Service Robots: A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

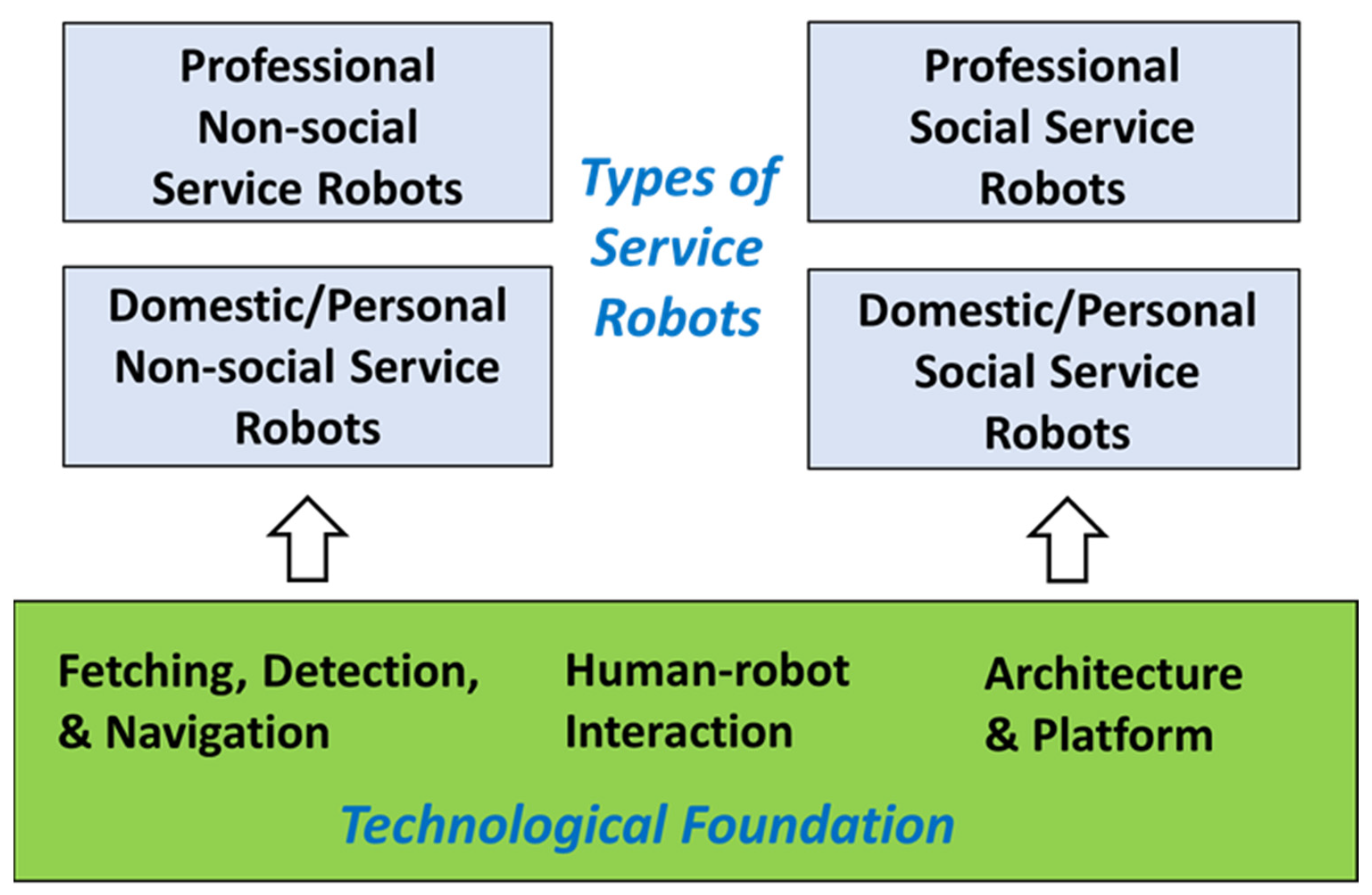

2. Methodology for Survey of Service Robot Research

2.1. Research Questions

- RQ1: What are the different categories of service robots?

- RQ2: What unique research topics have been addressed in each category?

- RQ3: What are the major technological foundations for service robots?

- RQ4: What are the challenges and opportunities in service robot research?

2.2. Search Process

2.3. Mandatory Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria and Quality Assessment

- –

- Only articles written in English were selected;

- –

- Scientific articles published in conferences, workshops, books, and journals were included;

- –

- Articles published before January 1999 were excluded.

2.4. Framework for Systematic Literature Review

2.5. Data Collection

- The source (journal/book/conference) and full reference including title and year

- The author(s) and their institution

- Category of the theme

- Research objectives

- Summary of the study including the main research questions and the answers

- Use cases

- Research methods

- Robot development models, methods, and techniques

- Types of experiments and experimental design

- Major findings

2.6. Preliminary Data Analysis

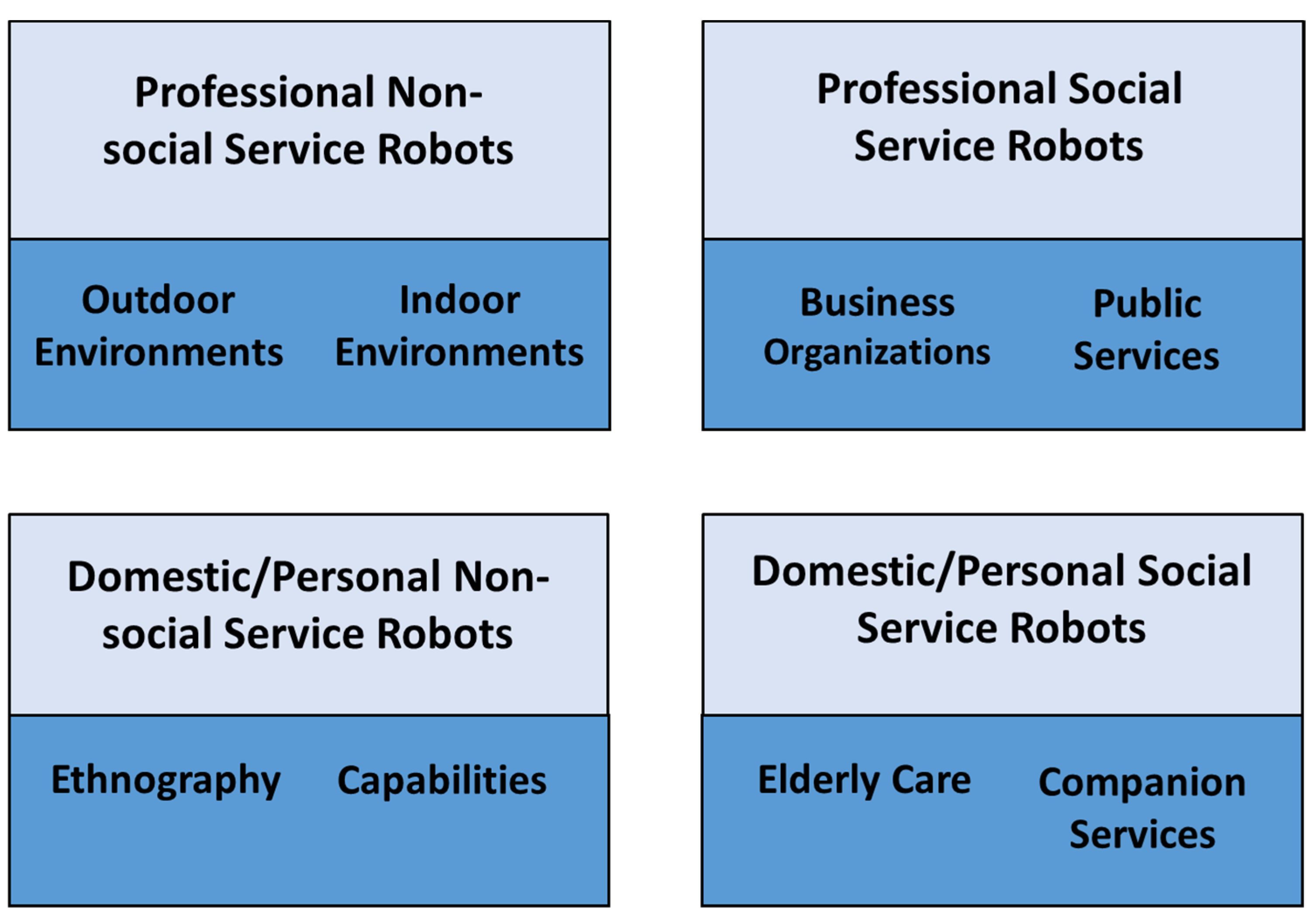

3. Professional Non-Social Service Robots

3.1. Professional Non-Social Robots in Outdoor Environments

3.2. Professional Non-Social Robots in Indoor Environments

4. Professional Social Service Robots

4.1. Professional Social Service Robots in Business Organizations

4.2. Professional Social Service Robots in Public Services

5. Domestic/Personal Non-Social Service Robots

5.1. Ethnography for Domestic/Personal Non-Social Service Robots

5.2. Capabilities of Domestic/Personal Non-Social Service Robots

6. Domestic/Personal Social Service Robots

6.1. Domestic/Personal Social Service Robots for Elderly Care

6.2. Domestic/Personal Social Service Robots for Companion Services

7. Technological Foundation of Service Robots

7.1. Fetching, Detection, and Navigation

7.2. Human-Robot Interaction

7.3. Architecture/Platform

8. Challenges and Opportunities of Service Robot Research

8.1. Safety

8.2. Security

8.3. Privacy

8.4. Ethics

9. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- McLeay, F.; Osburg, V.S.; Yoganathan, V.; Patterson, A. Replaced by a Robot: Service Implications in the Age of the Machine. J. Serv. Res. 2021, 24, 104–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Classification of Service Robots by Application Areas. Available online: https://ifr.org/img/office/Service_Robots_2016_Chapter_1_2.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2021).

- Wirtz, J.; Patterson, P.G.; Kunz, W.H.; Gruber, T.; Lu, V.N.; Paluch, S.; Martins, A. Brave new world: Service robots in the frontline. J. Serv. Manag. 2018, 29, 907–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belanche, D.; Casaló, L.V.; Flavián, C.; Schepers, J. Service robot implementation: A theoretical framework and research agenda. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 203–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Collins, G.R. Improving human–robot interactions in hospitality settings. Int. Hosp. Rev. 2020, 34, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Top Trends on the Gartner Hype Cycle for Artificial Intelligence. 2019. Available online: https://www.gartner.com/smarterwithgartner/top-trends-on-the-gartner-hype-cycle-for-artificial-intelligence-2019/ (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Decker, M.; Fischer, M.; Ott, I. Service Robotics and Human Labor: A first technology assessment of substitution and cooperation. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2017, 87, 348–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Marketsandmarkets Service Robotics Market by Environment, Type (Professional and Personal & Domestic), Component, Application (Logistics, Inspection & Maintenance, Public Relations, Marine, Entertainment, Education, & Personal), and Geography—Global Forecast to 2025. 2019. Available online: https://www.marketsandmarkets.com/Market-Reports/service-robotics-market-681.html (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Brookings Institution Brookings Survey Finds 52 Percent Believe Robots will Perform Most Human Activities in 30 Years. 2018. Available online: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2018/06/21/brookings-survey-finds-52-percent-believe-robots-will-perform-most-human-activities-in-30-years/ (accessed on 20 June 2021).

- Kim, S.S.; Kim, J.; Badu-Baiden, F.; Giroux, M.; Choi, Y. Preference for robot service or human service in hotels? Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 93, 102795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, G.; McCartney, A. Rise of the machines: Towards a conceptual service-robot research framework for the hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 3835–3851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, C.; Deveci, M.; Boltürk, E.; Türk, S. Fuzzy controlled humanoid robots: A literature review. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2020, 134, 103643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, V.N.; Wirtz, J.; Kunz, W.H.; Paluch, S.; Gruber, T.; Martins, A.; Patterson, P.G. Service robots, customers and service employees: What can we learn from the academic literature and where are the gaps? J. Serv. Theory Pract. 2020, 30, 361–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitchenham, B.; Brereton, O.P.; Budgen, D.; Turner, M.; Bailey, J.; Linkman, S. Systematic literature reviews in software engineering—A systematic literature review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2009, 51, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luk, B.L.; Cooke, D.S.; Galt, S.; Collie, A.A.; Chen, S. Intelligent legged climbing service robot for remote maintenance applications in hazardous environments. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2005, 53, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elkmann, N.; Felsch, T.; Sack, M.; Saenz, J.; Hortig, J. Innovative service robot systems for facade cleaning of difficult-to-access areas. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Lausanne, Switzerland, 30 September–4 October 2002; Volume 1, pp. 756–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, M.Y.; Hsieh, J.C.; Cheng, C.P. Design of an intelligent hospital service robot and its applications. In Proceedings of the 2004 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man and Cybernetics (IEEE Cat. No.04CH37583), The Hague, The Netherlands, 10–13 October 2004; Volume 5, pp. 4377–4382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.C.; Lai, C.C. Enriched Indoor Map Construction Based on Multisensor Fusion Approach for Intelligent Service Robot. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2012, 59, 3135–3145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andras, T.; Kovacs, L.; Bolmsjö, G.; Nikoleris, G.; Stepan, G. ACROBOTER: A Ceiling Based Crawling, Hoisting and Swinging Service Robot Platform. 23rd BCS Conference on Human Computer Interaction. 2009. Available online: https://portal.research.lu.se/portal/en/publications/acroboter-a-ceiling-based-crawling-hoisting-and-swinging-service-robot-platform(d298d25b-2b92-4891-9289-61ac7d76b646).html (accessed on 22 June 2021).

- Ondas, S.; Juhar, J.; Pleva, M.; Cizmar, A.; Holcer, R. Service Robot SCORPIO with Robust Speech Interface. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2013, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, W.; Kim, G.; Kim, M. Development of the multi-functional indoor service robot PSR systems. Auton. Robots 2007, 22, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Liu, R.; Zong, G. Realization of a Service Robot for Cleaning Spherical Surfaces. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2005, 2, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Scholl, K.-U.; Kepplin, V.; Berns, K.; Dillmann, R. An articulated service robot for autonomous sewer inspection tasks. In Proceedings of the 1999 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. Human and Environment Friendly Robots with High Intelligence and Emotional Quotients (Cat. No.99CH36289), Kyongju, Korea, 17–21 October 1999; Volume 2, pp. 1075–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraka, K.; Paiva, A.; Veloso, M. Expressive Lights for Revealing Mobile Service Robot State. In Robot 2015: Second Iberian Robotics Conference; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2016; pp. 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinillos, R.; Marcos, S.; Feliz, R.; Zalama, E.; Gómez-García-Bermejo, J. Long-term assessment of a service robot in a hotel environment. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2016, 79, 40–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Triebel, R.; Arras, K.; Alami, R.; Beyer, L.; Breuers, S.; Chatila, R.; Chetouani, M.; Cremers, D.; Evers, V.; Fiore, M.; et al. SPENCER: A Socially Aware Service Robot for Passenger Guidance and Help in Busy Airports. In Field and Service Robotics: Results of the 10th International Conference; Wettergreen, D.S., Barfoot, T.D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2016; pp. 607–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Qing-xiao, Y.; Can, Y.; Zhuang, F.; Yan-zheng, Z. Research of the Localization of Restaurant Service Robot. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2010, 7, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Q.; Yuan, C.; Fu, Z.; Zhao, Y. An autonomous restaurant service robot with high positioning accuracy. Ind. Robot Int. J. 2012, 39, 271–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-W.; Tseng, S.-P.; Kuan, T.-W.; Wang, J.-F. Outpatient Text Classification Using Attention-Based Bidirectional LSTM for Robot-Assisted Servicing in Hospital. Information 2020, 11, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, W.; Yueh, H.-P.; Wu, H.-Y.; Fu, L.-C. Developing a service robot for a children’s library: A design-based research approach. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2014, 65, 290–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behan, J.; O’Keeffe, D.T. The development of an autonomous service robot. Implementation: ‘Lucas’—The library assistant robot. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2008, 1, 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, H.-M.; Koenig, A.; Boehme, H.-J.; Schroeter, C. Vision-based Monte Carlo self-localization for a mobile service robot acting as shopping assistant in a home store. In Proceedings of the IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Lausanne, Switzerland, 30 September–4 October 2002; Volume 1, pp. 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.K.; Forlizzi, J.; Rybski, P.E.; Crabbe, F.; Chung, W.; Finkle, J.; Glaser, E.; Kiesler, S. The snackbot: Documenting the design of a robot for long-term human-robot interaction. In Proceedings of the 4th ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human Robot Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 9–13 March 2009; pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Kaber, D.B.; Zhu, B.; Swangnetr, M.; Mosaly, P.; Hodge, L. Service robot feature design effects on user perceptions and emotional responses. Intell. Serv. Robot. 2010, 3, 73–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, J.; Grinter, R.E.; Christensen, H.I. Domestic Robot Ecology. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2010, 2, 417–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, J.; Bauwens, V.; Kaplan, F.; Dillenbourg, P. Living with a Vacuum Cleaning Robot. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2013, 5, 389–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prassler, E.; Kosuge, K. Domestic Robotics. In Springer Handbook of Robotics; Siciliano, B., Khatib, O., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 1253–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palleja, T.; Tresanchez, M.; Teixido, M.; Palacin, J. Modeling floor-cleaning coverage performances of some domestic mobile robots in a reduced scenario. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2010, 58, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendriks, B.; Meerbeek, B.; Boess, S.; Pauws, S.; Sonneveld, M. Robot Vacuum Cleaner Personality and Behavior. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2011, 3, 187–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Forlizzi, J.; DiSalvo, C. Service robots in the domestic environment: A study of the roomba vacuum in the home. In Proceedings of the 1st ACM SIGCHI/SIGART Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 2–3 March 2006; pp. 258–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallivaara, I.; Haverinen, J.; Kemppainen, A.; Röning, J. Magnetic field-based SLAM method for solving the localization problem in mobile robot floor-cleaning task. In Proceedings of the 2011 15th International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR), Tallinn, Estonia, 20–23 June 2011; pp. 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verne, G.B. Adapting to a Robot: Adapting Gardening and the Garden to fit a Robot Lawn Mower. In Proceedings of the Companion of the 2020 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 23–26 March 2020; pp. 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Graaf, M.; Allouch, S.B.; van Dijk, J. Why Do They Refuse to Use My Robot? Reasons for Non-Use Derived from a Long-Term Home Study. In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction, New York, NY, USA, 6–9 March 2017; pp. 224–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaussard, F.; Fink, J.; Bauwens, V.; Rétornaz, P.; Hamel, D.; Dillenbourg, P.; Mondada, F. Lessons learned from robotic vacuum cleaners entering the home ecosystem. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2014, 62, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jayawardena, C.; Kuo, I.H.; Unger, U.; Igic, A.; Wong, R.; Watson, C.I.; Stafford, R.Q.; Broadbent, E.; Tiwari, P.; Warren, J.; et al. Deployment of a service robot to help older people. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Taipei, Taiwan, 18–22 October 2010; pp. 5990–5995. [Google Scholar]

- Portugal, D.; Alvito, P.; Christodoulou, E.; Samaras, G.; Dias, J. A Study on the Deployment of a Service Robot in an Elderly Care Center. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2019, 11, 317–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrich, N.; Bistry, H.; Zhang, J. Architecture and Software Design for a Service Robot in an Elderly-Care Scenario. Engineering 2015, 1, 027–035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bien, Z.Z.; Lee, H.-E.; Do, J.-H.; Kim, Y.-H.; Park, K.-H.; Yang, S.-E. Intelligent Interaction For Human-Friendly Service Robot in Smart House Environment. Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst. 2008, 1, 77–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.L.; Syrdal, D.S.; Ashgari-Oskoei, M.; Walters, M.L.; Dautenhahn, K. Social Roles and Baseline Proxemic Preferences for a Domestic Service Robot. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2014, 6, 469–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, H.-S.; Cho, S.-B. A modular design of Bayesian networks using expert knowledge: Context-aware home service robot. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 2629–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, H.M.R.T.; Muthugala, M.A.V.J.; Jayasekara, A.G.B.P.; Chandima, D.P. Cognitive Spatial Representative Map for Interactive Conversational Model of Service Robot. In Proceedings of the 2018 27th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), Nanjing, China, 27–31 August 2018; pp. 686–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedaf, S.; Draper, H.; Gelderblom, G.-J.; Sorell, T.; de Witte, L. Can a Service Robot Which Supports Independent Living of Older People Disobey a Command? The Views of Older People, Informal Carers and Professional Caregivers on the Acceptability of Robots. Int. J. Soc. Robot. 2016, 8, 409–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrer, G.; Garrell, A.; Sanfeliu, A. Robot companion: A social-force based approach with human awareness-navigation in crowded environments. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Tokyo, Japan, 3–7 November 2013; pp. 1688–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dautenhahn, K.; Woods, S.; Kaouri, C.; Walters, M.L.; Koay, K.L.; Werry, I. What is a robot companion—Friend, assistant or butler? In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Edmonton, AB, Canada, 2–6 August 2005; pp. 1192–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ekvall, S.; Kragic, D.; Jensfelt, P. Object detection and mapping for service robot tasks. Robotica 2007, 25, 175–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althaus, P.; Ishiguro, H.; Kanda, T.; Miyashita, T.; Christensen, H.I. Navigation for human-robot interaction tasks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, 2004, Proceedings, ICRA ’04. 2004, New Orleans, LA, USA, 26 April–1 May; 2004; Volume 2, pp. 1894–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pyo, Y.; Nakashima, K.; Kuwahata, S.; Kurazume, R.; Tsuji, T.; Morooka, K.I.; Hasegawa, T. Service robot system with an informationally structured environment. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2015, 74, 148–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jung, E.-J.; Lee, J.H.; Yi, B.-J.; Park, J.; Yuta, S.; Noh, S.-T. Development of a Laser-Range-Finder-Based Human Tracking and Control Algorithm for a Marathoner Service Robot. IEEEASME Trans. Mechatron. 2014, 19, 1963–1976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieuwenhuisen, M.; Droeschel, D.; Holz, D.; Stückler, J.; Berner, A.; Li, J.; Klein, R.; Behnke, S. Mobile bin picking with an anthropomorphic service robot. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Karlsruhe, Germany, 6–10 May 2013; pp. 2327–2334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-J.; Li, T.-H.S.; Kuo, P.-H.; Wang, Y.-H. Integrated particle swarm optimization algorithm based obstacle avoidance control design for home service robot. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2016, 56, 748–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Tian, G.; Li, Y.; Zhou, F.; Duan, P. Spatial semantic hybrid map building and application of mobile service robot. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2014, 62, 923–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khaliq, A.A.; Saffiotti, A. Stigmergy at work: Planning and navigation for a service robot on an RFID floor. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 25–30 May 2015; pp. 1085–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, G.; Chung, W. Navigation Behavior Selection Using Generalized Stochastic Petri Nets for a Service Robot. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. Part C Appl. Rev. 2007, 37, 494–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, F.G.; Abbenseth, J.; Henkel, C.; Dörr, S. A predictive online path planning and optimization approach for cooperative mobile service robot navigation in industrial applications. In Proceedings of the 2017 European Conference on Mobile Robots (ECMR), Paris, France, 6–8 September 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halme, A.; Leppänen, I.; Suomela, J.; Ylönen, S.; Kettunen, I. WorkPartner: Interactive Human-Like Service Robot for Outdoor Applications. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2003, 22, 627–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, M.; Zhang, K.; Roth, A.M.; Rhodes, T.; Schmucker, R.; Zhou, C.; Ferreira, S.; Cartucho, J.; Veloso, M. Towards a Robust Interactive and Learning Social Robot. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Autonomous Agents and MultiAgent Systems, Stockholm Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Böhme, H.-J.; Wilhelm, T.; Key, J.; Schauer, C.; Schröter, C.; Groß, H.M.; Hempel, T. An approach to multi-modal human–machine interaction for intelligent service robots. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2003, 44, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, K.W.; Kim, H.-R.; Yoon, W.C.; Yoon, Y.-S.; Kwon, D.-S. Designing a human-robot interaction framework for home service robot. In Proceedings of the ROMAN 2005. IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Nashville, TN, USA, 13–15 August 2005; pp. 286–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwon, D.-S.; Kwak, Y.K.; Park, J.C.; Chung, M.J.; Jee, E.S.; Park, K.S.; Kim, H.R.; Kim, Y.M.; Park, J.C.; Kim, E.H.; et al. Emotion Interaction System for a Service Robot. In Proceedings of the ROMAN 2007—The 16th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Jeju, Korea, 26–29 August 2007; pp. 351–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Droeschel, D.; Stückler, J.; Holz, D.; Behnke, S. Towards joint attention for a domestic service robot—Person awareness and gesture recognition using Time-of-Flight cameras. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 1205–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, I.-J.; Lin, R.-Z.; Lin, Z.-Y. Service robot system with integration of wearable Myo armband for specialized hand gesture human–computer interfaces for people with disabilities with mobility problems. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2018, 69, 815–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.C.; Wu, Y.-C. Hand gesture recognition for Human-Robot Interaction for service robot. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Multisensor Fusion and Integration for Intelligent Systems (MFI), Hamburg, Germany, 13–15 September 2012; pp. 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bien, Z.Z.; Lee, H.-E. Effective learning system techniques for human-robot interaction in service environment. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2007, 20, 439–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacchierotti, E.; Christensen, H.I.; Jensfelt, P. Human-robot embodied interaction in hallway settings: A pilot user study. In Proceedings of the ROMAN 2005. IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication, Nashville, TN, USA, 13–15 August 2005; pp. 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breuer, T.; Macedo GR, G.; Hartanto, R.; Hochgeschwender, N.; Holz, D.; Hegger, F.; Jin, Z.; Müller, C.; Paulus, J.; Reckhaus, M.; et al. Johnny: An autonomous service robot for domestic environments. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2012, 66, 245–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reiser, U.; Connette, C.; Fischer, J.; Kubacki, J.; Bubeck, A.; Weisshardt, F.; Jacobs, T.; Parlitz, C.; Hägele, M.; Verl, A. Care-O-bot® 3—Creating a product vision for service robot applications by integrating design and technology. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, St. Louis, MO, USA, 10–15 October 2009; pp. 1992–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puigbo, J.-Y.; Pumarola, A.; Angulo, C.; Tellez, R. Using a cognitive architecture for general purpose service robot control. Connect. Sci. 2015, 27, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Datta, C.; Jayawardena, C.; Kuo, I.H.; MacDonald, B.A. RoboStudio: A visual programming environment for rapid authoring and customization of complex services on a personal service robot. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 2352–2357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delgado, R.; You, B.-J.; Choi, B.W. Real-time control architecture based on Xenomai using ROS packages for a service robot. J. Syst. Softw. 2019, 151, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zieliński, C.; Szynkiewicz, W.; Winiarski, T.; Staniak, M.; Czajewski, W.; Kornuta, T. Rubik’s cube as a benchmark validating MRROC++ as an implementation tool for service robot control systems. Ind. Robot Int. J. 2007, 34, 368–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemueller, T.; Lakemeyer, G.; Srinivasa, S.S. A generic robot database and its application in fault analysis and performance evaluation. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems, Vilamoura-Algarve, Portugal, 7–12 October 2012; pp. 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Quigley, M.; Conley, K.; Gerkey, B.; Faust, J.; Foote, T.; Leibs, J.; Berger, E.; Wheeler, R.; Ng, A. ROS: An open-source Robot Operating System. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Kobe, Japan, 12–17 May 2009; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Sanfeliu, A.; Hagita, N.; Saffiotti, A. Network robot systems. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2008, 56, 793–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berenson, D.; Abbeel, P.; Goldberg, K. A robot path planning framework that learns from experience. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Saint Paul, MN, USA, 14–18 May 2012; pp. 3671–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhong, J.; Ling, C.; Cangelosi, A.; Lotfi, A.; Liu, X. On the Gap between Domestic Robotic Applications and Computational Intelligence. Electronics 2021, 10, 793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaronga, E.F.; Golia, A.J. Robots, standards and the law: Rivalries between private standards and public policymaking for robot governance. Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2019, 35, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J. Artificial intelligence: Implications for the future of work. Am. J. Ind. Med. 2019, 62, 917–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galin, R.; Meshcheryakov, R. Review on Human-Robot Interaction During Collaboration in a Shared Workspace. In Interactive Collaborative Robotics; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2019; pp. 63–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, W.; Xu, K.; Wang, D. An Anti-Tracking Source-Location Privacy Protection Protocol in WSNs Based on Path Extension. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014, 1, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharkey, A.; Sharkey, N. Granny and the robots: Ethical issues in robot care for the elderly. Ethics Inf. Technol. 2012, 14, 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, P.; Abney, K.; Bekey, G. Robot ethics: Mapping the issues for a mechanized world. Artif. Intell. 2011, 175, 942–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chavhan, S.; Doriya, R. Secured Map Building using Elliptic Curve Integrated Encryption Scheme and Kerberos for Cloud-based Robots. In Proceedings of the 2020 Fourth International Conference on Computing Methodologies and Communication (ICCMC), Erode, India, 11–13 March 2020; pp. 157–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutz, C.; Tamò-Larrieux, A. The Robot Privacy Paradox: Understanding How Privacy Concerns Shape Intentions to Use Social Robots. Hum. -Mach. Commun. J. 2020, 1, 87–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lutz, C.; Schöttler, M.; Hoffmann, C.P. The privacy implications of social robots: Scoping review and expert interviews. Mob. Media Commun. 2019, 7, 412–434. Available online: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/2050157919843961?journalCode=mmca (accessed on 21 September 2021). [CrossRef]

- Van Maris, A.; Zook, N.; Caleb-Solly, P.; Studley, M.; Winfield, A.; Dogramadzi, S. Designing Ethical Social Robots—A Longitudinal Field Study With Older Adults. Front. Robot. AI 2020, 7, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sullins, J.P. Robots, Love, and Sex: The Ethics of Building a Love Machine. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput. 2012, 3, 398–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejia, C.; Kajikawa, Y. Using acknowledgement data to characterize funding organizations by the types of research sponsored: The case of robotics research. Scientometrics 2018, 114, 883–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, H.; Li, M.; Shu, B.; Bai, B. Enhancing hospitality experience with service robots: The mediating role of rapport building. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2020, 29, 247–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, Z.H.; Siddique, A.; Lee, C.W. Robotics Utilization for Healthcare Digitization in Global COVID-19 Management. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Haro, J.M.; Oña, E.D.; Hernandez-Vicen, J.; Martinez, S.; Balaguer, C. Service Robots in Catering Applications: A Review and Future Challenges. Electronics 2021, 10, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhong, L.; Chen, T.; Chen, J.; Yu, Y. Three-Stream Convolutional Neural Network with Squeeze-and-Excitation Block for Near-Infrared Facial Expression Recognition. Electronics 2019, 8, 385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Journal/Book/Conference Title | |

|---|---|

| 1 | Robot. Auton. Syst. |

| 2 | IEEE/RSJ International Conference |

| 3 | IEEE Trans. |

| 4 | BCS Conf |

| 5 | Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst |

| 6 | Auton. Robots |

| 7 | Iberian Robotics Conference |

| 8 | Springer International Publishing |

| 9 | Ind. Robot Int. J. |

| 10 | Information |

| 11 | J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. |

| 12 | Intell. Serv. Robot |

| 13 | ACM/IEEE international conference |

| 14 | Int. J. Soc. Robot |

| 15 | Springer Handbook of Robotics |

| 16 | ACM SIGCHI/SIGART conference |

| 17 | International Conference on Advanced Robotics (ICAR) |

| 18 | Engineering |

| 19 | Int. J. Comput. Intell. Syst |

| 20 | Expert Syst. Appl |

| 21 | IEEE International Symposium |

| 22 | Robotica |

| 23 | IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation |

| 24 | IEEEASME Trans |

| 25 | Comput. Electr. Eng |

| 26 | European Conference on Mobile Robots |

| 27 | Int. J. Robot. Res |

| 28 | AAMAS |

| 29 | IEEE International Workshop |

| 30 | IEEE International Conference on Multisensor Fusion and Integration for Intelligent Systems |

| 31 | Knowl.-Based Syst |

| 32 | J. Intell. Robot. Syst |

| 33 | Connect. Sci. |

| 34 | J. Syst. Softw |

| 99 | 00 | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 8 | |||||||||||||||

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 10 | ||||||||||||||

| 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 10 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 11 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 12 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 13 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||

| 15 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 16 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 17 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 18 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 19 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 20 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 21 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 22 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 23 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 6 | ||||||||||||||||

| 24 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 25 | 1 | 1 | 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 26 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 27 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 28 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 29 | 2 | 2 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 30 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 31 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 32 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 33 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 34 | 1 | 1 | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Select Paper | Purpose | Key Features | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Luk et al. [16] | Develop a legged climbing robot for unstructured and rough terrain. | Tactile and ultrasonic sensing; A set of reflexive rules; A fuzzy control method | The developed method allowed for smooth and accurate robot motions and enhanced the walking and climbing activities. |

| Elkmann et al. [17] | Explore feasibilities for robots to engage in facade cleaning. | A range of motion systems for walking, wheeled, and balloon-based robots | Facade cleaning robot cleaned the vaulted glass hall of the Leipzig Trade Fair in Germany. |

| Shieh et al. [18] | Develop an intelligent hospital service robot. | Collision-free navigation path planning with nine ultrasonic sensors installed to assess the distances between the service robot and obstacles | The simulation showed that the robot can accomplish navigation control in the hospital environment. |

| Luo and Lai [19] | Develop an intelligent service robot that can roughly calculate the environmental structure and detect the symbols/signs in the building. | Multisensor fusion techniques; An improved alignment technique | The concept was proved with an information-enriched map. |

| Andras et al. [20] | Design an indoor service robot locomotion technology. | Platform with mechanical, navigational, and control subsystems | The viability of the indoor locomotion technology was proved. |

| Ondas et al. [21] | Develop a small service robot performing in teleoperator mode. | Speech interface based on acoustic models; A small-vocabulary language model | The proposed approach performed the best when the background noise is mostly stationary. |

| Chung et al. [22] | Achieve system integration, multi-functionality, and autonomy under environmental uncertainties. | Modular and reconfigurable hardware components; Navigation system with range sensors; Path planning based on Konolige’s gradient method | The public service robot systems accomplished a delivery, a patrol, a guide, and a floor cleaning task. |

| Zhang et al. [23] | Propose an auto-climbing robot that can clean the spherical surface. | An intelligent control system based on 6 parts, five controller area network (CAN) control nodes, and a remote controller | The experimental results confirmed the robot’s ability to clean the spherical surface. |

| Scholl et al. [24] | Develop a prototype multijoint, autonomous sewer robot. | A distributed hardware architecture with microcontrollers; Sensors to control the joints of the robot; A camera-based system; The robot control system | The robot followed a path with a given speed and adapted the drive segments to the ground. |

| Baraka et al. [25] | Investigate the use of lights to visualize the robot’s state. | Lights as a medium of robot-human communication to reveal the internal state of the robot | The results showed that a small set of visualization designs can be considered valid. |

| Select Paper | Purpose | Key Features | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pinillos et al. [26] | Assess the robot’s capabilities as a bellboy in a hotel for guiding the guests and providing hotel/city information and hotel-related services. | Three-stage assessment methodology (data collection, analysis, redesign) with the continuous and automated measurement of metrics regarding navigation and interaction with guests | Following the extensive experimentations, guidelines are derived to integrate social service robots into daily life. |

| Triebel et al. [27] | Present a socially compliant mobile robot platform developed in the EU-funded project SPENCER. | The platform with the map representation, the task and motion planner, and the laser-based people and group tracker | The robot can engage with a person and guide the person or a group to the goal. |

| Qing-xiao et al. [28] | Design a restaurant service robot that provides basic services. | Landmarks positioning and localization algorithms, optical character recognition technology, and Radio Frequency Identification(RFID)-based localization algorithm | The restaurant service robot realized real-time self-localization using the algorithms. |

| Yu et al. [29] | Present segmented positioning and object tracking methods. | Two manipulators with three free degrees, the segmented positioning procedure, and object tracking procedure | The service robot achieved self-localization and grasped the plate on the pantry table. |

| Chen et al. [30] | Develop an attention-based bidirectional long short-term memory (Att-BiLSTM) model for service robots to classify outpatient categories. | Natural language processing; Long-short term memory deep learning model | The robot system based on Att-BiLSTM showed 96% accuracy. |

| Lin et al. [31] | Develop a library robot for locating resources in libraries. | Anthropomorphic features; Rapid prototyping; Iterative cycles of design and observation | The robot was effective in helping child patrons in locating resources. |

| Behan and O’Keeffe [32] | Develop an autonomous robotic aid to help users in a library. | Localization techniques wth image processing integrated with sonar data and odometry; The human-robot interaction system | All interacting users thought the robot was functioning successfully within the given environment. |

| Gross et al. [33] | Develop a view-based robot self-localization approach. | The omnivision system; probabilistic Monte Carlo localization (MCL) | The view-based localization approach seems to be computationally efficient and robust. |

| Lee et al. [34] | Present the design of Snackbot, a snack delivery robot, at CMU buildings. | A semi-autonomous semi-humanoid robot | Lessons include developing the robot holistically and as a product and a service, and in a way that evokes social behavior. |

| Zhang et al. [35] | Investigate the effect of service robot interfaces on perceptions and emotional responses of the elderly. | Design of facial configuration, voice messaging, and interactivity | Anthropomorphic and interactive features of service robots induce positive emotional responses. |

| Select Paper | Purpose | Key Features | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| ung et al. [36] | Develop a domestic robot ecology framework. | The framework with three key attributes: physical and social space, social actors, and intended tasks | Found how people accepted robots as a part of the households through four temporal stages: re-adoption, adoption, adaptation, and use/retention. |

| Fink et al. [37] | Investigate the adoption of domestic robots and their niches. | A 6-month ethnographic study with nine households given a Roomba vacuum cleaning | Only three out of the nine households durably adopted the robot. |

| Prassler and Kosuge [38] | Survey the technologies in domestic robotics, smart appliances, and smart homes. | An overview of domestic cleaning robots for windows, lawn-mowing, floors, and pools robots | The acceptance of a domestic robot is dependent on not only the engineers’ ingenuity but also the customers’ needs, expectations, and willingness to pay. |

| Palleja et al. [39] | Model floor-cleaning coverage performances of domestic random path planning robots. | Performances of three commercial floor-cleaning mobile robots and one research prototype are analyzed. | An algorithm based on random path planning assures complete coverage of a closed area but results in an over-cleaning. |

| Hendriks et al. [40] | Investigate the personality of a robot vacuum cleaner that users desire. | A semi-structured interview was done with six participants to find out the personality of a robot vacuum cleaner that users desire. | The evaluation showed that users recognized the intended personality of the robot. Once users know the personality of their robot, they can interact appropriately and predict how the robot responds. |

| Forlizzi & DiSalvo [41] | Present an ethnographic study on the use of the Roomba vacuum. | A four-month ethnographic study with 14 semi-structured interviews and home tours with individuals, couples, and families | The results showed how the technology is introduced is critical, how the use of such technology becomes social, and how homes of the future must adapt to future products. |

| Vallivaara et al. [42] | Present a Simultaneous Localization and Mapping(SLAM) method based on indoor magnetic field anomalies. | Gaussian Processes and a Rao-Blackwellized Particle Filter | The proposed method can be used to acquire accurate maps for the robot coverage problem and reduce over-cleaning. |

| Verne [43] | Explore how a garden works and the garden changes with the introduction of a robotic lawn mower. | Autoethnography to evaluate personal experiences and thoughts | On top of its primary tasks, the robot mower reveals much wider consequences. Unwanted changes are important for user acceptance or rejection of robots. |

| de Graaf et al. [44] | Provide insight into the reasons people refused or abandoned the use of a robot. | 70 autonomous robots were placed at people’s homes for six months and questionnaires and interviews were conducted to understand reasons for refusal and abandonment of the robot. | Robot designers need to create robots that are enjoyable and easy to use to capture users in the short term, and functionally relevant to keep those users in the longer term. |

| Vaussard et al. [45] | Evaluate the suitability of domestic robotic vacuum cleaners for their daily domestic tasks. | An ethnographic study and an analysis of the influence of key technologies on performance to understand how well a robot accomplishes its task. | The question “can a robot be a drop-in replacement to accomplish domestic tasks?” cannot be answered out of the box. The answer mostly depends on how the robot is used. |

| Select Paper | Purpose | Key Features | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jayawardena et al. [46] | Assess users’ interaction with an older care robot to determine which human and robot factors predict a successful human-robot interaction. | The robot consists of a tiltable head, rotatable torso, a mobile platform with ultrasonic sensors, and several medical service modules. | 53 volunteers from a retirement village gave the robot overall high ratings as well as satisfactory ratings in each service module. |

| Portugal et al. [47] | Develop an appealing indoor mobile robot and provide effective and advanced user–robot interaction. | A modular robotic architecture allowing easy addition of new components; An innovative and affordable social robotic platform for advanced and useful human-robot interaction | The users suggest that the robot could be more human-like. However, it remains uncertain if the elderly necessarily look for increased animacy in a social robot. |

| Hendrich et al. [48] | Describe the engineering aspects of the service robot with advanced manipulation capabilities. | Data from multiple sources are integrated into the middleware layer; The configuration planner coordinates the system and the robots. | A field test with 70 elderly users showed that the usability and acceptability scores for the robot and the overall system are positive. |

| Bien et al. [49] | Present a framework for a human–robot interaction (HRI) module with a range of computational intelligence techniques. | Interaction is considered as input and output of the HRI module and the robotic response is a system output in crisp context, fuzzy context, and uncertain context. | A successful example of human-robot interaction was given for each of the three contexts. |

| Koay et al. [50] | Develop socially acceptable behavior for a domestic robot in a situation where a user and the robot interact with each other in the proximity of the same physical space. | A live HRI study in a home setting using the human-scaled but non-humanoid Care-O-bot®3. | The way a robot presents itself or is presented by others and to the user significantly affects proxemic preferences as well as the users’ ability to process its signals in early interactions. |

| Park and Cho [51] | Propose a systematic modeling approach for several Bayesian networks. | Bayesian networks to supplement uncertain sensor input; Modular design approach based on domain knowledge | Performance was good in every service test case and the system usability scale test for a subjective evaluation of the reasoning modules is satisfactory. |

| Bandara et al. [52] | Develop a method to improve the interaction between the user and the robot via bidirectional communication. | Conversation management module (CMM); spatial information processor (ISP); cognitive map creator (CMC) | The robot was able to have interactive conversations with the user. |

| Bedaf et al. [53] | Explore the areas of tension that a re-enablement coach robot can cause. | Scenario-based focus group sessions with older people, informal care takers, and care professionals in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, and France | Older people-users may prefer autonomy over promotion of independence. |

| Ferrer et al. [54] | Present a novel robot companion approach based on the social force model (SFM). | A unified navigation framework comprised of a general social interaction model based on the SFM, a pedestrian detector system, and a prediction algorithm to estimate the best-suited destination for a person. | The validation of the model was demonstrated with an extensive set of simulations and real-life experiments in an urban area. |

| Dautenhahn et al. [55] | Explore people’s perceptions and attitudes towards a future domestic robot companion. | The analysis of questionnaire data regarding people’s perceptions and attitudes towards a robot before and after human-robot interaction trials | People frequently cited that they would like a future robot to play the role of a servant which is similar to the human ‘butler’ role. |

| Select Paper | Use Case | Purpose | Techniques | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ekvall et al. [56] | Object detection and mapping | Integrate SLAM and object detection/recognition methods. | SLAM; receptive field cooccurrence histograms (RFCH); scale-invariant features (SIFT) | The object detection method could successfully detect objects in cluttered scenes. |

| Althaus et al. [57] | A humanoid system on wheels called Roboviethe engaging in discussion with a group of people and continuing navigation | Present a state diagram that incorporates both locations in the environment and events of an interaction task. | The topological map; A state diagram | The platform’s moving patterns were very similar to those of people. |

| Pyo et al. [58] | A service robot for daily life assistance for the elderly | Develop an informationally structured environment using distributed sensors. | ROS-TMS (robot operating system–town management system) includes distributed sensors, actuators, robots, and databases | Several experiments showed the suitability of the robot in detection and fetch-and-give tasks. |

| Jung et al. [59] | A marathoner service robot (MSR) that provides a service to a marathoner in training | Present a human detection algorithm and an obstacle avoidance algorithm for the MSR. | A support vector data description (SVDD) method-based feature selection | The MSR performed a human tracking task without collisions. |

| Nieuwenhuisen et al. [60] | Anthropomorphic robot for a bin picking and part delivery task | Present an integrated system for a mobile bin-picking and part delivery task. | Navigation and manipulation skills; View planning techniques | The lab experiments showed the applicability of the service robot in the task. |

| Lin et al. [61] | The home service robot, May, in solving the obstacle avoidance problem | Present a particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm, named the PSO-IAC algorithm, to solve the obstacle avoidance problem. | PSO algorithm which integrates the constriction factor and adaptive inertia weight | PSO-IAC algorithm took only a few generations to obtain the optimal solution and did not need to re-exploit and re-explore new particles. |

| Wu et al. [62] | Semantic hybrid map building for a quasi-structured home | Present the Quick Response(QR) code-based artificial label. | Artificial label Identification with QR code; SIFT matching algorithm; Spectral clustering algorithm; Semantic path planning | The spatial semantic hybrid map captured the human point-of-view of the robot environments and achieved function-driven navigation. |

| Khaliq and Saffiotti [63] | Navigation of a full-scale robotic system in a real apartment | Propose a stigmergic approach to goal-directed navigation. | A grid of read-write RFID tags embedded in the floor; Algorithms for building navigation maps directly into these tags | The proposed navigation system generated reliable navigation for a full-scale domestic service robotic. |

| Kim and Chung [64] | A guide robot, Jinny, at the National Science Museum of Korea | Propose a formal selection framework of multiple navigation behaviors for a service robot. | Generalized stochastic Petri nets (GSPNs) | The proposed framework helped the robot select an appropriate navigation behavior. |

| Lopez et al. [65] | Autonomous guided vehicle (AGV) systems | Present an online trajectory planning and optimization approach for cooperative multi-robot navigation. | An elastic-band-based method for obstacle avoidance; Predictive trajectory planner. A cloud-based navigation infrastructure | The proposed approach successfully obtained smooth transitions with two mobile service robots in all path crossing scenarios. |

| Select Paper | Use Case | Purpose | Techniques | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Halme et al. [66] | WorkPartner working interactively with humans in an outdoor environment | Present the mechatronic structure, the functional subsystems, and motion control principles of the robot. | A mobile hybrid platform; human-machine Interface (HMI) | The HMI is multimedia-based and highly interactive. presence model. |

| de Jong et al. [67] | Pepper, an interactive humanoid robot | Extend and evaluate Pepper’s capability for human-robot social interaction. | State-of-the-art vision system (OpenPose real-time pose detection library and keypoint-based object detection algorithm); Speech recognition system (augmented the existing software with cloud-based speech recognition) | For successful interaction, Pepper should not only sense and understand human input but also be able to verbalize its own experience. |

| Böhme et al. [68] | A robot as a mobile information kiosk in a home store | Develop a multi-modal scheme for human-robot interaction for a wide range of intelligent service robots. | Vision-based potential user detection method; A biologically inspired model of binaural sound localization; An integrated localization system | The experimental results demonstrated the principal functionality of the corresponding subsystems. |

| Lee et al. [69] | Service robots in home-based daily activities | Present a human–robotinteraction framework that guides a general structure of future home service robots. | Three interaction modules: multimodal, cognitive, and emotional interaction modules | The concept for software integration and the relationships among the three modules were discussed, but no experiments were conducted. |

| Kwon et al. [70] | Emotion interaction systems for service robots greeting a guest | Develop a framework of emotion interaction for service robots. | The emotion interaction system composed of the emotion recognition, generation, and expression systems. | Even though the multi-modal emotion recognition and expression technologies are still in their early stage, the proposed system is useful for service robot applications. |

| Droeschel et al. [71] | Person awareness and gesture recognition of a service robot in a laboratory environment | Propose an approach for a domestic service robot that integrates person awareness with pointing and showing gestures. | Laser-range finders; Time-of-Flight camera. | The proposed system achieved higher accuracy than previous studies for a stereo-based system. |

| Ding et al. [72] | Hand gesture Human-Computer Interactions (HCIs) for disabled people with mobility problems | Design hand gesture HCIs for disabled people with mobility problems. | Mobile service robot platform; Three-dimensional (3D) imaging sensors; Wearable Myo armband device | The results demonstrated the effectiveness of the methods. |

| Luo and Wu [73] | Hand sign recognition for human-robot interaction | Present a combining method. | Hand skeleton recognizer (HSR); Support vector machines (SVM) | The study demonstrated gesture recognition experimentally with a successful proof of concept. |

| Bien and Lee [74] | Stewardess robot with the sign language recognition and personalized facial expression recognition, and probabilistic fuzzy rule-based behavior learning | Present the soft-computing toolbox approach for effective hybridization of intelligent techniques for the design of a human-friendly system. | Fuzzy logic-based learning techniques; Soft computing toolbox | Fuzzy logic-based hybrid learning techniques worked for some recognition systems in the HRI process. |

| Pacchierotti et al. [75] | A robot that operates in hallway settings | Design social patterns of spatial interaction for a robot operating in hallway settings based on the rules of proxemics. | A module for mapping the local environment; A module for people detection and tracking; A module for navigation in narrow spaces; A module for navigation among dynamically changing targets | The robot with the best behavior was the one with higher speed, larger signaling distance, and larger lateral distances. |

| Select Paper | Use Case | Purpose | Techniques | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breuer et al. [76] | Johnny Jackanapes, an autonomous service robot for serving guests in a restaurant | Describe the architecture, algorithms, and real-world benchmarks with Johnny Jackanapes. | System architecture consisting of the modular mobile platform, control architecture based on a deliberative layer, software architecture which is a loosely integrated aggregation of dedicated autonomous components, and service robot simulator | The overall system performance was proven at various RoboCup@Home competitions. |

| Reiser et al. [77] | A compact service robot for serving drinks | Introduce Care-O-bot® 3, a highly integrated and compact service robot with manipulation, navigation, and vision capabilities. | Hardware setup including 28 DOF; Two SICK S300 laser scanners; The control software; Three independent kinematic chains (manipulator, sensor carrier, tray) | While every single component succeeded in over 70% of the cases, the system accomplished the whole process only 6 out of 15 times. |

| Puigbo et al. [78] | Human size humanoid robot, REEM, acting as a general-purpose service robot | Develop a control architecture for a service robot to generate and execute its plan for goal attainment. | Four main modules connected: an automatic speech recognition (ASR) module, the semantic extractor module for a goal generation, the reasoner module for goal compilation, action selection, and skill activations, and the action nodes module for the execution of the skills | The system ensures that the robot will find a solution, while the optimality is not guaranteed. |

| Datta et al. [79] | RoboStudio, a visual programming environment (VPE) to program the interactive behavior of personal service robots | Describe the RoboStudio VPE for robot design. | XML-based Robot Behavior Description Language (RBDL); The RoboStudio interface components; RoboStudio architecture based on the open-source NetBeans Platform | The states generated using RoboStudio represented the same application logic as the hand-coded scripts and therefore, confirmed the validity of the XML code generation. |

| Delgado et al. [80] | Telepresence robot to facilitate human communication across distances | Propose a real-time (RT) control architecture based on Xenomai, an RT embedded Linux, to control a service robot | Architecture to supportcross-domain datagram protocol (XDDP) to facilitate data exchange between RT and NRT tasks; Simple APIs that emulate the Xenomai native functions to create RT tasks | The proposed architecture is essential in designing RT control applications for a mobile robot. |

| Zieliński et al. [81] | Use of two-handed service robot controllers for solving the Rubik’s cube puzzle | Develop universal software for the implementation of service robot controllers. | Robot programming framework, MRROC++; QNX real-time operating system | Experiments with diverse tasks showed that MRROC++ is well suited to producing controllers for prototype service robots. |

| Niemueller et al. [82] | A database for systematic manual fault analysis of the domestic service robot, HERB | Propose a database system that utilizes common robot middleware to record all data produced at run-time. | A generic robot database, MongoDB, implemented in two frameworks, ROS and Fawkes for data recording facilities | The ability to query specific data sets helped to reduce investigation time. |

| Quigley et al. [83] | Open-source robot operating system (ROS) related to other robot software frameworks | Present an overview of ROS, an open-source robot operating system. | ROS with the support for peer-to-peer, tools-based, multi-lingual; thin, and free and open-source | The open architecture of ROS facilitates the creation of a wide range of tools such as visualization and monitoring, the composition of functionalities, and ROS packages. |

| Sanfeliu et al. [84] | A community of robots in distributed heterogeneous systems | Define network robot systems (NRS). | Physical embodiment; Autonomous capabilities; Network-based cooperation; Environment sensors and actuators; Human-robot interaction | NRS applications include network robot teams, human-robot networked teams, robots networked with the environment, and geminoid robots. |

| Berenson et al. [85] | Path planning tasks of a mobile manipulator and a minimally-invasive surgery robot | Propose a framework, called Lightning, for planning paths in high-dimensional spaces. | A planning-from-scratch module; A module that retrieves and repairs paths stored in a path library. | The retrieve-and repair module produced paths faster than the planning-from-scratch module in over 90% of test cases for the mobile manipulator and 58% of test cases for the minimally-invasive surgery robot. |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, I. Service Robots: A Systematic Literature Review. Electronics 2021, 10, 2658. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10212658

Lee I. Service Robots: A Systematic Literature Review. Electronics. 2021; 10(21):2658. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10212658

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, In. 2021. "Service Robots: A Systematic Literature Review" Electronics 10, no. 21: 2658. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10212658

APA StyleLee, I. (2021). Service Robots: A Systematic Literature Review. Electronics, 10(21), 2658. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10212658