An Optimized Stacking Ensemble Model for Phishing Websites Detection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Works

2.1. Recognizing Phishing Attacks in the IoT

2.2. Machine-Learning-Based Detection Methods

3. Materials and Methods

The Dataset and Experimental Design

4. Results and Discussion

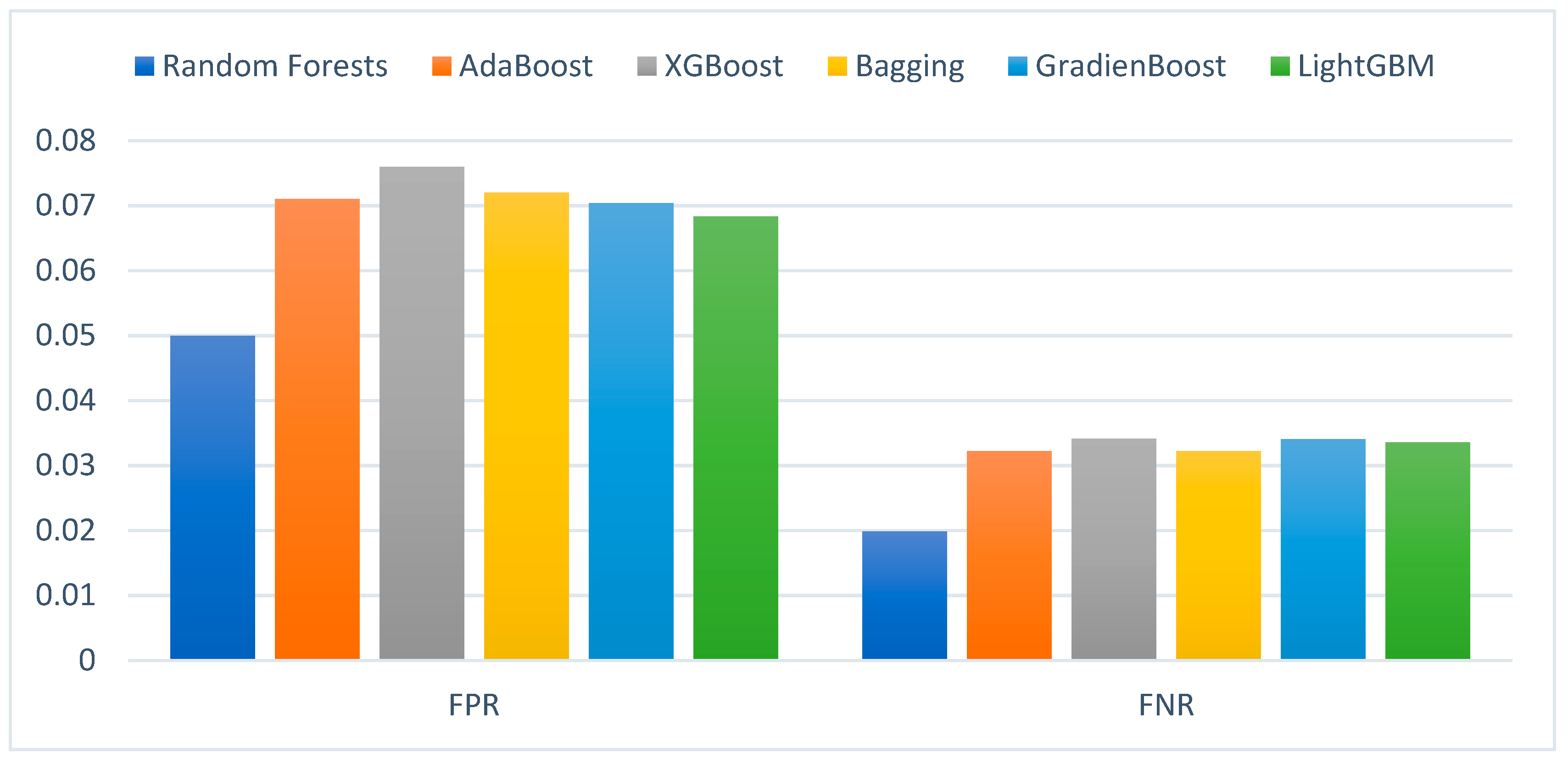

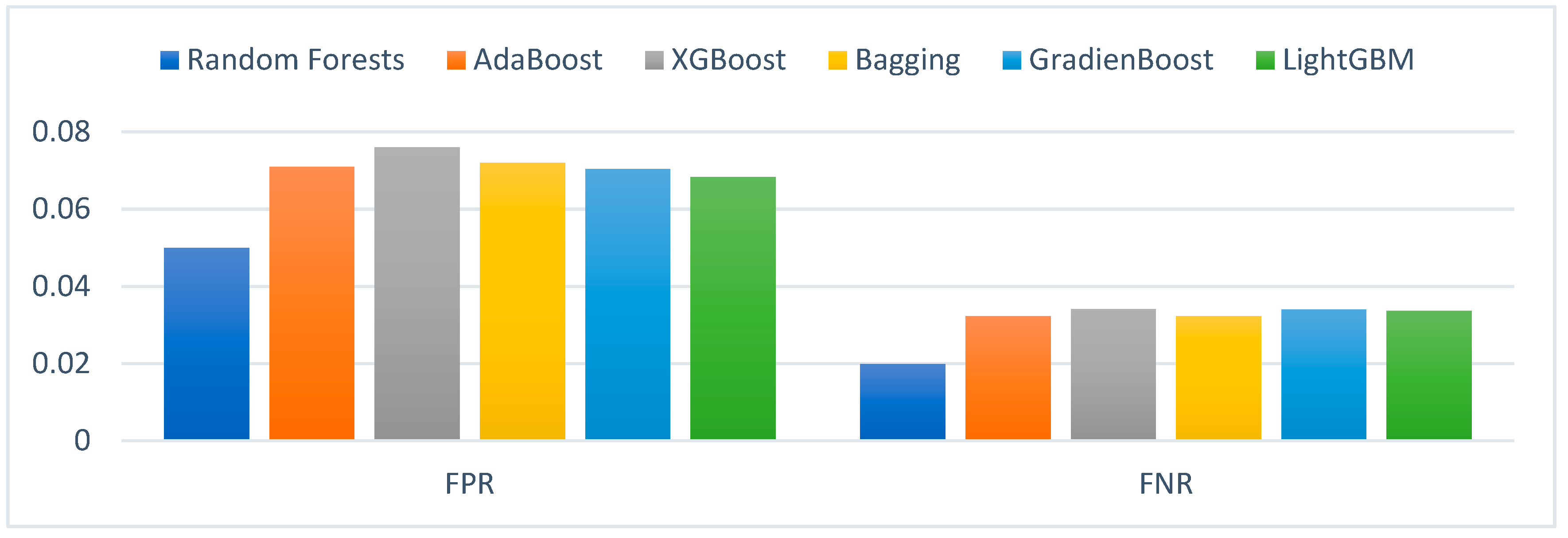

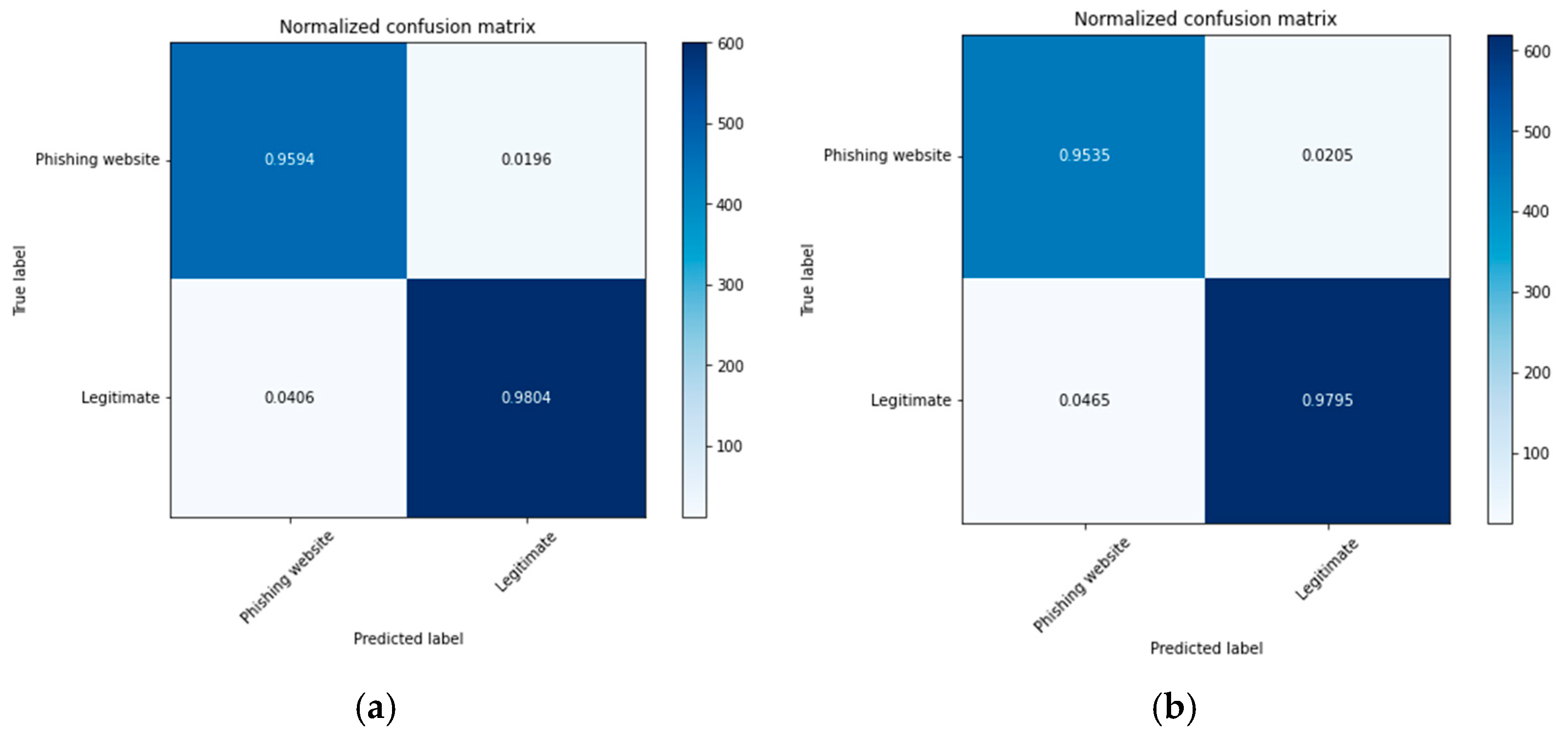

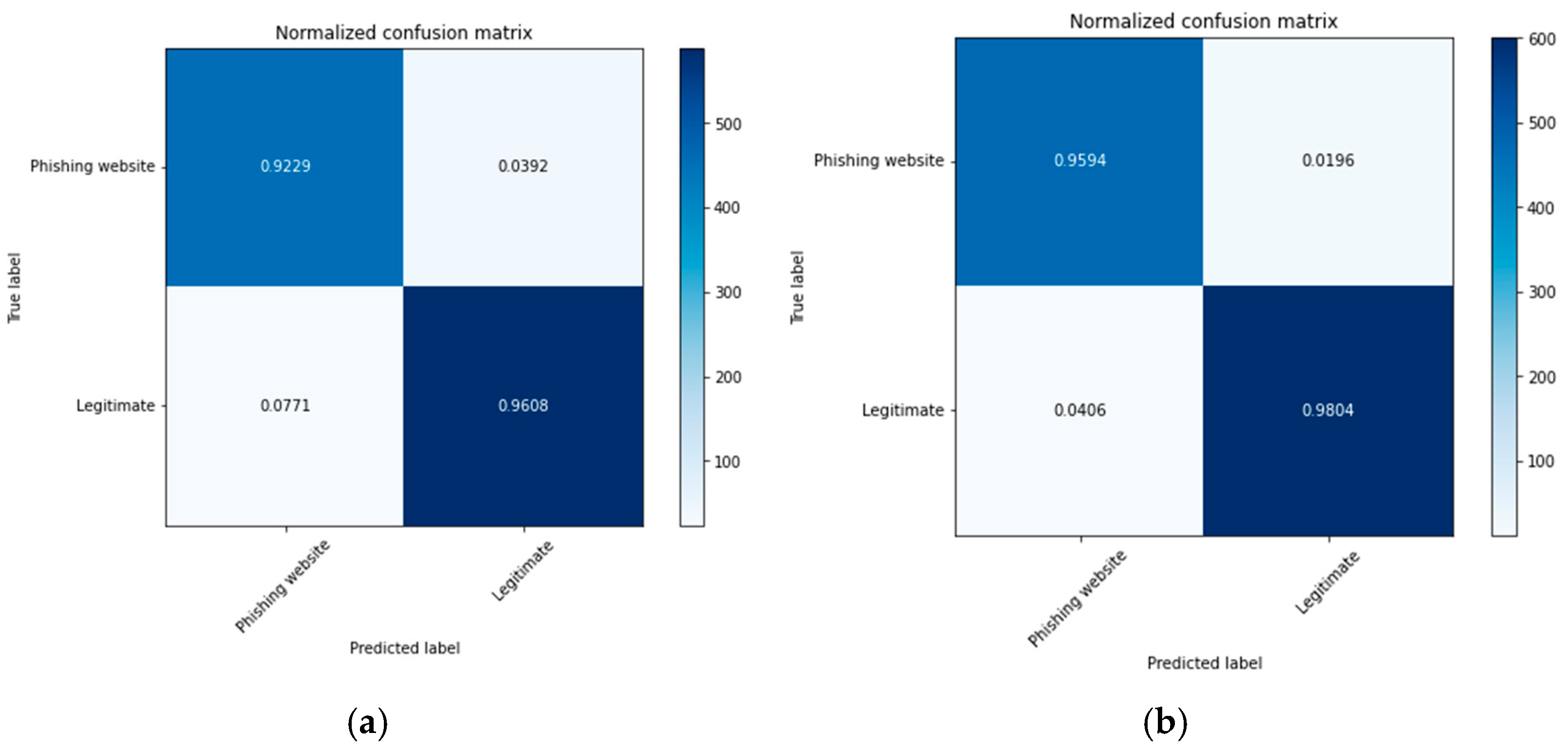

4.1. Experimental Results of the Ensemble Classifiers without Optimization

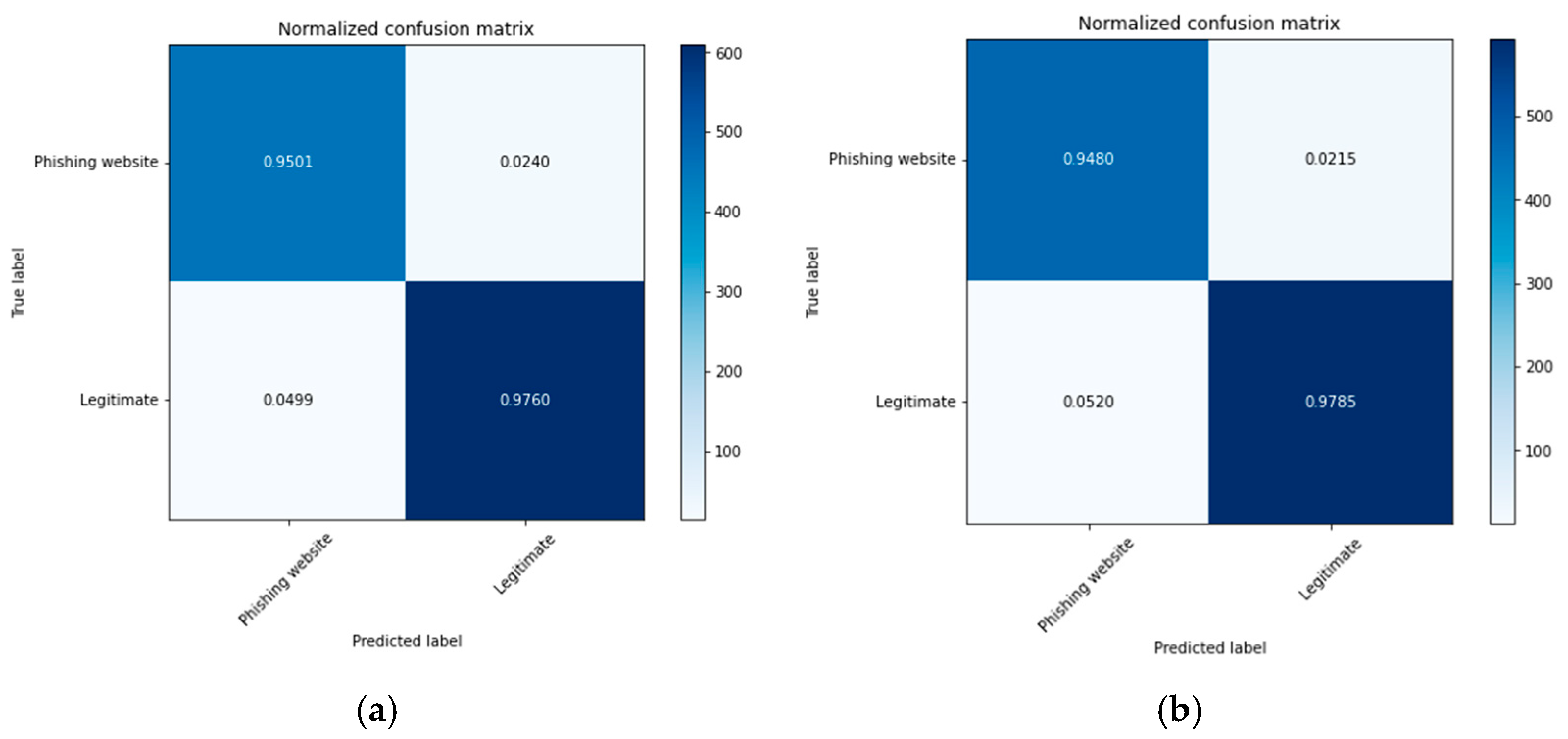

4.2. Experimental Results of the GA-Based Ensemble Classifiers

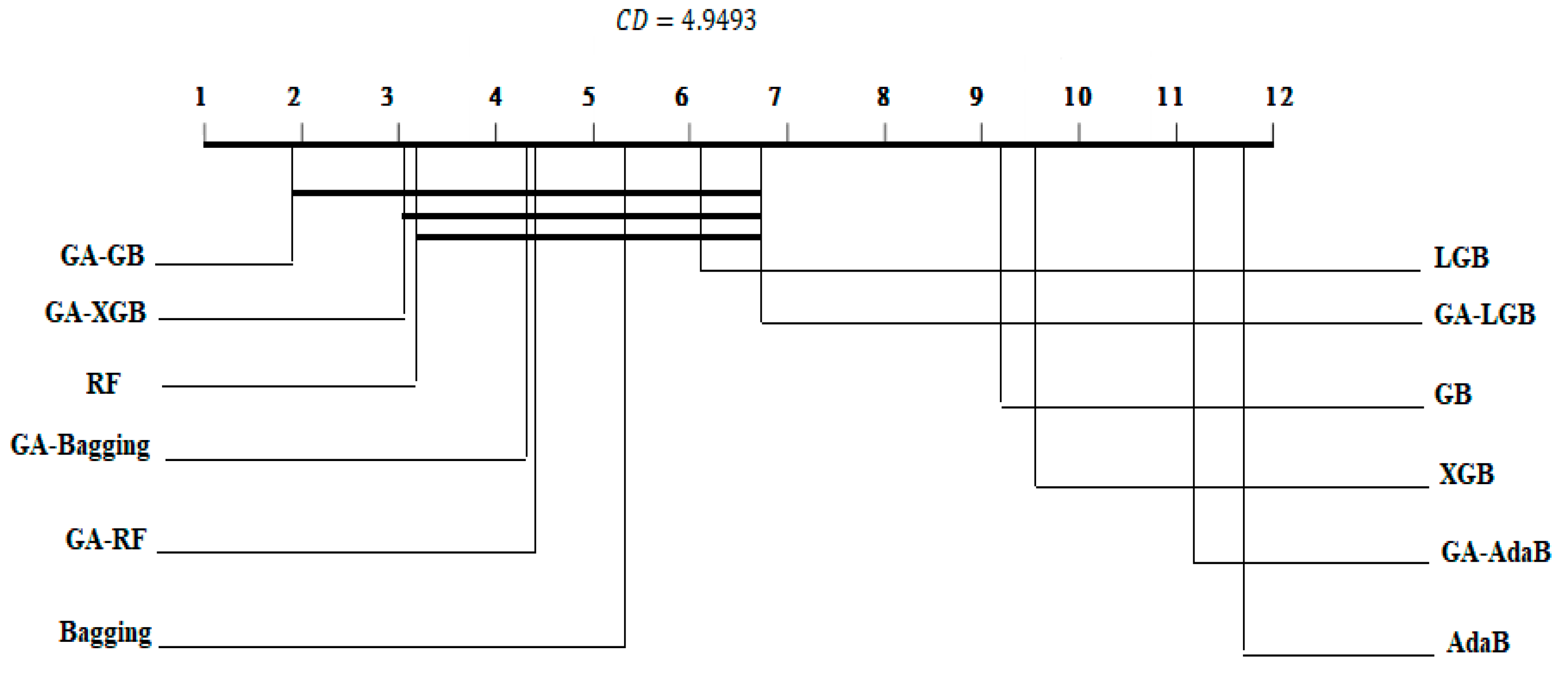

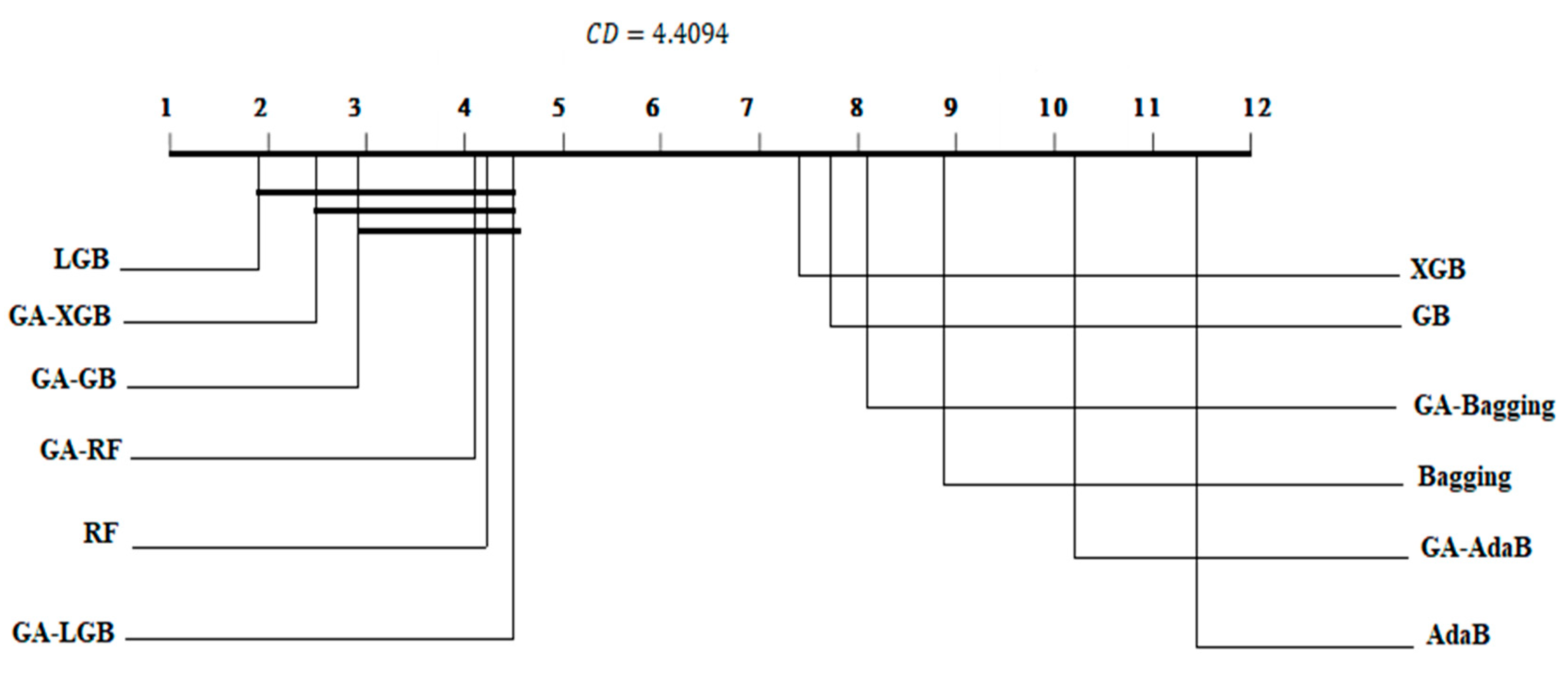

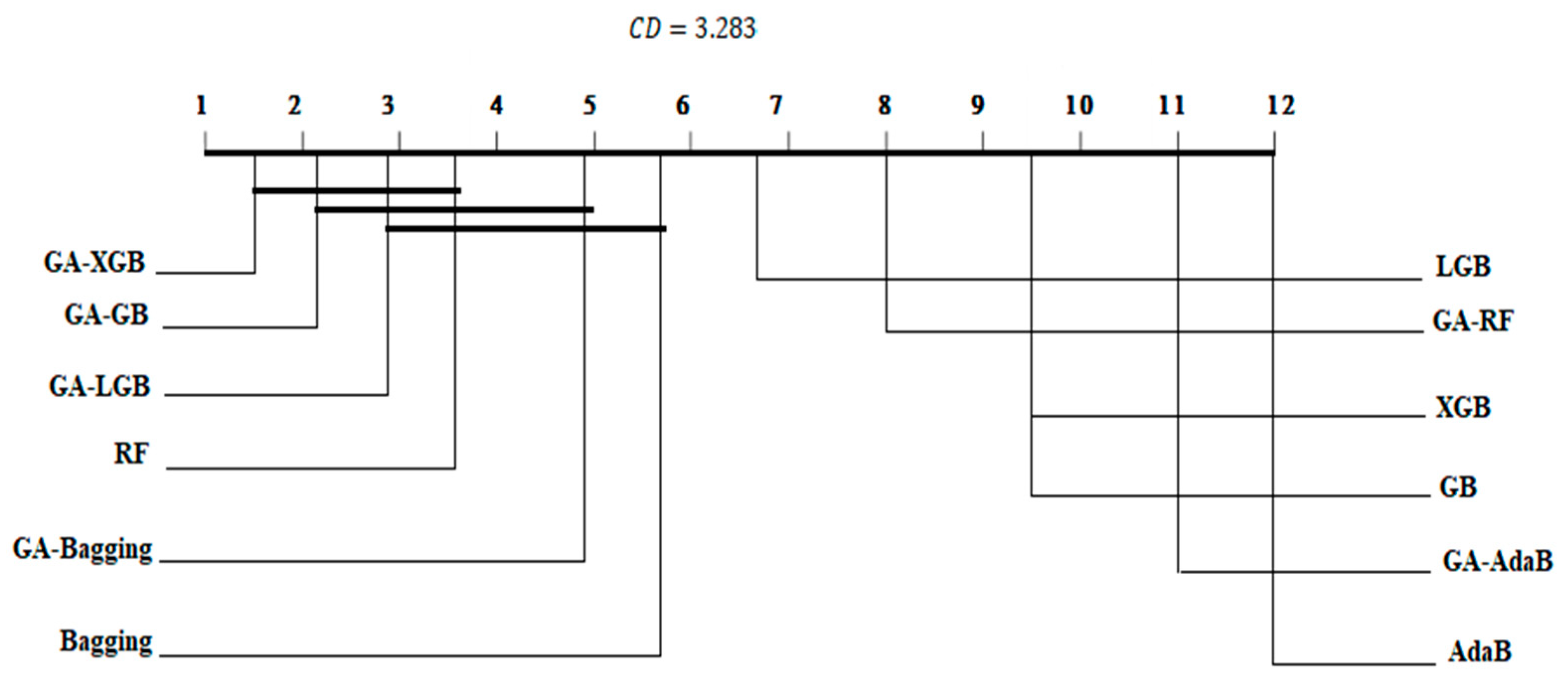

4.3. Statistical Analysis and Comparison with Previous Studies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gupta, B.B.; Arachchilage, N.A.G.; Psannis, K.E. Defending against phishing attacks: Taxonomy of methods, current issues and future directions. Telecommun. Syst. 2018, 67, 247–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gubbi, J.; Buyya, R.; Marusic, S.; Palaniswami, M.S. Internet of Things (IoT): A vision, architectural elements, and future directions. Futur. Gener. Comput. Syst. 2013, 29, 1645–1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roman, R.; Najera, P.; Lopez, J. Securing the Internet of Things. Computer 2011, 44, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D. Event Detection in Sensor Networks; School of Engineering and Applied Sciences, The George Washington University: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Wei, B.; Hamad, R.A.; Yang, L.; He, X.; Wang, H.; Gao, B.; Woo, W.L. A Deep-Learning-Driven Light-Weight Phishing Detection Sensor. Sensors 2019, 19, 4258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somesha, M.; Pais, A.R.; Rao, R.S.; Rathour, V.S. Efficient deep learning techniques for the detection of phishing websites. Sadhana 2020, 45, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Ahmed, A.A. Hybrid intelligent phishing website prediction using deep neural networks with genetic algorithm-based feature selection and weighting. IET Inf. Secur. 2019, 13, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiew, K.L.; Tan, C.L.; Wong, K.; Yong, K.S.; Tiong, W.K. A new hybrid ensemble feature selection framework for machine learning-based phishing detection system. Inf. Sci. 2019, 484, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, R.S.; Pais, A.R. Detection of phishing websites using an efficient feature-based machine learning framework. Neural Comput. Appl. 2018, 31, 3851–3873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, W.; Malebary, S. Particle Swarm Optimization-Based Feature Weighting for Improving Intelligent Phishing Website Detection. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 116766–116780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khursheeed, F.; Sami-Ud-Din, M.; Sumra, I.A.; Safder, M. A Review of Security Machanism in internet of Things (IoT). In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Advancements in Computational Sciences (ICACS), Lahore, Pakistan, 17–19 February 2020; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiknas, K.; Taketzis, D.; Demertzis, K.; Skianis, C. Cyber Threats to Industrial IoT: A Survey on Attacks and Countermeasures. IoT 2021, 2, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, G.D.L.T.; Rad, P.; Choo, K.-K.R.; Beebe, N. Detecting Internet of Things attacks using distributed deep learning. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2020, 163, 102662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, J.; Bian, J.; Tian, W.; Zhu, S.; Wei, T.; Li, A.; Liang, Z. Phishing page detection via learning classifiers from page layout feature. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2019, 2019, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virat, M.S.; Bindu, S.; Aishwarya, B.; Dhanush, B.; Kounte, M.R. Security and Privacy Challenges in Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2018 2nd International Conference on Trends in Electronics and Informatics (ICOEI), Tirunelveli, India, 11–12 May 2018; pp. 454–460. [Google Scholar]

- Deogirikar, J.; Vidhate, A. Security attacks in IoT: A survey. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on I-SMAC (IoT in Social, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud) (I-SMAC), Palladam, India, 10–11 February 2017; Volume 16, pp. 32–37. [Google Scholar]

- Alotaibi, B.; Alotaibi, M. A Stacked Deep Learning Approach for IoT Cyberattack Detection. J. Sensors 2020, 2020, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsariera, Y.A.; Adeyemo, V.E.; Balogun, A.O.; Alazzawi, A.K. AI Meta-Learners and Extra-Trees Algorithm for the Detection of Phishing Websites. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 142532–142542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.K.; Gupta, B.B. A machine learning based approach for phishing detection using hyperlinks information. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2018, 10, 2015–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, F.; Zhou, Q.; Shen, Z.; Yang, X.; Han, L.; Wang, J. The application of a novel neural network in the detection of phishing websites. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2018, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aburub, F.; Hadi, W. A New Association Classification Based Method for Detecting Phishing Websites. J. Theor. Appl. Inf. Technol. 2021, 99, 147–158. [Google Scholar]

- Gandotra, E.; Gupta, D. An Efficient Approach for Phishing Detection using Machine Learning. In Multimedia Security; Giri, K.J., Parah, S.A., Bashir, R., Muhammad, K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shabudin, S.; Sani, N.S.; Ariffin, K.A.Z.; Aliff, M. Feature Selection for Phishing Website Classification. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2020, 11, 587–595. [Google Scholar]

- Subasi, A.; Molah, E.; Almkallawi, F.; Chaudhery, T.J. Intelligent phishing website detection using random forest classifier. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Electrical and Computing Technologies and Applications (ICECTA), Ras Al Khaimah, United Arab Emirates, 21–23 November 2017; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X. Phishing Websites Detection Based on Hybrid Model of Deep Belief Network and Support Vector Machine. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2020, 602, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, N.A.; Salaudeen, B.B.; Misra, S.; Damaševičius, R.; Maskeliūnas, R. Identifying phishing attacks in communication networks using URL consistency features. Int. J. Electron. Secur. Digit. Forensics 2020, 12, 200–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azeez, N.A.; Atiku, O.; Misra, S.; Adewumi, A.; Ahuja, R.; Damasevicius, R. Detection of Malicious URLs on Twitter. In Advances in Electrical and Computer Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2020; pp. 309–318. [Google Scholar]

- Osho, O.; Oluyomi, A.; Misra, S.; Ahuja, R.; Damasevicius, R.; Maskeliunas, R. Comparative Evaluation of Techniques for Detection of Phishing URLs. In Proceedings of the Communications in Computer and Information Science; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 385–394. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, D.R.; Patil, J.B. Malicious web pages detection using feature selection techniques and machine learning. Int. J. High. Perform. Comput. Netw. 2019, 14, 473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PhishTank, Developer Information. Available online: http://phishtank.org/developer_info.php (accessed on 28 February 2021).

- Dua, D.; Graff, C. UCI Machine Learning Repository; School of Information and Computer Science, University of California: Irvine, CA, USA. Available online: https://archive.ics.uci.edu/ml/datasets/Phishing+Websites (accessed on 10 January 2021).

- Tan, C.L. Phishing Dataset for Machine Learning: Feature Evaluation. Mendeley Data 2018, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrbančič, G. Phishing Websites Dataset. Mendeley Data 2020, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Tong, G.; Yin, H.; Xiong, N. A Pedestrian Detection Method Based on Genetic Algorithm for Optimize XGBoost Training Parameters. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 118310–118321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Khan, W.; Hussain, A. Phishing Attacks and Websites Classification Using Machine Learning and Multiple Datasets (A Comparative Analysis). In Proceedings of the Transactions on Petri Nets and Other Models of Concurrency XV; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 301–313. [Google Scholar]

| Feature Category | Feature Name | Description | Python Library Used |

|---|---|---|---|

| Address-bar-based | having_IP_Address | Using the IP Address | IPaddress Urllib Re Datetime BeautifulSoup Socket |

| URL_Length | Long URL to hide the suspicious part | ||

| Shortening_Service | Using shortening service | ||

| having_At_Symbol | URL having @ symbol | ||

| double_slash_redirecting | URL uses “//” symbol | ||

| Prefix_Suffix | Add prefix or suffix separated by (-) | ||

| having_Sub_Domain | Website has subdomain or multi-subdomain | ||

| SSLfinal_State | Age of SSL certificate | ||

| Domain_registeration_length | Domain registration length | ||

| Favicon | Associated graphic image (icon) with webpage | ||

| Port | Open port | ||

| HTTPS_token | Presence of HTTP/HTTPS in domain name | ||

| HTML- and JavaScript-based | Redirect | How many times a website has been redirected | Request BeautifulSoup |

| on_mouseover | Effect of mouse over on status bar | ||

| RightClick | Disabling right click | ||

| popUpWindow | Using pop-up window to submit personal information | ||

| Iframe | Using Iframe | ||

| Abnormality based | Request_URL | % of external objects contained within a webpage | BeautifulSoup Re WHOIS |

| URL_of_Anchor | % of URL Anchor (<a> tag) | ||

| Links_in_tags | % of links in <meta>, <script> and <link> | ||

| SFH | Server from Handler | ||

| Submitting_to_email | Submit user information using mail or mailto | ||

| Abnormal_URL | Host name in URL | ||

| Domain-based features | age_of_domain | Age of the website | WHOIS Urllib BeautifulSoup |

| DNSRecord | Website in WHOIS dataset | ||

| web_traffic | Popularity of the website | ||

| Page_Rank | Page Rank | ||

| Google_Index | Google Index | ||

| Links_pointing_to_page | # of links pointing to page | ||

| Statistical_report’ | found in statistical reports | ||

| Result | Website is classified as phishing or legitimate |

| Measure | Random Forests (%) | AdaBoost (%) | XGBoost (%) | Bagging (%) | GradientBoost (%) | LightGBM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 97.02 | 93.17 | 94.45 | 96.73 | 94.61 | 96.53 |

| Precision | 96.58 | 94.70 | 94.52 | 94.99 | 94.87 | 95.15 |

| Recall | 98.08 | 96.60 | 96.39 | 96.73 | 96.59 | 96.70 |

| F-Score | 97.49 | 95.71 | 95.50 | 95.90 | 95.76 | 95.95 |

| Measure | Random Forests (%) | AdaBoost (%) | XGBoost (%) | Bagging (%) | GradientBoost (%) | LightGBM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 98.37 | 96.88 | 97.70 | 97.51 | 97.67 | 98.65 |

| Precision | 98.54 | 96.74 | 97.57 | 97.55 | 97.58 | 98.56 |

| Recall | 98.26 | 97.04 | 97.85 | 97.44 | 97.76 | 98.74 |

| F-Score | 98.39 | 96.88 | 97.71 | 97.46 | 97.67 | 98.65 |

| Measure | Random Forests (%) | AdaBoost (%) | XGBoost (%) | Bagging (%) | GradientBoost (%) | LightGBM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 97.15 | 93.58 | 95.33 | 96.78 | 95.37 | 96.67 |

| Precision | 95.78 | 90.89 | 92.75 | 95.80 | 93.06 | 95.08 |

| Recall | 96.13 | 90.52 | 93.82 | 94.93 | 93.58 | 95.28 |

| F-Score | 95.90 | 90.70 | 93.28 | 95.33 | 93.32 | 95.18 |

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Generations | 10 |

| Population size | 24 |

| Mutation rate | 0.02 |

| Crossover rate | 0.5 |

| Early stop | 12 |

| Classifier Name | Adjusted Parameters | Best GA-Based Configuration |

|---|---|---|

| Random Forests | Criterion: [‘entropy’, ‘gini’] max_depth: [10–1200] + [None] max_features: [‘auto’, ‘sqrt’,’log2’, None] min_samples_leaf: [4–12] min_samples_split: [5–10] n_estimators’: [150–1200] | Criterion: entropy max_depth: 142 min_samples_leaf: 4 min_samples_split: 5 n_estimators: 1200 |

| AdaBoost | n_estimators: [100–1200] learning_rate: [1 × 10−3, 1 × 10−2, 1 × 10−1, 0.5, 1.0] | learning_rate: 0.1 n_estimators: 711 |

| XGBoost | n_estimators: [100–1200] max_depth: [1–11], learning_rate: [1 × 10−3, 1 × 10−2, 1 × 10−1, 0.5, 1.] subsample: [0.05–1.01] min_child_weight: [1–21] | learning_rate: 0.1 max_depth: 5 min_child_weight: 3.0 n_estimators: 588 subsample: 0.7 |

| Bagging | n_estimators: [100–1200] max_samples: [0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 1.0, 1.1] bootstrap: [True, False] | n_estimators: 1077 max_samples: 0.5 bootstrap: True |

| GradientBoost | n_estimators: [100–1200] learning_rate: [1 × 10−3, 1 × 10−2, 1 × 10−1, 0.5, 1.0] subsample: [0.05–1.01] max_depth: [10–1200] + None min_samples_split: [5–10] min_samples_leaf: [4–12] max_features: [‘auto’, ‘sqrt’,’log2’, None] | n_estimators: 344 learning_rate: 1.0 subsample: 1.0 max_depth: 1067 min_samples_split: 5 min_samples_leaf: 12 max_features: ‘auto’ |

| LightGBM | boosting_type: [‘gbdt’, ‘dart’, ‘goss’, ‘rf’]num_leaves: [5–42] max_depth: [10–1200] + None learning_rate: [1 × 10−3, 1 × 10−2, 1 × 10−1, 0.5, 1.] n_estimators: [100–1200] min_child_samples: [100,500] min_child_weight: [1 × 10−5, 1 × 10−3, 1 × 10−2, 1 × 10−1, 1, 10, 100, 1000, 10000] subsample: sp_uniform(loc = 0.2, scale = 0.8) colsample_bytree’: sp_uniform(loc = 0.4, scale = 0.6) reg_alpha: [0, 10−1, 1, 2, 5, 7, 10, 50, 100], reg_lambda: [0, 10−1, 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100], min_split_gain: 0.0, subsample_for_bin: 200,000 | boosting_type: ‘gbdt’ num_leaves: 13 max_depth: 15 learning_rate: 0.5 n_estimators: 500 min_child_samples: 399 min_child_weight: 0.1 subsample: 0.855 colsample_bytree: 0.9234 reg_alpha: 2 reg_lambda: 5 min_split_gain: 0.0, subsample_for_bin: 200,000 |

| Fold | GA–RF (%) | GA–AdaBoost (%) | GA–XGBoost (%) | GA–Bagging (%) | GA–GradientBoost (%) | GA–LightGBM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 97.11 | 94.85 | 96.75 | 96.56 | 97.11 | 96.84 |

| 2 | 96.84 | 93.13 | 97.02 | 96.75 | 96.93 | 96.47 |

| 3 | 97.20 | 93.04 | 96.93 | 96.56 | 96.93 | 95.66 |

| 4 | 96.02 | 93.76 | 97.47 | 97.65 | 97.83 | 96.20 |

| 5 | 96.29 | 92.95 | 97.02 | 97.02 | 97.02 | 96.20 |

| 6 | 96.47 | 93.57 | 96.92 | 96.74 | 97.01 | 96.20 |

| 7 | 96.74 | 92.85 | 97.29 | 97.01 | 97.29 | 96.83 |

| 8 | 97.83 | 95.66 | 97.56 | 97.47 | 97.83 | 97.47 |

| 9 | 97.01 | 92.85 | 97.29 | 97.01 | 97.19 | 96.56 |

| 10 | 95.93 | 93.67 | 95.93 | 96.20 | 96.11 | 95.75 |

| Average | 96.74 | 93.63 | 97.01 | 96.90 | 97.13 | 96.42 |

| Classifier | Class Name | Precision (%) | Recall (%) | F-Score (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA–Random Forests | Phishing website | 96.40 | 94.10 | 95.10 |

| Legitimate | 95.20 | 97.30 | 96.40 | |

| Weighted Average | 95.90 | 95.70 | 95.90 | |

| GA–XGBoost | Phishing website | 97.50 | 95.80 | 96.50 |

| Legitimate | 96.70 | 98.00 | 97.20 | |

| Weighted Average | 97.00 | 97.00 | 97.00 | |

| GA–GradientBoost | Phishing website | 97.00 | 95.70 | 96.40 |

| Legitimate | 96.80 | 97.50 | 97.10 | |

| Weighted Average | 96.90 | 96.80 | 96.80 | |

| GA–LightGBM | Phishing website | 95.10 | 94.20 | 94.70 |

| Legitimate | 95.50 | 96.30 | 95.80 | |

| Weighted Average | 95.30 | 95.30 | 95.30 |

| Measure | GA–Random Forests (%) | GA–AdaBoost (%) | GA–XGBoost (%) | GA–Bagging (%) | GA–GradientBoost (%) | GA–LightGBM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 98.39 | 97.21 | 98.57 | 97.51 | 98.50 | 98.32 |

| Precision | 98.46 | 97.15 | 98.50 | 97.24 | 98.31 | 98.10 |

| Recall | 98.13 | 97.28 | 98.64 | 97.89 | 98.54 | 98.56 |

| F-Score | 98.43 | 97.21 | 98.57 | 97.52 | 98.37 | 98.33 |

| Measure | GA–Random Forests (%) | GA–AdaBoost (%) | GA–XGBoost (%) | GA–Bagging (%) | GA–GradientBoost (%) | GA–LightGBM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | 96.44 | 94.06 | 97.35 | 96.96 | 97.27 | 97.21 |

| Precision | 94.63 | 90.91 | 96.20 | 95.3 | 95.68 | 96.13 |

| Recall | 95.08 | 92.02 | 96.14 | 95.96 | 96.30 | 95.81 |

| F-Score | 94.86 | 91.46 | 96.17 | 95.64 | 95.78 | 95.96 |

| ML Classifier | Dataset 1 | Dataset 2 | Dataset 3 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Rank | Mean | SD | Mean Rank | Mean | SD | Mean Rank | Mean | SD | |

| RF | 3.2 | 0.970 | 0.00427 | 4.2 | 0.9837 | 0.00332 | 3.6 | 0.971 | 0.00229 |

| GA–RF | 4.4 | 0.967 | 0.00554 | 4.1 | 0.9839 | 0.00327 | 8 | 0.964 | 0.00269 |

| AdaB | 11.7 | 0.932 | 0.00549 | 11.5 | 0.9688 | 0.00477 | 12 | 0.936 | 0.00335 |

| GA–AdaB | 11.2 | 0.936 | 0.00889 | 10.2 | 0.9721 | 0.00448 | 11 | 0.941 | 0.00299 |

| XGB | 9.6 | 0.945 | 0.00491 | 7.4 | 0.9770 | 0.00508 | 9.5 | 0.9532 | 0.00339 |

| GA–XGB | 3.1 | 0.970 | 0.00447 | 2.5 | 0.9857 | 0.00310 | 1.5 | 0.974 | 0.00201 |

| Bagging | 5.3 | 0.967 | 0.00492 | 8.9 | 0.9751 | 0.00567 | 5.8 | 0.968 | 0.00214 |

| GA–Bagging | 4.3 | 0.969 | 0.00412 | 8.1 | 0.9751 | 0.00579 | 4.9 | 0.969 | 0.00243 |

| GB | 9.2 | 0.946 | 0.00578 | 7.8 | 0.9767 | 0.00492 | 9.5 | 0.954 | 0.00330 |

| GA–GB | 1.8 | 0.971 | 0.00464 | 2.9 | 0.9850 | 0.00293 | 2.2 | 0.973 | 0.00222 |

| LGB | 6.1 | 0.965 | 0.00561 | 1.9 | 0.9865 | 0.00307 | 6.7 | 0.967 | 0.00227 |

| GA–LGB | 6.7 | 0.964 | 0.00514 | 4.5 | 0.9832 | 0.00421 | 2.9 | 0.972 | 0.00235 |

| Dataset | RF Level (%) | GB (%) | SVM (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dataset 1 | 97.00 | 96.82 | 97.16 |

| Dataset 2 | 98.57 | 98.47 | 98.58 |

| Dataset 3 | 97.22 | 97.32 | 97.39 |

| Classifier Name | Without Optimization | With GA Optimization | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forests | Avg. | 97.02% | 96.74% |

| Variance | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| AdaBoost | Avg. | 93.17% | 93.63% |

| Variance | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| XGBoost | Avg. | 94.45% | 97.01% |

| Variance | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| Bagging | Avg. | 96.73% | 96.90% |

| Variance | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| GradientBoost | Avg. | 94.61 | 97.13% |

| Variance | 0.000 | 0.000 | |

| LightGBM | Avg. | 96.53% | 96.42% |

| Variance | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Classifier Name | t-Test Result | Conclusion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Forests | t-stat. | 1.466706885 | No significant |

| p-value | 0.088 | improvement | |

| AdaBoost | t-stat. | −2.100040666 | Significant |

| p-value | 0.032556993 | improvement | |

| XGBoost | t-stat. | −13.49130461 | Significant |

| p-value | 0.000 | improvement | |

| Bagging | t-stat. | −2.976672182 | Significant |

| p-value | 0.008 | improvement | |

| GradientBoost | t-stat. | −11.26647694 | Significant |

| p-value | 0.000 | improvement | |

| LightGBM | t-stat. | 0.971025 | No significant |

| p-value | 0.178454 | improvement |

| Paper | Classifier | Dataset | Accuracy% | Precision % | Recall % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali and Ahmed [7] | GA–ANN | Dataset 1 | 88.77 | 85.81% | 93.34% |

| Ali and Malebary [10] | POS–RF | Dataset 1 | 96.83 | 98.76% | 95.37% |

| This study | The stacking ensemble method | Dataset 1 | 97.16 | 96.86% | 96.83% |

| Khan, Khan, and Hussain [35] | ANN after PCA | Dataset 2 | 97.13 | 96.48% | 98.03% |

| This study | The stacking ensemble method | Dataset 2 | 98.58 | 98.50% | 98.74% |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Sarem, M.; Saeed, F.; Al-Mekhlafi, Z.G.; Mohammed, B.A.; Al-Hadhrami, T.; Alshammari, M.T.; Alreshidi, A.; Alshammari, T.S. An Optimized Stacking Ensemble Model for Phishing Websites Detection. Electronics 2021, 10, 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10111285

Al-Sarem M, Saeed F, Al-Mekhlafi ZG, Mohammed BA, Al-Hadhrami T, Alshammari MT, Alreshidi A, Alshammari TS. An Optimized Stacking Ensemble Model for Phishing Websites Detection. Electronics. 2021; 10(11):1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10111285

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Sarem, Mohammed, Faisal Saeed, Zeyad Ghaleb Al-Mekhlafi, Badiea Abdulkarem Mohammed, Tawfik Al-Hadhrami, Mohammad T. Alshammari, Abdulrahman Alreshidi, and Talal Sarheed Alshammari. 2021. "An Optimized Stacking Ensemble Model for Phishing Websites Detection" Electronics 10, no. 11: 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10111285

APA StyleAl-Sarem, M., Saeed, F., Al-Mekhlafi, Z. G., Mohammed, B. A., Al-Hadhrami, T., Alshammari, M. T., Alreshidi, A., & Alshammari, T. S. (2021). An Optimized Stacking Ensemble Model for Phishing Websites Detection. Electronics, 10(11), 1285. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics10111285