Abstract

Software Project Estimation is a challenging and important activity in developing software projects. Software Project Estimation includes Software Time Estimation, Software Resource Estimation, Software Cost Estimation, and Software Effort Estimation. Software Effort Estimation focuses on predicting the number of hours of work (effort in terms of person-hours or person-months) required to develop or maintain a software application. It is difficult to forecast effort during the initial stages of software development. Various machine learning and deep learning models have been developed to predict the effort estimation. In this paper, single model approaches and ensemble approaches were considered for estimation. Ensemble techniques are the combination of several single models. Ensemble techniques considered for estimation were averaging, weighted averaging, bagging, boosting, and stacking. Various stacking models considered and evaluated were stacking using a generalized linear model, stacking using decision tree, stacking using a support vector machine, and stacking using random forest. Datasets considered for estimation were Albrecht, China, Desharnais, Kemerer, Kitchenham, Maxwell, and Cocomo81. Evaluation measures used were mean absolute error, root mean squared error, and R-squared. The results proved that the proposed stacking using random forest provides the best results compared with single model approaches using the machine or deep learning algorithms and other ensemble techniques.

1. Introduction

Software engineering follows a systematic and cyclic approach in developing and maintaining the software [1]. Software engineering solves problems related to the software life-cycle. The life cycle of software consists of the following phases:

- ⮚

- Inception phase

- ⮚

- Requirement phase

- ⮚

- Design phase

- ⮚

- Construction phase

- ⮚

- Testing phase

- ⮚

- Deployment phase

- ⮚

- Maintenance phase

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of SDLC phases. During the inception phase, the following are the works carried out by the project team: project goal identification, carrying out various project estimations [2], and identification of the scope of the project. During the requirement or planning phase, user needs are analyzed, and functional and technical requirements are identified. During the design phase, the establishment of architecture is carried out by considering the requirements as input.

Figure 1.

Software Development Life Cycle (SDLC) phases.

In the construction phase, implementation of the project was carried out. During the starting stage of the Construction Phase, a prototype model was developed. Later, the prototype was implemented as a working model. In the testing phase, identification of bugs, errors, and defects was carried out and, finally, the software was assessed for quality. After successful testing of the software, it moved onto the deployment phase wherein the software was released into the environment for the usage of end-users. During the maintenance phase, the feedback from the end-users was received and software enhancement was carried out by the developers.

Estimation, which is the process of finding the approximation or estimate, was performed during the initial stage with several uncertain and unstable data. Estimations were used as input for planning the project, for iteration planning, investment analysis, budget analysis, and etc. [2]. Estimation identifies the size, as well as the amount of time, effort of human skill, money, [3] and resources [4] required to build a system or product. Though several models have been developed for the past two decades, effort estimation remains a challenging tasks, as there are more uncertain and unstable data during the initial stages of software development. Software effort estimation [5] is performed in terms of person-hours or person-months.

Software effort estimations are carried out using the following techniques [6]: expert judgment, analogy-based estimation, function point analysis, machine-learning techniques comprising of regression techniques, classification approaches and clustering methods, neural network and deep learning models, fuzzy-based approaches, and ensemble methods.

Initially, software effort estimation is performed based on expert judgment [7] rather than using a model approach. It is a simple way to implement estimation, and also produced realistic estimations. Delphi technique and work breakdown structure are the most prevalent expert judgment techniques used for estimation. In the Delphi technique, a meeting is conducted among the project experts and, from the arguments during the meeting, the final decision about the estimation is made. In the work breakdown structure, the entire project is broken down into sub-projects or sub-tasks. The process is continued until the baseline activities are reached.

Analogy-based estimation to predict effort was performed based on similar past projects. It also produced accurate results as it was based on past data. Function point analysis approaches were used for effort estimation, which consider the number of functions required for developing software. Various machine learning techniques like regression, classification, and clustering approaches created a large impact in predicting software effort. Various regression techniques used for effort estimation were linear regression (single and multiple linear regressions), logistic regression, elastic net regression, ridge regression, LASSO regression and stepwise regression [8].

Linear regression is a best-fit straight line that is produced as the relationship between dependent and independent variables. The difference between the estimated value and observed value is called an error. Generally, the error must be minimized.

The estimated value is provided as

In Equation (1), b0 is the Y-intercept, X is the independent variable and b1 is the slope of the line, which is provided by Equation (2),

Multiple linear regression is the extension of linear regression. It uses ‘p’ number of independent or predictor variables.

The estimated value denoted as Y′ is provided as follows:

In Equation (3), b0, b1…bp denote the coefficients, X1, X2…Xp denote predictor variables and denotes the error.

Logistic regression produces solutions only to linear problems. The sigmoid function, which is also said to be a logistic function, is provided as follows:

In Equation (4), , b0, b1,…,bp denote the coefficients, X1, X2,…Xp denote predictor variables and denotes the error.

In ridge regression, L2 regularization techniques are used to minimize the error between actual and predicted value. A huge number of input variables can be used, but produce high bias. LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regression uses the L1 regularization technique. LASSO avoids overfitting problems. Elastic net type is the combination of the LASSO and ridge regression methods [9].

In forward selection regression, the operation starts with the most important predictor variable; there will be a step-by-step increase in the predictor variables. In backward elimination regression, initially, all the predictor variables are included and, at every step, predictors of least significance are removed.

Various classification approaches used for estimation were the decision tree method, random forest approach, SVM classifier, KNN algorithm, and Naïve Bayes approach. The decision tree is a simple method, and is subjected to overfitting for a smaller training dataset. Random forest is the extension of the decision tree, and is an optimal and accurate algorithm compared with the decision tree approach; it is robust against overfitting. SVM [10] is best for linear, non-linear, structured, semi-structured, and unstructured data. KNN is a statistical approach.

KNN is sensitive to noise. The Naïve Bayes approach is based on Bayes theorem and produces a good result if the input variables are independent from one another. In the clustering-based approach, clusters are points with similar data. Hierarchical clustering, K-means clustering, and subtractive clustering were the approaches used for effort estimation.

Neural network [11] and deep learning models used for Effort Estimation were a multi-layer feed forward neural network, a radial basis neural network, a cascaded neural network [12], and Deepnet. The neural network model used a layered approach and a back propagation algorithm. It is suitable for linear and non-linear data, but an overfitting problem occurs. Fuzzy-based approaches are sensitive to outlier data. Mostly fuzzy logic models [13] are combined with other machine learning models for software effort estimation.

Ensemble Techniques are robust predictive models [14]. It provides better accurate results when compared to an existing individual machine or deep learning models. In the ensemble technique, multiple models (called as base learners) are combined to provide better results. Ensemble techniques considered for estimation [15,16] are Averaging, Weighted Averaging, Bagging, Boosting and Stacking.

- Averaging: It is performed by taking the average of prediction from a single model.

- Weighted Average: It is calculated by applying different weights to different single models, based on their prediction and finally taking the average weighted predictions.

- Bagging: It is otherwise called Bootstrap aggregation, a kind of sampling technique. Multiple samples are considered from the original dataset and similar to random forest techniques.

- Boosting: It uses a sequential method to reduce the bias. Various boosting algorithms used are XGBoost (eXtreme Gradient Boosting), GBM (Gradient Boosting Machine), AdaBoost (Adaptive Boosting).

- Stacking: Stacking does prediction from multiple models and builds a novel model.

2. Related Work

Software effort estimations are mostly carried out using the following techniques: expert judgment, analogy-based estimation, function point analysis, various machine learning techniques, which include regression techniques, classification approaches and clustering methods, neural network and deep learning models [17], fuzzy-based approaches, and ensemble methods. Table 1 describes the survey of software effort estimation using various algorithms, datasets used for estimation, evaluation measures, and findings from each paper.

Table 1.

Software Effort Estimation Analysis.

3. Mathematical Modeling

3.1. Software Effort Estimation Evaluation Metrics

3.1.1. Mean Absolute Error (MAE)

It is the average sum of absolute errors.

Absolute error = |Prediction error|

MAE = average of all absolute errors.

In Equation (6), ‘n’ is the total number of data points, is the original value, and is the predicted value.

3.1.2. Root Mean Square Error (RMSE)

The root mean square error is the measure of the standard deviation of the predicted deviation.

In Equation (7), ‘n’ is the total number of data points, is the original value, and is the predicted value.

3.1.3. R-Squared

R-squared is a statistical measure that finds the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is predicted from the independent variable. The R-squared is found by dividing the residual sum of squares (RSS) by the total sum of squares (TSS); then, it is subtracted from 1, as provided by Equation (8). RSS is the average squared error between original values y and . TSS is the squared Error between original value ‘y’ and the average of all ‘y’. The R-squared value ranges between 0 and 1. The model is preferable if the R-squared value is nearer or equal to 1. Here, a negative R-value indicates there is no correlation between the data and the model. It is also known as the co-efficient of determination.

where RSS is the residual sum of squares and TSS is the total sum of squares.

3.2. Proposed Stacking Using Random Forest for Estimation

Ensemble techniques were used to create multiple models termed base-level classifiers; they were combined to produce better predictions as compared with single-level models. There are several techniques used under ensembling, namely averaging, weighted averaging, bagging, boosting, and stacking. Proposed stacking using random forest was compared with other stacking techniques such as generalized linear model (S-GLM), stacking using decision tree (S-DT), stacking using support vector machine (S-SVM), and stacking using the random forest (S-RT) in Section 5.1. Various ensemble techniques and single-level models were compared with the proposed stacking using the random forest model in the prediction of software effort in Section 5.2. Algorithm 1 provided below explains the pseudocode of proposed stacking using random forest.

| Algorithm 1. Pseudocode of proposed stacking using random forest. |

| 1. Input: Training data, Dtrain = where = Input attributes, = Output attribute, i = 1 to n, n = Number of base classifiers. |

| 2. Output: Ensemble classifier, E |

| 3. Step 1: Learn about base-level classifiers |

| (Apply first-level classifier) |

| Base-level classifiers considered were svmRadial, decision tree (rpart), RandomForest(rf), and glmnet |

| 4. for t = 1 to T do |

| 5. learn based on Dtrain |

| 6. end for |

| 7. Step 2: Build a new dataset for predictions based on the output of the base classifier with the new dataset |

| 8. for i = 1 to n do |

| 9. |

| where |

| 10. end for |

| 11. Step 3: Learn a meta classifier. Apply second-level classifier for the new dataset |

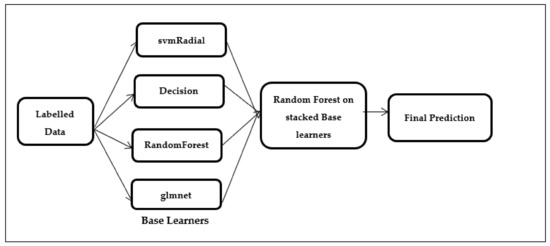

| Random Forest(rf) applied over the stacked base classifiers svm Radial, rpart, rf and glmnet (Figure 2) |

| 12. Learn E based on |

| 13. Return E (ensemble classifier) |

| 14. Predicted software effort estimation evaluation metrics using the ensemble approach are as follows: |

| 15. Mean absolute error (MAE) = |

| where ‘n’ is the total number of data points, is the original value and is the predicted value. |

| 16. Root mean squared error (RMSE) = |

| where ‘n’ is the total number of data points, is the original value, and is the predicted value. |

| 17. R-squared=, where RSS is the residual sum of squares and TSS is the total sum of squares. |

Figure 2.

Stacked random forest (SRF).

In Step 1, load the required packages and dataset. Set the seed function to ensure that we acquire the same result when the same seed is used to run the same process. As the numerical attributes have different scaling range and units, the statistical technique is used to normalize the data. The summary() command is used to find the different scaling ranges of the attributes. To normalize the data, a preprocessing method is used with the range as the factor. After normalization, the range of values are within 0 to 1. Method trainControl() is used, which specifies the cross-validation method used and, by setting class probability as True, it generates probability values as a replacement of directly forecasting the class.

The first-level classifiers considered were svmRadial, decision tree (rpart), RandomForest (rf), and glmnet as they had correlation values less than 0.85. Sub-models having less correlation suggested that the model is better and allows for the production of new classifiers. The resamples() method was used to evaluate multiple machine learning models. The dotplot(), which is a graphical representation of the results, was also obtained. In Step 2, a new dataset was obtained based on the evaluation of the first-level classifiers, namely svmRadial, decision tree (rpart), RandomForest (rf), and glmnet.

In Step 3, second-level classifiers were applied. Figure 2 shows that four different stackings of second level classifiers were done, namely the stacking of the generalized linear model over the baseline classifiers, the stacking of decision tree over baseline classifiers, the stacking of support vector machine over the baseline classifiers, and the stacking of random forest over the baseline classifiers.

4. Data Preparation

Software effort estimation was predicted using seven benchmarked datasets. Datasets were checked for missing values, and feature selection was performed based on highly correlated values in each dataset. Single base learner algorithms were compared with ensemble techniques. Proposed stacked ensemble using random forest was relatively effective compared with all other methods. Evaluation measures employed were mean absolute error, root mean square error, and R-squared.

Software Effort Estimation Datasets

Attributes and records of the datasets are elaborated in Table 2. Datasets considered for software effort estimation were Albrecht, China, Desharnais, Kemerer, Kitchenham, Maxwell, and Cocomo81. The Albrecht dataset consisted of 8 attributes and 24 records, the China dataset consisted of 16 attributes and 499 records, the Desharnais dataset consisted of 12 attributes and 81 records, the Kemerer dataset consisted of 7 attributes and 15 records, the Maxwell dataset consisted of 26 attributes and 62 records, the Kitchenham dataset consisted of 9 attributes and 145 records, and the Cocomo81 dataset consisted of 17 attributes and 63 records. The output attributes of the datasets Albrecht, Kemerer, and Cocomo81 were in the units of person-months. The datasets China, Desharnais, Maxwell, and Kitchenham were in the unit of person-hours.

Table 2.

Dimensions of the dataset.

Table 3 provides the original attributes, description and attributes considered after feature selection for the datasets: Albrecht, China, Desharnais, Kemerer, Maxwell, Kitchenham and Cocomo81. Attributes having a high correlation values are considered after feature selection.

Table 3.

Datasets – Original attributes and attributes considered after Feature selection.

5. Results and Discussion

For effort prediction, the datasets considered were Albrecht, China, Desharnais, Kemerer, Maxwell, Kitchenham, and Cocomo81. The evaluation measures considered were mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and R-squared value. It was found that the lesser the values of MAE and RMSE, the better the model; additionally, if the R-squared value was closer to 1, it was the better model. Various ensemble techniques available were averaging, weighted averaging, bagging, boosting, and stacking. Single models considered for comparison were random forest, SVM, decision tree, neural net, ridge, LASSO, elastic net and deep net algorithms.

5.1. Stacking Models

Herein, stacking built a novel model from multiple classifiers. The various stacking models considered for evaluation were stacking using generalized linear models (S-GLM), stacking using decision tree (S-DT), stacking using support vector machine (S-SVM), and stacking using random forest (S-RT).

For the stacking model approaches, the first-level classifiers considered were svmRadial, decision tree (rpart), RandomForest(rf), and glmnet. A new dataset was obtained based on the evaluation of the first-level classifiers. Four different stacking models were used as the second-level classifiers individually over the baseline (first-level) classifiers. They were stacking of generalized linear model, stacking of decision tree, stacking of support vector machine, and stacking of random forest; they were are individually applied as the second level-classifiers over the baseline classifiers. MAE, RMSE, and R-squared values were predicted for all the four stacked model approaches. The stacking model was considered a better model if it produced fewer errors (MAE and RMSE) and if the R-squared value was nearer to 1.

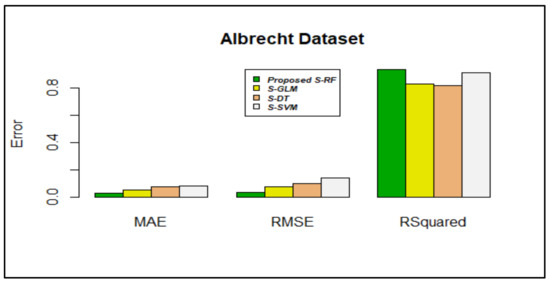

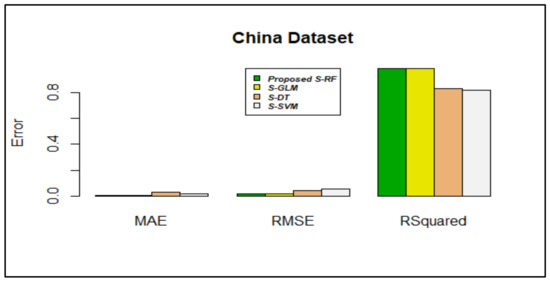

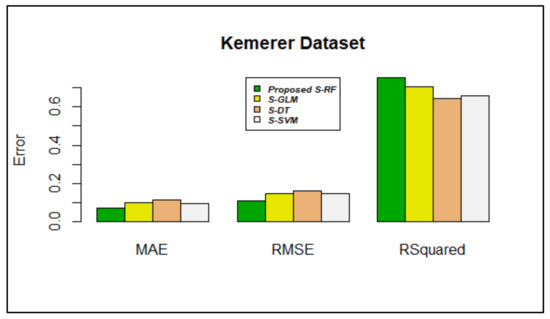

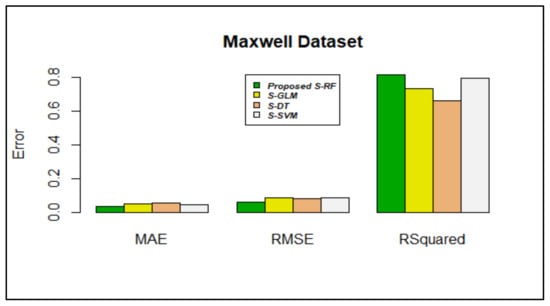

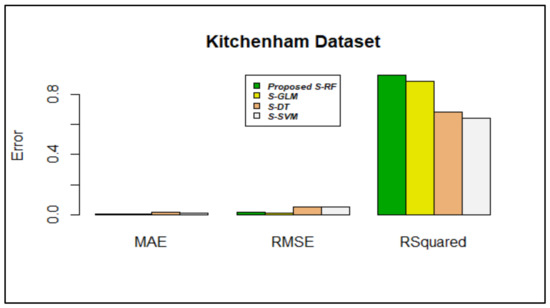

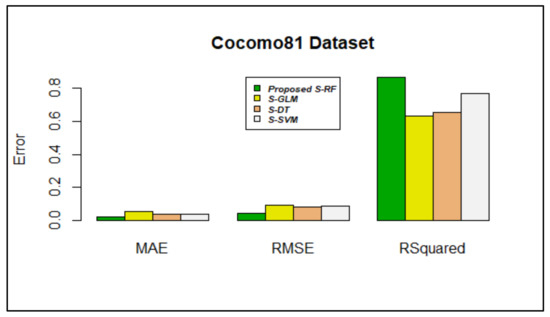

Based on the inference from Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9, stacking using random forest produced less errors (MAE & RMSE) compared with other stacking models; the R-squared values were also closer to 1.

Figure 3.

Error rate vs. stacking models in the Albrecht dataset.

Figure 4.

Error rate vs. stacking models in the China dataset.

Figure 5.

Error rate vs. stacking models in the Desharnais dataset.

Figure 6.

Error rate vs. stacking models in the Kemerer dataset.

Figure 7.

Error rate vs. stacking models in the Maxwell dataset.

Figure 8.

Error rate vs. stacking models in the Kitchenham dataset.

Figure 9.

Error rate vs. Stacking models in Cocomo81 dataset.

Figure 3 shows that stacking using RF produces less value in terms of MAE and RMSE, which were 0.0288617 and 0.0370489, respectively. The value of R-squared is preferred to be nearer to 1; compared with other stacking algorithms, the R-squared value was nearer to 1(0.9357274) in the proposed stacking using the RF algorithm.

Figure 4 shows that stacking using RF produced less error, MAE (0.004016189), and RMSE (0.01562433) compared with other algorithms. For a better predictive model, the R-squared value should be closer to 1; in stacking using RF, the R-squared value (0.9839643) was closer to 1.

In the Desharnais dataset, MAE and RMSE values of stacking using RF produced less error values, 0.07027704 and 0.1072363, respectively; the R-squared value is 0.6556170. As shown in Figure 5, compared with other stacking algorithms, the proposed algorithm provided better results.

Figure 6 shows that stacking using random forest produced lower MAE (0.07030604) and RMSE (0.1094053) values. The r-squared value (0.7520435) was also closer to 1.

Figure 7 shows that stacking using RF produced lower MAE (0.03566583) and RMSE (0.06379541) values compared with other algorithms. The R-squared value (0.8120214) was also closer to 1.

In the Kitchenham dataset, MAE and RMSE values of stacking using RF produced less error values, 0.005384577 and 0.01505940, respectively; the R-squared value was 0.9246614. Figure 8 shows that, compared with other algorithms, the proposed algorithm provided better results.

Figure 9 shows that stacking using RF produced lower MAE and RMSE values, as 0.02278088 and 0.04415005, respectively. The value of R-squared was preferred to be nearer to 1; compared with other algorithms, the R-squared value is nearer to 1 (0.8667750) in proposed stacking using the RF algorithm.

5.2. Proposed Stacking Using Random Forest against Single Base Learners and Ensemble Techniques for Estimation

Single base learners considered for estimation were random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), decision tree (DT), neural net (NN), ridge regression (Ridge), LASSO regression (LASSO), elastic net regression (EN), and deep net (DN) and ensemble techniques including averaging (AVG), weighted averaging (WAVG), bagging (BA), boosting (BS), and stacking using RF (SRF). The software used for estimation was RStudio. Evaluation measures considered were mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and R-squared.

Ensemble approaches considered for comparison were averaging, weighted averaging, bagging, boosting, and stacking using RF. Single models considered for comparison were random forest, SVM, decision tree, neural net, ridge regression, LASSO regression, elastic net, and deep net algorithms.

Table 4 shows the mean absolute error values for the base learners and ensemble approaches against seven datasets. Out of all compared 12 algorithms, the proposed stacking using random forest produced minimal error values (mean absolute error) for all seven datasets. Based on the inference from Table 4, mean absolute error value of the proposed stacking using random forest was lower when compared with all other considered algorithms against seven datasets. The values of the proposed stacking using RF model were 0.0288617, 0.004016189, 0.07027704, 0.07030604, 0.03566583, 0.005384577, and 0.02278088 for the datasets Albrect, China, Desharnais, Kemerer, Maxwell, Kitchenham, and Cocomo81, respectively. The values suggest that the proposed stacking using the RF model produced lower MAE only when compared with other base learner algorithms such as random forest, SVM, decision tree, neural net, ridge regression, LASSO regression, elastic net, and deep net and other ensemble approaches including averaging, weighted averaging, bagging, and boosting.

Table 4.

Base learners and ensemble techniques vs. MAE of 7 datasets.

Table 5 shows the root mean square error values for the base learners and ensemble approaches against seven datasets. Table 5 shows that, out of all compared 12 algorithms, the proposed stacking using random forest produced minimal error values (root mean square error) for all seven datasets. The values of the proposed stacking using the RF model were 0.0370489, 0.01562433, 0.1072363, 0.1094053, 0.06379541, 0.01505940, and 0.04415005 for the datasets Albrecht, China, Desharnais, Kemerer, Maxwell, Kitchenham, and Cocomo81, respectively. When compared with the proposed stacking using the RF model with other base learner algorithms such as random forest, SVM, decision tree, neural net, ridge regression, LASSO regression, elastic net, and deep net and other ensemble approaches including averaging, weighted averaging, bagging, and boosting, the proposed model produced lower RMSE values.

Table 5.

Base learners and ensemble techniques vs. RMSE of 7 datasets.

Table 6 shows the R-squared values for the base learners and ensemble approaches against seven datasets. The data suggest that, out of all 12 compared algorithms, the proposed stacking using random forest produced values nearer to 1 (R-squared) for all seven datasets. The values of the proposed stacking using the RF model were 0.9357274, 0.9839643, 0.6556170, 0.7520435, 0.8120214, 0.9246614, and 0.8667750 for the datasets Albrecht, China, Desharnais, Kemerer, Maxwell, Kitchenham, and Cocomo81, respectively. The values clearly suggest that the proposed stacking using the RF model produced R-squared values nearer to 1 when compared with other base learner algorithms like Random Forest, SVM, decision tree, neural net, ridge regression, LASSO regression, elastic net, and Deepnet and other ensemble approaches including averaging, weighted averaging, bagging, and boosting. The algorithm that provided R-squared values nearer to 1 indicates a good correlation between the data and the model. Thus, ensemble approaches are preferred over single models for two reasons: better performance in terms of prediction, and robustness, which reduces the spread of predictions.

Table 6.

Base learners and ensemble techniques vs. R-squared of seven datasets.

Initially, stacking models considered for evaluation were stacking using the generalized linear model (S-GLM), stacking using decision tree (S-DT), stacking using support vector machine (S-SVM), and stacking using random forest (S-RF). Stacking using random forest was found to be the best model for prediction when compared with seven datasets against evaluation measures MAE, RMSE, and R-squared metrics. The proposed stacking using random forest compared with the single base learners such as random forest (RF), support vector machine (SVM), decision tree (DT), neural net (NN), ridge regression (Ridge), LASSO regression (LASSO), elastic net regression (EN), and deep net (DN) and with ensemble techniques including averaging (AVG), weighted averaging (WAVG), bagging (BA), and boosting (BS). Based on the data from Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6, it was found that the proposed stacking using RF provided better results in terms of the evaluation measures MAE, RMSE, and R-squared when compared with the single model approaches and ensemble approaches that included averaging, weighted averaging, bagging and boosting.

6. Conclusions

This paper presented software effort estimation using ensemble techniques and machine and deep-learning algorithms. Ensemble techniques compared were averaging, weighted averaging, bagging, boosting, and stacking. Various stacking models considered for evaluation were stacking using generalized linear model, stacking using decision tree, stacking using support vector machine, and stacking using random forest. The proposed stacking using random forest provided the best results and was compared with the single models, namely random forest, SVM, decision tree, ridge regression, LASSO regression, elastic net regression, neural net and deep net using Albrecht, China, Desharnais, Kemerer, Maxwell, Kitchenham, and Cocomo81 datasets. The results suggest that the proposed stacking using RF provides better results compared with single models. This estimation is used as input for the pricing process, project planning, iteration planning, budget, and investment analysis. Evaluation metrics considered were mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and R-squared. In the future, a hybrid model will be developed for better prediction of software effort estimation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.V.A.G. and A.K.K.; methodology, P.V.A.G.; software, P.V.A.G.; validation, P.V.A.G. and A.K.K.; formal analysis, A.K.K.; investigation, A.K.K.; resources, P.V.A.G.; data curation, P.V.A.G.; writing—original draft preparation, P.V.A.G.; writing—review and editing, P.V.A.G., A.K.K. and V.V.; visualization, P.V.A.G.; supervision, A.K.K. and V.V.; project administration, V.V.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available in a publicly accessible repository that does not issue DOIs. Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data can be found here: [http://promise.site.uottawa.ca/SERepository].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Sehra, S.K.; Brar, Y.S.; Kaur, N.; Sehra, S.S. Research patterns and trends in software Effort Estimation. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2017, 91, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Kushwaha, D.S. Estimation of Software Development Effort from Requirements Based Complexity. Procedia Technol. 2012, 4, 716–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silhavy, R.; Silhavy, P.; Prokopova, Z. Using Actors and Use Cases for Software Size Estimation. Electronics 2021, 10, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denard, S.; Ertas, A.; Mengel, S.; Ekwaro-Osire, S. Development Cycle Modeling: Resource Estimation. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, B.K.; Kim, R. Effort Estimation Approach through Extracting Use Cases via Informal Requirement Specifications. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priya Varshini, A.G.; Anitha Kumari, K. Predictive analytics approaches for software Effort Estimation: A review. Indian J. Sci. Technol. 2020, 13, 2094–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorgensen, M. Practical Guidelines for Expert-Judgment-Based Software Effort Estimation. IEEE Softw. 2005, 22, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satapathy, S.M.; Rath, S.K.; Acharya, B.P. Early stage software Effort Estimation using random forest technique based on use case points. IET Softw. 2016, 10, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandhi, V.; Chezian, R.M. Regression Techniques in Software Effort Estimation Using COCOMO Dataset. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Intelligent Computing Applications, Coimbatore, India, 6–7 March 2014; pp. 353–357. [Google Scholar]

- García-Floriano, A.; López-Martín, C.; Yáñez-Márquez, C.; Abran, A. Support vector regression for predicting software enhancement effort. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2018, 97, 99–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassif, A.B.; Ho, D.; Capretz, L.F. Towards an early software estimation using log-linear regression and a multilayer perceptron model. J. Syst. Softw. 2013, 86, 144–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskeles, B.; Turhan, B.; Bener, A. Software Effort Estimation using machine learning methods. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Symposium on Computer and Information Sciences, Ankara, Turkey, 7–9 November 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nassif, A.B.; Azzeh, M.; Idri, A.; Abran, A. Software Development Effort Estimation Using Regression Fuzzy Models. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2019, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idri, A.; Hosni, M.; Abran, A. Improved Estimation of Software Development Effort Using Classical and Fuzzy Analogy Ensembles. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 2016, 49, 990–1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidmi, O.; Sakar, B.E. Software Development Effort Estimation Using Ensemble Machine Learning. Int. J. Comput. Commun. Instrum. Eng. 2017, 4, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Minku, L.L.; Yao, X. Ensembles and locality: Insight on improving software Effort Estimation. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2013, 55, 1512–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varshini, A.G.P.; Kumari, K.A.; Janani, D.; Soundariya, S. Comparative analysis of Machine learning and Deep learning algorithms for Software Effort Estimation. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1767, 12019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idri, A.; Amazal, F.a.; Abran, A. Analogy-based software development Effort Estimation: A systematic mapping and review. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2015, 58, 206–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.S.; Behera, H.S.; Kumari, A.; Nayak, J.; Naik, B. Advancement from neural networks to deep learning in software Effort Estimation: Perspective of two decades. Comput. Sci. Rev. 2020, 38, 100288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedotova, O.; Teixeira, L.; Alvelos, H. Software Effort Estimation with Multiple Linear Regression: Review and Practical Application. J. Inf. Sci. Eng. 2013, 29, 925–945. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelali, Z.; Mustapha, H.; Abdelwahed, N. Investigating the use of random forest in software Effort Estimation. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2019, 148, 343–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassif, A.B.; Azzeh, M.; Capretz, L.F.; Ho, D. A comparison between decision trees and decision tree forest models for software development Effort Estimation. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Communications and Information Technology, Beirut, Lebanon, 19–21 June 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Corazza, A.; Di Martino, S.; Ferrucci, F.; Gravino, C.; Mendes, E. Using Support Vector Regression for Web Development Effort Estimation. In International Workshop on Software Measurement; Abran, A., Braungarten, R., Dumke, R.R., Cuadrado-Gallego, J.J., Brunekreef, J., Eds.; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; Volume 5891, pp. 255–271. [Google Scholar]

- Marapelli, B. Software Development Effort Duration and Cost Estimation using Linear Regression and K-Nearest Neighbors Machine Learning Algorithms. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 9, 2278–3075. [Google Scholar]

- Hudaib, A.; Zaghoul, F.A.L.; Widian, J.A.L. Investigation of Software Defects Prediction Based on Classifiers (NB, SVM, KNN and Decision Tree). J. Am. Sci. 2013, 9, 381–386. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.H.C.; Keung, J.W. Utilizing cluster quality in hierarchical clustering for analogy-based software Effort Estimation. In Proceedings of the 8th IEEE International Conference on Software Engineering and Service Science, Beijing, China, 20–22 November 2017; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Sree, P.R.; Ramesh, S.N.S.V.S.C. Improving Efficiency of Fuzzy Models for Effort Estimation by Cascading & Clustering Techniques. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 85, 278–285. [Google Scholar]

- Rijwani, P.; Jain, S. Enhanced Software Effort Estimation Using Multi Layered Feed Forward Artificial Neural Network Technique. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2016, 89, 307–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassif, A.B.; Azzeh, M.; Capretz, L.F.; Ho, D. Neural network models for software development Effort Estimation: A comparative study. Neural Comput. Appl. 2015, 2369–2381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pospieszny, P.; Czarnacka-Chrobot, B.; Kobylinski, A. An effective approach for software project effort and duration estimation with machine learning algorithms. J. Syst. Softw. 2018, 137, 184–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, S.; Keung, J.; Bosu, M.F.; Bennin, K.E. Duplex output software Effort Estimation model with self-guided interpretation. Inf. Softw. Technol. 2018, 94, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singala, P.; Kumari, A.C.; Sharma, P. Estimation of Software Development Effort: A Differential Evolution Approach. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Intelligence and Data Science, Gurgaon, India, 6–7 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).