Cybersecurity in Smart Cities: Detection of Opposing Decisions on Anomalies in the Computer Network Behavior

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. The Kyoto 2006+ Dataset

2.2. Evaluation Processes and Performance Metrics

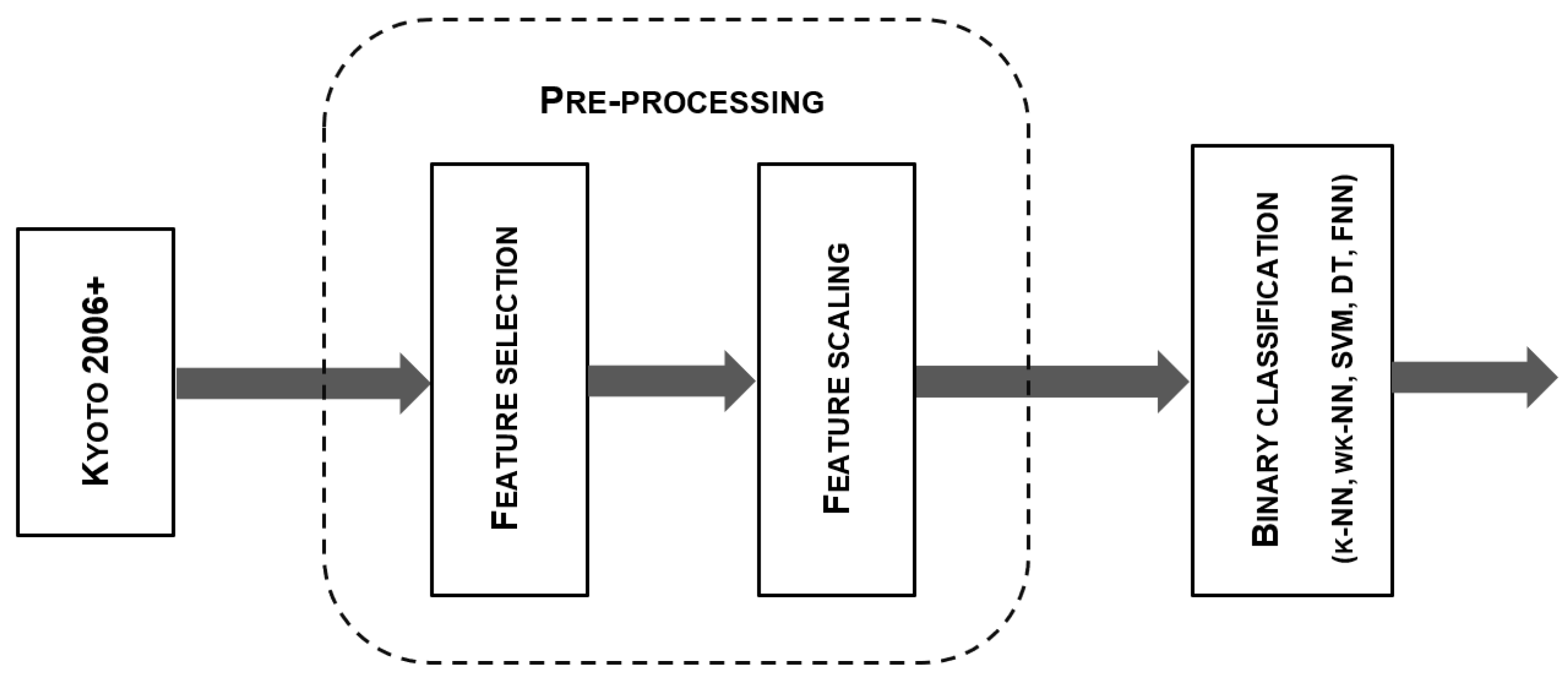

2.2.1. Pre-Processing Steps

2.2.2. Performance Metrics

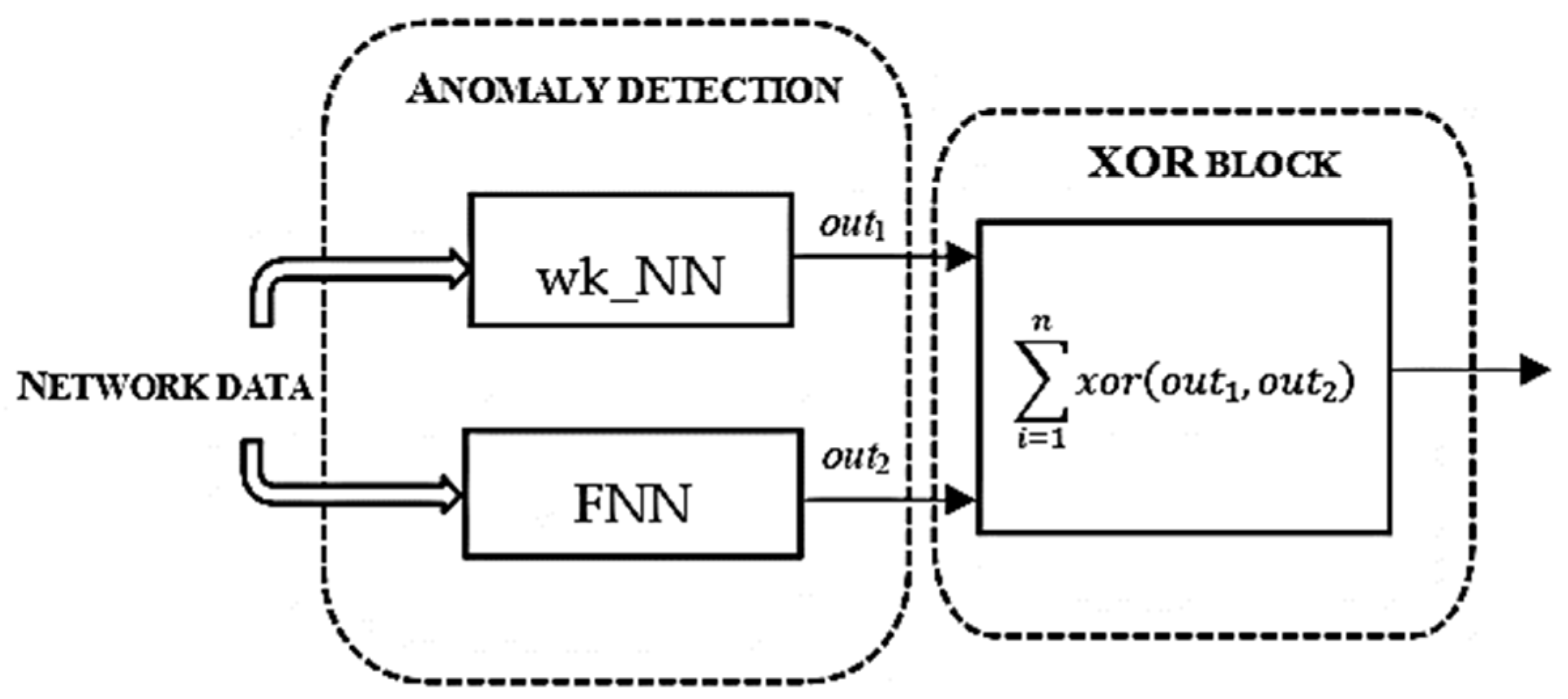

3. Proposed Work

4. Results and Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Fang, Y.; Shan, Z.; Wang, W. Modeling and key technologies of a data driven smart cities. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 91244–91258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Al-Saggaf, Y.; Zia, T. A data mining framework to predict cyber attack for cyber security. In Proceedings of the 15th IEEE Conference on Industrial Electronic and Applications, Kristiansand, Norway, 9–13 November 2020; pp. 207–212. [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan, R.; Gaur, L. Internet of Things: Approach and Applicability in Manufacturing; Chapman and Hall: London, UK; CRC: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaularachchi, Y. Implementing data driven smart city applications for future cities. Smart Cities 2022, 5, 455–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, N.; Al-Jaroodi, J.; Jawhar, I. Opportunities and challenges of data-driven cybersecurity for smart cities. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Systems Security Symposium, Crystal City, VA, USA, 1 July–1 August 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliyu, F.; Sheltami, T.; Deriche, M.; Nasser, N. Human immune-based intrusion detection and prevention system for fog computing. J. Netw. Syst. Manag. 2020, 30, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, J.; Methab, S. Machine Learning Applications in Misuse and Anomaly Detection. 2009. Available online: https://arxiv.org/ftp/arxiv/papers/2009/2009.06709.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- Bialas, A.; Michalak, M.; Flisiuk, B. Anomaly detection in network traffic security assurance. In Engineering in Dependability of Computer Systems and Networks; Zamojski, W., Mayurkiewicy, J., Sugier, J., Walkowiak, T., Kacprzyk, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; p. 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomani, O. A feature selection model for network intrusion detection system based on PSO, GWO, FFA and GA algorithms. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, M.H.; Bhattacharyya, D.K.; Kalita, J.K. Network anomaly detection: Methods systems and tools. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2014, 16, 303–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Gupta, S.; Arora, S. Research trends in network-based intrusion detection systems: A review. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 157761–157779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohara, B.; Bhuyan, J.; Wu, F.; Ding, J. A survey on the use of data clustering for intrusion detection system in cybersecurity. Int. J. Netw. Secur. Its Appl. 2020, 12, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, I.-C.; Chang, C.-C.; Peng, C.-H. An anomaly-based IDS framework using centroid-based classification. Symmetry 2022, 14, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protic, D.; Stankovic, M.; Antic, V. WK-FNN design for detection of anomalies in the computer network traffic. Facta Univ. Ser. Electron. Energetics 2022, 35, 269–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protic, D.; Stankovic, M. A hybrid model for anomaly-based intrusion detection in complex computer networks. In Proceedings of the 21st International Arab Conference on Information Technology (ACIT), Giza, Egypt, 28–30 November 2020; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protic, D.; Stankovic, M. Detection of anomalies in the computer network behaviour. Eur. J. Eng. Form. Sci. 2021, 4, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, I.; Shin, H.; Hong, M. Fast content-based file type identification. In Advances in Digital Forensics VII; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggieri, S. Complete search for feature selection decision trees. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2019, 20, 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, B.T.; Jaafari, A.; Avand, M.; Al-Ansari, N.; Du, T.D.; Yen, H.P.H.; Phong, T.V.; Nguyen, D.H.; Le, H.V.; Mafi-Gholami, D.; et al. Performance evaluation of machine learning methods for forest fire modeling and prediction. Symmetry 2020, 12, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardesty, L. Explained: Neural networks. MIT News, 14 April 2017. Available online: https://news.mit.edu/2017/explained-neural-networks-deep-learning-0414 (accessed on 11 July 2021).

- Yusof, N.N.M.; Sulaiman, N.S. Cyber attack detection dataset: A review. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2319, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Takakura, H.; Okabe, Y.; Eto, M.; Inoue, D.; Nakao, K. Statistical analysis of honeypot data and building of Kyoto 2006+ dataset for NIDS evaluation. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Building Analysis Datasets and Gathering Experience Returns for Security, Salzburg, Austria, 10–13 April 2011; pp. 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.; Marnerides, A.K.; Broadbent, M.; Race, N. Practical Intrusion Detection of Emerging Threat. Available online: https://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/id/eprint/156068/1/TNSM_Paper_Accepted_Version.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2022).

- Levenberg, K. A method for the solution of certain problems in least squares. Q. Appl. Math. 1944, 5, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquardt, D. An algorithm for least-squares estimation of nonlinear parameters. SIAM J. Appl. Math. 1963, 11, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, P.; Chen, Y.; Lu, M. Smart city information processing under internet of things and cloud computing. J. Supercomput. 2022, 78, 3676–3695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raza, S.; Wallgren, L.; Voigt, T. SVELTE: Real-time intrusion detection in the Internet of Things. Ad Hoc Netw. 2013, 11, 2661–2674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, R.; Omidkar, A.; Ahmadi Roudi, S.; Abbas, R.; Kim, S. Machine-learning enabled intrusion detection system for cellular connected UAV Networks. Electronics 2021, 10, 1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsheikh, M.A.; Lin, S.; Niyato, D.; Tan, H.P. Machine learning in wireless sensor networks: Algorithms, strategies, and applications. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2014, 16, 1996–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Y.V.; Kamatchi, K. Anomaly based network intrusion detection using ensemble machine learning technique. Int. J. Res. Eng. Sci. Manag. 2020, 3, 290–297. [Google Scholar]

- Pai, V.; Devidas, B.; Adesh, N.D. Comparative analysis of machine learning algorithms for intrusion detection. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1013, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ring, M.; Wunderlich, S.; Scheuring, D.; Landes, D.; Hotho, A.A. A survey of network-based intrusion detection data sets. Comput. Secur. 2019, 86, 147–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abiodun, O.I.; Jantan, A.; Omolara, A.E.; Dada, K.V.; Mohamed, N.A.; Arshad, H. State-of-the-art in artificial neural network applications: A survey. Heliyon 2018, 4, e00938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Band, S.S.; Ardabili, S.; Sookhak, M.; Chronopoulos, A.T.; Elnaffar, S.; Moslehpour, M.; Csaba, M.; Torok, B.; Pai, H.T.; Mosavi, A. When smart cities get smarter via machine learning: An in-depth literature review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 60985–61015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SIGKDD-KDD Cup. KDD Cup 1999: Computer Network Intrusion Detection. 2018. Available online: www.kdd.org (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- McCarthy, R. Network Analysis with the Bro Security Monitor. 2014. Available online: https://www.admin-magazine.com/Archive/2014/24/Network-analysis-with-the-Bro-Network-Security-Monitor (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Ambusaidi, M.A.; He, X.; Nanda, P.; Tan, Z. Building an intrusion detection system using a filter-based feature selection algorithm. IEEE Trans. Comput. 2016, 65, 2986–2998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bistron, M.; Piotrowsk, Z. Artificial intelligence applications in military systems and their influence on sense of security of citizens. Electronics 2021, 10, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maza, S.; Touahria, M. Feature selection algorithms in intrusion detection system: A survey. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2018, 12, 5079–5099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kousis, A.; Tjortjis, C. Data mining algorithms for smart cities: A bibliometric analysis. Algorithms 2021, 14, 242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, Y.G.; Park, K.; Kim, H.; Kim, J.; Hyun, S. Machine learning based intrusion detection systems for class imbalanced datasets. J. Korea Inst. Inf. Secur. Cryptol. 2017, 27, 1385–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawi, N.M.; Atomi, W.H.; Rehman, M.Z. The effect of data preprocessing on optimizing training on artificial neural network. Procedia Technol. 2013, 11, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, J.; Elisseff, A.; Schoelkopf, B.; Tipping, M. Use of the zero norm with linear models and kernel methods. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2003, 3, 1439–1461. [Google Scholar]

- Song, L.; Smola, A.; Gretton, A.; Borgwardt, K.; Bedo, J. Supervised feature selection via dependence estimation. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, 2007, Corvallis, OR, USA, 20–24 June 2007; Available online: http://www.gatsby.ucl.ac.uk/~gretton/papers/SonSmoGreetal07.pdf (accessed on 7 August 2022).

- Dy, J.G.; Brodley, C.E. Feature selection for unsupervised learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2005, 5, 845–889. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, P.; Murthy, C.A.; Pal, S. Unsupervised feature selection using feature similarity. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2002, 24, 301–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Liu, H. Semi-supervised feature selection via spectral analysis. In Proceedings of the SIAM International Conference on Data Mining, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 26–28 April 2007; pp. 641–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Jin, R.; Ye, J.; Lyu, M.; King, I. Discriminative semi-supervised feature selection via manifold regularization. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. 2010, 21, 1033–1047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Swathi, K.; Rao, B.B. Impact of PDS based kNN classifiers on Kyoto dataset. Int. J. Rough Sets Data Anal. 2019, 6, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhm, Y.; Pak, W. Service-aware two-level partitioning for machine learning-based network intrusion detection with high performance and high scalability. IEEE Access 2020, 9, 6608–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.P.; Kaur, A. Flower pollination algorithm for feature analysis of Kyoto 2006+ dataset. J. Inf. Optim. Sci. 2019, 40, 467–478. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia, S.; Luengo, J.; Herera, F. Data preparation basic models. In Data Preprocessing in Data Mining; Intelligent System Reference Library; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; Volume 72, pp. 39–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Imran, M.; Ripon, S.H. Network Intrusion Detection: An analytical assessment using deep learning and state-of-the-art machine learning models. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2021, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obaid, H.S.; Dheyab, S.A.; Sabry, S.S. The impact of data pre-processing techniques and dimensionality reduction on the accuracy of machine learning. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual Information Technology, Electromechanical Engineering and Microelectronics Conference (IEMECON), Jaipur, India, 13–15 March 2019; pp. 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khraisat, A.; Gondal, I.; Vamplew, P.; Kamruzzaman, J. Survey of intrusion detection systems: Techniques, datasets and challenges. Cybersecurity 2019, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferryian, A.; Thamrin, A.H.; Takeda, K.; Murai, J. Generating network intrusion detection dataset based on real and encrypted synthetic attack traffic. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 7868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, M.; Siavoshani, M.J.; Jahangir, A.H. A content-based deep intrusion detection system. Int. J. Inf. Secur. 2022, 21, 547–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, C.-F.; Hsu, Y.-F.; Lin, C.-Y.; Lin, W.-Y. Intrusion detection by machine learning. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 11994–12000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serkani, E.; Gharaee, H.; Mohammadzadeh, N. Anomaly detection using SVM as classifier and DT for optimizing feature vectors. ISeCure 2019, 11, 159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, A.; Islam, Z. AWST: A novel attribute weight selection technique for data clustering. In Proceedings of the 13th Australasian Data Mining Conference (AusDM 2015), Sydney, Australia, 8–9 August 2015; pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.A.; Islam, M.Z. CRUDAW: A novel fuzzy technique for clustering records following user defined attribute weights. In Proceedings of the Tenth Australasian Data Mining Conference (AusDM 2012), Sydney, Australia, 5–17 December 2012; Volume 134, pp. 27–42. [Google Scholar]

- Lampton, M. Damping-undamping strategies for Levenberg-Marquardt least-squares method. Comput. Phys. 2019, 11, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinov, I.D. Data Science and Predictive Analytics; Springer: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Allier, S.; Anquetil, N.; Hora, A.; Ducasse, S. A framework to compare alert ranking algorithms. In Proceedings of the 19th Working Conference on Reverse Engineering, 2012, Kingston, ON, Canada, 15–18 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, N.; Jin, P.; Wang, L.; Yang, X.; Liu, R.; Zhang, W.; Sui, K.; Pei, D. Automatically and adaptively identifying severe alerts for online service systems. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2020—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–9 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gaur, L.; Solanki, A.; Jain, V.; Khazanchi, D. Handbook of Research on Engineering Innovations and Technology Management in Organizations; ICI Global: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

| Authors | Year | Feature Selection/Feature Scaling | Classifiers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Band et al. [34] | 2022 | The most informative feature. Min-Max. | ANN, DT, SVM |

| Lin et al. [13] | 2022 | Point-biserial selection. Cluster-center scaling. | k-NN |

| Shresta et al. [28] | 2021 | Estimation efficiency reduction. Feature relevance. | DT, k-NN |

| Al-Imran and Ripon [53] | 2021 | 85 network flow features. Min-Max. | DT, k-NN |

| Kousis and Tjottjis [40] | 2021 | PCA. Normalization. | ANN, DT, k-NN, SVM |

| Pai et al. [31] | 2021 | Sequential search. Standardization | DT, SVM |

| Kumar et al. [11] | 2021 | PCA. | ANN, DT, k-NN, SVM |

| Protic and Stankovic [16] | 2021 | Numerical features selection. Min-Max. | DT, FNN, k-NN, SVM, wk-NN |

| Kumar et al. [30] | 2020 | ANOVA F-test, Z-score. | DT |

| Protic and Stankovic [15] | 2020 | Numerical features selection. Min-Max. | FNN, wk-NN |

| Obaid [54] | 2019 | PCA, Min-Max, Z-score. | DT |

| Ruggieri [18] | 2019 | Exact enumeration. | DT |

| Abiodun et al. [33] | 2018 | Estimation efficiency reduction. | ANN, FNN |

| Maza and Touharia [39] | 2018 | Incremental, decremental, random feature selection. | DT, SVM |

| Nawi et al. [42] | 2013 | Min-Max, Z-score. | ANN |

| Dataset | Year of Creation | Types of Attacks | Number of Features | Type of Traffic | Content of the Dataset |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ADFA | 2014 | Brute force, Java/Linux meterpreter, C100 webshell | 26 | Hybrid | Linux/Windows OS system call. |

| AWID | 2015 | Wi-fi 802.11 attacks | 156 | Emulated | Wireless LAN traffic. |

| CAIDA | 2007 | Distributed Denial of Service | Not used | Hybrid | Recorded on commercial backbone links from high speed monitors. |

| CIC-IDS-2017 | 2017 | Botnets, DDoS, Goldeneye, Hulk, HTTP | 80+ | Emulated | 5-day packet-based network traffic. |

| CIDDS-001 | 2017 | DoS, Bruteforce, Ping/Port Scan | 14 | Emulated | 4 weeks traffic form OpenStack and Ext. servers. |

| CSE-CIC-2018 | 2018 | FTP/SSH potator, Dos, DDoS, Web attacks, 1st/2nd level infiltration, botnet. | 80+ | Emulated | 10 days computer network traffic. |

| DARPA | 1998–1999 | DoS, R2L, U2R, probe | 41 | Emulated | 7 weeks of packet-based traffic. |

| IRSC | 2015 | DoS, R2U, surveillance | Not available | Hybrid | Sudans university network. |

| ISCX 2012 | 2012 | Infiltrating, DDoS, HTTP, SSH | 20 | Emulated | Packet-based traffic (7 days). |

| KDD Cup ‘99 | 1998 | Denial of Service, R2L, U2R, probing | 42 | Emulated | 5 weeks of packet-based traffic. |

| Kyoto 2006+ | 2006–2015 | Port scan, malware, shellcode, DoS | 24 | Real | 10 years of real network traffic. |

| NSL-KDD | 1998 | Denial of Service, R2L, U2R, probing | 42 | Emulated | KDD-Cup ‘99 dataset with redundant and duplicate records excluded. |

| UGR’16 | 2016 | Denial of Service, Portscans Botnet | 41 | Hybrid | Network traces were captured in tier-3 ISP for four months. |

| UNSW-NB15 | 2015 | Contemporary attacks behavior,. | 49 | Hybrid | tcpdump traces over 31 h. |

| No | Feature | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Duration | Connection duration [s]. |

| 2 | Service | Type of connection service. |

| 3 | Source bytes | # B sent by source IP address. |

| 4 | Destination bytes | # B sent by destination IP address. |

| 5 | Count | # of connections with same source/destination IP addresses to those of current connection in past 2s. |

| 6 | Same_srv_rate | % of connections to the same service in the feature Count |

| 7 | Serror_rate | % of connections that have ‘SYN’ errors in the feature Count. |

| 8 | Srv_error_rate | % of connections that have ‘SYN’ errors in Srv_count in past 2s. |

| 9 | Dst_host_count | Source/destination IP addresses are the same as the current connection (among past 100). |

| 10 | Dst_host_srv_count | The number of connections whose service type is also the same to that of the current connection. |

| 11 | Dst_host_same_src_port_rate | % of connections whose source port is the same to that of the current connection in Dst_host_count. |

| 12 | Dst_host_serror_rate | % of connections that have ‘SYN’ errors in Dst_host_count. |

| 13 | Dst_host_srv_serror_rate | % of connections that have ‘SYN’ errors in Dst_host_srv_count. |

| 14 | Flag | The state of the connection at the time of connection was written. |

| 15 | IDS_detection | Reflects if IDS triggered an alert for the connection. |

| 16 | Malware_detection | Indicates malware. |

| 17 | Ashula_detection | Shellcode and exploit codes were in the connection. |

| 18 | Label | Indicates an attack. |

| 19 | Source_IP_Address | Source IP address used in the session. |

| 20 | Source_Port_Number | Session’s source port number. |

| 21 | Destination_IP_Address | Also sanitized. |

| 22 | Destination_Port_Number | Session’s destination port number. |

| 23 | Start_time | Start of the session. |

| 24 | Duration | Session duration. |

| No | Type | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Statistical | 0.52 |

| 2 | Categorical | smtp |

| 3 | Statistical | 3333 |

| 4 | Statistical | 244 |

| 5 | Numeric | 1.00 |

| 6 | Numeric | 1.00 |

| 7 | Numeric | 0.00 |

| 8 | Numeric | 0.00 |

| 9 | Numeric | 6.00 |

| 10 | Numeric | 99.00 |

| 11 | Numeric | 0.00 |

| 12 | Numeric | 0.00 |

| 13 | Numeric | 0.00 |

| 14 | Statistical | SF |

| 15 | For further analysis | 0 |

| 16 | For further analysis | 0 |

| 17 | For further analysis | 0 |

| 18 | Numeric | 1 |

| 19 | Categorical | fdfd:c3e9:3c9c:264d:052b:4470:1f85:3407 |

| 20 | Categorical | 41339 |

| 21 | Categorical | fdfd:c3e9:3c9c:9f52:7d2e: 27ee:079e:0f3f |

| 22 | Categorical | 25 |

| 23 | Categorical | 00:00:36 |

| 24 | For further analysis | 0.523710 |

| Number of Instances | Model | ACC (9 Features) [%] | tp (9 Features) [s] | ACC (17 Features) [%] | tp (17 Features) [s] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 158,570 | k-NN | 98.3 | 275.72 | 99.0 | 1000.8 |

| wk-NN | 98.4 | 277.32 | 99.1 | 1019.15 | |

| DT | 97.2 | 3.8452 | 98.4 | 14.241 | |

| SVM | 98.1 | 449.35 | 98.4 | 467.7 | |

| 127,740 | k-NN | 98.2 | 193.82 | 98.6 | 682.07 |

| wk-NN | 98.1 | 194.81 | 98.8 | 690.58 | |

| DT | 97.2 | 3.3033 | 99.8 | 9.5367 | |

| SVM | 97.8 | 280.82 | 97.9 | 379.61 | |

| 80,807 | k-NN | 98.8 | 91.25 | 99.4 | 285.77 |

| wk-NN | 98.8 | 91.267 | 99.5 | 285.25 | |

| DT | 98.9 | 2..2615 | 99.4 | 6.2339 | |

| SVM | 97.9 | 227.28 | 98.1 | 125.25 | |

| 57,280 | k-NN | 99.4 | 43.734 | 99.6 | 129.99 |

| wk-NN | 99.5 | 43.272 | 99.6 | 130.88 | |

| DT | 99.4 | 1.7489 | 99.7 | 4.4535 | |

| SVM | 99.2 | 30.239 | 99.3 | 37.894 |

| TH | Min-Max[0,1] | Min-Max[−1,1] | Z-Score | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACC [%] | tp [s] | F1 [%] | FP | TPR | ACC [%] | tp [s] | F1 [%] | FP | TPR | ACC [%] | tp [s] | F1 [%] | FP | TPR | ACC [%] | tp [s] | F1 [%] | FP | TPR | |

| FNN DT SVM | 99.36 | 5 | 98.89 | 49 | 0.989 | 99.53 | 11 | 99.33 | 47 | 0.989 | 99.31 | 12 | 99.04 | 49 | 0.983 | 99.43 | 12 | 99.17 | 37 | 0.986 |

| 99.40 | 2.5 | 99.18 | 36 | 0.992 | 99.47 | 2.8 | 99.12 | 38 | 0.984 | 99.41 | 6.3 | 99.14 | 41 | 0.985 | 98.89 | 2.2 | 99.15 | 41 | 0.985 | |

| 99.10 | 26.9 | 98.69 | 64 | 0.980 | 99.15 | 36.9 | 98.93 | 63 | 0.981 | 99.17 | 43.4 | 98.89 | 65 | 0.989 | 99.22 | 36.3 | 98.88 | 62 | 0.981 | |

| k-NN | 99.30 | 56.1 | 99.01 | 54 | 0.984 | 99.45 | 107.4 | 99.21 | 53 | 0.992 | 99.41 | 103.2 | 99.20 | 53 | 0.986 | 99.43 | 102.4 | 99.11 | 58 | 0.985 |

| wk-NN | 99.40 | 56.3 | 99.16 | 60 | 0.989 | 99.48 | 102.7 | 99.26 | 56 | 0.993 | 99.58 | 105.3 | 99.29 | 47 | 0.989 | 99.48 | 103.2 | 99.26 | 58 | 0.986 |

| Instances | Different Decisions | Different Decisions [%] |

|---|---|---|

| 57,270 | 1160 | 6.1 |

| 57,280 | 460 | 2.4 |

| 58,300 | 100 | 0.5 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Protic, D.; Gaur, L.; Stankovic, M.; Rahman, M.A. Cybersecurity in Smart Cities: Detection of Opposing Decisions on Anomalies in the Computer Network Behavior. Electronics 2022, 11, 3718. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11223718

Protic D, Gaur L, Stankovic M, Rahman MA. Cybersecurity in Smart Cities: Detection of Opposing Decisions on Anomalies in the Computer Network Behavior. Electronics. 2022; 11(22):3718. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11223718

Chicago/Turabian StyleProtic, Danijela, Loveleen Gaur, Miomir Stankovic, and Md Anisur Rahman. 2022. "Cybersecurity in Smart Cities: Detection of Opposing Decisions on Anomalies in the Computer Network Behavior" Electronics 11, no. 22: 3718. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11223718

APA StyleProtic, D., Gaur, L., Stankovic, M., & Rahman, M. A. (2022). Cybersecurity in Smart Cities: Detection of Opposing Decisions on Anomalies in the Computer Network Behavior. Electronics, 11(22), 3718. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics11223718