsers to the abused domain name is shown in

Figure 11. We can see that UC handled 80% of the abusive domains within 24 h of reporting, while QQ Browser addressed about 60% of the abusive domains by day 5. Then the number of abusive domains addressed does not change anymore.

Browsers are the final barrier to blocking users from accessing abusive domain names. Some browsers generally have better results in dealing with reported abusive domain names. This can significantly reduce the risk of users accessing abusive domain names. However, there are two shortcomings in the browser’s handling of abusive domain names simultaneously. One is that most browsers only warn users that the domain name is risky rather than prohibiting them from accessing it. Users can still ignore the warning and continue to browse the web content, such as porn sites. Second, browsers have different market shares and handle different types of abusive domain names, which means that browsers can only protect a specific scope of users.

6. Discussion and Suggestion

In this section, we discuss topics related to the reporting and handling of abusive domain names by Internet entities in our practice to give researchers a better understanding of the current state. In addition, we provide suggestions to the relevant entities involved in handling abusive domain names. From a global perspective, our research aims to serve as a reference for governments, Internet entities, Internet agencies (e.g., ICANN, CERT), domain abuse reporters, and domain name owners when dealing with abusive domains.

6.1. Non-Abusive Domain Name Appeals

When an Internet entity incorrectly labels a domain name as abusive, the domain owner must file a complaint with the entity demonstrating compliance with the domain name. As a result, each Internet institution that deals with domain name misuse should provide a mechanism for appealing misclassifications. While reporting abusive domain names, we discovered that some significant Internet entities (e.g., browsers and recursive DNS servers) lack or have insufficient appeal channels.

Table 11 lists whether the Internet entity provides channels for appeal in our practice.

Registrars. Suppose the registrar determines that a domain name is abusive. In that case, the registrar notifies the user and requests that the user either remove the abusive content or prove the domain name’s innocence. If the domain name is mistakenly judged to be abusive, the domain name owner will simply submit the required evidence to the registrar.

Internet Service Providers. When ISPs use DNS redirection to intercept abusive domains, they provide a complaint channel, such as a phone number, on the redirected web page (as shown in

Figure 7). If TCP reset interception is used, no appeal channel is provided, and domain owners may not even know why their domains are not accessible to users.

DNS and Web Hosting Providers. When a domain name is confirmed to have abusive activity, the DNS and Web hosting providers will notify the domain owner to clean it up immediately. Just like with registrars, this is a passive method of receiving notifications. However, we are confused by a circumstance. That is, if the abusive domain name expires and is re-registered, the domain owner has no recourse if the hosting provider continues to block the legitimate new domain name.

Recursive DNS Servers and Browsers. These two Internet entities do not provide a direct complaint channel. Their handling of non-abusive domain names can significantly impact the domain name owner. The exception is Browser QQ, whose developer is Tencent Company, which provides an apparel channel. Even with a successful complaint, we do not know if QQ Browser will still block the domain name.

In our experience, there are cases where benign domain names have been misidentified as misused. For example, in

Section 6.4, we registered two new domain names that were wrongly identified as malicious. Therefore, our recommendations to participants in the entire DNS ecosystem are as follows.

Internet entities. Every Internet entity that supports the DNS ecosystem should give domain name owners a channel to appeal, as they do for reporting abusive domain names. Moreover, Internet entities should be more efficient in dealing with domain names that are indeed misclassified as abusive, because dealing with the non-abusive domain is much more about a company’s reputation than dealing with the abusive one.

Domain owners. On the one hand, domain (website) owners should always proactively check whether their websites are being attacked by cybercriminals, such as through embedded malicious codes or phishing URLs. On the other hand, when their domains are mistakenly reported, the owners should either address the malicious behavior of their domain names based on the warning information provided by the Internet entities, or give as much evidence as possible about the domains being benign.

Domain abuse reporters. We believe that abusive domain name reporters should be trained in order to reduce the cases of misreporting. On the one hand, reporters should be trained to identify various types of abusive domain names. For example, they should be trained to correctly identify the brands being spoofed by phishing sites or use third-party detection tools (e.g., PhishTank (

https://www.phishtank.com, accessed on 25 February 2022), Virustotal (

https://www.virustotal.com, accessed on 25 February 2022) to identify malicious domains. On the other hand, reporters should be trained to identify each Internet entity that provides service for abusive domain names, especially those that are more difficult to identify, such as web-hosting providers or DNS hosting providers, as we described in the previous section.

6.2. Optimal Handling Internet Entities and Methods

In

Section 5, we discussed the results of each Internet entity’s handling of abusive domain names based on its characteristics and authority within the DNS ecosystem. We find that the scale of users protected varies from Internet entity to Internet entity. Moreover, the strategy and expense used for the abusive domain name to evade handling are related to which entity uses which method of handling. These two factors are directly related to the effectiveness of dealing with abusive domain names. In this section, we discuss the impact and escapability of the methods used by Internet entities to handle abusive domains so that security employees can use them as a reference for reporting and dealing with abusive domains.

Domain Name Registrars. The registrars apply the Serverhold or Clienthold status to stop abusive domains from resolving on the Internet. None of their services (e.g., websites) will work when domains have this status. In addition, abusive domain names cannot circumvent this handling method.

Web Hosting Providers. The providers discontinue providing web hosting services for the abused domain name, and the abused domain name (or website) becomes inaccessible to the public. However, the abuser can re-host the website with a web hosting service that is not sensitive to handle abusive domains. As a result, abusers can evade handling by the web hosting providers at little cost.

DNS Hosting Providers. The DNS hosting providers remove the DNS records for the abusive domain name from the authoritative DNS servers or simply refuse to provide resolution services for the abusive domain name. Then, the abusive domain name can no longer attack anyone. However, many DNS hosting providers on the Internet offer free DNS hosting services, which allows abusers to switch to another DNS hosting provider at no cost.

ISPs, Recursive DNS Resolvers, and Browsers. All three of these Internet entities can only protect clients using their services from abusive domain names. While their protection scopes are limited, there are no escape methods for abusive domain names against them.

Overall, based on the current state of affairs, selecting the appropriate Internet entity to handle abusive domains to obtain the best results is a complex task. Therefore, based on our research, we present our recommendations to governments, Internet communities and entities, and researchers.

Internet entities. As contributing members of the global DNS ecosystem, Internet entities should have mechanisms to address domain name abuse, including receiving reports of abuse, handling abusive domain names, and complaining about misreported abuse. The best results can be achieved by joining all Internet entities to deal with abusive domain names.

Governments and Internet communities. As advocated by ICANN, establishing a suitable joint security organization to unify and coordinate the disposal of abusive domain names is one of the optimal methods. Each national government has its own police force to ensure social stability in the real world. Similarly, on the Internet, governments need to participate in the establishment of Internet security organizations, at least as the Chinese government engages in the reporting stage of domain name abuse.

Domain abuse reporters/researchers. While domain abuse reporters or researchers can report to all Internet entities involved in abusive domains without discrimination, this reporting mechanism can achieve the effect of abusive domains being handled, but not the optimal effect, while significantly increasing the workload of Internet entities and burdening them. Therefore, reporters should select the most appropriate Internet entity to report based on the characteristics of the abusive domains and the Internet entities, respectively.

6.3. Abusive Domain Reporting Investigation

We conducted a web survey regarding domain name abuse reporting at university. In total, 252 questionnaires were collected from individuals with a bachelor’s degree or higher, accounting for approximately 80% of the population. Almost 85% of them have seen inappropriate content such as pornography or gambling while browsing the web.

As shown in

Figure 12, nearly 57% of people do not know what reporting channels are available. About 17% were aware of the reporting channels provided by the administrative governance entity (e.g., 12377-Center). Even fewer people know about the reporting channels of other Internet entities, except for browsers. With most highly educated people who know less about reporting abusive domain names, let alone the common Internet user, using reports from the average Internet user to clean up abusive domain names on the Internet, such as pornography and gambling, will not be very effective.

Therefore, in order to better deal with the abusive domain names on the Internet, we suggest the following two aspects.

Governments or Internet communities. On the one hand, governments and Internet communities need to enhance knowledge dissemination and guidance to the public on reporting abusive domains. On the other hand, reporting abusive domain names should be friendly and straightforward. Our reporting process found that requiring too much evidence to be submitted is more likely to increase the burden on the reporter and that Internet entities still need to verify each reported domain. Finally, governments should make it clear what Internet entities should do to fight abusive domains and give them oversight and guidance.

Internet entities. The source of abusive domains cannot rely too heavily on abuse reports from the public. Internet entities should use their own resources to detect and discover abusive domain names more proactively. They should take up the responsibility and obligation of Internet security. For example, Han *** Fei, the registrant of domain m****p.cn, registered many other domains with the registrar Guangzhou Yunxun Information Technology Co. Then the registrar should take the initiative to verify the other domain names under that account and deal with the abusive domain names therein. Therefore, when Internet entities take the initiative to remove domains that use their resources for abusive attacks, reports of abusive domain names are relatively reduced, saving the time and effort that entities invest in handling abusive reports and improving their reputation.

6.4. Abusive Domain Name Blacklist Updates Lag

Internet entities, such as browsers or recursive DNS servers, often maintain a blacklist of abusive domain names and take action against domains if they are currently on the blacklist. Because domains change regularly (e.g., re-register after expiration) and are no longer abusive, the blacklist must determine when and how to update.

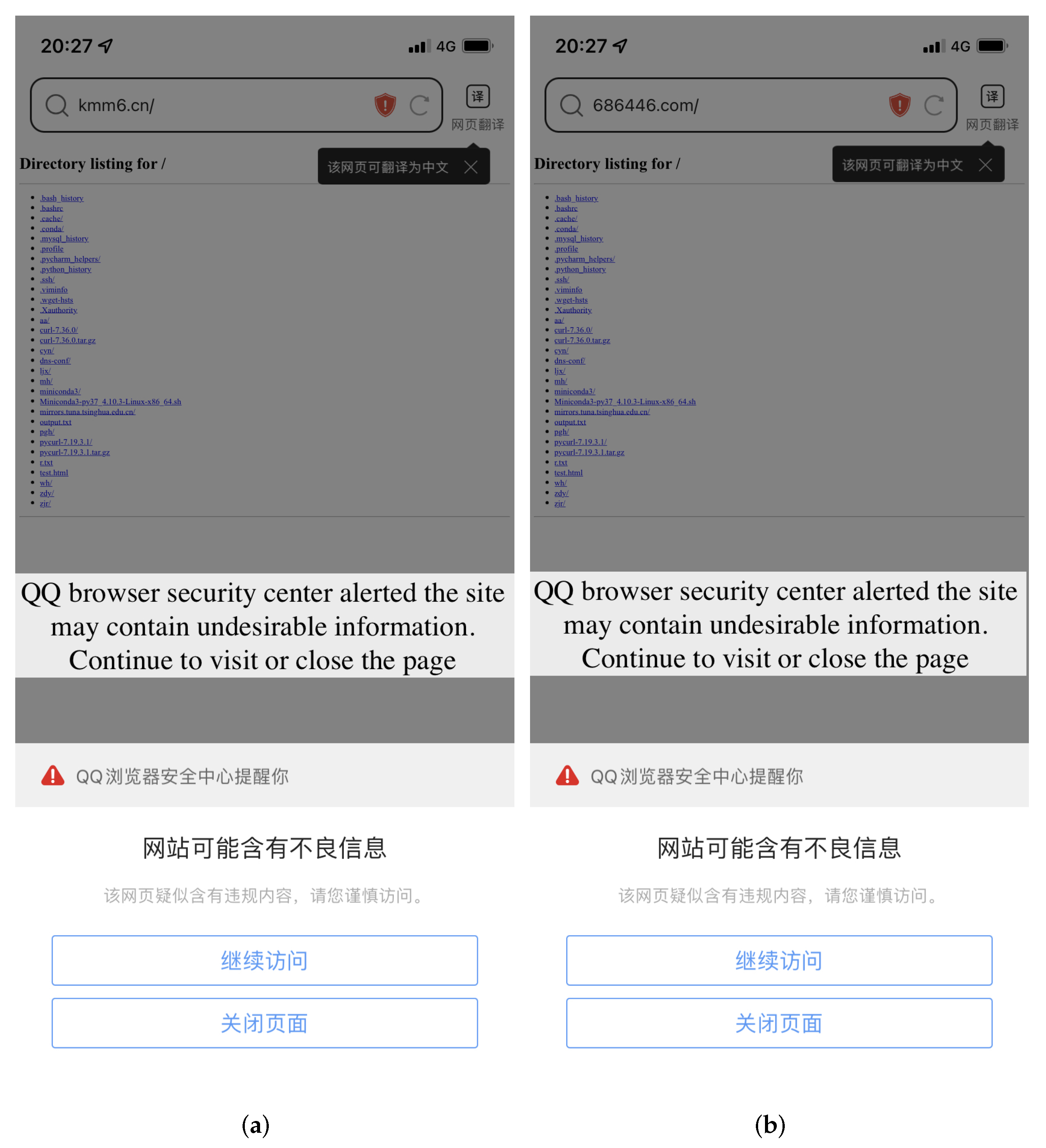

We did experiments to show that QQ Browser’s abusive domain blacklist does not get updated as quickly as it should. The domains 686446.com and kmm6.cn are both abusive domains and are blacklisted in the QQ browser, as shown in

Figure 13. After they expired, we registered these two domains with the registrar AliCloud. Then, we used the Python command (python3 -m http.server 80) to build a website and had the two domains associated with it. Finally, we then used the QQ browser to browse these two domains, and the result is shown in

Figure 14, where the browser still pops up the warning message. Moreover, it has been more than four months since these two domains were no longer abused.

As we can see from the above experiment, a delay in updating the blacklist of Internet entities will cause issues for domain owners and viewers, potentially resulting in economic losses for domain owners and causing customers to doubt the company’s reputation. Global Internet entities and domain name owners can refer to our research as follows.

Internet entities. From a technological standpoint, with the growing number of abusive domains on the Internet, the blacklist cannot be increased indefinitely, which will decrease the efficiency of matching abusive domains. Therefore, for Internet entities that use blocklists to block or deal with abusive domain names, the validity of the domain names in the blocklist needs to be proactively updated periodically.

Domain name owners. In order to prevent the newly registered domain names from being blocked because they were once malicious domain names, domain owners (registrants) can use malicious domain detection tools (e.g., Phishtank, Virustatal) to detect the domain name they want to register. In particular, when domain names are misclassified as abusive, the owner needs to file a complaint based on the information provided by the cyber entity as described in

Section 6.1.

6.5. Internet Entities Fail to Identify Abusive Domains

When we report abusive domain names to entities, they occasionally respond that the domain name is not abusive, is not utilizing their resources, or is inaccessible. This section summarizes the following reasons for Internet entities’ failure to identify abusive domain names.

The resources used by the abusive domain changed. The resource provider involved with the abusive domain name responds to our report after some time, such as 24 or 48 h. During this time, some resources may change, such as the IP address of the abused domain name, which would indicate a possible change in the web hosting provider. Therefore, the hosting provider that received our report informed us that the abusive domain name was not using its resources.

Domain name not accessible. One possibility is that by the time the Internet entity checks, the abusive domain has already been taken down and become unreachable. Another scenario we discovered was that the misused domain name was online but could not be accessed by the Internet entity’s ISP network. This could be because a specific ISP has addressed the abusive domain.

Abusive Domains masquerading as normal. Internet entities, such as registrars, have often informed us that the reported abusive domain names are normal. The primary reason for this is that when the security officer accesses the domain via a computer browser, the abusive domain either masquerades as a legitimate website (as illustrated in

Figure 15a) or simply returns a 404 page. However, when the security officer uses a mobile browser to view it, the exploited web content is shown (as shown in

Figure 15b). Additionally, several abusive domains display various online content depending on the day, such as normal websites during the day and pornographic websites at night. This effectively prevents security officers from inspecting and dealing with them during working hours.

Therefore, based on our experience in reporting abusive domains, we have summarized our recommendations for Internet entities and reporters as follows.

Domain abuse reporters. To enable Internet entities to deal with abusive domain names more quickly and efficiently, we suggest that reporters include additional features of abusive domain names in their reports, such as the requirement to access the domain name using a mobile browser, to enable security officers to do more accurate checks on abusive domain names. This can greatly improve the success rate of abuse reports and the effectiveness of dealing with abusive domain names.

Internet entities. Internet entities should reduce response time for abusive domains and be aware of common abusive domain masquerade strategies, which can significantly boost the efficiency of abusive domain handling.

6.6. Future Work

This paper focuses on evaluating Internet entities dealing with pornography and gambling domains. One limitation of our study is that other types of abusive domain names, such as phishing and malware, are not covered. However, the methods of Internet entities in dealing with abusive domain names are the same. As shown in

Figure 16, we reported phishing domains to the registrars, which handle abusive domains by setting the domain status to ClientHold. In the future, we will study other types of abusive domain names, such as phishing and malware. These abusive domain names with offensive behavior have more complex characteristics and require entities to have faster response times to them. On the other hand, we would like to analyze the operating model of the administrative governance entities in China and assess how much of a role they play in handling abusive domain names.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we present the first empirical study on the usability and effectiveness of Internet entities (i.e., 43 organizations across six categories of Internet entities) in receiving abusive reports and handling abusive domains. We discover that different Internet entities differ in the number of abusive domain names they handled and their response time. In addition, there are significant differences in the scale of user protection between the handling methods used by Internet entities. Moreover, abusive domain names may adopt escape techniques to evade handling depending on the features of the methods. In addition, there is room for further improvement in the entity’s approach to receiving reports, verifying the authenticity of reports, and handling abusive domains. All in all, the fight against abusive domains is not the fight of one person or organization but a battle that requires the entire community’s participation.